Chapter 10 Liver, Gall Bladder and Pancreas

Liver – Anatomy

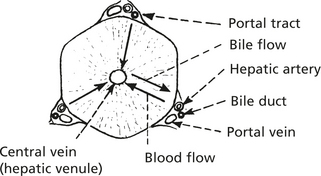

Conventionally the liver was considered to be composed of regular lobules, each arranged around a ‘central vein’ with portal tracts at the periphery.

The acinar concept is now used.

The smallest unit is the simple acinus.

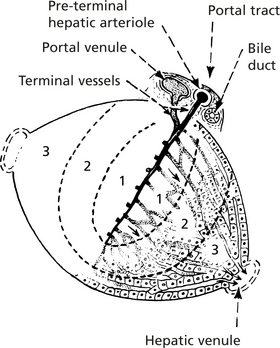

The portal venule and hepatic arteriole both send terminal branches into the acinus (2/3 of the blood supply is portal and 1/3 arterial). They join to form a common trunk which will then contain partially oxygenated blood, and this percolates through the sinusoids to several ‘terminal hepatic venules’ (as in diagram).

In terms of oxygen supply and other nutrients, 3 zones exist.

In Zone 1, glycogen synthesis and glycogenolysis take place. It is also the main area of protein metabolism and formation of plasma proteins. Conjugation of certain drugs takes place.

Zone 3 is associated with glycogen storage, lipid and pigment formation and metabolism of certain drugs and chemicals. Zone 2 shares functions with the other zones.

Anatomy – Hepatic Lesions

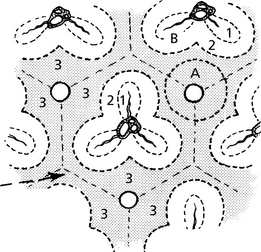

Adjacent liver acini form a complex architecture best appreciated when diseases affect the varying zones. Factors involved in this include the pO2 of blood and enzyme function of the zones.

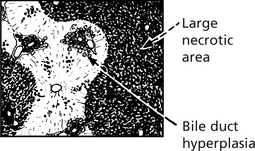

Liver Necrosis

Perivenular Necrosis

This form is a feature of many apparently unrelated conditions. It is brought about by damage in zone 3 (A in diagram). Thus it is a feature of shock due to circulatory collapse reducing the oxygen supply to zone 3. It also occurs in poisoning with chlorinated hydrocarbons (e.g. chloroform) and drugs, e.g. paracetamol, metabolised in zone 3.

It is important to realise that zone 3, particularly, is continuous from one acinus to another, and in severe cases the hepatic venules are linked together by necrotic tissues.

Mid-Zonal Necrosis

This is uncommon. It is seen in yellow fever and injury affecting zones 2 and 1 (B in diagram).

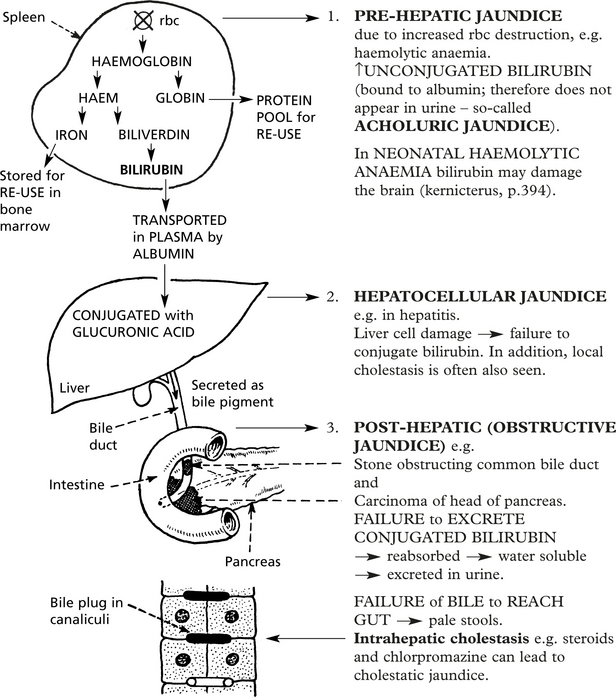

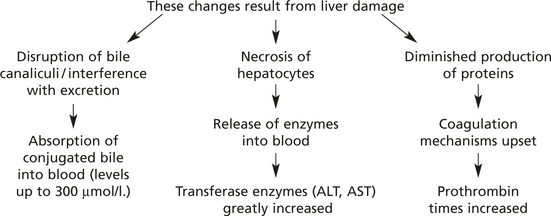

Jaundice

If the serum bilirubin level exceeds 50 μmol/l, the patient becomes jaundiced.

Bilirubin is derived from the breakdown of aged red cells by the macrophage system, mainly in the spleen. It is conjugated to glucuronic acid in the liver and secreted in the bile.

Study of haemoglobin catabolism shows 3 main forms of jaundice:

Viral Hepatitis

Acute Viral Hepatitis

Viral hepatitis is the most important form of hepatitis. It is seen worldwide. Viral hepatitis may be sporadic or epidemic and, depending on the responsible virus, transmitted by the faeco-oral or parenteral route.

Clinical Features

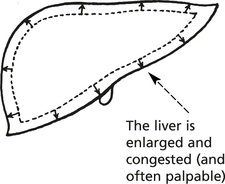

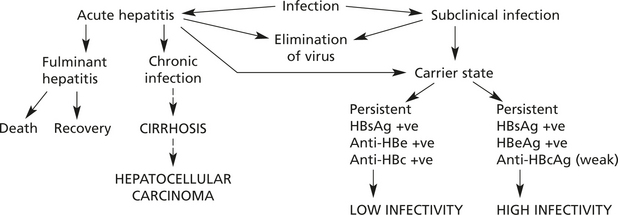

Many episodes of viral hepatitis are subclinical; mild symptomatic cases are characterised by nausea, fever and anorexia. Severe attacks are characterised by jaundice and hepatic failure, and may be fatal.

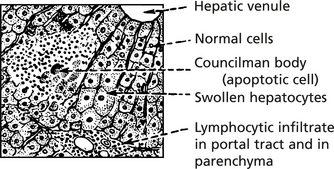

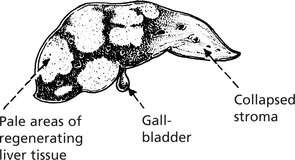

Pathological Features

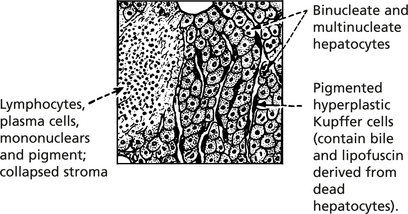

Liver cell necrosis is always present. It is most marked in Zone 3 (p.338).

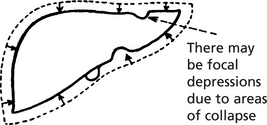

Liver is smaller, yellow or greenish

There is evidence of healing with mitotic activity in the hepatocytes.

Clinical Progress

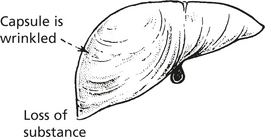

Remaining liver tissue opaque, yellowish, without markings and is largely necrotic

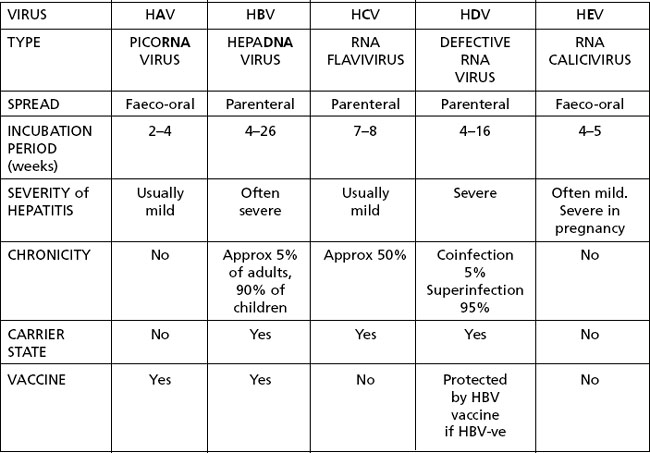

At least 5 viruses cause liver damage without significantly damaging other tissues (hepatitis A,B,C,D and E). The features are summarised and then discussed individually.

Other viruses which can affect the liver, but also affect other tissues include:

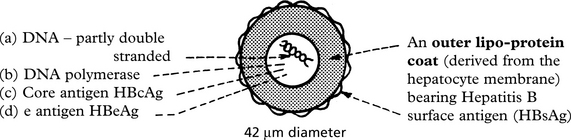

Hepatitis B Infection

The hepatitis B virus is a member of the HEPA DNA virus group. Infection is by the parenteral route – mainly IV drug abuse, blood products and sexual transmission, and in high prevalence areas in childbirth.

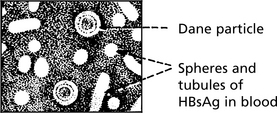

The virus has several components:

The complete virion is known as the Dane particle. Spherical and tubular structures derived from the surface coat can also be found in the peripheral blood.

These antigens and antibodies to them are the basis for diagnosis of hepatitis B infection.

HBsAg accumulates in the cytoplasm of cells – giving a ‘ground glass’ appearance.

or can be stained by immunocytochemistry.

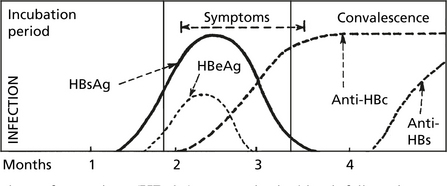

Serology: Antibodies to the various antigens appear in the blood.

Six weeks after infection the surface antigen (HBsAg) appears in the blood, followed two weeks later by the e antigen (HBeAg), at the time of maximal viral replication.

Viral Hepatitis

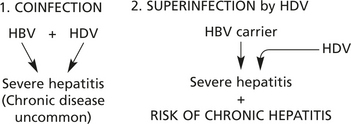

Hepatitis D

This is a defective RNA virus which requires HB virus for its release and infectivity. There are 2 patterns of infection:

Hepatitis C

This small RNA virus is transmitted parenterally and is seen in IV drug users or following infected blood transfusion. Acute hepatitis is mild and patients are rarely jaundiced. It is important because of the high risk of chronicity.

Hepatitis A

This picornavirus is transmitted by the faeco-oral route, especially where hygiene is poor. Hepatitis is usually mild in children, but more severe in adults. IgM antibodies appear in the blood in the acute phase, and IgG during convalescence, thus conferring life long immunity. Chronic liver disease does not occur.

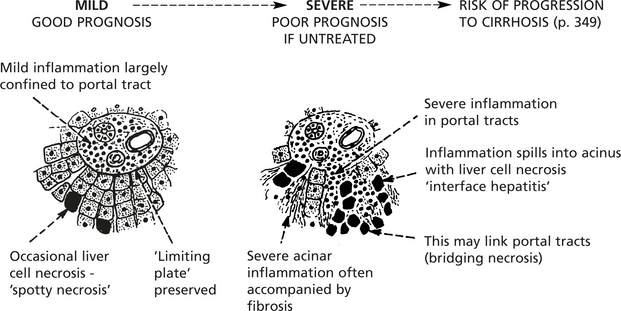

Chronic Hepatitis

Inflammation of the liver which lasts for more than 6 months is regarded as chronic. (This definition excludes disorders such as alcoholic hepatitis.)

Histologically, three areas of inflammation are seen to varying degrees.

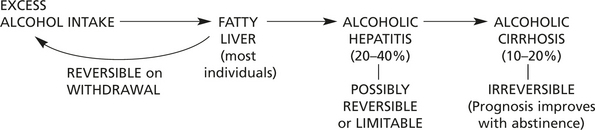

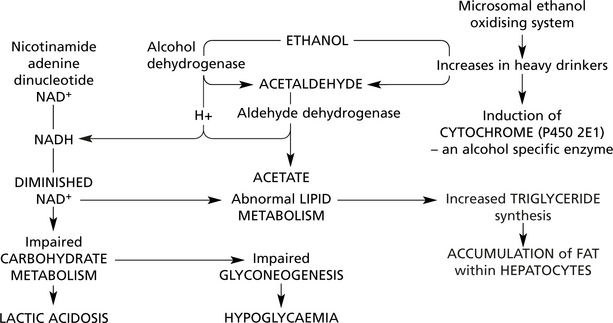

Alcoholic Liver Disease

Excess consumption of alcohol is associated with liver disease in three main forms.

The progression from left to right does not occur in all patients: genetic predisposition, coexistant nutritional deficiencies, amount and duration of drinking and other factors determine the risk.

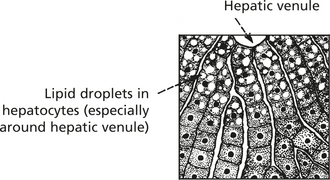

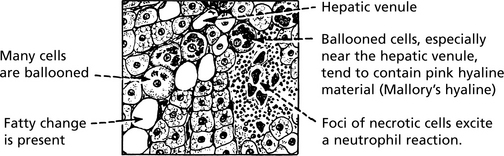

Alcoholic Hepatitis

In 20–40% of heavy drinkers, alcoholic hepatitis is superimposed on fatty change. This varies from asymptomatic hepatitis to a life threatening condition with nausea, vomiting, abdominal pain and jaundice. Signs of liver failure and portal hypertension may be found.

Histologically, the main features are seen around hepatic venules:

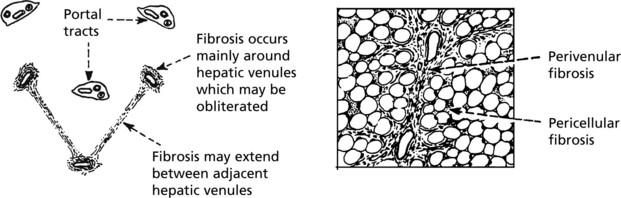

Progressing to Pericellular Fibrosis

Alcoholic hepatitis is important as a cause of liver damage, especially because of the high risk of progression to cirrhosis.

The term ‘nonalcoholic fatty liver disease’ covers a range of fatty disorders of the liver in non-drinkers. This includes simple fatty change and a histologically similar form of hepatitis to alcoholic hepatitis. Diabetes mellitus, severe obesity, jejuno-ileal bypass for obesity and certain drugs (e.g. amiodarone) appear to be responsible.

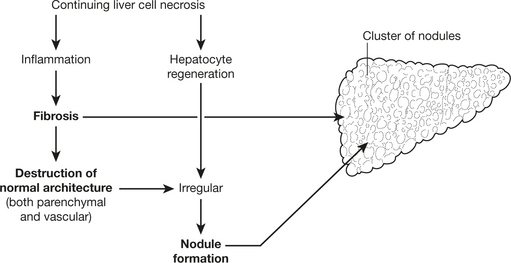

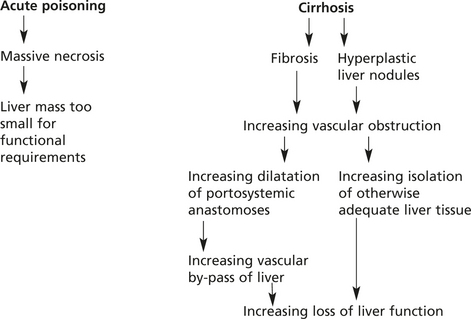

Cirrhosis

Cirrhosis is the end stage of many liver diseases. It is defined as:

A diffuse process (i.e. the whole liver is affected) characterised by fibrosis and conversion of the liver architecture into abnormal NODULES.

Aetiology

There are many causes including:

The mechanism common to all cirrhosis is:

Hepatic stellate (fat-storing) cells found in the Space of Disse are activated and transformed into myofibroblast-like cells under the influence of cytokines such as TGFα, PDGF and TGF-β. The activated cells synthesise collagen leading to fibrosis.

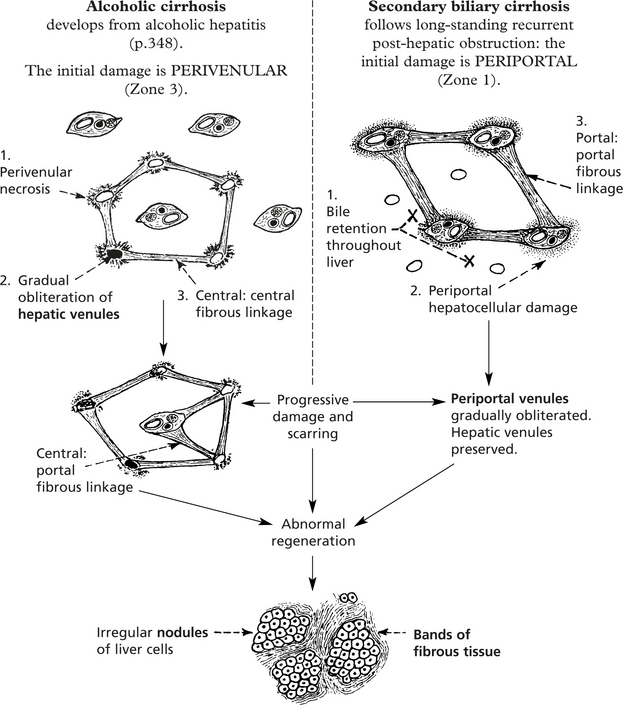

Cirrhosis

The initiating factor in the progression to cirrhosis is continuing hepatocellular damage. Its location within the acinus (p.338) and also its cause are reflected in the progression to irreversible damage.

The following contrasting diagrams illustrate the differing patterns in cirrhosis depending on the cause.

Biliary Disease

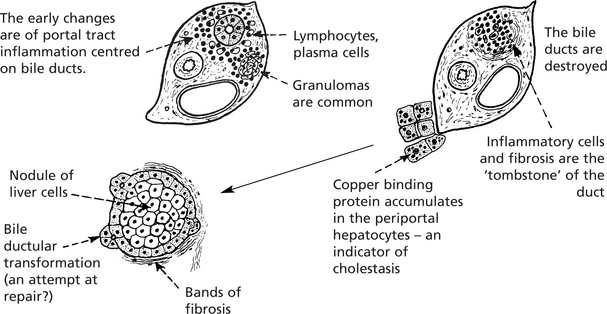

Primary Biliary Cirrhosis (PBC)

This is a chronic disorder mainly affecting middle-aged women. Destruction of intra-hepatic bile ducts leads to scarring and eventually to cirrhosis. Patients typically present with fatigue, itching (from bile salt retention) or jaundice. Hyperlipidaemia is common.

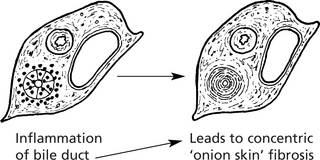

Primary Sclerosing Cholangitis

This disease also attacks bile ducts, both intra- and extrahepatic. Men are usually affected and there is a strong association with ulcerative colitis.

Retrograde cholangiography shows diagnostic changes in the extrahepatic ducts.

Strictures and outpouching can give a beaded appearance

The late effects are similar to PBC. Liver failure and bile duct carcinoma are frequent complications.

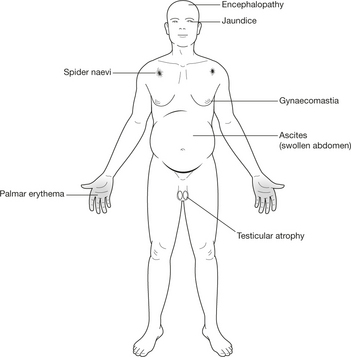

Hepatocellular Failure

Failure of Liver Function can be:

The mechanism is different in the 2 types.

The cardinal signs of hepatocellular failure are:

Other features include hypoglycaemia, acidosis and endocrine disturbances.

Hepatocellular Failure

Hepatic Encephalopathy

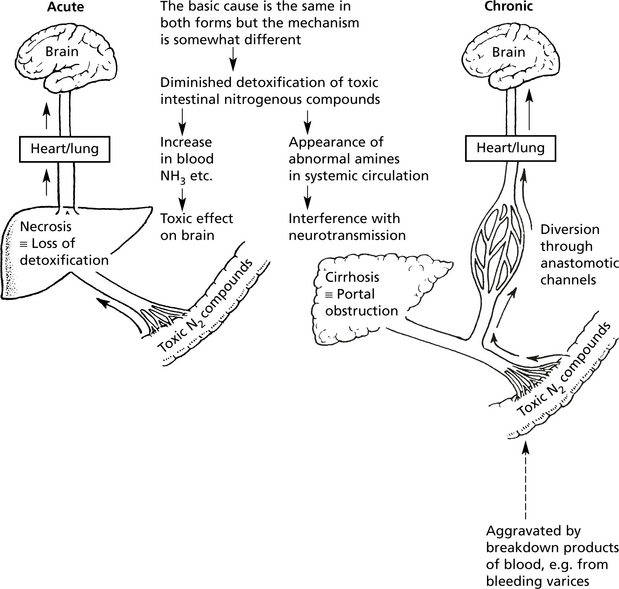

This term refers to the impaired mental state and neurological function due to liver failure. It takes the form of tremors, behavioural changes, convulsions, delirium, drowsiness and coma. In the acute form, severe symptoms such as convulsions, delirium and coma develop rapidly, while in chronic conditions milder changes are seen and coma is a late feature, unless a complication arises.

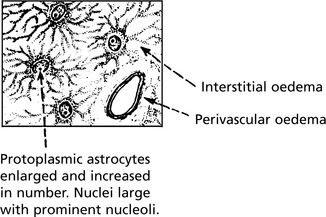

Despite the serious disturbances of function, pathological changes in the brain of fatal cases are surprisingly slight.

Liver transplantation is increasingly used to treat acute and chronic hepatocellular failure, as well as some small hepatocellular carcinomas. As with other transplanted organs, acute and chronic rejection are seen.

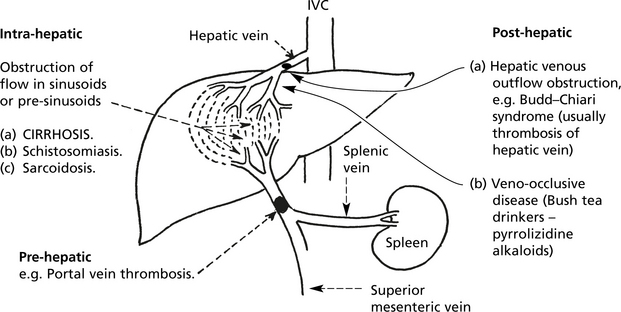

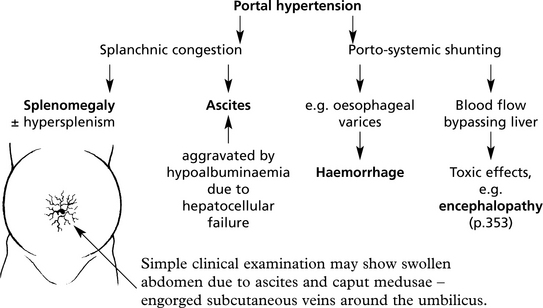

Portal Hypertension

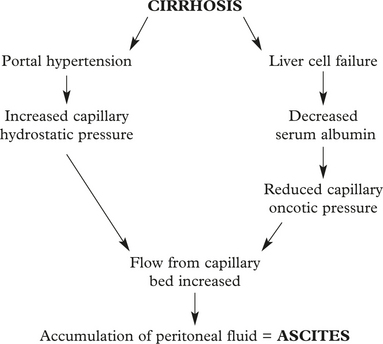

In cirrhosis of the liver, portal hypertension is also important.

Metabolic Disorders and the Liver

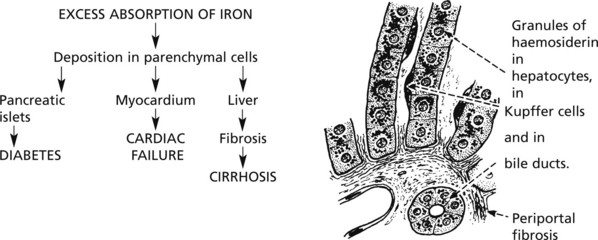

Haemochromatosis

Almost all cases are due to a mutation on chromosome 6, encoding the HFE protein which regulates iron absorption.

Although heterozygotes absorb excess iron, only homozygotes develop the disease.

Note: In the skin, the iron is deposited mainly in the sweat glands: excessive melanin production in the epidermis explains the term ‘bronzed diabetes’ for these cases.

HAEMOSIDEROSIS – Excess dietary iron and repeated blood transfusions may overload the body iron stores but cause less liver damage.

Wilson’s Disease (Hepato-Lenticular Degeneration)

A rare autosomal recessive condition (due to mutation of the ATP7B gene on chromosome 13 which encodes a copper transporting enzyme). This is characterised by accumulation of copper in the liver, brain (basal ganglia) and cornea (Kayser-Fleischer rings). Serum levels of caeruloplasmin (a copper binding protein) are reduced. The liver can show an acute hepatitis, chronic hepatitis or cirrhosis.

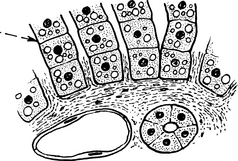

α1-Antitrypsin Deficiency

This enzyme is a protease inhibitor (Pi) produced mainly by the liver. Reduced levels or activity of the enzyme (abnormal forms coded by allelic variants) may result in liver damage.

Liver disease is found in most homozygotes (PiZZ) and presents as neonatal hepatitis, chronic active hepatitis or cirrhosis. Heterozygotes are rarely badly affected.

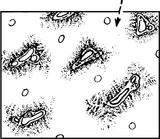

The abnormal enzyme is not secreted by liver cells and accumulates as globules in the periportal hepatocytes.

Note: α1-antitrypsin deficiency is an important factor in the development of emphysema (p.261).

Infections

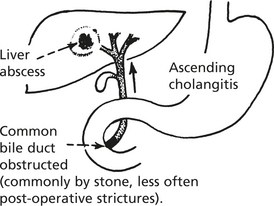

Pyogenic Infections

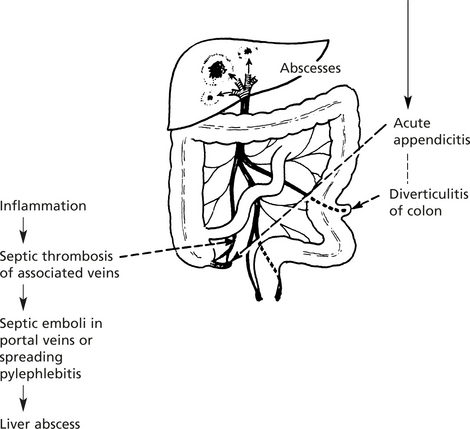

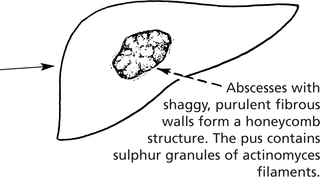

These are now much less common due to the use of antibiotics. Abscess of the liver, usually due to coliforms, occurs mainly in two conditions:

Infections

Spirochaetal Infections

Three spirochaetal infections can involve the liver.

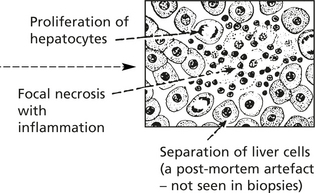

This organism is transmitted from rats to man, especially these working in wet conditions, e.g. in sewers and abbatoirs. The disease is characterised by fever, jaundice, haemorrhage into various organs, e.g. lungs, kidneys, and renal damage. The liver lesion is characteristic. Death may occur from intrapulmonary haemorrhage or renal failure.

Borrelia occur in many parts of the world and several species exist, e.g. B. recurrentis. They are transmitted by lice and ticks from animals acting as reservoirs, especially rodents. The infections produce peri-venular necrosis of the liver. Jaundice may be severe and liver failure can result in death.

Protozoal Diseases

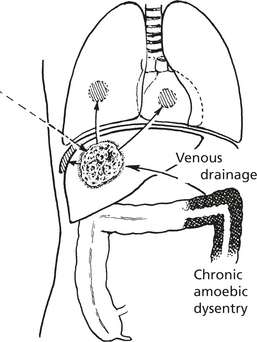

Amoebic ‘Abscess’

This is a complication of amoebic dysentery due to Entamoeba histolytica. The ‘abscess’ is usually single, in the upper right lobe of liver. An irregular fibrous wall encloses off necrotic liver cells, debris and red cells. Amoebae may be found in the inner wall. It may remain localised or track through the diaphragm into the lung, pleural or pericardial cavities.

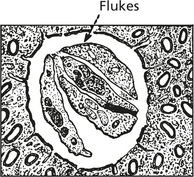

Metazoal Diseases Trematodes (Flukes)

Schistosomiasis (Bilharzia)

S. mansoni is common in Egypt and other parts of Africa. S. japonicum is found in China, Japan and the Philippines. Both infections involve the liver.

The schistosomes colonise the intestinal tract. They invade the intestinal veins; ova are released into the blood stream and embolise the portal venules of the liver. There is a focal granulomatous reaction which may lead to extensive portal fibrosis without cirrhosis. Portal hypertension can result with its associated complications.

Two other varieties of fluke disease exist — clonorchiasis (Chinese fish fluke) and fascioliasis (sheep fluke). Both produce an ascending cholangitis. Clonorchiasis can cause biliary obstruction and marked proliferation of bile ducts. Cholangiocarcinoma may develop. Infestation in both cases is due to eating raw or undercooked food.

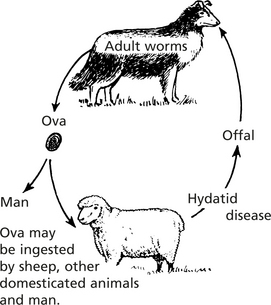

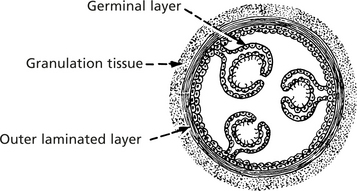

Hydatid Disease

This condition is caused by the embryos of Echinococcus granulosus, a small tapeworm. The disease is caught by close contact with animal reservoirs especially sheep and dogs. It is commonest in Australia, New Zealand, South America and the Middle East.

Digestion of the chitinous membrane by gastric juice releases the ova which invade the intestinal veins and reach the liver. Sometimes they pass into the systemic circulation and cysts form in the lungs, muscles, kidneys, spleen or brain.

The cyst may be very large, usually multilocular, due to budding of daughter cysts.

Tumours of the Liver

Primary Benign Tumours

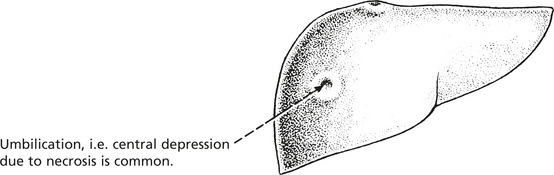

Secondary Tumours

The liver is by far the most frequent site of secondary tumour deposits and these are far commoner than primary liver tumours. The common primary sites are the gastrointestinal tract, the lung and breast. Melanoma, leukaemic infiltration and involvement by lymphoma are also often seen.

The metastases often grow rapidly and are frequently the main cause of death. An exception is metastatic carcinoid tumour which grow slowly over a period of years (p.334).

Increasingly, metastases, e.g. from colorectal cancers, are treated by radio frequency ablation or surgical resection.

Primary Carcinoma of Liver

Hepatocellular Carcinoma (HCC)

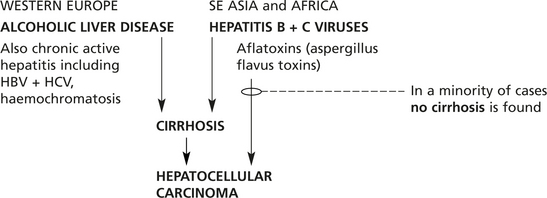

This, the commonest primary malignancy of the liver, is unusual in Western Europe, but is very common in Africa and South-East Asia. Males are particularly affected.

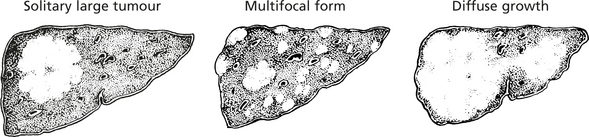

Three main types of growth are described:

In all three forms the liver is often cirrhotic (80%) (particularly in the West).

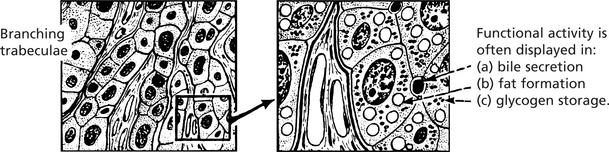

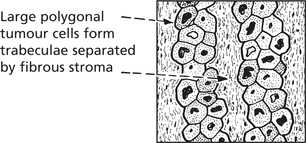

Histological structure: The cells grow in columns resembling normal liver.

Spread

In addition to diffuse growth within the liver, invasion of hepatic veins occurs early and there may be metastases to lung, bone and also the draining lymph nodes.

The proximate cause of death may be (i) liver failure, (ii) the complications of portal hypertension (especially in cirrhotic patients) and (iii) massive intraperitoneal haemorrhage.

Systemic manifestations include hypoglycaemia, hypercalcaemia and polycythaemia (due to production of erythropoietin).

Diagnosis

Liver biopsy is usually required. High levels of alpha-fetoprotein (normally produced in the fetal liver), >500 μg/l are strong supportive evidence (not all tumours produce this protein). This can be demonstrated in tumour cells by immunostaining. In-situ hybridisation can show mRNA for albumin in αFP-negative tumours.

Primary Liver Cell Tumours

Fibrolamellar Carcinoma

This uncommon variant (<5%) occurs especially in young adults. It is important because the prognosis is much better following surgical resection.

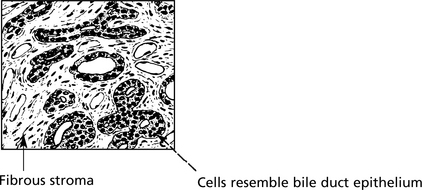

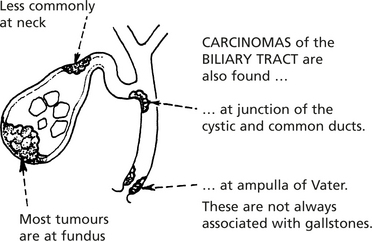

Cholangiocarcinoma

These tumours arise from bile ducts at both intra-and extrahepatic sites.

They are usually adenocarcinomas: some show excess mucus secretion and evoke a dense fibrous response.

There is an increased incidence in association with ulcerative colitis and primary sclerosing cholangitis, and in the Far East there is a clear association with liver fluke (clonorchis) infestation.

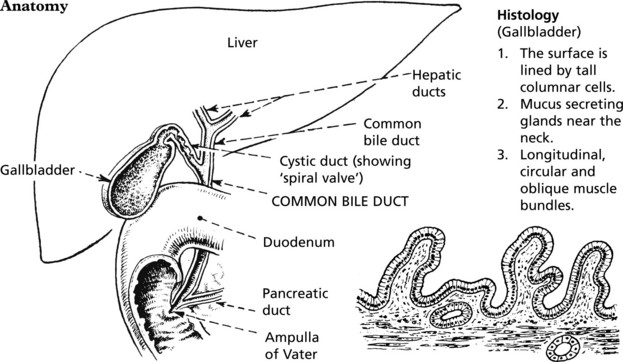

Gallbladder And Bile Duct – Anatomy

The function of the gallbladder is to concentrate and store bile.

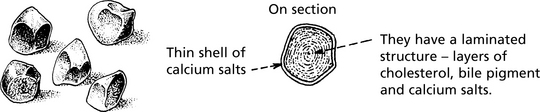

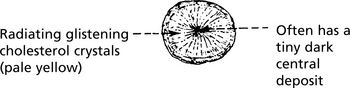

Gallstones

Gallstones are the principal cause of gallbladder disease and its consequences.

Gallstones

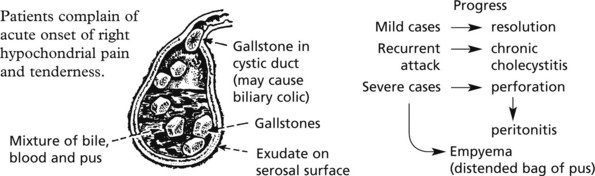

Clinical Manifestations and Complications

Many patients are asymptomatic or have only mild dyspepsia; others develop symptomatic complications.

In the majority of cases the symptoms are of vague ‘indigestion’, intolerance of fatty foods and vague right hypochondrial pain: in some cases there is a history of acute attacks.

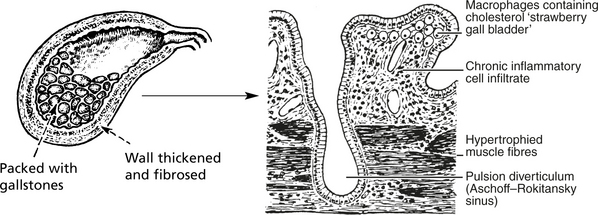

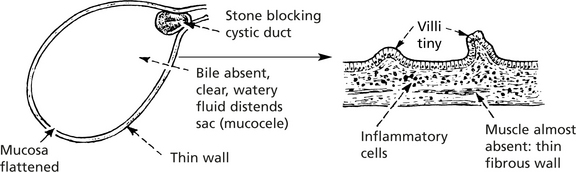

This occurs when there has been long-standing obstruction of the cystic duct.

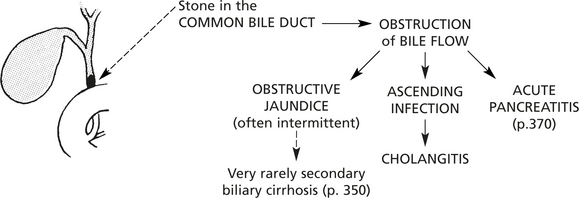

Note: In addition to jaundice, persistent skin itching, due to retention of bile salts, may occur.

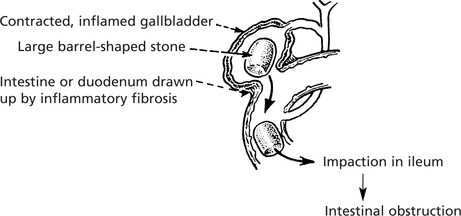

Very rarely a stone may ulcerate through the gallbladder into the intestine and cause obstruction.

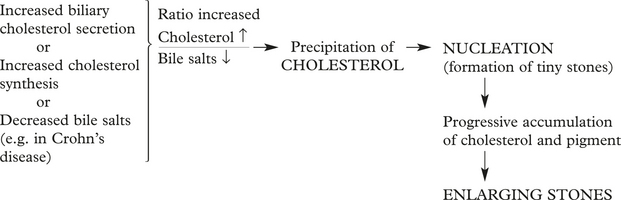

Gallstones – Aetiology

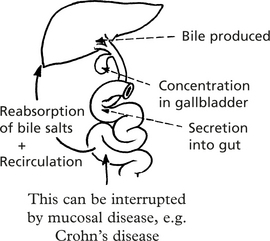

Although gallstones are found in 10–20% of the population, the prevalence increasing with age, the exact mechanisms of their formation remain incompletely understood. Risk factors include (a) female gender, (b) obesity, (c) pregnancy, (d) drugs such as the cholesterol lowering drug clofibrate now seldom used and (e) gastrointestinal disease, e.g. Crohn’s disease.

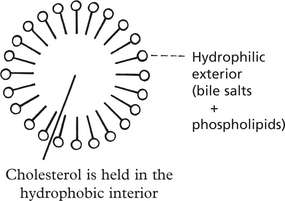

The principal constituents of bile are cholesterol, phospholipids and bile acids (cholic acid and chenodeoxycholic acid).

The stability of cholesterol depends on adequate amounts of bile acids. Micelles are formed.

Their enterohepatic circulation is essential to maintain adequate concentrations of bile salts.

The ratio of cholesterol:bile salts is very important.

Stones often lead to infection: it is likely that infection promotes further stone production.

These mechanisms are responsible for cholesterol and mixed stones. Pigment stones are seen in haemolytic anaemia, but also in relation to infection, e.g. of E. coli. The mechanisms are poorly understood.

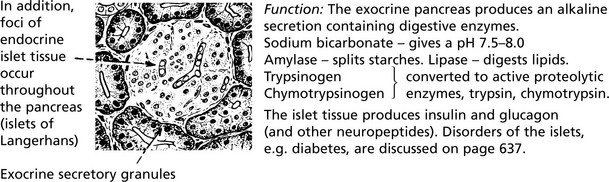

Pancreas

The exocrine glandular portion of the pancreas produces digestive secretions which are released into the second part of the duodenum.

Microscopically, the exocrine tissue is similar to salivary glands.

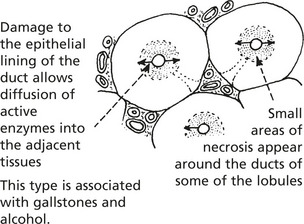

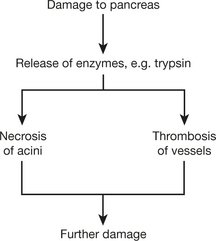

There is evidence that mild pancreatitis is not uncommon but, in a significant number of cases, progression to a severe fatal disease occurs. Clinically, there is an acute abdominal emergency with pain and shock.

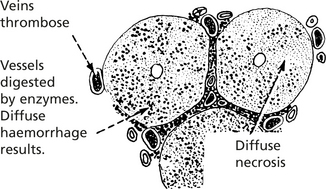

The essential pathological changes are due to tissue necrosis caused by the action of liberated enzymes on the pancreatic tissues. The severity of the lesion depends on the amount of enzyme set free, the distance it diffuses, anti-proteolytic factors and the structures affected.

Acute Pancreatitis

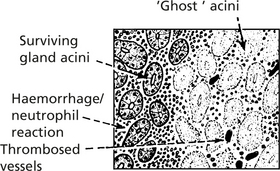

Early changes are seen in centre of the lobules.

Periductal necrosis – in the centre of each affected lobule.

This type is associated with gallstones and alcohol.

Unless this damage is inhibited by α1 antitrypsin and α2 macroglobulins from the blood and pancreatic secretory trypsin inhibitor, inflammation progresses to:

Panlobular Pancreatitis

Release of enzymes beyond the pancreas gives fat necrosis of the omentum.

Opaque white patches of necrotic fatty tissue containing free fatty acids - due to action of phospholipase and proteolytic enzymes - lipase splits fat.

In acute pancreatitis, acute inflammation is associated with necrosis of pancreatic acini and fat.

Patients present with abdominal pain and vomiting with a differential diagnosis of perforated duodenal ulcer. A serum level of amylase >1200 IU/L and serum lipase >160 IU/L confirms the diagnosis. Many cases are mild, but a third of severe cases have a mortality of 50%.

Gallstones

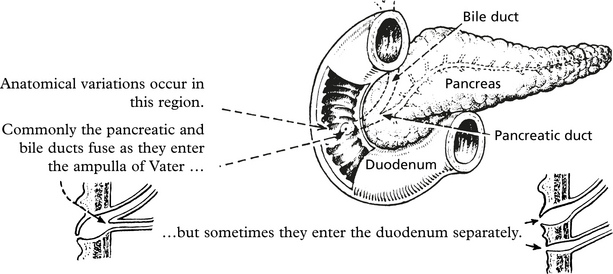

Between 40 and 60% of all cases of severe pancreatitis are associated with gallstones. Recurrent attacks are common.

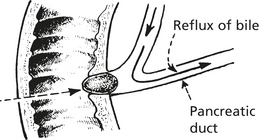

Bile Reflux is the Initiating Event

In most patients, the bile duct and pancreatic duct have a common entrance to the ampulla of Vater. Stones around 3 mm in diameter passing down the bile duct can, by blocking the ampulla, cause reflux of bile along the pancreatic duct.

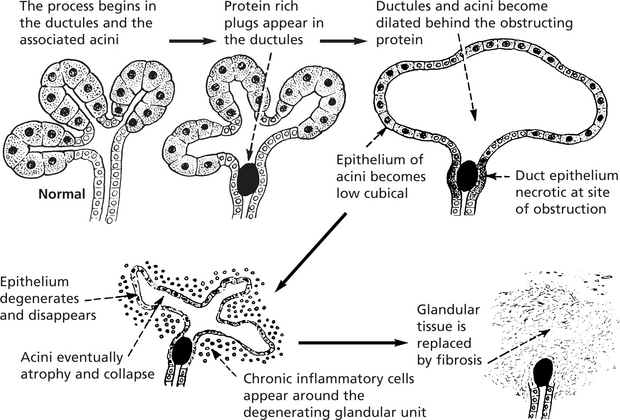

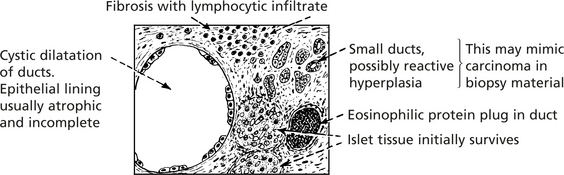

Chronic Pancreatitis

Chronic pancreatitis predominantly affects alcoholics.

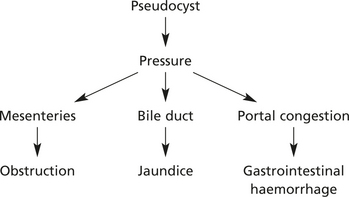

The change is focal. More and more protein plugs form, some in larger ducts. Obstruction of these may lead to production of cysts.

Ultimately, a large proportion of the exocrine tissue is destroyed.

With progress of the disease, two other developments take place:

Rupture into the peritoneal cavity causes ascites, frequently haemorrhagic.

Progressive destruction of the parenchyma with fibrosis may ultimately convert the pancreatitis into a thin hard cord.

Effects

Patients typically complain of abdominal pain.

Apart from the complications due to cyst rupture, destruction of pancreatic tissue may lead to:

Aetiology

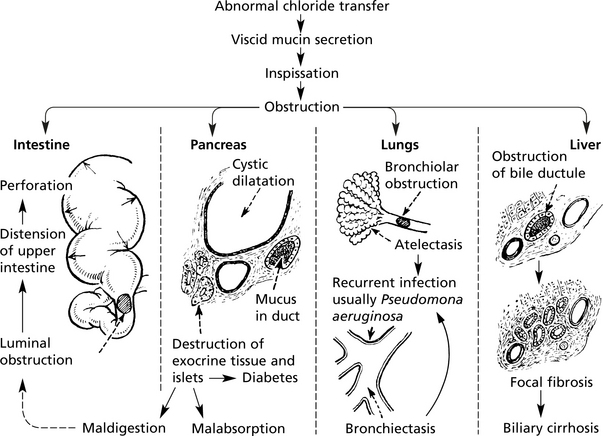

Cystic Fibrosis (Mucoviscidosis)

This is a common autosomal recessive inherited disease due to genetic mutation on chromosome 7; a high percentage (about 4%) of the population are carriers.

The gene involved is called cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator (CFTR). Its essential function is the control of the transfer of chloride across cell membranes. Many mutations of the gene have been recorded, each being responsible for subtle variations in the evolution of the disorder.

All the exocrine secretory tissues are affected to some extent: the clinical features vary according to which organs are severely affected – pancreas, bronchi, bowel, biliary tree, testis.

Clinical Features

Neonatal

Intestinal obstruction (meconium ileus) may lead to intestinal perforation and fatal peritonitis.

Childhood

There is failure to thrive due to maldigestion and malabsorption, and steatorrhea is common – all features of pancreatic insufficiency. Recurrent episodes of pneumonia often lead to death in early adult life. Lung transplantation and gene therapy offer hope of improved survival. Liver lesions develop later.

Sodium chloride levels are raised in sweat detected in the ‘sweat test’. Genetic screening is now available.

Tumours of Pancreas

Benign tumours of the pancreas such as cystadenomas are rare. They may produce symptoms due to pressure on other structures.

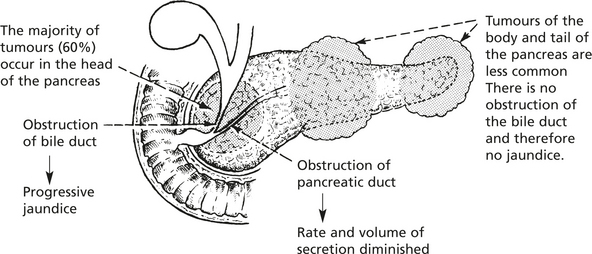

Carcinoma

Local spread and/or distant metastases are found in 85% of cases at the time of diagnosis and the 5 year survival rate is 3–5%.

The tumour arises from the duct epithelium and in almost all cases it is an adenocarcinoma. Papillary cystadenocarcinoma, adenosquamous carcinoma and giant cell carcinoma are forms occasionally encountered.

Tumours in the body and tail are commonly larger than tumours of the head, probably due to later diagnosis in the relative absence of symptoms.

Thrombosis of unknown cause and at distant sites (thrombophlebitis migrans, p. 236), e.g. femoral vein, may occur.

Aetiology

Endocrine Tumours are described on page 641.