Chapter 14 The nursing process, holistic assessment and baseline observations

Introduction

This chapter provides an introduction to the nursing process and how it can be applied with different individuals who have varied healthcare needs. It acknowledges the diversity of nursing and provides examples of how the nursing process can be applied in child, mental health, learning disability and adult settings.

The key nursing skills required for holistic assessment are included, with emphasis on the need for effective verbal and written communication skills to promote accurate assessment followed by effective nursing intervention. Tools that assist in the assessment of individuals are explored as well as some models of nursing and approaches to care planning.

Assessment of a person’s health status includes the measurement of four vital signs: body temperature, blood pressure, pulse and respirations. In addition, a person’s weight, height and, in children, the growth rate may be measured. This chapter explains how each of the vital signs is measured and recorded.

The nursing process

Nursing and healthcare delivery systems throughout all branches of nursing are diverse. The philosophies that underpin approaches to nursing vary enormously. In the past, the medical model was prevalent in many areas of nursing. Using this approach, nursing care usually followed the medical diagnosis and was focused on the physical condition of the person. In addition, nurses often used intuition to initiate care delivery. Arguably intuition does inform care delivery although it should be used in combination with other measures. The practice of nursing is based on interpersonal relationships (see Ch. 9), with other technical aspects of nursing following.

In recent years there has been a move away from the medical model, recognizing the individuality of patients/clients and the need to address issues that go beyond the scope of physical care and medical diagnosis. However, medical diagnosis not only affects the needs that people may have, but also has an impact on other aspects of life. Thus, there is an attempt to provide holistic care to all groups of people requiring support from nurses and other healthcare professionals (Chin & Kramer 2004). There is also an increasing body of nursing knowledge available to support different nursing strategies and approaches to care, i.e. evidence-based practice (see Ch. 5). This too has an impact on care given. The decision to utilize a particular approach to care should therefore be based upon the unique needs of the person and family, as well as the nursing context (Fawcett 2000, Chin & Kramer 2004).

Yura and Walsh first described the nursing process in 1967 as a means of adopting a problem-solving approach to nursing care. The nursing process provides a systematic way of examining people’s problems with a view to providing intervention that would move towards resolving the problems. Their view was that nursing comprises more than intuitive care and that a systematic approach would allow further analysis of the problems that people present with and how they might be resolved. It should be noted that problems identified are problems of the person, not nursing problems. Thus, management of these problems should be person centred (Yura & Walsh 1967).

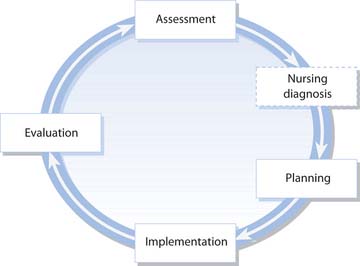

The nursing process can be applied in all nursing settings although the way in which it is applied depends on the health needs of patients/clients, the skills of the nurses and the care environment. The nursing process is cyclical and has a number of stages:

Sometimes a fifth stage is added to the nursing process – the nursing diagnosis stage – which fits between the stages of assessment and planning (Fig. 14.1). The nursing diagnosis stage has been adopted more in North America than in the UK. The North American Nurses Diagnosis Association (NANDA) has provided standardized nursing diagnoses for many situations (Walsh 1998). Nursing diagnosis explains the effect of the medical diagnosis. For example, the patient may have suffered a heart attack (myocardial infarction) and so one of the nursing diagnoses may be ‘central chest pain’. Nursing diagnosis has been used to standardize terminology and assist the process of audit, a mechanism to measure quality of care to determine if standards are being met. The other four stages are discussed below.

The nursing diagnosis stage relates to the diagnosis of nursing issues, which may be based on an underlying medical condition but differs from the medical diagnosis. Medical diagnosis is the identification of disease from examination of symptoms and presenting features, whereas nursing diagnosis is more about gaining understanding of the person’s situation, which may have wider implications for the person and also impact on other healthcare professionals (Barker 2001a, NANDA 2001). The approach to planning care influences whether or not the nursing diagnosis stage is included. Patterns of care delivery vary and the UK is moving towards multidisciplinary ways of working with documentation being designed to incorporate multidisciplinary terminology.

As the nursing process is cyclical in nature, evaluation can lead to reassessment if required. If patient/client goals (see p. 358) have been achieved, care can be stopped relative to the goal or the plan of care may be modified if the goal has not been fully achieved.

While the nursing process can be applied in different settings, it is helpful to use a tool that will provide further guidance appropriate to the needs of people and the care setting. This can be achieved by the use of a model of nursing (see p. 359). The stages of the nursing process are explored below.

Assessment

The first stage is assessment of the patient’s/client’s and family’s needs. Assessment involves collecting information (data) about the person and using that information to make decisions about what care, support or intervention is required. Decision-making involves organizing and interpreting the information collected. Professional judgement may also contribute towards the decision-making process. Assessment documentation and techniques vary according to the setting, e.g. outpatient, inpatient, short stay, ambulatory care, rehabilitation, day care, primary care based in the home, clinics or surgeries. Risk assessment is discussed fully in Chapter 13; however, it is an integral part of the assessment process.

As assessment is the cornerstone of establishing what a person’s needs are, so the quality of assessment is pivotal to the success of the nursing process. Successful nursing intervention hinges on a complete and thorough assessment being undertaken. Even throughout the other stages of the nursing process, the nurse continues to assess the response to care and success of interventions. Thus assessment is an ongoing process. The aims of assessment are to:

Assessment is a complex, time-consuming activity that requires many skills. Assessment of someone’s needs should be performed jointly with the person whenever possible. Establishing people’s own perspective of their problems helps to create partnership working and assists in providing person-centred care that is holistic in nature. Sometimes this is not possible due to the nature of the person’s problems, for example in a high dependency setting when the patient is unconscious, or in a mental health assessment unit when a client is confused and disorientated.

The information required in any given assessment situation will be determined by the nursing context. Confidentiality should be maintained in all settings (Nursing and Midwifery Council [NMC] 2004; see also Ch. 7). Information should be collected systematically to ensure that important issues are not overlooked. A combination of observation, interview and measurement is required to provide a full assessment (NANDA 2001).

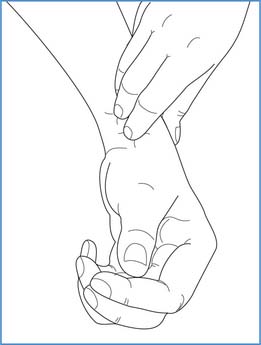

Observation is a key nursing skill that informs the overall assessment process. Observing is a form of data collection made by using the senses. Visual observation can relate to all aspects of the person. General characteristics of the person’s appearance and physical signs such as skin condition can be observed (see Ch. 16). Touch is also used to assess characteristics such as the temperature of a person’s skin, presence or absence of pulses or signs of dehydration such as dry, inelastic skin (Barker 2001a). Smell can be used to assess dimensions of a person in relation to the environment, such as chemicals in the air. In relation to the person, alcohol may be smelt on their breath or smoke on their clothes.

Interactions with other people can be observed, e.g. verbal and non-verbal communication (see Ch. 9). People’s behaviour can also be observed, e.g. their reactions to a particular situation, including emotional signs such as crying. Observations should be systematic to ensure the fullest information is gathered.

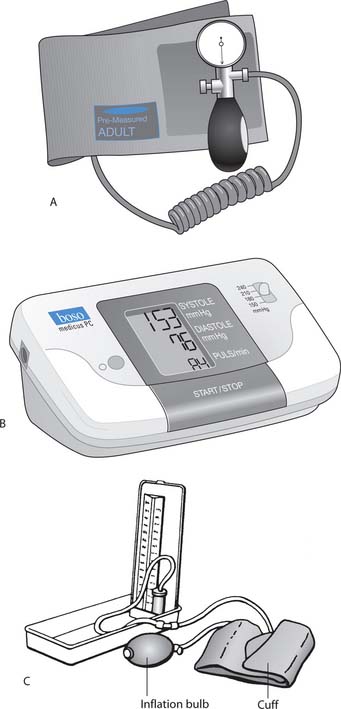

To complete assessment accurately, practitioners should strive for objectivity. Personal interpretations of observations should be avoided. For instance, when describing a person’s physical characteristics, it is desirable to retain objectivity and, where possible, to be specific. For example, blood pressure ‘180/95’ instead of ‘blood pressure high’, or ‘smiles frequently’ rather than ‘happy’. Essential nursing skills include objective measurement. Equipment such as a thermometer to measure temperature (p. 373) or sphygmomanometer to measure blood pressure is often used (p. 381). Height and weight may be measured with the use of a measuring tape and set of scales (p. 386). Quantifiable information is therefore acquired through the use of equipment as well as direct observation.

Information can be collected in a variety of ways, depending on the situation. The initial assessment of people attending an emergency department will differ greatly from the assessment undertaken by a practice nurse who is immunizing a family going abroad on holiday. The practice nurse makes an assessment of what is required for the safety of the travellers in the longer term, whereas the emergency department nurse makes an initial short-term assessment of the person in relation to their priority for treatment.

Holistic assessment

For assessment to be comprehensive, it should be undertaken in a holistic manner. Thus, the following dimensions of need should be assessed (Fawcett 2000):

While people may present to the nurse with similar medical or social problems, it is only by thorough and systematic assessment that includes the physical, psychological, sociocultural, spiritual and emotional dimensions of their lives that a truly individualized plan of care can be developed. It can, however, be difficult to separate the dimensions, as they are all interrelated and can impact on a person’s health in different ways (Box 14.1).

Holistic assessment

Anna is a young married woman with small children who is undergoing radiotherapy treatment for cancer. She may experience physical side effects including fatigue. The fatigue may cause anxiety, as Anna may be less able to look after her children and fulfil family obligations. She may consider not completing the course of radiotherapy to allow the fatigue to diminish. It is only by undertaking a holistic assessment that the impact of the treatment on Anna and her family’s lives can be ascertained.

The nurse’s role is to identify and react to a person’s response to their own situation. Thus, while a medical condition is acknowledged when assessing a patient or client, it only forms part of the assessment. The aim is to acquire the fullest information necessary without gathering irrelevant information.

Priorities of assessment may differ within the different branches of nursing. In mental health, assessment may concentrate initially on psychological and social dimensions since much of the care of people with mental health problems centres on human responses to illness (see p. 366). With children it is appropriate to use a child and family-centred approach (see p. 367). The benefit of such an approach is that it addresses the needs of the family as well as the child. Learning disability assessment also has unique characteristics, which are discussed later. Nurses working in many settings will meet people with a learning disability as most live in the community and access health services in the usual ways, e.g. though primary care via their GP or practice nurse. What is important is that the principles discussed on page 351 are incorporated into the assessment process.

The nurse will undertake a decision-making process to make sense of the data collected from the assessment and formulate a plan of care. Thus the nurse’s assessment of the patient/client will form the nursing history. An example of the types of questions that the nurse may ask is provided in Box 14.2.

Box 14.2 Questions that may be asked during the assessment interview

Breathing

Sources of information

Information can be gathered for assessment purposes from:

Primary source

The patient or client should be the primary source of information, including children and young people as developmentally appropriate, as it is important to elicit their own perspective of their situation. To successfully interview the patient/client, the nurse needs to be a skilled communicator; questioning, actively listening and eliciting information (see Ch. 9). Often assessment is undertaken in difficult circumstances, e.g. emergency admission to hospital is an anxiety-provoking event for patients and their relatives. Crisis intervention within community mental health nursing is another occasion when assessment is required, usually following a series of difficult events leading up to the need for intervention. The initial impression the nurse may have of the patient/client and their family can influence the ease with which the nurse is able to elicit reliable information. If the nurse gives the impression of being disinterested or hurried, it is unlikely that an accurate assessment will be made. Assessment should form the beginning of a trusting relationship between the nurse and patient/client and provides the person with the opportunity of putting their view of their current situation forward. There may be occasions when the patient/client is unable to provide information, through illness, confusion, being too young or having difficulty with communication, e.g. learning disability.

Secondary sources

These are used together with the primary source. Biographical data can be confirmed from previous health records. It is important to confirm the currency of this information in case of changes in circumstances such as someone being widowed or having moved house. Social and medical history can often be confirmed from other health records. Other practitioners can also offer information about patients/clients. For example, key workers of individuals living in residential or nursing homes can provide information if a client is hospitalized. Patient-held records or patient passports are also used, when available. Past medical history is also important to assess along with the current health situation. This can reveal information that may impact on the current situation, such as know-ledge of allergic reactions to a drug or relevant information about the person’s prior experience. Family members and significant others can also be rich sources of information about the patient/client and how their current situation is affecting their ability to cope with daily living.

Discharge planning

Prevention of early readmission may be avoided if discharge planning is robust enough to support the person on discharge. Inadequate planning and coordination can lead to unnecessary suffering and can also have a major impact on the resources needed to support the person. Preparing a patient/client and their family for discharge from hospital is an integral part of nursing care (Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network [SIGN] 2003). In many cases discharge is the most important aspect of a hospital admission for the patient/client and their family. In addition, the way it is managed can influence its success (Department of Health [DH] 2000).

As many hospital admissions are very short, planning for discharge should be incorporated into the initial assessment and even pre-assessment stage. During surgical pre-assessment visits (see Ch. 24), people are given information regarding requirements for going home following surgery or other invasive procedures. If a patient lives alone and is unable to have someone stay with them following discharge after day surgery and/or an anaesthetic, an overnight hospital stay may be more appropriate. Thus social, physical, psychological, economic and environmental aspects of assessment are crucial in providing relevant information that will inform a safe discharge. With many people being discharged following hospital admission for acute problems, or longstanding chronic problems, complex management plans and packages of care may be required and therefore a coordinated approach to discharge planning is required. Early supported discharge teams are in place in some specialties such as orthopaedics and care of older adults. Within these services, there is explicit inclusion of discharge criteria in the care planning documentation. The nurse caring for the patient has a responsibility to ensure that a multidisciplinary approach is taken when required. Clinical governance is the provision of first class services to users, achieved by creating a framework within which evidence-based practice can be achieved (Chs 3, 5). This requires that discharge planning is documented and is an integral part of care delivery, emphasizing the need for the nurse to work in partnership with other professional groups and agencies (DH 2000).

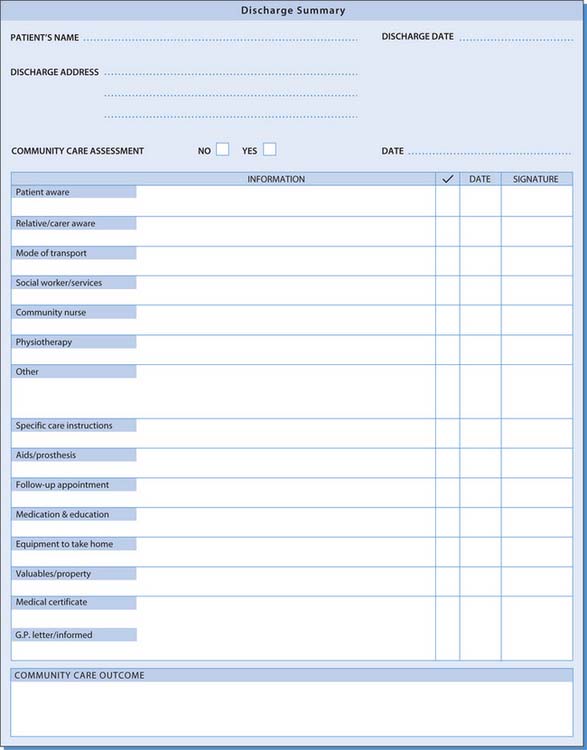

The nature of the patient’s health needs or presenting problems will inform discharge planning; for hospitalized patients, nurses also need to enquire about the perspectives of carers. Most patients do not exist without a network of significant others who can provide information about them; they must also be consulted about certain aspects of care such as the transition from home to hospital, or hospital to home. Without the support of significant others, it is often not possible to achieve a successful discharge. Within the assessment stage of the nursing process, discharge planning is a vital aspect of providing seamless care across primary and secondary care settings. Therefore family and sociocultural aspects also need to be explored during the assessment stage. Figure 14.2 shows a sample discharge schedule.

The assessment interview

The planned assessment interview that forms the basis of the nursing history can take place in many settings. The health visitor may conduct an assessment of a child’s developmental progress at home surrounded by parents and other family members. Alternatively, the assessment might be in a situation of crisis, such as a serious injury following an accident. Whatever the situation, there must be structure to the interview. The focus will be not only on the documentation being used but also on the person being interviewed. It is important to include both. The use of documentation alone will not allow the whole spectrum of issues to be captured. The first interview allows the nurse to gather baseline information about the person. Comparisons against this information will be ongoing. In some settings the interview will be conducted by a doctor and a nurse such as in acute mental health admissions (Barker 2001a). The advantage of this is that the client will not have to repeat similar information to different professionals. There is also the benefit of engaging in multiprofessional working, with all health professionals sharing care of the patient to provide a cohesive service (Barker 2001b).

Privacy

At all times during the assessment process, privacy must be respected. This may be easier to achieve in some settings than in others, e.g. when an interview room is available. In the patient’s/client’s home or in a busy department where there are many other people, it may be more difficult to achieve and therefore careful consideration is needed. In the home it may mean asking other family members to leave the room, or in the department it may be necessary to speak quietly behind screens. Other barriers to effective communication need to be identified and remedied, e.g. environmental noise affecting concentration could be avoided by moving to a quieter area. Language barriers may be overcome by the use of interpreters from within the family or the health provider organization. Confidentiality should be maintained if interpreters are being used. It should be recognized that factors affecting the quality of the interaction between the nurse and the person may have an adverse effect on the quality of care provided (see Ch. 9 and Box 14.3).

Interpretation of information

The nurse will undertake a decision-making process to make sense of the data collected from the assessment and formulate a plan of care. Nurses need to be aware of their own beliefs, values and attitudes as well as their level of knowledge and competence. Assumptions should not be made about the condition of a patient/client. Not all patient/client observations, such as blood pressure measurements, can be validated. For example, it is difficult to measure the level of anxiety a patient is experiencing (see Ch. 11). As such, nurses need a degree of self-awareness to ensure that value judgements and assumptions are not made regarding the person’s situation.

Staging assessment

The use of a step-wise approach to assessment is sometimes appropriate, with some aspects of the assessment process being undertaken immediately while others are undertaken later. For example, an older adult being admitted to a care home may have a full assessment undertaken over a period of 1 week to minimize the effects of relocating on their usual routines and ability to adapt. An unconscious child admitted to an emergency department would need immediate assessment to allow priorities of care to be established.

It is sometimes inappropriate to explore every aspect of assessment at the initial interview. In some mental health and learning disability settings, client assessment may be undertaken incrementally as the therapeutic relationship is established. This is also the case in situations when a person is moving into long-term care, e.g. a nursing home. If this is the case, the nurse assessing must take responsibility for ensuring full assessment is completed. This can be useful if the patient/client needs time to adjust to their new situation before discussing sensitive issues with the nurse.

Documentation

Documentation of the nursing process, at each stage, is an important way to communicate to other members of the healthcare team how the patient/client is progressing and responding to interventions. Documentation must be comprehensive and accurately reflect the health status of the patient/client. Accuracy is achieved by recording information precisely, e.g. ‘the patient had 150 mL of tea, toast and scrambled eggs’ rather than ‘good appetite’, as appetite varies from person to person, and also from nurse to nurse, thus making the assessment subjective. It is a professional requirement to record nursing interventions and the information collected to inform the intervention, as nursing documentation is a legal document (NHS Quality Improvement Scotland 2004, NMC 2005).

Assessment documentation takes different formats according to the setting (Box 14.4). Electronic records of care are being implemented gradually throughout the UK as information technology systems are developed to support healthcare delivery (DH 2000). Patient-held records are also used. People who have chronic conditions are being encouraged to be empowered through self-management plans, particularly in community settings. For example, in asthma care when a person attends the practice nurse, the GP and an outpatient department, it is useful for them to have one record that can be used by all professionals to improve continuity of care across primary and secondary care settings. Increasingly, multidisciplinary documentation is being developed with the whole team having access to the records. Confidentiality should be maintained at all times regarding documentation, irrespective of the mechanism being used (NHS Quality Improvement Scotland 2004, NMC 2004).

Assessment issues

Assessment documentation varies between placements and client groups, and may be paper based or electronic.

The Joint Future Report (Scottish Executive 2000) advocates single shared assessment between health and social care agencies. Single shared assessment is intended to simplify the assessment process, be person centred and clarify responsibilities for providing care. Making this process work, however, requires commitment from all healthcare providers as it may mean the erosion of traditional professional barriers and boundaries. It is envisaged that single shared assessment will be most applicable to older adults and people within the community. Increased multidisciplinary and interagency working may enhance shared ways of working towards common goals for people using health services. Person-centred approaches require commitment from personnel in all organizations involved with clients, entailing a more consumer-orientated approach putting the patient/client central to planning of their healthcare. These approaches present challenges to all groups of health professionals, especially those accustomed to a discipline-specific approach to care. The underpinning philosophy of shared assessment is that it is ‘needs led’ rather than ‘service led’. Additional information about shared assessment can be found on the Department of Health website www.dh.gov.uk/NewsHome/YourHealthYourCareYourSay/fs/en.

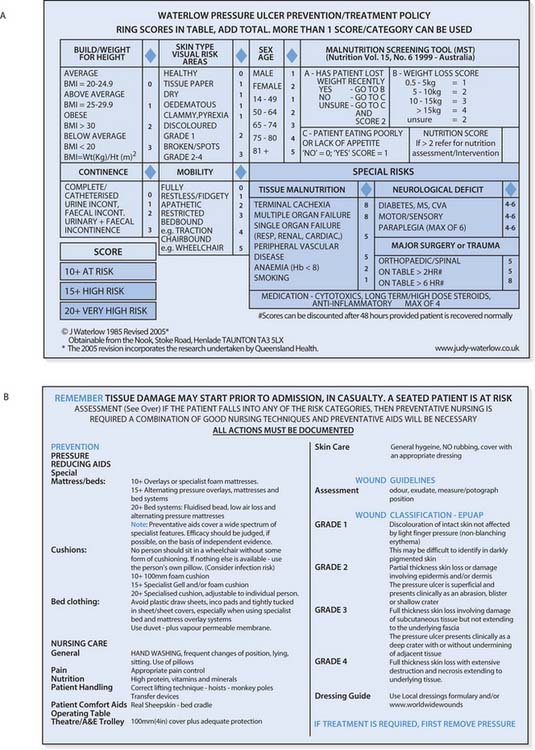

Assessment tools

As part of the assessment process, it may be necessary to collect further detail about a particular aspect of need. Additional data can add to holistic assessment. Assessment tools, developed by nurses (practitioners and researchers), provide a validated method of eliciting information with a view to minimizing patient/client risk. Assessment tools, as part of risk assessment, form part of the overall assessment process and will be dependent on the unique needs of the patient. Tools devised by other professional groups are also used by nurses, e.g. the Glasgow Coma Scale and Paediatric Glasgow Coma Scale (see Ch. 16). An example of a commonly used assessment tool is the Waterlow scale, a pressure ulcer risk assessment tool (Fig. 14.3; see also Ch. 25). This is used to predict the level of risk of an individual developing pressure ulcers, taking their overall condition into account (Box 14.5). Tools should be appropriate to the client group to optimize their effectiveness. Risk assessment (see Ch. 13) should be performed at appropriate times, e.g. when there is a change in the health status of a patient/client. It is important that all staff using an assessment tool are familiar with its use.

Using assessment tools

Planning

This stage of the nursing process involves identifying the person’s problems or needs and what nursing care, intervention or support is required. The care plan should be written down and contain clear statements about how the person’s goals will be achieved (see below). The patient/client should also be involved in this stage if possible. The format of the care plan depends on the particular setting. As well as establishing the person’s existing problems, any potential problems are also identified. Learning disability nurses may also concentrate on a client’s strengths as well as weaknesses.

Prioritizing care

Planning also incorporates prioritizing care according to the needs of the individual and seriousness of the problems. Life-threatening situations such as airway obstruction must be considered and acted upon before wider health needs such as the desire to stop smoking. Determining priorities is achieved through an understanding of the theory and concepts underpinning nursing (Chin & Kramer 2004). Involvement of the person in this stage of the nursing process also assists in prioritizing care according to their wishes if there are no life-threatening issues. Through communication, mutually agreed goals can be set, based on the person’s perception of their situation.

Actual and potential problems

Consequently, nurses need to be able to ‘see beyond’ the present situation and use their knowledge and expertise to avoid complications and potential problems occurring (Box 14.6). It can be seen from Rashid’s situation that the impact of one problem can potentially create many other problems for him that transcend different dimensions of need (p. 351).

Box 14.6 Actual and potential problems

59-year-old Rashid was admitted to hospital with a left-sided weakness and investigations show that he has had a stroke. Rashid is left handed. One of his actual problems is that he is unable to move his left side, which might affect his mobility, skin integrity and independence.

Goal setting as part of care planning

Goals are set to enable measurement of the success, or otherwise, of the nursing interventions planned to meet them. Different types of nursing action are often required to meet the goals. For example, different members of the healthcare team may deliver different aspects of the care required. Which member of the team delivers the care to an individual depends on the complexity of their care and on the skills of the members. Competent healthcare assistants may perform some nursing interventions, e.g. they may be able to assist people to maintain personal hygiene. However, for some therapeutic interventions, the registered nurse (RN) would be required to monitor some parameters such as central venous pressure.

Goals can be either short or long term. They should be person centred and achievable. To assist in this, goals should be SMART and incorporate the following characteristics:

A goal could be ‘the patient should drink 2.5L of fluid within the next 24 hours’. Within this goal, it would have been assessed that the patient is capable of taking fluids orally, making it achievable and realistic. It is specific because it states the amount of fluid to be taken, is measurable as fluid intake and is time orientated as there is a timeframe allocated to its achievement. Box 14.7 provides an example of short- and long-term goals. If goals are unrealistic and unachievable, this can lead to disappointment of both the patient/client and the nurse. As a consequence, the therapeutic relationship may be adversely affected.

Box 14.7 Short- and long-term goals

Eddie has been admitted to the ward with breathlessness. In relation to this the following goals may be appropriate.

The goal may be achieved by:

Implementation

Putting the care plan into action forms the implementation stage of the nursing process. Implementation should incorporate current evidence-based practice (Ch. 5). The care plan may encompass physical, psychological, social, emotional and environmental interventions. Implementation may also include activities that are outwith nurses’ expertise, e.g. it may be appropriate to refer the patient/client to another healthcare professional such as an occupational therapist for assessment of dressing ability. This referral is the nurse’s responsibility and is recorded in the care plan. Such multidisciplinary working and collaboration should assist in providing holistic care.

Evaluation

Evaluation determines if the planned intervention has been effective in achieving the goals set. The goals are reviewed to determine whether or not the patient has met them or is moving towards meeting them. At this stage the goals can be modified or changed according to the patient’s/client’s response to the interventions. If a goal has been achieved, this is documented. If a goal has not been achieved, the nurse should question why this is the case, and reassess the patient. Perhaps the goals did not encompass the SMART characteristics or the patient’s/client’s condition may have changed, making the goals unrealistic. Health needs are dynamic and thus require periodic reassessment. Evaluation is an ongoing action that forms part of the cyclical nursing process. However, evaluation is only possible if clear criteria have been applied to the goals. Evaluation of care can be used as part of nursing audit (see Ch. 5).

Nursing models

A nursing model, also known as a ‘conceptual model’, is a tool used to guide nurses as they engage in the nursing process and can be viewed as a practical way of putting the nursing process into action. There are many different nursing models, as nursing takes place in very diverse situations, with the needs of people varying enormously, and some of these are explored in this section. As nursing models have different philosophical assumptions underpinning them, each presents a unique perspective of nursing knowledge and nursing practice.

Most nursing models are based upon four concepts, which are said to form the essential structure of nursing. The relationship that emerges between the nurse and patient/client will depend on these four concepts:

Each model adapts the nursing process according to its own relationship between the four concepts and the particular nursing approach. Emphasis on the four concepts varies according to the theoretical underpinning of the model. Thus, each model represents a unique view of nursing and its relationship to practice (Fawcett 2000). Within the four branches of nursing, therefore, different models are used. Models also vary within primary and secondary care settings, highlighting the diversity of nursing practice. Central to the use of any nursing model is the need for nurses to have excellent communication skills (see Ch. 9).

The Roper, Logan and Tierney model for nursing

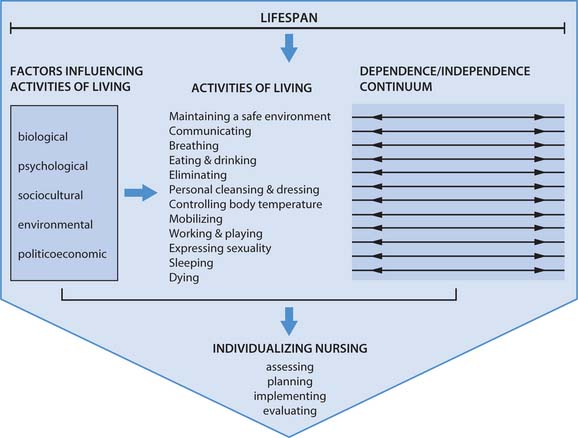

The Activities of Living Model was developed in the UK by Roper, Logan and Tierney who first published the Elements of Nursing in 1980. Their work developed some of the central components of Virginia Henderson’s earlier definition of nursing (see Ch. 2). There are two parts to this model: the model of living and the model for nursing (Fig. 14.4). Over the years it has been refined, indicating that nursing is a dynamic profession, constantly developing in response to external influences.

According to Roper et al (2000), five interrelated components form the core of the model of living:

The individual

According to Roper et al (2000), individuality in living acknowledges that each person has a unique way of performing the ALs according to where they are on the lifespan, the degree of dependence/independence they have and the influences of biological, psychological, socio-cultural, environmental and politicoeconomic factors. Individuality in living is concerned with how an individual experiences and performs ALs according to their preferences, abilities and attitudes.

Activities of living

Roper et al (2000) suggested that 12 activities are essential for survival:

It is evident that the activities cannot be viewed as mutually exclusive as they are dimensions that interlink with each other (Box 14.8). For example, it is not possible to consider elimination without considering eating and drinking. The care planning questions in Box 14.2 (see p. 352) can be used to consider planning the care that may be needed to meet dependence in ALs.

The relationship between factors influencing ALs and the interdependence of ALs

Jane is 17 years old and lives with her mother and 11-year-old sister. Jane’s parents are divorced and her father is not in contact with them. Her mother has chronic arthritis and is physically dependent on Jane to support her with running the house. Jane helps her mother to get into the shower in the evenings and collects her prescriptions. She also does the shopping, cleaning, ironing and supervises her younger sister with homework and getting ready for school. Jane is at college full time and on Friday evenings her friends often go the student union then on to a nightclub. Jane is usually too tired to join them.

Lifespan

The lifespan is considered to be a continuum with changes occurring along it from birth to death. Throughout this time, every aspect of living is influenced by biological, psychological, sociocultural, environmental and politicoeconomic factors.

The five stages of life identified by Roper et al (2000) are:

Throughout these periods, levels of dependence and independence vary. An infant is vulnerable and dependent on others for survival and love. Childhood and adolescence are affected by cultural issues, sociocultural norms and subcultures (see Ch. 8) and are dominated by the family. In adulthood, work and family affect lifestyle. In old age, individuals may have an illness that affects their level of independence, e.g. arthritis which can impair mobility.

Factors influencing the ALs

There are five main factors that can influence daily living (Roper et al 2000), as outlined below.

Biological factors

In the context of the model of living, biological factors relate to physical and physiological performance. While there are predetermined genetic influences affecting physical characteristics such as skin colour, hair colour, height or genetically determined diseases such as haemophilia, other factors can also affect physical characteristics and function. In wartime, if a child is deprived of food, growth may be affected, resulting in slower rates of growth and development. Thus, environmental and politicoeconomic issues may also affect physical factors. Biological factors associated with ageing may affect a person’s ability to work, thereby impacting on their sociocultural status.

Psychological factors

Mental and intellectual activity begins in childhood and continues through adolescence, adulthood and into older age (see Ch. 8). The stimuli within these lifespan phases vary. In childhood, development begins through sensory stimuli that can be influenced by family issues such as having siblings who may spend time playing with the toddler. In adolescence, development can be affected by the place of the child in the family and the expectations placed upon them. Thus environmental factors may also influence psychological development. Development across the lifespan is discussed in Chapter 8.

Sociocultural factors

Ideas, values, knowledge and beliefs are embedded within cultural norms of groups within society (see Ch. 8). Thus, many variations exist among the population from which patients and clients will come. Culture is unique to groups of people and can affect the behaviour of individuals. It is important to remember that cultural beliefs may have a profound impact on lifestyle and the responses of people who need to access health services. Dietary practices can have an impact on biological factors; for example, vegetarians may have a low iron intake leading to low blood haemoglobin levels and anaemia. Religion may affect how individuals respond to treatment options, e.g. Jehovah’s Witnesses may reject blood transfusion as a treatment option compatible with their beliefs. Therefore sociocultural aspects may impact on biological and psychological factors.

Environmental factors

Environmental factors include housing, the atmosphere, noise and sound. Any of these elements can influence the other factors. Atmospheric pollutants such as carbon monoxide can aggravate respiratory conditions such as asthma, thereby having an impact on biological and psychological factors. Noise pollution can cause anxiety that may impact on psychological and biological functioning, e.g. by causing insomnia and anxiety.

Politicoeconomic factors

The economy, law and the state comprise the politicoeconomic factors that impact on individuals. People are governed by fiscal measures such as the need to pay council tax. Local and national economies also affect people and consequently their behaviour. For example, people on low incomes have limited choices on which to spend their money. Asylum seekers who are given vouchers as part of their financial support may have few choices about where they can exchange them. This may lead to lack of choice and being unable to follow dietary customs, thus impacting on biological and psychological factors.

It can be seen that the main themes of the model are inextricably linked and the activities in Box 14.9 highlight this.

Factors influencing activities of living

For groups such as asylum seekers, people with a learning disability or people with chronic illness, consider the extent to which they may have control over the factors that influence ALs.

Student activities

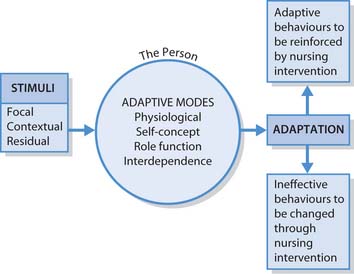

Roy’s adaptation model

Sister Callista Roy developed this model in the USA in the 1960s. It has been refined over the years to make it suitable for nursing in the 21st century (Roy & Andrews 1999). The basis of Roy’s model is that individuals must adapt to a constantly changing environment. The health of the individual is a reflection of that adaptive process. It is a behaviourist model as it is concerned with the way in which individuals behave in response to changing circumstances. Behaviourism is the study and observation of how individuals behave (see Ch. 4).

Roy’s behaviourist model is based on the following two philosophical assumptions:

The model is based on the following two scientific assumptions:

Within the model, there are three types of stimuli (systems). These are:

Roy and Andrews (1999) state that there is an interrelationship between these three systems, with all of them working together to maintain a balance within the individual. For example, if a person is physically unable to drink fluids due to a swallowing problem they may become dehydrated, and thus the internal body environment may be affected. Equally, if someone is trekking across the desert with no water to drink, their social system is affecting their physiological status as they are unable to access fluid to prevent dehydration. Thus the systems are interrelated and interdependent, interacting with each other at all times.

According to Roy, if an individual adapts to these stimuli, it could be said that they are healthy. Most people cope effectively with constant changes to their internal and external environments. During a heat wave, for example, an individual may drink more fluids, slow down their level of activity and increase the ventilation of their home. An individual who is unable to make these changes, such as a toddler, may be considered to have an ineffective response to the stimulus of heat. If the individual has not adapted to the stimuli then the role of the nurse is to assist the person to adapt to it. Thus the focus for the nurse is to identify the stimuli to facilitate adaptation in the individual patient/client. Roy acknowledges the individuality of people and so there will be no complete state of balance applicable to everyone. Therefore the nurse must recognize the needs of individuals.

Roy discusses the adaptation level of individuals as forming an adaptive range. Behavioural responses to stimuli can be effective, adaptive stimuli, or maladaptive. The factors that cause problems of maladaptation are called stimuli and there are three types:

Thinking about Roy’s model

The activities below will help you consider how Roy’s approach could affect you as a student nurse.

Student activities

Adaptive modes

There are four adaptive modes within Roy’s model that serve as a framework for assessment. It is believed that a person’s response to stimuli can be observed in these adaptive modes:

Roy states that these four modes contribute towards the promotion of adaptive goals leading to integration and wholeness. Nursing intervention would be required if there is a need deficit.

Planning

Planning should identify SMART patient-centred goals (see p. 359) that should incorporate the following:

Evaluation

This involves exploring whether the goals have been met, thus determining if the adaptation response has been achieved effectively or ineffectively. Reassessment occurs at this stage.

Figure 14.5 shows the nursing process as it relates to Roy’s adaptation model.

Integrated care pathways

As an alternative to nursing care plans, integrated care pathways (ICPs) may be used. ICPs are sometimes called integrated care plans, care protocols or care maps. The ICP is a single document in which all members of the multidisciplinary team (MDT) record their care. The ICP details expected problems, interventions and outcomes for a specific disorder or group of people. These are devised with explicit agreement by local groups of multidisciplinary and multiagency staff. The aim is to provide a comprehensive service to a group of service users or patients with a specific condition. The introduction of ICPs has been driven by government strategy, which aims to provide improvements in quality of care (DH 2001a). Care pathways are devised on the basis of current evidence for best practice. Much of the evidence on which care is based is informed by the National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence (NICE) and SIGN, part of NHS Quality Improvement Scotland.

The MDT agrees on the format of the record that will be used by all professionals, not just one group, e.g. nurses. The pathway anticipates the expected requirements for care and the outcomes for the patient within a specified timeframe. SMART goals (see p. 359) are incorporated into the care pathway. It is still important to have the patient at the centre of the care pathway to ensure that the required standard of care is met (Yura & Walsh 1967). Individual assessment is still undertaken, often based on the assessment process associated with a nursing model. It is important that the philosophy of the assessment meets the needs of the patient/client group. For example, a patient undergoing surgery that may impact on their self-image, such as limb amputation, needs to be assessed psychologically and emotionally to determine their ability to adapt. Thus the assessment may be based on Roy’s adaptation model. So, although the ICP is multidisciplinary, within its development it is vital that the nursing approach is robust enough to incorporate holistic care (Box 14.11).

Integrated care pathways

Having a single document can help to provide an integrated approach to care, with shared working between professionals encouraging greater understanding of others’ roles and responsibilities.

While the initial pathways focused mainly on surgical procedures and interventions where the outcome is relatively predictable, there is now increasing development of pathways in the fields of older people and mental health, indicating the acceptance of increased team working and accountability for providing quality care (DH 2001b). However, for problems that require prolonged periods of intervention, ICPs are still considered less appropriate. Development and implementation of ICPs is challenging to professional groups. The benefits of using ICPs include:

Variance

There are often reasons why a patient will not follow the expected path of recovery or response such as the presence of other health issues from any aspect of their life, i.e. physical, psychological, emotional, spiritual, sociocultural or environmental. This does not necessarily mean that the pathway is unsuitable for the patient, but rather it may highlight the unique features of any individual who requires care. If a patient varies from the expected pathway, this is documented on the care pathway, including whether the variance was avoidable or not. For example, other diseases impacting on patient progress is unavoidable whereas a delay in having a test performed is avoidable.

Planning care for people with learning disability

The focus on the needs of people with learning disability is embedded in national strategies published in the government’s White Paper Valuing People (DH 2001b). The Scottish Executive (2002) published Promoting Health, Supporting Inclusion, a strategy document to guide practice and the Welsh Assembly Government (2002) has an equivalent, Inclusion, Partnership and Innovation. These strategies, along with societal changes, have provided frameworks for the move towards social inclusion for those with learning disability. The underlying key principles of these documents are:

Therefore, in order to care for people with learning disability, these key principles need to be included in the planning process. Individuals with learning disability often have complex health needs. While specialist learning disability nurses are in a strong position to begin to assess and meet these needs, generalist nurses may also assess the person’s needs if the four key principles above are encompassed in their care. It is desirable for people with learning disability to achieve citizenship within the communities in which they live. In order to facilitate citizenship, nurses in all settings need to be able to assist people with learning disabilities to make informed decisions about their health and health issues.

When planning care for individuals with learning disability, traditional ways of care planning may not always fully encompass these key principles. Many learning disability nurses consider that nursing models are too focused on the medical model. An alternative to using the traditional nursing models was advocated by O’Brien (1987) who focused on the concept of ‘normalization’. This approach advocated a way to improve the quality of life of clients although the focus was on services rather than individuals. Nonetheless, this approach has been used successfully to plan and deliver care packages. The development of the term ‘social role valorization’, referring to the support of valued social roles for those who are at risk of being devalued within society (Gates 2002), has largely superseded normalization.

As the spectrum of learning disability is very wide, ranging from mild to profound and complex, the only way to plan and provide supportive care is by placing the individual at the centre of the planning process.

Person-centred planning

Person-centred planning is a way of working in partnership with people and their families to achieve personal autonomy, which is pivotal to realizing the policy aims for people with learning disability (Scottish Executive 2004). As people with learning disability often have unmet health needs, another aim in caring for these people is to help the person have more control over their health (Gates 2002). For people who have difficulty in articulating their views, an advocate may assist in eliciting their views and thoughts. An advocate may be a paid care worker or a family member or friend.

Person-centred planning aims to assist people to choose the lifestyle they want. Acknowledgement of the person’s disability is made, with acceptance of their need for support on their own terms. The focus is on capacity and capacity building, which means working towards maximizing ability.

Person-centred planning can be achieved by sharing of power between the person, family and professional (O’Brien & O’Brien 1998). Any significant person involved with the client may be involved, e.g. paid support workers or those who act as advocates for the person such as family members. Support workers may be part of the MDT such as learning disability nurses, resource workers, physiotherapists, speech and language therapists, occupational therapists and psychologists. Learning about the person is crucial to developing an understanding of their needs. Careful listening (see Ch. 9) and consultation are essential to fully assess the individual. Person-centred planning is a process that takes time and usually starts with a planning meeting. The key features of person-centred planning are shown in Box 14.12 and some are described in more detail below.

[Resources: Sanderson H 2002 Person centred planning. In: Gates B (ed) Learning disabilities, toward inclusion. 4th edn. Churchill Livingstone, Edinburgh; People First Manchester and Liverpool 1997 Our plan for planning. People First, Manchester]

Person-centred planning

Consulting the person throughout the planning process

If the person with learning disabilities has been involved with planning before, it is sensible to talk to them about how they would like to plan, e.g. whether they want a meeting and, if so, what kind of meeting and how they want to be involved. If they are new to planning, it is important to spend time explaining the purpose of planning and looking at different options. Box 14.13 summarizes how this process may work for an individual.

Craig’s story

Craig, who is 32 years old, lives at home assisted by his family and a group of part-time support workers. He has learning disabilities, is unable to speak and moves his hands and eyes to communicate. Craig attends a day centre three times a week. While at the day centre Craig sleeps a lot. His family and support workers describe him as witty and lively, but staff at the day centre find him disinterested and uncommunicative.

It was decided to make a plan for the future. Craig’s family asked him who he would like to be involved in the planning. Craig invited staff from the day centre. He asked for the two members of staff he felt most comfortable with. They were happy to come as they thought that Craig might not be getting the most from his time in the day centre. The meeting was held in Craig’s home and took up most of an evening.

During the planning meeting, Craig communicated to the group that he was interested in learning to play a musical instrument, finding a girlfriend and making changes that would allow him to make new friends. It was the first time that anyone had realized Craig had these ambitions and no one thought it was impossible to achieve them. Staff from the day centre then recognized that the reason Craig was different at the day centre was probably because he felt he did not know the staff too well and they did not know fully how to communicate with him.

The people who attended the meeting then worked together to change things. Craig now attends a weekly music class with a support worker. One of the staff from the day centre has spent time in Craig’s home to get a better understanding of his needs. The next stage of the plan is to find other activities that interest Craig and, like the music class, he will attend these with a support worker. In time, it is planned that he will reduce the time he spends at the day centre as other activities increase. Things are slowly changing for the better and Craig is now involved in every decision that is made.

Student activity

Visit the Scottish Consortium for Learning Disability website (www.scld.org.uk) and find out how one agency is trying to achieve the goals of the government strategies for people with learning disability.

The person chooses who to involve

Unlike traditional planning, it is for the person with learning disabilities to decide who they want to include in the planning process and how. This is easy to say but, with existing services, this is very different from the way meetings are typically organized. If the people around those with learning disabilities cannot find a way to help them make and communicate that decision for themselves, then they must decide in good faith who they think the person would want to involve. A good starting point is thinking about ‘people who know and care about the person’ which may well yield a different answer from ‘people who provide a service to this person’.

The person chooses the setting and timing of meetings

If a meeting takes place it should be at a time convenient to the person with learning disabilities, with the people they wish to invite and be in a place where they feel ‘at home’. The planning should be carried out in a way that is accessible to the person with learning disabilities. Graphics, tapes, videos or photos are often used.

Approaches in mental health nursing

In common with learning disability nursing, mental health nursing has also been driven by policy development to become user focused. The trend towards community-based care continues with many services provided by mental health nurses. There is emphasis on caring for people who have enduring mental illness such as schizophrenia. The shift away from institutional care has led to examination and scrutiny of approaches to planning and implementation of care. The following key principles underpin care planning in mental health settings:

In mental health nursing the approach used is also person centred (Barker 2001b). A person-centred approach builds on the seminal work of Peplau (1952) who espoused the strengths of the therapeutic relationship between the nurse and the person. Building on the work of Peplau is the notion of the professional relationships the nurse has with other professionals as well as the need for a person-centred nurse/person relationship that is not driven by the power of the nurse (Barker 2001b).

The Tidal model

The Tidal model (Barker 2001b) was developed from a study into the need for mental health nursing. It is a multidimensional approach to the provision of mental health care. The philosophy is that people can recover from the experience of mental health problems and that nurses can assist clients to return to their daily life. Therefore the philosophy is about helping people to cope with their problems and find solutions through their own experiences. As it is not about ‘fixing them’, this model has an empowering approach.

The Tidal model represents the unique contribution that nurses make to the care of people with mental health problems, though it also acknowledges the close relationships with other health and social care practitioners. One of its features is that a care continuum exists. The care continuum straddles the primary and secondary care settings with the premise that the needs of the person should be the focus of care and not the setting. The assumption is that the need for nursing lies wherever the person is, rather than within the ‘compartments’ of primary or secondary care. Other features of the model are:

The role of the nurse is twofold:

Barker (1996, p. 236) illustrates the core basis of the Tidal model:

Life is a journey undertaken on an ocean of experience. All human development, including the experience of illness and health, involves discoveries made on the journey across that ocean of experience.

At critical points in the life journey the person experiences storms or even piracy (crisis). At other times the ship may begin to take in water and the person may face the prospect of drowning or shipwreck (breakdown). The person may need to be guided to a safe haven to undertake repairs, or to recover from the trauma (rehabilitation). Once the ship is made intact or the person has regained the necessary sea legs, the ship may set sail again, aiming to put the person back on the life course (recovery).

Barker (1996) asserts that there are three dimensions within the model:

The aim of assessment and planning within the three dimensions is to allow the person to verbalize their own experience to determine how their needs can be met. The narrative basis of the model suggests that the ‘self’ of the person-as-the-expert can be explored through careful inquiry by the nurse. Therefore, the therapeutic relationship between the nurse and person is crucial to allow construction of the person’s experience through narratives. The care plan should document the needs of the person expressed in their own words rather than in professional language or in the third person. Thus the lived experience of the person can be documented.

The aim of the Tidal model, using a person-centred approach, dovetails with best practice statements regarding engagement with the person to work towards person-centred care (Barker 2001b, NHS Quality Improvement Scotland 2004).

Further information about approaches to mental health nursing can be found in the Useful Websites list on page 388.

Approaches to planning care for children

Partnership in care is advocated as the desired approach to caring for children recommended in the National Service Framework (DH 2003). Every Child Matters, the government strategy that followed The Children Act (2004), provides further aspirations and policies about the integrated partnership approach to caring for children across society (see Chs 3, 6). The services that children require change as they develop and encounter illness or vulnerability. The key to providing excellent care is in the relationships that develop between the nurse, the child and the family as well as those that the nurse has with other professional agencies and services. Respecting parents and the family means recognizing that:

The Nottingham model (Smith 1995) and Casey’s partnership model (Casey 1988) are prominent in children’s nursing. Both models are based on respect for the wishes of the family and negotiation of care needs. The main differences between them are that the Nottingham model includes the child and the family as ‘the client’, whereas Casey views the child as ‘the client’. However, a partnership approach is central to them both.

The Nottingham model

While the philosophy of this model includes the family as partners, it is still important to include the child in the decision-making process where possible. By doing this, dignity and respect for the child are maintained. As the model uses a holistic approach, taking account of the wider influences that can affect a child’s health, the family’s perception of health in relation to the child should be assessed when the history is being taken during admission.

Hospital admission can be very disruptive, not only to the child but also to the wider family. The child may have alteration in normal functioning that spans the physical, psychological, social, emotional and/or environmental dimensions of life (DH 2003). To minimize the trauma associated with hospital admission, a welcoming environment is necessary to enable the process of negotiated care to be established. A routine that allows a child’s normal activities to be undertaken in relation to activities of living is encouraged, particularly in respect of education and recreation. Play is an important element of the nursing care provided (see Chs 8, 9) and forms an important aspect of pain management (see Ch. 23). The family or main caregivers should be considered the experts on young children. Their knowledge of the child’s behaviour and level of independence can be communicated to the nurse and the plan of care is developed jointly. Assisting the family to retain some control over their lives, while meeting the needs of their child, is desirable. This often means that the family will be involved in direct care giving. To provide this type of family-centred care, the family must have clear guidelines about what to expect from the nurse. Therefore, nurses caring for children need to be excellent communicators. Older children and young people are often the experts about their own conditions and associated care (DH 2000).

If hospital admissions are planned (elective), some of the fear associated with hospital admission can be allayed. Receiving written and verbal information prior to admission may help reduce anxiety for the child and their family. It may also reduce recovery times. Pre-admission schemes can also reduce some of the fears and anxiety by providing an opportunity to visit the environment and meet with some of the staff (Smith et al 2002). The Nottingham model follows the steps of the nursing process from assessment, planning, implementing and evaluating care.

Negotiated care

Negotiated care refers to a two-way process between the nurse and the child and their family. The relationship between these people should be based on mutual trust and respect. With each person’s contribution being equally valued, an agreed plan of care can be made. The process of negotiation begins at the assessment stage. The level of family involvement should be frequently reassessed as the situation may change, as can the needs of the family. Thus parental participation in direct care delivery may vary over time.

Documentation and record keeping

Documentation and record keeping apply to every aspect of nursing intervention. Accurate record keeping is an essential and integral part of professional practice and personal professional development (NMC 2005; see also Ch. 7). Records may be required for legal purposes (see Ch. 6) and audit (Ch. 5). The quality and accuracy of record keeping can reflect standards of care.

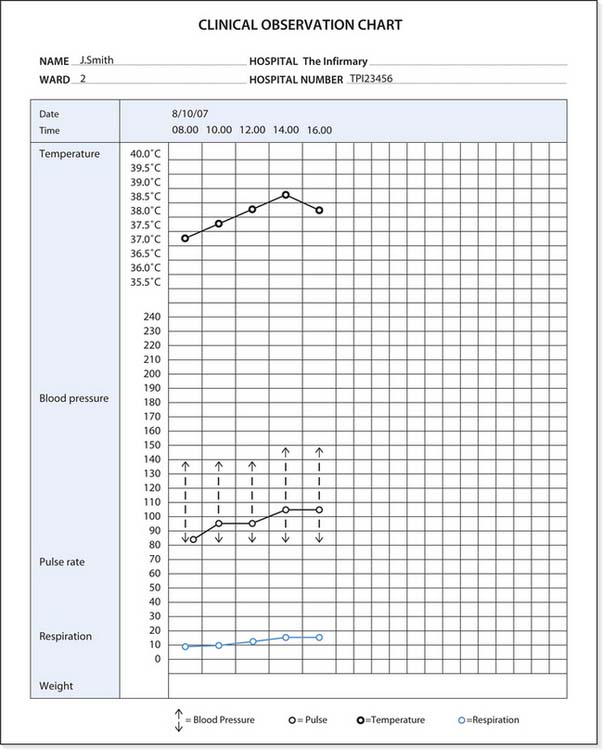

Timely and accurate records may highlight changes in a patient’s/client’s condition by providing a graph-ical record of their health status, demonstrating trends and changes over time, e.g. with charts used for baseline observations (see Fig. 14.9, p. 376).

Vital signs

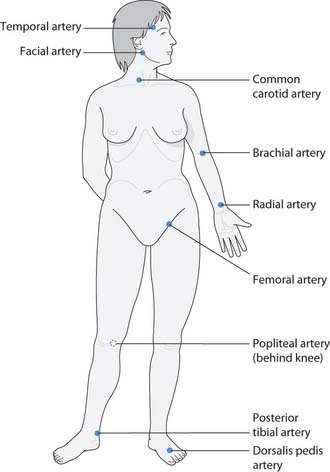

Assessment of a person’s health status includes the measurement of vital signs that include temperature, blood pressure, pulse and respiratory rate. This section uses an evidence-based approach to measuring vital signs. A number of factors can influence the information obtained from these measurements, including changes to the environmental temperature or metabolic activity and exercise or eating. Nursing care of people with abnormally high and low body temperature is explained. At the end of this section, measurement of height and weight is described. These measurements indicate general health or underlying illness that may require investigation, monitoring and/or treatment.

Nurses measure, record and interpret vital signs and use the information to plan and implement appropriate nursing interventions as well as to evaluate the effect of care and treatment. Vital signs are usually all measured at the same time.

Body temperature

Core body temperature in health is in the range of 36.4–37.38C 6 0.28C. It is measured in degrees (8) Celsius (C), and is relatively constant. Body temperature is an indicator of the balance between the amount of heat being generated by cellular processes and the excess that is lost. Efficient cellular metabolism requires the maintenance of body core temperature and organs that are located within the core, such as the brain, heart and liver, function best around 378C. This is called the ‘set point’ and serious problems occur if temperature deviates much from this.

Distribution of body heat

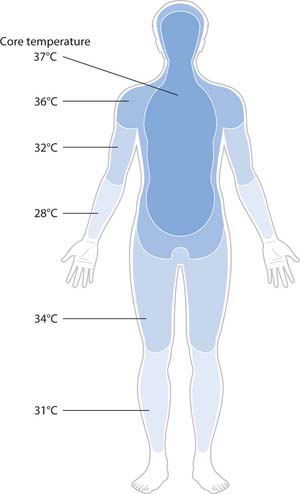

Heat is generated by cellular metabolism; therefore areas of high metabolic activity such as the liver or exercising skeletal muscle have the highest temperatures. The locations that are considered to best reflect the body’s inner or ‘core’ temperature are the heart and brain. Peripheral regions, which are nearer to the environment, are cooler as they are more exposed to the lower ambient temperature outside the body. Temperature sensors placed on the skin surface estimate peripheral or ‘shell’ body temperature. Body core temperature (BCT) can be measured using a variety of instruments that may be placed in sites such as the ear canal, oral cavity, axilla or rectum. Figure 14.6 shows body temperature at different sites.

Fig. 14.6 Body temperature at different sites

(reproduced with permission from Brooker & Nicol 2003)

Heat balance

Maintaining body temperature within the normal range requires a balance between heat produced by the body and its loss to the environment. Heat balance is achieved through the interplay of mechanisms that conserve heat and others that promote heat loss.

Heat conservation

When sensors in the hypothalamus detect a fall in temperature they trigger a set of responses that promote heat conservation. These include:

Behavioural responses include putting on more clothes, exercising or moving towards a source of heat.

Heat loss

If core temperature rises above the set point, the body initiates physiological mechanisms that promote heat transfer. These include:

Behavioural mechanisms activated by the brain also promote heat loss. These include taking off clothes or wearing lighter clothes, drinking cold fluids or lifting the arms away from the body.

Physiological influences on body core temperature

There are several factors that influence BCT, as outlined below.

Diurnal cycles

BCT varies throughout the day. Variations are normally within a range of 0.5–1.08C over 24 hours, with the highest point of 37.28C at around 6 pm and lowest (36.78C) around 6 am. People having their temperature measured daily should therefore have this carried out at the same time each day to avoid normal diurnal variations.

Age

In infants, temperature regulation is labile because their physiological heat-regulating mechanisms are immature, and this can continue until puberty. Babies and small children therefore need to be dressed appropriately for the environmental temperatures around them. Heat production is increased in infants and children due to deposits of brown fat around the neck, back and viscera (the organs within the abdominal cavity). The only role of brown fat is to generate heat, and therefore shivering is not usually observed in this age group. Children also have a higher basal metabolic rate than adults, due to increased tissue growth rates. The consequence of a higher metabolic rate is a higher mean BCT.

Older adults may have a lower mean BCT that is also more influenced by ambient temperature. Therefore, should an older person develop an infection, BCT may not rise significantly. Ageing processes tend to reduce muscle mass, which reduces heat production capability in older adults. Additionally, loss of subcutaneous tissue (insulating fat), reduced basal metabolic rate and altered vasoconstriction/vasodilatation mechanisms influence heat loss and production.

Environmental influences on body temperature

Environmental temperature extremes can raise or lower body temperature. The changes depend on the extent of exposure, air humidity and the presence of convection currents.

Care of people with temperature abnormalities

Body temperature can deviate from the normal range as a result of excess heat production, minimal heat loss or minimal heat production. It may:

Disorders such as heatstroke, hypothermia and frostbite may occur when environmental temperatures are extreme. The first aid for people with heatstroke and frostbite is outlined in this section.

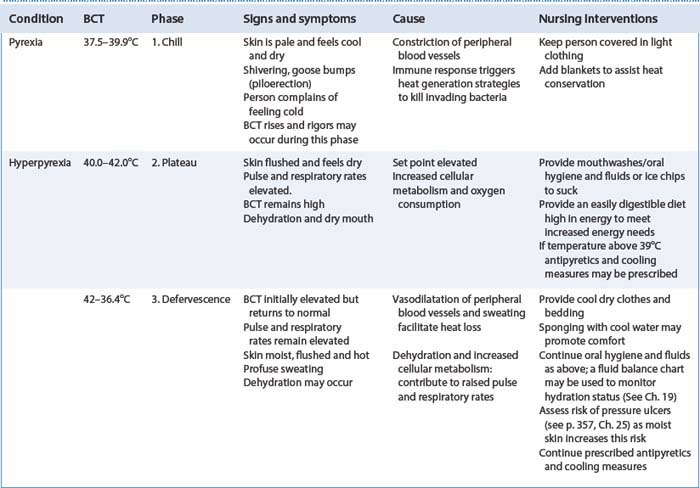

Caring for patients with pyrexia or hyperpyrexia

Pyrexia is present when elevated temperature readings have been recorded at different times throughout the day, rather than a single raised reading. Pyrexia is often caused by an infection and has three stages. The first stage, during which BCT rises, can induce vigorous shivering or ‘rigors’. Shivering generates metabolic heat with a subsequent rise in BCT, which the body uses to mount a response against the invading pathogen. The stages and the nursing care required are outlined in Table 14.1. Elevated BCT increases basal metabolic rate and oxygen consumption and, in hyperpyrexia, there is serious disruption of brain and other organ function. Children under the age of 5 years are prone to febrile seizures and the first aid needed is described Box 16.36 (p. 457).

Two major strategies can be used to manage elevated body temperature:

Table 14.2 Advantages and disadvantages of cooling interventions

| Cooling intervention | Advantages | Disadvantages |

|---|---|---|

| Fanning – rotary mobile fans blowing over body surface, using a variety of speeds | Perceived patient comfort | Shivering and vasoconstriction |

| Convenient | Spread of airborne microorganisms | |

| Cheap | No evidence to support use in ill patients | |

| Cool water bathing – sponging with cloths soaked in either ice-cool water or tepid water | No shivering | Time consuming |

| Reduction in BCT | Discomfort and vasoconstriction with iced cloths | |

| Ice cooling – ice packs applied to areas where major arteries are near the skin surface, e.g. axillae, groins, neck | Surface cooling on area surrounding pack | Vasoconstriction, which limits heat transfer from core to the skin causing heat conservation |

| Rapid cooling | ||

| Cooling blankets/mattresses – can be water filled and placed under patient, or air filled and put over patient | Rate of fever reduction faster than traditional methods | Expensive to buy or rent |

| Control over temperature setting | Uncomfortable, so generally only used on comatose patients | |

| Temperature controlled thermostat | No more effective than traditional methods |

Box 14.14  EVIDENCE-BASED PRACTICE

EVIDENCE-BASED PRACTICE

[Resource: Watts R, Robertson J, Thomas G 2003 The nursing management of fever in children: a systematic review. International Journal of Nursing Practice 9:51–58]

Cooling strategies for pyrexial children

Watts et al (2003) undertook a systematic review that considered the use and timing of cooling strategies used in the care of pyrexial children.

Main points

Conclusions

Aggressive forms of cooling such as the use of cooling mattresses or covering the whole body with ice are sometimes required for patients who develop temperatures above 418C as this may cause serious and sometimes fatal consequences.

Prolonged exposure to hot sunlight or high environmental temperatures can result in the development of a serious condition known as heatstroke where measured BCT can be as high as 458C. People at risk include:

Recognition of heatstroke and the necessary interventions are shown in Box 14.15.

Caring for patients with hypothermia

Hypothermia is present when BCT is below 358C. It is described as mild, moderate, severe or profound (see Table 14.3). Hypothermia usually occurs accidentally as a result of exposure to low environmental temperatures and people at the extremes of age are the most vulnerable. Awareness of and providing interventions that will minimize the risk factors for hypothermia can often prevent its occurrence. Risk factors in infants, adults and older adults are outlined in Box 14.16.

Table 14.3 Effects of hypothermia

| Description | Range (°C) | Clinical effects |

|---|---|---|

| Mild | 32–35 | Reduced metabolic rate that reduces oxygen consumption, slows down drug metabolism |

| Severe shivering | ||

| Pallor | ||

| BP, pulse and respirations begin to fall | ||

| Urine output increases due to diminished production of antidiuretic hormone | ||

| Mental confusion, hearing fades | ||

| Moderate | 28–31.9 | Myocardial irritability; cardiac arrest that may not respond to cardiac resuscitation |

| Unresponsive to environment | ||

| Loss of shivering response | ||

| Increased blood viscosity and clot thrombus formation | ||

| Severe | 20–27 | Unable to regulate temperature; loss of brain stem reflexes |

| Profound | <20 | Death |

Box 14.16 Risk factors for hypothermia

Infants

Adults

Hypothermia can also occur in hospital. For example, some anaesthetic drugs lower BCT, as do some interventions, e.g. infusing large volumes of unwarmed fluids or irrigating body cavities with cool fluids in theatre. Postoperatively it is therefore important that temperature is carefully assessed and monitored (see Ch. 24).

The physiological effects of hypothermia are outlined in Table 14.3 and patients require careful observation for their presence. Severe hypothermia requires treatment in a high dependency area or intensive care unit.

Restoring low BCT to normal requires careful management. The following parameters should be assessed:

Management involves warming, which can be active or passive depending on the severity of hypothermia; however, it is dangerous to rewarm a patient too quickly. In mild hypothermia the aim is to increase BCT by 1–28C per hour and this can be achieved by:

In frostbite, peripheral blood flow is reduced in tissues that are exposed to freezing temperatures. This is an attempt to conserve heat by limiting heat loss from the skin. Frostbite or cold injury develops as the poor peripheral blood supply causes injury or permanent destruction of the tissue as it becomes deprived of oxygen and ice crystals form in the tissues. If left untreated, gangrene (death of tissues due in an inadequate blood supply) will occur. The parts of the body most at risk of developing frostbite are the facial features such as the ears, nose and cheeks, and extremities such as the hands, fingers, feet and toes.

The following situations or circumstances can lead to the development of frostbite:

Recognition and first aid management of frostbite are described in Box 14.17.

[Adapted from Mohun 2002]

Frostbite

Body temperature assessment tools

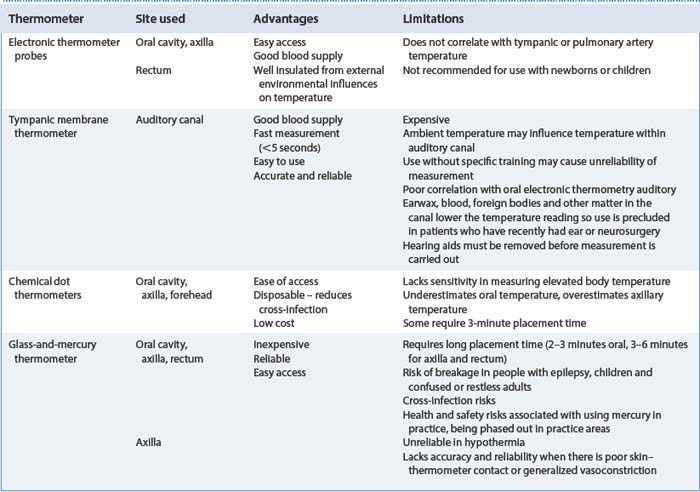

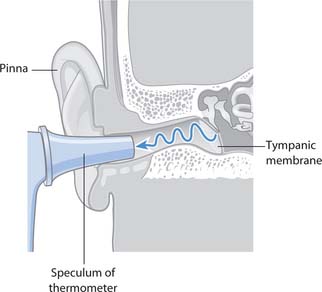

Estimation of body core or peripheral temperature can be made at different sites using a variety of instruments. Instruments include tympanic membrane probes, electronic thermometers, disposable chemical dot thermometers and the glass-and-mercury thermometer.

Each device has advantages and limitations (see Table 14.4) and therefore individual needs must be assessed. Should intervention to manage abnormal body temperature be required, it is necessary to select a thermometer that can be used to make frequent or continuous measurements. This must be accurate and reliable at the top and bottom of the scale, and be appropriate for the person’s age and individual needs.

Electronic thermometers

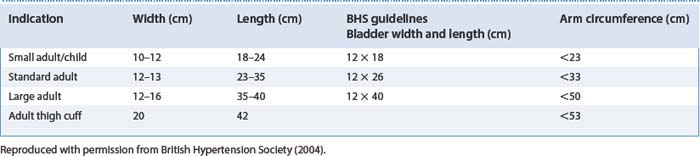

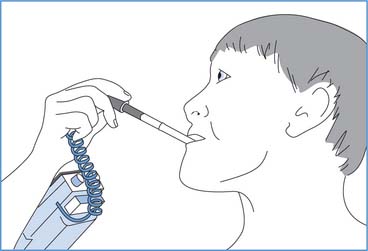

The electronic thermometer (Fig. 14.7) usually consists of a battery-operated device that displays a digital readout of the temperature measured during a preset recording time, usually between 20 and 50 seconds. Attached to the device by a cable is a probe, which is most commonly placed in the mouth, axilla or rectum. Protecting rigid probes with a plastic disposable cover and cleaning them between each use prevents cross-infection. Disposable flexible probes may be used for continuous temperature monitoring which has been found to produce reliable information (Henker & Coyne 1995, Giuliano et al 2000).