Chapter 4 Infection

Infection

There are very many infections: the chapter will deal only with principles and a few examples.

| Type of Infecting Agent | Example | Example of Disease |

|---|---|---|

| BACTERIA (a very wide range) | STAPHYLOCOCCUS | ABSCESS |

| VIRUSES (a wide range) | HERPES ZOSTER | CHICKENPOX and SHINGLES |

| FUNGI (a limited range) | CANDIDA | BUCCAL and VAGINAL THRUSH |

| PROTOZOA | PLASMODIUM | MALARIA |

| Infestation with PARASITES WORMS and FLUKES | ECHINOCOCCUS GRANULOSIS | HYDATID DISEASE |

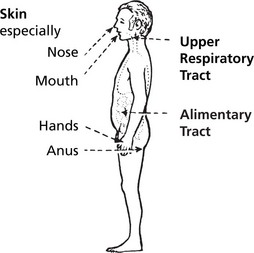

Colonisation and Commensal Growth

Vast number of bacteria normally colonise the external body surfaces (skin, alimentary and upper respiratory tracts). These commensal inhabitants usually do not harm the host. Organisms that injure the host are said to be pathogenic. If the host defences are damaged a commensal organism may cause an opportunistic infection.

Infection and Infectious Disease

infection occurs when microorganisms invade the sterile internal body tissues. (Multiplication usually follows invasion.)

An infectious disease occurs when infection is associated with clinically manifest tissue damage.

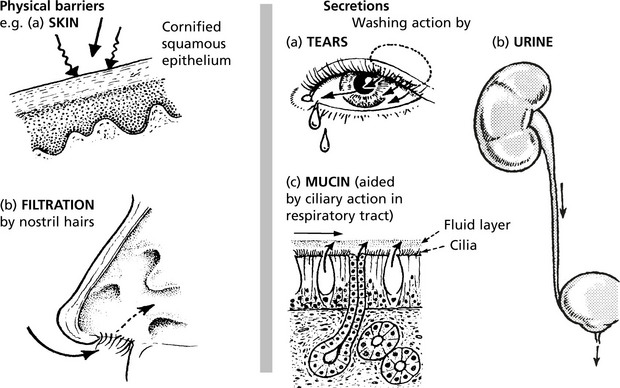

Routes of Entry of Infecting Organisms

Chemical Action

Innate Immune Response

Factors Influencing the Course of Infection

Once infection has occurred, important defence mechanisms operate:

Examples of Failure of Protective and Defence Mechanisms

Bacteria

| Exotoxins | Endotoxins |

|---|---|

| Secreted by living bacteria | Integral part of bactrial cell wall Release on death of organism (usually Gram-negative) |

| Simple proteins | Lipid-polysaccharide complexes |

| Neutralised by specific antibody (antitoxin) | Do not stimulate antibody production |

| Many actions – Enzymes, e.g. S. aureus protease – Action on intracellular signalling, e.g. V. cholerae – Neurotoxins, e.g. C. botulinum – Superantigens, e.g. S. pyogenes |

Beneficialeffects:Inlowdosestimulatesprotectiveimmunity Harmful effects: In high dose ENDOTOXIC SHOCK – due to massive release of cytokines with activation of coagulation,fibrinolytic and complement cascades LPS binds cell surface receptor CD14 and is delivered to TLR4 that starts intracellular signalling cascade |

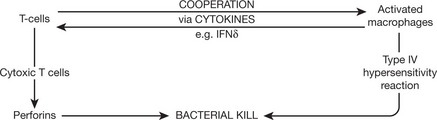

This is a form of the immune response in which reaction between the bacterial protein and sensitised lymphocytes initiates the inflammatory reaction (see p.101).

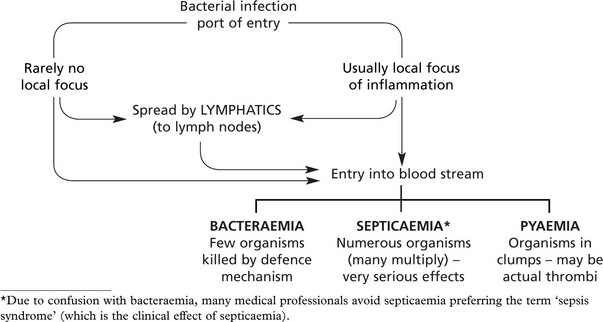

Sepsis Syndrome

Sepsis is a very serious condition in which there is a whole-body inflammatory state (systemic inflammatory response syndrome (SIRS)) in the presence of infection.

Mortality is still between 20 and 50% even with modern medical treatment. It commonly occurs in response to lipopolysaccharide (LPS) in the wall of Gram negative bacteria.

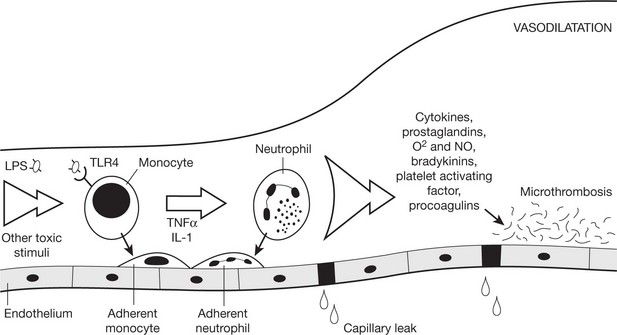

Mechanisms

LPS triggers innate immunity via TLR4. With infection disseminated via the bloodstream there is widespread activation of phagocytes.

The initial stimulus triggers production of proinflammatory cytokines, and monocytes and neutrophils adhere to endothelium. Activated macrophages, neutrophils and endothelial cells release secondary inflammatory mediators. This release of proinflammatory cytokines is known as a cytokine storm. Procoagulants produced by endothelial cells may trigger microthrombosis and if widespread this is known as disseminated intravascular coagulation.

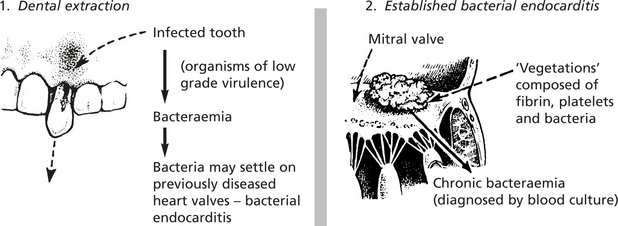

Acute Bacterial Infection

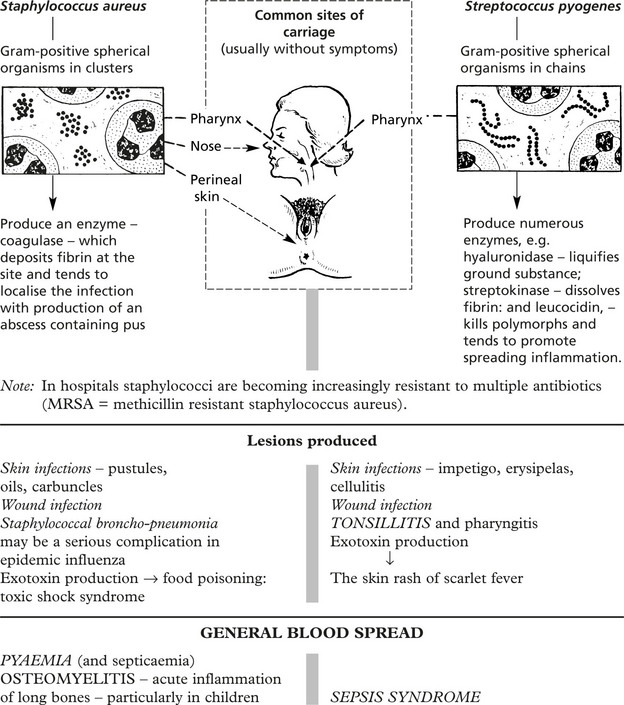

Pyogenic Bacteria

Note: Rheumatic fever and acute glomerulonephritis are complications of streptococcal infection in which the heart and kidneys are damaged. This is caused by disturbance in the immune mechanisms (type III hypersensitivity reaction) and is not due to the actual presence of streptococci in the heart and kidneys.

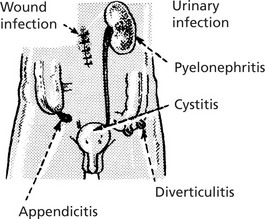

Gram-Negative Bacilli

These are usually commensals in the alimentary tract and include facultative and obligatory anaerobes.

‘Coliform’ organisms can cause local inflammation in the alimentary tract, the urinary tract and wound infections.

In addition, endotoxins liberated in the blood stream cause severe sepsis syndrome with SHOCK (p.174).

Food Poisoning

E. Coli 0157 – a commensal in cattle is a human pathogen – production of a powerful virocytotoxin is associated with the haemolytic uraemic syndrome (see p.473) and may cause death in the very young and elderly.

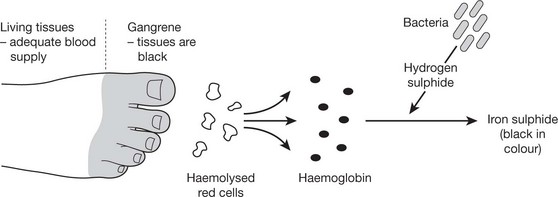

Gangrene

Gangrene is a complication of necrosis in which bacterial infection is superimposed. There are three main types:

This occurs in the toes and feet of elderly people or diabetics suffering from gradual arterial occlusion. The putrefactive process spreads slowly until it reaches the part where the blood supply is adequate. Small numbers of organisms are present.

The tissues are moist at the start of the process due to venous congestion or oedema, e.g. strangulation of viscera. The disease spreads rapidly and may be associated with sepsis syndrome. Tissue discolouration occurs by the same mechanism as dry gangrene.

Dry and wet gangrene are associated with mixed bacterial infection. Gas gangrene is caused by exotoxin producing bacteria of the clostridia group – anaerobic sporulating Gram-positive bacilli (Cl. perfringens most common). These organisms, found in soil, can enter a wound and proliferate in necrotic tissue with formation of gas bubbles. Spread is rapid with sepsis syndrome. It is a serious complication of war wounds.

Special Types of Gangrene

Necrotizing fasciitis – this infection spreads along fascial planes within subcutaneous tissue. The infection may be polymicrobial or due to a single organism, commonly group A streptococcus or, in hospitals, MRSA.

Fournier’s gangrene – this is a form of necrotizing fasciitis affecting the male genitals particularly in diabetics.

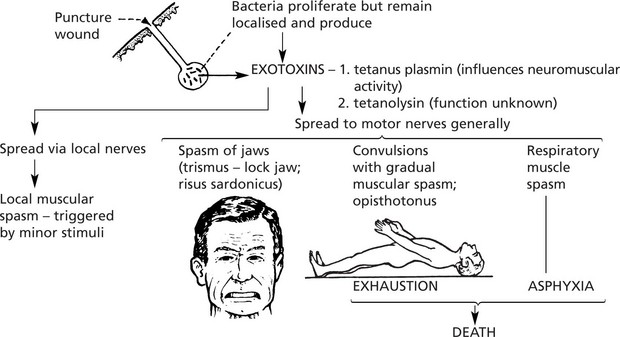

Tetanus

This organism itself does not cause local tissue damage. The effects are due to a powerful endotoxin secreted by the organism. This is in contrast to the usual bacterial diseases where tissue damage is important and is due to the local bacterial action.

The infecting organism, Clostridium tetani, a strict anaerobe, is a Gram-positive rod. Often the presence of a terminal spore gives a characteristic drum-stick appearance. The highly resistant spores are widespread in the environment due to contamination by animal faeces.

Method of Infection

Contamination of wounds in which there are anaerobic conditions, e.g. deep-penetrating wounds and wounds with severe soft tissue damage (road traffic accidents and battle casualties); only very occasionally trivial thorn punctures.

In developing communities the umbilical stump of the newborn may be infected by faecal material.

Effects

The exotoxin is highly potent and causes paroxysmal muscular spasm which becomes progressively more severe and was fatal in many cases: modern therapy including muscle relaxation and ventilation has improved the prognosis dramatically.

Chronic Bacterial Infection (Granulomas)

In these infections chronic inflammation is the basic mechanism (see p.42). The detailed evolution of the inflammatory reaction is modified by several factors of which the immune response of the host is important (see p.89).

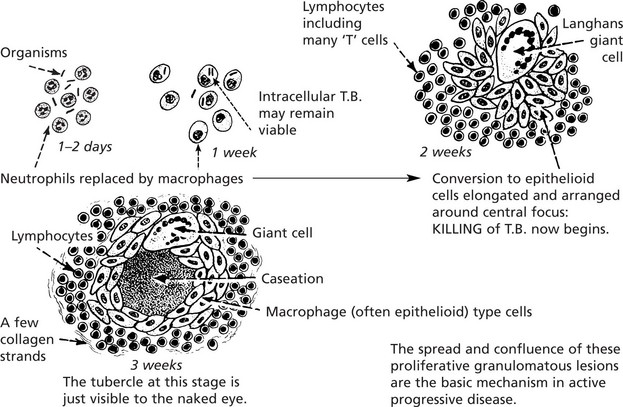

Tuberculosis

Tuberculosis is caused by the Mycobacterium tuberculosis (tubercle bacillus: TB), an organism which has a resistant waxy component in its structure and is acid and alcohol-fast (i.e. resists bleaching with strong acid and alcohol after being stained red with fuchsin). The disease rapidly declined in Western Europe and North America after World War II due to (a) improved nutrition and hygiene, (b) BCG immunisation and (c) chemotherapy (note: drug resistance is becoming an increasing problem). Patients with AIDS are at particular risk: other ‘at risk’ groups are the elderly, the immunosuppressed and alcoholics. The disease remains prevalent in developing countries.

The Tuberculous Follicle (Tubercle)

The evolution of the tuberculous follicle is a good example of the role of cellular immunity (p.92)

The caseation is the result of the combined effects of (a) the type IV hypersensitivity reaction, (b) bacterial activity and (c) ischaemia.

Other Mycobacterial Infections

Mycobacteria other than tubercle sometimes infect humans. They are commonly present in soil and water and are less virulent than M. tuberculosis. Most exposures do not produce disease unless there is a defect in local or systemic host defenses.

M. avium and M. intracellulare – these are closely related and are often grouped together as M. avium-intracellulare (MAI) – they may cause pneumonia, lymphadenitis or disseminated disease in immunosuppressed patients.

M. kansasii – this may cause a chronic cervical lymphadenitis with cutaneous fistulas and scarring in children.

M. marinum – this can cause a cutaneous granulomatous ulcerating lesion which can be contracted from contaminated swimming pools or from cleaning an aquarium (swimming pool granuloma).

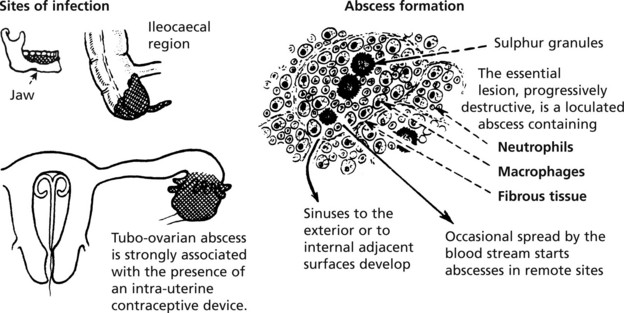

Actinomycosis

Actinomycosis is a localised but gradually spreading chronic suppuration affecting the lower jaw, the ileocaecal region of the bowel, the female genital tract and occasionally the lung.

The organism – Actinomyces israelii – widespread in nature, is a Gram-positive, branching, filamentous anaerobe found around the teeth and in the pharyngeal crypts. In the tissues, it forms yellow, densely felted together spherical colonies just visible to the naked eye: the pus is seen to contain ‘sulphur granules’.

Leprosy

This slowly progressive disease which causes serious effects by damage to peripheral nerves is still widespread in the tropics and subtropics. The infection is acquired by close, prolonged contact and is due to Mycobacterium leprae, a slender acid and alcohol-fast bacillus. The disease presents in two contrasting extreme forms and with cases of intermediate type.

These differences are due in the main to differences in the immune reaction of the host.

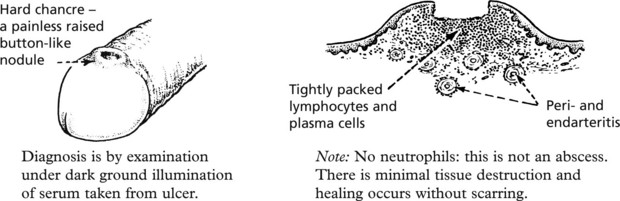

Syphilis

This is a sexually transmitted disease caused by a spirochaete (Treponema pallidum). It has a close set spiral structure that can be demonstrated by dark ground illumination, silver staining of immunofluoresence. The incidence of syphilis declined until the late 1990s but there has been a marked increase in cases since 2001 particularly in homosexual males.

Primary Syphilis

During the first three weeks after infection, the spirochaetes spread in the blood throughout the body without any noticeable effects. Then the primary lesion – hard chancre – appears at the original site of entry.

The INGUINAL LYMPH NODES present clinically as painless, firm swellings due to proliferation of lymphocytes and plasma cells.

Secondary Syphilis

During the next 2 or 3 months, the spread of the organisms throughout the body causes secondary stage effects. These are a widespread rash (pox) of varying appearance, ulceration of mucous membranes, generalised lymphadenopathy, damage to various individual organs and tissues. There are constitutional effects – particularly fever and anaemia.

The essential pathology is the presence of very numerous spirochaetes accompanied by focal infiltration of lymphocytes, plasma cells and macrophages with mild arteritis. Infectivity is very high. Tissue destruction is minimal and healing occurs without scarring. A latent stage of long duration is followed in 35% of cases by tertiary syphilis.

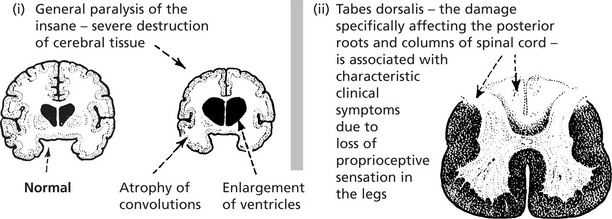

Tertiary (Late) Syphilis

The lesions, which may occur at any time for many years after the healing of the secondary phase, offer striking contrasts. This stage is characterised mainly by local destructive lesions, the result of cellular immunity (T cells) causing necrosis of tissue. The main forms are:

1. Gumma, 2. Syphilitic aortitis and 3. Neurological syphilis.

This is a localised area of necrosis which may affect large parts of any organ or tissue but particularly bones, testis and liver.

The arch and thoracic aorta is damaged with weakening of the media: this leads to aneurysm formation (see p.231) which causes serious local pressure effects and may also rupture with severe haemorrhage.

Congenital Syphilis

Transplacental infection of the fetus occurs with the following possible consequences:

Diagnosis of Syphilis

In primary syphilis and early secondary syphilis organisms may be detected in smears from lesions by dark-ground microscopy.

The Venereal Diseases Reference Laboratory (VDRL) and rapid plasma reagin (RPR) test both detect non-specific antibodies in the blood of patients that may indicate that the patient has syphilis. They do not detect antibodies to the bacterium but rather against substances released by cells when they are damaged by T. pallidum. False positives can occur.

Virus Infections

Virus Infections

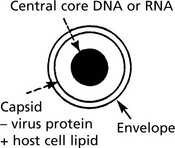

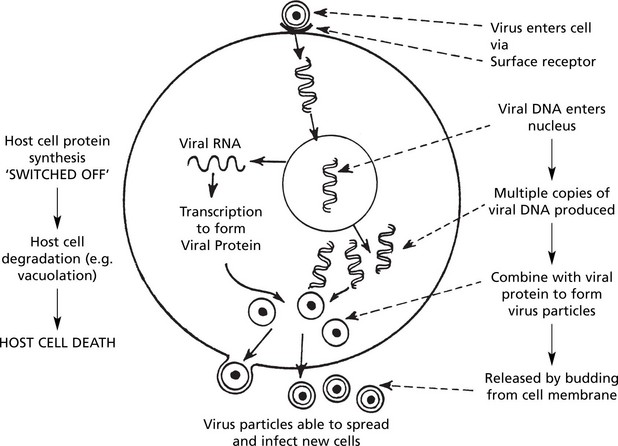

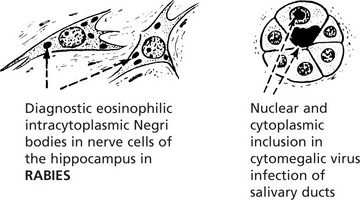

Viruses are obligate intracellular pathogens that can replicate only by utilising the resources of the infected cell. The virus particle, or virion, consists of a central core of genetic material, either RNA or DNA, surrounded by a protein coat (capsid). In addition there may be a membranous envelope containing host and viral lipids.

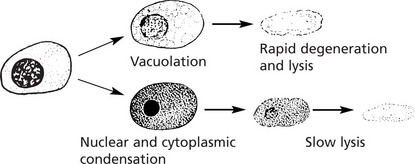

The diagram shows DNA virus using the host cell for replication: at the same time causing cell death.

In addition to this direct cytopathic effect of the virus, damage to host may also be caused by:

Retroviruses

An important variation occurs in a small group of RNA viruses. These contain an enzyme – reverse transcriptase – which, within the cell cytoplasm, is able (using the virus RNA as the template) to synthesise virus DNA which is then incorporated into the nuclear genetic material (note that messenger RNA is not required).

The virus DNA may remain there inactive for long periods. When activity is resumed, replication and cytopathic changes are effected as indicated in the diagram.

Retroviruses are important agents in carcinogenesis and AIDS (see p.105).

Acute Virus Infection

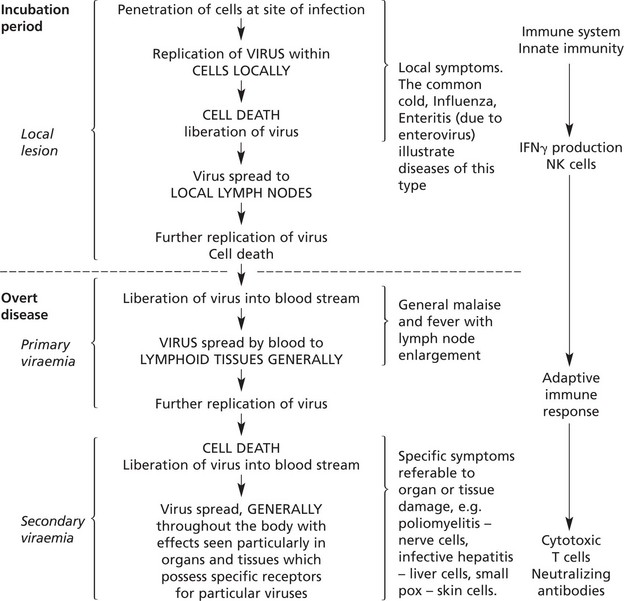

The evolution of a typical acute virus infection can be understood in terms of virus replication, release and spread within the body, and of the host’s reaction.

Typical Evolution

This typical evolution is produced by successive waves of virus. However, the great majority of virus infections are clinically latent or mild because virus replication and spread are prevented by the body’s defence mechanisms. Severe overt disease occurs when there is a specially virulent virus or when the body’s resistance is inadequate, especially in a primary infection.

Not all virus infections cause disease in this way, 2 important variations are:

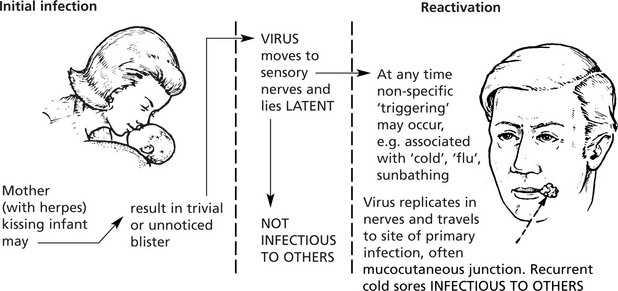

Latent Virus Infection

A good example is the common ‘cold sores’ of the lips and face caused by the virus Herpes simplex (an enveloped DNA virus).

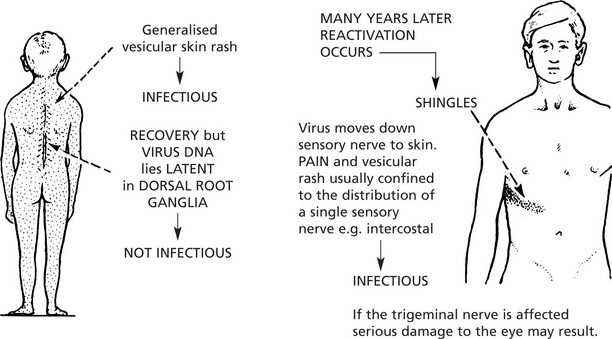

Another example is herpes zoster (shingles).

This is a painful affection of segmental sensory nerves and root ganglia due to infection by chicken pox virus Varicella.

Oncogenic Virus Infection

Several DNA viruses and retroviruses of the RNA family can give rise to tumours (see also p.150).

Examples include the following:

The mechanisms by which viruses cause tumours are illustrated on page 150.

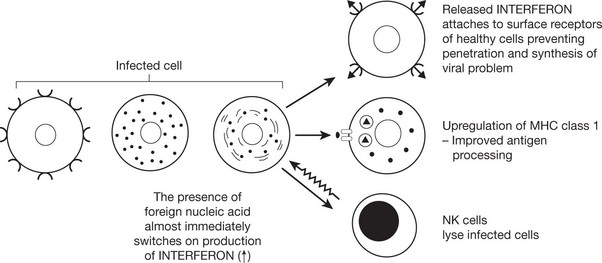

Host/Virus Interaction

The reactions occurring in the host are important.

The vascular and exudative elements follow the usual pattern; neutrophils are not a feature unless there is considerable tissue necrosis or secondary bacterial infection. However, macrophage phagocytic activity is important in the defence against viral infection. There is often a relative lymphocytosis.

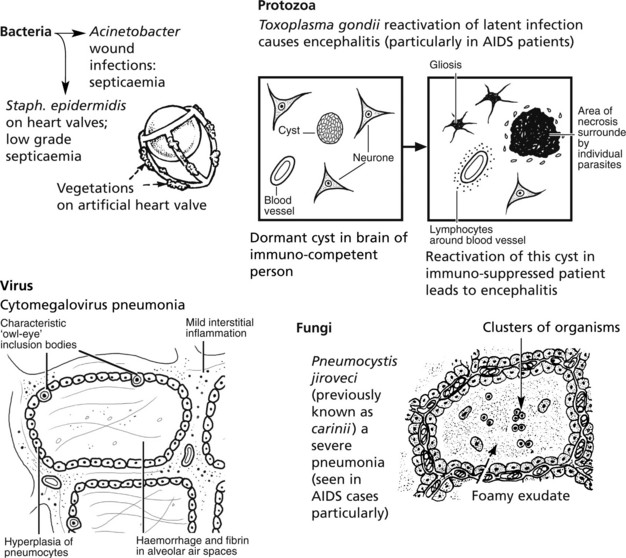

Opportunistic Infections

This term is used for infections caused by organisms which are often nonpathogenic or of low grade virulence, occurring in individuals whose resistance to infection is impaired. They are occurring more frequently in modern medical practice because of the increasing use of powerful immunosuppressive drugs.

Causes of Lowered Resistance

Infection – General Effects

The more general body reactions in infection are: fever and changes in metabolism.

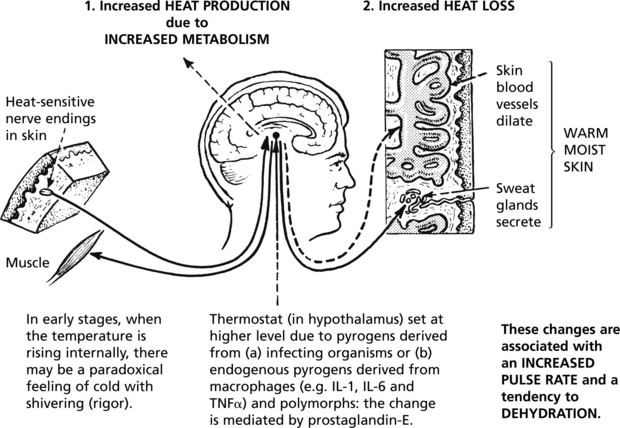

Fever (Pyrexia)

The body temperature rises above normal initially due partly to an imbalance between heat production and loss, but mainly due to a resetting at a higher level of the ‘thermostat’ mechanism in the hypothalamus. This results in:

Pyrexia also occurs when there is:

Hyperpyrexia (when the temperature exceeds 41 °C (106 °F)) is extremely dangerous because of damage to the nerve cells in the brain.

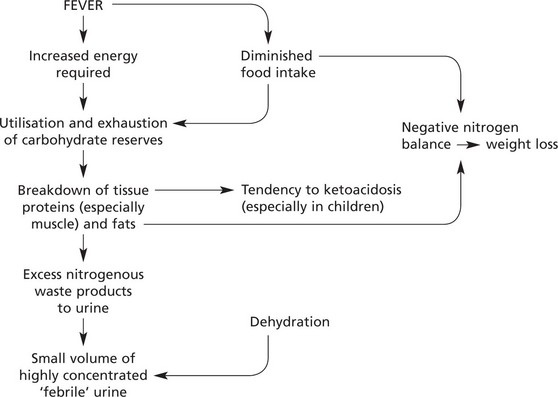

Changes in Metabolism

Tissue breakdown is greatly increased, and in some infectious fevers there is a marked loss of body weight.

limit initial infection via antibody-dependent cell-mediated cytotoxicity (ADCC) but are very important in protecting against

limit initial infection via antibody-dependent cell-mediated cytotoxicity (ADCC) but are very important in protecting against