Waste Management

After completing this chapter, the student should be able to do the following:

Describe and differentiate the two basic types of waste generated in a dental office.

Describe and differentiate the two basic types of waste generated in a dental office.

List the five types of regulated dental waste.

List the five types of regulated dental waste.

Identify the federal agencies that regulate dental waste.

Identify the federal agencies that regulate dental waste.

Design an acceptable action plan for the management of regulated dental waste.

Design an acceptable action plan for the management of regulated dental waste.

List the eight elements associated with the safer management of regulated dental waste.

List the eight elements associated with the safer management of regulated dental waste.

COMPREHENSIVE WASTE MANAGEMENT PLAN

Dental practices are subject to a variety of federal, state, and local regulations concerning infection control, hazardous materials handling, employee safety, and waste management issues. To be in compliance, all parties must make special efforts to be aware of an ever-increasing number of governmental mandates.

Because office and clinic personnel must have a working understanding of what actually is required, didactic and in-service training is needed. To meet a perceived need, many organizations and proprietary corporations now offer several consulting services, formal training sessions, and audiovisual materials. Because of the competitive nature of such businesses, the scope and value of some programs tend to be inflated. The question arises, “What kinds of programs do we really need and how can we choose the best ones for us?”

All employees must be knowledgeable of Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA) regulations concerning blood-borne pathogens (see Chapter 6), hazardous materials (see Chapter 22), and safe use of chemicals in the laboratory (see Chapter 22). The Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) has standards, many of which are applicable to dentistry, for workplace exposure levels to chemicals, heat, and radiation and for discharge and final treatment of waste materials. Employees also must be aware of their state (and possibly local) requirements concerning sterilization, disinfection, and medical waste management. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) and the American Dental Association (ADA) guidelines/recommendations contain important and valuable information (see related topics in Chapters 8, 11, 12 and 17).

Most offices elect to use external sources (including this book) to become more knowledgeable about the involved rules and regulations. After one understands the rules, the process of compliance is far less imposing. The OSHA and the ADA indicate that personnel who are knowledgeable about the general rules and the specific discipline(s) of the audience must provide the training. The OSHA also requires that training include opportunities for questions. Even though many audiovisual kits contain elements of programmed learning and sets of review questions, such training aids do not involve the presence of a knowledgeable, “live” facilitator.

A bare minimum for personnel training should be attendance at some type of annual program. Unless all required topics are covered, participation in several (more narrowcast) conferences is required. Currently the trend in many states is to reinstate or increase the number of continuing education hours required to obtain or renew a dental license. Apparently, some of the required continuing education time should be devoted to infection control and employee safety issues.

The 2003 CDC guidelines for infection control make two recommendations for general medical waste. First, a medical waste management program for the practice needs to be developed. This written program must follow federal, state, and local regulations. Second, dental practices also need to ensure that all personnel who handle and dispose of potentially infective waste are trained in appropriate methods and that they are informed of the possible safety and health hazards. More specific CDC guidelines related to dental waste are discussed in this chapter.

TYPES OF WASTE

Two basic types of waste in dental office are regulated medical waste and nonregulated medical waste. Many persons mistakenly consider the terms hospital waste, medical waste, and infectious waste as being synonymous. Hospital waste, like dental office waste or household waste, refers to the total discarded solid waste generated by all sources within a given location, according to the EPA (Table 16-1). In a hospital, this waste includes biologic waste materials such as medical, food services, or animal facility waste, in addition to nonbiologic refuse such as clerical paper and plastic items. Medical waste includes materials generated during patient diagnosis, treatment, or immunization in medical, dental, or other healthcare facilities. Infectious waste is a small subset (estimated at 3% of the total) of medical waste that has shown a capability of transmitting an infectious disease. This type of waste is also called regulated medical waste—waste that requires special care. One should note that factors such as the number and virulence of the microorganisms present, host resistance, and the presence and availability of portals of entry have important roles in whether an infection occurs (see Chapter 3).

TABLE 16-1

| Term | Definition |

| Contaminated waste | Items that have had contact with blood or other body secretions |

| Hazardous waste | Waste posing a risk or peril to human beings or the environment |

| Infectious waste | Waste capable of causing an infectious disease |

| Medical waste | Any solid waste∗ that is generated in the diagnosis, treatment, or immunization of human beings or animals in research pertaining thereto, or the production or testing of biologicals. (The term does not include hazardous waste or household waste. Only a small percentage of medical waste is infectious and needs to be regulated.) |

| Regulated waste | Infectious medical waste that requires special handling, neutralization, and disposal |

| Toxic waste | Waste capable of having a poisonous effect |

∗Solid waste includes discarded solid, liquid, semiliquid, or contained gaseous materials.

Adapted from Environmental Protection Agency: Standard for the tracking and management of medical waste (40 CFR parts 22 and 259), Fed Regist 54:326-395, 1989.

INFECTIOUS WASTE MANAGEMENT

Over the last 15 years, differences among federal agencies concerning the definition of infectious medical waste have narrowed. These definitions may be superseded (additional soiled items included) by some states and local jurisdictions. However, no state or local agency can mandate a regulation that does not first encompass all federal rules.

The prevailing view is that no epidemiologic evidence suggests that most medical waste is any more infective than residential waste. Also, no epidemiologic evidence indicates that current medical/dental waste handling and disposal procedures have caused disease in the community. Therefore identifying wastes for which special precautions are necessary is largely a matter of judgment concerning the relative risk of disease transmission.

What now is commonly agreed upon is that only a limited amount of medical waste needs to be regulated (requiring special handling, storage, and disposal methods). Regulated waste as defined by OSHA and some dentistry-related examples are given in Table 16-2. The key factor in defining regulated medical waste rests upon the presence of blood or other potentially infectious material (OPIM). In dentistry OPIM is mainly saliva. Most of the regulated waste in dental offices consists of contaminated sharps and extracted teeth. Some offices involved with surgeries may also generate a small amount of nonsharp solid medical waste such as 2 × 2s or cotton rolls saturated/caked with blood or saliva.

TABLE 16-2

Regulated Waste According to OSHA

| Waste∗ | Examples in dentistry |

| Liquid or semiliquid blood or other potentially infectious material (OPIM) | Liquid blood or saliva |

| Contaminated items that would release blood OPIM in a liquid or semiliquid state if compressed | 2 × 2s or cotton rolls saturated with blood or saliva |

| Items that are caked with dried blood or OPIM that are capable of releasing these materials during handling | 2 × 2s or cotton rolls saturated/caked with blood or saliva |

| Contaminated sharps | Used needles, scalpel blades, orthodontic wire, broken sharp instruments, burs |

| Pathologic or microbiologic wastes containing blood or OPIM | Biopsy specimens, excised tissue, extracted teeth not returned to the patient |

∗OSHA. Blood-borne pathogens standard. Accessed May 2008 at: http://www.osha.gov/pls/oshaweb/owadisp.show_document?p_table=STANDARDS&p_id=10051

BLOOD IN A LIQUID OR SEMILIQUID FORM

All federal agencies consider free-flowing/bulk blood to be infectious medical waste that needs to be regulated. In the overwhelming number of areas, blood (even mixed with other fluids, such as saliva) can be poured or evacuated into the office/clinic waste water system. One should rinse sink traps and evacuation lines thoroughly at least daily. Also helpful is the drawing of a nonbleach disinfectant solution through the lines and final rinsing with water.

Although generally allowed, several locales are attempting to restrict the volume of blood entering their sanitary sewers. These areas have had traditional waste disposal problems of all types, especially with the EPA water quality requirements. Personnel always should be aware of the regulations in their area and become actively involved in attempts to change the current situation.

The 2003 CDC infection control guideline has a recommendation for discharging blood or other body fluids to sanitary sewers or septic tanks. The CDC indicates that one should pour blood, suctioned fluids, or other liquid waste carefully into a drain connected to a sanitary sewer system, provided that local sewage discharge requirements are met and that the state has declared that this is to be an acceptable method of disposal. One must beware of splashing and wear gloves, mask, safety eyewear, and protective clothing while performing this task.

PATHOGENIC WASTE (TEETH AND OTHER TISSUES)

Teeth and other waste tissues are considered potentially infectious pathology waste, and thus their disposal is regulated. One always should use a color-coded and labeled container that prevents leakage (e.g., biohazard bag) to contain nonsharp regulated medical waste. Extracted teeth can be placed in sharps containers.

Many areas allow in-house neutralization of such items. The easiest and most effective procedure is sterilization by heat. Steam autoclaving is the method of choice. However, published information indicates that an unsaturated chemical vapor sterilizer is effective in neutralizing pathologic waste. Because the operation parameters (time, pressure, and temperature) of the unsaturated chemical vapor sterilizer are similar to those of the steam autoclave, it seems logical that such a sterilizer also would be capable of pathologic waste sterilization. One should never use dry heat ovens for this purpose.

The dental team must monitor the operation of the sterilizer routinely (see Chapter 11). Monitoring includes mechanical (physical) examination, chemical indicators, and biologic (spore test) monitors.

Offices and clinics should be discreet about the final disposal of treated infectious medical waste. Reports indicate that waste haulers have refused to empty dumpster boxes or garbage cans if blood and blood soiled items were visible. The best option probably is to place treated items into some type of sealed container, such as a cardboard box, before disposal.

One common problem involves the treatment of teeth containing amalgam restorations. The heat of sterilization could create dangerous mercury vapors. Amalgam-restored teeth can be disinfected before disposal. Ideally, one should use a sterilizing chemical (e.g., full-strength glutaraldehyde). A tooth could be added to a small volume of fresh glutaraldehyde held within a sealed container. Exposure should be for at least 30 minutes. One should then rinse treated teeth well.

One stimulus for the return of teeth involves younger children and the “tooth fairy.” Jurisdictions vary on the validity of such requests and on the procedures to follow to satisfy such an inquiry. However, the 2003 CDC guideline allows extracted teeth to be returned to the patient.

One must dispose of treated teeth and other tissues according to local regulations. Many areas allow these treated items to be added to the nonregulated waste stream. Pathologic waste is best hidden from the view of the public. Final disposal should be in a secured receptacle.

Treated regulated medical waste is waste treated (usually by the application of heat or by incineration) to reduce or eliminate its pathogenicity substantially. This does not necessarily mean that the waste is destroyed or the volume is reduced significantly. For example, autoclaving does not appreciably affect the volume of treated waste materials.

SHARPS

Another form of regulated medical waste known to be capable of transmitting disease is contaminated sharps. All federal agencies consider sharps to be infectious waste. Sharps are items that can penetrate intact skin. Dental examples include injection needles, orthodontic bands and wire, scalpel blades, burs, suture needles, instruments, and broken glass. The OSHA regulations indicate that immediately after use, disposable sharps are to be placed in closable, leakproof, puncture-resistant containers (sharps containers; Figure 16-1). These containers must be labeled with a biohazard symbol and color coded for easy identification. The CDC recommends that sharps containers be located as close as is practical to the work area. This means that each operatory should have at least one sharps container.

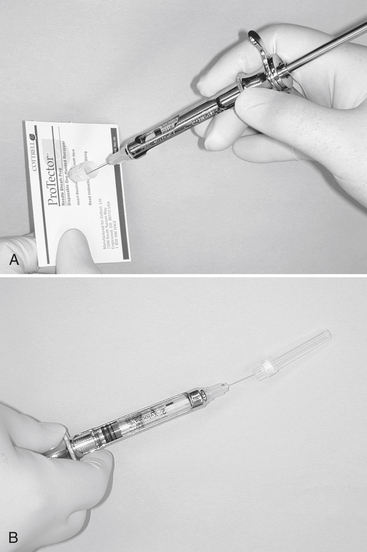

Proper handling of sharps is essential because common personal protective barriers such as gloves often do not prevent sharps punctures or cuts. Box 16-1 gives some examples of sharps safety. To minimize the potential for accidents with injection needles use some type of protective cap-holding device (Figure 16-2, A) or replace the cap sheath using the one-handed scoop technique (Figure 16-2, B).

FIGURE 16-2 The use of a protective cap-holding device A, or recapping a needle using the “scoop technique”. B, requires that the syringe be held in one hand.

Because waste haulers charge a premium for the removal of medical waste, where legally permissible, dental offices should consider treating their sharps containers in-house if allowed by state regulations. Box 16-2 provides specific recommendations for in-house treatment of sharps containers. Figure 16-3 demonstrates placement of a sharps container (with an open top) into a steam autoclave. The size and shape of the containers also can influence overall efficiency of sterilization. Be sure the container is labeled as “sterilizable” so it does not melt in the sterilizer.

RECORD KEEPING

In some areas, regulated medical waste must be removed, neutralized, and disposed of by an approved waste hauler. In some cases, facilities elect to contract for such disposal even though not required to do so. These services are often expensive, especially if the office or clinic is not in the same building with other practices.

One should remember that although another party physically is removing and disposing of the medical waste, the generating facility has the responsibility to ensure use of acceptable and correct methods. One should ask the waste hauler to provide some training materials approved by the Department of Transportation. This material is in addition to the training required or recommended by OSHA. The CDC and local regulations also may apply.

If waste were dumped illegally, the dental practice involved would also be held responsible. Therefore one should establish the credentials of any waste hauler. Speaking to other clients and to local health authorities is essential. The EPA usually approves haulers. They are awarded a unique identifying contractor number, which should appear on all paperwork. A receipt of shipment should be provided by the hauler on removal of the waste. Several weeks after removal, a manifest from the hauler should come through the mail indicating the exact manner in which the waste was treated and its final site of disposal.

American Dental Association. Council on Scientific Affairs and Council on Dental Practice: Infection control recommendations for the dental office and the dental laboratory. J Am Dent Assoc. 1996;127:672–680.

Blumstein, S., Zeller, J., Sharbaugh, R. APIC commentary on “healthcare” waste management: a template for action. Am J Infect Control. 2000;28:E1.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Guidelines for infection control in dental health-care settings. MMWR. 2003;52(RR-17):1–.68. 2003

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention: Workbook for designing, implementing, and evaluating a sharps injury prevention program. Accessed May 2008 at http://www.cdc.gov/sharpssafety/index.html.

Gooch, B.F., et al. Percutaneous exposures to HIV-infected blood among dental workers enrolled in the CDC Needlestick Study. J Am Dent Assoc. 1995;126:1237–1242.

Gordon, J.G., Denys, G.A. Infectious wastes: efficient and effective management. In: Block S.S., ed. Disinfection, sterilization and preservation. ed 5. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2001:1139–1160.

Miller, C.H. Beyond the sticking point. Dent Products Report. 2008;42:112–116.

Miller, C.H. No wasted effort. Dent Products Report. 2007;41:130–134.

Miller, C.H., Palenik, C.J. Sterilization, disinfection and asepsis in dentistry. In: Block S.S., ed. Disinfection, sterilization and preservation. ed 5. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2001:1049–1068.

Palenik CJ: Managing regulated waste in dental environments. Accessed May 2008 at http://www.thejcdp.com/issue013/index.html.

Palenik, C.J. Managing regulated waste in the dental environment. Dent Today. 2004;23:62–63.

US Department of Labor. Occupational Safety and Health Administration: Occupational exposure to blood-borne pathogens: final rule (29 CFR part 1910.1030). Fed Regist. 1991;56:64004–64182.

US Environmental Protection Agency. EPA guide for infectious waste management (EPA/530–5W-86-014). Washington, DC: The Agency; 1986.

Review Questions

______1. On average, what percent of all waste materials generated by a dental practice should be considered as being infectious?

______2. Which of the following should not be considered an example of regulated medical dental waste according to OSHA?

______3. You have just removed two small bags used to cover the light handles of your unit. In most cases, you should:

______4. Which type of waste can best be described as items that have had contact with blood or other body fluids and secretions, such as saliva?

______5. Which of the following is not an acceptable technique for the handling of sharps?