Lymph Node Palpation

Part of the screening process for the therapist may involve visual inspection of the skin overlying lymph nodes and palpation of the lymph nodes. Look for any obvious areas of swelling or redness (erythema) along with any changes in skin color or pigmentation. Ask about the presence or recent history of sores or lesions anywhere on the body.

Keep in mind the therapist cannot know what the underlying pathology may be when lymph nodes are palpable and questionable. Performing a baseline assessment and reporting the findings is the important outcome of the assessment.

Whenever examining a lump or lesion, use the mnemonic in Box 4-11 to document and report findings on location, size, shape, consistency, mobility or fixation, and signs of tenderness (see also Box 4-18). Review Special Questions to Ask: Lymph Nodes at the end of this chapter for appropriate follow-up questions.

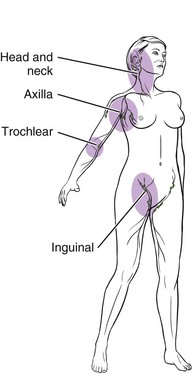

There are several sites where lymph nodes are potentially observable and palpable (Fig. 4-40). Palpation must be done lightly. Excessive pressure can press a node into a muscle or between two muscles. “Normal” lymph nodes usually are not visible or easily palpable. Not all visible or palpable lymph nodes are a sign of cancer. Infections, viruses, bacteria, allergies, thyroid conditions, and food intolerances can cause changes in the lymph nodes.

Fig. 4-40 Locations of most easily palpable lymph nodes. Epitrochlear nodes are located on the medial side of the arm above the elbow in the depression above and posterior to the medial condyle of the humerus. Horizontal and vertical chains of inguinal nodes may be palpated in the same areas as the femoral pulse. Popliteal lymph nodes (not shown) are deep but may be palpated in some clients with the knee slightly flexed.

People with seasonal allergies or allergic rhinitis often have enlarged, tender, and easily palpable lymph nodes in the submandibular and supraclavicular areas. This is a sign that the immune system is working hard to stop as many perceived pathogens as possible.

Children often have easily palpable and tender lymph nodes because their developing immune system is continuously filtering out pathogens. Anyone with food intolerances or celiac sprue can have the same lymph node response in the inguinal area.

Studies show lymph node changes occur after total hip arthroplasty. The presence of polyethylene or metal debris in lymph nodes of the ipsilateral side have been demonstrated.101

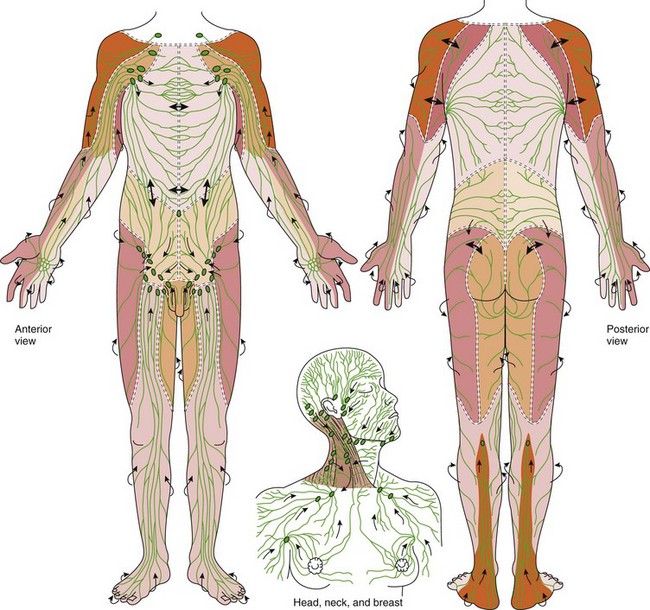

The therapist is most likely to palpate enlarged lymph nodes in the neck, supraclavicular, and axillary areas during an upper quadrant examination (Fig. 4-41). Virchow’s node, a palpable enlargement of one of the supraclavicular lymph nodes may be palpated in the supraclavicular area in the presence of primary carcinoma of thoracic or abdominal organs. Virchow’s node is more often found on the left side.

Fig. 4-41 Regional lymphatic system. A, Superficial and deep collecting channels and their lymph node chains. Lymph territories are indicated by different shadings. Territories are separated by watersheds (marked by = = = ). Normal drainage is away from the watershed. B, Lymph nodes of the head, neck, and chest and the direction of their drainage. The head and neck areas are divided into the anterior and posterior triangles divided by the sternocleidomastoid muscle. There are an estimated 75 lymph nodes on each side of the neck. The deep cervical chain is located in the anterior triangle, largely obstructed by the overlying sternocleidomastoid muscle. (From Casley-Smith JR: Modern treatment for lymphoedema, ed 5, Adelaide, Australia, 1997, Lymphoedema Association of Australia. Modified from Földi M, Kubik S: Lehrbuch der lymphologie fur mediziner und physiotherapeuter mit anhang: praktische linweise fur die physiotherape, Stuttgart, Germany, 1989, Gustav Fischer Verlag.)

Posterior cervical lymph node enlargement can occur during the icteric stage of hepatitis (see Table 9-3). Swelling of the regional lymph nodes often accompanies the first stage of syphilis that is usually painless. These glands feel rubbery, freely movable, and are not tender on palpation. This may be followed by a general lymphadenopathy palpable in the posterior cervical or epitrochlear nodes (located in the inner condyle of the humerus).

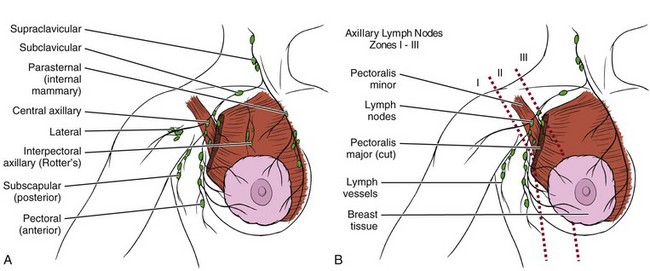

The axillary lymph nodes are divided into three zones based on regional orientation102 (Fig. 4-42). Only zones I and II are palpable. Zone I nodes are superficial and palpable with the client sitting (preferred) or supine with the client’s arm supported by the examiner’s hand and forearm. Gently palpate the entire axilla for any lymph nodes.

Fig. 4-42 A, The breast has an extensive network of venous and lymphatic drainage. Most of the lymphatic drainage empties into axillary nodes. The main lymph node chains and lymphatic drainage are labeled as shown here. B, Axillary lymph nodes are divided into three zones based on anatomic sites. Level I axillary lymph nodes are defined as those nodes lying lateral to the lateral border of the pectoralis minor muscle. Level II nodes are under the pectoralis minor muscle, between its lateral and medial borders. Level III nodes lie medial to the clavipectoral fascia, which invests the pectoralis minor muscle and covers the axillary nodes. Only Zones I and II are palpable. Level III nodes are accessed only through penetration of the investing layer, usually during axillary surgery. (From Townsend CM: Sabiston textbook of surgery, ed 18, Philadelphia, 2008, Saunders.)

Zone II lymph nodes are palpated with the client in sitting position. Zone II lymph nodes are below the clavicle in the area of the pectoralis muscle. The examiner must reach deep into the axilla to palpate for these lymph nodes.

To examine the right axilla, the examiner supports the client’s right arm with his or her own right forearm and hand (reverse for palpation of the left axillary lymph nodes) (Fig. 4-43). This will help ensure relaxation of the chest wall musculature. Lift the client’s upper arm up from under the elbow while reaching the fingertips of the left hand up as high as possible into the axilla.

Fig. 4-43 Palpation of Zone II lymph nodes in the sitting position. See description in text. (From Seidel HM, Ball JW, Dains JE: Mosby’s physical examination handbook, ed 3, St. Louis, 2003, Mosby.)

The examiner’s fingertips will be against the chest wall and should be able to feel the rib cage (and any palpable lymph nodes). As the client’s arm is lowered slowly, allow the fingertips to move down over the rib cage. Feel for the central nodes by compressing them against the chest wall and muscles of the axilla. The examiner may want to repeat this motion a second or third time until becoming more proficient with this examination technique.

Whenever the therapist encounters enlarged or palpable lymph nodes, ask about a past medical history of cancer (Case Example 4-3), implants, mononucleosis, chronic fatigue, allergic rhinitis, and food intolerances. Ask about a recent cut or infection in the hand or arm. Any tender, moveable nodes present may be associated with these conditions, pharyngeal or dental infections, and other infectious diseases.

Lymph nodes that are hard, immovable, and nontender raise the suspicion of cancer, especially in the presence of a previous history of cancer. Previous editions of this textbook mentioned that any change in lymph nodes present for more than one month in more than one location was a red flag. This has changed with the increased understanding of cancer metastases via the lymphatic system and the potential for cancer recurrence. The most up-to-date recommendation is for physician evaluation of all suspicious lymph nodes.

Musculoskeletal Screening Examination

Muscle pain, weakness, poor coordination, and joint pain can be caused by many systemic disorders such as hypokalemia, hypothyroidism, dehydration, alcohol or drug use, vascular disorders, GI disorders, liver impairment, malnutrition, vitamin deficiencies, and psychologic factors.

In a screening examination of the musculoskeletal system, the client is observed for any obvious deformities, abnormalities, disabilities, and asymmetries. Inspection and palpation of the skin, muscles, soft tissues, and joints often takes place simultaneously.

Assess each client from the front, back, and each side. Some general examination principles include103:

• Let the client know what to expect; offer simple but clear instructions and feedback.

• When comparing sides, test the “normal” side first.

• Examine the joint above and below the “involved” joint.

• Perform active, passive, and accessory or physiologic movements in that order unless circumstances direct otherwise.

• Resisted isometric movements (break test) follow accessory or physiologic motion.

• Resisted isometric motion is done in a physiologic neutral position (open pack position); the joint should not move.

• Painful joint motion or painful empty end feel of a joint should not be forced.

• Inspect and palpate the skin and surrounding tissue for erythema, swelling, masses, tenderness, temperature changes, and crepitus.

• The forward bend and full squat positions as well as walking on toes and heels and hopping on one leg are useful general screening tests.

• Perform specific special tests last based on client history, and results of the screening interview and clinical findings so far.

The Guide suggests key tests and measures to include in a comprehensive screening and specific testing process of the musculoskeletal system, including:

• Patient/client history (demographics, social and employment history, family and personal history, results of other clinical tests)

• Aerobic capacity and endurance

• Anthropometric characteristics

• Arousal, attention, and cognition

• Environmental, home, and work barriers

• Ergonomics and body mechanics

• Gait, locomotion, and balance

• Motor function (motor control and motor learning)

• Muscle performance (strength, power, and endurance)

These steps lead to a diagnostic classification or when appropriate, to a referral to another practitioner.18 Assessing joint or muscle pain is discussed in greater depth in Chapter 3 (see also Appendix B-18).

Neurologic Screening Examination

Much of the neurologic examination is actually completed in conjunction with other parts of the physical assessment. Acute insult or injury to the neurologic system may cause changes in neurologic status requiring frequent reassessment. Systemic disease can produce nerve damage; careful assessment can help pinpoint the area of pathology. A family history of neurologic disorders or personal history of diabetes, hypertension, high cholesterol, cancer, seizures, or heart disease may be significant.

There are six major areas to assess:

1. Mental and emotional status

3. Motor function (gross motor and fine motor; coordination, gait, balance)

4. Sensory function (light touch, vibration, pain, pressure, and temperature)

As always start with the client’s history and note any previous trauma to the head or spine along with reports of headache, confusion (increased confusion), dizziness (see Appendix B-11), seizures, or other neurologic signs and symptoms. Note the presence of any incoordination, tremors, weakness, or abnormal speech patterns.

As mentioned previously, neurologic symptoms with no apparent cause such as paresthesias, dizziness, and weakness may actually be symptoms of depression. This is particularly true if the neurologic symptoms are symmetric or not anatomic.104

If there are no positive findings upon gross examination of the nervous system (e.g., reflexes, muscle tone assessment, gross manual muscle testing, sensation), further testing may not be required. For example, sensory function is not assessed if motor function is intact and there are no client reports of specific sensory problems or changes.

Keep in mind that fatigue and side effects of medications can affect the results of a neurologic exam. Give instructions clearly and take the time needed to map out any areas of deficit observed during the initial screening examination.

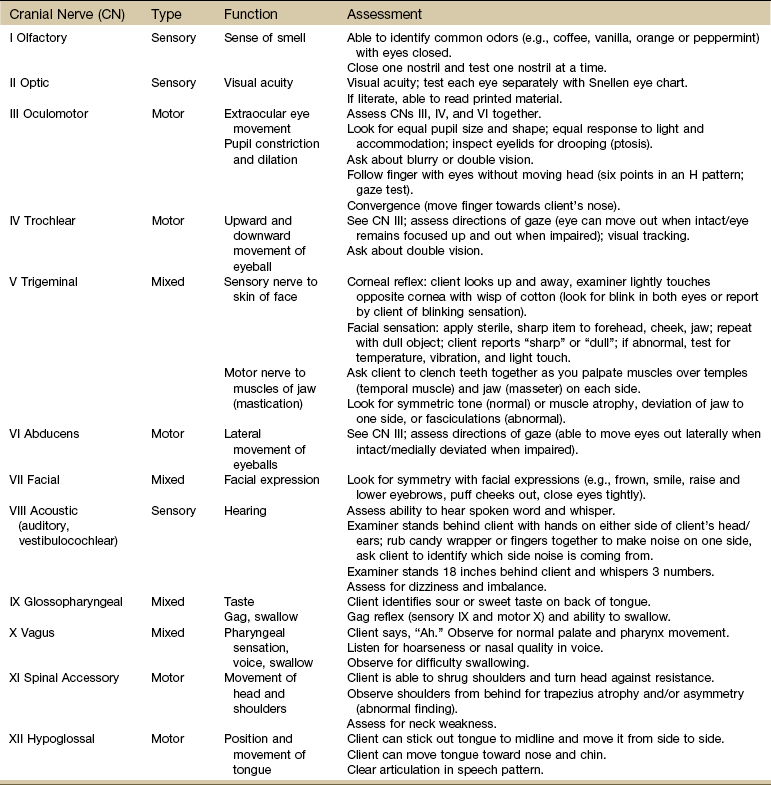

Cranial Nerves

A neurologic screening exam may not involve a survey of the cranial nerves unless the therapist finds reason to perform a more focused neurologic exam. Many of the cranial nerves can be tested during other portions of the physical assessment. When conducting a cranial nerve assessment, follow the information in Table 4-9.

Motor Function

Motor and cerebellar function can be screened most easily by observation of gait, posture, balance, strength, coordination, muscle tone, and motion. Most of these tests are performed as part of the musculoskeletal exam. See previous discussion on Musculoskeletal Screening Examination in this chapter.

Specific tests, such as tandem walking, Romberg’s test, diadochokinesia (rapid, alternating movements of the hands or fingers such as repeatedly alternating forearm pronation to supination, the finger-to-nose/finger-to-finger, and thumb-to-finger opposition tests), can be added for more in-depth screening. Demonstrate all test maneuvers in order to prevent poor performance from a lack of understanding rather than from neurologic impairment.

Sensory Function

Screening for sensory function can begin with superficial pain (pinprick) and light touch (cotton ball) on the extremities. Show the client the items you will be using and how they will be used. For light touch, dab the skin lightly; do not stroke.

Tests are done with the client’s eyes closed. Ask the client to tell you where the sensation is felt or to identify “sharp” or “dull.” Apply the stimulus randomly and bilaterally over the face, neck, upper arms, hands, thighs, lower legs, and feet. Allow at least 2 seconds between the time the stimulus is applied and the next one is given. This avoids the summation effect.

Follow-up with temperature using test tubes filled with hot and cold water and vibration using a low-pitch tuning fork over peripheral joints. Temperature can be omitted if pain sensation is normal. Apply the stem of the vibrating tuning fork to the distal interphalangeal joint of fingers and interphalangeal joint of the great toe, elbow, and wrist. Ask the client to tell you when vibration is first felt and when it stops. Remember, aging adults often lose vibratory sense in the great toe and ankle on both sides.

Other tests include proprioception (joint position sense), kinesthesia (movement sense), stereognosis (identification of common object placed in the hand), graphesthesia (identifying number or letter when drawn on the palm of the hand), and two-point discrimination. Again, all tests should be performed on both sides.

Reflexes

Deep tendon reflexes (DTRs) are tested in a screening examination at the

These reflexes are assessed for symmetry and briskness using the following scale:

| 0 | No response, absent |

| +1 | Low normal, decreased; slight muscle contraction |

| +2 | Normal, visible muscle twitch producing movement of arm/leg |

| +3 | More brisk than normal, increased or exaggerated; may not indicate disease |

| +4 | Hyperactive; very brisk, clonus; spinal cord disorder suspected |

A change in 1 or more DTRs is a yellow (caution) flag. Some individuals have very brisk reflexes normally, while others are much more hyporeflexive. Whenever encountering increased (hyper-) or decreased (hypo-) reflexes, the therapist routinely follows several guidelines:

The isolated DTR that does not fit the client’s physiologic pattern must be considered a red flag. As discussed in Chapter 2, one red flag by itself does not require immediate medical follow-up. But a hyporesponsive patellar tendon reflex that is reproducible and is accompanied by back, hip, or thigh pain in the presence of a past history of prostate cancer offers a different picture altogether.

A diminished reflex may be interpreted as the sign of a possible “space-occupying lesion”—most often, a disc protruding from the disc space and either pressing on a spinal nerve root or irritating the spinal nerve root (i.e., chemicals released by the herniation in contact with the nerve root can cause nerve root irritation).

Tumors (whether benign or malignant) can also press on the spinal nerve root, mimicking a disc problem. A small lesion can put just enough pressure to irritate the nerve root, resulting in a hyperreflexive DTR. A large tumor can obliterate the reflex arc resulting in diminished or absent reflexes. Either way, changes in DTRs must be considered a yellow (caution) or red (warning) flag sign to be documented, reported, and further investigated.

Superficial (cutaneous) reflexes (e.g., abdominal, cremasteric, plantar) can also be tested using the handle of the reflex hammer. The abdominal reflex is elicited by applying a stroking motion with a cotton-tipped applicator (or handle of the reflex hammer) toward the umbilicus. A positive sign of neurologic impairment is observed if the umbilicus moves toward the stroke. The test can be repeated in each abdominal quadrant (upper abdominal T7-9; lower abdominal T11-12).

The cremasteric reflex is elicited by stroking the thigh downward with a cotton-tipped applicator (or handle of the reflex hammer). A normal response in males is an upward movement of the testicle (scrotum) on the same side. The absence of a cremasteric reflex is indication of disruption at the T12-L1 level. Testing the cremasteric reflex may help the therapist identify neurologic impairment in any male with suspicious back, pelvic, groin (including testicular), and/or anterior thigh pain.

The plantar reflex occurs when the sole of the foot is stroked and the toes plantarflex downward.

Neural Tension

Excessive nerve tightness or adhesion can cause adverse neural tension in the peripheral nervous system. When the nerve cannot slide or glide in its protective sheath, neural extensibility and mobility are impaired. The clinical result can be numbness, tingling, and pain. This could be caused by disc protrusion, scar tissue, or space-occupying lesions including cysts, bone spurs, tumors, and cancer metastases.105,106

A positive neural tension test does not tell the therapist what is the underlying etiology—only that the peripheral nerve is involved. History and physical examination are still very important in assessing the clinical presentation.

Someone with full ROM accompanied by negative articular signs but with impaired neural extensibility and mobility raises a yellow (caution) flag. A second look at the history and a more thorough neurologic exam may be warranted.

Reducing symptoms with neural mobilization does not rule out the possibility of cancer. A red flag is raised with any client who responds well to neural mobilization but experiences recurrence of symptoms. This could be a sign that the tumor has grown larger or cancer metastases have progressed, once again interfering with neural mobility.

Regional Screening Examination

Screening of the head and neck areas takes place when client history and report of symptoms or clinical presentation warrant this type of examination. The head and neck assessment provides information about oral health and the general health of multiple systems including integumentary, neurologic, respiratory, endocrine, hepatic, and gastrointestinal.

The head, hair and scalp, and face are observed for size, shape, symmetry, cleanliness, and presence of infection. Position of the head over the spine and in relation to midline and range-of-motion testing of the cervical spine and temporomandibular joints can be part of the screening and posture assessment.

Because the head and neck have a large blood supply, infection from the mouth can quickly spread throughout the body increasing the risk of osteomyelitis, pneumonia, and septicemia in critically ill patients. Evidence of gum disease (e.g., bright red, enlarged, spongy, or bleeding) should be medically evaluated. Ulcerations on the tongue, lips, or gums also require further medical/dental evaluation.

The eyes can be examined for changes in shape, motor function, and color (conjunctiva and sclera). Conducting an assessment of cranial nerves II, III, and IV also will help screen for visual problems. The therapist should be aware that there are changes in the way older adults perceive color. This kind of change can affect function and safety; for example, some older adults are unable to tell when floor tiles end and the bathtub begins in a bathroom. Stumbling and loss of balance can occur at boundary changes.

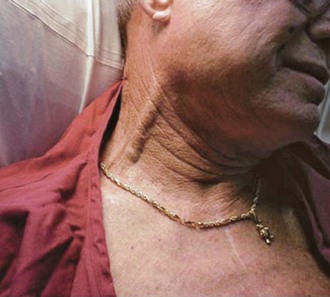

Assessment of cranial nerves (see Table 4-9), regional lymph nodes (see discussion, this chapter), carotid artery pulses (see Fig. 4-1), and jugular vein patency (Fig. 4-44) are part of the head and neck screening examination. Therapists in a primary care setting may also examine the position of the trachea and thyroid for obvious deviations or palpable lesions.

Fig. 4-44 Jugular venous distention is a sign of increased venous return (volume overload) or heart failure, especially congestive heart failure and requires immediate medical attention if not previously reported. Inspect the jugular veins with the client sitting up at a 90-degree angle and again with the head at a 30- to 45-degree angle. The cervical spine should be in a neutral position. Correlate findings of this exam with vital signs, breath and heart sounds, peripheral edema, and auscultation of the carotid arteries for bruits. (From http://courses.cvcc.vccs.edu/WisemanD/index.htm, and Goldman L: Cecil medicine, ed 23, Philadelphia, 2008, WB Saunders.)

Headaches are common and often the result of specific foods, stress, muscle tension, hormonal fluctuations, nerve compression, or cervical spine or temporomandibular joint dysfunction. Most headaches are acute and self-limited. Headaches can be a symptom of a serious medical condition and should be assessed carefully (see Appendix B-17; see also the discussion of viscerogenic causes of head and neck pain in Chapter 14).

Upper and Lower Extremities

The extremities are examined through a systematic assessment of various aspects of the musculoskeletal, neurologic, vascular, and integumentary systems. Inspection and palpation are two techniques used most often during the examination. A checklist can be very helpful (Box 4-16).

Peripheral Vascular Disease

Peripheral vascular disease (PVD), both arterial and venous conditions, is a common problem observed in the extremities of older adults, especially those with a history of heart disease. Knowing the risk factors for any condition, but especially problems like PVD, helps the therapist know when to screen. These conditions, including risk factors, are discussed in greater depth in Chapter 6.

The first signs of vascular occlusive disease are often skin changes (see Box 4-13). The therapist must watch out for common risk factors, including bedrest or prolonged immobility, use of IV catheters, obesity, MI, heart failure, pregnancy, postoperative patients, and any problems with coagulation.

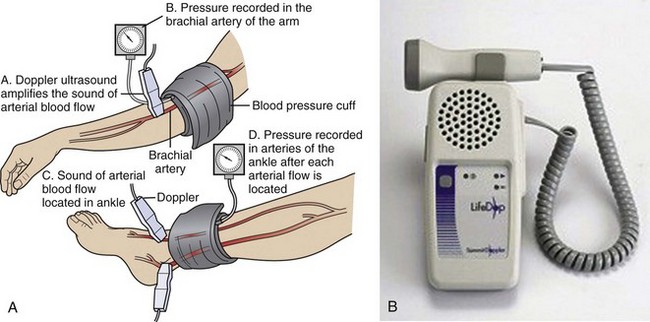

Screening assessment of peripheral arterial disease (PAD) can be done using the ankle-brachial index (ABI) (Fig. 4-45). In fact, the American Diabetes Association recommends screening for anyone with diabetes who is 50 years old or older. Others who can benefit from screening include clients with risk factors for PAD such as smoking, advancing age, hypertension, hyperlipidemia, and symptoms of claudication.

Fig. 4-45 A, Peripheral vascular testing is usually performed in a vascular laboratory, but an approximation of the integrity of the peripheral arterial circulation can be found by calculating the ankle/brachial index (ABI) by using a Doppler device to compare systolic blood pressures in the foot and arm. B, The ABI is measured using a simple, noninvasive tool. Example of a handheld Doppler device with speaker is shown. Devices with an attached stethoscope are also used to measure the ABI. The index correlates well with blood vessel disease severity and symptoms. In the normal individual, the systolic blood pressure in the legs is slightly greater than or equal to the brachial (arm) systolic blood pressure (ABI = 1.0 or above). Where there is arterial obstruction and narrowing, systolic blood pressure is reduced below the area of obstruction. When the ankle systolic blood pressure falls below the brachial systolic blood pressure, the ABI is less than 1.0 (a sign of peripheral vascular obstruction). (From Roberts JR: Clinical procedures in emergency medicine, ed 5, Philadelphia, 2010, WB Saunders.)

Baseline ABI should be taken on both sides for anyone who has (or may have) PAD. Clients with diabetes who have normal ABI levels should be retested periodically.105,107 The ABI is the ratio of the SBP in the ankle divided by the SBP at the arm:

Assess ankle SBP using both the dorsalis pedis pulse and the posterior tibial pulse. Divide the higher SBP from each leg by the higher brachial systolic pressure (i.e., if the SBP is higher in the right arm use that figure for the calculations in both legs).

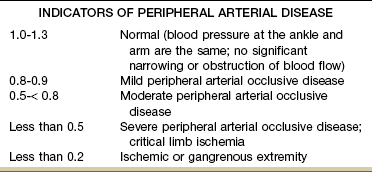

Normal ABI values lie in the range of 0.91 to 1.3. A general guideline is provided in Table 4-10. Recall what was said earlier in this chapter about normal BPs in the legs versus the arms: SBP in the legs is normally 10% to 20% higher than the brachial artery pressure in the arms, resulting in an ABI greater than 1.0. PAD obstruction is indicated when the ABI values fall to less than 1.0.

TABLE 4-10

Ankle Brachial Index Reading*

*Different sources offer slightly different ABI values for normal to severe PAD. Some sources use values between 0.90 and 0.97 as the lower end of normal. Values greater than 1.3 are not considered reliable because calcified vessels show falsely elevated pressures. The therapist should follow guidelines provided by the physician or facility.

Data from Sacks D, et al.: Position statement on the use of the ankle brachial index in the evaluation of patients with peripheral vascular disease. A consensus statement developed by the Standards Division of the Society of Interventional Radiology, J Vasc Interv Radiol 13:353, 2002.

Rubor on dependency is another test used to observe the adequacy of arterial circulation. Place the client in the supine position and observe the color of the soles of the feet. Normal feet should be pink or flesh colored in Caucasians and tan or brown in clients with dark skin tones. The feet of clients with impaired circulation are often chalky white (Caucasians) or gray or white in clients with darker skin.

Elevate the legs to 45 degrees (above the heart level). For clients with compromise of the arterial blood supply, any color present will quickly disappear in this position; in other words, the elevated foot develops increased pallor. No change (or little change) is observed in the normal individual. Bring the individual to a sitting position with the legs dangling. Venous filling is delayed following foot elevation. Color change in the lower leg and foot may take 30 seconds or more and will be a very bright red (dependent rubor).27,106

Venous Thromboembolism

Another condition affecting the extremities is venous thrombophlebitis or venous thromboembolism (VTE), a common complication seen in clients with cancer or following abdominal or pelvic surgery (especially orthopedic surgery such as total hip and total knee replacements), major trauma, or prolonged immobilization. Other risk factors are discussed in Chapter 6.

VTE is an inflammation of a vein associated with thrombus formation affecting superficial or deep veins of the extremities. Superficial vein thrombophlebitis typically involves the veins of the upper extremities (usually unilateral) and is most commonly associated with trauma (e.g., insertion of IV lines and catheters in the subclavian vein). In fact, the presence of an indwelling central venous catheter (often present in cancer patients) is the strongest predictor of upper extremity deep vein thrombosis (DVT).108 DVT usually involves the deep veins of the legs, primarily the calf.

DVTs can become dislodged and travel as an embolus where it can become lodged in the pulmonary artery, leading to comorbidity or even death from acute coronary syndrome and stroke. DVTs are often asymptomatic, making screening a key component in the prevention of this potentially life-threatening problem.109

Many clinicians use Homans’ sign as physical evidence of DVTs. The test uses slow dorsiflexion of the foot or gentle squeezing of the affected calf to elicit deep calf pain. Homans’ sign is not specific for DVT because a positive Homans’ sign is possible with Achilles tendinitis and muscle injury of the gastrocnemius and plantar muscle.

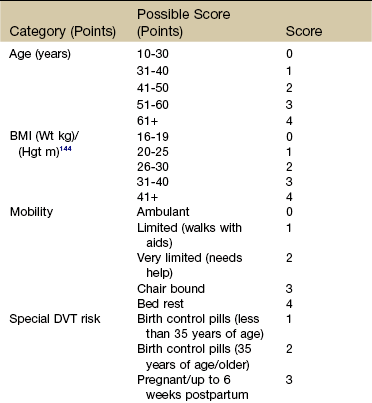

Autar DVT Risk Assessment Scale (Table 4-11) is a much more sensitive and specific test developed as a predictive index of DVT. Seven risk categories are included: increasing age, build and BMI, immobility, special DVT risk, trauma, surgery, and high-risk disease.110,111

TABLE 4-11

Autar Deep Vein Thrombosis Scale

BMI, Body mass index; see text for web links for easy calculation; MI, myocardial infarction; DVT, deep venous thrombosis; CVA, cerebrovascular accident.

From Autar R: Nursing assessment of clients at risk of deep vein thrombosis (DVT): the Autar DVT scale, J Advanced Nursing 23(4): 763-770, 1996. Reprinted with permission of Blackwell Scientific.

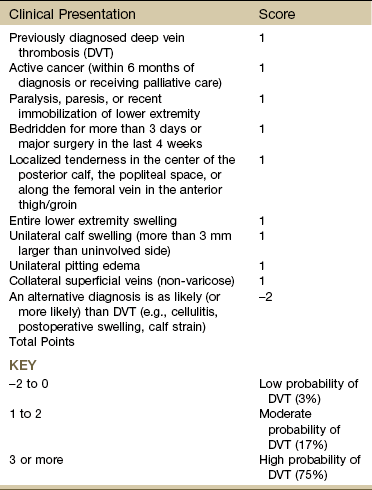

A similar (less comprehensive) tool, the Wells’ Clinical Decision Rule (CDR),112-114 frequently discussed in the general medical literature, can also be used by therapists (Table 4-12).115 The CDR incorporates signs, symptoms, and risk factors for DVT and should be used in all cases of suspected DVT. A simple model to predict upper extremity DVT has also been proposed and remains under investigation.108

TABLE 4-12

Wells’ Clinical Decision Rule for Deep Vein Thrombosis

Medical consultation is advised in the presence of low probability; medical referral is required with moderate or high score.

From Wells PS, Anderson DR, Bormanis J, et al: Value of assessment of pretest probability of deep-vein thrombosis in clinical management, Lancet 350:1795-1798, 1997. Used with permission.

The CDR is used more widely in the clinic, but the Autar scale is more comprehensive and incorporates BMI, postpartum status, and the use of oral contraceptives as potential risk factors.

Research shows some physical therapists may not be referring clients to a physician for additional workup when the individual’s risk for developing DVT warrants referral.116 Medical consultation is advised for anyone with a low probability of DVT; medical referral is required for any individual suspected of having DVT.

The Chest and Back (Thorax)

A screening examination of the thorax requires the same basic techniques of inspection, palpation, and auscultation. Once again, keep in mind this is a screening examination. Being familiar with normal findings of the chest and thorax will help the therapist identify abnormal results requiring further evaluation or referral. Only basic screening tools are included. Specialized training may be required for some acute care or primary care settings.

Chest and Back: Inspection35

Clinical inspection of the chest and back encompasses both the cardiac and pulmonary systems, but some of the most obvious changes are observed in relation to the respiratory system (Box 4-17). Inspect the client while he or she is sitting upright without support if possible. Observe the client’s thorax from the front, back, side, and over the shoulder (looking down over the anterior chest). Note any skin changes, signs of skin breakdown, and signs of cyanosis or pallor, scars, wounds, bruises, lesions, nodules, or superficial venous patterns.

Note the shape and symmetry of the thorax from the front and back. Note any obvious anatomic changes or deformities (e.g., pectus excavatum, pectus carinatum, barrel chest). Observe posture and spinal alignment. Record the presence of any deviations from normal (e.g., forward head, rounded shoulders, upward angle of clavicles, rib alignment) or deformities (e.g., kyphosis, scoliosis, rib hump) that can compromise chest wall excursion. Estimate the anterior-posterior diameter compared to the transverse diameter.

A normal ratio of 1 : 2 may be replaced by an equal diameter (1 : 1 ratio) typical of the barrel chest that develops as a result of hyperinflation. Look at the angle of the costal margins at the xiphoid process; for example, anything less than a 90-degree alignment may be indicative of a barrel chest. Observe (and palpate) for equal intercostal spaces and compare sides (right to left). Observe the client for muscular development and nutritional status by noting the presence of underlying adipose tissue and the visibility of the ribs.

Assess respiratory rate, depth, and rhythm or pattern of breathing while the client is breathing normally. A description of altered breathing patterns can be found in Chapter 7. Watch for symmetry of chest wall movement, costal versus abdominal breathing, the use of accessory muscles, and bulging or retraction of the intercostal spaces. Remember, the normal ratio of inspiration to expiration is 1 : 2.

Chest and Back: Palpation

Palpation of the thorax is usually combined with inspection to save time. Breast examination and lymph node assessment may be part of the screening exam of the chest in males and females (see discussion later in this section).

Palpation can reveal skin changes and alert the therapist to conditions that relate to the client’s respiratory status. Look for crepitus, a crackly, crinkly sensation in the subcutaneous tissue. Feel for vibrations during inspiration as described next.

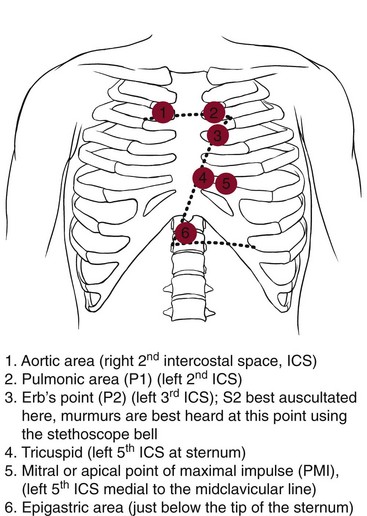

Palpate the entire thorax (anterior and posterior) for tactile fremitus by placing the palms of both hands (examiner’s) over the client’s upper anterior chest at the second intercostal space (Fig. 4-46). The normal response is a feeling of vibrations of equal intensity during vocalizations on either side of the midline, front to back.

Fig. 4-46 Palpating for tactile fremitus. Place the palmar surfaces of both hands on the client’s chest at the second intercostal space. Ask the client to say “99” repeatedly as you gradually move your hands over the chest, systematically comparing the lung fields. Start at the center and move out toward the arms. Drop the hands down one level and move back toward the center. Continue until the complete lung fields have been assessed. Repeat the exam on the client’s back. The normal response is a feeling of vibrations of equal intensity during vocalizations on either side of the midline, front to back. (From Expert 10-minute physical examinations, St. Louis, 1997, Mosby.)

Tactile fremitus is found most commonly in the upper chest near the bronchi around the second intercostal space. Stronger vibrations are felt whenever air is present; the absence of air such as occurs with atelectasis is marked by an absence of vibrations. Fluid outside the lung pressing on the lung increases the force of vibration.

Fremitus can be increased or decreased—increased over areas of compression because the dense tissue improves transmission of the vibrational wave while being decreased over areas of effusion (decreased density, decreased vibration).

Increased tactile fremitus often accompanies inflammation, infection, congestion, or consolidation of a lung or part of a lung. Diminished tactile fremitus may indicate the presence of pleural effusion or pneumothorax.35 Record the location and beginning and ending points, and note whether the tactile fremitus is increased or decreased. Confirm all findings with auscultation; a medical evaluation with chest x-ray provides the differential diagnosis.

Assess respiratory excursion and symmetry with the client in the sitting position (preferred) or if unable to assume or maintain an upright position, then in the supine position. The upright position makes it easier to assess all areas of respiratory excursion: upper, middle, and lower. Stand in front of your client and place your thumbs along the client’s costal margins wrapping your fingers around the rib cage. Observe how far the thumbs move apart (range and symmetry) during chest expansion (normal breathing and deep breathing). Normal respiratory excursion will separate the thumbs by  to 2 inches. Assess respiratory excursion at more than one level, front to back.

to 2 inches. Assess respiratory excursion at more than one level, front to back.

The presence of costovertebral tenderness should be followed up with Murphy’s percussion test (see Fig. 4-54). Bone tenderness over the lumbar spinous processes is a red-flag symptom for osseous disorders, such as fracture, infection, or neoplasm, and requires a more complete evaluation.

Chest and Back: Percussion

Chest and back percussion is an important part of the screening exam. The clinician can use percussion of the chest and back to identify the left ventricular border of the heart and the depth of diaphragmatic excursion in the upper abdomen during breathing. Percussion can also help identify disorders that impair lung ventilation such as stomach distention, hemothorax, lung consolidation, and pneumothorax.35

Dullness over the lungs during percussion may indicate a mass or consolidation (e.g., pneumonia). Hyperresonance over the lungs may indicate hyperinflated or emphysemic lungs. Decreased diaphragmatic excursion on one side occurs with pleural effusion, diaphragmatic (phrenic nerve) paralysis, tension pneumothorax, stomach distention (left side), hepatomegaly (right side), or atelectasis. Clients with COPD often have decreased excursion bilaterally as a result of a hyperinflated chest depressing the diaphragm.

Chest and Back: Lung Auscultation

In a screening exam, the therapist should listen for normal breath sounds and air movement through the lungs during inspiration and expiration. Taking a deep breath or coughing clears some sounds. At times the examiner instructs the client to take a deep breath or cough and listens again for any changes in sound. With practice and training, the therapist can identify the most common abnormal sounds heard in clients with pulmonary involvement: crackles, wheezing, and pleural friction rub.

Crackles (formerly called rales) are the sound of air moving through an airway filled with fluid. It is heard most often on inspiration and sounds like strands of hair being rubbed together under a stethoscope. Crackles/rales are normal sounds in the morning as the alveolar spaces open up. Have the client take a deep breath to complete this process first before listening.

Abnormal crackles can be heard during exhalation in clients with pneumonia or CHF and during inhalation with the re-expansion of atelectatic areas. Crackles are described as fine (soft and high pitched), medium (louder and low pitched), or coarse (moist and more explosive).

Wheezing is the sound of air passing through a narrowed airway blocked by mucus secretions and usually occurs during expiration (wheezing on inspiration is a sign of a more serious problem). It is frequently described as a high-pitched, musical whistling sound but there are different tones to wheezing that can be identified in making the medical differential diagnosis.

There is some debate about the difference between rhonchi and wheezing. Some experts consider the low-pitched, rattling sound of rhonchi (similar to snoring) as a form of wheezing. Whether called wheezing or rhonchi, this sound is most often associated with asthma or emphysema. Take careful note when the wheezing goes away in any client who presents with wheezing. Disappearance of wheezing occurs when the person is not breathing.

Rhonchi is defined as air moving through thick secretions partially obstructing airflow and is almost always associated with bronchitis. These loud, low-pitched rumbling sounds can be heard on inspiration or expiration and may be cleared by coughing.

Pleural friction rub makes a high-pitched scratchy sound heard when a hand is cupped over the ear and scratched along the outside of the hand. It is caused by inflamed pleural surfaces and can be heard on inspiration and/or expiration. The pleural linings should move over each other smoothly and easily. In the presence of inflammation (pleuritis, pleurisy, pneumonia, tumors), the inflamed tissue (parietal pleura) is rubbing against other inflamed, irritated tissue (visceral pleura) causing friction.

Assess for egophony by asking the client to say and repeat the “ee” sound during auscultation of the lung fields. The “aa” sound heard as the client says the “ee” sound indicates pleural effusion or lung consolidation. Bronchophony, a clear and audible “99” sound suggests the sound is traveling through fluid or a mass; the sound should be muffled in the healthy adult. Finally, assess for consolidation using whispered pectoriloquy. Ask the client to whisper “1-2-3” as you listen to the chest and back. The examiner should hear a muffled noise (normal) instead of a clear and audible “1-2-3” (consolidation).

Describe sounds heard, the location of the sounds on the thorax, and when the sounds are heard during the respiratory cycle (inspiration versus expiration). Have the client gently cough (bronchial secretions causing a “gurgle” will often clear with a cough) and listen again. Compare results with the first exam (and with the baseline if available). The decision to treat, treat and consult/refer, or consult/refer a client for further evaluation is based on history, clinical findings, client distress, vital signs, and any associated signs and symptoms observed or reported.

Giving the physician details of your physical exam findings is important in order to give a clear idea of the reason for the consult and urgency (if there is one). Sometimes, abnormal findings are “normal” for people with chronic pulmonary problems. For example, always evaluate apparent abnormal breath (and heart) sounds in order to recognize change that is significant for the individual. The physician is more likely to respond immediately when told that the therapist identified crackles in the right lower lung and the client is producing yellow sputum than if the report is “client has altered sounds on auscultation.”

Chest and Back: Heart Auscultation

The same general principles for auscultation of lung sounds apply to auscultation of heart sounds. The therapist’s primary responsibility in a screening examination is to know what “normal” heart sounds are like and report any changes (absence of normal sounds or presence of additional sounds).

The normal cardiac cycle correlates with the direction of blood flow and consists of two phases: systole (ventricles contract and eject blood) and diastole (ventricles relax and atria contract to move blood into the ventricles and fill the coronary arteries).

Normal heart sounds (S1 and S2) occur in relation to the cardiac cycle. Just before S1, the mitral and tricuspid (AV) valves are open, and blood from the atria is filling the relaxed ventricles (see Fig. 6-1). The ventricles contract and raise pressure, beginning the period called systole.

Pressure in the ventricles increases rapidly, forcing the mitral and tricuspid valves to close causing the first heart sound (S1). The S1 sound produced by the closing of the AV valves is lubb; it can be heard at the same time the radial or carotid pulse is felt.

As the pressure inside the ventricles increases, the aortic and pulmonic valves open and blood is pumped out of the heart into the lungs and aorta. The ventricle ejects most of its blood and pressure begins to fall causing the aortic and pulmonic valves to snap shut. The closing of these valves produces the dubb (S2) sound. This marks the beginning of the diastole phase.

S3 (third heart sound), S4 (fourth heart sound), heart murmurs, and pericardial friction rub are the most common extra sounds heard. S3, also known as a ventricular gallop, is a faint, low-pitched lubb-dup-ah sound heard directly after S2. It occurs at the beginning of diastole and may be heard in healthy children and young adults as a result of a large volume of blood pumping through a small heart. This sound is also considered normal in the last trimester of pregnancy. It is not normal when it occurs as a result of anemia, decreased myocardial contractility, or volume overload associated with CHF.

S4, also known as an atrial gallop, occurs in late diastole (just before S1) if there is a vibration of the valves, papillary muscles, or ventricular walls from resistance to filling (stiffness). It is usually considered an abnormal sound (ta-lup-dubb) but may be heard in athletes with well-developed heart muscles.

Heart murmurs are swishing sounds made as blood flows across a stiff or incompetent (leaky) valve or through an abnormal opening in the heart wall. Most murmurs are associated with valve disease (stenosis, insufficiency), but they can occur with a wide variety of other cardiac conditions. They may be normal in children and during the third trimester of pregnancy.

A pericardial friction rub associated with pericarditis is a scratchy, scraping sound that is heard louder during exhalation and forward bending. The sound occurs when inflamed layers of the heart viscera (see Fig. 6-5) rub against each other causing friction.

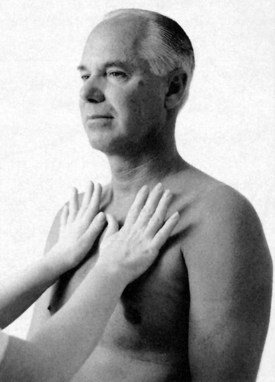

Auscultate the heart over each of the six anatomic landmarks (Fig. 4-47), first with the diaphragm (firm pressure) and then with the bell (light pressure) of the stethoscope. Use a Z-path to include all landmarks while covering the entire surface area of the heart.

Fig. 4-47 Auscultation of cardiac areas using cardiac anatomic landmarks. Inspect and palpate the anterior chest with the client first sitting up then lying down supine. Ask the individual to breathe quietly while you auscultate all six anatomic landmarks shown.

Practice at each site until you can hear the rate and rhythm, S1 and S2, extra heart sounds, including murmurs. The high-pitched sounds of S1 and S2 are heard best with the stethoscope diaphragm. Murmurs are not heard with a bell (listen for murmurs with the diaphragm); low-pitched sounds of S3 and S4 are heard with the bell.

As with lung sounds, describe heart sounds heard, rate and rhythm of the sounds, the location of the sounds on the thorax, and when the sounds are heard during the cardiac cycle. The decision to refer a client for further evaluation is based on history, age, risk factors, presence of pregnancy, clinical findings, client distress, vital signs, and any associated signs and symptoms observed or reported.

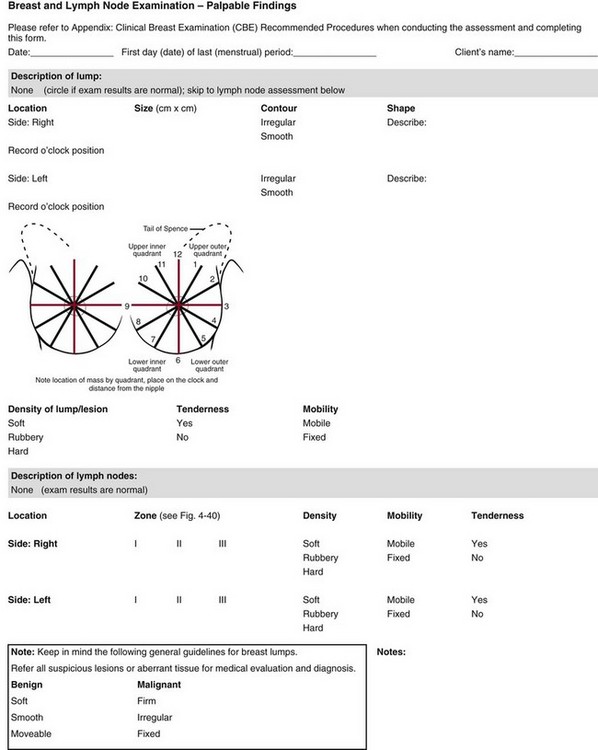

Chest: Clinical Breast Examination

Although the third edition of this text specifically said, “breast examination is not within the scope of a physical therapist’s practice,” this practice is changing.

As the number of cancer survivors increases in the United States, therapists treating postmastectomy women and clients of both genders with lymphedema are on the rise. Cancer recurrence after mastectomy with or without reconstruction is possible. Recurrences after reconstructive surgery have been detected first on physical examination.117-119

With direct and unrestricted access of consumers to physical therapists in many states and with the expanded role of physical therapists in primary care, advanced skills have become necessary. For some clients, clinical breast exam (CBE) is an appropriate assessment tool in the screening process.120

CBE and the Guide

The Guide includes a concise description of the physical therapist in primary care and our respective roles in primary and secondary prevention.18 Currently, the Guide does not specifically include nor exclude examination of breast tissue but does include examination of the integument.

The Guide does not discriminate what parts of the body may, or may not, be examined as a part of professional practice. The section on examination of the integumentary system identifies the need to perform visual and palpatory inspection of the skin for abnormalities.

It is recognized that the Guide is a guide to practice that is intended to be revised periodically to reflect current physical therapy practice. Determining whether CBE should be included or excluded from the scope of a physical therapist’s practice is the responsibility of each individual state.

If the therapist receives proper training to perform CBEs,* he or she must make sure this examination is allowed according to the state practice act for the state(s) in which the therapist is conducting CBEs. In some states, it is allowed by exclusion, meaning it is not mentioned and therefore included. When moving to a new state, the therapist is advised to take the time to review and understand that state’s practice act.

An introductory course to breast cancer and CBE for the physical therapist is available. Charlie McGarvey, PT, MS, and Catherine Goodman, MBA, PT, present the course in various sites around the United States and upon request.

A certified training program is also available through MammaCare Specialist. The program is offered to health care professionals at training centers in the United States. The course teaches proficient breast examination skills. For more information, contact: http://www.mammacare.com/professional_training.htm.

Screening for Early Detection of Breast Cancer: The goal of screening examinations is early detection of breast cancer. Breast cancers that are detected because they are causing symptoms tend to be relatively larger and are more likely to have spread beyond the breast. In contrast, breast cancers found during screening examinations are more likely to be small and still confined to the breast.

The size of a breast neoplasm and how far it has spread are the most important factors in predicting the prognosis for anyone with this disease. According to the American Cancer Society (ACS) early detection tests for breast cancer saves many thousands of lives each year; many more lives could be saved if health care providers took advantage of these tests. Following the ACS’s guidelines for the early detection of breast cancer improves the chances that breast cancer can be diagnosed at an early stage and treated successfully.121,122

CBE detects a small portion of cancers (4.6% to 5.9%) not found by mammography.123 It may be important for women who do not receive regular mammograms, either because mammography is not recommended (e.g., women aged 40 and younger) or because some women do not receive screening mammography as recommended.124

ACS guidelines for CBE recommend CBE every 3 years for women ages 20 to 39 (more often if there are risk factors; see Table 17-3). An annual CBE is advised every year for asymptomatic women ages 40 and older. Men can develop breast cancer, but this disease is about 100 times more common among women than men.122

Breast self-examination (BSE) is an option for women starting at age 20. Women should be educated about the benefits and limitations of the BSE. Regular BSE is one way for women to know how their breasts normally feel and to notice any changes. Advise all women during the client education portion of the physical therapy intervention to report any breast changes right away. The primary care provider should also review each client’s method of performing a BSE (see Appendix D-6).

It has been generally accepted that mammography screening reduces the risk of death from breast cancer (except, perhaps, among younger women, for whom the benefit of mammography is controversial), and that this risk reduction is achieved through the detection of malignancy at an earlier stage, when treatment is more efficacious.125 More recently, the role of mammography in lowering breast cancer–related mortality has come under closer scrutiny.126,127

The ideal interval between screening mammography remains under investigation. In the United States, the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force recommends screening every 1 to 2 years while the ACS recommends annual screening from age 40 years. In Europe, most countries focus on women aged 50 years and older and recommend screening every 2 years.128

Mammograms do not identify all breast cancers; for this reason, a thorough CBE remains an essential part of breast screening to complement mammograms and reduce false-negative results.129,130

“Thorough” is defined as palpation of the area from the collarbone to the bottom of the rib cage, one dime-size area at a time, at three levels of pressure from just below the skin, down to the mid-breast, and up against the chest wall. A thorough CBE by a specially trained practitioner should take at least five minutes per breast.121

It has been shown both in the laboratory and in the clinic that properly trained fingers can detect breast lesions as small as 3 mm in diameter.131,132 As experts in the assessment and palpation of the integumentary and musculoskeletal systems, physical therapists are highly qualified professionals to receive this type of training.

Physical Therapist’s Role in Screening for Breast Cancer: Historically the upper quadrant screening examination conducted by physical therapists has not included CBE. Procedures have been confined to questions posed to clients during the interview regarding past medical history (e.g., cancer, lactation, abscess, mastitis) and questions to identify the possibility of breast pathology as the underlying cause for back or shoulder pain and/or other symptoms.120

As health care specialists with advanced observational and palpatory skills, physical therapists can play an important role in the identification of aberrant soft tissue lesions requiring further medical evaluation. Physical therapists are professionally trained experts in tissue integrity and possess highly developed skills in the detection of various types of abnormalities. Properly trained physical therapists should be considered “qualified health care specialists” as defined by the ACS in the provision of cancer screening when the history, clinical presentation, and associated signs and symptoms point to the need for CBE.120

A physical therapist conducting a CBE could miss a lump (false negative finding) and not send the client for medical evaluation. However, this will most certainly occur if the therapist is not conducting a CBE to assess the integrity of the skin and soft tissues of the breast or axilla. Conversely, a physical therapist finding a lump or abnormality on CBE would refer the client to a physician for examination.120

A blueprint for the screening assessment is provided in Box 4-18 and Fig. 4-48. Standardized CBE and reporting of results has not been established. Best practice for CBE using inspection and palpation based on current recommendations124,133 is presented in Appendix D-7. For a discussion of benign breast diseases and breast conditions that can refer pain to the shoulder, neck, or chest, see Chapter 17.

When a suspicious mass is found during examination, it must be medically evaluated, even if the client reports a recent mammography was “normal.”124 Clinical signs and symptoms of breast disease are listed in Chapter 17. More in-depth discussion of the role of the physical therapist in primary care and cancer screening as it relates to integrating CBE into an upper quarter examination is available.120

Abdomen

Anyone presenting with primary pain patterns from pathology of the abdominal organs will likely see a physician rather than a physical therapist. For this reason, abdominal and visceral assessment is not generally part of the physical therapy evaluation. When the therapist suspects referred pain from the viscera to the musculoskeletal system, this type of assessment can be helpful in the screening examination.

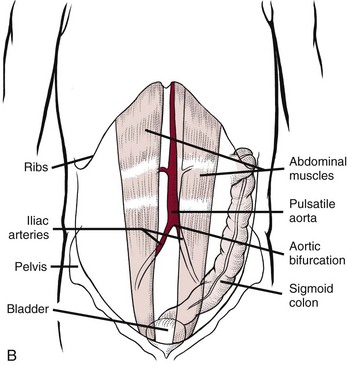

Abdomen: Inspection

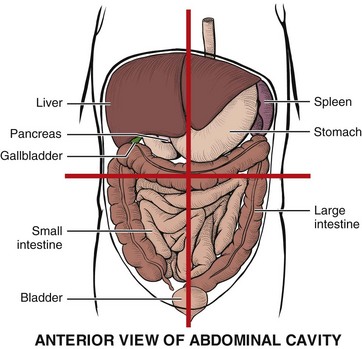

From a screening or assessment point of view, the abdomen is divided into four quadrants centered on the umbilicus (as shown in Figs. 4-49 and 4-50). During the inspection, any abdominal scars (and associated history) should be identified (see Fig. 4-8).

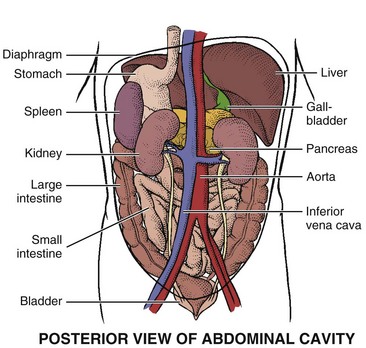

Fig. 4-49 Four abdominal (anterior) quadrants formed by two imaginary perpendicular lines running through the umbilicus. As a general rule, viscera in the right upper quadrant (RUQ) can refer pain to the right shoulder; viscera in the left upper quadrant (LUQ) can refer pain to the left shoulder; viscera in the lower quadrants are less specific and can refer pain to the pelvis, pelvic floor, groin, low back, hip, and sacroiliac/sacral areas (see also Figs. 3-4 and 3-5).

Fig. 4-50 Posterior view of the abdomen. The abdominal aorta passes from the diaphragm through the abdominal cavity, just to the left of the midline. It branches into the left and right common iliac arteries at the level of the umbilicus. Retroperitoneal bleeding from any of the posterior elements (e.g., stomach, spleen, aorta, kidneys) can cause back, hip, and/or shoulder pain.

Note the color of the skin and the presence and location of any scars, striae from pregnancy or weight gain/loss, petechiae, or spider angiomas (see Fig. 9-3). A bluish discoloration around the umbilicus (Cullen’s sign) or along the lower abdomen and flanks (Grey Turner’s sign) may be the sign of a retroperitoneal bleed (e.g., pancreatitis, ruptured ectopic pregnancy, posterior perforated ulcer). The color may be a shade of blue-red, blue-purple, or green-brown, depending on the stage of hemoglobin breakdown.35

From a seated position next to the client, note the contour of the abdomen and look for any asymmetry. Repeat the same visual inspection while standing behind the client’s head. Generalized distention can accompany gas, whereas local bulges may occur with a distended bladder or hernia. Make note if the umbilicus is displaced in any direction or if there are any masses, pulsations, or movements of the abdomen. Visible peristaltic waves are not normal and may signal a GI problem. Document the presence of ascites (see Fig. 9-8).

Clients with an organic cause for abdominal pain usually are not hungry. Ask the client to point to the location of the pain. Pain corresponding to the epigastric, periumbilical, and lower midabdominal regions is shown in Fig. 8-2. If the finger points to the navel, but the client seems well and is not in any distress, there may be a psychogenic source of symptoms.134

Abdomen: Auscultation

In a screening examination, the therapist may auscultate the four abdominal quadrants for the presence of abdominal sounds. Expect to hear clicks, rumblings, and gurgling sounds every few seconds throughout the abdomen. Auscultation should occur before palpation and/or percussion to avoid altering bowel sounds.

The absence of sounds or very few sounds in any or all of the quadrants is a red flag and is most common in the older adult with multiple risk factors such as recent abdominal, back, or pelvic surgery and the use of narcotics or other medications.

As previously mentioned the therapist may auscultate the abdomen for vascular sounds (e.g., bruits) when the history (e.g., age over 65, history of coronary artery disease), clinical presentation (e.g., neck, back, abdominal, or flank pain), and associated signs and symptoms (e.g., syncopal episodes, signs and symptoms of PVD) warrant this type of assessment.

Listen for pulsations/bruits over the aorta, renal arteries, iliac arteries, and femoral arteries first and remember to do so before palpation because palpation may stir up the bowel contents and increase peristalsis, making auscultation more difficult.

Abdomen: Percussion and Palpation

Remember to auscultate first before percussion and palpation in order to avoid altering the frequency of bowel sounds. Percussion over normal, healthy abdominal organs is an advanced skill even among doctors and nurses and is not usually an integral part of the physical therapy screening examination.

Palpation (light and deep) of all four abdominal quadrants is a separate skill used to assess for temperature changes, tenderness, and large masses. Keep in mind that even a skilled clinician will not be able to palpate abdominal organs in an obese person.

Most viscera in the normal adult are not palpable unless enlarged. Anatomical structures can be mistaken for an abdominal mass. Palpation is contraindicated in anyone with a suspected abdominal aortic aneurysm, appendicitis, or a known kidney disease, or who has had an abdominal organ transplantation.

When palpation is carried out, always explain to your client what test you are going to perform and why. Make sure the person being examined has an empty bladder. Examine any painful areas last. Use proper draping and warm your hands. Have the client bend the knees with the feet flat on the exam table to put the abdominal muscles in a relaxed position. During palpation, if the person is ticklish or tense, place his or her hand on top of your palpating hand. Ask him or her to breathe in and out slowly and regularly. The tickle response disappears in the presence of a truly acute abdomen.135 To help distinguish between voluntary abdominal muscle guarding and involuntary abdominal rigidity, have the client exhale or breathe through the mouth. Voluntary guarding usually decreases using these techniques.

Start with a light touch, moving the fingers in a circular motion, slowly and gently. If the abdominal muscles are contracted, observe the client as he or she breathes in and out. The contraction is voluntary if the muscles are more strongly contracted during inspiration and less strong during expiration. Muscles firmly contracted throughout the respiratory cycle (inspiration and expiration) are more likely to be involuntary, possibly indicating an underlying abdominal problem. To check for rebound tenderness, the “pinch-an-inch” test is preferred over the Rebound Tenderness (Blumberg’s sign) (see Figs. 8-10 to 8-12).

A variation on the Blumberg sign (for peritonitis) is the Rovsing sign (suggesting appendicitis). Rovsing sign is elicited by pushing on the abdomen in the left lower quadrant (away from the appendix as in most people the appendix is in the right lower quadrant). While this maneuver stretches the entire peritoneal lining, it only causes pain in any location where the peritoneum is irritating the muscle. In the case of appendicitis, the pain is felt in the right lower quadrant despite pressure being placed elsewhere.

If left lower quadrant pressure by the examiner leads only to left-sided pain or pain on both the left and right sides, then there may be some other pathologic etiology (e.g., bladder, uterus, ascending [right] colon, fallopian tubes, ovaries, or other structures).

Liver: Liver percussion to determine its size and identify its edges is a skill beyond the scope of a physical therapist for a screening examination. Therapists involved in visceral manipulation will be most likely to develop this advanced skill.

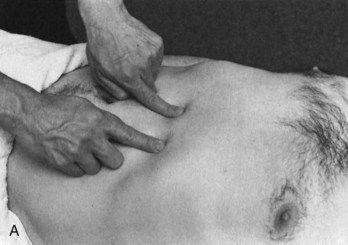

To palpate the liver (Fig. 4-51), have the client take a deep breath as you feel deeply beneath the costal margin. During inspiration, the liver will move down with the diaphragm so that the lower edge may be felt below the right costal margin.

Fig. 4-51 Palpating the liver. Place your left hand under the client’s right posterior thorax (as shown) parallel to and at the level of the last two ribs. Place your right hand on the client’s RUQ over the midclavicular line. The fingers should be pointing toward the client’s head and positioned below the lower edge of liver dullness (previously mapped out by percussion). Ask the client to take a deep breath while pressing inward and upward with the fingers of the right hand. Attempt to feel the inferior edge of the liver with your right hand as it descends below the last rib anteriorly.

A normal adult liver is not usually palpable and palpation is not painful. Cirrhosis, metastatic cancer, infiltrative leukemia, right-sided CHF, and third-stage (tertiary) syphilis can cause an enlarged liver. The liver in clients with COPD is more readily palpable as the diaphragm moves down and pushes the liver below the ribs. The liver is often palpable 2 to 3 cm below the costal margin in infants and young children.

If you come in contact with the bottom edge tucked up under the rib cage, the normal liver will feel firm, smooth, even, and rubbery. A palpable hard or lumpy edge warrants further investigation. Some clinicians prefer to stand next to the client near his head, facing his feet. As the client breathes in, curl the fingers over the costal margin and up under the ribs to feel the liver (Fig. 4-52).

Fig. 4-52 An alternate way to palpate the liver. Hook the fingers of one or both hands (depending on hand size) up and under the right costal border. As the client breathes in, the liver descends and the therapist may come in contact with the lower border of the liver. If this procedure elicits exquisite tenderness, it may be a positive Murphy’s sign for acute cholecystitis (not the same as Murphy’s percussion test [costovertebral tenderness] of the kidney depicted in Fig. 4-54).

Spleen: As with other organs, the spleen is difficult to percuss, even more so than the liver, and is not part of a screening examination.

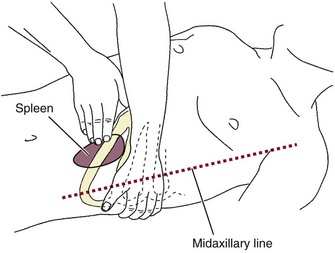

Palpation of the spleen is not possible unless it is distended and bulging below the left costal margin (Fig. 4-53). The spleen enlarges with mononucleosis and trauma. Do not continue to palpate an enlarged spleen because it can rupture easily. Report to the physician immediately how far it extends below the left costal margin and request medical evaluation.

Fig. 4-53 Palpation of the spleen. The spleen is not usually palpable unless it is distended and bulging below the left costal margin. Left shoulder pain can occur with referred pain from the spleen. Stand on the person’s right side and reach across the client with the left hand, placing it beneath the client over the left costovertebral angle. Lift the spleen anteriorly toward the abdominal wall. Place the right hand on the abdomen below left costal margin. Using findings from percussion, gently press fingertips inward toward the spleen while asking the client to take a deep breath. Feel for spleen as it moves downward toward the fingers. (From Leasia MS, Monahan FD: A practical guide to health assessment, ed 2, Philadelphia, 2002, WB Saunders.)

Gallbladder and Pancreas: Likewise, the gallbladder tucked up under the liver (see Figs. 9-1 and 9-2) is not palpable unless grossly distended. To palpate the gallbladder, ask the person to take a deep breath as you palpate deep below the liver margin. Only an abnormally enlarged gallbladder can be palpated this way.

The pancreas is also inaccessible; it lies behind and beneath the stomach with its head along the curve of the duodenum and its tip almost touching the spleen (see Fig. 9-1). A round, fixed swelling above the umbilicus that does not move with inspiration may be a sign of acute pancreatitis or cancer in a thin person.

Kidneys: The kidneys are located deep in the retroperitoneal space in both upper quadrants of the abdomen. Each kidney extends from approximately T12 to L3. The right kidney is usually slightly lower than the left.

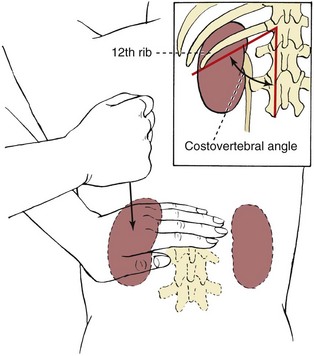

Percussion of the kidney is accomplished using Murphy’s percussion test (Fig. 4-54). Although this test is commonly performed, its diagnostic value has never been validated. Results of at least one Finnish study136 suggested that in acute renal colic loin tenderness and hematuria (blood in the urine) are more significant signs than renal tenderness.137 A diagnostic score incorporating independent variables, including results of urinalysis, presence of costovertebral angle tenderness and renal tenderness, as well as duration of pain, appetite level, and sex (male versus female), reached a sensitivity of 0.89 in detecting acute renal colic, with a specificity of 0.99 and an efficiency of 0.99.136

Fig. 4-54 Murphy’s percussion also known as the test for costovertebral tenderness. Murphy’s percussion is used to rule out involvement of the kidney and assess for pseudorenal pain (see discussion, Chapter 10). Indirect fist percussion causes the kidney to vibrate. To assess the kidney, position the client prone or sitting and place one hand over the rib at the costovertebral angle on the back. Give the hand a percussive thump with the ulnar edge of your other fist. The person normally feels a thud but no pain. Reproduction of back and/or flank pain with this test is a red-flag sign for renal involvement (e.g., kidney infection or inflammation). (From Black JM, Matassarin-Jacobs E, editors: Luckmann and Sorensen’s medical-surgical nursing, ed 4, Philadelphia, 1993, WB Saunders.)

To palpate the kidney, stand on the right side of the supine client. Place your left hand beneath the client’s right flank. Flex the left metacarpophalangeal joints (MCPs) in the renal angle while pressing downward with the right hand against the right outer edge of the abdomen. This method compresses the kidney between your hands. The left kidney is usually not palpable because of its position beneath the bowel.

Kidney transplants are often located in the abdomen. The therapist should not percuss or palpate the kidneys of anyone with chronic renal disease or organ transplantation.

Bladder: The bladder lies below the symphysis pubis and is not palpable unless it becomes distended and rises above the pubic bone. Primary pain patterns for the bladder are shown in Fig. 10-9. Sharp pain over the bladder or just above the symphysis pubis can also be caused by abdominal gas. The presence of associated GI signs and symptoms and lack of urinary tract signs and symptoms may be helpful in identifying this pain pattern.

Aortic Bifurcation: It may be necessary to assess for an abdominal aneurysm, especially in the older client with back pain and/or who reports a pulsing or pounding sensation in the abdomen during increased activity or while in the supine position.

The ease with which the aortic pulsations can be felt varies greatly with the thickness of the abdominal wall and the anteroposterior diameter of the abdomen. To palpate the aortic pulse, the therapist should press firmly deep in the upper abdomen (slightly to the left of the midline) to find the aortic pulsations (Fig. 4-55, A).

Fig. 4-55 A, Place one hand or one finger on either side of the aorta as shown here. Press firmly deep in the upper abdomen just to the left of the midline. You may feel aortic pulsations. These pulsations are easier to appreciate in a thin person and more difficult to feel in someone with a thick abdominal wall or large anteroposterior diameter of the abdomen. Obesity and abdominal ascites or distention makes this more difficult. Use the stethoscope (bell) to listen for bruits. Bruits are abnormal blowing or swishing sounds heard on auscultation of the arteries. Bruits with both systolic and diastolic components suggest the turbulent blood flow of partial arterial occlusion. If the renal artery is occluded as well, the client will be hypertensive. B, Visualize the location of the aorta slightly to the left of midline and its bifurcation just below the umbilicus. See text (this chapter and Chapter 6) for discussion of normal and average pulse widths. The pulse width expands at the aortic bifurcation (again, usually just below the umbilicus). An aneurysm can occur anywhere along the aorta; 95% of all abdominal aortic aneurysms occur just below the renal arteries. (A from Boissonnault WG, editor: Examination in physical therapy practice, ed 2, New York, 1995, Churchill Livingstone.)

The therapist can assess the width of the aorta by using both hands (one on each side of the aorta) and pressing deeply. The examiner’s fingers along the outer margins of the aorta should remain the same distance apart until the aortic bifurcation. Where the aorta bifurcates (usually near the umbilicus), the width of the pulse should expand (Fig. 4-55, B). The normal aortic pulse width is between 2.5 and 4.0 cm (some sources say the width must be no more than 3.0 cm; others list 4.0 cm). Average pulse width is 2.5 cm or about 1.2 inches wide.138,139 See Chapter 6 for a more in-depth discussion of aortic pulse width norms.

Throbbing pain that increases with exertion and is accompanied by a sensation of a heart beat when lying down and of a palpable pulsating abdominal mass requires immediate medical attention. Remember, the presence of an abdominal bruit accompanied by risk factors for an aortic aneurysm may be a contraindication to abdominal palpation.

Systems Review … or … Review of Systems?

When a physician conducts a systems review, the examination is a routine physical assessment of each system, starting with ear, nose, and throat (ENT), followed by chest auscultation for pulmonary and cardiac function, palpation of lymph nodes, and so on.

The therapist does not conduct a systems review such as the medical doctor performs. The Guide uses the terminology “Systems Review” to describe a brief or limited exam of the anatomic and physiologic status of the cardiovascular/pulmonary, integumentary, musculoskeletal, and neuromuscular systems.

As part of this Systems Review, the client’s ability to communicate and process information is identified as well as any learning barriers such as hearing or vision impairment, illiteracy, or English as a second language (see the Guide, pp. 713/s705).

A more appropriate term for what the therapist does in the screening process may be a “Review of Systems.” In the screening examination as presented in this text, after conducting an interview and assessment of pain type/pain patterns, the therapist may conduct a review of systems (ROS) first by looking for any characteristics of systemic disease in the history or clinical presentation.

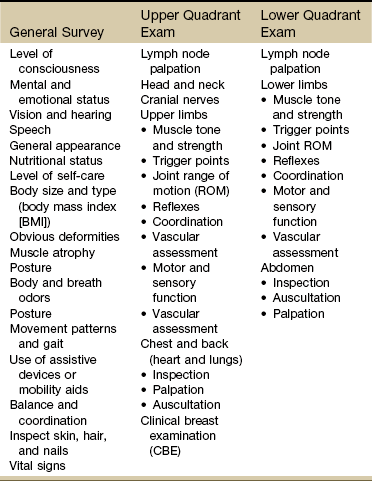

Then, the identified cluster(s) of associated signs and symptoms are reviewed to search for a potential pattern that will identify the underlying system involved (Box 4-19). The therapist may find cause to examine just the upper quadrant or just the lower quadrant more closely. A guide to physical assessment in a screening examination is provided in Table 4-13.

Therapists perform the ROS by categorizing all of the complaints and reported or observed associated signs and symptoms. This type of review helps bring to the therapist’s attention any signs or symptoms the client has not recognized, has forgotten, or thought unimportant. After compiling a list of the client’s signs and symptoms, compare those to the list in Box 4-19. Are there any identifying clusters to direct the decision-making process? See Case Example 4-4.

For example, cutaneous (skin) manifestations and joint pain may occur secondary to systemic diseases, such as Crohn’s disease (regional enteritis) or psoriatic arthritis, or as a delayed reaction to medications. Likewise, hair and nail changes, temperature intolerance, and unexplained excessive fatigue are cluster signs and symptoms associated with the endocrine system.

Changes in urinary frequency, flow of urine, or color of urine point to urologic involvement. Other groupings of signs and symptoms associated with each system are listed as mentioned in Box 4-19. If, for example, the client’s signs and symptoms fall primarily within the genitourinary group, then turn to Chapter 10 for additional, pertinent screening questions listed at the end of the chapter. The client’s answers to these questions will guide the therapist in making a final decision regarding physician referral (see the Case Study at the end of the chapter).

The therapist is not responsible for identifying the specific pathologic disease underlying the clinical signs and symptoms present. However, the alert therapist who recognizes clusters of signs and symptoms of a systemic nature will be more likely to identify a problem outside the scope of physical therapy practice and make the appropriate referral. Early identification and intervention for many medical conditions can result in improved outcomes, including decreased morbidity and mortality.

As mentioned in Chapter 2, there is some consideration being given to possibly changing the terminology in the Guide to reflect the full measure of these concepts, but no definitive decision had been made by the time this text went to press. The idea of Systems Review versus Review of Systems will be discussed and any decision made will go through both an expert and wide review process.

Physician Referral

All skin and nail bed lesions must be examined and evaluated carefully because any tissue irregularity may be a clue to malignancy. It is better to err on the side of being too quick to refer for medical evaluation than to delay and risk progression of underlying disease.

Medical evaluation is advised when the therapist is able to palpate a distended liver, gallbladder, or spleen. This is especially true in the presence of any cluster of signs and symptoms observed during the ROS that are characteristic of that particular organ system.

Headaches that cannot be linked to a musculoskeletal cause (e.g., dysfunction of the cervical spine, thoracic spine, or temporomandibular joints; muscle tension; poor posture) may need further medical referral and evaluation. Conducting an upper quadrant physical screening assessment, including a neurologic screening may help in making this decision.

Vital Signs

Vital sign assessment is a very important and valuable screening tool. If the therapist does not conduct any other screening physical assessment, vital signs should be assessed for a baseline value and then monitored. The following findings should always be documented and reported:

• Any of the yellow caution signs presented in Box 4-7.

• Individuals who report consistent ambulatory hypertension using out-of-office or at-home readings, adults who do not show a drop in BP at night (15 mm Hg lower than daytime measures), and older adults with diagnosed hypertension who have an excessive surge in morning BP measurements.

• African Americans with elevated BP should be evaluated by a medical doctor.

• Pulse amplitude that fades with inspiration and strengthens with expiration.

• Irregular pulse and/or irregular pulse combined with symptoms of dizziness or shortness of breath (SOB); tachycardia or bradycardia.

• Pulse increase over 20 bpm lasting more than 3 minutes after rest or changing position.