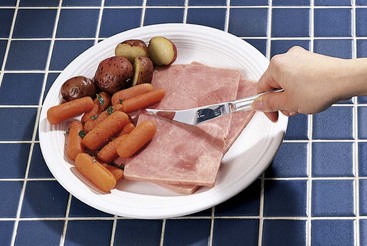

1. Activities of daily living for patients with incoordination, limited range of motion, paraplegia, quadriplegia, and hemiplegia. Cleveland: Metro Health Center for Rehabilitation, Metro Health Medical Center for Rehabilitation, 1968. [(rev. 1989)].

2. Alley, DE, et al. The changing relationship of obesity and disability, 1988-2004. JAMA. 2007;298(17):2020–2027.

3. American Occupational Therapy Association. Occupational therapy practice framework: domain & process, ed 2. Am J Occup Ther. 2008;62(6):625–688.

4. Anemaet, WK, et al. Home rehabilitation: guide to clinical practice. St. Louis: Mosby; 2000.

5. Arilotta, C. Performance in areas of occupation: the impact of the environment. Phys Disabil Special. 2003;26:1.

6. Armstrong, M, Lauzen, S. Community integration program, ed 2. Enumclaw, WA: Idyll Arbor; 1994.

7. Asher, IE. Occupational therapy assessment tools: an annotated index, ed 3. Bethesda, MD: American Occupational Therapy Association; 2007.

8. Baum, CM, Connor, LT, Morrison, T, et al. Reliability, validity, and clinical utility of the executive function performance test: a measure of executive function in a sample of people with stroke. AJOT. 2008;62:446–455.

9. Baum, CM, Morrison, T, Hahn, M, et al. Test manual: Executive Function Performance Test. St. Louis: Washington University; 2003.

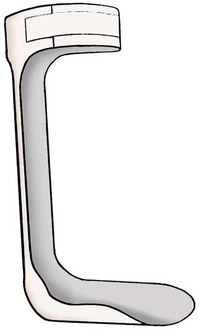

10. Bergstrom, N. Adaptations for activities of daily living. In Practical manual for physical medicine and rehabilitation. St. Louis: Elsevier Mosby; 2006.

11. Bromley, I. Tetraplegia and paraplegia: a guide for physiotherapists, ed 6. London: Churchill Livingstone Elsevier; 2006.

12. Christiansen, CH, Matuska, KM. editors: Ways of living: adaptive strategies for special needs,, ed 3. Bethesda, MD: American Occupational Therapy Association; 2004.

13. Clark, FA. The concept of habit and routine: a preliminary theoretical synthesis. Occup Ther J Res. 2000;20:1235–1375.

14. Cynkin, S, Robinson, AM. Occupational therapy and activities health: toward health through activities. Boston: Little, Brown; 1990.

15. Department of Justice. Americans with Disabilities Act of 1990 incorporating changes made by the ADA Amendments Act of 2008. www.ada.gov. [Accessed April 2011].

16. Department of Justice: Technical Assistance to the States Act.

17. Fiese, BH, Tomcho, TJ, Douglas, M, et al. A review of 50 years of research on naturally occurring family routines and rituals: cause for celebration? J Family Psych. 2002;16:381–390.

18. Fisher, AG. Assessment of motor and process skills (AMPS). Fort Collins, CO: Three Star Press; 2003.

19. Foti, D. Caring for the person of size. OT Practice. 2005;7:9–14. [Feb].

20. Foti, D, Littrell, E. Bariatric care: practical problem solving and interventions. Physical Disabilities Special Interest Section Quarterly. 27(4), 2004.

21. Girdler, S, et al. The impact of age-related vision loss. OTJR: Occupation, Participation and Health. 2008;28(3):P110–P120.

22. Herget, M. New aids for low vision diabetics. Am J Nurs. 1989;89(10):1319–1322.

23. Hinojosa, J. Position paper: broadening the construct of independence. Am J Occup Ther. 2008;56(6):660.

24. Katz, N, Tadmore, I, Felzen, B, Hartman-Maeir, A. Validity of the Executive Function Performance Test in individuals with schizophrenia. Occup Ther J Res. 2007;27:1–8.

25. Klinger, JL. Mealtime manual for people with disabilities and the aging. Thorofare, NJ: Slack; 1997.

26. Law, ML, et al. Canadian occupational performance measure (COPM), ed 4. Ottawa: CAOT; 2010.

27. Letts, L, Law, M, Rigby, P, et al. Person-environment assessments in occupational therapy. Am J Occup Ther. 1994;48:608.

28. The Lighthouse store: Adaptations. San Francisco www.store.lighthouse-sf.org, 2010.

29. Malick, MH, Almasy, BS. Activities of daily living and homemaking. In Hopkins HL, Smith HD, eds.: Willard and Spackman’s occupational therapy, ed 7, Philadelphia: JB Lippincott, 1988.

30. Maxi aids and appliances for independent living. Farmingdale, NY, Maxi Aids www.maxiaids.com.

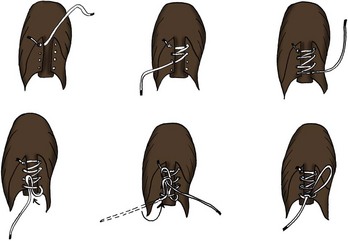

31. McBearson, G. Dressing parts 1 and 2. www.youtube.com/watch?v=RR1nd3J5aWQ. [Accessed 2010].

32. Niestadt, ME. Introduction to evaluation and interviewing. In Neistadt ME, Crepeau EB, eds.: Willard and Spackman’s occupational therapy, ed 9, Philadelphia: Williams & Wilkins, 1998.

33. Orr, AL. Issues in aging and vision: a curriculum for university programs and in-service training. New York: American Foundation for the Blind Press; 1998.

34. Radomski, M, Trombly, CA. Occupational therapy for physical dysfunction, ed 6. Baltimore: Williams & Wilkins; 2008.

35. Reynolds, SL, et al. The impact of obesity on active life expectancy in older American men and women. Gerontol.

36. Runge, M. Self-dressing techniques for clients with spinal cord injury. Am J Occup Ther. 1967;21:367.

37. Scheiman, M, et al. Low vision rehabilitation: a practical guide for occupational therapists. Thorofare, NJ: Slack; 2007.

38. Steggles, E, Leslis, J. Electronic aids to daily living. Home & Community Health Special Interest Quarterly. 2001;8:1.

39. Sturn, R, et al. Increasing obesity rates and disability trends. Health Affairs. 2004;23(2):199–205.

40. Uniform Data System for Medical Rehabilitation. Functional independence measure (FIM). Buffalo, NY: State University of New York at Buffalo; 1993.

41. United States Consumer Product Safety Commission. Tap water scalds, Document #5089. www.cpsc.gov. [Accessed August 2010].

42. Vital Recipe 2010. Cooking gadgets, wheelchair tips. www.vitalrecipe.com.

43. Yano, E, Working with the older adult with low vision: home health OT interventions. presentation at Kaiser Permanente Medical Center Home Health Department, Hayward, CA, 1998.

44. Yasuda, YL, Leiberman, D. Adults with rheumatoid arthritis: practice guidelines series. Bethesda: American Occupational Therapy Association; 2001.

45. Zahoransky M: Home & Community Health Special Interest Section Quarterly/American Occupational Therapy Association, Bethesda: 16(4)1, 3.