CHAPTER 14 Assessment of the Dentition

Tooth assessment is used to determine whether the client's need for a biologically sound and functional dentition is met; assessment is related to the client's human needs for freedom from pain and for wholesome facial image. Tooth assessment and its documentation initially occur during the assessment phase of the dental hygiene process and are updated during the implementation and evaluation phases of dental hygiene care. The dental hygienist's tooth assessment goals are to recognize and document signs of developmental anomalies and acquired tooth damage and to call them to the dentist's attention, thus optimizing client care. It is essential that documentation of findings in the client record is accurate and complete because its purposes are to do the following:

Enhance communication with the client, other members of the oral healthcare team, and third-party payers, such as insurance companies and health maintenance organizations

Enhance communication with the client, other members of the oral healthcare team, and third-party payers, such as insurance companies and health maintenance organizations Contain a detailed history of the client's clinical examination findings, dental diagnosis, and treatment for quality assurance audits

Contain a detailed history of the client's clinical examination findings, dental diagnosis, and treatment for quality assurance auditsDOCUMENTATION

Dental charting is the graphic representation of the condition of the client's teeth observed on a specific date. The data recorded are based on clinical and radiographic assessments and the client's reported symptoms. The exact location and condition of all teeth and restorations, including normal and abnormal findings, are documented on a dentition chart as part of the client's permanent record.

An ideal dental charting form contains sufficient space for initial recording of data as well as for successive findings and can be easily interpreted. To facilitate continuity, sequencing, and ongoing documentation of care, the dentition charting form needs to be available for reference during all appointments.

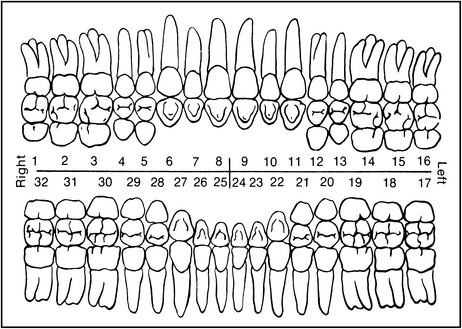

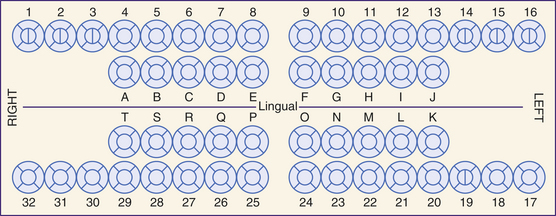

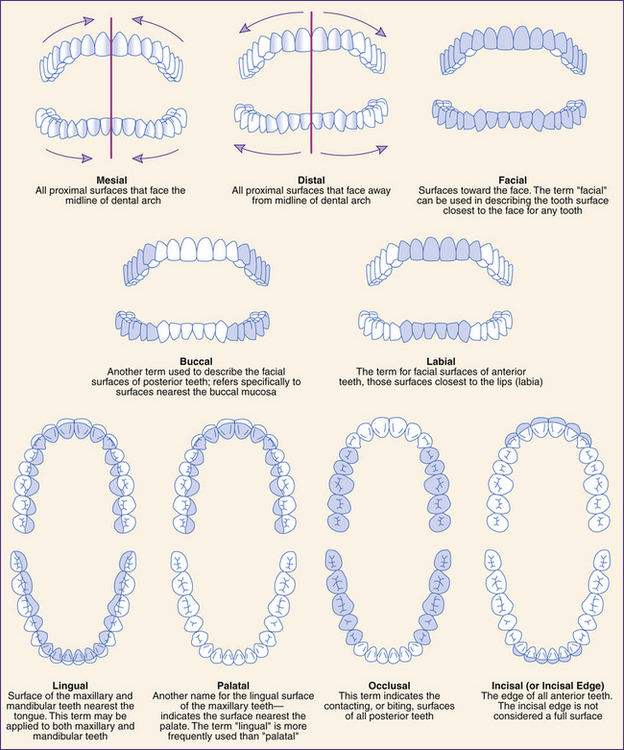

The most commonly used forms present anatomic or geometric tooth representations (Figure 14-1). In anatomic diagrams, the illustrations resemble actual teeth. The crown and root anatomy of each tooth is usually provided with facial views (tooth surfaces toward the face), occlusal views (biting or chewing surfaces), and lingual views (surfaces toward the tongue). In a geometric diagram, each tooth is represented by a circle that is divided into five parts to represent each tooth surface (Figure 14-2). In all charting designs, the teeth are arranged as though one is looking in the mouth of the client. Thus, the right side of the mouth is on the left side of the chart and the left side of the mouth is on the right side of the chart.

Figure 14-1 Example of an anatomic chart using the Universal Numbering System.

(Courtesy Colwell Systems, a division of Patterson Dental, St Paul, Minnesota.)

Figure 14-2 Example of a geometric chart using the Universal Numbering System.

(Courtesy Colwell Systems, a division of Patterson Dental, St Paul, Minnesota.)

Computer-Assisted Charting

To support paperless oral healthcare records, computer-assisted charting software is available. The charting form is a computer image using either anatomic or geometric image formats. The charting information is entered into the computer via a keyboard, mouse, or voice-activated program. The voice-activated approach promotes infection control principles and eliminates the need for an assistant. Although the data are stored in the computer, a completed charting form can be printed out when a hard copy is needed.

Quadrant and Sextant Classification

To facilitate communication about specific dentition areas and individual teeth, the dentition is divided into quadrants and sextants, and each tooth is divided into specific surfaces and zones.

Quadrants

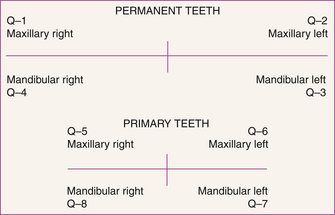

If one were to draw an imaginary line dividing the client's face into two equal halves longitudinally, then the maxillary and mandibular arches of the mouth would be divided into two mirror images or halves. This imaginary longitudinal line that bisects the client's face is referred to as the midline. If one were to draw horizontally a second imaginary line that divides the upper jaw (the maxillary arch) from the lower jaw (the mandibular arch), the combination of the imaginary horizontal and vertical midlines would divide the client's mouth into four equal sections termed quadrants (Q) (Figure 14-3). Each quadrant contains either five or eight teeth, depending on whether the client has primary or permanent dentition. Permanent dentition quadrants are numbered 1 through 4, and those of the primary dentition 5 through 8. The maxillary right is referred to as quadrant 1 in the permanent dentition or quadrant 5 in the primary dentition. Continuing in a clockwise pattern around the dentition, the maxillary left is designated as quadrant 2 (permanent) or quadrant 6 (primary). The mandibular left is referred to as quadrant 3 (permanent) or quadrant 7 (primary), and the mandibular right is designated as quadrant 4 (permanent) or quadrant 8 (primary). In the event that the client has a mixed dentition (both primary and permanent teeth), each tooth is identified individually, based on whether it is a primary or a permanent tooth, and is prefaced with quadrant 1 through 4 if it is a permanent tooth or 5 through 8 if it is a primary tooth.

Sextants

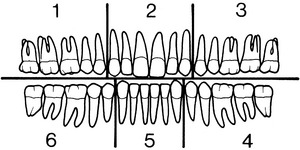

Another means of dividing the primary and permanent dentition into sections is created by drawing additional imaginary lines to create divisions between the front (anterior) and the back (posterior) teeth. Dividing the dentition in this manner creates six areas called sextants (S). Each anterior sextant contains incisors and canines, and each posterior sextant contains premolars or molars. Like quadrants, sextants are numbered clockwise beginning at the client's maxillary right (Figure 14-4).

Tooth Surfaces and Zones (see Chapter 26)

The differentiation of tooth surfaces and zones provides a means of pinpointing specific areas of the tooth for accurate assessment, charting, treatment, and evaluation. The midline is an imaginary line drawn longitudinally between the central incisors of the maxilla and mandible dividing the arches into two equal halves. Each tooth surface located closest to the midline is called the mesial surface and each tooth surface located farthest from the midline is called the distal surface. Overall, there are six tooth surfaces (Figure 14-5):

Figure 14-5 Classification of tooth surfaces.

(Adapted from Wootton D: The art of dental scaling, Burlington, 1991, University of Vermont.)

Tooth Zones

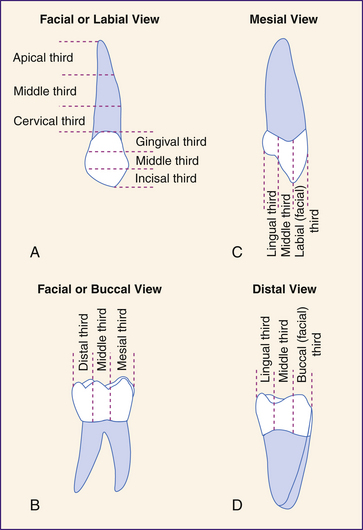

Teeth also are divided into zones of imaginary thirds (Figure 14-6). The root is divided into thirds: the apical third (the area involving the root tip or apex), the middle third, and the cervical third (the area closest to the “neck” of the tooth crown). The tooth crown can be divided into the following three directions:

Cervico-occlusal division: Dividing the tooth crown horizontally, from cervical to occlusal areas, creates the occlusal (for posterior teeth, or incisal for anterior teeth), middle, and gingival thirds (see Figure 14-6, A).

Cervico-occlusal division: Dividing the tooth crown horizontally, from cervical to occlusal areas, creates the occlusal (for posterior teeth, or incisal for anterior teeth), middle, and gingival thirds (see Figure 14-6, A). Mesiodistal division: Dividing the crown vertically on the facial or lingual surface, from mesial to distal, creates the mesial, middle, and distal thirds (see Figure 14-6, B).

Mesiodistal division: Dividing the crown vertically on the facial or lingual surface, from mesial to distal, creates the mesial, middle, and distal thirds (see Figure 14-6, B). Faciolingual (or buccolingual) division: Dividing the crown vertically on the mesial or distal view creates the facial (in lieu of labial for anterior teeth or buccal for posterior teeth), middle, and lingual thirds (see Figure 14-6, C and D).

Faciolingual (or buccolingual) division: Dividing the crown vertically on the mesial or distal view creates the facial (in lieu of labial for anterior teeth or buccal for posterior teeth), middle, and lingual thirds (see Figure 14-6, C and D).Types of Teeth (see Chapter 26)

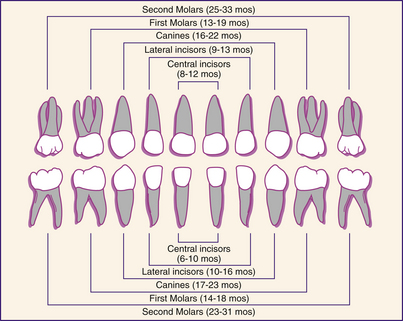

Humans have two sets of natural teeth, commonly referred to as the primary and the permanent dentitions. The primary dentition is made up of 20 teeth, five in each quadrant: two incisors, one canine, and two molars.

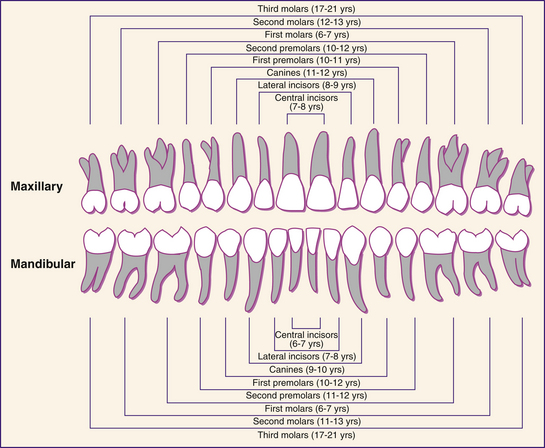

The full permanent, or secondary, dentition has 32 teeth, eight in each quadrant: two incisors, one canine, two premolars, and three molars. The functions of the individual tooth types are similar in the primary and the permanent dentition. The classification of primary and permanent teeth along with age of eruption are provided in Figures 14-7 and 14-8.

TOOTH NUMBERING SYSTEMS

Tooth numbering systems were developed to simplify the task of identifying individual teeth without using their full name designations. Such systems are essential for charting and recording procedures. The two most commonly used are the Universal Numbering System and the International Numbering System.

Universal Numbering System

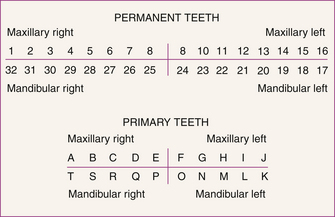

The Universal Numbering System, officially adopted by the American Dental Association, provides a standard sequential numbering system for all permanent teeth numbered 1 through 32. The maxillary numbering follows clockwise from the maxillary third molar (designated as tooth 1) to the left maxillary third molar (designated tooth 16). The mandibular numbering follows clockwise from the left mandibular third molar (designated as tooth 17), to the right mandibular third molar, designated as tooth 32 (Figure 14-9). The primary teeth are identified by capital letters A to T. In the maxilla, the maxillary right second molar is designated as tooth A across the arch to the left maxillary second molar designated as tooth J. The left mandibular second molar is designated by the letter K; following across the mandibular arch, the mandibular right second molar is designated by the letter T (see Figure 14-9).

International Numbering System (Federation Dentaire International)

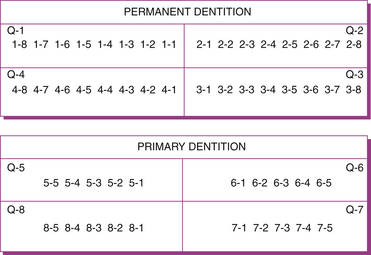

The International Numbering System uses a two-digit system to identify each tooth. The first digit indicates the quadrant in which the tooth is located, and the second digit identifies the specific tooth. For quadrant designations, numbers 1 to 4 are used to specify permanent quadrants, and numbers 5 to 8 to designate primary quadrants. The second digit identifies the specific tooth in the quadrant: the numbers 1 to 8 are used for permanent teeth, and the numbers 1 to 5 for primary teeth. In each dentition, tooth 1 is the central incisor with the numbering progressing from the midline to the posterior teeth (Figure 14-10). The pronunciation of the International system is emphasized by the hyphenated notation; for example, “1-6” is pronounced “one six,” rather than “sixteen.”

DEVELOPMENTAL ANOMALIES AND ACQUIRED TOOTH DAMAGE

Developmental Anomalies

Developmental anomalies arise from a disturbance in the stages of tooth development (odontogenesis), causing one or more of the tooth bud tissues to be disrupted. These disturbances may be the result of local, systemic, or hereditary factors. The extent of the disturbance manifestation is dependent on the dental development stage at which the disruption occurs and the duration and nature of the assault.

Dental anomalies include anomalies of the number of teeth and anomalies of dental tissues. The following discussion briefly describes the more frequently noted dental anomalies. (Tooth anomalies with variation in root form are presented in Chapter 26.)

Anomalies of Number of Teeth

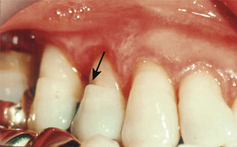

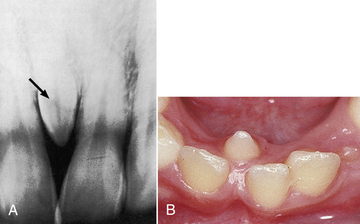

Hyperdontia is the presence of extra teeth beyond the normal complement. Hyperdontia is commonly referred to as “supernumerary” or “supplemental” teeth. Supernumerary teeth are extra teeth of abnormal shape, whereas supplemental teeth are extra teeth of normal shape. When an extra tooth occurs in the midline between the maxillary anterior incisors, it is referred to as a mesiodens (Figure 14-11). These supernumerary teeth are usually misshapen, small, and peglike. A natal tooth is a supernumerary tooth that erupts before birth, and a neonatal tooth is a supernumerary tooth that erupts shortly after birth.1

Figure 14-11 Mesiodens (arrow). A, Radiographic appearance. B, Clinical appearance.

(From Regezi JA, Sciubba JJ: Oral pathology: clinical-pathologic correlations, ed 5, St Louis, 2008, Saunders.)

Hypodontia is the absence of one or more teeth and also may be called anodontia. The failure of all teeth to develop is complete anodontia, and the absence of one or several teeth is partial anodontia. Anodontia is usually associated with defects of ectodermal structures, such as are found with the disorder ectodermal dysplasia.

Although complete anodontia is extremely rare, partial anodontia is more common. The teeth most frequently observed as congenitally missing are third molars, followed sequentially by maxillary lateral incisors and mandibular premolars. The teeth least frequently absent are first permanent molars.

Anomalies of the Dental Tissues

Tooth anomalies can be subdivided into several categories: those affecting the total tooth and those affecting the individual dental tissues, including enamel, dentin, cementum, and pulp.

Anomalies of the Whole Tooth

Macrodontia refers to larger than normal teeth. These teeth may be larger in width, length, or height.1 Microdontia is a developmental anomaly in which the teeth are smaller than normal. This condition may affect one tooth, several teeth, or all teeth within the dentition. Many supernumerary teeth are small and can be classified as microdonts (Figure 14-12).

In gemination, a large tooth results from the splitting of a single tooth germ that attempts to form two teeth (Figure 14-13). This twinning usually results in a partially or completely divided crown attached to a single root with one canal.1

Dens in dente is defined as a tooth within a tooth (Figure 14-14). It is caused by invagination of the enamel organ during development and is most frequently observed on the lingual aspect of the maxillary lateral incisors. A deep crevice usually runs between the oral and the inner surface of the tooth where the anomaly is found.1 This crevice increases the likelihood of early dental caries; consequently a preventive restoration may be considered to prevent dental caries.

Figure 14-14 Radiograph of dens in dente in maxillary lateral incisor.

(From Ibsen OAC, Phelan JA: Oral pathology for the dental hygienist, ed 5, St Louis, 2009, Saunders.)

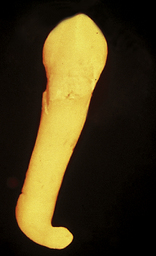

Dilaceration is the abnormal distortion of a crown or root caused by trauma during tooth formation. It is usually manifested as a severely angulated root (Figure 14-15). Extraction of a tooth with a dilacerated root often creates a treatment problem for the dentist because of the root angulation.1

Anomalies of Enamel Formation

An insult to ameloblasts during tooth formation may result in abnormal enamel development, referred to generally as enamel dysplasia. Enamel dysplasia encompasses two types of abnormal enamel development: enamel hypoplasia and enamel hypocalcification.

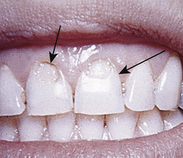

Enamel hypoplasia is the result of a disturbance of the ameloblasts during matrix formation that produces a pitted or rough, striated enamel surface (Figure 14-16). Enamel hypocalcification is a defect occurring in the enamel as the result of a disturbance during mineralization. The clinical appearance of enamel hypocalcification is that of white spotting of the enamel surface; however, the enamel surface is generally smooth in texture.

Figure 14-16 Enamel hypoplasia.

(From Ibsen OAC, Phelan JA: Oral pathology for the dental hygienist, ed 5, St Louis, 2009, Saunders.)

Many factors—local (e.g., trauma), systemic (e.g., diseases, nutritional deficiencies, excess systemic fluoride), hereditary, and idiopathic (unknown)—may cause anomalies of enamel formation. When excessive amounts of systemic fluoride are responsible for enamel hypoplasia or enamel hypocalcification, this condition is classified as dental fluorosis. This condition may range from mild fluorosis, associated with white flecking, to severe situations in which the teeth are deeply pitted or brown stained. Clients who live in a rural setting may be candidates for fluoride supplements; however, before initiation of a supplement program it is important to determine the fluoride concentration in the drinking water through analysis of water samples. Water samples can be analyzed by local health departments (see Chapter 31).

Congenital syphilis is another, now rare, cause of enamel hypoplasia, and several hypoplastic characteristics are often associated with this condition. “Hutchinson's incisors” is the term used to denote the notched or screwdriver appearance of syphilitic incisor teeth (Figure 14-17, A). When the lateral incisors display a conical shape, they are often referred to as “peg-laterals.” Not all peg-laterals occur as the result of syphilis. A peg-lateral is, in essence, a microdont and can stem from a variety of other causes. The term “mulberry molars” is used to describe the mottled mulberry-shaped molars also associated with congenital syphilis2 (Figure 14-17, B).

Figure 14-17 Syphilitic enamel hypoplasia. A, Hutchinson's incisors. B, Mulberry molars.

(Courtesy Dr. George Blozis. From Ibsen OAC, Phelan JA: Oral pathology for the dental hygienist, ed 5, St Louis, 2009, Saunders.)

Amelogenesis imperfecta is a form of enamel dysplasia resulting from hereditary factors. Many inheritance patterns are associated with this disorder, such as autosomal dominant, recessive, or X-linked. Amelogenesis imperfecta is the partial or total malformation of enamel. The dentin and pulp of these teeth develop normally, but the enamel is easily chipped or worn away.

Several anomalies involving enamel are not classified as enamel dysplasia; two of these are enamel pearls (see Chapter 26) and dens evaginatus. Dens evaginatus, also referred to as tuberculated cusp, is a small mass of enamel or accessory cusp projecting on the occlusal surface of molars and premolars (Figure 14-18). It is believed to form from an outpouching (evagination) of the enamel epithelium during the early stages of odontogenesis. The tissue mass contains normal pulp and is subject to occlusal wear, risking exposure of the evaginated pulp chamber.3

Talon cusp is an extra well-delineated cusp found on the lingual surfaces of maxillary and mandibular anterior teeth. It was thought that this cusp resembled an eagle's talon, and it was named accordingly (Figure 14-19). The talon cusp has well-developed enamel and dentin and contains a pulp horn.1

Anomalies of Dentin Formation

Dentinogenesis imperfecta is the irregular formation or absence of dentinal development. Dentinogenesis imperfecta is associated with a dominant inherited disorder characterized by faulty formation of connective tissues. The dentin displays a softer than normal consistency as a result of increased water and organic content. Enamel formation occurs normally, but the enamel easily breaks or chips away, resulting in tooth attrition and dentinal hypersensitivity. Dental treatment usually includes placement of crowns to preserve existing crown structure.

Dentin dysplasia is a mesenchymal dysplasia and differs from dentinogenesis imperfecta in that the enamel does not readily chip away. The teeth exhibit normal color and little evidence of attrition. However, teeth with dentin dysplasia show retarded root formation and a lack of supporting bone. The lack of periodontal support may have serious periodontal implications; therefore referral to a periodontist is recommended.

Anomalies of Pulp Formation

Taurodontism, meaning bull-like teeth, is an inherited phenomenon and thus is genetically determined (Figure 14-20). The crowns of these teeth develop normally; however, the pulp chambers are much enlarged at the expense of the dentinal walls.1

Acquired Tooth Damage∗ (see Chapter 23)

Acquired tooth damage can be caused by any process that results in a loss of the integrity of the tooth surface. The most common form of acquired tooth damage is dental caries, an infectious disease caused by bacteria that live in the plaque biofilm and attach to teeth. Other common forms of tooth damage (attrition, abrasion, erosion, and fracture) are the result of mechanical or chemical assault to the tooth structure.

Attrition

Dental attrition is the tooth-to-tooth wear of the dentition. All teeth wear from opposing tooth contact. Excessive wear is pathologic and may be caused by bruxism, grinding, or clenching, discussed later in this chapter (Figure 14-21). The restoration of teeth with excessive attrition may include the complete tooth coverage offered by a crown.

Abrasion

Dental abrasion, pathologic tooth wear caused by a foreign substance, is commonly seen as a result of traumatic toothbrushing and appears as notches worn into the teeth near the gumline (Figure 14-22).

Erosion

Dental erosion, the loss of tooth surface as a result of chemical agents, has recently received considerable attention because of the prevalence of acid reflux disease, morning sickness, anorexia, and bulimia. Excessive vomiting can be associated with eating disorders as the individual strives for weight loss. The repeated regurgitation of stomach acids through the oral cavity results in the dissolution of the dental tissues on the lingual and incisal or occlusal surfaces of the maxillary teeth. Tooth erosion also results from habits such as sucking on lemons or holding mouth fresheners, cough drops, or candies in the mucobuccal fold. The erosive action of these chemicals causes local destruction of tooth enamel (Figure 14-23).

Abfraction

Abfraction is a cervical stress lesion that is manifested as a V- or wedge-shaped defect at the cementoenamel junction (CEJ) (Figure 14-24). It is believed that abfraction defects are caused by “eccentrically applied” occlusal forces, which cause tooth flexure and resulting cervical wear.4

Tooth Fracture

Tooth fractures may range from small chips of the enamel to breaks that penetrate deeply into the tooth (Figure 14-25). Minor enamel fractures often require nothing more than the polishing of rough surfaces. More severe fractures require various levels of restoration. Some fractured teeth may not be restorable and, as a result, require removal.

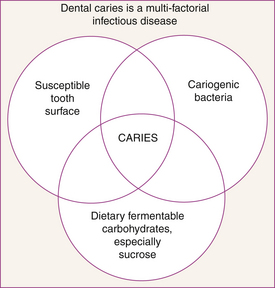

Dental Caries

Dental caries is an infectious and transmissible disease caused by bacteria and characterized by the acid dissolution of enamel and the eventual breakdown of the more organic, inner dental tissues. Primary factors involved in dental caries are bacteria, a tooth surface, and dietary fermentable carbohydrates (Figure 14-26). Streptococcus mutans, Streptococcus sobrinus, and Lactobacillus species are the bacteria identified as the primary causative agents in this process, which leads to cavitation and possible tooth loss. These bacteria metabolize dietary fermentable carbohydrates (sugars and cooked starch) to produce acids. These acids diffuse into the tooth to dissolve the calcium and phosphate minerals (carbonated hydroxyapatite), a process called demineralization. If the acid attacks are infrequent and of short duration, saliva can assist in repairing the damage by neutralizing the acid and replacing minerals and fluoride lost from the tooth. This process is called remineralization. If, however, the flow of saliva is low, the bacterial level is high, and the frequency of client snacking is high, the tooth mineral lost by acid attacks is too great for repair by remineralization. This situation leads to the start of dental caries. Thus, dental caries involves an interaction among pathologic factors and protective factors.

Pathologic factors include acidogenic (acid-producing) bacteria, low saliva flow because of salivary gland dysfunction or the use of medication, and frequent fermentable carbohydrates in the diet (sucrose, glucose, fructose, and cooked starch). Protective factors include calcium, phosphate, proteins, and fluoride in the saliva; normal salivary flow; and antibacterial agents if needed (see Chapter 16). The release of acid over an extended period of time demineralizes the tooth structure adjacent to the plaque biofilm and eventually results in cavitation. Tooth cavitation, best referred to as a “carious lesion,” is more commonly called a “cavity,” and the affected tooth is said to be “carious” or “decayed.”

Types of Dental Caries

The classification of dental caries is intended to describe the rate, direction, and/or type of disease progression. The classification terms include rampant caries; chronic caries; arrested caries, and recurrent caries. These terms permit the oral healthcare practitioner to communicate the urgency with which restorative therapy should be delivered. As these terms are not specific regarding tooth and surface, they must be combined with other cavity classification terminology to permit location-specific communication.

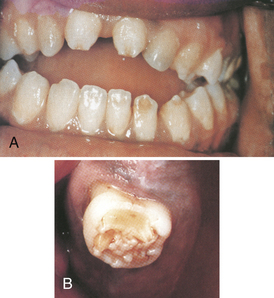

Rampant Caries

Rampant caries describes a rapidly progressive decay process that requires urgent intervention. The lesions are usually numerous and may be large. The decayed dentin is very soft and moist and is often light in color (Figure 14-27). Rampant caries is often associated with conditions such as early childhood caries in infants or with reduced saliva flow in clients, for example as a result of head and neck cancer radiation therapy.

Early Childhood Caries

Early childhood caries (ECC) is defined as the occurrence of any dental caries in the first 3 years of a child's life. The most common condition associated with ECC results from infants’ and young children's prolonged use of the baby bottle filled with sweetened juices or milk. This ECC condition was previously referred to as nursing caries, nursing bottle syndrome, or baby bottle caries. This type of ECC appears rapidly, commonly affecting maxillary anterior teeth, particularly the facial surfaces that are not generally considered to be at high risk for decay (Figure 14-28). Lesions may first appear as a cervical band of demineralization, rapidly progressing to overt caries. Mandibular teeth are often not affected, probably because the child's tongue covers these teeth during the caries challenge.5

The evidence clearly shows that high levels of Streptococcus mutans organisms transmitted from the mother are associated with ECC. These elevated bacteria levels combined with frequent carbohydrate intake produce high acid levels over long exposure periods. To provide early intervention strategies the dental hygienist identifies the risk factors for ECC as early as possible (Box 14-1). Several questions to ask parents or caregivers are listed in Box 14-2.

BOX 14-1 Risk Factors for the Development of Early Childhood Caries

Adapted from Milgrom P, Weinstein P: Early childhood caries: a team approach to prevention and treatment, Seattle, 1999, Continuing Education, University of Washington School of Dentistry.

BOX 14-2 Early Childhood Caries: Questions for Parents

Adapted from Milgrom P, Weinstein P: Early childhood caries: a team approach to prevention and treatment, Seattle, 1999, Continuing Education, University of Washington School of Dentistry.

Chronic Caries

Chronic caries describes a slowly progressive decay process that requires routine intervention. The carious dentin is firm and often brown to black. In large, open cavities the decayed dentin can be scooped out in large segments and has the consistency of firm leather (Figure 14-29).

Arrested Caries

Dental decay is not a continuous demineralization process. Evidence supports a continuous demineralization-remineralization process that can be tipped out of balance by changes in diet and oral environment (see Chapter 16). Because saliva provides the constituents that enable enamel to remineralize after an acid attack, a reduction in salivary flow or salivary buffering capacity may cause rapid demineralization. Conversely, demineralized lesions may recalcify as a result of an improved oral environment, especially in the presence of frequent use of 0.05% sodium fluoride mouth rinses. This recalcified lesion resulting from the remineralization process is known as arrested caries. Arrested lesions are characterized by their light or brown color and firm and glasslike surface when explored.

Types of Carious Lesions by Location

Carious lesions are often referred to by their specific location on a tooth. This descriptive mechanism may be best suited for describing the dental problem to the client. The location description may include anatomic representations such as pit and fissure caries, smooth surface caries, and root caries. Another method of describing the carious lesion location is to identify the specific tooth surface(s) with a lesion. It is not uncommon for noncarious tooth surfaces to become involved in the restoration process because of the need for access or cavity design. For example, a tooth with a carious lesion on the distal surface may require the involvement of the occlusal surface or a disto-occlusal cavity preparation for restoration. Therefore another form of classification is by the number or identification of involved surfaces rather than carious surfaces.

Pit and Fissure Caries

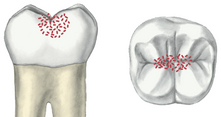

Pit and fissure caries is most frequently found in the grooves and crevices of the occlusal surfaces of premolars and molars (Figure 14-30). It is also found in maxillary incisor lingual pits, mandibular molar facial pits, and maxillary molar lingual grooves. Pits and fissures are particularly susceptible to a carious attack because of the protected bacterial niche provided by the inadequately coalesced developmental lobes of enamel.

Approximal Caries

Dental caries between teeth at the point of their proximal contact (the contact between teeth that serves to stabilize their position in the dental arch and to prevent food impaction between the teeth) is called proximal or approximal caries.

Smooth Surface Caries

Smooth surface caries is found on the facial, lingual, mesial, and distal surfaces of the dentition. The proximal smooth surfaces are the most susceptible to dental caries because of the shelter they provide for plaque biofilm development. The gingival third of the facial and lingual surfaces also is more susceptible to caries because of the increased difficulty associated with cleaning this less-bulbous portion of the crown.

Root Caries

Root caries is found on tooth root surfaces. Root caries is most frequently found in the elderly population, in whom root exposure is common because of gingival recession (Figure 14-31).

Pulpal Damage

The most common causes of pulpal nerve damage are bacterial infection and trauma. Bacterial infection is most often caused by extensive decay. If bacteria reach the nerves and blood vessels, the infection results in an abscess (Figure 14-32). Endodontics is the specialty of dentistry that manages the prevention, diagnosis, and treatment of the dental pulp and the periradicular tissues that surround the root of the tooth. Endodontic treatment, or root canal therapy, provides an effective means of saving a tooth that might otherwise have to be extracted.

Figure 14-32 Diagram showing extensive decay into the pulp and formation of periapical abscess.

(From Bird DL, Robinson DS: Torres and Ehrlich modern dental assisting, ed 9, St Louis, 2009, Saunders.)

Although clients may experience symptoms differently, the most common signs and symptoms of pulpal nerve damage are as follows:

CLASSIFICATION OF DENTAL CARIES AND RESTORATIONS

Dental caries and dental restorations are commonly classified either by Black's classification or by the complexity classification system (see Chapter 36).

Black's Classification System

The most commonly used system to describe the types and locations of both dental caries and restorations was established by G.V. Black in the early 1900s. This descriptive system consists of six classifications, shown in Table 14-1.

TABLE 14-1 Black's Classification of Dental Caries and Restorations

| Classification | Description |

|---|---|

Class I  |

Caries or restoration in the pits and fissures on the occlusal surfaces of molars and premolars, facial (buccal) or lingual pits and molars, and lingual pits of maxillary incisors |

Class II  |

Caries or restoration on the proximal (mesial or distal) surfaces of the premolars and molars involving two or more surfaces |

Class III  |

Caries or restoration on the proximal (mesial or distal) surfaces of incisors and canines |

Class IV  |

Caries or restoration on the proximal (mesial or distal) surfaces of incisors and canines and also involving the incisal angle |

Class V

|

Caries or restoration on the gingival third of the facial or lingual surfaces of any tooth |

Class VI  |

Caries or restoration on the incisal edge of anterior teeth or the cusp tips of posterior teeth |

Figures from Robinson DS, Bird DL: Essentials of dental assisting, ed 4, St Louis, 2007, Saunders.

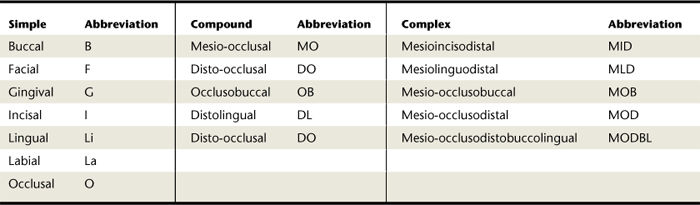

The Complexity Classification

The complexity classification identifies dental caries and restorations by the number of surfaces they involve. Simple caries or restorations are those involving only one tooth surface. Those that involve two surfaces are classified as compound caries or restorations, and complex caries or restorations involve more than two surfaces. The usual practice is to refer to the caries or restoration using the abbreviation of the surfaces affected, such as O for occlusal, DO for disto-occlusal, and MOD for mesio-occlusodistal. When doing so, the letters are pronounced separately, such as a D-O caries or an M-O-D restoration.

Table 14-2 outlines examples of simple, compound, and complex designations for dental caries or restorations named with nomenclature as described in the following section.

Nomenclature

In describing a cavity or a restoration, specific nomenclature is used that involves the combination of anatomic terms. Basic rules for nomenclature used to describe a cavity or restoration are as follows:

Rule 1: The terms mesial and distal precede all other terms, with mesial taking precedence (e.g., mesial occlusal distal).

Rule 1: The terms mesial and distal precede all other terms, with mesial taking precedence (e.g., mesial occlusal distal). Rule 2: The terms labial, buccal, facial, and lingual follow mesial and distal in that order and precede incisal and occlusal (e.g., mesial buccal occlusal).

Rule 2: The terms labial, buccal, facial, and lingual follow mesial and distal in that order and precede incisal and occlusal (e.g., mesial buccal occlusal). Rule 3: The terms incisal (for anterior teeth) and occlusal (for posterior teeth) occur last in any combination, except when they connect two surfaces not connected (e.g., mesial occlusal distal).

Rule 3: The terms incisal (for anterior teeth) and occlusal (for posterior teeth) occur last in any combination, except when they connect two surfaces not connected (e.g., mesial occlusal distal). Rule 4: In two-term combinations, the final letters “al” are dropped from the first term and replaced by “o” (e.g., mesiolingual).

Rule 4: In two-term combinations, the final letters “al” are dropped from the first term and replaced by “o” (e.g., mesiolingual). Rule 5: In three-term combinations, the final letters “al” are dropped from each of the first two terms and replaced by “o” (e.g., mesiolabioincisal).

Rule 5: In three-term combinations, the final letters “al” are dropped from each of the first two terms and replaced by “o” (e.g., mesiolabioincisal). Rule 6: Whenever dropping of an “al” results in a double “o,” a hyphen is added, separating them (e.g., disto-occlusodistal).

Rule 6: Whenever dropping of an “al” results in a double “o,” a hyphen is added, separating them (e.g., disto-occlusodistal).TOOTH ASSESSMENT AND DETECTION OF SIGNS OF DENTAL CARIES

Primary approaches to tooth assessment and dental caries detection are direct visual and tactile clinical examination, radiographic evaluation, and evaluation of symptoms described by the client.

Clinical Assessment

Direct clinical examination can be done well only if the teeth are clean and dry and illuminated with good light. Cotton roll isolation can be helpful in maintaining a dry environment, and air-drying of the teeth is essential for the individual examination of each tooth. When plaque biofilm and saliva coat the teeth, defects and signs of disease may go undetected. Tooth assessment proceeds systematically, beginning, for instance, with the most distal tooth in the maxillary right quadrant. The examination continues across the arch, through the last tooth in the maxillary left quadrant. Then the mandible is examined in reverse order, beginning with the most distal tooth in the mandibular left quadrant and ending with the last tooth in the mandibular right quadrant. See Box 14-3 for a description of a systematic approach for dentition charting.

BOX 14-3 Sequential Approach for Dentition Charting

Adapted from Darby ML: Mosby's comprehensive review of dental hygiene, ed 6, St Louis, 2006, Mosby.

For caries detection, traditionally the clinician examined the tooth surfaces with an explorer to probe questionable tooth surfaces such as pits and fissures, white or brown spot areas, and restoration margins. If the explorer stuck or tugged back on withdrawal, then the area was determined to be positive for caries. The accuracy of this approach is now being questioned because the explorer may do the following:

Stick or tug back owing to wedging in narrow and deep pits and fissures rather than because of caries

Stick or tug back owing to wedging in narrow and deep pits and fissures rather than because of caries Fail to reach the base of the pit or fissure owing to narrow, deep pit and fissure morphology, causing the clinician to miss an active carious lesion

Fail to reach the base of the pit or fissure owing to narrow, deep pit and fissure morphology, causing the clinician to miss an active carious lesion Not improve pit and fissure caries detection compared with visual inspection alone based on evidence-based research findings7,8

Not improve pit and fissure caries detection compared with visual inspection alone based on evidence-based research findings7,8Therefore, current thinking is that an explorer should not be used when suspected carious lesions are observed visually or on known sensitive areas.

Moreover, in terms of caries detection, tooth color is not a foolproof sign of dental caries, because carious dentin can range in color from nearly white to shades of black. If a dark area on a tooth is hard, regardless of the color, it is rarely an active carious lesion. The caries process often undermines otherwise intact enamel, producing a “pearly” appearance. In this case, color may be an indicator of the extent of the carious lesion. Marginal ridges, especially in anterior teeth, should be examined under a well-directed light. The careful use of a nonmagnifying, front-surface mirror for transillumination may show signs of undermining decay, which can then be substantiated by the dentist.

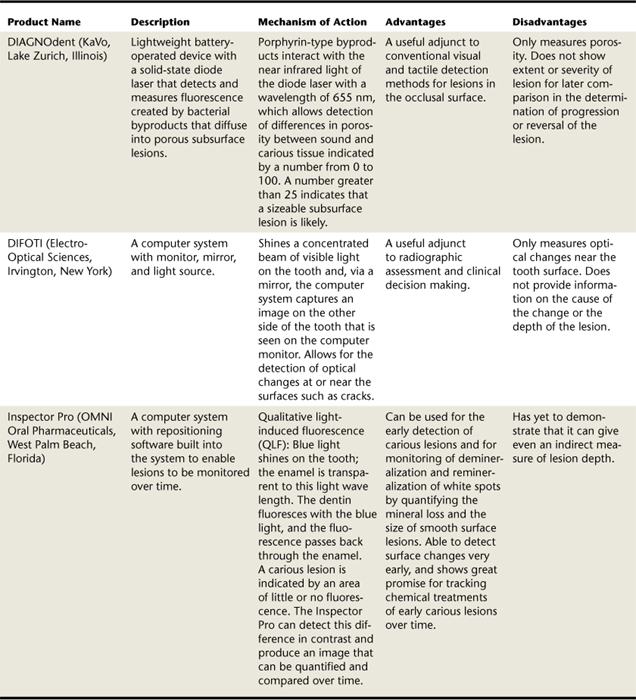

Currently several other methods for caries detection are being evaluated. Table 14-3 presents new technologies currently available to clinicians. These or other technologies may soon replace the use of an explorer altogether.

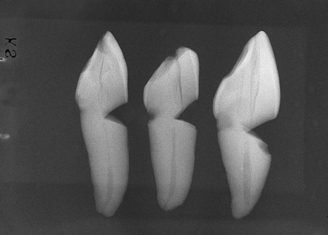

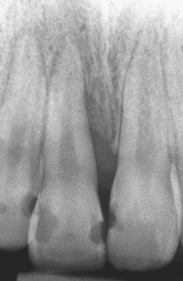

Radiographic Assessment

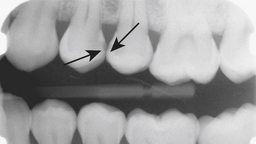

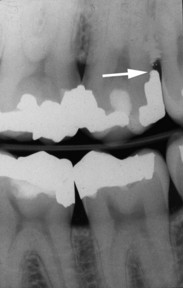

Bitewing radiographs (radiographs that include images of the crown and about half of the roots of several posterior teeth in both arches) are standard diagnostic tools for posterior teeth. Bitewing radiographs produce the best image of the tooth crowns, the main area of concern for dental caries and tooth restoration. Dental caries just under the contact between teeth is detected best with bitewing radiographs. Carious lesions appear as radiolucent (black) images on radiographs because dental caries causes localized demineralization and loss of tooth tissue (Figure 14-33). Depending on their density, restorative materials produce relatively radiopaque (white) images. Because of the contrast between the oral tissues and the restorative materials, radiographs readily illustrate the fit and contours of restorations. For example, all suspected overhanging margins of fillings can be verified by radiographs (Figure 14-34).

Figure 14-33 Premolar bitewing radiograph. Arrows point to sign of proximal dental caries between No. 12 and No. 13.

(From Daniel SJ, Harfst SA, Wilder RS: Mosby's dental hygiene, ed 2, St Louis, 2008, Mosby.)

Figure 14-34 Portion of a bitewing radiograph showing restorations and amalgam overhang on the distal surface of maxillary second molar.

(From Newman MG, Takei HH, Klokkevold PR, Carranza FA: Carranza's clinical periodontology, ed 10, St Louis, 2006, Saunders.)

Periapical radiographs (radiographs that include the tips of roots of teeth in a single arch) may be used for anterior and posterior teeth if they are determined to be necessary during the clinical examination (Figure 14-35). In addition, periapical radiographs are required of any tooth in which the health of the pulp and the tip of the root are in question (see Chapter 30, Figure 30-11).

Client Symptom Assessment

Client report of pain elicited by sugar intake, sensitivity to changes in temperature, and objectionable taste are frequently a result of advanced carious lesions or leaking or defective restorations. Tooth abrasions and erosions may be sensitive to toothbrushing, acidic foods, and cold stimuli. Fractures of teeth may elicit sharp pain during chewing and contact with cold foods. When pain is reported, questioning the client is an important way to gain information about location, duration, postural changes, and qualities of the pain.9 Questioning should begin with a open-ended question such as “Tell me about your pain,” followed by more specific questions that focus on provoking factors, attenuating factors, frequency, and intensity (Box 14-4). These questions can be followed by further exploration in which the client is asked to expand on previous responses.

Client symptoms are essential to the dental diagnosis and are communicated to the dentist immediately. Factors indicating the need for immediate referral to a dentist for an endodontic diagnosis are listed in Box 14-5.

BOX 14-5 Factors Related to Dental Diagnosis of a Periapical (Endodontic) Abscess

Although thermal testing using hot or cold appliances is used to detect vital pulp tissue, electric pulp testers are considered more reliable. Electric pulp testing is based on electric stimulation to create pain to which one can react (Procedure 14-1). Electric pulp testing may not always be accurate because pulp vitality depends on blood supply, not nerves (Box 14-6).

Procedure 14-1 USE OF AN ELECTRIC PULP TESTER TO DETERMINE PULP VITALITY

STEPS

BOX 14-6 Factors That Affect Client Response to Pulp Testing

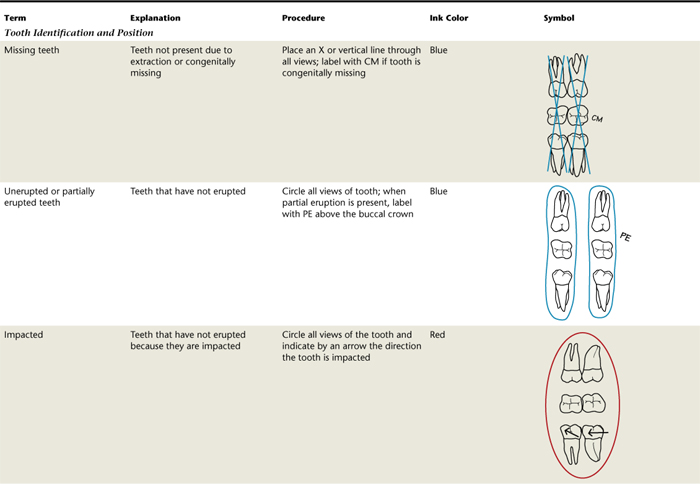

CHARTING TOOTH ASSESSMENT DATA

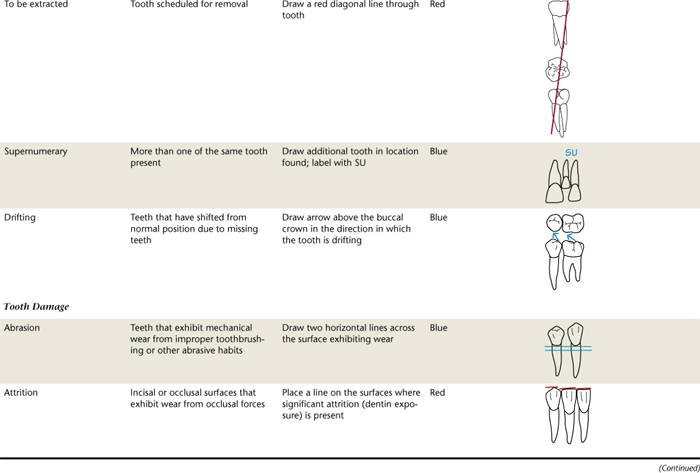

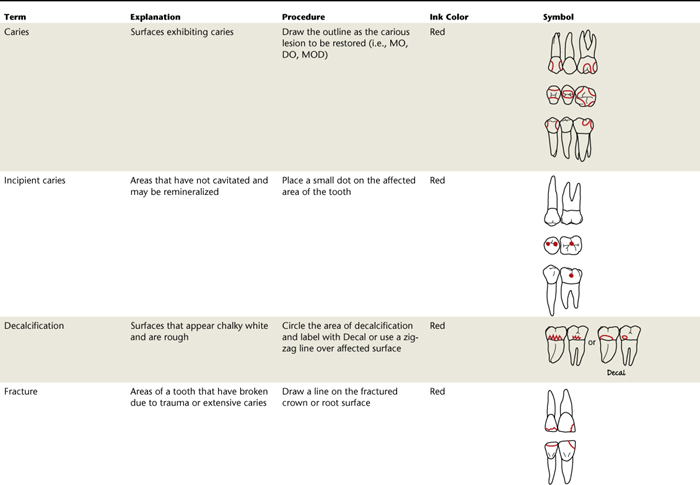

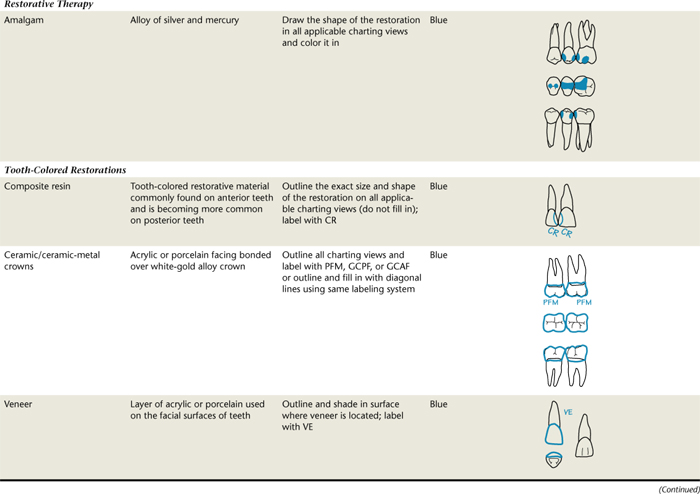

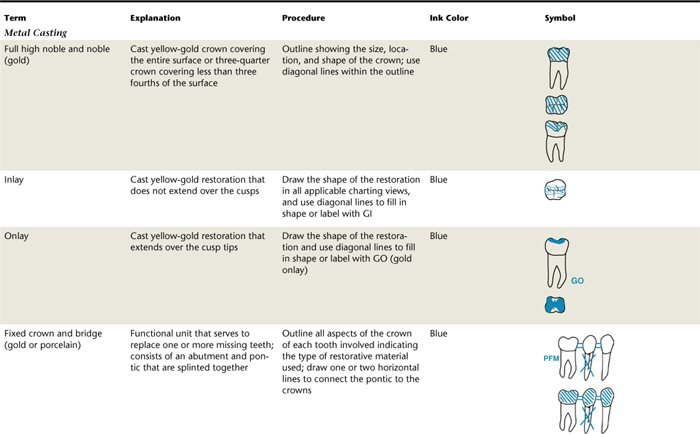

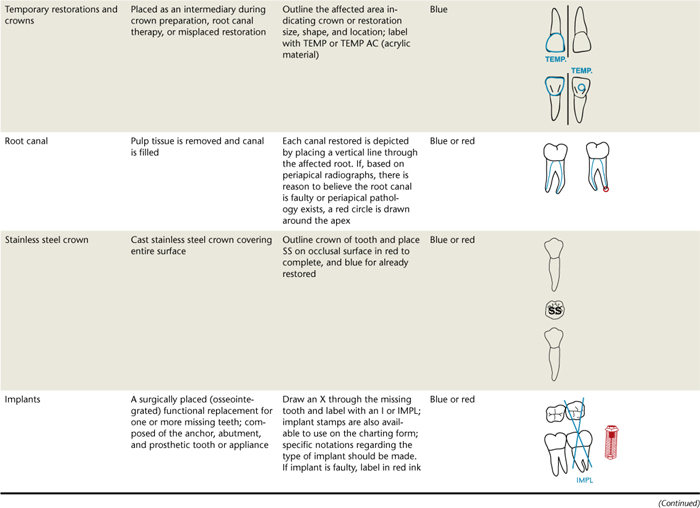

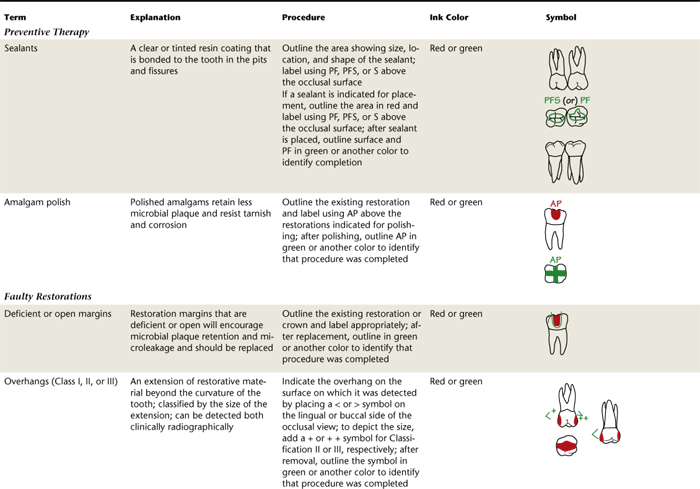

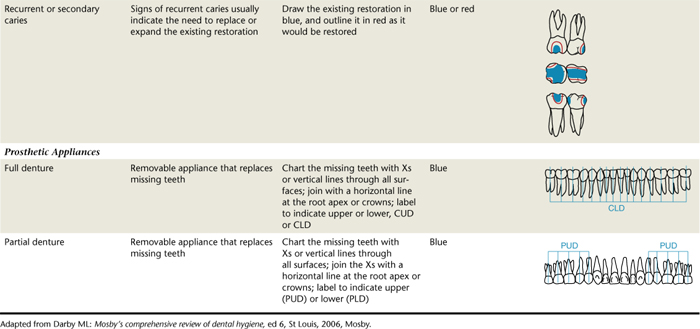

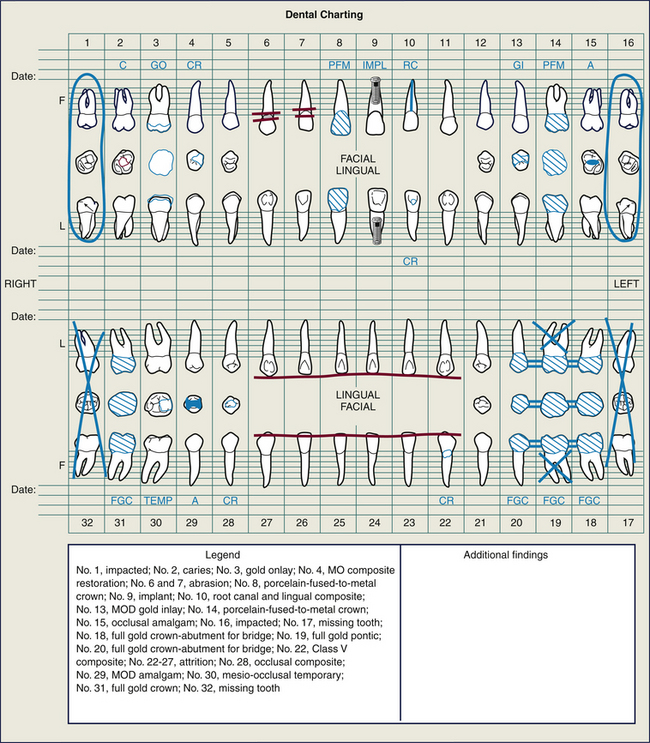

Charting tooth assessment data is conducted at the client's initial assessment appointment and updated at each reappointment. Although no set sequences are required for charting, a systematic approach avoids omitting important information (see Box 14-3). Table 14-4 outlines charting symbols, and Figure 14-38 illustrates an example of a completed chart along with a descriptive key of the charted symbols.

(From Bird DL, Robinson DS: Torres and Ehrlich modern dental assisting, ed 9, St Louis, 2009, Saunders.)

OCCLUSION

Thorough assessment of the dentition includes classifying occlusion and documenting any teeth malrelationships present. Occlusion is defined as the contact relationship between maxillary and mandibular teeth when the jaws are in a fully closed position, as well as the relationship between the teeth in the same arch. As the primary teeth erupt in the child, occlusion develops and is influenced by the development of facial muscles and neuromuscular patterns. Among the factors influencing occlusion, the eruption of the permanent teeth is affected by the shedding of the primary teeth.

Centric Occlusion

An ideal occlusion, with 138 occlusal contacts when the 32 permanent teeth are in closure, rarely, if ever, exists. Consequently, centric occlusion serves as the standard point of reference for describing a normal occlusion. Centric occlusion is the relation of opposing occlusal surfaces that provides the maximum planned contact and/or intercuspation when the teeth are closed. It should exist when the mandible is in centric relation to the maxilla. When the teeth of a normal occlusion are in centric position, each tooth of one arch is in occlusion with two teeth in the opposite arch, except for the mandibular central incisors and the maxillary third molars. This positioning of the teeth serves to equalize the forces of occlusion. Because of this arrangement, the alignment of the opposing jaw is not immediately disturbed if a tooth is lost. However, if restorative treatment is not performed for a long period, the neighboring teeth begin to drift mesially in an effort to fill the space. The teeth become tilted, and supereruption of the tooth opposite the space in the opposing arch occurs. Thus, the loss of one tooth can change the occlusion of the entire dentition.

When teeth do not occlude (come together) properly, unnatural stress is placed on them and the periodontium, so that they may be unable to perform their functions. This occlusal disharmony may lead to pain and/or occlusal trauma. Although occlusal trauma does not directly cause periodontal disease, it may be an adverse factor in an already diseased periodontium. An important role of the dental hygienist is to explain to clients the importance of tooth replacement to prevent occlusal disharmonies. To prevent occlusal disharmonies, all clients should have an occlusal evaluation by the dentist before and after completion of their dental treatment.10

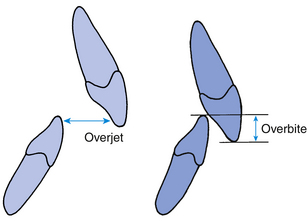

Overjet

When teeth normally come together in centric occlusion, there is a horizontal projection of the upper teeth beyond the lower teeth, usually measured parallel to the occlusal plane. This is termed overjet (Figure 14-39). This normal horizontal overlap is important because it keeps the soft tissue out of the way of the mandible during mastication.

Figure 14-39 Measuring overjet, the horizontal overlap between the two arches, and overbite, the vertical overlap between the two arches

(Adapted from Proffit WR, Fields HW, Sarver DM: Contemporary orthodontics, ed 4, St Louis, 2007, Mosby.)

Overjet is measured when the client's teeth are closed in centric occlusion and the tip of the periodontal probe is placed at a right angle to the labial surface of the mandibular incisor at the base of the incisal edge of the maxillary incisor. The measurement is taken from the labial surface of the mandibular incisor to the lingual surface of the maxillary incisor. The labiolingual width of the maxillary incisor is not included in the recorded measurement. The dental hygienist measures and records the overlap in millimeters.

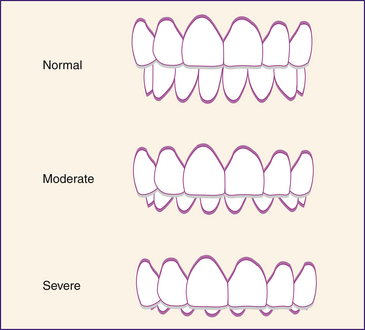

Overbite

In centric occlusion the maxillary incisors vertically overlap the mandibular incisors, a position called overbite. This vertical overlap allows maximum contact between the posterior teeth during mastication. Overbite is classified as normal, moderate, or severe based on the depth of the overlap. Overbite is considered normal if the maxillary incisors overlap within the incisal third of the mandibular incisors. Moderate overbite occurs when the maxillary incisors overlap to the middle third of the mandibular incisors, and severe overlap when the incisal edges of the maxillary teeth reach the gingival third of the mandibular incisors (Figure 14-40).

Overbite is measured when the client's maxillary and mandibular teeth are closed in centric occlusion. The tip of the periodontal probe is placed at the incisal edge of the maxillary incisor at right angles to the mandibular incisor. As the client slightly opens his or her mouth, the probe then is placed vertically against the mandibular incisor to measure the distance to the incisal edge of the mandibular incisor. It is customary to measure the overbite in millimeters or percentage and to include a classification of normal, moderate, or severe with the recorded measurement. These variations should be documented in writing on the client's chart.10

Centric Relation

Centric relation is the relation of the mandible to the maxilla when the condyles are in their most posterosuperior unstrained positions in the fossae. This position allows for lateral movements to be made at the occluding vertical relation normal for the individual. Ideally the mandible is in centric relation when the dentition is in centric occlusion. Usually the teeth slide about 1 mm when clients shift their occlusion from centric relation to centric occlusion.10

Contact Areas

In the ideal dental arch there are contact areas where the teeth touch their same arch neighbor on their proximal surfaces. These contact areas protect the interdental gingiva and stabilize each tooth in the dental arch. When there is no contact area between teeth, these open contacts can trap food, resulting in gingival inflammation. The use of floss is an effective tool, along with radiographs, in assessing the status of an open contact. The client may also report food impaction issues. Open contacts need to be called to the attention of the dentist for evaluation and treatment.10

Normal Occlusion

In the late 1800s Dr. Edward H. Angle established a system of classification of occlusion. Angle's method of classification was based on the principle that the maxillary first molars are the keys to occlusion. Because of their stability within the dental arch, the permanent first molars and later the canines were added as the indicator teeth to assess the relationship between the maxilla and the mandible. In a normal molar relationship the mesiobuccal cusp of the maxillary permanent first molar occludes with the buccal groove of the mandibular permanent first molar. In a normal canine relationship the maxillary permanent canine occludes with the distal half of the mandibular permanent canine and the mesial half of the mandibular first premolar.

MALOCCLUSION

Malocclusion is a deviation of the maxillary and mandibular relations of teeth and a lack of overall ideal form in the dentition while in centric occlusion. In addition, excessive overjet or overbite is classified as malocclusion.

Malocclusion may have a negative effect on the client's personal appearance and may make it more difficult for the client to perform effective oral hygiene. Plaque biofilm initiates periodontal disease; therefore individuals with malocclusion are at increased risk for this disease, and malocclusion may also contribute to temporomandibular joint pain. As part of the dental hygiene assessment, occlusion is classified on both the right and left sides of the dentition. Malocclusion and temporomandibular joint dysfunctions, such as pain or popping on opening and closing the mandible, are referred to the dentist for further evaluation (see Chapter 59 for detailed discussion of malocclusion and orthodontic treatment).

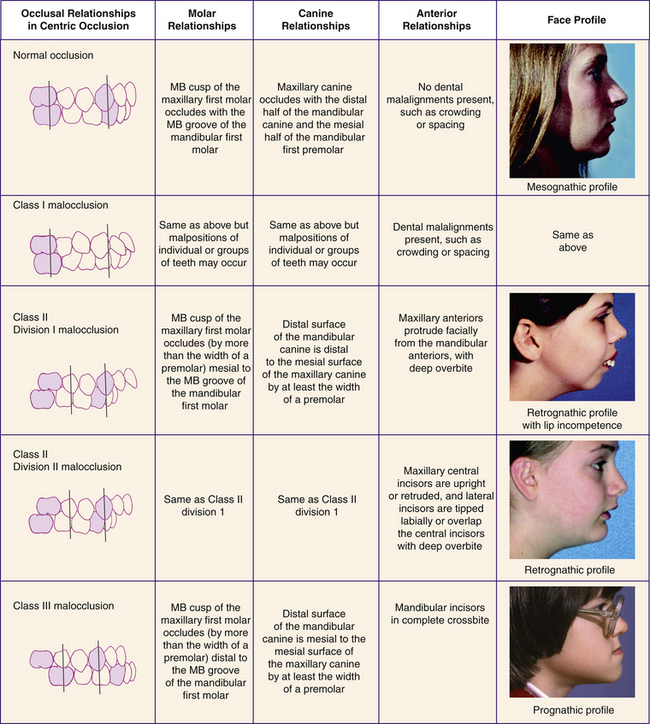

In Angle's system there are three types of malocclusion in the permanent dentition: Class I, Class II, and Class III. Class II malocclusion is subclassified into divisions 1 and 2 (Figure 14-41).

Figure 14-41 Classification of malocclusion. MB, Mesiobuccal.

(Adapted from Bath-Balogh MB, Fehrenbach MJ: Illustrated dental embryology, histology, and anatomy, ed 2, St Louis, 2006, Saunders. Photographs from Proffit WR, Fields Jr HW, Sarver DM: Contemporary orthodontics, ed 4, St Louis, 2007, Mosby.)

Class I Malocclusion

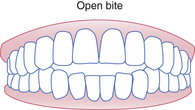

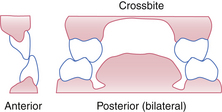

In Class I malocclusion the molar and canine relationships are similar to those in normal occlusion. However, in Class I malocclusion there are malrelationships between individual teeth or groups of teeth. For example, there may be problems with crowding where the teeth are out of line within the dental arch. Some clients with Class I malocclusion have slight, moderate, or severe overbites, or an open bite in which the anterior teeth do not occlude. Some clients have an end-to-end bite in which the teeth occlude without the maxillary teeth overlapping the mandibular teeth, or a crossbite in which the maxillary teeth are positioned lingually to mandibular teeth, an abnormal buccolingual tooth position (Table 14-5). The facial profile associated with Class I malocclusion is classified as straight or orthognathic (see Figure 14-41).

TABLE 14-5 Malrelationships of Individual Teeth or Groups of Teeth

First three figures from Bath-Balogh M, Fehrenbach MJ: Illustrated dental embryology, histology, and anatomy, ed 2, St Louis, 2006, Saunders.

| Malrelationship | Description |

|---|---|

| Open bite | Abnormal vertical spaces between mandibular and maxillary teeth most frequently observed in the anterior teeth; however, may occur in posterior areas |

| End-to-end (sometimes referred to as edge-to-edge in the anterior sextant) | The teeth occlude without the maxillary teeth overlapping the mandibular teeth. An end-to-end bite can occur anteriorly and posteriorly, unilaterally or bilaterally |

| Crossbite | Maxillary teeth are positioned lingually to the mandibular teeth; may occur unilaterally or bilaterally |

| Labioversion | A tooth positioned labial or facial to its normal position |

| Linguoversion | A tooth positioned lingual to its normal position |

Class II Malocclusion

Class II and III malocclusions are referred to as skeletal malocclusions because of the differences in size or the abnormal relationship between the maxilla and the mandible. Class II malocclusion, also referred to as distal occlusion, is characterized by the buccal groove of the mandibular first permanent molar being distal to the mesiobuccal cusp of the maxillary first permanent molar by at least the width of a premolar. The canine relationship is such that the distal surface of the mandibular permanent canine is distal to the mesial surface of the maxillary permanent canine by at least the width of a premolar. If the distance is less than the width of a premolar, it is classified as having a “tendency toward Class II.” An individual with a Class II malocclusion usually has a retrognathic facial profile, that is, a small, receded chin because of the apparently small mandible in relationship to the maxilla.

Two subdivisions of the Class II malocclusion are used to indicate the relationship of the anterior teeth. In Class II division 1, the maxillary incisors protrude facially from the mandibular incisors. As a result the mandibular incisors overerupt, causing a severe overbite. Often the palate is deep and narrow and the facial profile includes a protruding upper lip. In Class II division 2, one or more of the maxillary central incisors are lingually inclined or retruded (see Figure 14-41). The maxillary lateral incisors may overlap the central incisors. Overbite is severe, but the palate is wide in comparison with division 1.10

Class III Malocclusion

In Class III malocclusion the mandible is relatively large compared with the maxilla; thus a prognathic profile results (see Figure 14-41). The molar relationship is such that the buccal groove of the mandibular first permanent molar is situated mesial to the mesiobuccal cusp of the maxillary first permanent molar by at least the width of a premolar, whereas the distal surface of the mandibular permanent canine is mesial to the mesial surface of the maxillary permanent canine by at least the width of a premolar. Similar to the case with the Class II malocclusion, if the distance of movement in the molars or canine is less than the width of a premolar, the classification of occlusion is labeled as “tendency toward Class III.”10

PRIMARY OCCLUSION (SEE CHAPTER 59, TABLE 59-1)

Parafunctional Habits

Parafunctional habits are movements of the mandible, such as clenching, bruxism, thumbsucking, and rocking of teeth, that are considered outside or beyond the functions of eating, speech, or respiration. These parafunctional habits often occur subconsciously during sleep or while concentrating deeply on something.

Clenching occurs when the teeth occlude for a long time while in centric position without giving the mandible a rest. Persons who clench their teeth may have enlarged masseter muscles and may consider it normal to feel tension in the facial and masticatory muscles. Directed relaxing of these muscles may help in some cases. Clenching may be due to stress or the way individuals process neurologic impulses.10

Bruxism is the forceful grinding of the teeth together, often making an audible noise. Attrition and wear facets, of the incisal or occlusal surfaces of the teeth, especially of the canine cusp tips, results from bruxism. Persons who clench or grind their teeth should be referred to a dentist for a “day/guard/or night guard,” which can be worn during waking hours and/or when sleeping. A day/guard/or night guard is an oral appliance that covers the dentition. It protects the teeth from further attrition and helps to spread the occlusal force generated by the habit throughout the dentition. Newer designs may just involve several anterior teeth.

Sucking the thumb or fingers usually occurs in children and can cause extreme overjet of the maxillary incisors, irreversibly stretched lips, a deep palate, and a callused thumb or finger.

CLIENT EDUCATION TIPS

Inform about areas of acquired tooth damage, and provide caries preventive strategies based on caries risk (see Chapter 16).

Inform about areas of acquired tooth damage, and provide caries preventive strategies based on caries risk (see Chapter 16). Inform about the many factors—local (e.g., trauma), systemic (e.g., diseases, nutritional deficiencies, excess systemic fluoride), hereditary, and idiopathic (unknown)—that may cause enamel formation anomalies.

Inform about the many factors—local (e.g., trauma), systemic (e.g., diseases, nutritional deficiencies, excess systemic fluoride), hereditary, and idiopathic (unknown)—that may cause enamel formation anomalies.LEGAL, ETHICAL, AND SAFETY ISSUES

The American Dental Hygienists’ Association code of ethics states that clients must be kept informed of their treatment progress and health status.

The American Dental Hygienists’ Association code of ethics states that clients must be kept informed of their treatment progress and health status.KEY CONCEPTS

Documentation of tooth assessments is important for care planning, communication, legal documentation, and quality assurance.

Documentation of tooth assessments is important for care planning, communication, legal documentation, and quality assurance. Dental charting is the graphic representation of the condition of the client's teeth observed on a specific date. The data recorded are based on clinical and radiographic assessment and the client's report of symptoms.

Dental charting is the graphic representation of the condition of the client's teeth observed on a specific date. The data recorded are based on clinical and radiographic assessment and the client's report of symptoms. The Universal Numbering System sequentially numbers permanent teeth 1 through 32; primary teeth are alphabetically labeled A through T.

The Universal Numbering System sequentially numbers permanent teeth 1 through 32; primary teeth are alphabetically labeled A through T. Using quadrant and tooth designations, the International Numbering System provides a two-digit system to identify teeth.

Using quadrant and tooth designations, the International Numbering System provides a two-digit system to identify teeth. An ideal chart for tooth assessment contains sufficient space for initial recording of data and for successive findings.

An ideal chart for tooth assessment contains sufficient space for initial recording of data and for successive findings. The dental chart is a part of the permanent client record and needs to be accessible for reference during all appointments, thus facilitating continuity, sequencing, and ongoing documentation of care.

The dental chart is a part of the permanent client record and needs to be accessible for reference during all appointments, thus facilitating continuity, sequencing, and ongoing documentation of care. Tooth assessment evaluates the presence of developmental anomalies and signs of acquired tooth damage and defective restorations.

Tooth assessment evaluates the presence of developmental anomalies and signs of acquired tooth damage and defective restorations. Dental caries and dental restorations are commonly classified either by Black's classification or by the complexity classification system.

Dental caries and dental restorations are commonly classified either by Black's classification or by the complexity classification system. Direct examination can be done well only if the teeth are clean and dry and illuminated with good light. Care should be exercised to avoid exploring early carious lesions and known sensitive areas.

Direct examination can be done well only if the teeth are clean and dry and illuminated with good light. Care should be exercised to avoid exploring early carious lesions and known sensitive areas. The goal of tooth assessment for the dental hygienist is to recognize signs of developmental anomalies and acquired tooth damage and call them to the attention of the dentist, thus optimizing client care.

The goal of tooth assessment for the dental hygienist is to recognize signs of developmental anomalies and acquired tooth damage and call them to the attention of the dentist, thus optimizing client care. Teeth with signs of disease and client reports of dental pain should be communicated to the dentist immediately.

Teeth with signs of disease and client reports of dental pain should be communicated to the dentist immediately. The dental hygienist may use percussion, a cold stick, or an electric pulp tester to test for pulp vitality. These tests, along with a well-organized and thorough clinical assessment of signs, symptoms, and radiographs, provide additional information to assist the dentist in making an endodontic diagnosis.

The dental hygienist may use percussion, a cold stick, or an electric pulp tester to test for pulp vitality. These tests, along with a well-organized and thorough clinical assessment of signs, symptoms, and radiographs, provide additional information to assist the dentist in making an endodontic diagnosis. Thorough dentition assessment includes classifying occlusion and documenting any tooth malrelationships present.

Thorough dentition assessment includes classifying occlusion and documenting any tooth malrelationships present. Contact areas protect the interdental gingiva and stabilize each tooth in the dental arch. Open contacts need to be called to the dentist's attention for evaluation and treatment.

Contact areas protect the interdental gingiva and stabilize each tooth in the dental arch. Open contacts need to be called to the dentist's attention for evaluation and treatment. Malocclusion results when there is lack of overall ideal form in the dentition while in centric occlusion.

Malocclusion results when there is lack of overall ideal form in the dentition while in centric occlusion.Refer to the Procedures Manual where rationales are provided for the steps outlined in the procedure presented in this chapter

CRITICAL THINKING EXERCISES

Marie Smith, a 49-year-old woman, reports that her last dental examination was 18 months ago. Her health history reveals that she currently is being treated for depression and is taking an antidepressant medication. Her chief concerns are the recent sensitivity of several teeth and an uncomfortable dry mouth that she experiences most of the time. Gingivitis and moderate generalized plaque biofilm are present, with heavy accumulations in posterior lingual areas. On assessment of Marie's teeth, the dental hygienist observes the following:

1. Sturdevant C.M., Roberson T.M., Heymann H.O., Sturdevant J.O., editors. The art and science of operative dentistry, ed 3, St Louis: Mosby, 1994.

2. Ibsen O.A.C., Phelan J.A. Oral pathology for the dental hygienist, ed 5. St Louis: Saunders; 2009.

3. Robinson H.B.G., Miller A.S. Color atlas of oral pathology. Philadelphia: Lippincott; 1990.

4. Milosevic A. Toothwear: aetiology and presentation. Dental Update. 1998;25:6.

5. Milgrom P., Weinstein P. Early childhood caries: a team approach to prevention and treatment. Seattle: Continuing Education, University of Washington School of Dentistry; 1999.

6. Loesche W.J., Svanberg M.L., Pape H.L. Intraoral transmission of Streptococcus mutans by a dental explorer. J Dent Res. 1979;58:765.

7. Featherstone J.D.B. The science and practice of caries prevention. J Am Dent Assoc. 2000;131:887.

8. Featherstone J.D.B., O’Reilly M.M., Shariati M., Brugler S. Enhancement of remineralization in vitro and in vivo. In: Leach S.A., editor. Factors relating to demineralization and remineralization of the teeth. Oxford, England: IRL Press, 1986.

9. Cohen S. Diagnostic procedures. In Cohen S., Burns R.C., editors: Pathways of the pulp, ed 7, St Louis: Mosby, 1998.

10. Bath-Balogh M., Fehrenbach M. Illustrated dental embryology, histology, and anatomy, ed 2. St Louis: Saunders; 2006.

Visit the  website at http://evolve.elsevier.com/Darby/Hygiene for competency forms, suggested readings, glossary, and related websites..

website at http://evolve.elsevier.com/Darby/Hygiene for competency forms, suggested readings, glossary, and related websites..