Medical Nutrition Therapy for HIV and AIDS

Acquired immune deficiency syndrome (AIDS) is caused by the human immunodeficiency virus (HIV). HIV affects the body’s ability to fight off infection and disease, which can ultimately lead to death. Medications used to treat HIV have enhanced the quality of life and increased life expectancy of HIV-infected individuals. These antiretroviral therapy (ART) medications slow the replication of the virus but do not eliminate HIV infection. With increased access to ART, people are living longer with HIV. Unfortunately, health issues such as cardiovascular disease and insulin resistance are increasingly prevalent in this population.

Nutritional status plays an important role in maintaining a healthy immune system and delaying the progression of HIV to AIDS. To develop appropriate nutrition recommendations, the nutrition professional should be familiar with the pathophysiology of HIV infection, the medication and nutrient interactions, and the barriers to adequate nutrition. Mental health status and illicit drug use should be considered since it may affect nutrition intake.

Epidemiology and Trends

The first cases of AIDS were described in 1981. Soon after, HIV was isolated and identified as the core agent leading to AIDS. Since then, the number of people with HIV has gradually increased, leading to a global pandemic affecting socioeconomic development worldwide. The continuing rise in the population of people living with HIV is reflective of new HIV infections and the widespread use of ART, which has delayed the progression of HIV infection to death. At the end of 2008 an estimated 33.4 million people were living with HIV or AIDS. There were 2.7 million new infections reported, an average of 7400 infections daily, and 2 million HIV-related deaths (Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS [UNAIDS] and the World Health Organization [WHO], 2009).

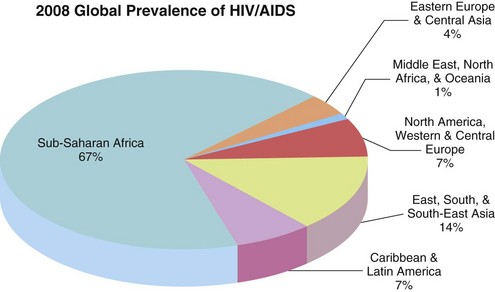

Despite increased prevention efforts and availability of ART, geographic variations in HIV infection is evident. The majority of infections continue to occur in the developing world (Figure 38-1) where more than 97% occur in low- and middle-income countries (UNAIDS and WHO, 2009). Sub-Saharan Africa remains the region most heavily affected by HIV, accounting for two thirds of current HIV infections and 72% of HIV-related deaths (UNAIDS and WHO, 2009). However, increases in new infections are being seen in higher-income countries in eastern Europe such as Ukraine and the Russian Federation. Within sub-Saharan Africa, heterosexual transmission is the most prevalent mode of HIV transmission (UNAIDS and WHO, 2009). In other regions, populations affected by HIV include injection drug users, men who have sex with men, sex workers, and clients of sex workers.

FIGURE 38-1 Global prevalence of HIV and AIDS. (UNAIDS and WHO: 2009 AIDS epidemic update. Accessed 12 July 2010 from http://data.unaids.org/pub/Report/2009/JC1700_Epi_Update_2009_en.pdf. From UNAIDS/ONUSIDA 2009.)

The United States

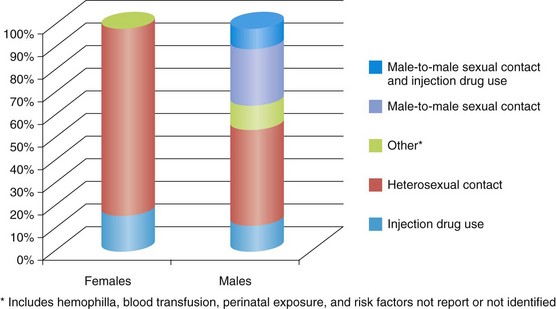

Within the United States, more than 1.2 million people are living with HIV or AIDS and 21% may be unaware of their HIV status (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention [CDC], 2006, UNAIDS, 2008). Although more people are living with a diagnosis of HIV or AIDS, incidence has remained relatively stable since the 1990s. In 2008 men accounted for 75% of all diagnoses of HIV infection. The rate of new infections in men has been trending up since 2005, whereas the rate among women has remained stable (CDC, 2010). The largest percentage of persons living with HIV infection is among those aged 40-44; this same group accounts for the highest rate of new HIV infections. Ethnic populations disproportionately affected by HIV include blacks and Latinos, who accounted for 52% and 25% of HIV diagnoses, respectively, in 2008 (CDC, 2010). The most common route of transmission among men is male-to-male sexual contact and among women is heterosexual contact (Figure 38-2).

FIGURE 38-2 Estimated Percentage of HIV diagnoses by route of transmission in the United States, 2008. (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC): HIV surveillance report, 2008a. Accessed from 12 July 2010 from http://www.cdc.gov/hiv/surveillance/resources/reports/2008report/pdf/2008SurveillanceReport.pdf.)

Pathophysiology and Classification

Primary infection with human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) is the underlying cause of AIDS. HIV invades the genetic core of the CD4+ cells, T-helper lymphocyte cells, which are the principal agents involved in protection against infection. HIV infection causes a progressive depletion of CD4+ cells, which eventually leads to immunodeficiency.

HIV infection progresses through four clinical stages: acute HIV infection, clinical latency, symptomatic HIV infection, and progression of HIV to AIDS. The two main biomarkers used to assess disease progression are HIV ribonucleic acid (RNA) (viral load) and CD4+ T-cell count (CD4 count).

Acute HIV infection is the time from transmission of HIV to the host until the production of detectable antibodies against the virus (seroconversion) occurs. Half of individuals experience physical symptoms such as fever, malaise, myalgia, pharyngitis, or swollen lymph glands at 2-4 weeks following infection, but these generally subside after 1-2 weeks. Because of the nonspecific clinical features and short diagnostic window, acute HIV infection is rarely diagnosed. HIV seroconversion occurs within 3 weeks to 3 months after exposure. If HIV testing is done before seroconversion occurs, a “false negative” may result despite HIV being present. During the acute stage, the virus replicates rapidly and causes a significant decline in CD4+ cell counts. Eventually, the immune response reaches a viral setpoint where viral load stabilizes and CD4+cell counts return closer to normal.

A period of clinical latency or asymptomatic HIV infection, then follows. Further evidence of illness may not be exhibited for as long as 10 years postinfection. The virus is still active and replicating, although at a decreased rate compared with the acute stage, and CD4+ cell counts continue to steadily decline. In 3% to 5% of HIV-infected individuals, long-term nonprogression occurs, in which CD4+ cell counts remain normal and viral loads can be undetectable for years without medical intervention (Department of Health and Human Services [DHHS], 2010). It has been suggested that this unique population has different and fewer receptor sites for the virus to penetrate cell membranes (Wanke et al., 2009).

In the majority of cases, HIV slowly breaks down the immune system, making it incapable of fighting the virus. When CD4+ cell counts fall below 500 cells/ mm3 individuals are more susceptible to developing signs and symptoms such as persistent fevers, chronic diarrhea, unexplained weight loss, and recurrent fungal or bacterial infections, all of which are indicative of symptomatic HIV infection.

As immunodeficiency worsens and CD4 counts fall to even lower levels, the infection becomes symptomatic and progresses to AIDS. The progression of HIV to AIDS increases risk of opportunistic infections (OIs), which generally do not occur in individuals with healthy immune systems. The CDC classifies AIDS cases as positive laboratory confirmation of HIV infection in persons with a CD4+ cell count less than 200 cells/mm3 (or less than 14%) or documentation of an AIDS-defining condition (Box 38-1).

HIV is transmitted via direct contact with infected body fluids like blood, semen, preseminal fluid, vaginal fluid, and breast milk. Cerebrospinal fluid surrounding the brain and spinal cord, synovial fluid surrounding joints, and amniotic fluid surrounding a fetus are other fluids that can transmit HIV. Saliva, tears, and urine do not contain enough HIV for transmission. Sexual transmission is the most common way HIV is transmitted and injection drug use is the second most prevalent method of transmission (see Figure 38-2).

Most people have HIV-1 infection, which, unless specified, is the type discussed in this chapter. HIV-1 mutates readily and has become distributed unevenly throughout the world in different strains, subtypes, and groups. HIV-2, first isolated in western Africa, is less easily transmitted and the time between infection and illness takes longer.

Medical Management

HIV-related morbidity and mortality stem from the HIV virus weakening the immune system as well as the virus’s effects on organs (such as the brain and kidney). If untreated, the HIV virion (virus particle) can replicate at millions of particles per day and rapidly progress through the stages of HIV disease. The introduction of three-drug combination ART in 1996 transformed the treatment of patients infected with HIV and has significantly decreased AIDS-defining conditions and mortality. Most drugs are formulated as individual medications, but increasingly many are available as fixed-dose combinations to simplify treatment regimens, decrease pill burden, and potentially improve patient medication adherence.

CD4 count is used as the major indicator of immune function in people with HIV infection. It is used to determine when to initiate ART and is the strongest predictor of disease progression. CD4 counts are generally monitored every 3 to 4 months. In addition, HIV RNA (viral load) is monitored on a regular basis because it is the primary indicator to gauge the efficacy of ART. Table 38-1 provides the current guidelines on when to initiate ART.

TABLE 38-1

Indications for the Initiation of ART in HIV-infected Individuals

| Clinical Category | CD4 Count | Recommendation |

| Asymptomatic, AIDS | <350 cells/mm3 | Treat |

| Asymptomatic | 350-500 cells/mm3 | Treatment recommended |

| Asymptomatic | >500 cells/mm3 | Some clinicians recommend initiating therapy and some view treatment as optional |

| Symptomatic (AIDS, severe symptoms) | Any value | Treat |

| Pregnancy, HIV-associated nephropathy, HBV coinfection when treatment of HBV is indicated | Any value | Treat |

AIDS, Acquired immune deficiency syndrome; ART, antiretroviral therapy; HBV, hepatitis B virus; HIV, human immunodeficiency virus.

From National Institutes of Health: Guidelines for the use of antiretroviral agents in HIV-1-infected adults and adolescents, 2009. Accessed 23 October 2010 from http://www.aidsinfo.nih.gov/contentfiles/AdultandAdolescentGL.pdf.

The fundamental goals of ART are to achieve and maintain viral suppression, reduce HIV-related morbidity and mortality, improve the quality of life, and restore and preserve immune function. This can generally be achieved within 12-24 weeks if there are no complications with adherence, or resistance to medications (DHHS, 2010). Because the guidelines for HIV management evolve rapidly, it is beneficial to frequently check for updated recommendations.

Classes of Antiretroviral Therapy Drugs

Currently antiretroviral therapy (ART) includes more than 20 antiretroviral agents from six mechanistic classes of drugs:

• Nucleoside and nucleotide reverse transcriptase inhibitors (NRTIs)

• Nonnucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitors (NNRTIs)

The most widely studied combination regimen for treatment of naïve patients consists of two NRTIs plus either one NNRTI or a PI (with or without ritonavir boosting). Recently, a regimen consisting of raltegravir was approved for treatment-naïve patients, making the combination of an INSTI with two NRTIs another option (DHHS, 2010).

Although a reasonable number of different antiretroviral medications are currently available for the treatment of HIV infections, there is a growing need for new drugs that have fewer long-term toxicities and greater potency. However, because eradication of HIV is not yet possible, and the need for treatment is lifelong, adverse effects of medications, including metabolic complications and other toxicities, become increasingly important because they may lead to nonadherence to the prescribed regimen. Nonadherence to ART can lead to drug resistance.

Predictors of Adherence

When initiating ART, patients must be willing and able to commit to lifelong treatment and should understand the benefits and risks of therapy and the importance of adherence. The patient’s understanding about HIV disease and the specific regimen prescribed is critical. A number of factors have been associated with poor adherence, including low levels of literacy, certain age-related challenges (e.g., vision loss, cognitive impairment), psychosocial issues (e.g., depression, homelessness, low social support, stressful life events, dementia, or psychosis), active substance use, stigma, difficulty with taking medication (e.g., trouble swallowing pills, daily schedule issues), complex regimens (e.g., pill burden, dosing frequency, food requirements), adverse drug effects, and treatment fatigue (DHHS, 2010).

When using boosted PIs and efavirenz, their longer half-lives may permit more lapses in adherence since drug levels stay high in the body for many days (Bangsberg, 2006; Raffa, 2008). However, these drugs are more likely to contribute to drug resistance if discontinued due to rapid viral mutation. Continued encouragement is needed to help patients adhere as closely as possible to the prescribed doses for all ART regimens.

Illicit Drug Use

In the United States, injection drug use is the second most common mode of HIV transmission. The most commonly used illicit drugs associated with HIV infection are heroin, cocaine, methamphetamine, and amyl nitrate (poppers). The chaotic lifestyle associated with drug use is associated with poor or inadequate nutrition, food insecurity, and depression. This complicates treatment of HIV if the individual is using drugs, and can potentially lead to poor adherence with ART medications. Special considerations should be taken into account if the liver is damaged from drug use or coinfection with hepatitis, and increased nutrient excretion from diuresis and diarrhea (Hendricks, 2009; Tang, 2010).

Injection drug use is strongly linked with transmission of bloodborne infections such as HIV, hepatitis B virus, and hepatitis C virus (HCV), especially if needles are reused or shared (see Focus On: HIV and Hepatitis C Virus Coinfection). Coinfection of HIV and HCV increases the risk of cirrhosis. Chronic HCV infection also complicates HIV treatment because of ART-associated hepatotoxicity.

Food-Drug Interactions

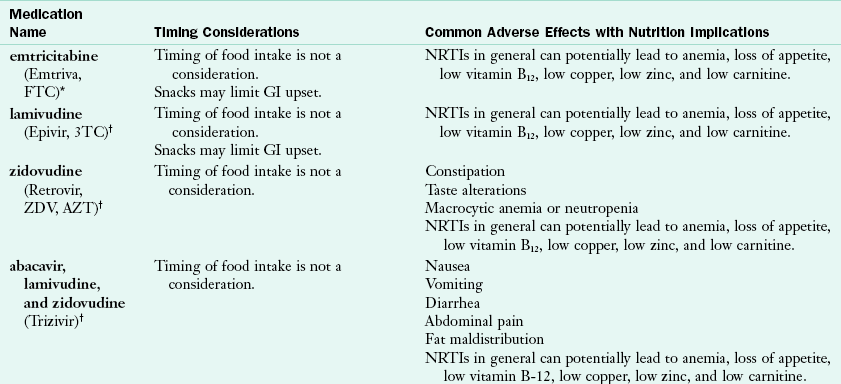

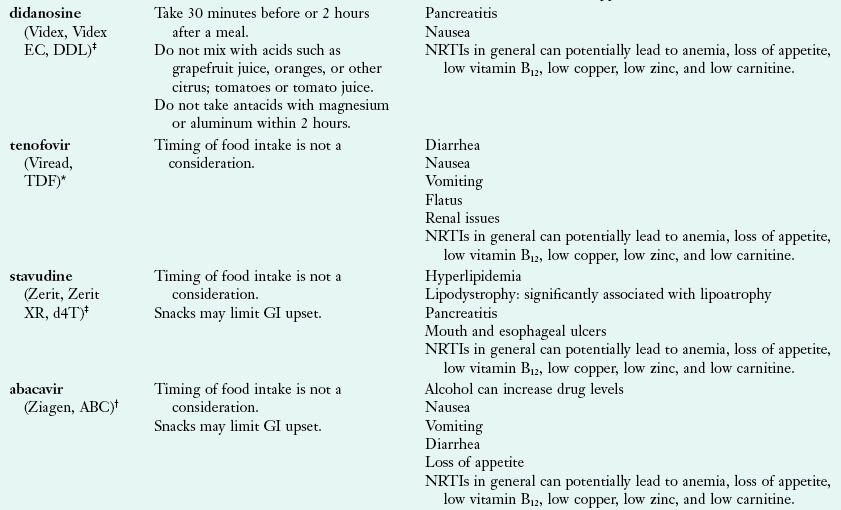

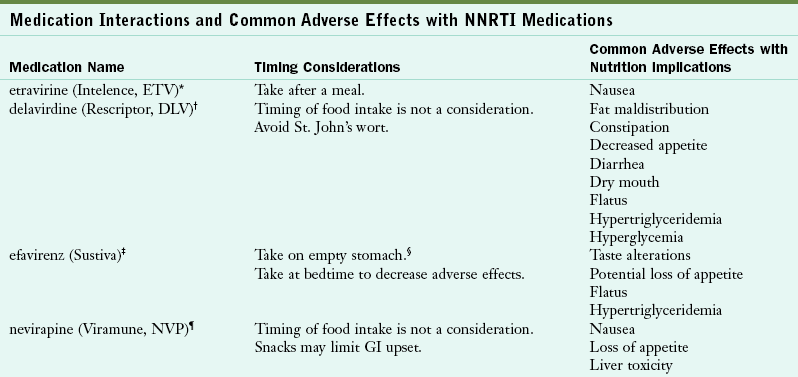

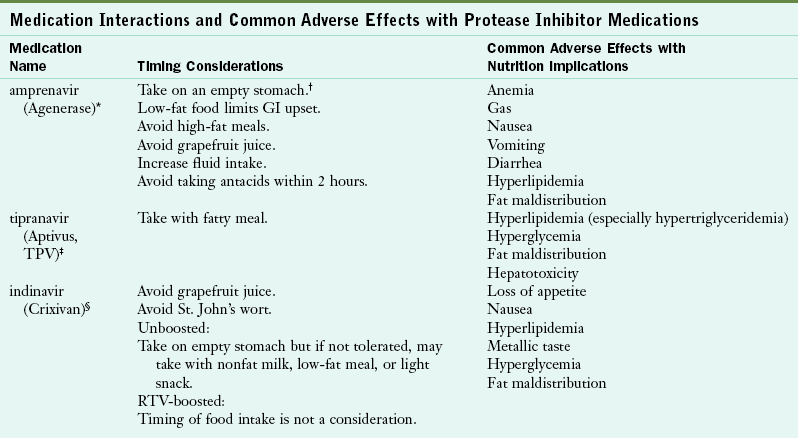

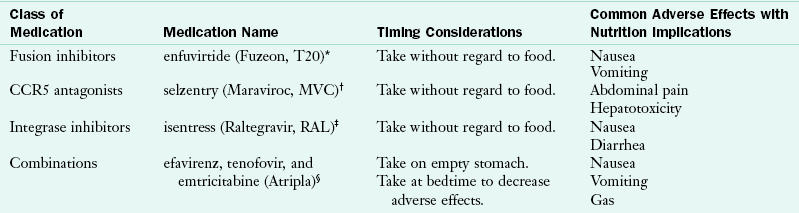

Some ART medications require attention to dietary intake. It is important to ask individuals with HIV to report all medications, including vitamins, supplements, and recreational substances that they consume to fully assess their needs and prevent drug interactions and nutrient deficiencies. Some nutrients can affect how drugs are absorbed or metabolized. Interactions between food and drugs can influence the efficacy of the drug or may cause additional or worsening adverse effects. For example, grapefruit juice and PIs both compete for the cytochrome P450 enzymes; thus individuals taking PIs who also drink grapefruit juice may have either increased or decreased blood levels of the drug. Tables 38-2, 38-3, 38-4, and 38-5 provide potential nutrient interactions with ART medications.

TABLE 38-2

Medication Interactions and Common Adverse Effects with NRTI Medications

Hammer SH et al: 2006 recommendations of the International AIDS Society-USA Panel, JAMA 296:827, 2006.

National Institutes of Health: Guidelines for the use of antiretroviral agents in HIV-1-infected adults and adolescents, 2009. Accessed 23 October 2010 at http://www.aidsinfo.nih.gov/contentfiles/AdultandAdolescentGL.pdf.

GI, Gastrointestinal; NRTI, nucleoside and nucleotide reverse transcriptase inhibitor.

*Made by Gilead (www.gilead.com).

†Made by Glaxosmithkline (www.gsk.com)

‡Made by Bristol-Myers Squibb Company (www.bms.com)

TABLE 38-3

Medication Interactions and Common Adverse Effects with NNRTI Medications

Hammer SH et al: 2006 recommendations of the International AIDS Society-USA Panel, JAMA 296:827, 2006.

National Institutes of Health: Guidelines for the use of antiretroviral agents in HIV-1-infected adults and adolescents, 2009. Accessed 23 October 2010 from http://www.aidsinfo.nih.gov/contentfiles/AdultandAdolescentGL.pdf.

*Made by Tibotec Therapeutics (www.tibotectherapeutics.com).

†Made by Pfizer (www.pfizer.com).

‡Made by Bristol-Myers Squibb Company (www.bms.com).

§Empty stomach refers to 1 hour before meals or 2 hours after meals.

¶Made by Boehringer Ingelheim Pharmaceuticals, Inc (www.Boehringer-ingelheim.com).

TABLE 38-4

Medication Interactions and Common Adverse Effects with Protease Inhibitor Medications

Hammer SH et al: 2006 recommendations of the International AIDS Society—USA Panel, JAMA 296:827, 2006.

National Institutes of Health: Guidelines for the use of antiretroviral agents in HIV-1-infected adults and adolescents, 2009. Accessed 23 October 2010 from http://www.aidsinfo.nih.gov/contentfiles/AdultandAdolescentGL.pdf.

*Made by Galaxosmithkline (www.gsk.com).

†“Empty stomach” refers to 1 hour before meals or 2 hours after meals. Examples of low-fat food are fruit, cereal, nonfat milk, nonfat or low-fat yogurt. Light snack: <300 calories. Light meal: approximately 350 calories. Full meal or fatty meal: 900-1200 calories, 40%-50% of calories from fat for fatty meal.

‡Made by Boehringer Ingelheim Pharmaceuticals, Inc (www.Boehringer-ingelheim.com).

§Made by Merck (www.merck.com).

¶Made by Abbott Laboratories (www.abbott.com).

¶Made by Tibotec Therapeutics (www.tibotectherapeutics.com).

**Made by Bristol-Myers Squibb Company (www.bms.com).

††Made by Roche Laboratories, Inc (www.roche.com).

‡‡Made by Pfizer (www.pfizer.com).

TABLE 38-5

Medication Interactions and Common Adverse Effects with Entry Inhibitor, INSTIs, and Combination Medications

Hammer SH et al: 2006 recommendations of the International AIDS Society—USA Panel, JAMA 296:827, 2006.

National Institutes of Health: Guidelines for the use of antiretroviral agents in HIV-1-infected adults and adolescents, 2009. Accessed 23 October 2010 from http://www.aidsinfo.nih.gov/contentfiles/AdultandAdolescentGL.pdf.

INSTI, Integrase strand transfer inhibitor.

*Made by Roche Laboratories, Inc (www.roche.com).

†Made by Pfizer (www.pfizer.com).

‡Made by Merck (www.merck.com).

§Made by Gilead (www.gilead.com).

Some ART medications can cause diarrhea, fatigue, gastroesophageal reflux, nausea, vomiting, dyslipidemia, and insulin resistance. Timing is also important for ART efficacy, so patients with HIV must take medications on a schedule. Some medications indicate that they must be taken with food or on an empty stomach. Sometimes food needs to be taken within a specific time frame of administering a medication.

Medical Nutrition Therapy

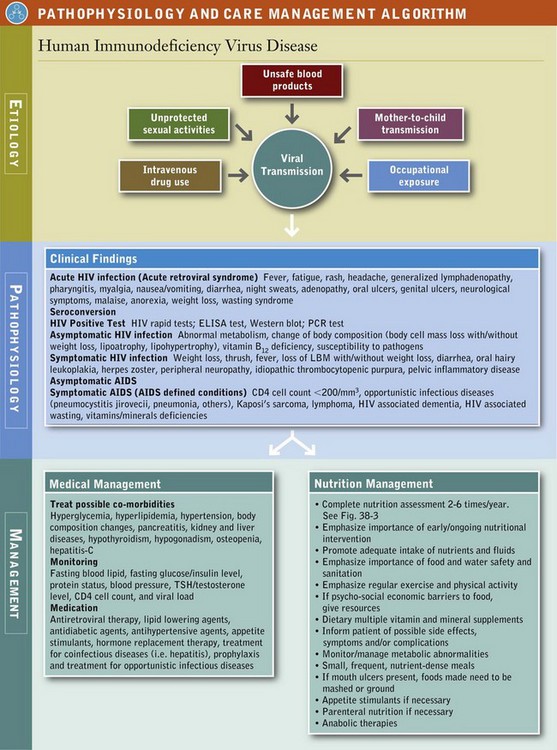

For people living with HIV, adequate and balanced nutrition intake is essential to maintain a healthy immune system and prolong lifespan. It has been documented that both children and adults who are living with HIV have lower fat-free and total fat mass (American Dietetic Association, 2010). Proper nutrition may help maintain lean body mass, reduce the severity of HIV-related symptoms, improve quality of life, and enhance adherence and effectiveness of ART. Therefore medical nutrition therapy (MNT) is integral to successfully manage HIV. See Pathophysiology and Care Management Algorithm: Human Immunodeficiency Virus Disease.

A registered dietitian (RD) can help the patient manage many of the necessary requirements for medications, minimize adverse effects, and address nutritional concerns. Some common nutrition diagnoses in this population include:

• Inadequate oral food and beverage intake

• Altered gastrointestinal (GI) function

• Food- and nutrition-related knowledge deficit

All individuals with HIV infection should have access to a RD or other qualified nutrition professional. Patients should undergo a baseline nutrition assessment once they are diagnosed with HIV. Follow-up should be ongoing and take into consideration the multifactorial complications that may affect patient care. The American Dietetic Association recommends that a RD should provide at least one to two MNT encounters per year for individuals with asymptomatic HIV infection and at least two to six MNT encounters per year for symptomatic but stable HIV infection. Individuals diagnosed with AIDS usually need to be seen more often as they may require nutrition support (see Chapter 14).

Ultimately, MNT should be individualized and frequency of nutrition counseling should be determined by the patient’s needs. The major goals of MNT for persons living with HIV infection are to optimize nutritional status, immunity, and well-being; to maintain a healthy weight and lean body mass; to prevent nutrient deficiencies and reduce the risk of comorbidities; and to maximize the effectiveness of medical and pharmacologic treatments. Thus screening should be performed on all patients medically diagnosed with HIV to identify those at risk for nutritional deficiencies or in need of MNT.

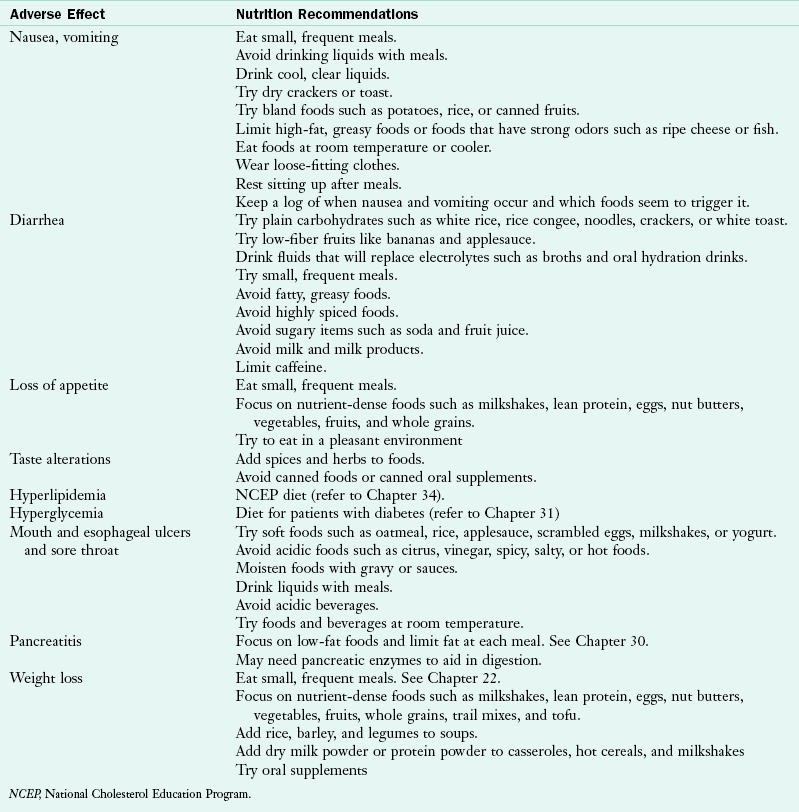

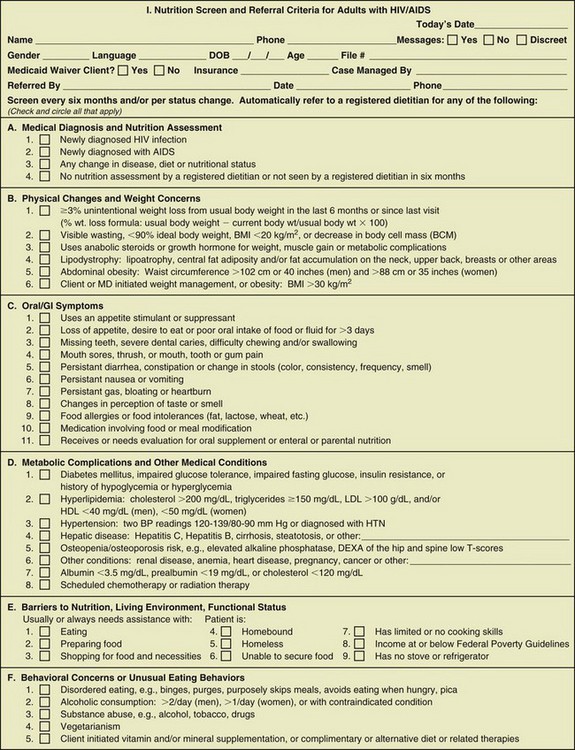

Patients who exhibit the various HIV-related symptoms or conditions listed in Figure 38-3 should be referred to a dietitian with expertise in managing this disease. A comprehensive nutrition assessment should be performed at the initial visit. In addition, regular monitoring and evaluation are essential to detect and manage any undesirable nutritional consequences of medical treatments or the disease process. Adverse nutrition implications are summarized in Table 38-6. Key factors for assessment are listed in Table 38-7.

TABLE 38-7

Factors to Consider in Nutrition Assessment

| Medical | Stage of HIV disease |

| Comorbidities | |

| Opportunistic infections | |

| Metabolic complications | |

| Biochemical measurements | |

| Physical | Changes in body shape |

| Weight or growth concerns | |

| Oral or gastrointestinal symptoms | |

| Functional status (i.e., cognitive function, mobility) | |

| Anthropometrics | |

| Social | Living environment (support from family and friends) |

| Behavioral concerns or unusual eating behaviors | |

| Mental health (i.e., depression) | |

| Economical | Barriers to nutrition (i.e., access to food, financial resources) |

| Nutritional | Typical intake |

| Food shopping and preparation | |

| Food allergies and intolerances | |

| Vitamin, mineral, and other supplements | |

| Alcohol and drug use |

FIGURE 38-3 Nutrition screen and referral criteria for adults with HIV and AIDS. (From ADA MNT Evidence Based Guides for Practice © 2005, American Dietetic Association, March 2005. For interim revisions see www.bivaidsdpg.org.)

Medical Factors

HIV infection should be confirmed by laboratory testing and not based on patient report (CDC, 2008b). The presence of comorbidities such as heart disease, diabetes, hepatitis, and OIs may complicate the patient’s treatment profile. The assessment should include the patient’s past medical history and pertinent immediate family history for heart disease, diabetes, cancers, or other disorders. Metabolic issues such as dyslipidemia and insulin resistance are common in people with HIV, and should be monitored. Biochemical measurements should be documented to determine course of HIV treatment, need for ART, efficacy of ART, and underlying malnutrition and nutrient deficiencies. Some common biochemical measurements include CD4 count, viral load, albumin, hemoglobin, iron status, lipid profile, liver function, renal function, glucose, insulin, and vitamin levels. See Table 38-8 for a list of common conditions associated with HIV and their nutritional implications.

TABLE 38-8

HIV-related Conditions with Specific Nutrition Implications

| Condition | Brief Description | Nutrition Implications |

| PCP | Potentially fatal fungal infection | Difficulty chewing and swallowing caused by shortness of breath |

| TB | Bacterial infection that attacks the lungs | Prolonged fatigue, anorexia, nutrient malabsorption, altered metabolism, weight loss |

| Cryptosporidiosis | Infection of small intestine caused by parasite | Watery diarrhea, abdominal cramping, malnutrition and weight loss, electrolyte imbalance |

| Kaposi’s Sarcoma | Type of cancer causing abnormal tissue growth under the skin | Difficulty chewing and swallowing caused by lesions in oral cavity or esophagus Diarrhea or intestinal obstruction caused by lesions in intestine |

| Lymphomas | Abnormal, malignant growth of lymph tissue | |

| Brain | Changes in motor and cognitive abilities | Inability to prepare food and coordinate movement |

| Small bowel | Malabsorption | Weight loss, diarrhea, loss of appetite |

| Cytomegalovirus (disseminated) | Infection caused by herpes virus | Loss of appetite, weight loss, fatigue, enteritis, colitis |

| Candidiasis | Infection caused by fungi or yeast | Oral sores in mouth, difficulty chewing and swallowing, change in taste |

| HIV-induced enteropathy | Idiopathic, direct or indirect effect of HIV on enteric mucosa | Chronic diarrhea, weight loss, malabsorption, changes in cognition and behavior |

| HIV encephalopathy (AIDS dementia) | Degenerative disease of brain cause by HIV infection | Loss of coordination and cognitive function, inability to prepare food |

| Pneumocystis jirovecii pneumonia | Infection caused by fungi | Fever, chills, shortness of breath, weight loss, fatigue |

| Mycobacterium avium complex (disseminated) | Bacterial infection in lungs or intestine, spreads quickly through bloodstream | Fever, cachexia, abdominal pain, diarrhea, malabsorption |

Coyne-Meyers K, Trombley LE: A review of nutrition in human immunodeficiency virus infection in the era of highly active antiretroviral therapy, Nutr Clin Prac 19:340, 2004.

Falcone EL et al: Micronutrient concentrations and subclincal atherosclerosis in adults with HIV, Am J Clin Nutr 91:1213, 2010.

McDermid JM et al: Mortality in HIV infection is independently predicted by host iron status and SLC11A1 and HP genotypes, with new evidence of a gene-nutrient interaction, Am J Clin Nutr 90:225, 2009.

Pitney CL et al: Selenium supplementation in HIV-infected patients: is there any potential clinical benefit? J Assoc Nurses AIDS Care 20:326, 2009.

Rodriguez M et al: High frequency of vitamin D deficiency in ambulatory HIV-positive patients, AIDS Res Hum Retroviruses 25:9, 2009.

AIDS, Acquired immune deficiency syndrome; HIV, human immunodeficiency virus; PCP, Pneumocystis pneumonia; TB, tuberculosis.

Physical Changes

The physical presentation of the patient should be considered during initial and follow-up assessments. Patients with HIV are aware of changes in their body shape and are instrumental in identifying these changes. Health care professionals should remember to ask patients about body shape changes every 3 to 6 months. Changes in body shape and fat redistribution can be monitored by anthropometric measurements. Commonly these are taken as circumferences around the waist, hip, mid-upper arm, and thigh, and as skinfold measurements of the tricep, subscapular, suprailiac, thigh, and abdomen. See Chapter 6. If a dorsocervical fat pad (fat behind the neck) is present, measurement of the neck diameter can help track changes in this area. These physical changes are referred to as HIV-associated lipodystrophy syndrome (HALS). Unintentional weight changes should be monitored closely because they can indicate progression of HIV disease. Peripheral neuropathy is a potential side effect, most frequently associated with NRTIs. The resulting nerve damage causes stiffness, numbness, or tingling generally in the lower extremities. Patients experiencing neuropathy may be unable to work or be physically active.

Social and Economic Factors

Depending on a patient’s mental status, psychosocial issues may take precedence over nutrition counseling. Depression is common, so the need to treat and provide services for mental health issues should be monitored. When individuals are unable to care for themselves, discussion with caretakers may be necessary to understand the patient’s nutrition history. Particular habits, food aversions, timing of meals with medications, and related concerns should be documented.

Access to safe, affordable, and nutritious food should be evaluated. Common barriers include cost, location of supermarkets, lack of transportation, and lack of knowledge of healthier choices. In addition, because medications are costly, they often compete with food for available resources.

Nutrient Recommendations

When collecting the diet history, a review of current intake, changes in intake, limitations with food access or preparation, food intolerances or allergies, supplement use, current medications, and alcohol and recreational drug use will help determine the potential for any nutrient deficiencies and assist in making individualized recommendations.

Adequate nutrition intake can help patients with HIV with symptom management and improve the efficacy of medications, disease complications, and overall quality of life. Refer to Figure 38-3 for a sample nutrition screening form. Note that a one-size-fits-all approach does not address the complexity of HIV. RDs must provide recommendations to improve nutritional status, immunity, and quality of life, address drug-nutrient interactions or side effects, and identify barriers to desirable food intake (Box 38-2).

In the early stages of nutrition therapy for HIV, the focus was on treatment and prevention of unintentional weight loss and wasting. Now with access to ART, new nutrition issues have arisen caused by HALS. HIV-related death from OIs has shifted to other chronic disease conditions such as heart disease and diabetes in healthier individuals who are living with HIV (Leyes, 2008).

Energy and Fluid

When determining energy needs, it is important to establish if the individual needs to gain, lose, or maintain weight. Other factors such as altered metabolism, nutrient deficiencies, severity of disease, comorbidities, and OIs should be taken into account when evaluating energy needs. Calculating energy and protein needs for this population is difficult because of other issues with wasting, obesity, HALS, and lack of accurate prediction equations. Some research suggests that resting energy expenditure is increased by approximately 10% in adults with asymptomatic HIV (Polo, 2007). After an OI, nutritional requirements increase by 20% to 50% in both adults and children (WHO, 2005a). Continuous medical and nutrition assessment is necessary to make adjustments as needed. Individuals with well-controlled HIV are encouraged to follow the same principles of healthy eating and fluid intake recommended for everyone.

Protein

The current recommended dietary reference intake (DRI) is 0.8 g of protein per kilogram of body weight per day for healthy individuals. Deficiency of protein stores and abnormal protein metabolism occur in HIV and AIDS, but no evidence exists for increased protein intake over and above that necessary to accompany the required increase in energy (WHO, 2005b). For people with HIV who have adequate weight and are not malnourished, protein supplementation may not be sufficient to improve lean body mass (Sattler, 2008). However, with an OI, an additional 10% increase in protein intake is recommended because of increased protein turnover (WHO, 2005b). If other comorbidities such as renal insufficiency, cirrhosis, or pancreatitis are present, protein recommendations should be adjusted accordingly.

Fat

There is evidence that dietary fat requirements are different with HIV infection (WHO, 2005b). General heart-healthy guidelines should be the focus for dietary fat intake. Recent research has focused on immune function and ω-3 fatty acids. There is some research to suggest increasing the intake of ω-3 fatty acids in individuals with HIV who have elevated serum triglycerides. See below.

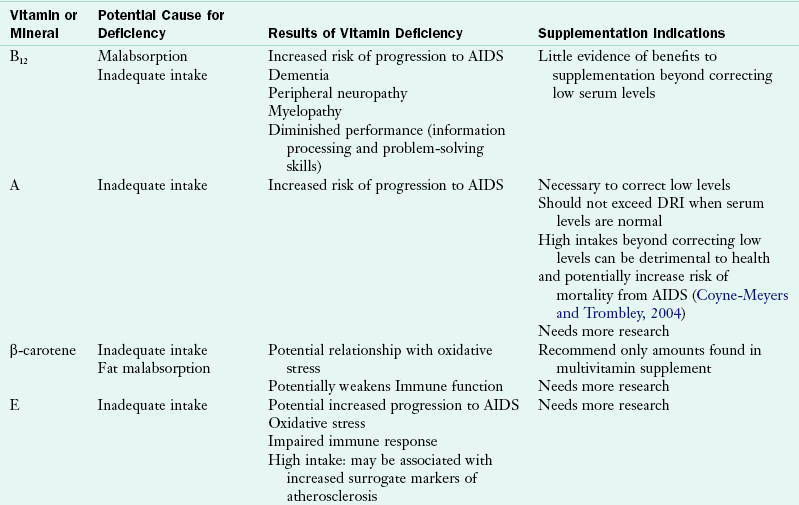

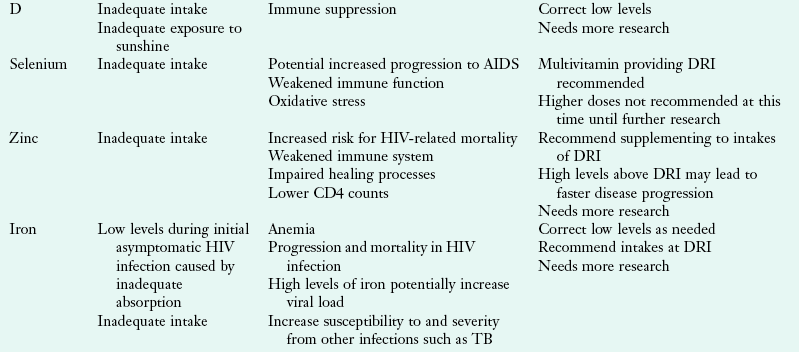

Micronutrients

Vitamins and minerals are important for optimal immune function. Nutrient deficiencies can affect immune function and lead to disease progression. Micronutrient deficiencies are common in people with HIV infection as a result of malabsorption, drug-nutrient interactions, altered metabolism, gut infection, and altered gut barrier function. Vitamin A, zinc, and selenium serum levels are often low during times of response to infection, so it is important to assess dietary intake to determine whether correction of serum micronutrients is warranted (Coyne-Meyers and Trombley, 2004).

There are benefits to correcting some depleted serum levels of micronutrients. Low levels of vitamins A, B12, and zinc are associated with faster disease progression (Coyne-Meyers and Trombley, 2004). Higher intakes of vitamins C and B have been associated with increased CD4 counts and slower disease progression to AIDS (Coyne-Meyers and Trombley, 2004). The Nutrition for Healthy Living study found that minorities and women tend to have lower micronutrient intakes and may benefit from nutrition counseling and dietary assessment (Jones, 2006).

Studies on micronutrients are difficult to interpret because there are a variety of study designs and outcomes. Serum micronutrient levels reflect conditions such as acute infection, liver disease, technical parameters, and recent intake. Adequate micronutrient intake through consumption of a balanced, healthy diet should be encouraged. However, diet alone may not be sufficient in people with HIV. A multivitamin and mineral supplement that provides 100% of the DRI may also be recommended. Megadosing on some micronutrients such as vitamins A, B6, D, E, and copper, iron, niacin, selenium, and zinc may be detrimental to health outcomes and may not warrant protection against prevention of chronic diseases. At this time, there is no evidence to support micronutrient supplementation in adults with HIV-infection above the recommended levels of the DRI (Kawai, 2010, WHO, 2005c). See Table 38-9 for a summary.

TABLE 38-9

Common Micronutrient Deficiencies and Indications for Supplementation

Coyne-Meyers K, Trombley LE: A review of nutrition in human immunodeficiency virus infection in the era of highly active antiretroviral therapy, Nutr Clin Prac 19:340, 2004.

Falcone EL et al: Micronutrient concentrations and subclincal atherosclerosis in adults with HIV, Am J Clin Nutr 91:1213, 2010.

McDermid JM et al: Mortality in HIV infection is independently predicted by host iron status and SLC11A1 and HP genotypes, with new evidence of a gene-nutrient interaction, Am J Clin Nutr 90:225, 2009.

Pitney CL et al: Selenium supplementation in HIV-infected patients: is there any potential clinical benefit? J Assoc Nurses AIDS Care 20:326, 2009.

Rodriguez M et al: High frequency of vitamin D deficiency in ambulatory HIV-positive patients, AIDS Res Hum Retroviruses 25:9, 2009.

AIDS, Acquired immune deficiency syndrome; DRI, dietary reference intake; TB, tuberculosis.

Special Considerations

Wasting implies unintentional weight loss and loss of lean body mass, which have been strongly associated with an increased risk of disease progression and mortality. Despite the efficacy of ART, wasting continues to be a common problem in the HIV population. Wasting may be caused by a combination of factors including inadequate dietary intake, malabsorption, and increased metabolic rates from viral replication or complications from the disease (WHO, 2005b). Until the underlying cause of weight loss is discovered, it will remain difficult to target effective nutrition therapy.

Obesity

Obesity in people with HIV has also been noted (Hendricks, 2006). Unintentional weight loss in HIV infection has been associated with mortality, but there needs to be more careful review in overweight or obese HIV-infected individuals. In the era of ART, it is no longer believed that continuously gaining body weight is a protective cushion against HIV-related wasting and progression to AIDS.

Some of the ART medications increase the risk of hyperlipidemia, insulin resistance, and diabetes. It is important to monitor these risk factors and provide nutrition recommendations to maintain a healthy weight. Physical activity, aerobic exercise, and resistance training are recommended to work synergistically with optimal nutrition intake to achieve a healthy weight and maintain lean body mass.

HIV-Associated Lipodystrophy Syndrome (HALS)

HALS refers to the metabolic abnormalities and body shape changes seen in patients with HIV, similar to the metabolic syndrome found in the general population. The typical body shape changes include fat deposition (generally visceral adipose tissue in the abdominal region or as a dorsocervical fat pad and breast hypertrophy) or fat atrophy seen as loss of subcutaneous fat in the extremities, face, and buttocks. The metabolic abnormalities include hyperlipidemia (particularly high triglycerides and low-density lipoprotein [LDL] cholesterol and low high-density lipoprotein [HDL] cholesterol) and insulin resistance. There is no consensus on the clinical definition of HALS and the manifestations vary greatly from patient to patient. Each part of the syndrome may occur independently or simultaneously.

The cause of HALS is multifactorial and includes duration of HIV infection, duration of ART medications, age, gender, race and ethnicity, increased viral load, and increased body mass index. Physical changes should be discussed with the health care team. It is important to monitor these changes by taking anthropometric measurements. Monitoring trends with body weight is important; however, doing so will not likely identify body shape changes. Generally, there is a shift in body composition even though weight remains stable. Taking waist, hip, arm, mid-upper arm, and thigh circumference measurements and tricep, subscapular, suprailiac, abdominal, and thigh skinfold measurements are useful in monitoring exact locations of either fat hypertrophy or atrophy.

Nutrition interventions associated with HALS are limited. For nutrition recommendations, the guidelines set by the National Cholesterol Education Program and American Diabetes Association are followed (see Chapters 31 and 34). Recommendations for physical activity, including aerobic exercise and resistance training, should complement dietary intake. In addition, special focus should be on achieving adequate dietary fiber intake. This can potentially decrease the risk of fat deposition (Dong et al., 2006; Hendricks, 2003) and improve glycemic control.

For patients who have high triglycerides, ω-3 fatty acids may be useful. Omega-3 fatty acids decrease serum triglycerides and may reduce inflammation and improve depression. In some studies, 2-4 g of fish oil supplements per day have been shown to lower serum triglyceride levels in patients with HIV (Wohl, 2005; Woods, 2009). Potential side effects from supplementation include GI distress, hyperglycemia, and increased LDL cholesterol levels. Use of supplements should be monitored and discussed with the health care team.

Hiv in Women

Around the world, 15.7 million women are living with HIV or AIDS. In the United States, women accounted for more than 10,000 (25%) of the estimated number of new HIV infections in 2008 (CDC, 2010). The highest rate of new HIV infection is seen in African American women, which is 15 times as high as that of white women and nearly 4 times that of Hispanic women (CDC, 2010).

Although HIV-infected women are a minority in the United States, there are several factors that put them at higher risk of contracting HIV. Biologically, women are more likely to get HIV during unprotected vaginal sex because the lining of the vagina provides a larger area that can be exposed to HIV-infected semen. Barriers to receiving appropriate medical care also exist. Social and cultural stigma, lack of financial resources, responsibility to care for others, and fear of disclosure may prevent women from seeking proper care.

Preconception and Prenatal Considerations

HIV-infected women of child-bearing age should receive counseling prior to conception to learn how to decrease the risk of mother-to-child transmission. Current recommendations include prenatal screening for HIV, initiation of ART during pregnancy, and ART for the child once it is born. In the United States, these interventions have reduced the risk of mother-to-child transmission to less than 2% (DHHS, 2010a). Similar to HIV-negative women, adequate nutritional status and nutrient deficiencies should be monitored during pregnancy. Supplementation of vitamins B, C, and E have been shown to reduce the incidence of adverse pregnancy outcomes (e.g., low birth weight, fetal death) and decrease rates of mother-to-child transmission in women with compromised immune and nutrition status (Kawai, 2010). It is important to note if women have deficient serum vitamin A levels prior to supplementation, since different serum levels may affect risk of HIV transmission. Benefits may only be noted in those needing repletion of low levels.

Postpartum and Other Considerations

In the United States breastfeeding is not recommended for HIV-infected women, including those on ART, where safe, affordable, and feasible alternatives are available and culturally appropriate (DHHS, 2009). In developing countries, recommendations may differ depending on safety and availability of formula and access to clean drinking water.

Hiv in Children

An estimated 430,000 new HIV infections occurred globally among children younger than the age of 15 in 2008 (UNAIDS and WHO, 2009). In the United States an estimated 200 HIV-infected children are born each year. The majority of these infections stem from mother-to-child transmission in utero, during delivery, or through consumption of HIV-infected breastmilk. Recently, premastication (chewing foods or medicine before administering to a child) was reported as a route of transmission through blood in saliva (CDC, 2011).

Growth is the most valuable indicator of nutritional status in childhood. Poor growth may be an early indicator for progression of HIV disease. Growth failure can result from HIV infection itself and HIV-associated OIs (Guillen, 2007). Weight and height of HIV-infected children generally lags behind uninfected children of the same age. Loss of lean body mass with no changes in total body weight can also occur. To appropriately measure body changes, serial anthropometric measurements should be recorded, along with tracking of height and weight on growth charts (Sabery et al., 2009).

HIV treatment has improved the clinical outcomes for children, with ART initiation resulting in significant catch-up in weight and height but not to the level of uninfected children. The presence of HALS seen in adults is also common in children. With the increasing number of years on ART, more morphologic and metabolic abnormalities, as described in the section on HALS, are being documented in children (Sabery and Duggan, 2009). Multivitamin and micronutrient supplementation may be beneficial at the DRI levels for children who are malnourished. Research does not currently support any supplementation at higher doses.

Complementary and Alternative Therapies

In general, any treatment method that is not practiced in conventional medicine is considered complementary and alternative medicine (CAM). Dietary supplements, herbal treatments, megavitamins, acupuncture, yoga, and meditation are just a few of the therapies that are categorized as CAM. See Chapter 13.

The use of CAM is prevalent in patients with HIV infection. On average 60% of people living with HIV use CAM to treat HIV-related health concerns (Littlewood, 2008). People experiencing greater HIV symptom severity and longer disease duration are more likely to use CAM in an attempt to delay disease progression and alleviate side effects of HIV infection and treatment (Bormann, 2009). In addition, CAM use is more common in men who have sex with men, nonminorities, the better educated, and less impoverished individuals (Littlewood, 2008).

Despite the high percentage of CAM use, only one third of patients disclose CAM use to their health care providers (Liu, 2009). Some patients with HIV have noted benefits with taking dietary supplements; however, potential interactions with ART medications should be addressed (Hendricks, 2007). Therefore it is important that each patient be questioned carefully about use of alternative therapies, particularly those taken orally or subcutaneously. Information should be collected on the brands, dosage, frequency, timing, duration, and cost of the supplements. This should be compared with additional clinical information such as current medications, biochemical parameters, and nutrition intake. Each item should be researched for potential drug-drug and drug-nutrient interactions because they may interfere with ART use. For example, garlic and St. John’s wort (Hypericum perforatum) decrease blood levels of ART medications, decreasing the efficacy of ART and potentially leading to drug resistance.

A key point in counseling patients who are using alternative therapies is to understand why they choose to use them. Most studies have found that there may not be any additional benefit to supplementing beyond correcting deficiencies. Food should be recommended first and patients should keep in mind that more is not always better. Caution should be used because dietary supplement labels can make a statement of nutrition support and health benefit, but it must be accompanied by the disclaimer, “This statement has not been evaluated by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA). This product is not intended to diagnose, treat, cure, or prevent any disease.” Adverse event reporting for dietary supplements is voluntary, leading to a underreporting or underestimation of events.

American Dietetic Association Infectious Disease Dietetic Practice Group

Clinical Guidelines on HIV/AIDS Treatment, Prevention, and Research

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention HIV Research, Prevention, and Surveillance

Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS

The National Center for Complementary and Alternative Medicine

References

American Dietetic Association. Position paper on nutrition intervention and human immunodeficiency virus infection. J Am Diet Assoc. 2010;110:1105.

Bangsberg, DR. Less than 95% adherence to nonnucleoside reverse-transcriptase inhibitor therapy can lead to viral suppression. Clin Infect Dis. 2006;43:939.

Bormann, J, et al. Predictors of complementary/alternative medicine use and intensity of use among men with HIV infection from two geographic areas in the United States. J Assoc Nurses AIDS Care. 2009;20:468.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Coinfection with HIV and hepatitis C virus. Accessed 12 July 2010 from http://www.cdc.gov/hiv/resources/factsheets/coinfection.htm, 2007.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). HIV in the United States: an overview. Accessed 12 July 2010 from http://www.cdc.gov/hiv/topics/surveillance/resources/factsheets/pdf/us_overview.pdf, 2010.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). HIV prevalence estimates—United States. Accessed 12 July 2010 from http://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/preview/mmwrhtml/mm5739a2.htm, 2006.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). HIV surveillance report. Accessed 12 July 2010 from http://www.cdc.gov/hiv/surveillance/resources/reports/2008report/pdf/2008SurveillanceReport.pdf, 2008.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Revised surveillance case definitions for HIV infection among adults, adolescents, and children aged <18 months and for HIV infection and AIDS among children aged 18 months to <13 years—United States. MMWR. 2008;57(No.RR-10):1.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Premastication of food by caregivers of HIV-exposed children—nine U.S. sites, 2009–2010. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2011;60(9):273–275.

Coyne-Meyers, K, Trombley, LE. A review of nutrition in human immunodeficiency virus infection in the era of highly active antiretroviral therapy. Nutr Clin Prac. 2004;19:340.

Department of Health and Human Services (DHHS). Panel on antiretroviral guidelines for adults and adolescents: working guidelines for the use of antiretroviral agents in HIV-1-infected adults and adolescents. Accessed 12 July2010 from http://aidsinfo.nih.gov/contentfiles/AdultandAdolescentGL.pdf.

Department of Health and Human Services (DHHS), Panel on Treatment of HIV-Infected Pregnant Women and Prevention of Perinatal Transmission. Recommendations for Use of Antiretroviral Drugs in Pregnant HIV-1-Infected Women for Maternal Health and Interventions to Reduce Perinatal HIV Transmission in U.S. 2010. Accessed12 July 2010 from. http://aidsinfo.nih.gov/ContentFiles/PerinatalGL.pdf

Dong, KR, et al. Dietary glycemic index of human immunodeficiency virus-positive men with and without fat deposition. J Am Diet Assoc. 2006;106:728.

Falcone, EL, et al. Micronutrient concentrations and subclincal atherosclerosis in adults with HIV. Am J Clin Nutr. 2010;91:1213.

Guillen, S, et al. Impact on weight and height with the use of HAART in HIV-infected children. Pediatr Infectious Dis J. 2007;26:334.

Hammer, SH, et al. 2006 recommendations of the International AIDS Society—USA Panel. JAMA. 2007;296:827.

Hendricks, K, Gorbach, S. Nutrition issues in chronic drug users living with HIV infection. Addiction Sci Clin Prac. 2009;5(1):16.

Hendricks, KM, et al. Dietary supplement use and nutrient intake in HIV-infected persons. AIDS Reader. 2007;1:1.

Hendricks, KM, et al. Obesity in HIV-infection: dietary correlates. J Am Coll Nutr. 2006;25:321.

Hendricks, KM, et al. High-fiber diet in HIV-positive men is associated with lower risk of developing fat deposition. Am J Clin Nutr. 2003;78:790.

Jones, CY, et al. Micronutrient levels and HIV disease status in HIV-infected patients on highly active antiretroviral therapy in the Nutrition for Healthy Living cohort. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2006;43:475.

Kawai, K, et al. A randomized trial to determine the optimal dosage of multivitamin supplements to reduce adverse pregnancy outcomes among HIV-infected women in Tanzania. Am J Clin Nutri. 2010;91:391.

Leyes, P, et al. Use of diet, nutritional supplements and exercise in HIV-infected patients receiving combination antiretroviral therapies: a systematic review. Antiretroviral Ther. 2008;13:149.

Littlewood, R, Vanable, P. Complementary and alternative medicine use among HIV+ people: research synthesis and implications for HIV care. AIDS Care. 2008;20:1002.

Liu, C, et al. Disclosure of complementary and alternative medicine use to health care providers among HIV-infected women. Care STDS. 2009;23:965.

McDermid, JM, et al. Mortality in HIV infection is independently predicted by host iron status and SLC11A1 and HP genotypes, with new evidence of a gene-nutrient interaction. Am J Clin Nutr. 2009;90:225.

Pitney, CL, et al. Selenium supplementation in HIV-infected patients: is there any potential clinical benefit? J Assoc Nurses AIDS Care. 2009;20:326.

Polo, R, et al. Recommendations from SPNS/GEAM/SENBA/SENPE/AEDN/SEDCA/GESIDA on nutrition in the HIV-infected patient. Nutr Hosp. 2007;22:229.

Raffa, JD, et al. Intermediate highly active antiretroviral therapy adherence thresholds and empirical models for the development of drug resistance mutations. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2008;47:397.

Rodriguez, M, et al. High frequency of vitamin D deficiency in ambulatory HIV-positive patients. AIDS Res Hum Retroviruses. 2009;25:9.

Sabery, N, Duggan, C. A.S.P.E.N. clinical guidelines: nutrition support of children with human immunodeficiency virus infection. JPEN J Parenteral Enteral Nutrition. 2009;33:588.

Sabery, N, et al. Pediatric HIV. In: Hendricks K, et al, eds. Nutrition management of HIV and AIDS. Chicago: American Dietetic Association, 2009.

Sattler, FR, et al. Evaluation of high-protein supplementation in weight-stable HIV-positive subjects with a history of weight loss: a randomized, double-blind, multicenter trial. Am J Clin Nutr. 2008;88:1313.

Tang, AM, et al. Heavy injection drug use is associated with lower percent body fat in a multi-ethnic cohort of HIV-positive and HIV-negative drug users from three US cities. Am J Drug Alcohol Abuse. 2010;36:78.

Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS (UNAIDS). 2008 Report on the global AIDS epidemic. Accessed 12 July 2010 from http://www.unaids.org/en/KnowledgeCentre/HIVData/GlobalReport/2008/2008_Global_report.pdf.

Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS (UNAIDS) and World Health Organization (WHO). 2009 AIDS epidemic update. Accessed 12 July 2010 from http://data.unaids.org/pub/Report/2009/JC1700_Epi_Update_2009_en.pdf.

Wanke, C, et al. Overview of HIV/AIDS today. In: Hendricks, K., eds. Nutrition management of HIV and AIDS. Chicago: American Dietetic Association, 2009.

Wohl, DA. Fish oils curb hypertriglyceridemia in HIV patients. Clin Infect Dis. 2005;41:1498.

Woods, MN, et al. Effect of a dietary intervention and n-3 fatty acid supplementation on measures of serum lipid and insulin sensitivity in persons with HIV. Am J Clin Nutr. 2009;90:1566.

World Health Organization (WHO). Executive Summary of a scientific review: Consultation on Nutrition and HIV/AIDS in Africa: Evidence, lessons and recommendations for action. Durban, South Africa. Accessed on 26 July 2010 from http://www.who.int/nutrition/topics/Executive_Summary_Durban.pdf, 2005.

World Health Organization (WHO). Macronutrients and HIV/AIDS: a review of current evidence: Consultation on Nutrition and HIV/AIDS in Africa: evidence, lessons, and recommendations for action. Durban, South Africa, Accessed on 26 July 2010 from http://www.who.int/nutrition/topics/PN1_Macronutrients_Durban.pdf, 2005.

World Health Organization (WHO). Micronutrients and HIV/AIDS: a review of current evidence: Consultation on Nutrition and HIV/AIDS in Africa: evidence, lessons, and recommendations for action. Durban, South Africa, Accessed on 26 July 2010 from http://www.who.int/nutrition/topics/PN2_Micronutrients_Durban.pdf, 2005.

World Health Organization (WHO). Rapid advice: revised WHO principles and recommendations on infant feeding in the context of HIV. Accessed 12 July 2010 from http://whqlibdoc.who.int/publications/2009/9789241598873_eng.pdf, 2009.