Chapter 1 Understanding health and health promotion

Introduction

The health White Paper, Saving Lives: Our Healthier Nation (DH 1999a, Section 11.14) states that nurses, midwives and health visitors play a crucial role in promoting health and preventing illness. People have close contact with health professionals at key points in their lives – in infancy, during adolescence, pregnancy and childbirth, and in sickness and older age – creating significant opportunities for health promoting interventions.

The Code of professional conduct: standards for conduct, performance and ethics (NMC 2004) states that nurses must protect and support the health of individual patients, clients and the wider community (see Ch. 7). To achieve this, it is important for nurses to have an understanding of their own and others’ health definitions and beliefs. Apart from increased self-awareness, nurses can better understand and relate to their patients and their health and illness behaviour.

Nurses also need to know the factors that affect health and health beliefs in our increasingly multicultural society. This allows accurate assessment of care needs, the planning of sensitive care and the targeting of relevant information. The ultimate aim may be to help people change their health-related behaviour. Furthermore, the increasing focus on evidence-based healthcare means that nurses need to have an understanding of how and why health and illness are measured.

This chapter lays the foundation for the rest of the book by discussing definitions of health, models of health and illness, health beliefs, attitudes and values, factors influencing health, health promotion and health education, measuring health and illness and illness behaviour. It is important to consider the different terms used to describe people in a variety of health and social care settings. Adult, mental health, children’s and learning disability nurses use language that gives clues to their underlying values and assumptions of power and passivity about the person in receipt of care (Ch. 7):

Definitions of health

Before reading this section you should undertake the activity in Box 1.1.

Your view of health

The word ‘health’ is derived from the old English word hael meaning whole and, despite being the subject of much research, it cannot be neatly defined. There is no universal definition of health as everyone has their own idea of what it means. When asked to define ‘health’ in class or during research, people may highlight the physical functioning of their body, their ability to carry out tasks, feeling content and happy or even respond in terms of relationships with family and friends. In other words, health is multidimensional, composed of different but interrelated dimensions.

Dimensions of health

Six dimensions of health are usually described, five at an individual level surrounded by a further one at the level of society:

The dimensions of health are interrelated and problems in one area may well affect another. A social dimension issue, e.g. a relationship problem, may cause mental health problems. A person with a chronic physical illness may develop an accompanying mood or emotional problem. Societal issues such as poverty and low income determine people’s diet and lifestyle, affecting their physical health. It is important to recognize that the relatedness of the dimensions is so strong that it is artificial to try discussing them as separate issues (Box 1.2).

Dimensions of health

Holistic health

Nurses applying this multidimensional approach to healthcare need to assess all aspects of health and consider each patient/client as a whole person (see Ch. 2). This is called a holistic approach and derives from the Greek word holos meaning whole. Kerr (2000) reminds us that a holistic approach to nursing care is based on ancient beliefs that the spirit is a legitimate focus for nursing care as much as the body.

The body as a machine

During assessment interviews or other interactions with people, it is common for nurses to hear descriptions related to the physical dimension of health, where anatomy and physiology are described in an oversimplified way, comparing the body to the workings of a machine. This is called mechanistic functioning and descriptive words commonly used include pipes, blockages, tubes, plumbing, waterworks, ticker and pump. This type of comparison is also used by people to describe the workings of the mind or brain, using words such as wheels or cogs turning, whirring, ticking or breakdown. You should now try the activity in Box 1.3.

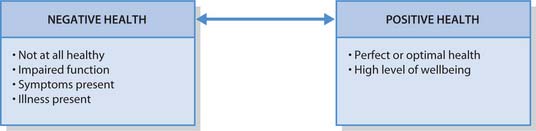

The continuum of health

Figure 1.1 shows how health can be viewed positively or negatively with extremes of positive and negative health states at opposite ends of a health continuum. This reflects the reality that health is much more complex than merely ‘I’m ill’ or ‘I’m not ill’. The continuum allows for movement along the line, reflecting the dynamic nature of health, which varies over time, with age and stage of development and changing circumstances.

Mental health as a continuum

The idea of a single continuum may be seen as unhelpful in mental health. Some people experience high levels of well-being as a symptom of mental illness. For example, a person may experience elation arising from a bipolar mood disorder and would report feeling ‘great’. Tudor (2004) describes the use of the two continua concept where one axis represents mental health and well-being and the other mental ill-health.

Positive and negative health

Words indicating positive health imply the presence of positive and additional qualities such as fitness, wellness or well-being. The positive aspect of health tends to be less dominant, with a tendency to describe health states in a negative way, not focusing on positive health but instead on the absence of disease. For example, describing health as being free from the symptoms of illness or not having a medically defined condition – ‘I don’t have any major illness so that means I’m healthy’. Words indicating negative health states include disease, illness, deformity, abnormality, ill-health, injury, disability, handicap, mental distress or disorder.

It is interesting to note the large number of words used to indicate negative health compared to the few describing positive health states – wellness, well-being, fitness. The word ‘disease’ tends to be used in an official way by doctors, nurses and others for physical conditions with observable physical changes. However, like health, illness cannot be easily defined and is often described as a subjective experience, personally defined by each individual.

WHO definitions of health

The most well-known definition of health is that of the World Health Organization (WHO 1946): ‘Health is a state of complete physical, mental and social well-being and not merely the absence of disease or infirmity.’

This definition has many strengths and it:

However, it has been widely criticized. Some of the criticisms centre on the word ‘state’ which implies a lack of change and does not fit with modern views that health is dynamic, changing with life circumstances. The word ‘complete’ seems to make this an absolute statement and one which, although idealistic, is unrealistic and unattainable. Lastly, the authority of the WHO to define health has been questioned, as it is acknowledged that everyone has their own definition.

Although the original 1946 definition is still commonly quoted, the World Health Organization amended their definition of health in the Ottawa Charter (WHO 1986) to:

Health is the extent to which an individual or group is able to realize aspirations, to satisfy needs, and to change or cope with the environment. Health is, therefore, seen as a resource for everyday life, not the objective of living. Health is a positive concept emphasizing social and personal resources, as well as physical capacities.

The 1986 definition remains valid today and is considered to be realistic in comparison to the unattainable ‘ideal state’ of the earlier definition. This definition focuses on health as enabling adaptation to change and emphasizes the dynamic nature of health, the importance of social aspects of health and the link between health and economic productivity. The WHO definitions of health (1946, 1986) are only two of many, and Seedhouse (2001) summarizes the vast range of health definitions into four major groups (Box 1.4).

Defining mental health

Mental health problems are widespread in society (see Box 1.5). Despite these problems being so common, there is a lack of awareness about mental health among the general public and perhaps even among health professionals. Check your awareness of mental health by carrying out the quiz in Box 1.6.

Box 1.5 UK mental health – what are the issues?

The Choosing Health consultation (DH 2004) showed that:

[Resource: Alexander A 2001 Mental health awareness quiz. Napier University, Edinburgh (unpublished)]

Mental health awareness quiz

Student activities

The quiz is designed to test your knowledge of mental health and to help you think about your attitudes to people with mental health problems. Circle your response to each question.

Mental health problems may be the most common reason for people visiting their GP yet mental health remains difficult to define. It is common to define mental health subjectively, i.e. as something each person defines individually. Barker (2003, p. 7) says that ‘mental illness and mental health … possess no clear, accepted definition. However, they are used in everyday conversation as if their meaning is unambiguous’. Mental health can be taken to mean the opposite of mental illness or even a state of well-being.

It is interesting to note that there is no WHO definition of mental health or mental illness. Instead they use the term mental disorder, which implies a clinically recognizable set of symptoms or behaviour associated in most cases with considerable distress and substantial inter-ference with personal functions.

Many authors have tried describing mental health as one or more of the following:

The Department of Health (2001a) describes the importance of mental health and well-being to overall health and productivity and defines mental health as:

Lay and professional definitions of health

Lay definitions of health refer to the ideas, beliefs and opinions of ordinary members of the public. Studies into lay people’s definitions of health show that people perceive that health can coexist with even serious disease. It is only the last group of theories in Box 1.4 that allows for this, the first three groups must have absence of illness and disease. Professional definitions of health arise from people ‘educated in health’ such as nurses, doctors, allied health professionals (AHPs) or from official sources, e.g. government experts and agencies. Lay and professional definitions of health vary considerably and may result in differing expectations, lack of understanding or even conflict in issues of relationship, diagnosis, treatment and care. Box 1.7 shows an example of lay and professional conflict.

Lay and professional conflict

Jim is 28 years old and has a history of mild asthma going back to childhood. He has had several episodes of bronchitis in the past which have always responded well to treatment with antibiotics. He smokes 30 cigarettes a day.

Jim visits his practice nurse with a heavy cold and a sore throat and requests a prescription for antibiotics. The practice nurse explains that since his cold is caused by a virus, she will not advise antibiotics. Instead she starts asking about his smoking habits.

Models of health and illness

The word ‘model’ has many meanings but in the study of health and illness refers to a conceptual framework or a perspective, a way of viewing or thinking about health and illness which informs research or practice (Seedhouse 2001). The implication is, therefore, that there may be as many different models in this area as there are different ways of thinking about health and illness. The most common models of health and illness are medical, social and patient-centred.

The medical model

Many health professionals ascribe to the medical model, also known as the biomedical model, which tends to focus on illness rather than health. It has tended to be dominant, although this is now changing. The medical model is underpinned by the growth of scientific thinking, technological progress and research that has developed from the 18th century to the present day. The focus is on being objective when identifying physical problems.

Observed symptom clusters lead to diagnosis, which in turn determines treatment options. Cure and repair are emphasized, with treatment often involving drugs or surgery. The intention is usually to remove the identifiable cause of the problem, returning the patient to a ‘normal state’. The medical model assumes that a diagnosis is not valid unless made by expert practitioners. A further assumption is that patients are relatively passive during the process.

Mental health language and the medical model

Foucault (1973) believed that use of language is crucial in determining the way people think and therefore that there could be problems in the use of medical model terminology in the areas of mental distress or mental health problems. The phrase ‘mental illness’ tends to reflect the medical model, which is neither accurate nor helpful when applied to problems that are often largely social or behavioural. Even use of the adjective ‘mental’ has been criticized as it relates to the mind rather than to the brain or even to abnormal behaviour where many problems might manifest. It is more accurate to use the term ‘mental distress’ which fits with modern thinking and is usually preferred by clients.

The social model

Whereas the medical model tends to focus on causes of illness within the individual, the social model considers the society in which the individual lives. This approach arose in the 19th century from the idea that improved health comes from improved environmental and living conditions, e.g. better housing, public health programmes and improved sanitation. The language of the social model is not of symptoms but instead uses terms including barriers, exclusion, distress and disability.

The patient-centred model

Yet another view of health and illness is the patient-centred or client-centred model. It derives from Carl Roger’s (1951) work on person-centred therapy and is a dominant model in modern healthcare, especially in mental health, learning disability and complementary therapies. Of key importance in this approach is the patient’s own perception of their physical or psychological health. This forms the starting point for a more equal, negotiating type of relationship, with the potential for more holistic assessment. This approach is based on the premise that people have significant and unique knowledge of their own symptoms or problems from which healthcare professionals can learn.

Expert patients

The belief that patients can develop successful strategies for coping with symptoms forms the basis of the Expert Patient Programme, a training scheme delivered by the NHS in England since 2004.

The aim is to provide opportunities for some of the 17.5 million adults living with a long-term health condition to take more control over their health. In effect, to become expert patients by understanding and managing their condition better and thereby improve their quality of life (DH 2001b). The programmes involve attending a series of classes based in primary care settings to learn about issues such as symptom management, medication, relating to health professionals, community resources and stress management. You can find out more about expert patients by carrying out the activities in Box 1.8.

[Resource: Shaw J, Baker M 2004 ‘Expert patient’ – dream or nightmare? The concept of a well-informed patient is welcome, but a new name is needed [editorial]. British Medical Journal 328:723–724]

‘Expert patient’ – dream or nightmare?

Health beliefs

Interpersonal relationships are often seen as the central role of nurses (see Ch. 9). It is therefore essential that nurses are aware of, and understand, the beliefs and perceptions of their patients/clients to facilitate relationship forming. Nurses need to have an informed understanding of the diversity of health beliefs because of their significant position as ‘intermediaries’ between medical and lay belief systems, acting as translators of patient/client experience to doctors and vice versa. To accomplish this, nurses need sensitivity to people’s subjective experience of illness and an open-mindedness regarding the limitations of the medical approach (Jones 1994). Contemporary health beliefs are better understood by briefly considering how they have developed over time.

Early health beliefs

Early health belief systems date from 3000bc. The orthodox Chinese system, Ayurvedic medicine and ancient Greek/Roman civilizations were among the first to have a written, systematic categorization of illness for the purposes of diagnosis and treatment. All had ideas of systems in balance or harmony, were person-centred, holistic and made links between health, illness and the individual’s personality, the climate, stage of lifespan and the environment.

Although these belief systems seem like ‘ancient history’, it is important to note that orthodox Chinese and Ayurvedic medicine are still practised by millions of people throughout the world. In general, non-Western ideas of health are becoming increasingly common in UK society. Chapter 10 provides more information about the emergence of complementary therapies.

Religion and health

There has been a long and enduring link between religion, moral behaviour and health. The central idea is that illness may be caused by moral failure or some lapse in good behaviour. There is also the notion that the person may ‘deserve to become ill because they have brought it on themselves through their own actions’ (see Box 7.5, p. 171, for a contemporary example that explores withholding treatment for smokers).

The Latin word for pain, poena, comes from the same root as the word for punishment and the Bible describes pain in childbirth as punishment for Eve’s sin in the Garden of Eden. The idea of illness as punishment for moral failure may seem very old-fashioned yet it is still a commonly held belief in current society (Jones 1994). This kind of thinking about ‘deserving’ illness or being punished for bad behaviour by becoming ill is the norm for children of primary school age. Children’s views of health and illness are considered later (p. 10).

From research into lay people’s health beliefs, it is common to hear phrases like ‘You get what you deserve, people bring things on themselves’ or ‘It’s in God’s hands, everything is for a reason’. Helman (2000) also notes that one common image often used in the press is of acquired immune deficiency syndrome (AIDS) as moral punishment, with sufferers divided into two groups: the ‘innocent’ (children and people with haemophilia) and the ‘guilty’ (everyone else).

Supernatural ideas and health

Centuries ago, when illness arose for no apparent reason, people sometimes believed that someone had wished them harm by thought, the casting of spells or giving of the evil eye (Helman 2000). Belief in special powers and witchcraft were very common in ancient times but are still held by many people in the UK today, especially as its population becomes more culturally diverse. Large numbers of British people, e.g. those of Afro-Caribbean descent, still hold these beliefs. It is therefore important for student nurses and other healthcare professionals to be sensitive to cultural aspects of health belief and related behaviour (Box 1.9).

Culture and nursing practice

Cultural background has an important influence on many aspects of people’s lives, including their beliefs, behaviour, perceptions, emotion, language, religion, rituals, family structure, diet, dress, body image, concepts of space and time, and attitudes to illness, pain and other forms of misfortune – all of which may have important implications for health and healthcare.

(Helman 2000, p. 3)

Strong supernatural beliefs may result in people having feelings of not being fully in control of their own destiny. In some circumstances, this can lead to a type of fatalism, especially if the person believes in an afterlife or in reincarnation. This is a major issue for health promoters as some people may not value the need to change their health behaviours or lifestyle.

Scientific developments and health

From the 18th century onwards, there was rapid development in scientific knowledge accompanied by technological advance. The emphasis was on research, evidence and objectivity and the beginnings of the medical model are based here. The medical model remains the most common professional view, with its current focus on evidence-based practice (see Ch. 5).

By the 19th century, there were two main models of health and illness: contagion and miasma. The contagion model stressed that the causes of illness were through contact or touch, magic, diabolism, lack of discipline and moral control. This was the dominant model until the ‘germ theory’ emerged. Again, although historical, some people still hold notions of contagion in today’s society, e.g. people of strong religious faith, minority ethnic groups.

The miasma model, as espoused by Florence Nightingale in her Notes on Nursing of 1859, centred on belief systems which considered that illness was caused by bad air or smells, poor atmospheric conditions, rotting food and sewage. It followed then that the treatment of illness involved personal and environmental cleanliness, usually involving fresh air, scrubbing, boiling and bleaching. It is still common these days to hear people voice miasma concerns which tend to be about dampness in the air or cleanliness.

Throughout the 20th century and up to the present day, the medical model has grown and remains dominant. Secularization of beliefs has increased so that, for most people, illness tends not to be linked with either moral failure or religious belief. Non-Western notions of health are common, with an increasing interest in, and rise in the use of, complementary therapies (see Ch. 10). All of these advocate holism by stressing that illness is of the whole self, not merely a problem in an aspect of body function. Complementary therapies are now embedded in many mainstream NHS settings.

Current lay health beliefs

The trend is towards a huge diversity of health beliefs in the UK, which is increasingly multicultural. It is therefore inevitable that nurses will care for people with beliefs that are different from their own. The concept of balance or moderation remains common in modern health beliefs and is often expressed as the idea of trade-off, where individuals regulate their behaviour, e.g. ‘I walked to work today so I can have pudding for lunch.’

Categories of lay health beliefs

There is a multitude of common health beliefs noted in this intensively studied area. Blaxter (1990) studied the health beliefs of lay people and observed that these changed according to age, gender, family responsibilities and cultural background. She found young men tended to emphasize physical fitness and function whereas older adults described health as linked to social and emotional relationships. Blaxter (1990) summarized lay health beliefs into 10 categories:

Box 1.10 provides an activity to help you recognize common, contemporary health beliefs.

[Adapted from Greig J 1995 Men talking about health: a qualitative study. Unpublished MSc thesis, Edinburgh University]

Recognizing health beliefs – quotes about health and illness

Student activities

Lay beliefs about the causes of illness

The study of lay theories of illness causation, also known as lay aetiology, refers to people’s attempts to make sense of their own or family experience of illness or disease. They try to describe what has happened to someone and why. Jones (1994) described humans as natural scientists, with an innate drive to understand and ascribe meaning to the world around them. However, lay people usually have limited scientific understanding of the structure and functioning of the body, the causes of disease and the reasons for body malfunction. They may hold logical but incorrect assumptions about the cause of illness (Helman 2000), e.g. cold (temperature or weather) causes a cold (viral infection).

Like the medical model, lay theories of illness are multifactorial, placing the causes in one of the following four sites: within the individual, in the natural world, in the social world or in the supernatural world (Box 1.11). The first two explanations relate to the Western industrialized world while the last two usually arise from non-industrialized or rural communities (Helman 2000).

Box 1.11 Lay beliefs about the causes of illness

[Adapted from Helman (2000)]

Children’s health and illness beliefs

There is distinctive progression in children’s understanding of health and illness-related concepts with age. Children’s understanding corresponds to their stage of cognitive development, using Piaget’s theoretical framework as comparison (see Ch. 8). ‘Draw and write’ techniques are commonly used to explore children’s health perceptions and, by the age of 6, children may have already developed distinct ideas about the causes of health and illness.

Preschool children see illness occurring as if by magic and sometimes perceive it as punishment for past misconduct and may even believe that healthcare professionals intentionally set out to hurt them (Hart & Chesson 1998). They know the names of some external body parts but internal bodily functions remain largely unknown.

Children aged 6–7 years tend to have a view of health which describes healthy people as being young, sporty, happy, smiling and actively involved in outside activities (Kerr 2000). In this age group, children may believe that illness is caused by a single factor, often a germ (Hart & Chesson 1998). They are familiar with the names for external body parts and some internal organs and bodily functions. Little is known about children’s concepts of mental health, other than feelings related to being happy or sad.

Children aged 9–10 years understand the principles of germ transmission but many believe that all illness is caused this way, even cancer and eczema (Hart & Chesson 1998). Given this, it follows that they sometimes have difficulty in understanding prescribed treatment. Perrin and Gerrity (1981) noted that medical terms were frequently misinterpreted by children, giving examples of oedema perceived as ‘demon in my belly’ and diabetes perceived as ‘die of betes’.

Children aged 11 years have begun to develop a more detailed understanding of health and illness and by 13 years grasp the complexity of illness with its multiple possible causes. They are able to discuss the complex interplay between biological, lifestyle and environmental factors that influence health and illness (Helman 2000). They can readily identify health determinants (see p. 14) and understand health-damaging behaviours such as passive smoking (Kerr 2000). They have studied at school and can relate, for example, aspects of body functioning to the components of a healthy diet. They are also more likely to appreciate the impact of psychological factors, grasp the notion of drug-related side-effects and the time delay often experienced in response to treatment (Hart & Chesson 1998), e.g. it may take several days before anti-biotic medicine is seen to ‘work’.

In all age groups, the most common symptoms described as ill-health by children were fever, headache, diz-ziness or rash (Helman 2000). Thermometers feature strongly in children’s ‘draw and write’ descriptions. Children perceive fever to be the key symptom used by their parents to determine whether or not they are ill. This reflects their own experience, which is usually limited to common illnesses of childhood such as viral infections.

It is also noteworthy that, unlike adults, positive aspects of illness feature strongly in children’s drawings and descriptions of being ill. These include staying off school, being the centre of attention, having visitors, treats and special foods.

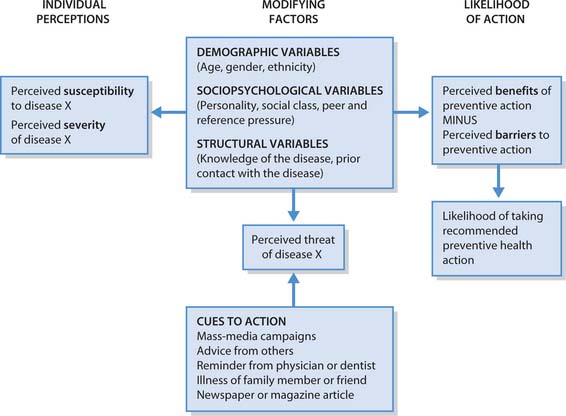

Becker’s health belief model

There are many health belief models that provide an overview of the factors influencing health beliefs. One is the health belief model (HBM) devised by Becker (1974) to explain how people behave in relation to their health. A person’s beliefs about whether they are likely to contract an illness and the degree to which they see an illness as being severe can be considered as a perceived threat and is the basis by which their behaviour is influenced. The HBM (Fig. 1.2) has been shown to be highly predictive of health behaviour.

According to the HBM, participation in preventative health behaviour, i.e. behaviour which should decrease the risk of illness, is predicted on the basis of the following:

Values in health are discussed below and Chapter 7 considers values and ethics in nursing practice. Originally, the HBM had four key beliefs affecting the central concept of health motivation. Later, the HBM was extended to include the fifth key belief: perceived self-efficacy, which refers to a person’s confidence in their ability to make/maintain a change in health behaviour. Modifying factors may include sociocultural factors, age and gender. It suggests that people will consider the advantages and disadvantages of engaging in positive health behaviour, even if the existing behaviour is not changed, and relies on a particular cue for action to be taken.

The nurse’s role and application of the HBM

Nurses can help people to change their health behaviour in many ways. It is important to realize that any contact with health professionals, however brief, is often a ‘cue to action’ in itself. It is important to use this contact to discuss health behaviours – people expect it and may be surprised if the subject is not broached. Nurses and other health professionals have high credibility with patients/clients and a brief discussion may be all that someone, who has been considering positive health-related change, needs to move forward and actually make a change.

There is a need for nurses to offer factual, balanced health information that clearly indicates individual susceptibility or risk. The language and images used are important considerations, especially in children and people with learning disability. Shock tactics, moral judgements or emotive language are unhelpful and may alienate patients/clients. Interaction between nurses and patients/clients should stress not only the benefits of preventative health behaviour but also offer encouragement and strategies for dealing with barriers to change.

Attitudes, values and behaviours

This is a complex area of social psychology important in nursing and health promotion since attitudes combine aspects of people’s values, feelings and beliefs. An attitude is defined as a relatively stable tendency to respond consistently to particular people, objects or situations. The use of the word ‘stable’ rather than ‘fixed’ implies an ability of the attitude to change or be changed. An attitude represents a person’s general feelings towards someone or something. It can be negative or positive, strongly held or weak. Attitudes have three components, summarized as ABC:

Nurses are often involved in assisting patients/clients to change their health-related attitudes with the aim of causing a positive behaviour change. For example, to explore dietary issues with a person newly diagnosed with diabetes, the nurse needs to:

To ensure success, all of this must be done sensitively and with the person as participant as possible in the interaction. Care with use of language, visual aids and the opportunity for rehearsal would be of particular benefit to people with a learning disability (Box 1.35, p. 27).

Health education for people with learning disabilities

Gates (2003) identifies key considerations when planning health education for clients with learning disabilities. Activities should be:

Public and private attitudes

An attitude openly expressed by a person in public is usually called an opinion. Attitudes may or may not be predictive of people’s behaviour. Publicly stated opinions may, or may not, reflect a person’s true, privately-held attitude that tends to be divulged only to trusted and close family members and friends. People may express different attitudes to researchers in an attempt to help the interaction, give a more ‘textbook’ answer or appear more acceptable. An example of this in nursing might be when carrying out an admission assessment, a person who drinks heavily may purposely underestimate their alcohol units consumed per week and describe themselves as a social drinker.

Cognitive dissonance

Festinger’s (1964) idea of cognitive dissonance is based on the three components of attitudes mentioned above. It is common for a person who knows and understands the adverse effects of smoking (cognitive component) and who has poor self-esteem because they smoke (affective component) to continue to smoke (the behaviour). This is known as smoking dissonance and is experienced as psychological discomfort or guilt because of the inconsistency that exists among the three components of an attitude.

Festinger (1964) suggested that it is usual for a person feeling this discomfort to have a drive to resolve the conflict between the different components of their attitude and therefore reduce the dissonance experienced. Cognitive dissonance therefore can be viewed as a possible precursor of a positive health-related behaviour change. If nurses or other healthcare professionals perceive a person’s cognitive dissonance, then this may be a first step along the road to attitude change and, possibly, behaviour change. Mass media campaigns may purposely seek to induce or increase dissonance for this very reason, e.g. the British Heart Foundation anti-smoking advertisements which verged on the physically revolting, using emotive images of a fatty substance oozing out of cigarettes. It is important to note that this type of mass media campaign is not understood by a large proportion of people with a learning disability (NHS Health Scotland 2004).

Values

Attitudes are underpinned by values, which are broad and less specific than attitudes. Values underpin an individual’s ‘philosophy of life’ which are then applied to everyday life. They may relate to moral, ethical or religious issues as well as health, gender roles, family life and the environment. How much a person values their health is a key part of the health motivation section of Becker’s health belief model (see Fig. 1.2).

A person’s value system is composed of broad beliefs developed through early learning, upbringing and socialization within the family and later at school, with peers and through life experiences and work. The cultural context in which this develops is also very important.

Each value may have multiple attitudes associated with it. Although it may be possible to cause attitude change, it is more difficult to change a person’s value system as it is an integral part of their early upbringing and life experience. For example, values relating to moral conduct in life may have associated attitudes about crime and punishment, sexual behaviour, marriage and the rearing of children.

Stereotyping

Although the term ‘stereotype’ originally referred to a printing stamp used to make multiple copies, it began to be used in the early 20th century to describe the way society categorizes people by ‘stamping’ them with a set of characteristics. Stereotypes are underpinned by direct expressions of beliefs and values and may offer a shorthand way to generalize about a person or a group of people (Box 1.12).

Stereotyping

Discriminatory behaviour can result from negative stereotypes and should be avoided by nurses. It is important to be non-judgemental and form effective relationships with all patients/clients. Nurses must be self-aware and recognize stereotyping both within themselves and in everyday life. Carry out the short quiz below to find out if you hold negative stereotypes.

Student activities

It may seem natural to try to classify people in society but stereotypes are to be avoided in nursing because they do not acknowledge individual differences and are usually oversimplified and negative. Stereotypes form the basis of prejudice, or unfavourable opinion, formed against a person or group of people, usually based on the following characteristics:

Fear of the unknown, e.g. of minority groups, may fuel stereotypes. When people are judged on stereotypes and there is resulting prejudice, this is known as discrimination.

People with mental health problems have historically suffered serious discrimination and can be considered one of the most socially excluded groups in British society. Public fear of mental illness has been fuelled by well-publicized cases in the media where a mentally distressed person has behaved violently. However, two-thirds of all media reports on mental health issues portray a direct association between mental distress and violence. This shows how stereotypes are often untrue because, statistically, people with mental health problems are no more likely than anyone else to engage in violent behaviour. In addition, data show that people with mental distress are much more likely to harm themselves than other people. Discriminatory behaviour includes:

The result can be segregation and isolation for individuals and, in extreme cases, discrimination is expressed as physical violence.

Discriminatory behaviour which targets children is referred to as bullying and, increasingly, this term is also used by adults in the workplace. Bullying is a common form of discrimination with 51% of primary school children and 28% of secondary school children reporting some experience of being bullied (DfES 2003). Bullying refers to deliberately hurtful actions, encompassing a broad spectrum of behaviours. In the case of children, name-calling is the most common type of bullying but other behaviours include teasing, rumour-spreading, theft of possessions or money, abusive text messages or emails, coercion, being excluded or ignored in play, class, sports and other activities or physical threats and abuse (Childline 2004) (see Box 1.13).

Box 1.13 Bullying and children

[Adapted from Department for Education and Skills (2003) and Childline (2004)]

Lifestyle, health behaviours and locus of control

In relation to health, lifestyle means health-related behaviours over which a person has some choice. These include:

Becker (1974) described adaptive health behaviour as being either preventative health behaviour or sick role behaviour. Examples of preventative health behaviours include exercising, not smoking and eating a healthy diet; sick role behaviours include seeking medical help, using services and complying with treatment (p. 33).

The term ‘internal locus of control’ is used to describe the beliefs held by some people that they have the power to make health-related choices, and to influence and control their health behaviour. In short, the individual feels and believes that they are ultimately responsible for their own health. Other people demonstrate an external locus of control where they see outside factors controlling their health and health behaviour, with the tendency to blame luck, fate, God, the climate or the environment. You may hear people say things like ‘If the bullet’s got your name on it …’ or ‘If you’ve got to go, you’ve got to go’. These are examples of fatalism and evident in some of the quotes in Box 1.10 (p. 10).

It is arguable whether everyone is equally free to make meaningful health-related choices. Some people are severely constrained by issues such as income, education, knowledge and peer group pressure. For example, on a very low income it is hard to afford a healthy wholemeal loaf rather than the cheaper, and less healthy, white alternative.

Factors influencing health

Factors that influence or determine health are called health determinants. The same factors that determine health also determine ill-health, and each determinant may have either positive or negative effects on health, e.g. housing. Positive health effects related to housing as a health determinant include warmth, space, comfort, well-being and psychological security. Negative aspects of housing as a health determinant are well documented and include overcrowding, noise and safety concerns leading to stress and depression, and dampness and mould resulting in physical illness, e.g. asthma.

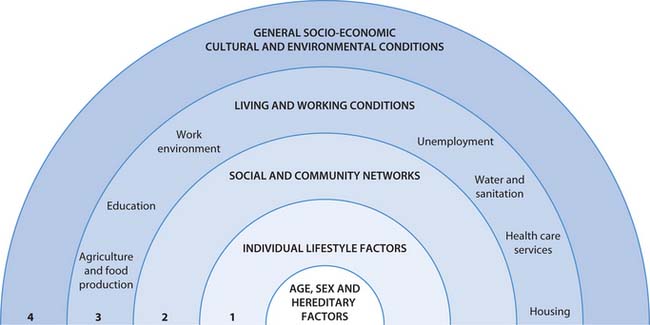

Determinants are many, varied yet interrelated and are described by Dahlgren and Whitehead (1991) as being on five levels. The multifactorial view shown in Figure 1.3 illustrates health determinants as layers surrounding a core and allows differentiation between individual and sociopolitical factors. The core factors – gender, ethnicity, age and heredity – are inherited characteristics and largely fixed, while the surrounding layers of influence may be open to some modification. The next layer is individual lifestyle where personal behaviours may not be rationally or voluntarily chosen, but are heavily influenced by family, friends and peer group, and by social and community networks. Wider influences on health include:

It is important to note that these wider determinants are not open to action by individuals but need collective action at the level of government. For example, although individuals can play their part in environmental issues in a small way – by choosing environmentally friendly cleaning products and adopting recycling behaviours – it requires policy, legislation and action at national and international levels to achieve positive changes in some health determinants, e.g. water and air quality.

The outermost layer contains the socioeconomic, cultural and environmental conditions prevalent in society including interest rates, unemployment rates and political stability. Access to health and social services is a major determinant of health and one attempt to address this is the Children’s National Service Framework (DH 2004). This is a 10-year programme intended to promote fair, high-quality, integrated health and social care from pregnancy to adulthood. There are three parts: Part 1 provides core standards for all children and young people (Box 1.14); Part 2 contains standards relating to those with illness, complex needs or mental health and well-being needs and those in hospital; Part 3 covers maternity services.

Box 1.14 Children’s National Service Framework (DH 2004) Part 1: Five core standards

Standard 1. Promoting health and well-being, identifying needs and interventions

The health and well-being of all children and young people is promoted and delivered through a coordinated programme of action, including prevention and early intervention wherever possible, to ensure long-term gain, led by the NHS in partnership with local authorities.

Standard 2. Supporting parents

Parents or carers are enabled to receive the information, services and support that will help them to care for their children and equip them with the skills they need to ensure that their children have optimum life chances and are healthy and safe.

Standard 3. Child, young person and family-centred services

Children and young people and families should receive high-quality services which are coordinated around their individual and family needs and take account of their views.

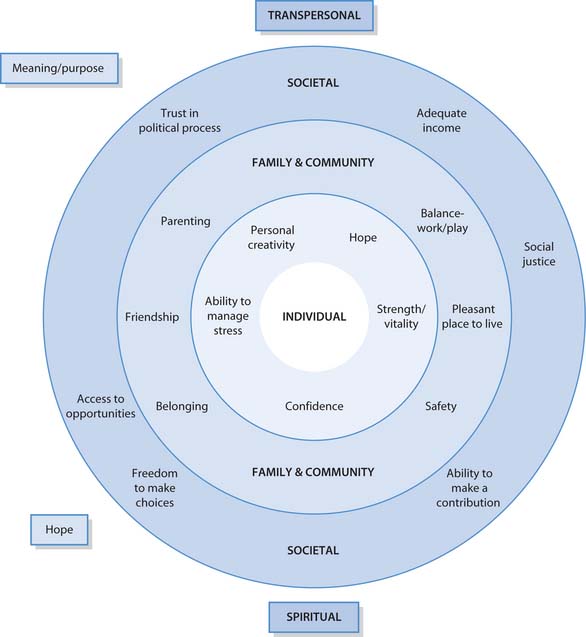

Determinants of mental health and well-being

Determinants of mental health and well-being are shown in Figure 1.4. Factors influencing mental health are grouped into four spheres:

Fig. 1.4 The confidence spiral: determinants/components of mental health and well-being

(reproduced with permission from Kennedy 2002)

Each sphere relates to dimensions of self-esteem which together influence mental health and well-being (Box 1.15).

Poverty as the key determinant of health

The most important health determinant is poverty but there is no clear consensus on how it is best defined or measured. Poverty can be defined as absolute or relative.

Box 1.16 UK groups most susceptible to poverty

[Adapted from Gordon D 2000 Poverty and social exclusion in Britain. Joseph Rowntree Foundation, York]

A satisfactory standard of living?

The European Anti-Poverty Network (EAPN 2003) urge that people’s own perceptions of poverty are acknowledged. However, the most commonly used official definition of poverty is living in a household with an income under 60% of the average for the country in which they live. Sometimes, this definition of poverty is further refined by deducting housing costs. This relative measure changes over time and in 2000–2001, 12.9 million people in the UK were living below this threshold (after deducting housing costs), 4 million of whom were children (JRF 2003). Box 1.18 shows the disproportionate effect of poverty on children.

Box 1.18  EVIDENCE-BASED PRACTICE

EVIDENCE-BASED PRACTICE

[Resource: Office for National Statistics 2004 The health of children and young people. Online. Available: www.statistics.gov.uk/children]

Effects of poverty

Poverty and disadvantage in childhood are key determinants of future mental health for children and young people. A tendency toward adult depression and also physical problems is strongly associated with social deprivation.

Relative poverty and participation in society

Relative poverty involves more than merely income; it also includes the idea that someone with a low income is unlikely to be able to participate in mainstream society. The European Anti-Poverty Network (EAPN 2003) describe the effects of relative poverty as being unable to or precluded from meeting one or more needs without outside help. These needs relate to aspects of life which enable self-determination, i.e. assuming one’s responsibilities and exercising one’s rights, or fundamental services such as education, housing and health.

Components of poverty

Poverty is complex and multidimensional, linking to fundamental issues including housing, healthcare and also to factors such as social exclusion. A combination of low pay, inadequate benefits or unemployment can lead to poverty. Low income gives rise to separate components of poverty including poverty of food, fuel, housing, transport, access to recreation/social facilities and, over time, leads to relative powerlessness. Ongoing poverty can negatively influence an individual’s physical and psychological health, with associated behavioural changes including increased use of alcohol or nicotine, sometimes called ‘drugs of comfort’. Box 1.18 highlights the links between childhood poverty and mental health.

Social class and health inequalities

Poverty has been linked to health inequalities for many years. Chadwick’s 1842 General Report on the Sanitary Conditions of the Labouring Population of Great Britain showed that richer people had a life expectancy more than double that of the poorest in society. Although life expectancy has improved steadily since then, there has not been an even improvement across social classes; inequalities still remain and may be growing.

Social class was previously categorized according to the Registrar General’s Classification of Social Class which was largely unchanged between 1921 and 2000 (see Box 1.19). People were allocated to one of five classes on the basis of the occupation of the head of the household. Although suited to men of working age, criticism of this classification centred on the exclusion of people lacking occupation, e.g. students, retired or unemployed people. Women were not included in their own right, their class being derived from that of their husband or father. Publications before 2001 use this classification.

For the 2001 census, classification of social class was revised and now the National Statistics Socioeconomic Classification (NS-SEC) is used. Eight categories were introduced to take account of changes in the labour market and the role of women. It included categories for the self-employed and those who have never worked or who are long-term unemployed. More information is available from the Office for National Statistics website.

Research into health inequalities

In 1977, the Labour government appointed Sir Douglas Black to chair a working group to review the information on health inequalities and then identify policy and research that should follow. In 1980, by the time the Black Report was due to be published, there had been an election and a change of government from Labour to Conservative. At first, the Black Report was circulated to academics in a very low-key way. It clearly showed that during the first 35 years of the NHS there had been an improvement in health across all social classes. However, there was still a strong relationship between social class and life expectancy, infant mortality and inequalities in the use of health services (Townsend et al 1992).

The Black Committee recommended a comprehensive anti-poverty programme with detailed and costed targets. The two main elements were:

The Black Report advocated that the key approach to tackling health inequalities was preventative work in childhood and in particular the ‘first years of life’. This has been borne out by subsequent research and remains the main emphasis in current health promotion targets. The Black Report’s recommendations were not implemented but, nevertheless, stimulated extensive research and raised the issue of inequalities around the world.

Some 20 years after the Black Report, the Acheson Report was commissioned by the newly elected Labour government in 1997 to review inequalities in health in England. It was published in 1998 and the main findings were that poor neighbourhoods are characterized by poor health. Also noted was that health inequalities still affect society and that they are cumulative from before birth to old age and that poverty has a disproportionate effect on children. The incidence of premature death was noted to be highest amongst the poor, directly linked to inequalities in income. The Acheson Report made recommendations in three main areas:

Box 1.20 gives an overview of the Acheson Report recommendations.

Box 1.20 Summary of the Acheson report recommendations

Acheson (1998) made 39 recommendations that were wide-ranging and included the following:

The Acheson Report stated that individual lifestyle and personal choice were not responsible for the ‘health gap’, arguing instead that income levels, changes in society and constraints prevent individuals from choice. For example, changes in transport and shopping contributed to the creation of ‘food deserts’ – areas of social housing with no shops or services, or only one small and expensive corner shop. This makes the purchase of fresh food at reasonable prices almost impossible for some families.

Unlike the Black Report which largely led to further research, the Acheson Report prompted actual policy change and engendered a climate focusing on health inequalities. Undertaking the activities in Box 1.21 will help you compare the findings of the Black Report and the Acheson Report.

Changing trends in health and illness

Health and illness issues change over time. During the last century, there was a shift in the pattern of disease from infectious diseases prevalent in the 19th and early 20th centuries to chronic physical conditions and mental health issues for the 21st century (see Box 1.5, p. 6). Diabetes is one example of a chronic physical disease causing premature death and disability. In the UK, it affects 1.3 million of the population and is increasing so rapidly that by 2010 it is estimated that 3 million people will be affected (BMA 2004). Diabetes rates in children are increasing and are linked to obesity. Suicide is increasing in children and young people. The UK also has some of the worst death rates in the world for coronary heart disease (CHD), strokes (British Heart Foundation 2003), cancer and respiratory diseases. These chronic diseases are strongly linked to lifestyle factors such as cigarette smoking, poor diet, physical inactivity and excessive alcohol consumption. Strong links exist between social class and the prevalence of these risk factors, which predominate in the poorest sections of society.

Other health trends related to lifestyle include sexual health and sexually transmitted infections (STIs). The sexual health of young people in the UK is poor and linked to unsafe sexual behaviours such as unprotected sex, which has contributed to high rates of STIs and unwanted pregnancies (Box 1.22).

Box 1.22 UK trends in sexual health and STIs

[Resource: Office for National Statistics 2004 Sexual health: chlamydia rates continue to rise. Online. Available: www.statistics.gov.uk 14 July 2006]

Apart from the increase in chronic illness and lifestyle-related diseases, another important issue is the development of new communicable diseases such as Ebola virus, human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) and AIDS, variant Creutzfeldt–Jakob disease (vCJD), severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) and bird flu. Longstanding infectious conditions previously thought to be curable are now re-emerging and are resistant to conventional treatments, e.g. tuberculosis (TB) and methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA).

Changing issues in health and illness have focused interest in health promotion and increased government funding of initiatives. The rationale is based on the large preventable component of many illnesses, e.g. smoking and lung cancer. There is a huge potential for health gains if morbidity and mortality are reduced, e.g. publicizing the effects of passive smoking on children’s health (Box 1.23).

Box 1.23 The effects of passive smoking on children’s health

[Adapted from NHS Health Scotland/ASH Scotland 2003 Reducing smoking and tobacco-related harm – a key to transforming Scotland’s health. NHS Health Scotland/ASH Scotland, Edinburgh]

Exposure to smoking during infancy and childhood increases the risk of the following and accounts for:

In addition, exposed children may also experience reduced lung function and impaired physical growth and academic attainment compared to children of non-smoking mothers.

The ‘greying’ of the population refers to a growing elderly population with an associated shift from acute to chronic illness. Older adults often have several, concurrent illnesses, known as ‘multiple pathology’. This situ-ation has been described as living longer, but not healthier. Chronic illness and multiple illnesses mean a changing emphasis on ‘care’ rather than ‘cure’.

The health needs of people with a learning disability are also changing because of increasing life expectancy and the increasing trend for more people with very complex health needs (NHS Health Scotland 2004).

The huge and growing financial cost of inpatient care, compared to health promotion funding, makes prevention of ill-health and health improvement an attractive strategy for governments. The key changes driving health and social care until 2010 are varied and are summarized in Box 1.24. They provide the current context for health promotion, which is explored below.

Health promotion

Health promotion encompasses all the activities below:

These different activities have a common aim in that they are all positive actions to improve health which, in summary, is what health promotion is all about. It is of note that only some of the activities above relate to physical health and it is important to recognize that health promotion encompasses all dimensions of health (p. 4). Contemporary health promotion often focuses on social and economic issues such as poverty and inequalities in access to healthcare and services.

The focus of health promotion activity could be the whole population but often activities are targeted to meet particular needs, focusing on one or more of the following:

Exploring health promotion initiatives

Health promotion is a useful summary phrase that covers a broad range of activities aimed at improving positive health and preventing ill-health. The most well-known definition is that of the WHO (1984) who define health promotion as ‘the process of enabling people to increase control over, and to improve, their health’.

The National Service Framework for Mental Health (DH 1999b) defines mental health promotion as any action to enhance the mental health and well-being of individuals, families, organizations and communities (Box 1.26). Standard 1 aims to ensure that health and social services working with individuals and communities reduce discrimination and promote social inclusion. In the policy document Making it Happen: A Guide to Delivering Mental Health Promotion (DH 2001a) there is a focus on preventing mental health problems by tackling issues related to wider health determinants which contribute to mental distress, e.g. bullying at school or in the workplace, reducing fear of crime and improving access to environmental or recreational services.

[Adapted from NeLH/Mentality 2002 What is mental health promotion? Online. Available: www.nelh.nhs.uk 14 July 2006]

Mental health promotion

Mental health promotion operates at three levels within the population:

Emergence of health promotion

Health promotion grew from the WHO Health for All (HFA) movement, the original title being HFA by the Year 2000 (WHO 1977). The Declaration of Alma-Ata (WHO 1978) was the birth of the HFA movement and its values underpin contemporary health promotion, with its aims and principles cascading from international level to inform national legislation. The Alma-Ata declaration states that health for all:

The centrality of primary care (or primary healthcare) to health promotion was first acknowledged here and it remains a key feature of all HFA declarations. Primary care is the first tier of health provision, provided by generalists in the local community ‘as close as possible to where people live and work’ (WHO 1978). Members of the primary healthcare team include general practitioners (GPs), practice nurses, health visitors, dentists, opticians and pharmacists. Other key aspects of the Alma-Ata declaration are summarized in Box 1.27.

Box 1.27 The Declaration of Alma-Ata

[Based on WHO 1978]

This declaration was made in the context of:

It expressed the need for urgent action by all governments, health and development workers and the world community to protect and promote the health of all of the people of the world.

The Ottawa Charter (WHO 1986) is arguably the most important health promotion document, providing the underpinning philosophy and setting the scene for all later developments. It described prerequisites of health as peace, education, shelter, food, income, social justice, a stable economy and sustainable resources. Five major types of health action were to:

The Ottawa Charter also highlighted a future commitment to health promotion with emphasis on developing health-promoting policies and environments and working with communities, not just focusing on individual lifestyle behaviours.

Principles of health promotion

The WHO used the HFA principles to devise the principles of health promotion (WHO 1984), the key principles of which are shown in Box 1.28.

Box 1.28 Principles of health promotion

[From WHO 1984]

Health promotion programmes, policies and other organized activities should be planned and implemented so that health promotion can be:

Health promotion and public health

It may be a source of confusion for students, and indeed health professionals, that there are two similar sounding phrases describing similar types of work – health promotion and public health. Health promotion means different things to different people and there are difficulties in distinguishing between this and public health. The Acheson Report (Acheson 1998) described public health as the science and art of preventing disease, prolonging life and promoting health through the organized efforts of society.

When comparing health promotion and public health, there are three main views expressed:

Box 1.29 Health promotion and public health

1. Health promotion and public health are different

Health promotion can be seen as deriving from a more social model of health with a focus on healthy public policy, addressing determinants such as inequalities, using community approaches and advocacy. Public health can be described as an elaboration of the medical model, traditionally involving a focus on communicable disease, environmental health, screening and immunization.

2. Health promotion and public health are the same

Increasingly the two terms are used synonymously in the literature. Many universities have changed their postgraduate programme titles from Health Promotion to Public Health and in primary care the term public health is more commonly used than health promotion. Other phrases including health improvement and health gain also appear frequently in modern health policies.

3. Health promotion overlaps with, or is part of, a broader concept called public health

This may be the most common prevailing view. It is seen as unhelpful to describe health promotion as a separate entity and it should be seen as an integral part of public health. The Acheson Report (1998) clearly defines health promotion as part of the broader concept of public health. Health promotion has been described as the implementation arm of public health. The two entities can also be seen as having overlapping spheres of activity such as health education, strategic planning and legislation. Sometimes the phrase ‘new public health’ is used to include health promotion.

Box 1.30 shows the current focus in UK public health practice.

Box 1.30 Current focus in public health practice

[Resource: Skills for Health 2004 Public health practice national competence framework. Online. Available: www.skillsforhealth.org.uk]

National health promotion organizations

Each UK country has its own agency or authority for health promotion. Students should explore the relevant links to their own country (see ‘Useful websites’, p. 35). Covering the whole of the UK, the Health Development Agency emerged in 2000 from the Health Education Authority (HEA), which it replaced.

England no longer has a national health education body and its core functions are undertaken by the Department of Health whose website covers specific topics including alcohol, children and families, drugs, immunization and sexual health.

The Health Promotion Agency for Northern Ireland supports those working in the areas of health promotion and public health, as well as members of the public.

Health Promotion Wales arises from the Welsh National Assembly. Their website has links to the Chief Medical Officer website and supports the promotion of health and well-being in Wales. The National Public Health Service for Wales (NPHS) coordinates the activities of the public health resources of all health authorities in Wales, including laboratory services and communicable disease surveillance.

Scotland’s agency is NHS Health Scotland which provides a national focus for collaborative work to improve health and reduce inequalities.

Values in current health promotion practice

The values that nurses and health promoters need for effective practice that underpins health promotion skills in the 21st century (Health Education Board for Scotland 2000) are:

Settings and skills for health promotion

Health promotion covers a wide range of activities which take place in many settings. NHS settings include hospitals and primary care. It also takes place in communities, voluntary organizations, workplaces, schools, in self-help groups and through the media. The skills used in health promotion also vary depending on the:

Health promotion skills are very similar to those of modern nurses and include needs assessment, planning and research, evaluation, communication, a counselling approach, management, networking, teaching, marketing, influencing policy and practice change, writing and publication.

Approaches to health promotion

Bottom-up and top-down approaches are the two main views of health promotion. They represent issues of power, control and relationships differently and this underpins their use in health promotion settings.

‘Bottom-up’ refers to the generation of issues, concerns and expressed needs from clients themselves rather than the experts being in charge. In this approach, clients are encouraged to be participative, taking an active part, or even the lead role, in identifying what they need in terms of information or assistance.

‘Top-down’ is the opposite approach and describes situations where the nurse or health promoter takes the lead and identifies concerns for, or on behalf of, clients. This approach is also described as expert led. Here, there is less client participation and less equality in the relationship. Sometimes, there is no contact with the client at all as in the case of TV health campaigns. Health advertisements try to market health in the same way as other products and often use celebrity endorsement. Health promotion through the media is also top-down as it has been planned and designed by experts and is one-way and impersonal. It is increasingly common for health and illness-related themes to be addressed through TV dramas and soap operas.

There are five ways of thinking about or viewing health promotion: medical, behavioural change, educational, client-centred and societal approaches.

The medical approach

This approach to health promotion is about encouraging people to seek medical help and to comply with prescribed treatment. It employs top-down methods to ensure that patients to cooperate and comply. The aim is to reduce risk factors and prevent ill-health. Methods include preventative procedures such as immunization and screening, in addition to information-giving and persuasive advice about lifestyle changes, e.g. giving up smoking. The latter can be carried out in person, by leaflets or through the mass media, e.g. television advertisements.

The behavioural change approach

Using this approach encourages individuals to make positive health-related changes, however small, e.g. encouraging people in the workplace to increase their exercise levels by using the stairs instead of taking the lift. Other commonly targeted lifestyle behaviours include smoking, alcohol use, diet and nutrition. The aim of this approach remains the prevention of disease by reduction of associated risk factors. It remains a top-down, expert-led approach, although participation may be encouraged.

The educational approach

This approach can be undertaken with individuals but more often involves group work. Group work is considered to be essential to explore and challenge people’s attitudes, clarify misconceptions and ensure that the knowledge which people need to make informed decisions is available. Communication skills are key to this approach (see Ch. 9).

This approach may also focus on skills development as well as knowledge and attitudes. For example, within the subject of healthy eating, budgeting or cooking skills may be practised.

This approach can either use bottom-up strategies or be directive and expert-led, depending on the design of the session.

The client-centred approach

This is a wholly bottom-up strategy where clients, either individuals or groups, identify their own concerns or areas where they need more information or assistance. Clients are seen as full equals in the process and the aim of this approach is empowerment, i.e. clients are enabled to maintain or increase control over their own lives. This means that the health promoter does not take charge of the situation but acts only as a facilitator. Often this approach is carried out in community groups where, for example, a local mother and toddler group may raise concerns about safety and local road crossings.

The societal approach

This approach is large scale and often seen as political. It frequently involves a focus on broader social and environmental determinants of health. It can be bottom-up in approach, e.g. where night-duty nurses organized a petition, lobbied managers and caterers and then successfully negotiated healthier food choices at night in their hospital canteen. It can also be top-down, e.g. when central government made seat belt wearing compulsory by law or local rules enforced no-smoking areas at work.

Societal change usually requires fundamental and far-reaching political action which is beyond the scope of individuals. This is especially true when trying to reduce inequalities in health by, for example, addressing minimum wage legislation and levels of state benefits.

Models of health promotion

Models of health promotion are theoretical frameworks giving examples of health promotion activities such as preventative health services, health education, community-based work, public policies and organizational development, and economic and regulatory activities. These activities can be at international, national, regional or local levels.

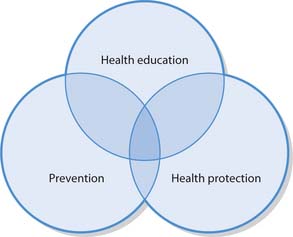

Tannahill’s model of health promotion

The Tannahill model (Fig. 1.5) defines health promotion as comprising efforts to enhance positive health and prevent ill-health, though the three overlapping spheres of:

Health education is defined in Tannahill’s model as communication activity aimed at enhancing positive health and preventing or diminishing ill-health. This can be carried out with individuals or groups, through influencing the beliefs, attitudes and behaviour of those with power and of the community at large. This is considered further in the next section.

Prevention of ill-health is described by Tannahill as activities concerned with reducing the risk of occurrence of ill-health, or an unwanted event. Different levels of prevention exist and activities from adult nursing are used as examples:

Box 1.31 shows levels of prevention applied to other nursing settings.

Levels of Prevention

The third sphere of activity in the Tannahill model is health protection which includes the public policy framework for prevention of ill-health and positive enhancement of well-being. It includes legal, fiscal and political measures, e.g. tobacco tax, or policies, laws and codes of practice, e.g. seat belt legislation. Another example of legislation for health is the policy document Valuing People: A New Strategy for Learning Disability for the 21st Century (DH 2001c) which was the first government White Paper about people with learning disabilities for 30 years and seeks to legislate to address the inequalities of access to services (see also Valuing people website in ‘Useful websites’, p. 35).

The Tannahill model is straightforward and easy to use, fitting well with nursing and other healthcare practice in primary care and NHS settings. However, it has been criticized for its medical model approach, its largely individual focus and the lack of emphasis on social determinants of health and illness. It may be less helpful in community settings and when working with disadvantaged or excluded groups. The activities in Box 1.32 will help you apply the Tannahill model of health promotion to nursing practice.

The Tones model

An empowerment model of health promotion was devised by Tones in 1993. It aims to enable people to gain control over their own health and in this way it sounds very similar to the important WHO (1986) definition of health promotion. A summary of the model (Tones & Tilford 2001) reads like a formula:

Health promotion 5 health education 3 healthy public policy.

The full model is more complex than the Tannahill model. Starting at the bottom of Figure 1.6, education is seen as critical to the process of raising awareness so that people can make informed health choices, participate in and influence health policy. This applies to both lay people and health professionals. In this model, healthy social and environmental factors are emphasized and this view fits better with bottom-up, community-based approaches as in mental health, learning disability and voluntary organizations. It may be harder to envisage this model in relation to working within a traditional NHS setting.

Health education

Although people may use the terms health promotion and health education interchangeably, they are not the same. As seen above, health education is just one part of health promotion and is only one of many methods available to the nurse or health promoter. It has been mentioned above as one of the five approaches to health promotion (see p. 24) and forms one-third of health promotion according to the Tannahill model (see Fig. 1.5). Health education was also described as one half of the summarized Tones Model (see Fig. 1.6).

There are many diverse definitions of health education, some of which are listed below. Health education (as adapted from Kiger 1995) can be described as:

Approaches to health education

Kiger (1995) described five approaches to health education: medical, educational, media/propaganda, community development and political action. These can be compared to the five approaches to health promotion explained earlier (p. 24). The approaches to health education are outlined below with examples of the likely methods used:

The activities in Box 1.33 will help you think about health education approaches used in your placement.

Health education approaches

Student activities

Health education in the NHS

A medical approach to health education is sometimes known as patient education in NHS settings. Methods such as 1:1 talks/interactions, group work and written information, alone or in combination, have been shown to increase patients’ knowledge and understanding of their symptoms, illness, surgery, drugs or other treatments. Effective communication skills are vital to people’s understanding of information provided (Ch. 9).

As long ago as 1975, Hayward’s research demonstrated that there are positive effects when patients know what to expect and are prepared by being provided with suitable information prior to clinical procedures (Box 1.34).

Box 1.34  EVIDENCE-BASED PRACTICE

EVIDENCE-BASED PRACTICE

The positive effects of health information

Hayward (1975) found that the positive effects of preoperative health information and education for patients included:

Levels of health education

As well as having different approaches, health education is also described as having different levels: primary, secondary and tertiary.

Primary health education

Primary health education involves a focus on the structure and function of the body or mind, how bodies or relationships work and how to promote and maintain them. Nurses carry out much primary health education in their everyday practice, e.g. each time information is given before informed consent is sought, lifestyle advice is offered or a procedure or treatment is explained to patients. It is usually undertaken with individuals but can be carried out in groups.

Undertaking health education with learning disability clients can be challenging because they have more complex health needs than the general population but tend not to have equity of access to health services (Gates 2003). This is also true for people from black or ethnic minority communities (NHS Health Scotland 2004). The Scottish Executive (2000) identifies seven fundamental principles, which state that people with learning disability should be:

Some people with learning disabilities learn at a slower pace and key considerations for health education are summarized in Box 1.35.

Secondary health education

This takes the form of information and advice about services to improve and maintain health, how to get the best out of healthcare and other systems, what is available and how to complain if necessary. Nurses may also carry out secondary health education in their everyday practice, but perhaps less often than primary level health education. In all settings, but especially in community nursing, nurses have to help people to:

Another empowering resource for people is the Patient Advocacy Liaison Service (PALS). This government initiative ensures that each Trust has PALS officers to provide help, information, advice and support locally and to help address any concerns or problems experienced by patients and their families.

Tertiary health education

The highest level is tertiary health education which focuses on raising awareness of the sociopolitical health determinants such as unemployment, education, pollution, water and food quality, and traffic levels. Another focus is the activities of the anti-health sector of the economy such as advertising and sponsorship by tobacco companies. This is sometimes called consciousness raising and is common in bottom-up work with community-based groups. In general, it is less common for nurses to carry out this level of health education compared to the other two. Although not often part of mainstream NHS work, tertiary health education features in the education of health professionals and may include study of poverty, inequalities and other health determinants. Box 1.36 will help you consider levels of health education in nursing practice.

UK health policy context

By 1986, the WHO’s main target for the following decades was that all citizens of the world should attain a level of health that would permit them to lead socially and economically productive lives by the year 2000. The European region of the WHO later introduced Health21, namely 21 targets for the 21st century, to achieve this goal (WHO 1998).