Screening for Immunologic Disease

Immunology, one of the few disciplines with a full range of involvement in all aspects of health and disease, is one of the most rapidly expanding fields in medicine today. Staying current is difficult at best, considering the volume of new immunologic information generated by clinical researchers each year. The information presented here is a simplistic representation of the immune system, with the main focus on screening for immune-induced signs and symptoms mimicking neuromuscular or musculoskeletal dysfunction.

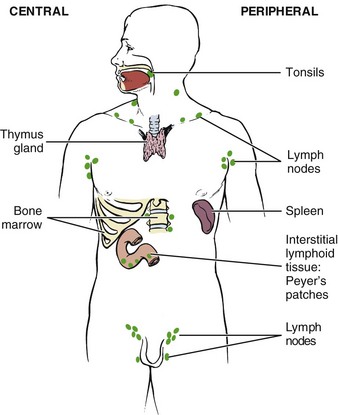

Immunity denotes protection against infectious organisms. The immune system is a complex network of specialized organs and cells that has evolved to defend the body against attacks by “foreign” invaders. Immunity is provided by lymphoid cells residing in the immune system. This system consists of central and peripheral lymphoid organs (Fig. 12-1).

Fig. 12-1 Major organs of the immune system. Two-thirds of the immune system resides in the intestines (intestinal lymphoid tissue), emphasizing the importance of diet and nutrition on immune system function.

By circulating its component cells and substances, the immune system maintains an early warning system against both exogenous microorganisms (infections produced by bacteria, viruses, parasites, and fungi) and endogenous cells that have become neoplastic.

Immunologic responses in humans can be divided into two broad categories: humoral immunity, which takes place in the body fluids (extracellular) and is concerned with antibody and complement activities, and cell-mediated or cellular immunity, primarily intracellular, which involves a variety of activities designed to destroy or at least contain cells that are recognized by the body as being alien and harmful. Both types of responses are initiated by lymphocytes and are discussed in the context of lymphocytic function.

Using the Screening Model

As always in the screening evaluation of any client, the medical history is the most important variable, followed by any red flags in the clinical presentation and an assessment of associated signs and symptoms. Many immune system disorders have a unique chronology or sequence of events that define them. When the immune system may be involved, some important questions to ask include the following:

• How long have you had this problem? (acute versus chronic)

• Has the problem gone away and then recurred?

• Have additional symptoms developed or have other areas become symptomatic over time?

Past Medical History

As mentioned, the family history is important when assessing the role of the immune system in presenting signs and symptoms. Persons with fibromyalgia or chronic pain often have a family history of alcoholism, depression, migraine headaches, gastrointestinal (GI) disorders, or panic attacks.

Clients with systemic inflammatory disorders may have a family history of an identical or related disorder such as rheumatoid arthritis (RA), systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE), autoimmune thyroid disease, multiple sclerosis (MS), or myasthenia gravis (MG). Other rheumatic diseases that are often genetically linked include seronegative spondyloarthropathy.

The seronegative spondyloarthropathies include a wide range of diseases linked by common characteristics such as inflammatory spine involvement (e.g., sacroiliitis, spondylitis), asymmetric peripheral arthritis, enthesopathy, inflammatory eye disease, and musculoskeletal and cutaneous features. All of these changes occur in the absence of serum rheumatoid factor (RF), which is present in about 85% of people with RA.1

This group of diseases includes ankylosing spondylitis (AS), reactive arthritis (ReA; such as Reiter’s syndrome), psoriatic arthritis (PsA), and arthritis associated with inflammatory bowel disease (IBD; such as Crohn’s disease or ulcerative colitis).

A recent history of surgery may be indicative of bacterial or reactive arthritis, which requires immediate medical evaluation.

Risk Factor Assessment

The cause and risk factors for many conditions related to immune system dysfunction remain unknown. Past medical history with a positive family history for systemic inflammatory or related disorders may be the only available red flag in this area.

Clinical Presentation

Symptoms of rheumatic disorders often include soft tissue and/or joint pain, stiffness, swelling, weakness, constitutional symptoms, Raynaud’s phenomenon, and sleep disturbances. Inflammatory disorders, such as RA and polymyalgia rheumatica (PMR), are marked by prolonged stiffness in the morning lasting more than 1 hour. This stiffness is relieved with activity, but it recurs after the person sits down and subsequently attempts to resume activity. This is referred to as the gel phenomenon.

Specific arthropathies have a predilection for involving specific joint areas. For example, involvement of the wrists and proximal small joints of the hands and feet is a typical feature of RA. RA tends to involve joint groups symmetrically, whereas the seronegative spondyloarthropathies tend to be asymmetric. PsA often involves the distal joints of the hands and feet.1

In anyone with swelling, especially single-joint swelling, it is necessary to distinguish whether this swelling is articular (as in arthritis), is periarticular (as in tenosynovitis), involves an entire limb (as with lymphedema), or occurs in another area (such as with lipoma or palpable tumors). The therapist will need to assess whether the swelling is intermittent, persistent, symmetric, or asymmetric and whether the swelling is minimal in the morning but worse during the day (as with dependent edema).

Generalized weakness is a common symptom of individuals with immune system disorders in the absence of muscle disease. If the weakness involves one limb without evidence of weakness elsewhere, a neurologic disorder may be present. Anyone having trouble performing tasks with the arms raised above the head, difficulty climbing stairs, or problems arising from a low chair may have muscle disease.

Nail bed changes are especially indicative of underlying inflammatory disease. For example, small infarctions or splinter hemorrhages (see Fig. 4-34) occur in endocarditis and systemic vasculitis. Characteristics of systemic sclerosis and limited scleroderma include atrophy of the fingertips, calcific nodules, digital cyanosis, and sclerodactyly (tightening of the skin). Dystrophic nail changes are characteristic of psoriasis. Spongy synovial thickening or bony hypertrophic changes (Bouchard’s nodes) are present with RA and other hand deformities.

Associated Signs and Symptoms

With few risk factors and only the family history to rely upon, the clinical presentation is very important. Most of the immune system conditions and diseases are accompanied by a variety of associated signs and symptoms. Disease progression is common with different clinical signs and symptoms during the early phase of illness compared with the advanced phase.

Review of Systems

With many problems affecting the immune system, taking a step back and reviewing each part of the screening model (history, risk factors, clinical presentation, associated signs and symptoms) may be the only way to identify the source of the underlying problem. Remember to review Box 4-19 during this process.

For anyone with new onset of joint pain, a review of systems should include questions about symptoms or diagnoses involving other organ systems. In particular, the presence of dry, red, or irritated and itching eyes; chest pain with dyspnea; urethral or vaginal discharge; skin rash or photosensitivity; hair loss; diarrhea; or dysphagia should be assessed.

Immune System Pathophysiology

Immune disorders involve dysfunction of the immune response mechanism, causing overresponsiveness or blocked, misdirected, or limited responsiveness to antigens. These disorders may result from an unknown cause, developmental defect, infection, malignancy, trauma, metabolic disorder, or drug use. Immunologic disorders may be classified as one of the following:

Immunodeficiency Disorders

When the immune system is underactive or hypoactive, it is referred to as being immunodeficient or immunocompromised such as occurs in the case of anyone undergoing chemotherapy for cancer or taking immunosuppressive drugs after organ transplantation.

Acquired Immunodeficiency Syndrome

Human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) is a cytopathogenic virus that causes acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS). HIV has been identified as the causative agent, its genes have been mapped and analyzed, drugs that act against it have been found and tested, and vaccines against the HIV infection have been under development.

Acquired refers to the fact that the disease is not inherited or genetic but develops as a result of a virus. Immuno refers to the body’s immunologic system, and deficiency indicates that the immune system is underfunctioning, resulting in a group of signs or symptoms that occur together called a syndrome.

People who are HIV-infected are vulnerable to serious illnesses called opportunistic infections or diseases, so named because they use the opportunity of lowered resistance to infect and destroy. These infections and diseases would not be a threat to most individuals whose immune systems functioned normally. Pneumocystis carinii pneumonia (PCP) continues to be a major cause of morbidity and mortality in the AIDS population.

HIV infection is the fifth leading cause of death for people who are between 25 and 44 years old in the United States. Each year, about 2 million people worldwide die of AIDS. African Americans represent about 12% of the total US population but makeup over half of all AIDS cases reported. AIDS is the leading cause of death for African-American men between the ages of 35 and 44. Overall estimates are that 850,000 to 950,000 US residents are living with HIV infection, one-quarter of whom are unaware of their infection. Approximately 56,000 new HIV infections occur each year in the United States, and approximately 2.7 million new HIV cases occur each year worldwide (Box 12-1).2

Risk Factors: Population groups at greatest risk include commercial sex workers (prostitutes) and their clients, men having sex with men, injection drug users (IDUs), blood recipients, dialysis recipients, organ transplant recipients, fetuses of HIV-infected mothers or babies being breast-fed by an HIV-infected mother, and people with sexually transmitted diseases (STDs). The latter group is estimated to have a 3 to 5 times higher risk for HIV infection compared with those having no STDs.

The rate of new cases of HIV among bisexual men of all races has started to rise again after a period of relative stability. Experts suggest the increase is due to erosion of safe sex practices referred to as prevention fatigue. African Americans (both men and women) are still 8 times as likely as whites to contract HIV, although the rate of newly diagnosed HIV infections among African Americans is slowly declining.3

Transmission: Transmission of HIV occurs according to the following descending hierarchy4:

• Both male-to-male sexual contact and injection drug use

• High-risk heterosexual contact (with someone of the opposite sex with HIV/AIDS or a risk factor for HIV)

Transmission occurs through horizontal transmission (from either sexual contact or parenteral exposure to blood and blood products) or through vertical transmission (from HIV-infected mother to infant). HIV is not transmitted through casual contact, such as the shared use of food, towels, cups, razors, or toothbrushes, or even by kissing. Despite substantial advances in the treatment of HIV, the number of new infections has not decreased in the past 10 years. Prevention of infection transmission by reduction of behaviors that might transmit HIV to others is critical.5

Transmission always involves exposure to some body fluid from an infected client. The greatest concentrations of virus have been found in blood, semen, cerebrospinal fluid, and cervical/vaginal secretions. HIV has been found in low concentrations in tears, saliva, and urine, but no cases have been transmitted by these routes. Breast-feeding is a route of HIV transmission from an HIV-infected mother to her infant. The reduction of HIV transmission through breast milk remains a challenge in many resource-poor settings.6,7

Any injectable drug, legal or illegal, can be associated with HIV transmission. It is not injection drug use that spreads HIV but the sharing of HIV-infected intravenous (IV) drug needles among individuals. Despite the perception that only IV injection is dangerous, HIV also can be transmitted through subcutaneous and intramuscular injection. Use of needles contaminated with blood for tattooing or body piercing are included in this category.

Public health organizations have changed their terminology, substituting the abbreviation IDU (injection drug user) for the earlier term IVDU (IV drug user). IDUs who sterilize their drug paraphernalia with a 1 : 10 solution of bleach to water before passing the needles are less likely to spread HIV. For further information regarding this or other HIV/AIDS-related questions, contact the CDC-INFO (formerly the CDC National AIDS Hotline) 24 hours/day, 7 days a week, at 1-800-CDC-INFO (1-800-232-4636).

Blood and Blood Products: Parenteral transmission occurs when there is direct blood-to-blood contact with a client infected with HIV. This can occur through sharing of contaminated needles and drug paraphernalia (“works”), through transfusion of blood or blood products, by accidental needlestick injury to a health care worker, or from blood exposure to nonintact skin or mucous membranes. Health care workers who have contact with clients with AIDS and who follow routine instructions for self-protection are a very low risk group.

Almost all persons with hemophilia born before 1985 have been infected with HIV. Heat-treated factor concentrates, involving a method of chemical and physical processes that completely inactivate HIV, became available in 1985, effectively eliminating the transmission of HIV to anyone with a clotting disorder who is receiving blood or blood products.

The risk for acquiring HIV infection through blood transfusion today is estimated conservatively to be one in 1.5 million, based on 2007-2008 data.8 A blood center in Missouri discovered that blood components from a donation in November 2008 tested positive for HIV infection.9 A subsequent investigation determined that the blood donor had last donated in June 2008, at which time he incorrectly reported no HIV risk factors and his donation tested negative for the presence of HIV. One of the two recipients of blood components from this donation, an individual undergoing kidney transplantation, was found to be HIV infected, and an investigation determined that the recipient’s infection was acquired from the donor’s blood products. The CDC advises that even though such transmissions are rare, health care providers should consider the possibility of transfusion-transmitted HIV in HIV-infected transfusion recipients with no other risk factors.10

Additionally, HIV has been transmitted heterosexually from infected men with hemophilia to spouses or sexual partners in what is termed the second wave of infection and on to children born to infected couples. HIV infection in the United States is currently on the increase among women exposed via sexual intercourse with HIV-infected men. Minority women and women over the age of 50 are being affected more frequently than in prior years.11

Clinical Signs and Symptoms: Many individuals with HIV infection remain asymptomatic for years, with a mean time of approximately 10 years between exposure and development of AIDS. Systemic complaints, such as weight loss, fevers, and night sweats, are common. Cough or shortness of breath may occur with HIV-related pulmonary disease. GI complaints include changes in bowel function, especially diarrhea.

Cutaneous complaints are common and include dry skin, new rashes, and nail bed changes. Because virtually all of these findings may be seen with other diseases, a combination of complaints is more suggestive of HIV infection than any one symptom.

Many persons with AIDS experience back pain, but the underlying causes may differ. Decrease in muscle mass with subsequent postural changes may occur as a result of the disease process or in response to medications. It is not uncommon for pain to develop in the back or another musculoskeletal location where there may have been a previous injury. This is more likely to occur when the T-cell count drops.

Bone disorders such as osteopenia, osteoporosis, and osteonecrosis have been reported in association with HIV, but the etiology and mechanism of these disorders are unknown. Prevalence reported varies from study to study; scientists are researching the influence of antiretroviral therapy and lipodystrophy (absence or presence), severity of HIV disease, and overlapping risk factors for bone loss (e.g., smoking and alcohol intake). The therapist should conduct a risk factor assessment for bone loss in anyone with known HIV and educate clients about prevention strategies.12

Any woman at risk for AIDS should be aware of the possibility that recurrent or stubborn cases of vaginal candidiasis may be an early sign of infection with HIV. Pregnancy, diabetes, oral contraceptives, and antibiotics are more commonly linked to these fungal infections.

Side Effects of Medication: The therapist should review the potential side effects from medication used in the treatment of AIDS. Delayed toxicity with long-term treatment for HIV-1 infection with antiretroviral therapy occurs in a substantial number of affected individuals.13-15 The more commonly occurring symptoms include rash, nausea, headaches, dizziness, muscle pain, weakness, fatigue, and insomnia. Hepatotoxicity is a common complication; the therapist should be alert for carpal tunnel syndrome, liver palms, asterixis, and other signs of liver impairment (see Chapter 9).

Body fat redistribution to the abdomen, upper body, and breasts occurs as part of a condition called lipodystrophy associated with antiretroviral therapy. Other metabolic abnormalities, such as dysregulation of glucose metabolism (e.g., insulin resistance, diabetes), combined with lipodystrophy are labeled lipodystrophic syndrome (LDS). LDS contributes to problems with body image and increases the risk for cardiovascular complications.16-19

AIDS and Other Diseases

AIDS is a unique disease—no other known infectious disease causes its damage through a direct attack on the human immune system. Because the immune system is the final mediator of human host–infectious agent interactions, it was anticipated early that HIV infection would complicate the course of other serious human diseases.

This has proved to be the case, particularly for TB and certain sexually transmitted infections such as syphilis and the genital herpes virus. Cancer has been linked with AIDS since 1981; this link was discovered with the increased appearance of a highly unusual malignancy, Kaposi’s sarcoma. Since then, HIV infection has been associated with other malignancies, including non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma (NHL), AIDS-related primary central nervous system lymphoma, and hepatocellular carcinoma.20-22

Kaposi’s Sarcoma: Classic Kaposi’s sarcoma (KS) was first recognized as a malignant tumor of the inner walls of the heart, veins, and arteries in 1873 in Vienna, Austria. Before the AIDS epidemic, KS was a rare tumor that primarily affected older people of Mediterranean and Jewish origin.

Clinically, KS in HIV-infected immunodeficient persons occurs more often as purplish-red lesions of the feet, trunk, and head (Fig. 12-2). The lesion is not painful or contagious. It can be flat or raised and over time frequently progresses to a nodule. The mouth and many internal organs (especially those of the GI and respiratory tracts) may be involved either symptomatically or subclinically.

Fig. 12-2 AIDS-related Kaposi’s sarcoma. The early lesions appear most commonly on the toes or soles as reddish or bluish-black macules and patches that spread and coalesce to form nodules or plaques. Lesions can appear anywhere on the body including the tongue and genitals. (From James WD: Andrews’ diseases of the skin: clinical dermatology, ed 10, Philadelphia, 2006, WB Saunders.)

Prognosis depends on the status of the individual’s immune system. People who die of AIDS usually succumb to opportunistic infections rather than to KS.

Non-Hodgkin’s Lymphoma: Approximately 3% of AIDS diagnoses in all risk groups and in all areas originate through discovery of NHL. The incidence of NHL increases with age and as the immune system weakens.

These malignancies are difficult to treat because clients often cannot tolerate the further immunosuppression that treatment causes. As with KS, prognosis depends largely on the initial level of immunity. Clients with adequate immune reserves may tolerate therapy and respond reasonably well. However, in people with severe immunodeficiency, survival is only 4 to 7 months on average. Clients diagnosed with HIV-related brain lymphomas have a very poor prognosis.

Tuberculosis: Tuberculosis (TB) was considered a stable, endemic health problem, but now, in association with the HIV/AIDS pandemic, TB is resurgent.23 The recent emergence of multiple-drug–resistant TB, which has reached epidemic proportions in New York City, has created a serious and growing threat to the capacity of TB control programs (see Chapter 7).

In urban areas of the United States, the present upsurge in TB cases is occurring among young (aged 25 to 44 years) IDUs, ethnic minorities, prisoners and prison staff (because of poorly ventilated and overcrowded prison systems), homeless people, and immigrants from countries with a high prevalence of TB.

The first major interaction between HIV and TB occurs as a result of the weakening of the immune system in association with progressive HIV infection. The great majority of individuals exposed to TB are infected but not clinically ill. Their subclinical TB infection is kept in check by an active, healthy immune system. However, when a TB-infected person becomes infected with HIV, the immune system begins to decline, and at a certain level of immune damage from HIV, the TB bacteria become active, causing clinical pulmonary TB.

TB is the only opportunistic infection associated with AIDS/HIV that is directly transmissible to household and other contacts. Therefore each individual case of active TB is a threat to community health.

Clinical Signs and Symptoms: Pulmonary TB is the most common manifestation of TB disease in HIV-positive clients. When TB precedes the diagnosis of AIDS, disease is usually confined to the lung, whereas when TB is diagnosed after the onset of AIDS, the majority of clients also have extrapulmonary TB, most commonly involving the bone marrow or lymph nodes. Fever, night sweats, wasting, cough, and dyspnea occur in the majority of clients (see further discussion of TB in Chapter 7).

HIV Neurologic Disease: HIV neurologic disease may be the presenting symptom of HIV infection and can involve the central and peripheral nervous systems. HIV is a neurotropic virus and can affect neurologic tissues from the initial stages of infection. In the early course of the infection, the virus can cause demyelination of central and peripheral nervous system tissues.24 Signs and symptoms range from mild sensory polyneuropathy to seizures, hemiparesis, paraplegia, and dementia.

Central Nervous System: Central nervous system (CNS) disease in HIV-infected clients can be divided into intracerebral space–occupying lesions, encephalopathy, meningitis, and spinal cord processes. Toxoplasmosis is the most common space–occupying lesion in HIV-infected clients. Presenting symptoms may include headache, focal neurologic deficits, seizures, or altered mental status.

AIDS dementia complex (HIV encephalopathy) is the most common neurologic complication and the most common cause of mental status changes in HIV-infected clients. It is characterized by cognitive, motor, and behavioral dysfunction. This disorder is similar to Alzheimer’s dementia but has less impact on memory loss and a greater effect on time-related skills (i.e., psychomotor skills learned over time such as playing piano or reading).

Early symptoms of AIDS dementia involve difficulty with concentration and memory, personality changes, irritability, and apathy. Depression and withdrawal occur as the dementia progresses. Motor dysfunction may accompany cognitive changes and may result in poor balance, poor coordination, and frequent falls.

Progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy (PML), which produces localized lesions within the brain, causes demyelination in the brain and leads to death within a few months.

In addition to the brain, neurologic disorders related to AIDS and HIV may affect the spinal cord, appearing as myelopathies. A vacuolar myelopathy often appears in the thoracic spine and causes gradual weakness, painless gait disturbance characterized by spasticity, and ataxia in the lower extremities that progresses to include weakness of the upper extremities.

Structural and inflammatory abnormalities in the muscles of people with HIV have been reported to impair the muscle’s ability to extract or utilize oxygen during exercise. Clinical manifestations of HIV-associated myopathies include proximal weakness, myalgia, abnormal electromyogram (EMG) activity, elevated creatine kinase, and decreased functioning of the muscle.25

Peripheral Nervous System: Peripheral nerve disease is a common complication of the HIV infection. Peripheral nervous system syndromes include inflammatory polyneuropathies, sensory neuropathies, and mononeuropathies. An inflammatory demyelinating polyneuropathy similar to Guillain-Barré syndrome can occur in HIV-infected clients. Cytomegalovirus (CMV), a highly host-specific herpes virus that infects the nerve roots, may result in an ascending polyradiculopathy characterized by lower extremity weakness progressing to flaccid paralysis.

The most common neuropathy develops into painful sensory neuropathy with numbness and burning or tingling in the feet, legs, or hands. Immobility caused by painful neuropathies can result in deconditioning and eventual cardiopulmonary decline.

Hypersensitivity Disorders

Although the immune system protects the body from harmful invaders, an overactive or overzealous response is detrimental. When the immune system becomes overactive or hyperactive, a state of hypersensitivity exists, leading to immunologic diseases such as allergies.

Although the word allergy is widely used, the term hypersensitivity is more appropriate. Hypersensitivity designates an increased immune response to the presence of an antigen (referred to as an allergen) that results in tissue destruction.

The two general categories of hypersensitivity reaction are immediate and delayed. These designations are based on the rapidity of the immune response. In addition to these two categories, hypersensitivity reactions are divided into four main types (I to IV).

Type I Anaphylactic Hypersensitivity (“Allergies”)

Allergy and Atopy: Allergy refers to the abnormal hypersensitivity that takes place when a foreign substance (allergen) is introduced into the body of a person likely to have allergies. The body fights these invaders by producing the special antibody immunoglobulin E (IgE). This antibody (now a vital diagnostic sign of many allergies), when released into the blood, breaks down mast cells, which contain chemical mediators, such as histamine, that cause dilation of blood vessels and the characteristic symptoms of allergy.

Atopy differs from allergy because it refers to a genetic predisposition to produce large quantities of IgE, causing this state of clinical hypersensitivity. The reaction between the allergen and the susceptible person (i.e., allergy-prone host) results in the development of a number of typical signs and symptoms usually involving the GI tract, respiratory tract, or skin.

Clinical Signs and Symptoms: Clinical signs and symptoms vary from one client to another according to the allergies present. With the Family/Personal History form used, each client should be asked what known allergies are present and what the specific reaction to the allergen would be for that particular person. The therapist can then be alert to any of these warning signs during treatment and can take necessary measures, whether that means grading exercise to the client’s tolerance, controlling the room temperature, or appropriately using medications prescribed.

Anaphylaxis: Anaphylaxis, the most dramatic and devastating form of type I hypersensitivity, is the systemic manifestation of immediate hypersensitivity. The implicated antigen is often introduced parenterally such as by injection of penicillin or a bee sting. The activation and breakdown of mast cells systematically cause vasodilation and increased capillary permeability, which promote fluid loss into the interstitial space, resulting in the clinical picture of bronchospasms, urticaria (wheals or hives), and anaphylactic shock.

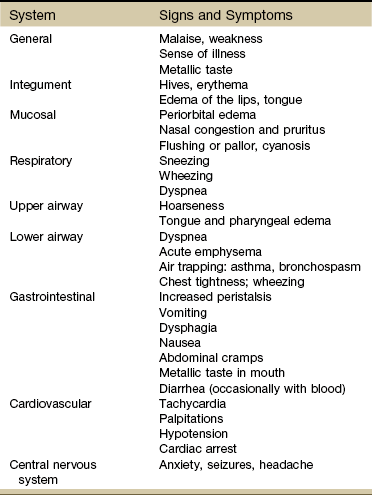

Initial manifestations of anaphylaxis may include local itching, edema, and sneezing. These seemingly innocuous problems are followed in minutes by wheezing, dyspnea, cyanosis, and circulatory shock. Clinical signs and symptoms of anaphylaxis are listed by system in Table 12-1.

TABLE 12-1

Clinical Aspects of Anaphylaxis by System

Modified from Adkinson NF: Middleton’s allergy: principles and practice, ed 7, St. Louis, 2008, Mosby.

Clients with previous anaphylactic reactions (and the specific signs and symptoms of that individual’s reaction) should be identified by using the Family/Personal History form. Identification information should be worn at all times by individuals who have had previous anaphylactic reactions. For identified and unidentified clients, immediate action is required when the person has a severe reaction. In such situations, the therapist is advised to call for emergency assistance.

Type II Hypersensitivity (Cytolytic or Cytotoxic)

A type II hypersensitivity reaction is caused by the production of autoantibodies against self cells or tissues that have some form of foreign protein attached to them. The autoantibody binds to the altered self cell, and the complex is destroyed by the immune system. Typical examples of this type of hypersensitivity are hemolytic anemias, idiopathic thrombocytopenic purpura (ITP), hemolytic disease of the newborn, and transfusion of incompatible blood. Blood group incompatibility causes cell lysis, which results in a hemolytic transfusion reaction. The antigen responsible for initiating the reaction is a part of the donor red blood cell (RBC) membrane.

Manifestations of a transfusion reaction result from intravascular hemolysis of RBCs.

Type III Hypersensitivity (Immune Complex)

Immune complex disease results from formation or deposition of antigen-antibody complexes in tissues. For example, the antigen-antibody complexes may form in the joint space, with resultant synovitis, as in RA. Antigen-antibody complexes are formed in the bloodstream and become trapped in capillaries or are deposited in vessel walls, affecting the skin (urticaria), the kidneys (nephritis), the pleura (pleuritis), and the pericardium (pericarditis).

Serum sickness is another type III hypersensitivity response that develops 6 to 14 days after injection with foreign serum (e.g., penicillin, sulfonamides, streptomycin, thiouracils, hydantoin compounds). Deposition of complexes on vessel walls causes complement activation with resultant edema, fever, inflammation of blood vessels and joints, and urticaria.

Type IV Hypersensitivity (Cell-Mediated or Delayed)

In cell-mediated hypersensitivity, a reaction occurs 24 to 72 hours after exposure to an allergen.

For example, type IV reactions occur after the intradermal injections of TB antigen. Graft-versus-host disease (GVHD) and transplant rejection are also type IV reactions. In GVHD, immunocompetent donor bone marrow cells (the graft) react against various antigens in the bone marrow recipient (the host), which results in a variety of clinical manifestations, including skin, GI, and hepatic lesions.

Contact dermatitis is another type IV reaction that occurs after sensitization to an allergen, commonly a cosmetic, adhesive, topical medication, drug additive (e.g., lanolin added to lotions, ultrasound gels, or other preparations used in massage or soft tissue mobilization), or plant toxin (e.g., poison ivy).

With the first exposure, no reaction occurs; however, antigens are formed. On subsequent exposures, hypersensitivity reactions are triggered, which leads to itching, erythema, and vesicular lesions. Anyone with known hypersensitivity (identified through the Family/Personal History form) should have a small area of skin tested before use of large amounts of topical agents in the physical therapy clinic. Careful observation throughout the episode of care is required.

Autoimmune Disorders

Autoimmune disorders occur when the immune system fails to distinguish self from nonself and misdirects the immune response against the body’s own tissues. The body begins to manufacture antibodies called autoantibodies directed against the body’s own cellular components or specific organs. The resultant abnormal tissue reaction and tissue damage may cause systemic manifestations varying from minimal localized symptoms to systemic multiorgan involvement with severe impairment of function and life-threatening organ failure.

The exact cause of autoimmune diseases is not understood, but factors implicated in the development of autoimmune immunologic abnormalities may include genetics (familial tendency), sex hormones (women are affected more often than men by autoimmune diseases), viruses, stress, cross-reactive antibodies, altered antigens, or the environment.

Autoimmune disorders may be classified as organ-specific diseases or generalized (systemic) diseases. Organ-specific diseases involve autoimmune reactions limited to one organ. Organ-specific autoimmune diseases include thyroiditis, Addison’s disease, Graves’ disease, chronic active hepatitis, pernicious anemia, ulcerative colitis, and insulin-dependent diabetes. These diseases have been discussed in this text (see the chapter appropriate to the organ involved) and are not covered further in this chapter.

Generalized autoimmune diseases involve reactions in various body organs and tissues (e.g., fibromyalgia, RA, SLE, and scleroderma). Systemic autoimmune diseases lead to a sequence of abnormal tissue reaction and damage to tissue that may result in diffuse systemic manifestations.

Fibromyalgia Syndrome

Fibromyalgia syndrome (FMS) is a noninflammatory condition appearing with generalized musculoskeletal pain in conjunction with tenderness to touch in a large number of specific areas of the body and a wide array of associated symptoms. FMS is much more common in women than in men; it is 2 to 5 times more common than RA. It occurs in age groups from preadolescents to early postmenopausal women.26 The condition is less common in older adults.

There is still much controversy over the exact nature of FMS and even debate over whether fibromyalgia is an organic disease with abnormal biochemical or immunologic pathologic aspects. Some theories suggest that it is a genetically predisposed condition with dysregulation of the neurohormonal and autonomic nervous systems.27 It may be triggered by viral infection, a traumatic event, or stress. The role of inadequate thyroid hormone regulation as a main mechanism of fibromyalgia has been proposed and is under investigation.28

More recent research suggests that chronic pain of this type is centrally mediated since most of these individuals experience pain with input or stimuli that are not usually painful. The problem is with pain or sensory processing, rather than some disease, inflammation, or impairment of the area that actually hurts (e.g., the back, the hips, the wrists).

Functional brain imaging shows areas of the brain that light up when pressure is applied to painful areas of the body. All indications are that once the central pain mechanisms get turned on, they “wind up” until there is pain even when the stimulus (e.g., pressure, heat, cold, electrical impulses) is no longer there. This phenomenon is called sensory augmentation. There is some evidence that people with fibromyalgia have a decrease in their reactivity threshold. In other words, with a low threshold, it only takes a small amount of stimuli before the pain switch gets turned on. Exactly why this happens remains unknown.27

Controversy also existed regarding use of the American College of Rheumatism (ACR) criteria for tender point count in clinical diagnosis of FMS.29 In fact, the original author of the ACR criteria suggested that counting the tender points was “perhaps a mistake” and advised against using it in clinical practice.30 A Symptom Intensity Scale was subsequently developed and validated by Wolfe31,32 to help differentiate FMS from other rheumatologic conditions (e.g., SLE or polymyalgia rheumatica) with similar widespread pain.

Since that time, Wolfe and associates proposed a new set of diagnostic criteria, which the ACR has adopted.33 The new tool focuses on measuring symptom severity rather than relying on the tender point examination. The new criteria use a clinician-queried checklist of painful sites and a symptom severity scale that focuses on fatigue, cognitive dysfunction, and sleep disturbance. Tender point assessment still has value; people with fewer than 11 of the 18 tender points included in the ACR classification criteria may still be diagnosed with fibromyalgia if they have other clinical features consistent with fibromyalgia.34

Fibromyalgia has been differentiated from myofascial pain in that FMS is considered a systemic problem with multiple tender points as one of the key symptoms; there is usually a cluster of associated signs and symptoms. Myofascial pain is a localized condition specific to a muscle (trigger point [TrP]) and may involve as few as one or several areas without associated signs and symptoms.

The hallmark of myofascial pain syndrome is the TrP, as opposed to tender points in FMS. Both disorders cause myalgia with aching pain and tenderness and exhibit similar local histologic changes in the muscle. Painful symptoms in both conditions are increased with activity, although fibromyalgia involves more generalized aching, whereas myofascial pain is more direct and localized (Table 12-2).

TABLE 12-2

Differentiating Myofascial Pain Syndrome from Fibromyalgia Syndrome

| Myofascial Pain Syndrome | Fibromyalgia Syndrome |

| Trigger points (pain with deep pressure); often radiates locally | Tender points (pain with light touch); no radiation |

| Localized musculoskeletal condition | Systemic condition |

| Palpable taut band found in muscle; no associated signs and symptoms | No palpable or visible local abnormality; wide array of associated signs and symptoms |

| Etiology: Overuse, repetitive motions; reduced muscle activity (e.g., casting or prolonged splinting); hormones containing progestins (under investigation)35 | Etiology: Neurohormonal imbalance; autonomic nervous system dysfunction |

| Risk factors: Immobilization, repetitive use | Risk factors: Trauma, psychosocial stress, mood (or other psychologic) disorders; other medical conditions |

| Pathophysiology: Unknown, possibly muscle spindle dysfunction | Pathophysiology: Sensitization of spinal neurons from excitatory nerve messenger substances |

| Prognosis: Excellent | Prognosis: Good with early diagnosis and intervention, variable with delayed diagnosis; often a chronic condition |

Data from Lowe JC, Yellin JG: The metabolic treatment of fibromyalgia, Utica, Kentucky, 2000, McDowell Publications.

There is some clinical evidence that myofascial pain syndrome is linked with the use of hormones containing synthetic progestin (e.g., birth control pills). The effects of progestin on women with fibromyalgia is unknown.35

FMS has striking similarities to chronic fatigue syndrome (CFS), with a mix of overlapping symptoms (about 70%) that have some common biologic denominator. Diagnostic criteria for CFS focus on fatigue, whereas the criteria for FMS focus on pain, the two most prominent symptoms of these syndromes. Studies have shown that CFS and FMS are characterized by greater similarities than differences and both involve the central and peripheral nervous systems as well as the body tissues themselves (Box 12-2).36

Risk Factors: Numerous studies have implicated a genetic predisposition related to brain and/or body chemistry, but it has also been shown that a history of childhood trauma, family issues, and/or physical/sexual abuse are significant risk factors.37 Stress, illness, disease, or anything the body perceives as a threat are risk factors for those who develop FMS. But why one person develops this condition, whereas others with equal or worse situations do not, remains a mystery. Anxiety, depression, and posttraumatic stress disorder also seem to be linked with FMS.38 Having a bipolar illness increases the risk of developing FMS dramatically.39

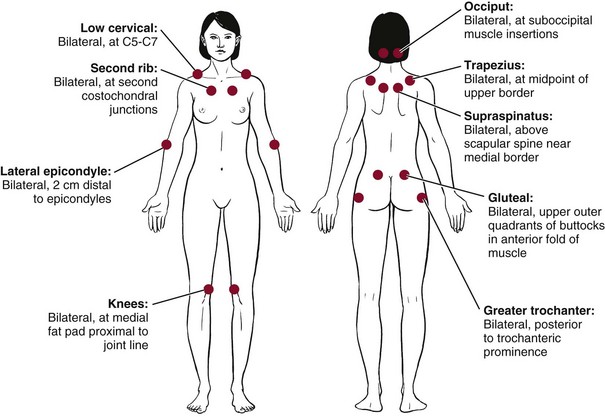

Clinical Signs and Symptoms: The core features of FMS include widespread pain lasting more than 3 months and widespread local tenderness in all clients (Fig. 12-3). Primary musculoskeletal symptoms most frequently reported are (1) aches and pains, (2) stiffness, (3) swelling in soft tissue, (4) tender points, and (5) muscle spasms or nodules. Fatigue, morning stiffness, and sleep disturbance with nonrefreshed awakening may be present but are not necessary for the diagnosis.40

Fig. 12-3 Anatomic locations of tender points associated with fibromyalgia. According to the literature, digital palpation should be performed with an approximate force of 4 kg (enough pressure to indent a tennis ball), but clinical practice suggests much less pressure is required to elicit a painful response. For a tender point to be considered positive, the subject must state that the palpation was “painful.” A reply of “tender” is not considered a positive response. As mentioned in the text, counting the number of points as part of the clinical diagnosis of fibromyalgia syndrome (FMS) has been discounted; however, the presence of multiple tender points is still a key feature of FMS.

Nontender control points (such as midforehead and anterior thigh) have been included in the examination by some clinicians. These control points may be useful in distinguishing FMS from a conversion reaction, referred to as psychogenic rheumatism, in which tenderness may be present everywhere. However, evidence suggests that individuals with FMS may have a generalized lowered threshold for pain on palpation and the control points may also be tender on occasion. There is also an increased sensitivity to sensory stimulation such as pressure stimuli, heat, noise, odors, and bright lights.41

Symptoms are aggravated by cold, stress, excessive or no exercise, and physical activity (“overdoing it”), including overstretching, and may be improved by warmth or heat, rest, and exercise, including gentle stretching. Smoking has been linked with increased pain intensity and more severe fibromyalgia symptoms, but not necessarily a higher number of tender points. Exposure to tobacco products may be a risk factor for the development of fibromyalgia, but this has not been investigated fully or proven.42

Sleep disturbances in stage 4 of nonrapid eye movement sleep (needed for healing of muscle tissues), sleep apnea, difficulty getting to sleep or staying asleep, nocturnal myoclonus (involuntary arm and leg jerks), and bruxism (teeth grinding) cause clients with FMS to wake up, feeling unrested or unrefreshed, as if they had never gone to sleep (Box 12-3).

Researchers are beginning to identify various subtypes of fibromyalgia and recognize the need for specific intervention based on the underlying subtype. These classifications are based on impairment of the autonomic nervous system. They include the following35,43:

A multidisciplinary or interdisciplinary team approach to this condition requires medical evaluation and treatment as part of the intervention strategy for fibromyalgia. Therapists should refer clients suspected of having fibromyalgia for further medical follow-up.

Rheumatoid Arthritis

Rheumatoid arthritis (RA) is a chronic, systemic, inflammatory disorder of unknown cause that can affect various organs but predominantly involves the synovial tissues of the diarthrodial joints. There are more than 100 rheumatic diseases affecting joints, muscles, and extraarticular systems of the body.

Women are affected with RA 2 to 3 times more often than men; however, women who are taking or have taken oral contraceptives are less likely to develop RA. Although it may occur at any age, RA is most common in persons between the ages of 20 and 40 years.

Risk Factors: The etiologic factor or trigger for this process is as yet unknown. Support for a genetic predisposition comes from studies suggesting that RA clusters in families. One gene in particular (HLA-DRB1 on chromosome 6) has been identified in determining susceptibility. RA may be caused by a genetically susceptible person encountering an unidentified agent (e.g., virus, self-antigen), which then results in an immunopathologic response.44 Researchers hypothesize that an infection could trigger an immune reaction that is mediated through multiple complex genetic mechanisms and continues clinically even if the organism is eradicated from the body.

Other nongenetic factors may also contribute to the development of RA. Because arthritis (and many related diseases) is more common in women, hormones have been implicated, but the relationship remains unclear. Environmental and occupational causes, such as chemicals (e.g., hair dyes, industrial pollutants), minerals, mineral oil, organic solvents, silica, toxins, medications, food allergies, cigarette smoking, and stress, remain under investigation as possible triggers for those individuals who are genetically susceptible to RA.45 Many systemic disorders can express themselves through the musculoskeletal system often presenting first with rheumatic manifestations (Box 12-4).46

Clinical Signs and Symptoms: Clinical features of RA vary not only from person to person but also in an individual over the disease course. In most people, the symptoms begin gradually during a period of weeks or months. Frequently, malaise and fatigue prevail during this period, sometimes accompanied by diffuse musculoskeletal pain. The multidimensional aspects of rheumatoid arthritic pain can be assessed quantitatively using the Rheumatoid Arthritis Pain Scale (RAPS).47 The complete RAPS is available in the appendix of this article.

Symptoms of an inflammatory arthritis include the spontaneous onset of one or more swollen joints; morning stiffness lasting longer than 45 minutes; and diffuse joint pain and tenderness, particularly involving the metatarsophalangeal (MTP) or metacarpophalangeal (MCP) joints. Inactivity, such as sleep or prolonged sitting, is commonly followed by stiffness. “Morning” stiffness occurs when the person arises in the morning or after prolonged inactivity. The duration of this stiffness is an accepted measure of the severity of the condition.

Clients should be asked: “After you get up in the morning, how long does it take until you are feeling the best you will feel for the day?” Pain and stiffness increase gradually as RA progresses and may limit a person’s ability to walk, climb stairs, open doors, or perform other activities of daily living (ADLs). Weight loss, depression, and low-grade fever can accompany this process.

The inflammatory process may be under way for some time before swelling, tissue reaction, and joint destruction are seen. Structural damage usually begins between the first and second year of the disease. Early medical referral, followed by expedited diagnosis and intervention, results in a much more favorable outcome for persons with RA.

Studies have shown that 70% to 90% of persons with RA have significant joint erosions on x-ray by only 2 years after disease onset and that halting or slowing erosions should be initiated very early on in the course of the disease.48 Having awareness of the group of symptoms that suggest inflammatory arthritis is critical. It is recommended that the criteria for referral of a person with early inflammatory symptoms include significant discomfort on the compression of the metacarpal and metatarsal joints, the presence of three or more swollen joints, and more than 1 hour of morning stiffness.49

Shoulder: Chronic synovitis of the elbows, shoulders, hips, knees, and/or ankles creates special secondary disorders. When the shoulder is involved, limitation of shoulder mobility, dislocation, and spontaneous tears of the rotator cuff result in chronic pain and adhesive capsulitis.

Elbow: Destruction of the elbow articulations can lead to flexion contracture, loss of supination and pronation, and subluxation. Compressive ulnar nerve neuropathies may develop related to elbow synovitis. Symptoms include paresthesias of the fourth and fifth fingers and weakness in the flexor muscle of the little finger.

Wrists: The joints of the wrist are frequently affected in RA, with variable tenosynovitis of the dorsa of the wrists and, ultimately, interosseous muscle atrophy and diminished movement owing to articular destruction or bony ankylosis. Volar synovitis can lead to carpal tunnel syndrome.

Hands and Feet: Forefoot pain may be the only small-joint complaint and is often the first one. Subluxation of the heads of the MTP joints and shortening of the extensor tendons give rise to “hammer toe” or “cock up” deformities. A similar process in the hands results in volar subluxation of the MCP joints and ulnar deviation of the fingers. An exaggerated inflammatory response of an extensor tendon can result in a spontaneous, often asymptomatic rupture. Hyperextension of a proximal interphalangeal (PIP) joint and flexion of the distal interphalangeal (DIP) joint produce a swan neck deformity. The boutonnière deformity is a fixed flexion contracture of a PIP joint and extension of a DIP joint.

Cervical Spine: Involvement of the cervical spine by RA tends to occur late in more advanced disease. Clinical manifestations of early disease consist primarily of neck stiffness that is perceived through the entire arc of motion. Inflammation of the supporting ligaments of C1-C2 eventually produces laxity, sometimes giving rise to atlantoaxial subluxation. Spinal cord compression can result from anterior dislocation of C1 or from vertical subluxation of the odontoid process of C2 into the foramen magnum.

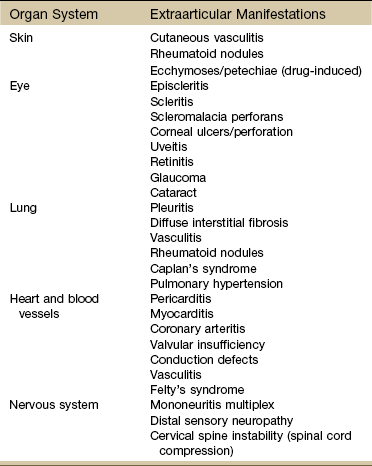

Extraarticular: Extraarticular features, such as rheumatoid nodules, arteritis, neuropathy, scleritis, pericarditis, lymphadenopathy, and splenomegaly, occur with considerable frequency (Table 12-3). Once thought to be complications of RA, they are now recognized as being integral parts of the disease and serve to emphasize its systemic nature.

TABLE 12-3

Extraarticular Manifestations of Rheumatoid Arthritis

Modified from Andreoli TE, Benjamin I, Griggs RC, et al: Andreoli and Carpenter’s Cecil essentials of medicine, ed 8, Philadelphia, 2010, Saunders.

The subcutaneous nodules, present in approximately 25% to 35% of clients with RA, occur most commonly in subcutaneous or deeper connective tissues in areas subjected to repeated mechanical pressure such as the olecranon bursae, the extensor surfaces of the forearms, the elbow, and the Achilles tendons.

Age-Related Differences: One-third of persons with RA acquire the disease after the age of 60 years. There are differences in presentation of the disease in older versus younger people. Onset in younger people is usually in 30- to 50-year-olds, with a 2 : 1 ratio of women to men; polyarticular, involving small joints; and gradual in onset with a positive RF. In the elderly population (age 60 years or older), joint involvement may be oligoarticular, involving large joints, and more abrupt in onset, with an equal ratio of women to men and a negative RF finding.50

Juvenile Idiopathic Arthritis: Juvenile idiopathic arthritis (JIA) replaces the term juvenile rheumatoid arthritis (JRA). JIA is a chronic inflammatory disorder that occurs during childhood and is made up of a heterogeneous group of diseases that share synovitis as a common feature. JIA has seven subcategories:

Early recognition of JIA is key to timely initiation of treatment. For a diagnosis of JIA to be made, objective arthritis must be seen in one or more joints for at least 6 weeks in children younger than 16 years. Children should be screened for an array of symptoms, depending on the appropriate subcategory of disease. The number of joints involved, involvement of small joints, symmetry of joint involvement, uveitis risk, systemic features, and family history are important parts of this screening. It is important to educate parents regarding symptoms because parents are the first line of communication from their children to health care professionals.51

Diagnosis: The clinical diagnosis of RA is based on careful consideration of three factors: the clinical presentation of the client, which is elucidated through history taking and physical examination; the corroborating evidence gathered through laboratory tests and radiography; and the exclusion of other possible diagnoses.

The physical presence of rheumatoid nodules and the presence of RF measured by laboratory studies are two indicators of RA, although some persons with actual RFs are missed by commonly available methods.

Classification of RA (Table 12-4) is difficult in the early course of the disease, when articular symptoms are accompanied only by constitutional symptoms such as fatigue and loss of appetite, which are common to a number of chronic diseases. A full array of clinical signs and symptoms may not be manifest for 1 to 2 years. A diagnosis of RA is established on the presentation of 4 of the 7 listed criteria with duration of joint signs and symptoms for at least 6 weeks.

TABLE 12-4

American Rheumatism Association Criteria for Classification of Rheumatoid Arthritis*

| Criteria | Definition |

| Morning stiffness | Morning stiffness in and around the joints lasting at least 1 hour |

| Arthritis of three or more joint areas | Simultaneous soft tissue swelling or fluid (not bony overgrowth alone) observed by a physician; the 14 possible joint areas are (right or left): PIP, MCP, wrist, elbow, knee, ankle, and MTP joints |

| Arthritis of hand joints | At least one joint area swollen as above in wrist, MCP, or PIP joint |

| Symmetric arthritis | Simultaneous bilateral involvement of the same joint areas as above (PIP, MCP, or MTP joints without absolute symmetry is acceptable) |

| Rheumatoid nodules | Subcutaneous nodules, over bony prominences or extensor surfaces |

| Serum rheumatoid factor | Abnormal amounts of serum rheumatoid factor |

| Radiographic changes | Radiographic changes typical of rheumatoid arthritis on posteroanterior hand and wrist radiographs, which must include erosions or bony decalcification localized to involved joints (osteoarthritis changes alone do not qualify) |

MCP, Metacarpophalangeal; MTP, metatarsophalangeal; PIP, proximal interphalangeal.

*For classification purposes, a client is said to have rheumatoid arthritis (RA) if he or she has satisfied at least four of the above seven criteria. Criteria 1 through 4 must be present for at least 6 weeks. Clients with two clinical diagnoses are not excluded. Designation as classic, definite, or probable RA is no longer made.

Modified from Harris ED, Jr: Clinical features of rheumatoid arthritis. In Kelley WN, et al: Textbook of rheumatology, ed 4, Philadelphia, 1993, Saunders, p 874.

Additional laboratory tests of significance in the diagnosis and management of RA include white blood cell (WBC) count, erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR), hemoglobin and hematocrit, urinalysis, and RF assay. The elevation of C-reactive protein (CRP) has been discovered in significant levels within 2 years preceding a confirmed diagnosis of RA. The increased levels of CRP signal the kind of steady, low-grade inflammation that may be an early predictor of later symptomatic inflammation.52 CRP as a predictive factor remains a topic of debate and under continued investigation.

The number of WBCs will increase in the presence of joint inflammation, as will the erythrocyte sedimentation rate. Anemia may be present, and the RF will be elevated in clients with active RA. If the client’s urinalysis reveals any protein, blood cells, or casts, SLE should be suspected. This type of abnormal urinalysis would necessitate further diagnostic evaluation and immediate physician referral (Case Example 12-1).

Treatment: Aggressive treatment of early arthritis with new medications has shown marked improvement in outcome.53 These medications have both immunosuppressive and biologic side effects that must be monitored. The emergence of therapeutic biologic agents, such as anti-tumor necrosis factor (TNF) and biologic response modifiers called disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs (DMARDs), has led to suppression of symptoms of RA and slowed disease progression. Side effects and safety concerns are critical in the prevention of serious side effect–related problems, including the following:

• Congestive heart failure (CHF)

• Serious infections due to immunosuppression (e.g., TB, Listeria monocytogenes, coccidioidomycosis, histoplasmosis, viral hepatitis)

• Skin reactions (erythema, pruritus, rashes, urticaria, infection, eczema)54

• New onset symptoms of MS, optic neuritis, and transverse myelitis

• Hematologic abnormalities such as aplastic anemia, pancytopenia

Screening should include a thorough epidemiologic history regarding previous exposure to TB.55

Polymyalgia Rheumatica

Polymyalgia rheumatica (PMR) is a systemic rheumatic inflammatory disorder with an unknown cause; there may be an autoimmune, viral, or stress-induced mechanism.

Risk Factors: PMR occurs almost exclusively in people over 55 years of age. The disease rarely occurs in persons under the age of 50, and it affects twice as many women as men. It is at least 10 times more prevalent in persons over 80 than in persons between the ages of 50 and 59, and it predominantly affects the Caucasian population.56,57

Clinical Presentation: PMR is characterized by severe aching and stiffness primarily in the muscles, as opposed to the joints. Onset is usually very sudden and insidious. Areas commonly affected include the neck, shoulder girdle, and pelvic girdle. Joint pain is possible, and headache, weakness, and fatigue are commonly reported. The pain is usually more severe when the person gets up in the morning.

PMR is closely linked with giant cell or temporal arteritis. Giant cell arteritis (GCA) primarily affects the medium-sized muscular arteries, such as the cranial and extracranial branches of the carotid artery that pass over the temples in the scalp.58 The temporal arteries become inflamed, subjecting them to damage. In GCA, the most common symptom is a severe headache on one or both sides of the head.

Orofacial symptoms of pain, jaw claudication, hard end-feel limitation of jaw range of motion, and temporal headache can be misdiagnosed as a temporomandibular joint (TMJ) disorder.59 A careful evaluation by the physical therapist can often pinpoint enough differences to recognize the need for referral when the clinical presentation and outcomes of treatment do not match expectations for TMJ impairment.

The ophthalmic arteries are affected in nearly half of all affected individuals, sometimes resulting in partial loss of vision or even sudden blindness. Early diagnosis of GCA is important to prevent blindness. The diagnosis of polymyalgia rheumatica is made on the basis of age, clinical presentation, and a very high ESR. The ESR measures the total inflammation in the body (Case Example 12-2).

PMR is self-limiting, typically lasting 2 to 3 years. In some cases, it goes away for reasons unknown. However, some persons may have a longer course of disease, requiring low-dose steroids for much longer; a few have PMR for less than a year. Oral corticosteroids (especially prednisone) used to suppress the inflammation, treat the symptoms, and provide remission but do not cure the illness.60,61 These drugs usually afford prompt relief of symptoms, providing further diagnostic confirmation that PMR is the underlying problem.56 The therapist must remain alert to the possibility of steroid-induced osteopenia and diabetes.

With medical intervention, most people with PMR (with or without GCA) do not have lasting disability. However, in GCA, if one or both eyes develop blindness before treatment becomes effective, the blindness may be permanent.

Systemic Lupus Erythematosus

Systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) belongs to the family of autoimmune rheumatic diseases. It is known to be a chronic, systemic, inflammatory disease characterized by injury to the skin, joints, kidneys, heart and blood-forming organs, nervous system, and mucous membranes.

Lupus comes from the Latin word for wolf, referring to the belief in the 1800s that the rash of this disease was caused by a wolf bite. The characteristic rash of lupus (especially a butterfly rash across the cheeks and nose) is red, leading to the term erythematosus.

There are two primary forms of lupus: discoid and systemic. Discoid lupus is a limited form of the disease confined to the skin presenting as coin-shaped lesions, which are raised and scaly (see Fig. 4-17). Discoid lupus rarely develops into systemic lupus. Individuals who develop the systemic form probably had systemic lupus at the outset, with the discoid lesions as the main symptom.

Systemic lupus is usually more severe than discoid lupus and can affect almost any organ or system of the body. For some people, only the skin and joints will be involved. In others, the joints, lungs, kidneys, blood, or other organs or tissues may be affected.62

Risk Factors: The exact cause of SLE is unknown, although it appears to result from an immunoregulatory disturbance brought about by the interplay of genetic, hormonal, chemical, and environmental factors.

Some of the environmental factors that may trigger the disease are infections (e.g., Epstein-Barr virus), antibiotics (especially those in the sulfa and penicillin groups) and other medications, exposure to ultraviolet (sun) light, and extreme physical and emotional stress, including pregnancy.

Although there is a known genetic predisposition, no known gene is associated with SLE. Lupus can occur at any age, but it is most common in persons between the ages of 15 and 40 years; it rarely occurs in older people. Women are affected 10 to 15 times more often than men, possibly because of hormones, but the exact relationship remains unknown.

SLE is more common in African-American, African-Caribbean, Hispanic-American, American-Indian, and Asian persons than in the Caucasian population.63 Other risk factors among African-American women include early tobacco use (before age 19) but not alcohol intake.64

Clinical Signs and Symptoms: There is no single characteristic clinical pattern of symptoms. Clients may differ dramatically in the relative severity and pattern of organ involvement. SLE can appear in one organ or many. Common organ involvement includes cutaneous lupus, polyarthritis, nephritis, and hematologic lupus.65 Although these symptoms may not be present at disease onset, most persons develop manifestations of multisystem disease.

Integumentary Changes: The classic butterfly rash associated with SLE often appears on the cheeks, bridge of the nose, forehead, chin, and V-area of the neck. Facial involvement is usually symmetric, and the nasolabial folds and upper eyelids are typically spared. Skin rash can also appear over the extensor surfaces of the arms, forearms, and hands/fingers. The hair may start to thin, causing an unkempt appearance referred to as lupus hair. Photosensitivity is common.62

Musculoskeletal Changes: Arthralgias and arthritis are the most common presenting manifestations of SLE. Acute migratory or persistent nonerosive arthritis may involve any joint, but typically the small joints of the hands, wrists, and knees are symmetrically involved. Lupus does not directly affect the spine, but syndromes, such as costochondritis and cervical myofascial syndrome associated with SLE, are commonly treated in a physical therapist practice.

One-fourth of all persons with lupus develop progressive musculoskeletal damage with deforming arthritis, osteoporosis with fracture and vertebral collapse, and osteomyelitis. Avascular necrosis has been detected in 6% of the adult SLE population (femoral head as the most common site of involvement).66 Often, these musculoskeletal complications occur as a result of the drugs necessary for treatment.

Approximately 30% of people with SLE have coexistent fibromyalgia, independent of race. Fibromyalgia is identified as a major contributor of pain and fatigue, but a medical differential diagnosis is required to rule out hypothyroidism, anemia, or pulmonary lupus (interstitial lung disease or pulmonary hypertension).

Peripheral Neuropathy: Peripheral neuropathy may be motor, sensory (stocking-glove distribution), or mixed motor and sensory polyneuropathy. These may develop subacutely in the lower extremities and progress to the upper extremities. Numbness on the tip of the tongue and inside the mouth is also a frequent complaint. Touch, vibration, and position sense are most prominently affected, and the distal limb reflexes are depressed (Case Example 12-3).

Neuropsychiatric Manifestations: Individuals with SLE are at increased risk of several neuropsychiatric manifestations sometimes referred to as neurolupus. Common (cumulative incidence >5%) manifestations include cerebrovascular disease (CVD) and seizures; relatively uncommon (1% to 5%) are severe cognitive dysfunction, major depression, acute confusional state (ACS), peripheral nervous disorders psychosis. Strong risk factors (at least fivefold increased risk) are previous or concurrent severe neuropsychiatric SLE (for cognitive dysfunction, seizures) and antiphospholipid antibodies (for CVD, seizures, chorea).67,68

Scleroderma (Progressive Systemic Sclerosis)

Scleroderma, one of the lesser-known chronic multisystem diseases in the family of rheumatic diseases, is characterized by inflammation and fibrosis of many parts of the body, including the skin, blood vessels, synovium, skeletal muscle, and certain internal organs such as kidneys, lungs, heart, and GI tract.

There are two major subsets: limited cutaneous (previously known as the CREST syndrome) and diffuse cutaneous scleroderma. The major differences between these two types are the degree of clinically involved skin and the pace of disease.

Limited scleroderma (also known as morphea) is often characterized by a long history of Raynaud’s phenomenon before the development of other symptoms. Skin thickening is limited to the hands, frequently with digital ulcers. Esophageal dysmotility is common. Although limited scleroderma is generally a milder form than diffuse scleroderma, life-threatening complications can occur from small intestine involvement and pulmonary hypertension.

Children affected by juvenile localized scleroderma develop multiple extracutaneous manifestations in 25% of all cases. These extracutaneous features can include joint, neurologic (e.g., epilepsy, peripheral neuropathy, headache), vascular, and ocular changes. These manifestations are often unrelated to the site of the skin lesions and can be associated with multiple organ involvement. Even so, the risk of developing systemic sclerosis (SSc) is very low.69

Diffuse scleroderma has a much more acute onset, with many constitutional symptoms, arthritis, carpal tunnel syndrome, and marked swelling of the hands and legs. Widespread skin thickening occurs, progressing from the fingers to the trunk. Internal organ problems, including GI effects and pulmonary fibrosis (see the section on systemic sclerosing lung disease in Chapter 7), are common, and severe life-threatening involvement of the heart and kidneys occurs.70-72

Risk Factors: Although the cause of scleroderma is unknown, researchers suspect a complex interaction of genetic and environmental factors. Scleroderma can occur in individuals of any age, race, or sex, but it occurs most commonly in young or middle-age women (ages 25 through 55).73

Skin: Raynaud’s phenomenon and tight skin are the hallmarks of SSc. Virtually all clients with SSc have Raynaud’s phenomenon, which is defined as episodic pallor of the digits following exposure to cold or stress associated with cyanosis, followed by erythema, tingling, and pain. Raynaud’s phenomenon primarily affects the hands and feet and less commonly the ears, nose, and tongue.

The appearance of the skin is the most distinctive feature of SSc. By definition, clients with diffuse SSc have taut skin in the more proximal parts of extremities, in addition to the thorax and abdomen. However, the skin tightening of SSc begins on the fingers and hands in nearly all cases. Therefore the distinction between limited and diffuse SSc may be difficult to make early in the illness.

Musculoskeletal: Articular complaints are very common in progressive systemic sclerosis (PSS) and may begin at any time during the course of the disease. The arthralgias, stiffness, and arthritis seen may be difficult to distinguish from those of RA, particularly in the early stages of the disease. Involved joints include the MCPs, PIPs, wrists, elbows, knees, ankles, and small joints of the feet.

Muscle involvement is usually mild, with weakness, tenderness, and pain of proximal muscles of the upper and lower extremities. Late scleroderma is characterized by muscle atrophy, muscle weakness, deconditioning, and flexion contractures.

Viscera: Skin changes, Raynaud’s phenomenon, and involvement of the GI tract are the most common manifestation of SSc. Esophageal hypomotility occurs in more than 90% of clients with either diffuse or limited SSc. Similar changes occur in the small intestine, resulting in reduced motility and causing intermittent diarrhea, bloating, cramping, malabsorption, and weight loss. Inflammation and fibrosis can also affect the lungs, resulting in interstitial lung disease, a restrictive lung disease.74,75

The overall course of scleroderma is highly variable. Once remission occurs, relapse is uncommon. The diffuse form generally has a worse prognosis because of cardiac involvement such as cardiomyopathy, pericarditis, pericardial effusions, or arrhythmias.

Spondyloarthropathy

Spondyloarthropathy represents a group of noninfectious, inflammatory, erosive rheumatic diseases that target the sacroiliac joints, the bony insertions of the annulus fibrosi of the intervertebral disks, and the facet or apophyseal joints. This group of diseases is currently being reclassified with updated criteria for two major categories: inflammatory back pain (IBP) and axial spondyloarthritis (SpA)76,77 and includes ankylosing spondylitis (AS; also known as Marie-Strümpell disease), Reiter’s syndrome, PsA, and arthritis associated with chronic IBD (see discussion in Chapter 8).

Individuals with spondyloarthropathies are not seropositive for RF, and the progressive joint fibrosis present is associated with the genetic marker human leukocyte antigen (HLA-B27). Spondyloarthropathy is more common in men, who by gender have a familial tendency toward the development of this type of disease.

Ankylosing Spondylitis: Ankylosing spondylitis (AS) is a chronic, progressive inflammatory disorder of undetermined cause. It is actually more an inflammation of fibrous tissue affecting the entheses, or insertions of ligaments, tendons, and capsules into bone, than of synovium, as is common in other rheumatic disorders.

The sacroiliac joints, spine, and large peripheral joints are primarily affected, but this is a systemic disease with widespread effects. People with AS may experience arthritis in other joints, such as the hips, knees, and shoulders, along with fever, fatigue, loss of appetite, and redness and pain of the eyes.

Although AS has always been more common in men, some studies now suggest that the disease has a more uniform sex distribution, but it may be milder in women with more peripheral joint manifestations than spinal disease.78,79

Diagnosis may be delayed or inappropriate when reliance is only on x-rays because disease progression over time is required for a confirmed diagnosis. New diagnostic criteria using magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) have helped improve rates of early diagnosis.80

Clinical Signs and Symptoms: The classic presentation of AS is insidious onset of middle and low back pain and stiffness for more than 3 months in a person (usually male) under 40 years of age. It is usually worse in the morning, lasting more than 1 hour, and is characterized as achy or sharp (“jolting”), typically localized to the pelvis, buttocks, and hips; this pain can be confused with sciatica. A neurologic examination will be within normal limits.

Paravertebral muscle spasm, aching, and stiffness are common, but some clients may have slow progressive limitation of motion with no pain at all. Most clients have sacroiliitis as the earliest feature seen on x-ray films before clinical involvement extends to the lumbar spine. A MRI examination can demonstrate acute and chronic changes of sacroiliitis, osteitis, diskovertebral lesions, disk calcifications and ossification, arthropathic (joint) lesions, and complications such as fracture and cauda equina syndrome.81

On physical examination, decreased mobility in the anteroposterior and lateral planes will be symmetric. Reduction in lumbar flexion is an early sign of AS. The Schober test is used to confirm reduction in spinal motion associated with AS.82 The sacroiliac joint is rarely tender by direct palpation. As the disease progresses, the inflamed ligaments and tendons around the vertebrae ossify (turn to bone), causing a rigid spine and the loss of lumbar lordosis. In the most severe cases, the spine becomes so completely fused that the person may be locked in a rigid upright position or in a stooped position, unable to move the neck or back in any direction.

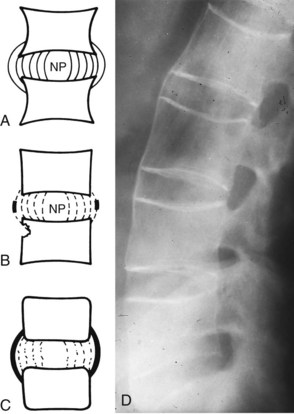

Peripheral joint involvement usually (but not always) occurs after involvement of the spine. Typical extraspinal sites include the manubriosternal joint, symphysis pubis, shoulder, and hip joints. If the ligaments that attach the ribs to the spine become ossified, diminished chest expansion (<2 cm) occurs, making it difficult to take a deep breath. Chest wall stiffness seldom leads to respiratory disability as long as diaphragmatic movement is intact. This process of vertebral and costovertebral fusion results in the formation of syndesmophytes (Fig. 12-4). This reparative process also forms linear bone ossification along the outer fibers of the annulus fibrosus of the disk.

Fig. 12-4 Pathogenesis of the syndesmophyte. The syndesmophyte, along with destruction of the sacroiliac joint, is the hallmark of the inflammatory spondyloarthropathies such as ankylosing spondylitis (AS). It should be distinguished from the osteophyte, which is characteristic of degenerative spondylosis. A, Normal intervertebral disk. The inner fibers of the annulus fibrosus are next to the nucleus pulposus (NP). The outer fibers insert into the periosteum of the vertebral body at least one-third the distance toward the next end-plate. B, With early inflammation, the corners of the bodies are reabsorbed and appear to be square or even eroded. Fine deposits of amorphous apatite (calcium phosphate, a mineral constituent of bone) first appear on radiographs as thin, delicate calcification in the outer fibers of the midannulus. C and D, The process progresses to bridging calcification, with the syndesmophyte extending from one midbody to the next. Thus the spine takes on its bamboo-like appearance on radiographs. (A to C, From Hadler NM: Medical management of the regional musculoskeletal diseases, Orlando, FL, 1984, Grune & Stratton, p 5; D, From Bullough PG: Bullough and Vigorita’s orthopaedic pathology, ed 3, London, 1987, Mosby-Wolfe, p 68.)

This bridging of the vertebrae is most prominent along the anterior longitudinal ligament and occurs earliest in the thoracolumbar region. Destructive changes of the upper and lower corners of the vertebrae (at the insertion of the annulus fibrosus of the disk) are responsible for the vertebral squaring. Late in the disease the vertebral column takes on an appearance that is referred to as bamboo spine.

Extraarticular features: Uveitis, conjunctivitis, colitis, psoriasis, enthesitis, or iritis occurs in nearly 25% of clients and follows a course that is unrelated to the severity of the joint disease.76 Ocular symptoms may precede spinal symptoms by several weeks or even years. Pulmonary changes (chronic infiltrative or fibrotic bullous changes of the upper lobes) occur in 1% to 3% of persons with AS and may be confused with TB.

Cardiomegaly, conduction defects, and pericarditis are well-recognized cardiovascular complications of AS. Occasionally, renal manifestations precede other symptoms of AS.

Complications: The very stiff osteoporotic spine of clients with AS is prone to fracture from even minor trauma. It has been estimated that the incidence of thoracolumbar fractures in AS is four times higher than that in the general population.83 The most common site of fracture is the lower cervical spine. Risk of neurologic damage may be compounded by the development of epidural hematoma from lacerated vessels.