Interviewing as a Screening Tool

The client interview, including the personal and family history, is the single most important tool in screening for medical disease. The client interview as it is presented here is the first step in the screening process.

Interviewing is an important skill for the clinician to learn. It is generally agreed that 80% of the information needed to clarify the cause of symptoms is given by the client during the interview. This chapter is designed to provide the physical therapist with interviewing guidelines and important questions to ask the client.

Medical practitioners (including nurses, physicians, and therapists) begin the interview by determining the client’s chief complaint. The chief complaint is usually a symptomatic description by the client (i.e., symptoms reported for which the person is seeking care or advice). The present illness, including the chief complaint and other current symptoms, gives a broad, clear account of the symptoms—how they developed and events related to them.

Questioning the client may also assist the therapist in determining whether an injury is in the acute, subacute, or chronic stage. This information guides the clinician in addressing the underlying pathology while providing symptomatic relief for the acute injury, more aggressive intervention for the chronic problem, and a combination of both methods of treatment for the subacute lesion.

The interviewing techniques, interviewing tools, Core Interview, and review of the inpatient hospital record in this chapter will help the therapist determine the location and potential significance of any symptom (including pain).

The interview format provides detailed information regarding the frequency, duration, intensity, length, breadth, depth, and anatomic location as these relate to the client’s chief complaint. The physical therapist will later correlate this information with objective findings from the examination to rule out possible systemic origin of symptoms.

The subjective examination may also reveal any contraindications to physical therapy intervention or indications for the kind of intervention that is most likely to be effective. The information obtained from the interview guides the therapist in either referring the client to a physician or planning the physical therapy intervention.

Concepts in Communication

Interviewing is a skill that requires careful nurturing and refinement over time. Even the most experienced health care professional should self-assess and work toward improvement. Taking an accurate medical history can be a challenge. Clients’ recollections of their past symptoms, illnesses, and episodes of care are often inconsistent from one inquiry to the next.1

Clients may forget, underreport, or combine separate health events into a single memory, a process called telescoping. They may even (intentionally or unintentionally) fabricate or falsely recall medical events and symptoms that never occurred. The individual’s personality and mental state at the time of the illness or injury may influence their recall abilities.1

Adopting a compassionate and caring attitude, monitoring your communication style, and being aware of cultural differences will help ensure a successful interview. Using the tools and techniques presented in this chapter will get you started or help you improve your screening abilities throughout the subjective examination.

Compassion and Caring

Compassion is the desire to identify with or sense something of another’s experience and is a precursor of caring. Caring is the concern, empathy, and consideration for the needs and values of others. Interviewing clients and communicating effectively, both verbally and nonverbally, with compassionate caring takes into consideration individual differences and the client’s emotional and psychologic needs.2,3

Establishing a trusting relationship with the client is essential when conducting a screening interview and examination. The therapist may be asking questions no one else has asked before about body functions, assault, sexual dysfunction, and so on. A client who is comfortable physically and emotionally is more likely to offer complete information regarding personal and family history.

Be aware of your own body language and how it may affect the client. Sit down when obtaining the history and keep an appropriate social distance from the client. Take notes while maintaining adequate eye contact. Lean forward, nod, or encourage the individual occasionally by saying, “Yes, go ahead. I understand.”

Silence is also a key feature in the communication and interviewing process. Silent attentiveness gives the client time to think or organize his or her thoughts. The health care professional is often tempted to interrupt during this time, potentially disrupting the client’s train of thought. Silence can give the therapist time to observe the client and plan the next question or step.

Communication Styles

Everyone has a slightly different interviewing and communication style. The interviewer may need to adjust his or her personal interviewing style to communicate effectively.

Relying on one interviewing style may not be adequate for all situations.

There are gender-based styles and temperament/personality-based styles of communication for both the therapist and the client. There is a wide range of ethnic identifications, religions, socioeconomic differences, beliefs, and behaviors for both the therapist and the client.

There are cultural differences based on family of origin or country of origin, again for both the therapist and the client. In addition to spoken communication, different cultural groups may have nonverbal, observable differences in communication style. Body language, tone of voice, eye contact, personal space, sense of time, and facial expression are only a few key components of differences in interactive style.4

Illiteracy

Throughout the interviewing process and even throughout the episode of care, the therapist must keep in mind that an estimated 44 million American adults are illiterate and an additional 35 million read only at a functional level for social survival. According to the National Center for Education Statistics, illiteracy is on the rise in the United States.

Nearly 24 million people in the United States do not speak or understand English. More than one third of English-speaking patients and half of Spanish-speaking patients at U.S. hospitals have low health literacy.5 According to the findings of the Joint Commission, health literacy skills are not evident during most health care encounters. Clear communication and plain language should become a goal and the standard for all health care professionals.6

Low health literacy means that adults with below basic skills have no more than the most simple reading skills. They cannot read a physician’s (or physical therapist’s) instructions or food or pharmacy labels.7

It is likely that the rates of health illiteracy defined as the inability to read, understand, and respond to health information are much higher. It is a problem that has gone largely unrecognized and unaddressed. Health illiteracy is more than just the inability to read. People who can read may still have great difficulty understanding what they read.

The Institute of Medicine (IOM) estimates nearly half of all American adults (90 million people) demonstrate a low health literacy. They have trouble obtaining, processing, and understanding the basic information and services they need to make appropriate and timely health decisions.

Low health literacy translates into more severe, chronic illnesses and lower quality of care when care is accessed. There is also a higher rate of health service utilization (e.g., hospitalization, emergency services) among people with limited health literacy. People with reading problems may avoid outpatient offices and clinics and utilize emergency departments for their care because somebody else asks the questions and fills out the form.7

It is not just the lower socioeconomic and less-educated population that is affected. Interpreting medical jargon and diagnostic test results and understanding pharmaceuticals are challenges even for many highly educated individuals.

We are living at a time when the amount of health information available to us is almost overwhelming, and yet most Americans would be shocked at the number of their friends and neighbors that (sic) can’t understand the instructions on their prescription medications or how to prepare for a simple medical procedure.8,9

English as a Second Language

The therapist must keep in mind that many people in the United States speak English as a second language (ESL) or are limited English proficient (LEP), and many of those people do not read, or write English.10 More than 14 million people age 5 and older in the United States speak English poorly or not at all. Up to 86% of non–English speakers who are illiterate in English are also illiterate in their native language.

In addition, millions of immigrants (and illegal or unregistered citizens) enter U.S. communities every year. Of these people, 1.7 million who are age 25 and older have less than a fifth-grade education. There is a heavy concentration of persons with low literacy skills among the poor and those who are dependent on public financial support.

Although the percentages of illiterate African-American and Hispanic adults are much higher than those of white adults, the actual number of white nonreaders is twice that of African-American and Hispanic nonreaders, a fact that dispels the myth that literacy is not a problem among Caucasians.11

People who are illiterate cannot read instructions on bottles of prescription medicine or over-the-counter medications. They may not know when a medicine is past the date of safe consumption nor can they read about allergic risks, warnings to diabetics, or the potential sedative effect of medications.

They cannot read about “the warning signs” of cancer or which fasting glucose levels signal a red flag for diabetes. They cannot take online surveys to assess their risk for breast cancer, colon cancer, heart disease, or any other life-threatening condition.

The Physical Therapist’s Role

The therapist should be aware of the possibility of any form of illiteracy and watch for risk factors such as age (over 55 years old), education (0 to 8 years or 9 to 12 years but without a high school diploma), lower paying jobs, living below the poverty level and/or receiving government assistance, and ethnic or racial minority groups or history of immigration to the United States.

Health illiteracy can present itself in different ways. In the screening process, the therapist must be careful when having the client fill out medical history forms. The illiterate or functionally illiterate adult may not be able to understand the written details on a health insurance form, accurately complete a Family/Personal History form, or read the details of exercise programs provided by the therapist. The same is true for individuals with learning disabilities and mental impairments.

When given a choice between “yes” and “no” answers to questions, functionally illiterate adults often circle “no” to everything. The therapist should briefly review with each client to verify the accuracy of answers given on any questionnaire or health form.

For example, you may say, “I see you circled ‘no’ to any health problems in the past. Has anyone in your immediate family (or have you) ever had cancer, diabetes, hypertension …” and continue to name some or all of the choices provided. Sometimes, just naming the most common conditions is enough to know the answer is really “no”—or that there may be a problem with literacy.

Watch for behavioral red flags such as misspelling words, not completing intake forms, leaving the clinic before completing the form, outbursts of anger when asked to complete paperwork, asking no questions, missing appointments, or identifying pills by looking at the pill rather than naming the medication or reading the label.12

The IOM has called upon health care providers to take responsibility for providing clear communication and adequate support to facilitate health-promoting actions based on understanding. Their goal is to educate society so that people have the skills they need to obtain, interpret, and use health information appropriately and in meaningful ways.13,14

Therapists should minimize the use of medical terminology. Use simple but not demeaning language to communicate concepts and instructions. Encourage clients to ask questions and confirm knowledge or tactfully correct misunderstandings.13

Resources

There is a text available specifically for physical therapists to help us identify our own culture and recognize the importance of understanding and communicating with clients of different cultural backgrounds. Widely accepted cultural practices of various ethnic groups are included along with descriptions of cultural and language nuances of subcultures within each ethnic group.15 A text on this same topic for health care professionals is also available.16

Identifying individual personality style may be helpful for each therapist as a means of improving communication. Resource materials are available to help with this.17,18 The Myers-Briggs Type Indicator, a widely used questionnaire designed to identify one’s personality type, is also available on the Internet at www.myersbriggs.org.

For the experienced clinician, it may be helpful to reevaluate individual interviewing practices. Making an audio or videotape during a client interview can help the therapist recognize interviewing patterns that may need to improve. Watch and/or listen for any of the guidelines listed in Box 2-1.

Texts are available with the complete medical interviewing process described. These resources are helpful not only to give the therapist an understanding of the training physicians receive and methods they use when interviewing clients, but also to provide helpful guidelines when conducting a physical therapy screening or examination interview.19,20

The therapist should be aware that under federal civil rights laws and the Medicaid Act, any client with LEP has the right to an interpreter free of charge if the health care provider receives federal funding. But keep in mind that quality of care for individuals who are LEP is compromised when qualified interpreters are not used (or available). Errors of omission, false fluency, substitution, editorializing, and addition are common and can have important clinical consequences.10 Standards for medical interpreting professionals in the United States have been published and are available online.21

The American Physical Therapy Association (APTA) makes available a distance-learning course that provides listening and speaking skills needed to communicate effectively with Spanish-speaking clients and their families. Contact Member Services for information at 800-999-2782 and ask for Spanish for Physical Therapists: Tools for Effective Patient Communication.

The Joint Commission’s 2007 report, What did the doctor say? Improving health literacy to protect patient safety, is a must read. It is available online at www.jointcommission.org.

Cultural Competence

Interviewing and communication require a certain level of cultural competence as well. Culture refers to integrated patterns of human behavior that include the language, thoughts, communications, actions, customs, beliefs, values, and institutions of racial, ethnic, religious, or social groups.2,22 Multiculturalism is a term that takes into account that every member of a group or country does not have the same ideals, beliefs, and views.

Cultural competence can be defined as the ability to understand, honor, and respect the beliefs, lifestyles, attitudes, and behaviors of others.23 Cultural competency goes beyond being “politically correct.” As health care professionals, we must develop a deeper sense of understanding of how ethnicity, language, cultural beliefs, and lifestyles affect the interviewing, screening, and healing process.

Minority Groups

The need for culturally competent physical therapy care has come about, in part, because of the rising number of groups in the United States. Groups other than “white” or “Caucasian” counted as race/ethnicity by the U.S. Census are listed in Box 2-2. Previously these groups were referred to as “minorities,” but social scientists are looking for a different term to describe these groups. Terms such as “dominant” and “nondominant” have been suggested when discussing race and ethnicity.

This has come about because some minority groups are no longer a “minority” in the United States due to changing demographics. According to the U.S. Census Bureau, 31% of the U.S. population belongs to a racial/ethnic minority group. By the year 2042, Caucasians will represent less than 50% of the population (currently at approximately 75%).24 Hispanic Americans will comprise nearly a quarter of the American population (currently 12.5% and expected to reach 30% by 2042). African Americans make up 12.5% of the population (as of 1990). This will increase to approximately 15% so that Hispanic Americans will outnumber African Americans by 2 : 1. Asian/Pacific Island Americans will make up almost 10% in 2050.24

Cultural Competence in the Screening Process

Clients from a racial/ethnic background may have unique health care concerns and risk factors. It is important to learn as much as possible about each group served (Case Example 2-1). Clients who are members of a cultural minority are more likely to be geographically isolated and/or underserved in the area of health services. Risk-factor assessment is very important, especially if there is no primary care physician involved.

Communication style may be unique from group to group; be aware of groups in your area or community and learn about their distinctive health features. For example, Native Americans may not volunteer information, requiring additional questions in the interview or screening process. Courtesy is very important in Asian cultures. Clients may act polite, smiling and nodding, but not really understand the clinician’s questions. ESL may be a factor; the client may need an interpreter. The client may not understand the therapist’s questions but will not show his or her confusion and will not ask the therapist to repeat the question.

Cultural factors can affect the way a person follows through on instructions, interprets questions, and participates in his or her own care. In addition to the guidelines in Box 2-1, Box 2-3 offers some “Dos” in a cultural context for the physical therapy or screening interview.

Resources

Learning about cultural preferences helps therapists become familiar with factors that could impact the screening process. More information on cultural competency is available to help therapists develop a deeper understanding of culture and cultural differences, especially in health and health care.4,25,26

The Health Policy and Administration Section of the APTA has a Cross-Cultural & International Special Interest Group (CCISIG) with information available regarding international physical therapy, international health-related issues, and physical therapists working in third world countries or with ethnic groups.27 The APTA also has a department dedicated to Minority and International Affairs with additional information available online regarding cultural competence.23,36

Information on laws and legal issues affecting minority health care are also available. Best practices in culturally competent health services are provided, including summary recommendations for medical interpreters, written materials, and cultural competency of health professionals.36

The APTA’s Tips to Increase Cultural Competency offers information on values and principles integral to culturally competent education and delivery systems, a Publications Corner that includes articles on cultural competence, links to resources, resources for treating patients/clients from diverse background, and more.28 Also, there is a Blueprint for Teaching Cultural Competence in Physical Therapy Education now available that was created by the Committee on Cultural Competence.29 This program is a guide to help physical therapists develop core knowledge, attitudes, and skills specific to developing cultural competence as we meet the needs of diverse consumers and strive to reduce or eliminate health disparities.29

The U.S. Department of Health and Human Services’ Office of Minority Health has published national standards for culturally and linguistically appropriate services (CLAS) in health care. These are available on the Office of Minority Health’s Web site (www.omhrc.gov/clas).30

Resources on the language and cultural needs of minorities, immigrants, refugees, and other diverse populations seeking health care are available, including strategies for overcoming language and cultural barriers to health care.31

The American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons offers a free online mini-test of cultural competence for residents and medical students that physical therapist may find helpful and informative.32 For more specific information about the Muslim culture, visit The Council on American-Islamic Relations33 or the Muslim American Society.34,35

The Gay and Lesbian Medical Association (GLMA) offers publications on professional competencies in providing a safe clinical environment for Lesbian-Gay-Bisexual-Transgender-Intersex (LGBTI) health.37

The Screening Interview

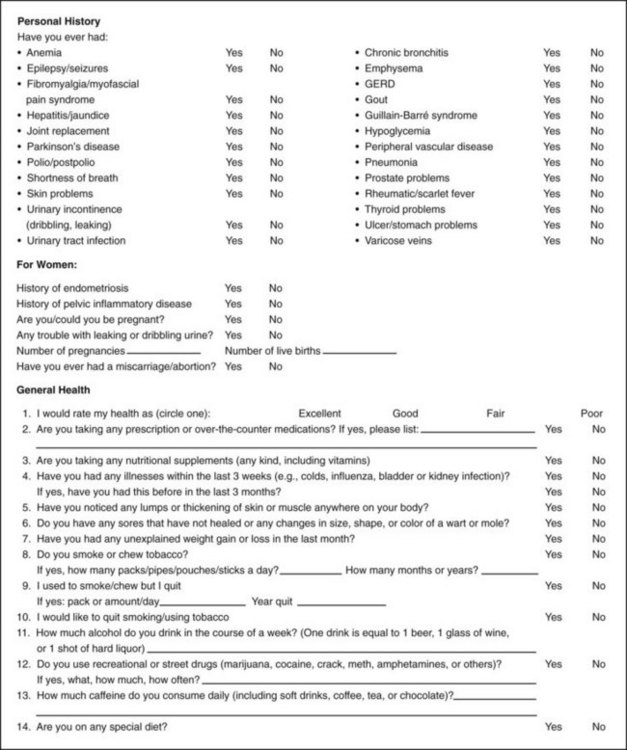

The therapist will use two main interviewing tools during the screening process. The first is the Family/Personal History form (see Fig. 2-2). With the client’s responses on this form and/or the client’s chief complaint in hand, the interview begins.

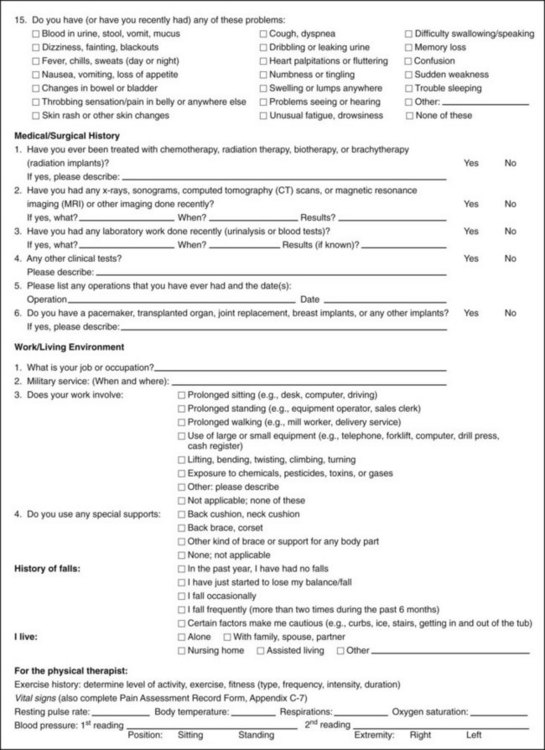

The overall client interview is referred to in this text as the Core Interview (see Fig. 2-3). The Core Interview as presented in this chapter gives the therapist a guideline for asking questions about the present illness and chief complaint. Screening questions may be interspersed throughout the Core Interview as seems appropriate, based on each client’s answers to questions.

There may be times when additional screening questions are asked at the end of the Core Interview or even on a subsequent date at a follow-up appointment. Specific series of questions related to a single symptom (e.g., dizziness, heart palpitations, night pain) or event (e.g., assault, work history, breast examination) are included throughout the text and compiled in the Appendix for the clinician to use easily.

Interviewing Techniques

An organized interview format assists the therapist in obtaining a complete and accurate database. Using the same outline with each client ensures that all pertinent information related to previous medical history and current medical problem(s) is included. This information is especially important when correlating the subjective data with objective findings from the physical examination.

The most basic skills required for a physical therapy interview include:

Open-Ended and Closed-Ended Questions

Beginning an interview with an open-ended question (i.e., questions that elicit more than a one-word response) is advised, even though this gives the client the opportunity to control and direct the interview.38

People are the best source of information about their own condition. Initiating an interview with the open-ended directive, “Tell me why you are here” can potentially elicit more information in a relatively short (5- to 15-minute) period than a steady stream of closed-ended questions requiring a “yes” or “no” type of answer (Table 2-1).39,40 This type of interviewing style demonstrates to the client that what he or she has to say is important. Moving from the open-ended line of questions to the closed-ended questions is referred to as the funnel technique or funnel sequence.

TABLE 2-1

| Open-Ended Questions | Closed-Ended Questions |

| 1. How does bed rest affect your back pain? | 1. Do you have any pain after lying in bed all night? |

| 2. Tell me how you cope with stress and what kinds of stressors you encounter on a daily basis. | 2. Are you under any stress? |

| 3. What makes the pain (better) worse? | 3. Is the pain relieved by food? |

| 4. How did you sleep last night? | 4. Did you sleep well last night? |

Each question format has advantages and limitations. The use of open-ended questions to initiate the interview may allow the client to control the interview (Case Example 2-2), but it can also prevent a false-positive or false-negative response that would otherwise be elicited by starting with closed-ended (yes or no) questions.

False responses elicited by closed-ended questions may develop from the client’s attempt to please the health care provider or to comply with what the client believes is the correct response or expectation.

Closed-ended questions tend to be more impersonal and may set an impersonal tone for the relationship between the client and the therapist. These questions are limited by the restrictive nature of the information received so that the client may respond only to the category in question and may omit vital, but seemingly unrelated, information.

Use of the funnel sequence to obtain as much information as possible through the open-ended format first (before moving on to the more restrictive but clarifying “yes” or “no” type of questions at the end) can establish an effective forum for trust between the client and the therapist.

Follow-Up Questions: The funnel sequence is aided by the use of follow-up questions, referred to as FUPs in the text. Beginning with one or two open-ended questions in each section, the interviewer may follow up with a series of closed-ended questions, which are listed in the Core Interview presented later in this chapter.

For example, after an open-ended question such as: “How does rest affect the pain or symptoms?” the therapist can follow up with clarifying questions such as:

Paraphrasing Technique: A useful interviewing skill that can assist in synthesizing and integrating the information obtained during questioning is the paraphrasing technique. When using this technique, the interviewer repeats information presented by the client.

This technique can assist in fostering effective, accurate communication between the health care recipient and the health care provider. For example, once a client has responded to the question, “What makes you feel better?” the therapist can paraphrase the reply by saying, “You’ve told me that the pain is relieved by such and such, is that right? What other activities or treatment brings you relief from your pain or symptoms?”

If the therapist cannot paraphrase what the client has said, or if the meaning of the client’s response is unclear, then the therapist can ask for clarification by requesting an example of what the person is saying.

Interviewing Tools

With the emergence of evidence-based practice, therapists are required to identify problems, to quantify symptoms (e.g., pain), and to demonstrate the effectiveness of intervention.

Documenting the effectiveness of intervention is called outcomes management. Using standardized tests, functional tools, or questionnaires to relate pain, strength, or range of motion to a quantifiable scale is defined as outcome measures. The information obtained from such measures is then compared with the functional outcomes of treatment to assess the effectiveness of those interventions.

In this way, therapists are gathering information about the most appropriate treatment progression for a specific diagnosis. Such a database shows the efficacy of physical therapy intervention and provides data for use with insurance companies in requesting reimbursement for service.

Along with impairment-based measures therapists must use reliable and valid functional outcome measures. No single instrument or method of assessment can be considered the best under all circumstances.

Pain assessment is often a central focus of the therapist’s interview, so for the clinician interested in quantifying pain, some way to quantify and describe pain is necessary. There are numerous pain assessment scales designed to determine the quality and location of pain or the percentage of impairment or functional levels associated with pain (see further discussion in Chapter 3).

There are a wide variety of anatomic region, function, or disease-specific assessment tools available. Each test has a specific focus—whether to assess pain levels, level of balance, risk for falls, functional status, disability, quality of life, and so on.

Some tools focus on a particular kind of problem such as activity limitations or disability in people with low back pain (e.g., Oswestry Disability Questionnaire,41 Quebec Back Pain Disability Scale,42 Duffy-Rath Questionnaire).43 The Simple Shoulder Test44 and the Disabilities of the Arm, Shoulder, and Hand Questionnaire (DASH)45 may be used to assess physical function of the shoulder. Nurses often use the PQRST mnemonic to help identify underlying pathology or pain (see Box 3-3).

Other examples of specific tests include the

• Visual Analogue Scale (VAS; see Figure 3-6)

• Verbal Descriptor Scale (see Box 3-1)

• McGill Pain Questionnaire (see Fig. 3-11)

A more complete evaluation of client function can be obtained by pairing disease- or region-specific instruments with the Short-Form Health Survey (SF-36 Version 2).46,47 The SF-36 is a well-established questionnaire used to measure the client’s perception of his or her health status. It is a generic measure, as opposed to one that targets a specific age, disease, or treatment group. It includes eight different subscales of functional status that are scored in two general components: physical and mental.

An even shorter survey form (the SF-12 Version 2) contains only 1 page and takes about 2 minutes to complete. There is a Low-Back SF-36 Physical Functioning survey48 and also a similar general health survey designed for use with children (SF-10 for children). All of these tools are available at www.sf-36.org. To see a sample of the SF-36 v.2 go to www.sf-36.org/demos/SF-36v2.html.

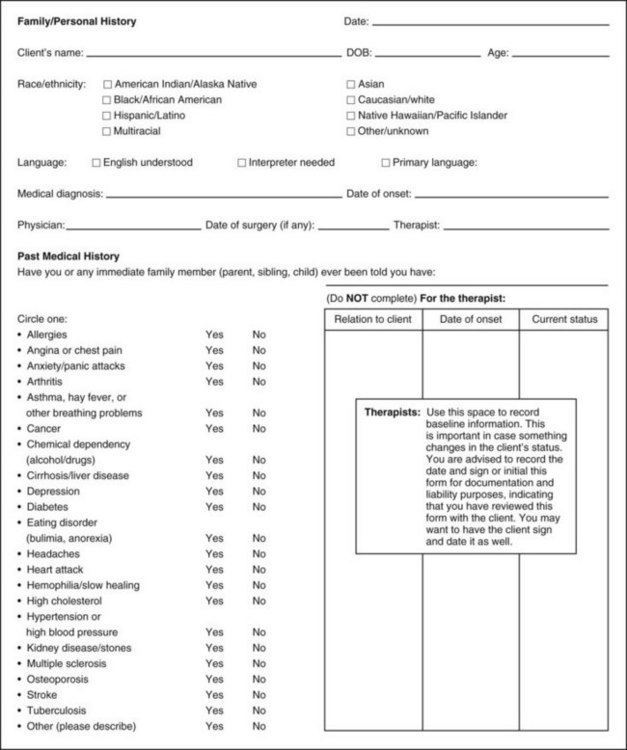

The initial Family/Personal History form (see Fig. 2-2) gives the therapist some idea of the client’s previous medical history (personal and family), medical testing, and current general health status. Make a special note of the box inside the form labeled “Therapists.” This is for liability purposes. Anyone who has ever completed a deposition for a legal case will agree it is often difficult to remember the details of a case brought to trial years later.

A client may insist that a condition was (or was not) present on the first day of the examination. Without a baseline to document initial findings, this is often difficult, if not impossible to dispute. The client must sign or initial the form once it is complete. The therapist is advised to sign and date it to verify that the information was discussed with the client.

Resources: The Family/Personal History form presented in this chapter is just one example of a basic intake form. See the companion website for other useful examples with a different approach. If a client has any kind of literacy or writing problem, the therapist completes it with him or her. If not, the therapist goes over the form with the client at the beginning of the evaluation. The Guide to Physical Therapist Practice49 provides an excellent template for both inpatient and outpatient histories (see the Guide, Appendix 6). Other commercially available forms have been developed for a wide range of prescreening assessments.50

Therapists may modify the information collected from these examples depending on individual differences in client base and specialty areas served. For example, hospital or institution accreditation agencies such as Commission on Accreditation of Rehabilitation Facilities (CARF) and the Joint Commission on Accreditation of Health Care Organizations (JCAHO) may require the use of their own forms.

An orthopedic-based facility or a sports-medicine center may want to include questions on the intake form concerning current level of fitness and the use of orthopedic devices used, such as orthotics, splints, or braces. Therapists working with the geriatric population may want more information regarding current medications prescribed or levels of independence in activities of daily living.

The Review of Systems (see Box 4-19; see also Appendix D-5), which provides a helpful chart of signs and symptoms characteristic of each visceral system, can be used along with the Family/Personal History form. The Guide also provides both an outpatient and an inpatient documentation template for similar purposes (see the Guide, Appendix 6).

A teaching tool with practice worksheets is available to help students and clinicians learn how to document findings from the history, systems review, tests and measures, problems statements, and subjective and objective information using both the SOAP note format and the Patient/Client Management model shown in Fig. 1-4.51

Subjective Examination

The subjective examination is usually thought of as the “client interview.” It is intended to provide a database of information that is important in determining the need for medical referral or the direction for physical therapy intervention. Risk-factor assessment is conducted throughout the subjective and objective examinations.

Key Components of the Subjective Examination

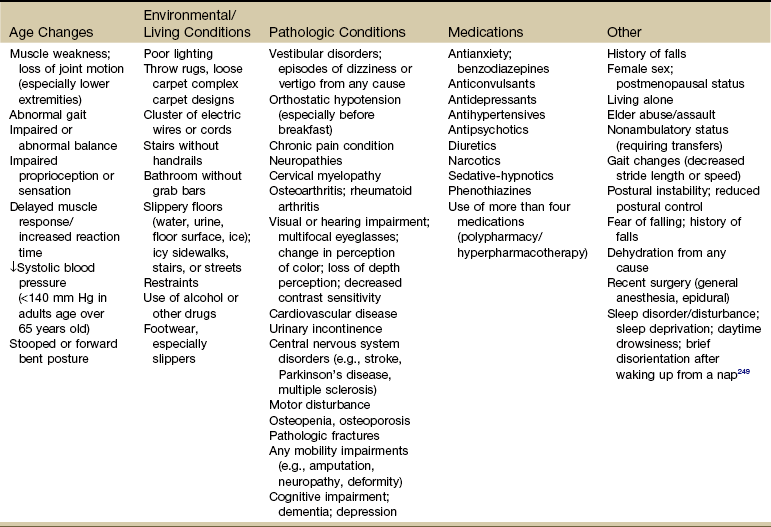

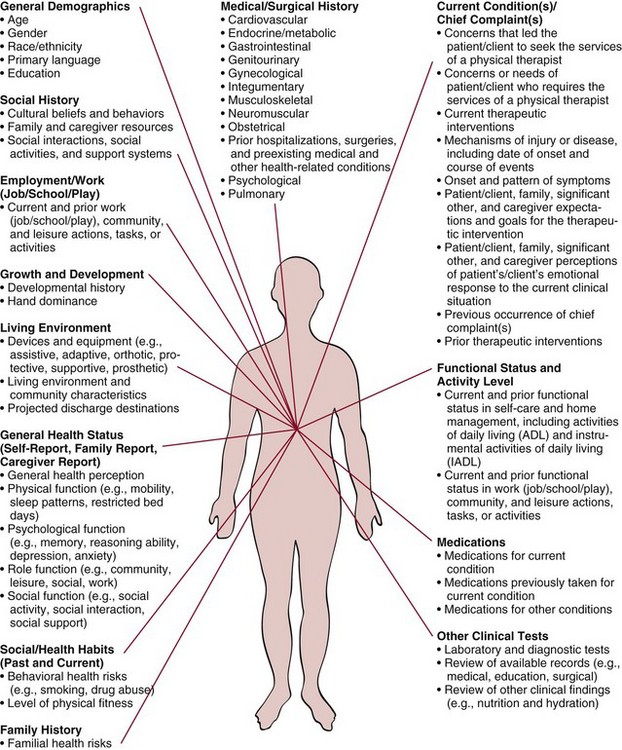

The subjective examination must be conducted in a complete and organized manner. It includes several components, all gathered through the interview process. The order of flow may vary from therapist to therapist and clinic to clinic (Fig. 2-1).

Fig. 2-1 Types of data that may be generated from a client history. In this model, data about the visceral systems is reflected in the Medical/Surgical history. The data collected in this portion of the patient/client history is not the same as information collected during the Review of Systems (ROS). It has been recommended that the ROS component be added to this figure.52 (From Guide to physical therapist practice, ed 2 [Revised], Alexandria, VA, 2003, American Physical Therapy Association.)

The traditional medical interview begins with family/personal history and then addresses the chief complaint. Therapists may find it works better to conduct the Core Interview and then ask additional questions after looking over the client’s responses on the Family/Personal History form.

In a screening model, the therapist is advised to have the client complete the Family/Personal History form before the client-therapist interview. The therapist then quickly reviews the history form, making mental note of any red-flag histories. This information may be helpful during the subjective and objective portions of the examination. Information gathered will include:

Family/Personal History

It is unnecessary and probably impossible to complete the entire subjective examination on the first day. Many clinics or health care facilities use some type of initial intake form before the client’s first visit with the therapist.

The Family/Personal History form presented here (Fig. 2-2) is one example of an initial intake form. Throughout the rest of this chapter, the text discussion will follow the order of items on the Family/Personal History form. The reader is encouraged to follow along in the text while referring to the form.

As mentioned, the Guide also offers a form for use in an outpatient setting and a separate form for use in an inpatient setting. This component of the subjective examination can elicit valuable data regarding the client’s family history of disease and personal lifestyle, including working environment and health habits.

The therapist must keep the client’s family history in perspective. Very few people have a clean and unencumbered family history. It would be unusual for a person to say that nobody in the family ever had heart disease, cancer, or some other major health issue.

A check mark in multiple boxes on the history form does not necessarily mean the person will have the same problems. Onset of disease at an early age in a first-generation family member (sibling, child, parent) can be a sign of genetic disorders and is usually considered a red flag. But an aunt who died of colon cancer at age 75 is not as predictive.

A family history brings to light not only shared genetic traits but also shared environment, shared values, shared behavior, and shared culture. Factors such as nutrition, attitudes toward exercise and physical activity, and other modifiable risk factors are usually the focus of primary and secondary prevention.

Resources

The U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) has developed a computerized tool to help people learn more about their family health history. “My Family Health Portrait” is available online at: www.hhs.gov/familyhistory/download.html.

The download is free and helps identify common diseases that may run in the family. The therapist can encourage each client to use this tool to create and print out a graphic representation of his or her family’s generational health disorders. This information should be shared with the primary health care provider for further screening and evaluation.

Follow-Up Questions (FUPs)

Once the client has completed the Family/Personal History intake form, the clinician can then follow-up with appropriate questions based on any “yes” selections made by the client. Beware of the client who circles one column of either all “Yeses” or all “Nos.” Take the time to carefully review this section with the client. The therapist may want to ask some individual questions whenever illiteracy is suspected or observed.

Each clinical situation requires slight adaptations or alterations to the interview. These modifications, in turn, affect the depth and range of questioning. For example, a client who has pain associated with a traumatic anterior shoulder dislocation and who has no history of other disease is unlikely to require in-depth questioning to rule out systemic origins of pain.

Conversely, a woman with no history of trauma but with a previous history of breast cancer who is self-referred to the therapist without a previous medical examination and who complains of shoulder pain should be interviewed more thoroughly. The simple question “How will the answers to the questions I am asking permit me to help the client?” can serve as your guide.53

Continued questioning may occur both during the objective examination and during treatment. In fact, the therapist is encouraged to carry on a continuous dialogue during the objective examination, both as an educational tool (i.e., reporting findings and mentioning possible treatment alternatives) and as a method of reducing any apprehension on the part of the client. This open communication may bring to light other important information.

The client may wonder about the extensiveness of the interview, thinking, for example, “Why is the therapist asking questions about bowel function when my primary concern relates to back pain?”

The therapist may need to make a qualifying statement to the client regarding the need for such detailed information. For example, questions about bowel function to rule out stomach or intestinal involvement (which can refer pain to the back) may seem to be unrelated to the client but make sense when the therapist explains the possible connection between back pain and systemic disease.

Throughout the questioning, record both positive and negative findings in the subjective and objective reports in order to correlate information when making an initial assessment of the client’s problem. Efforts should be made to quantify all information by frequency, intensity, duration, and exact location (including length, breadth, depth, and anatomic location).

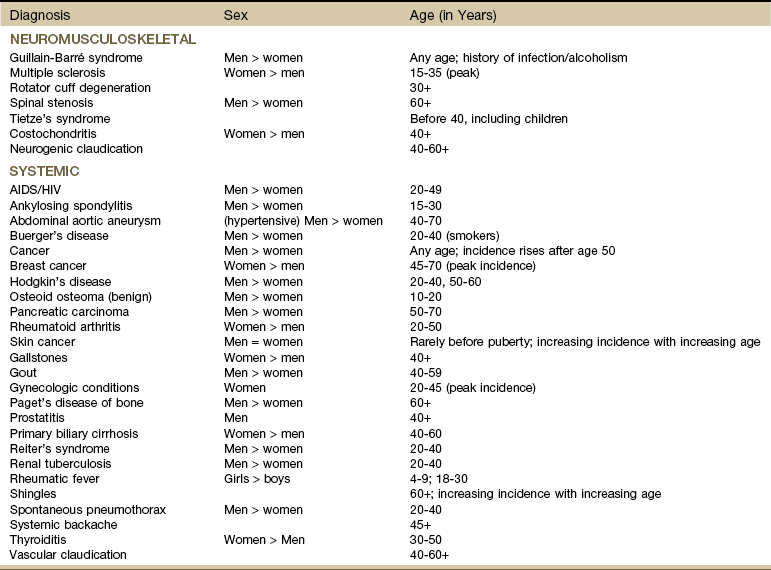

Age and Aging

Age is the most common primary risk factor for disease, illness, and comorbidities. It is the number one risk factor for cancer. The age of a client is an important variable to consider when evaluating the underlying neuromusculoskeletal (NMS) pathologic condition and when screening for medical disease.

Age-related changes in metabolism increase the risk for drug accumulation in older adults. Older adults are more sensitive to both the therapeutic and toxic effects of many drugs, especially analgesics.

Functional liver tissue diminishes and hepatic blood flow decreases with aging, thus impairing the liver’s capacity to break down and convert drugs. Therefore aging is a risk factor for a wide range of signs and symptoms associated with drug-induced toxicities.

It is helpful to be aware of NMS and systemic conditions that tend to occur during particular decades of life. Signs and symptoms associated with that condition take on greater significance when age is considered. For example, prostate problems usually occur in men after the fourth decade (age 40+). A past medical history of prostate cancer in a 55-year-old man with sciatica of unknown cause should raise the suspicions of the therapist. Table 2-2 provides some of the age-related systemic and NMS pathologic conditions.

Epidemiologists report that the U.S. population is beginning to age at a rapid pace, with the first baby boomers turning 65 in 2011. Between now and the year 2020, the number of individuals age 65 and older (referred to by some as the “Big Gray Wave”) will double, reaching 70.3 million and making up a larger proportion of the entire population (increasing from 13% in 2000 to 20% in 2030).54

Of particular interest is the explosive growth expected among adults age 85 and older. This group is at increased risk for disease and disability. Their numbers are expected to grow from 4.3 million in the year 2000 to at least 19.4 million in 2050. As mentioned previously, the racial and ethnic makeup of the older population is expected to continue changing, creating a more diverse population of older Americans.

Human aging is best characterized as the progressive constriction of each organ system’s homeostatic reserve. This decline, often referred to as “homeostenosis,” begins in the third decade and is gradual, linear, and variable among individuals. Each organ system’s decline is independent of changes in other organ systems and is influenced by diet, environment, and personal habits.

Dementia increases the risk of falls and fracture. Delirium is a common complication of hip fracture that increases the length of hospital stay and mortality. Older clients take a disproportionate number of medications, predisposing them to adverse drug events, drug-drug interactions, poor adherence to medication regimens, and changes in pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics related to aging.55,56

An abrupt change or sudden decline in any system or function is always due to disease and not to “normal aging.” In the absence of disease the decline in homeostatic reserve should cause no symptoms and impose no restrictions on activities of daily living regardless of age. In short, “old people are sick because they are sick, not because they are old.”

The onset of a new disease in older people generally affects the most vulnerable organ system, which often is different from the newly diseased organ system and explains why disease presentation is so atypical in this population. For example, at presentation, less than one fourth of older clients with hyperthyroidism have the classic triad of goiter, tremor, and exophthalmos; more likely symptoms are atrial fibrillation, confusion, depression, syncope, and weakness.

Because the “weakest links” with aging are so often the brain, lower urinary tract, or cardiovascular or musculoskeletal system, a limited number of presenting symptoms predominate no matter what the underlying disease. These include:

The corollary is equally important: The organ system usually associated with a particular symptom is less likely to be the cause of that symptom in older individuals than in younger ones. For example, acute confusion in older adults is less often due to a new brain lesion, incontinence is less often due to a bladder disorder; falling, to a neuropathy; or syncope, to heart disease.

Sex and Gender

In the screening process, sex (male versus female) and gender (social and cultural roles and expectations based on sex) may be important issues (Case Example 2-3). To some extent, men and women experience some diseases that are different from each other. When they have the same disease, the age at onset, clinical presentation, and response to treatment is often different.

Men: It may be appropriate to ask some specific screening questions just for men. A list of these questions is provided in Chapter 14 (see also Appendices B-24 and B-37). Taking a sexual history (see Appendix B-32, A and B) may be appropriate at some point during the episode of care.

For example, the presentation of joint pain accompanied by (or a recent history of) skin lesions in an otherwise healthy, young adult raises the suspicion of a sexually transmitted infection (STI). Being able to recognize STIs is helpful in the clinic. The therapist who recognized the client presenting with joint pain of “unknown cause” and also demonstrating signs of an STI may help bring the correct diagnosis to light sooner than later. Chronic pelvic or low back pain of unknown cause may be linked to incest or sexual assault.

The therapist may need to ask men about prostate health (e.g., history of prostatitis, benign prostatic hypertrophy, prostate cancer) or about a history of testicular cancer. In some cases, a sexual history (see Appendix B-32, A and B) may be helpful. Many men with a history of prostate problems are incontinent. Routinely screening for this condition may bring to light the need for intervention.

Men and Osteoporosis: In an awkward twist of reverse bias, many men are not receiving intervention for osteoporosis. In fact the overall prevalence of osteoporosis among men of all ages remains unknown, with ranges from 20% to 36% reported in the literature.57,58 Osteoporosis is prevalent but poorly documented in men in long-term care facilities.59

Men have a higher mortality rate after fracture compared with women.60 Thirty percent of older men who suffer a hip fracture will die within a year of that fracture—double the rate for older adult women. Only 1.1% of the men brought to the hospital for a serious fracture ever receive a bone density test to evaluate their overall risk. Only 1% to 5% of men discharged from the hospital following hip fracture are treated for osteoporosis. This is compared to 27% or more for women.61,62

Keeping this information in mind and watching for risk factors of osteoporosis (see Fig. 11-9) can guide the therapist in recognizing the need to screen for osteoporosis in men and women.

Women: According to the Health Resources and Services Administration (HRSA), women today are more likely than men to die of heart disease, and women between the ages of 26 and 49 are nearly twice as likely to experience serious mental illness as men in the same age group.63

Women have a unique susceptibility to the neurotoxic effects of alcohol. Fewer drinks with less alcohol content have a greater physiologic impact on women compared to men. Women may be at greater risk of alcohol-induced brain injury than men, suggesting medical management of alcoholism in women may require a different approach from that for men.64

Sixty-two percent of American women are overweight and 33% are obese. Lung cancer caused an estimated 27% of cancer deaths among women in 2004, followed by breast cancer (15%) and cancer of the colon and rectum (10%).65

These are just a few of the many ways that being female represents a unique risk factor requiring special consideration when assessing the overall individual and when screening for medical disease.

Questions about past pregnancies, births and deliveries, past surgical procedures (including abortions), incontinence, endometriosis, history of sexually transmitted or pelvic inflammatory disease(s), and history of osteoporosis and/or compression fractures are important in the assessment of some female clients (see Appendix B-37). The therapist must use common sense and professional judgment in deciding what questions to ask and which follow-up questions are essential.

Life Cycles: For women, it may be pertinent to find out where each woman is in the life cycle (Box 2-4) and correlate this information with age, personal and family history, current health, and the presence of any known risk factors. It may be necessary to ask if the current symptoms occur at the same time each month in relation to the menstrual cycle (e.g., day 10 to 14 during ovulation or at the end of the cycle during the woman’s period).

Each phase in the life cycle is really a process that occurs over a number of years. There are no clear distinctions most of the time as one phase blends gradually into the next one.

Perimenopause is a term that was first coined in the 1990s. It refers to the transitional period from physiologic ovulatory menstrual cycles to eventual ovarian shut down. During the perimenopausal time before cessation of menses, signs and symptoms of hormonal changes may become evident. These can include fatigue, memory problems, weight gain, irritability, sleep disruptions, enteric dysfunction, painful intercourse, and change in libido.

Early stages of physiologic perimenopause can occur when a woman is in her mid-30s. Symptoms may not be as obvious in this group of women; infertility may be the most obvious sign in women who have delayed childbirth.66

Menopause is an important developmental event in a woman’s life. Menopause means pause or cessation of the monthly, referring to the menstrual, cycle. The term has been expanded to include approximately  to 2 years before and after cessation of the menstrual cycle.

to 2 years before and after cessation of the menstrual cycle.

Menopause is not a disease but rather a complex sequence of biologic aging events, during which the body makes the transition from fertility to a nonreproductive status. The usual age of menopause is between 48 and 54 years. The average age for menopause is still around 51 years of age, although many women stop their periods much earlier.67-69

The pattern of menstrual cessation varies. It may be abrupt, but more often it occurs over 1 to 2 years. Periodic menstrual flow gradually occurs less frequently, becoming irregular and less in amount. Occasional episodes of profuse bleeding may be interspersed with episodes of scant bleeding.

Menopause is said to have occurred when there have been no menstrual periods for 12 consecutive months. Postmenopause describes the remaining years of a woman’s life when the reproductive and menstrual cycles have ended. Any spontaneous uterine bleeding after this time is abnormal and is considered a red flag.

The significance of postmenopausal bleeding depends on whether or not the woman is taking hormone replacement therapy (HRT) and which regimen she is using. Women who are on continuous-combined HRT (estrogen in combination with progestin taken without a break) are likely to have irregular spotting until the endometrium atrophies, which takes about 6 months. Medical referral is advised if bleeding persists or suddenly appears after 6 months without bleeding.

Women on sequential HRT (estrogen taken daily or for 25 days each month with progestin taken for 10 days) normally bleed lightly each time the progestin is stopped. Postmenopausal bleeding in women who are not on HRT always requires a medical evaluation.

Within the past decade, removal of the uterus (hysterectomy) has become a common major surgery in the United States. In fact, more than one third of the women in the United States have hysterectomies. The majority of these women have this operation between the ages of 25 and 44 years.

Removal of the uterus and cervix, even without removal of the ovaries, usually brings on an early menopause (surgical menopause), within 2 years of the operation. Oophorectomy (removal of the ovaries) brings on menopause immediately, regardless of the age of the woman, and early surgical removal of the ovaries (before age 30) doubles the risk of osteoporosis.

Women and Hormone Replacement Therapy: For a time, it was enough to find out which women in their menopausal years were taking HRT. It was thought these women were protected against cardiac events, osteoporosis, and hip fractures.

Women who were not on HRT were targeted with information about the increased risk of osteoporosis and hip fractures. Anyone with cardiac risk factors was encouraged to begin taking HRT. Research from the landmark Women’s Health Initiative study70 has shown that HRT is not cardioprotective as was once thought. In fact there is an increase in myocardial infarction (MI) and stroke in healthy women taking HRT along with an increase in breast cancer and blood clots. HRT is associated with a decrease in colorectal cancer and hip fracture.70

The next wave of research reported that these findings applied to long-term use, not short-term use to alleviate symptoms. Doctors started prescribing HRT as a short-term intervention to manage symptoms rather than with the intention of replacing naturally diminishing hormones. However, a newer study71 reported there are only 1- to 2-point differences (scale 0-100) for a large study comparing women taking versus not taking HRT for symptomatic relief. After 3 years, even those slight differences disappeared.

Women and Heart Disease: When a 55-year-old woman with a significant family history of heart disease comes to the therapist with shoulder, upper back, or jaw pain, it will be necessary to take the time and screen for possible cardiovascular involvement.

For women, sex-linked protection against coronary artery disease ends with menopause. At age 45 years, one in nine women develops heart disease. By age 65 years, this statistic changes to one in three women.72

Ten times as many women die of heart disease and stroke as they do of breast cancer (about one half million every year in the United States for heart disease compared to about 41,000 from breast cancer).65 More women die of heart disease each year in the United States than the combined deaths from the next seven causes of death in women. In fact, more women than men die of heart disease every year.72,73

Women under 50 are more than twice as likely to die of heart attacks compared to men in the same age group. Two thirds of women who die suddenly have no previously recognized symptoms. Prodromal symptoms as much as 1 month before a myocardial infarction go unrecognized (see Table 6-4).

Therapists who recognize age combined with the female sex as a risk factor for heart disease will look for other risk factors and participate in heart disease prevention. See Chapter 6 for further discussion of this topic.

Women and Osteoporosis: As health care specialists, therapists have a unique opportunity and responsibility to provide screening and prevention for a variety of diseases and conditions. Osteoporosis is one of those conditions.

To put it into perspective, a woman’s risk of developing a hip fracture is equal to her combined risk of developing breast, uterine, and ovarian cancer. Women have higher fracture rates than men of the same ethnicity. Caucasian women have higher rates than black women.

Assessment of osteoporosis and associated risk factors along with further discussion of osteoporosis as a condition are discussed in Chapter 11.

Race and Ethnicity

The distinction between the terms “race” and “ethnicity” is not always clear, and the terms are used interchangeably or combined and discussed as “racial/ethnic minorities.” Social scientists make a distinction in that race describes membership in a group based on physical differences (e.g., color of skin, shape of eyes). Ethnicity refers to being part of a group with shared social, cultural, language, and geographic factors (e.g., Hispanic, Italian).74

An individual’s ethnicity is defined by a unique sociocultural heritage that is passed down from generation to generation but can change as the person changes geographic locations or joins a family with different cultural practices. A child born in Korea but adopted by a Caucasian-American family will grow up speaking English, eating American food, and studying U.S. history. Ethnically, the child is American but will be viewed racially by others as Asian.

The Genome Project dispelled previous ideas of biologic differences based on race. It is now recognized that humans are the same biologically regardless of race or ethnic background.75,76 In light of these new findings, the focus of research is centered now on cultural differences, including religious, social, and economic factors and how these might explain health differences among ethnic groups.

Ethnicity is a risk factor for health outcomes. Despite tremendous advances and improved public health in America, the non-Caucasian racial/ethnic groups listed in Box 2-2 are medically underserved and suffer higher levels of illness, premature death, and disability. These include cancer, heart disease and stroke, diabetes, infant mortality, and HIV and AIDS.77

Racial/ethnic minorities living in rural areas may be at greater risk when health care access is limited.78 For example, American Indians (also referred to as Native Americans) living on reservations may benefit from many services for free that might not be available in other areas, while city-dwelling (urban) American Indians are more likely than the general population to die from diabetes, alcohol-related causes, lung cancer, liver disease, pneumonia, and influenza.79 The therapist must remember to look for these risk factors when conducting a risk-factor assessment.

Black men have a higher risk factor for hypertension and heart disease than white men. Black women have 250% higher incidence with twice the mortality of white women for cervical cancer. Black women are more likely to die of pneumonia, influenza, diabetes, and liver disease. Scientists and epidemiologists ask if this could be the result of socioeconomic factors such as later detection. Perhaps the lack of health insurance prevents adequate screening and surveillance.

Epidemiologists tracking cancer statistics point out that African Americans still have the highest mortality and worst survival of any population and the statistics have not improved significantly over the last 20 years.80 Studies have shown that equal treatment yields equal outcomes among individuals with equal disease.81 Conversely, minority status can be translated into disparities in health care with worse outcomes in many cases for a variety of illnesses.80,82

African-American teenagers and young adults are three to four times more likely to be infected with hepatitis B than whites. Asian Americans and Pacific Islanders are twice as likely as whites to be infected with hepatitis B. Of all the cases of tuberculosis reported in the United States over the last 10 years, almost 80% were in racial/ethnic minorities.77

Mexican Americans, who make up two thirds of Hispanics, are also the largest minority group in the United States. Stroke prevention and early intervention are important in this group because their risk for stroke is much higher than for non-Hispanic or white adults.

Mexican Americans ages 45 to 59 are twice as likely to suffer a stroke, and those in their 60s and early 70s are 60% more likely to have a stroke. Family history of stroke or transient ischemic attack (TIA) is a warning flag in this population.83,84

Other studies are underway to compare ethnic differences among different groups for different diseases (Case Example 2-4).

Resources: Definitions and descriptions for race and ethnicity are available through the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC).85 For a report on racial and ethnic disparities, see the IOM’s Unequal Treatment, Confronting Racial and Ethnic Disparities in Health Care.82

The U.S. National Library of Medicine and the National Institutes of Health offer the latest news on health care issues and other topics related to African Americans.86 Baylor College of Medicine’s Intercultural Cancer Council provides information about cancer and various racial/ethnic groups.87 See also the Kagawa-Singer article for an excellent discussion of cancer, culture, and health disparities.80

Past Medical and Personal History

It is important to take time with these questions and to ensure that the client understands what is being asked. A “yes” response to any question in this section would require further questioning, correlation to objective findings, and consideration of referral to the client’s physician.

For example, a “yes” response to questions on this form directed toward allergies, asthma, and hay fever should be followed up by asking the client to list the allergies and to list the symptoms that may indicate a manifestation of allergies, asthma, or hay fever. The therapist can then be alert for any signs of respiratory distress or allergic reactions during exercise or with the use of topical agents.

Likewise, clients may indicate the presence of shortness of breath with only mild exertion or without exertion, possibly even after waking at night. This condition of breathlessness can be associated with one of many conditions, including heart disease, bronchitis, asthma, obesity, emphysema, dietary deficiencies, pneumonia, and lung cancer.

Some “no” responses may warrant further follow-up. The therapist can screen for diabetes, depression, liver impairment, eating disorders, osteoporosis, hypertension, substance use, incontinence, bladder or prostate problems, and so on. Special questions to ask for many of these conditions are listed in the appendices.

Many of the screening tools for these conditions are self-report questionnaires, which are inexpensive, require little or no formal training, and are less time consuming than formal testing. Knowing the risk factors for various illnesses, diseases, and conditions will help guide the therapist in knowing when to screen for specific problems. Recognizing the signs and symptoms will also alert the therapist to the need for screening.

Eating Disorders and Disordered Eating: Eating disorders, such as bulimia nervosa, binge eating disorder, and anorexia nervosa, are good examples of past or current conditions that can impact the client’s health and recovery. The therapist must consider the potential for a negative impact of anorexia on bone mineral density, while also keeping in mind the psychologic risks of exercise (a common intervention for osteopenia) in anyone with an eating disorder.

The first step in screening for eating disorders is to look for risk factors for eating disorders. Common risk factors associated with eating disorders include being female, Caucasian/white, having perfectionist personality traits, a personal or family history of obesity and/or eating disorders, sports or athletic involvement, and history of sexual abuse or other trauma.

Distorted body image and disordered eating are probably underreported, especially in male athletes. Athletes participating in sports that use weight classifications, such as wrestling and weightlifting, are at greater risk for anorexic behaviors such as fasting, fluid restriction, and vomiting.88

Researchers have recently described a form of body image disturbance in male bodybuilders and weightlifters referred to as muscle dysmorphia. Previously referred to as “reverse anorexia” this disorder is characterized by an intense and excessive preoccupation or dissatisfaction with a perceived defect in appearance, even though the men are usually large and muscular. The goal in disordered eating for this group of men is to increase body weight and size. The use of performance-enhancing drugs and dietary supplements is common in this group of athletes.89,90

Gay men tend to be more dissatisfied with their body image and may be at greater risk for symptoms of eating disorders compared to heterosexual men.91 Screening is advised for anyone with risk factors and/or signs and symptoms of eating disorders. Questions to ask may include:

General Health

Self-assessed health is a strong and independent predictor of mortality and morbidity. People who rate their health as “poor” are four to five times more likely to die than those who rate their health as “excellent.”92,93 Self-assessed health is also a strong predictor of functional limitation.94

At least one study has shown similar results between self-assessed health and outcomes after total knee replacement (TKR).95 The therapist should consider it a red flag anytime a client chooses “poor” to describe his or her overall health.

Medications: Although the Family/Personal History form includes a question about prescription or over-the-counter (OTC) medications, specific follow-up questions come later in the Core Interview under Medical Treatment and Medications. Further discussion about this topic can be found in that section of this chapter.

It may be helpful to ask the client to bring in any prescribed medications he or she may be taking. In the older adult with multiple comorbidities, it is not uncommon for the client to bring a gallon-sized Ziploc bag full of pill bottles. Taking the time to sort through the many prescriptions can be time consuming.

Start by asking the client to make sure each one is a drug that is being taken as prescribed on a regular basis. Many people take “drug holidays” (skip their medications intentionally) or routinely take fewer doses than prescribed.96 Make a list for future investigation if the clinical presentation or presence of possible side effects suggests the need for consultation with the pharmacy.

Recent Infections: Recent infections, such as mononucleosis, hepatitis, or upper respiratory infections, may precede the onset of Guillain-Barré syndrome. Recent colds, influenza, or upper respiratory infections may also be an extension of a chronic health pattern of systemic illness.

Further questioning may reveal recurrent influenza-like symptoms associated with headaches and musculoskeletal complaints. These complaints could originate with medical problems such as endocarditis (a bacterial infection of the heart), bowel obstruction, or pleuropulmonary disorders, which should be ruled out by a physician.

Knowing that the client has had a recent bladder, vaginal, uterine, or kidney infection, or that the client is likely to have such infections, may help explain back pain in the absence of any musculoskeletal findings.

The client may or may not confirm previous back pain associated with previous infections. If there is any doubt, a medical referral is recommended. On the other hand, repeated coughing after a recent upper respiratory infection may cause chest, rib, back, or sacroiliac pain.

Screening for Cancer: Any “yes” responses to early screening questions for cancer (General Health questions 5, 6, and 7) must be followed up by a physician. An in-depth discussion of screening for cancer is presented in Chapter 13.

Changes in appetite and unexplained weight loss can be associated with cancer, onset of diabetes, hyperthyroidism, depression, or pathologic anorexia (loss of appetite). Weight loss significant for neoplasm would be a 10% loss of total body weight over a 4-week period unrelated to any intentional diet or fasting.

A significant, unexplained weight gain can be caused by congestive heart failure, hypothyroidism, or cancer. The person with back pain who, despite reduced work levels and decreased activity, experiences unexplained weight loss demonstrates a key “red flag” symptom.

Weight gain/loss does not always correlate with appetite. For example, weight gain associated with neoplasm may be accompanied by appetite loss, whereas weight loss associated with hyperthyroidism may be accompanied by increased appetite.

Substance Abuse: Substances refer to any agents taken nonmedically that can alter mood or behavior. Addiction refers to the daily need for the substance in order to function, an inability to stop, and recurrent use when it is harmful physically, socially, and/or psychologically. Addiction is based on physiologic changes associated with drug use but also has psychologic and behavioral components. Individuals who are addicted will use the substance to relieve psychologic symptoms even after physical pain or discomfort is gone.

Dependence is the physiologic dependence on the substance so that withdrawal symptoms emerge when there is a rapid dose reduction or the drug is stopped abruptly. Once a medication is no longer needed, the dosage will have to be tapered down for the client to avoid withdrawal symptoms.

Tolerance refers to the individual’s need for increased amounts of the substance to produce the same effect. Tolerance develops in many people who receive long-term opioid therapy for chronic pain problems. If undermedicated, drug-seeking behaviors or unauthorized increases in dosage may occur. These may seem like addictive behaviors and are sometimes referred to as “pseudoaddiction,” but the behaviors disappear when adequate pain control is achieved. Referral to the prescribing physician is advised if you suspect a problem with opioid analgesics (misuse or abuse).97,98

Among the substances most commonly used that cause physiologic responses but are not usually thought of as drugs are alcohol, tobacco, coffee, black tea, and caffeinated carbonated beverages.

Other substances commonly abused include depressants, such as alcohol, barbiturates (barbs, downers, pink ladies, rainbows, reds, yellows, sleeping pills); stimulants, such as amphetamines and cocaine (crack, crank, coke, snow, white, lady, blow, rock); opiates (heroin); cannabis derivatives (marijuana, hashish); and hallucinogens (LSD or acid, mescaline, magic mushroom, PCP, angel dust).

Methylenedioxymethamphetamine (MDMA; also called Ecstasy, hug, beans, and love drug), a synthetic, psychoactive drug chemically similar to the stimulant methamphetamine and the hallucinogen mescaline, has been reported to be sold in clubs around the country. It is often given to individuals without their knowledge and used in combination with alcohol and other drugs.

Public health officials tell us that alcohol and other drug use/abuse is the number one health problem in the United States. Addictions (especially alcohol) have reached epidemic proportions in this country. Yet, it is largely ignored and often goes untreated.99,100 A well-known social scientist in the area of drug studies published a new report showing that overall, alcohol is the most harmful drug (to the individual and to others) with heroin and crack cocaine ranked second and third.101

Up to one third of workers use these illegal, psychoactive substances to face up to job strain.102 Alcohol and other drugs are commonly used to self-medicate mental illness, pain, and the effects of posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD).

Risk Factors: Many teens and adults are at risk for using and abusing various substances (Box 2-5). Often, they are self-medicating the symptoms of a variety of mental illnesses, learning disabilities, and personality disorders. The use of alcohol to self-medicate depression is very common, especially after a traumatic injury or event in one’s life.

Baby boomers (born between 1946 and 1964) with a history of substance use, aging adults (or others) with sleep disturbances or sleep disorders, and anyone with an anxiety or mood disorder is at increased risk for use and abuse of substances.

Think about this in terms of risk-factor assessment. According to the CDC, at least two thirds of boomers who enter drug treatment programs have been drinking, taking drugs, or both during the bulk of their adult lives.

It is estimated that 50% of all traumatic brain-injured (TBI) cases are alcohol- or drug-related—either by the clients themselves or by the perpetrator of the accident. Some centers estimate this figure to be much higher, around 80%.103

Risk factors for opioid misuse in people with chronic pain have been published.98 These include family or personal history of substance abuse or previous alcohol or other drug rehabilitation), young age, history of criminal activity or legal problems (including driving under the influence [DUIs]), risk-taking or thrill-seeking behaviors, heavy tobacco use, and history of severe depression or anxiety). Physicians and clinical psychologists may use one of several tools (e.g., Current Opioid Misuse Measure, Screener and Opioid Assessment for Patients in Pain) to screen for risk of opioid misuse.

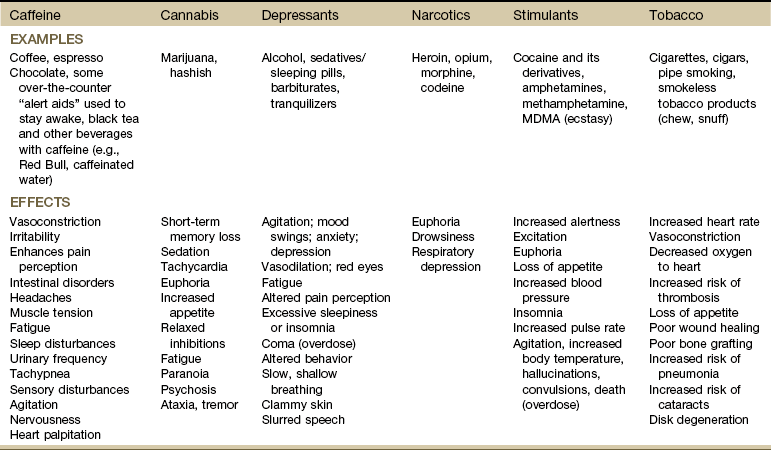

Signs and Symptoms of Substance Use/Abuse: Behavioral and physiologic responses to any of these substances depend on the characteristics of the chemical itself, the route of administration, and the adequacy of the client’s circulatory system (Table 2-3).

TABLE 2-3

Physiologic Effects and Adverse Reactions to Substances

Adapted from Goodman CC, Fuller KS: Pathology: implications for the physical therapist, ed 3, Philadelphia, 2009, WB Saunders.

Behavioral red flags indicating a need to screen can include consistently missed appointments (or being chronically late to scheduled sessions), noncompliance with the home program or poor attention to self-care, shifting mood patterns (especially the presence of depression), excessive daytime sleepiness or unusually excessive energy, and/or deterioration of physical appearance and personal hygiene.

The physiologic effects and adverse reactions have the additional ability to delay wound healing or the repair of soft tissue injuries. Soft tissue infections such as abscess and cellulitis are common complications of injection drug use (IDU). Affected individuals may present with swelling and tenderness in a muscular area from intramuscular injections. Low-grade fever may be found when taking vital signs.104

Substance abuse in older adults often mimics many of the signs of aging: memory loss, cognitive problems, tremors, and falls. Even family members may not recognize when their loved one is an addict. Late-stage abuse (age 60 and older) contributes to weight loss, muscle wasting, and among those who abuse alcohol elevated rates of breast cancer (especially among women).105

Screening for Substance Use/Abuse: Questions designed to screen for the presence of chemical substance abuse need to become part of the physical therapy assessment. Clients who depend on alcohol and/or other substances require lifestyle intervention. However, direct questions may be offensive to some people, and identifying a person as a substance abuser (i.e., alcohol or other drugs) often results in referral to professionals who treat alcoholics or drug addicts, a label that is not accepted in the early stage of this condition.

Because of the controversial nature of interviewing the alcohol- or drug-dependent client, the questions in this section of the Family/Personal History form are suggested as a guideline for interviewing.

After (or possibly instead of) asking questions about use of alcohol, tobacco, caffeine, and other chemical substances, the therapist may want to use the Trauma Scale Questionnaire106 that makes no mention of substances but asks about previous trauma. Questions include106:

These questions are based on the established correlation between trauma and alcohol or other substance use for individuals 18 years old and older. “Yes” answers to two or more of these questions should be discussed with the physician or used to generate a referral for further evaluation of alcohol use. It may be best to record the client’s answers with a simple + for “yes” or a − for “no” to avoid taking notes during the discussion of sensitive issues.

The RAFFT Questionnaire107 (Relax, Alone, Friends, Family, Trouble) poses five questions that appear to tap into common themes related to adolescent substance use such as peer pressure, self-esteem, anxiety, and exposure to friends and family members who are using drugs or alcohol. Similar dynamics may still be present in adult substance users, although their use of drugs and alcohol may become independent from these psychosocial variables.

• R: Relax—Do you drink or take drugs to relax, feel better about yourself, or fit in?

• A: Alone—Do you ever drink or take drugs while you are alone?

• F: Friends—Do any of your closest friends drink or use drugs?

• F: Family—Does a close family member have a problem with alcohol or drugs?

• T: Trouble—Have you ever gotten into trouble from drinking or taking drugs?

Depending on how the interview has proceeded thus far, the therapist may want to conclude with one final question: “Are there any drugs or substances you take that you haven’t mentioned?” Other screening tools for assessing alcohol abuse are available, as are more complete guidelines for interviewing this population.20,108

Resources: Several guides on substance abuse for health care professionals are available.109,110 These resources may help the therapist learn more about identifying, referring, and preventing substance abuse in their clients.

The University of Washington provides a Substance Abuse Screening and Assessments Instruments database to help health care providers find instruments appropriate for their work setting.111 The database contains information on more than 225 questionnaires and interviews; many have proven clinical utility and research validity, while others are newer instruments that have not yet been thoroughly evaluated.

Many are in the public domain and can be freely downloaded from the Web; others are under copyright and can only be obtained from the copyright holder. The Partnership for a Drug-Free America also provides information on the effects of drugs, alcohol, and other illicit substances available at www.drugfree.org.

Alcohol: Other than tobacco, alcohol is the most dominant addictive agent in the United States. Alcohol use disorder rates are higher among males than females and highest in the youngest age cohort (18 to 29 years).112