Infection Control Rationale and Regulations

RATIONALE FOR INFECTION CONTROL

RECOMMENDATIONS AND REGULATIONS

SUMMARY OF THE OCCUPATIONAL SAFETY AND HEALTH ADMINISTRATION BLOOD-BORNE PATHOGENS STANDARD

Postexposure Medical Evaluation and Follow-up

Engineering and Work Practice Controls

Handling of Disposable Contaminated Sharps

Handling of Reusable Contaminated Sharps

Instrument Sterilization Not Covered by the Occupational Safety and Health Administration

SUMMARY OF THE CENTERS FOR DISEASE CONTROL AND PREVENTION INFECTION CONTROL RECOMMENDATIONS FOR DENTISTRY

Personnel Health Elements of an Infection Control Program

Prevention of Transmission of Blood-borne Pathogens

Prevention of Exposures to Blood and Other Potentially Infectious Materials

Contact Dermatitis and Latex Hypersensitivity

Sterilization and Disinfection of Patient Care Items

Environmental Infection Control

Dental Unit Water Lines, Biofilms, and Water Quality

Dental Handpieces and Other Devices Attached to Air and Water Lines

Aseptic Technique for Parenteral Medications

After completing this chapter, the student should be able to do the following:

Describe the rationale for performing infection control procedures in a dental office.

Describe the rationale for performing infection control procedures in a dental office.

Describe the pathways by which microbes may be spread in the dental office.

Describe the pathways by which microbes may be spread in the dental office.

List which infection control procedures can be used to interfere with the different pathways of microbial spread in the dental office.

List which infection control procedures can be used to interfere with the different pathways of microbial spread in the dental office.

Describe the goal of infection control.

Describe the goal of infection control.

Describe the role played by governmental and professional organizations in dental infection control.

Describe the role played by governmental and professional organizations in dental infection control.

Summarize blood-borne pathogens standards of the Occupational Safety and Health Administration.

Summarize blood-borne pathogens standards of the Occupational Safety and Health Administration.

Summarize the recommendations for infection control in dentistry from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Summarize the recommendations for infection control in dentistry from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

RATIONALE FOR INFECTION CONTROL

The logic for routinely practicing infection control is that the procedures involved interfere with the steps in development of diseases that may be spread in the office. Chapters 6 and 7 describe the diseases that may be spread; Chapter 3 describes the steps in development of such diseases (source, escape, spread, entry, infection, and disease).

Pathways for Cross-Contamination

A total office infection control program is designed to prevent or at least reduce the spread of disease agents from the following:

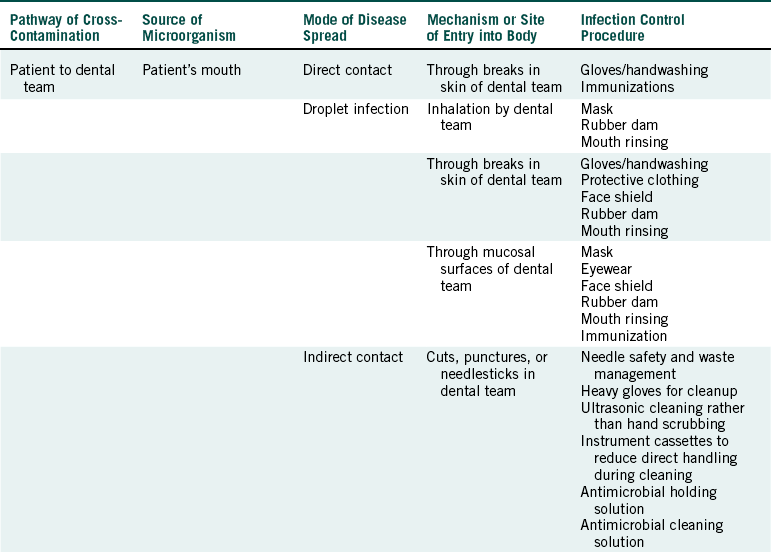

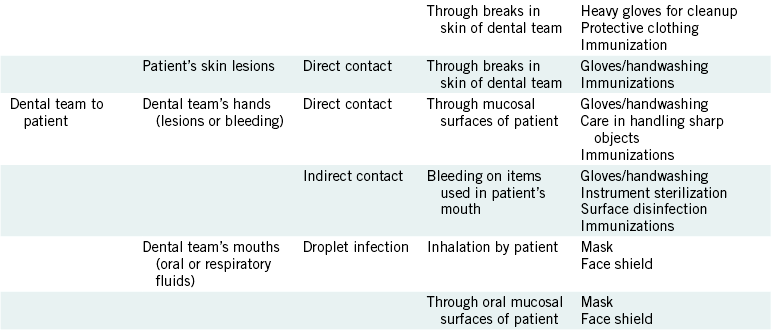

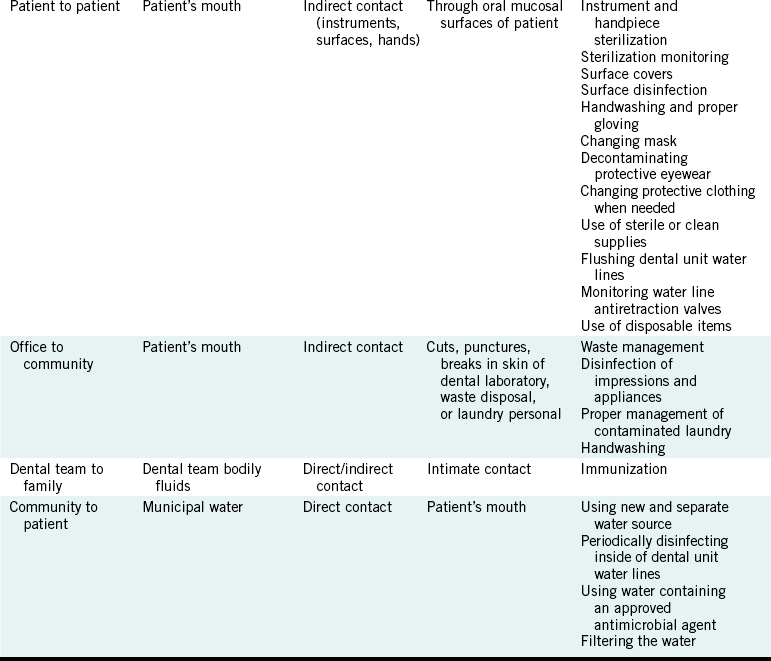

These subdivisions of infection control are based on the five pathways for cross-contamination, and Table 8-1 describes their relationship to modes of disease spread and infection control procedures.

TABLE 8-1

Mechanisms of Disease Spread and Prevention

From US Department of Labor, Occupational Safety and Health Administration: Controlling occupational exposure to blood-borne pathogens, OSHA 3127 (revised), Washington, DC, 1996, OSHA.

PATIENT TO DENTAL TEAM

The opportunities for spread of patient microorganisms to members of the dental team are numerous, and this pathway is more difficult to control than the other fourpathways. Direct contact (touching) with patient’s saliva or blood may lead to entrance of microorganisms through nonintact skin resulting from cuts, abrasions, or dermatitis. Invisible breaks in the skin also exist, especially around the fingernails. Sprays, spatter, or aerosols from the patient’s mouth may lead to droplet infection through nonintact skin; mucosal surfaces of the eyes, nose, and mouth; or inhalation. Indirect contact involves transfer of microorganisms from the source (e.g., the patient’s mouth) to an item or surface and subsequent contact with the contaminated item or surface. Examples include cuts or punctures with contaminated sharp objects (e.g., instruments, needles, burs, files, scalpel blades, and wire) and entrance through nonintact skin as a result of touching contaminated instruments, surfaces, or other items. Another opportunity for disease spread occurs by direct contact with infectious skin lesions or other nonintact skin of the patient with entrance of microorganisms through nonintact skin on the dental member’s hands. This latter route of disease spread in the office is not common.

Infection control procedures to prevent patient-to- dental team spread are listed in Table 8-1 and are described in detail in subsequent chapters.

DENTAL TEAM TO PATIENT

Spread of disease agents from the dental team to patients is a rare event but could happen if members do not follow proper procedures. If the hands of dental team members contain lesions or other nonintact skin, or if their hands are injured while in the patient’s mouth, blood-borne pathogens or other microorganisms could be transferred by direct contact with the patient’s mouth, and they might gain entrance through mucous membranes or open tissue. The patient may have indirect contact with blood-borne pathogens or other agents if a member of the dental team bleeds on instruments or other items that then are used in the patient’s mouth. Chapter 6 describes apparent spread of blood-borne diseases from dentists to patients. Droplet infection of the patient from the dental team could occur, but this can occur in everyday life and is certainly not unique to the dental office.

Infection control procedures that interfere with this pathway of cross-contamination are listed in Table 8-1 and are described later.

PATIENT-TO-PATIENT

Disease agents might be transferred from patient to patient by indirect contact through improperly prepared instruments, handpieces and attachments, operatory surfaces, and hands. Although, at the time of this writing, disease transmission from contaminated instruments or surfaces to dental patients has not been documented, the potential for such transfer does exist and has been documented to occur in the medical field. Conversely, transfer of the herpes simplex virus from a patient to the hands of a hygienist and then to the mouths of several patients has been documented, as described further in Chapter 10 under the discussion on gloves.

PATIENT-TO-PATIENT SPREAD OF HUMANIM MUNODEFICIENCY VIRUS

A report indicates the apparent spread of humanimmunodeficiency virus (HIV) from patient to patient in a medical/surgical practice in New South Wales, Australia. Five of nine patients seen in that medical office on the same day in November 1989 became HIV-positive, but the surgeon was HIV-negative. All five of these patients had minor surgeries that day involving the removal of moles or small cysts. Four of the five patients who became HIV-positive did not have any apparent risk factors for acquiring HIV disease (e.g., intravenous drug abuse, multiple sex partners of unknown HIV status, blood transfusions, or sexually transmitted diseases). These four patients also experienced sore throat, swollen glands under the chin, slight joint pains, and slight fever in December 1989. These are the symptoms of an HIV infection, referred to as acute retroviral syndrome, that usually occur about a month after the initial infection. The fifth patientadmitted to having sex with male partners of unknown HIV status—likely his source of HIV. This patient died of Pneumocystis jiroveci (formerly Pneumocystis carinii) pneumonia (a leading cause of infectious disease death in patients with acquired immunodeficiency syndrome) in 1990. This strongly suggests that he already was infected in November 1989 when he was in the New South Wales medical office and that this patient served as the source of HIV in this incident.

The surgeon in this practice indicated that he ran the office by himself and that he did not use multiple dose injection vials (an important mode of disease spread), did not reuse scalpel blades but did reuse the handles, and changed gloves for every patient. He stated that he processed his contaminated instruments by soaking them in 1% glutaraldehyde, washing them in water, and placing them in boiling water for 5 to 10 minutes. These procedures have several problems (Chapter 11 describes the correct procedures for processing contaminated instruments). Because glutaraldehyde disinfectant/ sterilant is commercially available only at concentrations between 2.0% and 3.4%, the surgeon apparently diluted his glutaraldehyde before using it, which saves money but also dilutes microbial effectiveness. Apparently, the instruments were not scrubbed or ultrasonically cleaned in a detergent, which suggests that blood could have remained on them after “washing in water.” Although boiling likely can kill most microorganisms on instruments, if the instruments are clean, boiling is not a recognized method of sterilization. Obviously, the instruments were not wrapped before processing, so they may have become recontaminated as a result of improper handling after the boiling step but before they were reused on another patient.

The surgeon also stated that the instrument processing area was about 9 feet away from where the surgeries were performed. Without a physical separation between “clean” areas and “dirty” areas, chances increase for cross-contamination. Thus several breaches in infection control procedures are apparent in this medical practice that may have resulted in the spread of HIV from onepatient to four others that day. Unfortunately, theappointment schedule for that day was not available to confirm that the HIV-positive man was an early patient of the day. The infection control procedures used to prevent patient-to-patient spread of disease agents are listed in Table 8-1 and are described in more detail later.

PATIENT-TO-PATIENT SPREAD OF HEPATITIS B VIRUS

Although dental workers are at occupational risk of acquiring hepatitis B, there has been a decline in such cases over the last 20 years due to the vaccine andenhanced infection control procedures. Also, no cases of hepatitis B spread from dentist-to-patient have been reported since 1987. However, the very first report of patient-to-patient spread of the hepatitis B virus (HBV) in a dental office appeared in 2007. This incidentoccurred in September 2001 in an oral surgery practice in New Mexico. The investigation by the CDC and the state department of health showed that the woman who acquired hepatitis B (index patient) had 11 teeth extracted in the same operatory used earlier that day for the extraction of 3 teeth from a patient later found to be HBV-positive (source patient). The same doctor and assisting staff performed the surgeries on both of these patients, but none of the office workers had serologic evidence of HBV-infection. Genetic analysis and viral typing showed that the viruses from theindex and source patients matched. The source patient was HBeAg-positive, which indicated a high viral load. Further investigation revealed no unusual events on that day in question. Medication vials were managed appropriately. Standard precautions for preventing the spread of blood-borne viruses were followed, including appropriate hand antisepsis. Gloves, gowns, and masks were changed for each patient. Nitrous oxide masks were cleaned and disinfected between use, and surgical instruments were hand scrubbed, rinsed, dried, packaged, and processed through a steam sterilizer between patients. High-touch areas in the operatory were covered with plastic or foil and changed for each patient. Surfaces were also disinfected between patients.

Thus, whereas he evidence indicated that patient-to-patient spread of HBV occurred, there was no evidence of a breakdown in procedures. The investigators could only speculate on the mode of transmission. One possibility was cross-contamination from an environmental surface that was not adequately cleaned and disinfected despite the good standard operating procedures detected. The use of multidose vials in general are highly suspect in transmission events, but the procedures performed in this instance were found to be totally appropriate. One interesting note is that 3 of the 5 patients seen on that day after the source patient had already been vaccinated against hepatitis B. This may have limited the spread and prevented the investigators from identifying the mechanisms of the spread by possibly identifying common factors.

DENTAL OFFICE TO COMMUNITY

The dental office to community pathway may occur if microorganisms from the patient contaminate items that are sent out or are transported away from the office. For example, contaminated impressions or appliances or equipment needing service in turn may contaminate personnel or surfaces in dental laboratories and repair centers indirectly. Dental laboratory technicians have been infected occupationally with hepatitis B virus (HBV).

This pathway may also occur if members of thedental team transport microorganisms out of the office on contaminated clothing. In addition, if a member of the dental team acquires an infectious disease at work, the disease could be spread to personal contacts outside the office.

Regulated waste that contains infectious agents and is transported from the office may contaminate waste haulers if it is not in proper containers. Immunity from hepatitis B vaccination protects the dental team from acquiring the disease and passing it along to family members. Other infection control procedures that interfere with the office to community pathway are listed in Table 8-1 and are described in later chapters.

COMMUNITY TO PATIENT

The community to patient pathway involves the entrance of microorganisms into the dental office in the water that supplies the dental unit. These waterborne microorganisms colonize the inside of the dental unit water lines and form a film of microorganisms (biofilm) on the inside of these lines. As water flows through the lines during use of the air-water syringe, high-speed handpiece, or ultrasonic scaler on some units, it “picks up” microorganisms shed by the biofilm. Although municipal water may have a dozen or so bacteria per milliliter (mL) of water as it enters the dental unit, the water exiting a dental unit through the air-water syringe or through the spray from a high-speed handpiece may contain more than 100,000 bacteria per mL. One mL is equivalent to about one fourth of a teaspoon.

No evidence exists that this contaminated water is making individuals sick on any wide scale, but use of heavily contaminated water during dental care is not good infection control practice. Such water certainly must not be used during surgery. Potential pathogens (e.g., Pseudomonas aeruginosa and Legionella pneumophila) may be present in the incoming water and in the dental unit water line biofilm. One report from England describes how in 1988 two cancer-compromised patients acquired oral infections with P. aeruginosa that was later found to be present in water from a dental unit previously used in the care of those patients. Chapter 13 presents more details about contaminated dental unit water, and Table 8-1 suggests infection control procedures to improve the microbial quality of dental unit water.

Goal of Infection Control

After microorganisms enter the body, three basic factors determine whether an infectious disease will develop: virulence (pathogenic properties of the invading microorganism), dose (the number of microorganisms that invade the body), and resistance (body defense mechanism of the host). These factors are called determinants of an infectious disease, and their interaction determines the outcome of an infection as follows:

Health is favored by low virulence, low dose, and high resistance; disease is favored by high virulence, high dose, and low resistance. Prevention of infectious diseases involves influencing the determinants to favor health.

Unfortunately, virulence of microorganisms in their natural environments cannot be changed easily. Thus our body defenses must deal with whatever microorganism presents itself, be it one with high virulence or low virulence. We can enhance our resistance to infectious diseases through specific immunization (e.g., hepatitis B and tetanus), but immunizations are not available against all of the diseases we would like to prevent. Thus the only disease determinant we can manage effectively is the dose, and management of the dose is called infection control.

Therefore, the goal of infection control is to reduce the dose of microorganisms that may be shared between individuals or between individuals and contaminated surfaces. The more the dose is reduced, the better the chances for preventing disease spread. Procedures that minimize spraying or spattering of oral fluids (e.g., rubber dam, high-volume evacuation, and preprocedure mouth rinse) reduce the dose of microorganisms that escape from the source. Handwashing and surface precleaning and disinfection reduce the number of microorganisms that may be transferred to surfaces by touching. Barriers such as masks, gloves, and protective eyewear and clothing reduce the number of microorganisms that contaminate the body or other surfaces.

Instrument precleaning and sterilization eliminate or reduce the number of microorganisms that may be spread from one patient to another. Proper management of infectious waste by using appropriate containers for disposal eliminates or reduces the number of microorganisms that may contaminate persons or inanimate objects. Disease prevention is based on reducing the dose and increasing the resistance of the body.

RECOMMENDATIONS AND REGULATIONS

Recommendations are made by individuals or groups that have no authority for enforcement. Regulations are made by groups that do have the authority toenforce compliance, usually under the penalty of fines, imprisonment, or revocation of professional licenses.

Anyone may make recommendations, but governmental groups or licensing boards in towns, cities, counties, and states make regulations.

Infection Control Recommendations

CENTERS FOR DISEASE CONTROL AND PREVENTION

The current infection control recommendations for dentistry from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) are summarized in this chapter and are presented in total in Appendix B. Although the CDC began making general infection control recommendations many years ago, their first set of complete recommendations directed specifically toward dentistry was in 1986, with updates in 1993 and in 2003. Most infection control procedures practiced in dentistry today are based on the 2003 recommendations. The CDC is a part of the Public Health Service, which is a division of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. The CDC has a Division of Oral Health that studies oral diseases, fluoride applications, and infection control in dentistry. The CDC does not have the authority to make laws, but many of the local, state, and federal agencies use CDC recommendations to formulate the laws. See Appendix B for further information on the CDC and how to access their Web site and infection control recommendations.

The CDC also has published guidelines on preventing the transmission of tuberculosis in health care settings, which include dental offices. Excerpts from these guidelines are presented in Appendixes B and C.

AMERICAN DENTAL ASSOCIATION

The American Dental Association (ADA) has provided detailed infection control recommendations since the 1970s and currently makes such recommendations through its Councils on Scientific Affairs and Dental Practice. The most recent detailed recommendations from the ADA were published in the August 1996 issue of the Journal of the American Dental Association. The ADA supports the 2003 CDC infection control recommendations as described in the ADA’s Statement on Infection Control in Dentistry (see Appendix G). The ADA’s main office is located in Chicago, and Appendix A gives its Web address.

ORGANIZATION FOR SAFETY AND ASEPSIS PROCEDURES

The Organization for Safety and Asepsis Procedures (OSAP) (see Appendix A) is a not-for-profit professional organization composed of dentists, hygienists, assistants, university professors, researchers, manufacturers, distributors, consultants, and others interested in infection control. This broad-based group is the premier infection control education organization in dentistry. The organization provides a monthly publication to keep its members in pace with new information and also provides a newsletter, reports, position papers, announcements, and press releases. This organization also sponsors regional and national educational programs related to infection control for its members. All members of the dental team should join this organization to keep up to date in the area of infection control (see Appendixes A and D).

ASSOCIATION FOR THE ADVANCEMENT OF MEDICAL INSTRUMENTATION

The Association for the Advancement of Medical Instrumentation (AMMI) (see Appendix A) is another voluntary organization that is composed of manufacturers, distributors, researchers, regulators, and users of medical/dental equipment. One component of this organization is devoted to developing sterilization standards, including recommended practices on how properly to use sterilizers and technical documents on the equipment. For example, two documents of particular interest to the dental team describe the proper use and monitoring of small office steam and dry heat sterilizers.

Infection Control Regulations

Some state and local regulations exist in relation to medical waste management, instrument sterilization, and sterilizer spore testing in dentistry. Examples of states with such special dental infection control regulations include California, Connecticut, Florida, Indiana, Missouri, Ohio, Oregon, and Washington. In some instances these regulations are made by the county health departments and in others by state legislatures, state boards of dental examiners, state dental disciplinary boards, or state departments of health.

Twenty-six states also have their own division of the Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA) in their state departments of labor (see Appendix A). These states must administer regional OSHA standards, including those for occupational exposure to blood-borne pathogens and for management of hazardous materials, which are at least as stringent as the federal OSHA standards (see the section on OSHA, p. 86).

Because infection control regulations can vary from state to state, particularly in the areas of instrument sterilization, waste management, and sterilizer spore testing, it is important for the dental team to keep in contact with the various state agencies for the latest information that may affect infection control in the dental office. Two other sources of information may be the state dental association and the infection control officer in a school of dentistry located in the state.

FOOD AND DRUG ADMINISTRATION

The Food and Drug Administration (FDA) (see Appendix A) is a part of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. In relation to infection control, the FDA regulates the manufacturing and labeling of medical devices (such as sterilizers, biologic and chemical indicators, ultrasonic cleaners and cleaning solutions, liquid sterilants [e.g., glutaraldehydes], gloves, masks, surgical gowns, protective eyewear, handpieces, dental instruments, dental chairs, and dental unit lights) and of antimicrobial handwashing agents and mouth rinses.

The purpose of the FDA is to ensure the safety and effectiveness of drugs and medical devices by requiring “good manufacturing practices” and reviewing the devices against associated labeling to ensure that claims can be supported. The FDA may require general controls, certain performance standards, or various items such as notification from a manufacturer that a device is about to be marketed to requiring certain performance standards or approval of the device before marketing. All medical devices to be sold in the United States first must be cleared by the FDA. To do this, the manufacturers submit to the FDA a 510(k) application (premarket notification) that describes the device and the manufacturing facilities and presents the results of studies conducted to support any claims of effectiveness and safety made for the device. The FDA does not control the actual use of a medical device but indicates that misuse (using an item contrary to instructions on the device) transfers any liability for problems that develop from the manufacturer to the user.

ENVIRONMENTAL PROTECTION AGENCY

The U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) (see Appendix A) is associated with infection control by attempting to ensure the safety and effectiveness of disinfectants. The EPA also is involved in regulating medical waste after it leaves the dental office. Information on the safety and effectiveness of disinfectants must be submitted by manufacturers to the EPA for review to make sure that safety and the antimicrobial claims stated for the products are supported with scientific evidence. If the claims meet the criteria, the disinfectant product receives an EPA registration number that must appear on the product label. Chapter 16 discusses EPA involvement with waste management.

OCCUPATIONAL SAFETY AND HEALTH ADMINISTRATION

The Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA) (see Appendix A) is a division of the U.S. Department of Labor, and its charge is to protect the workers of America from physical, chemical, or infectious hazards in the workplace. Chapter 22 describes the OSHA standard for protection against hazardous chemicals. OSHA began to develop its standard for protection against occupational exposure to blood-borne pathogens in 1986 and published the final rules in 1991. The standard is known as the blood-borne pathogens standard, and it became effective nationwide in 1992. OSHA requires that a copy of the regulatory text of this standard be present in every dental office and clinic. Appendix H provides the text of the standard.

This standard indicates that the employer has the responsibility to protect employees from exposure to blood and other potentially infectious materials in the workplace and to give proper care if such exposure does occur. The standard applies to employers in any type of facility in which employees have a potential for exposure to body fluids, including dental and medical offices; dental, clinical, and research laboratories; hospitals; funeral homes; emergency medical services; nursing homes; and others.

Compliance with this standard is monitored through investigations of facilities by OSHA compliance officers after a complaint by an employee of the facility to OSHA. Compliance officers also may investigate a facility with 11 or more employees in the absence of an employee complaint. Noncompliance with any rule in the standard can result in a fine.

The standard is effective throughout the United States and in 26 states is administered by the state OSHA programs. In the other states, the standard is administered through regional branches of the federal OSHA (see Appendix A for details).

SUMMARY OF THE OCCUPATIONAL SAFETY AND HEALTH ADMINISTRATION BLOOD-BORNE PATHOGENS STANDARD

The blood-borne pathogens standard is the mostimportant infection control law in dentistry for protection of health care workers. Box 8-1 describes general steps for employer compliance with this standard, and the seven major sections of the standard are summarized next. Appendix H gives the complete standard.

Exposure Control Plan

Each dental office, clinic, or school must prepare a written exposure control plan that contains the elements listed in Box 8-2. This plan must be reviewed andupdated at least annually, and a copy must be accessible to all employees.

EXPOSURE DETERMINATION

An occupational exposure is defined as any reasonably anticipated skin, eye, mucous membrane, or parenteral (e.g., needlestick, cut, abrasion, or instrument puncture) contact with blood or other potentially infectious material such as saliva that may result from the performance of an employee’s duties. For the exposure determinations, one must survey all tasks performed by all employees and make a list of all job classifications in the office in which all of the employees in that classification have occupational exposure (e.g., “dentist,” “dental hygienist,” “clinical dental assistant”) and then make a second list of job classifications in which some of the employees in that classification may have occupational exposure (e.g., “receptionist,” “bookkeeper,” “office manager”). The employer must make these determinations as if gloves, masks, eyeglasses, and protective clothing are not being used.

Now the employer must make a list of all tasks and procedures or groups of closely related tasks and procedures in which occupational exposure occurs (without regard to personal protective equipment or clothing) and that are performed by employees in job classifications noted in the second list.

Employees in these job classifications on the first and second lists are covered under the standard.

SCHEDULE OF IMPLEMENTATION

The employer must prepare a schedule of when and how each provision of the standard will be implemented. The provisions to be included are listed in Box 8-2 and described further in this chapter. One approach in a small office is simply to make notes on a copy of the standard of when (a specific date) and how each provision will be implemented. Larger facilities may wish to prepare a more extensive document covering all health and safety provisions that includes the exposure control plan.

EVALUATION OF EXPOSURE INCIDENTS

If an employee is exposed to blood, saliva, or other potentially infectious materials, the employer must evaluate the circumstances surrounding the incident. The route of exposure needs to be documented (e.g., splash in the eyes or needlestick in the left thumb), and the source patient, types of protective barriers worn at the time of exposure, and what the employee was doing at the time of exposure should be documented. Documentation can best be accomplished by using an exposure incident report form (see an example in Appendix E). Evaluation of this information will assist in the postexposure medical evaluation (described later) of the employee and will determine whether the employee may need further training in attempts to prevent future exposures.

EVALUATION AND USE OF SAFETY DEVICES

Each dental office must document annually the consideration and implementation of appropriate commercially available and effective safer medical devices designed to eliminate or minimize occupationalexposure. An employer who is required to establish an exposure control plan shall solicit input from nonmanagerial employees responsible for direct patient care who are potentially exposed to injuries from contaminated sharps in the identification, evaluation, and selection of effective engineering and work practice controls and shall document the solicitation in theexposure control plan.

Communication of Biohazards

Informing employees of biohazards is to occur in two general ways: by giving specific information and training and by using labels and signs that identify hazards. The goal of this communication is to eliminate or minimize exposure to blood-borne and other pathogens.

INFORMATION AND TRAINING

The OSHA standard indicates that employers shall ensure that all employees with occupational exposure participate in a training program on the hazards associated with body fluids and the protective measures to be taken to minimize the risk of occupational exposure. Box 8-3 gives the minimum content of the required training program. The training is to be provided at no cost to the employee at the time of initial appointment (before the employee is placed in a position in which occupational exposure may occur) and at least annually thereafter, as well as whenever job tasks change that may reflect the employee’s potential for exposure. The training must be given to full-time, part-time, and temporary employees who have a potential for exposure.

A person must conduct the training or at least be available during the training to answer questions. Training solely by means of a film or videotape or written material without the opportunity for discussion is not acceptable. Likewise, a generic computer program, even an interactive one, is not considered appropriate unless it is supplemented with the site-specificinformation required (e.g., the location of the exposure control plan and the procedures to be followed if an exposure incident occurs) and a person is accessible for interaction.

The OSHA standard requires that the person conducting the training be knowledgeable about blood-borne pathogens and about infection control procedures related to the dental workplace. The dentist-employer, hygienists, assistants, dental school professors, or others may conduct the training, provided they are familiar with blood-borne pathogen control and the subject matter required to be presented. The trainer must be able to answer questions related to the information presented.

The manner of the training must be at a level that is appropriate for the employees being trained (e.g., employee’s education, language, and literacy level). If an employee is proficient only in a foreign language, the trainer or an interpreter must convey the information in that language.

The required record keeping (described subsequently) on the training session includes a description of the qualifications of the person providing the training. Occupational Safety and Health Administration compliance officers will verify the competency of the trainer based on the completion of specialized courses, degree programs, or work experiences if the officer determines during an investigation that deficiencies in training exist.

USE OF SIGNS AND LABELS

Warning labels containing the biohazard symbol and the word “Biohazard” are fluorescent orange or orange-red with the lettering and symbol in a contrasting color (Figure 8-1). Such labels must be affixed to containers of regulated waste, refrigerators and freezers containing blood or other potentially infectious materials, and other containers used to store, transport, or ship blood or other potentially infectious materials. Red bags or red containers may be substituted for labels (if employees are trained as to the meaning of the red bags or containers). Individual containers of blood or other potentially infectious materials that are placed in a labeled container during storage, transport, shipment, or disposal are exempt from the labeling requirement. Contaminated equipment that is to be shipped for service must be labeled, however, and the label must include a description of the part of the equipment that is contaminated.

Contaminated laundry also must be labeled properly, as described later in this chapter.

Hepatitis B Vaccination

Employees covered by the standard must be offered the hepatitis B vaccination series free of charge after they have received the training required by the OSHA standard and within 10 days of their employment. Booster dose or doses also must be made available free of charge if recommended by the U.S. Public Health Service. However, as yet booster doses have not been recommended. If the employee received the complete vaccine series previously, if antibody testing discloses immunity, or if the vaccine is contraindicated for medical reasons, vaccination need not be offered. The employer must not make participation in a prescreening program a prerequisite for receiving hepatitis B vaccination. The vaccine is to be administered by or under the supervision of a licensed physician or other licensed health care professional (e.g., a nurse practitioner), and this professional must be provided with a copy of the OSHA blood-borne pathogens standard (Box 8-4).

If the employee initially declines vaccination but at a later date, while still covered under the standard, decides to accept the offer, the employer must make the vaccine available at no charge at that time. Employers must ensure that employees who decline vaccination sign a specifically worded statement of declination that is printed in the OSHA standard. This statement is reproduced in Chapter 9.

To document compliance, the employer must obtain a written opinion from the physician responsible for the vaccination as to whether the hepatitis B vaccination is indicated for an employee and whether the employee received the vaccination series. The employer must retain this written opinion of employee vaccination status, giving a copy to the employee, and must make it available to a physician who later may be involved in providing a postexposure medical evaluation of the employee. This evaluation will help the evaluating physician determine the need for prophylaxis or treatment related to such an exposure. Maintenance of these records also provides documentation for the employer that a medical assessment of the employee’s ability and indication to receive hepatitis B vaccination was completed.

Postexposure Medical Evaluation and Follow-up

After a report of an exposure incident, the employer must make immediately available to the exposed employee a confidential medical evaluation and follow-up at no cost to the employee at a reasonable time and place and performed or supervised by a licensed physician or other licensed health care professional (Box 8-5). The employer must document the exposure and surrounding circumstances, a task best accomplished by using an exposure incident report form as previously mentioned (see Appendix E). The employer gives this documentation and a job description of the employee as related to the incident, any information documenting the exposed employee’s hepatitis B vaccination status (e.g., past written opinions from the health care professional), any written opinions of a health care professional from past exposure incidents, and a copy of the OSHA standard to the evaluating health care professional.

TESTING OF THE SOURCE INDIVIDUAL

The source individual is any patient whose body fluid is involved in the exposure incident. After an employee exposure, the employer must request promptly that the source individual’s blood be tested (with consent) to determine HBV and HIV infectivity, unless this person already is known to be infected with HBV or HIV. If the source individual does not give consent for testing or if it is not feasible to obtain consent, the employer shall establish that this consent cannot be obtained. If consent is given, the source individual may be sent to the health care professional or an appropriate accredited laboratory or testing site for the testing. The results of the source individual’s tests are confidential and are to be directed only to the health care professional evaluating the exposed employee. The employer must ensure that the exposed employee is informed confidentially of these results by the attending health care professional, but the employer does not have the right to know the source individual’s test results.

TESTING THE EXPOSED EMPLOYEE

The employer must make available collection and testing of blood from the exposed employee for HBV and HIV status with the employee’s consent. The collection can be arranged through the health care professional. If the employee consents to blood collection but does not give consent for testing for HIV, the blood sample is to be preserved for 90 days, in case the employee later consents to testing. The health care professional is to provide medical evaluation and follow-up according to the U.S. Public Health Service recommendations and to provide the employer with a written opinion within 15 days after the evaluation. This written opinion shall include only the following information: (1) that the employee has been informed of the results of the evaluation and (2) that the employee has been told about any medical conditions resulting from exposure that require further evaluation or treatment. All other findings or diagnoses shall remain confidential and shall not be included in the written opinion.

The employer is to keep this written opinion in a confidential employee medical records file with the hepatitis B vaccination written opinion for that employee.

Record Keeping

Records documenting that employees covered under the standard received the required training must contain (1) dates of the training sessions, (2) contents or summary of the training, (3) names and qualifications of the persons conducting the training, and (4) names and job titles of all persons attending the training sessions. The records are to be kept for 3 years from the date on which the training occurred.

EMPLOYEE MEDICAL RECORDS

Medical records for each employee covered under the standard are to include (1) the name and Social Security number of the employee; (2) the hepatitis B vaccination status, including the dates of vaccination and the written opinion from the health care professional regarding the vaccination or the signed statement that the employee declined the offer to be vaccinated; and (3) reports documenting occupational exposure incidents, as well as the written opinion from the health care professional who made the evaluation.

These medical records are confidential and are not to be disclosed except to the employee, anyone having written consent of the employee, representatives of the secretary of labor (on request), or as required or permitted by state or federal law. The records must be maintained for 30 years past the last date of employment.

Universal Precautions

Universal precautions is the concept that all human blood and certain human body fluids that may contain blood are treated as if known to be infectious for HIV and HBV and other blood-borne pathogens. Justification for this concept is based on the inability easily to identify most of those infected with HIV, HBV, or HCV, as described in Chapter 6. Although universal precautions still are used regarding the OSHA blood-borne pathogens standard, the CDC has expanded the concept of universal precautions into what now is called standard precautions. Standard precautions apply not just to contact with blood but also to (1) all body fluids, secretions, and excretions (except sweat) regardless of whether they contain blood; (2) nonintact skin; and (3) mucous membranes.

Engineering and Work Practice Controls

Engineering and work practice controls are to be used to minimize or eliminate employee exposure. If exposure remains after institution of these controls, personal protective equipment also is to be used.

Engineering controls generally act on the hazard itself so that the employee may not have to take self-protective action. An example is use of a sharps container. Work practice controls alter the manner in which a task is performed, reducing the likelihood of exposure, such as safe handling techniques for needles. Employers should examine and maintain or replace all engineering controls and should review work practices regularly to ensure their effectiveness.

HANDWASHING

Readily accessible handwashing facilities are to be provided to employees. In the rare instances when this is not feasible, antiseptic towelettes or an antiseptic hand cleaner and cloth or paper towels are to be provided, with soap and water handwashing to follow as soon as feasible. Employers are to ensure that employees wash their hands as soon as possible after removal of gloves or other personal protective equipment. Hands and other skin are to be washed with soap and water, and mucous membranes are to be flushed with water as soon as feasible after contact of these body sites with blood/saliva.

HANDLING OF DISPOSABLE CONTAMINATED SHARPS

Contaminated needles and other sharps are not to be bent, recapped, or removed unless the employer can demonstrate that no alternative is feasible or that such action is required by a specific medical procedure. Clearly, disposable needles must be removed from the nondisposable dental anesthetic syringes. Recapping is to be accomplished using a one-handed technique or a mechanical device. Shearing or breaking of contaminated needles also is prohibited.

HANDLING OF REUSABLE CONTAMINATED SHARPS

Contaminated reusable sharps (e.g., special needles and sharp instruments) are to be placed in appropriate containers as soon as possible after use. The containers shall be puncture-resistant and color coded or labeled with a biohazard symbol and be leakproof on the sides and bottom. The sharps shall not be stored or processed (before decontamination) in a manner that requires employees to reach blindly into containers where these sharps have been placed.

RESTRICTED ACTIVITIES IN THE WORK AREA

Eating, drinking, smoking, applying of cosmetics or lip balm, and handling of contact lenses are prohibited in work areas where a chance exists for occupational exposure. Food and drink cannot be stored in refrigerators or freezers or kept on shelves or on countertops or in cabinets where blood or saliva is present.

MINIMIZING SPATTER

All procedures involving blood or saliva are to be performed in such a manner that minimizes splashing, spraying, spattering, and generation of droplets of these substances. Although OSHA does not mention specific procedures that limit spatter and generation of droplets in dentistry, one might consider using a rubber dam, high-volume evacuation, and preprocedure mouth rinsing.

SPECIMEN CONTAINERS

Specimens of blood or saliva or other potentially infectious material are to be placed in a container that prevents leakage during collection, handling, processing, storage, or shipping. The container is to be closed and color coded or labeled with a biohazard symbol for storage, transport, or shipping. A second container with the same characteristics is to be used if the outside of the primary container is contaminated. If the specimen could puncture the primary container, a second container with the same characteristics plus being puncture resistant is to be used.

SERVICING OF CONTAMINATED EQUIPMENT

Equipment that may become contaminated with blood or saliva or other potentially infectious materials is to be examined before servicing or shipping and is to be decontaminated as necessary unless the employer can demonstrate that decontamination of such equipment or portions of such equipment is not feasible. If portions remain contaminated, these portions are to be identified and labeled with a biohazard symbol. This identification and labeling information is to be conveyed to all affected employees, the servicing representative, and the manufacturer, as appropriate, before handling, servicing, or shipping so that proper precautions will be taken.

Personal Protective Equipment

When the potential exists for occupational exposure, the employer shall provide, at no cost to the employee, appropriate personal protective equipment such as gloves, protective clothing, masks, face shields or eye protection, and mouthpiece, resuscitation bags, pocket masks, or other ventilating devices. Such equipment is considered appropriate if it does not permit blood or saliva to pass through or to reach the employee’s work clothes, street clothes, undergarments, skin, eyes, mouth, or other mucous membranes under normal conditions of use.

The employer is (1) to ensure that the employee uses the personal protective equipment; (2) to ensure that the regular personal protective equipment in the appropriate sizes is readily accessible in the office (including hypoallergenic gloves, glove liners, powderless gloves, or other alternatives for those who are allergic or have other reactions to the regular gloves); (3) to clean, launder, and when appropriate dispose of personal protective equipment; and (4) to repair or replace personal protective equipment as needed to maintain its effectiveness.

All personal protective equipment is to be removed before the employee leaves the work area. If blood or saliva penetrates a garment, the garment is to be removed immediately or as soon as feasible. On removal, personal protective equipment is to be placed in an appropriately designated area or container for storage, washing, decontamination, or disposal.

GLOVES

Gloves are to be worn when the employee may have hand contact with blood or saliva, mucous membranes, nonintact skin, or when handling or touching contaminated items or surfaces. Handwashing isrequired after glove removal. Surgical or examination gloves are to be replaced as soon as practical when contaminated or as soon as feasible if they are torn, punctured, or otherwise compromised. Disposable gloves are not to be washed or decontaminated for reuse. Utility gloves may be decontaminated for reuse if the integrity of the glove is not compromised. However, they must be discarded if cracked, peeling, torn, or punctured or if they become deteriorated in any way.

MASKS, EYE PROTECTION, AND FACE SHIELDS

Masks in combination with eye protection devices such as goggles or glasses with solid side shields, or chin-length face shields, are to be worn whenever splashes, spray, spatter, or droplets of blood or saliva may be generated and eye, nose, or mouth contamination may occur. If face shields are used, they need to be curved to give protection to the sides of the eyes. If regular prescription glasses are used as protective eyewear, they should have clip-on side shields.

PROTECTIVE CLOTHING

Appropriate protective clothing such as gowns, aprons, lab coats, clinic jackets, or similar outer garments are to be worn in occupational exposure situations. The employer must evaluate the task to determine the appropriate nature of the protective clothing to be used. Examples of different levels of exposure given by OSHA are “soiled” (low level, requiring laboratory coats), “splashed, splattered, or sprayed” (medium level, requiring fluid-resistant garments), “soaked” (high level, requiring fluid-proof garments).

Protective clothing must not permit blood or saliva to pass through or reach the employees’ work clothes, street clothes, undergarments, or skin. If an item of clothing is intended to protect the employees’ person or work clothes or street clothes against contact with blood or saliva, then it would be considered as personal protective clothing. If a uniform is used to protect the employee from exposure, the uniform is considered personal protective clothing. If a lab coat or protective gown is placed over the uniform, the uniform is not protective clothing; the lab coat or gown is. Thus, the outer covering is the protective clothing that the employer must provide.

The employer also is required to maintain, clean, launder, and dispose of all personal protective equipment, including protective clothing, at no cost to the employee. Furthermore, employees cannot launder the protective clothing at home. Thus, employers must provide disposable protective clothing or reusable protective clothing that is laundered in the office or is cleaned by a laundry service. OSHA reasons that, with these options, the employer has control over the protective clothing to ensure proper disposal or cleaning.

Housekeeping

Employers are to ensure that the work site is maintained in a clean and sanitary condition. All equipment and environmental and working surfaces are to be cleaned and decontaminated after contact with blood or other potentially infectious materials. OSHA states that cleaning must be done “after completion of procedures, immediately or as soon as feasible when surfaces are overtly contaminated or after any spill of blood or other potentially infectious materials, and at the end of the work shift if the surface may have become contaminated since the last cleaning.”

The employer must prepare and implement a written schedule for cleaning and method of decontamination of respective work sites within the facility; for example, all uncovered contaminated surfaces in the dental operatory will be sprayed with an iodophor (state the brand), wiped clean, resprayed with the iodophor, let stand for 10 minutes, and wiped dry. This will be performed immediately after care is completed for each patient.

Other statements must be written for other work sites such as the sterilizing room, x-ray room, darkroom, in-office laboratory, restroom, or any other site where surfaces may be contaminated with blood or other potentially infectious materials. OSHA does not specify which disinfectant to use, only that the disinfectant must be registered with the EPA. Although OSHA suggests that the disinfectant used should claim to kill at least HIV and HBV, the authors of this book suggest (as further discussed in Chapter 12) the use of an EPA-registered disinfectant that is tuberculocidal, which is a stronger disinfectant.

Protective coverings (such as plastic wrap, aluminum foil, or imperviously backed absorbent paper) used to protect surfaces or equipment from contamination are to be removed and replaced as soon as possible after contamination or at the end of the work shift. Although not specified by OSHA, protective surface covers need to be replaced between patients as discussed in Chapter 12.

All reusable containers that may become contaminated with blood or other potentially infectious materials are to be inspected and decontaminated on a regular schedule and as soon as feasible if visibly contaminated.

Broken glassware that may be contaminated (e.g., an anesthetic capsule or glass beakers used in the ultrasonic cleaner) is not to be picked up directly with the hands. Mechanical means such as tongs, forceps, or a brush and dustpan should be used.

Regulated Waste

The management of regulated waste is described fully in Chapter 16. Several local, state, or federal laws may apply to various aspects of waste management in specific localities. The Occupational Safety and Health Administration primarily is concerned with the handling and disposal of contaminated sharps; blood or other potentially infectious materials that are in a liquid, semiliquid, or caked state; and pathologic or microbiologic wastes contaminated with blood or other potentially infectious materials.

CONTAMINATED SHARPS

Contaminated sharps (anything that could puncture the skin and contains blood or other potentially infectious materials) are to be placed in containers that are closable, puncture-resistant, leakproof on the sides and bottom, and color coded red or marked with a biohazard symbol. These are called sharps containers or sharps boxes. The containers are to be easily accessible and located as close as possible to where sharps are used or may be found (e.g., at chairside and in the sterilizing room). The containers are to be maintained in an upright position (so that the contents do not spill out) and are to be replaced routinely and not allowed to overflow. The containers are to be closed during handling, storage, transport, and shipment. If the outside of the container is contaminated or if the container leaks, the container is to be placed in a second leakproof, puncture-resistant, color-coded or labeled container during handling, storage, transport, or shipping.

OTHER REGULATED WASTE

Other regulated waste that is nonsharp (e.g., any item that could release liquid, semiliquid, or caked blood or other potentially infectious materials when compressed, such as a blood- or saliva-saturated gauze square) is to be placed in containers that are leakproof, closable, and color coded or labeled with a biohazard symbol. An example is a biohazard bag. The containers are to be closed before handling, storage, transport, or shipping, and if the outside of the container is contaminated, the container is to be placed in a second closable, leakproof, color-coded or labeled container that is closed before handling, storage, transport, and shipping.

Contaminated Laundry

Contaminated laundry (e.g., reusable protective clothing, towels, and patient drapes) is to be handled as little as possible with a minimum of agitation. Laundry is not to be bagged, containerized, sorted, or rinsed in the location of use. Contaminated laundry is to be placed and transported in bags or containers that are color coded or labeled with a biohazard symbol. When a facility uses universal precautions in handling all laundry to be cleaned, alternative labeling is sufficient if it permits all employees to recognize the containers as requiring compliance with universal precautions. If the contaminated laundry is sent off site for cleaning, it must be placed in bags or containers that are color coded or labeled with a biohazard symbol, unless the laundry uses universal precautions in handling all soiled laundry.

Instrument Sterilization Not Covered by the Occupational Safety and Health Administration

An important area of infection control that is not covered under the OSHA blood-borne pathogens standard is instrument sterilization and associated sterilization monitoring in a clinical setting such as the dental office. These procedures are considered as patient-protection procedures rather than worker-protective procedures. Because OSHA is charged by the U.S. Congress to protect the workers of America, it cannot legally make or enforce rules that relate only to patient protection.

Appropriate procedures for processing reusable dental instruments and handpieces are described in recommendations from important organizations such as the CDC, ADA, Organization for Safety and Asepsis Procedures, and Association for Advancement of Medical Instrumentation. Several states, including Florida, Indiana, Ohio, Oregon, and Washington, also have passed laws requiring sterilization of all reusable instruments and handpieces between patients and monitoring of sterilization processes. Chapter 11 presents specific details for instrument sterilization and sterilization monitoring.

SUMMARY OF THE CENTERS FOR DISEASE CONTROL AND PREVENTION INFECTION CONTROL RECOMMENDATIONS FOR DENTISTRY

The CDC published its current infection control recommendations for dentistry in 2003. Many of their recommendations are the same as those in OSHA’s blood-borne pathogens standard, so only those that differ from the OSHA rules are summarized here. Appendix B gives the complete list of the CDC recommendations.

The CDC categorizes each of their recommendations depending on the scientific evidence available to support the recommendation. These categories are included with the recommendations presented inAppendix B.

Personnel Health Elements of an Infection Control Program

A written program is to be prepared that includes policies, procedures, and guidelines for education and training; immunizations; exposure prevention and postexposure management; medical conditions, work-related illness, and associated work restrictions; contact dermatitis and latex hypersensitivity; and maintenance of records, data management, andconfidentiality.

Prevention of Transmission of Blood-borne Pathogens

All dental office personnel are to be tested for antibody to hepatitis B surface antigen (HBsAg) 1 to 2 months after completion of the three-dose hepatitis B vaccination. Nonresponders are to receive a second three-dose series of the vaccine and to be retested for antibody to HBsAg. Nonresponders to this second series should be tested for HBsAg (to determine if they are hepatitis B virus carriers).

Prevention of Exposures toBlood and Other PotentiallyInfectious Materials

Standard precautions (see the previous discussion on p. 91) are to be used to protect against exposure to all body fluids, excretions (except sweat), and secretions (e.g., saliva) and against contact with nonintact skin and mucous membranes.

Hand Hygiene

If hands are visibly soiled or contaminated with blood or other potentially infectious material, they are to be washed with a non-antimicrobial or an antimicrobial soap and water. If the hands are not visibly soiled, they can be washed with a non-antimicrobial or an antimicrobial soap and water or can be decontaminated with an alcohol-based hand rub. For oral surgical procedures, before putting on sterile gloves, the hands can be washed with an antimicrobial soap and water and dried with sterile towels or they can be washed with a non-antimicrobial soap and water, dried, and decontaminated with an alcohol-based hand rub. All liquid hand care products are to be stored in closed containers that are disposable or can be cleaned, if refilled. When refilling, one should empty the container and wash it rather than adding the lotion or soap to top off the container. This allows for removal of any contaminants that may have entered the container during use. Hand lotions should be used to prevent skin dryness, but they should be used at the end of the day or not contain petroleum or oil emollients that can affect the integrity of latex gloves. Fingernails are to be kept short (¼ inch maximum), and artificial nails in general are not recommended. Hand jewelry also is not recommended, if it interferes with the donning of gloves or their fit or integrity.

Personal Protective Equipment

One should clean eyewear and reusable face shields with soap and water, or, if they are visibly soiled, one should clean and disinfect them between patients. One should wear sterile surgeon’s gloves when performing surgery. (See the following definition of oral surgery.)

Contact Dermatitis and Latex Hypersensitivity

The CDC indicates that dental office personnel need to be educated about the skin reactions that can occur with frequent hand hygiene and the use of gloves. All patients also should be screened for latex allergy, and a latex-safe environment should be available for patients and office staff with a latex allergy. Latex-free dental and emergency kits are to be available at all times.

Sterilization and Disinfection of Patient Care Items

A central instrument processing area should be designated and divided into (1) receiving, cleaning, and decontamination; (2) preparation and packaging; (3) sterilization; and (4) storage. One should be careful that contaminated instruments are not intermingled with sterile instruments and should minimize the handling of loose contaminated instruments during transport. One should use automated cleaning equipment to clean visible blood and organic material from instruments and devices before sterilization or disinfection procedures. In addition to other barriers, one should wear puncture- and chemical-resistant gloves for instrument cleaning and decontamination procedures. Critical and semicritical instruments are to be packaged and heat sterilized in an FDA-cleared device (sterilizer) before use. Heat-sensitive items can be reprocessed using FDA-cleared liquid sterilants or an FDA low-temperature sterilization method. One should not use liquid sterilants for surface disinfection or as a holding solution.

One should use a container system or packaging material compatible with the type of sterilizer being used and should add an internal chemical indicator to every package. If the internal indicator cannot be seen from the outside, one should add an external indicator to each package. One should monitor each sterilizer load with mechanical monitors (e.g., time, temperature, and pressure) and should use a biologic indicator with a matched control to monitor the sterilizer at least weekly. One should allow packages to dry before removing them from the steam sterilizer.

One should check the integrity of each sterilized package before use and reclean, repackage, and resterilize the instrument, if packaging is torn or compromised in any way. Semicritical instruments that will be used immediately or within a short period of time can be sterilized unwrapped on a tray or in a container system, provided they are handled aseptically during removal from the sterilizer and transport to the point of use. Critical instruments intended for immediate use may be sterilized unwrapped provided that they are maintained sterile during removal from the sterilizer and transport.

In case of a sterilization failure (e.g., positive spore test), one should review the procedures used to determine any operator error. One should take the sterilizer out of service and retest it with mechanical, chemical, and biologic monitors. If the repeat spore test is negative and the mechanical and chemical monitoring are satisfactory, the sterilizer can be put back in service. If not, one should determine the cause of the failure and rechallenge the sterilizer with biologic indicators three consecutive times before placing it back into service.

Environmental Infection Control

One should clean and disinfect clinical contact surfaces that are not barrier protected with an EPA-registered low-level (with a label claim against HIV and HBV) or an intermediate-level (has a tuberculocidal claim) hospital disinfectant after each patient. One should use an intermediate-level disinfectant if the surface is visibly contaminated with blood. Walls, floors, and sinks (housekeeping surfaces) are to be cleaned routinely with soap and water or an EPA-registered, low-level, hospital disinfectant. Reusable mop heads and cloths are to be cleaned and allowed to dry after use. Carpeting and cloth-upholstered furnishings in the dental operatory, laboratory, and instrument-processing area are to be avoided.

Dental Unit Water Lines, Biofilms, and Water Quality

One should use water that meets the EPA drinking water standard (no more than 500 CFU/mL of heterotrophic bacteria) for routine dental care. One should check with the dental unit manufacturer for appropriate procedures and equipment needed to maintain this water quality and for monitoring the water quality. One should flush the handpiece, air/water syringes, and ultrasonic scalers with water and air for 20 to 30 seconds after each patient before removing them from the water lines. One should maintain antiretraction valves in the dental units, if present.

Boil-Water Notices

One should not use dental unit water or faucet water coming from the public water system during a boil-water notice. One should use alcohol-based hand rubs rather than an agent requiring water for hand hygiene or should use bottled water or antimicrobial towelettes. One should flush the dental unit water lines and faucets after the boil-water notice is lifted following the local recommendations or for 1 to 5 minutes in the absence of recommendation. One should consider disinfecting the dental unit water lines as recommended by the dental unit manufacturer.

Dental Handpieces and Other Devices Attached to Air and Water Lines

One should follow the manufacturers’ instructions to clean and heat-sterilize handpieces and other intraoral instruments (e.g., slow-speed handpiece motors and attachments) that can be removed from the air and water lines of dental units between patients. One should not surface disinfect or use liquid sterilants or ethylene oxide gas on these items. One should not advise patients to close their lips around the tip of saliva ejectors to evacuate oral fluids.

Dental Radiology

One should use heat tolerant or disposable intraoral film-holding or positioning devices whenever possible and should clean and heat sterilize these devices between patients. One should transport and handle exposed radiographs in an aseptic manner to prevent contamination of developing equipment. For digital radiography sensors, following the manufacturers’ directions, one should heat sterilize, cover with an EPA-cleared barrier, treat with a liquid sterilant, or as last resort clean and disinfect with an EPA-registered intermediate-level (tuberculocidal) disinfectant between patients.

Aseptic Technique for Parenteral Medications

One should not administer medication from a syringe to multiple patients even if the needle is changed. One should use single-dose vials of medications when possible and should not combine the leftovers of single-dose vials for later use. If one uses multiple-dose vials, one should clean the access diaphragm with 70% alcohol before inserting a device into the vial. One should use a sterile device (needle and syringe) to enter the vial and should not touch the diaphragm. One should not reuse the syringe. One should keep the multiple-dose vial away from the treatment area to avoid accidental contamination with spray or spatter and should discard the multiple-dose vials if sterility is compromised.

Single-Use (Disposable) Devices

One should use single-use devices for one patient only and should dispose of them appropriately.

Oral Surgical Procedures

When performing oral surgery, one should perform surgical hand antisepsis before donning sterile surgical gloves, washing the hands with an antimicrobial soap and water, and drying them with sterile towels or washing them with a non-antimicrobial soap and water, drying them, and using an alcohol-based hand rub before donning sterile surgical gloves. One should use sterile surgical gloves when performing oral surgical procedures. One should use sterile saline or water as a coolant/irrigator when performing oral surgery using devices specifically designed for delivery of sterile fluids.

The CDC defines oral surgical procedures as “the incision, excision, or reflection of tissue that exposes the normally sterile areas of the oral cavity (e.g., biopsy, periodontal surgery, apical surgery, implant surgery and surgical extraction of teeth such as removal of erupted or non-erupted teeth requiring the elevation of mucoperiosteal flap, removal of bone and/or section of tooth, and suturing, if needed).”

Handling of Extracted Teeth

One should dispose of extracted teeth as regulated medical waste unless they are returned to the patient. One should not dispose of teeth containing amalgam in regulated medical waste intended for incineration. One should clean and place extracted teeth in a leak-proof container labeled with a biohazard symbol and containing an appropriate disinfectant for transport to educational institutions or to a dental laboratory. One should heat sterilize teeth that do not contain amalgam before they are used for educational purposes.

Dental Laboratory

One should use personal protective equipment when handling items received in the laboratory until they have been decontaminated. One should clean, disinfect, and rinse all dental prostheses and prosthodontic materials (e.g., impressions, bite registrations, occlusal rims, and extracted teeth) using an EPA-registered, intermediate-level (tuberculocidal) hospital disinfectant before they are handled in the laboratory. One should consult with manufacturers regarding the stability of specific materials relative to disinfectant procedures and should include specific information as to the decontamination procedure used when laboratory cases are sent off site and on their return. One should clean and heat sterilize heat-tolerant items used in the mouth including metal impression trays and face-bow forks, following the manufacturers’ recommendations for cleaning and sterilizing or disinfecting items that do not normally contact the patient (e.g., burs, polishing points, rag wheels, articulators, case pans, and lathes). If such recommendations are not available, one should clean and heat sterilize heat-tolerant items or clean and disinfect them with an EPA-registered low- to intermediate-level hospital disinfectant, depending on the degree of contamination.

Program Evaluation

Dental offices are to establish a routine evaluation of their infection control programs, including evaluation of performance indicators at an established frequency. (Chapter 20 gives further information on evaluation.)

American Dental Association: ADA statement on infection control in dentistry. http://www.ada.org/prof/resources/positions/statements/infectionconrol.asp. Accessed January, 2008.

American Dental Association. Councils on Scientific Affairs and Dental Practice: Infection control recommendations for the dental office and the dental laboratory. J Am Dent Assoc. 1996;127:672–680.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention: Guideline for infection-control in dental health-care settings. MMWR. 2003;52(RR-17):1–66.

Miller, C.H. Additions to the OSHA blood-borne pathogens standard. Am J Dent. 2001;14:186.

Miller, C.H. Averting spread of infectious disease. Dent Prod Rpt. 2006;40:122.

Miller, C.H. Complying with OSHA. Dent Prod Rpt. 2007;40:82.

Miller, C.H. Infection control strategies for the dental office. In: Ciancio S.G., ed. ADA guide to dental therapeutics. ed 3. Chicago: American Dental Association; 2003:551–566.

Redd, J.T., et al. Patient-to-patient transmission of hepatitis B virus associated with oral surgery. J Infect Dis. 2007;195:1311–1314.

US Department of Labor. Occupational Safety and Health Administration: 29 CFR Part 1910.1030: Occupational exposure to blood-borne pathogens: final rule. Fed Regist. 1991;56:64004–64182. (actual regulatory text, pp 64175-64182)

US Department of Labor. Occupational Safety and Health Administration: Controlling occupational exposure to blood-borne pathogens, OSHA 3127 (revised). Washington, DC: OSHA; 1996.

US Department of Labor. Occupational Safety and Health Administration: Controlling occupational exposure to blood-borne pathogens in dentistry, OSHA 3129. Washington, DC: OSHA; 1992.

Review Questions

______1. Which governmental agency controls the safety and effectiveness of sterilizers?

a. Food and Drug Administration

b. Environmental Protection Agency

______2. Which governmental agency requires employers to protect their employees from exposure to blood and saliva at work?

a. Food and Drug Administration

b. Environmental Protection Agency

______3. Which governmental agency controls the safety and effectiveness of surface disinfectants?

a. Food and Drug Administration

b. Environmental Protection Agency

______4. Not doing a good job cleaning or sterilizing reusable hand instruments contributes to which pathway of cross-contamination in the office?

______5. Improving the quality of dental unit water addresses which pathway of cross-contamination in the office?

______6. The goal of dental infection control is to:

a. eliminate all microbes in the office

b. prevent all pathogenic microbes from entering the office

c. sterilize all operatory surfaces between patients

d. reduce the dose of microorganisms that may be shared between individuals

______7. Which of the following is the infection control education organization in dentistry?

a. Association for Advancement of Medical Instrumentation

b. Organization for Safety and Asepsis Procedures

______8. Which of the following infection control procedures is not covered by the blood-borne pathogens standard?

a. wearing a surgical mask at chairside during patient care

b. wearing gloves during instrument processing and operatory cleanup

d. cleaning and sterilizing reusable hand instruments between patients

______9. According to the blood-borne pathogens standard, who pays for employee training and hepatitis B immunization?

______10. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention guidelines for infection control in dentistry: