Cancers of the Musculoskeletal System

In addition to increasing age as a red flag and risk factor for cancer, we now add “young age” as a possible red flag factor. Primary bone cancer is more likely to occur in the population under age 25. Both primary bone cancer and cancer that has metastasized to the bone present with the same subset of clinical signs and symptoms because in both cases, the same system (skeletal) is affected.

Sarcoma

Malignant neoplasms or new growths that develop as primary lesions in the musculoskeletal tissues are relatively rare, representing less than 1% of malignant disease in all age groups and 15% of annual pediatric malignancies.131

Secondary neoplasms that develop in the connective tissues as metastases from a primary neoplasm elsewhere (especially metastatic carcinoma) are common. Fibrosarcomas occurring after radiotherapy can occur usually after a significant latent period (4 years or longer).132

High grade (higher grade represents greater likelihood of metastasis based on measures of cell differentiation and growth) and evidence of metastasis are associated with a poor prognosis for all neoplasms of bone or soft tissue. The prognosis for clients with soft tissue sarcoma depends on several factors. Factors associated with a poorer prognosis include age older than 60 years, tumors larger than 5 cm, and histology of high grade.133

Soft Tissue Tumors

Soft tissue sarcomas make up a group of relatively rare malignancies. Little is known about important epidemiologic or etiologic factors in clients with soft tissue sarcomas. There is no proven genetic predisposition to the development of soft tissue sarcomas, but studies do indicate that workers exposed to phenoxyacetic acid in herbicides and chlorophenols in wood preservatives and persons who had radiation to the tonsils, adenoids, and thymus may have an increased risk of developing soft tissue sarcoma. There are two peaks of incidence in human sarcoma development: early adolescence and the middle decades.

Soft tissue sarcomas can arise anywhere in the body. In adults, most soft tissue sarcomas arise in the extremities (usually the lower extremity, at or below the knee), followed by the trunk and the retroperitoneum. In their early stages, these sarcomas do not usually cause symptoms because soft tissue is relatively elastic, allowing tumors to grow rather large before they are felt or seen.

In contrast, the overwhelming majority of childhood soft tissue sarcomas are rhabdomyosarcomas, and the anatomic distribution of these lesions is entirely different (18% in the extremities, 35% in the head and neck region, and 20% in GU sites).134 Many of the primary sites in children (e.g., orbit of the eye, paratesticular region, prostate) are never primary sites for soft tissue sarcoma in adults.

Risk Factors: Soft tissue sarcomas occur more frequently in persons who have one of the following conditions:

Metastases: In children, tumors of the extremities tend to behave relatively aggressively, with a high incidence of nodal spread and distant metastases. In adults, soft tissue sarcomas rarely spread to regional lymph nodes, instead invading aggressively into surrounding tissues with early hematogenous dissemination, usually to the lungs and to the liver.

Even with pulmonary metastases, the survival rate has greatly improved over the past decade with a multidisciplinary approach that includes multiagent chemotherapy and limb-sparing surgery.134 However, as more people survive for increasingly longer periods, serious and potentially life-threatening complications of such therapy can develop months to years later.

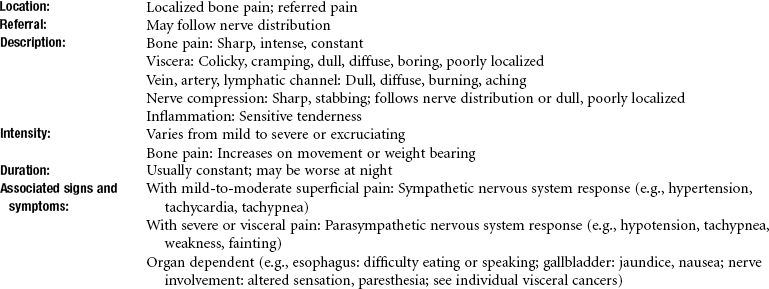

Clinical Signs and Symptoms: Soft tissue sarcomas most often appear as asymptomatic soft tissue masses. Because these lesions arise in compressible tissues and are often far from vital organs, symptoms are few unless they are located close to a major nerve or in a confined anatomic space.

The most common manifestations of these neoplasms are swelling and pain. Pelvic sarcomas may appear with swelling of the leg or pain in the distribution of the femoral or sciatic nerve. Some people attribute swelling to a minor injury, reporting a misleading cause of onset to the therapist. The therapist must always keep this in mind when evaluating a client of any age.

More often, the neoplasm goes unnoticed until some trauma or injury requires medical attention and an x-ray study reveals the lesion. When pain is the most significant symptom, it is usually mild and intermittent, progressively becoming more severe and more constant with rapidly growing neoplasms.

No reliable physical signs are present to distinguish between benign and malignant soft tissue lesions. Consequently, all soft tissue lumps that persist or grow should be reported immediately to the physician.

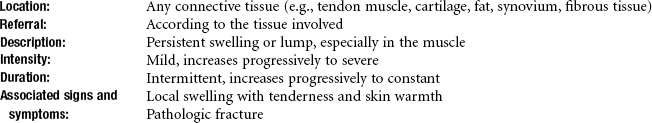

Bone Tumors

Malignant (primary) bone tumors are relatively rare, accounting for 1% of total deaths from cancer. Excluding multiple myeloma, the ratio of benign to malignant bone tumors is approximately 7 : 1.

Primary bone cancer affects children and young adults most commonly, whereas secondary bone tumors or metastatic neoplasms occur in adults with primary cancer (e.g., cancer of the prostate, breast, lungs, kidneys, thyroid).

Symptoms are not necessarily different between primary and secondary bone cancer, but the history is very different. Medical screening with possible referral is essential for anyone with clinical manifestations discussed in this chapter (see Clinical Manifestations of Malignancy: Skeletal) who also has a past medical history of any kind of cancer.

This text is limited to the most common forms of bone tumors. The two most common childhood sarcomas of the bone are osteosarcoma (osteogenic sarcoma) and Ewing family of tumors (EFT).

Osteosarcoma: Osteosarcoma (also known as osteogenic sarcoma) is the most common type of bone cancer, occurring between the ages of 10 and 25 years and also in adulthood. It is slightly more common in boys.

Although it can involve any bones in the body, because it arises from osteoblasts, the usual site is the epiphyses of the long bones, where active growth takes place (e.g., lower end of the femur, upper end of the tibia or fibula, upper end of the humerus).

In general, 80% to 90% of osteosarcomas occur in the long bones; the axial skeleton is rarely affected. The growth spurt of adolescence is a peak time for the development of osteosarcoma. Half of all osteosarcomas are located in the upper leg above the knee, where the most active epiphyseal growth occurs.

Risk Factors: There appears to be an association between rapid bone growth and risk of tumor formation. Young people previously treated with radiation for an earlier cancer have an increased risk of developing osteosarcoma later.

With chemotherapy given before and after surgical removal, many people can now be cured of osteosarcoma. Survival lessens if metastases are present. Limb-sparing surgery rather than amputation is effective in 50% to 80% of people.135

Metastases: Bone tumors, unlike carcinomas, disseminate almost exclusively through the blood; bones lack a lymphatic system. Metastases to the lungs, pleura, lymph nodes, kidneys, and brain and to other bones are common and occur early in the disease process.

Hematogenous spread occurs to the lungs first and to other bones second. In some cases, surgery can be attempted to remove pulmonary metastases, but survival decreases if metastatic sites are present.

Clinical Signs and Symptoms: Osteosarcoma usually appears with pain in a lesional area, usually around the knee in clients with femur or tibia involvement. The pain is initially mild and intermittent but becomes progressive and more severe and more constant over time.

Most lesions produce pain as the tumor starts to expand the bony cortex and stretch the periosteum. A tender lump may develop, and a bone weakened by erosion of the metaphyseal cortex may break with little or no stress. This pathologic fracture often brings the person into the medical system, at which time a diagnosis is established by x-ray study and surgical biopsy. This neoplasm is highly vascularized, so that the overlying skin is usually warm.

Ewing Sarcoma: Four percent of all childhood tumors are in the Ewing family of tumors (EFT). In the United States, approximately 300 to 400 children and adolescents are diagnosed with a Ewing tumor each year. Although rare, it is the third most frequent primary sarcoma of bone after osteosarcoma and chondrosarcoma. Almost any bone can be involved, but typically, the pelvis, femur, tibia, ulna, and metatarsus are the most common sites for Ewing sarcoma. Soft tissue involvement is rare.136

Risk Factors: Ewing sarcoma is most common between the ages of 5 and 16 years, with a slightly greater incidence in boys than in girls. Anyone of any age can develop Ewing sarcoma but most people who have Ewing tumors are in the second decade of life and Caucasian, either Hispanic or non-Hispanic. This tumor is rare in other racial groups.137 A spontaneous (rather than environmentally or trauma-induced) gene translocation in chromosome 22 has been found with EFT, and there is study in this area. No other risk factors have been identified in the development of EFTs.

Metastases: Metastases are predominantly hematogenous (to lungs and bone), although lymph node involvement may occur. Metastases usually occur late in the disease process, but aggressive chemotherapy has increased 5-year survival rates from 10% to 70%.

Clinical Signs and Symptoms: Ewing sarcoma is a rapidly growing tumor that often outgrows its blood supply and quickly erodes the bone cortex, producing a painful, soft, tender, palpable mass. Intramedullary tumors that erode into the periosteum often result in an “onion skin” appearance as the periosteum is elevated and replaced by a new periosteal bone.

The most common symptom of EFT, bone pain, appears in about 85% of people with bone tumors. The pain may be caused by periosteal erosion from a break or fracture of a bone weakened by the tumor.

The pain may be intermittent and may not be accompanied by swelling, resulting in a physical therapy referral. Systemic symptoms, such as fatigue, weight loss, and intermittent fever, may be present, especially in clients with metastatic disease. Fever may occur when products of bone degeneration enter the bloodstream. In addition, the blood supply to local areas of bone may be compromised, with resultant avascular necrosis of bone.

Ewing sarcoma occurs most frequently in the long bones and the pelvis, the most common site being the distal metaphysis and the diaphysis of the femur. The next most common sites are the pelvis, tibia, fibula, and humerus (Case Example 13-9). About 30% of the time, the bone tumor may be soft and warm to the touch and the child may have a fever.

Less common presentations of Ewing sarcoma include primary rib tumor associated with a pleural effusion and respiratory symptoms, mandibular lesions presenting with chin and lip paresthesias, primary vertebral (cervical, lumbar) tumor with symptoms of nerve root or spinal cord compression, primary sacral tumor with neurogenic bladder, and pelvic tumor with pain and bowel/bladder disturbances. Neurologic symptoms may occur secondary to nerve entrapment by the tumor, and misdiagnosis as lumbar disk disease can occur.138 If the tumor has spread, the child may feel very tired or may lose weight.

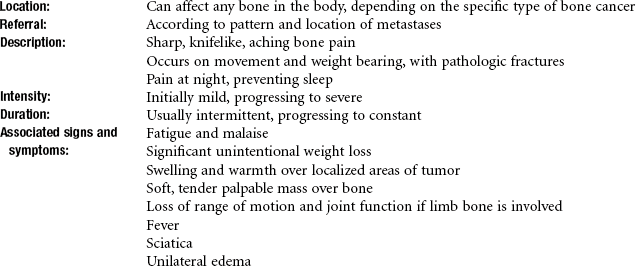

Chondrosarcoma: Chondrosarcoma, the most common malignant cartilage tumor (and second most common sarcoma of bone after osteosarcoma), occurs most often in adults older than 40. However, when it does occur in a younger age group, it tends to be a higher grade of malignancy and capable of metastases.

It occurs most commonly in some part of the pelvic or shoulder girdles or long bones such as the femurs (Fig. 13-8). Chondrosarcomas are the most common malignant tumors of the sternum and scapula.

Fig. 13-8 Large intramedullary calcified lesion diagnosed as a low-grade chondrosarcoma of the femur. A, Anteroposterior radiograph. B, Lateral view. (From Dorfman HD, Czerniak B: Bone tumors, St. Louis, 1998, Mosby.)

Chondrosarcoma is usually a relatively slow-growing malignant neoplasm that arises either spontaneously in previously normal bone or as a result of malignant change in a preexisting benign bone tumor (osteochondromas and enchondromas or chondromas). The latter are referred to as secondary chondrosarcomas, which are composed entirely of cartilaginous tissue and usually represent a low-grade malignancy.139

Metastases: Although slow growing, chondrosarcoma has a high tendency for thrombus formation in the tumor blood vessels, with an increased risk for pulmonary embolism and metastatic spread to the lungs. Metastases develop late, so the prognosis of chondrosarcoma is considerably better than that of osteosarcoma.

Clinical Signs and Symptoms: Clinical presentation of chondrosarcoma varies. Peripheral chondrosarcomas (arising from bone surface) grow slowly and may be undetected and quite large. Local symptoms develop only because of mechanical irritation; otherwise, pain is not a prominent symptom.

Pelvic chondrosarcomas are often large and appear with pain referred to the back or thigh, sciatica caused by sacral plexus irritation, urinary symptoms from bladder neck involvement, or unilateral edema caused by iliac vein obstruction.

Conversely, central chondrosarcomas (arising within bone) appear with dull pain, and a mass is rare. Pain, which indicates active growth, is an ominous sign of a central cartilage lesion.

Osteoid Osteoma: Osteoid osteoma is a noncancerous osteoblastic tumor that accounts for approximately 10% of benign bone tumors. It occurs predominantly in children and young adults between the ages of 7 and 25, affecting males 2 to 3 times more often than females.140

Osteoid osteoma is a noncancerous lesion with distinct histologic features, consisting of a central core of vascular osteoid tissue and a peripheral zone of sclerotic bone (Fig. 13-9). This type of tumor commonly occurs in the diaphysis of long bones such as the proximal femur, accounting for more than half of all cases; less often, the hands and feet and posterior elements of the spine are involved.

Fig. 13-9 Osteoid osteoma. A, A 15-year-old boy whose pain was worse at night and relieved by aspirin was found to have a well-defined lytic intracortical lesion in the proximal femoral shaft. Note the thickening around and extending above and below the nidus. B, Computed tomography (CT) of the same osteoid osteoma shows marked sclerosis of the bone around the nidus. (From Dorfman HD, Czerniak B: Bone tumors, St. Louis, 1998, Mosby.)

On x-ray, the lesion is seen as a translucent area representing the nidus, usually measuring less than 1 cm, that is surrounded by bone sclerosis. The nidus may be uniformly radiolucent or may contain variable amounts of calcification. Computed tomography (CT) shows a well-circumscribed small area of low attenuation, representing the nidus, surrounded by a larger area of higher attenuation, representing the reactive bone formation.

Clinical Signs and Symptoms: The clinical presentation typically consists of pain, which is often worse at night, increased skin temperature, sweating, and tenderness in the affected region. In many cases, pain is completely relieved by aspirin (a salicylate compound), which is a hallmark finding for this particular type of bone cancer.141

The pathogenesis of this pain may be related to production of prostaglandins by the tumor cells. Prostaglandins can cause changes in vascular pressure, which result in local stimulation of sensory nerve endings. Salicylates in the aspirin inhibit the prostaglandins, reducing painful symptoms.140

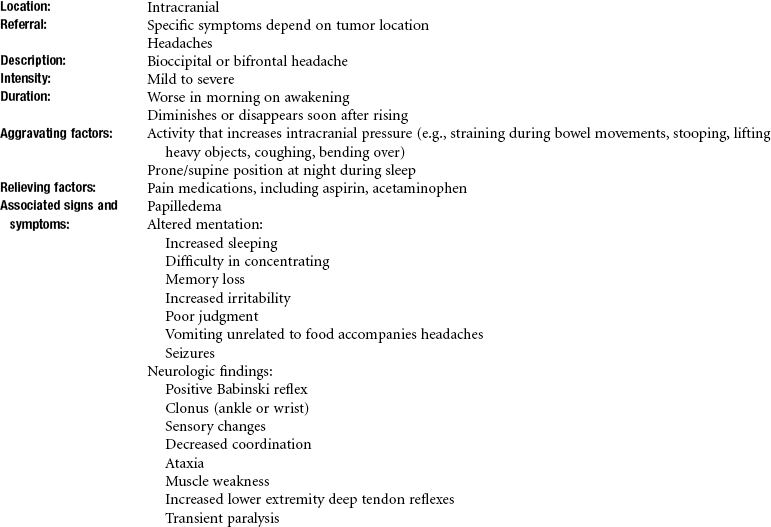

Primary Central Nervous System Tumors

Primary tumors of the CNS once thought to be rare are now recognized as a significant problem in the United States. The incidence among persons over age 70 has increased sevenfold since 1970, with the incidence in people of all ages rising by 9% in the past 3 decades.142 The majority of people who develop primary brain tumors are over the age of 40, but these tumors can cause morbidity and mortality in younger individuals as well.

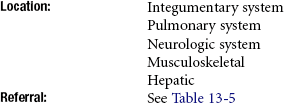

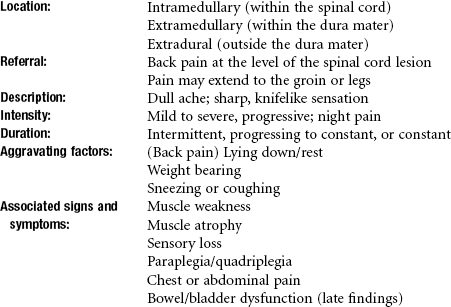

CNS neoplasms include tumors that lie within the spinal cord (intramedullary), within the dura mater (extramedullary), or outside the dura mater (extradurally). About 80% of CNS tumors occur intracranially, and 20% affect the spinal cord and peripheral nerves. Of the intracranial lesions, about 60% are primary, and the remaining 40% are metastatic lesions, often multiple and most commonly from the lung, breast, kidney, and GI tract.

More common benign tumors are meningiomas (from meninges) and schwannomas (from nerve sheaths), both arising from tissues of origin. These tumors are considered noncancerous histologically, but sometimes malignant by location, meaning that they can be located in an area where tumor removal is difficult and deficit and death can result.

Any CNS tumor, even if well differentiated and histologically benign, is potentially dangerous because of the lethal effects of increased intracranial pressure and tumor location near critical structures. For example, a small, well-differentiated lesion in the pons or medulla may be more rapidly fatal than a massive liver cancer.

Primary CNS tumors rarely metastasize outside the CNS; there is no lymphatic drainage available, and hematogenous spread is also unlikely. In most cases, CNS spread is contained within the cerebrospinal axis, involving local invasion or CNS seeding through the subarachnoid space and the ventricles.

Whether from primary CNS tumors or cancer that has metastasized to the CNS from some other source, the effects are the same. Clinical manifestations of CNS involvement were discussed earlier in this chapter.

Risk Factors

The incidence of primary CNS lymphoma is increasing among older adults who are immunocompetent and even more so among aging adults who are immunodeficient. The etiology of most primary brain tumors is unknown, although ionizing radiation has been implicated most often.

Children with a history of cranial radiation therapy, such as low-dose radiation of the scalp for fungal infection, are at significantly greater risk of developing primary brain tumors. However, most radiation-induced brain tumors are caused by radiation to the head used for the treatment of other types of cancer.143

Occupational exposure to gases and chemicals has been proposed as a risk factor. Several congenital genetic disorders are directly linked with an increased risk of primary brain tumors (e.g., neurofibromatosis, Turcot syndrome, tuberous sclerosis). Other potential environmental risk factors, such as exposure to vinyl chloride and petroleum products, have shown inconclusive results. Current preliminary evidence has shown altered brain activity with exposure to electromagnetic fields from cell phones or other wireless devices.144 Whether this effect on the brain is neutral, positive, or negative remains under investigation.

Brain Tumors

The incidence of primary brain tumor is increasing in persons of all ages; in children, it is second only to leukemia as a cause of death. Although the causes for this overall increase remain unknown, it is clear that it is not simply a matter of better diagnostic techniques. Adding the number of people who survive other primary cancers but later develop metastatic brain tumors increases the overall incidence dramatically.

Individuals with mental disorders are more likely to be diagnosed with brain tumors and at younger ages than people without mental illness. This increased risk for brain tumors may reflect the early presence of mental symptoms, or there may be a true association between the two conditions. The exact relationship remains unknown at this time.145

Primary Malignant Brain Tumors

The most common primary malignant brain tumors are astrocytomas. Low-grade astrocytomas (Grade I), such as juvenile pilocytic astrocytomas, have an excellent prognosis after surgical excision.

At the other extreme is the Grade IV glioma such as glioblastoma multiforme, which is an aggressive, high-grade tumor with a very poor prognosis (usually less than 12 months). There are intermediate histologic grades (II, III) with intermediate survival statistics. Low-grade tumors are more common in children than in adults.143

Metastatic Brain Tumors

Cancer can spread through bloodborne metastasis or via cerebrospinal fluid pathways. Therefore the brain is a common site of metastasis. In fact, metastatic brain tumors are probably the most common form of malignant brain tumors.

The cerebrum is the most common site of metastasis. Cerebellar metastases are less frequent; brainstem metastases are the least common. Approximately two-thirds of people with brain metastases will present with multiple metastases.

Up to 50% of individuals affected with cancers develop neurologic symptoms resulting from brain metastases. Headache, seizures, loss of motor function, and cerebellar signs are the most common early symptoms.

As mentioned previously, any neurologic sign can be the silent presentation of cancer metastasized to the CNS. The most common sources of brain metastases are cancers of the lung and breast, followed by metastases from melanomas and cancers of the colon and kidney.

Spinal Cord Tumors

Spinal tumors are similar in nature and origin to intracranial tumors but occur much less often. They are most common in young and middle-aged adults, and they occur most often in the thoracic spine because of its length, proximity to the mediastinum, and likelihood of direct metastatic extension from lymph nodes involved with lymphoma, breast cancer, or lung cancer.

Metastases

Most metastasis is disseminated by local invasion. Spinal cord tumors account for less than 15% of brain tumors. As mentioned, 10% of spinal tumors are themselves metastasized neoplasms from the brain.

One other means of dissemination is through the intervertebral foramina. The extradural space communicates through the intervertebral foramina with adjacent extraspinal compartments such as the mediastinum and retroperitoneal space.

In most cases, extradural tumors are metastatic, reaching the extradural space and then adjacent extraspinal spaces through this foraminal connection. Tumors within the spinal cord (intramedullary) or outside the spinal cord (extramedullary) may metastasize to the dural tube to become intradural tumors.

Clinical manifestations of spinal tumors vary according to their location. See previous discussion in this chapter on Clinical Manifestations of Malignancy: Neurologic. Pain associated with extramedullary tumors can be located primarily at the site of the lesion or may refer down the ipsilateral extremity, with radicular involvement from nerve root compression, irritation, or occlusion of blood vessels supplying the cord. Progressive cord compression is manifested by spastic weakness below the level of the lesion, decreased sensation, and increased weakness.

Intramedullary tumors produce more variable signs and symptoms. High cervical cord involvement causes spastic quadriplegia and sensory changes. Tumors in descending areas of the spinal cord produce motor and sensory changes appropriate to functions of that level.

Cancers of the Blood and Lymph System

Cancers arising from the bone marrow include acute leukemias, chronic leukemias, multiple myelomas, and some lymphomas. These cancers are characterized by the uncontrolled growth of blood cells.

The major lymphoid organs of the body are the lymph nodes and the spleen (see Figs. 12-1 and 4-41). Cancers arising from these organs are called malignant lymphomas and are categorized as either Hodgkin’s disease or non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma.

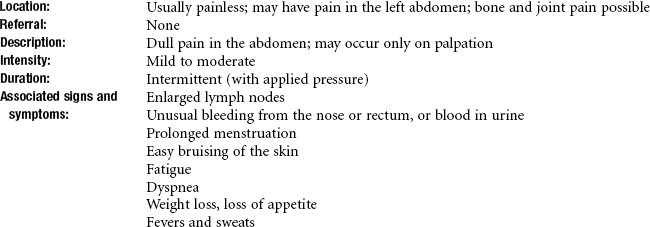

Leukemia

Leukemia, a malignant disease of the blood-forming organs, is the most common malignancy in children and young adults. One-half of all leukemias are classified as acute, with rapid onset and progression of disease resulting in 100% mortality within days to months without appropriate therapy.

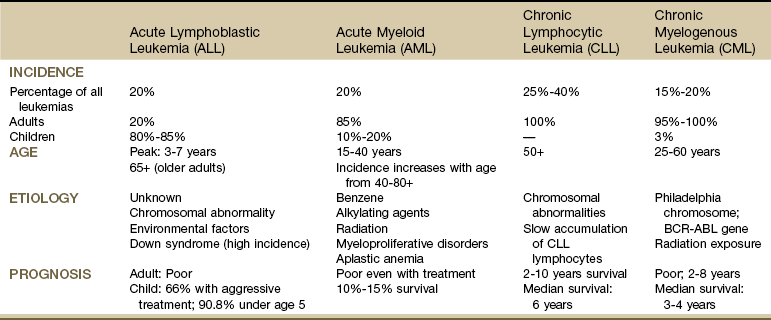

Acute leukemias are most common in children from 2 to 4 years of age, with a peak incidence again at age 65 years and older. The remaining leukemias are classified as chronic, which have a slower course and occur in persons between the ages of 25 and 60 years. From these two broad categories, leukemias are further classified according to specific malignant cell line (Table 13-9).

TABLE 13-9

There are many alternate names for these four main types of leukemia. For further details, see the Leukemia and Lymphoma Society (www.lls.org).

From Goodman CC, Fuller KS: Pathology: implications for the physical therapist, ed 3, Philadelphia, 2009, WB Saunders.

Leukemia develops in the bone marrow and is characterized by abnormal multiplication and release of white blood cell (WBC) precursors. The disease process originates during WBC development in the bone marrow or lymphoid tissue. In effect, leukemic cells become arrested in “infancy,” with most of the clinical manifestations of the disease being related to the absence of functional “adult” cells, which are products of normal differentiation.

With rapid proliferation of leukemic cells, the bone marrow becomes overcrowded with immature WBCs, which then spill over into the peripheral circulation. Crowding of the bone marrow by leukemic cells inhibits normal blood cell production.

Decreased red blood cell (RBC; erythrocyte) production results in anemia and reduced tissue oxygenation. Decreased platelet production results in thrombocytopenia and risk of hemorrhage. Decreased production of normal WBCs results in increased vulnerability to infection, especially because leukemic cells are functionally unable to defend the body against pathogens.

Leukemic cells may invade and infiltrate vital organs such as the liver, kidneys, lung, heart, or brain.

Risk Factors

Several predisposing factors for the development of leukemia have been identified. Exposure to ionizing radiation remains the most conclusively identified causative factor in humans. Prior drug therapies, such as chloramphenicol, phenylbutazone, chemotherapy alkylating agents, and benzene, have been implicated in the development of acute leukemia.

Hereditary syndromes associated with development of leukemia include Bloom syndrome, Down syndrome, Klinefelter’s syndrome, neurofibromatosis, and others. In addition, viruses and immunodeficiency disorders have been associated as causative factors.146

Clinical Signs and Symptoms

Most of the clinical findings in acute leukemia are due to bone marrow failure, which results from replacement of normal bone marrow elements by malignant cells. Infections are due to a depletion of competent WBCs needed to fight infection. Abnormal bleeding is caused by a lack of blood platelets required for clotting, and severe fatigue is due to a lack of red blood cells. The most common symptoms of leukemia include infection, fever, pallor, fatigue, anorexia, bleeding, anemia, neutropenia, and thrombocytopenia.

For women, the abnormal bleeding may be prolonged menstruation leading to anemia. The Special Questions for Women (see Appendix B-32) may elicit this kind of valuable information, which would then require medical referral. Less common manifestations include direct organ infiltration; clients may experience easy bruising of the skin or abnormal bleeding from the nose, urinary tract, or rectum.

The appearance of a painless, enlarged lymph node or skin lesion (see Fig. 4-29) is followed by weakness, fever, and weight loss. A history of chronic immunosuppression (e.g., antirejection drugs for organ transplants, chronic use of immunosuppressant drugs for inflammatory or autoimmune diseases, cancer treatment) in the presence of this clinical presentation is a major red flag.

Clients on immunosuppressants do not usually have an elevated body temperature, so the presence of a fever is a red flag in this group. Significant weight loss with inactivity secondary to pain is another red flag; most inactive individuals experience weight gain not weight loss. A good rule of thumb to use in recognizing significant weight loss is 10% of the individual’s total body weight in 10 to 14 days without trying.

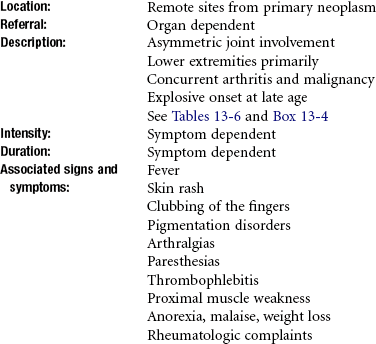

Lymphoproliferative malignancies, such as leukemia and lymphoma, may also involve extramedullary areas and can present with localized or generalized symptoms such as enlarged liver and spleen, bone and joint pain, bone fracture, and parotid gland and testicular infiltration.146

Involvement of the synovium may lead to symptoms suggestive of rheumatic disease. A possible presentation in a child with acute lymphoblastic leukemia can be joint pain and swelling that mimics juvenile idiopathic arthritis (JIA) (formerly JRA). Leukemic arthritis is present in about 5% of leukemia cases. Acute leukemia can cause joint pain that is severe and episodic and disproportionately severe in comparison to the minimal heat and swelling that are present.147

Arthritic symptoms in such a child may be a consequence of leukemic synovial infiltration, hemorrhage into the joint, synovial reaction to an adjacent tumor mass, or crystal-induced synovitis.

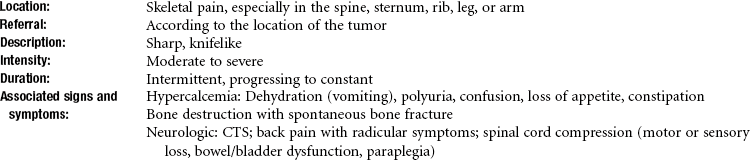

Multiple Myeloma

Multiple myeloma is a cancer caused by uncontrolled growth of plasma cells in the bone marrow. Excessive growth of plasma cells originating in the bone marrow destroys bone tissue and is associated with widespread osteolytic lesions (decreased areas of bone density). Plasma cells are part of the immune system, and in multiple myeloma, they grow uncontrolled, forming tumors in the bone marrow.

Bone lesions and hypercalcemia can occur in some hematologic malignancies such as multiple myeloma. Multiple myeloma to date is an incurable disease, but the prognosis has improved, with lengthy remissions possible with treatment.

Risk Factors

There are no clear predisposing factors, other than age or exposure to ionizing radiation. This disease can develop at any age from young adulthood to advanced age but peaks among persons between the ages of 50 and 70 years. It is more common in men and African Americans. Molecular genetic abnormalities have been identified in the etiologic complex of this disease. Recent data suggest that a virus (Kaposi-associated herpes virus, HHV-8) may be implicated in acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS)–related cases.148

Clinical Signs and Symptoms

Multiple myeloma causes symptoms in many areas of the body. It normally originates in the bone marrow and then causes difficulties in other organs. The onset of multiple myeloma is usually gradual and insidious. Most clients pass through a long presymptomatic period that lasts 5 to 20 years.

Early symptoms involve the skeletal system, particularly the pelvis, spine, and ribs. Some clients have backache or bone pain that worsens with movement (Case Example 13-10). Bone disease is the most common complication and results in severe bone pain, pathologic fractures, hypercalcemia, and spinal cord compression. Renal failure, anemia, cardiac failure, and infection are serious and often fatal complications of this process.149

Bone Destruction: Bone pain is the most common symptom of myeloma. It is caused by infiltration of the plasma cells into the marrow with subsequent destruction of bone. Initially, the skeletal pain may be mild and intermittent, or it may develop suddenly as severe pain in the back, rib, leg, or arm, often the result of an abrupt movement or effort that has caused a spontaneous (pathologic) bone fracture.

The pain is often radicular and sharply cutting to one or both sides and is aggravated by movement. As the disease progresses, more and more areas of bone destruction and hypercalcemia develop. Symptoms associated with bone pain usually subside within days to weeks after initiation of antiresorptive agents. If left untreated, this disease will result in skeletal deformities, particularly of the ribs, sternum, and spine.

Hypercalcemia: Bone fractures are a result of osteoclast activity and bone destruction. This process results in calcium release from the bone and hypercalcemia. Hypercalcemia is considered an oncologic emergency. To rid the body of excess calcium (hypercalcemia), the kidneys increase the output of urine, which can lead to serious dehydration if there is an inadequate intake of fluids. Vomiting may compound this dehydration. Clients who have symptoms of hypercalcemia (see Table 13-7) should seek immediate medical care because this condition can be life-threatening.

Renal Effects: Drainage of calcium and phosphorus from damaged bones eventually leads to the development of renal stones, particularly in immobilized clients. Renal insufficiency is the second most common cause of death, after infection, in clients with multiple myeloma.

In addition to bone destruction, multiple myeloma is characterized by disruption of RBC, leukocyte, and platelet production, which results from plasma cells crowding the bone marrow. Impaired production of these cell forms causes anemia, increased vulnerability to infection, and bleeding tendencies.

Neurologic Complications: Approximately 10% of persons with myeloma have amyloidosis, deposits of insoluble fragments of a monoclonal protein resembling starch. These deposits cause tissues to become waxy and immobile and may affect nerves, muscles, tendons, and ligaments, especially the carpal tunnel area of the wrist. CTS with pain, numbness, or tingling of the hands and fingers may develop. Excess immunoglobulins, caused by multiple myeloma, can cause a hyperviscosity syndrome characterized by changes in mental status, vision, fatigue, angina, and bleeding disorders.150

More serious neurologic complications may occur in 10% to 15% of clients with multiple myeloma. Spinal cord compression is usually observed early or in the late relapse phase of disease. Back pain is usually present as the initial symptom, with radicular pain that is aggravated by coughing or sneezing. Motor or sensory loss and bowel/bladder dysfunction are signs of more extensive compression. Paraplegia is a later, irreversible event.

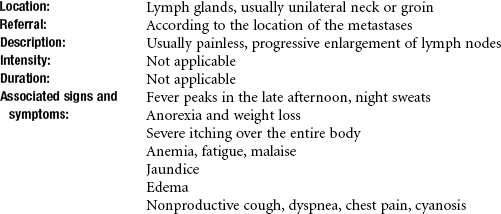

Hodgkin’s Disease

Hodgkin’s disease is a chronic, progressive, neoplastic disorder of lymphatic tissue characterized by the painless enlargement of lymph nodes with progression to extralymphatic sites such as the spleen and liver.

In Caucasians, Hodgkin’s disease demonstrates constant incidence rates, with a first peak occurring in adolescents and young adults and a second peak occurring in older adults. Men are affected more often than women, and boys are affected more often than girls.151

Epidemiologic and clinical-pathologic features of Hodgkin’s disease suggest that an infectious agent may be involved in this disorder. Recently, accumulated data provide direct evidence supporting a causal role of Epstein-Barr virus (EBV) in a significant portion of cases, and a greater incidence of Hodgkin’s disease has been observed in young individuals who previously had infectious mononucleosis.

Risk Factors

Infection with EBV and infectious mononucleosis has been associated with Hodgkin’s lymphoma. No other risk factors have been identified.

Metastases

The exact mechanism of growth and spread of Hodgkin’s disease remains unknown. The disease may progress by extension to adjacent structures or via the lymphatics because lymphoreticular cells inhabit all tissues of the body except the CNS. Hematologic spread may also occur, possibly by means of direct infiltration of blood vessels.

Clinical Signs and Symptoms

Hodgkin’s disease usually appears as a painless, enlarged lymph node, often in the neck, underarm, or groin. The therapist may palpate these nodes during a cervical spine, shoulder, or hip examination (see Figs. 4-41 through 4-43).

Lymph nodes are evaluated on the basis of size, consistency, mobility, and tenderness. Lymph nodes up to 1 cm in diameter of soft-to-firm consistency that move freely and easily without tenderness are considered within normal limits. Lymph nodes more than 1 cm in diameter that are firm and rubbery in consistency or tender are considered suspicious.

Enlarged lymph nodes associated with infection are more likely to be tender, soft, and movable than slow-growing nodes associated with cancer. Lymph nodes enlarged in response to infections throughout the body require referral to a physician, especially in someone with a current or previous history of cancer. The physician should be notified of these findings, and the client should be advised to have the lymph nodes checked at the next follow-up visit with the physician if not sooner, depending on the client’s particular circumstances.

As always, changes in size, shape, tenderness, and consistency raise a red flag. Supraclavicular nodes are common metastatic sites for occult lung and breast cancers, whereas inguinal nodes implicate tumors arising in the legs, perineum, prostate, or gonads.

Other early symptoms may include unexplained fevers, night sweats, weight loss, and pruritus (itching). The itching occurs more intensely at night and may result in severe scratches because the client is unaware of scratching during the sleep state. The fever typically peaks in the late afternoon, and night sweats occur when the fever breaks during sleep. Fatigue, malaise, and anorexia may accompany progressive anemia. Some clients with Hodgkin’s disease experience pain over the involved nodes after ingesting alcohol.

Symptoms may arise when enlarged lymph nodes obstruct or compress adjacent structures, causing edema of the face, neck, or right arm secondary to superior vena cava compression or causing renal failure secondary to urethral obstruction.

Obstruction of bile ducts as a result of liver damage causes bilirubin to accumulate in the blood and discolor the skin. Mediastinal lymph node enlargement with involvement of lung parenchyma and invasion of the pulmonary pleura progressing to the parietal pleura may result in pulmonary symptoms, including nonproductive cough, dyspnea, chest pain, and cyanosis.

Dissemination of disease from lymph nodes to bones may cause compression of the spinal cord, leading to paraplegia. Compression of nerve roots of the brachial, lumbar, or sacral plexus can cause nerve root pain.

Non-Hodgkin’s Lymphoma

Non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma (NHL) is a group of lymphomas affecting lymphoid tissue and occurring in persons of all ages. It is more common in adults in their middle and older years (40 to 60 years).

Risk Factors

Males are affected more often than females and individuals with congenital or acquired immunodeficiencies (e.g., those undergoing organ transplantation and anyone with autoimmune diseases are all at increased risk for development of NHL).151,152 In addition, some people who have been exposed to large levels of radiation (e.g., nuclear reactor accidents) or extensive radiation and chemotherapy for a different cancer site may be at increased risk for lymphoma.

Individuals infected with the human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) are at increased risk for developing NHL and to a lesser extent, Hodgkin’s disease as well. AIDS-related lymphoma (ARL) is now the second most common cancer associated with HIV after Kaposi’s sarcoma. The relative risk of developing lymphoma within 3 years of an AIDS diagnosis is increased by 165-fold when compared with people without AIDS.152

Several possible etiologic mechanisms are hypothesized for NHL. Immunosuppression, possibly in combination with viruses or exposure to certain infectious agents, could be the primary cause. Chemicals, UV light, blood transfusion, acquired and congenital immune deficiency, and autoimmune disorders increase the risk for NHL.153

Other studies link the disease to widespread environmental contaminants such as benzene found in cigarette smoke, gasoline, automobile emissions, and industrial pollution.

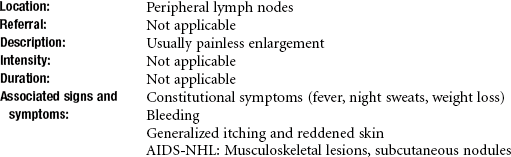

Clinical Signs and Symptoms

NHL presents a clinical picture broadly similar to that of Hodgkin’s disease, except that the disease is usually initially more widespread and less predictable. The disease starts in the lymph nodes, although early involvement of the oropharyngeal lymphoid tissue or the bone marrow is common, as is abdominal mass or GI involvement with complaints of vague back or abdominal discomfort.151

The most common manifestation is painless enlargement of one or more peripheral lymph nodes. Systemic symptoms are not as commonly associated with NHL as with Hodgkin’s disease. Clients with NHLs often have remarkably few symptoms, even though many node areas or extranodal sites are involved.

Most NHLs fall into two broad categories related to their clinical activity: indolent and aggressive lymphomas. Indolent disease may be minimally active and treatable for many years. However, the disease is frequently disseminated at the time of diagnosis. Surgery is usually used only for staging or debulking purposes. Combination chemotherapy, biotherapy (targeted monoclonal antibodies), and radiation therapies are now used as treatment for NHL. Radioactive isotope combinations with monoclonal antibodies are also in use for some types of NHL.151

Acquired Immunodeficiency Syndrome–Non-Hodgkin’s Lymphoma

Only recently has AIDS-NHL emerged as a major sequela of HIV infection. It now occurs frequently in clients who survive other consequences of AIDS.

The etiologic basis of AIDS-NHL is still under investigation; profound cellular immunodeficiency plays a central role in lymphoma genesis. The molecular pathogenesis is a complex process involving both host factors and genetic alterations.154

Nearly 95% of all HIV-associated malignancies are either NHL or Kaposi’s sarcoma. People with CNS lymphoma usually have advanced AIDS, are severely debilitated, and are usually thought to be at terminal stages of the disease.151

EBV often accompanies NHL. It is generally accepted that EBV acts in the pathogenesis of lymphoma owing to the alteration in balance between host and latent EBV infection in immunodeficiency states, with increased activity of the virus.

Risk Factors

Infection with HIV and related immunodeficiencies resulting from HIV are the primary risk factors for this disease. NHL is more likely to develop among clients who have Kaposi’s sarcoma, a history of herpes simplex infection, and a lower neutrophil count.

Clinical Signs and Symptoms

The most common presentations of HIV-related NHL are systemic B symptoms (which may suggest an infectious process), a rapidly enlarging mass lesion, or both. At the time of diagnosis, approximately 75% of clients will have advanced disease. Extranodal disease frequently involves any part of the body, with the most common locations being the CNS, bone marrow, GI tract, and liver.

Diagnosis of NHL in areas of the body other than the CNS is complicated by a history of fevers, night sweats, and weight loss and loss of appetite, which are also common symptoms related to HIV infection and AIDS.

Although musculoskeletal lesions are not reported as commonly as pulmonary or CNS abnormalities in HIV-positive individuals, a wide variety of osseous and soft tissue changes are seen in this group. Diffuse adenopathy, lower extremity pain and swelling, subcutaneous nodules, and lytic lesions of the extremities are common.155

Physician Referral

Early detection of cancer can save a person’s life. Any suspicious sign or symptom discussed in this chapter should be investigated immediately by a physician. This is true especially in the presence of a positive family history of cancer, a previous personal history of cancer, and environmental risk factors, and/or in the absence of medical or dental (oral) evaluation during the previous year.

The therapist is not responsible for diagnosing cancer. The primary goal in screening for cancer is to make sure the client’s problem is within the scope of a physical therapist’s practice. In this regard, documentation of key findings and communication with the physician are both very important.

When trying to sort out neurologic findings, remember to look for changes in DTRs, a myotomal weakness pattern, and changes in bowel/bladder function. These findings will not give you a definitive diagnosis but will provide you with valuable information to offer the physician if further medical testing is advised.

Pain on weight bearing that is unrelieved by rest or change in position and does not respond to treatment, unremitting pain at night, and a history of cancer are all red flags indicating that medical evaluation is needed.

Any recently discovered lumps or nodules must be examined by a physician. Any suspicious finding by report, on observation, or by palpation should be checked by a physician.

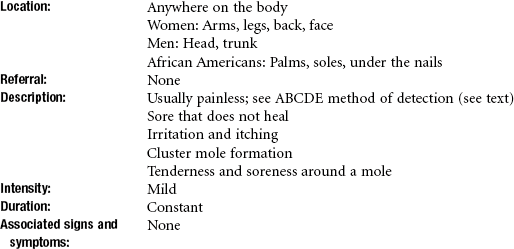

If any signs of skin lesions are described by the client or if they are observed by the therapist and the client has not been examined by a physician, a medical referral is recommended.

If the client is planning a follow-up visit with the physician within the next 2 to 4 weeks, that client is advised to indicate the mole or skin changes at that time. If no appointment is pending, the client is encouraged to make a specific visit either to the family/personal physician or to a dermatologist.

Guidelines for Immediate Physician Referral

• Presence of recently discovered lumps or nodules or changes in previously present lumps, nodules, or moles, especially in the presence of a previous history of cancer or when accompanied by carpal tunnel or other neurologic symptoms.

• Detection of palpable, fixed, irregular mass in the breast, axilla, or elsewhere requires medical referral or a recommendation to the client to contact a physician for evaluation of the mass. Suspicious lymph node enlargement or lymph node changes; generalized lymphadenopathy.

• Recurrent cancer can appear as a single lump, a pale or red nodule just below the skin surface, a swelling, a dimpling of the skin, or a red rash. Report any of these changes to a physician immediately.

• Notify physician of any suspicious changes in lymph nodes; note the presence of lymphadenopathy and describe the location and any observed or palpable characteristics.

• Presence of any of the early warning signs of cancer, including idiopathic muscle weakness accompanied by decreased DTRs.

• Any unexplained bleeding from any area (e.g., rectum, blood in urine or stool, unusual or unexpected vaginal bleeding, breast, penis, nose, ears, mouth, mole, skin, or scar).

• Any sign or symptom of metastasis in someone with a previous history of cancer (see individual cancer types for specific clinical signs and symptoms; see also Clues to Screening for Cancer).

• Any man with pelvic, groin, sacroiliac, or low back pain accompanied by sciatica and a past history of prostate cancer.

Clues to Screening for Cancer

• Previous personal history of any cancer, especially in the presence of bilateral carpal tunnel symptoms, back pain, shoulder pain, or joint pain of unknown or rheumatic cause at presentation

• Previous history of cancer treatment (late physical complications and psychosocial complications of disease and treatment can present in a somatic presentation)

• Any woman with chest, breast, axillary, or shoulder pain of unknown cause, especially with a previous history of cancer and/or over the age of 40

• Anyone with back, pelvic, groin, or hip pain accompanied by abdominal complaints, palpable mass

• For women: Prolonged or excessive menstrual bleeding (or in the case of the postmenopausal woman who is not taking hormone replacement, breakthrough bleeding)

• For men: Additional presence of sciatica and past history of prostate cancer

• Recent weight loss of 10% of total body weight (or more) within a 2-week to 1-month period of time without trying; weight gain is more typical with true musculoskeletal dysfunction because pain has limited physical activities

• Musculoskeletal symptoms are made better or worse by eating or drinking (GI involvement)

• Shoulder, back, hip, pelvic, or sacral pain accompanied by changes in bowel and/or bladder function or changes in stool or urine

• Hip or groin pain is reproduced by heel strike/hopping test or translational/rotational stress (bone fracture from metastases)

• When a back “injury” is not improving as expected or if symptoms are increasing

• Early warning signs, including proximal muscle weakness and changes in DTRs

• Constant pain (unrelieved by rest or change in position); remember to assess constancy by asking, “Do you have that pain right now?”

• Intense pain present at night (rated 7 or higher on a numeric scale from 0 for “no pain” to 10 for “worst pain”)

• Signs of nerve root compression must be screened for cancer as a possible cause

• Development of new neurologic deficits (e.g., weakness, sensory loss, reflex change, bowel or bladder dysfunction)

• Changes in size, shape, tenderness, and consistency of lymph nodes, especially painless, hard, rubbery lymph nodes present in more than one location

• A growing mass, whether painless or painful, is assumed to be a tumor unless diagnosed otherwise by a physician. A hematoma should decrease in size over time, not increase

• Disproportionate pain relieved with aspirin may be a sign of bone cancer (osteoid osteoma)

• Signs or symptoms seem out of proportion to the injury and persist longer than expected for physiologic healing of that type of injury; no position is comfortable (remember to conduct a screening examination for emotional overlay)

• Change in the status of a client currently being treated for cancer

1. Name three predisposing factors to cancer that the therapist must watch for during the interview process as red flags.

2. How do you monitor exercise levels in the oncology patient without laboratory values?

3. In a physical therapy practice, clients are most likely to present with signs and symptoms of metastases to:

a. Skeletal system, hepatic system, pulmonary system, central nervous system

b. Cardiovascular system, peripheral vascular system, enteric system

4. What is the significance of nerve root compression in relation to cancer?

5. Complete the following mnemonic:

6. Whenever a therapist observes, palpates, or receives a client report of a lump or nodule, what three questions must be asked?

7. How can the therapist determine whether a client’s symptoms are caused by the delayed effects of radiation as opposed to being signs of recurring cancer?

8. Give a general description and explanation of the changes seen in deep tendon reflexes associated with cancer.

9. Why is weight loss a significant red flag sign in a physical therapy practice?

10. When tumors produce signs and symptoms at a site distant from the tumor or its metastasized sites, these “remote effects” of malignancy are called:

11. A client who has recently completed chemotherapy requires immediate medical referral if he has which of the following symptoms?

12. A suspicious skin lesion requiring medical evaluation has:

13. What is the significance of Beau’s lines in a client treated with chemotherapy for leukemia?

a. Impaired nail formation from death of cells

b. Temporary longitudinal groove or ridge through the nail

c. Increased production of the nail by the matrix as a sign of healing

14. A 16-year-old boy was hurt in a soccer game. He presents with exquisite right ankle pain on weight bearing but reports no pain at night. Upon further questioning, you find he is taking Ibuprofen at night before bed, which may be masking his pain. What other screening examination procedures are warranted?

a. Perform a heel strike test.

b. Review response to treatment.

c. Assess for signs of fracture (edema, exquisite tenderness to palpation, warmth over the painful site).

15. When is it advised to take a work or military history?

a. Anyone with head and/or neck pain who uses a cell phone more than 8 hours/day

c. Anyone presenting with joint pain of unknown cause accompanied by multiple other signs and symptoms

d. This is outside the scope of a physical therapist’s practice

16. A 70-year-old man came to outpatient physical therapy with a complaint of pain and weakness of his fingers and morning stiffness lasting about an hour. He presented with bilateral swelling of the metacarpophalangeal (MCP) joints of the index and ring fingers. He saw his family doctor 4 weeks ago and was given diclofenac, which has not changed his symptoms. Now he wants to try physical therapy. Since he last saw his physician, he has developed additional joint pain in the left knee and right shoulder. How can you tell if this is cancer, polyarthritis, or a paraneoplastic disorder?

a. Ask about a previous history of cancer and recent onset of skin rash.

b. You can’t. This requires a medical evaluation.

c. Look for signs of digital clubbing, cellulitis, or proximal muscle weakness.

17. A 49-year-old man was treated by you for bilateral synovitis of the proximal interphalangeal (PIP) joints in the second, third, and fourth fingers. His symptoms went away with treatment, and he was discharged. Six weeks later, he returned with the same symptoms. There was obvious soft tissue swelling with morning stiffness worse than before. He also reports problems with his bowels but isn’t able to tell you exactly what’s wrong. There are no other changes in his health. He is not taking any medications or over-the-counter drugs and does not want to see a doctor. Are there enough red flags to warrant medical evaluation before resumption of physical therapy intervention?

a. Yes; age, bilateral symptoms, progression of symptoms, report of GI distress

b. No; treatment was effective before—it’s likely that he has done something to exacerbate his symptoms and needs further education about joint protection.

18. A client with a past medical history of kidney transplantation (10 years ago) has been referred to you for a diagnosis of rheumatoid arthritis. His medications include tacrolimus, methotrexate, Fosamax, and Wellbutrin. During the examination, you notice a painless lump under the skin in the right upper anterior chest. There is a loss of hair over the area. What other symptoms should you look for as red flag signs and symptoms in a client with this history?

a. Fever, muscle weakness, weight loss

b. Change in deep tendon reflexes, bone pain

19. A 55-year-old man with a left shoulder impingement also has palpable axillary lymph nodes on both sides. They are firm but movable, about the size of an almond. What steps should you take?

References

1. Siegel, R, Ward, E, Brawley, O, et al. Cancer statistics 2011. CA Cancer J Clin. 2011;61:212–236.

2. Brem, SN, Nabors, LB, Raizer, JJ. Central nervous system cancers, National Comprehensive Cancer Guidelines (2009). Available at http://www.nccn.org/professionals/physician_gls/f_guidelines.asp. [Accessed November 01, 2010].

3. National Cancer Institute (NCI). Annual report: Continued declines in annual cancer rates, 2009. Available at www.nci.nih.gov/. [Accessed Oct 29, 2010].

4. Oeffinger, KC, Mertens, AC, Hudson, MM, et al. Health care of young adult survivors of childhood cancer: a report from the Childhood Cancer Survivor Study. Ann Fam Med. 2004;2:61–70.

5. University of Minnesota Cancer Center. Childhood Cancer Survivor Study (CCSS). Available at http://www.cancer.umn.edu/ltfu. [Accessed Oct. 11, 2010].

6. Hawkins, M. Long-term survivors of childhood cancers: what knowledge have we gained? Available at www.medscape.com/viewarticle/492506. [Accessed Oct. 11, 2010].

7. Tsao, A, Kim, E, Hong, W. Chemoprevention of cancer. CA Cancer J Clin. 2004;54:150–180.

8. Guide to Physical Therapist Practice, ed 2. Alexandria, VA: American Physical Therapy Association, 2003.

9. American Cancer Society (ACS), Cancer prediction and early detection (CPED). Atlanta: ACS, 2010. Available at www.cancer.org. [Accessed Oct. 11, 2010].

10. National Cancer Institute. Cancer Statistics. Available at http://www.nci.nih.gov/statistics/, 2010. [Accessed Oct. 11].

11. Pal, SK, Katheria, V, Hurria, A. Evaluating the older patient with cancer: understanding frailty and the geriatric assessment. CA Cancer J Clin. 2010;60(2):120–132.

12. Ries, LAG, Eisner, MP, Kosary, CL, SEER Cancer Statistics Review. Bethesda, MD: NCI, 1973-1999. Available at http://seer.cancer.gov/csr/1973_1999/. [Accessed September 2002].

13. Bach, PB, Schrag, D, Brawley, OW. Survival of blacks and whites after a cancer diagnosis. JAMA. 2002;287:2106–2113.

14. Institute of Medicine (IOM), Unequal treatment, confronting racial and ethnic disparities in health care. Washington DC: IOM, 2003. Available at http://www.iom.edu/. [[type in search window: Unequal Treatment…]. Accessed Oct. 11, 2010].

15. O’Brien, K. Cancer statistics for Hispanics, 2003. CA Cancer J Clin. 2003;53:208–226.

16. Huerta, EE. Cancer statistics for Hispanics, 2003: good news, bad news, and the need for a health system paradigm change. CA Cancer J Clin. 2003;53:205–207.

16a. Ziogas, A. Clinically relevant changes in family history of cancer over time. JAMA. 2011;306:172–178. [208–210].

17. Sifri, R, Gangadharappa, S, Acheson, L. Identifying and testing for hereditary susceptibility to common cancers. CA Cancer J Clin. 2004;54:309–326.

18. National Society of Genetic Counselors (NSGC). Your family history: your future. Chicago, IL, NSGC. Available at www.nsgc.org. [Accessed Oct. 11, 2010].

19. American Institute for Cancer Research (AICR). Food, nutrition, physical activity and the prevention of cancer: a global perspective. Washington, DC: AICR; 2007.

20. American Institute for Cancer Research (AICR), Expert Panel Report: Summary—food nutrition and the prevention of cancer: a global perspective. Washington, DC: AICR, 2005. Available at http://www.aicr.org/. [Accessed Oct. 10, 2010].

21. Calle, EE, Rodriquez, C, Walker-Thurmond, K, et al. Overweight, obesity, and mortality from cancer in a prospectively studied cohort of U.S. adults. N Engl J Med. 2003;348:1625–1638.

22. Patel, AV, Rodriquez, C, Bernstein, L, et al. Obesity, recreational physical activity, and risk of pancreatic cancer in a large U.S. cohort. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2005;14:459–466.

23. Key, TJ, Schatzkin, A, Willett, WC, et al. Diet, nutrition, and the prevention of cancer. Public Health Nutr. 2004;7:187–200.

24. Roberts, DL. Biological mechanisms linking obesity and cancer risk: new perspectives. Ann Rev Med. 2010;61:301–316.

25. Harriss, DJ. Lifestyle factors and colorectal cancer risk: systematic review and meta-analysis of associations with mass index. Colorectal Dis. 2009;11(6):547–563.

26. Mai, V, Kant, AK, Flood, A, et al. Diet quality and subsequent cancer incidence and mortality in a prospective cohort of women. Int J Epidemiol. 2005;34:54–60.

27. Kabat, GC. Repeated measures of serum glucose and insulin in relationship to postmenopausal breast cancer. Int J Cancer. 2009;125(11):2704–2710.

28. Duggan, C. Associations of insulin resistance and adiponectin with mortality in women with breast cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2011;29(1):32–39. [Epub Nov 29, 2010].

29. Eyre, H, Kahn, R, Robertson, RM. Preventing cancer, cardiovascular disease and diabetes: a common agenda for the ACS, American Diabetes Association, American Heart Association. CA Cancer J Clin. 2004;54:190–207.

30. National Cancer Institute (NCI). Nutrition in cancer care 2010. Available on-line at http://www.cancer.gov/cancertopics/pdq/supportivecare/nutrition/Patient/page1. [Accessed March 7, 2011].

31. American Cancer Society (ACS), Nutrition for people with cancer. Available on-line at www.cancer.org. [Accessed March 7, 2011].

32. American Institute for Cancer Research. Diet and Cancer Materials. Food, Nutrition, Physical Activity and the Prevention of Cancer. Available on-line at www.dietandcancerreport.org. [Accessed March 7, 2011].

33. Renehan, AG. Interpreting the epidemiological evidence linking obesity and cancer. Eur J Cancer. 2010;46(145):2581–2592.

34. Chen, YC, Hunter, D. Molecular epidemiology of cancer. CA Cancer J Clin. 2005;55:45–54.

35. National Cancer Institute, Fact sheet: human papillomaviruses and cancer: questions and answers. Available on-line at http://www.cancer.gov/cancertopics/factsheet/Risk/HPV. [Accessed October 11, 2010].

36. CDC, Sexually transmitted diseases. Genital HPV infection—CDC fact sheet, 2010. Available online at http://www.cdc.gov/std/hpv/stdfact-hpv.htm. [Accessed October 11, 2010].

37. Fleming, DT. Herpes simplex virus type 2 in the United States, 1976 to 1994. N Engl J Med. 1997;337:1105–1160.

38. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Health Statistics. National Vital Statistics Report: Sexually transmitted infections. Hyattsville, MD: CDC; 2009.

39. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), Tracking the hidden epidemics 2000: Trends in STDs in the United States. Hyattsville, MD: CDC, 2000. Available at http://www.cdc.gov/. [Accessed Oct. 10, 2010].

40. Armbruster, C, Dekan, G, Hovorka, A. Granulomatous pneumonitis and mediastinal lymphadenopathy due to photocopier toner dust. Lancet. 1996;348:1518–1519.

41. Gallardo, M, Romero, P, Sanchez-Quevedo, MC, et al. Siderosilicosis due to photocopier toner dust. Lancet. 1994:412–413.

42. US Justice Department. Radiation Exposure Compensation Program. Available at www.usdoj.gov/civil/torts/const/reca/. [Accessed Oct. 10, 2010].

43. National Cancer Institute (NCI), About radiation fallout. report on exposure to iodine 131 from atomic bombs detonated above ground at the nevada test site: fact sheets, a dose calculator, and state and county exposures. Available at rex.nci.nih.gov/INTRFCE_GIFS/radiation_fallout/radiation_131.html, 2010. [Accessed Oct. 10].

44. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), A Feasibility study of the health consequences to the American population from nuclear weapons tests conducted by the United States and other nations. Available at www.cdc.gov/nceh/radiation/fallout/default.htm. [Accessed Oct. 11, 2010].

45. United States Department of Energy, DOE Nevada: Detailed, historical reports on nuclear testing at the Nevada test site. Available at www.nv.doe.gov/news&pubs/publications/historyreports/default.htm. [Accessed Oct. 10, 2010].

46. National Safety Council (NSC), Understanding radiation. Sources of nonionizing radiation, Posted Dec. 2, 2005. Available at http://www.nsc.org/. [Accessed Oct 10, 2010].

47. El Ghissassi, F, Baan, R, Straif, K, et al. A review of human carcinogens. Part D: radiation. Lancet Oncol. 2009;10(8):751–752.

48. Lazovich, D. Indoor tanning and risk of melanoma: a case-control study in a highly exposed population. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2010;19(6):1557–1568.

49. Woo, DK. Tanning beds, skin cancer, and vitamin D: An examination of the scientific evidence and public health implications. Dermatol Ther. 2010;23(1):61–71.

50. Frumkin, H. Agent orange and cancer: an overview for clinicians. CA Cancer J Clin. 2003;53:245–255.

51. Air Force Research Laboratory, Air Force health study. Available at http://www.wpafb.af.mil/AFRL/. [Accessed Oct. 10, 2010].

52. Institute of Medicine (IOM), Reports: veterans and agent orange: update 2008. Available at http://www.iom.edu. [Accessed Oct 30, 2010].

53. Marshall, L, Identifying and managing adverse environmental health effects: taking an exposure history. Can Med Assoc J 2002;166:1049–1054. Available at www.cmaj.ca/cgi/reprint/166/8/1049.pdf. [Accessed Oct. 10, 2010].

54. Omenn, GS, Genomics and prevention: a vision for the future. Medscape Public Health & Prevention. Oct. 10, 2010;3;1. Available at http://www.medscape.com/viewarticle/501299. [Accessed].

55. Lindsey, H. Environmental factors & cancer: research roundup. Oncology Times. 2005;27(4):8–10.

56. Joerger, AC, Fersht, AR. The tumor suppressor p53: from structures to drug discovery. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol. 2010;2(6):a000919.

57. Maslon, MM, Hupp, TR. Drug discovery and mutant p53. Trends Cell Biol. 2010;20(9):542–555.

58. Couzin, J. Choices—and uncertainties—for women with BRCA mutations. Science. 2003;302:592.

59. Rose, PS, Buchowski, JM. Metastatic disease in the thoracic and lumbar spine: evaluation and management. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2011;19(1):37–48.

60. Kitagawa, Y, Fujii, H, Mukai, M, et al. Intraoperative lymphatic mapping and sentinel lymph node sampling in esophageal and gastric cancer. Surg Oncol Clin N Am. 2002;11:293–304.

61. McGarvey, CL. Principles of oncology for the physical therapist. Long Island, NY: Stony Brook University; 2003.

62. Fagan, A. Bone metastases in breast cancer. Rehabil Oncol. 2004;22:23–26.

63. Lipton, A. Bone continuum of cancer. Am J Clin Oncol. 2010;33(3):S1–S7. [Suppl.].

64. Eatock, AM, Scatzlein, A, Kayes, L. Tumour vasculature as a target for anticancer therapy. Cancer Treat Rev. 2000;26:191–204.

65. Diaz, NM, Vrcel, V, Centeno, BA, et al. Modes of benign mechanical transport of breast epithelial cells to axillary lymph nodes. Adv Anat Pathol. 2005;12:7–9.

66. Mankin, HJ, Mankin, CJ, Simon, MA. The hazards of the biopsy revisited. J Bone Joint Surg. 1996;78A:656–663.

67. Springfield, DS, Rosenberg, A. Biopsy: complicated, risky (editorial). J Bone Joint Surg. 1996;78A:639–643.

68. Abdu, WA, Provencher, M. Primary bone and metastatic tumors of the cervical spine. Spine. 1998;23:2767–2777.

69. Austin, JP. Probable causes of recurrence in patients with chordoma and chondrosarcoma of the base of skull and cervical spine. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 1993;25:439–444.

70. Fischbein, NJ. Recurrence of clival chordoma along the surgical pathway. Am J Neuroradiol. 2000;21:578–583.

71. Bergh, P. Prognostic factors in chordoma of the sacrum and mobile spine: a study of 39 patients. Cancer. 2000;88:2122–2134.

72. Slipman, CW. Epidemiology of spine tumors presenting to musculoskeletal physiatrists. Arch Phys Med Rehab. 2003;84:492–495.

73. American Academy of Dermatology (ADD), Melanoma fact sheet 2010. Available at www.aad.org. [Accessed Oct. 11, 2010].

74. American Cancer Society, Skin cancer 2010. Available at www.cancer.org. [Accessed Oct. 30, 2010].

75. Chen, K, Craig, JC, Shumack, S. Oral retinoids for the prevention of skin cancers in solid organ transplant recipients: a systematic review of randomized controlled trials. Br J Dermatol. 2005;152:518–523.

76. Ross, MI. Aid for patients with limb metastases. World Melanoma Update. 1997;1:15.

77. Rigel, DS. The evolution of melanoma diagnosis: 25 years beyond the ABCDs. CA Cancer J Clin. 2010;60(5):301–316.

78. Gudas, S. The physical therapy challenge in disseminated cancer. Oncol Sect News APTA. 1987;5:3.

79. Thomas, SS, Dunbar, EM. Modern multidisciplinary management of brain metastases. Curr Oncol Rep. 2010;12(1):34–40.

80. Jaeckle, KA. Neurological manifestations of neoplastic and radiation-induced plexopathies. Semin Neurol. 2004;24:385–393.

81. Jaeckle, KA. Neurologic manifestations of neoplastic and radiation-induced plexopathies. Semin Neurol. 2010;30(3):254–262.

82. Prasad, D, Schiff, D. Malignant spinal cord compression. Lancet Oncol. 2005;6:15–25.

83. Pigott, KH, Baddeley, H, Maher, EJ. Pattern of disease in spinal cord compression on MRI scan and implications for treatment. Clin Oncol (R Coll Radiol). 1994;6:7–10.

84. Morris, GS. Oncologic emergencies. Acute Care Perspectives. 2007;16(4):1):3–7.

85. Coleman, RE. Management of bone metastases. Oncologist. 2000;5:463–470.

86. Schiff, D. Peer viewpoint. J Support Oncol. 2004;2:398. [401].

87. Abrahm, JL. Assessment and treatment of patients with malignant spinal cord compression. J Support Oncol. 2004;2:377–401.

88. Levack, P, Graham, J, Collie, D, et al. Scottish Cord Compression Study Group. Don’t wait for a sensory level—listen to the symptoms: a prospective audit of the delays in diagnosis of malignant cord compression. Clin Oncol (R Coll Radiol). 2002;14:472–480.

89. Schiff, D. Spinal cord compression. Neurol Clin. 2003;21:67–86.

90. Tatu, B. Physical therapy intervention with oncological emergencies. Rehabil Oncol. 2005;23:4–6.

91. Ampil, FL, Mills, GM, Burton, GV. A retrospective study of metastatic lung cancer compression of the cauda equina. Chest. 2001;120:1754–1755.

92. Orendacova, J, Cizkova, D, Kafka, J, et al. Cauda equina syndrome. Prog Neurobiol. 2001;64:613–637.

93. Bagley, CA, Gokaslan, ZL, Cauda equina syndrome caused by primary and metastatic neoplasms. Neurosurg Focus. 2004:16;6. Available online at http://www.medscape.com/viewarticle/482042_print. [Accessed Oct. 11, 2010].

94. Small, SA, Perron, AD, Brady, WJ. Orthopedic pitfalls: cauda equina syndrome. Am J Emerg Med. 2005;23:159–163.

95. Uchiyama, T, Sakakibara, R, Hattori, T, et al. Lower urinary tract dysfunctions in patients with spinal cord tumors. Neurourol Urodyn. 2002;23:68–75.

96. McCarthy, MJH. Cauda equina syndrome. Factors affecting long-term functional and sphincteric outcome. Spine. 2007;32(2):207–216.

97. Hile, ES. Persistent mobility disability after neurotoxic chemotherapy. Phys Ther. 2010;90(11):1649–1657.

98. Bataller, A, Dalman, J. Paraneoplastic disorders of the central nervous system: update on diagnosis and treatment. Semin Neurol. 2004;24:461–471.

99. Santacroce, L, Paraneoplastic syndromes. eMedicine Specialties, 2010. Available online at www.emedicine.com/med/TOPIC1747.HTM. [Accessed March 7, 2011].

100. Velez, A, Howard, MS. Diagnosis and treatment of cutaneous paraneoplastic disorders. Dermatol Ther. 2010;23(6):662–675.

101. Briani, C. Spectrum of paraneoplastic disease associated with lymphoma. Neurology. 2011;76(8):705–710.

102. Maverakis, E. The etiology of paraneoplastic autoimmunity. Clin Rev Allergy Immunol. Jan 19, 2011. [Epub ahead of print].

103. Farrugia, ME. Myasthenic syndromes. J R Coll Physicians Edinb. 2011;41(1):43–48.

104. Naschitz, JE. Musculoskeletal syndromes associated with malignancy. Curr Opin Rheumatol. 2008;20(1):100–105.

105. Stummvoll, GH, Aringer, M, Machold, KP, et al. Cancer polyarthritis resembling rheumatoid arthritis as a first sign of hidden neoplasms. Scand J Rheumatol. 2001;30:40–44.

106. Martorell, EA, Murray, PM, Peterson, JJ, et al. Palmar fasciitis and arthritis syndrome associated with metastatic ovarian carcinoma: a report of four cases. J Hand Surg. 2004;29A:654–660.

107. Stummvoll, GH, Graninger, WB. Paraneoplastic rheumatism—musculoskeletal diseases as a first sign of hidden neoplasms. Acta Med Austriaca. 2002;29:36–40.

108. Klippel, JH. Primer on the rheumatic diseases, ed 13. Arthritis Foundation, New York: Springer Science Media; 2008.

109. Joines, JD, McNutt, RA, Carey, TS, et al. Finding cancer in primary care outpatients with low back pain: a comparison of diagnostic strategies. J Gen Intern Med. 2001;16:14–29.

110. Deyo, RA, Diehl, AK. Cancer as a cause of back pain: frequency, clinical presentation, and diagnostic strategies. J Gen Intern Med. 1988;3:230–238.

111. Jarvik, J, Deyo, R. Diagnostic evaluation of low back pain with emphasis on imaging. Ann Intern Med. 2002;137:586–597.

112. Ross, MD, Boissonnault, WG. Red flags: to screen or not to screen? J Orthop Sports Phys Ther. 2010;40(11):682–684.

113. Deftos, LJ. Hypercalcemia in malignant and inflammatory diseases. Endocrinol Metab Clin North Am. 2002;31:141–158.

114. Nirenberg, A. Managing hematologic toxicities. Cancer Nursing. 2003;26:32S–37S.

115. Barsevick, A. Energy conservation and cancer-related fatigue. Rehabil Oncol. 2002;20:14–17.

116. National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN), Causes of cancer related fatigue, 2010. Available at www.nccn.org. [Accessed on Oct. 11, 2010].

117. Litterini, AJ, Fieler, VK. The change in fatigue, strength, and quality of life following a physical therapist prescribed exercise program for cancer survivors. Rehabil Oncol. 2008;26(3):11–17.

118. Schmitz, KH, Courneya, KS. American College of Sports Medicine roundtable on exercise guidelines for cancer survivors. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2010;42(7):1409–1426.

119. Blaney, J. The cancer rehabilitation journey: barriers to and facilitators of exercise among patients with cancer-related fatigue. Phys Ther. 2010;90(8):1135–1147.

120. Van Weert, E. Cancer-related fatigue and rehabilitation. Phys Ther. 2010;90(10):1413–1425.

121. Volk, K, Wruble, E. Irradiation side effects and their impact on physical therapy. Acute Care Perspect. 2001;10:11–13.

122. Winningham, ML, McVicar, M, Burke, C. Exercise for cancer patients: guidelines and precautions. Phys Sportsmed. 1986;14:121–134.

123. Goodman, CC, Fuller, K. Pathology: Implications for the physical therapist, ed 3. Philadelphia: WB Saunders; 2009.

124. Jacobs, AL. Adult cancer survivorship: evolution, research, and planning care. CA Cancer J Clin. 2009;59:391–410.

125. Miller, KD, Triano, LR. Medical issues in cancer survivors—a review. Cancer J. 2008;14(6):375–387.

126. Hile, ES. Persistent mobility disability after neurotoxic chemotherapy. Phys Ther. 2010;90(11):1649–1657.

127. Asher, A. Cancer rehabilitation and survivorship: Cedars-Sinai Medical Center experience. Oncol Nurse. 2010;3(6):1):18–21.

128. Shamley, DR. Changes in shoulder muscle size and activity following treatment for breast cancer. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2007;106(1):19–27.

129. Ahles, TA. Candidate mechanisms for chemotherapy-induced cognitive changes. Nat Rev Cancer. 2007;7:192–201.

130. Ferguson, RJ. Management of chemotherapy-related cognitive dysfunction. In: Feuerstein M, ed. Handbook of cancer survivorship. New York: Springer, 2006.

131. Siegel, HJ, Pressey, JG, Current perspectives on the surgical and medical management of soft tissue sarcomas, Medscape 2008: Available at http://www.medscape.com/viewarticle/579883. [Accessed Oct. 13, 2010].

132. Borman, H, Safak, T, Ertoy, D. Fibrosarcoma following radiotherapy for breast cancer: a case report and review of the literature. Ann Plast Surg. 1998;41:201–204.

133. National Cancer Institute (NCI), Treatment statement for health professionals: adult soft tissue sarcoma. Med News 2005. Available at www.meb.unibonn.de/cancer.gov/CDR0000062820.html. [Accessed Oct. 13, 2010].

134. Roll, L. Cancer in children and adolescents. In: Varricchio C, ed. ACS: A cancer source book for nurses. ed 8. Boston: Jones and Bartlett; 2004:229–242.

135. American Cancer Society (ACS), Cancer reference information. overview: osteosarcoma. Available at http://www.cancer.org/docroot/CRI/CRI_2_1x.asp?dt=52. [Accessed Oct. 13, 2010].

136. Maheshwari, AV, Cheng, EY. Ewing sarcoma family of tumors. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2010;18(2):94–107.

137. American Cancer Society (ACS), Cancer Reference information. Detailed guide: Ewing family of tumors. Available at http://www.cancer.org/Cancer/EwingFamilyofTumors/DetailedGuide/index. [Accessed Oct. 12, 2010].

138. Grubb, MR, Currier, BL, Pritchard, DJ, et al. Primary Ewing sarcoma of the spine. Spine. 1994;19:309–313.

139. Lin, PP. Secondary chondrosarcoma. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2010;18(10):608–615.

140. Resnick, D. Diagnosis of bone and joint disorders, ed 4. Philadelphia: WB Saunders; 2002.

141. Payne, WT, Merrell, G. Benign bone and soft tissue tumors of the hand. J Hand Surg. 2010;35A(11):1901–1910.

142. Better outlook for people with brain tumors. Johns Hopkins Med Lett. 2002;14:3.

143. Kasper, D, longo, D, Fauci, A, et al. Harrison’s principles of internal medicine, ed 18. New York: McGraw-Hill; 2011.

144. Volkow, ND. Effects of cell phone radiofrequency signal exposure on brain glucose metabolism. JAMA. 2011;305(8):808–813.

145. Carney, CP, Woolson, RF, Jones, L, et al. Occurrence of cancer among people with mental health claims in an insured population. Psychosom Med. 2004;66:735–743.

146. Hong, WK. Holland-Frei cancer medicine. Shelton, CT: Peoples Medical Publishing House; 2010. [2010].

147. Abu-Shakra, M, Buskila, D, Ehrenfeld, M, et al. Cancer and autoimmunity: autoimmune and rheumatic features in patients with malignancies. Ann Rheum Dis. 2001;60:433–441.

148. Zaidi, A, Vesole, H. Multiple myeloma: an old disease with new hope for the future. CA Cancer J Clin. 2001;51:273–285.

149. Paulson, B, Gudas, S. Multiple myeloma. Rehabil Oncol. 2003;21:8–10.

150. Volker, D. Other cancers: multiple myeloma. In: Varricchio C, ed. ACS: Cancer source book for nurses. ed 8. Boston: Jones and Bartlett; 2004:324–336.

151. Jones, A. Lymphomas. In: Varricchio C, ed. ACS: A cancer source book for nurses. ed 8. Boston: Jones and Bartlett; 2004:265–276.

152. Lim, ST, Levine, AM. Recent advances in acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS)-related lymphoma. CA Cancer J Clin. 2005;55:229–241.

153. Hardell, L, Axelson, O. Environmental and occupational aspects on the etiology of non-Hodgkin lymphoma. Oncol Res. 1998;10:1–5.

154. Gaidano, G, Carbone, A, Dalla-Favera, R. Genetic basis of acquired immunodeficiency syndrome–related lymphomagenesis. J Natl Cancer Inst Monogr. 1998;23:95–100.

155. Aboulafia, AJ, Khan, F, Pankowsky, D, et al. AIDS-associated secondary lymphoma of bone: a case report with review of the literature. Am J Orthop. 1998;27:128–134.

156. Gapstur, SM, Morrow, M, Sellers, TA. Hormone replacement therapy and risk of breast cancer with a favorable histology: results of the Iowa Women’s Health Study. JAMA. 1999;281:2091–2097.

157. Aubuchon, M, Santoro, N. Lessons learned from the WHI: HRT requires a cautious and individualized approach. Geriatrics. 2004;59:22–26.

158. Rossouw, JE, Anderson, GL, Prentice, RL, et al. Risks and benefits of estrogen plus progestin in healthy postmenopausal women: principal results from the Women’s Health Initiative randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2002;288:321–333.

159. Holden, AF. Sweet’s syndrome in association with generalized granuloma annulare in a patient with previous breast carcinoma. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2001;26:668–670.