Leg ulcers

Leg ulcers affect 1% of the adult population and account for 1% of dermatology referrals. They are twice as common in women as in men and are a major burden on the health service. One half is venous, a tenth arterial and a quarter ‘mixed’ – due to venous and arterial disease. The remainder are due to rare causes.

Venous disease

Damage to the venous system of the leg results in pigment change, eczema, oedema, fibrosis and ulceration.

Aetiopathogenesis

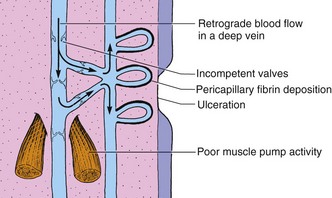

The superficial low-pressure venous system of the leg is connected to the deep higher pressure veins by perforating veins. Blood flow relies on the pumping action of surrounding muscles and the integrity of valves. Valve incompetence, occasionally congenital but usually due to damage by thrombosis or infection, results in a rise in capillary hydrostatic pressure and permeability (Fig. 1). Fibrin is deposited as a pericapillary cuff, interfering with diffusion of nutrients and resulting in disease.

Clinical presentation

Venous disease usually starts in middle age and continues into later life. It is commoner in women and is predisposed to by obesity and venous thrombosis. Varicose veins are often present, but are not essential. The syndrome progresses through stages:

Heaviness and oedema: early symptoms. The legs feel heavy and swell.

Heaviness and oedema: early symptoms. The legs feel heavy and swell.

Discoloration: brown haemosiderin deposits from extravasated red cells. Telangiectasia and white lacy scars (atrophie blanche) occur at the ankle (Fig. 2).

Discoloration: brown haemosiderin deposits from extravasated red cells. Telangiectasia and white lacy scars (atrophie blanche) occur at the ankle (Fig. 2).

Eczema: commonly occurs (p. 38), often complicated by allergic or irritant contact dermatitis.

Eczema: commonly occurs (p. 38), often complicated by allergic or irritant contact dermatitis.

Lipodermatosclerosis: fibrosis of the dermis and subcutis around the ankle results in firm induration.

Lipodermatosclerosis: fibrosis of the dermis and subcutis around the ankle results in firm induration.

Ulceration: often follows minor trauma, and typically affects the medial and, to a lesser extent, the lateral malleolus (Fig. 3). Neglected ulcers enlarge and may encircle the lower leg. Initially, venous ulcers are exudative but, under favourable conditions, they granulate and enter a healing phase in which the epidermis grows in from the sides and from small epithelial islands in the middle. Healing is invariably slow, often taking months. Some large ulcers never heal.

Ulceration: often follows minor trauma, and typically affects the medial and, to a lesser extent, the lateral malleolus (Fig. 3). Neglected ulcers enlarge and may encircle the lower leg. Initially, venous ulcers are exudative but, under favourable conditions, they granulate and enter a healing phase in which the epidermis grows in from the sides and from small epithelial islands in the middle. Healing is invariably slow, often taking months. Some large ulcers never heal.

Post-ulcer leg: fibrosis may lead to a slender sclerosed ankle.

Post-ulcer leg: fibrosis may lead to a slender sclerosed ankle.

Differential diagnosis and complications

Venous ulcers can be differentiated from other ulcers (Table 1) by history, position and additional signs. Arterial ulcers are deep, painful and gangrenous, and situated on the foot or mid-shin. Complications of venous ulcers are common and include the following:

Infections. Bacteria invariably colonize ulcers. Systemic antibiotics are needed only for overt infection, as suggested by a purulent discharge, a rapidly advancing ulcer edge, cellulitis or septicaemia.

Infections. Bacteria invariably colonize ulcers. Systemic antibiotics are needed only for overt infection, as suggested by a purulent discharge, a rapidly advancing ulcer edge, cellulitis or septicaemia.

Lymphoedema. Lymphatic drainage is impaired in legs with chronic venous ulcers, adding to the oedema.

Lymphoedema. Lymphatic drainage is impaired in legs with chronic venous ulcers, adding to the oedema.

Contact dermatitis. Contact sensitivity to topical medicaments and bandages frequently develops, especially to lanolin, neomycin, rubber chemicals and preservatives. Allergic contact dermatitis can resemble an exacerbation of venous eczema and is suspected if there is generalized secondary spread. Some local therapies, and the ulcer exudate itself, are irritant.

Contact dermatitis. Contact sensitivity to topical medicaments and bandages frequently develops, especially to lanolin, neomycin, rubber chemicals and preservatives. Allergic contact dermatitis can resemble an exacerbation of venous eczema and is suspected if there is generalized secondary spread. Some local therapies, and the ulcer exudate itself, are irritant.

Malignant change. Rarely, squamous cell carcinoma develops in an ulcer.

Malignant change. Rarely, squamous cell carcinoma develops in an ulcer.

Table 1 Causes of leg ulceration

| Division | Condition |

|---|---|

| Venous disease | Damaged valves (e.g. deep vein thrombosis), clotting disorder, congenital valve incompetence |

| Arterial disease | Atherosclerosis, Buerger’s disease, polyarteritis nodosa |

| Small vessel disease | Diabetes mellitus, rheumatoid arthritis, vasculitis, sickle cell disease, hypertension |

| Infection | Tuberculosis, Buruli ulcer (p. 50), mycetoma (p. 60), syphilis (p. 120) |

| Neuropathy | Diabetes mellitus, leprosy, syphilis, syringomyelia |

| Neoplasia | Squamous cell carcinoma, Kaposi’s sarcoma, malignant melanoma |

| Trauma | Direct injury, artefact |

| Unknown | Pyoderma gangrenosum (p. 89), necrobiosis lipoidica (p. 84) |

Management

Treatment of a leg ulcer is long term and progress usually slow. The initial examination includes palpation of peripheral pulses and an assessment of contributing factors such as obesity, anaemia, cardiac failure and arthritis. Doppler studies, to exclude coexisting arterial disease, are essential when compression bandaging is proposed (p. 21). Treatments are as follows:

Compression bandages. These reduce oedema and promote venous return. Bandages are applied from the toes to the knee. Self-adhesive bandages (e.g. Coban) are preferred, and are left on for 2–7 days. A four-layer bandage technique uses a layer of orthopaedic wool (e.g. Softexe), a standard crepe (e.g. Setocrepe), an elasticated bandage (e.g. Elset) and an elasticated cohesive bandage (e.g. Coban). Arterial disease precludes compression bandaging. Once an ulcer has healed, a toe-to-knee compression stocking maintains venous return.

Compression bandages. These reduce oedema and promote venous return. Bandages are applied from the toes to the knee. Self-adhesive bandages (e.g. Coban) are preferred, and are left on for 2–7 days. A four-layer bandage technique uses a layer of orthopaedic wool (e.g. Softexe), a standard crepe (e.g. Setocrepe), an elasticated bandage (e.g. Elset) and an elasticated cohesive bandage (e.g. Coban). Arterial disease precludes compression bandaging. Once an ulcer has healed, a toe-to-knee compression stocking maintains venous return.

Elevation, exercise and diet. Some doctors recommend rest with leg elevation. Walking is encouraged, as is dieting for obese individuals and ankle exercises to maintain joint mobility.

Elevation, exercise and diet. Some doctors recommend rest with leg elevation. Walking is encouraged, as is dieting for obese individuals and ankle exercises to maintain joint mobility.

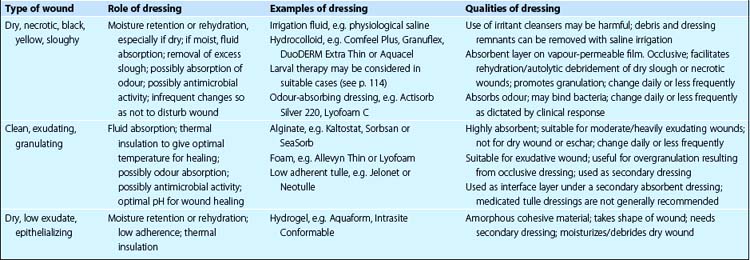

Topical therapy. Table 2 shows what to use and when to use it. Venous eczema is treated with a mild to moderate potency steroid or an emollient.

Topical therapy. Table 2 shows what to use and when to use it. Venous eczema is treated with a mild to moderate potency steroid or an emollient.

Oral therapy. Adequate analgesia is vital. Diuretics are given for cardiac oedema, and antibiotics for overt infection. An anabolic steroid, stanozolol (Stromba), may help lipodermatosclerosis, but side-effects (fluid retention, jaundice) limit its use. Oxerutins (Paroven) reduce capillary permeability, relieving oedema.

Oral therapy. Adequate analgesia is vital. Diuretics are given for cardiac oedema, and antibiotics for overt infection. An anabolic steroid, stanozolol (Stromba), may help lipodermatosclerosis, but side-effects (fluid retention, jaundice) limit its use. Oxerutins (Paroven) reduce capillary permeability, relieving oedema.

Surgery. Vein surgery may prevent problems in younger patients, but is rarely applicable in the elderly. Split skin grafts or pinch grafts (from the thigh) are of limited use. However, experimental culturing of keratinocytes in a ‘skin equivalent’, to use as a graft, is promising and gives rapid pain relief (p. 114).

Surgery. Vein surgery may prevent problems in younger patients, but is rarely applicable in the elderly. Split skin grafts or pinch grafts (from the thigh) are of limited use. However, experimental culturing of keratinocytes in a ‘skin equivalent’, to use as a graft, is promising and gives rapid pain relief (p. 114).

Arterial disease

Lower leg ischaemia and ulceration can result from arterial disease. Ischaemia presents with claudication, coldness of the foot, loss of hair, toenail dystrophy and dusky cyanosis. Deep, sharply defined ulcers occur on the foot or mid-shin (Fig. 4). Pulses in the legs are absent or reduced. Buerger’s disease, seen in young male smokers, is a severe form of arterial disease.

Doppler studies and contrast angiography define the arterial lesions, which may be amenable to vascular reconstruction or angioplasty. Compression bandaging is contraindicated if the ABPI is <0.5 but reduced compression may be used under supervision for ABPIs of 0.6–0.8.

Other causes of leg ulceration

Vasculitic ulcers start as purpura, but become necrotic and punched out (see Table 1). Peripheral neuropathic ulcers and diabetes can produce ulcers on the feet (Fig. 5). Buruli ulcer and deep mycoses are important in the tropics.