Chapter 3 Health and social care delivery systems

Introduction

Health and social care provision in the UK is multifaceted in that it involves a variety of areas and is multidisciplinary because a number of different professional groups work together. It can also be described as being a multiagency enterprise since there are many organizations with different sources of funding involved in it. This means that it is a complex system and one that varies in the different countries that make up the UK. This chapter will concentrate on the structure of services provided in England as the largest member country. Whereappropriate, some of the important variations that exist within the other three countries will be highlighted, but readers will need to consider how the service applies to where they live. Examples of how to locate or access information about local service provision are supplied.

When thinking about the NHS in the UK, consideration needs to be given as to why, when and how it was formed. This chapter outlines the answers to these questions as well as giving some idea of how the health of the general population is looked after, and how the health and social care structures are organized or arranged to prevent illness and to provide treatment and care for the vulnerable members of society.

The complexity of the NHS, its organization, structure and the various relationships between the many professionals that are necessary to deliver effective services is dynamic and are interesting areas to explore. Where appropriate, various aspects of health and social care are illustrated using community-based scenarios. The information and the understanding gained from this chapter will provide an underpinning for the content and learning that readers will achieve from other chapters in this book. This chapter provides an introduction to the history of the NHS and its current structure and function, health and social care provision, the services it offers and its funding, and multidisciplinary and multiagency working. The appropriate legislation which underpins the delivery of health and social care is discussed throughout. In addition, the chapter considers the provision of high quality health and social care, consumer involvement and the mechanisms that are put in place to positively influence the delivery of high quality care.

The structure, services provided and delivery of health and social care have undergone numerous changes over past decades in order to meet the developing needs of the UK population. It is important that the provision of health and social care is dynamic and able to respond as needs change. Readers should be aware that changes, both minor and major, are planned or being proposed or discussed. It is important that readers ensure that they are aware of changes to services as they happen. For example, the English White paper Our Health, Our Care, Our Say: A New Direction for Community Services will lead to profound changes in the way services are delivered, including moving resources from hospital care to spending more on care closer to home and on preventative services (Department of Health [DH] 2006).

Health and social care provision

In the period following World War 2 (1939–1945), the Welfare State (which arose from the Beveridge Report 1942) was created in the UK. This was seen as a blueprint for the state in playing a greater role in the removal of what Beveridge termed the ‘five giant evils’, namely:

This was to be achieved through:

These recommendations (Beveridge 1942) formed the basis of the Welfare State, which included the provision of health and social care in order to combat the ‘five giants’.

The founding principle upon which the NHS was set up and continues to be underpinned is the provision of quality care that:

However, since the formation of the NHS in 1948, it has failed to keep pace with changes in the health and social care needs of the population. These are still seen as challenges to be met by The NHS Plan: A Plan for Investment, A Plan for Reform (DH 2000). In 2003 the structure of the NHS and social care system in England was radically transformed in which:

Since 1992, with the publication of the White Paper The Health of the Nation: A Strategy for Health in England (DH 1992), the government started to set targets for the health of the population in addition to targets for the provision of healthcare services (Macpherson 1998).

Brief history – changes since 1948

In order to understand the NHS and how it operates today, an awareness of the historical context of why and how the NHS came about is necessary (Box 3.1). This helps to make sense of where it is today as well as understanding why successive governments over the years have made some policy decisions. For example, in the early part of this century there was considerable media coverage about the creation of foundation hospitals in England. Important concerns for many politicians that were expressed at that time were, whatever changes to hospital provision took place, access to treatment should be free at the point of delivery and be based on patient/client need rather than an individual’s ability to pay. An understanding of the historical context of NHS developments will help readers to understand that concerns about foundation hospitals were related to the fundamental principles of the NHS and led to much political discussion. Changes in the NHS are largely influenced by prevailing politics of the time.

Box 3.1 Key health and social care developments since 1948

[After Macpherson (1998), Merry (2005)]

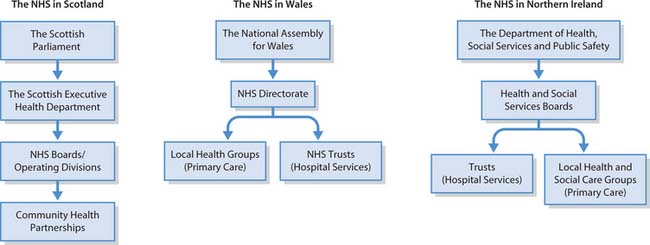

The structure of the NHS has been reformed on a number of occasions, with different structures operating in Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland.

Types of health and social care provision

The provision of health and social care services is divided into:

Statutory services are those controlled by Acts of Parliament (see Ch. 6). There are some aspects of care provision that are non-statutory, i.e. not governed by Acts of Parliament. In addition, certain supporting services are provided by voluntary agencies or charitable organizations, such as befriending schemes. A scheme such as this might, for example, involve a lonely older man living by himself having a volunteer drop in to see him on a regular basis to make sure that he is alright and that he does not become too isolated (Box 3.2, see p. 74).

[Resources: MIND – www.mind.org.uk/Information/Factsheets/Suicide Available July 2006; Royal College of Psychiatrists 2004 Older men less likely than younger men to kill themselves (press release) – www.rcpsych.ac.uk/press/preleases/pr/pr_586.htm Available July 2006]

Suicide in older men

In a Royal College of Psychiatrists (RCP) press release (2004), Professor Snowdon reported that, in the UK, men in their mid-fifties are less likely to kill themselves than their fathers and grandfathers. However, suicide in older men is twice the rate in older women.

Private hospitals, care homes and clinics also provide services to people who, in addition to paying taxes, choose to pay directly or indirectly through private health insurance for private healthcare services.

The aforementioned dynamic nature of health and social care services is illustrated by the fact that many statutory, non-statutory, voluntary sector and private sector organizations are working together in increasing numbers in order to provide a range of services to meet the complex health and social care needs of a growing number of people.

The differences between the various types of service provision are outlined below.

Statutory services

Statutory services are those provided by virtue of laws made in Parliament (see Ch. 6) and which are funded, managed, run and evaluated by central government. This is carried out via the:

However, not all statutory services are delivered directly by government organizations or agencies, and not all services are delivered with staff and patients/clients on a face-to-face basis, e.g. telephone contact with NHS 24 in Scotland and NHS Direct in England. Many services are contracted out and delivered by non-statutory agencies. Examples of non-statutory agencies providing statutory services include:

[Resource: www.dh.gov.uk/PolicyAndGuidance/OrganisationPolicy/SecondaryCare/TreatmentCentres]

Treatment centres

A relative who lives in England tells you she is having her cataract operation at last, and it will be done in one of the new treatment centres. She asks you if there is one near you and what you know about the centres.

The NHS Plan (DH 2000) sets out various targets, e.g. reducing waiting times for operations, by which the government hopes to be able to claim that improvements in the nation’s health and increased value for money have been achieved (Box 3.4).

The NHS Plan … targets – waiting times for surgery

Target – Patients will be admitted for treatment within 18 weeks from referral by their General Practitioner (GP).

Alice, who has pain and reduced mobility due to arthritis, has been told that she will be put on the waiting list for a hip replacement but is likely to wait for at least 12 months for surgery.

Non-statutory services

Non-statutory services cater for specific client groups such as:

These services include the provision of day centres, care homes, low-cost housing, carer support (e.g. those caring for someone with Alzheimer’s disease), etc. The services offered can be physical care, psychological care, the provision of information and support, or a combination of all three. Another aspect of their activity may be to lobby for improved statutory services and some do this to great effect. Many of the organizations which provide these services, e.g. Sue Ryder Care and the Royal National Institute of the Blind (RNIB), are increasingly being involved in partnerships between the NHS and local authority Social Service Departments in response to government initiatives such as Partnerships for Care in Scotland (Scottish Executive 2003) and The New NHS: Modern, Dependable in England (DH 1997).

Voluntary or charitable provision

Many of the services provided by voluntary and consumer groups tend to be offered by self-help, disease-based or disease-focused groups. Examples of groups that pro-vide support for carers and individuals include:

As well as providing support and information for patients/clients and their families, these groups may also work to improve care and assistance provided by statutory services.

Private sector

Private healthcare is provided by private companies who have traditionally offered a range of mainly short-term hospital care. Increasingly, private healthcare providersalso supply GP services (e.g. GP-Plus launched in Edinburgh in 1999) as well as health screening and elective surgery (e.g. cataract removal, termination of pregnancy and hip replacement). Some people see the growth in private healthcare provision as a means of replacing statutory health services due to the inability of the NHS to cope with demand for these services, e.g. termination ofpregnancy. In addition to private companies, other providers include not-for-profit companies or provident associations, e.g. BUPA, which re-invest monies into services.

In England, and increasingly in Scotland and the other countries of the UK, where the statutory services are unable to deal with long waiting lists for hospital treatment, health authorities are allowed by government to send their patients to receive treatment in private sector hospitals. The demand for private healthcare services is not uniform across the UK. Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland have fewer private sector hospital beds per head of population than in England. Interestingly, the Scottish Executive Health Department bought an underused private hospital in Glasgow in order to meet demand and to relieve the pressure on waiting list targets in Scotland. In 2001, the NHS in England took similar action by purchasing a private heart hospital in London. Some health authorities in England have also begun to send patients abroad for treatment as a way to meet waiting time targets set by central government.

Government policy forcefully states that the divisions that existed between the statutory and private sector health service providers should be brought to an end and ‘so harness the capacity of private and voluntary providers to treat more NHS patients’ (DH 2000, p. 96). This working relationship and changed approach to the provision of healthcare services is a radical departure from previous Labour Government policy but it is an acknowledgement that private sector healthcare provision does, indeed, meet many needs that the NHS is unable to, as well as officially recognizing the fact that NHS ‘already spends over £1 billion each year on buying care and specialist services from hospitals, nursing homes and hospices run by private companies and charities’ (DH 2000, p. 96). The changes outlined in The NHS Plan have been superseded by the NHS Improvement Plan: Putting People at the Heart of Public Services (DH 2004) which states, ‘To support capacity and choice by 2008, independent sector providers will provide up to 15% of procedures on behalf of the NHS’ (p. 10).

Box 3.5 outlines a situation in which various health and social care providers might have a contribution to make.

Meeting Alice’s needs

Alice, as you will remember, is on the waiting list for hip replacement surgery for arthritis (see Box 3.4, p. 75). Recently she has had a couple of falls at home. Her hip is causing her a great deal of pain and this, in turn, restricts her movement. She is unable to go to the shops or to do many things that she would normally do, but for the pain and fear of falling, such as having a bath, cooking and meeting friends. Alice tells her family that she is increasingly isolated and this is getting her down and making her feel depressed.

Alice has a set of needs that, by itself, the healthcare system is not able to meet. She has:

The hip replacement will take up to 12 months to be done. Meanwhile Alice, who is now feeling very vulnerable, has a variety needs that require to be met in order to maintain her dignity, improve her quality of life, prevent further deterioration of her mental state and prevent other health problems from developing. The health service has a statutory obligation to look after Alice’s healthcare needs but not her social care needs. These have to be met by other organizations and agencies working independently and together.

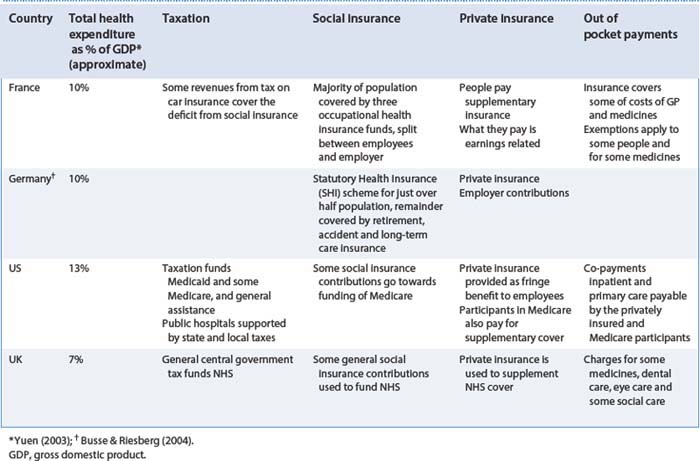

Comparisons of the UK funding model with other systems

Levitt et al (1999) argue that a country’s health and social care provision reflects the national priorities of that country in many ways. These may include historical circumstances to meet particular health needs; for example, malaria control versus a tuberculosis vaccination programme, compared with the latest portable bone scanner versus a community mental health nurse.

All governments have to make choices about financing healthcare (Box 3.6). They also spend more than they would like to and complain of waste and poor control, and all are concerned for the future. In 2005, for example, many Southern African countries were forced to make difficult choices between funding treatment for HIV/AIDS versus treatment for malaria; this is a particular concern when societies find it difficult to accept that a problem with HIV/AIDS actually exists. According to Levitt et al (1999), the funding arrangements for healthcare and social care vary markedly between countries. They go on to state that: ‘In all developed countries there is a mix of state funding, insurance and direct payments … A major concern of all governments is to control costs whatever their methods of financing healthcare’ (p. 241).

Difficult choices

Your aunt has a heart condition (irregular rhythm) and she is extremely distressed and worried about dying. The primary care trust (PCT) is unable to fund her non-urgent treatment in the current financial year because it has run out of money. The local newspaper published the story, which has since been picked up by the national newspapers who are calling for the Health Minister to put pressure on the PCT to re-examine its priorities.

The UK opted for a direct payment system via general taxation by central government (Table 3.1). However, some people choose to pay private health insurance to augment their healthcare provision. This enables them to make choices about when, where and who will provide the healthcare service needed at a particular time. Being able to make such choices allows those individuals to be treated more quickly for non-urgent conditions as opposed to joining a waiting list.

The funding for social care also varies. In the UK, central government allocates the bulk of resources to local authorities with small amounts of additional funding coming from local taxation (council tax). However, central government and local authorities do not fund all social care. For example, a person who needs to go into a care home but has a certain level of financial resource will be required to pay in full or contribute to this service. A person living in a care home would, however, receive an allowance for nursing care that requires the services of a registered nurse. Where a person has limited money or savings, the local authority would pay the care home fees. People living in England who need assistance with personal care such as washing and dressing are required to pay for these personal services. The situation in Scotland is completely different, as the Scottish Executive finances the cost of personal care.

In 1949 the amount of money spent by the UK government on healthcare was estimated to be just under £10 billion (Yuen 2003). This compares to healthcare spending in 2004/2005, estimated at just over £67.4 billion, which is set to rise to £90 billion by the year 2007/2008 (DH 2004). Interestingly, spending on the health service in Scotland in 2004 was £7.8 billion for the treatment of five million people and is expected to rise to £9.3 billion in 2007/2008 – nearly as much as it cost for the whole of the UK when the health service was first started (Audit Scotland 2004).

The National Health Service

This part of the chapter focuses on how the NHS is structured in the four countries of the UK and functions of the various bodies within them.

The original aims of NHS (Ministry of Health 1946) were the promotion of a comprehensive health service designed to secure improvement in the:

These remain the aims of the NHS today and encompass care for the whole population (for all UK countries) from ‘the cradle to the grave’, providing services for acute and chronic (long-term conditions) illness in a variety of settings, such as hospitals, day hospitals, health centres, home care, walk-in centres, telemedicine (NHS Direct, NHS 24) and so on. However, the healthcare needs of the population when the NHS was first introduced were very different from the healthcare needs of today’s population. Since its inception the structure of the NHS has changed and will continue to do so.

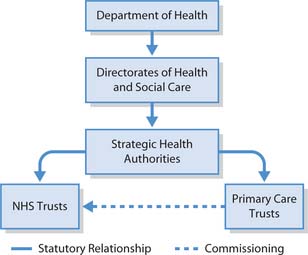

Structure and function of NHS

The structure of the NHS in England is the most complex in the UK. This is, in part, due to the population and the geographical size of the country. The NHS system is fundamentally divided into three tiers in the four countries (Figs 3.1, 3.2) but there are some differences in NHS structure between countries. Further information about these differences in structure, health and other policies and services is available from the appropriate government website (see ‘Useful websites’, p. 95). The three-tier system reflects the shift in government thinking, which aims to reduce centralization by devolving decision-making to the professionals who are delivering the services and the patients/clients receiving them.

Fig. 3.2 The NHS in Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland (reproduced with permission from Merry 2004)

In England, the Department of Health is charged to ensure that the health of the population is looked after; if necessary, they bring Bills before Parliament to ensure that the appropriate legal framework is in place for meeting their responsibility. The Secretary of State and the health ministers within the Department of Health have the responsibility to ensure that the NHS, social care and public health services work together to meet the nation’s health and social care needs.

The Secretary of State and health ministers are advised by a group of national clinical directors and key specialists covering the full range of health service provision, e.g. mental health, children, primary care, older people and cancer. These positions are mirrored in the other countries of the UK.

Central government, in its various forms, is the enacting, funding and driving force for provision of services. The government develops strategies and plans for the health of the nation, legislates as to how this will be done and provides the funding that enables various professional and non-professional groups to deliver services to the population.

The intermediaries between central government and those who deliver healthcare are the Strategic Health Authorities (SHAs) in England (Box 3.7), Health Boards in Scotland, Regional Health Authorities in Wales and Health and Social Services Boards in Northern Ireland. These bodies plan the delivery of services at a regional level. Currently in England the primary care trusts (PCTs) commission services from NHS Trusts and both PCTs and NHS Trusts provide healthcare directly to patients/clients in the community and hospital. NHS provision is divided into primary, secondary and tertiary care (see pp. 79–82), with various forms of intermediate care used to bridge the gap between primary and secondary care.

Box 3.7 Strategic Health Authorities

There are currently 10 SHAs in England. This number was reduced from 28 to 10 in 2006. SHAs are responsible for developing strategic plans for improving local health services in specific geographical areas; for example, East of England SHA covers Norfolk, Suffolk, Cambridgeshire, Essex, Bedfordshire and Hertfordshire. SHAs are structurally located between the Department of Health and the primary and secondary providers. SHAs also negotiate and help to find solutions to local problems and make sure that local service providers are answerable for the services they provide and increase the capacity of local health services in order to extend services.

The SHAs are responsible for monitoring and measuring the performance of NHS Trusts and PCTs against government targets and for ensuring that the government’s national priorities are integrated into the work of the PCTs and the NHS Trusts, thereby being concerned with primary healthcare and community services run by the PCTs and the acute hospital services run by the NHS Trusts.

Primary healthcare

PCTs and GPs and other members of the primary healthcare team provide a range of primary healthcare services directly to people living in the community. The PCTs also take lead responsibility for developing and sustaining partnerships with other agencies, including local authorities, voluntary organizations and private providers.

For most people in the UK their first contact with the health service, irrespective of where they live, has, up until relatively recently, been the GP. Traditionally, GPs and other healthcare professionals working from the same base, such as the GP’s premises or a health centre, have provided most community-based primary healthcare services. The other healthcare professionals who may be part of the MDT working from health centres include:

Box 3.8 Core functions of community practitioners and health visitors

According to the Department of Health (2003) there are three core functions that underpin primary care nursing in the UK and six principles that run through all public health work.

Dentists, dental hygienists, optometrists and podiatrists also provide primary healthcare services in the community.

The services offered by primary healthcare teams may also include health protection in schools, sexual health and prevention of teenage pregnancy; the prevention of falls in older people; nurse-led mobile outreach services to rural communities; working with homeless people; support for cardiac rehabilitation and Asian women with diabetes; heart disease prevention programmes, etc. Community mental health nurses often work in health centres to provide nursing interventions for people who may be experiencing mental distress, or what the NHS in England’s website calls ‘less complex and severe mental health problems…for example, depression, stress or anxiety’ (NHS England 2005).

All of these services involve health visitors or community practitioners working with other healthcare professionals and thereby emphasize the important contribution of nurses in meeting a community’s healthcare needs, developing services, improving health and reducing inequalities (Box 3.9).

Working with others to improve health

A community mental health nurse is interested in working with people who are experiencing mental distress and may offer services such as anxiety management, cognitive behaviour therapy for people who experience depression and group therapy sessions. In the health centre they may work with other community mental health nurses, e.g. in group work, but they may also work with other professionals such as psychiatrists, occupational therapists, art therapists, complementary therapists, alternative medicine practitioners and speech and language therapists.

Newer ‘first access’ routes

In response to the pressures on GP services and new GP contracts, different models and points of first access to healthcare services have been developed, particularly with ‘out-of-hours’ services. Increasingly, people’s first contact with the NHS will be through a telephone health service – NHS Direct in England and NHS 24 in Scotland, or a walk-in centre.

For example, the telephone health services, NHS Direct and NHS 24, offer a 24-hour nurse-led telephone health information and advice service, with further information and advice available online (NHS Direct – www.nhsdirect.nhs.uk). These services provide a single access point to the NHS out-of-hours services.

The development of nurse-led walk-in centres (WICs) in England has also raised the profile of the work of nurses in community settings. Nurse-led WICs differ from health centres, which are led by GPs and nurses. No appointment is needed and WICs offer a quick, convenient way to access a range of NHS services, including free consultations, minor treatments, health information and advice on self-treatment. WICs have close links with local GPs, ensuring continuity of care for patients/clients (Box 3.10).

Box 3.10  EVIDENCE-BASED PRACTICE

EVIDENCE-BASED PRACTICE

[References: Chapple A, Sibbald B, Rogers A, Roland M 2001 Citizens’ expectations and likely use of a NHS Walk-in Centre: results of a survey and qualitative methods of research. Health Expectations 4(1):38–47; Salisbury C, Chalder M, Scott TM, Pope C, Moore L 2002 What is the role of walk-in centres in the NHS? British Medical Journal 324:399–402. Online: http://bmj.bmjjournals.com/cgi/content/full/324/7334/399 Available July 2006] [Resource: Jackson CJ, Dixon-Woods M, Hsu R, Kurinczuk JJ 2005 A qualitative study of choosing and using an NHS Walk-in Centre. Family Practice 22(3):269–274]

Walk-in centres

Using a postal survey, face-to-face interviews and a focus group, Chapple et al (2001) sought to ascertain which groups would use walk-in centres, under which circumstances and to what extent these centres would meet their healthcare needs. In the abstract of the article, Chapple et al conclude that:

Walk-in centres without GPs and with limited services will disappoint the public. It is important that walk-in centres are evaluated and attention paid to ‘local voices’ before additional money is allocated for such centres elsewhere.

According to Salisbury et al (2002), the key features of NHS walk-in centres are:

Student activities

Intermediate care

The intermediate care service is the response by the Department of Health to the National Beds Inquiry consultation exercise which focused on services for older people, as they were the largest group of users of hospital services (DH 2001a). The consultation found that there were insufficient hospital beds in the right places in order to meet the needs of this group of patients.

Implementation of an intermediate care service would relieve pressure on acute hospital beds and reduce both the length of stay in hospital and hospital waiting times. The key elements of intermediate care services (DH 2001a, p. 12; HSC 2001/003) include:

Intermediate care is organized by the PCT and is designed to blur the gap between community care and hospital care (primary and secondary care services) with the intention of acute hospital-based health practitioners working in the community and vice versa. This means that the most appropriate staff in the most appropriate setting, e.g. community hospital, would provide patients/clients with ‘seamless care’.

Examples of how intermediate care has been implemented include a Community Assessment, Rehabilitation and Treatment scheme in Rotherham, which is run by a MDT (comprising nurses, physiotherapists and occupational therapists) for patients who have been discharged from hospital after a period of acute care or who have not required hospital admission. Another service provided by the Bedfordshire and Luton Community Trust for early discharge from hospital provides rehabilitation for patients who have had a stroke, chest infection or bone surgery (Box 3.11).

[Resources: Green J, Young J, Forster A et al 2005 Effects of locality-based community hospital care on independence of older people needing rehabilitation: randomized controlled trial. British Medical Journal 331(7512):317–322; Young J, Robinson M, Chell S et al 2005 A whole system study of intermediate care services for older people. Age and Ageing 34(6):577–583]

Intermediate care

Intermediate care has obvious advantages for both patients and the NHS. Patients can leave hospital sooner or their admission can be prevented by the timely intervention of a fast response specialist team at home.

Secondary and tertiary healthcare

Secondary healthcare provision centres on district general hospitals (DGHs) which provide services that include general medicine, surgery (other than specialist services), orthopaedics and child health, as well as midwifery services and some inpatient mental health services (see p. 82). DGHs also offer emergency care in Emergency Departments (also known as Accident and Emergency [A&E] Departments). Reasons for attending the Emergency Department include:

Nurse-led minor injuries units attached to traditional Emergency Departments are increasingly available and offer specific services and reduced waiting times. People using the Emergency Department may be treated and discharged, given immediate treatment and admitted to a ward for further care, or transferred to a specialist unit.

Secondary healthcare is usually acute and can be either elective or emergency care and usually takes place in an NHS hospital. Elective care is planned specialist medical or surgical care, which usually follows referral from a primary or community health professional, most often the GP. Examples of elective care include a hip replacement operation or a course of chemotherapy for cancer. An elective care patient may be admitted either as an inpatient or a day case patient, or they may attend an outpatient clinic.

Increasingly, patients/clients are benefiting from quicker and more convenient elective services that include:

Other examples of secondary care services include specialist services for mental health, learning disability and older people.

Tertiary healthcare services are hospital-based services such as neurosurgery (brain surgery), cancer care, etc. for a patient/client with an unusual condition, or needing highly specialized treatments in a specialist centre such as a teaching hospital or regional centre.

NHS Trusts

Within each area served by the Strategic Health Authority there are several types of NHS Trust. These include:

Acute Trusts

Acute Trusts run hospitals and have the responsibility for ensuring that hospitals provide high quality care and that public money is used efficiently. They also determine strategy for developing the hospital in order to improve services.

They employ a sizeable portion of the NHS workforce, including clinical staff (e.g. nurses, midwives, doctors, pharmacists, medical scientists, physiotherapists, radiographers, speech therapists, occupational therapists, psychologists, etc.) and non-clinical staff (e.g. managers, accountants, receptionists, secretarial staff, porters, cleaners, and maintenance, security and catering staff).

Some of the Acute Trusts are tertiary regional or national centres for more specialized care. Others are attached to universities and part of their role is to provide training for health professionals. Acute Trusts can provide services in the community; this may be provided in the person’s home, clinics or health centres.

Foundation Trusts

These are NHS hospitals run by local managers, staff and members of the public, and are customized to meet the needs of the local population. Foundation Trusts have more freedom to spend money and to decide about how they will be run, and can also raise money from both the public and private sectors within borrowing limits. They have come to represent the government’s commitment to decentralization of control of public services although they remain within the NHS. The numbers of Foundation Trusts in England are expected to increase.

Mental Health Trusts

Mental Health Trusts provide health and social care services for people with some mental health problems. Such services can be provided through GPs or other primary care services, and may include counselling or community and family support or general health screening. Mental Health Trusts and local authority Social Service Departments also provide more specialist services such as psychological therapies or services for people with severe mental health problems.

People with mental health problems may require care in the mental health unit (Psychiatric Unit) of the local DGH or in more specialist units such as regional secure units and special hospitals (e.g. Broadmoor). The type of services they provide include in-depth assessment such as that required by the courts, psychological therapies or specialized medical treatment for conditions that include severe anxiety problems or psychotic illness, e.g. schizophrenia.

In common with other mainstream health services, mental health services are also delivered in primary, secondary and tertiary settings. Modernization of mental health services was one of the government’s key priorities (DH 2000). This set out a 10-year programme to improve standards of care; for example, to create an extra 500 secure beds in 2004; more than 320 24-hour staffed beds; 170 assertive outreach teams and access to mental health services 24 hours per day, 7 days per week for those individuals with complex mental health needs. The government’s priority at this time was that people with severe and enduring mental health problems were provided with services that were more responsive to their needs.

Care Trusts

Care Trusts operate across both health and social care. They may provide a whole range of services including primary care, social care and mental health services. Care Trusts are formed when the local NHS and local authorities agree that working closely together is necessary or that it would benefit local care services. A Care Trust can include combinations of mental health, primary care and social care services, depending upon local need. Currently there are only very few Care Trusts but it is expected that others will be formed.

Ambulance Trusts

There are currently 12 Ambulance Trusts in England and they provide emergency access to healthcare, such as through paramedic first response vehicles or emergency ambulances staffed by paramedics. The number of Ambulance Trusts was reduced in 2006 through the merger of many existing Trusts. Requests (999 calls) for attendance of an ambulance are prioritized – the most urgent being when the condition of the person is life threatening. If necessary, the patient’s condition is stabilized, e.g. intravenous fluid replacement, administration of ‘clot busting’ drugs (thrombolytics), before onward transport to an Emergency Department or specialist centre; this is usually by road but in urgent cases it might be by air ambulance. Ambulance Trusts are also responsible for transporting many patients to hospital for non-urgent treatment.

Children’s services

The structure of the health service aimed at meeting children’s healthcare needs is also changing. Reasons for the changes are similar to those driving the changes in adult services and other services, and they too are commissioned and purchased by PCTs. Children’s health services are aimed at meeting the diverse range of healthcare needs and providing a more integrated service between primary, secondary and community care organizations. Services generally focus on infants, children and young people under the age of 16.

Children’s Trusts

Increasingly, services for children are integrated within Children’s Trusts, which were established by the Children Act 2004 (see Ch. 6) (Box 3.12). Children’s Trusts include input from local authority Children’s Services Departments (created from the Education Department and Social Services Department), various healthcare services and other agencies such as the police. Most local authorities have a Children’s Trust and it is the local authority that is the lead partner in this arrangement. By bringing these services together under one organizational structure it is hoped that children and families will receive a much better service more able to meet their needs (Box 3.13).

[Resources: Children Act 2004 – www.opsi.gov.uk/acts/acts2004/20040031.htm; Children Act 2004 (Explanatory notes) – www.opsi.gov.uk/acts/en2004/2004en31.htm; Victoria Climbié Inquiry – www.victoria-climbie-inquiry.org.uk]

Children’s Trusts result from the legislation that followed the inquiry led by Lord Laming into the death of Victoria Climbié (Victoria Climbié Inquiry 2003) (see Ch. 6). The report highlighted many deficiencies in the communication and working arrangements between the various statutory and voluntary agencies – social services departments, Metropolitan police child protection teams, the NSPCC and hospital services.

Children’s Trusts are part of the broader measures planned in the government initiative Every Child Matters: Change for Children (Department for Education and Skills [DfES] 2004). Children’s Trusts were set up to remedy the deficiencies mentioned above and are intended to help local authorities, and their partners, to meet their statutory duties as set out in the Children Act 2004 (the legislative framework for the Every Child Matters programme) to cooperate and improve children’s well-being. All local authorities in England are expected to have established Children’s Trusts, or their equivalents, by 2008.

[Resource: DfES/DH 2004 NSF for children, young people and maternity services. Disabled children and young people and those with complex health needs (see ‘Markers of Good Practice’, p. 6). Online: www.dh.gov.uk/assetRoot/04/09/05/56/04090556.pdf Available July 2006]

Akasma – a little girl with complex needs

Akasma has a learning disability and additional physical problems. She has no verbal communication but is able to communicate with signs and a communication book. Akasma has difficulty eating solid food and is fed through a gastrostomy (see Ch. 19). Akasma’s mobility is very limited and her family have a wheelchair for her. She needs help from community nurses, physiotherapist, occupational therapist, dietitian and speech and language therapist.

Prior to the inception of the Children’s Trust, Akasma’s mum had to make contact and negotiate with many professionals to have Akasma’s needs assessed and access the services required to meet these needs. Looking after a child with complex health needs is very tiring and stressful, and having to talk with a range of professionals only added to the burden. Problems arose because the various professionals and helpers did not always communicate with each other and had very different approaches to the way that they delivered services.

The key integrated services within a Children’s Trust include:

PCTs will be able to delegate functions to theChildren’s Trust, and are able to share funds with the local authority.

Other health services for children include ‘ambulatory care centres’. These centres include facilities that provide day care procedures, assessment beds, general outpatients, minor accident and emergency services and community-based services.

Children in hospital

As for most people, where possible, the best place for children to be cared for is at home. However, children also require hospital treatment and the quality of care that they receive should be targeted to meet their needs – in hospital, their own home and the community. Action for Sick Children, a UK charity whose purpose is to ensure that sick children receive the best quality of care possible, drew up a document outlining the rights that children should be entitled to should they be admitted to hospital. The document developed by Action for Sick Children has been adopted as the Charter for Children in Hospital by the European Association for Children in Hospital (EACH) and sets out a number of good practices when caring for children in hospital. These are:

Every Child Matters programme

The Every Child Matters: Change for Children (DfES 2004) is an approach aimed at promoting the well-being of every child (from birth to age 19 in England) whatever their background or circumstances. The Green Paper Every Child Matters (2003) acknowledges the past failings of the various agencies to protect vulnerable children and sets out policies to improve children’s lives. The Green Paper states:

‘There was broad agreement that five key outcomes really matter for children and young people’s well-being:

(Every Child Matters, p. 14, © Crown Copyright 2003)

Other innovations in children’s well-being

Additional innovations in children’s well-being include the Sure Start scheme, Diana Nursing Teams and DebRA Children’s Nursing Service (Box 3.14).

Innovations

A small selection of innovative schemes that improve the lives of children and their families are discussed here but many other ‘ground breaking’ schemes operate throughout the UK.

The Sure Start scheme aims to ensure that children under 4 years of age who live in disadvantaged areas get the best start in life. It involves a number of different agencies working together to develop projects to support the physical, intellectual and emotional development of young children. Projects include working with and supporting parents and helping them with childcare, playing with their children, providing early years education in children’s centres, etc. The Sure Start scheme is also seen as contributing to the Every Child Matters: Change for Children (DfES 2004) programme through:

Diana Nursing Teams were set up in 1999 by The Diana Memorial Committee. The teams provide specialist nursing care and practical help for very sick children and their families. In Scotland, the approach taken was to fund people to undertake community children’s nursing programmes. One such Diana Nursing Team operates from Addenbrooke’s Hospital in Cambridge. This is a nurse-led MDT and includes:

The team provides help for children and their families who have life-threatening or life-limiting conditions and who may need long periods of treatment, progressive conditions which may or may not be curable, and other severe medical conditions that can cause weakness and other complications (Cambridge University Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust 2005).

DebRA Children’s Nursing Service is an example of a UK charitable organization that works on behalf of people who have the genetic skin blistering condition epidermolysis bullosa (EB). Parents whose children were affected by EB set up the charity. The aim of the nursing service is to offer specialist nursing care to families and health professionals with a particular focus on skin and wound care, feeding, pain relief, genetic counselling and working with St Thomas’ Hospital in London to coordinate prenatal diagnosis.

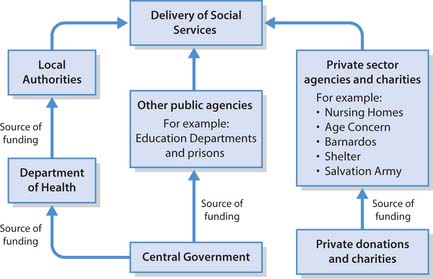

Social care provision

This part of the chapter outlines the structures and functions of some of the groups that provide social care. Historically, social care has not been a function or a responsibility of the healthcare system but of local government. These authorities organize the provision of social care under the auspices of social services departments (known as social work departments in Scotland). Many of the services offered by the social care sector nowadays are often the result of joint ventures between the health service, other statutory services, such as education and the criminal justice system, and non-statutory organizations and the voluntary sector (see p. 86 for examples of specific projects). Multidisciplinary and multiagency working is central to social care provision.

Structure and funding of social care provision

A diagrammatic representation of the structure and funding of social care provision is provided in Figure 3.3.

There is some confusion about what ‘social care’ means because some authors use the terms ‘social care’, ‘social services’ and ‘social work’ interchangeably, but they are, in fact, very different. Even when there is agreement as to what the different terms mean, the way in which services are delivered and by which organization may vary across the UK. As Alcock (2003, p. 97) explains:

Social services is the generic term used to refer to the provision of both social care and social work and in particular the provision of this by public agencies to all those who might need such services within a defined area. For the most part, this is provided in the UK by departments or sections of local authorities although in Northern Ireland it is administered jointly with health services by joint boards and trusts. All local authorities are required to provide such personal social services (PSS) and in general do so through a social services department (SSD), in Scotland called social work departments. Social services includes social care and social work but the term also generally encompasses a wider range of services provided for local people on an individual or community basis including community work, welfare rights advice and even financial support. Social services may also be provided by other agencies such as health service bodies or voluntary sector organizations.

Social care, specifically, is the term used to describe the support offered by society to sick, vulnerable or disabled people who are unable to provide fully for themselves (Alcock 2003). Social care is expanded on by Alcock (2003, p. 97) as:

… the provision of individual support and attendance to vulnerable sick or disabled people who are unable to provide fully for themselves. The support is provided by other members of society, sometimes on an unpaid basis (generally by family members), sometimes on a paid basis by social care workers; paid workers may provide care at a person’s home or in a residential establishment. Social care is, of course, provided to children but in this context the term is generally used to refer to the provision of support to adults.

Moreover, the Local Government Association and the Association of Directors of Social Services (2003) have challenged the traditional definition of social care that sees social care narrowly defined as just providing health and social services for vulnerable people. Both organizations present their ‘vision for social care’ as incorporating a wide range of services that includes what people say they want, e.g. independence, their own home, a decent income, social relationships, and to include housing, employment, leisure, regeneration and transport in the range of services that should be covered by a redefined understanding of social care as it relates to service provision for older people.

The vast amount of money spent on social care provision in the UK reflects the number of people employed in the sector and also the number of people who use the service, as well as the range of services required to meet the social care needs of vulnerable people. In England alone in the financial year 2004/2005 the breakdown was:

(After Platt 2004).

In addition, the vast majority of voluntary sector provision receives funding from public donations and charities (see Fig. 3.3).

According to the Commission for Social Care Inspection (2004, p. 1), in England social care covers:

… all the different types of support that people may need in order to live as independently, safely and fully as possible. It covers a huge range of services including residential care homes, meals on wheels, fostering services and drop-in centres for disabled people. It doesn’t include medical care, but many social care services operate alongside health services – such as where an older person returning home after a hospital stay may require nursing visits and help around the house and with shopping.

Social care provision by the voluntary sector

Voluntary sector organizations receive money from central government and local authorities for specific projects. For example:

Social work definition and roles

The International Association of Schools of Social Work (IASSW) and the International Federation of Social Workers agreed a global definition of social work in 2001:

The social work profession promotes social change, problem solving in human relationships and the empowerment and liberation of people to enhance well-being. Utilising theories of human behaviour and social systems, social work intervenes at the points where people interact with their environments. Principles of human rights and social justice are fundamental to social work.

The British Association of Social Workers has adopted this definition.

The six key roles for social workers are identified by the National Occupational Standards for Social Work (Skills for care/TopssEngland 2002) (Box 3.15).

[Resources: Skills for Care/TopssEngland 2002 The National Occupational Standards for Social Work (p. 12). Online: www.topssengland.net Available September 2006; A comprehensive view of the complex role of social workers – Social Work in Wales – is online at www.allwalesunit.gov Available July 2006]

Key roles of social workers

All nurses in every setting will have contact with social workers as multidisciplinary and multiagency collaboration increases.

Social care workers

Social care may be provided by paid or unpaid members of society, e.g. social workers, social care workers, family members and significant others.

Social workers are employed by local authorities to identify adults or children who might be in need of individual support or protection as a result of their social or family circumstances and, where possible, aim to provide this support or, more generally, to assist their clients in securing support from other agencies. For their adult clients, social workers generally work in this enabling role. Social workers are professionally accountable for their practice. From April 2005 an individual is not entitled to use the title ‘Social Worker’ unless they are registered with one of the following four regulatory bodies:

As outlined by the Scottish Social Services Council (2005), the four regulatory bodies have similar responsibilities, including:

As with registered nurses, social workers and other professionals are unable to meet all of the needs of their clients. Many social workers work as part of a team that may involve social care workers or support workers. Unlike social workers, support workers are not currently registered or regulated and work in many intermediate care services and social care settings, e.g. rehabilitation assistants, home care support workers and early discharge workers. A difficulty with the title ‘support worker’ is that there is no agreement on what the role means or entails. The diverse care settings in which support workers are employed, particularly in intermediate care, mean that their roles tend to vary according to the service and the setting. A parallel ambiguity exists with the definition and role of support workers in healthcare settings, where support worker is an umbrella term covering roles such as healthcare assistants, nursing auxiliaries, therapy assistants and clinical support workers (NHS Careers 2005).

Support workers are employed by a variety of statutory and non-statutory organizations. Examples include the following:

Social care and vulnerable groups

Adult clients form the main groups that need social care, e.g. older people (47%), children (23%), people with learning disabilities (14%), people with a physical disability (7%), people with mental health needs (5%), ‘central strategic’ 1% and ‘others’ 3% (DH 2002).

Services for older people

Services offered for older people focus on caring for people in their own homes, promoting independence and reducing time spent in hospital. Of course, how independence is promoted and achieved depends upon the context in which people are being cared for, but it is vitally important that there is close collaboration between health and social care workers when delivering older people’s services. This is particularly the case when services include homecare, meals provision, respite and day care and cleaning services. For many people, being able to look after themselves is fundamental to their independence, and having control and being able to make choices about how people look after themselves is crucial. The promotion of self-care is one way that social care staff and nurses can help people to maintain their independence and dignity.

Older people are the largest group of patients/clients using the NHS. According to The NHS Plan (DH 2000), people aged over 65 years account for two-thirds of hospital patients and 40% of emergency admissions. As was stated previously, many older people are in hospital inappropriately. The NHS Plan sets out a major package of investment to improve the standards of care and services for older people. Its four objectives are aimed at putting older people at the centre of service delivery. They are:

A National Service Framework (NSF) for Older People, to be implemented through local health and social care partners, set standards for eight areas aimed at improving services for older people living at home, in care homes or hospitals (DH 2001b). The eight areas are:

Examples of how some of these standards are being met include:

Services for children

Social workers collaborate with other professionals, within statutory frameworks, to safeguard all children and to identify vulnerable and ‘at-risk’ children. In England and Wales, local safeguarding children boards (LSCBs) – comprising local authorities, NHS bodies, the police and others – coordinate the activities of the various agencies to ensure that they work effectively to safeguard children.

An interagency child protection conference can place a child’s name onto the child protection register if they decide that they are at continuing risk of significant harm such as injury, abuse or neglect. The confidential register is kept by the Social Services Department but is available to professionals involved in safeguarding children, e.g. social workers, health visitors, doctors, teachers, police officers, etc.

In most instances involving children, social workers have lead responsibility for undertaking assessment of children’s needs as well as assessing their parents’ ability to care for them. In the majority of cases children will remain at home with social services coordinating the plan and interventions to safeguard the child as well as setting out the respective roles and contributions of parents, family members, professionals and other agencies. They will, where necessary, support parents to increase their skills such as through parenting classes (see Sure Start, p. 84).

Sometimes, as a last resort, the child protection team will need to obtain a court order authorizing the removal of the child from the family home in order to safeguard their welfare. Where a child has been removed from home as part of a care order, the social worker ensures that appropriate arrangements are in place for the care of the child with their participation as well as that of other agencies, e.g. the police, school and health services, and the Children’s Panel in Scotland. This partnership, wherever possible, will also involve the child’s parents.

Social workers may also work with and support families who have a child with a physical disability in order to minimize the impact of the disability and help them to reach their potential to lead as full a life as possible. This may involve organizing short-term breaks with foster parents or, where necessary, care in a residential unit or helping with school and leisure activities, e.g. swimming, youth clubs, etc.

Services for people with a learning disability

The government estimated that there are 210000 people with severe learning disabilities in England and about 1.2 million people with a mild or moderate disability (DH 2001c). Learning disability is defined in Valuing People: A New Strategy for Learning Disability for the 21st Century (DH 2001c) as the presence of:

The equivalent publication in Scotland is The same as you? A Review of Services for People with Learning Disabilities (Scottish Executive 2000).

Services for people with learning disabilities in the UK have gradually moved from large hospitals into the community. The government’s main aim for service provision for people with a learning disability is the promotion of independent living as part of their local communities (DH 2001c), e.g. the County Council joins with the local NHS and other statutory and voluntary agencies to form a Learning Disability/Difficulty Partnership Board in order to improve the services provided for people with learning disabilities. It is especially important to put the person at the centre of care planning so that they have both choice and control over what they do. These services may include:

[Resource: The Foundation for People with Learning Disabilities – www.learningdisabilities.org.uk/index.cfm Available July 2006]

Services for people with a learning disability

The Foundation for People with Learning Disabilities – a learning disability charity – aims to promote the rights, quality of life and opportunities for people with a learning disability and works with a variety of statutory and non-statutory bodies in order to:

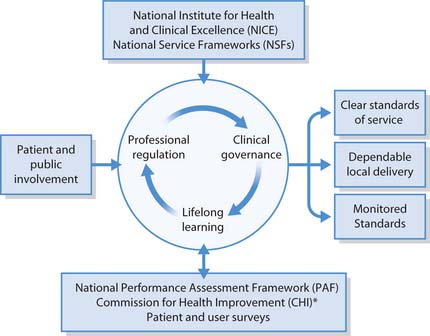

Providing high quality health and social care – quality issues

This section focuses on how standards of care and quality of health and social care services are promoted and maintained. Some aspects of clinical governance, including benchmarks for best practice and integrated care pathways (ICPs), clinical guidelines, NSFs, the Health-care Commission and patient/client involvement, are outlined.

The NHS Plan identified 10 core principles considered to be fundamental to modernizing and rebuilding the NHS. Principle 5 states, ‘The NHS will work continuously to improve quality services and to minimise errors’ (DH 2000). The issue of quality was not to be confined to clinical aspects of care but to patients’/clients’ quality of life and their whole experience of the healthcare system. This was set up, not only to improve services at every level, but also to ensure that patients/clients, no matter where they live, have equal access to the best quality of care.

Figure 3.4 illustrates the relationship between the mechanisms that are thought to underpin and inform the improvement of quality in the NHS.

At the centre of care delivery are health professionals. A health professional’s knowledge and skills must be adequately provided for during an initial period of preparation and be continuously updated throughout their careers. The various statutory regulatory bodies, such as the Nursing and Midwifery Council (NMC), are responsible for maintaining professional standards. For example, the NMC determines the level of competence and knowledge required to register as and practise as a nurse, midwife or specialist community public health nurse. They specify a pre-registration programme of education of a certain length that encompasses both theory and clinical practice. The NMC is also responsible for maintaining standards through Post-Registration Education and Practice (PREP) with the continuing professional development (CPD) and the PREP (Practice) standards (see Ch. 7). The quality of professional regulation is one of the factors that influence clinical governance.

Clinical governance

In order to provide high quality care and patient/client satisfaction, mechanisms, referred to as clinical governance, have been implemented. In common with the other countries of the UK, NHS Wales (2003, p. 207) defined clinical governance as:

… a framework through which NHS organisations are accountable for continuously improving the quality of their services and safeguarding high standards of care by creating an environment in which excellence in clinical care will flourish. Any efficient organisation has a system for improving quality; clinical governance is the system in the NHS. Information from complaints is an important part of this framework.

Many activities come under the umbrella of clinical governance: risk management, clinical audit, significant event audit, evidence-based practice, consulting skills, learning from complaints, involving patients and carers, and professional development.

Full coverage is beyond the scope of this chapter and readers are directed to Further reading (e.g. NHS Wales 2001) and to other chapters for specific components: Chapter 5, Audit, Evidence-based practice; Chapter 7, CPD; Chapter 9, Leadership; Chapter 13, Risk management.

Clinical governance is part of a Department of Health initiative that brings together professional regulation and lifelong learning in order to bring about improvements in the quality of the service provided.

According to Middleton and Roberts (2000, p. 16):

In essence, clinical governance can be seen as a quality framework which can be used to coordinate disparate quality initiatives and the process of change.

Benchmarking

Benchmarking is used to compare an organization’s care standards against those of an outside, but similar, organization, which is chosen especially for quality excellence. Benchmarking helps organizations to achieve ongoing improvements. It is a quality improvement tool that improves poor quality practice and allows organizations and practitioners to learn from each other and contributes to the effective use of resources.

Essence of Care (NHS Modernisation Agency 2003) provides benchmarks for best practice for health and social care practitioners in a number of areas such as self-care, etc. (Box 3.17).

Benchmarks for best practice in self-care

(NHS Modernisation Agency 2003 Benchmarks for principles of self-care, pp. 1–2)

Integrated care pathways

Integrated care pathways (ICPs) are documents which outline the care and treatment that a patient/client should receive from the first contact with health services until they leave that care (see Ch. 14). ICPs provide multidisciplinary outlines of anticipated care (care that professionals say patients/clients should get), placed in an appropriate timeframe, to help a patient with a specific condition, or set of symptoms, move progressively through a clinical experience to a positive outcome (Middleton et al 2001).

The development and use of ICPs can be viewed as a ‘tool’ that supports the implementation of clinical governance (Middleton & Roberts 2000).

ICPs assist healthcare professionals, managers and administrators to make the best used of limited resources but at the same time to provide high quality, timely, evidence-based best practice, and aims to have:

(National Library for Health 2006).

ICPs are used in many settings for people with very different conditions (Box 3.18).

[References: Bayliss V, Salter L 2004 Pathways for evidence-based continence care. Nursing Standard 19(9):45–51; Brett W, Schofield J 2002 Integrated care pathways for patients with complex needs. Nursing Standard 16(4):36–40; Resource: NHS National Treatment Agency for Substance Abuse 2005 Models of care for the treatment of adult drug misusers. 5. Integrated care pathways. Online: www.nta.nhs.uk/publications/mocsummary/section5.htm Available July 2006]

Integrated care pathways

Examples of ICPs include improvement of the documentation for older patients/clients with complex health needs on an inpatient assessment unit (Brett & Schofield 2002), developing urinary incontinence pathways (Bayliss & Salter 2004) and the treatment of adult drug misusers (NHS National Treatment Agency for Substance Abuse [NTA] 2005).

The NTA (2005) suggests that care pathways should be agreed between and with local providers and contain a number of elements, including:

Improving quality and promoting excellence

The treatment and care that patients/clients receive from health and social care professionals should be justified in terms of its effectiveness and efficiency and be based on the best available evidence (see Ch. 5). The standards to be achieved are set by the National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence (NICE) and the NSFs. Also outlined is the role of the Healthcare Commission and patient surveys in quality improvement.

Clinical guidelines

NICE is charged with promoting clinical excellence and the effective use of available resources in the NHS. It is also responsible for the development and dissemination of guidelines for the management of a range of diseases, the most appropriate interventions to treat that disease or condition, measuring the effectiveness of those interventions and for ensuring that this guidance is shared with professionals. For example, clinical guidelines have been produced by NICE for the treatment of schizophrenia, infection control, head injury (children and adults) and eating disorders. Guidelines are protocols for clinicians to ensure that they are providing the best and most appropriate treatment/care to patients/clients. Guidelines may suggest a treatment pathway and offer a range of options which clinicians can take depending on the signs, symptoms, test results and the patient’s wishes. The guidance offers advice on how to assess and treat a patient’s disease or condition. The protocols may also contain information that clinicians can offer to patients/clients and their relatives.

The guidelines from NICE are not compulsory but there is an expectation that the NHS will accept the advice the guidelines offer; if it is not, then practitioners are advised to write an explanation in the patient’s records.

The Healthcare Commission includes a range of NICE appraisals of treatments and technologies (including drugs) in its clinical governance monitoring of the NHS in England and Wales. The system for assuring quality of services in Scotland has similarities to England and Wales, but there are some differences. NICE guidelines are also used in Scotland and Northern Ireland. However, in Scotland, the Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network (SIGN) also has an important role in quality assurance by reducing differences in clinical effectiveness and clinical outcomes by developing and disseminating Scottish national guidelines.

NICE is a Special Health Authority (see p. 82), whereas SIGN is a non-statutory autonomous body attached to an umbrella organization, NHS Quality Improvement Scotland (NHS QIS). NHS QIS develops and monitors the implementation of clinical standards (Box 3.19, see p. 92).

Box 3.19 NHS Quality Improvement Scotland

[From NHS Quality Improvement Scotland (2005)]

Scotland has one main body for clinical effectiveness – NHS Quality Improvement Scotland (NHS QIS), a special health board established by the Scottish Executive in 2003. NHS QIS works with the Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network (SIGN), the Scottish Medicines Consortium (SMC – clinical and cost effectiveness of medicines) and the Scottish Health Council (SHC – set up to involve patients/clients in decisions about health services, share best practice, involve and help patients/clients feedback to health boards).

NHS QIS state that their role is to:

NHS QIS is also an umbrella for several other organizations that work to improve the quality of healthcare in Scotland.

National Service Frameworks

According to the Department of Health, in England the NSFs are in place in order to:

A rolling programme of NSFs, started in 1988, includes coronary heart disease, cancer, mental health, older people, diabetes, long-term conditions, renal services, and children, young people and maternity services.

There are five components to each NSF:

Box 3.20 NSF for Mental Health. Modern Standards and Service Models

[References: Department of Health 1999a National Service Framework for mental health. Modern standards and service models. TSO, London; Department of Health 1999b Saving lives: our healthier nation. TSO, London; Resource: Department of Health 2006 National service frameworks (NSFs). Online: www.dh.gov.uk/PolicyAndGuidance/HealthAndSocialCareTopics/fs/en#4804536 Available July 2006]

The NSF for Mental Health (DH 1999a) is for adults up to 65 years of age. It has seven standards covering five areas and each of the seven standards is stated with the rationale for its inclusion, the service models specifically aimed to achieve it, the standards by which it will be assessed and those with the responsibility to achieve it.

Healthcare Commission

The Healthcare Commission is a statutory body set up in England to scrutinize the quality of healthcare and public health. The Healthcare Commission promotes quality improvement in both the NHS and independent sector. For example, at the time of writing they are consulting on a Draft 3-year Strategic Plan for Adults with Learning Disabilities 2006–2009, with a view to promoting improvement to the health and healthcare of adults with learning disabilities.

The Healthcare Commission is independent of the NHS and its main functions are to:

The Healthcare Commission takes active steps to reduce inequalities in health and improve people’s access to and experience of healthcare by promoting human rights and diversity. The Commission also works closely with the Mental Health Act Commission (not Scotland), making sure that there is adequate and effective protection of patients/clients who are detained under the Mental Health Act (see Ch. 6).

Performance Assessment Framework and National Patient Surveys

In line with the government’s commitment to making information about the quality of healthcare services available to the public, the Performance Assessment Framework (PAF) has been put in place. This approach looks further than the economic evaluation by assessing six areas, namely: health improvement, access to healthcare, efficiency, delivery of healthcare, health outcome and patient and carer satisfaction (DH 2005b).

A series of National Patient Surveys (NPSs) (Box 3.21) have been carried out and include:

NHS surveys

Patient/client involvement is a key theme in government thinking and policy. Patient surveys are one way of finding out what people think about services.

There is an expectation that the survey results will require action by Trusts. An example of some of the conclusions from the NPS on patient experience of outpatient departments indicated that 7% more patients were being seen within 3 months for their first appointment than in a previous survey conducted in 2003, and highlighted the need for better and improved communication between staff and patients/clients, particularly in relation to tests, treatment and danger signals to look out for.

Patient/client involvement

The involvement of patients/clients and the public was set out as fundamental to The New NHS (DH 1997) as a means of further enhancing quality of care provided by the NHS. Other core values were to make the NHS more responsive to the public’s healthcare needs and their expectations, and to make the NHS more open and accountable to the public. Therefore, services would be delivered by means of a public partnership with the service providers, e.g. the public would be involved in decision-making and monitoring processes, service planning, etc.

An additional independent, public ‘arm’s length body’, the Commission for Patient and Public Involvement in Health (CPPIH), was established in 2003 in order to:

Patient and Public Involvement Forums

Currently, there is a PPI Forum for every NHS Trust and PCT in England. They are made up of local people and have new powers. The forums take an active role in health-related decision-making within their communities. PPI Forums are key to raising awareness of the needs and views of patients/clients and the public, and placing them at the centre of health services. They have a number of primary roles, which include:

PPI forums provide an independent voice for patients/clients and members of the public. Primary care PPI Forums monitor and review the services commissioned from NHS Trusts. At the time of writing further changes in PPI structures are planned.

Other patient/public involvement structures

Other structures for patient and public involvement include the Patient Advice and Liaison Services (PALS), Independent Complaints Advocacy Service (ICAS) and Overview and Scrutiny Committees (OSCs).

Patient Advice and Liaison Services

PALs, as the name suggests, have as a major part of their role the responsibility to provide information and advice that patients/clients need when they use NHS services (see Ch. 5). For example, when problems do arise, the PALs team liaises and works with NHS staff, organizations and support groups and, if there is no resolution to the identified problem, patients/clients will be supported to make formal complaints to appropriate service managers. Further information about the core functions of PALs can be obtained at www.dh.gov.uk/assetRoot/04/06/67/50/04066750.doc.

Independent Complaints Advocacy Service

ICAS is funded by the NHS but operates independently. If patients/clients or members of the public want to make a formal complaint about an aspect of the service, the role of ICAS is to provide independent support and to act as advocates on their behalf, or to help them work through the processes and procedures involved in making a complaint in order to achieve their desired outcome.

Overview and Scrutiny Committees

OSCs were set up in local authorities to look at health service changes, health inequalities and ongoing operation and planning of health services in their local areas rather than how services are delivered or how services match government targets (Merry 2005). These committees are empowered to invite senior health staff to provide information and to explain how local needs are being addressed. This is thought to encourage openness and transparency in discussions about how local health and health services are being developed.

| Action for Sick Children | www.actionforsickchildren.org |

| Available July 2006 | |

| Age Concern (fact and information sheets about health) | http://www.ageconcern.org.uk/AgeConcern/6CAE34D017 |

| DD4279A805B52B6C3548E7.asp | |

| Available July 2006 | |

| Commission for Social Care Inspection | www.csci.gov.uk |

| Available July 2006 | |

| Department of Health | www.dh.gov.uk |

| Available July 2006 | |

| Department of Health, Social Services and Public Safety (Northern Ireland) | www.dhsspsni.gov.uk |

| Available July 2006 | |

| Devolved administrations in Northern Ireland, Scotland and Wales | www.direct.gov.uk/QuickFind/ |

| LocalCouncils/LocalCouncil Article/fs/en?CONTENT_ID=4007758&chk=6AB2yM | |

| Available July 2006 | |

| Direct Government – Caring for someone | www.direct.gov.uk/Audiences/CaringForSomeone/fs/en |

| Available July 2006 | |

| Healthcare Commission | www.healthcarecommission.org.uk |

| Available July 2006 | |

| National Audit Office | www.nao.gov.uk |

| Available July 2006 | |

| National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence | www.nice.org.uk |

| Available July 2006 | |

| NHS Direct, Best Treatments | www.besttreatments.co.uk/btuk/conditions/8620.html |

| Available July 2006 | |

| NHS Modernisation Agency | www.wise.nhs.uk/cmswise/default.htm |

| Available July 2006 | |

| NHS Quality Improvement Scotland | www.nhshealthquality.org |

| Available July 2006 | |

| NHS structure: | |

| England | www.nhs.uk/England/ |

| AboutTheNhs/Default.cmsx | |

| Available July 2006 | |

| Northern Ireland | www.n-i.nhs.uk |

| Available July 2006 | |

| Scotland | www.show.scot.nhs.uk |

| Available July 2006 | |

| Wales | www.abpi.org.uk/wales/wales_nhs.asp |

| Available July 2006 | |

| NHS Surveys | www.nhssurveys.org |

| Available July 2006 |

Alcock P. Social policy in the UK, 2nd edn. Basingstoke: Palgrave, 2003.

Association of Directors of Social Services. 2003 All our tomorrows: inverting the triangle of care. Online: www.adss.org.uk/publications/other/alltomtext.pdf.

Audit Scotland. 2004 An overview of the performance of the NHS in Scotland. Online: www.audit-scotland.gov.uk/publications/pdf/2004/04or01ag.pdf.

Beveridge W. Report on social insurance and allied services, Cm 6404. London: HMSO, 1942.