Bacterial Infections

IMPETIGO

Impetigo is a superficial infection of the skin that is caused by Streptococcus pyogenes (group A streptococcus) and Staphylococcus aureus, either separately or together. The term impetigo is derived from a Latin word meaning “attack,” because of its common presentation as a scabbing eruption. Two clinically distinctive patterns are seen, nonbullous impetigo and bullous impetigo. Intact epithelium is normally protective against infection; therefore, many cases arise in damaged skin such as preexisting dermatitis, cuts, abrasions, or insect bites. Secondary involvement of an area of dermatitis has been termed impetiginized dermatitis. An increased prevalence is associated with debilitating systemic conditions such as human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection, type 2 diabetes mellitus, or dialysis.

CLINICAL FEATURES: Nonbullous impetigo (impetigo contagiosa) is the more prevalent pattern and occurs most frequently on the legs, with less common involvement noted on the trunk, scalp, or face. The facial lesions usually develop around the nose and mouth. In many patients with facial involvement, the pathogenic bacteria are harbored in the nose and spread onto the skin into previously damaged sites such as scratches or abrasions. Often, facial lesions will have a linear pattern that corresponds to previous fingernail scratches. The infection is more prevalent in school-aged children but also may be seen in adults. The peak occurrence is during the summer or early fall in hot, moist climates. Impetigo is contagious and easily spread in crowded or unsanitary living conditions.

Nonbullous impetigo initially appears as red macules or papules, with the subsequent development of fragile vesicles. These vesicles quickly rupture and become covered with a thick, amber crust (Fig. 5-1). The crusts are adherent and have been described as “cornflakes glued to the surface.” Some cases may be confused with exfoliative cheilitis (see page 304) or recurrent herpes simplex (see page 243). Pruritus is common, and scratching often causes the lesions to spread (Fig. 5-2). Lymphangitis, cellulitis, fever, anorexia, and malaise are uncommon, although leukocytosis occurs in about half of affected patients.

Bullous impetigo usually is caused by S. aureus and also has been termed staphylococcal impetigo. Like the nonbullous form, it most frequently affects the extremities, trunk, and face. Infants and newborns are infected most commonly, but the disease also may occur in children and adults. The lesions are characterized by superficial vesicles that rapidly enlarge to form larger flaccid bullae. Initially, the bullae are filled with clear serous fluid, but the contents of the bullae quickly become more turbid and eventually purulent. Although the bullae may remain intact, they usually rupture and develop a thin brown crust that some describe as “lacquer.” Weakness, fever, and diarrhea may be seen. Lymphadenopathy and cellulitis are unusual complications. Meningitis and pneumonia are very rare but may lead to serious complications, even death.

DIAGNOSIS: A strong presumptive diagnosis can normally be made from the clinical presentation. When the diagnosis is not obvious clinically or the infection fails to respond to standard therapy within 7 days, the definitive diagnosis requires isolation of S. pyogenes or S. aureus from cultures of involved skin.

TREATMENT AND PROGNOSIS: For patients with nonbullous impetigo involving only a small area with few lesions, topical mupirocin has been shown to be effective. Fusidic acid (available in Europe, not in the United States) also has been very effective; however, increasing reports of resistance are diminishing its use. Removal of the crusts with a clean cloth soaked in warm soapy water is recommended before application of topical therapy, rather than placing the medication on inert, dried, exfoliating skin. For bullous or more extensive lesions, topical antibiotic drugs often are insufficient; the treatment of choice is a 1-week course of a systemic oral antibiotic. The best antibiotic is one that is effective against both S. pyogenes and penicillin-resistant S. aureus. Cephalexin, trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole, dicloxacillin, flucloxacillin, and amoxicillin-clavulanic acid represent good current choices. Erythromycin or clindamycin can be used in patients sensitive to penicillin, but resistance by S. aureus to erythromycin has become an increasing problem. If left untreated, then the lesions often enlarge slowly and spread. Serious complications, such as acute glomerulonephritis, are rare but possible in prolonged cases. Inappropriate diagnosis and treatment with topical corticosteroids may produce resolution of the surface crusts, but infectious, red, raw lesions remain.

ERYSIPELAS

Erysipelas is a superficial skin infection most commonly associated with b-hemolytic streptococci (usually group A, such as Streptococcus pyogenes, but occasionally other groups such as group C, B, or G). Other less common causative organisms include Staphylococcus aureus, Streptococcus pneumoniae (i.e., pneumococcus), Klebsiella pneumoniae, Yersinia enterocolitica, and Haemophilus influenzae. The infection rapidly spreads through the lymphatic channels, which become filled with fibrin, leukocytes, and streptococci. Although also associated with ergotism, the term Saint Anthony’s fire has been used to describe erysipelas. Because the French House of St. Anthony, an eleventh-century hospital, had fiery red walls similar to the color of erysipelas, the term Saint Anthony’s fire was used to describe this disease. Today, classical facial erysipelas is a rare and often forgotten diagnosis. At times, the appropriate diagnosis has been delayed because of confusion with facial cellulitis from dental infections.

CLINICAL FEATURES: Erysipelas tends to occur primarily in young and older adult patients or in those who are debilitated, diabetic, immunosuppressed, obese, or alcoholic. Patients who have areas of chronic lymphedema or large surgical scars (such as postmastectomy or saphenous venectomy) also are susceptible to this disease. The infection may occur anywhere on the skin, especially in areas of previous trauma. The most commonly affected site is the leg in areas affected by tinea pedis (athlete’s foot). The face, arm, and upper thigh also frequently are infected. In facial erysipelas, an increased prevalence is noted in the winter and spring months, whereas summer is the peak period of involvement of the lower extremities.

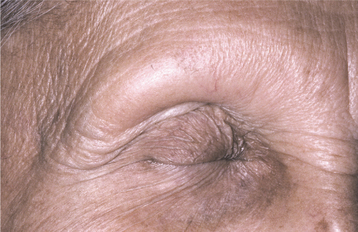

When lesions occur on the face, they normally appear on the cheeks, eyelids, and bridge of the nose, at times producing a butterfly-shaped lesion that may resemble lupus erythematosus (see page 794). If the eyelids are involved, then they may become edematous and shut, thereby resembling angioedema (see page 356). The affected area is painful, bright red, well circumscribed, swollen, indurated, and warm to the touch (Fig. 5-3). Often the affected skin will demonstrate a surface texture that resembles an orange peel (peau d’orange). High fever and lymphadenopathy often are present. Lymphangitis, leukocytosis, nausea, and vomiting occur infrequently. Diagnostic confirmation is difficult because cultures usually are not beneficial.

TREATMENT AND PROGNOSIS: The treatment of choice is penicillin. Alternative antibiotic drugs include macrolides such as erythromycin, cephalosporins such as cephalexin, and fluoroquinolones such as ciprofloxacin. On initiation of therapy, the area of skin involvement often enlarges, probably secondary to the release of toxins from the dying streptococci. A rapid resolution is noted within 48 hours. Without appropriate therapy, possible complications include abscess formation, gangrene, necrotizing fasciitis, toxic shock syndrome with possible multiple organ failure, thrombophlebitis, acute glomerulonephritis, septicemia, endocarditis, and death. Recurrences may develop in the same area, most likely in a previous zone of damaged lymphatics or untreated athlete’s foot. With repeated recurrences, permanent and disfiguring enlargements may result. In cases with multiple recurrences, prophylaxis with oral penicillin has been used.

STREPTOCOCCAL TONSILLITIS AND PHARYNGITIS

Tonsillitis and pharyngitis are extremely common and may be caused by many different organisms. The most common causes are group A, b-hemolytic streptococci, adenoviruses, enteroviruses, influenza, parainfluenza, and Epstein-Barr virus. Although a virus causes the majority of pharyngitis cases, infection with group A streptococci is responsible for 15% to 30% of acute pharyngitis cases in children and 5% to 10% of cases in adults. Adults who are parents of school-aged children or work in close association with children are at increased risk for developing this infection. Spread is typically by person-to-person contact through respiratory droplets or oral secretions, with a short incubation period of 2 to 5 days. Uncommonly, outbreaks of streptococcal pharyngitis have been associated with contaminated food, often inappropriately handled cold salads containing foodstuffs such as eggs, mayonnaise, tuna, potatoes, or cheese.

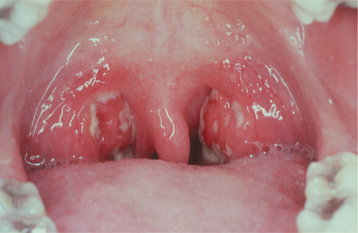

CLINICAL FEATURES: Although the infection can occur at any age, the greatest prevalence occurs in children 5 to 15 years old, with most cases in temperate climates arising in the winter or early spring. The signs and symptoms of tonsillitis and pharyngitis vary from mild to intense. Common findings include sudden onset of sore throat, temperature of 101° to 104° F, dysphagia, tonsillar hyperplasia, redness of the oropharynx and tonsils, palatal petechiae, cervical lymphadenopathy, and a yellowish tonsillar exudate that may be patchy or confluent (Fig. 5-4). Other occasional findings include a “beefy” red and swollen uvula, excoriated nares, and a scarlatiniform rash (see next topic). Systemic symptoms, such as headache, malaise, anorexia, abdominal pain, and vomiting, may be noted, especially in younger children. Conjunctivitis, coryza (rhinorrhea), cough, hoarseness, discrete ulcerative lesions, anterior stomatitis, absence of fever, a viral exanthem, and diarrhea typically are associated with the viral infections and normally are not present in streptococcal pharyngotonsillitis.

DIAGNOSIS: Although the vast majority of pharyngitis cases are caused by a viral infection, reviews have shown that about 70% of adults in the United States receive antibiotic therapy. In an attempt to minimize overuse, antibiotics should not be prescribed without confirmation of bacterial infection. Except for very rare infections such as Corynebacterium diphtheriae (see page 186) and Neisseria gonorrhoeae (see page 193), antibiotics are of no benefit for acute pharyngitis except for those related to group A streptococci.

Patients exhibiting features strongly suggestive of a viral infection (see previous section) should not receive antibiotic therapy or microbiologic testing for streptococcal infection. Because the clinical features of streptococcal pharyngitis overlap those of viral origin, the diagnosis cannot be based solely on clinical features; however, laboratory testing of all patients with sore throat cannot be justified. Diagnostic testing is recommended only for those patients with clinical and epidemiologic findings that suggest streptococcal infection or for those in close contact with a well-documented case. Although less sensitive than throat culture, rapid antigen detection testing provides quick results and exhibits good sensitivity and specificity. If negative results are obtained in children, then confirmatory throat cultures should be performed.

TREATMENT AND PROGNOSIS: Streptococcal pharyngitis usually is self-limited and resolves spontaneously within 3 to 4 days after onset of symptoms. In addition to reducing the localized morbidity of the infection, the main goals of therapy are to prevent development of acute rheumatic fever and complications such as peritonsillar or retropharyngeal abscess, deep tissue cellulitis, toxic shock–like syndrome, bacteremia, arthralgia, and acute glomerulonephritis. Initiation of appropriate therapy within the first 9 days after development of the pharyngitis will prevent rheumatic fever. Patients are considered noncontagious 24 hours after initiation of appropriate antibiotic therapy.

Group A streptococci are uniformly sensitive to penicillin. Although oral penicillin remains the therapy of choice, amoxicillin and cephalosporin drugs such as cephalexin, cefadroxil, cefuroxime, and cefprozil also are effective. Erythromycin is used in patients who have a known sensitivity to penicillin. Newer macrolides (e.g., clarithromycin, azithromycin) have similar effectiveness but cause less gastrointestinal distress when compared with erythromycin.

No single regimen eliminates pharyngeal pathogenic streptococci in 100% of treated patients. Posttherapeutic laboratory testing is recommended in patients with a family history of rheumatic fever, during outbreaks of acute rheumatic fever or streptococcal glomerulonephritis, during outbreaks of streptococcal pharyngitis in semiclosed communities, and when “ping pong” spread is occurring within a family. In these cases, clindamycin or amoxicillin-clavulanic acid often is able to clear the organism in patients who continue to demonstrate positive culture after penicillin therapy.

SCARLET FEVER (SCARLATINA)

Scarlet fever is a systemic infection produced by group A, b-hemolytic streptococci. The disease begins as a streptococcal tonsillitis with pharyngitis in which the organisms elaborate an erythrogenic toxin that attacks the blood vessels and produces the characteristic skin rash. The condition occurs in susceptible patients who do not have antitoxin antibodies. The incubation period ranges from 1 to 7 days, and the significant clinical findings include fever, enanthem, and exanthem.

CLINICAL FEATURES: Scarlet fever is most common in children from the ages of 3 to 12 years. The enanthem of the oral mucosa involves the tonsils, pharynx, soft palate, and tongue (see discussion of streptococcal pharyngotonsillitis in previous section). The tonsils, soft palate, and pharynx become erythematous and edematous, and the tonsillar crypts may be filled with a yellowish exudate. In severe cases, the exudates may become confluent and can resemble diphtheria (see page 186).

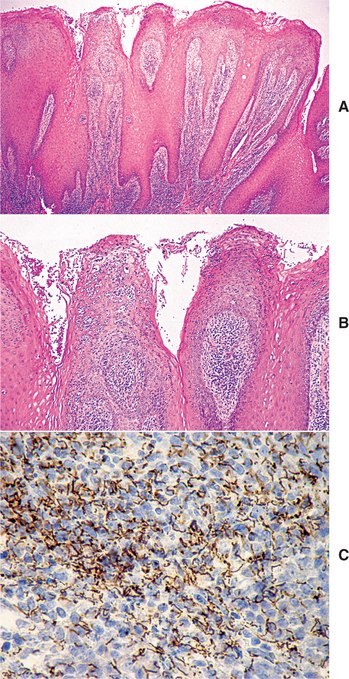

Scattered petechiae may be seen on the soft palate. During the first 2 days, the dorsal surface of the tongue demonstrates a white coating through which only the fungiform papillae can be seen; this has been called white strawberry tongue (Fig. 5-5). By the fourth or fifth day, red strawberry tongue develops when the white coating desquamates to reveal an erythematous dorsal surface with hyperplastic fungiform papillae.

Fig. 5-5 Scarlet fever. Dorsal surface of the tongue exhibiting white coating in association with numerous enlarged and erythematous fungiform papillae (white strawberry tongue).

Classically, in untreated cases, fever develops abruptly around the second day. The patient’s temperature peaks at approximately 103° F and returns to normal within 6 days. The exanthematous rash develops within the first 2 days and becomes widespread within 24 hours. The classic rash of scarlet fever is distinctive and often is described as “a sunburn with goose pimples.” Pinhead punctate areas that are normal in color project through the erythema, giving the skin of the trunk and extremities a sandpaper texture. The rash is more intense in areas of pressure and skin folds. Often, transverse red streaks, known as Pastia’s lines, occur in the skin folds secondary to the capillary fragility in these zones of stress. In contrast, the skin of the face usually is spared or may demonstrate erythematous cheeks with circumoral pallor.

The rash usually clears within 1 week, and then a period of desquamation of the skin occurs. This scaling begins on the face at the end of the first week and spreads to the rest of the skin by the third week, with the extremities being the last affected. The desquamation of the face produces small flakes; the skin of the trunk comes off in thicker, larger flakes. This period of desquamation may last from 3 to 8 weeks.

DIAGNOSIS: A culture of throat secretions may be used to confirm the diagnosis of streptococcal infection, but this has been replaced by several methods of rapid detection of antigens that are specific for group A, b-hemolytic streptococci. Failure to respond to appropriate antibiotics should alert the clinician that the detected streptococci may represent an intercurrent carrier state, and other causes of infection should be investigated.

TREATMENT AND PROGNOSIS: Treatment of scarlet fever and the associated streptococcal pharyngitis is necessary to prevent the possibility of complications, such as peritonsillar or retropharyngeal abscess, sinusitis, or pneumonia. Late complications are rare and include otitis media, acute rheumatic fever, glomerulonephritis, arthralgia, meningitis, and hepatitis. The treatment of choice is oral penicillin, with erythromycin reserved for patients who are allergic to penicillin. Ibuprofen can be used to reduce the fever and relieve the associated discomfort. The fever and symptoms show dramatic improvement within 48 hours after the initiation of treatment. With appropriate therapy, the prognosis is excellent.

TONSILLAR CONCRETIONS AND TONSILLOLITHIASIS

Anatomically, the pharyngeal tonsils demonstrate numerous deep, twisted, and epithelial-lined invaginations. These tonsillar crypts function to increase the surface area for interaction between the immune cells within the lymphoid tissue and the oral environment. These convoluted crypts commonly are filled with desquamated keratin and foreign material and secondarily become colonized with bacteria, usually Actinomyces spp. The contents of the invaginations often become compacted and form a mass of foul-smelling material known as a tonsillar concretion. Occasionally, the condensed necrotic debris and bacteria undergo dystrophic calcification and form a tonsillolith. Recurrent tonsillar inflammation may promote the development of these tonsillar concretions.

CLINICAL AND RADIOGRAPHIC FEATURES: Although tonsillar concretions and tonsilloliths are not uncommon, published reports are rare, often documenting unusually large examples. The affected tonsil will demonstrate one or more enlarged crypts filled with yellow debris that varies in consistency from soft to friable to fully calcified. In contrast to acute tonsillitis, the surrounding tonsillar tissue is not acutely painful, dramatically inflamed, or significantly edematous. Tonsilloliths can develop over a wide age range, from childhood to old age, with a mean patient age in the early 40s. Men are affected twice as frequently as women. These calcifications vary from small clinically insignificant lesions to massive calcifications more than 14 cm in length. Tonsilloliths may be single or multiple, and bilateral cases have been reported.

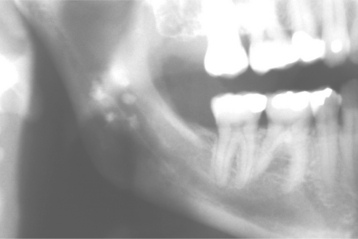

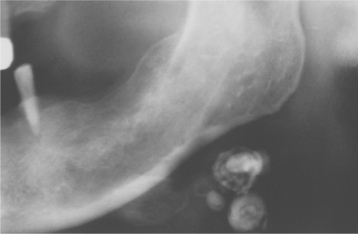

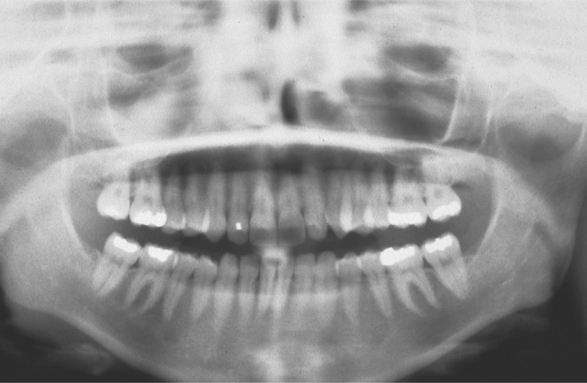

Many tonsillar concretions and tonsilloliths, especially the smaller examples, are asymptomatic. However, these calcifications can promote recurrent tonsillar infections and may lead to pain, abscess formation, ulceration, dysphagia, chronic sore throat, irritable cough, otalgia, or halitosis. Occasionally, patients will report a dull ache or a sensation of a foreign object in the throat that is relieved on removal of the tonsillar plug. In patients with large stones, clinical examination often reveals a hard, yellow submucosal mass of the affected tonsil. In older adult patients, large tonsilloliths can be aspirated and produce significant secondary pulmonary complications. Most frequently, tonsilloliths are discovered on panoramic radiographs as radiopaque objects superimposed on the midportion of the mandibular ramus (Fig. 5-6). On occasion, calcifications initially thought to be bilateral are proven to be unilateral with a panoramic ghost image present on the contralateral side.

DIAGNOSIS: A strong presumptive diagnosis can be made through a combination of the clinical and radiographic features. After detection on a panoramic radiograph, if further diagnostic confirmation of tonsilloliths is deemed necessary, then their presence can be confirmed with computed tomography (CT), magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), or the demonstration of the calculi on removal of the affected tonsil.

TREATMENT AND PROGNOSIS: Tonsilloliths discovered incidentally during evaluation of a panoramic radiograph often are not treated unless associated with significant tonsillar hyperplasia or clinical symptoms. Affected individuals occasionally try to remove tonsillar concretions with instruments such as straws, toothpicks, and dental instruments. Such therapy has the potential to damage the surrounding tonsillar tissue and should be discouraged. Patients should be educated to attempt removal by gargling warm salt water or using pulsating jets of water.

Superficial calculi can be enucleated or curetted; deeper tonsilloliths require local excision. Redevelopment of removed concretions is common. One group successfully used laser cryptolysis to reduce the extent of the tonsillar invaginations and stop the redevelopment of the concretions. If evidence of associated chronic tonsillitis is seen, then tonsillectomy provides definitive therapy.

DIPHTHERIA

Diphtheria is a life-threatening infection produced by Corynebacterium diphtheriae. The disease was first described in 1826, and C. diphtheriae (also termed Klebs-LÖffler bacillus) was discovered initially by Klebs in 1883 and isolated in pure culture by LÖffler in 1884. Humans are the sole reservoir, and the infection is acquired through contact with an infected person or carrier. The bacterium produces a lethal exotoxin that causes tissue necrosis, thereby providing nutrients for further growth and leading to peripheral spread. However, an effective antitoxin has been available since 1913, and immunization has been widespread in North America since 1922.

In the first edition of this textbook, it was stated that diphtheria was included mainly for historical interest because the world was on the threshold of virtual eradication of this infection in developed countries. However, a relatively recent epidemic in Russia reveals how rapidly such advances can be reversed in the absence of an effective immunization program. The epidemic began in Moscow and spread to involve all of the newly independent states of the former Soviet Union. During this outbreak, more than 150,000 cases were reported with approximately 4500 deaths. This one epidemic represented more than 90% of all cases reported between 1990 and 1995. The process was finally controlled by administration of vaccine to all children, adolescents, and adults (regardless of immunization histories).

In addition to this epidemic, infections may occur in people who are immunosuppressed or who have failed to receive booster injections as required. Isolated outbreaks still are reported in the urban poor and Native American populations of North America. Occasional reports from industrialized nations continue to document individuals who have returned home after contracting the infection while visiting a developing country.

CLINICAL FEATURES: The signs and symptoms of diphtheria arise 1 to 5 days after exposure to the organism. The initial systemic symptoms, which include low-grade fever, headache, malaise, anorexia, sore throat, and vomiting, arise gradually and may be mild. Although skin wounds may be involved, the infection predominantly affects mucosal surfaces and may produce exudates of the nasal, tonsillar, pharyngeal, laryngotracheal, conjunctival, or genital areas. Involvement of the nasal cavity is often accompanied with prolonged mucoid or hemorrhagic discharge. The oropharyngeal exudate begins on one or both tonsils as a patchy, yellow-white, thin film that thickens to form an adherent gray covering. With time, the membrane may develop patches of green or black necrosis. The superficial epithelium is an integral portion of this exudate, and attempts at removal are difficult and may result in bleeding. The covering may continue to involve the entire soft palate, uvula, larynx, or trachea, resulting in stridor and respiratory difficulties. Palatal perforation has rarely been reported.

During the Russian epidemic, patients with lesions isolated to the oral cavity were documented. In these patients, scattered areas of necrosis were noted on the buccal mucosa, upper and lower lips, hard and soft palate, or tongue. Such localization is rare and makes diagnosis more difficult.

The severity of the infection correlates with the spread of the membrane. Local obstruction of the airway can be lethal. Involvement of the tonsils leads to significant cervical lymphadenopathy, which often is associated with an edematous neck enlargement known as bull neck. Toxin-related paralysis may affect oculomotor, facial, pharyngeal, diaphragmatic, and intercostal muscles. The soft palatal paralysis can lead to nasal regurgitation during swallowing. Oral or nasal involvement has been reported to spread to the adjacent skin of the face and lips.

Cutaneous diphtheria can occur anywhere on the body and is characterized by chronic skin ulcers that frequently are associated with infected insect bites and also may harbor other pathogens such as Staphylococcus aureus or Streptococcus pyogenes. These skin lesions can arise even in vaccinated patients and typically are not associated with systemic toxic manifestations. When contracted by travelers from developed nations, the diagnosis often is delayed because of the nonspecific clinical presentation and a low index of suspicion. The cutaneous lesions represent an important reservoir of infection and can lead to more typical and lethal diphtheria in unprotected contacts.

Although bacteremia is rare, circulating toxin can result in systemic complications. Myocarditis and neurologic difficulties are seen most frequently and are usually discovered in patients with severe nasopharyngeal diphtheria. Myocarditis may exhibit as progressive weakness and dyspnea or lead to acute congestive heart failure. Neuropathy is not uncommon in patients with severe diphtheria, and palatal paralysis is the most commonly seen manifestation. A peripheral polyneuritis resembling Guillain-Barré syndrome also may occur.

DIAGNOSIS: Although the clinical presentation can be distinctive in severe cases, laboratory confirmation should be sought in all instances. The specimen for culture should be obtained from underneath the diphtheric membrane, if possible, or from the surface of the membrane. Culture material also should be obtained from the nasal mucosa. Diphtheria also must be kept in mind for any patient who has traveled to a disease-endemic area and has chronic skin ulcerations. In these cases, wound swab specimens should be examined for C. diphtheriae.

TREATMENT AND PROGNOSIS: Treatment of the patient with diphtheria should be initiated at the time of the clinical diagnosis and should not be delayed until the results of the culture are received. Antitoxin should be administered in combination with antibiotics to prevent further toxin production, to stop the local infection, and to prevent transmission. Erythromycin, procaine penicillin, or intravenous (IV) penicillin may be used. Most patients are no longer infectious after 4 days of antibiotic therapy, but some may retain vital organisms. The patient is not considered to be cured until three consecutive negative culture specimens are obtained.

Before the development of the antitoxin, the mortality rate approached 50%, usually from cardiac or neurologic complications. The current mortality rate is less than 5%, but the outcome is unpredictable. Development of myocarditis is an important predictor of mortality.

Deaths still occur in the United States because of delays in therapy secondary to lack of suspicion. With worldwide travel and visitors from across the globe, prevention is paramount. Even in those vaccinated as children, it must be remembered that a booster inoculation is required every 10 years.

SYPHILIS (LUES)

Syphilis is a worldwide chronic infection produced by Treponema pallidum. The organism is extremely vulnerable to drying; therefore, the primary modes of transmission are sexual contact or from mother to fetus. Although the risk of infection from blood transfusion is negligible because of serologic testing of donors, transmission through exposure to infected blood is theoretically possible because the organism may survive up to 5 days in refrigerated blood. Humans are the only proven natural host for syphilis.

After the advent of penicillin therapy in the 1940s, the incidence of syphilis slowly decreased for many years but often demonstrated peaks and troughs in approximately 10-year cycles. In 2000 the United States had the fewest reported cases of primary and secondary syphilis since reporting began in 1941. From 2001 to 2004, the rate increased primarily as a result of increases among men who have sex with men (MSM). In 2004, 84% of reported cases occurred in men, and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) estimates 64% of the total number was among MSM. In women, the prevalence decreased each year from 2000 to 2003 but leveled off and remained stable in 2004. In 2004, men were affected 5.9 times more frequently than women.

Although the data vary from year to year, a significant and prolonged increased prevalence has been seen in blacks, with the rate in 2004 being 5.6 times greater than that among whites. Most of the recent increases have been found in black men. Because of the recent trends in the surveillance data, current national health policy is stressing enhanced prevention measures directed toward blacks and MSM.

Oral sex is thought to have played an increasingly important contribution to the recent surge in a number of sexually transmitted diseases in MSM. Because the risk of HIV transmission through oral sex is lower than the rate associated with vaginal or anal sex, many falsely believed that unprotected oral sex was a safe or no-risk sexual practice and represented a good replacement for other higher-risk behaviors.

In patients with syphilis, the infection undergoes a characteristic evolution that classically proceeds through three stages. A syphilitic patient is highly infectious only during the first two stages, but pregnant women also may transmit the infection to the fetus during the latent stage. Maternal transmission during the first two stages of infection almost always results in miscarriage, stillbirth, or an infant with congenital malformations. The longer the mother has had the infection, the less the chance of fetal infection. Infection of the fetus may occur at any time during pregnancy, but the stigmata do not begin to develop until after the fourth month of gestation. The clinical changes secondary to the fetal infection are known as congenital syphilis. Between 1997 and 2002, a 63% reduction in the prevalence of congenital syphilis was noted, a figure that correlates closely with decreases in primary and secondary syphilis rates among women during that time. Continued national interventions attempt to ensure that all pregnant women receive prenatal care, including screening for syphilis early in the pregnancy.

Oral syphilitic lesions are uncommon but may occur in any stage. Many of the changes are secondary to obliterative endarteritis, which occurs in areas of infection.

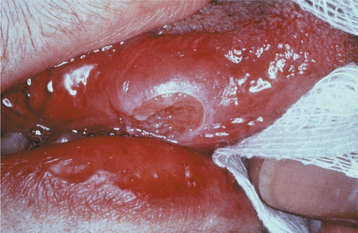

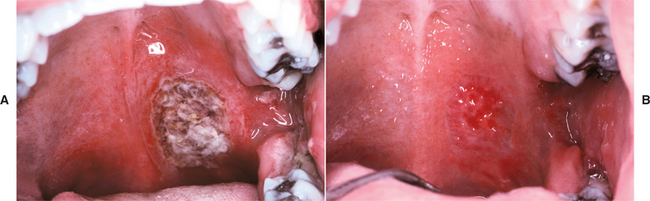

PRIMARY SYPHILIS: Primary syphilis is characterized by the chancre that develops at the site of inoculation, becoming clinically evident 3 to 90 days after the initial exposure. The majority of chancres are solitary, although multiple lesions may be seen occasionally. The external genitalia and anus are the most common sites, and the affected area begins as a papular lesion, which develops a central ulceration. Less than 2% of chancres occur in other locations, but the oral cavity is the most common extragenital site. Oral lesions are seen most commonly on the lip, but other sites include the tongue, palate, gingiva, and tonsils (Fig. 5-7). The upper lip is affected more frequently in males, whereas lower lip involvement is predominant in females. Some believe this selective labial distribution may reflect the surfaces most actively involved during fellatio and cunnilingus. The oral lesion appears as a painless, clean-based ulceration or, rarely, as a vascular proliferation resembling a pyogenic granuloma. Regional lymphadenopathy, which may be bilateral, is seen in most patients. At this time the organism is spreading systemically through the lymphatic channels, setting the stage for future progression. If untreated, then the initial lesion heals within 3 to 8 weeks.

SECONDARY SYPHILIS: The next stage is known as secondary (disseminated) syphilis and is discovered clinically 4 to 10 weeks after the initial infection. The lesions of secondary syphilis may arise before the primary lesion has resolved com pletely. During secondary syphilis, systemic symptoms often arise. The most common are painless lymphadenopathy, sore throat, malaise, headache, weight loss, fever, and musculoskeletal pain. A consistent sign is a diffuse, painless, maculopapular cutaneous rash, which is widespread and can even affect the palmar and plantar areas (Fig. 5-8). The rash also may involve the oral cavity and appear as red, maculopapular areas. Although the skin rash may result in areas of scarring and hyperpigmentation or hypopigmentation, it heals without scarring in the vast majority of patients.

Fig. 5-8 Secondary syphilis. Erythematous rash of secondary syphilis affecting the palms of the hands. (Courtesy of Dr. John Maize.)

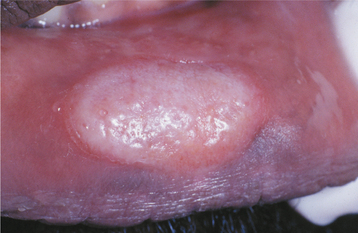

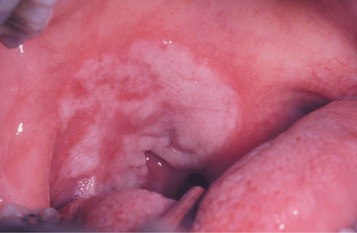

In addition, roughly 30% of patients have focal areas of intense exocytosis and spongiosis of the oral mucosa, leading to zones of sensitive whitish mucosa known as mucous patches (Figs. 5-9 and 5-10). Occasionally, several adjacent patches can fuse and form a serpentine or snailtrack pattern. Subsequently, superficial epithelial necrosis may occur, leading to sloughing and exposure of the underlying raw connective tissue. These may appear on any mucosal surface but are found commonly on the tongue, lip, buccal mucosa, and palate. Elevated mucous patches also may be centered over the crease of the oral commissure and have been termed split papules. Occasionally, papillary lesions that may resemble viral papillomas arise during this time and are known as condylomata lata. Although these lesions typically occur in the genital or anal regions, rare oral examples occur (Fig. 5-11). In contrast to the isolated chancre noted in the primary stage, multiple lesions are typical of secondary syphilis. Spontaneous resolution usually occurs within 3 to 12 weeks; however, relapses may occur during the next year.

Fig. 5-9 Mucous patch of secondary syphilis. Circumscribed white plaque on the lower labial mucosa. (Courtesy of Dr. Pete Edmonds.)

Fig. 5-10 Mucous patch of secondary syphilis. Irregular thickened white plaque of the right soft palate.

Fig. 5-11 Condyloma lata. Multiple indurated and slightly papillary nodules on the dorsal tongue. (Courtesy of Dr. Karen Novak.)

On occasion, especially in the presence of a compromised immune system, secondary syphilis can exhibit an explosive and widespread form known as lues maligna. This form has prodromal symptoms of fever, headache, and myalgia, followed by the formation of necrotic ulcerations, which commonly involve the face and scalp. Oral lesions are present in more than 30% of affected patients. Malaise, pain, and arthralgia are seen occasionally. Several cases of lues maligna have been reported in patients with acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS) (see page 264), and this possibility should be kept in mind whenever HIV-infected patients have atypical ulcerations of the skin or oral mucosa.

TERTIARY SYPHILIS: After the second stage, patients enter a period in which they are free of lesions and symptoms, known as latent syphilis. This period of latency may last from 1 to 30 years; then (in approximately 30% of patients) the third stage, which is known as tertiary syphilis, develops. The third stage of syphilis includes the most serious of all complications. The vascular system can be affected significantly through the effects of the earlier arteritis. Aneurysm of the ascending aorta, left ventricular hypertrophy, aortic regurgitation, and congestive heart failure may occur. Involvement of the central nervous system (CNS) may result in tabes dorsalis, general paralysis, psychosis, dementia, paresis, and death. Ocular lesions such as iritis, choroidoretinitis, and Argyll Robertson pupil (fails to react to light but responds to accommodation) may occur. Less significant, but more characteristic, are scattered foci of granulomatous inflammation, which may affect the skin, mucosa, soft tissue, bones, and internal organs. This active site of granulomatous inflammation, known as a gumma, appears as an indurated, nodular, or ulcerated lesion that may produce extensive tissue destruction. Intraoral lesions usually affect the palate or tongue. When the palate is involved, the ulceration frequently perforates through to the nasal cavity (Fig. 5-12). The tongue may be involved diffusely with gummata and appear large, lobulated, and irregularly shaped. This lobulated pattern is termed interstitial glossitis and is thought to be the result of contracture of the lingual musculature after healing of gummas. Diffuse atrophy and loss of the dorsal tongue papillae produce a condition called luetic glossitis (Fig. 5-13). In the past, this form of atrophic glossitis was thought to be precancerous, but several more recent publications dispute this concept.

CONGENITAL SYPHILIS: In 1858, Sir Jonathan Hutchinson described the changes found in congenital syphilis and defined the following three pathognomonic diagnostic features, known as Hutchinson’s triad:

Like many diagnostic triads, few patients exhibit all three features.

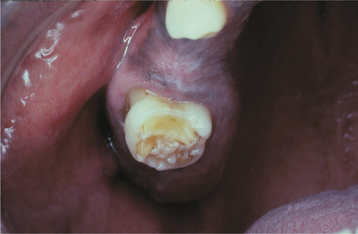

Infants infected with syphilis can display signs within 2 to 3 weeks of birth. These early findings include growth retardation, fever, jaundice, anemia, hepatosplenomegaly, rhinitis, rhagades (circumoral radial skin fissures), and desquamative maculopapular, ulcerative, or vesiculobullous skin eruptions. Untreated infants who survive often develop tertiary syphilis with damage to the bones, teeth, eyes, ears, and brain. It is these findings that were described well by Hutchinson. The infection alters the formation of both the anterior teeth (Hutchinson’s incisors) and the posterior dentition (mulberry molars, Fournier’s molars, Moon’s molars). Hutchinson’s incisors exhibit their greatest mesiodistal width in the middle third of the crown. The incisal third tapers to the incisal edge, and the resulting tooth resembles a straightedge screwdriver (Fig. 5-14). The incisal edge often exhibits a central hypoplastic notch. Mulberry molars taper toward the occlusal surface with a constricted grinding surface. The occlusal anatomy is abnormal, with numerous disorganized globular projections that resemble the surface of a mulberry (Fig. 5-15).

Fig. 5-14 Hutchinson’s incisors of congenital syphilis. Dentition exhibiting crowns tapering toward the incisal edges. (From Halstead CL, Blozis GG, Drinnan AJ et al: Physical evaluation of the dental patient, St Louis, 1982, Mosby.)

Fig. 5-15 Mulberry molar of congenital syphilis. Maxillary molar demonstrating occlusal surface with numerous globular projections.

Interstitial keratitis of the eyes is not present at birth but usually develops between the ages of 5 and 25 years. The affected eye has an opacified corneal surface, with a resultant loss of vision. In addition to Hutchinson’s triad, a number of other alterations such as saddle-nose deformity, high-arched palate, frontal bossing, hydrocephalus, mental retardation, gummas, and neurosyphilis may be seen. Table 5-1 delineates the prevalence rates of the stigmata of congenital syphilis in a cohort of affected patients.

Table 5-1

Stigmata of Congenital Syphilis

| Stigmata of Congenital Syphilisa | Number of Patients | % Affected |

| Frontal bossing | 235 | 86.7 |

| Short maxilla | 227 | 83.8 |

| High-arched palate | 207 | 76.4 |

| Saddle nose | 199 | 73.4 |

| Mulberry molars | 176 | 64.9 |

| Hutchinson’s incisors | 171 | 63.1 |

| Higoumenaki’s signb | 107 | 39.4 |

| Relative prognathism of mandible | 70 | 25.8 |

| Interstitial keratitis | 24 | 8.8 |

| Rhagadesc | 19 | 7.0 |

| Saber shind | 11 | 4.1 |

| Eighth nerve deafness | 9 | 3.3 |

| Scaphoid scapulaee | 2 | 0.7 |

| Clutton’s jointf | 1 | 0.3 |

bEnlargement of clavicle adjacent to the sternum.

cPremature perioral fissuring.

dAnterior bowing of tibia as a result of periostitis.

eConcavity of vertebral border of the scapulae.

fPainless synovitis and enlargement of joints, usually the knee.

Modified from Fiumara NJ, Lessel S: Manifestations of late congenital syphilis: an analysis of 271 patients, Arch Dermatol 102:78, 1970.

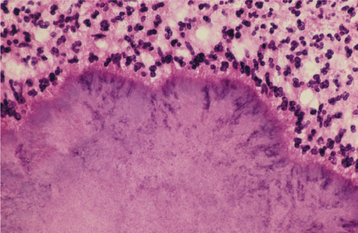

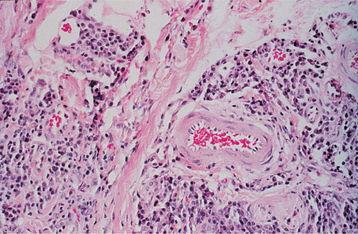

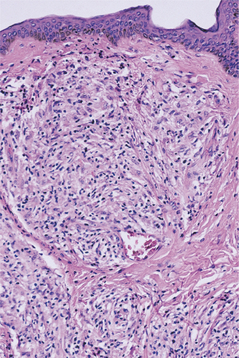

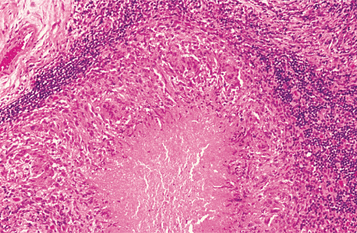

HISTOPATHOLOGIC FEATURES: The histopathologic picture of the oral lesions in the syphilitic patient is not specific. During the first two stages, the pattern is similar. The surface epithelium is ulcerated in primary lesions and may be ulcerated or hyperplastic in the secondary stage. The underlying lamina propria may demonstrate an increase in the number of vascular channels, and an intense chronic inflammatory reaction is present. The infiltrate is composed predominantly of lymphocytes and plasma cells and often demonstrates a perivascular pattern (Fig. 5-16). Although the presence of plasma cells within the infiltrate may suggest the diagnosis of syphilis on the skin, their presence in areas of oral ulceration is commonplace and therefore not necessarily of diagnostic significance. In secondary syphilis, ulceration may not be present and the surface epithelium often demonstrates hyperplasia with significant spongiosis and exocytosis (Fig. 5-17). When noted in combination with an underlying dense, deep, and perivascular plasmacytic infiltrate, the index of suspicion often raises to a level that supports a search for the organism. The use of special silver impregnation techniques, such as Warthin-Starry or Steiner stains, or immunoperoxidase reactions directed against the organism often show scattered corkscrewlike spirochetal organisms that frequently are found most easily within the surface epithelium (see Fig. 5-17, C). The organism also can be detected in tissue through direct fluorescent antibody testing.

Fig. 5-16 Primary syphilis. A chronic perivascular inflammatory infiltrate of plasma cells and lymphocytes. (Courtesy of Dr. John Metcalf.)

Fig. 5-17 Secondary syphilis, condyloma lata. A, Low-power photomicrograph of biopsy from patient in Fig. 5-11, which shows papillary epithelial hyperplasia and a heavy plasmacytic infiltrate in the connective tissue. B, High-power view showing intense exocytosis of neutrophils into the epithelium. C, Immunoperoxidase reaction for Treponema pallidum demonstrating numerous spirochetes in the epithelium.

Oral tertiary lesions typically exhibit surface ulceration, with peripheral pseudoepitheliomatous hyperplasia. The underlying inflammatory infiltrate usually demonstrates foci of granulomatous inflammation with well-circumscribed collections of histiocytes and multinucleated giant cells. Even with special stains, the organisms are hard to demonstrate in the third stage; researchers believe the inflammatory response is an immune reaction, rather than a direct response to T. pallidum.

DIAGNOSIS: The diagnosis of syphilis can be confirmed by demonstrating the spiral organism by dark-field examination of a smear of the exudate of an active lesion. False-positive results are possible in the oral cavity because of morphologically similar oral inhabitants, such as Treponema microdentium, T. macrodentium, and T. mucosum. Demonstration of the organism on a smear or in biopsy material should be confirmed through the use of specific immunofluorescent antibody or serologic tests.

Several nonspecific and not highly sensitive serologic screening tests for syphilis are available. These include the Venereal Disease Research Laboratory (VDRL) and the rapid plasma reagin (RPR). After the first 3 weeks of infection, the screening tests are positive strongly throughout the first two stages. After the development of latency, the positivity generally subsides with time. As part of appropriate prenatal care, all pregnant women should receive one of the nonspecific screening tests.

Specific and highly sensitive serologic tests for syphilis also are available. These include the fluorescent treponemal antibody absorption (FTA-ABS), T. pallidum hemagglutination assay (TPHA), T. pallidum particle agglutination assay (TPPA), and microhemagglutination assay for antibody to T. pallidum (MHA-TP). These test results become positive at the time of the development of the first lesion of primary syphilis and remain positive for life. This lifelong persistence of positivity limits their usefulness in the diagnosis of a second incidence of infection. Therefore, in cases of possible reinfection, the organisms should be demonstrated within the tissue or exudates.

TREATMENT AND PROGNOSIS: The treatment for syphilis necessitates an individual evaluation and a customized therapeutic approach. The treatment of choice is penicillin. The dose and administration schedules vary according to the stage, neurologic involvement, and immune status. For primary, secondary, or early latent syphilis, a single dose of parenteral long-acting benzathine penicillin G is given. For late latent or tertiary syphilis, intramuscular penicillin is administered weekly for 3 weeks. For the patient with a true penicillin allergy, doxycycline is second-line therapy, although tetracycline, erythromycin, and ceftriaxone also have demonstrated antitreponemal activity.

In 50% of patients with primary syphilis and 90% of those with secondary syphilis, an unusual initial response to therapy occurs known as the Jarisch-Herxheimer reaction. This process occurs secondary to release of endotoxin when antibiotics kill large numbers of organisms. Clinical evidence of this reaction occurs about 8 hours after the first injection of penicillin and most commonly includes mild fever, malaise, headache, and an exacerbation of skin or mucosal lesions. These signs and symptoms are very temporary and rapidly fade.

Treatment failures occur in approximately 5% of patients. When treating primary, secondary, or early latent syphilis, some experts recommend serologic follow-up at 6, 12, 18, and 24 months. Pregnant women treated for syphilis should be retested at the twenty-eighth week and again at delivery. Infants born to seropositive mothers are treated with IV penicillin.

Even in patients who obtain a clinical and serologic “cure” with penicillin, it must be remembered that T. pallidum can escape the lethal effects of the antibiotic when the organism is located within the confines of lymph nodes or the central nervous system. Therefore, antibiotic therapy may not always result in a total cure in patients with neurologic involvement but may arrest only the clinical presentations of the infection. Patients with immunosuppression, such as those with AIDS, may not respond appropriately to standard antibiotic regimens, and numerous reports have documented a continuation to neurosyphilis despite seemingly appropriate single-dose therapy.

In the review of the recent increase of syphilis in MSM, high rates of coinfection with HIV have been documented. Although many factors are involved, the mucosal damage created by the spirochetes probably provides greater access for HIV infection. Patients diagnosed with syphilis, especially MSM, also should be tested for HIV.

GONORRHEA

Gonorrhea, a sexually transmitted disease that is produced by Neisseria gonorrhoeae, represents the most common reportable bacterial infection in the United States, with an estimated 700,000 to 800,000 persons infected each year. The disease is epidemic, especially in urban areas; worldwide, millions of people are infected each year. The prevalence of gonorrhea has been declining since a peak in 1975. In 2004, the last year with complete data from the CDC, the rate of infection was the lowest ever reported. Despite this, the rate in the United States remains the highest of any industrialized country, and certain segments of the population, such as those with a low socioeconomic or education level, injecting drug users, prostitutes, homosexual men, and military personnel, remain at high risk. In contrast to many other sexually transmitted diseases, women are affected slightly more frequently than men. Although the rate of infection continues to decrease in all races, African Americans are infected 19 times more often than whites.

CLINICAL FEATURES: The infection is spread through sexual contact, and most lesions occur in the genital areas. Indirect infection is rare because the organism is sensitive to drying and cannot penetrate intact stratified squamous epithelium. The incubation period is typically 2 to 5 days. Affected areas often demonstrate significant purulent discharge, but approximately 10% of men and up to 80% of women who contract gonorrhea are asymptomatic.

In men the most frequent site of infection is the urethra, resulting in purulent discharge and dysuria. Less common primary sites include the anorectal and pharyngeal areas. The cervix is the primary site of involvement in women, and the chief complaints are increased vaginal discharge, intermenstrual bleeding, genital itching, and dysuria. The organism may ascend to involve the uterus and ovarian tubes, leading to the most important female complication of gonorrhea—pelvic inflammatory disease (PID). The symptoms of PID include cramps and abnormal bleeding, which may be severe or mild. The long-term complications of PID include ectopic pregnancies or infertility from tubal obstruction.

Between 0.5% and 3.0% of untreated patients with gonorrhea will have disseminated gonococcal infections from systemic bacteremia. The most common signs of dissemination are myalgia, arthralgia, polyarthritis, and dermatitis. In 75% of patients with disseminated disease, a characteristic skin rash develops. The dermatologic lesions consist of discrete papules and pustules that often exhibit a hemorrhagic component and occur primarily on the extremities. Less common alterations secondary to gonococcal septicemia include fever, endocarditis, pericarditis, meningitis, and oral mucosal lesions of the soft palate and oropharynx, which are similar to aphthous ulcerations.

The prevalence of oral sex appears to be increasing and is thought by many to be the result of the misconception that it represents a low-risk sexual practice and a safe alternative to high-risk activities such as anal or vaginal sex. Most cases of oral gonorrhea appear to be a result of fellatio, although oropharyngeal gonorrhea may be the result of gonococcal septicemia, kissing, or cunnilingus. Therefore, the majority of oropharyngeal gonorrhea cases have been reported in women or homosexual men. Another contributing problem is that pharyngeal gonorrhea often is asymptomatic, making delay in diagnosis and spread more likely. In a recent review of 200 men with urethral gonorrhea, more than 50% admitted to having sex with men (i.e., MSM), and 58% of the MSM group identified oral sex as the sole risk factor for their infection.

The most common site of oropharyngeal involvement is the pharynx along with the tonsils and uvula. Although pharyngeal gonorrhea usually is asymptomatic, a mild-to-moderate sore throat may occur and be accompanied by nonspecific, diffuse oropharyngeal erythema. Involved tonsils typically demonstrate edema and erythema, often with scattered, small punctate pustules. Although most cases of pharyngeal infection resolve spontaneously without adverse sequelae, treatment is important to reduce the potential for spreading the infection.

Rarely, lesions have been reported in the anterior portion of the oral cavity, with areas of infection appearing erythematous, pustular, erosive, or ulcerated. Occasionally, the infection may simulate necrotizing ulcerative gingivitis (NUG), but some clinicians have reported that the typical fetor oris is absent, providing an important clue to the actual cause (Fig. 5-18). Submandibular or cervical lymphadenopathy may be present.

Fig. 5-18 Gonorrhea. Necrosis, purulence, and hemorrhage of the anterior mandibular gingiva. Rights were not granted to include this figure in electronic media. Please refer to the printed book. (From Williams LN: The risks of oral-genital contact: a case report, Gen Dent 50:282-284, 2002.)

During birth, infection of an infant’s eyes can occur from an infected mother who may be asymptomatic. This infection is called gonococcal ophthalmia neonatorum and can rapidly cause perforation of the globe of the eye and blindness. Common signs of infection include significant conjunctivitis and a mucopurulent discharge from the eye.

DIAGNOSIS: In males with a urethral discharge, a Gram stain of the purulent material can be used to demonstrate gram-negative diplococci within the neutrophils; additional testing usually is not indicated. Although Gram stains may be beneficial in women, confirmation of the diagnosis is recommended by culture of endocervical swabs if conditions are adequate to maintain viability of the organisms. A number of other diagnostic studies have been available for many years. Nucleic acid amplification tests (NAATs) amplify and detect N. gonorrhoeae–specific DNA or RNA sequences and are recommended for the diagnosis when conditions are not adequate to maintain the viability of the organisms. In spite of the availability of NAATs, culture remains the preferred diagnostic method for diagnosis of oropharyngeal infections.

TREATMENT AND PROGNOSIS: The primary therapy for gonorrhea has been fluoroquinolones such as ciprofloxacin, levofloxacin, or ofloxacin; however, increasing resistance has been documented in MSM and in infections acquired in Asia, the Pacific islands (including Hawaii), and California. Although oral ciprofloxacin remains first-line therapy for most patients, those at risk for resistant disease should receive intramuscular ceftriaxone. Oral cefixime also is effective but currently is not available in the United States in an appropriate formulation. Patients with gonorrhea are at risk for additional sexually transmitted diseases, most commonly Chlamydia trachomatis for which a C. trachomatis–specific NAAT is available. If chlamydia has not been ruled out, then affected patients also should receive either azithromycin or doxycycline. Rescreening is recommended 1 to 2 months after therapy. The most common cause for treatment failure is reexposure to infected partners, who often are asymptomatic; therefore, the treatment of all recent sexual partners is recommended. Truly resistant infections should be cultured with antimicrobial testing and selection of an appropriate alternate antibiotic. Prophylactic ophthalmic erythromycin, tetracycline, or silver nitrate is applied to the newborn’s eyes to prevent the occurrence of gonococcal ophthalmia neonatorum.

TUBERCULOSIS

Tuberculosis (TB) is a chronic infectious disease caused by Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Worldwide, it is estimated that 2 billion people (one third of the population) are infected; each year 9 million additional individuals become infected. It is estimated that approximately 2 million deaths annually can be attributed to TB. In the United States the disease has been declining since the 1800s, especially since the introduction of effective antimicrobials in the 1940s. The decline ceased abruptly in the early 1980s and appeared to be the result of a combination of several factors. Wars and famine in the developing world, the HIV epidemic, increased immigration from countries with endemic TB, transmission of TB in crowded or unsanitary environments, a decline of the health care infrastructure, and an increased prevalence of multidrug-resistant TB have been implicated in the recent resurgence.

In the 1990s an increased emphasis was placed on TB control and prevention, with a resultant steady decline in the frequency of this serious infection since 1993. In 2006 the directed interventions resulted in the lowest number of recorded cases in the United States since reporting began in 1953, but the average annual decline has slowed since 2000. Immigration and the increased prevalence of multidrug-resistant TB are thought to be largely responsible for the slowing rate of decline of the infection. In 2006 the infection rate in foreign-born persons in the United States was 9.5 times that of persons born in the United States, with more cases reported among Hispanics than any other racial or ethnic population. At the same time, the rate of infection in Hispanics, blacks, and Asians was respectively 7.6, 8.4, and 21.2 higher than in whites. Most infections are the result of direct person-to-person spread through airborne droplets from a patient with active disease.

Nontuberculous mycobacterial disease can occur from a variety of organisms. Before the tuberculin testing of dairy herds, many cases arose from the consumption of milk infected with Mycobacterium bovis. Except for HIV-infected individuals, most other cases of nontuberculous mycobacterial disease appear as localized chronic cervical lymphadenitis in otherwise healthy children. In patients with AIDS (see page 274), M. avium-intracellulare is a common cause of opportunistic infections.

Infection must be distinguished from active disease. Primary tuberculosis occurs in previously unexposed people and almost always involves the lungs. Most infections are the result of direct person-to-person spread through airborne droplets from a patient with active disease. The organism initially elicits a nonspecific, chronic inflammatory reaction. In most individuals, the primary infection results only in a localized, fibrocalcified nodule at the initial site of involvement. However, viable organisms may be present in these nodules and remain dormant for years to life.

Only about 5% to 10% of patients with TB progress from infection to active disease, and an existing state of immunosuppression often is responsible. In rare instances, active TB may ensue directly from the primary infection. However, active disease usually develops later in life from a reactivation of organisms in a previously infected person. This reactivation is typically associated with compromised host defenses and is called secondary tuberculosis. Diffuse dissemination through the vascular system may occur and often produces multiple small foci of infection that grossly and radiographically resemble millet seeds, resulting in the nickname, miliary tuberculosis. Secondary tuberculosis often is associated with immunosuppressive medications, diabetes, old age, poverty, and crowded living conditions. AIDS represents one of the strongest known risk factors for progression from infection to disease. The prevalence of active TB in patients with AIDS is approximately 100 times that documented in the general population.

CLINICAL AND RADIOGRAPHIC FEATURES: Primary TB is usually asymptomatic. Occasionally, fever and pleural effusion may occur.

Classically, the lesions of secondary TB are located in the apex of the lungs but may spread to many different sites by expectorated infected material or through the lymphatic or vascular channels. Typically, patients have a low-grade fever, malaise, anorexia, weight loss, and night sweats. With pulmonary progression, a productive cough develops, often with hemoptysis or chest pain. Progressive TB may lead to a wasting syndrome that, in the past, was termed consumption, because it appeared that the patient’s body was being consumed or destroyed.

Extrapulmonary TB is seen and represents an increasing proportion of the currently diagnosed cases. In patients with AIDS, more than 50% will have extrapulmonary lesions. Any organ system may be involved, including the lymphatic system, skin, skeletal system, CNS, kidneys, and gastrointestinal tract. Involvement of the skin may develop and has been called lupus vulgaris.

Head and neck involvement may occur. The most common extrapulmonary sites in the head and neck are the cervical lymph nodes followed by the larynx and middle ear. Much less common sites include the nasal cavity, nasopharynx, oral cavity, parotid gland, esophagus, and spine.

Oral lesions of TB are uncommon, with most cases appearing as a chronic painless ulcer. Less frequent presentations include nodular, granular, or (rarely) firm leukoplakic areas. The majority of the lesions represent secondary infection from the initial pulmonary foci, occurring most frequently in middle-aged adults. It is unclear whether these lesions develop from hematogenous spread or from exposure to infected sputum. The reported prevalence of clinically evident oral lesions varies from 0.5% to 5.0%. However, one autopsy study revealed a prevalence of close to 20% when the tongues of those infected were examined microscopically. The discovery of pulmonary TB as a result of the investigation of oral lesions occurs but is unusual. Primary oral TB without pulmonary involvement is rare and is more common in children and adolescents.

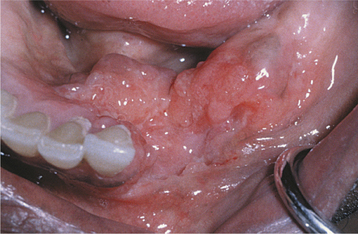

When present, primary oral TB usually involves the gingiva, mucobuccal fold, and areas of inflammation adjacent to teeth or in extraction sites; secondary oral lesions are mostly present on the tongue, palate, and lip (Figs. 5-19 and 5-20). Primary oral lesions are usually associated with enlarged regional lymph nodes. Tuberculous osteomyelitis has been reported in the jaws and appears as ill-defined areas of radiolucency.

Fig. 5-19 Tuberculosis. Chronic mucosal ulceration of the ventral surface of the tongue on the right side. (Reprinted with permission from the American Dental Association.)

Fig. 5-20 Tuberculosis. Area of granularity and ulceration of the lower alveolar ridge and floor of mouth. (Courtesy of Dr. Brian Blocher.)

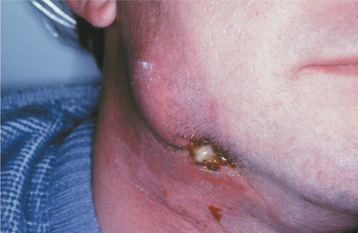

Nontuberculous mycobacterial infections from contaminated milk are currently rare in the industrialized world because of pasteurization of milk, as well as rapid identification and elimination of infected cows. Drinking contaminated milk can result in a form of mycobacterial infection known as scrofula. Scrofula is characterized by enlargement of the oropharyngeal lymphoid tissues and cervical lymph nodes (Fig. 5-21). On occasion, the involved nodes may develop significant caseous necrosis and form numerous sinus tracts through the overlying skin (Fig. 5-22). In addition, areas of nodal involvement may radiographically appear as calcified lymph nodes that may be confused with sialoliths (Fig. 5-23). Pulmonary involvement is unusual in patients with scrofula.

Fig. 5-21 Tuberculosis. Enlargement of numerous cervical lymph nodes. (Courtesy of Dr. George Blozis.)

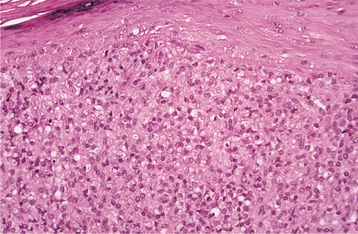

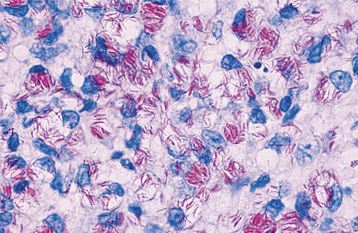

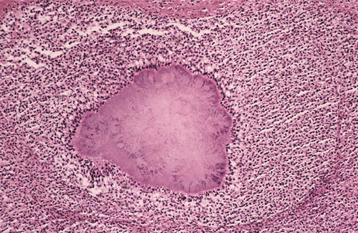

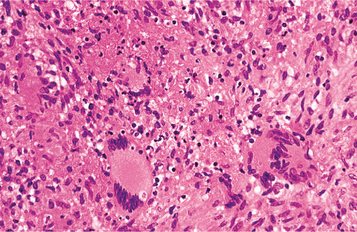

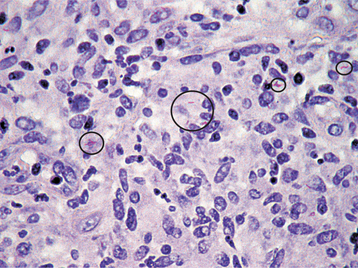

HISTOPATHOLOGIC FEATURES: The cell-mediated hypersensitivity reaction is responsible for the classic histopathologic presentation of TB. Areas of infection demonstrate the formation of granulomas, which are circumscribed collections of epithelioid histiocytes, lymphocytes, and multinucleated giant cells, often with central caseous necrosis (Fig. 5-24). In a person with TB, one of these granulomas is called a tubercle. Special stains, such as the Ziehl-Neelsen or other acid-fast stains, are required to demonstrate the mycobacteria (Fig. 5-25). Because of the relative scarcity of the organisms within tissue, the special stains successfully demonstrate the organism in only 27% to 60% of cases. Therefore, a negative result does not completely rule out the possibility of TB.

Fig. 5-24 Tuberculosis. Histopathologic presentation of the same lesion depicted in Fig. 5-20. Sheets of histiocytes are intermixed with multinucleated giant cells and areas of necrosis.

Fig. 5-25 Tuberculosis. Acid-fast stain of specimen depicted in Fig. 5-24 exhibiting scattered mycobacterial organisms presenting as small red rods.

DIAGNOSIS: Approximately 2 to 4 weeks after initial exposure, a cell-mediated hypersensitivity reaction to tubercular antigens develops. This reaction is the basis for the purified protein derivative (PPD) skin test (i.e., tuberculin skin test), which uses a filtered precipitate of heat-sterilized broth cultures of M. tuberculosis. Positivity runs as high as 80% in developing nations; only 5% to 10% of the population in the United States is positive. A positive tuberculin skin test result indicates exposure to the organism and does not distinguish infection from active disease. A negative tuberculin skin test result does not totally rule out the possibility of TB. False-negative reactions have been documented in older adults; the immunocompromised; patients with sarcoidosis, measles, or Hodgkin’s lymphoma; and when the antigen was placed intradermally. The false-negative rate may be as high as 66% in patients with AIDS.

Special mycobacterial stains and culture of infected sputum or tissue must be used to confirm the diagnosis of active disease. Even if detected with special stains, identification of the organism by culture is appropriate. This identification is important because some forms of nontuberculous mycobacteria have a high level of resistance to traditional antituberculous therapy and frequently require surgical excision. Because 4 to 6 weeks may be required to identify the organism in culture, antituberculous therapy often is initiated before definitive classification. Polymerase chain reaction (PCR) is also used to identify M. tuberculosis DNA and speeds the diagnosis without the need to await culture results.

TREATMENT AND PROGNOSIS: M. tuberculosis can mutate and develop resistance to single-agent medications. To combat this ability, multiagent therapy is the treatment of choice for an active infection, and treatment usually involves two or more active drugs for several months to years. A frequently used protocol consists of an 8-week course of isoniazid, rifampin, and pyrazinamide, followed by a 16-week course of isoniazid and rifampin. Other first-line medications include ethambutol and streptomycin. Relapse rates of approximately 1.5% are seen. With an alteration of doses and the administration schedule, the response to therapy in patients with AIDS has been good, but relapses and progression of infection have been seen.

A different protocol termed chemoprophylaxis is used for patients who have a positive PPD skin test but no signs or symptoms of active disease. Although this situation does not mandate therapy, several investigators have demonstrated the value of therapy, especially in young individuals. Bacillus Calmette-Guérin (BCG) vaccine for TB is available to approximately 85% of the global population, but its use is restricted in the United States because of a controversy related to its effectiveness.

LEPROSY (HANSEN DISEASE)

Leprosy is a chronic infectious disease produced by Mycobacterium leprae. Because of worldwide efforts coordinated by the World Health Organization (WHO), a dramatic decrease in the prevalence of leprosy has been seen over the past 15 years. Since the mid-1980s, the number of estimated cases of active leprosy has dropped from between 10 and 12 million to 1.15 million, with the number of officially registered cases falling 85%. However, leprosy remains a public health problem in many areas of the world. Approximately 82% of all currently reported cases are noted in five countries: Brazil, India, Indonesia, Myanmar, and Nigeria.

The organism has a low infectivity, and exposure rarely results in clinical disease. Small endemic areas of infection are present in Louisiana and Texas, but most patients in the United States have been infected abroad. Many believe that the organism requires a cool host body temperature for survival. Although the exact route of transmission is not known, the high number of organisms in nasal secretions suggests that in some cases the initial site of infection may be the nasal or oropharyngeal mucosa. Although humans are considered the major host, other animals (e.g., armadillo, chimpanzee, mangabey monkey) may be additional possible reservoirs of infection. The nine-banded armadillo is relatively unique because of its low body core temperature, and it is naturally susceptible to the infection. Infected armadillos have been discovered in Louisiana.

For decades, leprologists have believed the bacillus is highly temperature dependent and produces lesions primarily in cooler parts of the body, such as the skin, nasal cavity, and palate. This concept has been questioned because the organism may be seen in significant numbers at sites of core body temperature, such as the liver and spleen. Recently, one investigator mapped common sites of oral involvement and compared this pattern to a map of the local temperature. This comparison demonstrated that the oral lesions tend to occur more frequently in the areas of the mouth with a lower surface temperature. The temperature-dependent theory of leprosy infection remains an area of interest and controversy.

Historically, two main clinical presentations are noted, and these are related to the immune reaction to the organism. The first, called tuberculoid leprosy, develops in patients with a high immune reaction. Typically, the organisms are not found in skin biopsy specimens, skin test results to heat-killed organisms (lepromin) are positive, and the disease is usually localized. The second form, lepromatous leprosy, is seen in patients who demonstrate a reduced cell-mediated immune response. These patients exhibit numerous organisms in the tissue, do not respond to lepromin skin tests, and exhibit diffuse disease. Borderline and less common variations exist. Active disease progresses through stages of invasion, proliferation, ulceration, and resolution with fibrosis. The incubation period is prolonged, with an average of 2 to 5 years for the tuberculoid type and 8 to 12 years for the lepromatous variant.

CLINICAL FEATURES: Currently, leprosy is classified into two separate categories, paucibacillary and multibacillary, with the distinction influencing the recommended form of therapy. Because laboratory services such as skin smears often are not available, patients are increasingly being classified on clinical grounds using the number of lesions (primarily skin) and the number of body areas affected.

Paucibacillary leprosy corresponds closely to the tuberculoid pattern of leprosy and exhibits a small number of well-circumscribed, hypopigmented skin lesions. Nerve involvement usually results in anesthesia of the affected skin, often accompanied by a loss of sweating. Oral lesions are rare in this variant.

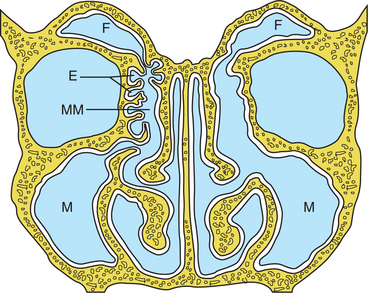

Multibacillary leprosy corresponds well to the lepromatous pattern of leprosy and begins slowly with numerous, ill-defined, hypopigmented macules or papules on the skin that, with time, become thickened (Fig. 5-26). The face is a common site of involvement, and the skin enlargements can lead to a distorted facial appearance (leonine facies). Hair, including the eyebrows and lashes, often is lost (Fig. 5-27). Nerve involvement leads to a loss of sweating and decreased light touch, pain, and temperature sensors. This sensory loss begins in the extremities and spreads to most of the body. Nasal involvement results in nosebleeds, stuffiness, and a loss of the sense of smell. The hard tissue of the floor, septum, and bridge of the nose may be affected. Collapse of the bridge of the nose is considered pathognomonic.

Oral lesions are not rare in multibacillary leprosy, and reports on their prevalence vary from 19% to 60%. In an excellent review by Prabhu and Daftary of 700 patients with leprosy, the prevalence of facial skin involvement was 28%, and oral lesions were noted in 11.5%. The lesions tended to be more frequent during the first 5 years of the disease.

The sites that are cooled by the passage of air appear to be affected most frequently. The locations affected in order of frequency are the hard palate, soft palate, labial maxillary gingiva, tongue, lips, buccal maxillary gingiva, labial mandibular gingiva, and buccal mucosa. Affected soft tissue initially appears as yellowish to red, sessile, firm, enlarging papules that develop ulceration and necrosis, followed by attempted healing by secondary intention. Continuous infection of an area can lead to significant scarring and loss of tissue. Complete loss of the uvula and fixation of the soft palate may occur. The lingual lesions appear primarily in the anterior third and often begin as areas of erosion, which may develop into large nodules. Infection of the lip can result in significant macrocheilia, which can be confused clinically and microscopically with cheilitis granulomatosa (see page 342).

Direct infiltration of the inflammatory process associated with lepromatous leprosy can destroy the bone underlying the areas of soft tissue involvement. Often the infection creates a unique pattern of facial destruction that has been termed facies leprosa and demonstrates a triad of lesions consisting of atrophy of the anterior nasal spine, atrophy of the anterior maxillary alveolar ridge, and endonasal inflammatory changes. Involvement of the anterior maxilla can result in significant bone erosion, with loss of the teeth in this area. Maxillary involvement in children can affect the developing teeth and produce enamel hypoplasia and short tapering roots. Dental pulp infection can lead to internal resorption or pulpal necrosis. Teeth with pulpal involvement may demonstrate a clinically obvious red discoloration of the crown. The cause of the discoloration is unknown but appears to be related to intrapulpal vascular damage secondary to the infection. Granulomatous involvement of the nasal cavity can erode through the palatal tissues and result in perforation.

The facial and trigeminal nerves can be involved with the infectious process. Facial paralysis may be unilateral or bilateral. Sensory deficits may affect any branch of the trigeminal nerve, but the maxillary division is the most commonly affected.

HISTOPATHOLOGIC FEATURES: Biopsy specimens of paucibacillary leprosy typically reveal the tuberculoid pattern that demonstrates granulomatous inflammation with well-formed clusters of epithelioid histiocytes, lymphocytes, and multinucleated giant cells (Fig. 5-28). A paucity of organisms exists; when present, they can be demonstrated only when stained with acid-fast stains, such as the Fite method. Multibacillary leprosy is associated with a lepromatous pattern that demonstrates no well-formed granulomas; the typical finding is sheets of lymphocytes intermixed with vacuolated histiocytes known as lepra cells (Fig. 5-29). Unlike tuberculoid leprosy, an abundance of organisms can be demonstrated with acid-fast stains in the lepromatous variant (Fig. 5-30). It has been reported that the organism can be found with special stains in 100% of lepromatous leprosy cases, 75% of borderline cases, and only 5% of tuberculoid cases.

Fig. 5-28 Paucibacillary (tuberculoid) leprosy. Well-formed granulomatous inflammation demonstrating clusters of lymphocytes and histiocytes.

DIAGNOSIS: The definitive diagnosis is based on the clinical presentation and supported by the demonstration of acid-fast organisms on a smear or in the tissue. The organism cannot be cultivated on artificial media, but M. leprae can be identified by using molecular biologic techniques. No reliable test is available to determine whether a person has been exposed to M. leprae without developing the disease; this creates difficulties in establishing the diagnosis and determining the prevalence of the infection.

TREATMENT AND PROGNOSIS: One of the major reasons for the decreasing prevalence of leprosy is the provision of an uninterrupted supply of free, high-quality medications in calendar blister packs to all patients regardless of the living conditions or remoteness of the location. Paucibacillary leprosy is treated with a 6-month regimen of rifampin and dapsone, whereas patients with multibacillary leprosy receive 24 months of rifampin, dapsone, and clofazimine. Long-term follow up is recommended because of occasional relapses. Patients allergic to rifampin are treated with a 24-month course of clofazimine, ofloxacin, and minocycline.

After resolution of the infection, the therapy must be directed toward reconstruction of the damage, in addition to physiotherapy and education of the patients who must live not only with their physical damage but also with the psychologic stigmata. As medical therapy becomes more successful, the number of long-term survivors of the infection increases. Worldwide, it is estimated that currently about 3 million individuals have leprosy-related impairments and disability.

NOMA (CANCRUM ORIS; OROFACIAL GANGRENE; GANGRENOUS STOMATITIS; NECROTIZING STOMATITIS)

The term noma is derived from the Greek word nomein, meaning to devour. Noma is a rapidly progressive, polymicrobial, opportunistic infection caused by components of the normal oral flora that become pathogenic during periods of compromised immune status. Fusobacterium necrophorum and Prevotella intermedia are thought to be key players in the process and interact with one or more other bacterial organisms, of which the most commonly implicated are Borrelia vincentii, Porphyromonas gingivalis, Tannerella forsynthesis, Treponema denticola, Staphylococcus aureus, and nonhemolytic Streptococcus spp. The reported predisposing factors include the following:

In many cases a recent debilitating illness appears to set the stage for the development of noma. Measles most frequently precedes development of noma; other common but less frequent predisposing illnesses include herpes simplex, varicella, scarlet fever, malaria, tuberculosis, gastroenteritis, and bronchopneumonia. Cases associated with malignancies (e.g., leukemia) are not rare. In many instances the infection begins as necrotizing ulcerative gingivitis (NUG) (see page 157), and several investigators believe that noma is merely an extension of the same process. Because the disease usually is well advanced at the time of initial presentation, descriptions of the initial stages of the disease are sketchy.