Chapter 20 Problems of pregnancy

Problems of pregnancy range from the mildly irritating to life-threatening conditions. Fortunately the life-threatening ones are rare because of improvements to the general health of the population, improved social circumstances and lower parity. However, as women delay childbearing (an increasing phenomenon in the developed world), they become more at risk of disorders associated with increasing age, such as malignancy, placenta praevia and problems associated with obesity. Regular antenatal checks beginning early in pregnancy are undoubtedly valuable. They help to prevent many complications and their ensuing problems, contribute to timely diagnosis and treatment, and enable women to form relationships with midwives, obstetricians and other health professionals who become involved with them in striving to achieve the best possible pregnancy outcomes.

The midwife’s role

The midwife’s role in relation to the problems associated with pregnancy is clear. At initial and subsequent encounters with the pregnant woman, it is essential that an accurate health history is obtained. General and specific physical examinations must be carried out and the results meticulously recorded. The examination and recordings give direction towards future referral and management. Where the midwife detects a deviation from the norm which is outside her current sphere of practice, she must refer the woman to a suitable qualified health professional to assist her (NMC 2004, p 16). The midwife will continue to offer the woman care and support throughout her pregnancy and beyond. The woman who develops problems during her pregnancy is no less in need of the midwife’s skilled attention; indeed, her condition and psychological state may be considerably improved by the midwife’s continued presence and support. It is also the midwife’s role in such a situation to ensure that the woman and her family understand the situation; are enabled to take part in decision-making; are protected from unnecessary fear and the midwife must ensure that all care from different health professionals is balanced and integrated – in short, the woman’s needs remain paramount throughout.

Abdominal pain in pregnancy

Abdominal pain is a common complaint in pregnancy. It is probably suffered by all women at some stage, and therefore presents a problem for the midwife of how to distinguish between the physiologically normal (e.g. mild indigestion or muscle stretching), the pathological but not dangerous (e.g. degeneration of a fibroid) and the dangerously pathological requiring immediate referral to the appropriate medical practitioner for urgent treatment (e.g. ectopic pregnancy or appendicitis).

The midwife should take a detailed history and perform a physical examination in order to reach a decision about whether to refer the woman. Treatment will depend on the cause (Box 20.1) and the maternal and fetal conditions.

Box 20.1 Causes of abdominal pain in pregnancy

Adapted from Mahomed 2006a.

Many of the pregnancy-specific causes of abdominal pain in pregnancy listed in Box 20.1 are dealt with in this and other chapters. For most of these conditions, abdominal pain is one of many symptoms and not necessarily the overriding one. However, an observant midwife may be crucial in procuring a safe pregnancy outcome for a woman presenting with abdominal pain.

Uterine fibroid degeneration

The problems experienced in early pregnancy, as outlined in Ch. 19, may continue throughout the pregnancy as the muscle fibres continue to become hypertrophic and the fibroid (myoma) enlarges. Some women with fibroids will experience acute pain, and sometimes nausea, vomiting and mild pyrexia most commonly at 20–22 weeks’ gestation (Mahomed 2006b) as fibroids situated within the myometrium may receive a diminished blood supply and, as the pregnancy progresses, there may be central core necrosis.

If the fibroid or fibroids were not diagnosed prior to pregnancy or in its early stages, diagnosis can be made at any stage by ultrasound, especially if a fibroid is seen where the pain is located. Often fibroids are easily palpable. The pain usually subsides within 4–7 days with adequate explanation to the woman, rest and analgesia. The pregnancy will usually progress to term. However, the pain is often recurrent, especially if more than one fibroid is present.

Occasionally, enlargement of the fibroid may impede the progress of labour. Rupture of the uterus at the affected site is a possibility that should always be considered when caring for the woman in labour.

Severe uterine torsion

As it grows during pregnancy, the uterus usually rotates to the right by no more than 40 °. On rare occasions, the uterus rotates by more than 90 ° and this may cause abdominal pain in the latter half of pregnancy. There is almost always a predisposing factor in such cases of acute torsion, the most common being fibroid, congenital malformation of the uterus, adnexal mass or a history of pelvic surgery (Mahomed 2006a).

The condition is usually managed conservatively by bed-rest, altering the maternal position to correct the torsion spontaneously. Analgesia may be required and if administered then the well-being of both mother and fetus should be monitored, as in rare severe cases, the mother can become shocked and the fetus deprived of oxygen. In such cases, a laparotomy will need to be performed as it is difficult to make a clear diagnosis without surgical evidence. Sometimes the torsion can be corrected manually. Delivery by caesarean section may be performed, either preceded or followed by manipulation of the uterus.

Pelvic girdle pain/symphysis pubis dysfunction

Symphysis pubis dysfunction (SPD), or pelvic girdle pain (PGP) as it is increasingly being called, is characterized by abnormal relaxation of the ligaments supporting the pubic joint (see Ch. 16). This is brought about by high levels of pregnancy hormones (particularly relaxin), biomechanical and genetic factors, and affects about 1 in 300 women (Ambrose & Repke 2006). The result of the relaxation is increased mobility of the joint; the pubic bones move up and down alternately as the woman walks. Strain on the sacroiliac joints may also occur, particularly in grande multiparae. The woman will complain of pain in the pubic region, and also of backache, at any time from the 28th week of pregnancy. It may start in the early postnatal period. Pain may be experienced in the abdominal muscles owing to an attempt to stabilize the bones by muscular action. On examination, the mother will complain of tenderness over the symphysis pubis. She may be extremely debilitated by the condition.

The midwife should note whether there is any history of pelvic fractures that may be aggravated by the pregnancy. Otherwise the midwife should explain to the mother the cause of this condition and advise her that as much rest as possible will be beneficial, especially as the pregnancy advances and abdominal distension increases. The woman should also aim to reduce non-essential weight-bearing activities and avoid straddle movements, which abduct the hips, e.g. squatting (Fry et al 1997). A supportive panty girdle or ‘tubigrip’ and comfortable shoes may also help when the woman is up and mobile. There is an increased risk of deep vein thrombosis if the woman’s mobility is reduced.

The midwife should notify the doctor if she suspects PGP and of the advice she has given. Advice and treatment from an obstetric physiotherapist will be of great help to the woman. In severe cases, bed-rest may be necessary on a firm mattress.

The ligaments should slowly return to normal following birth. However, the woman should be informed during pregnancy that the pain and discomfort may last for some time afterwards, to give her the opportunity to make appropriate arrangements. Postnatal physiotherapy will aid the strengthening and stabilization of the joint.

The Association of Chartered Physiotherapists (www.acpwh.co.uk) has produced a National Clinical Guideline for the care for women with SPD/PGP and its website: www.pelvicpartnership.org.uk provides further detailed information.

Antepartum haemorrhage

Bleeding from the genital tract in late pregnancy, after the 24th week of gestation and before the onset of labour, is referred to as an antepartum haemorrhage (APH). This may place the life of the mother and fetus at risk.

Effect on the fetus

Fetal mortality and morbidity are increased as a result of severe vaginal bleeding in pregnancy. Stillbirth or neonatal death may occur. Premature placental separation and consequent hypoxia may result in severe neurological damage in the baby (Manolitsas et al 1994).

Effect on the mother

If bleeding is severe, it may be accompanied by shock and disseminated intravascular coagulation (DIC) (see blood coagulation failure). The mother may die or be left with permanent ill health.

Types of APH

If bleeding from local lesions of the genital tract (incidental causes) is excluded, vaginal bleeding in late pregnancy is due to placental separation from placenta praevia or placental abruption (Table 20.1).

Table 20.1 Causes of bleeding in late pregnancy

| Cause | Incidence (%) |

|---|---|

| Placenta praevia | 31.0 |

| Placental abruption | 22.0 |

| ‘Unclassified bleeding’ | 47.0 |

| Marginal | 60.0 |

| Show | 20.0 |

| Cervicitis | 8.0 |

| Trauma | 5.0 |

| Vulvovaginal varicosities | 2.0 |

| Genital tumours | 0.5 |

| Genital infections | 0.5 |

| Haematuria | 0.5 |

| Vasa praevia | 0.5 |

| Other | 0.5 |

Adapted from Konje & Taylor (2006). Note: Konje & Taylor do not explain the lost 2.5% of ‘unclassified bleeding’.

Initial appraisal of a woman with APH

When a woman first loses blood from the vagina during pregnancy, she may call the midwife or present herself at hospital. She may fear that she is losing her baby; her partner may fear for the lives of both mother and child. The midwife’s role at this stage is to be supportive and ascertain as much detail as possible of the history and the circumstances surrounding the blood loss. This will assist both in assessing the woman’s condition and in making a diagnosis. However, the midwife will also be aware that APH is unpredictable and the woman’s condition can deteriorate rapidly at any time; she must therefore make a rapid decision about the urgency of need of a medical or paramedic presence, or both, often at the same time as observing and talking to the woman and her partner.

Sometimes bleeding that the woman had presumed to be from the vagina will in fact be from haemorrhoids. The midwife should consider this differential diagnosis and confirm or exclude this as soon as possible by careful questioning and examination.

Assessment of physical condition

Maternal condition

The first priority is the well-being of the mother. The midwife should look for any pallor or breathlessness, which may indicate shock. She should also assess the woman’s emotional state as she greets her and begins to ask for a history of events. She must generate the trust of both partners and remain calm.

Observation of pulse rate, respiratory rate, blood pressure and temperature will be made and recorded. The midwife must assess the amount of blood lost in order to ensure adequate fluid replacement. She will discuss with the couple how much has been lost earlier and should ask to see all soiled articles, retaining them for the doctor’s inspection.

A gentle abdominal examination is made, observing for signs that the woman is going into labour. On no account must any vaginal or rectal examination be made nor may an enema or suppository be given to a woman suffering from an APH, as these procedures could exacerbate the bleeding.

Factors to aid differential diagnosis

The location of the placenta is perhaps the most critical piece of information that will be needed in order to make a correct diagnosis; initially the midwife will not usually have this fact at her disposal. However, if she is able to elicit the following information from her observations and talking to the woman and her partner, then this will help her to arrive at a provisional diagnosis:

The relevance of the findings from these observations is further discussed in the context of the various causes of APH.

Supportive treatment

Alongside emotional support, the first need is for restoration of physical condition if this is being compromised. This will necessitate fluid replacement first with a plasma expander and subsequently with whole blood if necessary. If the mother is in severe pain, she should be offered strong analgesia to help counteract shock. If the midwife is in attendance at home she must decide how best to arrange transfer to hospital. She may summon the emergency obstetric unit where this exists, or alternatively the ambulance service. If she carries intravenous equipment, she can site an infusion. The obstetric registrar or paramedic will carry and infuse a plasma expander before transfer of the woman to hospital.

Placenta praevia

In this condition the placenta is partially or wholly implanted in the lower uterine segment on either the anterior or posterior wall.

The lower uterine segment grows and stretches progressively after the 12th week of pregnancy. In later weeks this may cause the placenta to separate and severe bleeding can occur. Bleeding is caused by shearing stress between the placental trophoblast and maternal venous blood sinuses. In some instances bleeding may be precipitated by sex. A separating placenta praevia places the mother and fetus at high risk and it constitutes an obstetric emergency. Medical assistance is vital if the lives of the mother and fetus are to be saved. Women with suspected placenta praevia should be transferred to a consultant obstetric unit.

Degrees of placenta praevia

Type 1 placenta praevia

The majority of the placenta is in the upper uterine segment (Figs. 20.1 and 20.5). Vaginal birth is possible. Blood loss is usually mild and the mother and fetus remain in good condition.

Type 2 placenta praevia

The placenta is partially located in the lower segment near the internal cervical os (marginal placenta praevia) (Figs. 20.2 and 20.6). Vaginal birth is possible, particularly if the placenta is anterior. Blood loss is usually moderate, although the conditions of the mother and fetus can vary. Fetal hypoxia is more likely to be present than maternal shock.

Type 3 placenta praevia

The placenta is located over the internal cervical os but not centrally (Figs. 20.3 and 20.7). Bleeding is likely to be severe, particularly when the lower segment stretches and the cervix begins to efface and dilate in late pregnancy. Vaginal birth is inappropriate because the placenta precedes the fetus.

Type 4 placenta praevia

The placenta is located centrally over the internal cervical os (Figs. 20.4 and 20.8) and torrential haemorrhage is very likely. Caesarean section is essential in order to save the lives of the mother and baby.

Indications of placenta praevia

Bleeding from the vagina is the only sign and it is painless. The uterus is not tender or tense. The presence of placenta praevia should be considered when the presenting part of the fetus is above the pelvis and/or the lie is unstable.

Localization of the placenta using ultrasonic scanning will confirm the existence of placenta praevia and establish its degree.

It is noteworthy that the degree of placenta praevia does not necessarily correspond to the amount of bleeding. A type 4 placenta praevia may never bleed before elective caesarean section in late pregnancy or the onset of spontaneous labour; conversely, some women with placenta praevia type 1 may experience relatively heavy bleeding from early in their pregnancy.

Assessing the mother’s condition

The amount of vaginal bleeding is variable; some mothers may have a history of a small repeated blood loss at intervals throughout pregnancy whereas others may have a sudden single episode of vaginal bleeding after the 20th week. However, severe haemorrhage occurs most frequently after the 34th week of pregnancy.

The haemorrhage may be mild, moderate or severe, is often not associated with any particular type of activity and may occur at rest. The colour of the blood is bright red, denoting fresh bleeding. The low placental location allows all of the lost blood to escape unimpeded and a retroplacental clot is not formed. For this reason, pain is not a feature of placenta praevia.

General examination

If the haemorrhage is slight the woman’s blood pressure, respiratory rate and pulse rate may be normal. In severe haemorrhage however, the blood pressure will be low and the pulse rate raised because of shock. The degree of shock correlates with the amount of blood lost from the vagina. Respirations are also rapid and the mother may have air hunger due to a reduction in the number of red blood cells in the circulation available for the uptake of oxygen. The mother’s colour will be pale and her skin cold and moist. With severe bleeding she may lose consciousness.

Abdominal examination

The midwife may find that the lie of the fetus is oblique or transverse and the fetal head may be high in a primigravida near term. The uterine consistency is normal and pain is not experienced by the mother when her abdomen is palpated.

The midwife must not attempt to do a vaginal examination as this could precipitate a torrential haemorrhage and worsen the situation.

An attempt should be made to quantify the amount of blood lost and all blood-soaked material used by the mother should be saved. Although this will not provide an accurate estimation of the quantity, it may be a helpful clue in assessing fluid replacement.

Assessing the fetal condition

The mother should be asked whether fetal activity has been normal. She may be aware of diminution or cessation of fetal movements, which may occur if fetal hypoxia is severe. Excessive fetal movement is sometimes said by midwives to be an indicator of fetal hypoxia although no good quality research evidence exists to support this.

The midwife should assess the fetal condition using an ultrasound fetal monitor such as a cardiotocograph (CTG) or handheld device. A Pinard fetal stethoscope may be used if these are not available. Fetal oxygenation depends upon the proportion of the placenta remaining attached. Fetal hypoxia is an emergency and medical assistance should be called urgently.

Management of placenta praevia

The management of placenta praevia depends on:

Conservative management

This is appropriate if bleeding is slight and the mother and fetus are well. The woman will be kept in hospital at rest until bleeding has stopped. A speculum examination will have ruled out incidental causes. Further bleeding is almost inevitable if the placenta encroaches into the lower segment; therefore it is usual to require the woman to remain in, or close to hospital for the rest of the pregnancy. Placental function is monitored by means of fetal kick charts and antenatal CTG. Ultrasound scans are repeated at intervals in order to observe the position of the placenta in relation to the cervical os as the lower segment grows. Fetal growth is also monitored as placental perfusion across the lower segment is less efficient than that in a fundally situated placenta, and intrauterine growth restriction may result.

A woman who is asked to stay in hospital for many weeks will have particular psychological and social needs. If she has other children, she will be anxious to know that good arrangements have been made for their care and they must be allowed to visit her frequently. She should be offered parent education and sometimes it may be possible to continue with a group she has been attending. Occupational therapy may help to alleviate the boredom often felt during long-stay hospital admission. A visit to the Special Care Baby Unit, perhaps with her family, and answering any questions she has may also help to prepare her for the possibility of pre-term birth.

A decision will be made with the woman about how and when the birth will be managed. If the woman does not have further severe bleeding, she can give birth when the fetus reaches maturity, vaginally if the placental location allows. Vaginal ultrasound allows for a more accurate estimation of placental site, on which the decision about mode of birth will be based.

Vaginal birth is usual with type 1 placenta praevia and possible with type 2, unless the placenta is situated immediately above the sacral promontory where it is vulnerable to pressure from an advancing fetal head and may impede descent. The degrees of placenta praevia that are amenable to vaginal birth may be termed minor. Labour is likely to be induced from 37 weeks’ gestation.

The midwife should be aware that, even if vaginal birth is achieved, there remains a danger of postpartum haemorrhage. This is because the placenta has been situated in the lower segment where there is paucity of oblique muscle fibres and therefore the living ligature action will be poor.

Active management

Severe vaginal bleeding will necessitate immediate delivery by caesarean section regardless of the location of the placenta. This should take place in a unit with facilities for the appropriate care of the newborn, especially if the baby will be pre-term.

Blood will be taken for a full blood count, cross-matching and clotting studies. An intravenous infusion will be in progress and several units of blood may need to be transfused quickly, with the woman’s consent. In an emergency, it may be necessary to give group O blood, if possible of the same Rhesus group as the mother.

An anaesthetist will be involved in the woman’s care, assessing her fluid requirements and output and helping her to make a decision about the use of regional or general anaesthesia (if she is able). During the assessment and preparation for theatre the mother will be extremely anxious and the midwife must comfort and encourage her, sharing information with her as much as possible. The partner will also need to be supported, whether he is in the operating theatre or waits outside.

Konje & Taylor (2006) describe the procedure of ‘double set up’ (p 1264), whereby a woman is examined in an operating theatre with full preparation to proceed to caesarean section if her condition worsens. This procedure can be useful where attempted placental localization by diagnostic ultrasound scanning proves inconclusive.

If the placenta is situated anteriorly in the uterus, this may complicate the surgical approach as it underlies the site of the normal incision. In major degrees of placenta praevia (types 3 and 4) caesarean section is required even if the fetus has died in utero. Such management aims to prevent torrential haemorrhage and possible maternal death.

Incidence

Placenta praevia occurring after 20 weeks’ gestation complicates 3–6 of every 1000 pregnancies (Lockwood & Funai 1999). It is more common in multigravidae, with an incidence of 1 in 90 births. (Placenta praevia rates rise in women with increasing age and increasing parity.) In primigravidae the incidence is 1 in 250 births. Its aetiology is unknown, but a raised incidence is also seen in women who smoke and those who have had a previous caesarean section. The recurrence rate for women who have had a previous placenta praevia is in the order of 4–8%.

Placental abruption

Premature separation of a normally situated placenta occurring after the 22nd week of pregnancy is referred to as placental abruption. The aetiology of this type of haemorrhage is not always clear, but it is often associated with severe pre-eclampsia, although not chronic hypertension (Ananth et al 1997). Abruption can follow a sudden reduction in uterine size, for instance when the membranes rupture or after the birth of a first twin, and rarely is a result of direct trauma to the abdomen, perhaps through a road traffic accident (Reis et al 2000), seat-belt injury (Eckford et al 1995) or deliberate violence. All of these may partially dislodge the placenta. Abu-Heija et al (1998) found in their large case–control study of 18256 women that high parity was a significant aetiological factor. Rasmussen et al (1999) found that caesarean section in the previous delivery increased the risk of placental abruption by 40%. There also appears to be a correlation between placental abruption and cigarette smoking (Andres 1996).

Interestingly, some researchers are starting to find links between pregnancy-induced hypertension, intrauterine growth restriction and preterm birth in that they may share a common early to mid-pregnancy aetiology of placental dysfunction, which may then manifest itself as placental abruption in the second half of pregnancy (Ananth & Wilcox 2001, Rasmussen et al 1999, 2000). This theory clearly needs to be tested in future research.

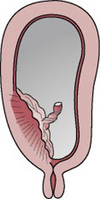

Placental abruption occurs in 0.49–1.8% of all pregnancies (Konje & Taylor 2006). Partial separation of the placenta causes bleeding from the maternal venous sinuses in the placental bed. Further bleeding continues to separate the placenta to a greater or lesser degree. If blood escapes from the placental site it separates the membranes from the uterine wall and drains through the vagina. Blood that is retained behind the placenta may be forced into the myometrium and it infiltrates between the muscle fibres of the uterus. This extravasation can cause marked damage and, if observed at operation, the uterus will appear bruised and oedematous. This is termed Couvelaire uterus or uterine apoplexy. There is no vaginal bleeding, but the mother will have all the signs and symptoms of hypovolaemic shock, caused by concealed bleeding into the muscle of the uterus. The concealed haemorrhage causes uterine enlargement and extreme pain. Concealed haemorrhage is said to account for 20–35% of abruptions (Konje & Taylor 2006).

A combination of these two situations where some of the blood drains via the vagina and some is retained behind the placenta is known as a mixed haemorrhage.

Types of placental abruption

The blood loss from a placental abruption may be defined as revealed, concealed or mixed haemorrhage, as described above. An alternative classification, based on the degree of separation and therefore related to the condition of the mother and baby, is of mild, moderate and severe haemorrhage. The midwife cannot rely on visible blood loss as a guide to the severity of the haemorrhage; on the contrary, the most severe haemorrhage is often that which is totally concealed.

Assessing the mother’s condition

There may be a history of pre-eclampsia. A recent history of headaches, nausea, vomiting, epigastric pain and visual disturbances may be a feature. Physical domestic violence should be considered by the midwife, which the woman may be too frightened to reveal (Bewley & Gibbs 2001). Road traffic accidents are a cause of trauma to the abdomen. External cephalic version injudiciously performed may also result in placental separation. The midwife should be aware of the possibility of placental separation after the birth of a first twin or loss of copious amounts of amniotic fluid.

The mildest degrees of placental abruption are relatively pain free, although the mother may experience a slight localized pain. The blood loss is revealed. More severe degrees are associated with abdominal pain and the midwife should enquire about the time of onset and whether the bleeding began simultaneously or later.

General examination

The woman is likely to be anxious, experiencing abdominal pain, and her skin will be pale and moist if she is shocked. On clinical examination, the mother may have obvious oedema of the face, fingers and pretibial area of the lower limbs attributable to pre-eclampsia.

The blood pressure and pulse should be taken immediately. A low blood pressure and raised pulse rate are signs of shock; if the mother has pregnancy-induced hypertension then the blood pressure may be within normal limits, having been raised prior to the haemorrhage. The respirations may be normal or rapid, and reduced oxygenation may lead to air hunger. The temperature will usually be normal but, as placental abruption may be caused by severe infection, it should be taken.

The amount of any visible blood loss should be estimated and its colour noted. Freshly lost blood is bright red; blood that has been retained in utero for any length of time changes to a brown colour.

Abdominal examination

Concealed haemorrhage may lead to uterine enlargement in excess of gestation. The uterus has a hard consistency and there is guarding on palpation of the abdomen. Palpation may be difficult and should not be attempted if the uterus is rigid and excessively painful. Fetal parts may not be palpable. In less severe cases palpation should be kept to a minimum in order to avoid further pain and damage. The nature and location of the pain should be established.

The fetal heart is unlikely to be heard with a fetal stethoscope if there has been any concealed haemorrhage; an ultrasound scanner, CTG or hand-held device should be used. If the haemorrhage is severe, fetal death is a common outcome.

Assessing the fetal condition

The woman may be aware of a cessation of fetal movements. A CTG recording will give more complete information about fetal condition, as will an ultrasound scan of the heart chambers. Failure to elicit heart sounds with a Pinard stethoscope is not confirmation of fetal death.

The midwife should take care how she conveys information about the fetus to the mother. If the heart is inaudible on first examination, she should explain that a fetal monitor is needed to establish the condition of her baby. It is rarely, if ever, appropriate to attempt to conceal fetal death from the mother.

Management

Any woman with a history suggestive of placental abruption needs urgent medical attention. She should be transferred speedily to a consultant obstetric unit, preferably by the emergency obstetric service. The midwife or a paramedic may site an intravenous cannula prior to transfer.

On arrival at the hospital the woman is admitted to the labour suite and the registrar or consultant obstetrician is informed. The midwife should offer the woman comfort and encouragement by attending to her physical and emotional needs, including her need for information.

Pain exacerbates shock and must be alleviated. As it may be extreme, a suitable analgesic would be morphine 15 mg or pethidine 100–150 mg. If the woman has had a narcotic drug prior to admission, the midwife must alert those in attendance to the fact that analgesia has been given.

The acute pain of concealed haemorrhage from placental abruption is due to the extravasation of blood between the muscle fibres of the uterus. This must be differentiated from the pain of uterine contraction due to the onset of labour and from subcapsular liver haemorrhage as a result of pre-eclampsia. The nature of the pain should be discussed because labour may supervene following placental abruption.

Shock may be due to hypovolaemia, to extravasation and consequent pain or to consumptive coagulopathy. The latter is due to tissue damage and the liberation of thromboplastins into the circulation with resulting disseminated intravascular coagulation (see below).

If blood is not available for immediate transfusion, hypovolaemia may be reduced by administering a suitable plasma expander. Letsky (1995) favours the use of Haemacel, which does not interfere with platelet function or subsequent blood grouping and cross-matching of blood. It also helps to improve renal function. However, this is only a temporary palliative and blood transfusion must follow as quickly as possible.

The woman should rest on her side in order to prevent vena caval occlusion and aortic compression by the gravid uterus. If shock becomes severe and medical assistance cannot be immediately obtained, or intravenous access secured, placing the woman flat with a wedge, or in a semirecumbent position with the legs only raised will help to sustain the circulation to her upper body for a short period. However, under no circumstances should the foot of the bed be elevated as this will cause pooling of blood in the vagina and is unlikely to reduce shock.

Observations

Once the maternal and fetal conditions have been assessed, decisions will be made about management. If resuscitation of the woman is required her condition should be stabilized before surgery is undertaken. Likewise, if the woman and fetus are not in imminent danger (or the fetus has died) some time will elapse before surgery is considered, and at this time it is crucial that the midwife maintains continual and accurate observations.

The mother’s blood pressure, respirations and pulse rate should be taken at frequent intervals, which will depend on the severity of her condition. If a pyrexia is present, the temperature may be recorded every 1–2 hrs; if the woman is not feverish, a 4-hourly recording is adequate. A central venous line is usually inserted in order to monitor the central venous pressure every 2 hrs, or more frequently, as necessary (see Ch. 33). If the haemorrhage is not severe enough to warrant intravenous infusion, a cannula will be sited in case the haemorrhage suddenly worsens.

Urinary output is accurately assessed by the insertion of an indwelling catheter. Oliguria or anuria indicates suppression of renal function, which may persist until a postpartum diuresis occurs. The urine should be tested for the presence of protein, which may also be linked to pre-eclampsia. Fluid intake must also be recorded accurately and fluid balance assessed with the aid of the central venous pressure recordings.

Fundal height and abdominal girth may be measured at regular intervals. An increase indicates continued bleeding behind the placenta. If the fetus is alive, the fetal heart rate should be monitored continuously with the aid of a CTG.

Any deterioration in the maternal or fetal conditions must be reported immediately to the obstetrician.

Investigations

As soon as practicable following admission a full blood count, cross-match and clotting studies should be obtained. Blood samples may be needed at intervals in order to monitor the progress of the condition. If pre-eclampsia is suspected the relevant blood tests should also be ordered. If the woman is Rhesus negative she should be offered anti-D immunoglobulin. If the Kleihauer is positive more anti-D will be required (Konje & Taylor 2006).

Management of different degrees of placental abruption

In mild separation of the placenta, the placental separation and the haemorrhage are slight. Mother and fetus are in a stable condition. There is no indication of maternal shock and the fetus is alive with normal heart sounds. The consistency of the uterus is normal and there is no tenderness on abdominal palpation. It may be difficult to differentiate this condition from placenta praevia and from an incidental cause of vaginal bleeding.

An ultrasound scan can determine the placental location and identify any degree of concealed bleeding. Fetal condition should be continually assessed while bleeding persists by frequent, if not continuous, monitoring of the fetal heart rate. Subsequently CTG should be carried out once or twice daily because any degree of abruption by definition involves partial separation of the placenta.

If the woman is not in labour and the gestation is <37 weeks, she may be cared for in an antenatal ward for a few days. She may then go home if there is no further bleeding and the placenta has been found to be in the upper uterine segment. Women who have passed the 37th week of pregnancy may be offered induction of labour, especially if there has been more than one episode of mild bleeding. Further heavy bleeding or evidence of fetal compromise may indicate that a caesarean section is necessary.

It should also be noted that if the mother is already severely anaemic then even an apparently mild abruption should cause concern.

Moderate separation of the placenta describes placental separation of about one-quarter. Some or all of the blood may escape from the vagina; some or all may be retained behind the placenta as a retroplacental clot or an extravasation into the uterine muscle. The mother will be shocked, with a raised pulse rate and a lowered blood pressure. There will be a degree of uterine tenderness and abdominal guarding. The fetus may be alive although hypoxic; intrauterine death is also a possibility.

The immediate aims of care are to reduce shock and to replace blood loss. Fluid replacement should be monitored with the aid of a central venous pressure line. The fetal condition should be assessed with continuous CTG if the fetus is alive, in which case immediate caesarean section may be indicated once the woman’s condition is stabilized.

If the fetus is in good condition or has already died, vaginal birth may be contemplated. Such management is advantageous because it enables the uterus to contract and control the bleeding. The spontaneous onset of labour frequently accompanies moderately severe placental abruption, but if it does not then amniotomy is usually sufficient to induce labour. Oxytocin may be used with great care if necessary. Birth is often quite sudden after a short labour. The use of drugs to attempt to stop labour is usually inappropriate.

Moderate separation of the placenta may on occasion deteriorate into a more serious degree of separation.

Severe separation of the placenta

This too is an acute obstetric emergency; at least two-thirds of the placenta has become detached and a life-threatening amount of blood is lost from the circulation. Most or all of the blood can be concealed behind the placenta. The woman will be severely shocked, perhaps to a degree far beyond what might be expected from the amount of visible blood loss. The blood pressure will be lowered; the reading may lie within the normal range owing to a preceding hypertension. The fetus will almost certainly be dead. The woman will have very severe abdominal pain with excruciating tenderness; the uterus has a board-like consistency.

Features associated with severe haemorrhage are coagulation defects, renal failure and pituitary failure. Treatment is the same as for moderate haemorrhage. Whole blood should be transfused rapidly and subsequent amounts calculated in accordance with the woman’s central venous pressure. Labour may begin spontaneously in advance of amniotomy and the midwife should be alert for signs of uterine contraction causing periodic intensifying of the abdominal pain. However, if bleeding continues or a compromised fetal heart rate is present, caesarean section may be required as soon as the woman’s condition has been adequately stabilized. The woman requires constant explanation and psychological support, despite the fact that, because of her shocked condition, she may not be fully conscious. Pain relief must also be considered. The woman’s partner will also be very concerned, and should not be forgotten in the rush to stabilize the woman’s condition.

Care of the baby

Preparation should be made for an asphyxiated baby. The paediatrician must be present at the birth to resuscitate the infant. The baby may require neonatal intensive care following birth and the staff of the neonatal unit will have been alerted. In addition to the insult of the haemorrhage, the baby may suffer from the effects of preterm birth and the stay in the neonatal unit may be prolonged. A baby who is born in good condition will of course require minimal resuscitation and will stay with the mother.

Psychological care

When a woman has a placental abruption she and her partner must be kept fully informed of what is happening at all times. The doctor should have a full and frank discussion with them about the events and the prognosis. The midwife should ensure that the partner is offered support and adequate explanation if the woman requires emergency surgery, or if her condition deteriorates suddenly. Whenever possible, he should continue to be present.

If the fetus is alive, a midwife or nurse from the neonatal unit should visit the couple in order to explain where the baby will be cared for after birth. The partner should be encouraged to visit the unit.

When the baby is born, if it is at all possible, the parents should be given a chance to see and handle their child before transfer to the neonatal unit. It is most helpful to have a photograph taken, which the mother can keep beside her, and the father should visit the baby at the earliest opportunity. Later the mother will be taken to see the baby, if necessary in her bed or in a wheelchair. As soon as she is able, she will be encouraged to participate in caring for her baby.

At a suitable time following her recovery, the mother must be invited to discuss the events and the prognosis for her baby. She may ask about the possibility of haemorrhage occurring in future pregnancies. There is some evidence that a previous abruption is a risk factor for abruption in the next pregnancy (Misra & Ananth 1999, Rasmussen et al 1997).

Complications

Blood coagulation failure

Normal blood coagulation

Haemostasis refers to the arrest of bleeding, its function being to prevent loss of blood from the blood vessels. It depends on the mechanism of coagulation. This is counterbalanced by fibrinolysis which ensures that the blood vessels are reopened in order to maintain the patency of the circulation.

Blood clotting occurs in three main stages:

Fibrin forms a network of long, sticky strands that entrap blood cells to establish a clot. The coagulated material contracts and exudes serum, which is plasma depleted of its clotting factors. This is the final part of a complex cascade of coagulation involving a large number of different clotting factors. These factors have been assigned Roman numerals (for instance ‘Factor IV’) in order of their discovery.

It is equally important for a healthy person to maintain the blood as a fluid in order that it can circulate freely. The coagulation mechanism is normally held at bay by the presence of heparin, which is produced in the liver.

Fibrinolysis is the breakdown of fibrin and occurs as a response to the presence of clotted blood. Unless fibrinolysis takes place, coagulation will continue. It is achieved by the activation of a series of enzymes culminating in the proteolytic enzyme plasmin. This breaks down the fibrin in the clots and produces fibrin degradation products (FDPs).

Disseminated intravascular coagulation

DIC is a situation of inappropriate coagulation within the blood vessels, which leads to the consumption of clotting factors. As a result clotting fails to occur at the bleeding site. DIC is rare when the fetus is alive and it usually starts to resolve when the baby is born (Enkin et al 2000).

Aetiology

DIC is never a primary disease – it always occurs as a response to another disease process. Such an event triggers widespread clotting with the formation of microthrombi throughout the circulation. Clotting factors are used up. The DIC triggers fibrinolysis and the production of FDPs. FDPs reduce the efficiency of normal clotting. A paradoxical feedback system is therefore set up, in which clotting is the primary problem, but haemorrhage is the predominant clinical finding.

When DIC occurs during or after birth, the reduced level of clotting factors and the presence of FDPs prevent normal haemostasis at the placental site. FDPs inhibit myometrial action and prevent the uterine muscle from constricting the blood vessels in the normal way. Torrential haemorrhage may be the outcome. Visible blood loss may be observed to remain uncoagulated for several minutes and even when clotting does occur, the clot is unstable.

Microthrombi may cause circulatory obstruction in the small blood vessels. The effects of this vary from cyanosis of fingers and toes to cerebrovascular accidents and failure of organs such as the liver and kidneys.

Events that trigger DIC

There are a number of obstetric events that may precipitate DIC:

Each of these conditions is dealt with in the appropriate chapter and only those aspects relating to DIC are discussed here.

Placental abruption

Owing to the damage of tissue at the placental site large quantities of thromboplastin are released into the circulation and may cause DIC. If the placenta is delivered as soon as possible after the abruption the risk of DIC is reduced. (However, vaginal birth where possible is often favoured over caesarean birth to reduce the risk of postpartum haemorrhage.)

Intrauterine fetal death

If a dead fetus is retained in utero for more than 3 or 4 weeks, then thromboplastins are released from the dead fetal tissues. These enter the maternal circulation and deplete clotting factors. If labour does not follow fetal death spontaneously, then it should be induced, with the woman’s consent. If fetal death is known to have occurred some time previously, clotting studies should be performed prior to induction of labour; if DIC is diagnosed the appropriate medical action should be taken.

Amniotic fluid embolism

If death does not occur from maternal collapse, DIC may develop. Thromboplastin in the amniotic fluid is responsible for setting off the cascade of clotting.

Intrauterine infection

The causes of this include septic abortion, hydatidiform mole, placenta accreta and endometrial infection before or after birth. DIC is caused by endotoxins entering the circulation and damaging the blood vessels. Therefore, as well as treating the DIC, the infection itself must be aggressively treated with antibiotics. It should be noted that if the woman develops haemolytic septicaemia, any blood administered may be destroyed by the bacteria in the bloodstream. The baby may need treatment following birth if the infection was antepartum. In postpartum infection, any retained products must be evacuated from the uterus.

Pre-eclampsia and eclampsia

The occurrence of DIC with severe pre-eclampsia is fully dealt with in Ch. 22.

Management

The aims of the management of DIC are summarized in Box 20.2.

The midwife should be aware of the conditions that may cause DIC. She should be alert for signs that clotting is abnormal and the assessment of the nature of the clot should be part of her routine observation during the third stage of labour. Oozing from a venepuncture site or bleeding from the mucous membrane of the mother’s mouth and nose must be noted and reported. As well as a full blood count and blood grouping, the doctor will carry out clotting studies and also measure the levels of platelets, fibrinogen and FDPs.

Treatment involves the replacement of blood cells and clotting factors in order to restore equilibrium. This is usually done by the administration of fresh frozen plasma and platelet concentrates. Banked red cells will be transfused subsequently. The use of fresh whole blood is not now common, partly because the screening processes undertaken in the modern transfusion service can take up to 24 hrs and the components are best given separately. In situations where the transfusion service is not so sophisticated, whole blood will be used.

Management is carried out by a team of obstetricians, anaesthetists, haematologists, midwives and other health professionals who must strive to work together harmoniously and effectively to achieve the best possible clinical outcomes.

Care by the midwife

DIC causes a frightening situation that demands speed both of recognition and of action. The midwife has to maintain her own calmness and clarity of thinking as well as helping the couple to deal with the situation in which they find themselves. Frequent and accurate observations must be maintained in order to monitor the woman’s condition. Blood pressure, respirations, pulse rate and temperature are recorded. The general condition is noted. Fluid balance is monitored with vigilance for any sign of renal failure.

The partner in particular is likely to be baffled by a sudden turn in events, when previously all seemed to be under control. The midwife must make sure that someone is giving him appropriate attention and he will need to be kept informed of what is happening and be excluded as little as possible. The carers need to be aware that he may find it impossible to absorb all that he is told and he may require repeated explanations. He may be the best person to help the woman to understand. The death of the mother is a real possibility.

Hepatic disorders and jaundice in pregnancy

Some liver disorders are specific to pregnant women, and some pre-existing or co-existing disorders may complicate the pregnancy (Box 20.3).

Causes of jaundice in pregnancy are listed in Box 20.4.

Box 20.4 Causes of jaundice in pregnancy

Note: Jaundice is not an inevitable symptom of liver disease in pregnancy.

Intrahepatic cholestasis of pregnancy

ICP is an idiopathic condition that begins in pregnancy, usually in the third trimester but occasionally as early as the first trimester. It resolves spontaneously following birth, but has up to a 9% recurrence rate in subsequent pregnancies (Nelson-Piercy 2002). The prevalence rate is seven cases per 1000 pregnancies in low-risk populations, which include Caucasians, but it is seen most frequently in Scandinavia, Chile, Poland, Australia and China and in women of South-Asian origin (Williamson & Girling 2006). Its cause is unknown although genetic, geographical and environmental factors would appear to be at play. Almes (1995), Davidson (1998) and Gaudet et al (2000) put forward a group of theories that suggest the biochemistry of bile metabolism is altered; this is possibly due to a genetic inherited hypersensitivity to oestrogens. A subsequent increase in serum bile acid levels then negatively affects placental blood flow, putting the fetus at risk. Disturbances in fetal steroid metabolism may also be implicated. It is not a life-threatening condition for the mother, but she is at increased risk of pre-term labour, fetal compromise and meconium staining and her stillbirth risk is increased by 15% unless there is active management of her pregnancy.

Affected women will first start to notice pruritus at night, and may complain of fatigue and insomnia because of this. Two weeks later, 50% of women affected will develop mild jaundice, which will persist until the birth. Fever, abdominal discomfort and nausea and vomiting are not uncommon symptoms. Women may notice that their urine is darker and stools are paler than usual.

If this condition is suspected, blood will be tested for an increase in bile acids, serum alkaline phosphatase, bilirubin and transaminases. Hepatic viral studies, an ultrasound scan of the hepatobiliary tract and an autoantibody screen (for primary biliary cirrhosis) are also indicated as of value in excluding differential diagnoses. The woman will be prescribed local antipruritic agents, for instance antihistamines, and advised to keep any sores caused by scratching clean. Drugs, such as ursodeoxycholic acid (UDCA), dexamethasone and cholestyramine have disappointing results in controlling symptoms (Williamson & Girling 2006) and there has been little follow-up of the babies to date. The woman may be prescribed Vitamin K 10 mg orally daily as her absorption will be poor, leading to prothrombinaemia, which will predispose her to obstetric haemorrhage.

Because of concern about the implications of this condition for the fetus, the resultant jaundice and the severity of the itching, this woman will require sensitive psychological care. Fetal well-being should be monitored, possibly by Doppler analysis of the umbilical artery blood flow, and elective delivery considered when the fetus is mature (usually at 35–38 weeks’ gestation) or earlier if the fetal condition appears to be compromised by the intrauterine environment.

The woman can be advised that her pruritus will resolve within 3–14 days after the birth. She should be carefully monitored if she uses oral contraception in the future. The pruritus is often so severe and distressing that many women who have suffered from this condition will avoid future pregnancy.

Further information and support is available at: www.ocsupport.org.uk

Acute fatty liver of pregnancy

AFLP is a rare condition of unknown aetiology (although fetal long-chain hydroxyacyl co-enzyme A dehydrogenase (LCHAD) deficiency has recently been implicated). It has an incidence in various studies of between 1 in 7000 and 1 in 13 000 pregnancies (Williamson & Girling 2006). It is frequently fatal for the mother and baby unless there is a speedy diagnosis and the correct treatment is given.

Typically, an obese woman will present with vomiting and a headache in her third trimester. She will quickly complain of malaise and severe abdominal pain, followed by jaundice and drowsiness. Fagan (2002) comments that over 50% of these women have symptoms of pre-eclampsia (hypertension and proteinuria), and so there is an inherent danger that the pre-eclampsia will mask the presentation of AFLP.

The condition is diagnosed by the clinical picture. The woman’s liver is tender but not enlarged, and an ultrasound or computerized tomography (CT) scan of the liver demonstrates fatty infiltration. Liver biopsy is contraindicated owing to the risk of coagulopathy. The liver enzymes are moderately raised and the woman will also quickly show signs of renal failure and will become hypoglycaemic.

Management will first involve correcting any coagulopathy by measures such as infusing fresh frozen plasma. The woman must be delivered immediately. Caesarean section is said to have many advantages for the baby, but it is safest for the mother to birth vaginally if this is possible. Epidural analgesia is contraindicated in all but the mildest cases owing to the coagulopathy problems, unless these have been corrected first.

Convalescence is prolonged but usually complete. In the few cases where further pregnancy has been undertaken and recorded in the medical literature, recurrence has been low.

Gall bladder disease

Pregnancy appears to increase the likelihood of gallstone formation but not the risk of developing acute cholecystitis. Diagnosis of gall bladder disease is made by listening to the woman’s previous history or an ultrasound scan of the hepatobiliary tract, or both. She will require symptomatic treatment of the biliary colic by analgesia, hydration, nasogastric suction and antibiotics. Surgery should be avoided if at all possible.

Viral hepatitis

Viral hepatitis is the most common cause of jaundice in pregnancy (Fagan 2002). Acute infection affects approximately 1 in 1000 pregnancies and has an incubation period of 1–6 months. Symptoms include nausea, vomiting, anorexia, pain over the liver, mild diarrhoea, jaundice lasting several weeks and malaise. Fever is rare and for many the disease is asymptomatic, or mimics mild influenza. Its main spread is by blood, blood products and sexual activity. The virus can also be transmitted across the placenta. Hepatitis B is more common in tropical and developing countries, especially where nutrition is poor and the use of barrier contraceptives is limited, but it is also a particular problem among injecting drug users who share needles in the Western world (Fagan 2002). The more common infections are known as hepatitis A, B and C (D and E strains also exist and have many clinical and epidemiological features which overlap; concise diagnosis is made by blood tests).

Hepatitis A (HAV) occurs as an acute infection spread predominantly by ingesting water contaminated with faecal matter. It is endemic worldwide. Mother to baby transmission is rare but can occur at birth. HAV is a self-limiting illness which invariably results in complete recovery in otherwise healthy individuals. Vaccination is available. Strict hygiene and hand washing in health care settings reduces the risk of cross infection.

Hepatitis B (HBV) is a more serious infection because 5–10% of those infected become chronic carriers, and 25–30% of these will die as a result years later (Silverman 2006). In the Western world 0.5–5% of the population are chronic HBV carriers (Fagan 2002), continuing to test positive for the HBV surface antigen (HBsAg). However, in healthy adults 90% of primary cases of HBV resolve completely within 1–3 months. In the remaining 5–10%, hepatitis B surface antigen (HBsAg) remains in the serum and the woman is considered to be a chronic carrier. Some of these will clear the antigen over the course of the next 6 months and the rest will develop chronic active hepatitis, and the symptoms described above will also continue. A few will develop hepatic failure, which can result in death unless liver transplantation is available (Box 20.5). If hepatitis B is transmitted from mother to fetus and immunization does not prevent infection in the baby, the child will be at increased risk of chronic liver disease, cirrhosis and primary liver cancer in later life, these childhood implications often being severely underestimated (Fagan 2002). In pregnancy, the risk is considered to be greater to the fetus than the mother through transplacental passage of the virus and particularly through blood and body fluids at birth. Caesarean section does not prevent mother to fetus transmission. Diagnosis is made from the woman’s history of her symptoms and lifestyle. Serological studies will be performed, but it can be difficult to distinguish hepatitis B from other forms of viral hepatitis during the acute presentation, before antibodies have formed. Treatment is of the symptoms as they arise. Infection control measures should be instituted where the woman is considered to be infectious, and information not only about the disease, but also nutrition and sexual advice, should be offered. Liver function will be monitored and fetal condition assessed. Household contacts should be offered immunization once their HBsAg seronegativity is established. Sexual partners should be traced and offered testing and vaccination. Postnatally the mother will be encouraged to accept vaccination for the baby. Breastfeeding is not contraindicated (Fagan 2002).

Box 20.5 Pregnancy and liver transplantation

There have now been a number of pregnancies in women who have undergone liver transplantation before or during their pregnancy, many with successful outcomes. Although not desirable, liver transplantation in women of childbearing age is becoming increasingly common and such women now have the opportunity to consider having a family. However, the risks to pregnancy are great and these women require expert medical and midwifery care at a specialized centre equipped to deal with all of the complications, both of a physical and psychological nature, that such women may face.

Hepatitis C virus (HCV) was first identified in 1989 (Silverman 2006). The usual risk factors for transmission are blood and blood products and the use of shared intravenous needles. At least 90% of post-blood transfusion hepatitis can be traced to HCV, commonly from a blood donor who had yet to sero-convert at the time of blood donation and testing. (This suggests that blood transfusion should always be carefully considered and never undertaken without good clinical need.) Acute HCV has an incubation period of 30–60 days but 75% of those infected will be asymptomatic. In the remaining 25% symptoms include transient nausea and jaundice; 50% of those infected will progress to chronic HCV which is associated with B cell lymphomas and chronic liver disease. In the USA, the HCV rate appears to be 2.3–4.5% in pregnant women and placental (vertical) transmission rate suggests the risk to the baby is <5% (Silverman 2006). Optimal route of birth and safety of breastfeeding have yet to be established. While more difficult to acquire than HBV, HCV carries a much higher long term risk of chronic liver disease. No vaccine is available yet and the long-term outcome for infected newborns appears to be unreported at present in large epidemiological studies.

Skin disorders

Many skin changes are noticed by pregnant women; most of these are so common as to be described as physiological.

Treatment of pre-existing skin disorders, such as eczema or psoriasis, should continue as required, bearing in mind that some topical agents should be used with caution in pregnancy (such as steroid creams and applications containing nut oil derivatives).

Many women suffer from physiological pruritus in pregnancy, especially over the abdomen. Often emotional support, and the application of calamine lotion over the affected area, will suffice. However, for some women, pruritus with or without a rash will be a symptom of a more serious condition. Generalized pruritus should always be referred to a medical practitioner, as it may be a symptom of conditions such as intrahepatic cholestasis, liver or thyroid disease, lymphoma or scabies.

Pemphigoid gestationis (herpes gestationis)

This is a disease specific to pregnancy that usually occurs in the mid-trimester and persists into the postnatal period, although sometimes it starts after the birth. It affects 1 in 10 000 to 1 in 50 000 pregnancies (Engineer et al 2000) and its aetiology is unknown; however, it is thought that the condition is initiated by a maternal autoimmune response to paternal antigens and persists under the influence of pregnancy hormones. Despite its name, this skin condition is not related to the herpes virus – the misnomer came about in the nineteenth century when ‘herpes’ referred to skin blisters, rather than the virus.

The woman will complain of generalized itching and a burning sensation, and an erythematous rash will appear (see Plate 2). This is initially over the abdomen, but spreads to involve the remainder of the trunk and limbs. Blisters develop that may become infected and purulent, especially if the woman scratches.

The midwife should refer the woman to a medical practitioner and be supportive to her throughout her care. A skin biopsy may be needed to confirm the diagnosis. Topical or oral steroids may be prescribed depending on the severity of the disease. The lesions should be kept clean and may be covered to prevent the woman scratching. A diet high in vitamins should be encouraged. The woman may have her labour induced at about the 37th week of pregnancy, as there is controversial evidence that there is a greater incidence of intrauterine growth restriction with this condition, which is suggestive of a link with placental insufficiency (Kroumpouzos & Cohen 2006). The baby may have a rash when born and will need paediatric examination for any skin lesions, although these are usually clinically mild.

Without excessive scratching or secondary infection, the woman’s lesions will heal without scarring, although this may take some time and occasionally a few years. Once the condition has been activated by pregnancy, flare-ups may occur during menstruation, at ovulation or when the woman takes an oral contraceptive (Kroumpouzos & Cohen 2006). The condition may recur in subsequent pregnancies, especially with the same partner.

Disorders of the amniotic fluid

Normal amniotic fluid increases in amount throughout pregnancy from a few millilitres until 38 weeks, when there is about 1 L. After this, it diminishes to approximately 800 mL at term. Amniotic fluid is not static; the water of which it is largely composed changes every hour and the solutes change about every 3 hrs.

There are two chief abnormalities of amniotic fluid: hydramnios (or polyhydramnios) and oligohydramnios. These conditions are sometimes suspected on palpation and diagnosis is made ultrasonographically.

Hydramnios

The amount of liquor present in a pregnancy can be estimated by measuring ‘pools’ of liquor around the fetus with ultrasound scanning. The single deepest pool is measured to calculate the amniotic fluid volume (AFV). However, where possible a more accurate diagnosis may be gained by measuring the liquor in each of four quadrants around the fetus in order to establish an amniotic fluid index (AFI).

Hydramnios is said to be present when the deepest vertical pool of liquor (DP) exceeds 8 cm, or the calculated AFI is above the 95th centile for gestational age (Taylor & Fisk 2006). It is present in 0.2% of pregnancies, most commonly in a mild to moderate form.

Types

Recognition

The mother may complain of breathlessness and discomfort. If the hydramnios is acute in onset, she may have severe abdominal pain. The condition may cause exacerbation of symptoms associated with pregnancy such as indigestion, heartburn and constipation. Oedema and varicosities of the vulva and lower limbs may be present.

Abdominal examination

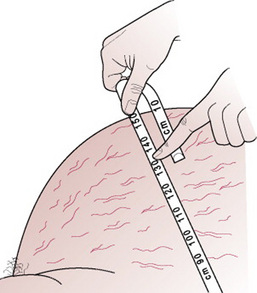

On inspection, the uterus is larger than expected for the period of gestation and is globular in shape. The abdominal skin appears stretched and shiny with marked striae gravidarum and obvious superficial blood vessels.

On palpation, the uterus feels tense and it is difficult to feel the fetal parts, but the fetus may be balloted between the two hands. A fluid thrill may be elicited by placing a hand on one side of the abdomen and tapping the other side with the fingers. A wave of fluid will move across from the side that is tapped and this is felt by the opposite examining hand. It may be helpful to measure the abdominal girth (Fig. 20.9), particularly in cases of acute hydramnios, in order to observe the rate of increase.

Auscultation of the fetal heart can be difficult if the quantity of fluid allows the fetus to move away from the stethoscope.

Ultrasonic scanning is used to confirm the diagnosis of hydramnios (Fig. 20.10). As well as calculating the DP, AFV and AFI, and therefore the severity of the hydramnios, scanning may reveal a multiple pregnancy or fetal abnormality. X-ray examination is not often performed and the images are usually hazy where there is a large quantity of amniotic fluid.

Management

The aim of managing this condition is to relieve maternal symptoms and optimize the length of gestation, prolonging it if safe. The cause of the condition should be determined if possible and fetal karyotyping may be indicated. The woman may be admitted to a consultant obstetric unit. Subsequent care will depend on the condition of the woman and fetus, the cause and degree of the hydramnios and the stage of pregnancy. Diabetes mellitus will be managed as an entity; the hydramnios is managed much as in other cases. The presence of fetal abnormality will be taken into consideration in choosing the mode and timing of birth. If gross abnormality is present, labour may be induced; if the fetus is suffering from an operable condition such as oesophageal atresia, transfer will be arranged to a neonatal surgical unit.

Mild asymptomatic hydramnios is managed expectantly. The woman is not usually admitted to hospital, but should be advised that if she suspects that her membranes have ruptured immediate admission is recommended. She should be encouraged to get adequate rest, and if she is working it may be helpful to discuss commencing maternity leave, although the physical nature of her job and the stress that may be engendered by stopping work should be assessed with the woman before making recommendations. Panting-Kemp et al (1999) suggest that if the hydramnios is found to be idiopathic, as is more likely in mild asymptomatic cases, she can be reassured that fetal outcome is likely to be good.

Regular ultrasound scans will reveal whether or not the hydramnios is progressive. Many cases of idiopathic hydramnios resolve spontaneously as pregnancy progresses (Hendricks et al 1991).

For a woman with symptomatic hydramnios, an upright position will help to relieve any dyspnoea and she may be given antacids to relieve heartburn and nausea. If the discomfort from the swollen abdomen is severe, then therapeutic amniocentesis, or amnioreduction, may be considered. However, this is not without risk, as infection may be introduced or the onset of labour provoked. It is at best a temporary relief as the fluid will rapidly accumulate again and the procedure may need to be repeated. Acute hydramnios managed by amnioreduction has a poor prognosis for the baby. The usual course of events is that the fluid continues to increase at an alarming rate, the membranes rupture spontaneously and the fetus or fetuses are born, grossly premature, in a river of amniotic fluid.

Administration of drugs such as indomethacin and sulindac reduce fetal urine production and consequently amniotic fluid, but use of these drugs is still experimental until the risks have been more fully ascertained (Taylor & Fisk 2006).

The woman may need to have labour induced in late pregnancy if the symptoms become worse. The lie must be corrected if it is not longitudinal and the membranes will be ruptured cautiously, allowing the amniotic fluid to drain out slowly in order to avoid altering the lie and to prevent cord prolapse. Placental abruption is also a hazard if the uterus suddenly diminishes in size.

Labour is usually normal but the midwife should be prepared for the possibility of postpartum haemorrhage. The baby should be carefully examined for abnormalities and the patency of the oesophagus ascertained by passing a nasogastric tube.

Oligohydramnios

Oligohydramnios is an abnormally small amount of amniotic fluid. At term it may be 300–500 mL but amounts vary and it can be even less. When diagnosed in the first half of pregnancy it is often found to be associated with renal agenesis (absence of kidneys) or Potter’s syndrome in which the baby also has pulmonary hypoplasia. When diagnosed at any time in pregnancy before 37 weeks, it may be due to fetal abnormality or to pre-term pre-labour rupture of the membranes where the amniotic fluid fails to re-accumulate. The lack of amniotic fluid reduces the intrauterine space and over time will cause compression deformities. The baby has a squashed-looking face, flattening of the nose, micrognathia (a deformity of the jaw) and talipes. The skin is dry and leathery in appearance.

Oligohydramnios sometimes occurs in the post-term pregnancy and is believed to be linked with the development of placental insufficiency. As placental function reduces, so too does perfusion to the fetal organ systems including the kidneys. The decrease in fetal urine formation leads to oligohydramnios, as the major component of amniotic fluid is fetal urine.

Recognition

On inspection, the uterus may appear smaller than expected for the period of gestation. The mother who has had a previous normal pregnancy may have noticed a reduction in fetal movements. When the abdomen is palpated the uterus is small and compact and fetal parts are easily felt. Breech presentation is possible. Auscultation is normal.

Ultrasonic scanning will enable differentiation of oligohydramnios from intrauterine growth restriction (although both may occur together where there is placental insufficiency). Renal abnormality may be visible on the scan. As with hydramnios, measurement of amniotic fluid and calculation of the AFI below the 5th centile will aid diagnosis.

Management

The aim in managing oligohydramnios is to establish its cause by investigating the aetiology and fetal effects. The woman may be admitted to hospital. If the ultrasound scan demonstrates renal agenesis the baby will not survive. Liquor volume will also be estimated from the ultrasound scan, and if renal agenesis is not present then further investigations will include careful questioning of the woman to check the possibility of pre-term rupture of the membranes. Placental function tests will also be performed.

Where fetal anomaly is not considered to be lethal, or the cause of the oligohydramnios is not known, prophylactic amnioinfusion with normal saline, Ringer’s lactate or 5% glucose may be performed in order to prevent compression deformities and hypoplastic lung disease, and prolong the pregnancy. Little evidence is available to determine the benefits and hazards of this intervention in mid-pregnancy. However, Pitt et al (2000) in a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials concluded that prophylactic intrapartum amnioinfusion in women with oligohydramnios resulted in lower caesarean section rates and improved neonatal outcome for structurally normal babies. Early indications are that this is a useful intervention.

In the case of term pregnancy, Grant (2006) reports that fetal surveillance by cardiotocography, amniotic fluid measurement by ultrasound and Doppler assessment of fetal and uteroplacental arteries is unlikely to predict the fetal outcome reliably. Furthermore, Grant et al (1989) demonstrated that maternal counting, recording and reporting of fetal movement was not effective in reducing stillbirths. Oligohydramnios in prolonged pregnancy in the absence of ruptured membranes remains a poorly understood phenomenon, and its management therefore remains highly controversial.

At any stage of pregnancy labour may intervene, or be induced where the fetus is viable because of the possibility of placental insufficiency. Epidural analgesia may be indicated because uterine contractions are often unusually painful with this condition. Impairment of placental circulation or cord compression may result in fetal hypoxia and therefore continuous fetal heart rate monitoring is desirable. In rare cases the membranes may adhere to the fetus. Also, if meconium is passed in utero it will be more concentrated and represent a greater danger to an asphyxiated baby during birth.

Pre-term pre-labour rupture of the membranes

PPROM occurs before 37 completed weeks’ gestation, where rupture of the fetal membranes occurs without the onset of spontaneous uterine activity resulting in cervical dilatation. (Term pre-labour rupture of the membranes is discussed in Ch. 30.)

PPROM affects 2% of pregnancies. Placental abruption is evident in 4–7% of women who present with PPROM. The condition has a 17–34% recurrence rate in subsequent pregnancies of affected women (Svigos et al 2006). It may be associated with cervical incompetence (although it is likely that uterine contractions accompany the rupture of membranes with this condition). There is a strong association between PPROM and maternal vaginal colonization with potentially pathogenic micro-organisms, with the incidence of subclinical chorioamnionitis said to be around 30% (Svigos et al 2006). Infection may both precede (and cause) or follow PPROM.

Risks of PPROM

Management

Because the pathophysiology of PPROM is still not fully understood, and trials into different management options have not been conclusive in their findings, contemporary management of the condition remains controversial.

Psychological consideration of the woman’s, and her partner’s, circumstances must always be considered with PPROM as it is known to be an extremely disturbing condition for parents, not least because causes and predictions of the outcome cannot be given. If PPROM is suspected, the woman will be admitted to the labour suite where a careful history is taken and rupture of the membranes confirmed by a sterile speculum examination of any pooling of liquor in the posterior fornix of the vagina. Very wet sanitary towels over a 6 hrs period will also offer a reasonably conclusive diagnosis if urine leakage has been excluded, but a positive Nitrazine test should not be considered conclusive when it is the only sign (Svigos et al 2006). Where diagnosis is in doubt, a fetal fibronectin immunoenzyme test is useful in confirming rupture of the membranes, and ultrasound scanning has some value.

Digital vaginal examination should be avoided to reduce the risk of introducing infection. Observations must also be made of the fetal condition from the fetal heart rate (an infected fetus may have a tachycardia) and maternal infection screen, temperature and pulse, uterine tenderness and any purulent or offensively smelling vaginal discharge. A decision on future management will then be made.

If the woman has a gestation of <32 weeks, the fetus appears to be uncompromised and APH and labour have been excluded, she will be managed expectantly. She is likely to be hospitalized and offered frequent ultrasound scans to check the growth of the fetus and the extent and complications of any oligohydramnios. She should be given corticosteroids as soon as PPROM is confirmed in case the baby is born (Crowley 2001), and if labour intervenes then tocolytic drugs will be considered to prolong the pregnancy. Known vaginal infection should be treated with antibiotics and prophylactic antibiotics may also be offered to women without symptoms of infection as the present evidence suggests that antibiotic administration following preterm rupture of the membranes (PROM) is associated with a statistically significant reduction in major markers of neonatal morbidity (but not mortality) and the data support the routine use of antibiotics from PPROM. The choice of antibiotic however, remains less clear but erythromycin seems to be the drug of choice for most women (Kenyon et al 2007). Sometimes the leak will re-seal (especially if it is a hindwater leak) and the pregnancy may proceed with no further complications. However, ‘re-sealing’ is said to occur in only 8% of cases of PPROM occurring in mid-trimester (Sciscione et al 2001). Serial amnioinfusion for otherwise normal pregnancies is an intervention that is gaining increasing interest; for instance Locatelli et al (2000) report improved perinatal outcomes where PPROM and oligohydramnios have occurred at <26 weeks’ gestation, although Taylor & Fisk (2006) report that the fluid usually leaks out again. Research is ongoing looking at cervical occlusion with fibrin gel. If membranes rupture before 24 weeks of gestation the outlook is not good; the fetus is likely to succumb either to the problems caused by oligohydramnios or to those caused by pre-term birth. The mother in such cases may be offered, and may accept termination of the pregnancy.