Chapter 7 The NMC Code of conduct and applied ethical principles

Introduction

Registered nurses (RNs) practise in a variety of care settings and provide care for individuals who have a wide range of needs. Nursing students receive a generic preparation for practice for the first 12 months of their 3-year programme. By the end of this period they are required to have achieved specified outcomes (NMC 2005a) in order to progress to their chosen Branch Programme, during which they specialize in caring for people in one of the following areas:

People who require nursing care are in a vulnerable position by virtue of the problems for which they require assistance. It is therefore important that they are afforded protection and the purpose of this chapter is to describe and discuss the ways in which protection is provided and some of the challenges that student nurses and registered practitioners may encounter in their everyday practice. This chapter should be read in conjunction with Chapter 6, which deals specifically with legal issues and nursing. The focus of this chapter is the requirements that the statutory regulatory body (NMC) has of registered nurses and the implications for nursing students. The focus is also upon the ethical and moral issues that are integral to nursing practice.

The role of the Nursing and Midwifery Council

Protection of the public

Since 1919, when the Nurses’ Registration Act was passed, public protection has been provided by a statutory body, originally named the General Nursing Council (GNC). Changes in policy and in the statutory regulatory body’s remit over time resulted in replacement of the General Nursing Council by the United Kingdom Central Council (UKCC) in 1992. The Nursing and Midwifery Council (NMC) has fulfilled this role since 2002.

Quality assurance of educational programmes

The NMC has a UK-wide remit for the quality assurance of educational programmes that lead to registration as a nurse, midwife or health visitor and all other recordable NMC qualifications, e.g. specialist practitioner. There are national differences in UK health and education policy and provision, and therefore the NMC has service level agreements with relevant bodies to deliver its educational quality assurance framework. This is carried by:

Further information relating to the remit of the above, and general and specific information about the NMC, can be found at www.nmc-uk.org.

Registration of students as qualified practitioners

Protection of the public has remained a constant feature of the regulatory body and this function includes regulation of the preparation for practice of students and the criteria for their registration as qualified practitioners. Students are required, on successful completion of their pre-registration programme, to provide a self-declaration of good health and good character. This declaration must be supported by the registered nurse (whose name has been notified to the NMC) responsible for the overall direction of the students’ educational programme at the approved educational institution. This person must also verify students’ attainment of the theoretical and practical competencies required for registration (NMC 2005a, p. 10).

Register of practitioners

A central role of the NMC is maintenance of a register of practitioners and supervision of their subsequent practice. Periodic re-registration of practitioners requires evidence of the individual’s continuing fitness to practise, which includes ongoing professional development. The NMC’s requirements in relation to post-registration education and practice (PREP) are set out in The PREP Handbook (NMC 2005b).

The Nursing and Midwifery Council’s Register

In 2004 the NMC replaced a complex 15-part register with a simplified three-part register:

Post-registration education and practice

The purpose of PREP is to ensure the best possible provision of care for patients by ensuring that all registered practitioners update and develop their practice. The PREP requirements are professional standards, set by the NMC and required by law for renewal of registration. There are two separate PREP standards, one of which relates to continuing professional development (CPD), which the NMC identifies as a key component of clinical governance. Clinical governance essentially means that the quality of nursing care that people receive should be of an equally acceptable standard, in all care settings in the UK, rather than allowing for variation from one area to another. The second PREP standard relates to the minimum number of hours for which practitioners must have worked, by virtue of their registration, during the previous 5 years.

To fulfil PREP requirements practitioners identify their own learning needs and the activities by which these may best be met. They are required to document these activities and to produce this record (see Ch. 4) if required to do so by the NMC.

Fitness to practise

Allegations made against practitioners of misconduct or unfitness to practise (e.g. due to ill health or drug misuse) are investigated by the NMC and, if these are upheld, action is taken. Depending on the nature of the offence the practitioner may be reprimanded, or alternatively their name may be removed from the register, thus removing their right to practise as a nurse. If unfitness to practice due to ill health is found to be the case, then treatment may be necessary before the person can continue to practise. The NMC also provides advice for nurses in relation to standards of professional practice (NMC 2002a).

Provision of information

The NMC publishes documents, on a wide variety of aspects of professional practice. These are reviewed and updated on a regular basis, following consultation with practitioners and other interested groups.

It provides the UK public (including practitioners, employers and clients) with information about the standards that are expected of all registered nurses and midwives. The purpose of these documents is to establish the standards expected of practitioners by the statutory body that act as benchmarks against which nursing practice may be measured. The aim of this is to ensure that a satisfactory standard of care is provided and, where necessary, enhanced.

NMC expectations of nursing students

Nursing students are not professionally accountable during their preparation for practice: the individual accountable for the consequences of their actions and omissions is the registered practitioner with whom they work. This person is usually referred to as a mentor or preceptor and will have undergone preparation for this role. The expectations of nursing students are set out in An NMC Guide for Students of Nursing and Midwifery (NMC 2002b). Students are not, however, absolved from being called to account for the consequences of their actions and omissions by their university and/or the law. As the purpose of the NMC’s guidance to students is to prepare them for practice as registered practitioners, the following section will describe and discuss the Code of Professional Conduct: Standards for Conduct, Performance and Ethics (NMC 2004) with which registered nurses must comply. Examination of the Code of Professional Conduct will place in context the subsequent discussion of the NMC’s guidance to students. Implications for students in practice placements will then be discussed using practical examples to highlight relevant points. The Code of Professional Conduct is not intended to provide practitioners with specific answers to each and every situation, but to set out the overall standards with which their practice must comply.

The Code of professional conduct

While the Code of professional conduct: standards for conduct, performance and ethics (NMC 2004) applies to registered nurses and not students, it is a good idea to obtain a copy now, if you have not already done so. It is important that, by the point of registration, you have understood and internalized the elements of the Code and their relevance to your future practice. Your university should be able to provide a copy or, alternatively, copies may be obtained from the Publications Department of the NMC (see ‘Useful websites’, p. 180).

The purpose of the Code of professional conduct (NMC 2004) is to:

Registered nurses are expected to:

Registered nurses are individually accountable for their actions and omissions, independent of the advice, directions, actions or omissions of other professionals. In addition to professional accountability, registered nurses are legally accountable for their practice (see Ch. 6). The lines of accountability, and the implications of these for practitioners, will be discussed later in this chapter.

In caring for patients and clients, the NMC (2004) identifies the requirements of the practitioner (Box 7.1).

Respecting the patient or client as an individual

This involves ensuring that the patient or client is consulted in all aspects of their care and that their preferences, wherever possible, are taken into account. Care provision should be of an equally high standard for all patients irrespective of:

Any conscientious objection to providing care, e.g. an objection to providing care for a person who is to undergo termination of pregnancy, must be reported at the earliest opportunity to the appropriate person (e.g. line manager) and, until alternative arrangements are made, the nurse should continue to provide care.

Appropriate boundaries must be maintained between nurses and their patients or clients, i.e. avoidance of overlap between professional and personal relationships, and care must always focus on the needs of patients or clients (Ch. 9).

Obtaining consent before giving treatment or care

Patients and clients should be provided with the information required in order to give what is termed ‘informed consent’ (Chs 6, 24). If the capacity of the patient or client to understand, retain and act upon information is questionable, then alternative arrangements will need to be made (see Ch. 6). For example, an individual may be granted power of attorney to make decisions on behalf of a patient/client.

Protecting confidential information

Information about patients or clients must be treated as confidential and used only for the purposes for which it has been provided, i.e. provision of healthcare. Patients and clients may assume that information about them will be shared among relevant members of the healthcare team, but disclosure of information outwith the care team, including provision of information to relatives or friends of the patient or client, should only be carried out with the patient or client’s consent (see p. 165).

Cooperating with others in the team

The team includes the patient or client and their family and/or friends, as well as informal carers and professional providers of health and social care. It may also include workers in the independent and voluntary sectors. Nurses are expected to work along with these people in provision of care, including maintenance of healthcare records and communication of relevant information to other team members. Registered nurses, even while working within a team, remain individually accountable for their own actions.

Maintaining professional knowledge and competence

This is closely linked with the earlier section in this chapter on post-registration education and practice. In addition to maintaining knowledge and competence, nurses must recognize their limitations and only undertake practice in which they are competent.

Being trustworthy

This involves behaving in a way that upholds the reputation of the nursing profession. It is important to realize that this relates not only to behaviour while at work, but at all times, and includes behaviour that is not directly related to professional practice.

The NMC also emphasizes that registration must not be used to promote commercial products or services, e.g. a particular type of wound dressing or drug. Any potential conflict of interest between a nurse’s ability to provide impartial care and a financial interest must be brought, by the nurse, to the attention of their employer and/or the NMC to protect patient care.

Acting to identify and minimize risk to patients and clients

If nurses consider that the environment for patient or client care is unsafe then they must report this to a senior person, both verbally and in writing. Examples of an unsafe environment include not only the physical surroundings, but also staffing levels and competence of practitioners. It includes any concern that a nurse has about the fitness to practise, for whatever reason, of another member of the care team.

Even outwith work, nurses have a professional obligation to provide care in an emergency situation. The standard of care provided is that which could reasonably be expected of a nurse with equivalent experience, placed in similar circumstances.

While the readers of this book are nursing students, not registered practitioners, it is necessary that they are aware of the standards with which they will be expected to comply on completion of their educational programme.

While the requirements of the Code of Professional Conduct (NMC 2004) may, at first sight, appear to be clear, unambiguous and uncontestable, it will be seen that challenges for practitioners in practice may arise in relation to them all.

Implications of the Code of professional conduct for nursing students

As nursing is a practice-based occupation, placements that provide students with first-hand experience of nursing care are a vital component in preparation for becoming registered practitioners. During placements students should work only under the direct supervision of a registered nurse (RN). This does not mean that the RN requires to be physically present at all times, but it does entail that the RN should be aware, at all times, of the student’s location and activities. The RN is accountable for the consequences of the actions and omissions of the student and is therefore required to be conversant with the students’ programme and their stage within it.

One element of the Code of Professional Conduct reminds RNs that they ‘have a duty to facilitate students of nursing and others to develop their competence’ (NMC 2004, clause 6.4). RNs are therefore under an obligation to teach and supervise students, while students have a responsibility to develop the stipulated proficiencies prior to being registered as a nurse (NMC 2005a, Table 2.3). This includes ensuring that the care that students provide does not exceed their current level of understanding and competence. If students consider that they are requested or required to carry out activities for which they are unprepared, then this should be identified, at the time, to their mentor or to the RN who is in charge of the placement. It is also advisable for students to notify a member of the teaching staff from their educational institution. The fact that students are not professionally accountable to the NMC does not mean that they are unaccountable to their higher education institution (whose recommendation to the NMC is a prerequisite for their registration) or to the law.

Patients and clients are at the centre of healthcare and their wishes must be respected at all times. Students should identify their status, if the client does not already know this, in order that the latter may indicate acceptance or refusal of their care provision. (Indeed, it is a criminal offence for individuals to represent themselves falsely and knowingly as registered nurses.) If a patient or client refuses care from students, or asks them to leave while care is being carried out, then students must comply with this. While the majority of patients and clients accept that students’ participation in nursing care is an integral component of their preparation for practice as an RN, respect for the rights of the patient/client overrides students’ rights to knowledge and experience (NMC 2002b, p. 4). Similarly, if a patient, client or their friends or family voice disquiet at any aspect of care, students should refer this immediately to their mentor or the RN in charge of the placement at the time. Students should also be familiar with the local policy for documenting concerns or complaints, as there may be some variation in the specific procedure within different areas of practice.

Confidentiality

Patients and clients provide information that is frequently of ‘a sensitive nature’, as defined by the Data Protection Act (HM Government 1998a). Patients and clients therefore need to be assured that information provided is not divulged, other than for the purpose for which it was supplied, i.e. their healthcare. If, for example, students describe the care provision for a specific patient/client within a written assignment, then they must ensure that patient/client and placement details are anonymized, e.g. by using a pseudonym. Students must also avoid talking about patients/clients when their conversation may be overheard and, if discussing patient/client care in, for example, a reflective session in their educational establishment, then they need to take the same measures to protect confidentiality.

Access to patient and client records

Access to patient/client records should be in relation only to the need to implement effective care and local policies and practices on handling and storage of records must be adhered to (Ch. 6). Documentation by students of care that they have provided should be carried out under supervision of an RN and the RN should countersign the student’s signature. The NMC has advice within the Code of professional conduct (NMC 2004) specific to confidentiality and a document providing guidelines for records and record keeping (NMC 2005c), with which students should familiarize themselves.

Confidentiality in practice

Maintaining confidentiality of information provided by patients/clients is not always clear-cut, as the following situation illustrates.

The situation outlined in Box 7.2 illustrates a number of points, one of which is the importance of ensuring that patients and clients are made aware of a student’s status. Students are frequently involved in direct, and often intimate, care provision and thus may be viewed by patients/clients as approachable and someone in whom they may confide information that they might be more hesitant to reveal to qualified staff. As can be seen in the situation described in Box 7.2, this degree of intimacy may place students in a difficult position. On the one hand, there is a requirement to maintain confidentiality and to accede to individual wishes (NMC 2004); on the other hand, there is the need to ensure that qualified staff have access to all information that is relevant to a patient’s/client’s care.

Maintaining confidentiality?

You are undertaking a placement in a surgical ward. It is suspected by the qualified staff that Katie, a 37-year-old patient who has been admitted to the ward via the Accident and Emergency Unit, has sustained injuries that are non-accidental and the nature of which preclude their having been self-inflicted. While you are assisting Katie to carry out personal hygiene, she tells you that her partner was the perpetrator. She emphasizes that this information should not be passed on to anyone else.

It is useful to refer at this point to the Code of professional conduct, which addresses issues related to confidentiality (NMC 2004, clause 5). This points out that, as it is impractical to obtain consent on each occasion that information sharing is required, it is important that patients/clients are made aware, when their care commences, that some information may need to be shared with other members of the care team. It is not clear, in the scenario, whether Katie was given this information in advance of her contact with the student. In situations in which information may need to be disclosed outwith the immediate care team, the person’s consent should be obtained. If consent is withheld, disclosure is only justifiable when:

For the student, the answer is that they should explain to Katie that the information provided cannot be kept confidential. The student is not in a position in which non-disclosure of the information would be justifiable, as it is the responsibility of students to ensure that information relevant to patients’/clients’ current and future care is passed to their mentor or to the RN in charge of the placement at the time. However, this situation also raises the issue that, when an assurance of confidentiality cannot be provided to a patient or client, they should be informed of this and of the rationale for the decision.

For the RN to whom this information is divulged, there is an obligation to discuss its implications with other members of the care team, as it may impact upon the patient’s/client’s current and future care requirements. It is also important to document the information in their notes (NMC 2005c). In relation to divulgence of the information beyond the immediate care team who are responsible for the patient’s/client’s welfare, the position is less clear. It might be argued that information should be passed to the police, for example, in order to investigate the allegations made and to provide protection for the patient/client from further harm. However, Katie is an adult and there is no indication within the scenario that she lacks the mental capacity (Ch. 6) to make her own decisions.

Qualified staff might discuss the situation and the potential consequences for Katie of reporting, or not reporting, the matter to the police, but if she refuses to make a statement then there is little that the staff can do. Respecting Katie’s wishes may cause disquiet among staff as to the possibility that future harm may result, but this may not be a justification for interference. Indeed, it is difficult to predict the outcomes of actions and omissions and reporting of the incident could, at least in Katie’s view, have the potential to create further problems.

It would probably be the case that the staff would discuss with Katie the possibility that she could, at a future date, bring a charge against her partner and that documentation of her current condition and care would be available should she wish to call upon it. Staff might also provide Katie with information about sources of support, both formal and informal (e.g. family, workplace colleagues, Samaritans, Women’s refuge, police), which she could draw on if she chose to do so.

Katie’s situation presents a dilemma to staff, i.e. it is a problem that does not have a clear-cut solution. Whichever action, or inaction, the staff consider most appropriate is likely to cause them disquiet at the time and on subsequent reflection.

If a child is involved there is no room for debate. If Katie had divulged that her partner was abusing her 12-year-old child, then the situation would be quite different, as is made clear by the Code of professional conduct (NMC 2004, clause 5.4) and the law (see Ch. 6). In such circumstances it would be explained to the woman that, as the welfare of a child was in question, the information would have to be reported to Social Services in order that they could investigate the situation.

Ethical principles

Having discussed the situation in Box 7.2 in general terms, it is now useful to examine it further, in order to identify the principles underpinning the decisions that might be made. The ethical principles that will be identified are sometimes referred to as being prima facie. The phrase means ‘at first sight’, i.e. each principle should be respected ‘at first sight’ but, in the light of the situation, another principle might need to take precedence. For example, autonomy (the right to make one’s own decisions) appears, at first sight, to be one that should be respected, but there may be circumstances in which another principle would override it. This will be identified in the discussion that follows.

Autonomy and justice

Within Western societies, great importance is placed on autonomy. The word autonomy literally means to be ‘self-governing’, but clearly within society there are limits upon the degree to which one may exercise autonomy. For example, it is usually accepted that the right of one individual to exercise autonomy should not interfere with the rights of other individuals to exercise their autonomy. The right of one person to hold regular noisy parties would interfere with the rights of others to have a peaceful night’s sleep. The right of one person to drive recklessly interferes with the rights of other individuals to use the roads in safety. In situations such as reckless driving and breach of the peace, society usually places legal penalties upon those who infringe or threaten the rights of others. So, autonomy may be exercised, provided that harm is not caused to others in the process.

In Katie’s situation, exercise of autonomy in refusing to report the injuries to the police does not directly appear to interfere with the rights of others. (Indeed, were the staff to ignore the patient’s wishes and report the matter to the police, a prosecution would be unlikely, in the absence of the victim’s cooperation.) Were the welfare of a child involved, the patient’s ‘autonomy’ could, and should, be overruled, as the patient is not able to make a decision that would place a child at risk of continuing abuse.

Non-maleficence and beneficence

The reason that staff who might wish to intervene on the woman’s behalf would probably put forward would be the desire to prevent harm to the patient (an idea known as non-maleficence) and to act in the patient’s best interest (known as beneficence). There is also the problem that consequences of actions or omissions are difficult to predict: anticipated harms or benefits may not materialize in reality. Identification of ‘best interests’ can also be problematic, as the attitudes, values and beliefs that individuals bring to any situation will influence the decisions that they make (Ch. 1). Actions that nursing staff may consider to be in patients’ best interests are not necessarily ones with which patients would agree. A respect for patients, the importance of which is emphasized by the Code of professional conduct (NMC 2004), indicates that staff should comply with patients’ wishes when these are clearly expressed and when the patient has the legal capacity to make decisions (Ch. 6).

Client autonomy in healthcare is not always straightforward, as the right to autonomy is usually based on a person having insight into the consequences of their actions or omissions. (One would not consider a small child to be autonomous, for example, in their desire to run across a busy road to reach the park. Interference would be considered not only justifiable, but mandatory.) In order to be autonomous therefore, patients need to be provided with the information upon which to base their decisions and be able to understand, retain and act upon it. In Katie’s situation if the available options were discussed with her along with the possible outcomes of each, this would facilitate an autonomous decision.

In summary, the four principles that were used in the discussion above are:

While Katie’s situation created a problem that is unlikely to be encountered on a daily basis, there are many problems that nurses can encounter on a regular, if not everyday, basis (Box 7.3). While this is not a ‘life and death’ issue, decisions made by staff will have an impact on patients’ quality of life.

Too many patients and too few staff

In a busy placement there are several patients who need assistance to eat and drink, but only a few staff on duty. Some patients will therefore have to wait longer than others for their meal that may be cold by the time they receive it.

The ethical and moral dimensions of nursing practice

The nature of healthcare provision is such that decisions made and the treatment and care provided, or withheld, may alter the duration and quality of the lives of the individuals who experience it. The relationship of nursing to health and well-being (Ch. 1) provides it with a moral dimension such that it is usually impossible to identify some elements of its practice as morally significant and others as morally neutral. It might be thought, for example, that measuring a patient’s blood pressure is a psychomotor skill that is morally neutral, but the nurse’s ability to measure and record the blood pressure accurately has the potential to affect the patient’s health and well-being and this is morally significant. All decisions and actions taken (or omitted) in relation to client care are closely connected to their beneficial, or harmful, effects upon the client. While some aspects of nursing are in themselves technical, competence or lack of it has an effect upon the client’s welfare. If nursing practice is accepted as having a highly significant moral dimension, then evaluation of nursing care quality involves moral reasoning processes in order to arrive at moral judgements. In Box 7.3 where staff shortages prevented all patients being provided with the help needed to eat and drink simultaneously, the decisions made about whom to assist, and when, were not only technical, but also moral in nature. It is now useful to examine the concepts of ethics and morals and their implications for nurses.

Ethics and morals

Ethics and morals are terms that are frequently used interchangeably. When differentiating between the two, the term ethics is usually taken to refer to the study of morals, whereas morality relates to people’s behaviour.

Ethics and morals are sometimes viewed as something to which we resort in time of crisis, but it is arguable that morality is not one single dimension of life within society but is essential for society to function successfully. Thompson et al (2000, p. 258) argue that ‘moral judgement, decision and action are as natural a part of living and doing as breathing. We all grow up in some sort of moral community.’ They stress that not all moral decision-making is associated with drama and crisis and that ‘most of us develop remarkable skill in making rapid moral assessment of the problems facing us in the practical situations in our lives and in taking the appropriate decisions’ (p. 256). Thompson et al (2006, p. 3) argue that moral choice is an integral, and inescapable, part of everyday life and a focus on life and death dilemmas clouds the fact that the majority of moral issues faced by nurses are encountered in daily practice.

Downie and Calman (1994, p. 12) argue that:

It is misleading to think that there are clinical discussions or professional decisions and occasionally also separate moral decisions. Rather, our argument will be that all clinical or professional decisions have a moral dimension to them, for morality, like attitudes, is all-pervasive. Moreover, since morality is all-pervasive it cannot be compartmentalized and it is therefore impossible to separate the moral decisions of someone in a professional capacity or role from the moral decisions of that same individual in a private capacity.

Downie and Calman (1994, pp. 15–16) also state that:

morality is inescapable. The point is that living together with other people requires that we acknowledge certain actions to be right or just or compassionate, and others to be wrong or unjust or inconsiderate. Without some agreement on what we ought to do, and what we must not do, there could be no social harmony and co-operation …we may not be conscious of the moral nature of our actions precisely because morality is an inescapable part of our lives.

The notion that it is impossible to demarcate clearly between the work and private life of a registered nurse is one that is made clear in the Code of Professional Conduct (NMC 2004, clause 8.5), which emphasizes that registered nurses have a professional duty to provide care, in an emergency situation, within or outwith their work setting.

Having said that ethics and morals are central to nursing practice, it is the case that problems or dilemmas can, and do, occur. A dilemma is, by definition, a situation to which there is no solution and action taken will be with the purpose of creating the least harm. More common than dilemmas are problems, to which solutions may be found, although these solutions may not be without complexity.

Ethical theories

Ethical theories are sometimes used within the UK in relation to healthcare provision and these will now be described and discussed in the light of a particular situation. In the situation outlined earlier, Katie, who had been abused, was central to the discussion illustrating the application of ethical principles. Now carry out the activities in Box 7.4 that relate to decisions that may be made in relation to allocation of healthcare resources.

Allocation of resources

It is sometimes argued that individuals whose health problems can be perceived as ‘self-inflicted’ should not have the same entitlement to treatment as others. One example is that of cigarette smokers.

The responses and reasons that people provided to the activities in Box 7.4 will vary, but it is useful to identify and discuss some of the most commonly used arguments in favour of, and against, the equal entitlement of cigarette smokers to treatment.

In your own discussion you may well have arguments that are additional to those listed in Box 7.5 although those in the box are often used to support arguments for, or against, equal access to healthcare treatment for cigarette smokers. It can be seen that the issue of whether or not cigarette smokers should enjoy equal access to treatment as non-smokers is not a clear-cut and straightforward issue.

Box 7.5 Arguments for, and against, equal entitlement of smokers to treatment

Arguments for equal entitlement of smokers to treatment

Arguments against equal entitlement of smokers to treatment

It is important, in nursing practice, to be able to identify arguments for, and against, a particular course of action and to analyse which of the arguments appear to be the most compelling and why. So, the activity in Box 7.4 was intended to be useful in relation to the process of identifying arguments for, and against, a particular viewpoint, as well as in relation to the product, in this case compiling a list of arguments. Reflection on practice (Ch. 4) also involves this type of activity. Over time, and with experience, reflection in practice enables practitioners to analyse and evaluate situations at the time that they occur, thus enabling the practitioner to be reflexive, in addition to reflective. This is a skill that will develop throughout the students’ educational programme and further development will continue following registration. Events that facilitate reflective and reflexive practice are those in which practitioners explicitly identify why a particular situation proceeded well or badly in relation to its component parts.

Practitioners also need to identify their own attitudes, beliefs and values. In the arguments for, and against, equal access to treatment for cigarette smokers, it is likely that your personal attitudes, beliefs and values, rather than a notion of ‘objective’ judgements, may have come into play initially. These may have been clearly evident in your replies, or may have been implicit in the reasons provided for the response.

Some of the arguments outlined in Box 7.5 will now be examined to identify some of the ethical theories that underpin them.

Consequentialist ethics

One argument put forward in Box 7.5 was that, when health resources are finite, they should be allocated in a manner that will create the greatest health benefit for the greatest number of people. This type of thinking is ‘consequentialist’ and one form of consequentialism, called ‘utilitarianism’, was proposed by a UK lawyer, Jeremy Bentham (1748–1832). His theory was further developed and refined by John Stuart Mill (1806–1873). Bentham used the term ‘happiness’, but this was later redefined by Mill as ‘benefit’, and, whereas Bentham’s focus was clearly upon the good of the majority, Mill also advocated tolerance for minority beliefs and lifestyles.

The utilitarian theory of deploying resources to provide the greatest benefit for the greatest number of individuals frequently underpins UK government policy, both at central and local levels (Box 7.6). It is a consequentialist theory because the focus is on the consequences of action or inaction: the methods taken to achieve the desired consequences (i.e. the greatest benefit for the greatest number of individuals) are deemed to be morally right or wrong insofar as they facilitate, or inhibit, attainment of benefits. (This type of theory is sometimes also referred to as ‘teleological’, i.e. derived from the Greek teleos, meaning ‘end’.) For example, if cigarette smokers are less likely than non-smokers to benefit from a particular treatment, and resources to provide that treatment are limited, then the treatment should be available to those who will benefit most, i.e. the non-smokers.

Strengths and limitations of a utilitarian approach

Some of the arguments in favour of a utilitarian approach are that it is the only feasible way in which to cater for the healthcare needs of a large, and fairly diverse, population. The impossibility of addressing the needs of every individual within a country means that policy makers have to adopt a ‘broad brush’ approach and aim to create the greatest benefits for the greatest number of people. Adoption of this strategy is intended to ensure that the health needs of the majority of the population are addressed.

Unpredictability of outcomes

One problem with a utilitarian approach is that it is based on the ability to identify the actions, or inactions, that will ensure beneficial outcomes. (It is important to recognize that ‘inactions’ as well as ‘actions’ have consequences, e.g. if a decision is made not to treat a patient – ‘inaction’ –then this will have consequences, as will providing treatment – ‘action’.) In reality it is often difficult to predict what the outcomes of actions and/or inactions will be. If the intended action is to provide treatment so that an individual will have many more years of a healthy life, then not only may the action itself fail to achieve this end, but also the unpredictability of life may result in an individual dying of another, possibly unrelated, cause. For example, if a non-smoker is treated in preference to a smoker, on the grounds that they are likely to achieve a greater long-term health benefit, it is possible that the non-smoker may die from another cause within a year of treatment, whereas the smoker may survive for many years. So, the unpredictability of actions, inactions and outcomes is one factor that may be used to criticize a utilitarian approach to resource allocation.

What counts as ‘benefit’?

Another concern about the implications of consequentialist theories is that they may encourage a simplified view of ‘benefits’ as equating neatly with ‘years of life’. This is a quantitative approach (see Ch. 5), in which the numbers of survivors and length of their survival are important. It may also be argued that quality of life may be of equal importance as length of life. For example, treating non-smokers who have certain forms of heart disease may provide them with many years of health, whereas treating smokers with similar problems may enable them to mobilize outdoors, as opposed to being housebound and this may improve their quality of life, even if only for a relatively short time.

Are numbers all that count?

Another limitation of consequentialist theories is that individuals who suffer from a relatively rare health problem, or one that is not considered to be a health-care priority, may be unable to access treatment if resources have been geared towards provision of treatment for the majority. For example, relatively few individuals require a liver transplant, whereas many people have heart disease or cancer, or know of someone with these problems.

Does the end result justify the means?

The fact that consequentialist theories focus on results and not the actions and inactions that are necessary to create these may be deemed unacceptable, at least in some instances. It may be considered that the actions and inactions are, in themselves, of moral importance. For example, it may be anticipated that telling a patient the truth about an unfavourable diagnosis and prognosis will create distress for that patient, for their friends and relatives and for the care team. A consequentialist might argue that, if creation of the greatest benefit for the greatest number of people will be achieved by telling a lie, then that is the morally correct thing to do. It is the end result, or consequence, that is of moral importance and not the means used to achieve it. An alternative viewpoint is that there is something about telling the truth, or telling a lie, that is morally right or wrong in itself, independent of the consequences.

Taking consequentialism to extremes might (at least in theory) entail that, in the case of a person who was in need of healthcare, but who was without friends or relatives and who wished to die, it would not only be acceptable, but desirable, for that person to die. This would free up the resources that would be used in their care for the care of others and thus maximize benefits for the greatest number of people.

Rule utilitarianism

One way to circumvent the potential problem outlined in the previous paragraph is to refine the theory. Rule utilitarianism states that, rather than deciding in individual instances what will create the greatest benefit for the greatest number, the ‘rule’ should be implementation of actions (or inactions) that it is anticipated will, if adopted by society as a whole, create the greatest benefit for the majority. It might then be argued that it would not create the greatest benefit for society as a whole if a culture were promoted in which the lives of individuals were held in low regard.

Consequentialist ethics: summary

There are many arguments in favour of, and against, a consequentialist approach to ethics, a few of which have been identified here. Overall, its charm may lie in its relative simplicity. It contains no spiritual or religious elements and relies on identification of factors that will create the largest net benefit for the greatest number of individuals. However, the relative simplicity of the theory may be a shortcoming when it encounters the complexity of individuals’ needs for care and determination of what comprises a ‘benefit’. The difficulty in predicting outcomes is also problematic, as is the idea that actions and inactions are, in themselves, neutral and are morally relevant only in respect of their results. For further reading about utilitarianism, see Thompson et al (2006) and the Further reading section at the end of this chapter.

Deontological ethics

Some of the arguments for, and against, smokers’ equal access to treatment use justifications that are not dependent upon intended consequences. One example is the idea that treatment decisions should be made on the basis of individual need and that healthcare workers have a duty to provide care regardless of an individual’s lifestyle or behaviours. This argument is evident in the code of professional conduct (NMC 2004, clauses 2.1 and 2.2) which emphasizes the importance of respecting the patient or client as an individual. This type of argument proposes that actions and/or inactions are morally acceptable or unacceptable in themselves, independent of their anticipated or actual consequences. This type of argument is termed ‘deontological’.

Deontology is derived from the Greek words deon, meaning ‘duty’ and logos, meaning ‘science’ or ‘study of’. A deontological theory specifies moral requirements and moral prohibitions. The code of professional conduct (NMC 2004) is an example of a deontological code. The code does not refer at any point to the maximization of benefits for the greatest number of patients, nor does it refer to the end result justifying the means by which it was attained. Rather, the code specifies the duties of registered nurses, including their duty of care to all patients as individuals.

Kant (1724–1804) developed deontological theory, including the concept of the categorical imperative. Basically, this involves asking oneself whether, if one’s proposed action (or inaction) were to be implemented by people universally, would it be morally acceptable? For example, if a person considered telling a lie, they should first consider whether, if this practice were universal, the result would be acceptable. It is likely that, while an individual might consider that their own action (in this instance telling a lie) in a specific situation might be acceptable, they might also realize that, if such action were adopted universally, chaos would ensue, as no individual would be able to place trust in another. If individuals decide to behave in a manner that would be acceptable if it was universally practised, then they are acting in accordance with a categorical imperative. A deontological approach to truth telling would be that telling the truth, or a lie, is of moral importance, in itself, as an action, rather than solely in terms of its consequence. The individual’s intentions are also important, e.g. that the intention of an individual in carrying out a particular action was fulfilment of a duty.

While the code of professional conduct (NMC 2004) is a secular, or non-religious, document, and while a deontologist may be agnostic or atheist, the majority of religions can be classed as deontological, i.e. a religion usually requires that its adherents behave in specific ways, which are deemed to be right or wrong in themselves, as opposed to right or wrong in relation to their beneficial or deleterious consequences.

Areas of potential conflict

One area of potential conflict may be readily identified from the fact that deontologists may have a variety of backgrounds: their commonality lies in the requirement, duty or obligation to behave in particular ways. One person’s idea of duty may vary considerably from, and indeed may be diametrically opposed to, that of another individual, if they have a different set of deontological beliefs. In relation to termination of pregnancy, for example, individuals who believe strongly in the right of women to decide whether to continue with, or terminate, a pregnancy, may express a deontological belief that healthcare workers have a duty to provide termination of pregnancy on demand. On the other hand, individuals who are strongly against termination of pregnancy may base their belief on a perceived duty to preserve human life, or potential human life, at all costs. This example shows that deontologists may hold diametrically opposed views, although they share in common the belief that individuals have certain obligations or duties, with which they must comply.

Virtue ethics

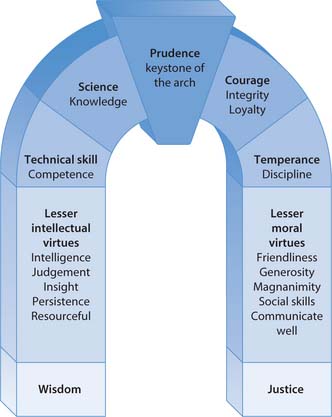

A theory of ethical behaviour, originally expounded by Aristotle in the 4th century bc and developed more recently by Macintyre (1981), concerns the role of the virtues. A virtue is a character trait that is perceived as socially valuable and a moral virtue is one which is morally valuable (Beauchamp & Childress 2001). Virtue theorists consider that morality, rather than being the domain of ivory-tower academics, is a practical skill that is exercised on a daily basis. If children are socialized into behaving in a morally acceptable manner in relation to others, then this should become habitual practice over time. Within this theory humans are perceived as social in nature, but individuals require to practise certain behaviours or virtues on a regular basis in order to maintain them. It is insufficient only to know what is right: it is necessary to put that knowledge into practice (Ch. 1). The concept of moderation in behaviour is important and individuals must take responsibility for their voluntary actions. Thompson et al (2006, p. 302) explain that Aristotle’s system of ethics requires both intellectual and moral virtues (Fig. 7.1).

Fig. 7.1 Symbolic representation of Aristotle’s view of the relationship between prudence and the intellectual and moral values

(reproduced with permission from Thompson et al 2006)

Intellectual and moral virtues

The intellectual virtues are those that relate to skill in decision-making and problem-solving, while moral virtues are character traits (or habits) that are prerequisites for an individual to be reliable, effective and efficient in action. The keystone (see Fig. 7.1) that links and binds the intellectual and moral virtues together is the quality of prudence, which may also be referred to as practical wisdom. Thompson et al (2006, p. 308–309) argue that ‘situation ethics’ is needed, as this actively acknowledges the importance of the ‘specifics’ of particular situations, rather than, as some ethical theories require, attempting to develop principles that are universal in application and that may be applied to any situation. Consequentialist and duty-based approaches to ethics are viewed as attempting to force unique events to comply with an inappropriate general framework for action. Neo (i.e. modern versions of) Aristotelianism, or virtue ethics, draws to some extent on the traditions of Christian ethics in its requirement to consider each situation as being unique, comprised as it is of individuals. Individuals are not identical to one another and they all have needs that should be addressed in an understanding, individualized and caring manner.

Concerns about virtue ethics

Concerns are also raised in relation to the idea of virtue ethics. It can be argued that some people find the idea that virtues can be cultivated in all individuals to be impossible. The qualities deemed to be virtues might also lack consensus amongst the population at large. For example, for some people, intellectual endeavour may be perceived as a virtue, while for others this is not valued. It can be argued that, even if practice of the identified virtues becomes habitual over time, situations may arise in which individuals abandon virtuous behaviour, at least temporarily. For example, in response to continuing severe staff shortages, which complaints to management have failed to rectify, a normally thoughtful and caring practitioner may find that their capacity, or motivation, to be virtuous has diminished, or is absent. For virtues to flourish, it is important to recognize that responsibility is not solely that of the individual: the environment also needs to be one in which the qualities deemed to be virtues are promoted and prevailing conditions are such that they may flourish.

Constraints on ethical behaviour

Indeed, it may be argued in relation to any ethical theory that, while some behaviours may be those for which individuals (sometimes referred to as ‘agents’) are directly responsible, the structures within which individuals operate (in both work and domestic settings) may inhibit, or facilitate, moral conduct. This interaction between an individual (the agent) and the structures within which they live and work should not be underestimated as a determinant of people’s ability to behave morally.

Ethical theories: summary

The previous section outlined three ethical theories that are of relevance to UK healthcare provision. More detailed explanation and discussion of ethical theories is provided by Thompson et al (2006) and others in the Further reading section at the end of this chapter.

Power: its use and abuse

Power has a variety of definitions, but most include the notions of command, authority, control and the ability to influence events and produce effects. The nature of healthcare is that those who seek it are usually, due to their need for assistance, in a situation in which their ability to exert power is limited. Students may not consider themselves to be powerful players within the healthcare team, but the position of patients or clients who require assistance places them in a position of vulnerability in relation to all who provide their care. The abuses of power reported by the media tend to be those that are extreme in nature, e.g. the case of Harold Shipman, an English GP, convicted in 2000 for the murder of over 200 of his patients. It is important to remember that many decisions in everyday nursing practice are not those of life and death, but of care quality, and relate to treating patients and clients as individuals who are entitled to respect. Now consider the scenario outlined in Box 7.7.

An abuse of power?

John is a student undertaking his first practice placement in a community house for adults who have learning disabilities. He had no experience of care settings before starting his university programme 4 months ago. One of the residents, Alex, who has a moderately severe learning disability and is overweight, asks John for sugar in his tea. John is about to comply when one of the care workers shouts across the dining room that Alex is ‘not allowed sugar’ as he is on a diet. Alex protests loudly and swears at the care worker, who replies that, unless Alex ‘behaves’, he will have to return to his room.

An abuse of power?

Individual reactions to the scenario in Box 7.7 will vary, but some relevant points are identified below:

In this short scenario, and with no direct knowledge of the people concerned, it is impossible to place the situation in context and to understand the individuals’ motivations for their actions. However, the fact that Alex is in a position of vulnerability as he needs care does not mean that he should be placed in a position where decisions are made on his behalf, without prior consultation and agreement. It also does not mean that he should be subjected to what might be classified as a form of emotional abuse, i.e. humiliation in front of other residents and threats of removal to his room.

On reflection then, while it may be that the care worker acted in what she perceived to be the resident’s best interest, and it is the case that beneficence is a prima facie ethical principle (i.e. a principle that, at ‘first sight’ should be respected), it may still be argued that it was unacceptable to take the action that she did, as her actions interfered with John’s autonomy, which is another prima facie ethical principle. An individual’s autonomy in relation to health issues usually overrides beneficence by others (for exceptions to this, see Ch. 6). It may also be argued that the resident’s ‘best interest’ was not served by the way that the care worker handled the situation.

What should John do in this situation? Although students are not professionally accountable to the NMC, it may be argued that, as a future registered nurse, John should have the residents’ interests as his main concern and take some action to protect these. There are several options available to John:

Of the above, while John does not perhaps have a legal or professional obligation to report the incident, it may be argued that he does have a moral obligation to do so. Alex is a vulnerable individual who has received treatment that appears to be detrimental to his emotional, although not physical, well-being. If there are valid reasons for the care worker’s response to the resident, then these should be made clear. John could perhaps approach the care worker and ask why she had spoken to Alex in the way that she did. An alternative would be for John to request clarification from his mentor or the person in charge of the placement. Formalized care policies, guidelines and procedures provide a benchmark for staff, clients and other interested parties against which the quality of care delivery may be measured. They clarify acceptable and unacceptable staff behaviours and would have been a helpful resource for John.

If John failed to receive a satisfactory explanation from staff within the unit, or from the presence of policies, guidelines or procedures, he could then contact his university in order that the incident be explored with the Link Lecturer. John could also make a written complaint about the care worker’s behaviour which would then be the subject of official investigation (Ch. 3).

Such action may be termed ‘whistleblowing’ by the media. The Public Disclosure at Work Act (HM Government 1998b) provides legal protection for employees who divulge unacceptable work practices (Ch. 6). Students are not employees of the management of placement areas and cannot therefore be subject to their disciplinary processes and procedures, but they are subject to those of their higher educational establishment. Registered nurses are provided with legal protection by the Act (HM Government 1998b) if they disclose unacceptable practice(s) although this does not prevent potential censure of that individual by colleagues for having divulged unacceptable practice(s).

John, as a student, may feel that it is difficult to raise concerns about poor, or unacceptable, practice within a placement area for fear of intimidation by staff (this concern may also be experienced by registered practitioners). The Royal College of Nursing (RCN 2000a) has issued guidance in relation to bullying and harassment at work and also a specific guide for students (RCN 2002b) to enable them to deal with these issues, should they arise.

The situation above showed that power does not reside solely in the management team in healthcare settings. People who provide direct care for patients and clients wield a considerable amount of power over their well-being and abuse of this power does not necessarily manifest as the flagrant forms of abuse that are likely to make news headlines. The example also illustrated that students who witness what they consider may be unacceptable practice may be uncertain about how to proceed in making a formal complaint. Advice should, in those instances, be sought from the sources identified in the previous section.

Vulnerable groups

The most vulnerable members of society are likely to become the victims of abuse, both in institutional and domestic settings. These include:

Some client groups are more vulnerable to abuse than others, including individuals who receive ongoing (as opposed to short-term) care, those who have a limited ability to articulate or whose reports of abuse are unlikely to be heeded, e.g. if they receive few visitors in whom they could confide, are potential victims for abuse.

The NMC provides guidelines for practitioners working with people who have mental health problems and learning disabilities (NMC 2002c) and, additionally, guidelines to provide advice on practitioner–client relationships and the prevention of abuse (NMC 2002d).

‘At-risk’ care settings

Abuse within care settings may be classified in a number of ways (Box 7.8) and is more likely to occur in certain circumstances (Wardhaugh & Wilding 1998). Care settings and management styles that may result in poor, or unacceptable, practice include the following:

[Adapted from DH 2000]

In these circumstances clients may be perceived as units of work, rather than as individuals with individual needs. Care areas without clear lines of accountability or policies and procedures that do not clearly state acceptable (and unacceptable) staff behaviours facilitate, or at least do not inhibit, care that is of poor quality or could be categorized as abuse.

As identified above, some client groups are more vulnerable to abuse than others. Further examples in care settings include those who:

Use of restraint

The forcible restraint of individuals within care settings is controversial. The scenario in Box 7.9 describes a situation that relates to care of a child, but the principles can be generalized to care of patients and clients of varying ages and with diverse needs.

Restraint of a child

Anna is a student undertaking a placement within a children’s hospital. She is involved, under the supervision of her mentor, in carrying out a variety of procedures for young children, but is uneasy about the use of restraint to ensure that the children remain still and by the distress that this causes some of the children. Anna wonders whether this use of restraint is justifiable.

The United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child was based on the premise that children have an active contribution to make within society (United Nations [UN] 1989). Collins (1999) points out that the restraint of children was, until recently, considered to be acceptable practice and uncontroversial. Restraint continues to be used by either a parent or carer during immunization by injection, venepuncture and lumbar puncture. Gray (2002) suggests that the effect of the UN Convention, UK legislation and societal changes in the perception of the role of children within society has resulted in an unfavourable view of restraint, which is now more widely considered to be an outdated practice. Pederson and Harbury (1995) identified that time constraints, coupled with a lack of knowledge of distraction techniques, was one reason provided to justify the use of restraint. A survey carried out by Robinson and Collier (1997) suggested that paediatric nurses perceived restraint as a quick and easy means of ensuring that procedures were completed quickly and safely (although 69% of respondents did identify that restraint was a major cause of distress to children). Collins (1999) suggested that use of restraint resulted from nurses’ lack of understanding of the efficacy of using distraction and relaxation as a means of reducing pain and distress in children undergoing procedures. Gay (1991) had earlier described the use of dolls to provide a visual demonstration to children of the procedure that they were about to undergo and also identified that providing an opportunity for children, where possible, to handle real or modified equipment reduced their anxiety levels.

The Royal College of Nursing (RCN 1999) published guidelines that placed emphasis upon prior explanations to the child about procedures and the use of alternatives to restraint, e.g. distraction, wherever possible. The RCN also identified the need for development and implementation of policies and procedures that specified:

The minimum amount of restraint necessary should be used, for the shortest duration possible, accompanied by clear explanations to the child as to what is happening. Ongoing discussion among staff of issues surrounding child restraint and a procedure for registering any disquiet should be clearly explained. Documentation is required (NMC 2005c) of the need for restraint, the method used, its duration and any discernible effect on the child.

It may be seen from the above that the disquiet that Anna experienced in the situation outlined in Box 7.9 was justified. It may be that the situations in which Anna witnessed (and perhaps participated in) the restraint of children were those in which the actions of staff were justified, but it is important that restraint is not carried out without reflection on, and in, practice and that an evidence base is used to support the rationale for its use (see Chs 4, 5). If practices that appear to cause patients or clients distress are implemented, it is of particular importance that the rationale for these is explained and that potential alternatives are explored.

Ethical frameworks and models

Reflecting on, and in, practice can be structured (Ch. 4). In relation to ethical problems or dilemmas, frameworks or models may also be used to reach decisions in specific situations. There are a number of frameworks that may be used to explore ethically sensitive situations. One example is Seedhouse’s (1988) ‘ethical grid’ and another is that of Brown et al (1992). The DECIDE model (Thompson et al 2006, p. 323) will be used to explore the situation in Box 7.11.

Whose rights?

Tom is a young man who has a diagnosis of schizophrenia. He has been in hospital on two occasions when his experiences have been causing him distress. He now lives in a community house with support from a residential care worker and a community mental health nurse. Tom takes medication as prescribed which alleviates, but does not eradicate, some of his distressing thoughts, experiences and feelings. These include hearing voices (auditory hallucinations) that mock and frighten him, and the consequent feelings of suspicion and uneasiness cause him considerable distress.

Some of the residents in the neighbourhood raised objections when the proposal for the community house was put forward 2 years ago because they were under the misapprehension that people who had mental health problems might display antisocial behaviour. Tom has, on several occasions, shouted in the street in response to the distress caused by his auditory hallucinations. Tom’s feelings of mistrust understandably worsen when people stare at and talk about him. Neighbours are worried about his shouting, believing it is directed at them, and complain that it has become unsafe for their children to walk, or play, outdoors because of Tom’s behaviour.

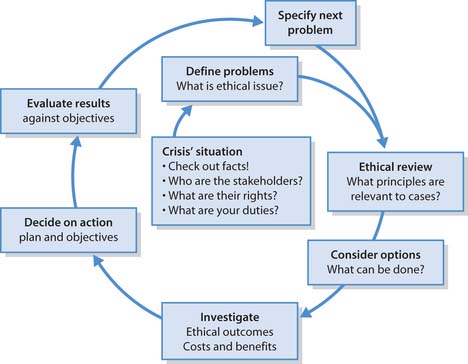

The DECIDE model

The authors of the DECIDE model (Thompson et al 2006, p. 323) (Fig. 7.2) advocate that, in a crisis situation (originally defined in Greek as a ‘decision time’), a structured series of questions can be used to assist ethical problem-solving. These are shown in Box 7.10. The first step is to verify the facts, then identify the ‘stakeholders’ (i.e. those who are interested parties in the situation). The rights of the stakeholders are then established, as are the duties of other parties in relation to fulfilment of these.

Fig. 7.2 The DECIDE model for ethical decision-making

(reproduced with permission from Thompson et al 2006)

[From Thompson et al 2006, p. 324]

D – Define the problem(s)

What are the key facts of the case? Who is involved? What are their rights, your duties? What is the main ethical problem to be addressed?

E – Ethical review

What ethical principles have a bearing on the case and which principle or principles should be given priority in making your decision?

C – Consider the options

What options do you have in the situation? What alternative courses of action? What help, means and methods do you need to use?

I – Investigate outcomes

Given each available option, what consequences are likely to follow from each course of action open to you? Which is the most ethical thing to do?

Following this initial process, it is important to define the problem and to identify the relevant ethical issue(s). Once this has been established, a review to identify the eth-ically relevant principles is carried out and then the available options are considered. Investigation of the options explores their potential outcomes and the costs and benefits attached to each. The action that is deemed most appropriate is then decided upon, implemented and subsequently evaluated for its effectiveness, or otherwise, in solving, or at least alleviating, the problem.

The DECIDE model in practice

The following discussion illustrates the issues that may arise from the activities in Box 7.11 and, because the scenario is brief, there is limited information on which to base a discussion. It is not intended to provide the ‘ideal’ answer. The steps of the DECIDE model are each considered in turn using the framework in Box 7.10.

Defining the problem(s)

The first step is to verify the facts, which are:

The stakeholders are Tom, the neighbours who complained that Tom’s behaviour was threatening, Tom’s support workers (including yourself as the registered nurse), his psychiatrist and, in a wider sense, possibly other individuals who have mental health problems, and all other members of society.

The rights of all the stakeholders appear to be those of freedom (autonomy) to live their lives within society. Your duty, as the registered nurse responsible for Tom’s care, is to act to ensure that Tom’s best interests are served (NMC 2004). You do, however, also have a duty to take action if you consider that Tom’s behaviour presents an actual threat to others. You have a duty to comply with your contract of employment.

The next step is to define the problem and, as the problem is not only practical (e.g. accompanying Tom to the shops) but also has implications for Tom’s future health, freedom and well-being (and also has implications for the perceived freedom of some of the neighbours and their children), it appears to be an ethical problem.

Ethical review

The next stage of the model is to review the ethical elements. These appear to be those of competing rights, i.e. Tom’s right to move around freely and not to be prescribed medication to the point where the side-effects (including lethargy and drowsiness) would impede this right. The principles involved are:

Unless Tom is being held under an appropriate section of the Mental Health Act (see Further reading and Ch. 6) he is entitled to freedom of movement. The ethical review would include acknowledgement of your duty as the registered nurse responsible for Tom’s care to uphold his best interests and to act as his advocate if required to do so.

The rights of the neighbours to be free from harassment are also important within the ethical review, but it is not clear that there is an actual threat to their well-being. Their negative perception of Tom’s behaviour may be based on a lack of knowledge about the nature of his illness and this may be fuelled by negative and inaccurate media representations of people who have a mental health problem (DH 2003).

Consider and investigate options

The next two stages in the DECIDE model (see Fig. 7.2) are identification of the options available and investigation of what would constitute ethically acceptable outcomes, including the costs and benefits of each. The options in this case appear to be:

Your duty, as the registered nurse responsible for Tom’s care, is to act to ensure that Tom’s best interests are served (NMC 2004) and to act as his advocate if required to do so. The term advocacy has its origins in the judicial system and retains rather a confrontational association. An advocate is an individual who speaks on behalf of another, either in response to a request from that person or because their position in relation to the other person may require them to do so. The position of registered nurses in relation to their clients, so far as the Code of Professional Conduct (NMC 2004) is concerned, is that the nurse should support the client’s best interests and this may be assumed to include advocacy, if required. There are arguments for, and against, registered nurses adopting advocacy roles in relation to their clients (see Ch. 6). It may be argued, for example, that independent advocates (i.e. those who have no other formal input into the client’s care) are better placed to act purely in accordance with the client’s known, or assumed, wishes.

Decide on action

The next stage is to decide on action, in conjunction with Tom, and to compile a plan and identify objectives. The investigation indicated that the best action might be to speak with Tom in an attempt to explore how he understands and feels about the situation and to speak with the neighbours, ensuring that specific details of Tom’s condition were not discussed, thus maintaining client confidentiality. Reassuring the neighbours that Tom did not present a risk to their safety would be important and they might wish advice as to how best to interact with Tom when they meet. With Tom’s permission, it might be useful for him to meet with the neighbours, accompanied by an independent advocate.

Evaluate results

The final stage of the DECIDE model (see Fig. 7.2) is an evaluation of the effectiveness of the action taken. This may be measured against the objectives that were identified during the decision stage, so those who worked with Tom, Tom himself and the neighbours would be able to provide feedback as to whether the intended objectives had been fully, or partially, met. (There is a further step in the DECIDE model, which is to specify the next problem; whether another problem would arise would remain to be seen.)

While the above scenario was used to demonstrate application of the DECIDE model (Thompson et al 2006, p. 323), the framework it provides is relevant across a wide range of healthcare settings and for individuals with varying needs. Box 7.12 provides an opportunity for you to reflect on a situation within your own practice.

| Children’s rights | www.crae.org.uk |

| Available July 2006 | |

| Nursing and Midwifery Council | www.nmc-uk.org |

| Available July 2006 |

ASH (Action on Smoking and Health). 2002 Basic facts: Three – Taxation. Online: www.ash.org.uk/html/factsheets.

Beauchamp TL, Childress JF. Principles of biomedical ethics, 5th edn. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2001.

Brown JM, Kitson AL, McKnight TJ. Challenges in caring: explorations in nursing and ethics. London: Chapman & Hall, 1992.

Collins P. Restraining children for painful procedures. Paediatric Nursing. 1999;11(3):14-16.

Department of Health. 1999 Working together to safeguard children. Online: http://www.dh.gov.uk/assetRoot/04/07/58/24/04075824.pdf. Available July 2006

Department of Health. No secrets: guidance on developing and implementing multi-agency policies and procedures to protect vulnerable adults from abuse. London: TSO, 2000.

Department of Health. 2003 Attitudes to mental illness 2003: Report. Online: www.dh.gov.uk/assetRoot/04/07/91/16/0479116.pdf.

Downie RS, Calman KC. Healthy respect: ethics in health care, 2nd edn. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1994.

Edwards R. The problem of tobacco smoking. British Medical Journal. 2004;328:217-219.

Gay J. Caring for children in A&E. Paediatric Nursing. 1991;3(7):21-23.

Gray J. Conscious sedation of children in A&E. Emergency Nurse. 2002;9(8):26-31.

HM Government. Data Protection Act. London: TSO, 1998.

HM Government. Public Disclosure at Work Act. London: TSO, 1998.

HM Government. 2003 Green Paper. Every child matters. TSO, London. Online: www.dfes.gov.uk/everychildmatters.

Macintyre A. After virtue, 2nd edn. Notre Dame: Notre Dame University Press, 1981.

Nursing and Midwifery Council. Professional advice from the NMC. London: NMC, 2002.

Nursing and Midwifery Council. An NMC guide for students of nursing and midwifery. London: NMC, 2002.

Nursing and Midwifery Council. Guidelines for mental health and learning disabilities nursing. London: NMC, 2002.

Nursing and Midwifery Council. Practitioner–client relationships and the prevention of abuse. London: NMC, 2002.

Nursing and Midwifery Council. Code of professional conduct: standards for conduct, performance and ethics. London: NMC, 2004.

Nursing and Midwifery Council. Standards of proficiency for pre-registration nursing education. London: NMC, 2005.

Nursing and Midwifery Council. The PREP handbook. London: NMC, 2005.

Nursing and Midwifery Council. Guidelines for records and record keeping. London: NMC, 2005.

Pederson C, Harbury B. Nurses’ use of nonpharmacologic techniques with hospitalized children. Issues in Comprehensive Pediatric Nursing. 1995;18:91-109.

Robinson S, Collier J. Holding children still for procedures. Paediatric Nursing. 1997;9(4):12-14.

Royal College of Nursing. Restraining, holding still and containing children: guidance for good practice. London: RCN, 1999.

Royal College of Nursing. Dealing with harassment and bullying at work: a guide for RCN members. London: RCN, 2000.

Royal College of Nursing. Dealing with bullying and harassment: a guide for nursing students. London: RCN, 2002.

Seedhouse D. Ethics: the heart of health care. Chichester: Wiley, 1988.

Thompson IE, Melia KM, Boyd KM. Nursing ethics, 4th edn. Edinburgh: Churchill Livingstone, 2000.

Thompson IE, Melia KM, Boyd KM, Horsburgh D. Nursing ethics, 5th edn. Edinburgh: Churchill Livingstone, 2006.

United Nations. The United Nations convention on the rights of the child. London: CRDU, 1989.

Wardhaugh J, Wilding P. Towards an explanation of the corruption of care. In: Allott M, Robb M, editors. Understanding health and social care: an introductory reader. London: Sage, 1998.

Allott M, Robb M, editors. Understanding health and social care: an introductory reader. London: Sage, 1998.

Beauchamp TL, Childress JF. Principles of biomedical ethics, 5th edn. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2001.

Downie RS, Calman KC. Healthy respect: ethics in health care, 2nd edn. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1994.

HM Government. Mental Health Act. London (currently under review): TSO, 1983.

HM Government. Mental Health (Northern Ireland) Order. London: TSO, 1986.

HM Government. Mental Health (Amendment) (Northern Ireland) Order. London: TSO, 2004.

Nursing and Midwifery Council. Supporting nurses and midwives through lifelong learning. London: NMC, 2002.

Scottish Executive. Mental Health (Care and Treatment) (Scotland) Act. Edinburgh: TSO, 2003.

ETHICAL ISSUES

ETHICAL ISSUES REFLECTIVE PRACTICE

REFLECTIVE PRACTICE CRITICAL THINKING

CRITICAL THINKING