Chapter 8 Respiratory System

Upper Respiratory Tract

Acute Inflammation

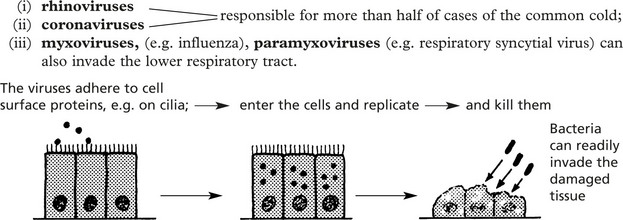

Infections of the nose, nasal sinuses, pharynx and larynx are common. They are usually mild and self-limiting. Most cases are due to viral infection, but this is often followed by bacterial superinfection.

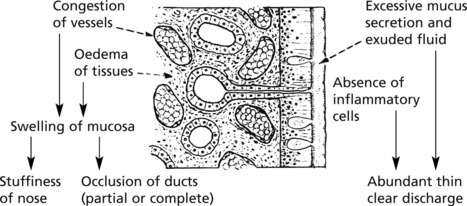

This phase is characterised by features of acute inflammation but without the exudation of neutrophils.

The wide variety of different viruses involved prevents protective immunity.

Rhinitis

Common Cold (Acute Coryza)

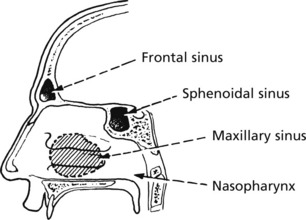

This common respiratory inflammation usually involves the nose and adjacent structures.

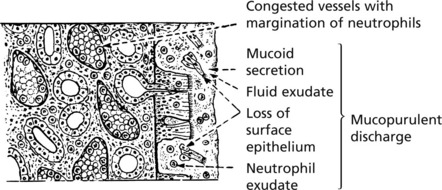

The 2 phases, viral and bacterial, are typically seen in this disease.

The drainage from the sinuses, especially the maxillary, is often blocked by swelling of the mucosa — giving rise to sinusitis.

The infection is acquired by droplet spread of viruses by sneezing.

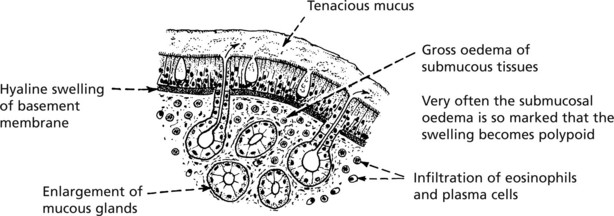

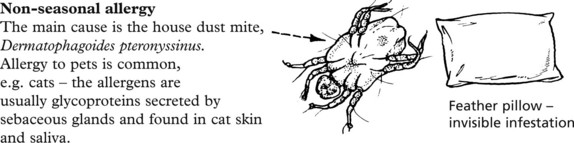

Allergic Rhinitis ‘Hay Fever’

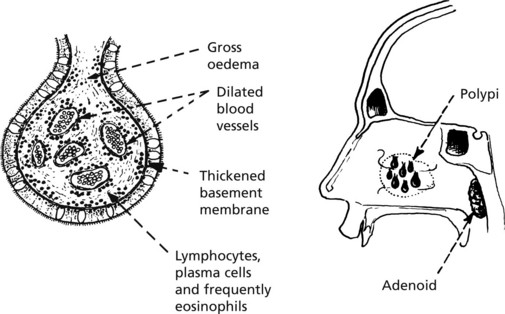

An allergic (immediate type hyper-sensitivity) type of inflammation (2. p.101) is often seen. Patients develop immediate symptoms of sneezing, itching and watery rhinorrhoea.

The repeated attacks frequently lead to chronic changes in the mucosa with polyp formation.

Nasal Polyps

These form particularly on the middle turbinate bones and within the maxillary sinuses.

In the nasopharynx, the lymphoid tissue may be greatly enlarged (adenoids) and contribute to the nasal obstruction.

Vasomotor Rhinitis

This is a clinical diagnosis. The pathological changes are, to some extent, similar to those of allergic rhinitis, but the condition is more continuous, less spasmodic. Although the cause is unknown, viral infections in a polluted atmosphere (usually an urban setting) are thought to initiate the ‘sensitivity’ and non-specific stimuli such as bright light and smells precipitate an attack.

Acute Pharyngitis, Tracheitis and Laryngitis

Acute Pharyngitis and Tracheitis

Most sore throats are caused by viruses – including adenovirus and Epstein–Barr virus.

Bacteria include Streptococcus pyogenes, Haemophilus parainfluenzae and Corynbacterium diphtheriae.

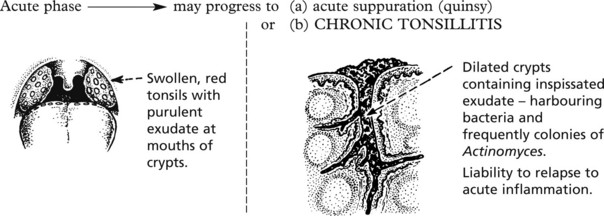

Tonsillitis is a common acute inflammation, historically due to streptococcal infection but, with the introduction of antibiotics, viruses are the initiating infective agents in most cases.

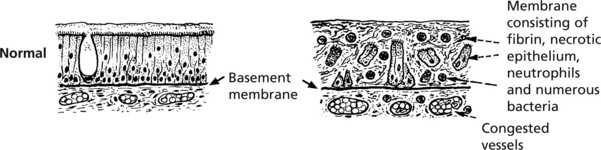

Diphtheria, now uncommon in countries where vaccination is widespread, is a serious infection.

The formation of a pseudomembrane is striking.

This pseudomembrane may spread to block the larynx, causing respiratory obstruction.

The exotoxin of diphtheria is encoded by a bacteriophage (a virus which infects the bacterium). It can cause myocarditis (p.212) and neuropathy (p.569).

In Acute epiglottitis, typically due to Haemophilus influenzae, there is severe inflammation and oedema. In young children, the larynx becomes obstructed necessitating tracheostomy and administration of antibiotics.

Acute laryngitis is often due to parainfluenza viruses. Acute oedema of the glottis is seen in some cases of anaphylaxis (p.101) and angioneurotic oedema.

Other Disorders of the Larynx

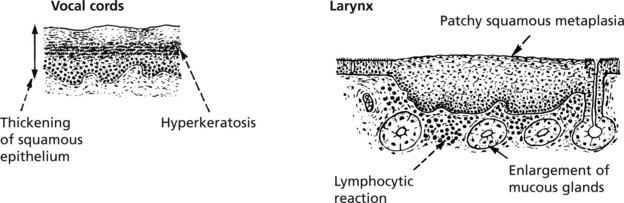

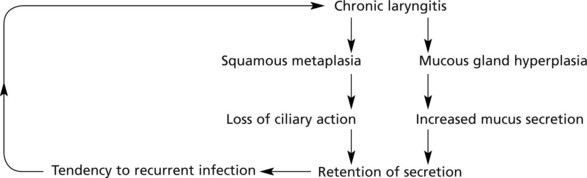

Chronic Laryngitis

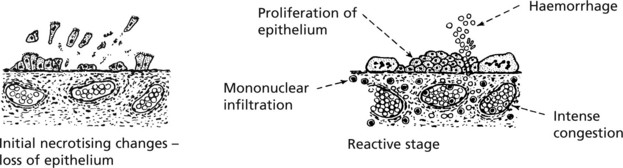

Cigarette smoking, repeated attacks of infection and atmospheric pollution may lead to chronic inflammation of the larynx.

Two main features are (a) changes in the lining epithelium and (b) increase in mucus secretion.

The following sequence of events tends to take place:

Tuberculosis – this can cause severe ulceration of the larynx and is usually secondary to pulmonary tuberculosis.

Tumours of the Upper Respiratory Tract

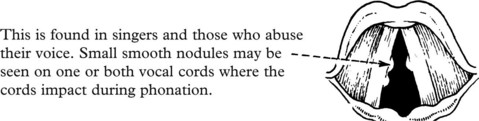

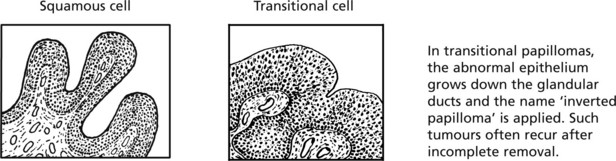

Benign Tumours

Malignant Tumours

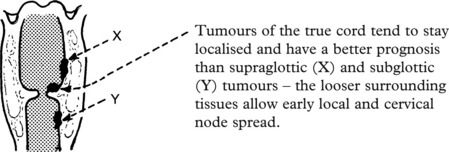

These are mainly squamous carcinomas and are commonly seen in the larynx. Intraepithelial neoplasia (carcinoma-in-situ) is a frequent precursor.

Smoking and alcohol consumption are aetiologically important. The rate of growth and spread is influenced by the site within the larynx.

Nasopharyngeal carcinoma is common in Eastern countries and is associated with Epstein–Barr virus infection.

Adenocarcinoma of the nose is a rare tumour, sometimes seen in woodworkers.

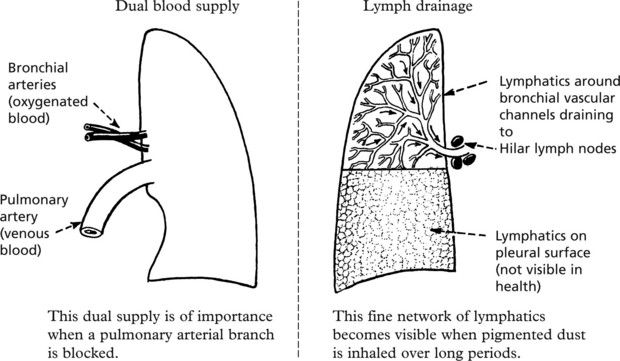

Lungs – Anatomy

Acinus

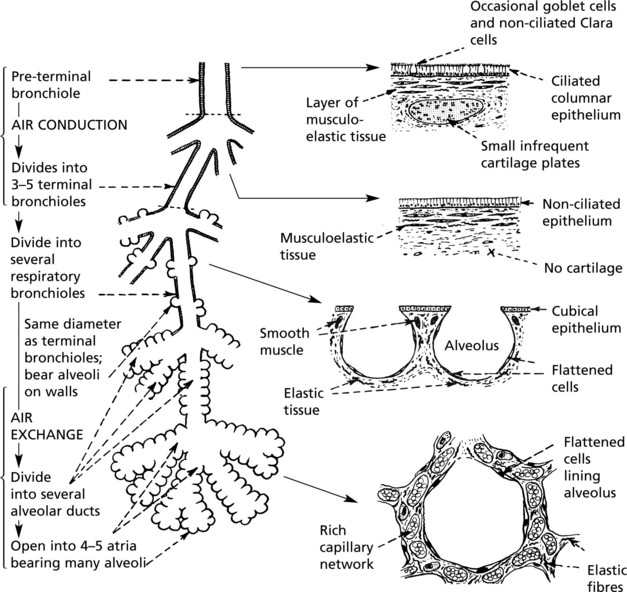

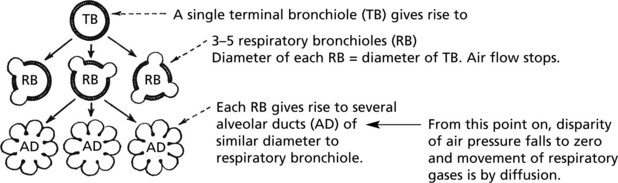

This is the functional unit of the lung, where gas transfer takes place. It consists of the respiratory bronchiole and associated alveolar ducts and sacs supplied by one terminal bronchiole. There are approximately 25 000 acini in the normal adult male lung.

Lobule

This is served by one preterminal bronchiole and is the smallest anatomic compartment of lung that is grossly apparent. It contains 3 to 30 acini and is bound by connective tissue septa. These connective tissue septa may be accentuated in smokers.

The total area for air exchange is very large (equivalent to a tennis court) allowing considerable reserve capacity.

Respiration

The normal intake of air is around 7 litres per minute; of this, after allowing for nonfunctioning dead space (trachea, bronchi, etc.), approximately 5 litres per minute are available for alveolar ventilation. A definite flow of air is maintained as far as the terminal bronchiole. Beyond this point the actual flow ceases and gas exchange is effected by diffusion.

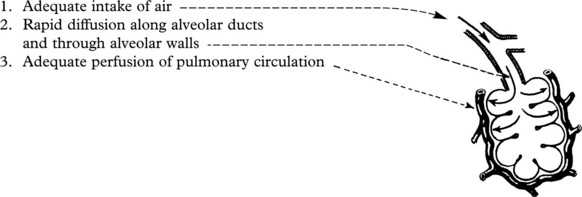

Three factors are involved in the maintenance of adequate respiration:

Interference with any of these factors will result in respiratory embarrassment (dyspnoea) and even respiratory failure.

Inadequate Air Supply to Alveoli (Hypoventilation)

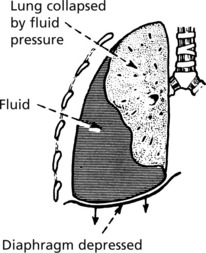

This may be due to lesions and diseases which interfere with the mechanics of respiration, such as central nervous lesions affecting the respiratory centre, paralysis of muscles of respiration as in poliomyelitis, injuries and deformities of the thoracic skeleton (e.g. fracture of ribs, kyphosis) and pleural disease preventing lung expansion as in pleural effusion or pneumothorax.

The most common cause of hypoventilation is bronchial obstruction. This may be reversible due to bronchial spasm as in asthma or irreversible in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (p.258).

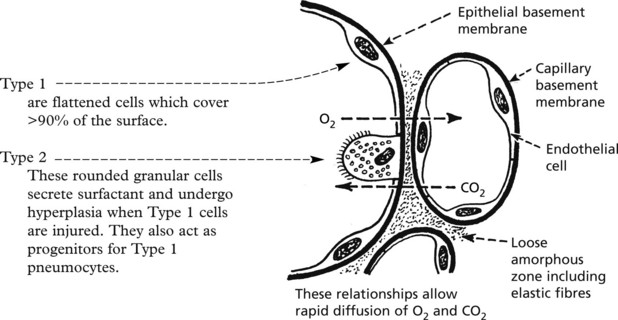

Impaired Diffusion of Gases

Three mechanisms may interfere with diffusion:

Altered Pulmonary Perfusion

Interference with the pulmonary circulation may occur in 4 main ways:

Note: In addition to hypoxaemia, inadequate perfusion tends to cause retention of carbon dioxide.

In chronic lung disease, ventilation, diffusion and perfusion disorders are present in varying degrees.

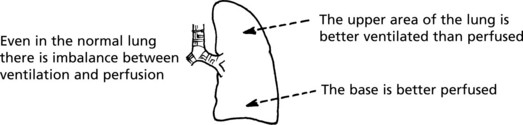

In many lung diseases this imbalance is increased. Admixture of well and poorly oxygenated blood results in hypoxaemia.

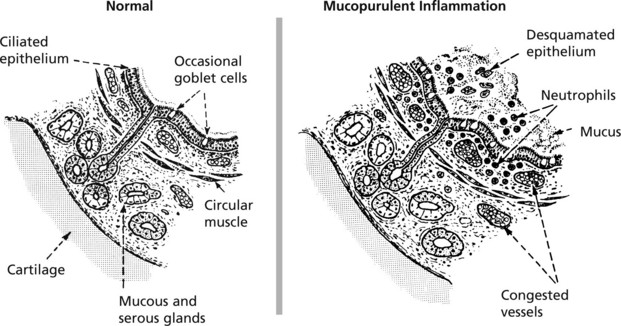

Acute Bronchitis

This is an inflammation of the large and medium bronchi. The condition may be serious if associated with pre-existing respiratory disease. Mucous and serous glands in the walls of the bronchi provide abundant mucoid secretion during the inflammation. Ciliated epithelia lining the bronchi aid passage of the exudate upward and help prevent spread down to the bronchioles.

In most cases, the process is initiated by a viral or mycoplasmal infection. It is a common complication of influenza and measles. This initial phase is followed by bacterial invasion. Streptococcus pneumoniae and Haemophilus influenzae are commonest, but Staphylococcus aureus and Streptococcus pyogenes may be found, especially in infants.

The condition is usually mild, and spread to the bronchioles is unusual in healthy adults due to the effective ciliary action of the bronchial epithelium. Spread may occur however in debilitated people. Bronchiolitis and bronchopneumonia result and can prove fatal. Equally important is the serious effect of repeated attacks of acute infection in patients with chronic bronchitis (p.258).

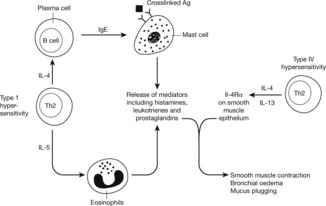

Bronchial Asthma

In asthma, there are spasmodic attacks of reversible bronchial obstruction with wheezing and dyspnoea and often a dry cough. The prevalence has markedly increased in recent years, although has now plateaued. There are 2 main patterns:

Other varieties include occupational asthma and aspirin-induced asthma.

The basic mechanism is as follows:

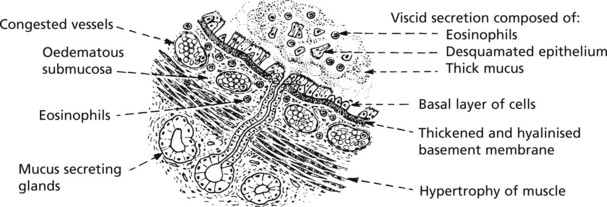

The histological changes are a combination of allergic reaction and muscular hypertrophy, the result of prolonged spasm.

Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease (COPD)

This term describes three entities that show considerable clinical overlap:

COPD is common and is the fourth leading cause of death worldwide.

Aetiology The main factors are:

Chronic Bronchitis

The clinical definition is based on the presence of a productive cough lasting at least 3 months and occurring annually for at least 2 years.

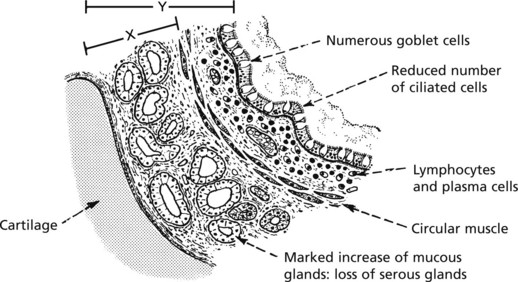

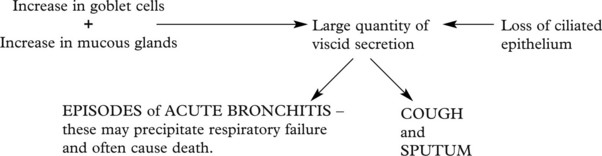

Pathologically the following changes are seen:

The increase in thickness of the mucous gland layer is striking: at post-mortem the Reid index is measured – i.e. the ratio of the submucous layer (X) to the whole thickness (Y): a value greater than 1:2 is significant.

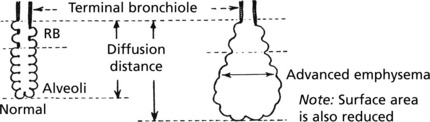

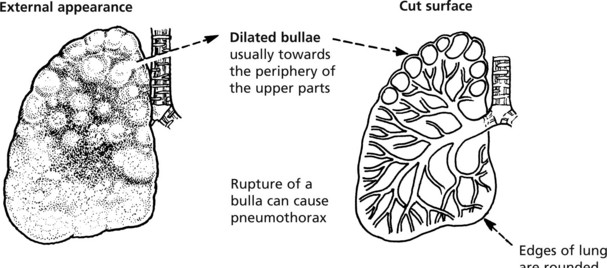

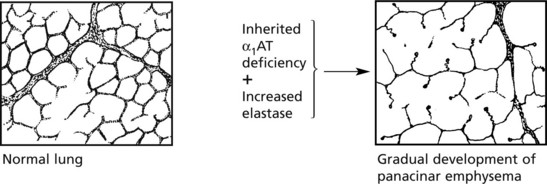

Emphysema

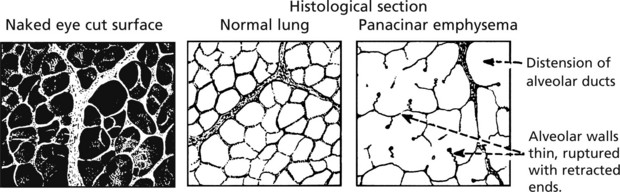

This is defined as a permanent dilatation of air spaces distal to the terminal bronchiole due to destruction of their walls without fibrosis. It is an important component of COPD (p.258) and has the same aetiological factors.

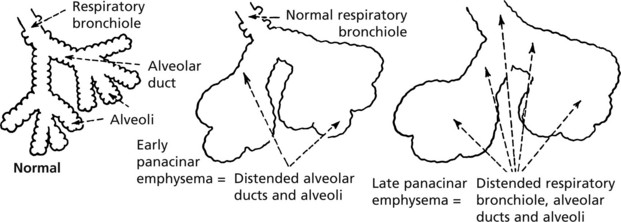

Panacinar Emphysema

The enlarged air spaces are distributed across the entire acinus.

Special stains show loss of elastic tissue. The capillaries are stretched and thinned. The reduction in blood supply is probably a factor in leading to rupture of alveoli.

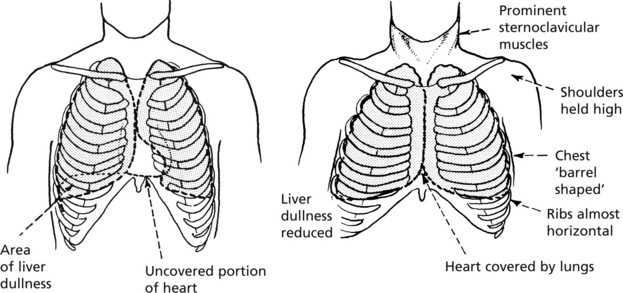

There is little evidence of bronchiolitis. The voluminous lungs produce characteristic radiological changes. The distension eventually spreads to involve the respiratory bronchiole, i.e. the whole acinus is affected – panacinar emphysema.

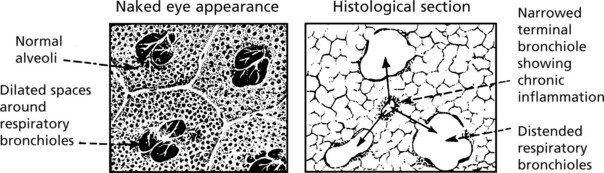

Centrilobular Emphysema

In this form the dilated air spaces immediately surround and involve the respiratory bronchioles.

Chronic inflammation of the respiratory bronchioles is an important feature: eventually, in many cases, the distension extends to produce panacinar emphysema.

Pathogenesis

In emphysema alveolar destruction is the result of several processes:

Alterations in Toll like receptor 4 may result in persistent low grade activation of the innate immune system and destruction of lung tissue.

Cigarette smoke upregulates genes involved cellular senescence and affected cells may undergo apoptosis.

Emphysema is an important component of lung damage due to dust inhalation (pneumoconiosis) (see p.272).

Functional Effects of Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease (COPD)

Patients with COPD tend to fall into 2 groups depending on whether or not they tolerate hypoxia.

Eventually many patients develop severe chronic respiratory failure and may die during an acute episode of bronchitis.

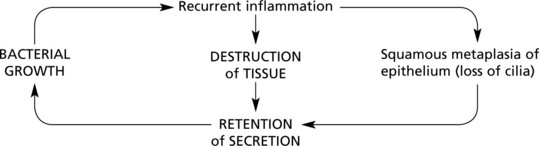

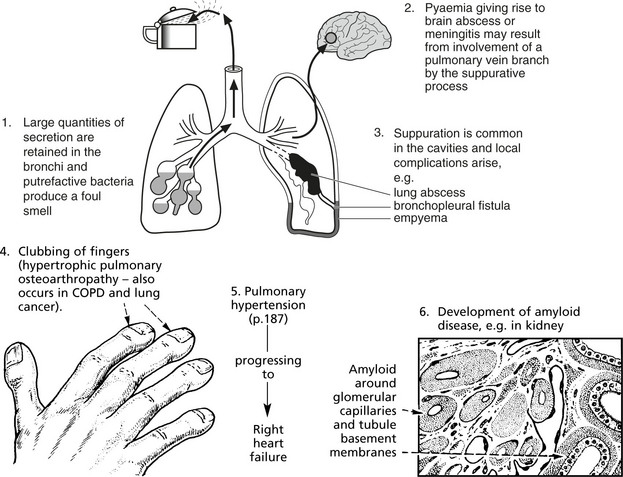

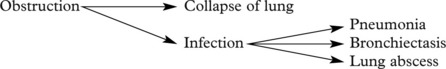

Bronchiectasis

Bronchiectasis means a permanent dilatation of one or more bronchi. There are 2 main subdivisions

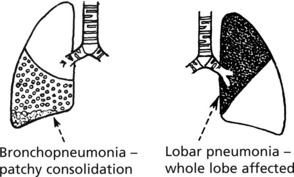

Pneumonia – Bronchopneumonia

Pneumonia is an inflammatory process involving the alveolar tissue of the lungs. It is discussed under 3 main headings:

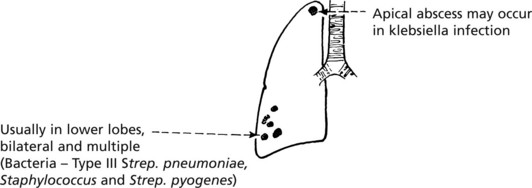

Bronchopneumonia caused by a variety of bacteria is the commonest form. It may affect all ages, but it is particularly frequent in 4 circumstances:

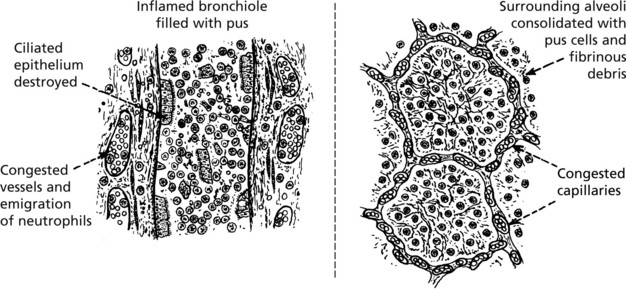

Bronchopneumonia is primarily an inflammation spreading from terminal bronchioles to their related alveoli.

The lesions are initially focal, involving one or more lobules.

First red, then grey, they show a central bronchiole containing pus.

Lobar Pneumonia

As the name suggests, a complete lobe or even two lobes of a lung are affected, the most striking changes occurring in the alveoli. The disease is now rare in Western countries. It is seen typically in adults aged 20–50 years with males predominating and is caused by Streptococcus pneumoniae. Occasionally Klebsiella pneumoniae is the agent in the debilitated elderly, diabetics and alcoholics.

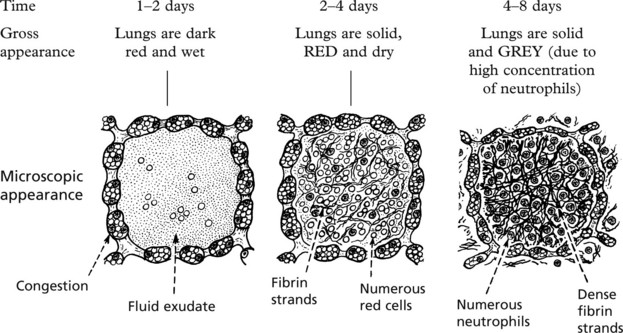

The whole affected lobe progresses uniformly through 4 distinct phases illustrating the classic progression of an acute inflammation: this has been so radically altered by antibiotic treatment that the following description is to some extent historical.

Clinically, the onset is acute with fever and often rigors. There is a dry cough and rusty sputum; dyspnoea and often chest pain due to pleurisy.

The Pathology is described in 4 phases merging sequentially: all the alveoli in the lobe are uniformly affected.

Legionnaire’s Disease

Previously confused with pneumococcal pneumonia, Legionnaire’s disease occurs in small epidemics, is more common in males and is due to a tiny Gram-negative bacillus – Legionella pneumophila. The death rate can be high – up to 20%. Infection is associated with inhalation of aerosol from contaminated water storage systems.

Viral Pneumonias

Influenza

In most cases, influenzal infection is confined to the upper respiratory tract, but in debilitated persons and during epidemics, the whole respiratory tract is affected.

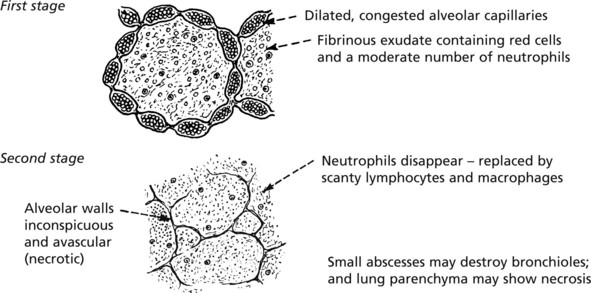

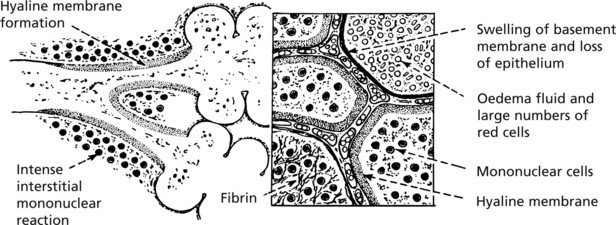

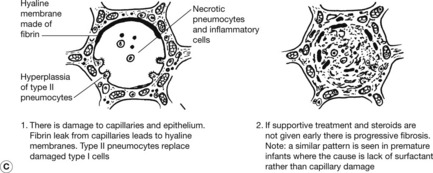

Pneumonia Changes

The lungs are bulky, purple red and exude blood-stained froth when cut. The microscopic changes vary from one part to another.

Infective Agents

Of the three main types A, B and C, type A is the most virulent, and mutants of this type are responsible for most epidemics and the fatalities which occur. The 2009 pandemic was due to a swine influenza of type A known as H1N1. Severe disease and death was more common in children and pregnant women.

Secondary infection is common, the bacteria most frequently involved being Staphylococcus aureus, Haemophilus influenzae and Streptococcus pneumoniae.

Atypical Pneumonias

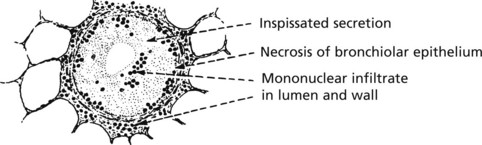

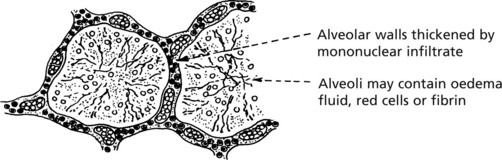

There are a number of pneumonic conditions due to viruses and bacteria in which a common pattern of pathological change is observed.

The lining epithelial cells of bronchioles and alveoli are stimulated by the presence of the virus.

Variations in the basic pattern occur in different infections. Confluent consolidation is often found in psittacosis and ornithosis (excreted by infected birds) and in measles giant cell pneumonia. Interstitial pneumonia is produced by cytomegalovirus and in rickettsial infections such as Q fever and ‘scrub typhus’. In mycoplasma pneumonia, inflammation spreads from the bronchioles into the lung parenchyma and may become chronic with fibrosis.

Pneumonia – Special Types

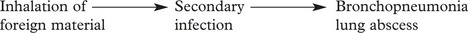

Aspiration Pneumonia

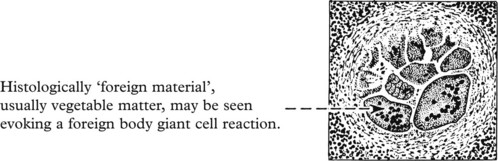

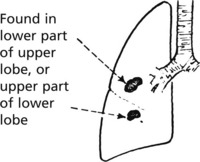

This is due to inhalation of food or infected material from the mouth or pharynx. It may occur during anaesthesia or coma or may complicate conditions associated with frequent regurgitation, e.g. oesophageal obstruction, pyloric stenosis or poor swallowing due to stroke or motor neurone disease.

In adult cases the inhalation of acid gastric contents may cause an initial shock reaction: in other cases the onset is insidious.

Possible progression is as follows:

Lipid Pneumonia

Lung Abscess

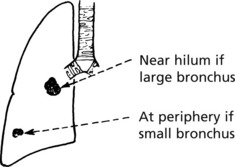

This is now an uncommon condition due to prompt treatment of preceding infection. The usual causes are:

Rarer causes of abscess are: pyaemia, trauma to lung, extension from suppuration in mediastinum, spinal column or subphrenic region, and infection with Entamoeba histolytica.

Tuberculosis (TB)

The lungs are more commonly affected by TB than any other organ. The incidence of TB in developed countries is rising, partly due to AIDS. Drug resistant strains of Mycobacteria are an increasing problem.

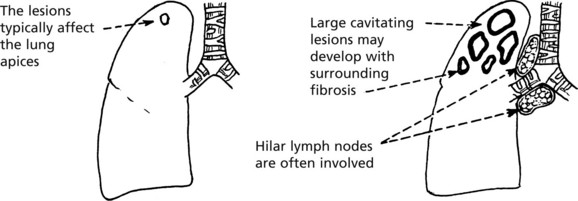

There are 2 patterns of pulmonary tuberculosis — primary and secondary.

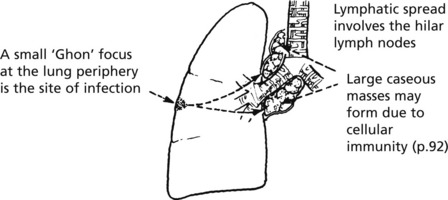

Primary Infection

This occurs in patients, usually children, who have not been previously exposed to TB or vaccinated against it.

The COMBINATION of Ghon focus + hilar nodes is termed the primary complex.

In most patients, the lesions undergo fibrosis or calcification and heal. Spread can, however, occur.

Spread of Tuberculosis

Spread of Tuberculosis

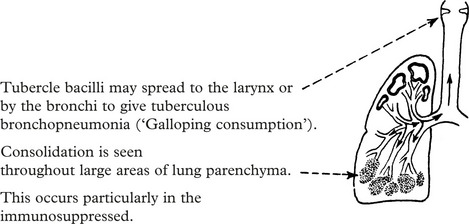

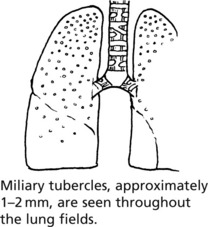

This is typically seen in secondary TB, but may also complicate primary infection.

The infection can spread by several pathways.

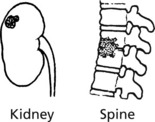

This may lead to isolated blood borne infection e.g. tuberculous meningitis (p.551), renal TB and bone TB, e.g. Pott’s disease of the spine: or to miliary spread throughout the body.

In this, miliary spread occurs throughout the lung fields alone.

The clinical course of tuberculosis is variable and depends on the immune status of the individual, the response of the bacteria to drugs, and intercurrent disease.

The histological features are as described on page 72.

Pneumoconioses (Dust Diseases)

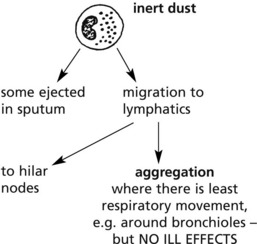

The reaction to inhaled dust varies very considerably. Some dusts, e.g. pure carbon, are inert: others, e.g. silicates, cause severe lung disease.

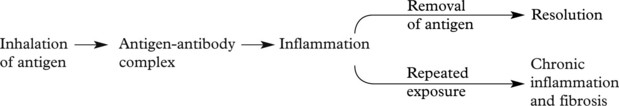

Basic Pathology

The basic pathology is a Type III hypersensitivity reaction (p. 102) and the term hypersensitivity pneumonitis (Extrinsic allergic alveolitis) is used.

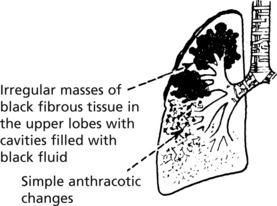

Anthracosis

Pure carbon is biologically inert and is deposited as in (a) above with no ill effects. Damage to the lung seen in coal-miners and in populations exposed to carbon polluted atmosphere is potentiated by the content of silicates and other pollutants.

Coal-Miner’s Pneumoconiosis

The cause is unknown, theories include tuberculous infection as an initiator dust dose and composition, genetic factors and deviant immune responses.

The severe diseases caused by inorganic dust inhalation, usually occupationally, are described.

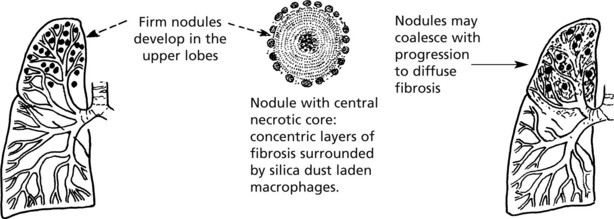

Silicosis

The lung lesions are slowly progressive over many years. Silicates are particularly damaging to lung macrophages (see p. 272).

Patients develop increasing breathlessness and may die of respiratory failure and cor pulmonale.

The silicotic lung is particularly susceptible to tuberculosis (which may be due to the effects of silica on pulmonary macrophages). Historically, this was an important cause of death.

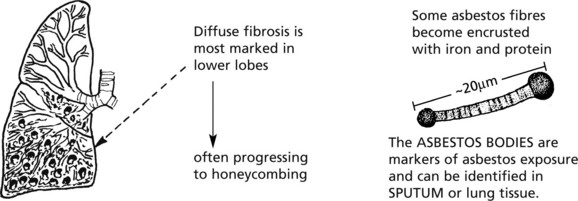

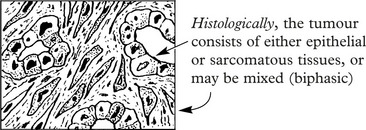

Asbestosis

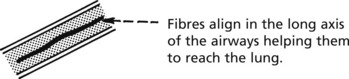

Asbestos is the generic name for a group of fibrous silicates widely used in heavy industry for insulation (particularly in shipbuilding).

There are two distinct forms of asbestos – serpentine (curly and flexible) and amphibole (straight and stiff). Amphibole fibres (crocidolite and amosite) are more pathogenic than serpentine fibres (principally chrysotile).

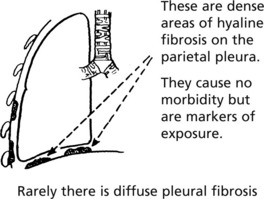

Asbestosis results from chronic exposure.

Other important complications are:

Asbestos workers have an increased risk of lung cancer, especially if they also smoke. Risk of cancer = risk due to smoking × risk due to asbestos.

Note: There are usually significantly fewer asbestos fibres/bodies in mesothelioma than in asbestosis.

Note: Mesothelioma may also affect the pericardium and peritoneum.

Diffuse Parenchymal Lung Disease

Diffuse Parenchymal Lung Disease

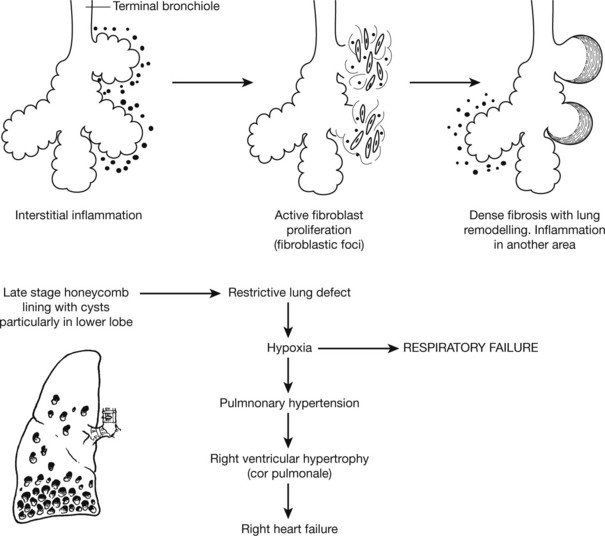

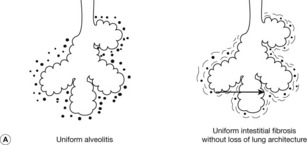

This encompasses a group of conditions in which the lung is altered by a combination of interstitial inflammation and fibrosis. Several histological patterns are recognised but it is thought that regardless of the type the earliest manifestation is alveolitis and that this accumulation of leucocytes results in release of mediators that can injure parenchymal cells and stimulate fibrosis.

UIP is considered to be the caused by repeated cycles of alveolitis. Healing after each cycle gives rise to fibroblastic proliferation known as fibroblastic foci such that as the disease progresses the fibrosis is a different stages (temporal heterogeneity).

Infection is a common terminal event, and there is an increased risk of lung cancer.

This form of fibrosis has a much better prognosis than UIP and is usually steroid responsive. The lung is uniformly affected by interstitial fibrosis and inflammation of variable severity. Fibroblastic foci are abscent and progression to honeycombing is rare. This pattern is commonly seen in association with connective tissue diseases.

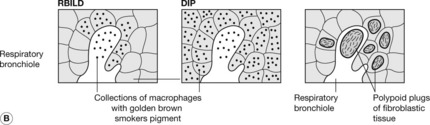

These patterns are both seen almost exclusively in cigarette smokers. In RBILD macrophages accumulate in a patchy distribution around respiratory bronchioles. In DIP there is diffuse distribution of macrophages.

(Bronchiolitis obliterans organising pneumonia). This characterised by a patchy distribution of polypoid plugs of fibroblastic tissue in alveoli, alveolar ducts and sometime bronchioles. A similar pattern may be seen with certain infections, drugs or connective tissue diseases.

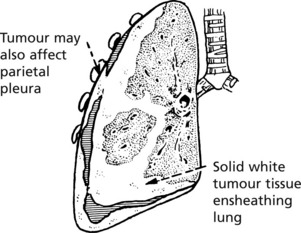

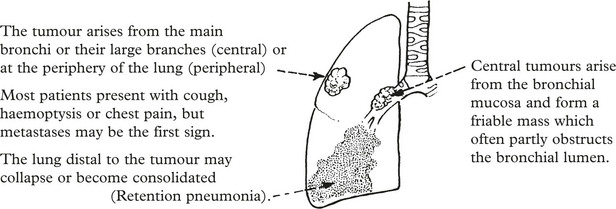

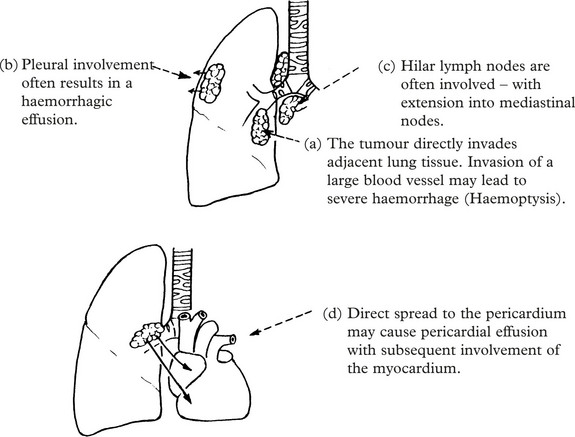

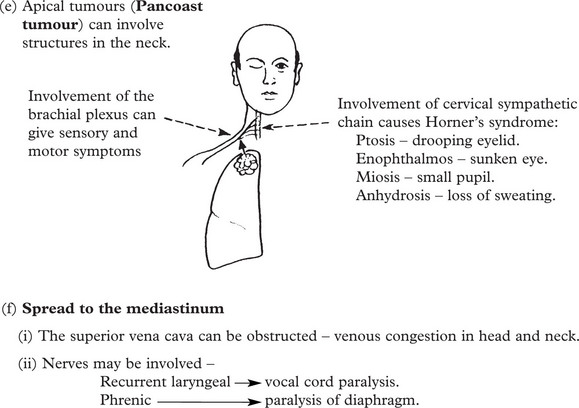

Lung Cancer

Lung cancer (carcinoma of the bronchus) is the commonest form of cancer and one which is largely preventable. Approximately 35000 patients die of lung cancer in the United Kingdom each year.

Non-Metastatic Effects

Other syndromes include: encephalopathy, cerebellar degeneration, neuropathy, myopathy, Eaton Lambert myasthenia-like syndrome, etc.

Histological Types

Four main types are recognised

| 1. Small cell … … … … … … … … … … | 20%. | The proportions vary between series. |

| 2. Squamous carcinoma … … … … … … … | 30%. | |

| 3. Adenocarcinoma … … … … … … … … | 40%. | |

| 4. Large cell carcinoma … … … … … … … | 10%. |

The separation of small cell carcinoma from non-small cell variants is extremely important as the former tumour is treated by chemotherapy. Sub-classification of non-small cell variants is now important for certain targetted chemotherapies.

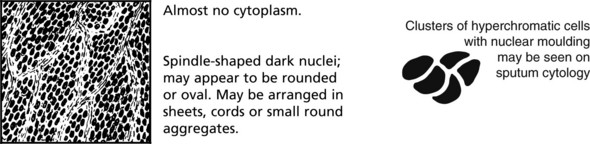

Small Cell Lung Carcinoma

This is the most aggressive form of lung cancer and metastasises early and widely. It does respond well, at least initially, to cisplatin based chemotherapy – some patients survive for up to 2 years.

The tumour arises from neuro-endocrine cells and expresses markers such as NCAM-1. It is the form which most commonly has endocrine and other non-metastatic humoral effects.

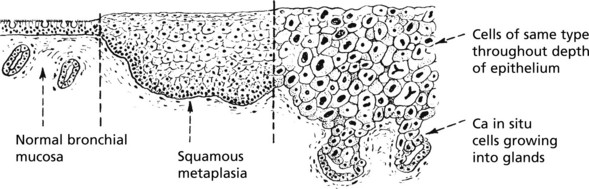

Squamous Carcinoma

These tend to arise centrally from major bronchi, within dysplastic squamous epithelium following squamous metaplasia.

Although squamous carcinoma is often slow growing, there is often extensive destruction of local tissues. The affected bronchi are often blocked, leading to retention pneumonia or collapse.

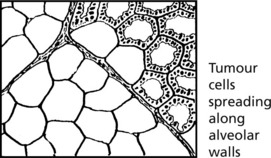

Adenocarcinoma

This tumour is a common tumour in women and is seen in non-smokers, but is also associated with smoking. At least two-thirds arise in the periphery of the lung, sometimes in relation to scarring. In non-smoking women, particularly of East Asian origin, there is a high incidence of epidermal growth factor receptor mutations that confer responsiveness to certain chemotherapeutic agents.

Large Cell Carcinoma

As the name suggests, this tumour consists of large malignant cells without any specific differentiation. This is therefore a diagnosis of exclusion. The tumour usually arises centrally.

Aetiology of Lung Cancer

Other Tumours of the Bronchi and Lungs

Benign tumours of the bronchi and lung are unusual. There are 2 main types.

Papillomas are similar to the papillary tumours of the larynx. They occur in young people and on occasion may cause stridor due to partial bronchial obstruction. They are due to papilloma virus infection (types 6 and 11). Malignant change is exceptional.

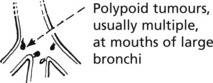

Carcinoid Tumours

These tumours account for 1–2% of primary lung neoplasms. They often appear around the age of 50 years. Usually the tumour is situated in a primary bronchus or at the lung periphery. The tumour is a smooth surfaced yellow nodule.

Histologically these resemble carcinoid tumours of the appendix (see p.334). A small proportion of these tumours metastasise to regional lymph nodes – all are potentially malignant.

Central tumours tend to block the bronchus in which they arise.

Atypical carcinoid tumours: This sub-group of tumours shows nuclear pleomorphism, mitotic activity and necrosis. Over half eventually metastasise.

Diseases of the Pleura

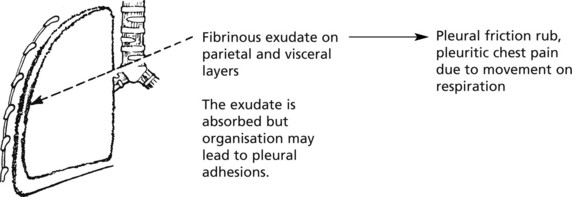

Inflammation (Pleurisy)

Fibrinous Pleurisy

If fluid accumulates in excess, there is a pleural effusion – pain and friction rub disappear as the inflamed layers are separated.

If infection of the pleura proceeds, an empyema (a collection of pus in the pleura) may form. This is now unusual.

Pleural Effusion

The accumulation of fluid within the pleura can be explained as a form of local oedema.

The composition of the fluid is related to the underlying cause.

| TRANSUDATE | EXUDATE |

|---|---|

| e.g. in heart failure – low protein content; – few inflammatory cells. |

e.g. in fibrinous pleurisy – high protein content; – numerous inflammatory cells. |

Examination of the pleural fluid may show mesothelial cells, lymphocytes, macrophages, neutrophils and sometimes tumour cells.

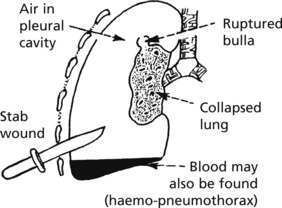

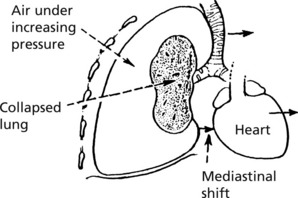

Pneumothorax

This is the accumulation of air in the pleural space. It may follow blunt trauma or penetrating wound, e.g. stabbing. Older patients with emphysema may develop spontaneous pneumothorax. In young people this is usually due to rupture of small bullae or excessive smoking of cannabis.

In a TENSION PNEUMOTHORAX there is a valve effect – air continues to enter the pleura during inspiration but cannot exit during expiration.

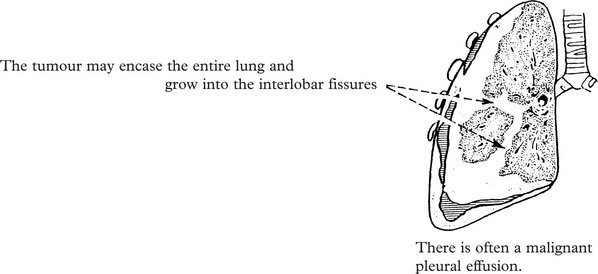

Pleural Malignancy

Metastatic tumours affect the pleura in 2 ways.

There is usually a pleural effusion in which tumour cells can be found.