Chapter 5 Evidence-based practice and research

Introduction

The term ‘evidence-based practice’ (EBP) has been used synonymously with ‘evidence-based medicine’ or ‘evidence-based healthcare’ or ‘evidence-based care’ in the National Health Service (NHS) since the early 1990s. While many practitioners may have heard about EBP, it has been defined in many ways and has left practitioners uncertain about its meaning (French 2002). Despite this ambiguity, EBP plays a pivotal role in the NHS Modernisation Agenda (DH 1997) through the National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence (NICE) and National Service Frameworks (NSFs). But what does the practitioner think about EBP? Can all practitioners really claim that their practice is evidence based? On what evidence are clinical decisions based?

These questions will be explored in this chapter through the use of themed activity boxes and issues for reflection that will guide you through the maze of EBP, what it means and how it is used in healthcare practice.

This chapter covers the main components of EBP and encourages you to reflect on your own practice and clinical decision-making. EBP is an idea that is used in all branches of nursing. You will be encouraged to relate the chapter text to your own branch of nursing. You will be directed to locate and appraise evidence relating to a chosen topic area within your practice to develop your understanding of EBP.

What is evidence-based practice?

Evidence-based medicine originated in the fields of medicine and epidemiology. Initial ideas about evidence-based medicine were first thought of by Archie Cochrane in 1972. Cochrane believed that many healthcare interventions were ineffective and that practitioners were heavily influenced by custom and tradition rather than new information gained from research (Stevens et al 2001). It was recognized that this could mean that practices that were ineffective or outdated were still being used despite evidence being available about better ways to treat patients or provide healthcare. Later, in 1991, Sir Michael Peckham suggested that it remained a serious problem (DH 1991). As such, the NHS Modernisation Agenda set out a 10-year plan to standardize and improve the NHS (DH 1997). Central to this plan was an emphasis on evidence-based practice and ‘clinically effective care’ that is now accepted as the cornerstone of modern healthcare.

EBP is now promoted in many Department of Health documents and through the Clinical Governance agenda. The Making a Difference document (DH 1999a) emphasized the need for reliable and robust evidence to underpin nursing, midwifery and health visiting. A similar strategy is promoted within Saving Lives: Our Healthier Nation (DH 1999b), which clearly advocates the need to implement EBP to improve services that promote public health. The importance of EBP is also reflected in many professional regulatory standards. For example, the Nursing and Midwifery Council (NMC) The NMC Code of professional conduct: standards for conduct, performance and ethics Section 6.5, clearly states the need for nurses, midwives and specialist community public health nurses to maintain their professional knowledge and competence to deliver care which is ‘based on current evidence, best practice and, where applicable, validated research when it is available’ (NMC 2004, p. 10). Cox and Reyes-Hughes (2001) consider that EBP has a pivotal role in clinical effectiveness and argue that it is the main driver for clinically effective practitioners. If practitioners are unaware of the effectiveness of an intervention, how then can they claim to be clinically effective?

Defining EBP

Several definitions of EBP exist and, initially, the concept of EBP was applied to medicine in the early 1990s (Box 5.1). Practitioners may find that they prefer one definition as opposed to another, or may find that they do not really have a preference. In each case, the important issue is that practitioners develop an understanding of evidence-based care and are able to question their own practice and the types of evidence used to underpin this.

Box 5.1 Definitions of evidence-based practice

Sackett et al (1996, p. 71) suggest that evidence-based medicine is ‘the conscientious, explicit and judicious use of current best available evidence about the care of individual patients. The practice of evidence based medicine means integrating individual clinical experience with the best available external evidence from systematic research.’

Muir Gray (1997, p. xi) advocates a similar definition when he stated that evidence-based medicine is about ‘making decisions about a group of patients and/or populations and basing such decisions on careful appraisal of the best evidence available’.

On a more practical level, White (1997, p. 175) advises that evidence-based practice is ‘a method of problem-solving which involves identifying the clinical problem, searching the literature, evaluating the research evidence and deciding on the intervention’.

All of the definitions in Box 5.1 identify research evidence as the ‘best’ evidence. Others, however, have broadened this to include types of evidence other than research. For example, the Royal College of Nursing (1996) suggests that audit, client feedback and expertise can all provide evidence. While all of the definitions advocate the use of evidence to support decision-making, there is an assumption that evidence is easily used in everyday practice. However, this process is not always easy. To help practitioners underpin their practice with evidence, a series of steps have been developed. These steps reflect models of evidence-based practice to help practitioners ensure that their practice is evidence based and include:

These steps will be explored in greater depth throughout this chapter.

As EBP has evolved, a variety of descriptive terms have been generated to describe it, based on the context of its use. You may hear the terms ‘evidence-based medicine’ or ‘evidence-based healthcare’ or ‘evidence-based practice’ cited frequently and used interchangeably. While there is some debate about the relationships between these terms, they are all very similar in their meaning which is about improving the quality of practice, reducing risk to clients, aiding decision-making and helping the allocation of resources.

As all these terms may be confusing, this chapter refers to evidence-based care as a term that relates to evidence-based medicine, healthcare and practice.

In conjunction with or in the absence of research evidence, other types of evidence are used to promote effective practice. EBP promotes clinical effectiveness (Cox & Reyes-Hughes 2001) by ensuring that practitioners facilitate care that is safe, effective and based on ‘best’ available evidence.

The EBP cycle

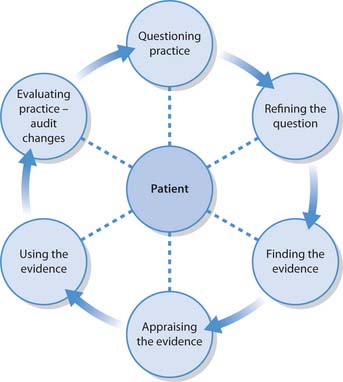

The process of EBP always starts with a question about practice, the answer to which will guide the practitioner and reveal whether their current practice is evidence based (Fig. 5.1). The practitioner may then audit their practice and re-visit the original practice question. This cycle of events ensures that up-to-date practices are carried out and good standards of clinical practice are maintained.

Questioning practice

The first step towards EBP is the ability of practitioners to question their own practice. To do this, practitioners will need to identify why they make decisions in a particular way and acknowledge what or who has informed the decision. Often, practitioners may not take the time to think about why and how they made a decision and, all too often, these are based on ritual and custom rather than a reliable evidence base. All practitioners need to consider what decisions they are making and what evidence is being used to support such decisions. In order to make effective clinical decisions in practice, practitioners need to be able to ask questions about the care or treatment they are providing (Box 5.2).

Box 5.2  EVIDENCE-BASED PRACTICE

EVIDENCE-BASED PRACTICE

Effective decision-making and questioning practice

Effective decision-making

Sister Robbins asks Staff Nurse Dyer to redress a person’s wound using Brand A as a dressing. Staff Nurse Dyer does not question the Sister as to her choice of dressings and follows Sister Robbins instructions and applies Brand A to the person’s wound.

Although Staff Nurse Dyer has provided care to the person by applying Brand A to their wound, they have not made a clinical decision. In this example, Sister Robbins made the decision and Staff Nurse Dyer followed the order.

Questioning practice

Later on that week, Staff Nurse Dyer observes Staff Nurse Flynn applying a different dressing to the same person’s wound. Staff Nurse Dyer begins to wonder which dressing is best for the person and starts to question her own practice.

This later example highlights how questions about practice are identified. Staff Nurse Dyer now questions the type of dressings she applies. By questioning her practice, Staff Nurse Dyer is influencing the care she gives and the clinical decisions she makes as a result.

Now consider the material in Box 5.2. Here we can see that Staff Nurse Dyer now questions the type of dressings she applies. By questioning her practice, Staff Nurse Dyer is influencing the care she gives and clinical decisions she makes as a result. Questioning practice involves thinking about the appropriateness of the care being provided, e.g. Is it the right treatment? How do practitioners know that treatment works? How do different treatments compare? Is the treatment cost effective?

Refining the question into a workable search question

If decisions are based on tradition or ritual then there is a need to think about finding out if there is more reliable evidence to support decisions about practice. To accomplish this, it is useful to formulate a structured question to guide the search for evidence. Formulating workable questions is discussed in the searching for evidence section (pp. 127–128).

Finding the evidence

Once the question has been formulated, the next step is to find the evidence. This will involve using electronic databases such as MEDLINE and CINAHL. Finding evidence can be difficult and there is a need to practise in order to develop the skills needed to search effectively on databases.

Appraising the evidence

When the evidence has been located, practitioners then need to make sense of it. A range of guidelines has been designed to help practitioners make sense of the evidence and decide whether it is robust and believable. Guidelines for appraising evidence are explained later in the chapter.

Implementing the evidence

Following appraisal of the evidence, and once the practitioner is satisfied that the evidence is reliable and trustworthy, they then need to think about how to use this evidence in practice. Implementing evidence-based findings is no easy task, but with support from qualified staff and through reading this chapter, students should be able to make comprehensive plans to help them include the evidence in their practice.

Evaluating or auditing practice

Finally, once practitioners have introduced the evidence into practice, there is a need to reflect on and audit their work and whether it is safe and effective for the patient or client under their care. This may involve other colleagues and professionals who observed their actions.

Practitioners may find that they need to continually audit their practice to ensure that it is based on ‘best’ evidence. For example, practitioners may need to return to the original practice question and refine it, or they may discover that there is a gap in evidence. Whatever the situation, the important message is to be able to continually improve practice by questioning the decisions that practitioners make about a patient’s or client’s care needs.

Literature searching

A crucial way of finding out what is the best practice for a clinical situation is to discover what has been written about it in the literature. This means that practitioners need to be able to carry out a search of the literature and a review of the evidence (NHS Executive 1996).

There are numerous reasons for conducting a literature search. Searching and reviewing the literature identify whether previous studies or audits have been carried out in relation to the topic of interest or whether practice guidelines exist. This might be important if practitioners wish to make changes in practice, as it may be possible to read about how other practitioners improved their practice – both what they did and how they did it. It may also help to highlight potential problems or difficulties that might be encountered during the process of practice innovation (NHS Executive 1996). Determining what the literature identifies provides an opportunity for practitioners to incorporate new knowledge into their decision-making.

A dramatic rise in the amount of scientific literature published has resulted in the need to ensure that practitioners have the skills to find the literature they need (Palmer & Brice 1999). Typically practitioners lack the required skills and find it hard to search the literature efficiently. This has implications for practice as it means that it may not be based on current evidence despite it being available.

This section will provide an introduction to the basic principles and practice of searching for literature and evidence for practice. This will include exploring:

Sources of literature

There are many different sources of information available including books, the Internet, journals and professional organizations. Some will provide examples of original research while others – often referred to as evidence-based sources – will often provide an up-to-date review of the evidence available in a particular area. In both cases it is necessary to undertake an appraisal of the quality of the information presented (see p. 137).

The reason for choosing to use one source over another will depend on the type of information the practitioner wants to find. The following gives a brief overview of some of the key resources that can be used in a search for literature.

Bibliographic/electronic databases

Databases gather together and index large numbers of articles within specific subject areas, e.g. nursing, social sciences. There are many different databases available and they focus on different topic areas. Choosing a particular database(s) to search will depend on the topic area and the databases to which the University or school provides access. Some useful sources are listed in Box 5.3.

AMED – Allied and Alternative Medicine indexes physiotherapy, occupational therapy, rehabilitation, podiatry and complementary medicine articles from 1985 onwards.

BNI – British Nursing Index focusing primarily on British journals. Indexes nursing and midwifery articles from 1985 onwards.

CINAHL – Cumulative Index of Nursing and Allied Health Literature. A nursing and allied health disciplines database, including physiotherapy and health education. It indexes articles from 1983 onwards, and has a strong US focus.

Cochrane Library – A ‘virtual library’ or collection of databases that provide a starting point for accessing systematic reviews. These reviews are primarily concerned with the effectiveness of interventions and therefore concentrate on using randomized controlled trials (RCTs) as their foundation. The Cochrane Library includes:

MEDLINE – A general biomedical database which covers international literature on medicine, allied health, biological and psychological sciences and humanities. It indexes articles from 1966 onwards. Research has suggested that for the majority of nursing queries, MEDLINE is likely to retrieve a higher number of relevant (and often unique) references (Okuma 1994, Brazier & Begley 1996, Brand-de Heer 2001).

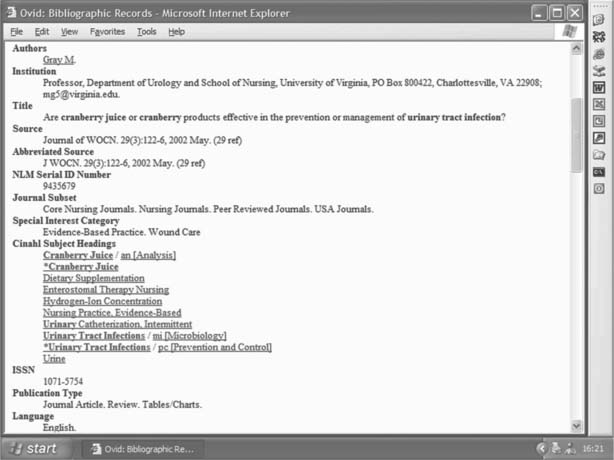

Databases may also distinguish between including examples of primary research projects and literature reviews (reviews of research). By searching a database systematically, practitioners can retrieve a list of references of relevant articles. Normally, the full text of the article is not provided and a trip to the library is needed to look up the article in a journal. Although databases often look different, they can usually be searched in the same way, and use similar formats to provide information, e.g. the author, title, journal source and often an abstract (a clear and concise summary of the study design, results and implications for practice) of the article.

This information enables practitioners to find the full version of the article in the library. If the local library does not stock the required journal, it is usually possible to request the article using the interlibrary loan system. You will probably need to pay a small fee and the library will then request a photocopy of the article from another library.

Books

This group of resources includes textbooks and encyclopaedias. They are useful for obtaining background information and will generally provide a standard account of a specific subject area. They are good for obtaining a distinct piece of information, but can take a long time to get into print. This means that the information they contain is not always/necessarily up-to-date.

The Internet

The Internet provides a way of accessing information and resources in a variety of formats. These can include web pages that provide information, to web pages that provide access to resources such as bibliographic databases. The quality of websites is sometimes difficult to assess, so a good place to start is to use a gateway service. A gateway service is usually subject specific and provides access to quality-assessed websites. An example of a gateway service is the National Library for Health (NLH; www.library.nhs.uk) which provides access to a wide range of health-related services including an index of UK national clinical guidelines. Other examples are included in the list of Useful websites at the end of the chapter.

Journals and newsletters

Published at regular intervals, journals are a useful resource in obtaining the full text versions of primary research projects and articles on practice development, e.g. Nursing Times. More recently, journals have also begun to summarize or make evaluations of original pieces of research. Some adopt quite a formal or structured approach to providing information, e.g. Evidence-Based Nursing or Effective Health Care bulletins (www.york.ac.uk/inst/crd/ehcb.htm), whereas others are more informal, e.g. Bandolier (www.jr2.ox.ac.uk/bandolier).

Some journal sources are more reputable than others because they publish articles that have been peer reviewed. Peer review means that the articles have been sent for evaluation and comment by experts in the area before being accepted for publication, e.g. Journal of Advanced Nursing, Journal of Learning Disabilities. Journals are becoming increasingly available online either via a local library or information service, or via commercial ventures such as PubMed Central (www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov). PubMed Central represents one of a growing number of services which provide free and unrestricted access to a full text digital archive of life sciences journal literature, in this instance, provided by the US National Library for Medicine.

Reports

Like books, reports can be good for obtaining an overview of a subject area. They are often produced by government departments, e.g. Department of Health; professional organizations, e.g. Royal College of Nursing; univers-ities and other statutory and voluntary organizations, e.g. Joseph Rowntree Foundation.

Developing a search question

Before beginning to search for literature, it is important to first think through what information is needed. An important step is developing a search question. A focused search question helps to ensure that the search for literature is structured and time is used efficiently. If the search question is vague, too many references are likely to be retrieved from a database search and the question will not be answered.

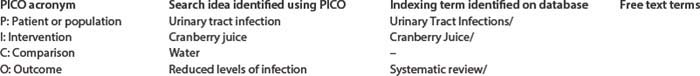

A useful framework to help in structuring a search question is the PICO acronym (Richardson et al 1995) (Box 5.4). The PICO acronym helps the practitioner to identify key elements of the search question, and each letter represents a different element:

Structuring a search question using PICO

Read the information about John and his questions about cranberry juice.

You are on placement with a practice nurse running a ‘well man’ clinic. John is 72 years of age and is waiting to go into hospital for prostate surgery. He has been suffering from recurrent urinary tract infections (UTIs) and has read that cranberry juice is really good at preventing UTIs. He asks about the effectiveness of cranberry juice. The nurse tells John that she is unsure but will make some enquiries and discuss the findings with him.

Student activity

Use the PICO acronym to plan the ideas you would use to search for information to answer John’s question.

Once the key elements of the search question have been identified, the next step is to organize these elements in order of importance. When starting a literature search, it is probable that only two search areas will be needed. However, by having a clear idea of the whole topic area before starting to search, it will be easier to add a third or even a fourth element to the search strategy, and narrow down the type of information being retrieved, without getting sidetracked.

Once there is a clear idea what the search question is, it is then necessary to decide on the most appropriate place to look for the information. Depending on the type of information needed, this might include some or all of the following:

Searching databases

Searching a database can seem daunting but there are a number of steps that, if followed, will make this process easier and more successful. It is sensible to ask the librarian for help in getting started.

The way databases present information can often look quite different, but there are some basic ways of searching which are common to all. The examples used here are from the CINAHL database via the OVID search interface, but a typical database record will include the name of the author, the title of the article, the source of the article, i.e. which journal is it published in, and a list of indexing terms or subject headings (Fig. 5.2).

The reason for the search will determine how comprehensive or complete the coverage of the database search will be. Practitioners who are changing practice once qualified or undertaking a thorough review of the literature for a dissertation will need to find as much information on a topic as possible. However, when searching for a couple of references to support an argument in an assignment, it probably will not matter if you miss a few papers. In both instances, the best place to start is by searching using the databases list of indexing terms.

Indexing terms

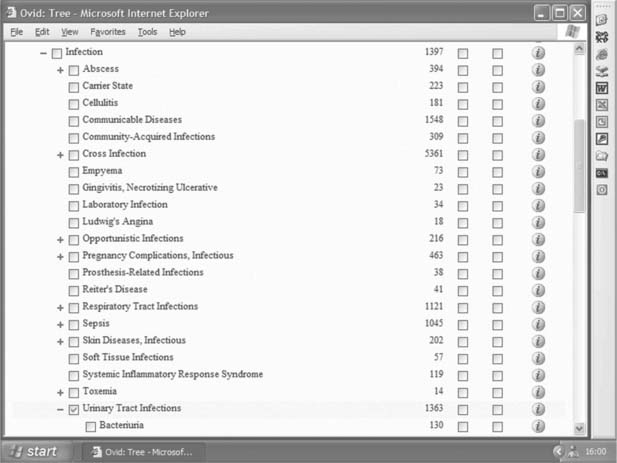

Indexing terms are also called MESH headings, subject headings, thesaurus terms or descriptors, but they all mean basically the same thing. These indexing terms are split into subject areas and are organized within a hierarchy (Fig. 5.3).

Fig. 5.3 Indexing terms are organized in a hierarchy (reproduced by kind permission of OVID Technologies)

The most precise indexing terms – which are assigned by the database producer – are given to describe the content of each article. Using John’s request for information on the effectiveness of cranberry juice in preventing urinary tract infections as an example, every article that mentions urinary tract infections would be given the indexing term ‘Urinary Tract Infection’. It does not matter which specific words have been used to describe the idea/topic because if they were discussing infections of the urinary tract, they will be indexed using ‘Urinary Tract Infection’. However, if the search is for bacteriuria (bacteria in the urine), then the specific indexing term ‘bacteriuria’ is used because the broader indexing term of ‘Urinary Tract Infection’ would not retrieve articles discussing this specific area of interest within the category of urinary tract infections.

It is useful to find out which indexing term is likely to be assigned to the idea/topic being searched for because this can make it easier to search for relevant articles.

While using indexing terms can produce a more accurate search, it may initially take some time to identify the most appropriate indexing terms to use. Most databases will have an option that allows the user to ask for the most likely indexing term in the subject area to be suggested. This feature is sometimes called mapping, when the database makes a ‘best guess’ at suggesting which term(s) will be helpful. If available, it is a good idea to check the description of the indexing term to make sure it means what you think it does (Box 5.5, p. 130).

Identifying indexing terms on a database

Access a database of your choice and identify the indexing terms for the four main elements of the PICO acronym (you might want to have another look at Box 5.4, p. 127).

| PICO acronym | Search idea identified using PICO | Indexing term identified on database |

|---|---|---|

| P: Patient or population | Urinary tract infection | |

| I: Intervention | Cranberry juice | |

| C: Comparison | Water | |

| O: Outcome | Reduced levels of infection |

If you searched on the CINAHL database, you will probably have identified the following indexing terms:

There does not appear to be a suitable indexing term for water, so you may wish to consider using free text searching (see p. 129)

Although a database will often provide an opportunity to search for more than one term at a time, it is usually a good idea to search for each term separately. In this way, if an indexing term is not working as expected, e.g. it is retrieving irrelevant information, it is much quicker to exclude it from the search than having to retype the terms that are to be kept.

It is important to bear in mind that each database will have a slightly different set of indexing terms, so it is necessary to check the list of terms each time a search is started on a new database.

Free text terms

If it is necessary to undertake a more thorough literature search, e.g. for a final year project, this will probably need to use a combination of indexing terms searching with free text searching.

Free text searching is the development of a list of words, or free text search terms, that describe each component of the search question in more detail. For example, this might be a list that includes alternative spellings (including Americanisms), plurals, synonyms and abbreviations (Box 5.6, p. 130).

Developing a list of free text search terms

Add as many synonyms, alternative spellings, Americanisms, plurals or abbreviations to each of the elements of the PICO acronym below (you might want to have another look at Boxes 5.4 and 5.5).

You will probably have identified a range of free text search terms similar to the following:

Note: When free text searching, the database will search for a precise match of the term typed in, so be sure that the spelling is correct.

Free text searching will help ensure the retrieval of the maximum possible literature on a topic area, and will compensate for any mistakes by the database producers in missing or misapplied indexing terms. It is important to remember that as well as increasing the number of potentially relevant articles retrieved, there is also the possibility that it will increase the number of potentially irrelevant references too. In both instances there is a need to allow extra time to read through the retrieved abstracts.

Combining your search terms

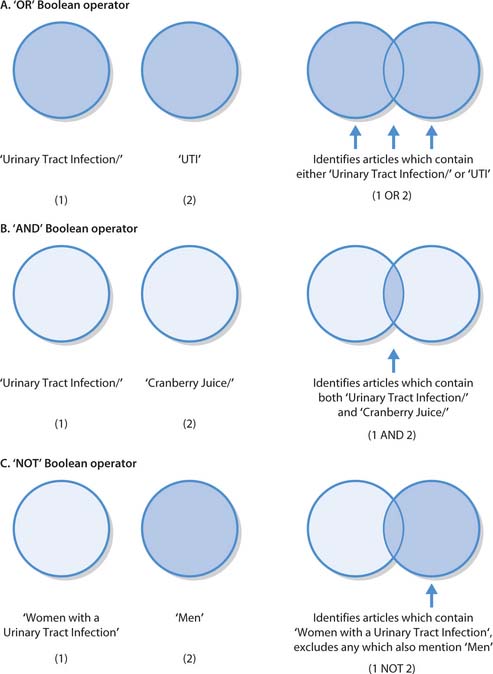

Once the indexing terms for the subject area (and any free text terms for an extended search) have been identified, it is necessary to link the words together using the ‘AND’ and ‘OR’ functions of the database. These are known as the ‘Boolean Operators’.

When searching within a topic/indexing term it is necessary to use the ‘OR’ Boolean operator. ‘OR’ enables the user to search for a range of alternative ways of describing an idea/topic, so that any one of a number of indexing or free text terms may appear. Using the urinary tract infection as an example, the ‘OR’ Boolean operator will enable a search for any combination of indexing or free text search terms, e.g. ‘Urinary Tract Infections/’ or ‘UTI’ (Fig. 5.4A). An easy way to remember how to use the ‘OR’ Boolean operator is the mnemonic ‘OR is more’ (Palmer & Brice 1999).

Fig. 5.4 Boolean operators: A. ‘OR’ Boolean operator. B. ‘AND’ Boolean operator. C. ‘NOT’ Boolean operator

Users may worry if, at this stage, they seem to be retrieving too much information. However, when all indexing terms are combined together using the ‘AND’ Boolean operator, the numbers will quickly decrease.

Once the indexing terms have been combined for each idea/topic, users then need to search for articles where both ideas appear, e.g. where cranberry juice is mentioned in the same article as urinary tract infection. In order to do this, the ‘AND’ Boolean operator is used (Fig. 5.4B).

A third Boolean operator – the ‘NOT’ Boolean operator – enables users to exclude papers that mention a particular topic/word (Fig. 5.4C). While this may initially appear to be a good thing, there is a distinct possibility that users could inadvertently exclude potentially relevant papers. You are advised to use the ‘NOT’ Boolean operator with extreme caution … if at all.

A more effective way of reducing the number of papers retrieved is to add a further element to the search strategy (remember the four elements using PICO, but only starting by searching on the two most important ones) or by adding limits such as date range, publication type, e.g. review/systematic review, or language, e.g. English.

The aim of searching is to start off with a selection of references, sometimes called a ‘sensitive’ search, and then narrow the search down until the number of references is reduced to those that will be useful, sometimes called a ‘precise’ or ‘specific’ search.

Once the search is completed, it is important to make a note of the search strategy. It is good practice to include this in any assignment or report. If it is necessary to return to the search at a later date, it will also mean that there is no need to try to remember which search terms were used.

Sources of knowledge to support evidence-based practice

During the process of providing care, nurses and others must make a wide range of decisions. These decisions have important effects on the person’s and family’s experience of care, and the outcomes of healthcare interventions. Nurses may also be involved in assisting people to make decisions about their own care, such as whether to consent to a particular treatment or not. For nurses to be able to make safe and effective clinical decisions, they must draw on a range of different sources of knowledge. These sources provide a guide for practice and may include:

These different sources of knowledge can be defined as types of ‘evidence’ underpinning practice.

What is meant by ‘evidence’?

Everyone uses evidence from a variety of sources, both in their daily personal lives and in professional practice. However, what constitutes ‘evidence’ has been debated for many years and is rooted in philosophy. Subsequently, as individuals, people will probably perceive evidence as meaning many different things.

Different types of evidence include the information gained from tradition and ritual, experience, intuition, authorities and experts, patients and families, research, audit and guidelines.

Tradition and ritual

Large parts of daily life are based on trusted trad-itions and rituals learnt from others during childhood. Traditions and rituals allow people to undertake activ-ities with little thought or consideration as to the reasons why – they provide structure to everyday life (Walsh & Ford 1989). The process of learning traditions and rituals by observing the actions and activities of peers con-tinues from childhood into adulthood and into the world of employment.

As such, learning traditions and rituals is a central means of transmitting knowledge and is important in nursing as students learn to ‘become’ nurses (Parahoo 1997). This is known as the process of occupational socialization, e.g. learning the ‘ward routine’ (Melia 1984). Students or practitioners learn from effective colleagues who practise safely and on the basis of best evidence. This can be a very useful means of sharing knowledge and good practice. However, relying on traditional knowledge may also lead to the transmission of outdated information and practice, putting both nurses and clients at risk. The moving and handling of patients provides a pertinent example. While many manual handling techniques are considered unsafe, such as the drag lift, outdated and dangerous practices remain widely used (National Back Pain Association 1998) (Box 5.7).

Experience

Practitioners use their own or the experiences of others to inform decisions they make about nursing practice. After experiencing an event, the memory of this is stored and is ready to draw upon in similar circumstance in the future. Practitioners may also discuss experiences with colleagues, thus passing their experiential knowledge on to others. However, while experience brings confidence and the ability to use professional judgement (Rolfe 2002), there is also a risk that experiential knowledge is based on a limited range of events or practice situations to which practitioners have been exposed. As such, practitioners may be unaware of new or different practices or treatments, or recommendations from research (Parahoo 1997).

Intuition

Intuition is defined as a way of knowing and behaving that is not based on rational or conscious reasoning (Parahoo 1997). While many nurses explain the importance of intuition in their nursing care, it is difficult to define exactly what it is. In addition, it is also easy to dismiss another person’s intuition. For example, Polgar and Thomas (1995) describe the activities of the 19th century physician, Ignaz Semmelweis, who noted the high levels of maternal deaths at his hospital and suspected that medical students attending the mortuary were spreading infection via their hands. Unfortunately, while handwashing is now recognized as the cornerstone of effective infection control, at that time Semmelweis and his intuition were ignored and dismissed.

Authorities and experts

Often, practices in healthcare and nursing are determined by the knowledge and opinions of those members of the healthcare team in positions of authority. Knowledge is considered true because the person who states it has authority or is considered an expert. While experts may well possess high levels of knowledge in relation to best practice, at times conflicts may arise when one expert or person in authority holds differing views or opinions from another. It is also possible for experts to hold misplaced views or be biased in some way, as demonstrated in the example of the now discredited ‘expert evidence’ given in criminal proceedings linked with sudden infant death syndrome.

Service users and their families

During the process of providing individualized care, it is important to ascertain the views of people and their families. In this way, it is possible to work in partnership with them to tailor care and treatment to individual needs. This is an important aspect of evidence-based healthcare because it recognizes that people can be, and often are, the experts in their own care. As such, they should be able to make choices and decisions about what happens to them. Although this is a very important source of knowledge upon which to base nursing care, people often feel that they are not involved enough in their own care and are not asked about what services they think should be offered by the NHS. The Department of Health now recognize that service users should have more say in the care that they receive and the types of health service research carried out. In order to ensure that patients’ views are listened to, NHS Trusts have expert patient groups and Patient Advice Liaison Services (PALS). Increasingly, in the field of mental health and learning disabilities, service users are taking the lead in defining what they see as the areas that should be researched and designing and conducting their own research. An example of this is the Strategies for Living Project, by the Mental Health Foundation, which intends to support service user-led research throughout the UK (Box 5.8).

Box 5.8  EVIDENCE-BASED PRACTICE

EVIDENCE-BASED PRACTICE

User involvement and empowerment

Visit either the Patient Advice Liaison Services (PALS) website at www.dh.gov.uk or the Strategies for Living website at www.mentalhealth.org.uk. Read the overview.

Student activities

Research studies

While other sources of knowledge constitute important aspects of the evidence base, knowledge derived from research is crucial to evidence-based practice. This is because, unlike other forms of knowing, research is a systematic approach to generating knowledge using well-established methods (Parahoo 1997, Hamer & Collinson 1999). While there are many different types and ways of carrying out research, the main aim of nursing research is to improve the quality of care and to enable effective clinical decision-making (Parahoo 1997). For example, research can tell practitioners what treatments work best or why they may not be so effective. Research can also help practitioners to find out about how people feel and experience things. For example, research can tell practitioners which drugs are effective in treating high blood pressure and also how people may feel about having a chronic condition or a learning disability.

Audit

Many aspects of nursing care are influenced by the results of audit, which students may come across during their clinical placements, e.g. audits of the use of pressure-relieving mattresses, the incidence of pressure ulcers or the occurrence of aggressive or violent behaviour. The Essence of Care document (DH 2001a) is an important nursing audit tool currently being used in many NHS Trusts (Box 5.9)

Box 5.9  EVIDENCE-BASED PRACTICE

EVIDENCE-BASED PRACTICE

Benchmarking

Locate information about the Essence of Care: Patient Focused Benchmarking for Health Care Practitioners via the Department of Health website (www.dh.gov.uk).

Essentially, clinical audit involves measuring an aspect of practice (such as how often nutritional assessments are carried out, see Ch. 19) and comparing it to agreed standards for best practice. Clinical audit can provide knowledge about nursing care and highlight where improvements are needed. Audit is an important link within the evidence-based practice cycle as, without it, it is not possible to state whether the right practice is actually occurring (Garland & Corfield 1999).

Guidelines

Practitioners may also use guidelines as a source of knowledge from which to base care that they provide. Guidelines are written after the best available evidence, from research and/or clinical expertise (where research evidence is lacking), and client views have been gathered and scrutinized. This evidence is then used to set a standard for best practice in relation to a particular treatment or aspect of care. By setting out recommended standards of practice, guidelines can thus help practitioners to provide the most effective care possible (Thomas & Hotchkiss 2002). For example, a guideline for the assessment and prevention of pressure ulcers has been produced by NICE. In Scotland the Scottish Inter-collegiate Guidelines Network (SIGN) and NHS Quality Improvement Scotland (NHSQIS) produce guidelines (Box 5.10, p. 134). Guidelines can also be used as the standard against which to assess the quality of care during the audit process (Joyce 1999) and may be a way of eliminating variations in clinical practice that exist in different parts of the country.

Box 5.10  EVIDENCE-BASED PRACTICE

EVIDENCE-BASED PRACTICE

Guidelines

Locate a practice guideline associated with the management of obesity in children, or pressure ulcer management, which you have come across during your clinical placements.

Student activity

Knowledge is thus derived from many different sources and, used in combination, can ensure that the care and treatment provided is as effective as possible (Box 5.11, p. 134).

Types of evidence

Read the information about Mrs Kaur and Staff Nurse Smith’s decision about Mrs Kaur’s care.

Mrs Kaur is a 73-year-old lady who has an infected venous leg ulcer and is due to have her dressings changed today by Staff Nurse Smith. After removing the dressing, Staff Nurse Smith observes that the ulcer appears to have worsened. She asks Mrs Kaur what she thinks about the ulcer who agrees that it does look worse. Mrs Kaur also states that she has been in more pain recently. Staff Nurse Smith is concerned that the ulcer has become worse and begins to plan a course of action. After some thought, Staff Nurse Smith remembers that she has used another type of dressing on a venous ulcer in very similar circumstances. She decides to discuss this with her colleague and, with Mrs Kaur’s consent, invites her colleague to review the ulcer. Staff Nurse Smith and her colleague look at the tissue viability guidelines and hospital protocol for the management of venous leg ulcers. After some discussion, Staff Nurse Smith made a decision to contact the tissue viability nurse for an opinion.

Student activity

Identify the different types of evidence used by Staff Nurse Smith.

You probably included the following types of evidence:

Through your reflection, you may have thought of other types of ‘evidence’. For example, you may have attended a lecture, spoken with your personal tutor or attended a conference. What is important is that you develop the skills needed to differentiate between good or ‘best’ evidence and bad evidence.

Best evidence

As already stated, evidence-based care is an essential component of clinical effectiveness. To help make decisions about the most suitable treatments, interventions or services to provide, the best available evidence must be sought out. These sources of evidence must demonstrate the effectiveness of the intervention (Box 5.12). The notion of ‘best’ evidence is controversial and tensions exist between different beliefs about what constitutes ‘best’ evidence. Some argue that experimental research that demonstrates the effectiveness of an intervention is the best evidence; however, others disagree, viewing other types of evidence as more informative for certain clinical situations (Cox & Reyes-Hughes 2001).

Box 5.12  EVIDENCE-BASED PRACTICE

EVIDENCE-BASED PRACTICE

Use of evidence

Student activities

A number of hierarchies now exist, enabling different types of research and evidence to be graded or ranked according to their ability to predict effectiveness, remove bias and control confounders and provide more confidence in the reliability of the findings (see pp. 140–141 for further information). One such hierarchy is described by Thompson and Cullum (1999) where the highest level of evidence is a systematic review of several high-quality randomized controlled trials (RCTs), through various grades to expert opinion, which is the lowest level in the hierarchy.

Experimental research such as RCTs is seen by many as the ‘highest standard’ of evidence because the findings are thought to be more valid and reliable than that of non-experimental descriptive research and other evidence.

In general, research is viewed by many as the most important source of knowledge for practice. It is a large topic area and the next section provides an introduction to some of the key aspects.

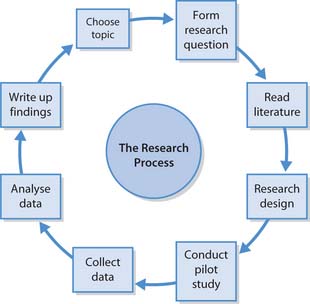

Overview of the research process

In order to carry out research correctly, certain rules and logical steps need to be followed. This is known as the ‘research process’ that is often viewed as cyclical in nature, rather than linear (Fig. 5.5).

When research projects are reported in academic journals and reports, they will often describe the research process followed. For the reader, this is important as it makes it clear how the research was carried out. It should also provide enough detail for readers to decide whether the project followed the proper rules or research process.

There are many different forms of research evidence and although there are exceptions, research can be defined broadly as quantitative or qualitative in nature.

Quantitative research

Quantitative research is described as the logical collection of numerical data under controlled conditions that uses statistics to analyse the data. This type of research is based on the belief that the world, events and phenomena are governed by laws that can be uncovered by measuring and counting and searching for correl-ations between different phenomena (Parahoo 1997). For example, this type of research might try to find out about ‘cause and effect’ – i.e. does A 1 B 5 C? It often (but not always) involves the testing of hypotheses through objective measurements and observations to see whether the hypothesis is supported or rejected.

Qualitative research

Qualitative research can be defined as the logical collection of subjective data that often include narrative or observational materials without additional researcher control. This type of research assumes that the complexity of everyday life cannot be reduced to numbers as much meaning could be lost. It is also accepted that there is never simply one reality – that there will always be different experiences and perspectives. There is no attempt to control the environment in which data are being collected, as the aim is to understand events, as they unfold, from the perspective of those people experiencing them (Craig & Smyth 2002).

Quantitative and qualitative research in nursing

Both approaches to research are needed within nursing, as many research questions require the measurement of objective facts to inform the development of clinical practice. However, much nursing work cannot be broken down into measurable parts without the meaning of that phenomenon being lost. The focus of qualitative research is on the individuality of human experience that fits closely with the purpose of nursing.

Often, a particular research topic or research question will require a combination of quantitative and qualitative research. This allows for a more complete understanding of the particular phenomenon to be gained. For example, back injuries in nurses and moving and handling practices have been explored using both quantitative surveys and qualitative interview and observational studies. Box 5.13 (see p. 136) shows the contrasting approaches and types of information gained by two studies. In other cases, a combination (or ‘mixed method’) approach might also be used within one project. For example, a study exploring the role of the nurse in the rehabilitation setting used a combination of semi-structured interviews with nurses and clients and other members of the multidisciplinary team. This study also observed nursing practice and used client records and a questionnaire survey to ascertain data about the role of the nurse in rehabilitation (Long et al 2002).

Box 5.13 Research relating to nursing, back pain and moving and handling

It was long recognized anecdotally that many nurses suffered from back injuries. However, the full extent of the problem was unclear as it had not been systematically investigated. As such, it was important to try to quantify and measure the size of the problem. To do this, a number of surveys were undertaken by different researchers. A particularly important one was a questionnaire survey of 4000 nurses. The results of this survey were influential as it was found that one in four nurses took time off with back injury and one in three currently had a back injury. The data were used further to try to estimate the size of the problem in relation to the qualified nursing population as a whole. Alarmingly, it was suggested that 27000 nurses could potentially be suffering from back injury and 72000 may have had time off as a result (Seacombe & Ball 1992).

The high rates of back injury in nurses have been largely blamed on the practice of manually handling patients. Numerous researchers have examined nurses’ moving and handling practices, looking at how nurses handle people and why they approach this activity in the way that they do, especially in light of the 1992 European Union regulations on the manual handling of loads (Health and Safety Executive 1992). Many of these studies have used qualitative approaches, choosing to collect data through interviews with participants. Kane and Parahoo (1994) looked at how student nurses learned about moving and handling. They interviewed 16 nurses, asking – among other questions – whether they would move a client with a staff nurse if she opted to use an unsafe lift; eight students would have conformed to the staff nurse’s decision. This type of research can thus shed light on people’s experiences, behaviours and attitudes.

Different types of research design

In order to begin collecting data to answer a research question, a plan or research design must be decided upon. The research design sets out whether the research approach will be quantitative or qualitative, how data will be collected (data collection tools), where/who data will be collected from (the sampling strategy or sample) and how data will be analysed (Parahoo 1997). Different research questions require that different research designs be used. For example, if the researcher were trying to find out about the effectiveness of a treatment (e.g. does drug A work better than drug B?), it would be most appropriate to use an experimental design such as a randomized controlled trial. Alternatively, if the researcher were seeking to understand people’s thoughts and feelings, a qualitative approach would be used. It is important that the researcher chooses the best research design to answer the research question. There are many different research designs but some examples include:

For a fuller explanation of the many different research designs, data collection tools and sampling strategies, it is important to consult a more in-depth research text (see Further reading).

Sampling strategy

When a study is conducted, it is not usually possible to collect information from every single person so desired because the total target population is too large. For example, in a study on the factors causing heart disease, it would not be possible (due to costs and time constraints) to contact every single person in the UK with heart disease to complete a lifestyle survey. It is therefore necessary to target a smaller number of people from within this total population. This is known as the sample (defined as a subset of the target population).

Like the large number of research designs that may be selected, there are also different ways of sampling that will depend on the nature of the research design. Readers may come across a range of sampling approaches (Parahoo 1997) but further reading will be required to explore these aspects further.

Types of data collection

In the same way that there are a range of research designs and approaches to sampling, there are also a variety of ways of collecting data. These include techniques such as observation, questionnaires, documentary analysis and interviews.

Observation

Observation focuses on the researcher ‘seeing’ and perhaps experiencing what happens in a particular context by watching, documenting and then analysing events of interest. The researcher may either take part in the activities being observed (participant observation) or may ‘sit at the sidelines’ at a distance (non-participant observation). Box 5.14 includes material from observation during a study of the nurse’s role.

Box 5.14 The nurse’s role – observations of a staff nurse working on a rheumatology rehabilitation ward

Explaining and preparing

What to expect – ‘You will be fully assessed by all members of the MDT (multidisciplinary team), the physio, the OT (occupational therapist), the podiatrist, the doctors’

Educating

‘Continue with exercise, but don’t overdo activity on your legs’

Side-effects of drugs; benefits of medication (e.g. on sleep pattern); suggesting more regular use of pain killers

‘I’ve never really discussed any pain relief with anyone. No one takes it seriously, they just back off and make you feel like you are whinging’

Staff nurse queries if they have ever been in touch with a self-help group … explained the value (information about new treatments new ideas, education, mutual support), help in applying the TENS machine

Referring

To physio; to welfare rights officer to help with re-employment and OT; passing on information (to doctor, pharmacist).

[From Long et al (2001). Examples reproduced with kind permission from the Nursing and Midwifery Council.]

Questionnaires

Questionnaires are a common way of collecting data and consist of a preset list of written questions to be answered, either in writing or verbally, by the respondent. For examples of different types of question used in questionnaires, see Blaxter et al (1998) in Further reading.

Documents

Documents may also be a useful source of data. Examples of documents include patient care records, policy documents, historical documents archived in a library, census statistics and reports, company annual reports and institutional documents.

Interviews

Interviews involve talking with and listening to people, asking questions and discussing issues with them. Interviews may be structured or unstructured and can be undertaken face to face or over the telephone. They may occur on a one-to-one basis or may be conducted as a focus group with up to eight people.

Ethical issues and research

All research projects raise ethical issues whether they involve direct contact with people or the use of documentary evidence. To ensure that ethical issues are fully addressed, the plans for all research projects in health and social care must be submitted to Research Ethics and Governance Committees for review prior to the project being carried out. In addition, nurses conducting their own research, assisting other researchers or caring for people involved in research studies, need to do all that they can to ensure that the research they are involved with is of the highest standards.

A number of key ethical principles must be considered in relation to research. The first is the principle of ‘respect for persons’ (see Ch. 7). This means that researchers must protect individuals from harm and protect their autonomy. Research participants must be able to make informed choices and decisions about what happens to them, such as whether or not to take part in research. Thus, researchers must ensure that informed consent is gained prior to including anyone in a study (Box 5.15) (see Chs 6, 7).

Informed consent in research

Imagine you are a research nurse responsible for recruiting people into a study.

In some situations, individuals may be unable to make an informed decision to take part in a study due to illness, age or conscious level. Special measures must be taken in this situation. Confidentiality must also be ensured in order to protect the dignity of people taking part in research. This means that, for example, personal information, or views expressed by respondents, or photographic images must be stored safely to comply with the 1998 Data Protection Act (DH 1998). Effective ways of protecting and disguising the identity of participants must also be devised, as respondents should be assured of anonymity (Royal College of Nursing Research Society 2003).

Appraisal of the evidence

The ability to identify good quality evidence requires the development of critical appraisal skills. Practitioners need these skills in order to differentiate weaker evidence from stronger (Box 5.16, p. 138). This involves developing a critical awareness that will enable practitioners to read, digest and understand the evidence.

Box 5.16  EVIDENCE-BASED PRACTICE

EVIDENCE-BASED PRACTICE

Evidence on the effectiveness of cranberry juice

Refer to Boxes 5.4-5.6 (pp. 127 and 130) based on ‘John’ and the use of cranberry juice. You need to think about this scenario and the idea of clinical effectiveness and the EBP cycle (see Fig. 5.1).

This section provides an introduction to the process of critical appraisal and an example of an appraised article. Once practitioners become familiar with the appraisal process they find that their skills will advance and develop over time.

Critical awareness

While many practitioners are able to read the findings from a research paper, most may have problems evaluating the relevance of the findings for their own practice (Avis 1994). Often, people will read the abstract, introduction, findings and conclusions of a research paper, while ignoring the section on research methods. Unfortunately, by ignoring the methods section of the article, it is possible that vital details that provide insight into the strengths or weaknesses of a paper will be missed. This is important when considering the application of findings to practice.

Box 5.17 provides an overview of how important details could be missed. This example highlighted the need for Staff Nurse Brown to read the article in full. Because she did not read the research methods section, she was unable to answer Staff Nurse Sanchez’s questions about the sample size and variables which may have significantly influenced the findings of the study. For example, it is known that smoking increases the risk of breast cancer. If any of the women smoked in either group, then this could have influenced the findings. For example, in this case, soya acts as the control variable: women in the non-soya diet group may have smoked more than the women in the soya group which would have led to an increased risk in developing breast cancer irrespective of whether they consumed soya in their diet. Smoking is therefore a confound-ing variable that should have been taken into account.

The challenges of critically appraising research

Staff Nurse Brown: ‘I read an article yesterday which said that eating soya products is good for you’.

Staff Nurse Sanchez: ‘Yeah… Really, what did it say?’

Staff Nurse Brown: ‘Well, it said that something found in soya can help to prevent breast cancer.’

Staff Nurse Sanchez: ‘So how did they come up with that conclusion?’

Staff Nurse Brown: ‘Oh easy really, they compared the diet of a group of women who had breast cancer with the diet of a group of women who didn’t have breast cancer and the findings showed that the women who didn’t have breast cancer ate more soya products.’

Staff Nurse Sanchez: ‘But how many women did they look at?’

Staff Nurse Brown: ‘Erm… I think about 100.’

Staff Nurse Sanchez: ‘Well, did any of the women smoke?’

Staff Nurse Brown: ‘Oh, I’m not sure, I think I missed that bit out – it was a lengthy article.’

Components of critical awareness

According to Hamer and Collinson (1999), to develop a critical awareness practitioners need to be able to reflect on their practice and identify questions about their own or others’ practice in a non-biased way. Finding and then appraising evidence to answer their question is part of the evidence-based cycle. Appraising evidence is not just about identifying a paper’s flaws, but determining the value or otherwise of the paper to their area of practice. To illustrate this, Box 5.18 includes an extract from a journal club meeting through which practitioners appraised and discussed a paper.

Box 5.18 Extract from a journal club meeting

Barrett et al (2002) used a transparently designed RCT to examine the effectiveness of Echinacea for early treatment of the common cold. Initially, it was thought that the trial addressed a clearly focused issue in terms of the population studied, intervention used and outcome measurements. However, following appraisal, concerns were raised about the pharmacological preparation of the intervention, the representativeness of the sample and the validity of the outcomes measured.

Appraisal

Anecdotally, it is argued that Echinacea is effective in the treatment of colds for a compromised population, e.g. people who are immunosuppressed or frail older people. The population of healthy students under study in this trial used self-reported symptoms as outcome measures. This raised some concerns about the nature of the outcome measures used and the aims of this trial.

In relation to the self-report outcome measures, the group felt that there was too much variation; however, it was also argued that this might be the only way to measure cold outcomes. It was noted that some of the sample took other non-protocol medication although this was accounted for in the statistical analysis as one of the potential confounders.

The paper was well presented and utilized clear graphs to describe some of the findings which were thought to be useful. Some ambiguous statements were made in the paper which required clarification, e.g. the authors stated that ‘nearly all’ the participants rather than the number of participants. The group felt that the number of subjects needed to be clear when discussing the analysis of the data.

Outcome

The discussion above demonstrates some of the key attributes outlined by Hamer and Collinson (1999). The group used critical appraisal guidelines to appraise the paper and, as a result, key questions about the research design were asked. This resulted in some aspects of the paper being scrutinized more carefully and an informed decision made about the trustworthiness and appropriateness of the paper to their own areas of practice.

[Based on Barrett et al (2002)]

Newman and Roberts (2002, p. 87) suggest that the purpose of critical appraisal ‘is to decide whether the quality of a research study is good enough for the results it provides to be used to answer a question posed by a healthcare practitioner or patient’. So, to summarize, critical appraisal empowers practitioners to identify quality evidence and make sense of the evidence in terms of its relevance to the question posed and the individual’s practice.

Strategies to develop critical appraisal skills

The development of an evidence-based culture within the NHS is being supported by the government’s modernization agenda. This has involved the introduction of clinical governance, NSFs, NICE and other guidelines used to help standardize care. As part of this, it is also recognized that NHS staff such as nurses, midwives and health visitors need better critical appraisal skills (DH 1997) to enable them to use evidence in practice. One way of developing practitioners’ appraisal skills is through the use of journal clubs. Journal clubs are an ideal way to develop appraisal skills in a friendly and supportive atmosphere. Journal clubs have expanded and there are now online journal clubs as well as local clubs (see ‘Useful websites’, pp. 144–145).

Developing critical appraisal skills

Critical appraisal skills are essential to the delivery of EBP and a variety of critical appraisal tools have been designed to help the reader decide on the quality of research papers (Box 5.19). These appraisal tools usually take the form of a series of questions that the reader needs to ask of the paper.

Box 5.19  EVIDENCE-BASED PRACTICE

EVIDENCE-BASED PRACTICE

What evidence and how to appraise it?

Look at the evidence on cranberry juice you have already located (see Box 5.16).

Student activities

Crombie (1996) recommended that checklists/tools be used to review a paper or evidence to help identify its value. He suggested that this would assist in detecting any flaws in the paper, question its credibility and trustworthiness, and identify the potential impact on the area of practice. Critical appraisal should focus on ascertaining the value of the paper to an area of practice, rather than on rubbishing papers. A number of other tools/guidelines have been developed to help with the process of critical appraisal (Box 5.20). Some of these are available online and can be downloaded free of charge.

Box 5.20 Examples of critical appraisal tools and guidelines

Questions to ask when critically appraising a research paper

The first and perhaps most crucial stage in the process of critical appraisal is that of identifying a clear research question. If this is related to the stages in the evidence-based cycle, it becomes clear why this is so important. If the question is not clear at the outset, then the rest of the research process may be confusing to the reader.

There needs to be a good reason for undertaking a study and it needs to be transparent to the reader. Some would argue that if a study has been done before, then why repeat it? Others believe that it is unethical to repeat a study which has already been done or which has already demonstrated the effectiveness of an intervention. Greenhalgh (1997) argued that the reader needs to know what type of study has been done and whether the research design was appropriate to meet the study aims. The research process stages need to be transparent throughout the paper to enable the reader to understand and make full use of the findings. If the design used was inappropriate, then this may lead to confusing findings that do not address the aims of the study.

Crombie (1996) suggests that research papers are organized into four main sections. This includes the introduction, methods used, results gained and discussion of findings. There are also other questions that the practitioner needs to consider (Crombie 1996) (Box 5.21).

Box 5.21 Questions to consider when reading a research paper

How?

To ascertain how the study was done, it is necessary to read the methods section. This will explain the methodological approach to the study and rationale for the approach.

Thompson (1999) provides another example of an appraisal tool that uses 11 questions to guide the practitioner through a research paper. The questions are loosely based on the research process and prompt the reader to ask specific questions about the process (Box 5.22).

Critically appraise a research article

Select an appraisal tool and apply it to your articles about cranberry juice. This will help you appraise your article in a systematic way. You may like to do this with a colleague and compare your answers, as well as evaluating the strengths and weaknesses of the two papers you appraised.

Appraising different research designs

When appraising different research designs, it is important to identify the stages of the research process carried out by the researcher. As stated earlier, the research process should be transparent. Without this it will not be possible to make sense of the paper, which could limit the application of the findings to practice. In all cases the paper must be relevant to the practice issue. Practitioners need to ask questions that include:

In conjunction with appraising the research process within research papers, there are specific details of each research design that should be sought. In each instance, readers need to look for evidence that the author has considered the methodology chosen and the rigour the researcher has applied to the methodology. This next section briefly explores four different research designs and highlights key points that should be considered when appraising these designs.

Appraising qualitative research (Box 5.23)

Qualitative research attempts to explore the meanings and experiences of individuals or groups about a particular topic. For example, practitioners may have read about mood disorders and understand the effects and treatment. But what is it like to have depression? Only those who have suffered with the condition will be able to describe their experiences. Qualitative research provides an ideal method to explore these thoughts and feelings and helps gain insight into the experiences of people. In order to obtain the rich, in-depth data required to explore perceptions and feelings, the researcher becomes the data collection tool. In relation to qualitative work, the role of the researcher is important and should be clearly described, as their role is pivotal in the collection of data and analysis of the findings.

Appraising systematic reviews (Box 5.24)

Systematic reviews are conducted by following a series of logical steps and bring together the results of several studies on a single topic to provide an overall conclusion. Droogan and Cullum (1998, p. 14) state that ‘systematic reviews reduce large quantities of research into key findings in a reliable way and offer a means of enabling healthcare professionals to keep abreast of research’.

In a systematic review, research evidence about a specific topic is located through a comprehensive search strategy. The evidence located is then appraised using validated appraisal tools and, finally, credible reviewers will summarize the findings for the reader. Strict inclusion and exclusion criteria are normally used to help the reviewers decide on the best sort of papers to be included in the review. Systematic reviews embrace international literature, including published and non-published work, and may take up to 2 years to complete. They are, therefore, considered to be a very valuable form of evidence. Systematic reviews of quantitative research (RCTs in particular) are designated as the ‘gold standard’ of evidence within the hierarchy of evidence. This is reflected in many guidelines currently in use, e.g. the National Service Framework for Older People (DH 2001b, pp. 14–15).

Appraising randomized controlled trials (Box 5.25)

Randomized controlled trials (RCTs) are an important quantitative method and are another type of evidence considered to be valuable. In establishing cause and effect of treatments, they attempt to manipulate variables within a control and an experimental group. As a result, they reduce researcher bias, introduce control and limit the confounding variables. Many believe that RCTs are a good type of evidence because they are reliable and it is often possible to generalize from the findings if the study is well designed.

Box 5.25 Points to look out for in RCTs

Appraising survey designs (Box 5.26)

Surveys (quantitative method) are large-scale questionnaires of a selected population. They can provide details about the demographic make-up of a population or trends in terms of lifestyles. For example, a survey may be used to provide data about how many people smoked in a geographical area.

An example of a survey that you may have been involved with is the Census. This is undertaken every 10 years by the government to find out about the population’s lifestyle status. Surveys use questionnaires to elicit details about a population. Short, closed-ended questions are usually used to uncover a variety of details from the respondent (Box 5.27, p. 141).

Putting evidence into practice

There are important reasons for ensuring that the best evidence is used in practice. Firstly, it is a crucial way of ensuring that people get the treatments and services that are most effective and will have the best health outcomes. EBP is also an essential way of ensuring that the public funding that supports the NHS is used wisely and that the treatments and services offered are cost effective. Together these factors lead to the provision of clinically effective care. Clinical effectiveness can be defined as ‘the extent to which specific clinical interventions, when deployed in the field for a particular patient or population, do what they are intended to do. That is, maintain or improve health and secure the greatest possible health gain from the resources available’ (NHS Executive 1996, p. 2).

Many people are responsible for ensuring that research and other forms of evidence are used in practice. This includes practitioners, managers, researchers, educators and service users. For practitioners, there is a professional responsibility for using the best evidence in practice and to ensure accountability in their practice (NMC 2002) (see Ch. 7). As such, nurses must attempt to keep up to date with developments within their field in order to fulfil the continuing professional development requirements for periodic registration (see Ch. 7). By using the right evidence in practice, practitioners can be more confident in the care that they deliver and the clinical decisions that they make, thus enhancing their clinical accountability (Joyce 1999).

In order to support practitioners in using evidence in practice, managers must also develop supportive structures within organizations to promote a culture where evidence is valued and to enable practice to be changed in light of evidence (Le May 1999). They must base decisions about, for example, services, staffing and treatments on the best available evidence.

Researchers have an important role in generating new knowledge and evidence for practice. However, they must be able to share this information with the practitioners who need to use it. This is dissemination and is usually done by publishing research findings within professional journals.

Educators may work with both practitioners and researchers and can help to teach the principles of EBP and support practice development. They may also be involved in research projects.

Finally, but importantly, service users also have a role in ensuring that evidence is used in practice. It is important that service users do ask about the best treatment or care options that are available and are able to challenge practices that they are concerned about.

Challenges to the use of evidence in practice

Unfortunately, despite the vast amount of evidence now available, there are many challenges to using it in practice. In many areas of the NHS, decisions are made on the basis of custom and practice that can lead to outdated or ineffective treatment and care being offered. For example, despite evidence to suggest a shorter fasting time for some types of surgery, people are still fasted preoperatively for too long. This type of practice does not use research to support or change practice. This is often described as the ‘research–practice gap’.

There are many reasons for the failure to use research in practice. These often relate to the attitudes of practitioners who may be satisfied with routine practices. However, organizational pressures, a lack of managerial support and educational deficiencies can also inhibit practice development (Joyce 1999). In other cases there is a lack of high quality research to guide practice. This means that practitioners have no option but to follow their own experience. The quality of research evidence may also cause problems as different research studies often provide different results that may be conflicting or confusing (Joyce 1999). Research studies may be small scale, methodologically flawed or produce findings that are difficult to implement. It is also a problem when research seems irrelevant to practitioners who would have asked different research questions had they been involved in the design of the research. More recently, it has been recognized that a lack of structure or systematic approach to the research agenda has made it difficult to use evidence in practice.

Other challenges arise from practitioners’ lack of time, poor access to libraries and inadequate literature searching and critical appraisal skills.

Overcoming the challenges is essential to improving care and service delivery. The most important approach is to improve the communication or dissemination of research findings. Unfortunately, while publication in academic and professional journals is the usual approach to sharing research information, this type of dissemination remains relatively ineffective and does not necessarily lead to changes in practice.

Earlam et al (2000) proposed a framework relating to the EBP cycle to consider when planning making changes in practice (Box 5.28).

Box 5.28 Framework for planning changes in practice

[Based on Earlam et al (2000)]

Using systematic reviews

Systematic reviews of particular topics aim to collate evidence into a more usable form. Different studies on the same topic can produce conflicting results, making it problematic to use the information. Combining the results of studies results in clearer implications that are easier to put into practice.

The use of guidelines and integrated care pathways

Similarly, clinical guidelines and integrated care pathways (ICPs) pull together evidence and set out what services and treatments people should receive (see Chs 3, 14). ICPs are designed to guide practitioners through a predicted ‘patient journey’. Guidelines have been used for many years in the NHS, e.g. guidelines for routine antenatal care.

By providing service users with information of what care they should expect to receive, the previously passive patient–practitioner relationship becomes more active and equal. By providing service users with access to information, it is hoped that they will be more empowered to take responsibility for their own care. However, it is also important to remember that not all guidelines/ICPs are reliable and evidence based and the following key points should be considered before using one:

All of these points should be present in a guideline so that practitioners can be reassured of the guideline’s evidence base and reliability (Box 5.29)

Integrated care pathways (ICPs)

Role of government policy