Chapter 1 Prescriptions, labels and SI units

Introduction

Regulation of medicines is controlled by legislation and it is important that the nurse understands the implications.

An understanding of what constitutes a valid prescription is essential before attempting to work out what is to be given to the patient who is prescribed a dose of medication.

Similarly, an appreciation of the information provided on the label of the available product(s) is a vital part of achieving safe practice and a good therapeutic outcome.

Knowledge and application of the system for expressing the strength of medicines is required by the nurse in the safe administration of medicines.

Legislation

The legislative background and professional standards which relate to calculating medicine doses are found in:

The Medicines Act 1968, encompassing:

The prescription

Prescribers, whether they are doctors, pharmacists or nurses, are legally bound to follow standard practice in prescribing and administration (Medicines Act 1968).

Before a prescription-only medicine (PoM) can be legally administered to a patient, except in specific emergency situations, a prescription that meets all legal requirements is required. The prescription must contain all the necessary information needed to administer the drug to the right patient, in the right dosage, at the right intervals and by the right route.

A prescription (now defined as a health prescription) means “a prescription issued by a doctor, a dentist, a supplementary prescriber, a nurse independent prescriber or a pharmacist independent prescriber” under or by virtue of the appropriate Acts and Orders (RPSGB 2009, p. 5).

In many cases, prescriptions are written for a medicine that will be self-administered, the patient (relative or home carer) taking responsibility for its administration.

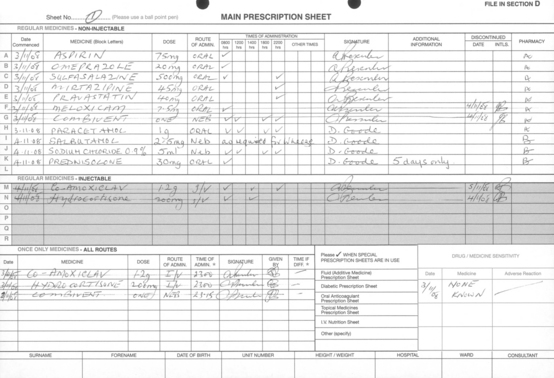

Hospital medicine administration may be more complex than medicine administration in the community. It is based on prescriptions written on forms specially designed for the purpose (Fig. 1.1). Whatever form the prescription takes or however it is generated, as well as the patient’s biographical details, it is always necessary to include the following information:

The patient’s height and weight should also appear on the prescription sheet, especially where the dose is dependent on body weight or body surface area (see pp. 50–54).

The form used will have a facility to record the individual doses administered.

Special treatment sheets are used in situations such as diabetes, ICU and oncology in order to accommodate the greater amount of detail required.

Electronic prescribing

Most drug administration is based on the interpretation of a prescription, which may be handwritten or computer-generated. Electronic prescribing, linked with automated drug selection is being increasingly developed in the UK. The advantages claimed for such systems include a reduction in medication error rate and a reduction in medicine supply turnaround times (Goundrey-Smith 2006).

The development of these systems will in no way obviate the need for nurses to maintain and develop their numerical skills. Indeed, new skills may be called for to ensure that all the benefits of advanced technology are experienced by patients.

Contents of a prescription

Medicine

It is standard practice to use either the pharmacopoeial name or other non-proprietary name. If neither of these situations applies, the rINN (or BAN) is used (BNF latest issue). The name of the medicinal substance should be written in block letters.

Dose

The dose of a drug is influenced by many factors. In the first place, the inherent properties of the drug or medicine (e.g. solubility, duration of action, bioavailability, activity, and formulation) must be taken into account. Having considered the properties of the drug and formulation, account must be taken of a whole range of issues relating to the patient and his/her condition before a dose is determined. In many cases, the standard dose will be applicable but careful consideration must be given to the age of the patient, the patient’s ability to excrete or metabolise the drug, and the presence of co-existing conditions. In some situations, it may be necessary for the prescriber to deviate from standard doses and calculate the dose to be given to the patient based on physiological and other parameters. These calculations are based on factors such as blood levels and creatinine clearance. Having determined the dose to be given, a good outcome for the patient can only be achieved if the administration is accurate in all respects.

Route

In many cases, the route of administration of a drug will be the oral route since this is very straightforward. However, the factors listed below will have a direct bearing on the route of administration.

Many of these factors are interrelated but thanks to modern drug formulation and delivery systems it is generally possible to use a route of administration that best suits the patient’s need (see Box 1.1).

Nurses’ responsibilities regarding prescriptions

The standards set for registered nurses and midwives (NMC 2008) in relation to prescriptions include:

The ‘label’

Manufacturers and pharmacists are required to follow standard practice in labelling (Medicines Act 1968).

The term ‘label’ is used in this text to mean the information relevant to the particular product which, with modern packaging, is often integral to the package.

Medicines are manufactured in different strengths. In order to be able to select the appropriate strength and work out what to give the patient, an understanding is required of how the strength of medicines is expressed.

The strength in relation to a relevant medicinal product means “the content of active ingredient in that product expressed quantitatively per dosage unit, per unit volume or by weight, according to the dosage form” (RPSGB 2009, p. 6).

When reading the label on the medicine container, particular attention should be paid to the following points:

The dose

The quantity of a drug to be given to the patient is arrived at by a series of steps. In the first place, the prescriber uses his/her knowledge of the drug and the condition when prescribing. The nurse then interprets and correlates the information on the prescription and the label (which may or may not involve a calculation) to determine the actual dosage to be given.

Many drugs are presented in a form in which the required dose is available without the need for a calculation. Examples of such products are shown in Box 1.2.

Even if no calculation as such is involved, the person administering the drug must ensure the correct dose(s) is given to the patient. It should be noted that it is possible to overdose when using a topical preparation especially one that contains a potent corticosteroid (see example on p. 176). This can only be done by careful reading and interpretation of the label on the container with particular reference to the actual dose contained in a given weight and/or volume, and correct interpretation of the prescription. Specialist information may have to be consulted.

Labels on medicine containers

Labels on medicine containers fulfil a number of functions that reflect the needs of all the professions involved in the manufacture, distribution and administration of medicines. The needs of patients in the community are also being increasingly catered for as patient packs become the norm. For example, labels show details of ingredients other than the active drug.

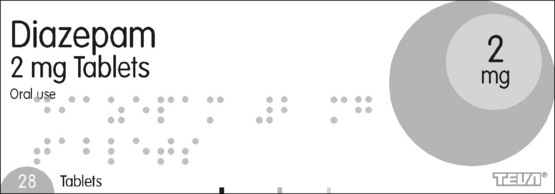

The content of the label on a medicine container is controlled by various legal requirements defined in Directive 92/27/EEC (BMA and RPSGB 2009 p. x). Requirements are specified for both the outer packaging and the inner foil or blister pack. Labelling on the outer package or on other packaging (e.g. bottle containing tablets) is more comprehensive than that on the inner (blister) pack.

The content of a typical label on an outer package is illustrated in Fig. 1.2. Not all the information listed below is illustrated. The focus for the nurse will be the name and strength of the product together with the expiry date. Batch numbers are used to identify the product in the event of any faults which may require a product recall.

Information which may not be of relevance to the nurse in a given situation will appear on many labels. Nurses need to be able to distinguish what information is important. The information required by regulation for the outer package is:

The following particulars normally appear on the blister- or foil-packs of tablets/capsules contained within the main package:

Errors have been known to have been caused by misinterpretation of the packaging. For example:

In order to make the demonstrations and exercises in Chapters 4, 5 and 8 more realistic, labels from actual pharmaceutical products have been reproduced (with permission). For technical reasons, some other labels have been produced “in-house”. In both cases, the images of the labels do not show all the detailed product information required by law. To do so would be impractical owing to pressure on space within the text. The information on all the “labels”, however, is technically correct as it stands and will enable the demonstrations to be followed and the exercises completed.

Drug names

The label on a medicine container will often show two names. For commercial reasons, the manufacturer gives prominence to the proprietary name. Most prescribing policies require the use of the British Approved Name (BAN) or the Recommended International Non-proprietary Name (rINN). Drug names which either sound alike or look alike can cause difficulties, and may even result in errors (McNulty and Spurr 1982a, 1982b).

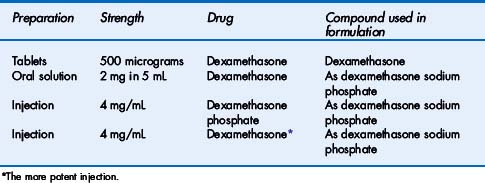

Drug compounds used in the formulation of medicines

In order to achieve the desired therapeutic outcome, a drug must be combined with other substances to produce a medicine (formulation process). The physical and chemical properties of the drug must be taken into account in this process. In some cases, it may be necessary to chemically modify the parent drug molecule to produce a compound that is fit for purpose.

As an example, morphine is insoluble in water and would not be suitable for formulation into an injection where a rapid and predictable therapeutic response is required. In practice, morphine sulphate (or hydrochloride), which is soluble in water, is used. In most cases, the actual chemical compound used in a formulation will not impact on a nurse’s daily practice. It is the duty of the prescriber to make his/her intention clear on the prescription but nurses must be capable of correctly interpreting prescriptions (and labels on medicines). Prescriptions calling for dexamethasone need particular attention since the modified compounds are not of equal potency to the parent compound. Dexamethasone 1 mg is equivalent to 1.2 mg dexamethasone phosphate or 1.3 mg dexamethasone sodium phosphate. The BNF includes preparations of dexamethasone as shown in Table 1.1.

Importance of labels (to nurses)

Although medicine labels have to meet certain legal requirements, not all the information given on a label is relevant to the nurse when administering a medicine. In order to achieve safe and accurate medicine administration, labels must be read and interpreted with the same degree of care that would be given to any clinical information (e.g. blood glucose level) used in patient care. Particular points to bear in mind when reading the label are as follows:

Metric system

The metric system is the standard system of weights (mass) and measures (volume) used today to express the strength of a medicine. The international system of units known as the SI system (Système International (d’Unités)) is the basis for the physical units used in practice. Other units derived from the basic metric units, for example the millimole (mmol), are also widely used. The metric units shown below should always be used. Only standard abbreviations should be used; they are always used in the singular, for example mg and not mgs.

Volume

The abbreviation ‘mL’ for millilitre is the printing convention used in the British National Formulary (BNF) (BMA and RPSGB latest issue) and is an acceptable abbreviation in clinical practice. The term litre should be written in full. Abbreviations such as “l” or “L” are open to misinterpretation.

Length

The above units of mass and volume are used in expressing the strengths of medicines. Units of length are used in calculating doses of certain drugs (e.g. opioids via syringe driver, certain dermatological preparations).

The metric system is in daily use in the UK in all aspects of life. Its use in clinical work should not present problems provided the guidance outlined below is followed:

Other methods of expressing strengths of medicines

The need for a standard system of weight and volume is fundamental to the practice of medicine. There are occasions, however, when the strength of a medicine cannot be expressed directly in units of weight and volume. For some products, the strength may be expressed as the number of parts (by weight) of the active ingredient (drug) contained in a given volume (mL). For example, the strength of epinephrine (adrenaline) injection is generally expressed as 1 in 1000 (1 g in 1000 mL) or 1 in 10 000 (1 g in 10 000 mL).

The reasons for the use of this method of expressing strength are traditional. In practice, this method is more convenient, and probably safer, than the more usual system where the weight in a given volume is expressed as milligrams or micrograms per 1 mL. This is because a very wide range of dosage regimens of this potent drug is used.

It is, however, important to understand how such an expression as 1 in 1000 can be converted to mg per mL or micrograms per mL. “1 in 1000” means that 1 g of the active drug is contained in 1000 mL of the injection solution, and:

Converting mg to micrograms, we find that:

A similar approach can be followed to show that 1 mL of a 1 in 10 000 solution contains 100 micrograms.

Units of activity

The strengths of some medicines obtained from natural biological (or semi-synthetic) sources are sometimes expressed in units of activity. Biological assays are used to standardise these products, since chemical methods cannot be applied. Examples of medicines where the strength is expressed in units are given in Table 1.2.

Table 1.2 Examples of drugs expressed in units of activity

| Drug group | Examples |

|---|---|

| Antibiotics | |

| Hormones | |

| Immunological products | |

| Vitamins | |

| Other drugs |

* May be expressed in units or micrograms.

Since the drugs in Table 1.2 marked with an asterisk may be prescribed in either units or micrograms, care is needed in interpreting prescriptions for these products (see BNF for strengths of available products).

Nurses will rarely be required to know the quantitative relationship between the units of activity and units of the metric system. The metric system equivalents for some units are given in the BNF, e.g. 1000 units is equivalent to 1 mg of dornase alfa. Local prescribing policies will normally determine how prescriptions should be written, i.e. in units of activity or units of mass (e.g. micrograms). When prescribing drugs in units of activity, the word “unit(s)” should not be abbreviated to “u” since, if badly written, it may be mistaken for a zero, which could introduce a major error.

Percentages

The strength of most medicines is expressed as grams, milligrams, micrograms, etc., together with the volume in millilitres if it is a liquid medicine. For topical medicines and certain large-volume injections, the strength of the ingredients is expressed as a percentage (see also pp. 22–26):

The term “percentage” means “parts per 100”.

So, for example, 10% means 10 parts per 100.

For a mixture of two solids, the percentage is expressed as weight in weight (w/w), e.g.:

If, however, the preparation is a solid dissolved or suspended in a liquid, the percentage is expressed as weight in volume (w/v), e.g.:

Where the product is a liquid diluted in another liquid, the percentage is expressed as volume in volume (v/v), e.g.:

In a few situations, a liquid is dispersed in a solid, in which case the percentage is expressed as volume in weight (v/w), e.g.:

When considering a medicine, it is important to recognise that the active ingredient is normally evenly distributed throughout the product.

Molarity

Another important way of expressing the strength (concentration) of a medicine is the use of molarity. Since moles and millimoles are used mainly in parenteral therapy, the subject of molarity is addressed in Chapter 6.

Metric/imperial system equivalents

Although all medicine strengths are expressed using the metric system, there may be occasions where there is a need to make conversions, for example, of body weight, between the imperial (non-metric) system and the metric system. These conversions are included in the BNF and BNF for children.

Good practice guidelines in writing and using metric weights and measures

BMA (British Medical Association) and RPSGB (Royal Pharmaceutical Society of Great Britain). British National Formulary. London: BMJ Group and RPS Publishing, 2009.

Cohen M.R., editor. Medication errors, second ed, Washington, DC: American Pharmacists’ Association, 2007.

Goundrey-Smith S. Electronic prescribing: experience in the UK and system design issues. The Pharmaceutical Journal. 2006;277:485.

McNulty H., Spurr P. Drug names which look or sound alike. The Pharmaceutical Journal. 1982:686-688. 11 December 1982

McNulty H., Spurr P. Drugs which can cause problems and confusion to health care staff. The Pharmaceutical Journal. 1982:721-722. 18 December 1982

NHS NPSA. Rapid response report. London: National Patient Safety Agency, 2008. 24 April

NMC. Standards for medicines management. London: Nursing and Midwifery Council, 2008.

RPSGB. Medicines, ethics and practice. Number 33. London: Royal Pharmaceutical Society of Great Britain, 2009.

The European Communities (Designation) (No. 2) Order, 1992. Statutory Instrument 1992 No. 1711