Malpractice Incidents

Screw Posts

Screw posts represent a restorative anachronism. The risk of root fracture is too great compared with the benefit, particularly when reasonable and superior passive alternatives exist (see Chapter 22). Even if the screw post is initially placed passively, the temptation to turn the screw is too great, considering human nature. Therefore screw posts are not a reasonable and prudent treatment choice.

Paresthesia Prevention

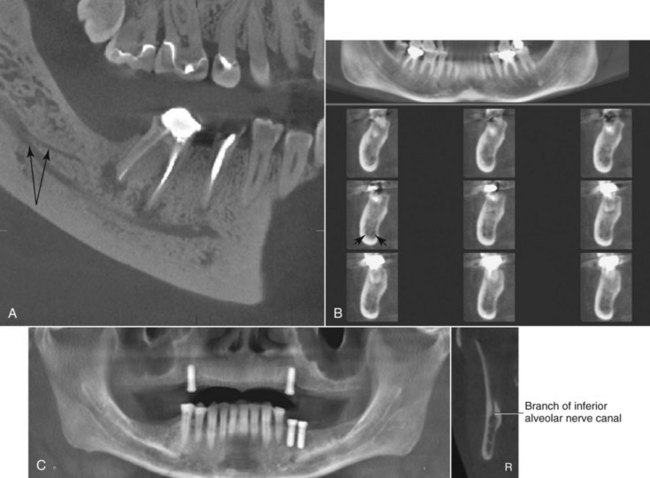

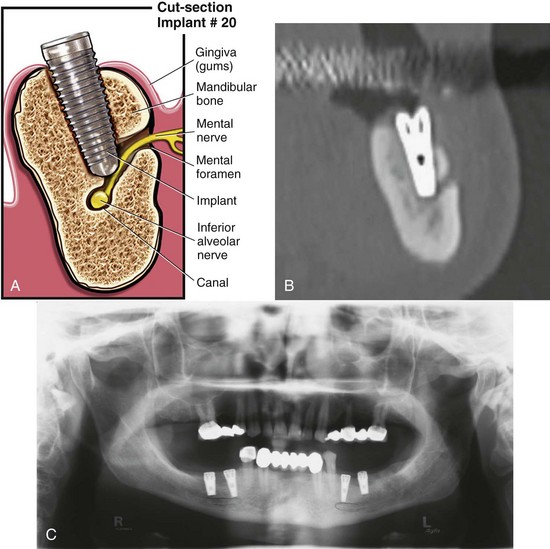

Endodontic surgery in the vicinity of the mandibular canal or mental foramen carries with it the significant risk of irreversible injury to the inferior alveolar and/or mental nerve. Consequently, the clinician must advise the patient in lay terms of the risk of temporary or permanent anesthesia or paresthesia before any surgery near these structures is performed. To document that adequate informed consent was provided, the clinician should have the patient execute a written informed consent form confirming that the patient was so advised. Informed consent is no defense if the surgery was negligently chosen or performed, because informed consent only applies to non-negligent treatment risks. CBCT imaging has greatly reduced if not eliminated entirely the likelihood of IANC perforation. CBCT provides diagnostic guidance before therapy. Also, a final diagnosis confirms or rules out IANC penetration post treatment, promoting prompt removal of foreign materials piercing the IANC.

A clinician initiating root canal therapy on a mandibular posterior tooth must have (1) an awareness of the vital neurovascular bundle containing the IAN, which commonly approximates the ends of these roots, and (2) a diagnostic-quality image that accurately demonstrates the IANC. If endodontics is done without adequate diagnostic radiographs, the patient is placed at great risk if there is anatomic variation or vital neural bundles lie in close proximity to these roots.85,146,168,234,271 Overfilling and/or overinstrumentation of the root ends can cause traumatic and/or chemical injury to the IAN bundle, resulting in potentially permanent altered or total loss of sensation from paresthesia (partial numbness), anesthesia (total anesthesia), and/or dysesthesia (burning pain).

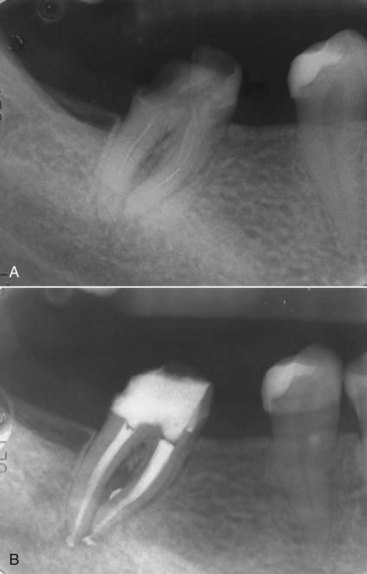

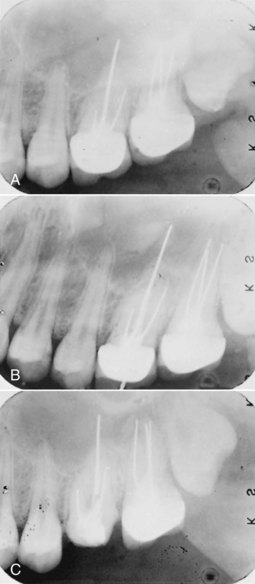

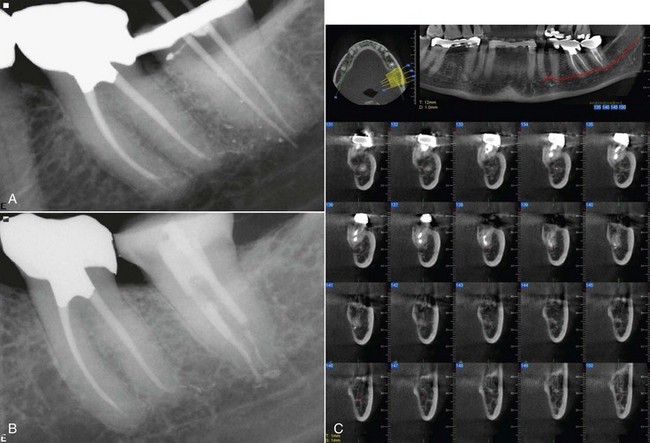

The risk of overfills containing toxic materials causing irreversible neuropathies results from (1) inadequate imaging of the proximity of both borders of the IANC (Fig. 11-23, A-C), (2) inadequate measurements during cone measurement, and (3) not limiting filling materials to within the confines of the shaped root canal space as further evident in CBCT.

FIG. 11-23 A, Unclear periapical to show both cortical borders of inferior alveolar nerve canal (IANC). B, Cones placed into IANC, showing measurements beyond apices. C, Overfill into IANC better shown on cone-beam computed tomography (CBCT) than periapicals of A and B.

The eugenol component of the root canal sealer part of the overfill is known to be cytotoxic. Consequently, endodontic overfill of the root apex is capable of producing not only mechanical damage180 but also chemical injury. Accordingly, a prompt microsurgery referral to remove the injurious materials from the IAN inside the IANC nerve space before overfill material toxins are chemically set is mandatory.206 Better yet is to take precautions to prevent ANY significant injurious overfill.

The use of electronic measuring devices such as an electronic apex locator is standard technology for accuracy when working deep within the root canal system. In addition to radiographs, an apex locator helps provide accurate length readings. If it is determined that the apex is in extremely close proximity to the IANC, extra precaution must be taken to prevent overextension of instruments or materials.

Precise measurements during cleaning, shaping, and obturation compacting stages of endodontics minimizes significant overfill incidents. Obturating filling materials are not only toxic to nerve cells but also create a mechanical pressure injury to the nerve cells themselves. Immediate microsurgical referral for retrieval of any overfill materials which “harpoon” the IANC protect against irreversible neuropathies (see Fig. 11-25, C).206

Serious mechanical and chemical injury to the IAN results from a lack of recognition of the overfill piercing the IANC and/or disregard for neuropathic symptoms the patient reports postoperatively that are consistent with neurologic deficits.

Referral to an oral surgeon/microsurgeon is time dependent. Pogrel’s study demonstrated complete reversal of neuropathic symptoms secondary to overfill if microsurgery was done within 48 hours.206 Two-thirds of Pogrel’s patients gained significant improvement if microsurgery was done within 3 months of IAN overfill injuries. Delaying expeditious referral to a microsurgeon for removal of overfilled materials progressively worsens the toxic effects of the chemical injury over time. Delaying microsurgical referral risks permanent injury, owing to the time-dependent nature of overfill errors.

After 3 months, microsurgical delay will almost close the window of opportunity to prevent permanent neurologic deficits of altered sensation, with resulting pain, numbness, and painful burning symptoms extrusion overfills into the IANC can cause. Stat referral for microsurgical removal of paraformaldehyde-containing root canal filling materials and sealants is even more critically time dependent because of the greater toxicity and mummifying effects of these powders when mixed into pastes (e.g., N2 and RC2B). Risks include anaphylactic shock.34,99,115,155

For needed stat referrals, the offending clinician should phone, write to, and e-mail the microsurgeon. Patients lack the expertise to promptly obtain critically time-dependent referrals. When time is of the essence, the clinician and staff must assume direct responsibility to assure the stat referral to a microsurgeon is promptly accomplished.

Treatment Failure

A clinician should not guarantee treatment success. It is foolish to assure the patient of a perfect result.49 Endodontic failures may occasionally occur despite adequate endodontic care.131,249 Nevertheless, negligent contributing factors to endodontic failures include perforation, missed or transported canal, uninstrumented portion of a root canal, bacterial infiltrates by way of a leaky coronal restoration contaminating the root canal filling,48,237,241 overextension errors, and inadequate isolation of the tooth from salivary contaminants during instrumentation due to lack of a rubber dam.

To avoid claims based on failed endodontics, the patient should be advised in advance of treatment of the inherent (but relatively small) risk of failure (i.e., about 5% to 10%). It may be adequate to advise the patient of the high statistical probability of success in endodontics if the clinical condition of the tooth and the clinician’s past success rate warrant such representation.116,236 Clinicians should avoid quoting the national success rate of endodontics when (1) the patient’s tooth is of questionable endodontic and periodontal status and (2) the clinician is known to have an unusually high endodontic failure rate—for example, a rate that varies markedly from national statistics, which also suggests referral to an endodontist.

An endodontic treating clinician is also liable for failure to disclose evident pathosis in the quadrant being treated. The patient should be advised of any periodontal disease that adversely affects the prognosis of abutment teeth for partial dentures, bridges, or an implant with a need for grafting if the endodontically treated tooth is lost. A clinician should also advise of cysts, fractures, or lesions of suspected neoplasms. In addition, the clinician must be careful not to ignore any evident pathosis that if untreated may adversely affect the dental or medical health of the patient. Again, a clinician who fails to plan treatment properly is planning for treatment failure.

The doctrine of informed consent protects both the clinician and the patient so that there will be no surprises or patient disappointment if a non-negligent adverse result occurs. Should such a failure or complication occur, the availability of a signed informed-consent form can serve as a reminder to the patient that the risk of complications, including failure, was discussed in advance of treatment and that unfortunately the patient’s endodontic treatment fell outside the usual 90% or greater root canal therapy success rate.

Slips of the Drill

A slip of the drill, like a slip of the tongue, may be unintentional. Nevertheless, it can cause harm. When a cut tongue or lip occurs, it is usually the result of operator error. To paraphrase Alexander Pope, to err is human, to forgive, divine. To increase the likelihood that a patient will forego filing suit because of a cut lip or tongue, the clinician should follow these steps:

Leakage

Long-term seal of the root canal system is determined apically by the sealer and coronally by the final restoration.24,106,189,237 Root canal–filled teeth should be permanently restored without undue delay to prevent leakage contamination of the previously obturated canal system, since varying canal shapes from round to oval prevent a 100% seal.63,64,164 Bonded seals covering the canal surfaces should be used to control any leakage after compaction until a permanent restoration is cemented. Besides an adequate coronal sealing, an adequate apical sealer should be well adhered to the canal walls.

The endodontic goal is to prevent bacterial contamination of the periradicular tissue by predictably providing adequately cleaned, shaped, and filled root canal systems. Any residual bacteria should be entombed in the root canal filling. A bacteria-tight apical seal should be designed to last long term with sealed portals to prevent reentry of microorganisms, which cause reentry recontamination and lead to endodontic failure.63,241 Younger patients are more susceptible to bacterial penetration inside dentin tubules and thus recurring infections.143

Electrosurgery

Electrosurgery can cause problems if mishandled. Damage to the oral cavity caused by improper use of electrosurgical devices consists primarily of gingival necrosis, osteonecrosis, sloughing adjacent to the surgical field, and pulpal necrosis of affected teeth.

All equipment should be properly maintained and certified to meet the American National Standard (ADA specification no. 44 on electrical safety standards). Current equipment should be checked to see that units meet these standards and that electrical cords and other components are in good repair. Electrical receptacles should meet the requirements of the National Electrical Code for circuit grounding and ground fault protection. During use, the dispersive electrode plate should be well away from metal parts of the dental chair and the patient’s clothing, because skin contact can cause burns. Use of plastic mirrors, saliva ejectors, and evacuator tips is strongly recommended.

Reasonable versus Unreasonable Errors in Judgment

Although a clinician is legally responsible for unreasonable errors in judgment, mistakes occasionally happen despite adherence to the standards of reasonable care. A mistake does not prove malpractice unless the mistake is caused by a malpractice error or omission.112 For example, accessory or fourth canals on molar teeth are frequently difficult to locate and may tax the best clinicians. Failure to locate an accessory or fourth canal does not conclusively constitute an unreasonable error of judgment. Rather, this may represent a reasonable error of judgment in the performance of endodontics. Nevertheless, if the additional canal was readily apparent radiographically, the existence of a fourth canal should have been considered, and treatment should have extended to instrumenting and sealing it.

Incorrect Tooth Treatment

A reasonable, non-negligent mistake in judgment may occur because the clinician has difficulty localizing the source of endodontic pain. Vital pulps may on occasion be sacrificed in an attempt to diagnose the pain source, but it is unreasonable and therefore inexcusable to treat the wrong tooth if it is inadequately tested with pulp tests, misidentified on the referral slip, or if radiographs are mounted or read incorrectly. Also, treating large numbers of teeth endodontically (e.g., an entire quadrant) when attempting to localize chronic pain suggests pain is probably not of pulpal origin, and other differential diagnoses should be ruled out.

If the wrong tooth is treated because of an unreasonable mistake in judgment, the clinician should be compassionate, waive payment for all endodontic treatment, and offer to pay the fee for crowning the unnecessarily treated tooth.

Post Retrieval

Ultrasonic instruments will vibrate loose the cement around posts. The clinician can avoid overheating the post by proceeding slowly with a water coolant, periodically resting for cool down, and checking the post temperature periodically to be reasonably certain overheating is not occurring.72,102,191 Fig. 11-16 demonstrates what happened when an endodontist negligently overheated the post during attempted removal, causing tissue necrosis, bone loss, need for augmentation procedures, irreversible pulpitis in an adjacent tooth, and the loss of two teeth.204

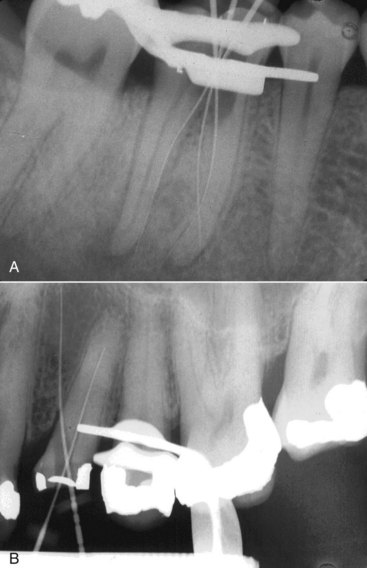

Broken Files

Leaving broken files behind without referring the patient to an endodontist for attempted microscopic retrieval and also not advising the patient of leakage potential may constitute fraudulent concealment (Figs. 11-24 and 11-25). Patients should be informed of such mishaps for (1) referral consultation and/or treatment; (2) advising the patient, who on their own may seek a second opinion; or (3) disclosure, so as to return if a flare-up occurs.

Swallowing or Aspirating an Endodontic Instrument

Use of a rubber dam in endodontics is mandatory.238 Even if the endodontically treated tooth is broken down and cannot be clamped, a rubber dam, regardless of required modification, should be used in all instances (see Chapter 5). Not only is microbial contamination reduced with the use of a rubber dam, the risk of a patient’s aspirating or swallowing an endodontic instrument is eliminated (Fig. 11-26). Accordingly, if a patient swallows or aspirates a file, it is likely because of the clinician’s failure to observe the standard of care. If a swallowing or inhalation incident does occur, the clinician should do the following:

Overextensions and Overfills

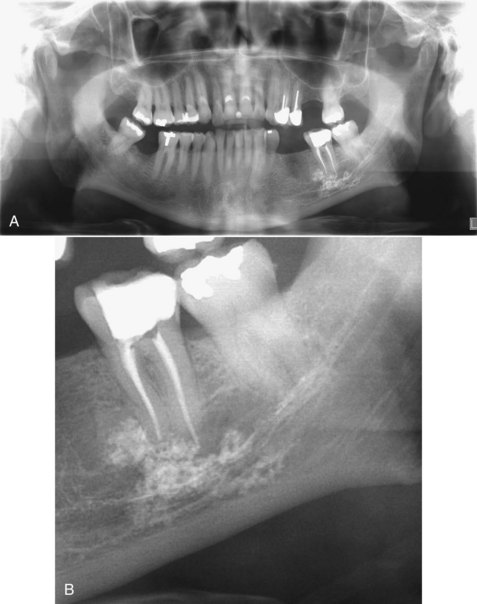

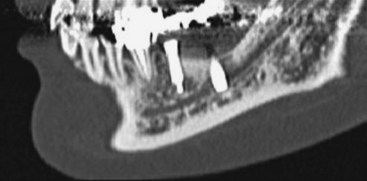

A common error in utilizing periapical or panorex imaging is presuming that when only one cortical border of the IANC is visible, the sole visible border is the superior border. Instead, virtually always when only one cortical border is clearly visible, it is the inferior cortical border.168 (See Fig. 11-25, B periapical, which may appear to show only one cortical border, and Fig. 11-25, C, a clearer CBCT image of the same area showing both cortical borders.)

Misassumption of the IANC borders results in mismeasurement of the IANC location. Since the IANC is approximately 3 mm in diameter, misassuming the sole observable cortical canal border to be the superior border (rather than the inferior border) can result in an imprudent treatment decision to delay microsurgery if overfill occurs and the CBCT confirms an overfill inside the IANC. In Fig. 11-25, B, the defendant endodontist misdiagnosed the overfill as being superior rather than inside the IAN canal, with resultant permanent paresthesia from only watching and waiting for sensory return rather than referring for a stat microsurgical removal.

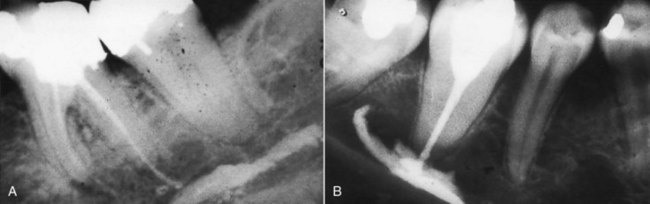

A very slight overextension of root canal filling with conventional obturation or sealants can occur without violating the standard of care (see Chapter 10). Gross overfill usually indicates faulty technique. Fig. 11-27, A-B illustrates gross overfill of calcium hydroxide, causing permanent paresthesia. Nevertheless, so long as the overextension is not in contact with vital structures such as the IAN or sinuses, permanent harm is unlikely unless the root canal is filled with a paraformaldehyde-containing sealant (causing a neurotoxic chemical burn type of injury which chemically diffuses through bone marrow and soft tissue spaces).

If, however, severe postoperative pain is foreseeable as a result of overextension, the patient should be advised of the likelihood of postoperative discomfort because of contact of the sealant material with surrounding tissue. Similarly, if the overextension is very slight and increased postoperative pain is unlikely, the patient need not be advised, lest it cause unnecessary alarm. A note should be made on the patient’s chart of the overextension and the reason for not informing the patient, in case symptoms later manifest. The clinician should observe with close follow-up visits and patient phone calls that evening and the next morning to rule out severe postoperative persistent numbness and/or pain resulting from moderate to large overfills. Fortunately, slight to moderate overextensions with inert conventional endodontic sealers, such as gutta-percha with Grossman’s sealant, often repair themselves and produce no irreversible changes without direct contact into the sinus or IANC.

Overextending the root canal filling material risks permanent consequences if the underlying IAN is initially “harpooned” with files. Portal of entry into the IANC results from overinstrumentation penetration. Flexible gutta-percha alone probably will not penetrate beyond the mature root into the IANC or other vital structures without prior excessive instrument perforation into the IANC.

Mental foramen distances can be overestimated on the panoramic radiograph. Panoramic radiography showed more deviation (+0.6 mm) from the perioperative measurement.85,234 As noted earlier, paraformaldehyde-containing sealants can create cytotoxic chemical destruction of the IAN if placed in close proximity to, even though not directly contacting, the underlying IAN (see reference, Sargenti Opposition Society [SOS]).224 On the other hand, conventional obturators and sealants usually require direct contact with the IAN before resulting permanent anesthesia, paresthesia, and/or dysesthesia occurs (Fig. 11-28). Consequently, the incidence of permanent sequelae with conventional filling materials is extremely low compared with the greater cytotoxic potential with paraformaldehyde-containing sealants.195 Because of the higher risks associated with paraformaldehyde-containing endodontic materials, use of N2, RC2B, or similar toxic pastes is contraindicated and violates the standard of care. Permanent injury risk is substantially less likely with traditional eugenol-containing filling materials, a less toxic chemical than paraformaldehyde, which destroys and mummifies nerve tissues. When safer, less risky alternative effective therapy exists, it is unreasonable (and substandard) to elect an unsafe alternative methodology. Also, the doctrine of informed consent is highly relevant because it is contrary to public policy to request a patient to assume inherently dangerous treatment risks that are reasonably avoidable with safer and more predictable methodologies. When the risk exceeds the benefits, such risks are regarded as negligent and thus should be avoided and not undertaken.

Any significant overextension should be considered for immediate retreatment by attempted retrieval of the overextended gutta-percha. The clinician also has the option of immediately referring the patient to an endodontist for retrieval before the sealant sets. Conventional filling agents such as gutta-percha do not penetrate the cortical walls of the IANC unless preceded by prior penetration with overinstrumentation. This principle can apply to sinus perforation. If despite local anesthesia, the patient feels an electric shock during mandibular molar or premolar instrumentation, this may be a warning sign that the IAN was pierced with endodontic files. If this occurs, the root canal should not be filled; instead, periapical radiographs at different angles should be exposed with instruments in place to confirm whether any IAN penetration resulted. Removal of gutta-percha and sealants that have entered the IANC should be attempted as soon as possible (preferably no later than within the first 24 to 72 hours).206 The eugenol component of the sealant causes an inflammatory reaction in a constricted space which is best relieved by retrieval. If retrieval fails, a decortication microsurgical procedure with an oral surgeon is indicated at the earliest possible time (preferably within the first 24 to 72 hours) owing not only to eugenol chemical toxicity but also eugenol reaction with gutta-percha, which causes expansion and thus a mechanical compression ischemic injury.180,206

Inflammatory edema that compresses and compromises blood supply to soft tissues and nerves in limited spaces with resulting ischemia is termed compartment syndrome.230,274 Compartment syndromes are a group of conditions that result from increased pressure within a limited anatomic space, acutely compromising the circulation and ultimately threatening the function of the tissue within that space. Compartment syndrome occurs from an elevation of the interstitial pressure in a closed osseofascial compartment that results in microvascular compromise. The pathophysiology of compartment syndrome is an insult to normal local tissue homeostasis that results in increased tissue pressure, decreased capillary blood flow, and local tissue necrosis caused by oxygen deprivation. Compartment syndrome is caused by localized hemorrhage or postischemic swelling. The pathophysiology of compartment syndrome is a consequence of closure of small vessels. Increased compartment pressure increases the pressure on the walls of arterioles within the compartment. Increased local pressure also occludes small veins, resulting in venous hypertension within the compartment. The arteriovenous gradient in the region of the pressurized tissue becomes insufficient for tissue perfusion.

The clinician should have a high index of suspicion whenever a closed bony nerve compartment has the potential for bleeding or swelling. Compartment syndromes are characterized by pain beyond what should be experienced from the initial injury. Also, diminished sensation may be noted in the distribution of the nerve within a compartment that is being compressed, such as the IANC enclosed by bone on all sides.

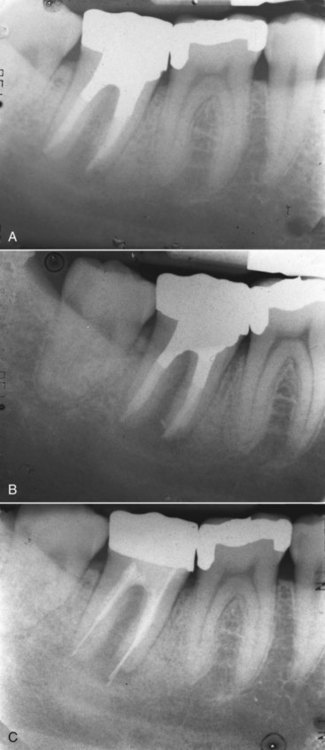

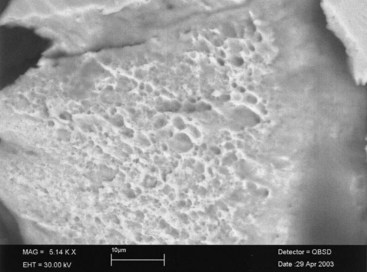

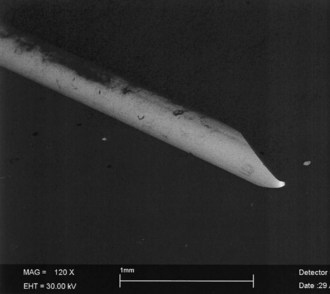

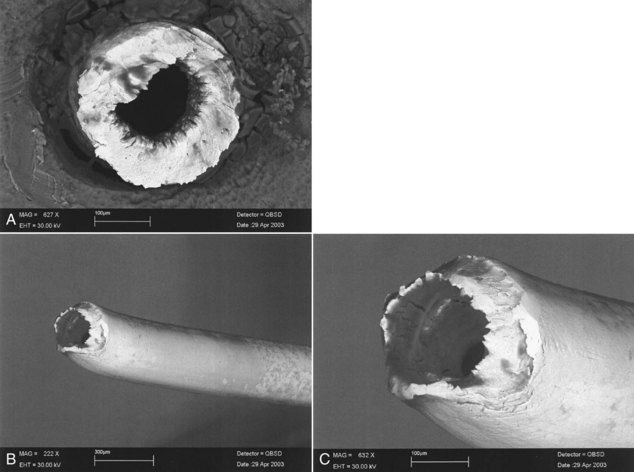

Current Use of Silver Points

Based on what has been known for more than 3 decades, use of silver points in lieu of gutta-percha or other conventional endodontic filling materials represents a departure from the current standard of care. This is because silver points corrode in time, and a tight 3D apical seal is lost. Fig. 11-29, A-C represents gross overextension with a silver point that ultimately caused the loss of tooth #14 as a result of endodontic failure.

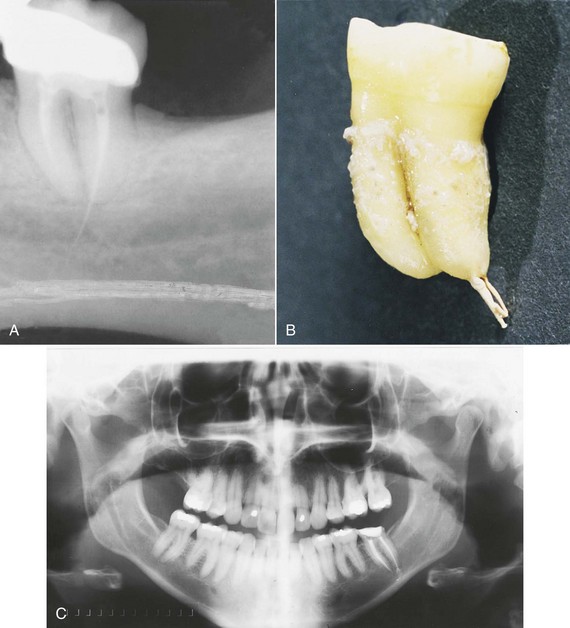

N2 (Sargenti Paste)

Dental literature reports that permanent paresthesias are associated with gross overfilling with paraformaldehyde sealant (N2) that are not usually associated or reported with conventional sealants (Fig. 11-30).162,195 Current use of paraformaldehyde-containing endodontic sealants is not merely the result of a philosophic difference between two respectable schools of thought. Rather, the distinction is between the reasonable and prudent school of thought that advocates conservative conventional endodontics and the imprudent and radical school of paraformaldehyde providers who unreasonably risk permanent, deleterious injury with N2 overextensions. Regardless of the small number of clinicians professing to use N2, it is cytotoxically unsafe and should be avoided. A customary negligent practice by some clinicians is no defense to safe and prudent practice, which the standard of care requires. No matter how few or how many do it wrong never makes it right.

FIG. 11-30 A-B, Overextensions of Sargenti paste filling the inferior alveolar nerve canal. Both cases could have been avoided if the practitioners had selected a conventional sealing material and used a technique that emphasizes length control.

Clinicians may be liable for fraudulent concealment, intentional misrepresentation, or co-conspiracy if they discovered that a previous clinician’s negligence is the cause of dental disease, and both the prior clinician and subsequent treater concealed the prior clinician’s negligence. For instance, if a gross overextension of a paraformaldehyde packing or sealant is evident radiographically, and the patient reports that another clinician caused the overfill (that resulted in permanent lip and chin anesthesia), subsequent treating clinicians may be liable for fraudulent concealment if they misinform the patient that the anesthesia will probably disappear shortly, and that using N2 merely reflects a philosophic difference rather than substandard practice. Reasonable clinicians who differ on therapies regard such differences as controversial. The difference between standard of care and substandard practice is not controversial but rather an indisputable difference between right and wrong. For instance, quackery based upon pseudoscience is not controversial, it is fraudulent practice.25,185 Likewise, if the radiographs indicate sealant is inside the IANC, and the patient complains of persistent anesthesia, the patient should not be told to wait for return of sensation. The clinician should refer the patient immediately for microsurgical consultation regarding decortication and decompression surgery.

The Federal Food, Drug, and Cosmetic Act prohibits interstate shipment of an unapproved drug or individual components used to compound the drug.76 On February 12, 1993, the FDA dental advisory panel confirmed that N2’s safety and effectiveness remain unproven. N2 may not be shipped interstate or distributed intrastate if any of the N2 ingredients were acquired interstate. Mail-order shipments of N2 from out-of-state pharmacies in quantities greater than for single-patient use are considered a bulk sales order rather than a prescription, thus violating FDA regulations.46 A San Francisco jury awarded punitive damages against an N2-distributing New York pharmacy for knowingly shipping N2 in violation of FDA regulations, done with deliberate disregard for patient safety.132

Defective Restorations

Marginal gaps greater than 50 µm lead to cement dissolution and cause 10% of crown failures within 7 years after cementation. Dull or worn explorers substantially increase the likelihood of nondetection of open margins. A sharp explorer can detect margin defects as small as a 35 µm opening.24 Accordingly, a sharp clinician should utilize a sharp explorer to detect open margins. Open crown margins contribute to endodontic failure and should be avoided (see Chapter 22).34