Chapter 19 Promoting hydration and nutrition

Introduction

Ensuring that clients and patients have sufficient fluids and nutrition that meets their needs is a basic, but vital role of the nurse. Healthy body function, recovery from illness and eventually life itself depend on being able to access fluids and nutrients. Nurses not only help people to eat and drink during illness but they also have an important role in educating people about eating and drinking for optimum health. Although families, health care assistants (HCAs) and students undertake considerable ‘hands on’ care, the registered nurse (RN) remains accountable for all nursing interventions (see Ch. 7). The nurse works within a multidisciplinary team (MDT) that includes, amongst others, dietitians, specialist nutrition and intravenous therapy nurses and catering staff, to promote hydration and nutrition.

Inadequate or inappropriate fluid and nutrient intake impedes recovery from illness and surgery, lengthens hospital stay and can lead to complications that include delayed wound healing, pressure ulcers, weight loss, low mood, infection, dehydration and poor oral hygiene.

The importance of providing oral nutrition is emphasized by it forming one of the original Essence of Care best practice statements (DH 2001).

Education about and help to eat a healthy balanced diet is imperative given the high prevalence of overweight and obese children and adults in the UK. The House of Commons Select Committee (2004) report that two-thirds of the population in England is overweight or obese.

This chapter is in two parts: maintaining fluid, electrolyte and acid–base balance, and nutrition. However, it is important to understand that all of these are closely linked and that none can ensure well-being without the others.

Skilled promotion of hydration and nutrition is an important nursing role that really can ‘make a difference’ to the well-being of people in their care.

Maintaining fluid, electrolyte and acid–base balance

This part of the chapter outlines the maintenance of fluid, electrolyte and acid–base balance, some common disorders and investigations. Nursing interventions such as assessment of hydration, helping with drinking and the principles of intravenous infusions are covered in some depth.

The amount of water and electrolytes, e.g. sodium, potassium, in the body compartments and acid–base balance are controlled by interdependent mechanisms that keep levels fairly constant within narrow limits. Normal body function depends on homeostasis, i.e. maintaining water, electrolyte levels and acid–base balance in the internal environment within the normal range. Therefore, dynamic homeostatic mechanisms are required to respond to continually changing conditions within the body.

Body fluids and fluid compartments

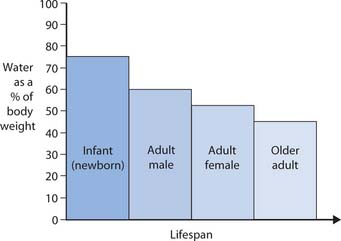

The amount of water as a percentage of body weight decreases with age (Fig. 19.1). For example, a newborn baby has around 75% water whereas an average adult male has around 60% and an older adult between 45 and 50%. The amount of body fat and gender also influence water content. Fat (adipose tissue) contains less water than muscle tissue. Body water is lower in older adults because muscle tissue is replaced by fat; people with obesity and women, who generally have more fat than men, also have less body water.

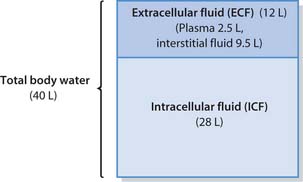

Body water is distributed between two fluid compartments:

In adults, the split is approximately two-thirds ICF to one-third ECF (Fig. 19.2). The distribution of fluid in infants and children less than 2 years of age is characterized by more body water in the ECF. The fluid distribution and the increased rate at which ECF is exchanged means that there is very little fluid reserve, hence there is an increased risk of dehydration if an infant or small child loses fluid (Huband & Trigg 2000).

Fig. 19.2 Distribution of body water in a 70 kg adult male

(reproduced with permission from Brooker & Nicol 2003)

The body surface area also differs in children and infants who have proportionally greater surface areas than adults. Therefore they lose more water through the skin, which has important implications for fluid balance and intravenous (i.v.) fluid therapy (see p. 545). The immature kidneys of infants and small children cannot excrete or conserve the electrolyte sodium, or produce concentrated or dilute urine (Wong et al 1999). In addition, they have a higher metabolic rate that produces more waste products for excretion in the urine. Conditions that increase metabolic rate also increase heat production and hence the amount of water loss through the skin (Wong et al 1999).

Electrolytes

Electrolytes are substances such as sodium chloride (described in chemical notation as NaCl), which, when dissolved in water, dissociate into electrically charged particles called ions that conduct electricity. Some ions have a positive charge, e.g. sodium (Na1), and others are negatively charged, e.g. chloride (Cl2). In body fluids the main electrolytes are sodium, potassium, calcium and magnesium with a positive charge, and bicarbonate, chloride and phosphate that are negatively charged. The ECF and ICF have different electrolyte compositions; sodium is mainly in the ECF whereas most potassium is in the ICF. Table 19.1 shows the normal range for serum electrolyte levels in adults.

Table 19.1 Serum electrolytes – normal reference values (adults)

| Electrolyte (chemical notation) | Reference range (serum) |

|---|---|

| Sodium (Na+) | 135–143mmol/L |

| Potassium (K+) | 3.6–5.0mmol/L |

| Calcium (Ca2+) | 2.1–2.6mmol |

| Magnesium (Mg2+) | 0.75–1.0mmol/L |

| Chloride (Cl−) | 97–106mmol/L |

| Phosphate (PO42−) | 0.8–1.4mmol/L |

| Bicarbonate (HCO3−) | 22–28mmol/L |

Note that the amount of urea (waste product of protein metabolism, normal range 2.5–6.4mmol/L) is usually measured along with serum electrolytes. Note that normal ranges may vary slightly on a local basis.

Movement of water and electrolytes

Water and electrolytes and other substances continually move between the ECF and ICF in order to:

This movement occurs through a number of processes, including osmosis, diffusion, filtration and active transport.

Osmosis

Osmosis is the movement of water through a semi-permeable membrane. Pores in the membrane allow the movement of water molecules in either direction. Water moves when there is a difference in its concentration on either side of the membrane. The direction of movement is from high water to low water concentration. This means that water will move from a weak solution to a stronger, more concentrated solution until equilibrium is reached, i.e. the water concentrations are the same on either side of the membrane. Osmosis occurs when equilibrium cannot be achieved by the movement of electrolytes or sugars (solutes) across the semi-permeable membrane.

The force required to oppose the movement of water by osmosis is known as the osmotic pressure; this increases with the concentration difference on either side of the membrane. The concentration of particles that contribute to the osmotic pressure in a litre of fluid is termed the osmolality of a solution. The movement of water stops when the opposing pressures (i.e. concentrations) on either side of the membrane are the same. The solutions are then described as being isotonic. In the body, an isotonic solution has the same osmolality as plasma. A solution with a higher osmolality than plasma is described as hypertonic; one with a lower osmolality to plasma is hypotonic. Osmosis is vital in maintaining the correct water distribution within the fluid compartments.

Diffusion

Diffusion involves the movement of gases and solutes from an area of high concentration to an area of lower concentration, i.e. down a concentration gradient. In the body, diffusion down a concentration gradient takes place within cells or body fluids and also across semi-permeable membranes. The latter allow small particles topass through but hold back larger particles, e.g. proteins.

Diffusion is described as passive because it does not use chemical energy (adenosine triphosphate [ATP]). The end result of diffusion is equal concentrations on both sides of the membrane, i.e. equilibrium. Diffusion is important for the movement of O2, carbon dioxide (CO2), electrolytes, nutrients, hormones and waste products such as urea.

Filtration

The passive process of filtration provides another means by which the fluid compartments and the concentration of substances within body fluids are maintained; again there is a gradient difference either side of the membrane, but this time it is pressure rather than concentration. The pressure that forces water and small molecules through membrane pores is known as the hydrostatic (fluid) pressure. Filtration is important in the formation of tissue fluid and urine (see Ch. 20).

Active transport

Active transport is a process requiring chemical energy (ATP) to move substances:

Substances transported in this way include nutrients and electrolytes, e.g. the sodium–potassium exchange pump in cell membranes where sodium ions (mainly in the ECF) are pumped out of the cell and potassium ions (mainly in the ICF) are pumped into the cell against their concentration gradients.

Acid–base balance

The pH (hydrogen ion concentration or the acidity) of blood and other body fluids must remain within a narrow range for normal cell function. For example, the normal range for the pH of ECF is 7.35–7.45. Small deviations outside this range are associated with serious physiological disruption because pH is a logarithmic scale and a change of 1 represents a 10-fold change in hydrogen ion concentration.

Acids are ingested on a daily basis and metab-olic processes continuously produce acidic substances including CO2 (which, when dissolved, increases the acidity of a solution), lactic acid and ketoacids. Various interdependent homeostatic mechanisms function to maintain acid–base balance. These are:

If these homeostatic mechanisms fail, acid–base balance is disrupted. When the pH of arterial blood rises above 7.45, i.e. becomes more alkaline, this is known as alkalaemia. The process leading to low levels of acid (excess of alkali) is termed alkalosis. When the pH of arterial blood falls below 7.35 this is known as acidaemia. Note – the blood is still alkaline but the pH is closer to the acid range. The process that results in the excess acid is termed acidosis.

Homeostatic mechanisms attempt to restore normal blood pH by either excreting more or less CO2 from the lungs or by changing the amount of H1 or HCO32 excreted in the urine. Acid–base imbalances, which are often associated with fluid or electrolyte imbalances (see p. 535), can be life threatening. Disorders of acid–base balance are outlined in Box 19.1.

Box 19.1 Disorders of acid–base balance

The acid–base disorders alkalosis and acidosis can have either a respiratory or a metabolic cause. Seriously ill patients may develop a mixed disorder.

Alkalosis

Acidosis

[For further information, see Waugh (2003)]

Normal fluid and electrolyte balance

The kidneys regulate fluid and electrolyte balance in response to hormone secretion (see below). Healthy people take in most fluid by drinking but there is water in food, e.g. soup, fruit and ice cream, and chemical processes in the body also produce water (metabolic water). Electrolytes are obtained from food and fluids, e.g. sodium from the salt added to processed foods. Fluids and electrolytes are excreted from the body in urine, faeces, sweat, through insensible perspiration and during respiration. Table 19.2 shows average volumes for adults.

Table 19.2 Average water balance over 24 hours in adults

| Input (mL) | Output (mL) |

|---|---|

| Drinks 1700 | Urine 1500 |

| Fluid obtained from food 1000 | Faeces 100 |

| Metabolic water 300 | During respiration 500 |

| Skin (insensible loss and sweat) 900 in health | |

| Total 3000 | Total 3000 |

Factors that regulate normal fluid and electrolyte balance

Hormones such as aldosterone and antidiuretic hormone (ADH) are essential in maintaining fluid and electrolyte homeostasis by their actions on the kidneys (see Ch. 20). Also very important in the regulation of fluid balance is the sensation of thirst. If fluid is lost or intake is inadequate a person feels thirsty and usually remedies the situation by having a drink. However, certain groups of people are unable to respond to thirst: babies, small children, people with mobility problems, unconscious patients, people with a severe learning disability or dementia and older adults (who may not experience thirst) are all at risk of fluid depletion (Box 19.2).

Responding to thirst

Think about people you have met during placements.

Student activities

Common disorders of fluid and electrolyte balance

Disorders of fluid and electrolyte balance can cause serious and sometimes life-threatening effects.

Common disorders of fluid balance

Disorders of fluid balance can be divided into two main types:

An outline of fluid balance disorders is provided in Box 19.3.

Box 19.3 Common disorders of fluid balance

Isotonic imbalances

Osmolar imbalances

Electrolyte imbalances

Disorders of electrolyte balance involve either increases or decreases outside the normal range. Many factors can affect electrolyte levels (Box 19.4).

Factors that can affect electrolyte levels

The next time you are helping to care for a person who has had their electrolytes measured, ask if you can look at the results from the laboratory.

Frequently more that one electrolyte is affected and is accompanied by a fluid imbalance; sometimes there is also loss of acid–base balance. Box 19.5 outlines some important electrolyte imbalances.

Box 19.5 Common causes of abnormal blood electrolyte levels

Hypernatraemia

Increased blood sodium concentration, caused by excessive loss of water without electrolytes owing to polyuria (increased urinary volume), high salt intake, excessive sweating or inadequate water intake.

Hyponatraemia

Decreased blood sodium concentration, caused by vomiting, diarrhoea, sweating and burns; diuretics, heart failure, kidney disease and diabetes mellitus, or a failure to excrete water or excess intake.

Factors that can lead to fluid and/or electrolyte imbalance

Many physical, psychological and social factors can lead to imbalances in body fluids and electrolytes. The nurse must be able to identify and minimize the impact of factors that increase the risk of people developing problems. These factors include those that prevent a person responding to thirst (see p. 534) as well as the following.

Age

People at the extremes of age are at increased risk of fluid and electrolyte imbalance. In infants and small children this is because of the distribution of fluid in the ECF and ICF, their immature kidneys, greater body surface area and higher metabolic rate (see p. 532). In older adults the risk of imbalances is increased by the reduced percentage of body water, declining kidney function and inability to access fluids or respond to thirst (see p. 534).

Fasting

People who are having investigations or procedures that require a general anaesthetic can develop fluid depletion if they are fasted for unnecessarily lengthy periods (see Ch. 24).

During the religious festival of Ramadan all healthy Muslims over the age of 12 years are required to fast between dawn and sunset (Box 19.6).

Fasting during Ramadan

Although a person who is ill is not required to fast, many devout Muslims want to fast for all or at least part of Ramadan. This observance of faith may be particularly important for the person who is terminally ill or has a life-threatening condition (see Ch. 12).

Muslims who are unwell need special arrangements if they decide to fast during Ramadan. It is important that fluids and a meal are provided before dawn and soon after sunset. The person will also need water and a bowl so that they can rinse their mouth before prayers.

Fluid and electrolyte loss

Vomiting and diarrhoea and excessive sweating, such as during heavy work or exercise, lead to problems with fluid and electrolyte balance. In addition, hot weather leads to an increased fluid requirement, especially for those exercising strenuously.

Alcohol and caffeine drinks

Alcohol, tea, coffee, cocoa and ‘cola’ drinks increase urin-ary output (diuresis) and cause fluid depletion.

High level of dependency

People with some physical disabilities and/or a severe learning disability may be completely dependent on others for their fluid intake, as they are unable to ask for a drink or make themselves a drink. Some people such as those with cerebral palsy also have problems with chewing, swallowing (see below), muscle tone and posture and the reflexes that protect the airway.

Mental health problems

People experiencing severe mental distress may be unable to maintain an adequate fluid intake because their mood is so profoundly depressed, or they may be experiencing serious manifestations, such as hallucinations, which pervade all aspects of life to the exclusion of self-maintenance activities. Drugs used for some forms of mental distress can lead to fluid and electrolyte imbalances, e.g. lithium carbonate.

People with dementia or confusion may not remember to drink during the day or will have forgotten how to prepare drinks. Lack of fluid worsens confusion and a vicious circle of increasingly severe fluid depletion and worsening confusion ensues.

Immobility and lack of manual dexterity

Older people and those with conditions such as severe arthritis, or following a stroke, may be unable to prepare drinks safely or to carry them from the kitchen. Dealing with hot drinks can be hazardous, particularly when people find it difficult to hold a cup or mug due severe shaking or deformity of the hands.

Swallowing problems (dysphagia)

Swallowing problems are very common after a stroke and the risk of choking or inhalation of fluids or food into the respiratory tract is present. It is essential that oral fluid and food be withheld until a speech and language therapist (SLT) or specially trained nurse carries out a full assessment. The stages of swallowing are outlined on page 550 and more details about swallowing assessment can be found in Further reading (e.g. Brooker & Nicol 2003).

Fear of incontinence

People may restrict their fluids in an effort to prevent nocturia (passing urine at night) or incontinence (see Ch. 20). Those who limit fluids before bedtime should be encouraged to compensate by increasing intake at other times of the day (Morrison 2000).

Drugs

Drugs – including diuretics, e.g. furosemide (frusemide) – can lead to fluid depletion and loss of electrolytes, especially potassium.

Breathlessness (dyspnoea)

Breathlessness can lead to fluid depletion because insens-ible water loss increases during mouth breathing. The administration of oxygen without humidification also worsens oral drying. A person with severe breathlessness will have little energy for drinking and will be unable to access fluids.

Serious organ disorders

Heart, liver and kidney failure all lead to severe fluid and electrolyte retention, e.g. sodium and potassium. It may be necessary to restrict the intake of fluids (p. 543) and foods containing particular electrolytes such as sodium (see p. 556).

Lack of access to clean water

Many people in developing countries and those affected by natural disasters or wars do not have clean water piped to individual homes. Often, people spend many hours a day collecting water, or have no alternative to drinking from dirty sources such as rivers contaminated by untreated sewage.

Nursing interventions that aim to help people obtain sufficient fluids are discussed below (pp. 540–543).

Nursing interventions: promoting and maintaining hydration

Although the Essence of Care best practice statement ‘Patients receive the care and assistance they require with eating and drinking’ (NHS Modernisation Agency 2003, p. 1) appears to state the obvious, this does not always happen. This part of the chapter covers the nursing assessment and some investigations used to evaluate fluid and electrolyte status. It also describes how nurses can help people to drink sufficient fluids. Other interventions covered include caring for people with fluid imbalances and those with nausea and vomiting.

Most people maintain hydration and fluid balance with oral fluids. This is the preferred route as it maintains normality, is non-invasive and has fewer complications. Where this is not possible, e.g. due to severe vomiting, unconsciousness or swallowing problems, other ways of providing fluid are needed. Box 19.7 outlines other routes and some are discussed more fully below (pp. 543–549).

Box 19.7 Routes for the administration of fluid

Enteral fluids

People who are unable drink sufficient fluids or have swallowing problems, but who have a functioning GI tract, can have their fluid needs met by the enteral route. This may be through a:

The enteral route is usually used to provide both nutrients and fluids and is discussed on page 562.

Subcutaneous fluids

Fluid infused subcutaneously (see p. 543) is known as hypodermoclysis and is increasingly used to provide treatment for mild to moderate dehydration.

Rectal fluids

Fluid infused into the rectum for absorption is known as proctoclysis. The fluid, e.g. tap water or normal saline (sodium chloride 0.9%), is infused and slowly absorbed into the circulation. Proctoclysis is a safe, effective and low cost technique for maintaining hydration in terminally ill patients (Bruera et al 1998).

Intravenous fluids

Sterile intravenous fluids (see p. 545) are infused into a vein to maintain fluid, electrolyte and acid–base balance or to correct imbalances, administer drugs and provide nutrients (see also ‘Parenteral nutrition’, p. 565).

Intraosseous fluids

The intraosseous route involves the introduction of fluids into the marrow (medullary) cavity of a long bone, e.g. the tibia. It is used for children in some emergency situations (for more information, see Trigg and Mohammed (2006) in Further reading).

Assessing hydration

The nursing assessment of hydration is a vital component of holistic assessment, which includes careful observation. It is important to consider all aspects of the person’s life such as their normal fluid and food intake and the type of drinks they normally prefer. The nurse needs to be aware of physical, social or psychological factors that may disrupt fluid and electrolyte balance to identify those people who are at risk of potential or actual problems. The nurse documents the findings from this assessment in the nursing records and ensures that any abnormal findings are reported immediately to the RN. Box 19.8 outlines some investigations used to assess hydration.

Skin

Normally when skin is pinched and released it returns at once to its normal position, as the elastic tissue recoils. This feature is termed turgor. People who have a fluid volume deficit may have reduced skin turgor and the pinched up portion remains raised for longer. Skin turgor is not always reliable in the assessment of older people who have less elastic tissue or in people who have recently lost weight. The skin may appear dry.

The presence of oedema (see p. 535) can indicate fluid volume excess with accumulation of fluid in the interstitial spaces. Generalized oedema affects dependent parts of the body, the feet and ankles when standing or sitting and the sacral area in people confined to bed. On waking, some people may have puffiness around the eyes (periorbital oedema) because they have been lying flat. When oedematous tissue is compressed with a finger and stays indented, this is termed ‘pitting oedema’.

Fontanelles

Assessment of the anterior fontanelle (often called the ‘soft spot’ by parents) in the skull is a guide to hydration status in babies. The fontanelles are membranous spaces present between the skull bones in newborn babies. The diamond-shaped anterior fontanelle is located between the frontal and two parietal bones and closes up during the second year of life. A triangular posterior fontanelle is situated at the junction of the occipital and two parietal bones. This closes within weeks of birth.

The anterior fontanelle can be observed and gently felt with the flat part of a finger. In healthy, well-hydrated babies the fontanelle is level with the skull bones. A sunken fontanelle can indicate fluid volume deficit while a bulging fontanelle may suggest fluid volume excess, or it can be due to increased pressure inside the skull (raised intracranial pressure).

Weight

Accurate daily weight (see Ch. 14) can give a good indication of the amount of fluid lost or gained, especially oedema.

Sunken eyes

Sunken eyes can indicate a moderate to severe fluid volume deficit. It occurs because interstitial fluid is lost from the periorbital tissue.

Mouth

The condition of the oral mucosa, which is usually pink and moist, is a good indicator of hydration status (see Ch. 16). Fluid depletion leads to a dry mouth, coated tongue and viscous (thick) saliva. Thirst is an important regulator of fluid balance (see p. 534) and people with fluid depletion will usually say that they are thirsty. It is important to remember that a dry mouth may have other causes, e.g. oxygen therapy, mouth breathing and some drugs.

Behaviour

People’s behaviour can give valuable clues about hydration. Lethargy, anxiety or confusion may occur in fluid depletion and acid–base imbalance. Babies and small children may exhibit irritability. Some babies are quiet and show little interest in their surroundings or a favourite toy or game.

Bowel function (see Ch. 21)

Constipation can be caused by fluid volume deficit or dehydration. Severe fluid, electrolyte and acid–base imbalance can result from severe or prolonged diarrhoea.

Urine output and specific gravity (see Ch. (20)

The volume and colour of urine are important indicators of hydration. Small volumes (oliguria) and dark concentrated urine with a high specific gravity (SG .1.030) are features of fluid volume deficit. Infants and toddlers have fewer wet nappies than normal. Concentrated urine may have a stronger odour than usual. Further discussion about fluid balance charts is provided below.

Blood pressure

A fall in blood pressure (BP) accompanies fluid volumedeficit. In severe situations the person will have a low BP (hypotension) while lying down. However, in milder cases the fluid volume deficit may only be apparent because of a marked decrease in BP upon standing up from the sitting position (postural hypotension). An increasing BP may be a feature of fluid overload such as during i.v. fluid therapy (see p. 549).

Pulse

An increase in pulse rate (tachycardia) occurs in fluid volume deficit because there is less fluid in the vascular system (hypovolaemia). Fluid volume excess normally also causes an increase in pulse rate (Carroll 2000).

Respiration

The respiratory rate, effort and depth can change in response to fluid, electrolyte and acid–base imbalance. For example, a person with fluid volume excess can develop pulmonary oedema (see p. 535 and Ch. 19), which causes difficulty in breathing (dyspnoea) and a cough with frothy sputum.

Skin temperature

Cool extremities may indicate a decrease in intravascular volume but there are also many other factors that influence skin temperature (see Ch. 14).

Central venous pressure

Central venous pressure (CVP) estimates the pressure of blood in the right atrium of the heart. CVP is used in ser-iously ill patients to assess hydration status and inform fluid replacement therapy. It is always interpreted in conjunction with other observations such as pulse, BP, respiration and urine output (for more information, see Further reading, e.g. Metheny 1996).

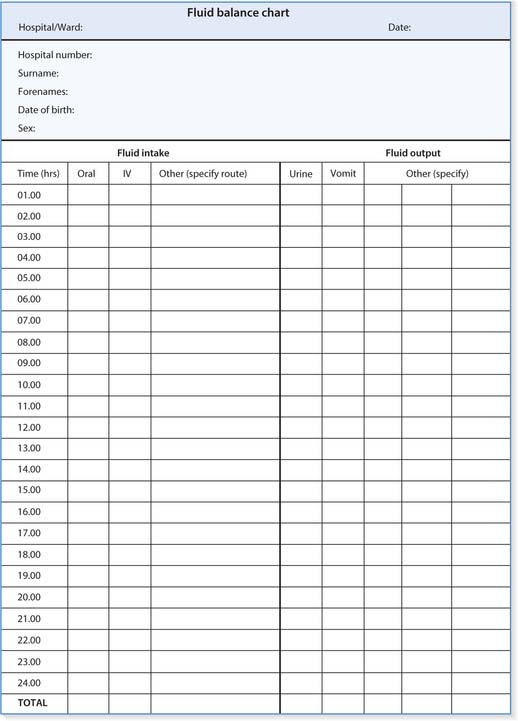

Fluid balance charts

Fluid balance charts are also known as fluid intake and output charts, or sometimes just fluid charts. They are used to record all fluid intakes and outputs over a 24-hour period (Box 19.9). Normally the amounts for intake and output are totalled daily and the fluid balance calculated at the same time each day, often at midnight, or at 06.00 or 08.00 hours. A positive balance exists where the intake exceeds output. This situation occurs when fluid intake is increased to rectify fluid volume deficit and dehydration (see p. 535), whereas a negative balance exists when output exceeds intake. This occurs, for example, when treatment with diuretics is used to rectify fluid volume excess. A record is also kept of the daily fluid balance over several days so that trends can be assessed.

Maintaining fluid balance charts

Placing a sign above the bed or on the door ensures that the patient, the family, nurses, HCAs and housekeepers are aware that the person is having fluid intake and output measured and recorded.

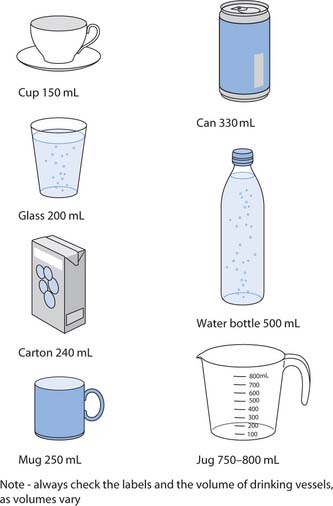

Note: Nurses should know the volumes of jugs and drinking vessels such as cups, glasses, mugs, juice cartons and drink cans used in the ward or nursing home (see Fig. 19.4). Patient-friendly charts showing volumes should be provided to encourage people to record their own intake accurately (Reid et al 2004).

Oral fluids

The average healthy adult needs a fluid intake of 1.5–2.0L per day. Most of this fluid should be water, as caffeine-containing drinks such as tea, coffee and colas cause diur-esis. There are, however, many situations when more than this is needed such as when a person has a urinary catheter in situ (see Ch. 20), strenuous exercise, sweating and diarrhoea and vomiting.

Older people may need a higher intake because their kidneys become less efficient in the production of concentrated urine. In addition, as mentioned earlier, older people may be less sensitive to and/or responsive to the sensation of thirst. Fluid intake may need to increase further when body temperature is raised and in hot weather to prevent dehydration.

The daily fluid requirements for children are determined by weight. Infants have a greater fluid requirement per kg of body weight than do older children (Table 19.3). Infants and small children have very little fluid reserve and are at increased risk of fluid and electrolyte depletion (see p. 532). For example, infants and children with diarrhoea lose water and the electrolytes sodium and potassium (Box 19.10).

Table 19.3 Daily fluid requirements for children (developed from Wong et al 1999)

| Body weight (kg) | Fluid requirement per kg | Worked example |

|---|---|---|

| 1–10 | 100mL/kg | An infant weighing 3.5kg needs 100 × 3.5 = 350mL of fluid per day |

| 11–20 | 1000mL plus 50mL/kg for each kg >10kg | A child of 2½ years weighing 13.5kg needs 1000 + (50 × 3.5) = 1175mL of fluid per day |

| >20 | 1500mL plus 20mL/kg for each kg >20kg | A child of 10 years weighing 32kg needs 1500 + (20 × 12) = 1740mL of fluid per day |

| A teenager weighing 60kg needs 1500 + (20 × 40) = 2300mL of fluid per day |

Oral rehydration salts

3-year-old Wayne has had four loose stools in the last 24 hours and he is ‘off his food’. When his mother telephoned the local surgery the practice nurse told her that the diarrhoea is likely to stop within 24 hours and gave her advice that included giving Wayne oral rehydration salts (ORS) such as Dioralyte®.

Student activities

[Resources: British National Formulary (BNF) – www.bnf.org.uk; NHS Direct Online/Self Help Guide/Diarrhoea in babies and children – www.nhsdirect.nhs.uk/selfhelp/symptoms/babydiarrhoea/start.asp Available July 2006]

Helping people to drink

Whether a person receives adequate oral fluid or not can depend on simple interventions, advice and encouragement provided by nurses and other members of the MDT. For example, just having a glass of water within reach at all times will influence fluid intake.

Success in achieving the goals set for fluid intake depends on providing individualized care that meets the person’s needs. For most people, independence in fluid intake is the norm and nurses must be tactful and sensitive to the feelings of people who need help with drinking. When helping people to drink the nurse should consider points that include the following:

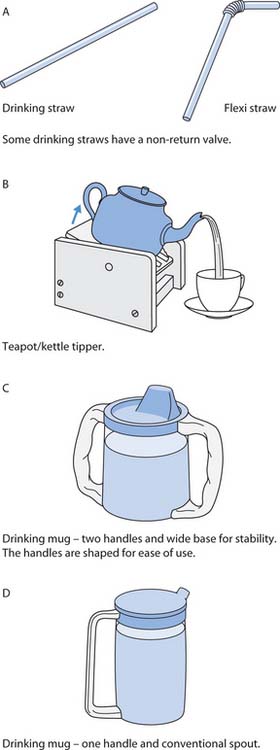

Fig. 19.5 Aids to independence in drinking: A. Drinking straws. B. Teapot/kettle tipper

(reproduced with permission from Roper et al 1995). C. Drinking mug – two handles. D. Drinking mug – one handle

Encouraging people to obtain sufficient oral fluids

The nurse sets a goal for the daily intake and, together with the patient/client, parent or carer, plans the timing of drinks to achieve this. People need to know how many cups or glasses will provide the daily volume needed, as trying to visualize a specific volume, e.g. 1.5L, can be difficult (see Fig. 19.6). Encouragement can be as simple as saying, ‘Is it time for another drink?’ or pouring and offering a drink. Planning an activity that involves a child can encourage them to drink. For example, adding stickers to a card for each drink or by colouring in a chart with the required number of cups or glasses.

Student activities

[Further reading: Haines L, Rogers J, Dobson P (2000) A study of drinking facilities in schools. Nursing Times 96(40): NTplus Continence 2–4]

Fluid restriction

Sometimes fluid intake is restricted, e.g. in kidney failure. The person needs to know the exact volume prescribed and the reason for the restriction. The points above about helping a person to drink, including timing and spacing of drinks, small vessels, favourite drinks, are especially important in this situation.

A person having restricted fluids is likely to have a dry mouth and complain of being thirsty. The nurse can minimize discomfort by offering crushed ice or an ice cube to suck to moisten their mouth while still adhering to the restriction.

Caring for the person with fluid imbalance

Fluid depletion

A person with fluid volume deficit or dehydration requires specific nursing care. For instance, the skin will be dry and loss of skin turgor (see p. 538) increases the risk of pressure ulcers. Lethargy, which can accompany fluid depletion, can reduce mobility and so increase the risk of skin breakdown. The risk should be assessed using a validated rating scale and appropriate preventive measures put in place (see Ch. 25). Because oral condition is often affected and the mouth is dry, mouth care (see Ch. 16) and mouthwashes are needed until hydration improves. Fluid depletion predisposes to constipation and, when possible, oral fluids, a fibre-rich diet and physical activity are the preferred interventions (see Ch. 21). Lack of fluid can lead to confusion and nurses must be alert to the risks associated with increasing confusion and disorientation, e.g. falls.

Oedema

Oedematous, swollen tissue is easily damaged and this increases the risk of infection and pressure ulcers (see Chs 15, 25). It is important that the risk is minimized by ensuring that neither nurses’ nor clients’ fingernails, rings or watches damage the skin. People should avoid scratching affected areas. After washing, swollen tissue should be gently patted dry rather than rubbed. People with ankle and leg oedema are advised to elevate the affected part in order to encourage drainage of the excess fluid. Box 19.12 outlines advice for people with long-term ankle oedema.

Helping people with swollen ankles

Nursing advice

Student activity

Identify any people in your placement who have ankle oedema and find out what of the above they know about.

[Based on Waugh (2003)]

Caring for the person who is vomiting

Prolonged or excessive vomiting can be distressing and may lead to disruption to fluid, electrolyte and acid–base balance (see p. 535). Prior to vomiting the person often experiences nausea (feeling sick); there may be pallor, sweating and excess watery saliva. The causes of vomiting include:

The care needed by a person who is vomiting is outlined in Box 19.13.

Nausea and vomiting

Nursing interventions include

In addition, nurses should ensure that an appropriate antiemetic (drugs that stop vomiting), e.g. metoclopramide, is administered as prescribed. Antiemetics should always be given in anticipation of expected vomiting such as with some anticancer drugs.

Note: Nurses should always wear gloves and a plastic apron if time allows. Vomit is acidic and can damage (‘burn’) the skin. Damage can occur, if for instance, a baby or unconscious person’s face is resting on vomit-stained bedding. Babies who regurgitate may have vomit in the neck creases and nurses must ensure that the skin is washed and gently patted dry.

Subcutaneous fluids (hypodermoclysis)

Subcutaneous infusion of fluids is increasingly used for fluid replacement and the maintenance of hydration in older adults and in palliative care (Mansfield et al 1998, Donnelly 1999). It is used to:

Suitable infusion sites include the thighs, abdomen, and areas over the scapula and the chest wall. The site is only chosen after discussion with the patient and consideration of comfort, ease of access, mobility and skin condition.

Fluid replacement using hypodermoclysis at home or in long-term care establishments can avoid the need to admit frail older people to acute hospitals for rehydration with intravenous fluids (Worobec & Brown 1997, Dasgupta et al 2000).

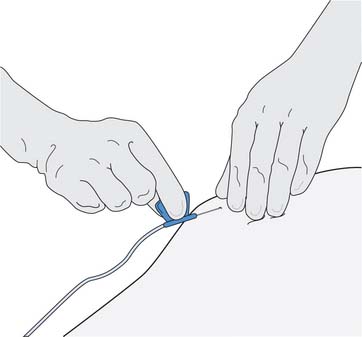

The infusion is given via a butterfly cannula, inserted by a RN into the subcutaneous tissues (Fig. 19.7). The cannula is secured by covering the area with a transparent occlusive dressing for easy observation. The site is changed according to local policy usually every 24 hours or following infusion of 2L of fluid. Intravenous administration (‘giving’) sets are used and a RN checks the infusion fluid, e.g. sodium chloride 0.9% or glucose 5%, before commencing a new bag.

Fig. 19.7 Inserting a butterfly cannula for subcutaneous infusion

(reproduced with permission from Nicol et al 2004)

The infusion rate depends on individual needs but the recommended maximum is 2L in 24 hours or 125 mL/hour into a single site. The prescribed flow rate of subcutaneous fluids can be controlled by using a volumetric infusion pump or regulated by gravity and the roller clamp on the tubing of the administration set.

Fluid overload is unusual but local side-effects include swelling, discomfort or inflammation. The nurse should inspect the infusion site for these, as it might be necessary to change the site.

Intravenous fluids

Intravenous (i.v.) infusion of sterile fluid into the circulation is very common in hospitals and is increasingly used in the community. Most nurses will, at some time, care for patients having i.v. fluids (often referred to as a ‘drip’). The principles of i.v. fluid therapy and some of the nursing interventions are outlined in this section. Detailed information about the care of i.v. infusions, including those aspects that only a RN may undertake, is provided in Further reading (Jamieson et al 2002, Dougherty & Lister 2004, Nicol et al 2004).

Intravenous fluid therapy is used when the oral or enteral routes are inappropriate, e.g. following major surgery, serious burns, severe vomiting. Blood transfusion is discussed in Chapter 17. Intravenous fluids are used to:

Most i.v. fluid therapy is short term and can be infused into a peripheral vein in the dorsum (back) of the hand or the forearm, or a scalp vein in infants. Peripheral veins are not suitable for long-term therapy because inflammation can block the vein (see Box 19.16, p. 549). For long-term therapy and when irritant or hypertonic solutions are used, fluid is infused into the superior vena cava (a large central vein) where blood flow is sufficient to dilute the fluid and prevent damage to the vein (see ‘Parenteral nutrition’, p. 565).

Box 19.16 Complications associated with i.v. therapy

Local complications

Systemic complications

[Further information can be found in Further reading, e.g. Dougherty & Lister (2004)]

Equipment

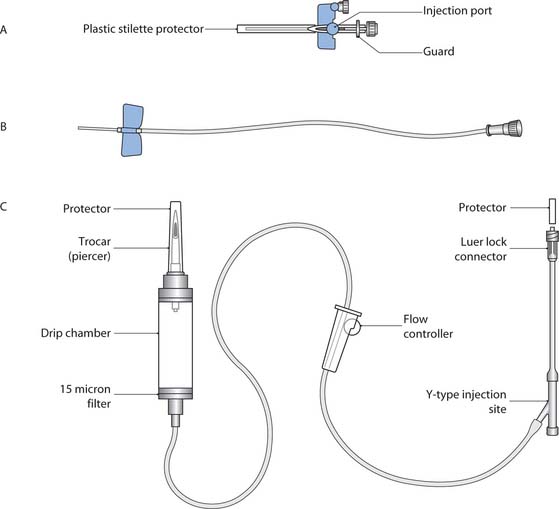

Bags or bottles of intravenous fluid are administered through sterile, single-use items of equipment, namely an administration (‘giving’) set attached to a cannula inserted into the vein. Figure 19.8. illustrates two commonly used cannulae and the parts of a standard administration set.

Fig. 19.8 Intravenous cannulae and parts of an administration set: A. Cannula used when i.v. drugs are administered with the infusion or post-infusion. B. A ‘butterfly’ cannula used for hypodermoclysis or for short-term i.v. infusion. C. Standard administration set for intravenous infusion

(reproduced with permission from Jamieson et al 2002)

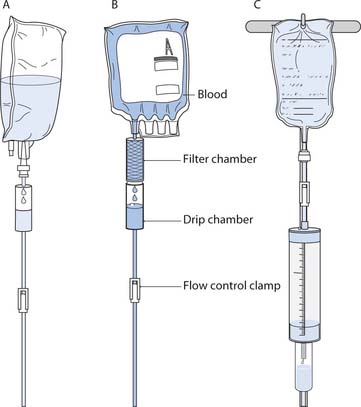

The type of administration set used depends on the fluid being infused and the safety needs of certain groups. A standard administration set (Fig. 19.9 A) is generally used for clear fluids. Blood and blood products are always administered through a set with an integral filter above the drip chamber (Fig. 19.9B; see also Ch. 17). An administration set with a burette (Fig. 19.9 C) can be used when drugs or small volumes of fluid are infused. A burette set must always be used with infants, children and others at risk of fluid overload, e.g. frail older people, to prevent accidental infusion of excess fluid (see p. 549). Volumetric infusion pumps (see p. 549) or syringe drivers (Ch. 23) are frequently used and always when precise accuracy is required.

Fig. 19.9 Types of intravenous administration set: A. Standard administration set. B. Blood administration set. C. Burette (paediatric set)

(reproduced with permission from Nicol et al 2004)

Crystalloids and colloids

Fluids for i.v. infusion are divided into crystalloids and colloids. A crystalloid is a clear solution that moves between the bloodstream and the tissue fluid. They are used intravenously to maintain hydration and electrolyte balance and many are supplied with potassium chloride (KCl) added. Examples of crystalloid solutions include:

Colloid solutions contain particles (solutes) that stay in the blood because they are too large to pass through capillary membranes and are used to increase blood volume. Examples include:

Principles of care for infusions

The overriding principle is to ensure the safety and comfort of the person having i.v fluids.

The non-dominant arm should be used to site the i.v. infusion whenever possible, thus maximizing independence and minimizing inconvenience. The person may be more comfortable if a pillow with a waterproof cover is used to support the arm or a lightly bandaged single-use splint is applied. The arm may also need to be immobil-ized with a single-use splint and bandage, according to local policy, if there is a risk of the cannula becoming dislodged such as with small children or adults who are restless or confused.

It is also important to note that Muslims use the left hand for personal cleansing and the right hand for feeding. This has important implications for the siting of i.v. infusions and the wishes of the patient must be taken into account.

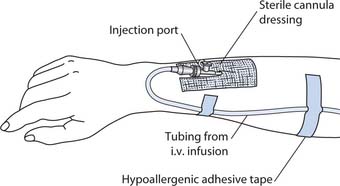

Once the i.v. cannula has been sited, it is secured in place with a sterile cannula dressing (Fig. 19.10). The fluid container is connected to an appropriate administration set and fluid is ‘run through’ to expel air from the tube before connection to the cannula. The tubing is anchored to the arm (see Fig. 19.10). The date of cannula insertion and type of administration set is recorded in the nursing notes. The cannula is usually changed every 72 hours and even in 24 hours if the cannula has been sited in an emergency as there is some doubt about asepsis during insertion (RCN 2003). This may vary according to local policy.

Fig. 19.10 Cannula dressing and securing the tubing

(reproduced with permission from Jamieson et al 2002)

An i.v. infusion is an invasive procedure so aseptic technique and standard precautions must be in place to prevent the entry of contaminants such as micro-organisms, and to protect the staff from potentially infectedbody fluids (see Ch. 15). The closed system only protects if it is kept closed and when it is necessary to open the system, e.g. to change the fluid bag, it is vital that the nurse adheres to the precautions outlined above. Figure 19.11. illustrates the potential routes for contamination.

Fig. 19.11 Potential routes for contamination during intravenous infusion

(reproduced with permission from Jamieson et al 2002)

Fig. 19.12 Changing the infusion bag – inserting the administration set spike into a new bag

(reproduced with permission from Nicol et al 2004)

Intravenous fluid bags are changed using aseptic technique every 24 hours. Usually administration sets are changed every 72 hours for peripheral i.v. fluids and this is recorded in the nursing notes. The cannula site is inspected regularly for signs of inflammation such as redness, swelling and pain that may indicate the development of phlebitis (inflammation of a vein), infection or other complications (see Box 19.16, p. 549). The dressing around the cannula is changed aseptically if it has become loose, wet or bloodstained. If the dressing is in place, dry and clean, it is usually left undisturbed until the cannula is re-sited or removed (readers should check local policies).

All fluids for i.v. infusion are prescribed and a RN must check that the correct fluid is administered to the correct person. Some areas require that two nurses (one registered) check i.v. fluids. The outer wrapping is removed from the bag and it and the fluid are checked for:

The type and volume of fluid, e.g. 500 mL of sodium chloride 0.9%, is checked against the prescription sheet and the person’s identity band is checked. When a bag of i.v. fluid is commenced the details including the batch number are recorded in the nursing records. In addition, i.v. fluid volumes are recorded on the fluid intake and output chart. The principles of changing infusion bags are outlined in Box 19.14.

Infusion bag change

Maintaining safety is paramount when undertaking a bag change. The key principles are as follows:

The bag change is explained and a visual check of the cannula site made, observing for the presence of complications (see Box 19.16).

[Based on Nicol et al (2004)]

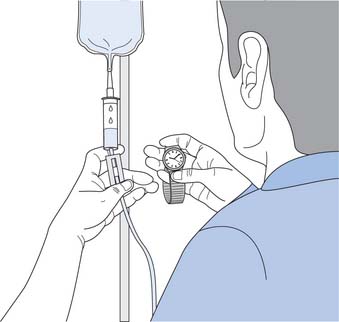

Flow rate calculation and regulation

Nurses are responsible for calculating and regulating the flow rate of i.v. fluids. The flow rate can be regulated by gravity and the roller clamp on the administration set tubing, or by an infusion pump.

The flow rate is checked at least hourly. Factors that may reduce the flow rate or stop it completely include:

Intravenous infusion pumps are increasingly used to regulate the flow rate. They should be used:

Most models have audible alarms that alert the nurse to situations that include ‘infusion complete’, ‘air in line’ and when flow is obstructed. It is imperative that alarms are never turned off. RNs are responsible for using pumps safely in accordance with the manufacturer’s instructions. RNs receive training for each type of pump used in their area and are competent in their use. Nurses who are unsure about a particular pump must seek help and advice from a more experienced colleague. Student nurses may only deal with pumps when directly supervised by a RN.

Box 19.15 outlines the formulae used to calculate flow rates in drops per minute and millilitres per hour.

Calculating i.v. flow rates

Infusion flow rates are calculated in one of two ways: drops per minute or millilitres per hour.

Drops per minute

This calculation is used for infusions regulated by gravity and roller clamp on the administration set and for regulatory devices that use drops per minute. In gravity/roller clamp regulation it is vital that the flow rate remains constant. Each type of administration set (see Fig. 19.9) has a specific ‘drop factor’ (drops per mL):

Millilitres per hour

Millilitres per hour are used when the i.v. flow rate is to be regulated by a volumetric infusion pump or syringe driver.

Student activities

[Resources: Gatford JD, Phillips N 2006 Nursing calculations, 7th edn. Churchill Livingstone, Edinburgh; MacQueen S 2005 The special needs of children receiving intravenous therapy. Nursing Times 101(8):59–64]

Complications of i.v. therapy

Complications associated with an i.v. infusion may be local or systemic and range from minor to serious and life threatening. Box 19.16 provides an overview of common complications; complications specific to blood transfusion are discussed in Chapter 17.

Nutrition

This part of the chapter explores health-promoting activ-ities and nursing interventions such as feeding that help people to obtain the correct nutrients in sufficient quan-tities to meet individual needs. The importance and scope of these are illustrated in the best practice benchmarks in the Essence of Care (NHS Modernisation Agency 2003) (see Box 19.17). In addition, an understanding of digestion and absorption of nutrients, the principles of nutrition and healthy eating throughout the lifespan are important in ensuring that nurses can meet the nutritional needs of people in their care.

Using benchmarks of best practice

Student activities

Benchmarks of Best Practice – Food and Nutrition (NHS Modernisation Agency 2003, pp. 1–2)

The gastrointestinal tract

An overview of structure and function is provided here and readers should consult their own anatomy and physi-ology book for more detail. In addition, Chapter 16 discusses the structures of the mouth and Chapter 21 the large intestine and defecation.

The general structure of the GI tract comprises four layers:

The basic, four-layer structure is modified at various points according to the function of that part. For example, the presence of villi (microscopic projections) in the mucosa of the small intestine increases the surface area available for the absorption of nutrients.

Parts of the gastrointestinal tract

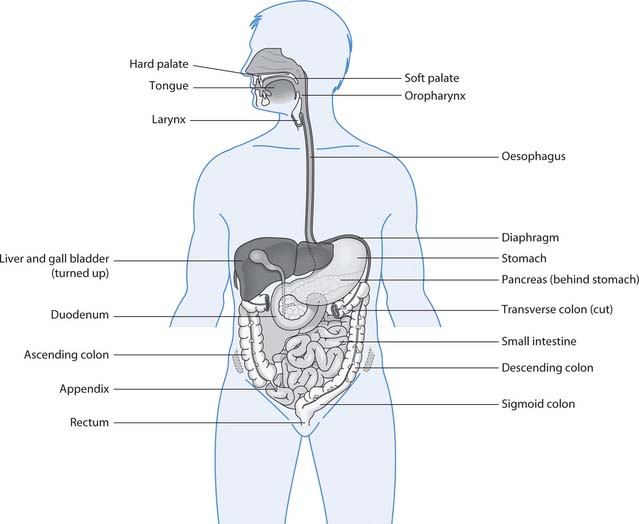

The GI tract is essentially a long tube that starts at the mouth and ends at the anus (Fig. 19.14). The individual parts are:

Fig. 19.14 The gastrointestinal tract and some accessory organs

(reproduced with permission from Waugh & Grant 2006)

Mouth

The mouth (oral cavity) and accessory structures (teeth, tongue, salivary glands that secrete saliva) are concerned with the ingestion, chewing (mastication), some chem-ical digestion of food and the first stage of swallowing. Taste sensation is discussed on page 552.

Pharynx

The three-part pharynx (nasopharynx, oropharynx and laryngopharynx) is a cone-shaped, muscular cavity situ-ated behind the nose and mouth. However, only two parts (oropharynx and laryngopharynx) are common routes for food, fluid and air and there are mechanisms that normally keep food or fluids out of the larynx during swallowing. Swallowing involves three stages:

Oesophagus

The muscular oesophagus is a tube that has no role in digestion or absorption. The oesophagus runs from the laryngopharynx through the thoracic cavity and diaphragm to the stomach. Food and fluid enter the stomach through the gastro-oesophageal (cardiac) sphincter or valve. This is a physiological sphincter where oesophageal muscle contraction keeps the oesophagus closed until swallowing occurs.

Stomach

The stomach is roughly J-shaped and, in adults, can comfortably hold 1.5L of food and fluids. The mucosa is arranged in folds, or rugae, which greatly increase the surface area for secretion and allow for considerable distension following a meal. However, in infants and children stomach capacity is much smaller. For example, a newborn baby has a capacity of 15–30 mL, which has implications for volumes of feed and frequency of feeding. In addition, the gastro-oesophageal sphincter is underdeveloped, predisposing to regurgitation.

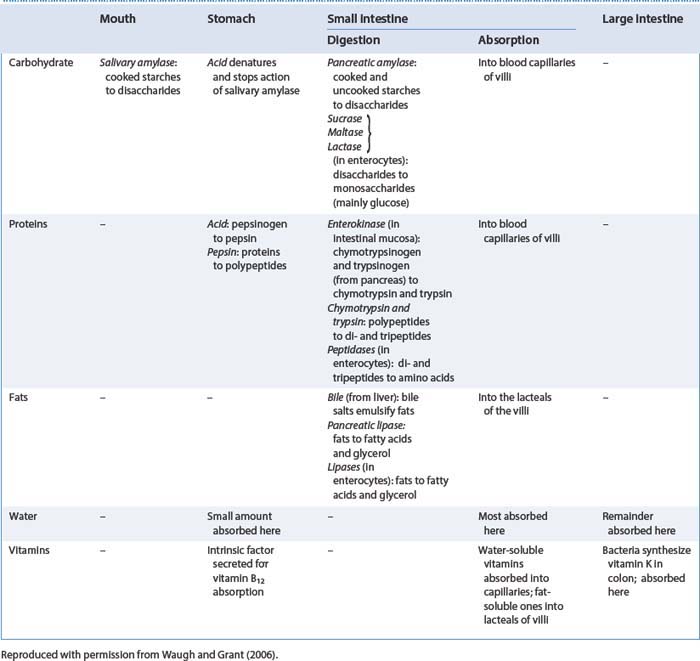

The stomach churns and mixes food with gastric juices to form the semi-fluid chyme. There is some digestion and limited absorption in the stomach (see Table 19.4). Chyme leaves the stomach through the pyloric sphincter, ensuring the coordinated release of gastric contents into the small intestine.

Small intestine

The small intestine has three parts: duodenum, jejunum and ileum. The duodenum is continuous with the stomach and the ileum leads into the ileocaecal valve where the large intestine starts. Secretions from the pancreas and bile from the gallbladder both enter into the duodenum. Chemical digestion is completed in the small intestine by enzymes from the pancreas and those secreted in the intestinal juice, and nutrients are absorbed (see Table 19.4).

Overview – functions of the gastrointestinal tract

The GI tract, plus the secretions from various accessory organs – three pairs of salivary glands, the liver, gallbladder and bile ducts and the pancreas (see Fig. 19.14) – are concerned with five main activities:

Table 19.4 provides a summary of the sites of nutrient digestion and absorption.

Smell and taste

The senses of smell and taste are intricately linked and both are important for appetite and nutritional intake. Being able to smell and taste food:

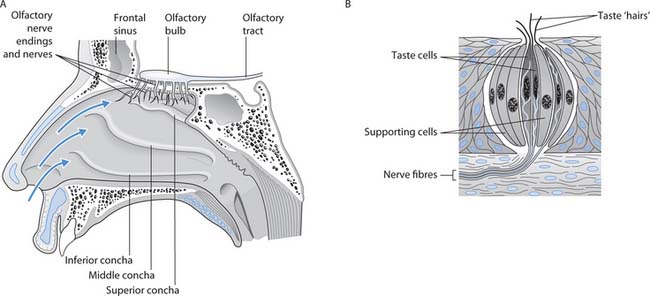

Anatomy and physiology of smell

The sense of smell, or olfaction, is provided by specialized nerve endings (chemoreceptors) in the roof of the nasal cavity (Fig. 19.15 A). These nerve endings are sensitive to thousands of different chemical odours. Nerve fibres transmit impulses to the temporal lobes of the brain for recognition and interpretation.

Fig. 19.15 Smell and taste: A. Nose showing the olfactory nerve endings. B. A highly magnified taste bud

(reproduced with permission from Waugh & Grant 2006)

Anatomy and physiology of taste

The sense of taste, or gustation, is provided by taste buds, which contain sensory receptors (chemoreceptors) (Fig. 19.15 B). Most taste buds are located on the tongue and a few on the soft palate and the back of the throat. Chemicals dissolved in saliva activate the chemoreceptors in the taste buds, generating nerve impulses that are transmitted to an area in the parietal lobes of the brain where taste perception occurs.

Four basic taste sensations have been described: salt, sweet, bitter and sour. This is probably too simplistic, as individual perception of taste varies widely.

Alterations to smell and taste

Abnormalities of smell include a reduction in the sense of smell (hyposmia) and complete loss of smell (anosmia). Problems can be temporary, such as with a common cold, or may be permanent, e.g. after head injury (see Box 19.18).

Smell and appetite

Think about situations when your appetite was affected by smell, e.g. a favourite meal being cooked.

Taste, and hence appetite, can be impaired if a cold affects the olfactory receptors in the nose. Alterations in taste can also occur if the mouth is dry, e.g. fluid deficits (p. 535), and when oral hygiene and/or dental health is poor (see Ch. 16).

The senses of taste and smell change with normal ageing; there is gradual loss of taste and olfactory receptors, which accounts for the diminished sense of taste and smell in older people. Older people may complain that ‘modern food’ has no taste and this can contribute to a reduction in appetite. Nurses can suggest stronger flavours and aromas, seasoning and different textures that may improve the taste of meals.

Disturbances in smell or taste can occur as part of a disease or as a side-effect of some drugs (see Box 19.19).

Box 19.19 Disturbances in smell and taste

Nutritional and upper gastrointestinal tract disorders

Some common nutritional disorders, upper GI tract disorders and other conditions that impact on nutrition are outlined in Table 19.5. Related associations and groups also provide useful information (Boxes 19.20, 19.21) and some websites are included at the end of this chapter.

Table 19.5 Common nutritional disorders and other conditions affecting nutrition.

| Obesity (see Box 19.20) |

Obesity is very common in developed countries and two-thirds of the population in England is overweight or obese (House of Commons Select Committee 2004)

|

| Eating disorders (see Box 19.21) |

• Anorexia nervosa characterized by distorted body image and a deliberate restriction of food intake resulting in severe weight loss, malnutrition, endocrine disorders and electrolyte disturbances (see p. 535)

|

| Nutritional deficiencies | Deficiencies may involve a single nutrient such as poor iron intake leading to anaemia or protein–energy malnutrition (PEM) in which the person has a diet deficient in protein and energy |

| Failure to thrive | |

| Food intolerance | |

| Food allergy | |

| Malabsorption | |

| Diabetes mellitus (see also Chs 16, 25) | |

| Mouth problems | These include: |

| Diaphragmatic hernia (hiatus hernia) | |

| Gastro-oesophageal reflux disease (GORD) | |

| Peptic ulceration | A non-malignant ulcer in those parts of the GI tract exposed to gastric juice; usually the duodenum or stomach |

| Cancer |

Box 19.20 WHO definition of overweight and obesity according to body mass index (BMI)

Note: BMI is discussed more fully in Box 19.27.

[From WHO (1998)]

Eating disorders

A friend asks you about eating disorders. She wants to know some basic facts and where to get information and help.

Student activities

[Resources: BBC Eating disorders – www.bbc.co.uk/health/mental_health/disorders_eating.shtml; Eating Disorders Association – www.edauk.com; NICE 2004 Core interventions in the treatment and management of anorexia nervosa, bulimia nervosa and related eating disorders – www.nice.org.uk Both available July 2006]

Principles of nutrition and the healthy diet

A healthy diet comprises the correct nutrients in appropriate amounts. This varies during the lifespan and during injury and ill health. For instance, a healthy diet for a toddler differs from that needed by an older adult or someone with diabetes.

Nutrients provide energy for body functions such as muscle contraction, for growth, tissue repair and replacement, and for health maintenance. The nutrients can be divided into:

Many individual foods contain several nutrients, e.g. potato provides carbohydrate, protein, minerals and vitamins and also indigestible fibre.

As water is vital in the ingestion, digestion, absorptionand use of nutrients, an adequate fluid intake is also needed(see p. 534 [adults] and p. 541 [children]). In addition, a healthy diet should also contain fibre or non-starch polysaccharide (NSP) (see below).

The energy value of food is measured in the SI unit kilo-joules (kJ) but in food labelling the kilocalorie (kcal) content is often shown too. Note: 4.186kJ (4.2 approx) 51kcal or calorie.

The amount of energy needed varies greatly between people and depends on:

Although alcohol is not a nutrient its consumption can substantially increase the total energy intake, as 1 g of alcohol yields 29kJ (7kcal). Excessive alcohol intake causes health problems that include:

An outline of recommended ‘safe limits’ for drinking alcohol is provided in Box 19.22.

Alcohol ‘safe limits’

Men can have up to 3–4 units of alcohol/day and women can have up to 2–3 units/day, without significant risk to health (Food Standards Agency 2005).

Student activities

Access the Food Standards Agency (FSA) website:

[Resource: Food Standards Agency – www.eatwell.gov.uk/healthydiet/nutritionessentials/drinks/alcohol Available July 2006]

An outline of the main nutrients and their functions in the body and food sources are provided below but readers should consult Further reading suggestions (e.g. DH 1991) for details of dietary reference values across the lifespan.

Macronutrients

Carbohydrates

Carbohydrates may be sugars – monosaccharides (glucose, fructose and galactose), disaccharides (maltose, lactose and sucrose) or polysaccharides such as starch or glycogen. During digestion available carbohydrates are mainly broken down into glucose, which is used in the body as the major energy source. Each gram of carbohydrate yields 16kJ (3.75kcal). Some is used immediately, some stored as glycogen in the liver and skeletal muscles, but any excess is converted to fat.

Carbohydrates are obtained from sugar, pulses, yam, potato and other vegetables, fruit, cereals such as wheat, rice and maize, plus products made from flour, e.g. bread, pasta and chapattis.

NSP is the indigestible plant material, e.g. cellulose and other polysaccharides, that ensures steady absorption of glucose from the intestine, gives a feeling of fullness, adds bulk to the faeces and decreases the time waste remains in the large intestine (see Ch. 21). Good sources of NSP include wholegrain cereals, pulses, vegetables and fruit. An average intake of 18 g/day is suggested for adults. Children should have proportionally lower NSP intakes, and children under 2 years of age should not have NSP-containing foods at the expense of energy-rich foods that are needed for normal growth (DH 1991).

Fats

Fats are formed from glycerol and fatty acids. Fatty acids are classified as saturated, monounsaturated or polyunsaturated according to their chemical structure. Fats are emulsified by bile salts in the small intestine and broken down by fat-digesting enzymes into glycerol and fatty acids. The fatty acids are used as a stored energy source, to form lipid (fat-like) substances such as prosta-glandins and phospholipids, and as a source of the fat-soluble vitamins A, D and E and cholesterol. When 1 g of fat is oxidized, it yields 37kJ (9kcal). This is twice as much energy as that produced by the same weight of protein or carbohydrate and although this makes it valuable when energy requirements are high, excessive intake in sedentary people leads to obesity. Children under 2 years of age should be given full-fat dairy products.

Fat is obtained from full-fat dairy products, margarine, ghee, cooking oils, fried foods, cakes, biscuits, crisps, pastry, chocolate, meat, oily fish, nuts, pulses and seeds.

Proteins

Like carbohydrates and fats, proteins contain not only carbon, hydrogen and oxygen, but also nitrogen and sometimes sulphur and phosphorus. They are broken down during digestion to provide the amino acids required by the body for protein synthesis, tissue growth and repair and, under certain conditions, for energy (1 g of protein yields 17kJ or 4kcal).

The reference nutrient intake for protein in adults is between 45 and 55.5 g/day depending upon gender and age (DH 1991). However, this increases during growth, pregnancy, lactation and illness.

Protein may be obtained from both animal and vege-table sources, e.g. meat, milk, cheese, fish, eggs, nuts, pulses, tofu and cereals. It is, however, vital that vegetarians and vegans obtain a balanced intake, as some cereals are deficient in the amino acid lysine and some pulses are deficient in methionine.

Micronutrients

The micronutrients are the minerals (including trace elem-ents) and vitamins required by the body in relatively small amounts. They are necessary for many vital body functions, e.g. iron for haemoglobin synthesis, vitamin K for blood clotting. An outline of minerals is provided in Table 19.6 and vitamins in Table 19.7. Readers should consult their own anatomy and physiology book for details of mineral and vitamin functions.

Table 19.6 Minerals and dietary sources

| Mineral | Dietary sources |

|---|---|

| Calcium | Hard water, milk and milk products, sardines, bread, soya beans, lentils, sesame seeds |

| Iodine | Seafood, milk, dairy products, eggs, meat, iodized salt |

| Iron | Offal, red meat, egg yolk, cereal products, pulses, vegetables, cocoa, dried fruit, potatoes |

| Magnesium | Nuts, seeds, cereals, cereal products, potatoes, green vegetables |

| Phosphorus (phosphates) | Many animal and vegetable proteins |

| Potassium | Vegetables, potatoes, fruit juices, bananas, dried fruit, instant coffee granules, Marmite, meat, fish |

| Sodium | Common salt, cereal products, meat products, vegetables, cheese, sauces, pickles, snack foods, prepared meals |

| Zinc | Meat and meat products, milk, eggs, cereals, bread, pulses, nuts |

Table 19.7 Vitamins and sources

| Vitamins | Sources |

|---|---|

| Fat-soluble | |

| Vitamin A | Liver, kidney, oily fish, egg yolk, full fat dairy produce |

| Green, yellow, orange and red fruit and vegetables, e.g. broccoli, carrots, apricots, sweet potatoes, tomatoes | |

| Vitamin D | Oily fish, egg yolk, butter, fortified margarine |

| Action of sunlight on the skin | |

| Vitamin E | Widespread. Best sources are nuts, seeds, vegetable oil, egg yolk and some cereals |

| Vitamin K | Many vegetables and cereals |

| Also synthesized by intestinal bacteria | |

| Note: Requires bile in the intestine for absorption | |

| Water-soluble | |

| Vitamin B1 – Thiamin | Milk, liver, eggs, pork, fortified breakfast cereals, vegetables, fruit, wholegrain cereals |

| Vitamin B2 – Riboflavin | Milk, milk products, offal, fortified breakfast cereals |

| Destroyed by sunlight | |

| Vitamin B3 – Niacin | Meat, fish, pulses, wholegrains, fortified breakfast cereals |

| Can be synthesized from an amino acid in the body | |

| Vitamin B5 – Pantothenic acid | Liver, eggs, cereals, yeast, vegetables |

| Vitamin B6 – Pyridoxine | Meat, fish, whole cereals, eggs, some vegetables |

| Biotin (B group) | Widely distributed in many foods, e.g. offal, egg yolk, legumes |

| Can be synthesized by intestinal bacteria | |

| Vitamin B12 – Cobalamins | Animal products, meat, eggs, fish, dairy products, yeast extract, fortified breakfast cereals |

| Strict vegetarians and vegans may require dietary supplements | |

| Note: Requires intrinsic factor secreted by the stomach for absorption | |

| Folates/folic acid (B group) | Green vegetables, fortified breakfast cereals, yeast extract, liver, oranges |

| Supplement recommended prior to conception and during first 3 months of pregnancy to reduce the incidence of spina bifida | |

| Vitamin C – Ascorbic acid | Citrus fruits, blackcurrants; green leafy vegetables; potatoes; strawberries; tomatoes |

| Content decreases with storage | |

| Destroyed by cooking in the presence of air and by cutting and grating raw food |

Recommendations for a healthy balanced diet

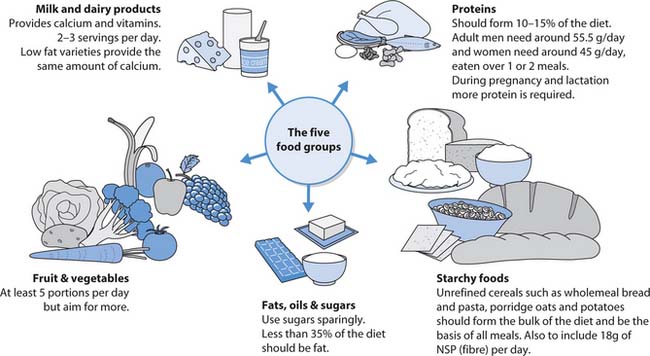

A healthy, balanced diet is one that provides all the nutrients outlined above in the correct proportions (Box 19.23). Eating a variety of different foods is likely to provide a balanced diet. It is convenient to classify foods of similar composition and nutrient content into five food groups:

Healthy packed lunches

The House of Commons Select Committee (2004) report that, in England, 25% of children are overweight and 6% are obese. The promotion of healthy eating in schools, together with other measures, is important in reducing the number of children who are overweight or obese.

Student activities

[Resource: www.food.gov.uk/news/newsarchive/2004/sep/lunchbox2 Available July 2006]

The list above starts with foods that should be eaten in small amounts or, in the case of confectionery, only very occasionally and ends with the starchy foods which should provide around a third of the daily energy requirement. Figure 19.16. illustrates the five groups and a balanced diet for most adults.

The Food Standards Agency (2005) recommends that most adults should:

Infant feeding

Breast milk is the perfect food for healthy babies. It contains all the essential nutrients in proportions that meet growth and development needs of babies during the first 6 months. Moreover, breast milk contains maternal antibodies and these help to protect babies while their own immune systems develop. In addition, there are advantages to the mother that include special contact with her baby and ready availability of feeds.

Richardson and Fairbank (2000, p. 42) state ‘increasing the initiation of breastfeeding represents an important public health challenge’ and that breastfeeding rates in the UK remain low with between 40 and 60% of mothers starting (Box 19.24). Mothers in disadvantaged groups, e.g. teenagers, have the lowest rates.

Infant feeding

You have been asked to assist with a parent education session about infant feeding with your mentor.

Student activities

[Resources: Food Standards Agency – www.eatwell.gov.uk/agesandstages/baby; NHS Direct – www.nhsdirect.nhs.uk/en.aspx?ArticleID563; DH Breastfeeding leaflet 2004 – www.dh.gov.uk/assetRoot/04/13/54/12/04135412.pdf; DH Bottle feeding leaflet 2005 – www.dh.gov.uk/assetRoot/04/12/36/20/04123620.pdf All available July 2006]

The milk produced during the first three days after birth is known as colostrum. It contains antibodies and because it is less rich than mature breast milk it meets the needs of newborn babies. Mature breast milk is usually produced by the fourth day.

Artificial bottle-feeding with infant formula milks may be used by choice or where a contraindication exists; for example, a baby who needs special milk or a mother who is severely undernourished. Bottle-feeding has several disadvantages that include increased episodes of diarrhoea and the potential for over- or underfeeding. Maintaining high standards when cleaning and sterilizing bottles and other equipment, and preparing and storing feeds is vital (see Box 19.24).

Weaning is the gradual introduction of solid food to the milk-only diet of babies. Weaning should start when the baby is 6 months old. Breast or formula feeding is continued during weaning. First weaning foods are:

During the next 6 months the variety, frequency and amount of solid food is increased so that by the age of 1 year the baby is having three family meals a day and around600 mL of milk. Babies under 12 months of age must not be given cow’s, sheep’s or goat’s milk because it:

Factors that affect food intake and appetite

Several physical, psychological, cultural and social factors can affect food intake. The nurse must be able to identify the factors that increase the risk of people develop-ing nutritional problems such as malnutrition caused by inadequate food intake (see p. 554). Many of these factors are outlined below and some are explored further in the section about helping people to eat. These include:

Understanding healthy eating

Think about a group of clients you have met while on placement. You might choose:

Student activities

[Resources: Food Standards Agency – www.eatwell.gov.uk/healthydiet/nutritionessentials Available July 2006; Goodman L, Keeton E 2005 Choice in the diet of people with learning difficulties. Nursing Times 101(14):28–29; Grassick S 2001 Nutrition and learning disabilities. Nursing Times 97(32): NTplus Nutrition 48, 50; Kinder H 2004 Implementing nutrition guidelines that will benefit homeless people. Nursing Times 100(24):32–34]

Meeting religious and cultural dietary needs

Vijay Lal Sharma has told the staff in the care home that he does not eat beef. On Sunday the residents are served roast beef for lunch and the care assistant is surprised when Vijay declines to eat the alternative first course provided for him. He explains that he is worried that his meal may have been in contact with the beef in the kitchen or during serving.

Student activities

Note: Animal products such as gelatin can be present in foods, e.g. desserts, which might be assumed to meet the needs of vegetarians.

Malnutrition in vulnerable people

It is a shocking fact that vulnerable people can become malnourished while in hospital and in community settings, including those living at home, but many authors confirm this to be so (Edington et al 1996, McCormack 1997, Corish & Kennedy 2000, Holmes 2003). People whosediets are deficient in protein and energy and/or have increased nutritional needs, e.g. following major surgery, are at risk of protein–energy malnutrition (PEM). It is vital that those at risk of malnutrition are identified on admission and this is discussed below.

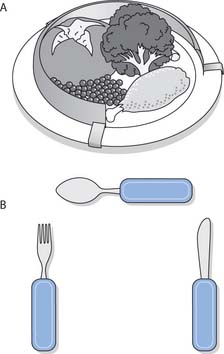

Independence in eating

For most children, achieving independence in feeding starts around 9–10 months when they handle food to explore textures and put food in their mouths. During the next 12 months or so children learn to hold a spoon and use it to transfer food into their mouth. Early attempts at feeding are often accompanied by frustration and considerable mess, as food is dropped. It is important to encourage self-feeding while laying the foundation for good habits such as washing the baby’s hands prior to eating.

Some people cannot achieve full independence in feeding, e.g. people with dementia or a severe learning and/or physical disability. Nurses must look for ways of maintaining their dignity by ensuring that they have as much independence as is possible. This might be achieved by providing ‘finger food’, e.g. sandwiches or pieces of fruit or raw vegetable, which the person can hold without requiringcutlery or manual dexterity. This maintains the dignity and independence of these people. The skills required to feed people are discussed on page 560.

Nursing interventions – maintaining nutritional status

Nursing interventions are often vital in helping people maintain or improve their nutritional status. This section explains nursing interventions including:

In addition, some common investigations used to diagnose upper GI tract disorders that can affect nutrition are outlined.

Nutritional screening and assessment

The assessment of nutritional status requires a holistic approach that embraces physical, social, emotional, spiritual and psychological aspects. The Essence of Care document states that ‘nutritional trigger assessment should always be undertaken at initial contact and the need for reassessment of patients should be continuously considered’ (NHS Modernisation Agency 2003, p. 2).

It is essential that people be screened on admission to identify those with existing malnutrition and those at risk of malnutrition (see below). People with a high risk must be referred to a dietitian or specially trained RN for a wide-ranging nutritional assessment. A nutritional assessment includes:

Nutritional screening audit tool

The Malnutrition Universal Screening Tool (MUST) (BAPEN 2003) is one such screening tool. MUST uses a five-step approach for adults in all settings:

Body mass index (BMI) is a measurement calculated using body weight and height. It is used to ascertain whether an adult is within a healthy weight range for their height.

BMI is weight (in kg) divided by the height squared (m2):

Jane weighs 53 kg and is 1.57 m tall:

Note: BMI, 20 is significant in the MUST screening tool (BMI for overweight and obesity is shown in Box 19.20).

Stratton et al (2004) suggested a high prevalence of malnutrition in hospital inpatients and outpatients (19–60% using MUST) and agreement beyond chance between MUST and most other tools studied. MUST was quick and easy to use in these patient groups.

Nutritional screening and assessment in children is more specialized and readers are directed to Further reading (Khair & Morton 2000).

Common investigations

There are also many investigations used to identify GI tract disorders affecting nutrition (Box 19.28).

Box 19.28 Common investigations for upper GI tract disorders

The following investigations may be used to diagnose or evaluate treatment for upper GI tract disorders:

A simple explanation of some of these investigations accessed on the BBC website (BBC 2005) will help you provide patient information; more detailed nursing explanation can be found in McGrath (2003). The information about tests needs to take account of the person’s ability to understand and retain facts, e.g. modification may be required for a child or a person with a learning disability or dementia.

Helping people to eat

Helping people to eat enough to meet their needs may involve the patient/client and their family and appropriate members of the MDT, including dietitians, specialist nurses, doctors, OTs, SLTs, physiotherapists, ward hostesses, porters and laboratory staff.

Making appropriate healthy choices

Nurses should assist people who need help to choose from a menu. Some people may be unable to read or understand the menus. Moreover, a person with a learning disability or dementia may not remember what they had ordered when the meal is served and will need reminders.

Others may need explanations about the most suitable items if they have cultural or religious needs or are prescribed special diets, e.g. reducing or diabetic diets.

Environment and mealtimes

The nurse needs to ensure that the environment is conducive to eating. Basic activities that encourage eating include:

Food fortification

This involves measures that modify the nutrient quality of the diet and may be advised for people who have small appetites and find it difficult to consume large volumes of food at a single meal. Fortification can be useful in the care of older people. Measures for people who are malnourished or those at risk of malnutrition may include:

Feeding

Nurses should only feed older children or adults when all other options have been tried and proved ineffective. Sometimes it is enough to spend time with people at mealtimes to encourage and motivate them to feed themselves, thereby maintaining their independence and dignity.