Chapter 17 Recognizing the Imaging Findings of Trauma

Trauma is the leading cause of death, hospitalization, and disability in Americans from the age of 1 year through age 45. The major imaging findings of most organ system’s trauma will be discussed as a group in this chapter. Table 17-1 summarizes some of the traumatic injuries that are discussed in other chapters.

Trauma is the leading cause of death, hospitalization, and disability in Americans from the age of 1 year through age 45. The major imaging findings of most organ system’s trauma will be discussed as a group in this chapter. Table 17-1 summarizes some of the traumatic injuries that are discussed in other chapters.TABLE 17-1 OTHER MANIFESTATIONS OF TRAUMA

| Injury | Discussed in |

|---|---|

| Pleural effusion/hemothorax | Chapter 6 |

| Aspiration | Chapter 7 |

| Pneumothorax, pneumomediastinum and pneumopericardium | Chapter 8 |

| Fractures and dislocations | Chapter 22 |

| Head trauma | Chapter 25 |

Chest Trauma

Chest injuries in trauma patients are very common and are responsible for one out of four trauma-related deaths. The overwhelming majority of chest trauma is the result of motor vehicle accidents.

Chest injuries in trauma patients are very common and are responsible for one out of four trauma-related deaths. The overwhelming majority of chest trauma is the result of motor vehicle accidents.Rib Fractures

The severity of underlying visceral injury is usually more important than the rib fractures themselves, but their presence might provide clues to unsuspected pathology.

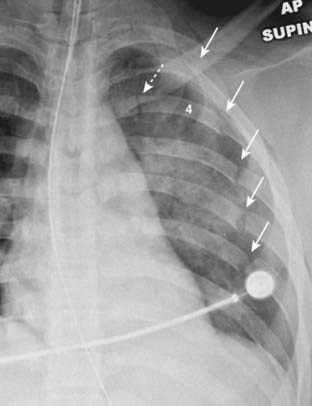

The severity of underlying visceral injury is usually more important than the rib fractures themselves, but their presence might provide clues to unsuspected pathology. Fractures of the first three ribs are relatively uncommon and, if they occur following blunt trauma, indicate a sufficient amount of force to produce other internal injuries (Fig. 17-1).

Fractures of the first three ribs are relatively uncommon and, if they occur following blunt trauma, indicate a sufficient amount of force to produce other internal injuries (Fig. 17-1). Fractures of ribs 4-9 are common and important if they are displaced (pneumothorax) or if there are two fractures in each of three or more contiguous ribs (flail chest).

Fractures of ribs 4-9 are common and important if they are displaced (pneumothorax) or if there are two fractures in each of three or more contiguous ribs (flail chest).

Fractures of ribs 10-12 may indicate the presence of underlying trauma to the liver (right side) or the spleen (left side), especially if they are displaced.

Fractures of ribs 10-12 may indicate the presence of underlying trauma to the liver (right side) or the spleen (left side), especially if they are displaced. In cases of minor trauma, it is not unusual for rib fractures to be undetectable on the initial examination but to become visible in several weeks after callus begins to form.

In cases of minor trauma, it is not unusual for rib fractures to be undetectable on the initial examination but to become visible in several weeks after callus begins to form.

Rib fractures are important primarily for the complications they might produce or the unsuspected pathology they might herald. Fractures of the first three ribs (solid white arrows) are relatively uncommon; following blunt trauma, their presence is a clue that the force to the chest may have been sufficient to produce other internal injuries. Don’t mistake the normal costovertebral junction (solid black arrow) for a fracture.

Pulmonary Contusions

Pulmonary contusions are the most frequent complications of blunt chest trauma. They represent hemorrhage into the lung, usually at the point of impact.

Pulmonary contusions are the most frequent complications of blunt chest trauma. They represent hemorrhage into the lung, usually at the point of impact. Recognizing a pulmonary contusion

Recognizing a pulmonary contusion

Classically, they appear within 6 hours after the trauma and, because blood in the airspaces tends to be reabsorbed quickly, disappear within 72 hours, frequently sooner.

Classically, they appear within 6 hours after the trauma and, because blood in the airspaces tends to be reabsorbed quickly, disappear within 72 hours, frequently sooner. Airspace disease that lingers more than 72 hours should raise suspicions of another process such as aspiration pneumonia or a pulmonary laceration.

Airspace disease that lingers more than 72 hours should raise suspicions of another process such as aspiration pneumonia or a pulmonary laceration.

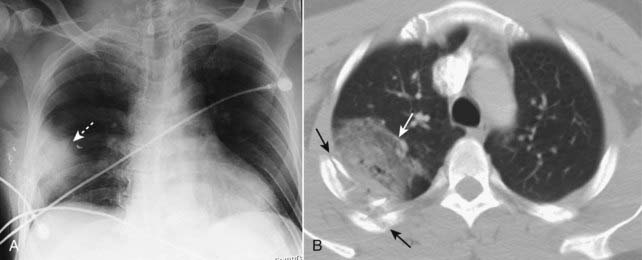

Figure 17-3 Pulmonary contusions, chest radiograph and CT.

A, Pulmonary contusions tend to be peripherally placed most frequently at the point of maximum impact (dotted white arrow). Air bronchograms are usually not present because blood fills the bronchi as well as the airspaces. B, A second patient, who was in an unrestrained passenger in an automobile accident, also has a large contusion (solid white arrow) associated with multiple rib fractures (solid black arrows).

Pulmonary Lacerations (Hematoma or Traumatic Pneumatocele)

Pulmonary hematomas result from a laceration of the lung parenchyma and, as such, may accompany more severe blunt trauma or penetrating chest trauma.

Pulmonary hematomas result from a laceration of the lung parenchyma and, as such, may accompany more severe blunt trauma or penetrating chest trauma. They are sometimes masked by the airspace disease from a surrounding pulmonary contusion, at least for the first few days until the contusion resolves.

They are sometimes masked by the airspace disease from a surrounding pulmonary contusion, at least for the first few days until the contusion resolves. Recognizing a pulmonary laceration

Recognizing a pulmonary laceration

Unlike pulmonary contusions that clear rapidly, pulmonary lacerations, especially if they are blood filled, may take weeks or months to completely clear.

Unlike pulmonary contusions that clear rapidly, pulmonary lacerations, especially if they are blood filled, may take weeks or months to completely clear.

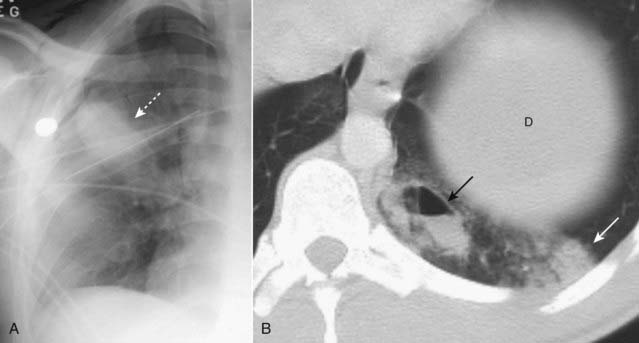

Figure 17-4 Pulmonary lacerations, conventional radiograph, and CT.

Lacerations are sometimes masked, at least for the first few days, by the airspace disease in a surrounding pulmonary contusion. A, If they are completely filled with blood, they will appear as an ovoid mass (dotted white arrow). B, If they are partially filled with blood and partially filled with air, they may contain a visible air-fluid level (solid black arrow). Unlike the neighboring pulmonary contusion (solid white arrow), pulmonary lacerations, especially if they are blood filled, may take weeks or months to completely clear. The top of the left hemidiaphragm (D) is seen in this image.

Aortic Trauma

Trauma to the aorta is most frequently the result of deceleration injuries in motor vehicle accidents. Although the survival rates are improving, most patients with rupture of the thoracic aorta die before reaching the hospital and, of those who survive an aortic injury, the likelihood of death increases the longer the abnormality remains untreated. Only those with incomplete tears in which the adventitial lining prevents exsanguination (producing a pseudoaneurysm) survive to be imaged.

Trauma to the aorta is most frequently the result of deceleration injuries in motor vehicle accidents. Although the survival rates are improving, most patients with rupture of the thoracic aorta die before reaching the hospital and, of those who survive an aortic injury, the likelihood of death increases the longer the abnormality remains untreated. Only those with incomplete tears in which the adventitial lining prevents exsanguination (producing a pseudoaneurysm) survive to be imaged. The most common site of injury is the aortic isthmus, which is the portion of the aorta just distal to the origin of the left subclavian artery. Seat-belt injuries may involve the abdominal aorta, but such injuries are far less common than the deceleration injuries to the thoracic aorta.

The most common site of injury is the aortic isthmus, which is the portion of the aorta just distal to the origin of the left subclavian artery. Seat-belt injuries may involve the abdominal aorta, but such injuries are far less common than the deceleration injuries to the thoracic aorta. Only emergency surgery will prevent approximately 50% of patients with blunt aortic injuries from dying within the first 24 hours if left untreated.

Only emergency surgery will prevent approximately 50% of patients with blunt aortic injuries from dying within the first 24 hours if left untreated. Recognizing aortic trauma

Recognizing aortic trauma

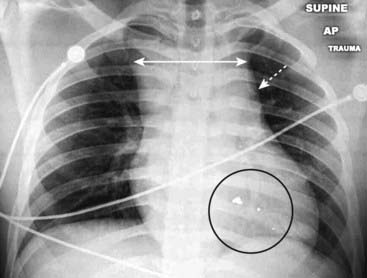

Figure 17-5 Mediastinal hematoma.

There is “widening of the mediastinum” (double white arrow), an inexact finding on an AP supine, portable chest radiograph. More importantly, the shadow of the aortic knob is obscured by something of soft tissue density (dotted white arrow). Because the patient had been shot (bullet fragments in the black circle), these findings led to a request for a CT scan of the chest which demonstrated a large mediastinal hematoma.

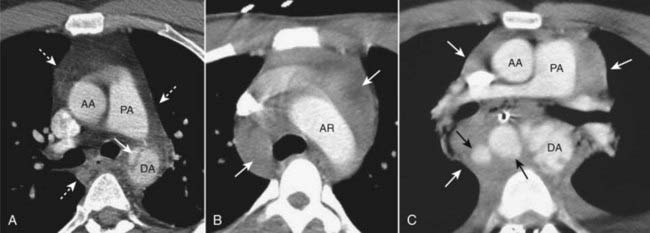

Figure 17-6 Aortic trauma, three different patients.

A, There is a tear at the level of the aortic isthmus represented by the lucent defect in the wall of the descending aorta (solid white arrow). A mediastinal hematoma is also present (dotted white arrows). B, There is a large mediastinal hematoma (solid white arrows). C, There are periaortic hematomas containing extravasated blood (solid black arrows) and a large mediastinal hematoma (solid white arrows). (AA = ascending aorta; AR = aortic arch; DA = descending aorta; PA = pulmonary artery.)

Abdominal Trauma

The role of advanced imaging techniques deserves special mention in abdominal trauma. Radiology has made a significant impact on the lives of traumatized patients by distinguishing those patients who can be managed conservatively from those who need surgical or other interventions and by helping to direct the most appropriate intervention for those who need it.

The role of advanced imaging techniques deserves special mention in abdominal trauma. Radiology has made a significant impact on the lives of traumatized patients by distinguishing those patients who can be managed conservatively from those who need surgical or other interventions and by helping to direct the most appropriate intervention for those who need it. CT is the study of choice in abdominal trauma.

CT is the study of choice in abdominal trauma.

The most commonly affected solid organs in blunt abdominal trauma (in order of decreasing frequency) are the spleen, liver, kidney, and urinary bladder.

The most commonly affected solid organs in blunt abdominal trauma (in order of decreasing frequency) are the spleen, liver, kidney, and urinary bladder.Box 17-1 Focused Abdominal Sonogram for Trauma (FAST)

Liver

The liver is discussed first because it is actually the most frequently injured organ if both penetrating and blunt traumas are included together. The liver is the largest intraabdominal organ and is fixed in position, making it especially susceptible to injury. Injuries to the liver account for the majority of deaths from abdominal trauma.

The liver is discussed first because it is actually the most frequently injured organ if both penetrating and blunt traumas are included together. The liver is the largest intraabdominal organ and is fixed in position, making it especially susceptible to injury. Injuries to the liver account for the majority of deaths from abdominal trauma. The posterior aspect of the right lobe is injured most frequently. Most hepatic injuries are associated with blood in the peritoneal cavity (hemoperitoneum).

The posterior aspect of the right lobe is injured most frequently. Most hepatic injuries are associated with blood in the peritoneal cavity (hemoperitoneum). Contrast-enhanced CT is the study of choice and, because of its ability to demonstrate both the nature and extent of the trauma, the overwhelming majority of patients with liver trauma are now managed conservatively and do not require surgery.

Contrast-enhanced CT is the study of choice and, because of its ability to demonstrate both the nature and extent of the trauma, the overwhelming majority of patients with liver trauma are now managed conservatively and do not require surgery. CT findings in hepatic trauma (Fig. 17-7):

CT findings in hepatic trauma (Fig. 17-7):

Figure 17-7 Hepatic trauma, three different patients.

A, There is a lenticular fluid collection involving the lateral portion of the right lobe of the liver that represents a subcapsular hematoma (solid black arrow). A laceration of the right lobe is also present (dotted black arrow). B, There are multiple lacerations of the right lobe of the liver (black circle). C, Active extravasation of contrast-enhanced blood (solid black arrow) is seen from a large intrahepatic laceration with hematoma (dotted black arrow) and there is both subcapsular blood and hemoperitoneum (solid white arrow).

Spleen

Splenic trauma is usually caused by deceleration injuries in unrestrained occupants of motor vehicle collisions, by a fall from a height, or a pedestrian being struck by a motor vehicle.

Splenic trauma is usually caused by deceleration injuries in unrestrained occupants of motor vehicle collisions, by a fall from a height, or a pedestrian being struck by a motor vehicle. Because the spleen is the most highly vascular organ, hemorrhage represents the most serious complication of trauma. Despite its vascular nature and the delayed presentation of many splenic injuries, most splenic trauma is treated conservatively (nonsurgically).

Because the spleen is the most highly vascular organ, hemorrhage represents the most serious complication of trauma. Despite its vascular nature and the delayed presentation of many splenic injuries, most splenic trauma is treated conservatively (nonsurgically). CT is the study of choice for evaluating splenic trauma. Findings include (Fig. 17-8):

CT is the study of choice for evaluating splenic trauma. Findings include (Fig. 17-8):

Figure 17-8 Splenic trauma, three different patients.

A, A crescent-shaped collection of fluid is demonstrated in the subcapsular space which compresses the normal splenic parenchyma representing subcapsular hematoma (solid white arrow). B, This patient has a splenic (solid white arrow) and hepatic (solid black arrow) laceration and a large hepatic contusion (dotted black arrow). There is also pneumoperitoneum (dotted white arrow). C, Active extravasation of contrast-enhanced blood (solid black arrow) is shown along with a large intrasplenic hematoma (solid white arrow).

Kidneys

Motor vehicle accidents are the most common cause of blunt abdominal trauma to the kidneys in the United States. Almost all patients with renal trauma will have hematuria.

Motor vehicle accidents are the most common cause of blunt abdominal trauma to the kidneys in the United States. Almost all patients with renal trauma will have hematuria. Contrast-enhanced CT is the study of first choice and has almost completely replaced the intravenous urogram and standard cystogram.

Contrast-enhanced CT is the study of first choice and has almost completely replaced the intravenous urogram and standard cystogram. CT findings in renal trauma (Fig. 17-9):

CT findings in renal trauma (Fig. 17-9):

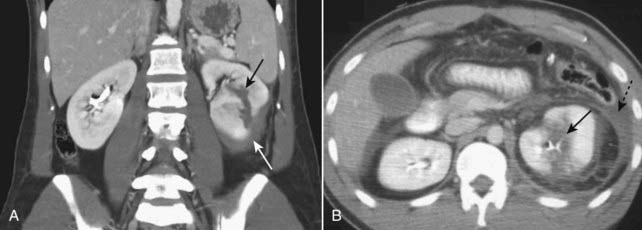

Figure 17-9 Renal trauma, two different patients.

A, Coronal-reformatted, contrast-enhanced CT scan shows a low-attenuation linear defect representing a renal laceration (solid black arrow) and a subcapsular hematoma (solid white arrow). B, Axial CT scan on another patient also shows a renal laceration (solid black arrow) and a perinephric hematoma (dotted black arrow).

Shock Bowel

Shock bowel usually occurs with blunt abdominal trauma in which there is severe hypovolemia and profound hypotension, with complete reversibility of these findings following resuscitation.

Shock bowel usually occurs with blunt abdominal trauma in which there is severe hypovolemia and profound hypotension, with complete reversibility of these findings following resuscitation. Recognizing shock bowel on CT

Recognizing shock bowel on CT

Pelvic Trauma

Rupture of the Urinary Bladder

About 70% of bladder ruptures occur with pelvic fractures, and about 10% of patients with pelvic fractures have an associated rupture of the bladder.

About 70% of bladder ruptures occur with pelvic fractures, and about 10% of patients with pelvic fractures have an associated rupture of the bladder. Bladder ruptures are best demonstrated by a CT cystogram in which contrast is infused under gravity through a Foley catheter into the bladder, but they can also be well-demonstrated by antegrade filling of the bladder from renal excretion of intravenously injected contrast.

Bladder ruptures are best demonstrated by a CT cystogram in which contrast is infused under gravity through a Foley catheter into the bladder, but they can also be well-demonstrated by antegrade filling of the bladder from renal excretion of intravenously injected contrast. There are two major types of bladder rupture (Fig. 17-12):

There are two major types of bladder rupture (Fig. 17-12):

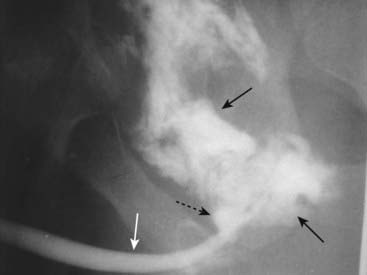

Figure 17-12 Bladder ruptures, extraperitoneal and intraperitoneal.

A, Contrast-containing urine (solid white arrows) has leaked into the extraperitoneal spaces after being instilled into a perforated bladder following pelvic fractures. Contrast, the tip of a Foley catheter, and air are seen inside of the partially filled urinary bladder (B). B, Intraperitoneal bladder ruptures are less common and may occur with blunt trauma. The contrast flows freely away from the bladder (B) up the paracolic gutters (solid white arrows) and outlines loops of bowel (dotted white arrow).

Urethral Injuries

Urethral injuries should be investigated when there are straddle fractures of the pelvis or penetrating injuries in the region of the urethra. Hematuria, blood at the urethral meatus, and inability to void are suggestive clinical findings.

Urethral injuries should be investigated when there are straddle fractures of the pelvis or penetrating injuries in the region of the urethra. Hematuria, blood at the urethral meatus, and inability to void are suggestive clinical findings. Imaging is done most often using retrograde urethrography (RUG), in which contrast is instilled retrograde at the urethral meatus with retrograde filling of the urethra. This is done before insertion of a Foley catheter into the bladder.

Imaging is done most often using retrograde urethrography (RUG), in which contrast is instilled retrograde at the urethral meatus with retrograde filling of the urethra. This is done before insertion of a Foley catheter into the bladder. The most common injury is a rupture of the posterior urethra through the urogenital diaphragm into the proximal bulbous urethra.

The most common injury is a rupture of the posterior urethra through the urogenital diaphragm into the proximal bulbous urethra. Weblink

Weblink

Registered users may obtain more information on Recognizing the Imaging Findings of Trauma on StudentConsult.com.

![]() Take-Home Points

Take-Home Points

Recognizing the Imaging Findings of Trauma

Trauma is generally divided into blunt and penetrating trauma. Most trauma-related injuries are due to blunt trauma, motor vehicle accidents contributing the majority.

CT has had a profound impact in traumatized patients by distinguishing those patients who can be managed conservatively from those who need surgical or other interventions.

Rib fractures may herald more serious internal injuries such as lacerations of the liver or spleen or pneumothoraces. Most occur in ribs 4-9.

Pulmonary contusions are the most common manifestation of blunt chest trauma and represent hemorrhage into the lung, usually at the point of impact. They classically clear in a few days.

Pulmonary lacerations are tears in the lung parenchyma that may contain fluid or air. Their presence may be hidden by a surrounding contusion, and they typically take longer than a contusion to clear.

Aortic injuries usually occur at the isthmus, require rapid recognition for optimum survival, and on contrast-enhanced CT may take the form of intimal flaps, contour abnormalities, or hematomas.

The most commonly affected solid organs in blunt abdominal trauma (in order of decreasing frequency) are the spleen, liver, kidney, and urinary bladder.

The liver is commonly injured in both blunt and penetrating trauma, and its injuries account for the majority of the deaths from abdominal trauma. It may demonstrate lacerations, hematomas, wedge-shaped defects, pseudoaneurysms, and acute hemorrhage.

Because the spleen is highly vascular, hemorrhage is the most serious sequela of splenic trauma, whose findings include hematomas, lacerations, and contusions.

Patients who have had renal trauma almost all have hematuria and may show contusions, lacerations, hematomas, or vascular pedicle injuries on CT. They may also demonstrate extraluminal contrast from an injury to the renal pelvis or ureter.

Shock bowel is a consequence of profound hypotension and shows diffuse small bowel wall thickening with enhancement of dilated and fluid-filled loops on CT.

Bladder ruptures may be either extraperitoneal (more common) or intraperitoneal, the former demonstrating extraluminal contrast surrounding the bladder, and the latter showing contrast flowing freely in the peritoneal cavity.

Urethral injuries occur almost exclusively in males, are frequently associated with pelvic fractures, and usually involve the posterior urethra where extraluminal contrast may be seen in the perineum or extraperitoneally in the pelvis.