Retention

At sporting events, no matter how good things look for one team late in the game, the saying is “It’s not over till it’s over.” In orthodontics, although the patient may feel that treatment is complete when the appliances are removed, an important stage lies ahead. Orthodontic control of tooth position and occlusal relationships must be withdrawn gradually, not abruptly, if excellent long-term results are to be obtained. The type of retention should be included in the original treatment plan.

Why Is Retention Necessary?

Although a number of factors can be cited as influencing long-term results,1,2 orthodontic treatment results are potentially unstable and therefore retention is necessary for three major reasons: (1) the gingival and periodontal tissues are affected by orthodontic tooth movement and require time for reorganization when the appliances are removed, (2) the teeth may be in an inherently unstable position after the treatment, so that soft tissue pressures constantly produce a relapse tendency, and (3) changes produced by growth may alter the orthodontic treatment result. If the teeth are not in an inherently unstable position and if there is no further growth, retention still is vitally important until gingival and periodontal reorganization is completed. If the teeth are unstable, as often is the case following significant arch expansion, gradual withdrawal of orthodontic appliances is of no value. The only possibilities are accepting relapse or using permanent retention. Finally, whatever the situation, retention cannot be abandoned until growth is essentially completed.

Reorganization of the Periodontal and Gingival Tissues

Widening of the periodontal ligament space and disruption of the collagen fiber bundles that support each tooth are normal responses to orthodontic treatment (see Chapter 8). In fact, these changes are necessary to allow orthodontic tooth movement to occur. Even if tooth movement stops before the orthodontic appliance is removed, restoration of the normal periodontal architecture will not occur as long as a tooth is strongly splinted to its neighbors, as when it is attached to a rigid orthodontic archwire (so holding the teeth with passive archwires cannot be considered the beginning of retention). Once the teeth can respond individually to the forces of mastication (i.e., once each tooth can be displaced slightly relative to its neighbor as the patient chews), reorganization of the periodontal ligament (PDL) occurs over a 3- to 4-month period, and the slight mobility present at appliance removal disappears.

This PDL reorganization is important for stability because of the periodontal contribution to the equilibrium that normally controls tooth position. To briefly review our current understanding of the pressure equilibrium (see Chapter 5 for a detailed discussion), the teeth normally withstand occlusal forces because of the shock-absorbing properties of the periodontal system. More importantly for orthodontics, small but prolonged imbalances in tongue-lip-cheek pressures or pressures from gingival fibers that otherwise would produce tooth movement are resisted by “active stabilization” due to PDL metabolism. It appears that this stabilization is caused by the same force-generating mechanism that produces eruption. The disruption of the PDL produced by orthodontic tooth movement probably has little effect on stabilization against occlusal forces, but it reduces or eliminates the active stabilization, which means that immediately after orthodontic appliances are removed, teeth will be unstable in the face of occlusal and soft tissue pressures that can be resisted later. This is the reason that every patient needs retainers for at least a few months.

The gingival fiber networks are also disturbed by orthodontic tooth movement and must remodel to accommodate the new tooth positions. Both collagenous and elastic fibers occur in the gingiva, and Reitan showed many years ago that the reorganization of both occurs more slowly than that of the PDL itself.3 Within 4 to 6 months, the collagenous fiber networks within the gingiva have normally completed their reorganization, but the elastic supracrestal fibers remodel extremely slowly and can still exert forces capable of displacing a tooth at 1 year after removal of an orthodontic appliance. In patients with severe rotations, sectioning the supracrestal fibers around teeth that initially were severely rotated, at or just before the time of appliance removal, is a recommended procedure because it reduces relapse tendencies resulting from this fiber elasticity (see Figure 16-18).

This timetable for soft tissue recovery from orthodontic treatment outlines the principles of retention against intra-arch instability. These are:

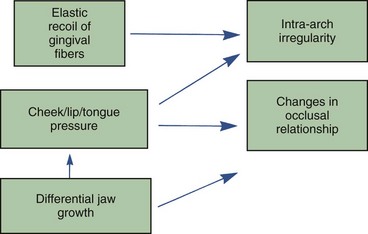

1. The direction of potential relapse can be identified by comparing the position of the teeth at the conclusion of treatment with their original positions. Teeth will tend to move back in the direction from which they came, primarily because of elastic recoil of gingival fibers but also because of unbalanced tongue–lip forces (Figure 17-1).

FIGURE 17-1 The major causes of relapse after orthodontic treatment include the elasticity of gingival fibers, cheek/lip/tongue pressures, and jaw growth. Gingival fibers and soft tissue pressures are especially potent in the first few months after treatment ends, before PDL reorganization has been completed. Unfavorable growth is the major contributor to changes in occlusal relationships.

2. Teeth require essentially full-time retention after comprehensive orthodontic treatment for the first 3 to 4 months after a fixed orthodontic appliance is removed. To promote reorganization of the PDL, however, the teeth should be free to flex individually during mastication, as the alveolar bone bends in response to heavy occlusal loads during mastication (see Chapter 8). This requirement can be met by a removable appliance worn full time except during meals or by a fixed retainer that is not too rigid.

3. Because of the slow response of the gingival fibers, retention should be continued for at least 12 months if the teeth were quite irregular initially but can be reduced to part time after 3 to 4 months. After approximately 12 months, it should be possible to discontinue retention in nongrowing patients. More precisely, the teeth should be stable by that time if they ever will be, and in most patients some degree of re-crowding of lower incisors long term should be expected. Some patients who are not growing will require permanent retention to maintain the teeth in what would otherwise be unstable positions because of lip, cheek, and tongue pressures that are too large for active stabilization to balance out. Patients who will continue to grow, however, usually need retention until growth has reduced to the low levels that characterize adult life.

Occlusal Changes Related to Growth

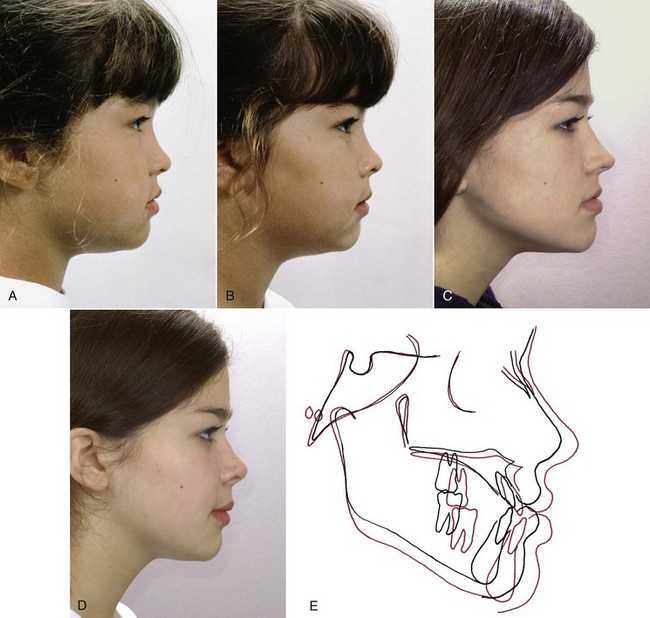

A continuation of growth is particularly troublesome in patients whose initial malocclusion resulted largely or in part from the pattern of skeletal growth. Skeletal problems in all three planes of space tend to recur if growth continues (Figure 17-2) because most patients continue in their original growth pattern as long as they are growing. Transverse growth is completed first, which means that long-term transverse changes are less of a problem clinically than changes from late anteroposterior and vertical growth.

FIGURE 17-2 Growth after early treatment of a Class III problem is likely to cause the problem to reappear, as in this girl. A, Profile at age 7, prior to treatment. B, Age 8, after treatment with reverse-pull headgear (facemask). C, Five years later, after the adolescent growth spurt. D, After orthognathic surgery. E, Cephalometric superimposition showing the pattern of growth from the end of the facemask treatment (black) through adolescence to just prior to surgery (red).

Comprehensive orthodontic treatment is usually carried out in the early permanent dentition, and the duration is typically between 18 and 30 months. This means that active orthodontic treatment is likely to conclude at age 14 to 15, while anteroposterior and particularly vertical growth often do not subside even to the adult level until several years later. Long-term studies of adults have shown that very slow growth typically continues throughout adult life, and the same pattern that led to malocclusion in the first place can contribute to a deterioration in occlusal relationships many years after orthodontic treatment is completed.4 In late adolescence, continued growth in the pattern that caused a Class II, Class III, deep bite, or open bite problem in the first place is a major cause of relapse after orthodontic treatment and requires careful management during retention.5

Retention After Class II Correction

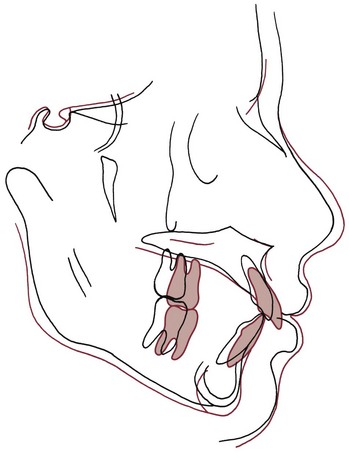

Relapse toward a Class II relationship must result from some combination of tooth movement (forward in the upper arch, backward in the lower arch, or both) and differential growth of the maxilla relative to the mandible (Figure 17-3). As might be expected, tooth movement caused by local periodontal and gingival factors can be an important short-term problem, whereas differential jaw growth is a more important long-term problem because it directly alters jaw position and this contributes to repositioning of teeth.

FIGURE 17-3 Cephalometric superimposition demonstrating growth-related relapse in a patient treated to correct Class II malocclusion. Black, Immediate posttreatment, age 13; red, recall, age 17. After treatment, both jaws grew downward and forward, but mandibular growth did not match maxillary growth, and the maxillary dentition moved forward relative to the maxilla. As in Class III patients, early treatment has little or no effect on the underlying growth pattern.

Overcorrection of the occlusal relationships as a finishing procedure is an important step in controlling tooth movement that would lead to Class II relapse. Even with good retention, 1 to 2 mm of anteroposterior change caused by adjustments in tooth position is likely to occur after treatment, particularly if Class II elastics were employed. This change occurs relatively quickly after active treatment stops.

In Class II treatment, it is important not to move the lower incisors too far forward, but this can happen easily with Class II elastics. In this situation, lip pressure will tend to upright the protruding incisors, leading relatively quickly (often in only a few months after full-time retainer wear is discontinued) to crowding and return of both overbite and overjet. As a general guideline, if more than 2 mm of forward repositioning of the lower incisors occurred during treatment, permanent retention will be required.

The slower long-term relapse that occurs in some patients who did not have inappropriate tooth movement results primarily from differential jaw growth. The amount of growth remaining after orthodontic treatment will obviously depend on the age, sex, and relative maturity of the patient, but after treatment that involved growth modification, further growth almost surely will result in some loss of the previous correction as the original growth pattern persists.

In Class II patients, this relapse tendency can be controlled in one of two ways. The first, the traditional fixed appliance approach of the 1970s and earlier, is to continue headgear to the upper molars on a reduced basis (at night, for instance) in conjunction with a retainer to hold the teeth in alignment. This requires leaving the first molar bands on when everything is removed at the end of active treatment. It is quite satisfactory in well-motivated patients who have been wearing headgear and are willing to continue it during treatment and is compatible with traditional retainers that are worn full time initially, but compliance with headgear becomes a problem with all but the most cooperative patients.

The other method is to use a functional appliance of the activator-bionator type to hold both tooth position and the occlusal relationship (Figure 17-4). To the patient, this intraoral device is just another variety of retainer, and compliance is less of a problem. If the patient does not have excessive overjet, as should be the case at the end of active treatment, the construction bite for the functional appliance is taken without any mandibular advancement—the idea is to prevent a Class II malocclusion from recurring, not to actively treat one that already exists.

FIGURE 17-4 In patients in whom further growth in the original Class II pattern is expected after active treatment is completed, a functional appliance worn at night can be used to maintain occlusal relationships. In a typical Class II deep bite patient, the lower posterior teeth are allowed to erupt slightly, while other teeth are tightly controlled.

A potential difficulty is that the functional appliance will be worn only part time, typically just at night, and daytime retainers of conventional design also will be needed to control tooth position during the first few months. The extra retainer from the beginning makes sense for a patient with a severe growth problem. For patients with less severe problems, in whom continued growth may or may not cause relapse, it may be more rational to use only conventional maxillary and mandibular retainers initially and replace them with a functional appliance to be worn at night if relapse is beginning to occur after a few months.

This type of retention is often needed for 12 to 24 months or more in a patient who had a skeletal problem initially. The guideline is: the more severe the initial Class II problem and the younger the patient at the end of active treatment, the more likely that either headgear or a functional appliance will be needed during posttreatment retention. It is better and much easier to prevent relapse from differential growth than to try to correct it later.

Retention After Class III Correction

Retaining a patient after correcting a Class III malocclusion early in the permanent dentition can be frustrating, because relapse from continuing mandibular growth is very likely to occur and such growth is extremely difficult to control. Applying a restraining force to the mandible, as from a chin cup, is not nearly as effective in controlling growth in a Class III patient as applying a restraining force to the maxilla is in Class II problems. As we have noted in previous chapters, a chin cup tends to rotate the mandible downward, causing growth to be expressed more vertically and less horizontally, and Class III functional appliances have the same effect. If face height is normal or excessive after orthodontic treatment and relapse occurs from mandibular growth, surgical correction after the growth has expressed itself may be the only answer. In mild Class III problems, a functional appliance or a positioner may be enough to maintain the occlusal relationships during posttreatment growth.

Retention After Deep Bite Correction

Correcting excess overbite is an almost routine part of orthodontic treatment, and therefore the majority of patients require control of the vertical overlap of incisors during retention. This is accomplished most readily by using a removable upper retainer made so that the lower incisors will encounter the baseplate of the retainer if they begin to slip vertically behind the upper incisors (Figure 17-5). The procedure, in other words, is to build a potential biteplate into the retainer, which the lower incisors will contact if the bite begins to deepen. The retainer does not separate the posterior teeth.

FIGURE 17-5 Control of the vertical position of teeth in retention is as important as controlling alignment, especially in patients who had a deep bite or open bite initially. For this deep bite patient, the lower incisors contact the palatal acrylic of the upper retainer, while the upper incisors contact the facial surface of the lower retainer. This prevents incisor eruption that would lead to return of excessive overbite.

Because vertical growth continues into the late teens, a maxillary removable retainer with a bite plane often is needed for several years after fixed appliance orthodontics is completed. Bite depth can be maintained by wearing the retainer only at night, after stability in other regards has been achieved.

Retention After Anterior Open Bite Correction

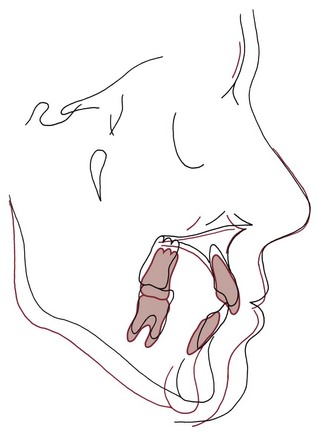

Relapse into anterior open bite can occur by any combination of depression of the incisors and elongation of the molars. Active habits (of which thumbsucking is the best example) can produce intrusive forces on the incisors, while at the same time leading to an altered posture of the jaw that allows posterior teeth to erupt. If thumbsucking continues after orthodontic treatment, relapse is all but guaranteed. Tongue habits, particularly tongue–thrust swallowing, are often blamed for relapse into open bite, but the evidence to support this contention is not convincing (see discussion in Chapter 5). In patients who do not place some object between the front teeth, return of open bite is almost always the result of elongation of the posterior teeth, particularly the upper molars, without any evidence of intrusion of incisors (Figure 17-6). Controlling eruption of the upper molars therefore is the key to retention in open bite patients.

FIGURE 17-6 Four years after removal of the orthodontic appliances, this 17-year-old has an anterior open bite, 5 mm of overjet with an end-on molar relationship, and severe crowding of the mandibular incisors. Relapse of this type is associated with little or no mandibular growth and a downward and backward mandibular rotation as the maxilla grows downward and upper posterior teeth erupt, as shown in the cephalometric superimposition from the end of treatment to 4-year recall. The incisor crowding is due to uprighting and lingual repositioning of the incisors as the mandibular rotation thrusts them into the lower lip.

The preferred method to control relapse toward anterior open bite is an appliance with bite blocks between the posterior teeth that creates several millimeters of jaw separation (an open bite activator or bionator; Figure 17-7). This stretches the patient’s soft tissues to provide a force opposing eruption. High-pull headgear to the upper molars, in conjunction with a standard removable retainer to maintain tooth position, also can be effective, but the intraoral appliance is better tolerated and controls eruption of lower as well as upper posterior teeth. Excessive vertical growth and eruption of the posterior teeth often continue until late in the teens or early twenties, so retention also must continue well beyond the typical completion of active treatment.

FIGURE 17-7 Controlling the eruption of posterior teeth during late vertical growth is the key to preventing open bite relapse. There are two major approaches to accomplishing this: a maxillary retainer with bite blocks (or a functional appliance) to impede eruption, as shown here in a patient soon after his severe open bite was corrected, or high-pull headgear. In a patient with the long-face growth pattern, either must be continued as a nighttime retainer through the late teens. Although high-pull headgear can be quite effective in a cooperative patient, a removable appliance with bite blocks is a better choice for most patients for two reasons: it controls eruption of both the upper and lower molars, and usually it is better accepted because it is easier to wear.

A patient with a severe open bite problem is particularly likely to benefit from having conventional maxillary and mandibular retainers for daytime wear and an open bite bionator as a nighttime retainer from the beginning of the retention period.

Retention of Lower Incisor Alignment

Not only can continued skeletal growth affect occlusal relationships, it also has the potential to alter the position of teeth. If the mandible grows forward or rotates downward, the effect is to carry the lower incisors into the lip, which creates a force tipping them distally. For this reason, continued mandibular growth in normal or Class III patients is strongly associated with crowding of the lower incisors (see Figure 17-1). Incisor crowding also accompanies the downward and backward rotation of the mandible seen in skeletal open bite problems (see Figure 17-6). A retainer in the lower incisor region is needed to prevent crowding from developing until growth has declined to adult levels.

It often has been suggested that orthodontic retention should be continued, at least on a part-time basis, until the third molars have either erupted into normal occlusion or been removed. The implication of this guideline, that pressure from the developing third molars causes late incisor crowding, is almost surely incorrect (see Chapter 5). On the other hand, because eruption of third molars or their extraction usually does not take place until the late teen years, the guideline is not a bad one in its emphasis on prolonged retention in patients who are continuing to grow.

Most adults, including those who had orthodontic treatment and once had perfectly aligned teeth, end up with some crowding of lower incisors. In a group of patients who had first premolar extraction and treatment with the edgewise appliance, only about 30% had perfect alignment 10 years after retainers were removed and nearly 20% had marked crowding.6 Which individuals would have posttreatment crowding could not be predicted from the characteristics of the original malocclusion or variables associated with treatment. It seems likely that late mandibular growth is the major contributor to this crowding tendency. It makes sense therefore to routinely retain lower incisor alignment until mandibular growth has declined to adult levels (i.e., until the late teens in girls and into the early twenties in boys).

Timing of Retention: Summary

In summary, retention is needed for all patients who had fixed orthodontic appliances to correct intra-arch irregularities. It should be:

• Essentially full time for the first 3 to 4 months, except that removable retainers not only can but should be removed while eating, and fixed retainers should be flexible enough to allow displacement of individual teeth during mastication (unless periodontal bone loss or other special circumstances require permanent splinting).

• Continued on a part-time basis for at least 12 months to allow time for remodeling of gingival tissues.

• If significant growth remains, continued part time until completion of growth.

For practical purposes, this means that nearly all patients treated in the early permanent dentition will require retention of incisor alignment at least until their late teens, and in those with skeletal disproportions initially, part-time use of a functional appliance or extraoral force probably will be needed.

Removable Appliances as Retainers

Removable appliances can serve effectively for retention against intra-arch instability and are also useful as retainers in patients with growth problems (in the form of modified functional appliances or part-time headgear). If permanent retention is needed, a fixed retainer should be used in most instances, and fixed retainers (see the following section of this chapter) are also indicated for intra-arch retention when irregularity in a specific area is likely to be a problem.

Hawley Retainers

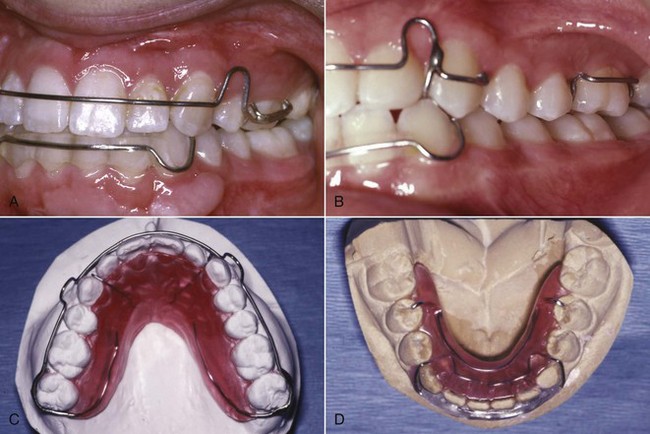

By far, the most common removable retainer is the Hawley retainer, designed in the 1920s as an active removable appliance. It incorporates clasps on molar teeth and a characteristic outer bow with adjustment loops, usually spanning from canine to canine (Figure 17-8). Because it covers the palate, it automatically provides a potential bite plane to control overbite.

FIGURE 17-8 A canine-to-canine anterior bow and clasps on molars are the characteristic features of the Hawley retainer design. A, A Hawley retainer for a patient with maxillary premolar extractions, with the anterior bow soldered to Adams clasps on the first molars so that the extraction site is held closed. B, The adjustment loop of the Hawley anterior bow often keeps the wire from having full contact with the canines. If good control of the canines is needed, as in this patient whose canines were facially positioned before treatment, a wire that extends across the canines can be soldered to an anterior bow that crosses distal to the lateral incisor. C, In a patient whose second molars have erupted, a wraparound outer bow soldered to C-clasps on the second molars provides a way to avoid interference as the retainer wire crosses the occlusion, but a bow with such a long span will be quite flexible. D, For a mandibular retainer, the wire Hawley bow is less effective than a wire-reinforced acrylic bar that tightly contacts the lower incisors. This Moore design has almost completely replaced the Hawley design for lower removable retainers that extend to the posterior teeth. E, A removable maxillary retainer with a clear outer bow, which fits more tightly than a metal wire and is better esthetically but cannot be adjusted to modify tooth positions without starting over with a new retainer.

The ability of this retainer to provide some tooth movement was a particular asset with fully banded fixed appliances, since one function of the retainer was to close band spaces between the incisors. With bonded appliances on the anterior teeth or after using a tooth positioner for finishing, there is no longer any need to close spaces with a retainer. However, the outer bow provides excellent control of the incisors even if it is not adjusted to retract them, especially if the anterior section has acrylic added to fit more tightly, or perhaps even better, if the anterior segment is formed from a clear polymer (see Figure 17-8, E).

When first premolars have been extracted, one function of a retainer is to keep the extraction space closed, which the standard design of the Hawley retainer cannot do. Even worse, the standard Hawley labial bow extends across a first premolar extraction space, tending to wedge it open. A common modification of the Hawley retainer for use in extraction cases is a bow soldered to the buccal section of Adams clasps on the first molars, so that the action of the bow helps hold the extraction site closed (see Figure 17-8). Alternative designs for extraction cases are to wrap the labial bow around the entire arch, using circumferential clasps on second molars for retention, or to bring the labial wire from the baseplate between the lateral incisor and canine and to bend or solder a wire extension distally to control the canines. The latter alternative does not provide an active force to keep an extraction space closed but avoids having the wire cross through the extraction site and gives positive control of canines that were labially positioned initially (which the loop of the traditional Hawley design may not provide).

The clasp locations for a Hawley retainer must be selected carefully, since clasp wires crossing the occlusal table can disrupt rather than retain the tooth relationships established during treatment. Circumferential clasps on the terminal molar may be preferred over the more effective Adams clasp if the occlusion is tight.

The palatal coverage of a removable plate like the maxillary Hawley retainer makes it possible to incorporate a bite plane lingual to the upper incisors to control bite depth. For any patient who once had an excessive overbite, light contact of the lower incisors against the baseplate of the retainer is desired.

Removable Wraparound (Clip) Retainers

A second major type of removable orthodontic retainer is the wraparound or clip-on retainer, which consists of a plastic bar (usually wire-reinforced) along the labial and lingual surfaces of the teeth (Figure 17-9). A full-arch wraparound retainer firmly holds each tooth in position. This is not necessarily an advantage, since one object of a retainer should be to allow each tooth to move individually, stimulating reorganization of the PDL. In addition, a wraparound retainer, though quite esthetic, is often less comfortable than a Hawley retainer and may not be effective in maintaining overbite correction. A full-arch wraparound retainer is indicated primarily when periodontal breakdown requires splinting the teeth together.

FIGURE 17-9 A, A removable clip-type retainer that controls alignment of only the anterior teeth (3-3 clip or as shown here, 4-4 clip) often is preferred as a removable lower retainer because if the lower posterior teeth were well aligned prior to treatment, retention of these teeth usually is unnecessary, and undercuts lingual to the lower molars make it difficult to place a lower retainer that extends posteriorly. B, An anterior clip retainer in the maxillary arch is particularly useful when it is necessary to keep spaces from reopening. It also can be used to prevent re-rotation of maxillary incisors, but contact of the lower incisors with a maxillary clip retainer often becomes a problem. C, Anterior clip retainers in both arches for this patient, who had maxillary and mandibular anterior spacing prior to treatment.

A variant of the wraparound retainer, the canine-to-canine clip-on retainer, is widely used in the lower anterior region. This appliance has the great advantage that it can be used to realign irregular incisors if mild crowding has developed after treatment (see the discussion of active retainers in the last section of this chapter), but it is well tolerated as a retainer alone. An upper canine-to-canine clip-on retainer occasionally is useful in adults with long clinical crowns but rarely is indicated and usually would not be tolerated in younger patients because of occlusal interferences.

In a lower extraction case, usually it is a good idea to extend a canine-to-canine wraparound distally on the lingual only to the central groove of the first molar (see Figure 17-8, D). This is called a Moore retainer. It provides control of the second premolar and the extraction site but must be made carefully to avoid lingual undercuts in the premolar and molar region. Posterior extension of the lower retainer, of course, also is indicated when the posterior teeth were irregular before treatment.

Clear (Vacuum-Formed) Retainers

A retainer made with a clear heat-softened plastic that is sucked down tightly over the teeth with a device that creates a vacuum to do that is another form of the older wraparound retainer made with acrylic and wire. Because the material is transparent and thin, a vacuum-formed retainer is all but invisible, and most patients prefer them. At present this is the most widely used retainer for the maxillary arch, and patients using a clear retainer report greater satisfaction with their treatment than those with other types of retainers.7 In terms of effectiveness of maintaining incisor alignment, a Swedish study reported no difference between these retainers and a bonded wire retainer.6 This implies excellent compliance with the removable suck-down retainer, and it does seem that patients are more likely to wear a clear retainer full time.

As with anything else, there are limitations to vacuum-formed retainers: (1) the thickness of the material over the occlusal surface of the teeth can become a problem, especially if both the upper and lower arches are retained in this way. It does no harm to open small holes in the occlusal surface of the retainer at points of occlusal contact (as seen with equilibrating paper) to keep from separating the teeth so much, but the combination of a vacuum-formed upper and a fixed lower retainer greatly reduces this problem; (2) the retainer maintains alignment but does not control deepening of the bite as well as a palate-covering Hawley retainer; and (3) after a few months, the retainer tends to crack and discolor to the point that it has to be replaced. One study reported that using the final aligner in an Invisalign sequence (see Chapter 18) as a retainer was not as effective as other retainer types,8 perhaps because a thinner material is used in clear-aligner therapy.

Positioners as Retainers

A tooth positioner also can be used as a removable retainer, either fabricated for this purpose alone, or more commonly, continued as a retainer after serving initially as a finishing device. Positioners are excellent finishing devices and under special circumstances can be used to an advantage as retainers. For routine use, however, a positioner does not make a good retainer. The major problems are:

1. The pattern of wear of a positioner does not match the pattern usually desired for retainers. Because of its bulk, patients often have difficulty wearing a positioner full time or nearly so. In fact, positioners tend to be worn less than the recommended 4 hours per day after the first few weeks, although they are reasonably well tolerated by most patients during sleep.

2. Positioners do not retain incisor irregularities and rotations as well as standard retainers. The problem with alignment follows directly from the first one: a retainer is needed nearly full time initially to control it. The flexible material of a positioner does hold a tooth tightly enough to control rotations.

3. Overbite tends to increase while a positioner is being worn during finishing (see Chapter 16). This effect extends into retention and perhaps is greater when the positioner is worn only a small percentage of the time.

A positioner does have one major advantage over a standard removable or wraparound retainer, however—it maintains the occlusal relationships as well as intra-arch tooth positions. For a patient with a tendency toward Class III relapse, a positioner made with the jaws rotated somewhat downward and backward may be useful. Although a positioner with the teeth set in a slightly exaggerated “supernormal” from the original malocclusion can be used for patients with a skeletal Class II or open bite growth pattern, it is less effective in controlling growth than a functional appliance or nighttime headgear.

In fabricating a positioner, it is necessary to separate the teeth by 2 to 4 mm. This means that an articulator mounting that records the patient’s hinge axis allows more accurate fabrication. As a general guideline, the more the patient deviates from the average normal, and the longer the positioner will be worn, the more important it is to make it on articulator-mounted casts. If a positioner is to be used for only 2 to 4 weeks as a finishing device in a patient who will have some vertical growth during later retention, and if the patient has an approximately normal hinge axis, an individualized articulator mounting makes little or no practical difference.

The usual sign of a positioner made to an incorrect hinge axis is some separation of the posterior teeth when the incisors are in contact. Patients wearing a positioner as a retainer should be checked carefully to see that this effect is not occurring.

Fixed Retainers

Fixed (bonded) orthodontic retainers are normally used in situations where intra-arch instability is anticipated and prolonged retention is planned.9 There are four major indications:

1. Maintenance of lower incisor position during late growth. As has been discussed previously, the major cause of lower incisor crowding in the late teen years, in both patients who have had orthodontic treatment and those who have not, is late growth of the mandible in the normal growth pattern. Especially if the lower incisors have previously been irregular, even a small amount of differential mandibular growth between ages 16 and 20 can cause a return of incisor crowding. Relapse into crowding is almost always accompanied by lingual tipping of the central and lateral incisors in response to the pattern of growth.

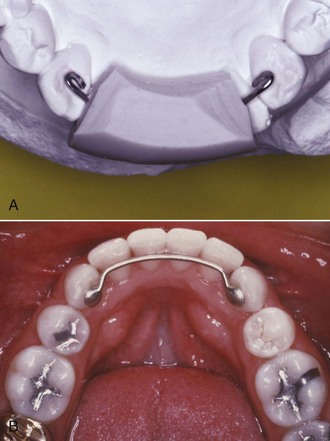

An excellent retainer to hold these teeth in alignment is a fixed lingual bar, attached only to the canines (or to canines and first premolars) and resting against the flat lingual surface of the lower incisors above the cingulum (Figure 17-10). This prevents the incisors from moving lingually and is also reasonably effective in maintaining correction of rotations in the incisor segment.

FIGURE 17-10 A, A bonded canine-to-canine retainer in the lower arch is an excellent way to maintain alignment. It is fabricated on a lower cast, often with a carrier to hold it in position while being bonded. Note the design with wire loops on the canines to provide retention when the retainer is bonded. B, A bonded canine-to-canine retainer, with retention pads, in place. Data now show that wire retention loops decrease the chance that the retainer will break loose.

Fixed canine-to-canine retainers must be made from a wire heavy enough to resist distortion over the rather long span between these teeth. Usually 28 or 30 mil steel is used for this purpose (see Figure 17-10), with a loop bent in the end of the wire to improve retention. With this design, a bonded retainer can remain in place for many years. Although there has been concern about a long-term effect on periodontal health, long-term recall of patients who have worn a bonded lower retainer for more than 20 years has shown no periodontal problems.10

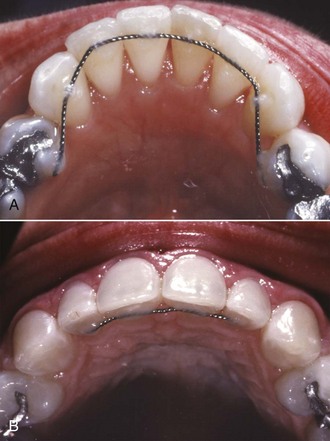

It is also possible to bond a fixed lingual retainer to one or more of the incisor teeth. The major indication for this variation is a tooth or teeth that had been severely rotated. Whatever the type of retainer, however, it is desirable not to hold the teeth rigidly during retention. For this reason, if the span of the retainer wire is reduced by bonding an intermediate tooth or teeth, a more flexible wire should be used. A good choice for a fixed retainer with adjacent teeth bonded (Figure 17-11) is a braided steel archwire of 17.5 mil diameter.

FIGURE 17-11 A, Bonding a wire to all the mandibular anterior teeth (canine-to-canine or premolar-to-premolar) is indicated if spaces existed in the lower anterior segment prior to treatment, or if severe rotations were corrected. A light wire (17.5 or 19.5 mil twist) should be used. A retainer of this type must be kept under observation because a bond failure on one tooth is unlikely to be noticed by the patient and severe decalcification can occur in that area. B, A section of twist wire, usually bonded just on the four incisors, also can be used to maintain alignment of maxillary teeth that were severely displaced. Bonded attachments on the lingual of the upper incisors also can serve to prevent deepening of the bite as lower incisors erupt.

2. Diastema maintenance. A second indication for a fixed retainer is a situation where teeth must be permanently or semipermanently bonded together to maintain the closure of a space between them. This is encountered most commonly when a diastema between maxillary central incisors has been closed. Even if a frenectomy has been carried out (see Figure 14-22), there is a tendency for a small space to open up between the upper central incisors. The best retainer for this purpose is a bonded section of flexible wire, as shown in Figure 17-12. The wire should be contoured so that it lies near the cingulum to keep it out of occlusal contact. The object of the retainer is to hold the teeth together while allowing them some ability to move independently during function, hence the importance of a flexible wire. A removable Hawley retainer can be worn in addition to a fixed segment retainer like this and usually is needed to control the other teeth. An alternative (Figure 17-13) is a solid wire configured to avoid the tooth contacts to facilitate flossing, which also can incorporate stops to prevent deepening of the bite.

FIGURE 17-12 Bonded lingual retainer for maintenance of a maxillary central diastema. A, 17.5 mil twist wire contoured to fit passively on the dental case. B, A wire ligature is passed around the necks of the teeth to hold them tightly together while they are bonded. The wire retainer is held in place with dental floss passed around the contact, and (C) composite resin is flowed onto the cingulum of the teeth, over the wire ends. Note that the retainer wire is up on the cingulum of the teeth to avoid contact with the lower incisors. A Hawley retainer can be worn to stabilize other teeth and maintain vertical control in the presence of a bonded segment of this type.

FIGURE 17-13 An alternative design for a bonded retainer for the maxillary incisors, using a heavier wire. The wire is contoured so that flossing is not impeded, and the bonded attachment areas also serve to keep the bite from deepening, but the patient will have to tolerate more tongue contact with a retainer of this type, and overgrowth of palatal gingiva can become a problem.

A removable retainer by itself is not a good choice for prolonged retention of a central diastema. In troublesome cases, the diastema is closed when the retainer is in place but opens up quickly when it is removed. The tooth movement that accompanies this back-and-forth closure is potentially damaging over a long period.

3. Maintenance of pontic or implant space. A fixed retainer is also the best choice to maintain a space where a bridge pontic or implant eventually will be placed. Using a fixed retainer for a few months reduces mobility of the teeth and often makes it easier to place the fixed bridge that will serve, among other functions, as a permanent orthodontic retainer. If further periodontal therapy is needed after the teeth have been positioned, several months or even years can pass before a bridge is placed, and a fixed retainer is definitely required. Implants should be placed as soon as possible after the orthodontics is completed, so that integration of the implant can occur simultaneously with the initial stages of retention.

The preferred orthodontic retainer for maintaining space for posterior restorations is a heavy intracoronal wire bonded to the adjacent teeth (in shallow preparations if these are future abutment teeth for a bridge; Figure 17-14). Obviously, the longer the span, the heavier the wire should be. Bringing the wire down out of occlusion decreases the chance that it will be displaced by occlusal forces.

FIGURE 17-14 A fixed retainer (sometimes called an A-splint) to maintain space for eventual replacement of a missing second premolar. A shallow preparation has been made in the enamel of the marginal ridges adjacent to the extraction site, and a section of 21 × 25 wire, stepped down away from the occlusion, is bonded as a retainer.

Anterior spaces need a replacement tooth, which can be attached to a removable retainer. This approach guarantees nearly full-time wear and is satisfactory for short periods. After a few months, especially if an implant or permanent bridge will be delayed for a long time while adolescent vertical growth is completed, it is better to place a fixed retainer in the form of a bonded bridge.

4. Keeping extraction spaces closed in adults (see Figure 17-8, A). A fixed retainer is both more reliable and better tolerated than a full-time removable retainer, and spaces reopen unless a retainer is worn consistently. It may be better in adults to bond a fixed retainer on the facial surface of posterior teeth when spaces have been closed, especially when skeletal anchorage has been used to bring posterior teeth forward over large distances.

The major objection to any fixed retainer is that it makes interproximal hygiene procedures more difficult, especially in the lower anterior area. In this sense, there is both bad and good news: there is greater plaque buildup when a multistrand wire is bonded to all the lower anterior teeth than when a heavier round wire is bonded only to the canines, but the wire bonded to all the teeth is more effective in maintaining alignment.11 It is possible to floss between teeth that have a fixed retainer across the interdental contact areas by using a floss-threading device, and the orthodontist should teach and strongly encourage this.

Active Retainers

“Active retainer” is a contradiction in terms, since a device cannot be actively moving teeth and serving as a retainer at the same time. It does happen, however, that relapse or growth changes after orthodontic treatment lead to a need for some tooth movement during retention. This usually is accomplished with a removable appliance that continues as a retainer after it has repositioned the teeth, hence the name. A typical Hawley retainer, if used initially to close a small amount of band space, can be considered an active retainer, but the term usually is reserved for two specific situations: realignment of irregular incisors with spring retainers and management of Class II or Class III relapse tendencies with modified functional appliances.

Realignment of Irregular Incisors: Spring Retainers

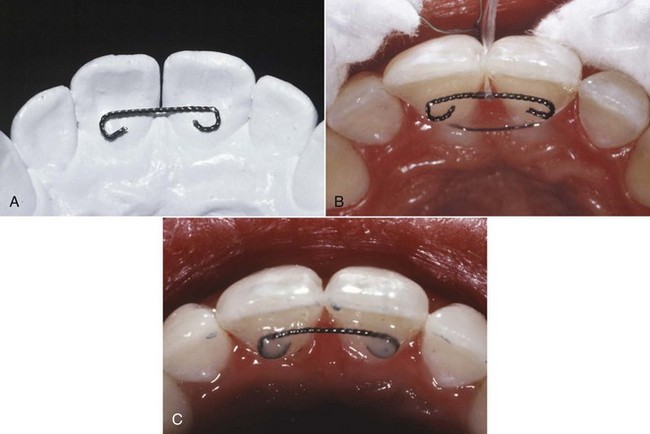

Re-crowding of lower incisors is the major indication for an active retainer to correct incisor position. The shape of the incisor crowns can contribute to re-crowding,12 but the cause of the problem in these cases usually is late mandibular growth that uprighted the incisors. If late crowding has developed, it often is necessary to reduce the interproximal width of lower incisors before realigning them, so that the crowns do not tip labially into an obviously unstable position. Not only does stripping of contacts reduce the mesiodistal width of the incisors, decreasing the amount of space required for their alignment, it also flattens the contact areas, increasing the inherent stability of the arch in this region. If stripping is done cautiously and judiciously, data indicate that long-term periodontal health is not affected by the increase in root proximity that would be an inevitable side effect.13

Interproximal enamel can be removed with either abrasive strips, thin discs in a handpiece, or thin flame-shaped diamond stones. Obviously, enamel reduction should not be overdone, but if necessary, the width of each lower incisor can be reduced up to 0.5 mm on each side without going through the interproximal enamel. If an additional 2 mm of space can be gained, reducing each incisor 0.25 mm per side, it is usually possible to realign these teeth after moderate relapse.

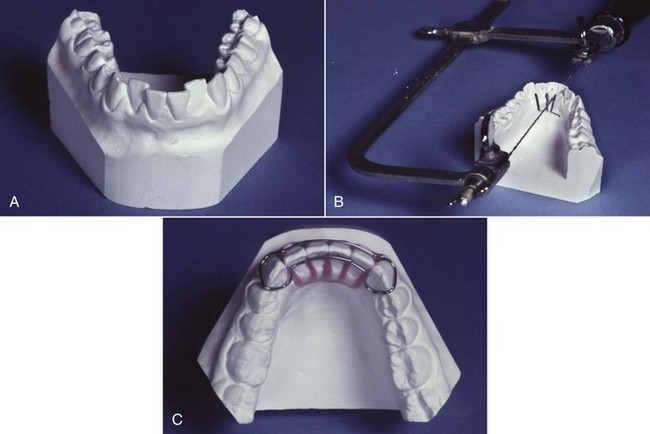

If the irregularity is modest, a canine-to-canine clip-on is usually the active retainer used to realign crowded incisors (Figure 17-15). The steps in making such an active retainer are: (1) reduce the interproximal width of the incisors and apply topical fluoride to the newly exposed enamel surfaces; (2) prepare a laboratory model, on which the teeth can be reset into alignment; and (3) fabricate a canine-to-canine clip-on appliance to fit the model (Figure 17-16).

FIGURE 17-15 Removal of interproximal enamel to facilitate alignment of crowded lower incisors. A and B, Before and after use of a carbide-coated strip to remove enamel. The surfaces are polished after the stripping is completed. Topical fluoride should be applied immediately after stripping procedures because the fluoride-rich outer layer of enamel has been removed. C, A canine-to-canine clip-on retainer (now; initially an aligner) immediately upon placement. It was made as described in Figure 17-16 and must be worn full time until the teeth are back in alignment.

FIGURE 17-16 Steps in the fabrication of a canine-to-canine clip-on appliance to realign lower incisors. A, Re-crowded incisors in a patient who decided to “take a vacation” from retainer wear. After the teeth have been stripped appropriately, an impression is made for a laboratory cast. B, A saw-cut is made beneath the teeth through the alveolar process to the distal of the lateral incisors, and cuts are made up to but not through the contact points. C, The incisor teeth are broken off the cast and broken apart at the contact points, creating individual dies, and the cast is trimmed to provide space for resetting the teeth; then the teeth are reset in wax in proper alignment and 28 mil steel wire is contoured around the labial and lingual surface of the teeth as shown, with the wire overlapping behind the central incisors. A covering of acrylic is added over the wire, completing the aligner, which then looks exactly like a canine-to-canine clip-on retainer. As an aligner, however, full-time wear is essential.

If there is more than a modest degree of relapse, however, a fixed appliance for retreatment must be considered. With bonded brackets on the lower arch from premolar to premolar, space can be opened and superelastic NiTi wires can be used to bring the incisors back into alignment quite efficiently (Figure 17-17). If the incisors are advanced toward the lip when this is done, a bonded lingual retainer should be placed before the brackets are removed. Permanent retention obviously will be required after the realignment.

FIGURE 17-17 For this patient, who was concerned about crowding of lower incisors several years after orthodontic treatment, excessive stripping of interproximal enamel would have been required to gain realignment with a clip-on removable appliance. In that circumstance, a partial fixed appliance with bonded brackets only on the segment to be realigned is the most practical approach. A, Bonded appliance from first premolar to first premolar, with a coil spring on 16 steel wire to open space for the rotated and crowded right central incisor. B and C, Alignment of the incisors on rectangular NiTi wire after space was opened, which was completed 4 months after treatment began. At this point a fixed lingual retainer can be bonded before the brackets and archwire are removed.

Correction of Occlusal Discrepancies: Modified Functional Appliances as Active Retainers

It is possible to describe an activator as consisting of maxillary and mandibular retainers joined by an interocclusal bite block. Although even the simplest activator is more complex than that (see Chapter 13), the description does illustrate the potential of a modified functional appliance to simultaneously maintain the position of teeth within the arches while altering, at least minimally, the occlusal relationships.

A typical use for an activator or bionator as an active retainer would be a male adolescent who had slipped back 2 to 3 mm toward a Class II relationship after early correction. It would look exactly like the functional appliance retainer (see Figure 17-4), except that the bite was taken to advance the mandible the 2 to 3 mm needed to correct the occlusion. If the patient still is experiencing some vertical growth (almost all male adolescents under age 18 fall into this category), it may be possible to recover the proper occlusal position of the teeth. Differential anteroposterior growth is not necessary to correct a small occlusal discrepancy—tooth movement is adequate—but some vertical growth is required to prevent downward and backward rotation of the mandible. For all practical purposes, this means that a functional appliance as an active retainer can be used in teenagers but is of no value in adults. Stimulating skeletal growth with a device of this type simply does not happen in adults, at least to a clinically useful extent.

The use of a functional appliance as an active retainer differs from its use as a pure retainer. As a retainer, the object is to control growth, and tooth movement is largely an undesirable side effect. In contrast, an active retainer is expected primarily to move teeth—no significant skeletal change is expected. An activator or bionator as an active retainer is indicated if not more than 3 mm of occlusal correction is sought. Over this distance, tooth movement as a means of correction is a possibility. The correction is achieved by restraining the eruption of maxillary teeth posteriorly and directing the erupting mandibular teeth anteriorly.

References

1. Littlewood, SJ, Millett, DT, Doubleday, B, et al. Orthodontic retention: a systematic review. J Orthod. 2006;33:205–212.

2. Joondeph, DR. Stability, retention, and relapse. In Graber TM, Vararsdall RL, Vig KWL, eds.: Orthodontics: Current Principle and Techniques, 5th ed, St. Louis: Mosby, 2012.

3. Reitan, K. Tissue rearrangement during the retention of orthodontically rotated teeth. Angle Orthod. 1959;29:105–113.

4. Behrents, RG. A treatise on the continuum of growth in the aging craniofacial skeleton. Ann Arbor, Mich: University of Michigan Center for Human Growth and Development; 1984.

5. Nanda, RS, Nanda, SK. Considerations of dentofacial growth in long-term retention and stability: is active retention needed? Am J Orthod Dentofac Orthop. 1992;101:297–302.

6. Tynelius, GE, Bondemark, L, Lilja-Karlander, E. Evaluation of orthodontic treatment after 1 year of retention—a randomized controlled trial. Eur J Orthod. 2010;32:542–547.

7. Mollov, ND, Lindauer, SJ, Best, AM, et al. Patient attitudes toward retention and perceptions of treatment success. Angle Orthod. 2010;80:468–473.

8. Rinchuse, DJ, Miles, PG, Sheridan, JJ. Orthodontic retention and stability: a clinical perspective. J Clin Orthod. 2007;41:125–132.

9. Zachrisson, BU. Long-term experience with bonded retainers: update and clinical advice. J Clin Orthod. 2007;41:728–737.

10. Booth, FA, Edelman, JM, Proffit, WR. Twenty-year follow-up of patients with permanently bonded mandibular canine-to-canine retainers. Am J Orthod Dentofac Orthop. 2008;133:70–76.

11. Al-Nimri, K, Al Habashneh, R, Obeidat, M. Gingival health and relapse tendency: a prospective study of two types of lower fixed retainers. Australian Orthod J. 2009;25:142–146.

12. Shah, AA, Elcock, C, Brook, AH. Incisor crown shape and crowding. Am J Orthod Dentofac Orthop. 2003;123:562–567.

13. Zachrisson, BU, Nyøygaard, L, Mobarak, K. Dental health assessed more than 10 years after interproximal enamel reduction of mandibular anterior teeth. Am J Orthod Dentofac Orthop. 2007;131:162–169.