Chapter 6 Legal issues that impact on nursing practice

Introduction

This chapter provides an overview of the law as it pertains to nursing. Issues that affect all branches of nursing are discussed as well as how legislation and the law influence specific branches. The law varies across the UK and the emphasis here is on the law in England and Wales. Readers should always be aware of the situation in their part of the UK.

It is important that nurses are aware of how the law affects nursing and always consider it in their day-to-day practice. Often it is only when something ‘goes wrong’ that nurses consider the law.

It is important to emphasize, however, that the law and nursing practice are subject to constant change. Often, the changes affecting nursing practice are the result of research and evidence-based practice (see Ch. 5). Legislation is not static and changes arise from new cases and current issues in society. The development and interpretation of law and its relationship to nursing and healthcare must always be considered. Professional and ethical issues pertain to this and it is important for nurses to think about how changes may influence practice. In addition, significant changes affecting patient rights, changes within the NHS and government initiatives must also be considered in relation to the law, to the practitioner and to the patient/client.

The law is a specialist area with its own language but it is highly relevant to nurses and their practice. All practitioners should maintain knowledge of and adherence to the law as it is important to standards and expectations of practice, patient/client outcomes and public well-being.

The law is discussed with the aim of providing a better understanding of relevant terminology and various systems of law related to nursing. This includes a brief discussion of the legal frameworks in England and Wales. Although differences in the law and legal systems in Scotland and Northern Ireland exist, it is worth remembering that there are common areas (Tingle & Cribb 2003). Important legislation related to different branches of nursing is reviewed.

Legal frameworks

A country’s system of justice reflects its morals, history and politics. UK law and the structures within it have developed over hundreds of years. Terms, titles and legislation and systems of law all stem from the past and from tradition. An understanding of the law is necessary in order to meet standards of practice, ethical and professional responsibilities, and more importantly because the law represents society’s judgement on these standards.

Types and sources of law

The legal system within the UK is divided into two divisions: public and private law. Public law is concerned with preserving the order of society whereas private law is concerned chiefly with disputes between individuals (Dimond 1995). The law is further divided into:

The difference between criminal and civil law is reflected in the courts and procedures, and the sanctions which may be applied. For example, most crim-inal cases are heard in the Magistrates’ court with serious or complex cases heard in the Crown court. The Crown Prosecution Service or another prosecuting body brings the case against the defendant. Civil cases are between the claimant and another person or organization and are heard in the County court or the High court depending on the amount of damages or degree of harm.

European Community law is binding on UK courts. Decisions made by the European Court of Justice may be directly binding on English courts.

Acts of Parliament

Most English law is in the form of Acts of Parliament (statutes). An Act of Parliament is primary legislation, e.g. the Disability Discrimination Act 2005. Statutory instruments (subordinate or secondary legislation) made under delegated powers provide the regulations needed to implement a particular Act.

An Act results from a Bill (a draft proposal). Proposals for legislative changes may be contained in government White Papers. Consultation papers, sometimes called Green Papers, which set out government proposals and seek comments from interested parties, including the public, may precede these. There is no requirement for there to be a White or Green Paper before a Bill is introduced into Parliament.

The draft proposal or Bill is introduced into either the House of Commons (the elected Lower house) or the House of Lords or Upper house (currently an unelected body). The procedure of passing a Bill is similar in both Houses, and has seven stages (Fig. 6.1). If both Houses vote for the proposal then the Bill is ready to become an Act; however, it only becomes law after receiving Royal Assent.

The law undergoes constant reform in the courts as established principles are interpreted, clarified or reapplied to meet new circumstances; laws become outdated, new policies require new laws, or new laws are needed to ensure that the UK complies with international or European Law, e.g. The Human Rights Act 1998 (see pp. 150 and 151).

Case or common law – judge-made law

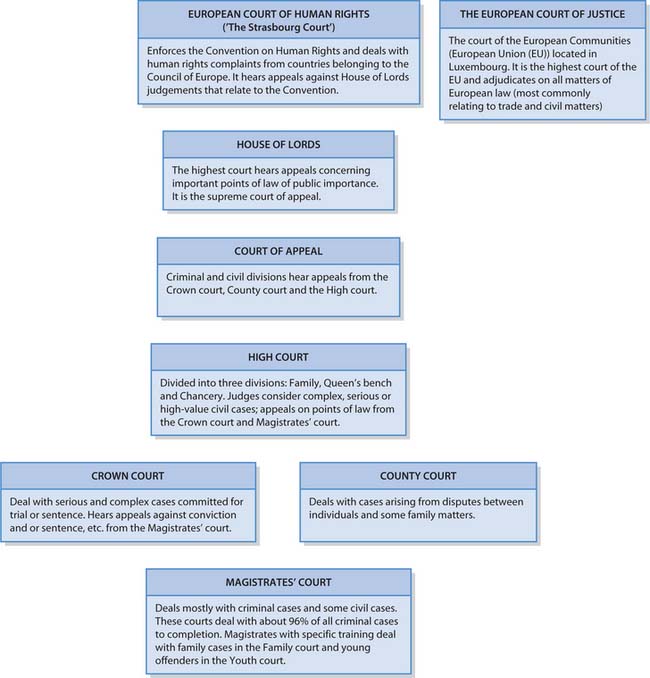

Case law or judge-made law predates statute; however, common law rules may be regarded as secondary because of the many statutes that now exist. The rules in case law are derived from legal principles laid down by judges over many years. Nevertheless, case law still remains an important source of law, particularly in negligence cases (see pp. 155–157). Case law is subject to a system of precedent where the earlier decisions made by a higher court mean that a lower court must follow their decision. Rulings of the House of Lords (the highest court) are binding on all lower courts, whereas those of the Court of Appeal are generally binding on lower courts (McHale & Tingle 2001) (see Fig. 6.2).

Court system in England and Wales

The hierarchy of the court system (criminal and civil proceedings) in England and Wales is outlined in Figure 6.2.

Important legislation for nursing

There are many diverse Acts of Parliament relevant to nursing. Although detailed discussion of every Act is beyond the scope of this book, Table 6.1 (see p. 152) outlines some important Acts and sources of information. However, some – such as The Human Rights Act 1998 and The Children Act 2004, both of which have far-reaching effects – are discussed here in more detail, or covered later in the chapter.

Table 6.1 Important legislation for nursing (England and Wales)

| Act of Parliament | Where to access the Act or Explanatory notes |

|---|---|

| Access to Health Records Act 1990 | www.opsi.gov.uk/acts/acts1990/Ukpga_19900023_en_1.htm Available July 2006 |

| Children Act 1989 (see pp. 152 and 158) | www.opsi.gov.uk/acts/acts1989/Ukpga_19890041_en_1.htm Available July 2006 |

| Children Act 2004 (see p. 152) | www.opsi.gov.uk/acts/en2004/2004en31.htm Available July 2006 |

| Data Protection Act 1998 (DPA) (see p. 152) | www.opsi.gov.uk/acts/acts1998/19980029.htm Available July 2006 |

| Disability Discrimination Act 2005 | www.opsi.gov.uk/acts/acts2005/20050013.htm Available July 2006 |

| www.opsi.gov.uk/acts/en2005/2005en13.htm Available July 2006 | |

| Freedom of Information Act 2000 | www.opsi.gov.uk/acts/acts2000/20000036.htm Available July 2006 |

| www.informationcommissioner.gov.uk/eventual.aspx?id_33 Available July 2006 | |

| www.opsi.gov.uk/acts/en2000/2000en36.htm Available July 2006 | |

| www.foi.nhs.uk/act_home.html Available July 2006 | |

| Health and Safety at Work Act 1974 (see Ch. 13) | Health and Safety Executive – www.hse.gov.uk Available July 2006 |

| Health and Social Care Act 2001 | www.opsi.gov.uk/acts/en2001/2001en15.htm Available July 2006 |

| Human Rights Act 1998 (HRA) (see below and p. 151) | www.opsi.gov.uk/acts/acts1998/19980042.htm Available July 2006 |

| Human Tissue Act 2004 (see p. 161) | www.opsi.gov.uk/acts/en2004/2004en30.htm Available July 2006 |

| www.uktransplant.org.uk Available July 2006 | |

| Medicinal Products: Prescription by Nurse Act 1992 (see Ch. 22) | www.uk-legislation.hmso.gov.uk/acts/acts1992/Ukpga_19920028_en_1.htm |

| Available July 2006 | |

| Mental Capacity Act 2005 (see pp. 160 and 161) | www.opsi.gov.uk/acts/en2005/2005en09.htm Available July 2006 |

| www.opsi.gov.uk/acts/acts2005/20050009.htm Available July 2006 | |

| Mental Health Act 1983 (MHA) (see pp. 151 and 152) | www.direct.gov.uk/DisabledPeople/HealthAndSupport/YourRightsInHealth/ |

| HealthRightsArticles/fs/en?CONTENT_ID_4014771&chk_jVhUS1 Available July 2006 | |

| Public Interest Disclosure Act 1998 | www.opsi.gov.uk/acts/acts1998/19980023.htm Available July 2006 |

The Human Rights Act

The Human Rights Act (HRA 1998) is wide ranging and promises that the state will respect the rights and freedoms of individuals. Human rights are very much a part of everyday life – as citizens, professionals, patients and clients (McHale & Gallagher 2004). Nurses need to be aware of the potential implications of the Act for their practice and care provision. The HRA 1998 applies to children (a person under the age of 18) as well as adults.

The HRA 1998, which became law in 2000, incorporates the rights and freedoms guaranteed under the European Convention on Human Rights (the Convention). The Convention was drafted following World War 2 and the UK was one of the first countries to sign up in 1953. In total, 45 countries signed and these make up the Council of Europe. The Convention confers a number of rights on people (Tingle & Cribb 2003). It is divided into schedules, which are further divided into articles. These are:

Since the HRA 1998 came into effect in 2000, English courts deciding on a matter connected with one of the rights must, as far as applicable, have regard to decisions made by the Strasbourg Court (McHale & Tingle 2001). In addition, new legislation must also comply. It also means that all public bodies must act in accordance with the Convention, including the healthcare system (Tingle & Cribb 2003).

It is worthwhile considering how some HRA Articles impact on nursing practice (Box 6.1). Nurses act as advocates for their patients/clients, to safeguard standards of care and to speak out where the patient/client may be at risk. The Nursing and Midwifery Council (NMC) code of professional conduct: standards for conduct, performance and ethics (NMC 2004) already requires registrants to bring any circumstances that may compromise patient/client care and safety to the attention of an appropriate authority. Article 2 reinforces this professional obligation.

The Human Rights Act and nursing practice

[Resource: Study Guide. Human Rights Act 1998, 2nd edn –www.humanrights.gov.uk/pdf/act/act-studyguide.pdf]

Article 2 has clear implications for decisions regarding withholding and/or withdrawing of life-preserving or life-saving treatment. It must be clear, however, that there will always be challenges with regard to non-resuscitation orders and demands for more aggressive treatments for people with serious illness.

Article 3 states that no one shall be subject to torture or inhumane degrading treatment or punishment. Inhumane treatment is deemed to be any treatment that causes intense physical and mental suffering.

Mental health legislation

In England and Wales the Mental Health Act (MHA) 1983 (Department of Health [DH] 1983) currently makes provision for the compulsory detention and treatment in hospital of those with a mental disorder. It is important to remember that many people with mental health problems are in hospital as voluntary or informal patients, i.e. not detained there under any provision of the MHA. Following consultation on updating the MHA 1983, including a draft Mental Health Bill 2004, the Government announced in 2006 that a shorter Bill would amend the 1983 Act.

The Mental Health (Care and Treatment) (Scotland) Act 2003 is the legal authority for mental health services in Scotland. Unlike the Scottish Mental Health Act (1984), the new Act is rights-based and underpinned by a set of guiding principles. These help to set the tone of the Act and guide its interpretation. As a general rule, anyone who takes any action under the Act has to take account of the principles (see www.nes.scot.nhs.uk/mha).

At the time of writing an independent review of mental health and learning disability (law, policy and provisions) is in progress in Northern Ireland (see www.rmhldni.gov.uk).

It is important to remember that mental health issues and mental health legislation can affect anyone and involves all areas of healthcare (Box 6.2).

Mental distress

Sam is wandering in and out of the local pub and the takeaway. It is a busy Saturday evening and he is increasingly agitated and distressed by the noise, traffic and unfamiliar people. The pub landlord calls the police when Sam starts shouting at people having a meal. The police officer, who knows Sam well, is worried about his distressed state and, also noticing that he has a head wound, summons an ambulance. When Sam arrives at the Emergency Department accompanied by the police officer he is very distressed and will not allow the staff near him. The charge nurse fears for Sam’s safety. The duty psychiatrist is asked to come to the department to assess Sam.

The MHA 1983 (Section 1, p. 2) describes four categories of mental disorder:

Conditions generally accepted as falling under the category of ‘mental illnesses’ include schizophrenia and mood disorders (depression and manic behaviour). Most admissions under the MHA 1983 requiring the category of mental disorder to be specified are admissions of people with a diagnosis of a ‘mental illness’.

The Children Act 2004 and child protection

The Children Act 2004 is an important piece of legislation in the protection and welfare of children. The impetus for this legislation was the death of Victoria Climbié and the subsequent inquiry into the circumstances of her death chaired by Lord Laming (Box 6.3). Background to the Children Act 2004 can be accessed at the Department for Education and Skills (DfES) website (www.dfes.gov.uk/publications/childrenactreport); this includes:

Safeguarding children

Victoria Climbié was abused, neglected and tortured to death by her great-aunt and the woman’s boyfriend. Both were convicted of murder and sentenced to life imprisonment.

The police, health professionals and social services all had contact with Victoria while she was being abused. A public inquiry chaired by Lord Laming exposed a picture of incompetence and error at every level. Lord Laming promised to make recommendations to ensure such a tragedy never happens again.

Student activities

[Resources: BBC – news.bbc.co.uk/1/hi/in_depth/uk/2002/victoria_climbie_inquiry/default.stm; Victoria Climbié Inquiry – www.victoria-climbie-inquiry.org.uk; England: Department for Education and Skills – www.everychildmatters.gov.uk/socialcare; Northern Ireland: Department of Health, Social Services and Public Safety – www.dhsspsni.gov.uk/index/health_and_social_services/child_care/child_protection/child_protection_links.htm; Scotland: Scottish Executive – www.scotland.gov.uk/Topics/People/Young-People/children-families/17834/10227; Wales: All Wales Unit – www.allwalesunit.gov.uk All available July 2006]

The report into the death of Victoria Climbié urged majorreforms of children’s services. The Children Act 2004 (and subsequent Regulations) provides the legislation for wide-ranging strategies for improving children’s lives including the appointment of a Children’s Commissioner. The Act deals with the services which all children use, and the services needed by children who have additional needs (DfES website 2005) (see Ch. 3). The Act aims to ensure that the planning, commissioning and delivery of children’s services are integrated. Other aims include improving multidisciplinary working, preventing duplication, integrating inspection procedures and increasing accountability (DfES website 2005). The legislation allows local authorities flexibility in the ways they provide children’s services.

Where healthcare professionals suspect that a child may be neglected or abused by parents/carers or others, they have a clear duty to act. The action taken will be determined by the immediacy for protection, treatment or care. NHS Trusts etc. and local authorities have child protection policies that must be followed by healthcare professionals and others working with children (see Box 6.3). Nurses should note the NMC position on the matter of confidentiality in child protection matters: ‘Where there is an issue of child protection, you must act at all times in accordance with national and local policies’ (NMC 2004, Clause 5.4, p. 9).

Data Protection Act 1998

The provisions of the Data Protection Act (DPA) 1998 are designed to balance the right of individuals to privacy and the rights of those people/organizations who have valid reasons for holding and using personal data, such as healthcare professionals. The DPA provides people with some rights about data held about them but also sets out certain duties/obligations for the people/organizations that collect, hold and process such information.

Nurses have a responsibility to protect data as most manage, or will manage, personal information about people (see also ‘Documentation and record keeping’, p. 154, and ‘Confidentiality’, p. 157). The DPA sets out eight principles of good practice, e.g. data held must be accurate. Readers requiring more information are directed to the Data Protection Act Factsheet produced by the Information Commissioner (2005).

It is also important to be aware of the patient’s/client’s rights in relation to personal information held about them, how it is managed and how they can request access to it (see Access to Health Records Act 1990, Table 6.1). The DPA, the HRA 1998 (see pp. 150 and 151) and the Freedom of Information Act 2000 (see Table 6.1) are interlinked.

Legal concepts integral to nursing

This section considers legal concepts that are important for nurses, including safeguards for practice, duty of care, negligence, consent, etc. Nurses are accountable for their actions and omissions (see Ch. 7). Registered nurses remain accountable even when acting on the instructions of another practitioner such as when administering drugs prescribed by a doctor. The nurse has responsibilities even where a doctor has made the original mistake. Nurses must always challenge lack of clarity, errors or discrepancy in a drug prescription or other treatment.

There are four arenas of accountability relating to the nurse’s duty of care and negligence, etc. These are:

All four arenas are discussed more fully in this section (see pp. 155–157).

Safeguards for practice

There are various safeguards that protect both patients/clients and the nurses accountable for planning and providing care. Several of these, such as statutory regulation, professional indemnity insurance, documentation and record keeping, are discussed below.

Statutory regulation (see Ch. 7 for detailed coverage)

Health professionals are subject to statutory regulation, e.g. the General Medical Council (GMC) regulates doctors; the Health Professions Council (HPC) currently regulates 13 professions including dietitians, physiotherapists, etc. The Nursing and Midwifery Council (NMC) is the regulating body in the UK for nurses, midwives and specialist community public health nurses. At the time of writing, wide-ranging reviews of non-medical and medical professional regulation are due to report. It is likely that the number and functions of regulatory bodies will change. The purpose of statutory regulation is to ensure standards of care and practice and to provide protection for the public. The NMC regulates the profession and maintains a register of practitioners (Box 6.4). When a practitioner seeks employment the employer would ensure the practitioner is registered with the NMC as well as requiring a satisfactory Criminal Records Bureau check.

Fitness to practise

Registered practitioners must be ‘fit to practise’, meaning that they meet standards for safe practice and work within guidelines of professional and safe practice.

Student activities

The law protects the title of registered nurse, midwife, etc. and it is a criminal offence to use the title without being registered with the NMC.

The NMC Code of professional conduct: standards for conduct, performance and ethics (NMC 2004) (see Ch. 7) has two key functions: to inform the profession of the standard of professional conduct of registered practitioners, and to inform the public, other professionals and employers of those standards and conduct expected of professionals.

For student nurses, their training and education must include essential placement hours and core skills. These are mandatory requirements for professional registration and must be achieved by student nurses before registration. Once a nurse qualifies, the NMC continues to monitor professional development and education as a requirement for periodic registration (see Ch. 7).

The NMC provides guidance for clinical experience to student nurses (see Ch. 7). For example, student nurses must always introduce and identify themselves as students, as some patients/clients may not wish to be cared for by a student nurse. If the patient/client asks the student nurse to leave they must do so (NMC 2005a). Although student nurses are not accountable professionally to the NMC until they become registered, they can be called to account by the law or their college or university for any actions or omissions (NMC 2005a).

Contracts of employment

Employees are protected by a contract of employment but have responsibilities to the employer to fulfil their contractual obligations. Thus, the nurse’s employer would have the expectation that the nurse acts in accordance with that contract, e.g. keeping confidential information secure. In an employment contract, boundaries or limitations of practice are clearly stated and responsibilities identified. It is important to be aware of how the employer and the practitioner interpret it. A job descrip-tion should provide clear expectations of the practitioner and identify functions expected within that role. Contracts also protect the employer. For example, if a nurse were to practise outside their job description or contract, their employer may not accept liability for any negligent acts or omissions (see p. 155).

Direct liability is where the employer is at fault; indirect or vicarious liability is when the practitioner is at fault. Some employers accept the liability (see below) but others may not.

When disputes arise between employee and employer they may be referred to an industrial tribunal. These hear unfair dismissal, discrimination and other cases in relation to statutory employment rights as well as some breach of contract actions.

Professional indemnity insurance

The NMC recommends that registrants have professional indemnity in the event of a claim for negligence: ‘Some employers accept vicarious liability for negligent acts and/or omissions of their employees’ (NMC 2004, Clause 9.2, p. 12). However, this cover does not include actions outside work. Registrants working independently will need to obtain their own insurance cover. As some agency work may not be covered by insurance, registrants should check their insurance status and if necessary obtain cover through a professional organization or trade union, such as the Royal College of Nursing (RCN). It is important for practitioners to be aware of professional responsibilities and boundaries, and have an appreciation for the law.

Conscientious objection

Healthcare professionals, patients or their family may have a conscientious objection to a particular clinical procedure, e.g. termination of pregnancy. Nurses may object to their participation in abortion on religious or cultural grounds. The Abortion Act 1967 gives the nurse the right to refuse to be involved in these clinical procedures. However, the statutory right of conscientious objection does not extend to those persons more remotely connected to the abortion process (McHale & Tingle 2001). The NMC (2004, Clause 2.5, p. 5) states that:

Policies, procedures and guidelines

In addition to the guidance provided by The NMC Code of professional conduct: standards for conduct, performance and ethics (NMC 2004), nurses have access to national guidelines and local policies, procedures and practice guidelines produced by their employer (see Ch. 5). Nurses must also consider how the law affects professional guidelines, practice and patient/client outcomes.

Documentation and record keeping

Proper documentation is a fundamental aspect of recording what nurses do and how they decide on a particular course of action. There is a saying that ‘if nursing care is not written down then it did not happen’. As nursing records can be used in evidence in a variety of settings, including professional conduct hearings and courts, what is documented and how care is documented are extremely important (Box 6.5). Full and accurate records can protect the nurse if allegations of poor or negligentcare are made. The NMC publication Guidelines for Recordsand Record Keeping (NMC 2005b) offers guidance and allnurses should be familiar with its contents. In addition, the Access to Health Records Act 1990 ensures that recordsare accurate and used appropriately by those to whom they relate and others, such as nurses and the multidisciplinary team (MDT).

Documentation and record keeping

Sean’s folder is kept at the end of his bed. It contains his drug chart, observation record, nursing progress notes and care plan. Sean’s records of previous admissions, tests and doctors’ notes are kept in a different folder near the nurses’ station.

He can access the folder at his bedside quite easily and he does so, reading through the nurses’ notes. One entry reads:

02.00 – Pt not sleeping well. Pt c/o of breathlessness throughout the night and appeared anxious. Assisted pt ++ and repositioned many times.

04.00 – Pt spent most of the night in an upright position.

06.00 – Still c/o of difficulty. Pt using inhalers ++ with little effect.

Oxygen therapy remains at 2 L per min and breathing remains poor. Doctor aware and for reassessment later today.

The interpretation of what is written may be quite different from its intended meaning. The example in Box 6.5 may be viewed as uncaring or judgemental. It may be seen as lacking professionalism. Sparse detail and abbreviations can make the meaning unclear and open to misinterpretation if used in a court of law. Information needs to be accurate, measurable, quantifiable and qualitative. For example, ‘11’ portrays none of these. Documentation is a means of recording data about a patient/client, which the MDT may share. Documentation that lacks clarity or meaning is dangerous and fails to achieve what it was intended to do.

Reporting incidents/accidents (see Ch. 13)

Following any clinical incident – whether it is a drug error, verbal abuse or violence, or accident or injury to a patient/client, staff, visitor or member of the public – it is essential that this be reported and documented (Box 6.6). Importantly, ‘near misses’ should also be reported and documented.

Reporting incidents/accidents

Reflect on an incident or accident that occurred while on placement. Who completed the incident form, when was it completed and what information was recorded?

A statement is a formal account and record of an incident or sequence of events. It is prepared by the person(s) involved, e.g. the staff nurse who witnessed the incident or was involved in the event. As an incident form has limited space to record an event, the facts should be accurate and concise. All NHS organizations will have a protocol and forms for the reporting of clinical incidents (see Ch. 13).

In the case of litigation, records of this nature are used when presenting the facts in court and referred to in an investigation. Often, this may take months and therefore accurate documentation at the time of an incident is crucial.

In addition, some incidents, e.g. an injury lasting more than 3 days or a work-related disease, must be reported to the Health and Safety Executive under Reporting ofIncidents, Diseases and Dangerous Occurrences Regula-tions (RIDDOR) (see Ch. 13).

Duty of care and negligence

Nurses have a duty of care to patients/clients and visitors. This is the legal obligation to take reasonable care to avoid causing a person harm.

In addition, duty of care extends to off duty times. The NMC (2004, Clause 8.5, p. 11) states:

In an emergency, in or outside the work setting, you have a professional duty to provide care. The care provided would be judged against what could reasonably be expected from someone with your knowledge, skills and abilities when placed in those particular circumstances.

Once a nurse volunteers to help in an emergency, then a duty of care is assumed.

Nurses also have contractual obligations to their employer and a professional duty to safeguard the patient/client and standards of practice.

Negligence

Negligence is an act with any element of carelessness or lack of regard resulting in injury, harm or loss. It is any act or omission that falls short of a standard to be expected from ‘the reasonable man’. Negligence can result in a civil claim for compensation or in a criminal prosecution. Duty of care is an essential element in negligence claims (Box 6.7). There are three civil wrongs or torts, which must be proven for a successful claim of negligence. They are:

Staff nurse Sue

Sue is a qualified nurse working a night shift in a nursing home. There are two care assistants working with Sue and a more senior nurse in charge of the home. The floor Sue is responsible for has several residents with dementia. The floor is busy and Sue is changing a dressing when she hears Joan, a resident in the next room, cry out several times.

Darren, one of the care assistants, comes in with a query and Sue asks him to check on Joan while she finishes the dressing. Meanwhile, Joan has attempted to get out of bed, falls and hits her head on the floor.

Later, an incident report (see p. 154) is completed. Joan suffered a minor head injury with swelling over one eye. Her family are informed and visit the next day. The family make a complaint about the nursing care, which eventually results in a claim for negligence.

It is estimated that hundreds of thousands of patients are harmed each year by medical errors (National Patient Safety Agency [NPSA] 2005). However, according to the NHS Litigation Authority (NHSLA) in 2004–2005 they received 5609 claims of clinical negligence and 3766 claims of non-clinical negligence against NHS bodies (NHSLA 2005). These figures represent a reduction in claims from the previous year; clinical negligence claims for 2003–2004 were 6251, with 3819 claims of non-clinical negligence (NHSLA 2005).

Interestingly, very few clinical claims actually reach the courts, as most are either abandoned by the claimant (38.01%) or settled out of court (43.1%) (NHSLA 2005). In an analysis of all the clinical claims handled by the NHSLA since 1995, 1.97% settled in court in favour of the patient (including claims brought on behalf of children), 0.5% of those going to court found in favour of the NHS with 16.42% still not resolved (NHSLA 2005).

If a nurse has been negligent, generally it is the employer, i.e. the NHS Trust, that will be sued but a claim may also be brought against the nurse. Most claims for clinical negligence since 1995 have been in the specialities of surgery and obstetrics and gynaecology, with nursing having the smallest number of claims. If the practitioner is self-employed, personal indemnity insurance is necessary, as they would be personally liable for their actions and omissions (see pp. 153–154).

It is essential that nurses recognize their accountability. It should be emphasized that being accountable for acts, omissions and outcomes means that nurses must consider the consequences of everything they do in relation to patient/client care.

Following an incident that results in an official complaint from the patient/client or family, the NHS Trust willinitiate a full and thorough investigation. A negligence claim is a lengthy process, whereby witnesses, the claimant and anyone else involved are questioned and investigated. The information is compiled such that statements given represent oral testimony of the events that occurred. Legal advice would be necessary during this process.

As mentioned earlier, there are four arenas in which nurses may be accountable and answerable for their acts and omissions: to their employer, to the NMC, in a civil court and in a criminal court. In some cases, the nurse will be answerable in all four arenas, e.g. in the event of a patient’s death caused by a drug error.

Accountability to employer

Where negligence has occurred and harm caused because the nurse failed to follow reasonable instruction, guidelines or protocols, the employer has the right to take disciplinary action against the employee. For example, a staff nurse failed to check the patency of an intravenous (i.v.) cannula prior to starting an i.v. infusion containing an antibiotic. Within 15 minutes the patient complained of pain and burning at the site. The staff nurse said that this sometimes happened and not to worry. The patient continued to have pain and told another nurse who looked at their arm. The i.v. fluid containing the antibiotic had infiltrated into the tissues (‘tissuing’) (see Ch. 19). Fortuitously, no tissue damage had occurred.

The incident was reported and investigated and it was found that the staff nurse had not followed local guidelines for the administration of i.v. antibiotics. The patient eventually made an official complaint.

The staff nurse was required by his employer to undertake further training in i.v. therapy and drug administration and to work under direct supervision until considered to be competent. The patient and their family received an apology from the NHS Trust and were informed of the remedial action. They were satisfied and decided not to take legal action.

Should a qualified nurse fail to practise safely or work within stated guidelines and protocols, their employer may require a period of supervised practice, action plans, training, counselling, disciplinary procedures such as oral or written warnings, and possibly suspension or dismissal. They may also make a report to the NMC.

Professional accountability to the NMC

If a nurse is accused of misconduct, such as an action/omission that is found to be negligent, or they are convicted of certain criminal offences, they will be reported to the NMC. The NMC reviews the information surrounding the allegation and informs the individual of the allegation made. An Investigating Committee decides whether there is a case to answer and also decides if interim suspension or interim conditions of practice are justified. If the Investigating Committee decides there is no case to answer the case is closed. On the other hand, if there is a case to answer it will be referred to the Conduct and Competence Committee (CCC) or to the Health Committee if the nurse is considered unfit to practise by virtue of their physical or mental health. The standard of proof required by the CCC is the criminal standard, but it is likely to become the civil standard. If the CCC finds the facts proven they may, depending on the degree of unfit practice and risk to the public, decide to:

Civil accountability

Nurses may encounter the civil courts in relation to negligence claims or trespass against the person (any interference with the person’s bodily integrity and liberty, including assault and battery, see p. 157) or other civil wrongs that the patient/client might suffer. When a patient/client suffers harm as a result of clinical negligence, they or the family can bring an action (claim) for negligence and compensation for the harm. In order to succeed in the claim, the three civil wrongs/torts must be met (see p. 155). The law recognizes duty of care between the patient and the nurse. When determining a breach in duty of care, the nurse’s conduct would be compared with what the ordinarily skilled nurse in that speciality would have done in the same circumstances, and what precautions would have been taken to avoid harm from known risks. Judges use the Bolam test when determining whether a nurse or other health professional has been negligent.

The Bolam test is a rule not only of substantive law in defining what amounts to adequate care, but is also used to determine standards of care. It is also a rule of evidence, indicating how a court determines whether adequate care has been given (Tingle & Cribb 2003). In determining the ‘legal standard’ of care, advice would be sought by lawyers acting for the nurse/NHS Trust, etc. and the claimant. If the case goes to court an ‘expert opinion’ is given by an expert witness. The judge would draw conclusions based on this standard of professional practice. It is important to note that the courts are more testing of expert evidence than in 1957.

These legal principles stem from the case of Bolam v Friern HMC [1957] 2 All ER 118 where a doctor administered electroconvulsive therapy to Mr Bolam without anaesthetic or muscle relaxants, resulting in Mr Bolam’s jaw being fractured. The judge, Mr Justice McNair, stated:

The test is the standard of the ordinary skilled man exercising and professing to have that special skill. A man need not possess the highest expert skill … it is sufficient if he exercises the ordinary skill of an ordinary competent man exercising that particular art…. a doctor is not guilty of negligence if he has acted in accordance with a practice accepted as proper by a responsible body of medical men skilled in that particular art…. Putting it the other way round, a doctor is not negligent if he is acting in accordance with such a practice, merely because there is a body of opinion that takes a contrary view.

His comments later became known as the ‘Bolam test’, which also applies to nurses and other health professionals.

Various systems exist where defended cases of negligence can be fast tracked according to the size of the claim. However, at the time of writing, an NHS Redress Scheme is proposed, whereby certain cases involving errors with hospital care can be concluded without litigation. This is dependent upon the NHS Redress Bill becoming law. In addition, a Compensation Bill has been introduced in the House of Lords; it considers the regulation of claims management and an aspect of the law of negligence (for further information, see Government Bills 2005/06, available online at www.commonsleader.gov.uk/output/Page944.asp).

Criminal accountability

Criminal law is concerned with intent, i.e. the person intended to commit the crime, or was reckless or negligent about the consequences of their actions. The nurse is answerable to a criminal court when there is an allegation that a crime has been committed, e.g. when a grossly negligent act by a nurse results in a patient’s death. In such a case the nurse could be charged with manslaughter (unlawful killing of a human being where premeditation is absent) and face imprisonment. It is this type of situation that could result in the nurse being answerable in all four arenas of accountability, i.e. dismissal, action by the NMC, a civil claim as well as the criminal charge. For example, a nurse administers a drug (already drawn up in a syringe and left at the patient’s bedside) without further checking or verification, and as a result the patient dies. The drug was for oral administration and led to the patient’s death when given intravenously.

Confidentiality

Confidential information is limited to those who use it and access it, and their use must be legitimate. Nurses are responsible for protecting the confidentiality and security of the patient’s/client’s personal and health information (see Ch. 7). However, nurses may be required to provide information, e.g. if required by law, order of the court, if it is in the public interest or when child protection is involved. As outlined in Confidentiality: NHS Code of Practice (DH 2003, p. 7):

Patient information is generally held under legal and ethical obligations of confidentiality. Information provided in confidence should not be used or disclosed in a form that might identify a patient without his or her consent, and

A duty of confidentiality arises when one person discloses information to another (e.g. patient to clinician) in circumstances where it is reasonable to expect that the information will be held in confidence. It –

•Must be included within NHS employment contracts as a specific requirement linked to disciplinary procedures.

All written and electronic information about patients/clients must be stored securely and access limited, e.g. by password, to the care team. Confidentiality applies to written and electronic records and verbal information (Box 6.8).

Idle chatter

Two nurses are discussing a patient/client in the canteen. At surrounding tables there are other members of staff, visitors, patients and outside contractors.

The nurses’ conversation, which is loud enough for others to hear, centres on a patient’s long history of mental health problems.

Student activities

[Resources: Data Protection Act 1998, the Human Rights Act 1998 (see pp. 150–151); The NMC code of professional conduct: standards for conduct, performance and ethics (NMC 2004, Clause 5, pp. 8–9)]

Patient/client records contain a great deal of information that might identify the person, including:

In addition, records also reveal information about the person’s health, lifestyle, current and past medical conditions and other confidential information.

Nurses should always ‘seek patients’ and clients’ wishes regarding the sharing of information with their family and others’ (NMC 2004, p. 9). When it is not possible to obtain permission, such as with children, some people with mental health problems and some people with learning disabilities, the nurse will need to discuss the situation with colleagues.

Breaches in confidentiality are potentially very harmful to patients/clients and families. Unauthorized or inadvertent disclosure can lead to disciplinary action by the employer or action by the regulatory body for professional misconduct (see p. 156).

Consent

Consent for care or treatment is a very important legal issue in nursing practice. It is vital that the person consents before any treatment, care, examination or assessment. It is the absolute right of an adult competent patientto give or withhold consent and in doing this prevents physical contact becoming a civil or criminal actionablewrong, namely trespass against the person, which includesassault and battery.

Assault is an attempt or offer of unlawful contact wherein the person is put in fear of violence or unlawful force. Battery is defined as unlawful contact or touching.

Very often a patient/client may give ‘implied’ consent, e.g. by rolling up their sleeve for blood pressure recording. However, patients still require information and explanation, such as the reason for carrying out the task, and the implications of it should be made clear to the patient/client. In some instances, such as prior to an injection, verbal consent is appropriate; however, in other instances written consent will be necessary, e.g. prior to an examination, invasive procedure or surgery.

There are three criteria needed to satisfy ‘valid’ consent: capacity, voluntarily, informed. A person must be able to understand the information to make a decision. They must be able to weigh up the information, and consider the consequence of having or not having the procedure. However, sometimes further information or explanation may be needed. A person may be competent to make some decisions even if they are not competent to make others. It is important to remember that obtaining consent is a continuing process, not a one-off event (DH 2001).

In order that consent is legally binding and compelling (or valid), the patient/client has to be given the information they require to make a conscientious decision, whereby they may accept or refuse treatment. They must not be forced, coerced or tricked into making the decision, nor should other professionals or institutional pressures or family or friends influence them. Consent is voluntary and the patient/client can change their mind at any time or withdraw their consent at any time.

What is sufficient information? The patient/client must always be informed of the risks involved in the proposed procedure so that they have an opportunity to avoid or reduce these risks. Thus the patient/client needs to understand in broad terms, in a language they can understand, the nature and purpose of the procedure. The person who will be carrying out the procedure usually obtains consent but registered nurses who have had special training may obtain consent in certain circumstances.

In all cases, patients/clients should be provided with sufficient information in order to make a decision. This should include the benefits and the risks, e.g. drug side effects. They should be informed of any alternative treatments or therapies. If the patient/client is not offered as much information as they need to make a decision, and in a form they can understand, then their consent may not be valid (DH 2001). In the case of Chester v Afshar [2004] 4 All ER 587 (HL) the surgeon had failed to tell a woman of a 1–2% inherent risk (i.e. a risk regardless of the surgeon’s skill) of an adverse result from the operation. The claimant conceded that she would have gone ahead with the operation but would have delayed her decision in order to give it more thought. The House of Lords judgement was that the surgeon had violated the patient’s right to make an informed decision. If the claimant had been fully informed of the risk, she would have still have had the same operation under identical conditions and performed by the same surgeon but on an occasion when the randomly occurring risk would probably not have happened (adapted from Tingle J, Wheat K, Readers in Law, Nottingham Trent University, Foster C, Barrister, London, 10 February 2006, personal electronic mail).

Consent in children

Children should always be consulted (subject to age and understanding) and kept informed about what is planned. The Children Act 1989 ensures children’s wishes and feelings are taken into account.

The age of consent to medical treatment varies across the UK:

… In relation to obtaining consent for a child, the involvement of those with parental responsibility in the consent procedure is usually necessary, but will depend on the age and understanding of the child. If the child is under the age of 16 in England and Wales, 12 in Scotland and 17 in Northern Ireland, you must be aware of legislation and local protocols relating to consent.

There are three key points in relation to age of children that need to be emphasized. They are:

Maturity is a key factor and older children can have the maturity and capacity to make important decisions about their own medical treatment whereas others may not have reached that level of maturity at the same age. It is imperative that professionals assess maturity and the individual’s capacity to understand issues surrounding the proposed treatment and risks.

An important ruling regarding the competence of a child to consent to treatment is the Gillick competence (Box 6.9). In Gillick v West Norfolk and Wisbech Area Health Authority [1985] 3 All ER 402 (HL) the House of Lords ruled that a child under 16 years of age can give legally effective consent to medical treatment if they have achieved ‘sufficient maturity and intelligence to enable him to understand fully what is proposed’. The test laid down in Gillick requires that the health professional must assess whether the particular child is competent to consent to a particular treatment (McHale & Tingle 2001).

Gillick competence: Fraser guidelines

It is considered good practice for doctors and other health professionals to follow the criteria outlined by Lord Fraser in 1985, in the House of Lords’ ruling in the case of Gillick v West Norfolk and Wisbech Health Authority. The Fraser guidelines (DH 2004, p. 4) are:

Young people under the age of 16 often seek sexual health advice from a school nurse. This may include requests for emergency contraception or information about abortion.

Student activity

Ask a school nurse how they assess a young person’s competence before supplying/prescribing emergency contraception.

[Resource: Department of Health (DH) 2004 Best practice guidance for doctors and other health professionals on the provision of advice and treatment to young people under 16 on contraception, sexual and reproductive health – www.dh.gov.uk/assetRoot/04/08/69/14/04086914.pdf Available September 2006]

Two important considerations – the child’s best interests and whether they have the mental capacity to exercise their rights responsibly – restrict children’s rights. Striking a balance between these two principles depends on the individual child and the situation.

In caring for children, the main priority for the nurse is to obtain valid consent from the appropriate person, i.e.the child or the person with parental responsibility. Usuallythis is the mother or father of very young children. However, this may not be possible, if for example a child is injured at school, in which case consent may be obtained from the teacher or child minder. The teacher would have the right to do what is ‘reasonable in all circumstances’ in safeguarding or promoting the child’s welfare (McHale & Tingle 2001). This is further complicated by whether the treatment is in the child’s best interests. Parental consent does not cover whatever treatment the parents believe to be in their child’s best interests and any treatment is ultimately dependent upon the healthcare professional’s assessment of what is appropriate for the child.

The law makes a distinction between a child’s right to consent to treatment and to refuse treatment. Refusal of treatment is a complex area. According to McHale and Tingle (2001, p. 117):

At present, even if a Gillick competent child refuses medical treatment it appears that his or her parents may override the refusal. Even so, the court in Re W ([1992] 3 WLR 758) suggested that before a major surgical procedure is undertaken on a child against the child’s will, it will be desirable for the issue to be referred to the court. The court will then determine what is in the child’s best interests, taking into account the child’s expressed wishes and the strength of the child’s beliefs.

Parents and/or children may refuse consent for treatment. For example, a parent refuses consent and the child is unable due to critical illness. Consideration of the child’s best interests is vital. In this instance healthcare professionals should hesitate before giving treatment and consider the potential outcomes of giving the treatment or of withholding treatment. Often it is the urgency of the child’s condition that dictates justification for treatment without parental consent. For example, if the child is bleeding to death, then it is justifiable to treat, even in the face of parental opposition (McHale & Tingle 2001). In some cases the courts make the decision.

In other circumstances, refusal may be from both theparent and child, e.g. where the child and family are refusing a blood transfusion according to the teaching of their religion (Jehovah’s Witness). In such a situ-ation the outcomes and consequence of refusal must be made clear to both the child and parents. The dilemma for health professionals is if that refusal could lead to the death of that child. Authorization for treatment would be dependent upon the court’s decision.

Consent – people with learning disability or fluctuating mental capacity

There are situations where capacity may be in doubt. For example, a patient/client may not understand what they have been told or they may appear confused. The nurse may need to assess if the patient/client is capable of making a particular decision. This can be especially difficult in some patients/clients who have a learning disability or suffer from fluctuating mental capacity.

In the case of Re C [1994] All ER 819 the court upheld the right of a man with serious mental health problems to prevent amputation of his gangrenous foot in the future without his written consent. Thorpe. J. proposed a three-question test to establish if the patient/client possessed capacity. The three questions asked were:

A difficulty with the test used in Re C arises because capacity is dependent upon the information given (Grubb 1994). For example, a nurse provides a patient/client withcomplex information about a procedure requiring consent. If the information includes medical terms, the patientmay not understand the information given. However, if the patient/client is given a clear, simple explanation about the same procedure, in non-technical language that they can understand, then they may have possessed the necessary capacity to consent.

Nurses must carefully consider what they say and how it is said. The views of the patient/client and their relatives/carers are equally important in assessing the person’s capacity to understand and give consent. In addition, awareness that the patient may have the capacity to make one decision, but at the same time is incapable of making another, has led to the conclusion that such a test for capacity should be decision specific.

Providing care for someone with a learning disability may present some difficulties (Box 6.10).

The ‘Bournewood’ case

A man, aged 40 years, was unable to speak and had limited understanding. He had a history of self-harming behaviour and frequent outbursts of agitation. For over 30 years the man was cared for in an NHS hospital.

He was discharged on a trial basis but after an incident where he became agitated with self-harming behaviour he was detained in hospital under the MHA 1983. Because the man was compliant and did not resist admission, he was admitted as an informal patient (see p. 151) in his own best interests under the common law principle of necessity.

Legal action was commenced to secure his discharge from hospital. This was unsuccessful in the High Court but later the Court of Appeal held that the man had been unlawfully detained, and that because of the MHA 1983 the common law principle of necessity could not be used to detain someone for treatment for a mental health disorder. The man was formally detained under the MHA 1983 and later discharged.

The House of Lords overturned the Court of Appeal’s judgment and the case was taken to the European Court of Human Rights. This Court found that there had been a violation of Articles 5(1) Right to Liberty and 5(4) Right to Security.

Student activities

[Resource: Department of Health 2005 ‘Bournewood’ consultation. The approach to be taken in response to the judgment of the European Court of Human Rights in the ‘Bournewood’ case – www.dh.gov.uk Available July 2006]

The case described in Box 6.10 has important implications for the organizations and the people involved in the treatment and care of individuals who lack capacity to consent to treatment. The man’s rights had not been breached simply because he was admitted to hospital in his best interests rather than under the MHA 1983, but because procedural safeguards surrounding his admission had failed to protect him.

The recommendations from this case included proper assessments of those incapacitated and unable to make such decisions, alternatives to hospital or residential admis-sions, and that appropriate information be given to patients, family and carers.

The Mental Capacity Act

The Mental Capacity Act 2005 provides a statutory framework for decision-making on behalf of adults (see Table 6.1), thus protecting vulnerable adults and their carers, and professionals. In Scotland, the Adults with Incapacity (Scotland) Act 2000 fulfils a similar function.

The Mental Capacity Act 2005 has a long history, which started with a Law Commission Report (number 231) (Mental Incapacity) in 1995, followed by a lengthy consultation, a draft Mental Incapacity Bill in 2003 and eventually a renamed Mental Capacity Bill in 2004, which became law in 2005.

The Act applies to adults who lose mental capacity, e.g. due to dementia in later life and to people who lack mental capacity due to conditions present at birth, e.g. some forms of learning disability. The Act governs decisions about welfare and health, financial matters and participation in research. It also includes a new scheme for lasting power of attorney, which may include health-related decisions. It makes clear who can take decisions in which situations and how they should go about this. It starts from the fundamental premise that a person has capacity and that all practical steps must be taken to help the person make a decision.

Right to refuse treatment

A competent adult patient has an absolute right to refuse or withdraw from treatment or change their mind about treatment. Their decision must be respected, even if it results in death; for example, the case of Ms B v An NHS Trust [2002] 2 All ER 449 in which Dame Elizabeth Butler-Sloss made the judgement that Ms B had the necessary mental capacity to refuse treatment, which in this case meant switching off the ventilator and allowing her to die (Box 6.11).

Refusal of medical treatment

In the case of Ms B v An NHS Trust it was clear to all concerned that she would die once treatment ceased. The implications for other refusals of treatment are not always so clear-cut.

Student activities

[Resource: BBC 22 March 2002 Q & A: Right-to-die decision – http://news.bbc.co.uk/1/hi/health/1887286.stm Available July 2006]

One way in which patients/clients can maintain control or choice in decisions about their health or life or circumstance (when their mental capacity is altered) is through the use of advance directives (referred to as an advance decision to refuse treatment in the Mental Capacity Act 2005).

Advance directive

An advance directive is a legally binding statement prepared in advance by a competent adult before they lose the mental capacity to make decisions. It allows the person to give or withhold consent at a point where their lack of capacity would normally exclude them (Tingle & Cribb 2003). An advance directive specifies the person’s wish to refuse some or all medical treatment and the circumstances when the refusal would apply (Box 6.12).

Advance directives

There is sometimes confusion about what an advance directive can do and the criteria that must be met for it to be valid.

Student activities

Visit the Age Concern website below and find answers to the following questions:

[Resource: Age Concern 2005 Advance statements, advance directives and living wills – www.ageconcern.org.uk/AgeConcern/Documents/IS5_1005.pdf]

Advance directives must be clearly drafted, with full understanding of their implications, and cover circumstances which may occur (Tingle & Cribb 2003). They are subject to restrictive interpretation:

An advance directive can provide a useful guide as towhat treatment should not be given and in what circumstances. It is vital, however, to note that such a documentdoes not authorize an action that is unlawful, such as euthanasia. The Mental Capacity Act 2005 sets out rules about advance directives to refuse treatment (see p. 160) and will become the legal authority for advance directives in 2007. Many uncertainties surround their use, e.g. a person’s circumstances can change after the advance directive has been written. In some cases, years may pass before it is revisited (often at the time of illness/injury) and thus the validity of competence at the time of its writing may be questioned. Lack of specificity can present problems for healthcare professionals. The provision of lasting power of attorney may offer some resolutions (see ‘The Mental Capacity Act 2005’, p. 160).

End-of-life issues

End-of-life issues – including withholding/withdrawing treatment and ‘do not attempt resuscitation’ (DNAR), also called ‘do not resuscitate’ (DNR), orders – present healthcare professionals with legal, ethical and professional issues to resolve. Although detailed coverage is beyond the scope of this chapter, it is important that nurses are aware of the issues (see also Chs 7, 12, 17). While it is likely that nursing students will encounter some of these situations, they will not be directly involved in decision-making but should take the opportunity to observe and discuss the issues that arise with their mentor. Box 6.13 provides suggestions for sources of information about some of these issues.

Box 6.13 End-of-life issues, information sources

Key words and phrases for literature searching

| Civil law | Duty of care |

| Confidentiality | Legislation |

| Consent | Liability |

| Criminal law | Negligence |

| Department of Health | www.dh.gov.uk |

| Available July 2006 | |

| Health and Safety Executive | www.hse.gov.uk |

| Available July 2006 | |

| Law Commission | www.lawcom.gov.uk |

| Available July 2006 | |

| Nursing and Midwifery Council | www.nmc-uk.org |

| Available July 2006 | |

| Office of Public Sector Information source for legislation throughout the UK | www.opsi.gov.uk |

| Available July 2006 |

Department of Health (DH). Mental Health Act. London: HMSO, 1983.

Department of Health (DH) 2001. 12 Key points on consent: the law in England. London: HMSO, 2001.

Department of Health (DH). 2003 Confiden-tiality: NHS code of practice. Online: www.dh.gov.uk/PublicationsAndStatistics/Publications/PublicationsPolicyAndGuidance/PublicationsPolicyAndGuidanceArticle/fs/en?CONTENT_ID54069253&chk5jftKB%2B.

Dimond B. Legal aspects of nursing, 2nd edn. London: Prentice Hall, 1995.

Grubb A. cited in McHale J, Tingle J 2001 Law and nursing, 2nd edn. Edinburgh: Butterworth-Heinemann, 1994.

Information Commissioner. 2005 Data Protection Act Factsheet. Online: www.informationcommissioner.gov.uk/eventual.aspx?id534.

McHale J, Gallagher A. Nursing and human rights. Edinburgh: Butterworth-Heinemann, 2004.

McHale J, Tingle J. Law and nursing, 2nd edn. Edinburgh: Butterworth-Heinemann, 2001.

NHSLA. 2005 Key facts. Online: www.nhsla.com/home.htm.

NPSA. 2005 Annual review 04/05. Online: www.npsa.nhs.uk/web/display?contentId54331.

Nursing and Midwifery Council (NMC). Code of professional conduct: standards for conduct, performance and ethics. London: NMC, 2004.

Nursing and Midwifery Council (NMC). 2005a Students – guidance on clinical experience. Online. Available: http://www.nmc-uk.org.

Nursing and Midwifery Council (NMC). Guidelines for records and record keeping. London: NMC, 2005.

The Mental Health (Care and Treatment) (Scotland) Act. 2003. Online: http://www.scotland.gov.uk/Publications/2003/11/18547/29201. Available July 2006.

Tingle J, Cribb A. Nursing law and ethics, 2nd edn. Oxford: Blackwell, 2003.

Butterworth C. Ongoing consent to care for older people in care homes. Nursing Standard. 2005;19(20):40-45.

Children’s Legal Centre. Working with young people: legal responsibility and liability, 6th edn. Colchester: Children’s Legal Centre, 2005.

Dimond B. Legal aspects of nursing, 4th edn. Harlow: Pearson, 2005.

Hutchinson C. Addressing issues related to adult patients who lack the capacity to give consent. Nursing Standard. 2005;16(19):47-53.

Martin J. Clinical negligence and patient compensation. Nursing Standard. 2005;19(25):35-39.

McInroy A. Blood transfusions and Jehovah’s Witnesses: the legal and ethical issues. British Journal of Nursing. 2005;14(5):270-274.

Pearce L. Good counsel. Nursing Standard. 2005;19(24):17-18.

REFLECTIVE PRACTICE

REFLECTIVE PRACTICE CRITICAL THINKING

CRITICAL THINKING