Screening for Urogenital Disease

A 40-year-old athletic man comes to your clinic for an evaluation of back pain that he attributes to a very hard fall on his back while he was alpine skiing 3 days ago. His chief complaint is a dull, aching costovertebral pain on the left side, which is unrelieved by a change in position or by treatment with ice, heat, or aspirin. He stated that “even the skin on my back hurts.” He has no previous history of any medical problems.

After further questioning, the client reveals that inspiratory movements do not aggravate the pain, and he has not noticed any change in color, odor, or volume of urine output. However, percussion of the costovertebral angle (see Fig. 4-54) results in the reproduction of the symptoms. This type of symptom complex may suggest renal involvement even without obvious changes in urine.

Whether secondary to trauma or of insidious onset, a client’s complaints of flank pain, low back pain, or pelvic pain may be of renal or urologic origin and should be screened carefully through the subjective and objective examinations. Medical referral may be necessary.

Signs and Symptoms of Renal and Urologic Disorders

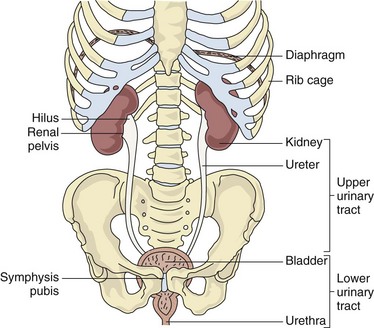

This chapter is intended to guide the physical therapist in understanding the origins and relationships of renal, ureteral, bladder, and urethral symptoms. The urinary tract, consisting of kidneys, ureters, bladder, and urethra (Fig. 10-1), is an integral component of human functioning that disposes of the body’s toxic waste products and unnecessary fluid and expertly regulates extremely complicated metabolic processes. The ureters, bladder, and urethra function primarily as transport vehicles for urine formed in the kidneys. The lower urinary tract is the last area through which urine is passed in its final form for excretion.

Fig. 10-1 Urinary tract structures. The upper urinary tract is composed of the kidneys and ureters while the lower urinary tract is made up of the bladder and urethra. The upper portion of each kidney is protected by the ribcage, and the bladder is partially protected by the symphysis pubis.

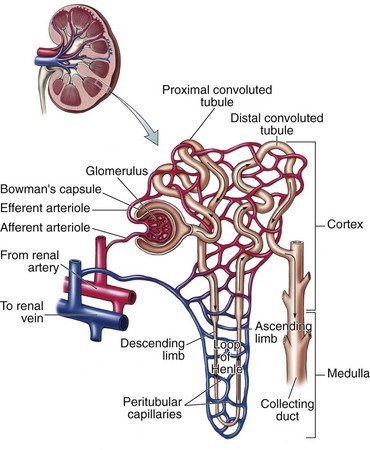

Formation and excretion of urine is the primary function of the renal nephron (the functional unit of the kidney) (Fig. 10-2). Through this process the kidney is able to maintain a homeostatic environment in the body. Besides the excretory function of the kidney, which includes the removal of wastes and excessive fluid, the kidney plays an integral role in the balance of various essential body functions, including the following:

Fig. 10-2 Components of the nephron. The afferent arteriole carries blood to the glomerulus for filtration through Bowman’s capsule and the renal tubular system. (From Herlihy B: The human body in health and illness, ed 4, Philadelphia, 2011, Saunders.)

The failure of the kidney to perform any of these functions results in severe alteration and disruption in homeostasis and signs and symptoms resulting from these dysfunctions (Box 10-1).1

The Urinary Tract

The upper urinary tract consists of the kidneys and ureters. The kidneys are located in the posterior upper abdominal cavity in a space behind the peritoneum (retroperitoneal space) (see Fig. 4-50). Their anatomic position is in front of and on both sides of the vertebral column at the level of T11 to L3. The right kidney is usually lower than the left to accommodate the liver.2

The upper portion of the kidney is in contact with the diaphragm and moves with respiration. The kidneys are protected anteriorly by the ribcage and abdominal organs (see Fig. 4-49) and posteriorly by the large back muscles and ribs. The lower portions of the kidneys and the ureters extend below the ribs and are separated from the abdominal cavity by the peritoneal membrane.

The lower urinary tract consists of the bladder and urethra. From the renal pelvis, urine is moved by peristalsis to the ureters and into the bladder. The bladder, which is a muscular, membranous sac, is located directly behind the symphysis pubis and is used for storage and excretion of urine. The urethra is connected to the bladder and serves as a channel through which urine is passed from the bladder to the outside of the body.

Voluntary control of urinary excretion is based on learned inhibition of reflex pathways from the walls of the bladder. Release of urine from the bladder occurs under voluntary control of the urethral sphincter.

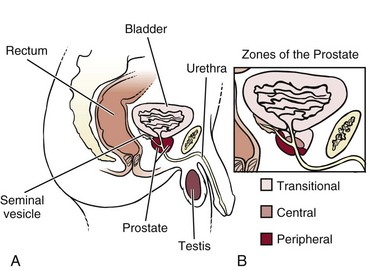

The male genital or reproductive system is made up of the testes, epididymis, vas deferens, seminal vesicles, prostate gland, and penis (Fig. 10-3). These structures are susceptible to inflammatory disorders, neoplasms, and structural defects.

Fig. 10-3 A, The prostate is located at the base of the bladder, surrounding a part of the urethra. It is innervated by T11-L1 and S2-S4 and can refer pain to the sacrum, low back, and testes (see Fig. 10-10). As the prostate enlarges, the urethra can become obstructed, interfering with the normal flow of urine. B, The prostate is composed of three zones. The transitional zone surrounds the urethra as it passes through the prostate. This is a common site for benign prostatic hyperplasia (BPH). The central zone is a cone-shaped section that sits behind the transitional zone. The peripheral zone is the largest portion of the gland and borders the other two zones. This is the most common site for cancer development. Most early tumors do not produce any symptoms because the urethra is not in the peripheral zone. It is not until the tumor grows large enough to obstruct the bladder outlet that symptoms develop. Tumors in the transitional zone, which houses the urethra, may cause symptoms sooner than tumors in other zones.

In males the posterior portion of the urethra is surrounded by the prostate gland, a gland approximately 3.5 cm long by 3 cm wide (about the size of two almonds). Located just below the bladder, this gland can cause severe urethral obstruction when enlarged from a growth or inflammation resulting in difficulty starting a flow of urine, continuing a flow of urine, frequency, and/or nocturia.

The prostate gland is commonly divided into five lobes and three zones. Prostate carcinoma usually affects the posterior lobe of the gland; the middle and lateral lobes typically are associated with the nonmalignant process called benign prostatic hyperplasia (BPH).

Renal and Urologic Pain

Upper Urinary Tract (Renal/Ureteral)

The kidneys and ureters are innervated by both sympathetic and parasympathetic fibers. The kidneys receive sympathetic innervation from the lesser splanchnic nerves through the renal plexus, which is located next to the renal arteries. Renal vasoconstriction and increased renin release are associated with sympathetic stimulation. Parasympathetic innervation is derived from the vagus nerve, and the function of this innervation is not known.

Renal sensory innervation is not completely understood, even though the capsule (covering of the kidney) and the lower portions of the collecting system seem to cause pain with stretching (distention) or puncture. Information transmitted by renal and ureteral pain receptors is relayed by sympathetic nerves that enter the spinal cord at T10 to L1 (see Fig. 3-3).

Because visceral and cutaneous sensory fibers enter the spinal cord in close proximity and actually converge on some of the same neurons, when visceral pain fibers are stimulated, concurrent stimulation of cutaneous fibers also occurs. The visceral pain is then felt as though it is skin pain (hyperesthesia), similar to the condition of the alpine skier who stated that “even the skin on my back hurts.” Renal and ureteral pain can be felt throughout the T10 to L1 dermatomes.

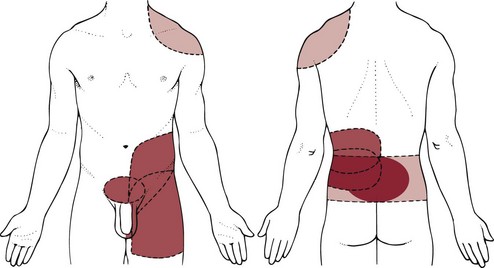

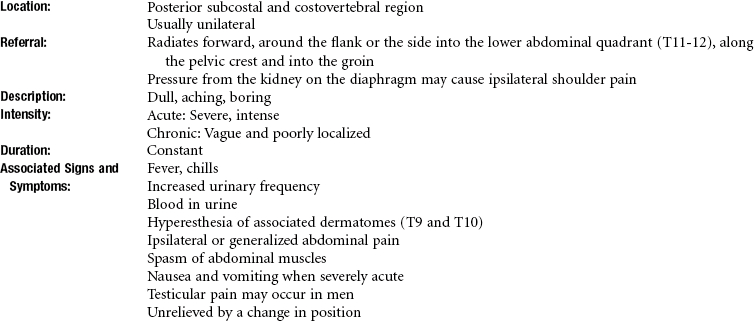

Renal pain (see Fig. 10-7) is typically felt in the posterior subcostal and costovertebral regions. To assess the kidney, the test for costovertebral angle tenderness can be included in the objective examination (see Fig. 4-54).

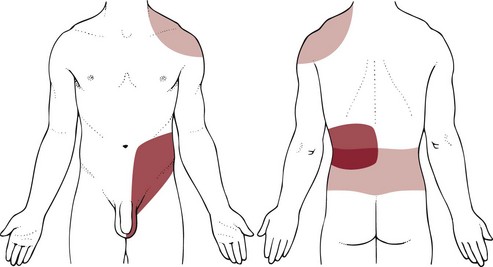

Ureteral pain is felt in the groin and genital area (see Fig. 10-8). With either renal pain or ureteral pain, radiation forward around the flank into the lower abdominal quadrant and abdominal muscle spasm with rebound tenderness can occur on the same side as the source of pain.

The pain can also be generalized throughout the abdomen. Nausea, vomiting, and impaired intestinal motility (progressing to intestinal paralysis) can occur with severe, acute pain. Nerve fibers from the renal plexus are also in direct communication with the spermatic plexus, and because of this close relationship, testicular pain may also accompany renal pain. Neither renal nor urethral pain is altered by a change in body position.

The typical renal pain sensation is aching and dull in nature but can occasionally be a severe, boring type of pain. The constant dull and aching pain usually accompanies distention or stretching of the renal capsule, pelvis, or collecting system. This stretching can result from intrarenal fluid accumulation such as inflammatory edema, inflamed or bleeding cysts, and bleeding or neoplastic growths. Whenever the renal capsule is punctured, a dull pain can also be felt by the client. Ischemia of renal tissue caused by blockage of blood flow to the kidneys results in a constant dull or a constant sharp pain.

Ureteral obstruction (e.g., from a urinary calculus or “stone” consisting of mineral salts) results in distention of the ureter and causes spasm that produces intermittent or constant severe colicky pain until the stone is passed. Pain of this origin usually starts in the costovertebral angle (CVA) and radiates to the ipsilateral lower abdomen, upper thigh, testis, or labium (see Fig. 10-8). Movement of a stone down a ureter can cause renal colic, an excruciating pain that radiates to the region just described and usually increases in intensity in waves of colic or spasm.

Chronic ureteral pain and renal pain tend to be vague, poorly localized, and easily confused with many other problems of abdominal or pelvic origin. There are also areas of referred pain related to renal or ureteral lesions. For example, if the diaphragm becomes irritated because of pressure from a renal lesion, shoulder pain may be felt (see Figs. 3-4 and 3-5). If a lesion of the ureter occurs outside the ureter, pain may occur on movement of the adjacent iliopsoas muscle (see Fig. 8-3).

Abdominal rebound tenderness results when the adjacent peritoneum becomes inflamed. Active trigger points along the upper rim of the pubis and the lateral half of the inguinal ligament may lie in the lower internal oblique muscle and possibly in the lower rectus abdominis. These trigger points can cause increased irritation and spasm of the detrusor and urinary sphincter muscles, producing urinary frequency, retention of urine, and groin pain.3

Pseudorenal Pain

Pseudorenal pain may occur secondary to radiculitis or irritation of the costal nerves caused by mechanical derangements of the costovertebral or costotransverse joints. Disorders of this sort are common in the cervical and thoracic areas, but the most common sites are T10 and T12.4 Irritation of these nerves causes costovertebral pain that can radiate into the ipsilateral lower abdominal quadrant.

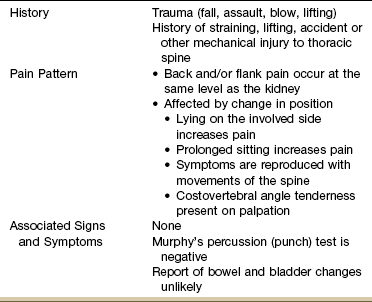

The onset is usually acute with some type of traumatic history such as lifting a heavy object, sustaining a blow to the costovertebral area, or falling from a height onto the buttocks. The pain is affected by body position, and although the client may be awakened at night when assuming a certain position (e.g., sidelying on the affected side), the pain is usually absent on awakening and increases gradually during the day. It is also aggravated by prolonged periods of sitting, especially when driving on rough roads in the car. It may be relieved by changing to another position (Table 10-1).

Radiculitis may mimic ureteral colic or renal pain, but true renal pain is seldom affected by movements of the shoulder or spine. Exerting pressure over the CVA with the thumb may elicit local tenderness of the involved peripheral nerve at its point of emergence, whereas gentle percussion over the angle may be necessary to elicit renal pain, indicating a deeper, more visceral sensation usually associated with an infectious or inflammatory process such as pyelonephritis, perinephric abscess, or other kidney problems.

Fig. 4-54 illustrates percussion over the CVA (Murphy’s percussion or punch test). Although this test is commonly performed, its diagnostic value has never been validated. Results of at least one Finnish study5 suggested that in acute renal colic loin tenderness and hematuria (blood in the urine) are more significant signs than renal tenderness.6

A diagnostic score incorporating independent variables, including results of urinalysis; presence of CVA and renal tenderness; and duration of pain, appetite level, and sex (male versus female), reached a sensitivity of 0.89 in detecting acute renal colic, with a specificity of 0.99 and an efficiency of 0.99.5

Lower Urinary Tract (Bladder/Urethra)

Bladder innervation occurs through sympathetic, parasympathetic, and sensory nerve pathways. Sympathetic bladder innervation assists in the closure of the bladder neck during seminal emission. Afferent sympathetic fibers also assist in providing awareness of bladder distention, pain, and abdominal distention caused by bladder distention. This input reaches the spinal cord at T9 or higher. Parasympathetic bladder innervation is at S2, S3, and S4 and provides motor coordination for the act of voiding. Afferent parasympathetic fibers assist in sensation of the desire to void, proprioception (position sensation), and perception of pain.

Sensory receptors are present in the mucosa of the bladder and in the muscular bladder walls. These fibers are more plentiful near the bladder neck and the junctional area between the ureters and bladder.

Urethral innervation, also at the S2, S3, and S4 level, occurs through the pudendal nerve. This is a mixed innervation of both sensory and motor nerve fibers. This innervation controls the opening of the external urethral sphincter (motor) and an awareness of the imminence of voiding and heat (thermal) sensation in the urethra.

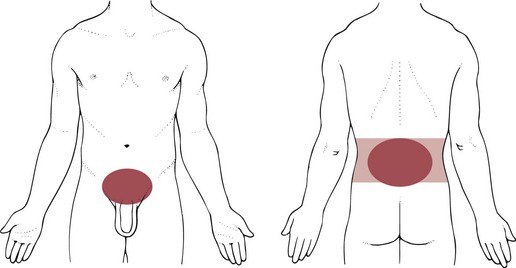

Bladder or urethral pain is felt above the pubis (suprapubic) or low in the abdomen (see Fig. 10-9). The sensation is usually characterized as one of urinary urgency, a sensation to void, and dysuria (painful urination). Irritation of the neck of the bladder or the urethra can result in a burning sensation localized to these areas, probably caused by the urethral thermal receptors. See Box 10-2 for causes of pain outside the urogenital system that present like upper or lower urinary tract pain of either an acute or chronic nature.

Renal and Urinary Tract Problems

Pathologic conditions of the upper and lower urinary tracts can be categorized according to primary causative factors. Inflammatory/infectious and obstructive disorders are presented in this section along with renal failure and cancers of the urinary tract.

When screening for any conditions affecting the kidney and urinary tract system, keep in mind factors that put people at increased risk for these problems (Case Example 10-1). Early screening and detection is recommended based on the presence of these risk factors.7

• Personal or family history of diabetes or hypertension

• Personal or family history of kidney disease, heart attack, or stroke

• Personal history of kidney stones, urinary tract infections, lower urinary tract obstruction, or autoimmune disease

• African, Hispanic, Pacific Island, or Native American descent

• Exposure to chemicals (e.g., paint, glue, degreasing solvents, cleaning solvents), drugs, or environmental conditions

Inflammatory/Infectious Disorders

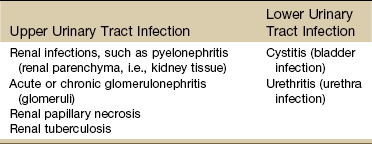

Inflammatory disorders of the kidney and urinary tract can be caused by bacterial infection, by changes in immune response, and by toxic agents such as drugs and radiation. Common infections of the urinary tract develop in either the upper or lower urinary tract (Table 10-2).

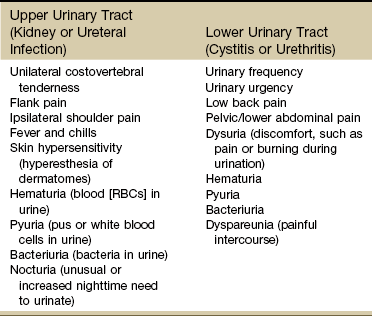

Upper urinary tract infections (UTIs) include kidney or ureteral infections. Lower UTIs include cystitis (bladder infection) or urethritis (urethral infection). Symptoms of UTI depend on the location of the infection in either the upper or lower urinary tract (although, rarely, infection could occur in both simultaneously).

Inflammatory/Infectious Disorders of the Upper Urinary Tract

Inflammations or infections of the upper urinary tract (kidney and ureters) are considered to be more serious because these lesions can be a direct threat to renal tissue itself.

The more common conditions include pyelonephritis (inflammation of the renal parenchyma) and acute and chronic glomerulonephritis (inflammation of the glomeruli of both kidneys). Less common conditions include renal papillary necrosis and renal tuberculosis.

Symptoms of upper urinary tract inflammations and infections are shown in Table 10-3. If the diaphragm is irritated, ipsilateral shoulder pain may occur. Signs and symptoms of renal impairment are also shown in Table 10-4 and if present, are significant symptoms of impending kidney failure.

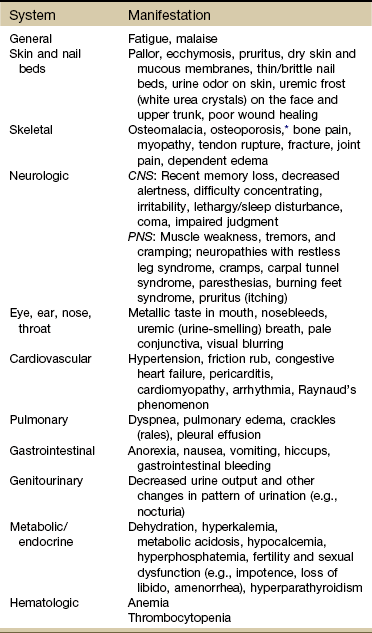

TABLE 10-4

Systemic Manifestations of Chronic Kidney Disease

CNS, Central nervous system; PNS, peripheral nervous system.

*Bone demineralization leads to a condition called renal osteodystrophy.

From Goodman CC, Fuller KS: Pathology: implications for the physical therapist, ed 3, Philadelphia, 2009, WB Saunders.

Inflammatory/Infectious Disorders of the Lower Urinary Tract

Both the bladder and urine have a number of defenses against bacterial invasion. These defenses are mechanisms such as voiding, urine acidity, osmolality, and the bladder mucosa itself, which is thought to have antibacterial properties.

Urine in the bladder and kidney is normally sterile, but urine itself is a good medium for bacterial growth. Interferences in the defense mechanisms of the bladder such as the presence of residual or stagnant urine, changes in urinary pH or concentration, or obstruction of urinary excretion can promote bacterial growth.

Routes of entry of bacteria into the urinary tract can be ascending (most commonly up the urethra into the bladder and then into the ureters and kidney), bloodborne (bacterial invasion through the bloodstream), or lymphatic (bacterial invasion through the lymph system, the least common route).

A lower UTI occurs most commonly in women because of the short female urethra and the proximity of the urethra to the vagina and rectum. The rate of occurrence increases with age and sexual activity since intercourse can spread bacteria from the genital area to the urethra. Chronic health problems, such as diabetes mellitus, gout, hypertension, obstructive urinary tract problems, and medical procedures requiring urinary catheterization, are also predisposing risk factors for the development of these infections.8

Individuals with diabetes are prone to complications associated with UTIs. Staphylococcus infection of the urinary tract may be a source of osteomyelitis, an infection of a vertebral body resulting from hematogenous spread or local spread from an abscess into the vertebra. The infected vertebral body may gradually undergo degeneration and destruction, with collapse and formation of a segmental scoliosis.9

This condition is suspected from the onset of nonspecific low back pain, unrelated to any specific motion. Local tenderness can be elicited, but the initial x-ray finding is negative. Usually, a low-grade fever is present but undetected, or it develops as the infection progresses. This is why anyone with low back pain of unknown origin should have his or her temperature taken, even in a physical therapy setting.

Older adults (both men and women) are at increased risk for UTI. They may present with nonspecific symptoms, such as loss of appetite, nausea, and vomiting; abdominal pain; or change in mental status (e.g., onset of confusion, increased confusion). Watch for predisposing conditions that can put the older client at risk for UTI. These may include diabetes mellitus or other chronic diseases (e.g., Alzheimer’s disease, Parkinson’s disease), immobility, reduced fluid intake, use of incontinence management products (e.g., pads, briefs, external catheters), indwelling catheterization, and previous history of UTI or kidney stones.

Cystitis

Cystitis (inflammation with infection of the bladder), interstitial cystitis (inflammation without infection), and urethritis (inflammation and infection of the urethra) appear with a similar symptom progression (Case Example 10-2).

According to the Interstitial Cystitis Association (ICA), interstitial cystitis (IC), also known as painful bladder syndrome, is a condition that consists of recurring pelvic pain, pressure, or discomfort in the bladder and pelvic region and affects more than 4 million people in the United States.10 IC is often associated with urinary frequency and urgency. Men can be affected by this condition, but the majority of people living with IC are women. Several other disorders are associated with IC including allergies, inflammatory bowel syndrome, fibromyalgia, and vulvitis.11

Bladder pain associated with IC can vary from person to person and even within the same individual and may be dull, achy, or acute and stabbing. Discomfort while urinating also varies from mild stinging to intense burning. Sexual intercourse may ignite pain that lasts for days.11

Clients with any of the symptoms listed for the lower urinary tract in Table 10-3 at presentation should be referred promptly to a physician for further diagnostic workup and possible treatment. Infections of the lower urinary tract are potentially very dangerous because of the possibility of upward spread and resultant damage to renal tissue. Some individuals, however, are asymptomatic, and routine urine culture and microscopic examination are the most reliable methods of detection and diagnosis.

Obstructive Disorders

Urinary tract obstruction can occur at any point in the urinary tract and can be the result of primary urinary tract obstructions (obstructions occurring within the urinary tract) or secondary urinary tract obstructions (obstructions resulting from disease processes outside the urinary tract).

A primary obstruction might include problems such as acquired or congenital malformations, strictures, renal or ureteral calculi (stones), polycystic kidney disease, or neoplasms of the urinary tract (e.g., bladder, kidney).

Secondary obstructions produce pressure on the urinary tract from outside and might be related to conditions such as prostatic enlargement (benign or malignant); abdominal aortic aneurysm; gynecologic conditions such as pregnancy, pelvic inflammatory disease, and endometriosis; or neoplasms of the pelvic or abdominal structures.

Obstruction of any portion of the urinary tract results in a backup or collection of urine behind the obstruction. The result is dilation or stretching of the urinary tract structures that are positioned behind the point of blockage.

Muscles near the affected area contract in an attempt to push urine around the obstruction. Pressure accumulates above the point of obstruction and can eventually result in severe dilation of the renal collecting system (hydronephrosis) and renal failure. The greater the intensity and duration of the pressure, the greater is the destruction of renal tissue.

Because urine flow is decreased with obstruction, urinary stagnation and infection or stone formation can result. Stones are formed because urine stasis permits clumping or precipitation of organic matter and minerals.

Lower urinary tract obstruction can also result in constant bladder distention, hypertrophy of bladder muscle fibers, and formation of herniated sacs of bladder mucosa. These herniated sacs result in a large, flaccid bladder that cannot empty completely. In addition, these sacs retain stagnant urine, which causes infection and stone formation.

Obstructive Disorders of the Upper Urinary Tract

Obstruction of the upper urinary tract may be sudden (acute) or slow in development. Tumors of the kidney or ureters may develop slowly enough that symptoms are totally absent or very mild initially, with eventual progression to pain and signs of impairment. Acute ureteral or renal blockage by a stone (calculus consisting of mineral salts), for example, may result in excruciating, spasmodic, and radiating pain accompanied by severe nausea and vomiting.

Calculi form primarily in the kidney. This process is called nephrolithiasis. The stones can remain in the kidney (renal pelvis) or travel down the urinary tract and lodge at any point in the tract. Strictly speaking, the term kidney stone refers to stones that are in the kidney. Once they move into the ureter, they become ureteral stones.

Ureteral stones are the ones that cause the most pain. If a stone becomes wedged in the ureter, urine backs up, distending the ureter and causing severe pain. If a stone blocks the flow of urine, urine pressure may build up in the ureter and kidney, causing the kidney to swell (hydronephrosis). Unrecognized hydronephrosis can sometimes cause permanent kidney damage.12

The most characteristic symptom of renal or ureteral stones is sudden, sharp, severe pain. If the pain originates deep in the lumbar area and radiates around the side and down toward the testicle in the male and the bladder in the female, it is termed renal colic. Ureteral colic occurs if the stone becomes trapped in the ureter. Ureteral colic is characterized by radiation of painful symptoms toward the genitalia and thighs (see Fig. 10-8).

Since the testicles and ovaries form in utero in the location of the kidneys and then migrate at full term following the pathways of the ureters, kidney stones moving down the pathway of the ureters cause pain in the flank. This pain radiates to the scrotum in males and the labia in females. For the same reason, ovarian or testicular cancer can refer pain to the back at the level of the kidneys.

Renal tumors may also be detected as a flank mass combined with unexplained weight loss, fever, pain, and hematuria. The presence of any amount of blood in the urine always requires referral to a physician for further diagnostic evaluation because this is a primary symptom of urinary tract neoplasm.

Obstructive Disorders of the Lower Urinary Tract

Common conditions of (mechanical) obstruction of the lower urinary tract are bladder tumors (bladder cancer is the most common site of urinary tract cancer) and prostatic enlargement, either benign (BPH) or malignant (cancer of the prostate). An enlarged prostate gland can occlude the urethra partially or completely.

Mechanical problems of the urinary tract result in difficulty emptying urine from the bladder. Improper emptying of the bladder results in urinary retention and impairment of voluntary bladder control (incontinence). Several possible causes of mechanical bladder dysfunction include pelvic floor dysfunction, UTIs, partial urethral obstruction, trauma, and removal of the prostate gland.

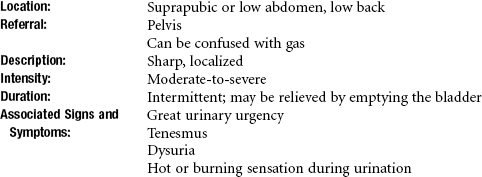

The nerves that carry pain sensation from the prostate do not localize the source of pain very precisely, and therefore it may be difficult for the man to describe exactly where the pain is coming from. Discomfort can be localized in the suprapubic region or in the penis and testicles, or it can be centered in the perineum or rectum (see Fig. 10-10).

Prostatitis: Prostatitis is a relatively common inflammation of the prostate causing prostate enlargement. This condition affects up to 10% of the adult male population, accounting for the 2 million or more men who seek treatment annually in the United States.13,14 It is often disabling, affecting men at any age, but typically found in men ages 40 to 70 years. Acute bacterial prostatitis occurs most often in men under age 35.

The National Institutes of Health (NIH) Consensus Classification of Prostatitis15,16 includes four distinct categories:

| Type I | Acute bacterial prostatitis |

| Type II | Chronic bacterial prostatitis |

| Type III | Chronic prostatitis/chronic pelvic pain syndrome (CP/CPPS) A. Inflammatory B. Noninflammatory |

| Type IV | Asymptomatic inflammatory prostatitis |

Type I is an acute prostatic infection with a uropathogen, often with systemic symptoms of fever, chills, and hypotension. The prostate is inflamed and may block urinary flow without treatment. Type II is characterized by recurrent episodes of documented UTIs with the same uropathogen repeatedly and causes pelvic pain, urinary symptoms, and ejaculatory pain. The source of recurrent infections in the lower urinary tract must be identified and treated.

Chronic (type III, nonbacterial) prostatitis is characterized by pelvic pain for more than 3 of the previous 6 months, urinary symptoms, and painful ejaculation without documented urinary tract infections from uropathogens.

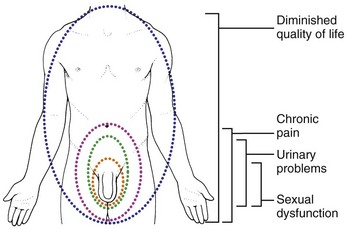

The symptoms of CP/CPPS appear to occur as a result of interplay between psychologic factors and dysfunction in the immune, neurologic, and endocrine systems.17 Studies show a major impact on quality of life, urinary function, and sexual function along with chronic pain and discomfort (Fig. 10-4).18,19

Fig. 10-4 Chronic prostatitis/chronic pelvic pain syndrome (CP/CPPS) can have a serious impact on a man’s quality of life as a result of voiding problems, chronic pelvic pain and discomfort, and sexual dysfunction with painful ejaculation, cramping, or discomfort after ejaculation and infertility.

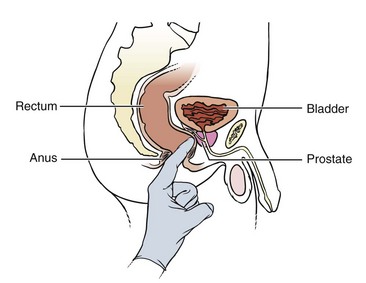

The pain of prostatitis can be exacerbated by sexual activity, and some men describe pain upon ejaculation. A digital rectal examination by the physician will reproduce painful symptoms when the prostate is inflamed or infected (Fig. 10-5).

Fig. 10-5 Digital rectal examination performed by a medical doctor or trained health care professional, such as a nurse practitioner or physician’s assistant, puts pressure on the inflamed prostate reproducing painful symptoms associated with prostatitis.

In men with chronic prostatitis, voiding complaints similar to those caused by BPH are the predominant symptoms. These complaints include urgency, frequency, and nocturia (getting up at nighttime more than once); less frequently, men may complain of difficulty starting the urinary stream or a slow stream.

These symptoms typically differ from symptoms of BPH in that they are associated with some degree of discomfort before, during, or after voiding. Physical or emotional stress and/or irritative components of the diet (e.g., caffeine in coffee, soft drinks) commonly exacerbate chronic prostatitis symptoms.

The causes of prostatitis are unclear. Although it can be the result of a bacterial infection, many men have nonbacterial prostatitis of unknown cause. Risk factors for bacterial prostatitis include some sexually transmitted diseases (e.g., gonorrhea) from unprotected anal and vaginal intercourse, which can allow bacteria to enter the urethra and travel to the prostate.

Other risk factors include bladder outlet obstruction (e.g., stone, tumor, BPH), diabetes mellitus, immunosuppression, and urethral catheterization. Neither prostatitis nor prostate enlargement is known to cause cancer, but men with prostatitis or BPH can develop prostate cancer as well.

The NIH Chronic Prostatitis Symptom Index (NIH-CPSI) provides a valid outcome measure for men with chronic (nonbacterial) prostatitis. The index may be useful in clinical practice, as well as research protocols.20

Anyone with significant symptoms assessed by the NIH-CPSI associated with constitutional symptoms should be rechecked by a physician. Individuals with significant symptoms but no constitutional symptoms and individuals nonresponsive to antibiotics should be assessed by a pelvic floor specialist. The index is available for clinical practice and may be useful for research protocols. It is available online at www.prostatitis.org/symptomindex.html.

A less complete list of questions for screening purposes are most appropriate for men with low back pain and any of the risk factors or symptoms listed for prostatitis and may include the following.

The therapist is reminded in asking these questions to offer clients a clear explanation for any questions asked concerning sexual activity, sexual function, or sexual history. There is no way to know when someone will be offended or claim sexual harassment. It is in your own interest to conduct the interview in the most professional manner possible.

There should be no hint of sexual innuendo or humor injected into any of your conversations with clients at any time. The line of sexual impropriety lies where the complainant draws it and includes appearances of misbehavior. This perception differs broadly from client to client.21

Prostatitis cannot always be cured but can be managed. Correct diagnosis is the key to the management of prostatitis. Screening men with red flag symptoms, history, and risk factors can result in early detection and medical referral.

Physical therapy has been shown to have some potential in helping men with chronic prostatitis. Physical therapy for this problem is more common in the European countries but is gaining support in the United States.22 Other minimally invasive intervention strategies directed toward reducing pelvic floor muscle tone and improving urinary function include electrostimulation, transrectal or transurethral microwave hyperthermia, needle ablation hyperthermia, BOTOX injection, biofeedback, myofascial release, and transrectal mobilization of the pelvic ligaments.23-27

Benign Prostatic Hyperplasia: BPH (enlarged prostate) is a common occurrence in men older than 50. Like all cells in the body, cells in the prostate constantly die and are replaced by new cells. As men age, the ratio of new prostate cells to old prostate cells shifts in favor of lower cell death. With a lower cell turnover, there are more “old” cells than “new” ones and the prostate enlarges, squeezing the urethra and interfering with urination and sexual function. It is unclear why cell replacement is diminished, but it may be related to hormone changes associated with aging.

Prostate enlargement affects about half of all men between ages 60 and 69 and close to 80% of men between ages 70 and 90. Severity of signs and symptoms varies and only about half of men with prostate enlargement have problems noticeable enough to seek treatment.28

Because of the prostate’s position around the urethra (see Fig. 10-3), enlargement of the prostate quickly interferes with the normal passage of urine from the bladder. Sexual function is not usually affected unless prostate surgery is required and sexual dysfunction occurs as a complication. If the prostate is greatly enlarged, chronic constipation may result.

Urination becomes increasingly difficult, and the bladder never feels completely empty. Straining to empty the bladder can stretch the bladder, making it less elastic. The detrusor becomes less efficient, and urine collecting in the bladder can foster urinary tract infections.

If left untreated, loss of bladder tone and damage to the detrusor may not be reversible. Continued enlargement of the prostate eventually obstructs the bladder completely, and emergency measures become necessary to empty the bladder.

Like prostatitis, BPH cannot be cured, but symptoms can be managed with medical treatment. Anyone with undiagnosed symptoms of BPH should seek medical evaluation as soon as possible. Screening questions for an enlarged prostate can include the following.

Prostate Cancer: Prostate cancer is a slow growing form of cancer causing microscopic changes in the prostate in one third of all men by age 50. Carcinoma in situ is present in 50% to 75% of American men by age 75. Most of these changes are latent, meaning they produce no signs or symptoms or they are so slow growing (indolent) that they never cause a health threat.29

Even so, prostate cancer is the most common type of cancer and second leading cause of death among men in this country. Of all the men who are diagnosed with cancer each year, about one third have prostate cancer.30

The number of new diagnosed cases of prostate cancer has dramatically increased over the last two decades (peaking in 1992), probably due to mass screening using a blood test to measure the prostate-specific antigen (PSA). PSA rises in men who have any changes in the prostate (e.g., tumor, infection, enlargement).30 Despite the many controversies over “normal” levels of PSA, this test has shifted the detection of the majority of prostate cancer cases from late-stage to early-stage disease when prostate cancers are more likely to be curable.31

Because more men are living longer and the incidence of prostate cancer increases with age, prostate cancer is becoming a significant health issue. Risk factors include advancing age, family history, ethnicity, and diet. Most men with prostate cancer are older than 65; the disease is rare in men younger than 45.

A man’s risk of prostate cancer is higher than average if his brother or father had the disease. In fact, the more first-degree family members affected, the greater the person’s risk of prostate cancer. It is more common in African-American men compared to white or Hispanic men. It is less common in Asian and Native American men.29

Some studies suggest a diet high in animal fat or meat may be a risk factor. Other risk factors may include low levels of vitamins or selenium; multiple sex partners; viruses; and occupational exposure to chemicals (including farmers exposed to herbicides and pesticides), cadmium, and other metals.29

Early prostate cancer often does not cause symptoms. But prostate cancer can cause any of the signs and symptoms listed in Clinical Signs and Symptoms: Obstruction of the Lower Urinary Tract.

It is often diagnosed when the man seeks medical assistance because of symptoms of lower urinary tract obstruction or low back, hip, or leg pain or stiffness (Case Example 10-3). There are four stages of prostate cancer29:

• Stage I or Stage A: The cancer cannot be felt during a rectal exam. It may be found when surgery is done for another reason, usually for BPH. There is no evidence that the cancer has spread outside the prostate.

• Stage II or Stage B: The tumor is large enough that it can be palpated during a rectal exam or found with a biopsy. There is no evidence that the cancer has spread outside the prostate.

• Stage III or Stage C: The cancer has spread outside the prostate to nearby tissues.

• Stage IV or Stage D: The cancer has spread to lymph nodes or to other parts of the body

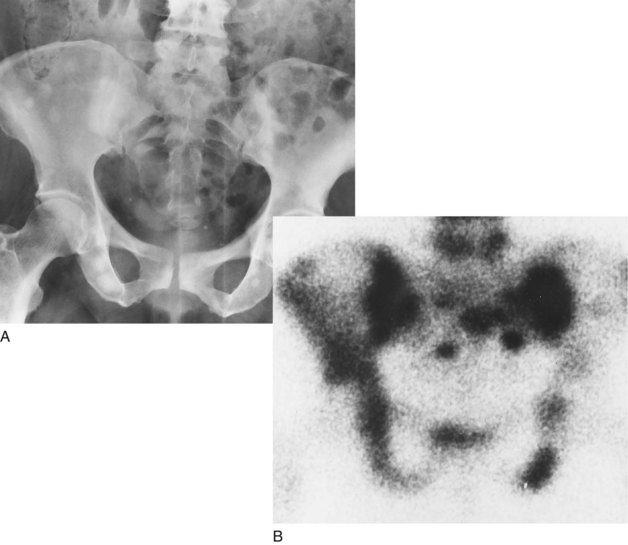

Back pain and sciatica can be caused by cancer metastasis via the bloodstream or the lymphatic system to the bones of the pelvis, spine, or femur. Lumbar pain is predominant, but the thoracolumbar pain can be painful as well, depending on the location of the metastases. Prostate cancer is unique in that bone is often the only clinically detectable site of metastases. The resulting tumors tend to be osteoblastic (bone forming, causing sclerosis), rather than osteolytic (bone lysing) (Fig. 10-6; see also Fig. 13-7).32

Fig. 10-6 Widespread osteoblastic skeletal metastases in prostate adenocarcinoma. A, Anteroposterior radiograph of pelvis shows multiple sclerotic foci. B, Radioisotopic bone scan shows multiple foci of increased uptake in pelvis from the same patient. (From Dorfman HD, Czerniak B: Bone tumors, St. Louis, 1998, Mosby.)

Symptoms of metastatic disease include bone pain, anemia, weight loss, lymphedema of the lower extremities and scrotum, and neurologic changes associated with spinal cord compression when spinal involvement occurs.

Incontinence

Urinary incontinence (UI) is the involuntary leakage of urine. According to the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, incontinence is a vastly underdiagnosed and underreported problem affecting millions of Americans each year. The incidence of incontinence is expected to grow dramatically as the U.S. population continues to age.33

UI is not a disease but rather a symptom of other underlying health conditions, including trauma (e.g., childbirth, incest), diabetes, multiple sclerosis, Parkinson’s disease, spinal injury, spina bifida, surgery, hormonal changes, medications, stroke dysfunction, UTIs, neuromuscular conditions, constipation, or even dietary issues, including caffeine intake.

Incontinent people may restrict their activities for fear of urine loss and concerns about odors in public. This reduction in social activity and impact on lifestyle can have profound effects on psychologic well being and health, including depression, skin breakdown, UTIs, and urosepsis. The therapist can have an important role in the successful treatment of incontinence; therefore screening for this symptom is vital and should be a routine part of the health assessment for all adult clients, especially in a primary care setting.

There are four primary types of UI recognized in adults. These are based on the underlying anatomic or physiologic impairment and include stress, urge, mixed (combination of urge and stress), and overflow.

Stress incontinence occurs when the support for the bladder or urethra is weak or damaged, but the bladder itself is normal. With stress incontinence, pressure applied to the bladder from coughing, sneezing, laughing, lifting, exercising, or other physical exertion increases abdominal pressure, and the pelvic floor musculature cannot counteract the urethral/bladder pressure. This type of incontinence causes 75% of all cases of UI in women and is primarily related to urethral sphincter weakness, pelvic floor weakness, and ligamentous and fascial laxity.

Urge incontinence, now more commonly called overactive bladder, is the involuntary contraction of the detrusor muscle (smooth muscle of the bladder wall) with a strong desire to void (urgency) and loss of urine as soon as the urge is felt. The bladder involuntarily contracts or is unstable, or there may be involuntary sphincter relaxation.34 Urge incontinence is often idiopathic but can be caused by medications, alcohol, bladder infections, bladder tumor, neurogenic bladder, or bladder outlet obstruction.

Overflow incontinence is overdistention of the bladder and the bladder cannot empty completely. Urine leaks or dribbles out so the client does not have any sensation of fullness or emptying.

It may be caused by an acontractile or deficient detrusor muscle, a hypotonic or underactive detrusor muscle secondary to drugs, fecal impaction, diabetes, lower spinal cord injury, or disruption of the motor innervation of the detrusor muscle (e.g., multiple sclerosis).

In men, overflow incontinence is most often secondary to obstruction caused by prostatic hyperplasia, prostatic carcinoma, or urethral stricture. In women, this type of incontinence occurs as a result of obstruction caused by severe genital prolapse or surgical overcorrection of urethral detachment.

The client with incontinence from overflow will report a feeling that the bladder does not empty completely with an urge to void frequently, including at night. Small amounts of urine are lost involuntarily throughout the day and night. There may be a weak stream or flow sometimes described as “dribbling.”

The term functional incontinence describes another type of UI that occurs when the bladder is normal but the mind and body are not working together. Functional incontinence occurs from mobility and access deficits such as being confined to a wheelchair or needing a walker to ambulate.35

Deficits in dexterity, such as weakness from a stroke or neuropathy and loss of motion from arthritis, may keep the individual from getting pants unfastened or panties pulled down in time to avoid an accident. Altered mentation from dementia or Alzheimer’s disease can also contribute to untimely urination without a urologic structural problem.

Causes of incontinence can range from urologic/gynecologic to neurologic, psychologic, pharmaceutical, or environmental. Anything that can interfere with neurologic function or produce obstruction can contribute to UI. There is a high prevalence of stress and urge incontinence in female elite athletes. The frequency of UI is significantly higher in athletes with eating disorders.36

Risk factors for developing UI are listed in Box 10-3. Chronic constipation at any time, but especially during pregnancy, can lead to increased abdominal pressure, which can cause UI. Any condition leading to an enlarged abdomen (e.g., ascites, weight gain, pregnancy) with increased pressure on the bladder can contribute to incontinence.

Chemotherapy, radiation, surgery, and medications can cause disruptions in the cycle of micturition (urination) for many different physiologic reasons. For example, chemotherapy can increase fat deposits and decrease muscle mass, which increase the risk of bowel and bladder dysfunction.

External radiation alters tissue viability in the surrounding area, which can affect circulation to the organs and support from muscle, fascia, ligaments, and tendons.37,38 Radiation can cause fibrotic contracted bladder tissue and damaged sphincter, contributing to UI. Acute radiation prostatocystitis due to external beam radiation can cause frequency, nocturia, urgency, or urge incontinence, as well as hematuria or transient urine retention.39,40

Surgery to remove tumors, lymph nodes, or the prostate can affect bladder control through alterations of blood and lymphatic circulation, innervation, and fascial support. Edema secondary to lymphatic system compromise can increase bladder (and bowel) dysfunction. Brain, spinal cord, or pelvic surgery can affect nervous control of the bowel and bladder.37 Urge incontinence can occur as a result of bladder denervation from surgical injury.39 Postprostatectomy UI (when incontinence is defined as any leak) occurs in up to 70% of all cases, but the rate of urine leak decreases as a result of time, medical treatment, and physical therapy intervention. UI is two times more common after prostatectomy than after radiation; surgical clients are three times more likely to use pads. Recovery occurs in most cases between 6 and 12 months after surgery.39

Incontinence is not a normal part of the aging process. When confronted with UI in an older adult, consider some of the following causes of this disorder: infection, endocrine disorders, atrophic urethritis or vaginitis, restricted mobility, stool impaction (especially in smokers), alcohol or caffeine intake, and medications.

Smoking contributes to constipation and is often accompanied by chronic cough, which stresses the bladder. Some medications can lead to UI or aggravate already existing UI. Medications commonly involved with alterations in urinary continence include anticholinergic agents, calcium channel blockers, diuretics, sedatives, beta-antagonists, and beta-agonists.41

With any kind of incontinence, the onset of cervical spine pain at the same time that UI develops is a red flag. These two findings would suggest there is a protrusion pressing on the spinal cord.

If a medical diagnosis for cervical disk protrusion has been established, referral would not be necessary. However, if incontinence is a new development from the time of the medical evaluation, the physician should be made aware of this information. Cervical spinal manipulation is contraindicated.

Many people are embarrassed about having an incontinence problem. It may help to introduce the subject by making a general statement such as “Many men and women have problems with bladder control. This is an area physical therapists can often help clients with so we routinely ask a few questions about bladder function.”

Chronic Kidney Disease

Symptoms of renal failure generally cannot be mistaken for musculoskeletal disorders that are treated by physical or occupational therapists. However, patients/clients with chronic kidney disease leading to kidney failure may receive treatment in both inpatient and outpatient clinics for primary musculoskeletal lesions. Understanding symptoms associated with kidney disease and recognizing complications associated with dialysis shunt are imperative for the therapist.

Kidney failure exists when the kidneys can no longer maintain the homeostatic balances within the body that are necessary for life. Renal failure is classified as acute or chronic in origin and progression. Acute renal failure refers to the abrupt cessation of kidney activity, usually occurring over a period of hours to a few days. Acute renal failure is often reversible, with return of kidney function in 3 to 12 months.

Chronic renal failure, or irreversible renal failure (also known as end-stage renal disease [ESRD]), is defined as a state of progressive decrease in the ability of the kidney to filter fluids, metabolites, and electrolytes from the body, resulting in eventual permanent loss of kidney function. ESRD is the final stage (stage 5) of chronic kidney disease; it can develop slowly over a period of years or can result from an episode of acute renal failure that does not resolve.

ESRD is a complex condition with multiple systemic complications. Diabetic nephropathy is the primary cause of ESRD, accounting for approximately 40% of newly diagnosed cases of ESRD.42 Individuals with diabetes and ESRD have higher morbidity and mortality rates than individuals with ESRD only.43

Risk factors for ESRD include advancing age, diabetes mellitus, hypertension, chronic urinary tract obstruction and infection (especially glomerulonephritis), and kidney transplantation. Hereditary defects of the kidneys, polycystic kidneys, and glomerular disorders such as glomerulonephritis can also lead to renal failure.

Chronic intake of certain medications and over-the-counter (OTC) drugs is also a factor in the development of renal disease. The increasing availability of OTC drugs has led to consumers treating themselves when they may lack the knowledge to do so safely. Age-related decline in renal function combined with multiple medication use in the aging adult population increases the risk of hepatotoxicity.44 Excessive consumption of acetaminophen and nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs, especially when combined with caffeine and/or codeine, are toxic to the kidneys.45,46

Clinical Signs and Symptoms

Failure of the filtering and regulating mechanisms of the kidney can be either acute (sudden in onset and potentially reversible) or chronic (called uremia, which develops gradually and is usually irreversible).

Individuals with diabetes and ESRD often have autonomic dysfunction and sensorimotor peripheral (uremic) neuropathies affecting the distal extremities. Symptoms tend to be symmetric and more subjective than objective such as restless legs syndrome, cramps, paresthesias, impaired vibration sense, burning feet syndrome, abnormal Achilles reflex, pruritus (itching of the skin), constipation or diarrhea, abdominal bloating, and decreased sweating. When present, a fall in blood pressure is one measurable sign of autonomic nervous system dysfunction.47

Individuals with either type of renal failure develop signs and symptoms characteristic of impaired fluid and waste excretion and altered renal regulation of other body metabolic processes such as pH regulation, RBC production, and calcium-phosphorus balance.

Signs of renal impairment are shown in Table 10-4. The signs of actual renal failure are the same but more pronounced. In most cases of renal failure, urine volume is significantly decreased or absent. Edema becomes severe and can result in heart failure. Renal anemia is usually associated with extreme fatigue and intolerance to normal daily activities, as well as a marked decrease in exercise capacity.48

In addition, the continuous presence of toxic waste products in the bloodstream (urea, creatinine, uric acid) results in damage to many other body systems, including the central nervous system (CNS), peripheral nervous system (PNS), eyes, gastrointestinal (GI) tract, integumentary system, endocrine system, and cardiopulmonary system.

Treatment of renal failure involves several elements designed to replace the lost excretory and metabolic functions of this organ. Treatment options include dialysis, dietary changes, and medications to regulate blood pressure and assist in replacement of lost metabolic functions, such as calcium balance and RBC production.

The choice of treatment options, such as dialysis, transplantation, or no treatment, depends on many factors, including the person’s age, underlying physical problems, and availability of compatible organs for transplantation.49 Untreated or chronic renal failure eventually results in death.

From a screening perspective, the therapist must be alert to the many complications associated with chronic renal failure and dialysis. Watch for signs and symptoms of fluid and electrolyte imbalances (see Chapter 11), dehydration (see Chapter 11), cardiac arrhythmias (see Chapter 6), and depression (see Chapter 3).

Cancers of the Urinary Tract

Bladder cancer is a common, major public health concern that is strongly linked to cigarette smoking.50 It is the fourth most common cancer in men and the tenth most common in women. Bladder cancer is nearly three times more common in men than in women, thus it is typically diagnosed later in women and often at a more advanced stage.51

The exact cause of bladder cancer is not known, but certain risk factors have been identified which increase chances of developing this type of cancer.52

• Tobacco use (cigarette, pipe, and cigar smokers)

• Occupation (exposure to work place carcinogens such as paper, rubber, chemical, leather industries; hairdressers, machinists, metal workers, dental workers, printers, painters, auto workers, textile workers, truck drivers)

• Infections (parasitic, usually in tropical areas of the world)

• Treatment with cyclophosphamide or arsenic (for other cancers)

• Race (whites highest; Asians lowest)

• Gender (men two to three times more likely than women)

• Previous personal history of bladder cancer

• Family history (some association but not clearly defined)53,54

Common symptoms of bladder cancer include blood in the urine, pain during urination, and urinary urgency or the feeling of urinary urgency without resulting urination. Overactive bladder with or without hematuria (blood in the urine) may be a presenting symptom. This symptom is 10 times more common in women than men despite the fact that bladder cancer is more common in men than women.55 These symptoms are not sure signs of bladder cancer, but anyone with these symptoms should be referred to a physician for further follow-up studies.

Measures that have been shown to reduce the risk of developing bladder cancer include cessation of smoking, adequate intake of fluids, intake of cruciferous vegetables, limiting exposure to workplace chemicals, and prompt treatment of bladder infections.

Renal Cancer

Cancer of the kidney (renal cancer) develops most often in people over the age of 40 and has some associated risk factors. Risk factors for renal cancer include

• Smoking (two times the risk as nonsmokers)

• Von Hippel-Lindau (VHL) syndrome (genetic, familial syndrome)

• Occupation (coke oven workers in the iron and steel industry; asbestos and cadmium exposure)

Common symptoms of renal cancer are very similar to those of bladder cancer and require immediate referral for follow-up. These symptoms can include blood in the urine, pain in the side that does not go away, a lump or mass in the side or abdomen, weight loss, fever, and general fatigue or feeling of poor health.56

Testicular Cancer57

The testicles (also called testes or gonads) are the male sex glands. They are located behind the penis in a pouch of skin called the scrotum (see Fig. 10-3). The testicles produce and store sperm and serve as the body’s main source of male hormones. These hormones control the development of the reproductive organs and other male characteristics such as body and facial hair, low voice, wide shoulders, and sexual function.

Testicular cancer is relatively rare and occurs most often in young men between the ages of 15 and 35 years old, although any male can be affected at any time (including infants). According to the National Cancer Institute’s Surveillance, about 8500 men are diagnosed with testicular cancer each year (350 deaths annually).30 The incidence of testicular cancer around the world has doubled in the past 30 to 40 years.

The cause of testicular cancer and even the risk factors remain unknown. Risk is higher than average for boys born with an undescended testicle (cryptorchidism). The cancer risk for boys with this condition is increased even if surgery is done to move the testicle into the scrotum. In the case of unilateral cryptorchidism, the risk of testicular cancer is increased in the normal testicle as well. This fact suggests testicular cancer is due to whatever caused the undescended testicle.58

Having a brother or father with testicular cancer also increases an individual’s risk. Other risk factors may include occupation (e.g., miners, oil and gas workers, leather workers, food and beverage processing workers, janitors, firefighters, utility workers) and human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection.

The risk of testicular cancer among white American men is about 4 times that of African-American men and more than twice that of Asian-American men.59 The risk for Hispanics is between that of Asians and non-Hispanic whites. The reason for this difference is unknown.

The testicular cancer rate has more than doubled among white Americans in the past 40 years but has not changed for African Americans. However, African Americans present with more advanced disease at the time of diagnosis and African-American men with testicular cancer have a higher mortality rate compared with Caucasians.59,60 Worldwide, the risk of developing this disease is highest among men living in the United States and Europe and lowest among African and Asian men.

Clinical Signs and Symptoms

Testicular cancer can be completely asymptomatic. The most common sign is a hard, painless lump in the testicle about the size of a pea. There may be a dull ache in the scrotum and the man may be aware of tender, larger breasts. Other symptoms are listed in the box Clinical Signs and Symptoms: Testicular Cancer.

There are three stages of testicular cancer:

• Stage I: The cancer is confined to the testicle.

• Stage II: The cancer has spread to the retroperitoneal lymph nodes, located in the posterior abdominal cavity below the diaphragm and between the kidneys.

• Stage III: The cancer has spread beyond the lymph nodes to remote sites in the body, including the lungs, brain, liver, and bones.

If found early, testicular cancer is almost always curable.30 The American Cancer Society recommends monthly self-exam of the testicles for adolescents and men, starting at age 15. Testicular self-examination is an effective way of getting to know this area of the body and thus detecting testicular cancer at a very early, curable stage. The self-exam is best performed once each month during or after a warm bath or shower when the heat has relaxed the scrotum (see Appendix D-8).

Men who have been treated for cancer in one testicle have about a 3% to 4% chance of developing cancer in the remaining testicle. If cancer does arise in the second testicle, it is nearly always a new disease rather than metastasis from the first tumor.

Metastases occur via the blood or lymph system. The most common place for the disease spread is to the lymph nodes in the posterior part of the abdomen. Therefore lower back pain is a frequent symptom of later stage testicular cancer (Case Example 10-4). If the cancer has spread to the lungs, persistent cough, chest pain, and/or shortness of breath can occur. Hemoptysis (sputum with blood) may also develop.

Survivors of testicular cancer should be checked regularly by their doctors and should continue to perform monthly testicular self-examinations. Any unusual symptoms should be reported to the doctor immediately. Outcome even after a secondary testicular cancer is still excellent with early detection and treatment.

Physician Referral

The proximity of the kidneys, ureters, bladder, and urethra to the ribs, vertebrae, diaphragm, and accompanying muscles and tendinous insertions often can make it difficult to identify the client’s problems accurately.

Pain related to a urinary tract problem can be similar to pain felt from an injury to the back, flank, abdomen, or upper thigh. The physical therapist is advised to question the client further whenever any of the signs and symptoms listed in Table 10-3 are reported or observed. Further diagnostic testing and medical examination must be performed by the physician to differentiate urinary tract conditions from musculoskeletal problems.

The physical therapist must be able to recognize the systemic origin of urinary tract symptoms that mimic musculoskeletal pain. Many conditions that produce urinary tract pain also include an elevation in temperature, abnormal urinary constituents, and changes in color, odor, or amount of urine.

These types of changes would not be observed or reported with a musculoskeletal condition, and the client may not mention them, thinking these symptoms do not have anything to do with the back, flank, or thigh pain present. The therapist must ask a few screening questions to bring this kind of information to the forefront.

When the physical therapist conducts a Review of Systems, any signs and symptoms associated with renal or urologic impairment should be correlated with the findings of the objective examination and combined with the medical history to provide a comprehensive report at the time of referral to the physician or other health care provider.

Diagnostic Testing

Screening of the composition of the urine is called urinalysis (UA), and UA is the commonly used method of determining various properties of urine. This analysis is actually a series of several tests of urinary components and is a valuable aid in the diagnosis of urinary tract or metabolic disorders.

Normal urinary constituents are shown (see inside front cover: Urine Analysis). Urine cultures are also very important studies in the diagnosis of UTIs. Anyone at risk for chronic kidney disease should be tested for markers of kidney damage. This is done by urinalysis for albumin (protein in the urine) and by blood serum for creatinine (waste product of muscle metabolism).

Various blood studies can be done to assess renal function (see inside front cover: Renal Blood Studies). These studies examine both the serum and cellular components of the blood for specific changes characteristic of renal performance. Substances that must be examined in the serum are those that are a direct reflection of renal function, such as creatinine, and others that are more indirect in renal evaluation, such as blood urea nitrogen (BUN), pH-related substances, uric acid, various ions, electrolytes, and cellular components (RBCs). (For a more in-depth discussion of laboratory values the reader is referred to a more specific source of information.)61-63

Guidelines for Immediate Medical Attention

• The presence of any amount of blood in the urine always requires a referral to a physician. However, the presence of abnormalities in the urine may not be obvious, and a thorough diagnostic analysis of the urine may be needed. Careful questioning of the client regarding urinary tract history, urinary patterns, urinary characteristics, and pain patterns may elicit valuable information relating to potential urinary tract symptoms.

• Presence of cervical spine pain at the same time that urinary incontinence develops. If a diagnosis of cervical disk prolapse has been made, the physician should be notified of these findings; referral may not be necessary, but communication with the physician to confirm this is necessary.

• Client with bowel/bladder incontinence and/or saddle anesthesia secondary to cauda equina lesion.

Guidelines for Physician Referral

Although immediate (emergency) medical attention is not required, medical referral is needed under the following circumstances:

• When the client has any combination of systemic signs and symptoms presented in this chapter. Damage to the urinary tract structures can occur with accident, injury, assault, or other trauma to the musculoskeletal structures surrounding the kidney and urinary tract and may require medical evaluation if the clinical presentation or response to physical therapy treatment suggests it.

For example, the alpine skier discussed at the beginning of the chapter had a dull, aching costovertebral pain on the left side that was unrelieved by a change of position or by ice, heat, or aspirin. His pain is related directly to a traumatic episode, and musculoskeletal injury is a definite possibility in his case. He has no medical history of urinary tract problems and denies any changes in urine or pattern of urination. Because the pain is constant and unrelieved by usual measures and the location of the pain is approximate to renal structures, a medical follow up and urinalysis would be recommended.

Clues Suggesting Pain of Renal/Urologic Origin

• In men, back pain accompanied by burning on urination, difficulty in urination, or fever may be associated with prostatitis; usually in such a case, there is no limitation of back motion and no muscle spasm (until symptoms progress, causing muscle guarding and splinting)

• Change in urinary pattern such as increased or decreased frequency, change in flow of urine stream (weak or dribbling), and increased nocturia

• Presence of constitutional symptoms, especially fever and chills; pain is constant (may be dull or sharp, depending on the cause)

• Pain is unchanged by altering body position; side bending to the involved side and pressure at that level is “more comfortable” (may reduce pain but does not eliminate it)

• Neither renal nor urethral pain is altered by a change in body position; pseudorenal pain from a mechanical cause can be relieved by a change in position

• True renal pain is seldom affected by movements of the spine

• Straight leg–raising test is negative with renal colic appearing as back pain

• Back pain at the level of the kidneys in a woman with previous breast or uterine cancer (ovarian cancer)

• Assessment for pseudorenal pain is negative (see Table 10-1)

1. Percussion of the costovertebral angle that results in the reproduction of symptoms:

2. Renal pain is aggravated by:

3. Important functions of the kidney include all the following except:

a. Formation and excretion of urine

b. Acid-base and electrolyte balance

4. Who should be screened for possible renal/urologic involvement?

5. What do the following terms mean?

6. What is the difference between urge incontinence and stress incontinence?

7. What is the significance of “skin pain” over the T9/T10 dermatomes?

8. How do you screen for possible prostate involvement in a man with pelvic/low-back pain of unknown cause?

9. Explain why renal/urologic pain can be felt in such a wide range of dermatomes (i.e., from the T9 to L1 dermatomes).

10. What is the mechanism of referral for urologic pain to the shoulder?

References

1. Cannon, J. Recognizing chronic renal failure, the sooner, the better. Nursing 2004. 2004;34(1):50–53.

2. Netter, FH. Atlas of human anatomy, ed 5. Philadelphia: WB Saunders; 2010.

3. Simons, DG, Travell, JG, Simons, LS. ed 2. Travell & Simons’ myofascial pain and dysfunction: the trigger point manual, vol 1. Baltimore: Williams & Wilkins, 1999.

4. Smith, DR, Raney, FL, Jr. Radiculitis distress as a mimic of renal pain. J Urol. 1976;116:269.

5. Eskelinen, M. Usefulness of history-taking, physical examination and diagnostic scoring in acute renal colic. Eur Urol. 1998;34(6):467–473.

6. Houppermans, RP, Brueren, MM. Physical diagnosis—pain elicited by percussion in the kidney area. Ned Tijdschr Geneeskd. 2001;145(5):208–210.

7. National Kidney Foundation. K/DOQI clinical practice guidelines for chronic kidney disease: evaluation, classification, and stratification. Available online at http://www.kidney.org/professionals. [Accessed January 1, 2011].

8. Banishing urinary tract infections. Harvard Women’s Health Watch. 2002;10(4):4–5.

9. Cailliet, R. Low back pain syndrome, ed 5. Philadelphia: FA Davis; 1995.

10. Interstitial Cystitis Association (ICA). About interstitial cystitis. Available online at http://www.ichelp.org/. [Accessed Feb. 2, 2011].

11. Diagnosing and treating interstitial cystitis. Harvard Women’s Health Watch. 2003;10(12):3.

12. Medical conditions, coping with kidney stones. Harvard Women’s Health Watch. 2001;9(4):4–5.

13. Gurunadha Rao Tunuguntla, HS, Evans, CP. Management of prostatitis. Prostate Cancer Prostatic Dis. 2002;5(3):172–179.

14. Alexander, RB, Treatment of chronic prostatitis. Nat Clin Pract Urol. 2004;1;1:2–3. Available online http://www.medscape.com/viewarticle/494378. [Accessed January 3, 2011].

15. Krieger, JN. NIH consensus definition and classification of prostatitis. JAMA. 1999;282(3):236–237.

16. Schaeffer, AJ. Classification (Traditional and National Institutes of Health) and demographics of prostatitis. Urology. 2002;60:5–7.

17. Pontari, MA, Ruggieri, MR. Mechanisms in prostatitis/chronic pelvic pain syndrome. J Urol. 2004;172(3):839–845.

18. Tripp, DA, Curtis, NJ, Landis, JR, et al. Predictors of quality of life and pain in chronic prostatitis/chronic pelvic pain syndrome: findings from the National Institutes of Health Chronic Prostatitis Cohort Study. BJU. 2004;94(9):1279–1282.

19. Schultz, PL, Donnell, RF. Prostatitis: the cost of disease and therapies to patients and society. Curr Urol Rep. 2004;5(4):317–319.

20. Litwin, MS, McNaughton-Collins, M, Fowler, FL, Prostatitis: The National Institutes of Health Chronic Prostatitis Symptoms Index (NIH-CPSI). Smithshire, IL: The Prostatitis Foundation, 2002. Available online at http://www.prostatitis.org/symptomindex.html. [Accessed January 03, 2011].

21. Rex, L. Evaluation and treatment of somatovisceral dysfunction of the gastrointestinal system. Edmonds, WA: URSA Foundation; 2004.

22. Cornel, EB, van Haarst, EP. Chronic pelvic pain syndrome type 3 successfully treated with biofeedback physical therapy (Abstract). Presented at the American Urological Association 2004 Annual Meeting, May 8–13, 2004, San Francisco, CA. Available online at http://www.prostatitis.org/AmericanUrologicalMeeting04.html. [Accessed January 3, 2011].

23. Zvara, P, Folsom, JB, Plante, MK. Minimally invasive therapies for prostatitis. Curr Urol Rep. 2004;5(4):320–326.

24. Sokolov, AV. Transrectal microwave hyperthermia in the treatment of chronic prostatitis. Urologiia. 2003;5:20–26.

25. Wehbe, SA. Minimally invasive therapies for chronic pelvic pain syndrome. Curr Urol Rep. 2010;11(4):276–285.

26. Murphy, AB. Chronic prostatitis: management strategies. Drugs. 2009;69(1):71–84.

27. Kastner, C. Update on minimally invasive therapy for chronic prostatitis/chronic pelvic pain syndrome. Curr Urol Rep. 2008;9(4):333–338.

28. Sheeler, R. Enlarged prostate. Know when to seek treatment. Available online at http://www.mayoclinic.com/health/prostate-cancer/DS00043. [Accessed January 3, 2011].

29. National Cancer Institute. Prostate cancer. Available online at http://www.nci.nih.gov/cancertopics/types/prostate. [Accessed January 03, 2011].

30. Jemal, A. Cancer statistics, 2010. CA Cancer J Clin. 2010;60(5):277–300.

31. Carroll, PR, Nelson, WG, Report to the nation on prostate cancer: introduction. Medscape Hematology-Oncology. 2004:7;2. Available online at http://www.medscape.com/viewarticle/489635. [Accessed January 3, 2011.].

32. Logothetis, CJ, Lin, SH. Osteoblasts in prostate cancer metastasis to bone. Nat Rev Cancer. 2005;5(1):21–28.

33. U.S. Department of Health & Human Services. Diseases and conditions. Accessed January 7, from http://www.hhs.gov/.

34. Shafik, A, Shafik, IA. Overactive bladder inhibition in response to pelvic floor muscle exercises. World J Urol. 2003;20(6):374–377.

35. Schultz, JM. Urinary incontinence. Solving a secret problem. Nursing 2003. 2003;33(11):5–10. [Suppl].

36. Bo, K, Borgen, JS. Prevalence of stress and urge urinary incontinence in elite athletes and controls. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2001;33(11):1797–1802.

37. Hulme, J. Regaining bowel and bladder control after cancer. Missoula, MT: Phoenix Publishers; 2003.

38. D’Amico, AV. Surrogate end point for prostate cancer-specific mortality after radical prostatectomy or radiation therapy. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2003;95(18):1376–1383.

39. Grise, P, Thurman, S, Urinary incontinence following treatment of localized prostate cancer. Cancer Control. 2002;8;6:532–539. Available online at http://www.medscape.com/viewarticle/423513. [Accessed January 3, 2011].

40. Wakamatsu, MM. Better bladder and bowel control. Boston: Harvard Medical School; 2009.

41. Yim, PS, Peterson, AS. Urinary incontinence. Postgrad Med. 1996;99(5):137–150.

42. Burrows, NR. Incidence of end-stage renal disease attributed to diabetes among persons with diagnosed diabetes in the United States and Puerto Rico. MMWR. 2010;59(42):1361–1366.

43. Evans, N, Forsyth, E. End-stage renal disease in people with type 2 diabetes: systemic manifestations and exercise implications. Phys Ther. 2004;84(5):454–463.

44. Peterson, GM. Selecting nonprescription analgesics. Am J Ther. 2005;12(1):67–79.

45. Elseviers, MM, De Broe, ME. Analgesic abuse in the elderly. Renal sequelae and management. Drugs Aging. 1998;12(5):391–400.

46. National Kidney Foundation (NKF). Can analgesics hurt kidneys? Available online at http://www.kidney.org/atoz/atozPrint.cfm?id=23. [Accessed January 3, 2011.].

47. Malik, J. Understanding the dialysis access steal syndrome: a review of the etiologies, diagnosis, prevention, and treatment strategies. J Vasc Access. 2008;9(3):155–166.

48. Holub, C, Lamont, M. The reliability of the six-minute walk test in patients with end stage renal disease. Acute Care Perspect. 2002;11(4):8–11.

49. Paton, M. Continuous renal replacement therapy. Nursing2003. 2003;33(6):40–50.

50. Best treatments for beating bladder cancer. Johns Hopkins Med Lett. 2004;15(1):6–7.

51. Bladder cancer in women: no time to wait. Harvard Women’s Health Watch. 2004;11(7):3–5.

52. Jacobs, BL. Bladder cancer in 2010: How far have we come? CA Cancer J Clin. 2010;60(4):244–272.

53. National Cancer Institute. What you need to know about bladder cancer. Available online at www.cancer.gov/cancertopics/wyntk/bladder. [Accessed January 3, 2011].

54. Ongoing care of patients after primary treatment for their cancer: genitourinary cancers, bladder and kidney. CA Cancer J Clin. 2003;53(3):190–191.

55. Weiss, J. Refractory overactive bladder without hematuria: a presenting symptom of bladder cancer. Presentation at the joint annual meeting of the International Continence Society (ICS) and the International Urogynecological Association (IUA). August 23-27, 2010. Available online at https://www.icsoffice.org/Abstracts/Publish/105/000348.pdf. [Accessed December 2, 2010].

56. National Cancer Institute. What you need to know about kidney cancer. Available online at www.cancer.gov/cancertopics/wyntk/kidneys. [Accessed January 3, 2011].

57. American Cancer Society. Detailed guide: testicular cancer. What are the risk factors for testicular cancer? Available online at http://www.cancer.org. [Accessed January 3, 2011].

58. American Cancer Society. Testicular cancer. Available online at http://www.cancer.org/Cancer/TesticularCancer/DetailedGuide/testicular-cancer-risk-factors. [Accessed Feb 2, 2011].

59. Gajendran, VK. Testicular cancer patterns in African-American men. Urology. 2005;66(3):602–605.

60. Powe, BD. Testicular cancer among African American college men. Am J Mens Health. 2007;1(1):73–80.

61. Goodman, CC, Fuller, K. Pathology: implications for the physical therapist, ed 3. Philadelphia: WB Saunders; 2009.

62. Lab Values Interpretation Resources. Acute Care Section—APTA Task Force on Lab Values, 2008. Available online at www.acutept.org. [[members only]. Accessed January 3, 2011].

63. Irion, GL. Lab values update. Acute Care Perspect. 2004;13(1):1. [3–5].

64. Sherburn, M, Guthrie, JR, Dudley, EC, et al. Is incontinence associated with menopause? Obstet Gynecol. 2001;98(4):628–633.

Key Points to Remember

Key Points to Remember