Sensory Alterations

• Differentiate among the processes of reception, perception, and reaction to sensory stimuli.

• Discuss the relationship of sensory function to an individual’s level of wellness.

• Discuss common causes and effects of sensory alterations.

• Discuss common sensory changes that normally occur with aging.

• Identify factors to assess in determining a patient’s sensory status.

• Identify nursing diagnoses relevant to patients with sensory alterations.

• Develop a plan of care for patients with sensory deficits.

• List interventions for preventing sensory deprivation and controlling sensory overload.

• Describe conditions in a health care agency or patient’s home that you can modify to promote meaningful sensory stimulation.

• Discuss ways to maintain a safe environment for patients with sensory deficits.

http://evolve.elsevier.com/Potter/fundamentals/

Imagine the world without sight, hearing, or the ability to feel objects or sense aromas around you. Human beings rely on a variety of sensory stimuli to give meaning and order to events occurring in their environment. The senses form the perceptual base of our world. Stimulation comes from many sources in and outside the body, particularly through the senses of sight (visual), hearing (auditory), touch (tactile), smell (olfactory), and taste (gustatory). The body also has a kinesthetic sense that enables a person to be aware of the position and movement of body parts without seeing them. Stereognosis is a sense that allows a person to recognize the size, shape, and texture of an object. The ability to speak is not a sense but it is similar in that some patients lose the ability to interact meaningfully with other human beings. Meaningful stimuli allow a person to learn about the environment and are necessary for healthy functioning and normal development. When sensory function is altered, a person’s ability to relate to and function within the environment changes drastically.

Many patients seeking health care have preexisting sensory alterations. Others develop them as a result of medical treatment (e.g., hearing loss from antibiotic use or hearing or visual loss from brain tumor removal) or hospitalization. The health care environment is a place of unfamiliar sights, sounds, and smells and minimal contact with family and friends. If patients feel depersonalized and are unable to receive meaningful stimuli, serious sensory alterations sometimes develop.

As a nurse, you meet the needs of patients with existing sensory alterations and recognize patients most at risk for developing sensory problems. You also help patients who have partial or complete loss of a major sense to find alternate ways to function safely within their environment.

Scientific Knowledge Base

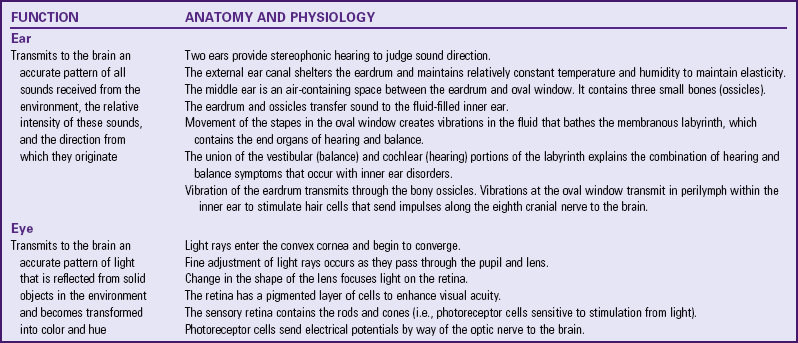

Normally the nervous system continually receives thousands of bits of information from sensory nerve organs, relays the information through appropriate channels, and integrates the information into a meaningful response. Sensory stimuli reach the sensory organs to elicit an immediate reaction or present information to the brain to be stored for future use. The nervous system must be intact for sensory stimuli to reach appropriate brain centers and for an individual to perceive the sensation. After interpreting the significance of a sensation, the person is then able to react to the stimulus. Table 49-1 summarizes normal hearing and vision.

Reception, perception, and reaction are the three components of any sensory experience (see Chapter 43). Reception begins with stimulation of a nerve cell called a receptor, which is usually for only one type of stimulus such as light, touch, or sound. In the case of special senses, the receptors are grouped close together or located in specialized organs such as the taste buds of the tongue or the retina of the eye. When a nerve impulse is created, it travels along pathways to the spinal cord or directly to the brain. For example, sound waves stimulate hair cell receptors within the organ of Corti in the ear, which causes impulses to travel along the eighth cranial nerve to the acoustic area of the temporal lobe. Sensory nerve pathways usually cross over to send stimuli to opposite sides of the brain.

The actual perception or awareness of unique sensations depends on the receiving region of the cerebral cortex, where specialized brain cells interpret the quality and nature of sensory stimuli. When a person becomes conscious of a stimulus and receives the information, perception takes place. Perception includes integration and interpretation of stimuli based on the person’s experiences. A person’s level of consciousness influences perception and interpretation of stimuli. Any factors lowering consciousness impair sensory perception. If sensation is incomplete such as blurred vision or if past experience is inadequate for understanding stimuli such as pain, the person can react inappropriately to the sensory stimulus.

It is impossible to react to all stimuli entering the nervous system. The brain prevents sensory bombardment by discarding or storing sensory information. A person usually reacts to stimuli that are most meaningful or significant at the time. However, after continued reception of the same stimulus, a person stops responding, and the sensory experience goes unnoticed. For example, a person concentrating on reading a good book is not aware of background music. This adaptability phenomenon occurs with most sensory stimuli except for those of pain.

The balance between sensory stimuli entering the brain and those actually reaching a person’s conscious awareness maintains a person’s well-being. If an individual attempts to react to every stimulus within the environment or if the variety and quality of stimuli are insufficient, sensory alterations occur.

Sensory Alterations

The most common types of sensory alterations are sensory deficits, sensory deprivation, and sensory overload. When a patient suffers from more than one sensory alteration, the ability to function and relate effectively within the environment is seriously impaired.

Sensory Deficits

A deficit in the normal function of sensory reception and perception is a sensory deficit. A person loses a sense of self with impaired senses. Initially he or she withdraws by avoiding communication or socialization with others in an attempt to cope with the sensory loss. It becomes difficult for the person to interact safely with the environment until he or she learns new skills. When a deficit develops gradually or when considerable time has passed since the onset of an acute sensory loss, a person learns to rely on unaffected senses. Some senses may even become more acute to compensate for an alteration. For example, a blind patient develops an acute sense of hearing to compensate for visual loss.

Patients with sensory deficits often change behavior in adaptive or maladaptive ways. For example, a patient with a hearing impairment turns the unaffected ear toward the speaker to hear better, whereas another patient avoids people because he or she is embarrassed about not being able to understand what other people say. Box 49-1 summarizes common sensory deficits and their influence on those affected.

Sensory Deprivation

The reticular activating system in the brainstem mediates all sensory stimuli to the cerebral cortex; thus patients are able to receive stimuli even while sleeping deeply. Sensory stimulation must be of sufficient quality and quantity to maintain a person’s awareness. Three types of sensory deprivation are reduced sensory input (sensory deficit from visual or hearing loss), the elimination of patterns or meaning from input (e.g., exposure to strange environments), and restrictive environments (e.g., bed rest) that produce monotony and boredom (Ebersole et al., 2008).

There are many effects of sensory deprivation (Box 49-2). In adults the symptoms are similar to psychological illness, confusion, symptoms of severe electrolyte imbalance, or the influence of psychotropic drugs. Therefore always be aware of a patient’s existing sensory function and the quality of stimuli within the environment.

Sensory Overload

When a person receives multiple sensory stimuli and cannot perceptually disregard or selectively ignore some stimuli, sensory overload occurs. Excessive sensory stimulation prevents the brain from responding appropriately to or ignoring certain stimuli. Because of the multitude of stimuli leading to overload, a person no longer perceives the environment in a way that makes sense. Overload prevents meaningful response by the brain; the patient’s thoughts race, attention scatters in many directions, and anxiety and restlessness occur. As a result, overload causes a state similar to that produced by sensory deprivation. However, in contrast to deprivation, overload is individualized. The amount of stimuli necessary for healthy function varies with each individual. People are often subject to environmental overload more at one time than another. A person’s tolerance to sensory overload varies with level of fatigue, attitude, and emotional and physical well-being.

The acutely ill patient easily experiences sensory overload. The patient in constant pain or who undergoes frequent monitoring of vital signs is at risk. Multiple stimuli combine to cause overload even if the nurse offers a comforting word or provides a gentle back rub. Some patients do not benefit from nursing intervention because their attention and energy are focused on more stressful stimuli. Another example is a patient who is hospitalized in an intensive care unit (ICU), where the activity is constant. Lights are always on. Patients can hear sounds from monitoring equipment, staff conversations, equipment alarms, and the activities of people entering the unit. Even at night an ICU is very noisy.

It is easy to confuse the behavioral changes associated with sensory overload with mood swings or simple disorientation. Look for symptoms such as racing thoughts, scattered attention, restlessness, and anxiety. Patients in ICUs sometimes resort to constantly fingering tubes and dressings. Constant reorientation and control of excessive stimuli become an important part of a patient’s care.

Nursing Knowledge Base

Factors Influencing Sensory Function

Many factors influence the capacity to receive or perceive stimuli. All are conditions or situations that you manage when delivering care.

Age

Infants and children are at risk for visual and hearing impairment because of a number of genetic, prenatal, and postnatal conditions. A concern with high-risk neonates is that early, intense visual and auditory stimulation can adversely affect visual and auditory pathways and alter the developmental course of other sensory organs (Hockenberry and Wilson, 2011). Visual changes during adulthood include presbyopia and the need for glasses for reading. These changes usually occur from ages 40 to 50. In addition, the cornea, which assists with light refraction to the retina, becomes flatter and thicker. These aging changes lead to astigmatism. Pigment is lost from the iris, and collagen fibers build up in the anterior chamber, which increases the risk of glaucoma by decreasing the resorption of intraocular fluid. Other normal visual changes associated with aging include reduced visual fields, increased glare sensitivity, impaired night vision, reduced depth perception, and reduced color discrimination.

Hearing changes begin at the age of 30. Changes associated with aging include decreased hearing acuity, speech intelligibility, and pitch discrimination. Low-pitched sounds are easiest to hear, but it is difficult to hear conversation over background noise. It is also difficult to discriminate the consonants (z, t, f, g) and high-frequency sounds (s, sh, ph, k). Vowels that have a low pitch are easiest to hear. Speech sounds are distorted, and there is a delayed reception and reaction to speech. A concern with normal age-related sensory changes is that older adults with a deficit are sometimes inappropriately diagnosed with dementia (Ebersole et al., 2008).

Gustatory and olfactory changes begin around age 50 and include a decrease in the number of taste buds and sensory cells in the nasal lining. Reduced taste discrimination and sensitivity to odors are common.

Proprioceptive changes common after age 60 include increased difficulty with balance, spatial orientation, and coordination. Older adults cannot avoid obstacles as quickly, and the automatic response to protect and brace oneself when falling is slower. Older adults experience tactile changes, including declining sensitivity to pain, pressure, and temperature secondary to peripheral vascular disease and neuropathies.

Meaningful Stimuli

Meaningful stimuli reduce the incidence of sensory deprivation. In the home meaningful stimuli include pets, music, television, pictures of family members, and a calendar and clock. The same stimuli need to be present in health care settings. Note whether patients have roommates or visitors. The presence of others offers positive stimulation. However, a roommate who constantly watches television, persistently tries to talk, or continuously keeps lights on contributes to sensory overload. The presence or absence of meaningful stimuli influences alertness and the ability to participate in care.

Amount of Stimuli

Excessive stimuli in an environment causes sensory overload. The frequency of observations and procedures performed in an acute health care setting are often stressful. If a patient is in pain or restricted by a cast or traction, overstimulation frequently is a problem. In addition, a room that is near repetitive or loud noises (e.g., an elevator, stairwell, or nurses’ station) contributes to sensory overload.

Social Interaction

The amount and quality of social contact with supportive family members and significant others influence sensory function. The absence of visitors during hospitalization or residency in an extended care facility influences the degree of isolation a patient feels. This is a common problem in hospital intensive care settings, where visitation is often restricted. The ability to discuss concerns with loved ones is an important coping mechanism for most people. Therefore the absence of meaningful conversation results in feelings of isolation, loneliness, anxiety, and depression for a patient. Often this is not apparent until behavioral changes occur.

Environmental Factors

A person’s occupation places him or her at risk for hearing, visual, and peripheral nerve alterations. Individuals who have occupations involving exposure to high noise levels (e.g., factory or airport workers) are at risk for noise-induced hearing loss and need to be screened for hearing impairments. Hazardous noise is common in work settings and recreational activities. Noisy recreational activities that weaken hearing ability include target shooting and hunting, woodworking, and listening to loud music. Individuals who have occupations involving risk of exposure to chemicals or flying objects (e.g., welders) are at risk for eye injuries and need to be screened for visual impairments. Sports activities and consumer fireworks also place individuals at risk for visual alterations. Occupations that involve repetitive wrist or finger movements (e.g., heavy assembly line work) cause pressure on the median nerve, resulting in carpal tunnel syndrome. Carpal tunnel syndrome alters tactile sensation and is one of the most common industrial or work-related injuries. Patients at risk for carpal tunnel need to be carefully assessed for numbness, tingling, weakness, and pain.

A hospitalized patient is sometimes at risk for sensory alterations as a result of exposure to environmental stimuli or a change in sensory input. Patients who are immobilized by bed rest or who have a chronic disability are unable to experience all of the normal sensations of free movement. Another group at risk includes patients isolated in a health care setting or at home because of conditions such as active tuberculosis (see Chapter 28). These patients stay in private rooms and are often unable to enjoy normal interactions with visitors.

Cultural Factors

Certain sensory alterations occur more commonly in select ethnic groups. Analysis of data from the African Descent and Glaucoma Evaluation study (ADAGES) showed that people of African ethnicity perform significantly worse than people of European descent on tests of visual function (Racette et al., 2010). Cultural disparities in vision impairment are significant, in part because visual impairment may be indirectly associated with an increased risk of suicide through poor self-rated health (Lam et al., 2008). Box 49-3 summarizes additional sensory alterations that are associated with a patient’s cultural heritage.

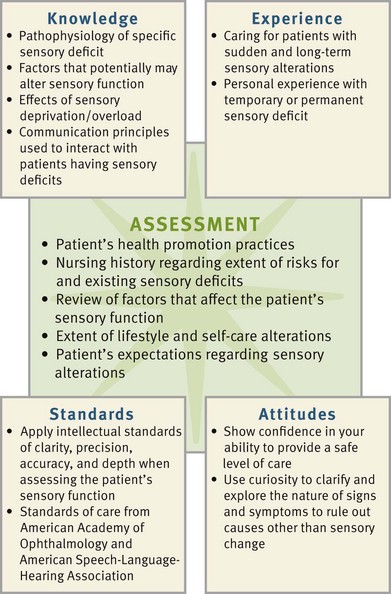

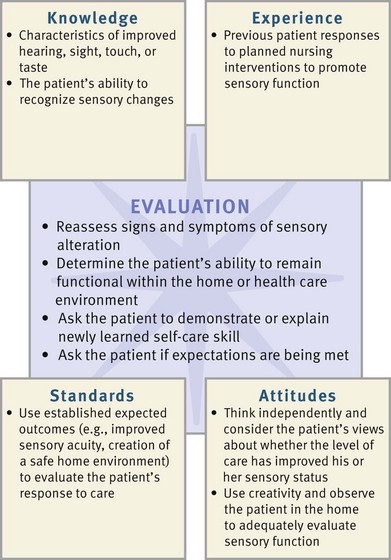

Critical Thinking

Successful critical thinking requires a synthesis of knowledge and information gathered from patients, experience, critical thinking attitudes, and intellectual and professional standards. Clinical judgments require you to anticipate the information necessary, analyze the data, and make decisions regarding patient care. Patients’ conditions are always changing. During assessment (Fig. 49-1) consider all critical thinking elements that help you make appropriate nursing diagnoses. In the case of sensory alterations, integrate knowledge of the pathophysiology of sensory deficits, factors that affect sensory function, and therapeutic communication principles. This knowledge enables you to conduct appropriate assessments, anticipate what to recognize when a patient describes a sensory problem, and make judgments of any abnormalities. For example, knowing the typical symptoms caused by a cataract helps you recognize the pattern of visual changes that a patient with cataracts reports.

Previous experiences in caring for patients with sensory deficits enable nurses to recognize limitations in function in each new patient and how they affect the patient’s ability to carry out daily activities. For example, after caring for a patient with a hearing impairment, you are able to conduct a more effective assessment of the next patient by using approaches that promote the patient’s ability to hear your questions.

When critical thinking attitudes and standards are applied during assessment, they ensure a thorough and accurate database from which to make decisions. For example, perseverance is necessary to learn details about how visual changes influence a patient’s ability to socialize. Evidence-based standards of care and practice such as those from the American Academy of Ophthalmology and the American Speech-Language-Hearing Association provide criteria for screening sensory problems and establishing standards for competent, safe, effective care and practice. Use critical thinking to conduct a thorough assessment and then plan, implement, and evaluate care that enables the patient to function safely and effectively (Box 49-4).

Nursing Process

Apply the nursing process and use a critical thinking approach in your care of patients. The nursing process provides a clinical decision-making approach for you to develop and implement an individualized plan of care for your patients.

Assessment

During the assessment process, thoroughly assess each patient and critically analyze findings to ensure that you make patient-centered clinical decisions required for safe nursing care.

Through the Patient’s Eyes

When conducting an assessment, value the patient as a full partner in planning, implementing, and evaluating care. Patients are often hesitant to admit sensory losses. Therefore start gathering information by establishing a therapeutic rapport with the patient. Elicit his or her values, preferences, and expectations with regard to his or her sensory impairment. Many patients have a definite plan as to how they want their care delivered. Some patients expect caregivers to recognize and appropriately manage and adjust their environment to meet their sensory needs. This includes helping the patient learn and adapt to a changed lifestyle based on the specific sensory impairment. Determine from the patient which interventions have been helpful in the past in the management of limitations. Assess the patient’s expertise with his or her own health and symptoms. Always remember that patients with sensory alterations have strengthened their other senses and expect caregivers to anticipate their needs (e.g., for safety and security).

When assessing a patient with or at risk for sensory alteration, first consider the pathophysiology of existing deficits and the factors influencing sensory function to anticipate how to approach his or her assessment. For example, if a patient has a hearing disorder, adjust your communication style and focus the assessment on relevant criteria related to hearing deficits. Collect a history that also assesses the patient’s current sensory status and the degree to which a sensory deficit affects the patient’s lifestyle, psychosocial adjustment, developmental status, self-care ability, health promotion habits, and safety. Also focus the assessment on the quality and quantity of stimuli within the patient’s environment.

Persons at Risk

Older adults are a high-risk group because of normal physiological changes involving sensory organs. However, be careful not to automatically assume that a patient’s sensory problem is related to advancing age. For example, adult sensorineural hearing loss is often caused by exposure to excess and prolonged noise or metabolic, vascular, and other systemic alterations. Some patients benefit from a referral to an audiologist or otolaryngologist if assessment reveals serious hearing problems.

Other individuals at risk for sensory alterations include those living in a confined environment such as a nursing home. Although most quality nursing homes or centers offer meaningful stimulation through group activities, environmental design, and mealtime gatherings, there are exceptions. The individual who is confined to a wheelchair, suffers from poor hearing and/or vision, has decreased energy, and avoids contact with others is at significant risk for sensory deprivation. If the environment creates monotony, the individual is less able to learn and think. Patients who are acutely ill are also at risk because of an unfamiliar and unresponsive environment. This does not mean that all hospitalized patients have sensory alterations. However, you need to carefully assess patients subjected to continued sensory stimulation (e.g., ICU settings, long-term hospitalization, or multiple therapies). Assess the patient’s environment within both the health care setting and the home, looking for factors that pose risks or need adjustment to provide safety and more stimulation.

Sensory Alterations History

The nursing history includes assessment of the nature and characteristics of sensory alterations or any problem related to an alteration (Box 49-5). When taking the history, consider the ethnic or cultural background of the patient because certain alterations are higher in some cultural groups.

During the history it is useful to assess the patient’s self-rating for a sensory deficit by asking, “Rate your hearing as excellent, good, fair, poor, or bad.” Then, based on the patient’s self-rating, explore his or her perception of a sensory loss more fully. This provides an in-depth look at how the sensory loss influences the patient’s quality of life. In the case of hearing problems, a screening tool such as the Hearing Handicap Inventory for the Elderly (HHIE-S) effectively identifies patients needing audiological intervention. The HHIE-S is a 5-minute, 10-item questionnaire that assesses how the individual perceives the social and emotional effects of hearing loss. The higher the HHIE-S score, the greater the handicapping effect of a hearing impairment.

A nursing history also reveals any recent changes in a patient’s behavior. Frequently friends or family are the best resources for this information. Ask the family the following questions:

Mental Status

Assessment of mental status is valuable when you suspect sensory deprivation or overload. Observation of a patient during history taking, during the physical examination (see Chapter 30), and while providing nursing care offers valuable data about key patient behaviors and his or her mental status. Observe the patient’s physical appearance and behavior, measure cognitive ability, and assess his or her emotional status. The Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE) is a tool you can use to measure disorientation, change in problem-solving abilities, and altered conceptualization and abstract thinking (see Chapter 30). For example, a patient with severe sensory deprivation is not always able to carry on a conversation, remain attentive, or display recent or past memory. An important step toward preventing cognition-related disability is education by nurses about disease process, available services, and assistive devices.

Physical Assessment

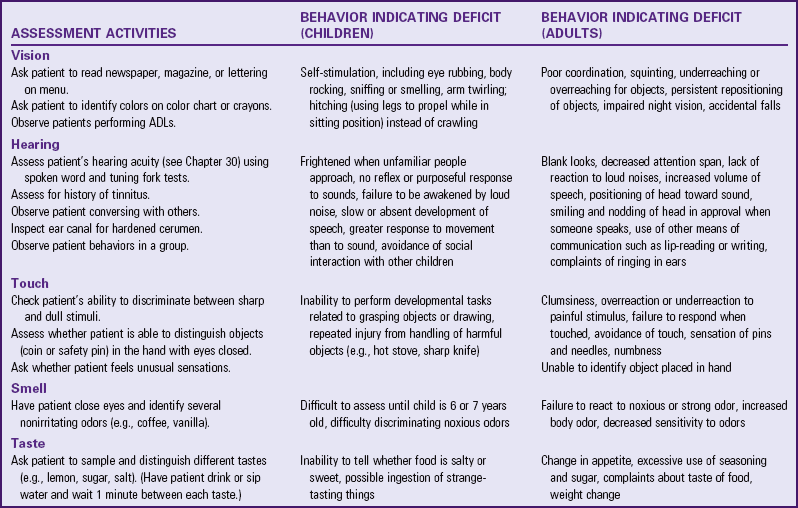

To identify sensory deficits and their severity, use physical assessment techniques to assess vision, hearing, olfaction, taste, and the ability to discriminate light touch, temperature, pain, and position (see Chapter 30). Table 49-2 summarizes specific assessment techniques for identifying sensory deficits. You gather more accurate data if the examination room is private, quiet, and comfortable for the patient. In addition, rely on personal observation to detect sensory alterations. Patients with a hearing impairment may seem inattentive to others, respond with inappropriate anger when spoken to, believe people are talking about them, answer questions inappropriately, have trouble following clear directions, and have monotonous voice quality and speak unusually loud or soft.

Ability to Perform Self-Care

Assess patients’ functional abilities in their home environment or health care setting, including the ability to perform feeding, dressing, grooming, and toileting activities. For example, assess whether a patient with altered vision is able to find items on a meal tray and read directions on a prescription. Also determine a patient’s ability to perform instrumental activities of daily living (IADLs), such as reading bills and writing checks, differentiating money denominations, and driving a vehicle at night. If a patient seems to have a sensory deficit, does he or she show concern for grooming? Does a patient’s loss of balance prevent rising from a toilet seat safely? Can a patient recovering from a stroke manipulate buttons or zippers for dressing? If a sensory alteration impairs a patient’s functional ability, providing resources within the home is a necessary part of discharge planning. Your findings may indicate the need for an occupational therapy consult.

Health Promotion Habits

Assess the daily routines that patients follow to maintain sensory function. What type of eye and ear care is a part of the patient’s daily hygiene? For individuals who participate in sports (e.g., racquetball) or recreational activities (e.g., motorcycle riding) or who work in a setting where ear or eye injury is a possibility (e.g., chemical exposure, welding, glass or stone polishing, or constant exposure to loud noise), determine if they wear safety glasses or hearing protective devices (HPDs). Do patients who use assistive devices such as eyeglasses, contact lenses, or hearing aids know how to provide daily care (see Chapter 39)? Do patients use the devices, and are they in proper working order?

It is also important to assess a patient’s adherence with routine health screening. When was the last time the patient had an eye examination or hearing evaluation? For adults routine screening of visual and hearing function is imperative to detect problems early. This is especially true in the case of glaucoma, which, if undetected, leads to permanent visual loss. Recommended screening guidelines usually occur on the basis of age. When a patient begins to show a hearing deficit, incorporate routine screening in regular examinations.

Environmental Hazards

Patients with sensory alterations are at risk for injury if their living environments are unsafe. For example, a patient with reduced vision cannot see potential hazards clearly. A patient with proprioceptive problems loses balance easily. A patient with reduced sensation cannot perceive hot versus cold temperatures. The condition of the home, the rooms, and the front and back entrances are often problematic to the patient with sensory alterations. Assess the patient’s home for common hazards, including the following:

• Uneven, cracked walkways leading to front/back door

• Extension and phone cords in the main route of walking traffic

• Loose area rugs and runners placed over carpeting

• Bathrooms without shower or tub grab bars

In the hospital environment caregivers often forget to rearrange furniture and equipment to keep paths from the bed and chair to the bathroom and entrance clear. It is helpful to walk into a patient’s room and look for safety hazards:

• Is the call light within easy, safe reach?

• Are intravenous (IV) poles on wheels and easy to move?

• Are suction machines, IV pumps, or drainage bags positioned so a patient can rise from a bed or chair easily?

An additional problem faced by patients who are visually impaired is the inability to read medication labels and syringe markings. Ask the patient to read a label to determine if he or she is able to read the dosage and frequency. If a patient has a hearing impairment, check to see whether the sounds of a doorbell, telephone, smoke alarm, and alarm clock are easy to discriminate.

Communication Methods

To understand the nature of a communication problem, you need to know whether a patient has trouble speaking, understanding, naming, reading, or writing. Patients with existing sensory deficits often develop alternate ways of communicating. To interact with the patient and promote interaction with others, understand his or her method of communication (Fig. 49-2). Vision becomes almost a primary sense for people with hearing impairments.

Patients with visual impairments are unable to observe facial expressions and other nonverbal behaviors to clarify the content of spoken communication. Instead they rely on voice tones and inflections to detect the emotional tone of communication. Some patients with visual deficits learn to read Braille. Patients with aphasia have varied degrees of inability to speak, interpret, or understand language. Expressive aphasia, a motor type of aphasia, is the inability to name common objects or express simple ideas in words or writing. For example, a patient understands a question but is unable to express an answer. Sensory or receptive aphasia is the inability to understand written or spoken language. A patient is able to express words but is unable to understand questions or comments of others. Global aphasia is the inability to understand language or communicate orally.

The temporary or permanent loss of the ability to speak is extremely traumatic to an individual. Assess a patient’s alternate communication method and whether it causes anxiety. Patients who have undergone laryngectomies often write notes, use communication boards or laptop computers, speak with mechanical vibrators, or use esophageal speech. Patients with endotracheal or tracheostomy tubes have a temporary loss of speech. Most use a notepad to write their questions and requests. However, some patients become incapacitated and unable to write messages. Determine whether the patient has developed a sign-language system or symbols to communicate needs.

Social Support

Assess if a patient lives alone and whether family or friends frequently visit. It is important to assess the patient’s social skills and level of satisfaction with the support given by family and friends. Is the patient satisfied with the support available? Is he or she able to solve problems with family members? Is there a family caregiver who offers support when the patient requires assistance as a result of a sensory loss? The long-term effects of sensory alterations influence family dynamics and a patient’s willingness to remain active in society.

Use of Assistive Devices

Assess the use of assistive devices (e.g., use of a hearing aid or glasses) and the sensory effects for the patient. This includes learning how often the patient uses the devices daily, the patient’s or family caregiver’s method of cleaning, and the patient’s knowledge of what to do when a problem develops. When you identify that the patient has an assistive device, it is important to remember that, just because the individual has the assistive device, it does not mean that it works or that the patient uses it or benefits from it.

Other Factors Affecting Perception

Factors other than sensory deprivation or overload cause impaired perception (e.g., medications or pain). Assess the patient’s medication history, which includes prescribed and over-the-counter medications and herbal products. Also gather information regarding the frequency, dose, method of administration, and last time these medications were taken. Some antibiotics (e.g., streptomycin, gentamicin, and tobramycin) are ototoxic and permanently damage the auditory nerve, whereas chloramphenicol sometimes irritates the optic nerve. Opioid analgesics, sedatives, and antidepressant medications often alter the perception of stimuli. Conduct a thorough pain assessment (see Chapter 43) when you suspect that pain is causing perceptual problems.

Nursing Diagnosis

After assessment review all available data and look critically for patterns and trends suggestive of a health problem relating to sensory alterations (Box 49-6). Validate findings to ensure accuracy of the diagnosis. Determine the factor that likely causes the patient’s health problem. The etiology or related factor of a nursing diagnosis is a condition that nursing interventions can affect. The etiology needs to be accurate; otherwise nursing therapies are ineffective.

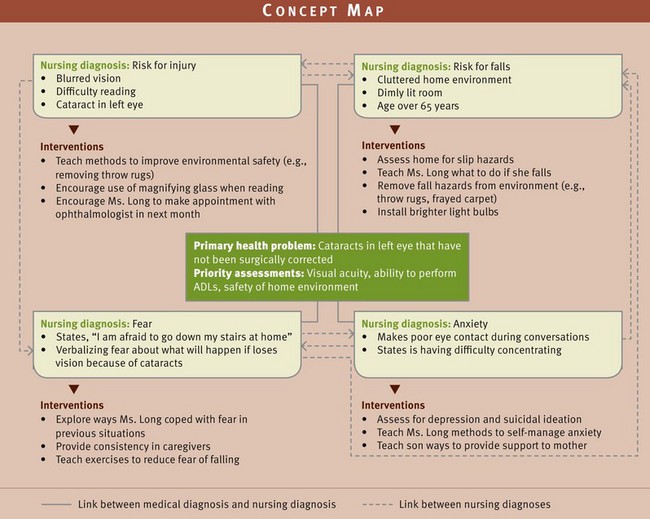

Some patients have health care problems for which sensory alteration is the etiology, such as with the diagnosis of risk for injury. You select nursing diagnoses by recognizing the way that sensory alterations affect a patient’s ability to function (e.g., self-care deficit). In addition, most patients present themselves to health care professionals with multiple diagnoses (Fig. 49-3). In the example of the concept map, a patient with a cataract has the nursing diagnoses of risk for injury, anxiety, fear, and risk for falls. The sensory alteration caused by the cataract is an etiology for both risk for injury and risk for falls. Furthermore, fear occurs as a response to a perceived risk of falling. You need to recognize patterns of data that reveal health problems created by the patient’s sensory alteration. Examples of nursing diagnoses that apply to patients with sensory alterations include the following:

Planning

During planning synthesize information from multiple resources (Fig. 49-4). Reflect on knowledge gained from the assessment and knowledge of how sensory deficits affect normal functioning. In this way you are able to recognize the extent of the patient’s deficit and know the type of interventions most likely to be helpful. Also consider the role that health professionals play in planning care and the available community resources that will be useful. Previous experience in caring for patients with sensory alterations is invaluable.

When applying critical thinking to planning care, professional standards are particularly useful. These standards recommend evidence-based interventions for the patient’s condition. For example, patients who have visual deficits and are hospitalized are often placed on a fall-prevention protocol that incorporates research-based precautions to ensure patient safety.

Goals and Outcomes

During planning develop an individualized plan of care for each nursing diagnosis (see the Nursing Care Plan). Partner with the patient to develop a realistic plan that incorporates what you know about his or her sensory problems and the extent to which he or she can maintain or improve sensory function. Goals and outcomes need to be realistic and measurable. An example of a goal of care for a patient with an actual or potential sensory alteration is “The patient will achieve improvement in hearing acuity within 2 weeks.” Associated outcomes for this goal include the following:

Setting Priorities

You consider the type and extent of sensory alteration affecting a patient when determining priorities of care. For example, a patient who enters the emergency department after experiencing eye trauma has priorities of reducing anxiety and preventing further injury to the eye. In contrast, a patient who is being discharged from an outpatient surgery department following cataract removal has the priority of learning about self-care restrictions. Safety is always a top priority. The patient also helps prioritize aspects of care. For example, a patient wishes to learn ways to communicate more effectively or participate in favorite hobbies given his or her limitation.

Some sensory alterations are short term (e.g., a patient experiencing sensory overload in an ICU). Thus appropriate interventions are likely to be temporary (e.g., frequent reorientation or introduction of pleasant stimuli such as a back rub). Some sensory alterations such as permanent visual loss require long-term goals of care for patients to adapt. Patients who have sensory alterations at the time of entering a health care setting are usually most informed about how to adapt interventions to their lifestyles. For example, allow patients who are blind to control whatever parts of their care they can. Sometimes it becomes necessary for the patient to make major changes in self-care activities, communication, and socialization to ensure safe and effective nursing care.

Teamwork and Collaboration

When developing a plan of care, consider all resources available to patients. The family plays a key role in providing meaningful stimulation and learning ways to help the patient adjust to any limitations. Engaging the family or designated surrogate is a fundamental skill of patient-centered care (Cronenwett et al., 2007). You also frequently refer patients to other health care professionals. For example, early referrals to occupational or speech therapists speeds a patient’s recovery. If a patient has a major loss of sensory function and is also unable to manage medical needs such as medication self-administration or dressing changes, referral to home care is an option. Valuing intraprofessional and interprofessional collaboration is an essential nurse competency and plays a role in quality patient care (Cronenwett et al., 2007). Numerous community-based resources (e.g., local chapter of the Society for the Blind and Visually Impaired and the Area Agency on Aging) are also available. Try to arrange a volunteer to visit a patient or have printed materials made available that describe ways to cope with sensory problems.

Implementation

Nursing interventions involve the patient and family so the patient is able to maintain a safe, pleasant, and stimulating sensory environment. The most effective interventions enable a patient with sensory alterations to function safely with existing deficits and continue a normal lifestyle. Patients can learn to adjust to sensory impairments at any age with the proper support and resources. Use measures to maintain a patient’s sensory function at the highest level possible.

Health Promotion

Good sensory function begins with prevention. When a patient seeks health care, provide education about interventions that reduce the risk for sensory losses. Also recommend relevant visual and hearing guidelines.

Screening: An estimated 80 million people have potentially blinding eye diseases (National Eye Institute, 2010c). Preventable blindness is a worldwide health issue that begins with children and requires appropriate screening. Four recommended interventions are (1) screening for rubella, syphilis, chlamydia, and gonorrhea in women who are considering pregnancy; (2) advocating adequate prenatal care to prevent premature birth (with the danger of exposure of the infant to excessive oxygen); (3) administering eye prophylaxis in the form of erythromycin ointment approximately 1 hour after an infant’s birth; and (4) periodic screening of all children, especially newborns through preschoolers, for congenital blindness and visual impairment caused by refractive errors and strabismus (Hockenberry and Wilson, 2011).

Visual impairments are common during childhood. The most common visual problem is a refractive error such as nearsightedness. The nurse’s role is one of detection, education, and referral. Parents need to know the signs of visual impairment (e.g., failure to react to light and reduced eye contact from the infant). Instruct parents to report these signs to their health care provider immediately. Vision screening of school-age children and adolescents helps detect problems early. The school nurse is usually responsible for vision testing.

In the United States glaucoma is the second leading cause of blindness in the general population and the primary cause of blindness in African Americans. If left undetected and untreated, it leads to permanent visual loss. The American Academy of Ophthalmology (2010) recommends a regular medical eye examination with measurement of intraocular pressure every 2 years for those over 40 years old. Examinations need to occur every 1 to 2 years if there is a family history of glaucoma or if the patient is of African ancestry, has had a serious eye injury in the past, is taking steroid medications, or is over 65 years of age.

Hearing impairment is one of the most common disabilities in the United States. An estimated 37 million people in the United States are deaf or hard of hearing (CDC, 2008). Children at risk include those with a family history of childhood hearing impairment, perinatal infection (rubella, herpes, or cytomegalovirus), low birth weight, chronic ear infection, and Down syndrome. Advise pregnant women of the importance of early prenatal care, avoidance of ototoxic drugs, and testing for syphilis or rubella.

Children with chronic middle ear infections, a common cause of impaired hearing, need to receive periodic auditory testing. Warn parents of the risks and to seek medical care when the child has symptoms of earache or respiratory infection.

Because aging is associated with degenerative changes in the ear, patients need to have hearing screenings at least every decade through age 50 and every 3 years thereafter (American Speech-Language-Hearing Association, 2011). Once a patient reports a hearing loss, regular testing also becomes necessary. In addition, a patient who works or lives in a high–noise level environment requires an annual screening. Occupational health nurses play a key role in the assessment of the auditory system and the initiation of prompt referrals. The early identification and treatment of problems help older adults be more active and healthy.

Preventive Safety: Trauma is a common cause of blindness in children. Penetrating injury from propulsive objects such as firecrackers or slingshots or from penetrating wounds from sticks, scissors, or toy weapons are just a few examples. Parents and children require counseling on ways to avoid eye trauma such as avoiding use of toys with long, pointed projections and instructing children not to walk or run while carrying pointed objects. Instruct patients that they can find safety equipment in most sports shops and large department stores.

Adults are at risk for eye injury while playing sports and working in jobs involving exposure to chemicals or flying objects. The Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA, 2010) has guidelines for workplace safety. Employers are required to have eye wash stations and to have employees wear eye goggles and/or use equipment such as HPDs to reduce the risk of injury. Healthy People 2020 (USDHHS, 2009) identifies goals that include reducing new cases of work-related, noise-induced hearing loss. Occupational health nurses reinforce the use of protective devices. In addition, nurses need to routinely assess patients for noise exposure and participate in providing hearing conservation classes for teachers, students, and patients.

Another means of prevention involves regular immunization of children against diseases capable of causing hearing loss (e.g., rubella, mumps, and measles). Nurses who work in health care providers’ offices, schools, and community clinics instruct patients about the importance of early and timely immunization. In all populations use caution when administering ototoxic drugs.

Use of Assistive Devices: Patients who wear corrective contact lenses, eyeglasses, or hearing aids need to make sure that they are clean, accessible, and functional (see Chapter 39). It is helpful to have a family member or friend who also knows how to care for and clean an assistive aid (Box 49-7). A contact lens wearer must frequently clean lenses (see Chapter 39) and use the appropriate solutions for cleaning and disinfection. Contact lens wearers are subject to serious eye infections caused by infrequent lens disinfection, contamination of lens storage cases or contact lens solutions, and use of homemade saline. Swimming while wearing lenses also creates a serious risk of infection. Reinforce proper lens care in any health maintenance discussion.

Older adults are often reluctant to use hearing aids. Reasons cited most often include cost, appearance, insufficient knowledge about hearing aids, amplification of competing noise, and unrealistic expectations. Neuromuscular changes in the older adult such as stiff fingers, enlarged joints, and decreased sensory perception also make the handling and care of a hearing aid difficult. Fortunately today there are a wide variety of aids that not only enhance a person’s hearing but also are cosmetically acceptable and useful for persons with manual dexterity issues. Chapter 39 summarizes the types of hearing aids available and tips for proper care and use.

Acknowledging a need to improve hearing is a person’s first step. Give patients useful information on the benefits of hearing aid use. A person who understands the need for good hearing will likely be influenced to wear hearing aids. It is also important to have a significant other available to assist with hearing aid adjustment. Federal regulations require medical clearance from a health care provider before an individual can purchase a hearing aid. Hearing aids are contraindicated for the following conditions: visible congenital or traumatic deformity of the ear, active drainage in the last 90 days, sudden or progressive hearing loss within the last 90 days, acute or chronic dizziness, unilateral sudden hearing loss within the last 90 days, visible cerumen accumulation or a foreign body in the ear canal, pain or discomfort in the ear, or an audiometric air-bone gap of 15 decibels or greater. A nursing assessment detects the first seven of these conditions during a physical examination. Refer the patient to an otolaryngologist for further counseling (Ebersole et al., 2008).

Promoting Meaningful Stimulation: Life becomes more enriching and satisfying when meaningful and pleasant stimuli exist within the environment. You can help patients adjust to their environment in many ways so it becomes more stimulating. You do this best by considering the normal physiological changes that accompany sensory deficits.

Vision: As a result of the normal changes of aging, the pupil’s ability to adjust to light diminishes; thus older adults are often very sensitive to glare. Suggest the use of yellow or amber lenses and shades or blinds on windows to minimize glare. Wearing sunglasses outside obviously reduces the glare of direct sunlight. Other interventions to enhance vision for patients with visual impairment include warm incandescent lighting and colors with sharp contrast and intensity.

The ability to read is important. Therefore allow patients to use their glasses whenever possible (e.g., during procedures and instruction). Some patients with reduced visual acuity need more than corrective lenses. A pocket magnifier helps a patient read most printed material. Telescopic lens eyeglasses are smaller, easier to focus, and have a greater range. Books and other publications are also available in larger print. If a patient has a legal or other important document that he or she wishes to read, standard copying machines have enlarging capabilities. Closed-circuit television magnifying units enlarge written characters up to 45 times (Ebersole et al., 2008).

With aging a person experiences a change in color perception. Perception of the colors blue, violet, and green usually declines. Brighter colors such as red, orange, and yellow are easier to see. Offer suggestions of ways to decorate a room and paint hallways or stairwells so the patient is able to differentiate surfaces and objects in a room.

Hearing: To maximize residual hearing function, work closely with the patient to suggest ways to modify the environment. Patients can amplify the sound of telephones and televisions. An innovative way to enrich the lives of the hearing impaired is recorded music. Some patients with severe hearing loss are able to hear music recorded in the low-frequency sound cycles.

One way to help an individual with a hearing loss is to ensure that the problem is not impacted cerumen. With aging, cerumen thickens and builds up in the ear canal. Excessive cerumen occluding the ear canal causes conductive hearing loss. Instilling a softening agent such as 0.5 to 1 mL of warm mineral oil into the ear canal followed by irrigation of a solution of 3% hydrogen peroxide in a quart of warmed water removes cerumen and significantly improves the patient’s hearing ability (Ebersole et al., 2008).

Taste and Smell: Promote the sense of taste by using measures to enhance remaining taste perception. Good oral hygiene keeps the taste buds well hydrated. Well seasoned, differently textured food eaten separately heightens taste perception. Flavored vinegar or lemon juice adds tartness to food. Always ask the patient which foods are most appealing. Improving taste perception improves food intake and appetite as well.

Stimulation of the sense of smell with aromas such as brewed coffee, cooked garlic, and baked bread heightens taste sensation. The patient needs to avoid blending or mixing foods because these actions make it difficult to identify tastes. Older persons need to chew food thoroughly to allow more food to contact remaining taste buds.

Improve smell by strengthening pleasant olfactory stimulation. Make a patient’s environment more pleasant with smells such as cologne, mild room deodorizers, fragrant flowers, and sachets. Consult with patients to find out which scents they can tolerate. The removal of unpleasant odors (e.g., bedpans or soiled dressings) also improves the quality of a patient’s environment.

Touch: Patients with reduced tactile sensation usually have the impairment over a limited portion of their bodies. Providing touch therapy stimulates existing function. If a patient is willing to be touched, hair brushing and combing, a back rub, and touching the arms or shoulders are ways of increasing tactile contact. When sensation is reduced, a firm pressure is often necessary for a patient to feel a nurse’s hand. Turning and repositioning also improves the quality of tactile sensation.

If a patient is overly sensitive to tactile stimuli (hyperesthesia), minimize irritating stimuli. Keeping bed linens loose to minimize direct contact with a patient and protecting the skin from exposure to irritants are helpful measures. Physical therapists can recommend special wrist splints for patients to wear to dorsiflex their wrists and relieve nerve pressure when they have numbness and tingling or pain in the hands, as with carpal tunnel syndrome. For patients who use computers, special keyboards and wrist pads are available to decrease the pressure on the median nerve, aid in pain relief, and promote healing.

Establishing Safe Environments: When sensory function becomes impaired, individuals become less secure within their home and workplace. Security is necessary for a person to feel independent. Make recommendations for improving safety within a patient’s living environment without restricting independence. During a home visit or while completing an examination in the clinic, offer several useful suggestions for home safety. The nature of the actual or potential sensory loss determines the safety precautions taken.

Adaptations for Visual Loss: When a patient experiences a decrease in visual acuity, peripheral vision, adaptation to the dark, or depth perception, safety is a concern. With reduced peripheral vision a patient cannot see panoramically because the outer visual field is less discrete. With reduced depth perception a person is unable to judge how far away objects are located. This is a special danger when he or she walks down stairs or over uneven surfaces.

Driving is a particular safety hazard for older adults with visual alterations. Reduced peripheral vision prevents a driver from seeing a car in an adjacent lane. A sensitivity to glare creates a problem for driving at night with headlights. Vision is a primary consideration for safety, but there are other factors as well. In the case of older adults, decreased reaction time, reduced hearing, and decreased strength in the legs and arms further compromise driving skills. Some safety tips to share with those who continue to drive include the following: drive in familiar areas, do not drive during rush hour, avoid interstate highways for local drives, drive defensively, use rear-view and side-view mirrors when changing lanes, avoid driving at dusk or night, go slow but not too slow, keep the car in good working condition, and carry a preprogrammed cellular phone.

The presence of visual alterations makes it difficult for a person to conduct normal activities of living within the home. Because of reduced depth perception, patients can trip on throw rugs, runners, or the edge of stairs. Teach patients and family members to keep all flooring in good repair and advise them to use low-pile carpeting. Thresholds between rooms need to be level with the floor. Recommend the removal of clutter to ensure clear pathways for walking and arrangement of furniture so a patient can move about easily without fear of tripping or running into objects. Suggest that stairwells have a securely fastened banister or handrail extending the full length of the stairs.

Front and back entrances to the home, work areas, and stairwells need to be properly lighted. Light fixtures need high-wattage bulbs with wider illumination. A light switch should be located at the top and bottom of stairwells. It is also important to be sure that lighting on the stairs does not cast shadows. Have a family member paint the edge of steps so the patient can clearly see each step, especially the first and last. When possible have patients replace steps inside and outside the home with ramps.

An added consideration is to administer eye medications safely (see Chapter 31). Patients need to closely adhere to regular medication schedules for conditions such as glaucoma. Labels on medication containers need to be in large print. Make sure that a friend or spouse is familiar with dosage schedules in case a patient is unable to self-administer a medication. Patients with visual impairments often have difficulty manipulating eyedroppers.

Adaptations for Reduced Hearing: Patients hear important environmental sounds (e.g., doorbells and alarm clocks) best if they are amplified or changed to a lower-pitched, buzzerlike sound. Lamps designed to turn on in response to sounds such as doorbells, burglar alarms, smoke detectors, and babies crying are also available. Family members and anyone who calls the patient regularly need to learn to let the phone ring for a longer period. Amplified receivers for telephones and telephone communications devices (TCDs) are available that use a computer and printer to transfer words over the telephone for the hearing impaired. Both sender and receiver need to have the special device to complete a call.

Adaptations for Reduced Olfaction: The patient with a reduced sensitivity to odors is often unable to smell leaking gas, a smoldering cigarette, fire, or spoiled food. Advise patients to use smoke detectors and take precautions such as checking ashtrays or placing cigarette butts in water. In addition, teach patients to check food package dates, inspect the appearance of food, and keep leftovers in labeled containers with the preparation date. Pilot gas flames need to be checked visually.

Adaptations for Reduced Tactile Sensation: When patients have reduced sensation in their extremities, they are at risk for injury from exposure to temperature extremes. Always caution these patients on the use of water bottles or heating pads (see Chapter 48). The temperature setting on the home water heater should be no higher than 48.8° C (120° F). If a patient also has a visual impairment, it is important to be sure that water faucets are clearly marked “hot” and “cold,” or use color codes (i.e., red for hot and blue for cold).

Communication: A sensory deficit often causes a person to feel isolated because of an inability to communicate with others. It is important for individuals to be able to interact with people around them. The nature of the sensory loss influences the methods and styles of communication that nurses use during interactions with patients (Box 49-8). You also teach communication methods to family members and significant others. For patients with visual deficits or blindness, speak normally, not from a distance, and be sure to have sufficient lighting.

The patient with a hearing impairment is often able to speak normally. To more clearly hear what a person communicates, family and friends need to learn to move away from background noise, rephrase rather than repeat sentences, be positive, and have patience. In a group setting it is better to form a semicircle in front of the patient so he or she can see who is speaking next; this helps foster group involvement. On the other hand, some patients who are deaf have serious speech alterations. Some use sign language or lip reading, wear special hearing aids, write with a pad and pencil, or learn to use a computer for communication. Special communication boards that contain common terms (e.g., pain, bathroom, dizzy, or walk) help patients express their needs.

Patient education is one aspect of communication. Teaching booklets are available in large print for patients with visual loss. The patient who is blind often requires more frequent and detailed verbal descriptions of information. This is particularly true if there are no instructional booklets written in Braille. Patients with visual impairments can also learn by listening to audiotapes or the sound portion of a televised teaching session. Patients with hearing impairments often benefit from written instructional materials and visual teaching aids (e.g., posters and graphs). Demonstrations by the nurse are very useful. Hospitals are required to make professional interpreters available to read sign language for patients who are deaf.

Acute Care

When patients enter acute care settings for therapeutic management of sensory deficits or as a result of traumatic injury, use different approaches to maximize sensory function existing at the time. Safety is an obvious priority until the patient’s sensory status is either stabilized or improved. For example, patients with sensory deficits have a high risk for falls in the acute care environment. It is very important to know the extent of any existing sensory impairment before the acute episode of illness so you are able to reinforce what the patient already knows about self-care or plan for more instruction before and following discharge.

Orientation to the Environment: The patient with recent sensory impairment requires a complete orientation to the immediate environment. Provide reorientation to the institutional environment by ensuring that name tags on uniforms are visible, addressing the patient by name, explaining where the patient is (especially if patients are transported to different areas for treatment), and using conversational cues to time or location. Reduce the tendency for patients to become confused by offering short and simple, repeated explanations and reassurance. Encourage family members and visitors to help orient patients to the hospital surroundings.

Patients with serious visual impairment need to feel comfortable in knowing the boundaries of the immediate environment. Normally we see physical boundaries within a room. Patients who are blind or severely visually impaired often touch the boundaries or objects to gain a sense of their surroundings. The patient needs to walk through a room and feel the walls to establish a sense of direction. Help patients by explaining objects within the hospital room, such as furniture or equipment. It takes time for a patient to absorb room arrangement. He or she often needs to reorient again as you explain the location of key items (e.g., call light, telephone, and chair). Remember to approach the patient from the front to avoid startling him or her.

It is important to keep all objects in the same position and place. After an object is moved even a short distance, it no longer exists for a person who is blind. Simply moving a chair creates a safety hazard. Ask the patient if any item needs to be rearranged to make ambulation easier. Clear traffic patterns to the bathroom. Give the patient extra time to perform tasks. He or she needs a detailed description of how to perform an activity and moves slowly to remain safe.

Patients confined to bed are at risk for sensory deprivation. Normally movement gives an awareness of self through vestibular and tactile stimulation. Movement patterns influence sensory perception. The limited movement of bed rest changes how a person interprets the environment; surroundings seem different, and objects seem to assume shapes different from normal. A person who is on bed rest requires routine stimulation through range-of-motion exercises, positioning, and participation in self-care activities (as appropriate). Comfort measures such as washing the face and hands and providing back rubs improve the quality of stimulation and lessen the chance of sensory deprivation. Planning time to talk with patients is also essential. Explain unfamiliar environmental noises and sensations. A calm, unhurried approach gives you quality time to help reorient and familiarize the patient with care activities. The patient who is well enough to read will benefit from a variety of reading material.

Communication: The most common language disorder following a stroke is aphasia. Depending on the type of aphasia, the inability to communicate is often frustrating and frightening (see Box 49-8). Initially you need to establish very basic communication and recognize that it does not indicate intellectual impairment or degeneration of personality. Explain situations and treatments that are pertinent to the patient because he or she is able to understand the speaker’s words. Because a stroke often causes partial or complete paralysis of one side of a patient’s body, the patient needs special assistive devices. A variety of communication boards for different levels of disability are available. Sensitive pressure switches activated by the touch of an ear, nose, or chin control electronic communication boards (Ebersole et al., 2008). Make referrals to speech therapists to develop appropriate rehabilitation plans.

In acute care hospitals or long-term care facilities, nurses often care for patients with artificial airways (such as an endotracheal tube) (see Chapter 40). The placement of an endotracheal tube prevents a patient from speaking. In this case the nurse uses special communication methods to facilitate his or her ability to express needs. The patient is sometimes completely alert and able to hear and see the nurse normally. Giving patients time to convey any needs or requests is very important. Use creative communication techniques (e.g., a communication board or laptop computer) to foster and strengthen a patient’s interactions with health care personnel, family, and friends.

Controlling Sensory Stimuli: Patients need time for rest and freedom from stress caused by frequent monitoring and repeated tests. Reduce sensory overload by organizing the patient’s plan of care. Combining activities such as dressing changes, bathing, and vital sign measurement in one visit prevents him or her from becoming overly fatigued. The patient also needs scheduled time for rest and quiet. Planning for rest periods often requires cooperation from family, visitors, and health care colleagues. Coordination with laboratory and radiology departments minimizes the number of interruptions for procedures. A creative solution to decrease excessive environmental stimuli that prevents restful, healing sleep is to institute “quiet time” in ICUs. Quiet time means dimming the lights throughout the unit, closing the shades, and shutting the doors. Data collected from one hospital that implemented “quiet time” demonstrated significantly lower noise levels and light levels during day-shift quiet time. Patients were also more likely to sleep during daytime quiet hours (Dennis et al., 2010).

When patients experience sensory overload or deprivation, their behavior is often difficult for family or friends to accept. Encourage the family not to argue with or contradict the patient but to calmly explain location, identity, and time of day. Engaging the patient in a normal discussion about familiar topics assists in reorientation. Anticipating patient needs such as voiding helps reduce uncomfortable stimuli.

Try to control extraneous noise in and around a patient’s room. It is often necessary to ask a roommate to lower the volume on a television or to move the patient to a quieter room. Keep equipment noise to a minimum. Turn off bedside equipment not in use such as suction and oxygen equipment. Avoid making abrupt loud noises such as dropping objects or causing the over-bed table to suddenly adjust to the lowest level. Nursing staff also need to control laughter or conversation at the nurses’ station. Allow patients to close their room doors.

When the patient leaves an acute care setting for the home environment, communicate with colleagues in the home care setting about the patient’s existing sensory deficits and the interventions that helped the patient adapt to sensory problems. You achieve continuity of care when the patient only has to make minimal changes in the home setting.

Safety Measures: The patient with recent visual impairment often requires help with walking. The presence of an eye patch, frequently instilled eyedrops, and the swelling of eyelid structures following surgery are just a few factors that cause a patient to need more assistance than usual. A sighted guide gives confidence to patients with visual impairments and ensures safe mobility. Ebersole et al. (2008) list three suggestions for a sighted guide:

1. Ask the patient if he or she wants a “sighted guide.” If assistance is accepted, offer an elbow or arm. Instruct the patient to grasp your arm just above the elbow (Fig. 49-5). If necessary, physically help the person by guiding his or her hand to your arm or elbow.

FIG. 49-5 Nurse assists in ambulation of patient with visual impairment. (From Sorrentino SA, Remmert LN: Mosby’s textbook for nursing assistants, ed 8, St Louis, 2012, Mosby.)

2. Go one-half step ahead and slightly to the side of the person. The shoulder of the person needs to be directly behind your shoulder. If the person is frail, place the hand on your forearm.

3. Relax and walk at a comfortable pace. Warn the patient when you approach doorways or narrow spaces.

While walking with the patient, describe the surroundings and ensure that obstacles have been removed. Never leave a patient with a visual impairment standing alone in an unfamiliar area. It is important to teach family members techniques for assisting with ambulation. Nursing staff also need to ensure that the patient knows where the call light is before leaving the patient alone. Place necessary objects in front of the patient to prevent falls caused by reaching over the bedside. Appropriate use of side rails is also an option (see Chapter 38).

Nurses often rely on patients in health care settings to report unusual sounds such as a suction apparatus running improperly or an IV pump alarm. However, the patient with a hearing loss does not always hear these sounds and thus requires more frequent visits by nurses. The patient also benefits from learning to use vision to discover sources of danger. It is wise to note on the intercom system at the nurse’s station and in the medical record if the patient is deaf and/or blind. A patient lacking the ability to speak cannot call out for assistance. Patients need to have message boards and call lights close at hand.

Patients with reduced tactile sensation risk injury when their conditions confine them to bed because they are unable to sense pressure on bony prominences or the need to change position. These patients rely on nurses for timely repositioning, moving tubes or devices on which the patient is lying, and turning to avoid skin breakdown. When a patient is less able to sense temperature variations, use extra caution in applying heat and cold therapies (see Chapter 48) and preparing bathwater. Check the condition of the patient’s skin frequently.

Restorative and Continuing Care

Maintaining Healthy Lifestyles: After a patient has experienced a sensory loss, it becomes important to understand the implications of the loss and make adjustments needed to continue a normal lifestyle. Sensory impairments need not prevent a person from leading an active, rewarding life. Many of the interventions applicable to health promotion such as adapting the home environment are useful after a patient leaves an acute care setting.

Understanding Sensory Loss: Patients who have experienced a recent sensory loss need to understand how to adapt so their living environments are safe and appropriately stimulating. All family members need to understand the way that a patient’s sensory impairment affects normal daily activities. Family and friends are more supportive when they understand sensory deficits and factors that worsen or lessen sensory problems. For example, family and friends need to learn how to communicate with someone who has a hearing loss. Community resources are available to provide information to assist patients with personal management needs. The American Foundation for the Blind, American Red Cross, and National Association for Speech and Hearing offer resource materials and product information.

Socialization: The ability to communicate is gratifying. It tests a person’s intellect, opens opportunities, and allows him or her to exchange the feelings that he or she has about others. When sensory alterations hinder interactions, a person feels ineffective and loses self-esteem. When patients feel socially unaccepted, they perceive sensory losses as seriously impairing their quality of life.

Interacting with others becomes a burden for many patients with sensory alterations. They lose the motivation to engage in social situations, resulting in a deep sense of loneliness. Use therapies to reduce loneliness, particularly in older adults (Box 49-9). These principles support the Healthy People 2020 objective to increase the proportion of adults with disabilities reporting sufficient emotional support. In addition, family members need to learn to focus on a person’s ability to interact rather than on his or her disability. For example, do not assume that a person who is hard of hearing does not wish to speak. A person who is blind can still enjoy a walk through a park with a companion describing the sights around them.

Promoting Self-Care: The ability to perform self-care is essential for self-esteem. Frequently family members and nurses believe that persons with sensory impairments require assistance, when in fact they are able to help themselves. To help with meals, arrange food on the plate and condiments, salad, or drinks according to numbers on the face of a clock (Fig. 49-6). It is easy for the patient to become oriented to the items after the nurse or family member explains the location of each item.

Help patients reach toilet facilities safely. Safety bars need to be installed near the toilet. It is often helpful to have the bar a different color than the wall for easier visibility. Never place towels on a safety bar because they interfere with a person’s grasp. Toilet paper needs to be within easy reach. Sharply contrasting colors within the room helps the partially sighted and promotes functional independence. General principles for promoting self-care in older adults also include using warm incandescent lighting and controlling glare by using shades and blinds (Ebersole et al., 2008).

If the sense of touch is diminished, the patient can dress more easily with zippers or Velcro strips, pullover sweaters or blouses, and elasticized waists. If a patient has partial paralysis and reduced sensation, the patient dresses the affected side first. Encourage family members responsible for selecting clothing for patients with visual impairments to follow the patient’s preferences. Any sensory impairment has a significant influence on body image, and it is important for the patient to feel well groomed and attractive. Some patients need assistance with basic grooming such as brushing, combing, and shampooing hair. Others need assistance with medication administration, clothing identification, and learning to manage routine procedures such as blood pressure and glucose monitoring. An assortment of low-vision devices is now available. It is important for you to make appropriate referrals to allow the patient to maintain a maximum degree of independence.

Patients with proprioceptive problems often lose their balance easily. Make sure that bathrooms have nonskid surfaces in the tub and shower. Install grab bars either vertically or horizontally in tubs and showers, depending on how the patient is able to grasp or hold onto the bar. Instruct family members to supervise ambulation and sitting, make frequent checks to prevent falls, and caution the patient against leaning forward.

Evaluation

It is important to evaluate whether care measures maintain or improve a patient’s ability to interact and function within the environment. The patient is the source for evaluating outcomes. He or she is the only one who knows if sensory abilities are improved and which specific interventions or therapies are most successful in facilitating a change in his or her performance (Fig. 49-7). Collaborate with family members to determine if the patient’s ability to function within the home has improved.

If you have successfully developed a good relationship with a patient, notice that subtle behaviors often indicate the level of his or her satisfaction. You may notice that the patient responds appropriately, such as by smiling. However, it is important for you to ask the patient if his or her sensory needs have been met. For example, ask, “Have we done all we can do to help improve your ability to hear?” If the patient’s expectations have not been met, ask the patient, “How can the health care team better meet your needs?” Working closely with the patient and family enables you to redefine expectations that can be realistically met within the limits of the patient’s condition and therapies. You have been effective when the patient’s goals and expectations have been met.

Patient Outcomes

To evaluate the effectiveness of specific nursing interventions, use critical thinking and make comparisons with baseline sensory assessment data to evaluate if sensory alterations have changed. It is your responsibility to determine if expected outcomes have been met. For example, use evaluative data to determine whether care measures improve or at least maintain a patient’s ability to interact and function within the environment. The nature of a patient’s sensory alterations influences how you evaluate the outcome of care. When caring for a patient with a hearing deficit, use proper communication techniques and then evaluate whether he or she has gained the ability to hear or interact more effectively. When expected outcomes have not been achieved, there is a need to change interventions or alter the patient’s environment. If outcomes are not met, it is important to ask questions such as “How are you feeling emotionally?” “Do you feel that you are at risk for injury?”

If you have directed nursing care at improving or maintaining sensory acuity, evaluate the integrity of the sensory organs and the patient’s ability to perceive stimuli. Evaluate interventions designed to relieve problems associated with sensory alterations on the basis of the patient’s ability to function normally without injury. When you directly or indirectly (through education) alter a patient’s environment, evaluate by observing whether the patient makes environmental changes. When designing patient teaching to improve sensory function, it is important to determine whether the patient is following recommended therapies and meeting mutually set goals. Asking the patient to explain or demonstrate self-care skills is an effective evaluative measure. It is often necessary to reinforce previous instruction if learning has not taken place. If outcomes are not met, these are examples of questions to ask:

• “How often do you wear your hearing aids/corrective lenses?”

• “Are you able to participate in a small group discussion?”

The results of your evaluation will determine whether to continue the existing plan of care, make modifications, or end the use of select interventions.

Key Points

• Sensory reception involves the stimulation of sensory nerve fibers and the transmission of impulses to higher centers within the brain.