Chapter 9 Gastrointestinal Tract

The Mouth

Viral Infections

Herpes simplex virus (usually type I) infects the mouth in young children – this is often asymptomatic but in 10–20% of cases numerous vesicles and ulcers are seen. The virus can become latent in the trigeminal ganglion and repeated ‘cold sores’ occur on the lip in later life.

Coxsackie viruses can cause oral blistering (e.g. herpangina; hand, foot and mouth disease). Koplik’s spots are a feature of measles.

Fungal Infection

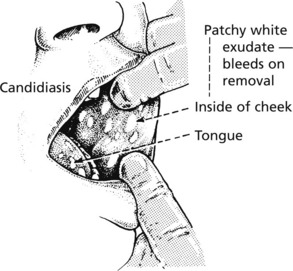

Candida albicans is an oral commensal in 40% of the population.

Clinical infection is seen in infants, in patients on broad spectrum antibiotics, steroid or cytotoxic therapy and also in the immunosuppressed and diabetics. Extensive oral candida is common in patients with AIDS.

Bacterial Infections

Syphilis, now uncommon in the West, can involve the mouth as a primary chancre, irregular lines of ulceration – snail track ulcers of the secondary stage, and as small gummas (tertiary).

Oral tuberculosis, usually due to coughed up bacilli from pulmonary TB, is now very uncommon. Ulcers may occur on the tongue.

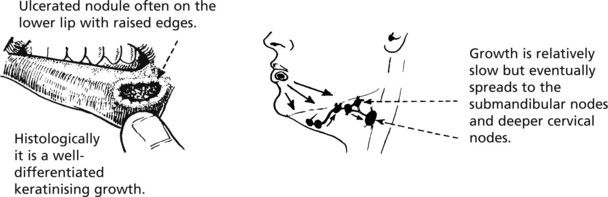

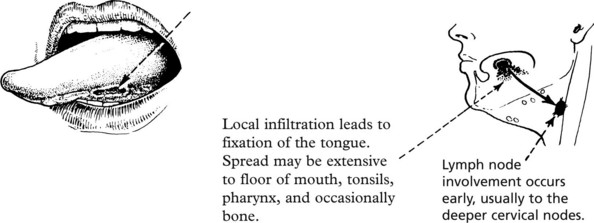

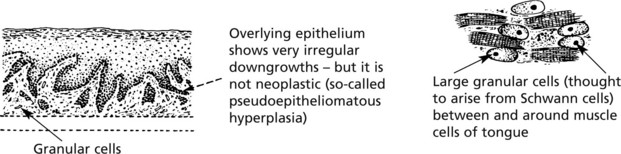

Oral Cancer

Oral cancer accounts for 2% of cancers in the United Kingdom. There is wide geographical variation – commoner in S. East Asia. Males are at least twice as commonly affected as women – it is a disease of the elderly.

Mouth

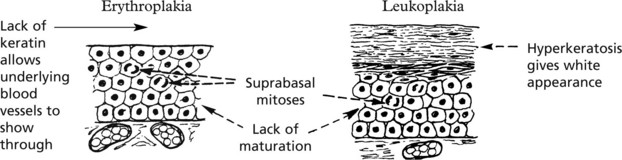

Erythroplakia and Leukoplakia

These terms describe velvety red patches and white patches in the oral mucosa. These are important because they may represent dysplasia of the squamous epithelium and may lead to squamous cancer.

Not all examples of leukoplakia are premalignant and may also be due to:

A distinctive form – ‘hairy leukoplakia’ – occurs on the lateral border of the tongue in patients with HIV/AIDS. It is due to Epstein–Barr virus infection, often with superimposed candida.

Pigmentations

Melanotic pigmentation of the mouth is seen in Addison’s disease, haemochromatosis and the Peutz–Jeghers syndrome.

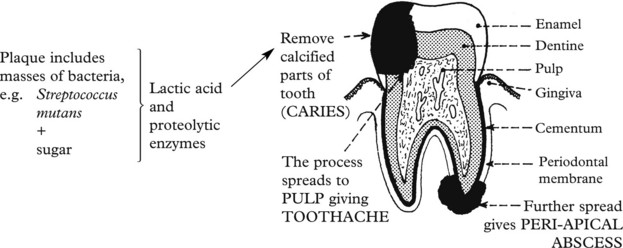

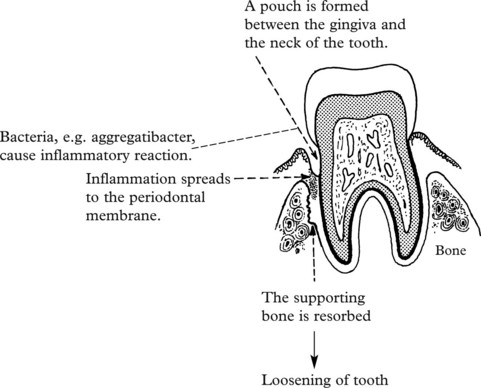

Dental Caries and Periodontal Disease

These two very common processes are primarily of importance to dentists but an understanding is also valuable for doctors.

Diseases of the Salivary Glands

Inflammation

The commonest acute inflammation is due to the mumps virus, which produces acute swelling, particularly of the parotid glands, with oedema and mononuclear infiltration of the interstitial tissue.

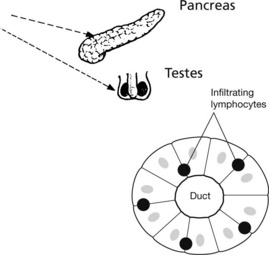

The testes and pancreas may also be inflamed and atrophy may follow.

Bacterial infection of these glands is uncommon and may occur during a prolonged illness, particularly if a calculus has formed in a duct.

Chronic inflammation is rare. It may occur in sarcoidosis. The parotid gland becomes swollen and there may be an accompanying irido-cyclitis. This has given rise to the term ‘uveo-parotid fever’. The parotid gland shows a chronic inflammatory reaction with granulomas typical of sarcoidosis.

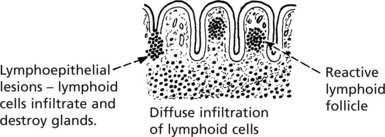

Sjögren’s Syndrome

In this auto-immune condition there is destruction of the salivary, lacrimal and conjunctival glands by an infiltrate of lymphocytes (so-called lympho-epithelial lesions) and plasma cells. The duct epithelia often undergo reactive hyperplasia. It results in dryness of the mouth, caries due to lack of saliva, and ulceration of the conjunctiva caused by lack of secretion from the lacrimal and conjunctival glands. This is often associated with rheumatoid disease.

There is an increased risk of B cell lymphoma (p. 431).

Salivary Glands – Benign Tumours

Pleomorphic Adenoma

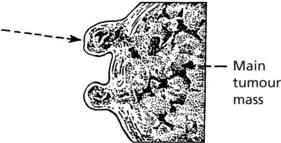

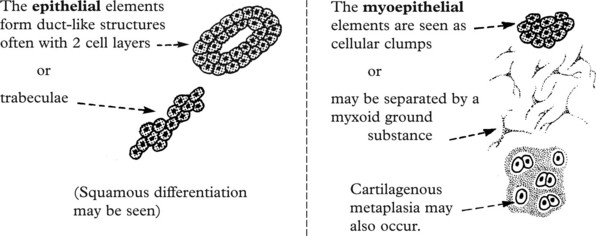

This is the commonest tumour of the salivary glands and most often occurs in the parotid. The term ‘pleomorphic’ applies not to the nuclei of the cells but to the different types of tissue found. These are derived from the epithelial and myoepithelial cells.

The tumour is lobulated and encapsulated but there are frequently small lobules which extend into the adjacent tissue.

If the tumour is ‘shelled out’ these lobules are left behind and cause local recurrence. For this reason superficial parotidectomy is usually performed, ensuring complete removal of the tumour.

Salivary Glands – Carcinomas

Almost all malignant tumours of the salivary glands are adenocarcinomas. They affect major and minor glands and arise de novo or from pre-existing pleomorphic adenoma. The prognosis is variable.

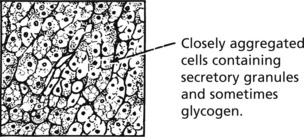

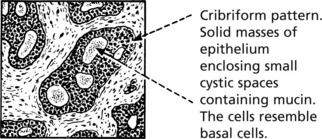

Three unusual subtypes are worth noting.

Approximately 1/4 of all malignant parotid tumours are of this type. It grows slowly, recurs after removal and sometimes there is late spread to the regional lymph nodes and distant organs.

Oesophagus

The oesophagus is a muscular tube 25 cm long lined by stratified squamous epithelium which is resistant to damage by heat, cold and mechanical trauma.

Inflammation

Reflux Oesophagitis

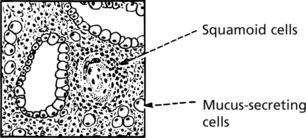

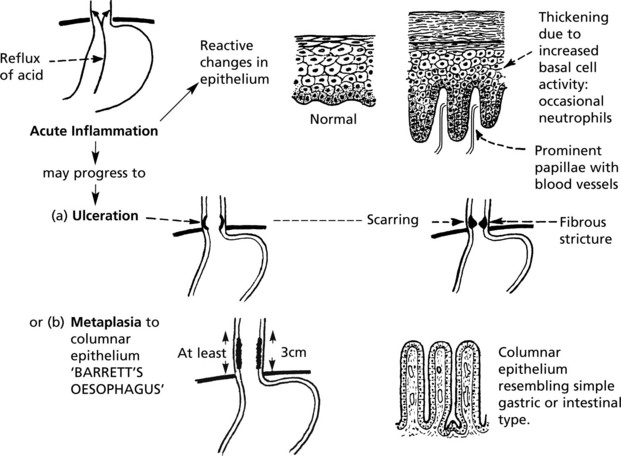

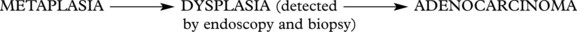

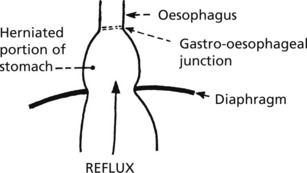

This is the commonest form of inflammation due to reflux of gastric acid through a relaxed lower oesophageal sphincter into the lower oesophagus, often associated with hiatus hernia.

This is an important premalignant lesion with a 30–40 fold increased risk of cancer.

Other Forms of Oesophagitis

Hiatus Hernia

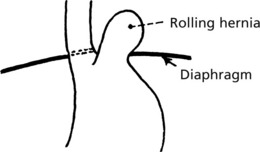

In hiatus hernia part of the stomach herniates into the thorax. This is common, particularly in the elderly, though often asymptomatic. Two forms are seen:

Diverticula

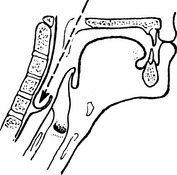

These are relatively rare and are of 2 varieties.

Involves pharynx (pharyngeal pouch). Sac is distended during swallowing of food. By pushing down behind oesophagus, it may compress this structure. Abnormal function of the upper oesophageal sphincter is an aetiological factor.

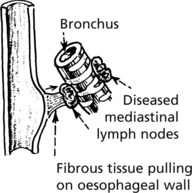

This is due to traction of fibrous tissue produced by mediastinal inflammation, e.g. tuberculosis of lymph nodes.

Rarely, there may be a congenital diverticulum at the level of the bifurcation of the trachea.

Obstruction usually leads to dysphagia – difficulty in swallowing. The causes include:

Strictures of the oesophageal wall due to:

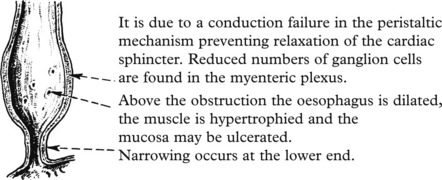

Achalasia of the oesophagus develops in young adults and may cause severe obstruction.

(In South American trypanosomiasis the myenteric plexus may be destroyed (CHAGAS DISEASE) and long-standing diabetic autonomic neuropathy may cause a similar problem.)

In Systemic sclerosis, replacement of muscle by fibrous tissue converts the oesophagus into a rigid tube.

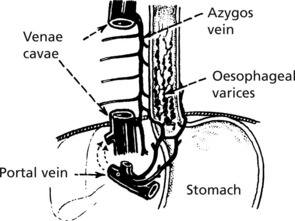

Oesophageal Varices

These dilated veins occur secondarily to portal hypertension caused mainly by cirrhosis of the liver (see p.350).

Fibrosis in the liver obstructs the flow of blood from the gastrointestinal tract. Anastomotic channels connecting the portal and systemic venous systems open up and become distended. The most important are the oesophageal tributaries of the azygos vein which connect through the diaphragm with the portal system. They become varicose, and are easily traumatised by the passage of food, leading to haemorrhage which can be severe.

Spontaneous rupture of the oesophagus is rare. Mucosal tears causing haemorrhage may occur (Mallory–Weiss syndrome).

Congenital abnormalities include stenosis and atresia with fistula formation.

Oesophagus – Tumours

Benign tumours of the oesophagus are rare. They are almost always of connective tissue origin (usually leiomyomas) and form polyps within the lumen, causing obstruction.

Carcinoma

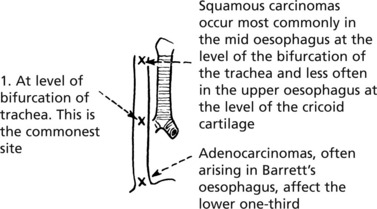

Carcinoma of the oesophagus occurs in two main forms:

Spread

Middle third tumours may involve the trachea with fistula formation leading to aspiration pneumonia. Tumours of the lower third may invade the mediastinum. Lymph node involvement is common and blood borne metastases to liver occur late.

Aetiology

There is geographical variation, tumours being common in China and Africa. Smoking and diet, including alcohol consumption, are important in squamous carcinoma. Post-cricoid carcinoma in women is a rare late complication of the dysphagia complicating iron deficiency anaemia. Adenocarcinoma is largely due to Barrett’s oesophagus and reflux.

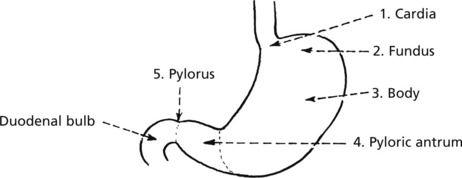

Stomach

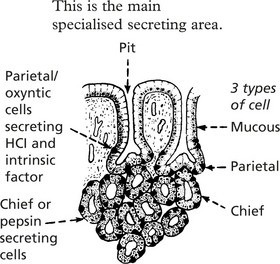

The stomach is divided into five anatomical regions:

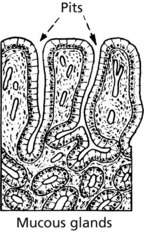

Three forms of mucosa are seen:

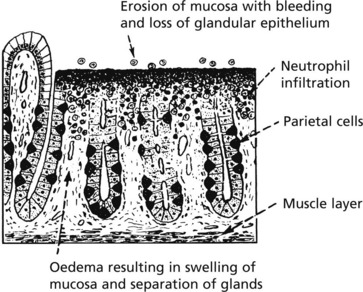

Acute Gastritis

Mild acute gastritis with neutrophils in the mucosa may be caused by alcohol and non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), and are seldom biopsied. Acute haemorrhagic or erosive gastritis is a more severe form, also associated with aspirin and NSAIDs, and is also a complication of shock.

Tiny ulcers affect all parts of the stomach, occuring on the apex of mucosal folds, and can heal rapidly.

Gastritis

Acute Inflammation

Mild acute gastritis is an acute inflammation with neutrophil reaction in the superficial layers of the mucosa. Pain and sickness have a multitude of causes varying from hot fluids, alcohol and aspirin which act as direct irritants, to infections such as childhood fevers, viral infections and bacterial food poisoning.

A more acute form, known as acute haemorrhagic or erosive gastritis, is associated with ingestion of irritant drugs, particularly aspirin and NSAIDs and is also a complication of shock states.

Haemorrhagic Erosions

These are tiny ulcers, a few millimetres in diameter, which are formed by the digestion of the mucous membrane overlying small haemorrhages. They are usually multiple and affect all parts of the stomach. They occur mostly on the apex of mucosal folds and involve only the mucosa.

Note that the changes are superficial so that restoration to normal can occur very quickly occur.

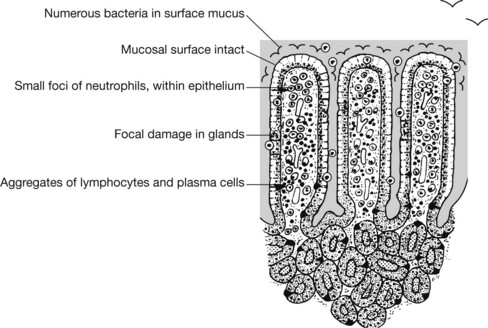

Chronic Gastritis

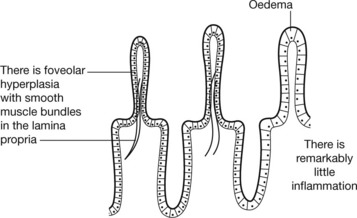

There are 3 main causes of chronic gastritis:

Other Forms of Gastritis

These include eosinophilic gastritis associated with food allergy, collagen diseases and parasites.

Granulomatous gastritis has many causes including Crohn’s disease, TB and sarcoidosis.

Lymphocytic gastritis shows an increase in intraepithelial lymphocytes and is often associated with coeliac disease (p. 307).

Peptic Ulceration

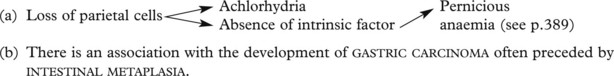

Peptic ulcers occur when acid-containing gastric juices breach the mucosa of the gut.

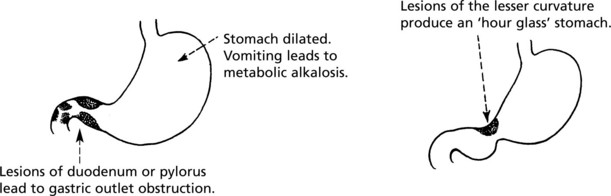

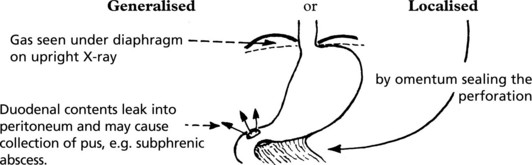

Chronic peptic ulcers are found in 3 main sites.

Peptic ulcers are usually solitary, but in 10% a second ulcer is found, e.g. on the opposite side of the duodenum (kissing ulcer).

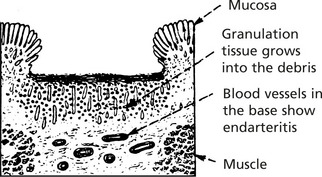

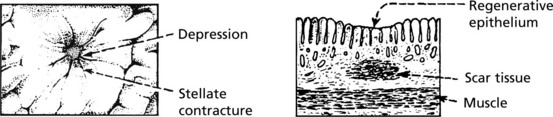

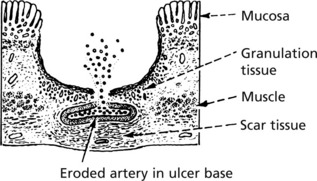

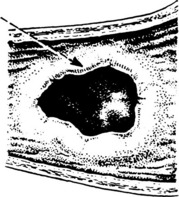

A typical chronic peptic ulcer is a punched out oval ulcer 2–3 cm in diameter.

The surrounding mucosa often shows stellate folds due to scarring.

The ulcer bed consists of fibrin and debris.

In long standing lesions fibrous tissue replaces muscle.

Acute gastric ulcers (often called stress ulcers) may be seen in patients with severe burns, after major trauma or with raised intracranial pressure. These may cause bleeding, but usually heal completely. Acute ulcers may also be due to treatment with NSAIDs.

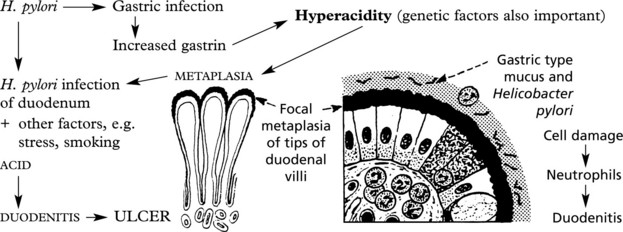

Peptic Ulcer – Aetiology

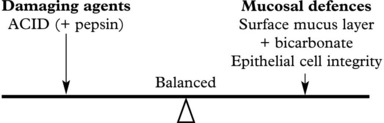

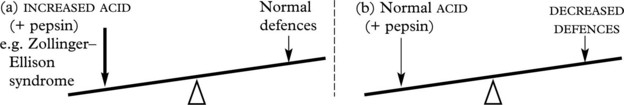

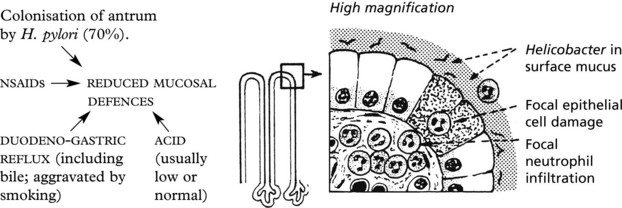

Normally gastric mucosal damage is prevented by a balance between the damaging agents and the mucosal defences.

Peptic ulceration results from imbalance.

Although the mechanisms in gastric and duodenal ulcers differ, in both HELICOBACTER PYLORI infection is important.

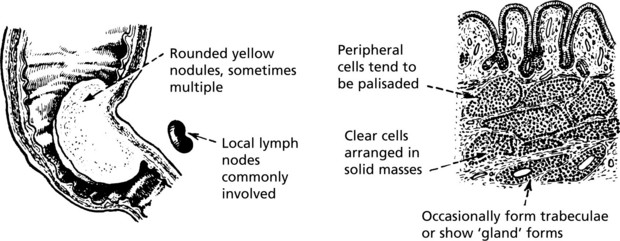

Gastric Carcinoma

This important tumour has an especially high incidence in Japan, Chile and Eastern Europe. Its incidence has fallen in the United Kingdom and the USA since the 1930s.

Morphologically, there are several types.

These exophytic tumours are commonly seen in the fundus.

Eventually the tumour spreads through the stomach wall to the serosa and is often ulcerated on the surface.

Tumours may occur at the cardia or distal stomach. Different aetiologies apply.

These tumours, often in the antrum, produce large irregular ulcers with a rolled edge. The rolled edge rather than the ulcer base should be biopsied.

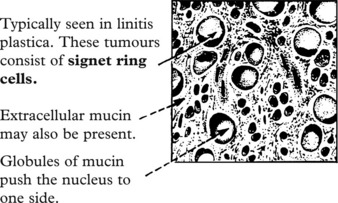

In this form of tumour the entire gastric wall is thickened. Ulceration is usually minimal, but the mucosal folds are prominent.

This is sometimes knows as ‘leather-bottle stomach’ (linitis plastica).

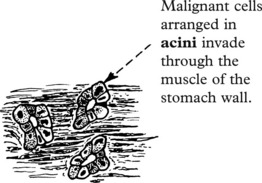

Histologically, gastric cancers tend to fall into one of two types:

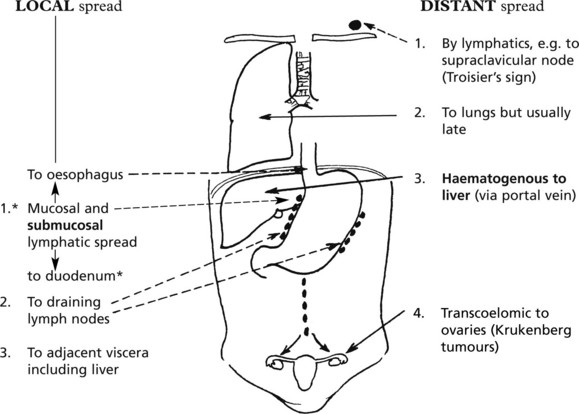

Gastric carcinomas are aggressive tumours with both local and distant spread.

*Note: The duodenal mucosa is resistant to direct mucosal spread.

Staging is by the TNM system (Tumour: Nodes: Metastases).

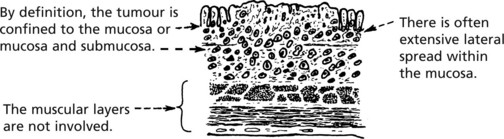

Early Gastric Cancer

Early gastric cancers are common in populations where there is screening, e.g. Japan. The prognosis is far better than for deeply penetrating ‘advanced’ tumours.

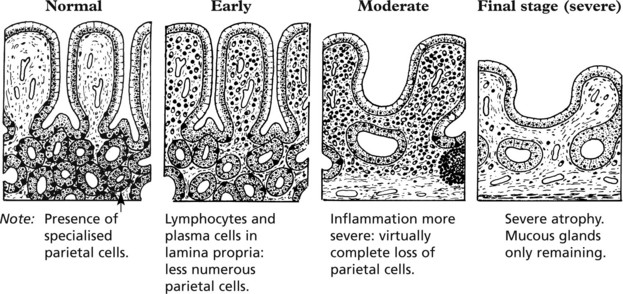

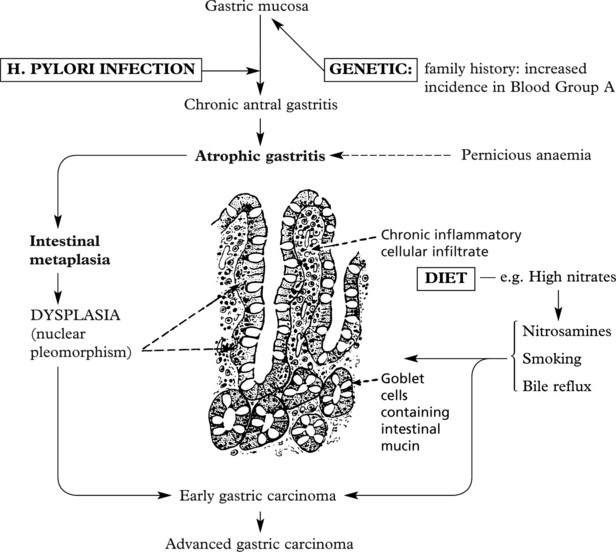

Aetiology

It has long been recognised that gastric cancer occurs in achlorhydric states, especially with chronic atrophic gastritis.

It is now clear that Helicobacter pylori is a major carcinogenic factor for these tumours arising in the distal stomach. Acid reflux is responsible for those in the proximal stomach.

Other Gastric Tumours

Benign gastric polyps are often seen at endoscopy. Fundic gland polyps are found in patients on proton pump inhibitors.

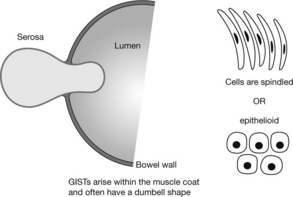

Gastrointestinal stromal tumours (GISTs) arise from within the stomach wall and may cause haemorrhage. All are potentially malignant.

gastric lymphomas account for 5% of gastric malignancy. They are usually ‘B’ cell lymphomas of malt type (p.436). They are strongly associated with Helicobacter pylori infection and some lymphomas respond to eradication of H. pylori.

Small Intestine – Malabsorption

The main function of the small intestine is digestion and absorption of food.

Malabsorption may be due to disorders of the small bowel, pancreas and biliary tract.

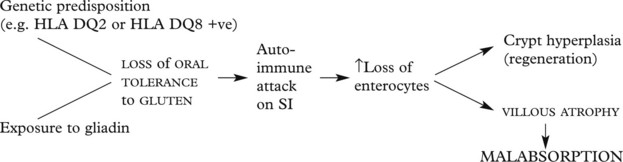

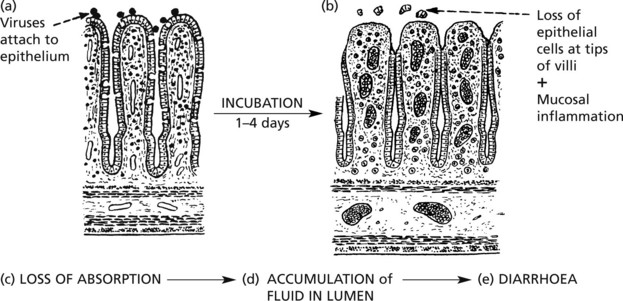

Coeliac Disease

This important cause of malabsorption is due to sensitivity to gliadin, a component of the wheat protein gluten. The clinical features depend on the age at presentation.

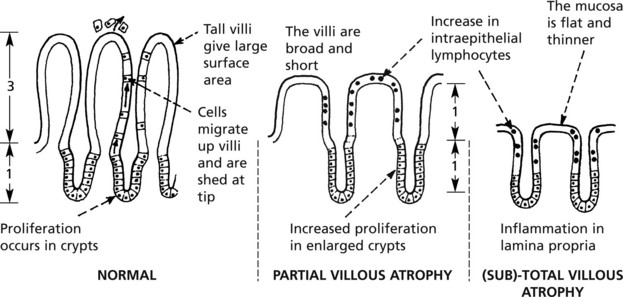

In coeliac disease there is partial or complete villous atrophy.

These changes are seen in biopsies of small bowel, usually the distal duodenum by endoscope. The changes revert to normal if gluten is removed from the diet. Serological tests are available with anti-endomysial antibodies or directed against tissue transglutaminase (tTG).

The basic mechanism is as follows:

Patients with coeliac disease also have increased prevalence of autoimmune diseases, e.g. diabetes, autoimmune thyroiditis and of lymphocytic colitis, a cause of diarrhoea. They are at increased risk of developing small bowel lymphoma.

Malabsorption

Other causes of malabsorption in the small bowel include:

This is a disease of unknown aetiology occurring in the tropics. Villous atrophy is seen and patients develop steatorrhoea, weight loss and deficiency of B12 and Folate, leading to megaloblastic anaemia. Treatment with folic acid and antibiotics cause the disease to remit.

An infection with the protozoan Giardia lamblia, giardiasis is associated with diarrhoea and malabsorption. Patients with hypogammaglobulinaemia are especially at risk.

In this rare condition, mainly of middle aged men, malabsorption, arthritis, lymphadenopathy and skin pigmentation are seen.

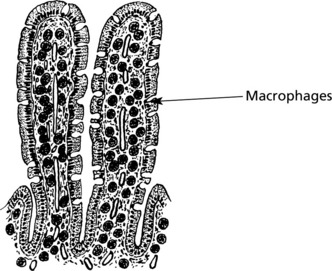

Large macrophages fill the lamina propria. They contain mucopolysaccharides (are periodic acid Schiff (PAS) positive). Electron microscopy shows numerous intracellular bacteria – now thought to be a gram-positive organism Tropheryma whippelii. Antibiotics are curative.

Pancreatic diseases, e.g. cystic fibrosis (p.375) and obstructive jaundice (p.341), also cause malabsorption.

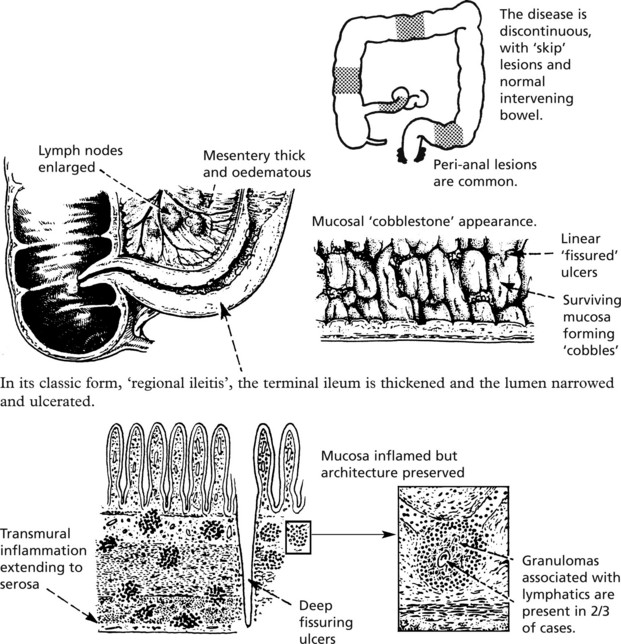

Crohn’s Disease

Crohn’s disease and ulcerative colitis are two forms of non-infective inflammatory bowel disease. They have similarities and striking contrasts (p. 311).

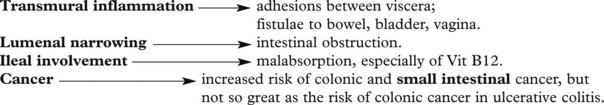

Ulcerative Colitis

Clinical Features

Patients, usually young adults, present with diarrhoea, often bloody. The disease has a remitting/relapsing course. In severe cases weight loss and anaemia are common. The disease begins in the rectum and shows continuous spread proximally.

The whole colon is affected in 20% of cases.

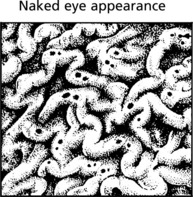

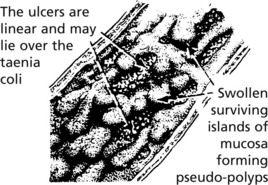

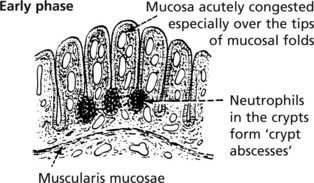

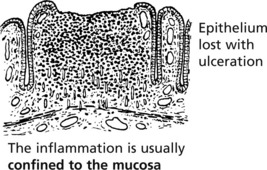

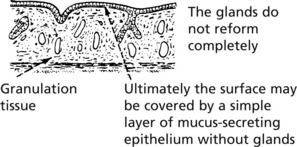

In the established disease the gross appearances are striking.

Local Complications

Toxic megacolon: In a small number of patients inflammation is very severe and the colon becomes greatly dilated and thinned. There is a high risk of perforation with peritonitis.

Dysplasia and Colonic cancer: Patients with (a) early onset, (b) total colonic involvement and (c) long-lasting (10–20 years) disease have a greatly increased risk. These patients require colonoscopic surveillence with biopsy to look for dysplasia and cancer.

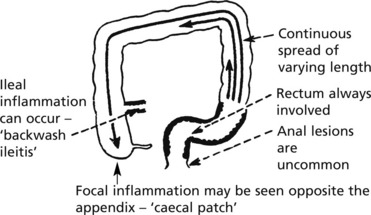

Crohn’s Disease and Ulcerative Colitis

The aetiology of these two conditions is uncertain. Both have mild familial tendency (approximately 10%). Infectious causes have been suggested but never proven.

Intestinal epithelial dysfunction may allow entry of bacterial components stimulating mucosal immune responses. Food allergy and stress may be involved in ulcerative colitis. Ex-smokers and non-smokers have a higher risk of ulcerative colitis; the converse is true for Crohn’s disease.

Extra-Gastrointestinal Complications – both Diseases

Macroscopic differences in the pathology of UC and CD:

| Ulcerative colitis | Crohn’s disease |

|---|---|

| 1. Lesions continuous – mucosal | Skip lesions – transmural |

| 2. Rectum always involved | Rectum normal in 50% |

| 3. Terminal ileum involved in <10% (backwash ileitis – mild); caecal patch | Terminal ileum involved in 30% |

| 4. Granular, ulcerated mucosa; no fissuring | Discretely ulcerated mucosa; cobblestone appearance; fissuring |

| 5. Often intensely vascular | Vascularity seldom pronounced |

| 6. Normal serosa | Serositis common |

| 7. Muscular shortening of colon | Fibrous shortening; strictures common |

| 8. Fistulae rare | Enterocutaneous or intestinal fistulae in 10% |

| 9. Malignant change – well recognised | Malignant change – less common |

| 10. Anal lesions uncommon | Anal lesions in 75%; anal fistulae; ulceration or chronic fissure |

It may be impossible to distinguish between ulcerative colitis and Crohn’s disease, so called ‘indeterminate colitis’.

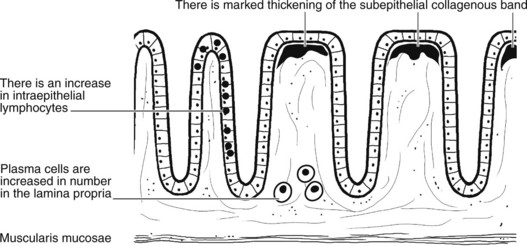

Microscopic Colitis

This term describes two forms of colitis which are often overlooked because the colon appears normal on colonoscopy. Both tend to occur in middle aged women who present with chronic watery diarrhoea. The diagnoses depend on identification of characteristic histological findings.

Intestinal Infections

Viruses, bacteria, protozoa and worms can all infect the gastrointestinal tract. There are 3 main patterns of infection:

Acute Diarrhoeal Diseases

In these disorders, infection, mainly of the small bowel, produces little mucosal inflammation, but there is often profuse watery diarrhoea. In adults this may be mild but, especially in infants, dehydration can lead to death.

Responsible organisms include: E. coli, Vibrio cholerae, rotaviruses, Cryptosporidium parvum, Campylobacter jejuni.

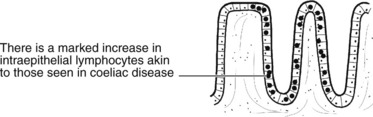

Cholera is the classic example of the effects of toxin production.

Note: There is minimal epithelial cell damage.

E. coli 0157 is a strain which produces exotoxin causing haemorrhagic colitis often complicated by renal failure in the elderly or the haemolytic uraemic syndrome in children. The contamination is on meat or meat products and outbreaks and sporadic cases occur worldwide.

Toxic enteritis (Food poisoning)

Many bacteria release enterotoxins into food before it is consumed: although cooking kills the bacteria the preformed toxin may be heat resistant. Staphylococcus aureus and Bacillus cereus (in rice particularly) are good examples.

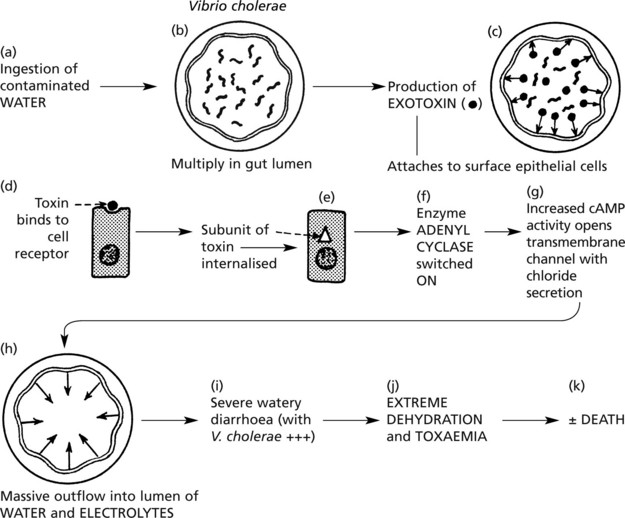

In ROTAVIRUS infection, seen especially in children under 5 years, the mechanism is different.

Note: Recovery is usually rapid and complete, providing dehydration is treated.

Typhoid

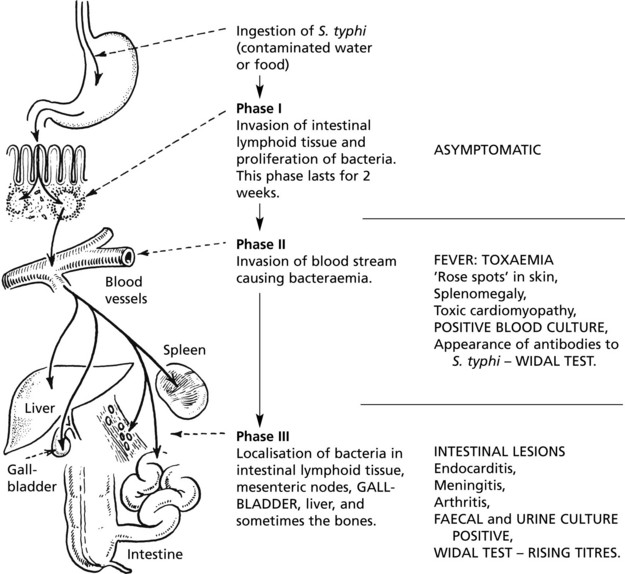

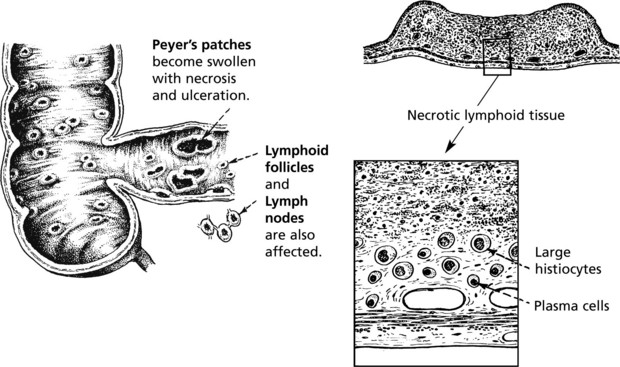

Typhoid Fever

Following ingestion of S. typhi, the disease process falls into three distinct phases.

Paratyphoid Fever

This disease is clinically indistinguishable from typhoid fever but is usually much less severe.

The pathological changes resemble those of typhoid fever but are commonly limited to a small portion of the bowel. Frequently there is an absence of ulceration.

Two serological types of the paratyphoid organism are recognised, A and B. Type B is a common cause of enteric fever in Europe. As in typhoid, patients often become ‘carriers’.

Note: TAB vaccination, using antigens derived from S. typhi and paratyphi A and B, produces a very effective active immunity.

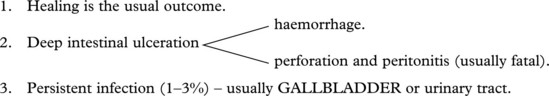

Bacillary Dysentery

This is an acute inflammation of the large intestine, varying in severity according to the infecting agent.

Clinical Manifestations

There is acute diarrhoea with abdominal pain, tenesmus and the passage of blood-stained mucus. S. dysenteriae infections are often associated with severe toxaemia and sometimes a shock-like condition. Blood, mucus and neutrophils are found in the faeces, and in the early stages the bacilli can be isolated.

Healing by resolution with complete restoration of the mucosa is usual. Only in exceptional cases does relapse occur with consequent scarring.

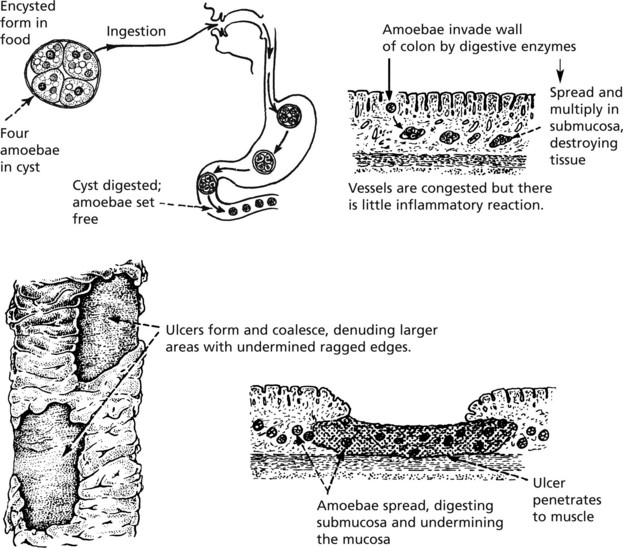

Amoebic Dysentery

This is due to infection by Entamoeba histolytica in food and water. It is most often seen in tropical and subtropical countries.

Healing of the ulcers with fibrosis occurs. The disease persists with overgrowth of fibrous tissue, adhesions to various structures and fistulae may occur. Occasionally the amoebae may invade portal venous tributaries and cause amoebic abscess of the liver (p.360).

Large numbers of motile amoebae can be found in the faeces during the acute phase of the disease. Later, in the chronic state, they are frequently in an encysted form. Mucus and blood are abundant.

Note: Non-pathogenic amoebae can be found in the colon of healthy individuals.

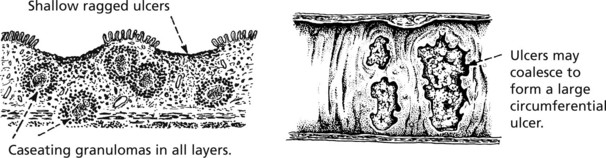

Tuberculous Enteritis and Pseudomembranous Colitis

This is due to swallowing tubercle bacilli from open pulmonary tuberculosis. The mucosal lesion is prominent and lymph nodes less affected. The lesions start in the Peyer’s patches.

As in the lung, there is a good deal of fibrous granulation tissue surrounding the caseous lesions and the vessels undergo obliteration. For this reason, perforation and haemorrhage are uncommon. Adhesions to other loops of bowel are common and the caseating process may erode through the walls and cause fistula formation with short circuiting and resulting malabsorption. If the fibrous adhesions are dense, obstruction may arise.

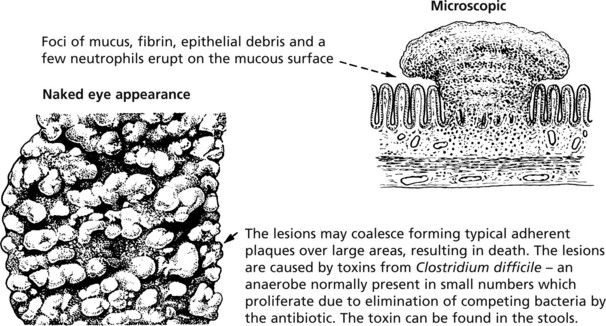

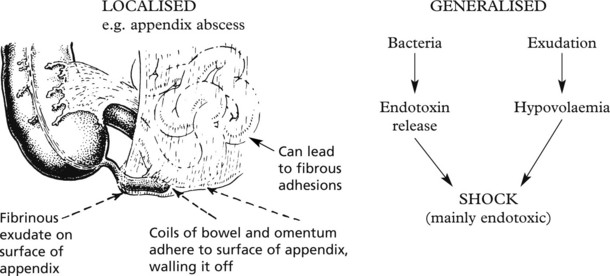

Appendicitis

Acute appendicitis is a common cause of abdominal pain requiring surgery, particularly in the West where there is a low roughage diet.

Appendicitis usually follows obstruction of the lumen with distal infection and ulceration. The usual causes are:

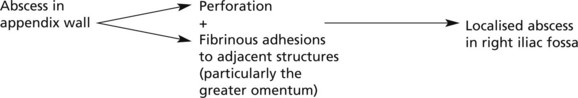

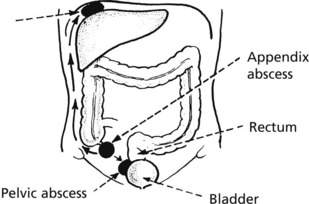

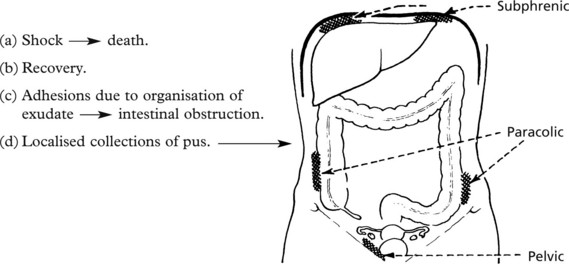

Appendicitis – Sequels

If untreated the appendicitis may become suppurative or gangrenous. The following complications are fortunately very rare.

This arises in the following way:

These are now rare. They are due to spread of infection to the mesenteric veins resulting in septic embolism. Liver abscesses usually arise from infective emboli, but occasionally there may be a spreading suppurating thrombosis culminating in hepatic sepsis.

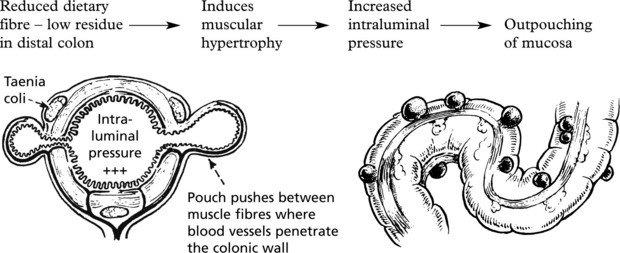

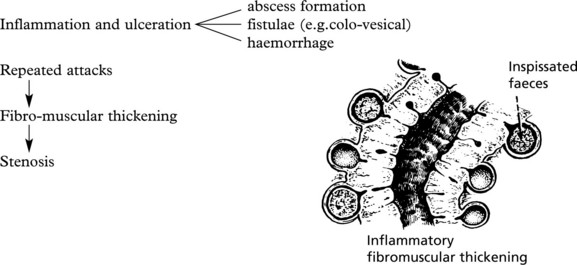

Diverticular Disease

Diverticula are common in the sigmoid colon, affecting at least 50% of adults over 60 years in societies where the diet lacks fibre (low residue).

Complications

Note: This may simulate carcinoma

Other diverticula are also found in the caecum and small intestine: in the latter, colonisation by bacteria which utilise Vit B12 may lead to macrocytic anaemia.

Meckel’s diverticulum of the small intestine is present in 2% of the population.

It is a remnant of the vitello-intestinal duct about 60 cm proximal to the ileo-caecal valve.

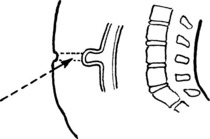

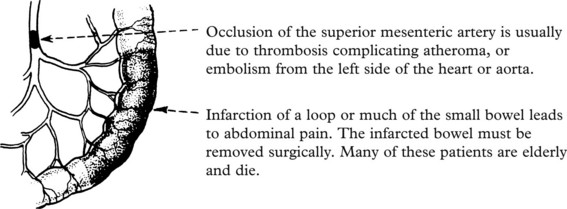

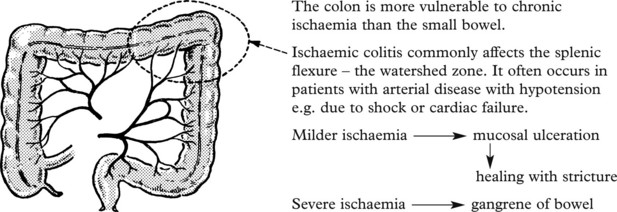

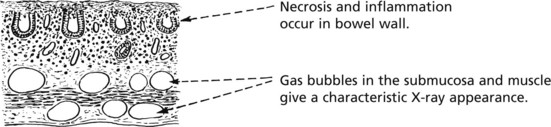

Ischaemia and the Intestines

Ischaemic Colitis

Intestinal ischaemia may also be due to arteritis (p.227), as a side effect of radiation therapy. Drug induced ulcers, e.g. potassium tablets and non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, appear to be due to local ischaemia.

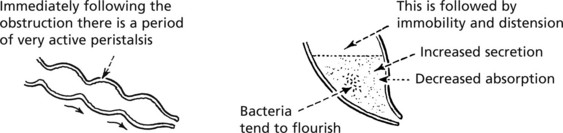

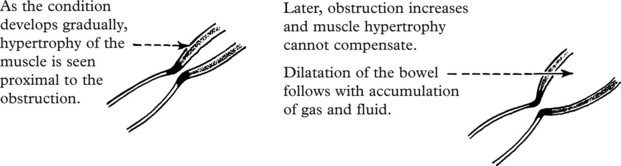

Intestinal Obstruction

Intestinal obstruction can be caused by:

The patient may present with colicky abdominal pain, vomiting and failure to pass flatus or faeces.

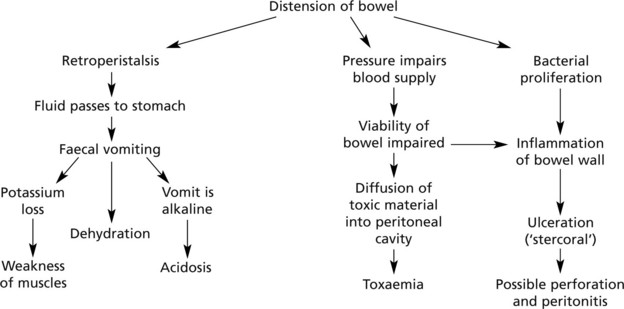

Hernia

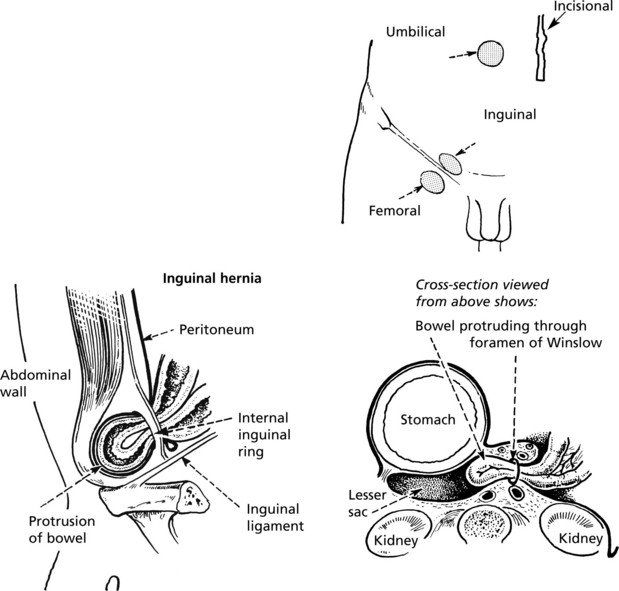

Hernia

This means the protrusion of peritoneum through an aperture.

When the hernial swelling appears on the surface of the body, it is termed ‘external’; those which do not present on the body surface are ‘internal’.

The main complication is protrusion of bowel through the aperture at:

Hernia – Complications

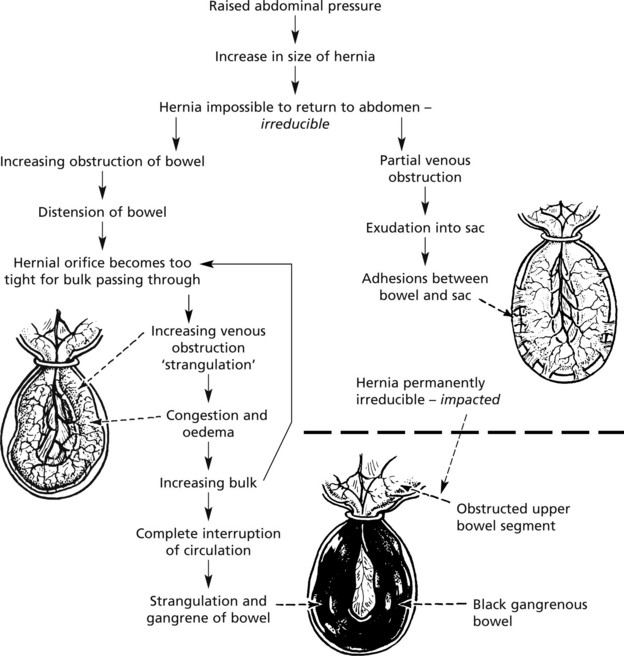

Complications of Hernia

Initially, when the herniated portion of bowel is small it can be pushed back into the abdominal cavity – reducible.

Increased intra-abdominal pressure, e.g. during muscular exertion, coughing or straining due to constipation, helps to induce the herniation, tends to make it progressive, and secondary changes occur.

Intussusception

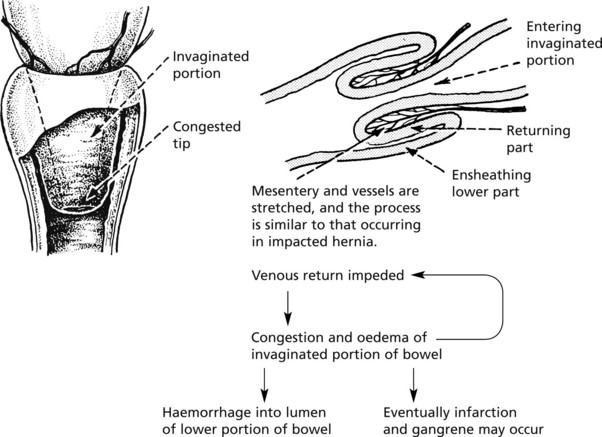

Intussusception

This is a condition in which the bowel is invaginated into itself.

Sites

The commonest form is the ileocaecal type, the ileum being invaginated into the large intestine with the ileocaecal valve forming the apex. Less commonly, a portion of ileum may pass through the ileocaecal valve. Other sites are occasionally affected, e.g. small intestine or parts of colon.

Clinical Manifestations

The patient presents with the signs and symptoms of acute obstruction, a mass in the abdomen and blood is passed per rectum.

Aetiology

It is thought that most cases arise as a result of a swelling in the intestinal wall which is pushed distally by peristalsis, dragging the wall of the bowel with it. Most cases arise in childhood due to swelling of lymphoid tissue produced by virus infection.

Polypoidal tumours of the intestine may cause intussusception in adults.

Volvulus and Hirschsprung’s Disease

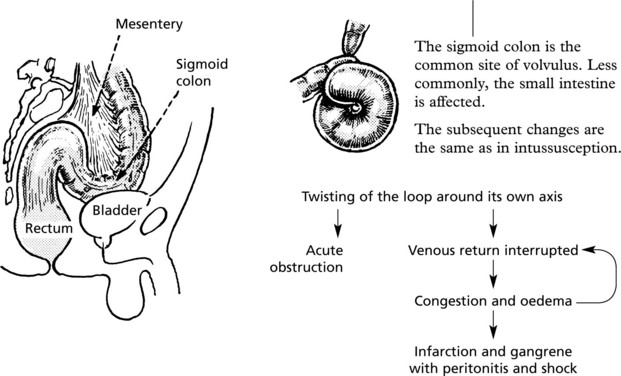

Volvulus

As the name suggests, this is a rotation or revolving of the bowel. It affects bowel with a long mesentery. Another factor is the closeness of the ends of the affected loop.

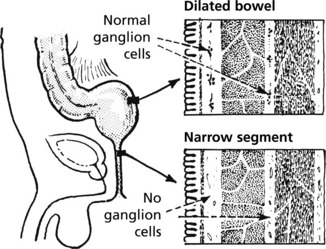

Hirschsprung’s Disease

Hirschsprung’s disease is a rare cause of chronic intestinal obstruction. It is due to a congenital absence of ganglion cells in the parasympathetic Auerbach and Meissner complexes of the rectum. Mutations in genes including the RET gene are often responsible.

The aganglionic rectal segment and anus cannot relax and the bowel above becomes grossly distended and hypertrophied.

Tumours of the Colon

The main tumours of the colon are epithelial – adenomas and carcinomas.

Adenomas – These are important because they may lead on to carcinoma and for this reason bowel screening has been introduced to the UK to detect polyps and early cancers. (Adenoma–carcinoma sequence, p.143)

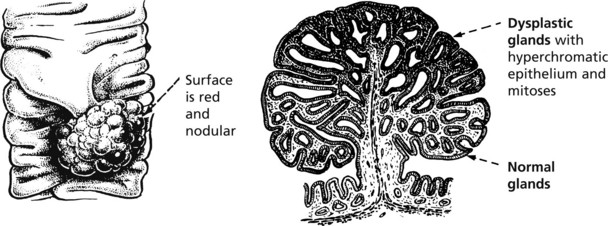

Tubular Adenoma

The majority of tubular adenomas occur in the rectum and sigmoid colon. In the beginning it is a sessile swelling but soon becomes pedunculated.

They are common in the older age groups and are frequently multiple.

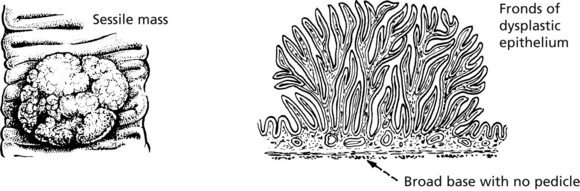

Villous Adenoma

Villous adenomas are most commonly found in the rectum. They form a sessile mass which may be quite large and have a delicate frond-like structure.

These often present with rectal bleeding.

Very rarely, there is an excessive production of mucus and fluid which may lead to marked loss of potassium, causing muscular weakness.

Many polyps are of mixed variety – tubulo-villous. In pedunculated polyps, the stalk is invaded before the intestinal wall itself.

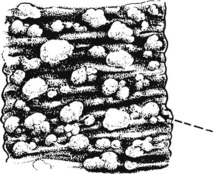

Adenomatosis Coli

This is an inherited condition (autosomal dominant: 50% of children affected) due to mutation of the APC gene, a tumour suppressor gene on chromosome 5.

Adenomatous polyps are found throughout the entire colon, appearing in late childhood. Carcinoma almost always occurs by the 3rd or 4th decade if colectomy is not carried out.

Polyps may also be seen in the stomach and small bowel.

Other Colonic Polyps

These are usually multiple and present as a small sessile nodule showing unusual feathery hyperplastic change in the epithelium. They are found in later life and do not become malignant. Some polyps, known as serrated adenomas, have a similar sawtoothed outline but have dysplastic glands and carry the same risk of malignant change as adenomas.

Carcinoma of the Colon

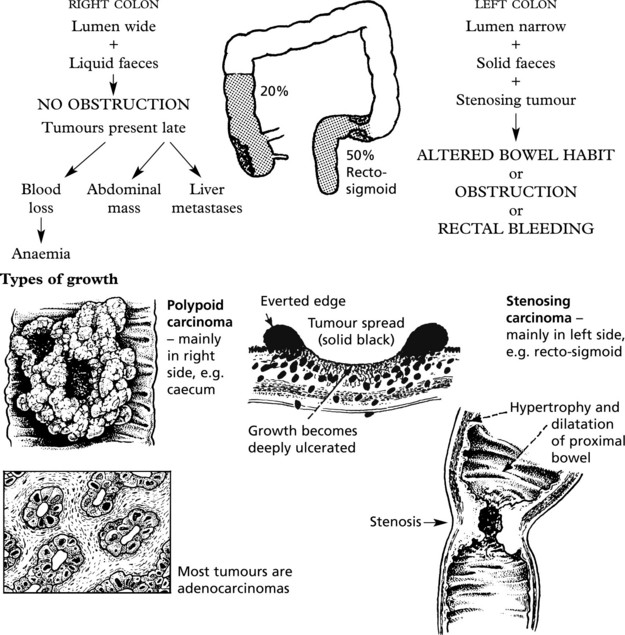

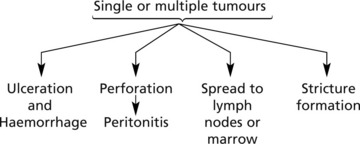

This malignancy is the third commonest cancer world wide. Tumours in the right and left side tend to present differently.

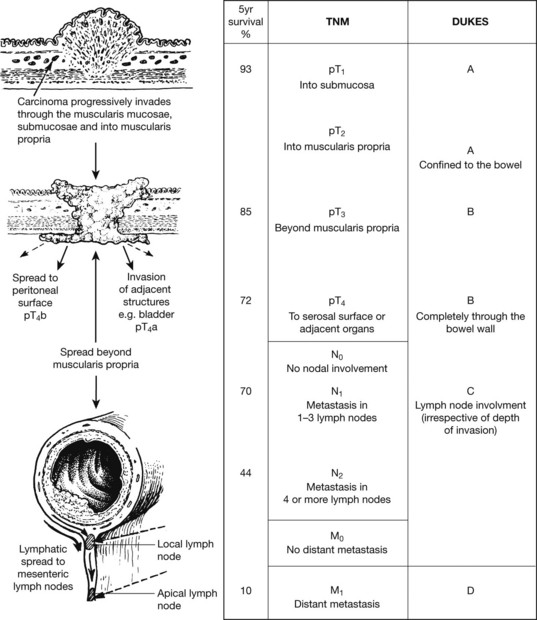

Spread and Staging (Dukes’ Staging)

Both Dukes’ staging and the TNM classification are used in routine practice. They correlate very well with prognosis. Both systems take into account extent of local invasion, lymph node involvement and distal metastases.

Blood borne metastases to the liver usually occur later. Extramural vascular invasion is a poor prognostic factor.

Tumours of Small Intestine

BENIGN TUMOURS: adenomas, leiomyomas and lipomas are rare, but may cause intussusception (p.327).

Hamartomatous polyps, consisting of glands and muscle, occur in the Peutz–Jeghers syndrome, an autosomal dominant condition. Melanotic pigmentation of the lips and mouth is also seen.

CARCINOMA: adenocarcinoma is 50 times rarer in the small intestine than in the colon. About half occur in the duodenum, mainly around the ampulla of Vater and often arise from adenomas. These present with obstructive jaundice. Tumours in the jejunum resemble those of the colon and may obstruct the lumen. An increased risk of carcinoma is seen in patients with Crohn’s disease, coeliac disease and the Peutz–Jeghers syndrome.

LYMPHOMA: these are non-Hodgkin’s lymphomas of ‘B’ or ‘T’ cell type.

Gastro Intestinal Stromal Tumours (GISTS)

GISTs occur within the stomach, small bowel and, less commonly, oesophagus and colon. They arise from precursors of the interstitial cells of Cajal (gut pacemaker cells). Mitotic activity and size are the main predictors of malignancy – peritoneal spread and liver metastasis.

Most are due to activating mutations of the c-kit gene and many respond to modern tyrosine kinase inhibitors.

GISTs arise within the muscle coat and often have a dumbell shape.

Carcinoid Tumours

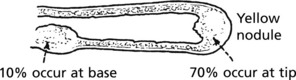

These tumours arise from endocrine cells and can occur in the gut and lung. They are commonest in the appendix and small bowel.

Appendiceal Carcinoids

These may be incidental findings at appendicectomy or may cause appendicitis.

Small Bowel Carcinoids

These are commonest in the ileum.

They contain neurosecretory granules (EM) and express endocrine markers, e.g. chromogranin, synaptophysin. The cells can bind and reduce silver compounds and are known as ‘argentaffin cells’.

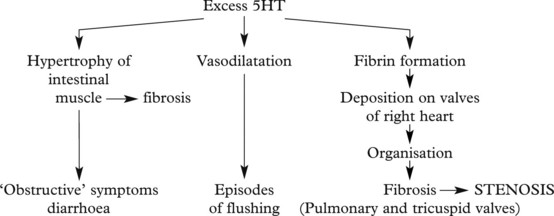

Carcinoid Syndrome

These tumours may secrete a variety of neuroendocrine and paraendocrine substances, in many cases without any apparent clinical functional effects.

However, ileal carcinoids tend to produce peptides: such as 5-hydroxytryptamine (5HT) (serotonin). This is normally destroyed in the liver and lungs: when metastatic deposits are present in the liver the active agents enter the general circulation and produce the carcinoid syndrome, characterised by episodic flushing, diarrhoea and right heart failure.

The Peritoneal Cavity

Peritonitis

Acute Peritonitis usually follows inflammation of a viscus, e.g.

Patients on chronic ambulatory peritoneal dialysis (CAPD) are prone to episodes of peritonitis.

Primary Peritonitis

In the absence of visceral inflammation, primary peritonitis may occur in children with the nephrotic syndrome (pneumococcus) or in adults with cirrhosis (usually coliforms).

Chronic Peritonitis

The most common type of chronic inflammation involving the peritoneum is that resulting from non-resolution of acute peritonitis.

A form of sclerosing peritonitis may complicate long term peritoneal dialysis.

Tuberculosis of the peritoneum is uncommon in Western countries, but frequent in developing countries. It commonly takes one of the following forms:

Ascites

Tumours

Secondary tumours are common, due to spread of carcinoma from the stomach, ovary and large intestine.

Eventually loops of bowel are stuck together by tumour and adhesions resulting in ‘frozen abdomen’.

Pseudomyxoma peritonei is seen when mucin secreting tumours, e.g. of ovary or appendix spread widely throughout the peritoneum.

Primary tumours are rare. Mesothelioma is the most important. It is related to the inhalation of asbestos and the pathology is similar to that of mesothelioma of the pleura; large white plaques of solid tumour. Primary carcinomas of the peritoneum are very similar to serous carcinomas of the ovary (p.511).