Food and Nutrient Delivery

Nutrition Support Methods

Sections of this chapter were written by Charles Mueller, PhD, RD, CNSD, CDN and Abby S. Bloch, PhD, Rd, FADA for the previous edition of this text.

Nutrition support is the delivery of formulated enteral or parenteral nutrients for the purpose of maintaining or restoring nutritional status. Enteral nutrition (EN) refers to the provision of nutrients into the gastrointestinal tract (GIT) through a tube or catheter. In certain instances EN may include the use of formulas as oral supplements or meal replacements. Parenteral nutrition (PN) is the provision of nutrients intravenously.

Rationale And Criteria For Appropriate Nutrition Support

When patients are unable to eat enough to support their nutritional needs for more than a few days, nutrition support should be considered. EN should be the first consideration. Using the gut for nutrition versus using only PN is preferable for preserving the mucosal barrier function and integrity. The act of feeding the GIT has been shown to attenuate the catabolic response and preserve immunologic function (ASPEN, 2010). EN decreases the incidence of hyperglycemia when compared with PN. At this time, there is insufficient evidence to draw conclusions about the effect of EN versus PN on length of stay and mortality (American Dietetic Association, 2010).

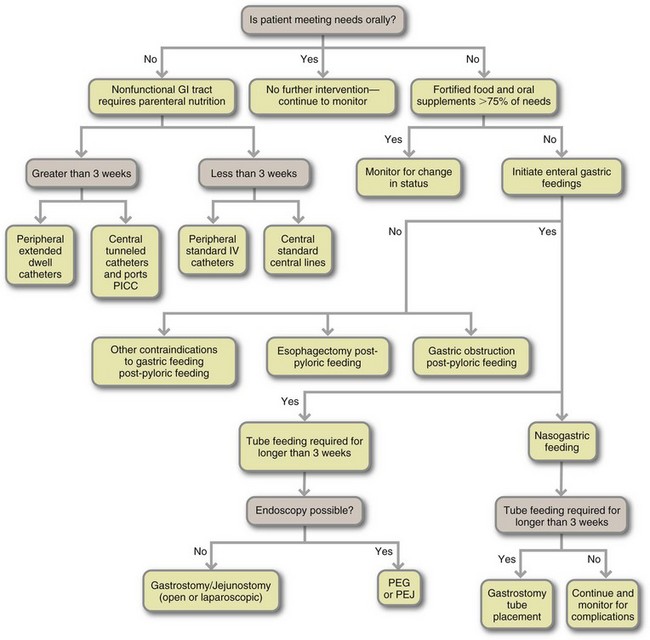

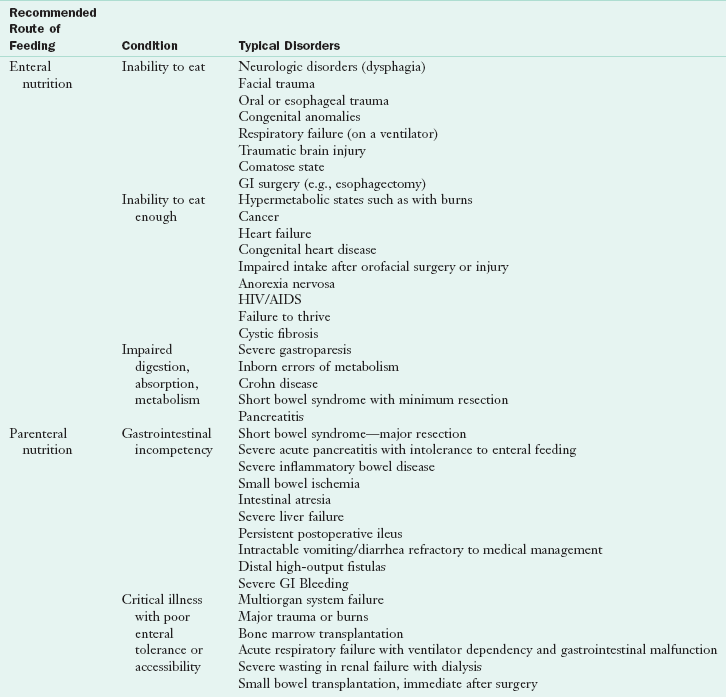

Criteria must be applied to select appropriate candidates for nutrition support (Table 14-1). PN should be used in patients who are or will become malnourished and who do not have sufficient gastrointestinal function to be able to restore or maintain optimal nutritional status (McClave et al., 2009). Figure 14-1 presents an algorithm for selecting EN and PN routes. Although these guidelines can assist with the selection of the best type of nutrition, the choice is not always easy. For example, access methods are not universally available in every health care setting. Therefore, if a specific type of small bowel access is not available for EN, PN may be the only realistic option. Often PN is used temporarily until adequate gastrointestinal function can support either EN or oral intake. In this situation a combination of feeding methods is used (see “Transitional Feeding” later in the chapter).

TABLE 14-1

Conditions That Often Require Nutrition Support

AIDS, Acquired immune deficiency syndrome; GI, gastrointestinal; HIV, human immunodeficiency virus.

McClave SA et al: Guidelines for the provision and assessment of nutrition support therapy in the adult critically ill patient, JPEN J Parenter Enteral Nutr 33: 277, 2009.

In a computerized prescriber order entry (CPOE), the prescriber enters orders directly into a computer system, usually aided by decision-support technology (Bankhead et al., 2009). Although methods of nutrition support can be standardized for the course of certain disease states or treatments, every patient presents an individual challenge. Nutrition support must often be adapted to unanticipated developments or complications. The optimal treatment plan requires interdisciplinary collaboration that is closely aligned with the overall patient care plan. In a few instances nutrition support may be warranted but physically impossible to implement within the overall care plan. Conversely, nutrition support may be achievable but not warranted because of the prognosis, unacceptable risk, or the patient’s right to self-determination. In all cases, it is important to prevent errors in ordering, delivery, and monitoring of nutrition support to prevent undesirable risks or outcomes (sentinel events) such as an unexpected death, serious physical injury with loss of limb or function, or psychological injury (Joint Commission, 2010).

Enteral Nutrition

By definition, enteral implies using the GIT, primarily via “tube feeding.” When a patient has been determined to be a candidate for EN, the location of nutrient administration and type of enteral access device is selected. Enteral access selection depends on the (1) anticipated length of time enteral feeding will be required, (2) degree of risk for aspiration or tube displacement, (3) patient’s clinical status, (4) presence or absence of normal digestion and absorption, (5) patient’s anatomy (e.g., feeding tube placement is not possible in some very obese patients), and (6) whether a surgical intervention is planned.

In a closed enteral system the container or bag is prefilled with sterile liquid formula by the manufacturer, and is ready to administer. In an open enteral system, the person administering the feeding must open and pour the feeding into the container or bag. Both systems are effective when sanitation is a priority. Hang time is the length of time an enteral formula is considered safe for delivery to the patient; most facilities allow a 4 hour hang time before the product is changed for open systems and 24-48 hours for closed systems.

Short-Term Enteral Access

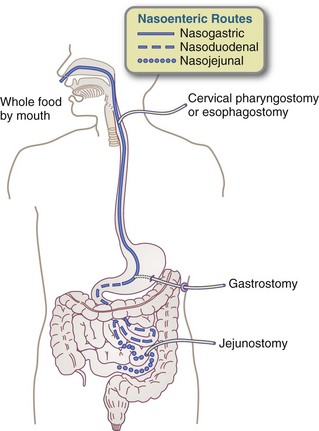

Nasogastric tubes (NGTs) are the most common way to access the GIT. They are generally appropriate only for those requiring short-term EN, which is defined as 3 or 4 weeks. Typically, the tube is inserted at the bedside by a nurse or dietitian. The tube is passed through the nose into the stomach (Figure 14-2). Patients with normal gastrointestinal function tolerate this method, which takes advantage of normal digestive, hormonal, and bactericidal processes in the stomach. Rarely, complications can occur (Box 14-1).

NG feedings can be administered by bolus injection or by intermittent or continuous infusions (see “Administration” later in this chapter). Soft, flexible, and well-tolerated polyurethane or silicone tubes of various diameters, lengths, and design features may be used, depending on formula characteristics and feeding requirements. Tube placement is verified by aspirating gastric contents in combination with auscultation of air insufflation into the stomach or by radiographic confirmation of the tube tip location. Techniques for placing a tube are described by Metheny and Meert (2004).

Gastric versus Small-Bowel Feeding

The decision to use a small-bowel feeding tube versus a gastric tube is multifaceted. It is much easier to place tubes into the stomach; therefore gastric feedings generally result in a patient being fed sooner. However, ease of access is only one consideration. Gastric feedings may not be well tolerated, especially in critically ill patients (see Chapter 39). Signs and symptoms of intolerance to gastric feeding include abdominal distention and discomfort; vomiting; and persistent, high gastric residuals (defined as more than 400 mL). Patients receiving gastric feedings are often thought to be at higher risk of aspiration pneumonia, but this is debatable (Bankhead et al., 2009).

Nasoduodenal or Nasojejunal Route

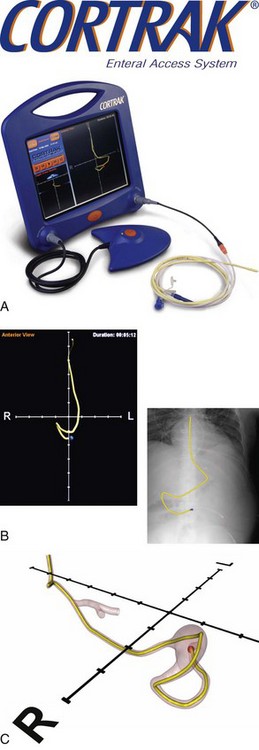

For those patients unable to tolerate gastric feedings who require relatively short-term nutrition support, a nasoduodenal tube (NDT) or a nasojejunal tube (NJT) is indicated. This requires that the tip of the tube pass through the pylorus and into the duodenum or pass all the way through the duodenum and into the jejunum. Positioning of these tubes requires one of the following techniques: (1) intraoperative placement (generally not just for the purpose of placing a feeding tube), (2) endoscopic or fluoroscopic guidance, (3) spontaneous placement that depends on a gastric tube migrating into the duodenum by peristalsis, or (4) bedside placement using a computer guidance system (Figure 14-3). Spontaneous migration of a gastric tube cannot be used for an NJT. Confirmation that the tube has migrated to the correct position can take several days and requires x-ray confirmation. This can result in delayed feedings

Long-Term Enteral Access

When enteral feedings are necessary for more than 3-4 weeks, gastrostomy or jejunostomy should be considered to prevent some of the complications related to nasal and upper GIT irritation (see Box 14-1) and for the general comfort of the patient (Figure 14-4). These procedures can be done surgically and this may be the most efficient method if the patient is otherwise undergoing surgery (e.g., patients undergoing esophagectomies commonly have jejunal feeding tubes placed at the time of surgery). Nonoperative procedures are now far more common.

FIGURE 14-4 A man with a gastrostomy tube out hiking. (From Oley Foundation, Albany NY www.oley.org.)

The percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy (PEG) is a nonsurgical technique for placing a tube directly into the stomach through the abdominal wall; the technique is performed using an endoscope, with the patient under local anesthesia. Tubes are endoscopically guided from the mouth into the stomach or the jejunum and then brought out through the abdominal wall. The short procedural time required for insertion, limited need for anesthesia, and minimum wound complications also make it preferable for the physician and others caring for the patient.

PEG tubes used are generally large bore (feeding tubes are measured as french size), making clogging less likely. It is possible to convert a PEG to a gastrojejunostomy by threading a small-bore tube through the PEG tube into the jejunum using either fluoroscopy or endoscopy. PEGs may have a short piece of tubing that can be used to inject feedings with a syringe or to connect to a feeding bag. PEGs that are “low profile” are flush to the skin. These feeding tubes, also known as “buttons”, are a good choice for those patients prone to pulling on their tubes (e.g., children, older adults with dementia). They are also beneficial for those who are active and want to avoid the bulkiness of a feeding tube under their clothing.

Other Minimally Invasive Techniques

High-resolution video cameras have made percutaneous radiologic and laparoscopic gastrostomy and jejunostomy enteral access an option for patients in whom endoscopic procedures are contraindicated. Using fluoroscopy, a radiologic technique, tubes can be guided visually into the stomach or the jejunum and then brought out through the abdominal wall to provide the access route for enteral feedings. Laparoscopic or fluoroscopic techniques are used in some facilities and offer alternative options for enteral access (Nikolaidis, 2005).

Multiple Lumen Tubes

Gastrojejunal dual tubes are available for either endoscopic or surgical placement. These tubes are designed for patients in whom prolonged gastrointestinal decompression is anticipated. The multiple lumen tube has one lumen for decompression and one to feed into the small bowel. These tubes are used for early postoperative feeding.

Formula Content and Selection

A wide variety of enteral feeding products are commercially available. A modular enteral feeding is created by combining separate nutrient sources or by modifying existing formulas. For the most sterile product, it is best to use standardized commercial products and to avoid using multiple additives or drugs. The less the products are handled, the safer they are for the patient.

Enteral formulas can be classified as (1) standard polymeric formula; (2) elemental, predigested, or chemically defined; or 3) specialized. Many formulas are available within each of these categories. Hospitals and other health care institutions generally have a product formulary that determines which products can be used in that facility. The suitability of an enteral formula for a specific patient should be based on the functionality of the GIT, the clinical status of the patient, and the patient’s nutrient needs. In some situations the cost of the formula is a major factor. In the past, osmolality was considered key to patient tolerance and the goal was to provide feedings that were the same osmolality as body fluids (290 mOsm/kg). However, studies done in the mid-1980s showed that patients can tolerate feedings with a wide variance of osmolarity.

Formulas are classified in a variety of ways, usually based on protein or overall macronutrient composition. Most patients with a variety of clinical conditions tolerate standard formulas intended to meet the nutritional requirements of general patient populations. The formulas are lactose-free, contain 1 to 1.2 kcal/mL, and are used as over-the-counter oral supplements and tube-feeding formulas. Some standard formulas are more concentrated to provide 1.5 to 2 kcal/mL when fluid restriction is required for patients with cardiopulmonary, renal, and hepatic failure, or for patients who have trouble tolerating high-volume feedings. Formulas intended for use as supplements to oral diets are flavored and contain simple sugars for palatability. See Appendix 32.

The Food and Drug Administration states that enteral formulas are a food; thus they are not under regulatory control. Manufacturers do not need to register their products with FDA nor get FDA approval before producing or selling them. Products are often introduced with little scientific evidence to support claims that are made. Evaluation of the suitability and efficacy of products, whether for individual or institutional use, is increasingly complex. A product making claims of pharmacologic effects must be evaluated using clinical evidence before a decision is made to use it (Box 14-2).

Protein

The amount of protein in enteral formulas varies from 6% to 25% of total kilocalories. The protein is typically derived from casein, whey, or soy protein isolate. Standard formulas provide intact protein, whereas elemental or predigested formulas have protein as di- and tripeptides and amino acids. The latter require less digestion. Specialized formulas may have the protein as crystalline amino acids for conditions such as renal or hepatic failure. These truly elemental formulas may also be used in the case of severe allergies. (Gottschlich 2006), In some cases specific amino acids have been added to enteral formulas. For example, arginine is added to renal products and critical care products because it is considered to be a conditionally essential amino acid in those clinical situations. See Chapter 39 for further discussion.

Carbohydrate

The percentage of total calories provided as carbohydrates in enteral formulas varies from 30% to 85% of kilocalories. Corn syrup solids are usually the carbohydrate found in standard formulas. Sucrose is added to flavored formulas that are meant for oral consumption. Hydrolyzed formulas have carbohydrate from cornstarch or maltodextrin. A recent innovation in the carbohydrate component of enteral formulas is fructooligosaccharides (FOS). These oligosaccharides are fermented to short-chain fatty acids and used as fuel by colonocytes (Charney, 2006).

Formulas are lactose-free. Lactose is not used as a carbohydrate source in most formulas because lactase deficiency is common in acutely ill patients. Fiber or carbohydrate that cannot be digested by human enzymes, although digested by colonic microflora into short-chain fatty acids, is frequently added to enteral formulas. Fibers are classified as water soluble (pectins and gums) or water insoluble (cellulose or hemicellulose) (see Chapters 1 and 3). The effectiveness of different fibers in enteral formulas used to treat gastrointestinal symptoms in acutely ill patients is controversial (see Chapter 39).

Lipid

Lipid varies from 1.5% to 55% of the total kilocalories in enteral formulas; between 15% and 30% of the total kilocalories of standard formulas are provided by lipids, usually from corn, soy, sunflower, safflower, or canola oils. Elemental formulas usually have minimum amounts of long-chain fat. Approximately 2% to 4% of daily energy intake from linoleic and linolenic acid is necessary to prevent essential fatty acid deficiency (EFAD). The remainder of the fat in enteral formulas is in the form of long-chain and medium-chain triglycerides (MCTs). Formulas contain a combination of ω-3 fatty acids and ω-6 fatty acids. The ω-3 fatty acids include eicosapentaenoic acid and docosahexanoic acid. These are considered advantageous compared with ω-6 fatty acids because of their antiinflammatory effect; see Chapter 6.

MCTs can be added to enteral formulas because they do not require bile salts or pancreatic lipase for digestion and are absorbed directly into the portal circulation. Most formulas provide 0% to 85% of fat as MCTs. MCTs do not provide the essential linoleic or linolenic acids; they must therefore be provided in combination with long-chain triglycerides.

Vitamins, Minerals, and Electrolytes

Most, but not all available formulas are designed to meet the dietary reference intakes (DRIs) for vitamins and minerals if a sufficient volume is taken. However, DRIs are intended for healthy populations, not for acute or chronically ill people. Formulas intended for use in renal and hepatic failure are intentionally low in specific vitamins, minerals, and electrolytes. In contrast, disease-specific formulas often are supplemented with antioxidant vitamins and minerals with the intention of improving immune function and accelerating wound healing. Electrolytes are provided in relatively modest amounts compared with the oral diet and may require supplementation when diarrhea or drainage losses occur.

Fluid

Fluid needs for adults can be estimated at 1 mL of water per kilocalorie consumed, or 30 to 35 mL/kg of usual body weight (see Chapter 7). Without an additional source of fluid, tube-fed patients may not get enough free water to meet their needs, particularly when concentrated formulas are used. Standard (1 kcal/mL) formulas contain approximately 85% water by volume, but concentrated (2 kcal/mL) formulas contain only approximately 70% water by volume. All sources of fluid being given to a patient receiving EN, including feeding tube flushes, medications, and intravenous fluids, should be considered when determining and calculating a patient’s intake. Additional water can be provided through the feeding tube as needed.

Administration

The three common methods of tube-feeding administration are (1) bolus feeding, (2) intermittent drip, and (3) continuous drip. Method selection is based on the patient’s clinical status, living situation, and quality-of-life considerations. One method can serve as a transition to another method as the patient’s status changes.

Bolus

The feeding modality of choice when patients are clinically stable with a functional stomach is the syringe bolus method (see Figure 14-4). Syringe bolus feedings administered in 5 to 20 minutes are more convenient and less expensive than pump or gravity bolus feedings, and should be encouraged when tolerated. A 60-mL syringe is used to infuse the formula. If bloating or abdominal discomfort develops, the patient is encouraged to wait 10 to 15 minutes before proceeding with the remainder of formula allocated for that feeding. Patients with normal gastric function can usually tolerate 500 mL of formula at each feeding. People receiving home EN may tolerate greater volumes of formula over time. Three or four bolus feedings per day can provide the daily nutritional requirements for most patients. Feedings should be at room temperature because cold formula can cause gastric discomfort.

Intermittent Drip

Quality-of-life issues are often the reason for the initiation of intermittent drip feeding regimens, which allow mobile patients more free time and autonomy compared with continuous drip infusions. These feedings can be given by pump or gravity drip. Gravity feeding is done by pouring formula into a feeding bag with a roller clamp. The clamp is adjusted to the desired drips per minute. A schedule is based on four to six feedings per day administered for 20 to 60 minutes. Formula administration is initiated at 100 to 150 mL per feeding and increased incrementally as tolerated. Success with this method of feeding depends largely on the degree of mobility, alertness, and motivation of the patient to tolerate the regimen.

Continuous Drip

Continuous drip infusion of formula requires a pump. This method is appropriate for patients who do not tolerate large-volume infusions during a given feeding such as those occurring with bolus or intermittent methods. Patients with compromised gastrointestinal function because of disease, surgery, cancer therapy, or other physiologic impediments are candidates for continuous drip infusion. Patients that are being fed into the small intestine should be fed only by continuous drip infusion. The feeding rate goal, in milliliters per hour, is set by dividing the total daily volume by the number of hours per day of administration (usually 18 to 24 hours). Feeding is started at one quarter to one half of the goal rate and is advanced every 8 to 12 hours to the final volume.

Formulas can generally be started at full strength; however, high osmolality formulas may require more time to achieve tolerance and should be advanced conservatively. Dilution of formulas is not necessary and can lead to underfeeding.

Modern enteral pumps are small and easy to handle. Many pumps are battery operated for up to 8 hours in addition to being electrically powered, allowing flexibility and mobility for the patient. Most pumps have a complete delivery system available, including bags and tubing compatible with proper pump operation.

Monitoring and Evaluation

Abdominal leakage of gastric contents from a gastrostomy site can cause skin erosion and skin breakdown, leading to infection and peritonitis; however, fewer than 10% of patients experience serious complications. Other complications can be prevented or managed with careful patient monitoring. Box 14-3 provides a comprehensive list of complications associated with EN.

Aspiration is a concern for patients receiving EN and is also a controversial topic because many experts believe the issue is not aspiration of formula into the airway, but aspiration of throat contents and saliva. To minimize the risk of aspiration, patients should be positioned with their heads and shoulders above their chests during and immediately after feeding (ASPEN, 2010, Bankhead et al., 2009).

There is confusion in the literature as to the efficacy of checking gastric residuals, because procedures are not standardized and the practice of checking residuals does not protect the patient from aspiration. Stable patients, especially those who have been fed by tube for long periods, do not need residuals checked regularly. Also, it is difficult to aspirate the stomach contents, and the residuals may contain more secretions and gastric fluids than formula. In critically ill patients the best methods for decreasing the risk of aspiration are elevating the head of the bed, continuous subglottic suctioning, and oral decontamination (American Dietetic Association, 2010; Bankhead et al., 2009).

Diarrhea is a common complication, often from colonic bacterial overgrowth, antibiotic therapy, and gastrointestinal motility disorders associated with acute and critical illness. Hyperosmolar medications such as magnesium-containing antacids, sorbitol-containing elixirs, and electrolyte supplements can also contribute to diarrhea. Adjustment of medications or administration methods can frequently correct the diarrhea. The addition of FOS, pectin, and other fibers, bulking agents, and antidiarrheal medications can also be beneficial. Use of a predigested formula can also be considered when managing diarrhea in a tube-fed patient.

Among stable patients receiving EN, constipation can become a problem. Fiber-containing formulas or stool-bulking medication may be helpful, and adequate fluid must be provided. Again, medications should be reviewed. Narcotic pain relievers have the side effect of slowing GIT activity. Gastrointestinal motility should be assessed because diarrhea can coexist with constipation, usually when there is also a fecal impaction.

Monitoring for Tolerance and Nutritional Intake Goals

Monitoring the patient’s actual intake and tolerance is necessary to ensure that nutrition goals are achieved and maintained. Monitoring of metabolic and gastrointestinal tolerance, hydration status, and nutritional status is extremely important (Box 14-4). It is important to avoid use of blue dye to evaluate the contents of aspirate; the risks outweigh any perceived benefit (American Dietetic Association, 2010). Another concern is gastroparesis or high gastric residuals. In these cases, a promotility drug may be beneficial to increase gastrointestinal transit, improve EN delivery, and improve feeding tolerance (American Dietetic Association, 2010). The development and use of practice guidelines, institutional protocols, and standardized ordering procedures are helpful to ensure optimal, safe monitoring of EN (ASPEN, 2010).

It is important to monitor actual intake compared with prescribed intake. During routine patient care, feeding time is commonly lost from the prescribed feeding schedule as a result of (1) a dislodged tube, (2) gastrointestinal intolerance, (3) medical procedures requiring discontinuation of feeding, and (4) difficulties with the feeding tube position. When feedings must be turned off for long periods of time the result can be inadequate nutrition and adjustment in the tube feeding regimen should be made. For example, if tube feedings are being turned off for 2 hours every afternoon for physical therapy, the rate on the feeding should be turned up and the length of feeding time decreased to accommodate the therapy schedule.

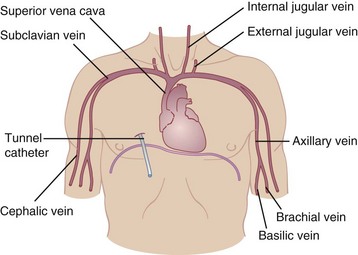

Parenteral Nutrition

PN provides nutrients directly into the bloodstream intravenously. PN is indicated when the patient requires nutrition support but is unable or unwilling to take adequate nutrients orally or enterally. PN may be used as an adjunct to oral or EN to meet nutrient needs. Alternatively, PN may be the sole source of nutrition during recovery from illness or injury, or may be a life-sustaining therapy for patients who have lost the function of their intestine for nutrient absorption. The practitioner must choose between central and peripheral access. Central access refers to catheter tip placement in a large, high-blood-flow vein such as the superior vena cava; this is central parenteral nutrition (CPN). Peripheral parenteral nutrition (PPN) refers to catheter tip placement in a small vein, typically in the hand or forearm.

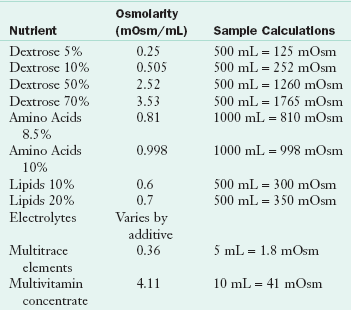

The osmolarity of the PN solution dictates the location of the catheter; central catheter placement allows for the higher caloric PN formulation and therefore greater osmolarity (Table 14-2). The use of PPN is limited in that it is short-term therapy with a minimum effect on nutritional status; the type and amount of fluids that can be provided peripherally do not fully meet nutrition requirements. Volume-sensitive patients such as those with cardiopulmonary, renal, or hepatic failure are not good candidates for PPN. PPN may be appropriate when used as a supplemental feeding or in transition to enteral or oral feeding, or as a temporary method to begin feeding when central access has not been initiated. Calculation of the osmolarity of a parenteral solution is important to ensure venous tolerance (Kumpf et al., 2005). Osmolarity, or mOsm/mL is used to calculate IV fluids rather than osmolality which is used for body fluids.

TABLE 14-2

Osmolarity of Nutrients in PN Solutions

Data from RxKinetics: Calculating osmolarity of an IV admixture. Accessed 29 May 2010 from http://www.rxkinetics.com/iv_osmolarity.html.

Access

Nutrient solutions not exceeding osmolalities of 800 to 900 mOsm/kg of solvent can be infused through a routine peripheral intravenous angiocatheter placed in a vein in good condition (Matarese and Steiger, 2006). Protocols for dressing changes and rotation of the site are used to prevent thrombophlebitis, the principal complication of peripheral catheters.

A beneficial development in peripheral catheter technology is the extended dwell catheter. These catheters are sometimes called midline or midclavicular catheters, depending on their position. Extended dwell catheters require a vein large enough to advance the catheter 5 to 7 inches into the vein. These catheters can remain at the original site for 3 to 6 weeks and make PPN a more feasible option in patients with veins large enough to tolerate the catheter (Krzywda et al., 2005).

Short-Term Central Access

Catheters used for CPN ideally consist of a single lumen. If central access is needed for other reasons, such as hemodynamic monitoring, drawing blood samples, or giving medications, multiple-lumen catheters are available. To reduce the risk of infection, the catheter lumen used to infuse CPN should be reserved for that purpose only. Catheters are most commonly inserted into the subclavian vein and advanced until the catheter tip is in the superior vena cava, using strict aseptic technique. Alternatively, an internal or external jugular vein catheter can be used with the same catheter tip placement. However, the motion of the neck makes this site much more difficult for maintaining the sterility of a dressing. Radiologic verification of the tip site is necessary before infusion of nutrients can begin. Strict infection control protocols should be used for catheter placement and maintenance (Krzywda et al., 2005). Figure 14-5 shows alternative venous access sites for CPN; femoral placement is also possible.

A peripherally inserted central catheter (PICC or PIC) may be used for short- or moderate-term infusion in the hospital or in the home. This catheter is inserted into a vein in the antecubital area of the arm and threaded into the subclavian vein with the catheter tip placed in the superior vena cava. Trained nonphysicians can insert a PICC, whereas placement of a tunneled catheter is a surgical procedure (Krzywda et al., 2005). All catheters must have radiologic confirmation of the placement of the catheter tip prior to initiating any infusion.

Long-Term Central Access

A commonly used long-term catheter is a “tunneled” catheter. This single- or multiple-lumen catheter is placed in the cephalic, subclavian, or internal jugular vein and fed into the superior vena cava. A subcutaneous tunnel is created so that the catheter exits the skin several inches from its venous entry site. This allows the patient to care for the catheter more easily as is necessary for long-term infusion. Another type of long-term catheter is a surgically implanted port under the skin where the catheter would normally exit at the end of the subcutaneous tunnel. A special needle must access the entrance port. Ports can be single or double; an individual port is equivalent to a lumen. Both tunneled catheters and PICCs can be used for extended therapy in the hospital or for home infusion therapy. Care of long-term catheters requires specialized handling and extensive patient education.

Parenteral Solutions

Commercially available standard PN solutions are composed of all the essential amino acids and only some of the nonessential crystalline amino acids. Nonessential nitrogen is provided principally by the amino acids alanine and glycine, usually without aspartate, glutamate, cysteine, and taurine. Specialized solutions with adjusted amino acid content that contain taurine are available for infants, for whom taurine is thought to be conditionally essential.

The concentration of amino acids in PN solutions ranges from 3% to 20% by volume. Thus a 10% solution of amino acids supplies 100 g of protein per liter (1000 mL). The percentage of a solution is usually expressed at its final concentration after dilution with other nutrient solutions. The caloric content of amino acid solutions is approximately 4 kcal/g of protein provided. Approximately 15% to 20% of total energy intake should come from protein (Kumpf et al., 2005).

Specialized solutions for patients with renal or liver disease are available, but are used infrequently because of their expense and the lack of conclusive research data supporting their efficacy. Recently, the amino acid glutamine has been suggested as an additive for patients requiring PN in the critical care setting (Martindale, 2009). Glutamine is not yet readily available in a commercial form and is therefore not routinely added to PN formulations.

Carbohydrates

Carbohydrates are supplied as dextrose monohydrate in concentrations ranging from 5% to 70% by volume. The dextrose monohydrate yields 3.4 calories per gram. As with amino acids, a 10% solution yields 100 g of carbohydrates per liter of solution. The use of carbohydrates (100 g daily for a 70-kg person) ensures that protein is not catabolized for energy during conditions of normal metabolism.

Maximum rates of carbohydrate administration should not exceed 5 to 6 mg/kg/min in critically ill patients. When PN solutions provide 15% to 20% of total calories as protein, 20% to 30% of total calories as lipid, and the balance from carbohydrate (dextrose), infusion of dextrose should not exceed this amount. Excessive administration can lead to hyperglycemia, hepatic abnormalities, or increased ventilatory drive (see Chapter 35).

Lipid

Lipid emulsions, available in 10%, 20%, and 30% concentrations, are composed of aqueous suspensions of soybean or safflower oil, with egg yolk phospholipid as the emulsifier. Lipid emulsions should not be used when a patient has an egg allergy. The three-carbon molecule, glycerol, which is water soluble, is added to the emulsion. Glycerol is oxidized and yields 4.3 kcal/g.

Dietitians may be asked to calculate what the patient is receiving. A 10% emulsion provides 1.1 kcal/mL, a 20% emulsion provides 2 kcal/mL, and 30% emulsion provides 2.9 kcal/mL. Providing 20% to 30% of total calories as lipid emulsion should result in a daily dosage of approximately 1 g of fat per kilogram of body weight. Administration should not exceed 2.5 g of lipid emulsion per kilogram of body weight per day. In the hospital lipid is infused during 24 hours when mixed with the dextrose and amino acids. Alternatively, lipids can be provided separately by infusion via an infusion pump. For adult patients receiving PN at home, the PN will most often be infused during 10-12 hours per day with the lipid as part of the PN solution.

Approximately 10% of calories per day from fat emulsions provide the 2% to 4% of calories from linoleic acid required to prevent EFAD. Soybean and safflower oils are rich sources of linoleic acid, providing approximately 40%. Linoleic acid alters prostaglandin metabolism, thereby producing both proinflammatory and immunosuppressive effects, particularly at high doses and at faster infusion rates (Mizock and DeMichele, 2004). Therefore it is important not to use high doses of linoleic acid in the solutions.

Electrolytes, Vitamins, Trace Elements

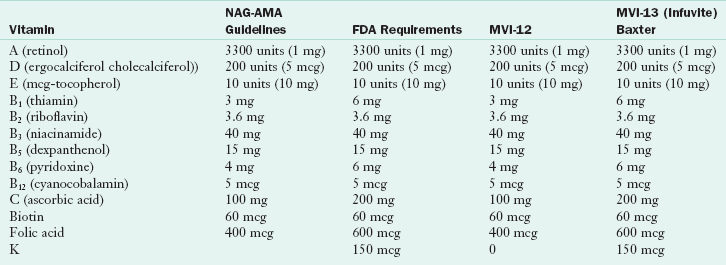

General guidelines for daily requirements for electrolytes are given in Table 14-3, for vitamins in Table 14-4, and for trace elements in Table 14-5. Parenteral solutions also represent a significant portion of total daily fluid and electrolyte intake. Once a solution is prescribed and initiated, adjustments for proper fluid and electrolyte balance may be necessary, depending on the stability of the patient. The choice of the salt form of electrolytes (e.g., chloride, acetate) affects acid-base balance.

TABLE 14-3

Daily Electrolyte Requirements During Total Parenteral Nutrition—Adults

| Electrolyte | Standard Intake/Day |

| Calcium | 10-15 mEq |

| Magnesium | 8-20 mEq |

| Phosphate | 20-40 mmol |

| Sodium | 1-2 mEq/kg + replacement |

| Potassium | 1-2 mEq/kg |

| Acetate | As needed to maintain acid-base balance |

| Chloride | As needed to maintain acid-base balance |

From McClave SA et al: Guidelines for the provision and assessment of nutrition support therapy in the adult critically ill patient, JPEN J Parenter Enteral Nutr 33:277, 2009.

TABLE 14-4

Adult Parenteral Multivitamins: Comparison of Guidelines and Products

AMA, American Medical Association; FDA, U.S. Food and Drug Administration; MVI-12 and MVI-13, multivitamin supplements; NAG, National Advisory Group.

From Fed Reg 66(77), 2000.

TABLE 14-5

Daily Trace Element Supplementation for Adult Parenteral Formulations

| Trace Element | Intake |

| Chromium | 10-15 mcg |

| Copper | 0.3-0.5 mg |

| Manganese | 60-100 mcg |

| Zinc | 2.5-5.0 mg |

| Selenium | 20-60 mcg |

Because parenterally administered vitamins and trace elements do not go through the digestive and absorptive processes, these recommendations are lower than the DRIs. Recently a review of the micronutrient needs of patients receiving PN, especially those receiving long-term home parenteral nutrition (HPN), has raised awareness of the need for careful review of patient requirements compared with the content of current trace element formulations. Monitoring of manganese and chromium status is recommended for patients receiving PN for longer than 6 months (Buchman, 2009). Iron is not normally part of parenteral infusions because it is not compatible with lipids and may enhance certain bacterial growth. Additionally, care must be taken to ensure that a patient can tolerate the separate iron infusion. When patients receive iron on an outpatient basis, the first dose should be done in a controlled setting (such as an outpatient infusion suite) to observe for any reactions that the patient might experience.

Fluid

Fluid needs for PN or EN are calculated similarly. Maximum volumes of CPN rarely exceed 3 L, with typical prescriptions of 1.5 to 3 L daily. In critically ill patients volumes of prescribed CPN should be closely coordinated with their overall care plan. The administration of other medical therapies requiring fluid administration, such as intravenous medications and blood products, necessitates careful monitoring. Patients with cardiopulmonary, renal, and hepatic failure are especially sensitive to fluid administration. For HPN, higher volumes may be best provided in separate infusions. For example, if additional fluid is required as a result of high output by the patient, then a liter bag of intravenous fluid containing minimal electrolytes may be infused during a short time during the day if the PN is infused over night. See Appendix 32 on calculating PN prescriptions.

Compounding Methods

PN prescriptions have historically required preparation or compounding by competent pharmacy personnel under laminar airflow hoods using aseptic techniques. Hospitals may have their own compounding pharmacy or may purchase PN solutions that have been compounded outside the hospital in a central location, and then returned to the hospital for distribution to individual patients. A third method of providing PN solutions is to utilize multichamber bag technology whereby solutions are manufactured in a quality-controlled environment using good manufacturing processes. These PN solutions are standardized but are available in multiple formulas with varying amounts of dextrose and amino acids, making them suitable for CPN or PPN infusion. They contain conservative amounts of electrolytes or may be electrolyte free. These products have a shelf life of 2 years and do not need to be refrigerated unless the product covering has been opened to reveal the infusion bag (Figure 14-6). Institutions frequently use standardized solutions, which are compounded in batches, thus saving labor and lowering costs; however, flexibility for individualized compounding should be available when warranted (Kumpf et al., 2005).

FIGURE 14-6 Baxter Clinimix Compounding System. (Image provided by Baxter Healthcare Corporation. CLINIMIX is a trademark of Baxter International Inc.)

Prescriptions for PN are compounded in two general ways. One method compounds all components except the fat emulsion, which is infused separately. Solutions are usually mixed in one bag at a 1 : 1 dextrose-to-amino acid volume ratio. The second method combines the lipid emulsion with the dextrose and amino acid solution and is referred to as a total nutrient admixture or 3-in-1 solution. The PN Safe Practices Guidelines provide practitioners with information on many techniques and procedures that enhance safety and prevent mistakes in the preparation of PN (Seres, 2006).

A number of medications, including antibiotics, vasopressors, narcotics, diuretics, and many other commonly administered drugs, can be compounded with PN solutions. In practice this occurs infrequently because it requires specialized knowledge of physical compatibility or incompatibility of the solution contents. The most common drug additives are insulin for persistent hyperglycemia and histamine-2 antagonists to avoid gastroduodenal stress ulceration (Kumpf et al., 2005). One other consideration is that the PN usually is ordered 24 hours prior to its administration, and patient status may have changed.

Administration

The methods used to administer PN are addressed after the goal infusion rate, based on calculations, has been established. PN calculations and orders are inherently complex and protocols for ordering PN vary considerably among institutions. Nevertheless, general considerations as listed in Box 14-5 can be applied to almost any protocol.

Continuous Infusion

Parenteral solutions are usually initiated below the goal infusion rate via a volumetric pump and then increased incrementally over a 2- or 3-day period to attain the goal infusion rate. Some practitioners start PN based on the amount of dextrose, with initial prescriptions containing 100 to 200 g daily and advancing over a 2- or 3-day period to a final goal. With high dextrose concentrations, abrupt cessation of CPN should be avoided, particularly if the patient’s glucose tolerance is abnormal. If CPN is to be stopped, it is prudent to taper the rate of infusion in an unstable patient to prevent rebound hypoglycemia, low blood sugar levels resulting from abrupt cessation. For most stable patients this is not necessary.

Cyclic Infusion

Individuals who require PN at home will benefit from a cyclic infusion; this entails infusion of PN for 8- to 12-hour periods, usually at night. This allows the person to have a free period of 12 to 16 hours each day, which may improve quality of life. The goal cycle for infusion time is established incrementally when a higher rate of infusion or a more concentrated solution is required. Cycled infusions should not be attempted if glucose intolerance or fluid tolerance is a problem. The pumps used for home infusion of PN are small and convenient, allowing mobility during daytime infusions. Administration time may be decreased because of patient ambulation and bathing, tests or other treatments, intravenous administration of medications, or other therapies.

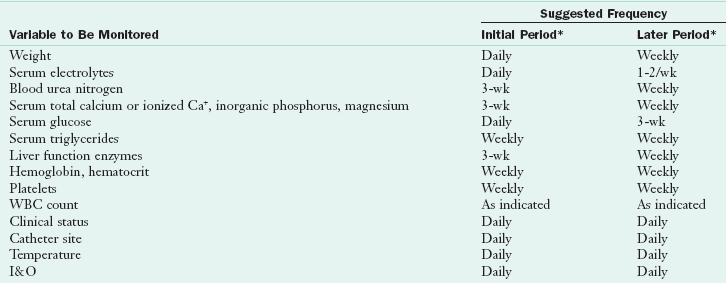

Monitoring and Evaluation

As with enteral feeding, routine monitoring of PN is necessary more frequently for the patient receiving PN in the hospital. For patients receiving HPN, initial monitoring is done on a weekly basis or less frequently as the patient becomes more stable on PN. Monitoring is done not only to evaluate response to therapy, but to ensure compliance with the treatment plan.

The primary complication associated with PN is infection (Box 14-6). Therefore strict adherence to protocols and monitoring for signs of infection such as chills, fever, tachycardia, sudden hyperglycemia, or elevated white blood cell count are necessary. Monitoring of metabolic tolerance is also critical. Electrolytes, acid-base balance, glucose tolerance, renal function, and cardiopulmonary and hemodynamic stability (maintenance of adequate blood pressure) can be affected by PN and should be monitored carefully. Table 14-6 lists parameters that should be monitored routinely.

TABLE 14-6

Inpatient Parenteral Nutrition Monitoring

I&O, Intake and output; WBC, white blood cell.

I&O refers to all fluids going into the patient: oral, intravenous, medication; and all fluid coming out: urine, surgical drains, exudates.

*Initial period is that period in which a full glucose intake is being achieved. Later period implies that the patient had achieved a steady metabolic state. In the presence of metabolic instability, the more intensive monitoring outlined under initial period should be followed.

McClave SA et al: Guidelines for the provision and assessment of nutrition support therapy in the adult critically ill patient, JPEN J Parenter Enteral Nutr 33:277, 2009.

The CPN catheter site is a potential source for introduction of microorganisms into a major vein. Protocols to prevent infection vary and should follow Centers for Disease Control Prevention guidelines (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention [CDC] and O’Grady, 2002). Catheter care and prevention of catheter-related bloodstream infections are of utmost importance in both the hospital and alternate settings. These infections are not only costly but may be life-threatening. Catheter care is dictated by the site of the catheter and the setting in which the patient receives care.

Refeeding Syndrome

Patients who require enteral or PN therapies may have been eating poorly prior to initiating therapy because of the disease process and may be moderately to severely malnourished. Aggressive administration of nutrition, particularly via the intravenous route, can precipitate refeeding syndrome with severe, potentially lethal electrolyte fluctuations involving metabolic, hemodynamic, and neuromuscular problems. Refeeding syndrome occurs when energy substrates, particularly carbohydrate, are introduced into the plasma of anabolic patients (Parrish, 2009).

Proliferation of new tissue requires increased amounts of glucose, potassium, phosphorus, magnesium, and other nutrients essential for tissue growth. If intracellular electrolytes are not supplied in sufficient quantity to keep up with tissue growth, low serum levels of potassium, phosphorus, and magnesium develop. Low levels of these electrolytes are the hallmark of refeeding syndrome, especially hypokalemia. Carbohydrate metabolism by cells also causes a shift of electrolytes to the intracellular space as glucose moves into cells for oxidation. Rapid infusion of carbohydrate stimulates insulin release, which reduces salt and water excretion and increases the chance of cardiac and pulmonary complications from fluid overload.

Patients starting on PN who have received minimal nutrition for a significant period should be monitored closely for electrolyte fluctuation and fluid overload. A review of baseline laboratory values, including glucose, magnesium, potassium, and phosphorus should be completed and any abnormalities corrected prior to initiating nutrition support, particularly PN. Conservative amounts of carbohydrate and adequate amounts of intracellular electrolytes should be provided. The initial PN formulation should usually contain 25% to 50% of goal dextrose concentration and be increased slowly to avoid the consequences of hypophosphatemia, hypokalemia, and hypomagnesemia. PN compatibilities must be assessed when very low levels of dextrose are provided with higher levels of amino acids and electrolytes. The syndrome also occurs in enterally fed patients, but less often because of the effects of the digestive process.

In managing the nutrition care process, refeeding syndrome is an undesirable outcome that requires monitoring and evaluation. Most often, the nutrition diagnosis may be “excessive carbohydrate intake” or “excessive infusion from enteral or parenteral nutrition” in the undernourished patient. Thus, in the early phase of refeeding, nutrient prescriptions should be moderate in carbohydrate and supplemented with phosphorus, potassium, and magnesium (Kraft et al., 2005).

Transitional Feeding

All nutrition support care plans strive to use the GIT when possible, either with EN or by a total or partial return to oral intake. Therefore patient care plans frequently involve transitional feeding, moving from one type of feeding to another, with several feeding methods used simultaneously while continuously administering estimated nutrient requirements. This requires careful monitoring of patient tolerance and quantification of intake from parenteral, enteral, and oral routes. Most experts advise that initial oral diets be low in simple carbohydrates and fat, as well as lactose free. These provisions make digestion easier and minimize the possibility of osmotic diarrhea. Attention to individual tolerance and food preferences also helps maximize intake.

Parenteral to Enteral Feeding

To begin the transition from PN to EN, introduce a minimal amount of enteral feeding at a low rate of 30 to 40 mL/hr to establish gastrointestinal tolerance. When there is severe gastrointestinal compromise, predigested formula to initiate enteral feedings may be better tolerated. Once formula has been given during a period of hours, the parenteral rate can be decreased to keep the nutrient levels at the same prescribed amount. As the enteral rate is increased by 25 to 30 mL/hr increments every 8 to 24 hours, the parenteral prescription is reduced accordingly. Once the patient is tolerating about 75% of nutrient needs by the enteral route, the PN solution can be discontinued. This process ideally takes 2 to 3 days; however, it may become more complicated, depending on the degree of gastrointestinal function. At times the weaning process may not be practical, and PN can be stopped sooner, depending on overall treatment decisions and likelihood for tolerance of enteral feeding.

Parenteral to Oral Feeding

The transition from parenteral to oral feeding is ideally accomplished by monitoring oral intake and concomitantly decreasing the PN to maintain a stable nutrient intake. Approximately 75% of nutrient needs should be met consistently by oral intake before the PN is discontinued. The process is less predictable than the transition to enteral feeding. Variations include the patient’s appetite, motivation, and general well being. It is important to continue monitoring the patient for adequate oral intake once PN has been stopped and to initiate alternate nutrition support if necessary. Generally patients are transitioned from clear liquids to a diet that is low in fiber and fat and is lactose free. It takes several days for the GIT to regain function; during that time, the diet should be composed of easily digested foods.

Special nutrient needs may be employed, especially when transitioning a patient with gastrointestinal disorders such as short bowel syndrome. Specialized nutrients, optimized drug therapy, and nutrition counseling should be comprehensive to improve outcome. Some PN patients may not be able to fully discontinue PN, but may be able to use PN less than 7 days per week, necessitating careful attention to nutrient intake. A skilled registered dietitian (RD) can coordinate diet and PN needs for this type of patient (Matarese and Steiger, 2006).

Enteral to Oral Feeding

A stepwise decrease is also used to transition from EN to oral feeding. It is effective to move from continuous feeding to a 12- and then an 8-hour formula administration cycle during the night; this reestablishes hunger and satiety cues for oral intake during daytime. In practice, oral diets are often tried after inadvertent or deliberate removal of a nasoenteric tube. This type of interrupted transition should be monitored closely for adequate oral intake. Patients receiving EN who desire to eat and for whom it is not contraindicated can be encouraged to do so. A transition from liquids to easy-to-digest foods may be necessary during a period of days. Patients who cannot meet their needs by the oral route can be maintained by a combination of EN and oral intake.

Oral Supplements

The most common types of oral supplements are commercial formulas meant primarily to augment the intake of solid foods. They often provide approximately 250 kcal/8-oz or 240-mL portion and approximately 8 to 14 g of intact protein. Some products have 360 or 500 or as much as 575 kcal in a can. There are different types of products for different disease states.

Fat sources are often long-chain triglycerides, although some supplements contain MCTs. More concentrated and thus more nutrient-dense formulas are also available. A variety of flavors, consistencies, and modifications of nutrients are appropriate for various disease states. Some oral supplements provide a nutritionally complete diet if taken in sufficient volume.

The form of carbohydrate is a key factor to patient acceptance and tolerance. Supplements with appreciable amounts of simple carbohydrate taste sweeter and have higher osmolalities, which may contribute to gastrointestinal intolerance. Individual taste preferences vary widely, and normal taste is altered by certain drug therapies, especially chemotherapy. Concentrated formulas or large volumes can contribute to taste fatigue and early satiety. Thus both oral dietary intake and the actual intake of prescribed supplements should be monitored.

Oral supplements that contain hydrolyzed protein and free amino acids such as those developed for patients with renal, liver, and malabsorptive diseases tend to be mildly to markedly unpalatable, and acceptance by the patient depends on motivation. Some of these formulas also lack sufficient vitamins and minerals and are not nutritionally complete.

Although commercially available supplements are most commonly used for convenience, modules of protein, carbohydrate, or fat or commonly available food items can produce highly palatable additions to a diet. As examples, liquid or powdered milk, yogurt, tofu, or protein powders can be used to enrich cereals, casseroles, soups, or milk shakes. Thickening agents are now used to add variety, texture, and aesthetics to pureed foods, which are used when swallowing ability is limited (see Chapter 41). Imagination and individual tailoring can increase oral intake, avoiding the necessity for more complex forms of nutrition support.

Nutrition Support In Long-Term And Home Care

Long-term care (LTC) generally refers to a skilled nursing facility. Health care provided in this environment focuses on quality of life, self-determination, and management of acute and chronic disease. Indications for EN and PN are generally the same for older patients as for younger adults, and varies according to the age, gender, and disease state of the individual. PN and EN are often provided to these facilities by offsite pharmacies that specialize in LTC. These providers may employ dietitians and specially trained nurses to assist the facilities with education and training on PEN.

Advance directives are legal documents that residents use to state their preferences about aspects of care, including those regarding the use of nutrition support. These directives may be written in any setting, including acute or home care, but are especially useful in LTC to guide interventions on behalf of long-term care residents when they are no longer able to make decisions.

Differentiation between the effects of advanced age versus malnutrition is an assessment challenge for dietitians working in long-term care (Raymond, 2006). This is an area of active research, as is the influence that nutrition support has on the quality of life among long-term care residents. Studies generally show that use of nutrition support in older adults is beneficial, especially when used in conjunction with physical activity. However, when there is a terminal illness or condition, starting nutrition support may have no advantage and may prolong suffering in some cases. It is prudent for dietitians to be involved in ethical decisions according to the policies of their institutions.

Home Care

Home enteral nutrition (HEN) or home parenteral nutrition (HPN) support usually entails the provision of nutrients or formulas, supplies, equipment, and professional clinical services. Resources and technology for safe and effective management of long-term enteral or parenteral therapy are widely available for the home-care setting. Although home nutrition support has been available for more than 20 years, few outcome data have been generated. Because mandatory reporting requirements do not exist in the United States for patients receiving home nutrition support, the exact number of patients receiving this support is unknown.

The elements needed to implement home nutrition successfully include identification of appropriate candidates and a feasible home environment with responsive caregivers, a choice of a suitable nutrition support regimen, training of the patient and family, and a plan for medical and nutritional follow-up by the physician as well as by the home infusion provider (Box 14-7). These objectives are best achieved through coordinated efforts of an interdisciplinary team (see Clinical Insight: Home Tube Feeding—Key Considerations).

Patients receiving HEN may receive supplies only, or formula and supplies with or without clinical oversight by the provider. Many enteral patients receive services from a durable medical equipment (DME) provider that may or may not provide clinical services. A home infusion provider provides intravenous therapies, including home PN, intravenous antibiotics, and other therapies. Home nursing agencies may be associated with a DME company or a home infusion agency to provide nursing services to home EN or PN patients. Often the patient’s reimbursement source for home therapy plays a major role in determining the type of home infusion provider. In fact, reimbursement is a key component of a patient’s ability to receive home therapy of any kind and should be evaluated early in the care plan so that appropriate decisions can be made prior to discharge or initiating a therapy (Wojtylak, 2007).

Companies that provide home infusion services for EN or PN may be private or affiliated with acute care facilities. Criteria for selecting a home-care company to provide nutrition support should be based on the company’s ability to provide ongoing monitoring, patient education, and coordination of care. When a patient is receiving home EN or PN, it is important to determine if the provider has an RD on staff or access to the services of a RD. The RD is uniquely qualified not only to provide oversight and monitoring for the patient while receiving EN or PN, but also to provide the appropriate nutrition counseling and food suggestions when the patient transitions between therapies (Fuhrman, 2009).

Ethical Issues

Whether to provide or withhold nutrition support is often a central issue in “end-of-life” decision making. For patients who are terminally ill or in a persistent vegetative state, nutrition support can extend life to the point that issues of quality of life and the patient’s right to self-determination come into play. Often surrogate decision makers are involved in treatment decisions. The nutrition support practitioner has a responsibility to know whether documentation, such as a living will regarding the patient’s wishes for nutrition support, is in the medical record and whether counseling and support resources for legal and ethical aspects of patient care are available to the patient and his or her significant others.

American Dietetic Association—Evidence Analysis Library

http://www.adaevidencelibrary.com/topic.cfm?cat=3016

American Society for Parenteral and Enteral Nutrition

References

American Dietetic Association. Evidence analysis library. http://www.adaevidencelibrary.com/topic.cfm?cat=3016&library=EBG, 2010. [Accessed 29 May 2010 from].

American Society for Parenteral and Enteral Nutrition Board of Directors and American College of Critical Care Medicine. Nutrition guidelines for the provision and assessment of nutrition support therapy in the adult critically ill patient. JPEN J Parenter Enteral Nutr. 2010;33:3.

Bankhead, R, et al. ASPEN: enteral nutrition practice recommendations. JPEN J Parenter Enteral Nutr. 2009;33:122.

Buchman, AL, et al. Micronutrients in parenteral nutrition: too little or too much? The past, present, and recommendations for the future. Gastroenterology. 2009;137:1S.

Centers for Disease Control and PreventionO’Grady, NP, et al. Guidelines for the prevention of intravascular catheter-related infections. http://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/preview/mmwrhtml/rr5110a1.htm, 9 August 2002. [Accessed January 2006 from].

Charney, P, Malone, A. ADA pocket guide to enteral nutrition. Chicago: American Dietetic Association; 2006.

Fuhrman, MP, et al. Home care opportunities for food and nutrition professionals. JADA J Am Diet Assoc. 2009;109:1092.

Gottschlich, MM. Adult enteral nutrition: formulas and supplements. In: Buchman A, ed. Clinical nutrition in gastrointestinal disease. Thoroughfare, N.J.: Slack Inc, 2006.

Joint Commission on Accreditation of Healthcare Organizations. Sentinel Event Policy and Procedures. http://www.jointcommission.org/SentinelEvents/PolicyandProcedures/, July 2007. [Accessed 29 May 2010 from].

Kraft, MD, et al. Review of the refeeding syndrome. Nutr Clin Pract. 2005;20:625.

Krzywda, EA, et al. Parenteral nutrition access and infusion equipment. In Merritt R, ed.: The ASPEN nutrition support practice manual, ed 2, Silver Spring, MD: American Society for Parenteral and Enteral Nutrition, 2005.

Kumpf, VJ, et al. Parenteral nutrition formulations: preparation and ordering. In Merritt R, ed.: The ASPEN Nutrition support practice manual, ed 2, Silver Spring, MD: American Society for Parenteral and Enteral Nutrition, 2005.

Martindale, RD, et al. Guidelines for the provision and assessment of nutrition support therapy in the adult critically ill patient: Society of Critical Care Medicine and the American Society for Parenteral and Enteral Nutrition: executive summary. Crit Care Med. 2009;37:1757.

Matarese, LE, Steiger, E. Dietary and medical management of short bowel syndrome in adult patients. J Clin Gastroenterol Suppl. 2006;2:S85.

McClave, SA, et al. Guidelines for the provision and assessment of nutrition support therapy in the adult critically ill patient. JPEN J Parenter Enteral Nutr. 2009;33:277.

Metheny, NA, Meert, KL. Monitoring tube feeding placement. Nutr Clin Pract. 2004;19:487.

Mizock, BA, DeMichele, SJ. The acute respiratory distress syndrome: role of nutritional modulation of inflammation through dietary lipids. Nutr Clin Pract. 2004;19:563.

Nikolaidis, P, et al. Practice patterns of nonvascular interventional radiology procedures at academic centers in the United States? Acad Radiol. 2005;12:1475.

Parrish, CR. The refeeding syndrome in 2009: prevention is the key to treatment. J Support Oncol. 2009;7:20.

Raymond, J. Long-term care. In Lysen L, ed.: Quick reference to clinical dietetics, ed 2, Sudbury, Mass: Jones and Bartlett, 2006.

Seres, D, et al. Parenteral nutrition safe practices: results of the 2003 American Society for Parenteral and Enteral Nutrition survey. JPEN J Parenter Enteral Nutr. 2006;30:259.

Wojtylak, F, Hamilton. Reimbursement for home nutrition support. In: Ireton-Jones C, DeLegge M, eds. Handbook of home nutrition support. Sudbury, MA: Jones and Bartlett, 2007.