Fungal and Protozoal Diseases

CANDIDIASIS

Infection with the yeastlike fungal organism Candida albicans is termed candidiasis or, as the British prefer, candidosis. An older name for this disease is moniliasis; the use of this term should be discouraged because it is derived from the archaic designation Monilia albicans. Other members of the Candida genus, such as C. tropicalis, C. krusei, C. parapsilosis, and C. guilliermondii, may also be found intraorally, but they rarely cause disease.

Like many other pathogenic fungi, C. albicans may exist in two forms—a trait known as dimorphism. The yeast form of the organism is believed to be relatively innocuous, but the hyphal form is usually associated with invasion of host tissue.

Candidiasis is by far the most common oral fungal infection in humans and has a variety of clinical manifestations, making the diagnosis difficult at times. In fact, C. albicans may be a component of the normal oral microflora, with as many as 30% to 50% of people simply carrying the organism in their mouths without clinical evidence of infection. This rate of carriage has been shown to increase with age, and C. albicans can be recovered from the mouths of nearly 60% of dentate patients older than 60 years who have no sign of oral mucosal lesions. At least three general factors may determine whether clinical evidence of infection exists:

In the past, candidiasis was considered to be only an opportunistic infection, affecting individuals who were debilitated by another disease. Certainly, such patients make up a large percentage of those with candidal infections today. However, now clinicians recognize that oral candidiasis may develop in people who are otherwise healthy. As a result of this complex host and organism interaction, candidal infection may range from mild, superficial mucosal involvement seen in most patients to fatal, disseminated disease in severely immunocompromised patients. This chapter focuses on those clinical presentations of candidiasis that affect the oral mucosa.

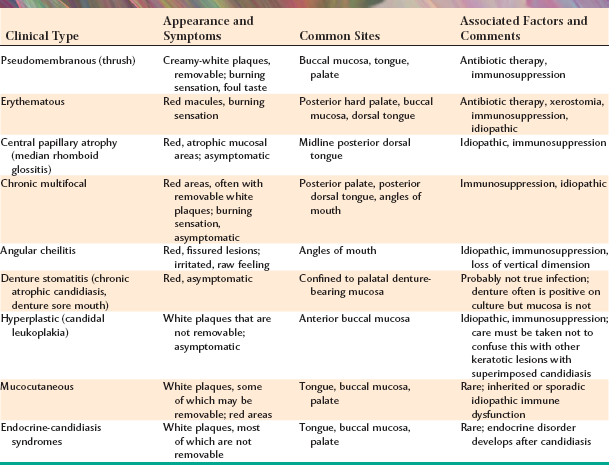

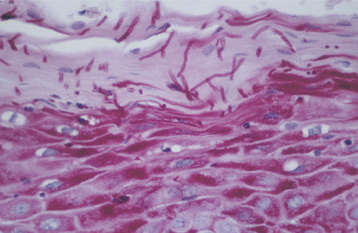

CLINICAL FEATURES: Candidiasis of the oral mucosa may exhibit a variety of clinical patterns, which are summarized in Table 6-1. Many patients will display a single pattern, although some individuals will exhibit more than one clinical form of oral candidiasis.

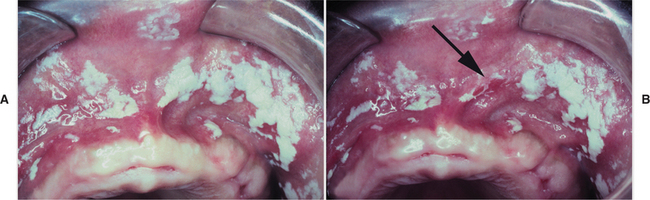

PSEUDOMEMBRANOUS CANDIDIASIS: The best recognized form of candidal infection is pseudomembranous candidiasis. Also known as thrush, pseudomembranous candidiasis is characterized by the presence of adherent white plaques that resemble cottage cheese or curdled milk on the oral mucosa (Figs. 6-1 and 6-2). The white plaques are composed of tangled masses of hyphae, yeasts, desquamated epithe lial cells, and debris. Scraping them with a tongue blade or rubbing them with a dry gauze sponge can remove these plaques. The underlying mucosa may appear normal or erythematous. If bleeding occurs, then the mucosa has probably also been affected by another process, such as lichen planus or cancer chemotherapy.

Fig. 6-2 Pseudomembranous candidiasis. A, Classic “curdled milk” appearance of the oral lesions of pseudomembranous candidiasis. This patient had no apparent risk factors for candidiasis development. B, Removal of one of the pseudomembranous plaques (arrow) reveals a mildly erythematous mucosal surface. (From Allen CM, Blozis GG: Oral mucosal lesions. In Cummings CW, Fredrickson JM, Harker LA et al, editors: Otolaryngology: head and neck surgery, ed 3, St Louis, 1998, Mosby.)

Pseudomembranous candidiasis may be initiated by exposure of the patient to broad-spectrum antibiotics (thus eliminating competing bacteria) or by impairment of the patient’s immune system. The immune dysfunctions seen in leukemic patients (see page 587) or those infected with human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) (see page 264) are often associated with pseudomembranous candidiasis. Infants may also be affected, ostensibly because of their underdeveloped immune systems. Antibiotic exposure is typically responsible for an acute (rapid) expression of the condition; immunologic problems usually produce a chronic (slow-onset, long-standing) form of pseudomembranous candidiasis.

Symptoms, if present at all, are usually relatively mild, consisting of a burning sensation of the oral mucosa or an unpleasant taste in the mouth, variably described as salty or bitter. Sometimes patients complain of “blisters,” when in fact they feel the elevated plaques rather than true vesicles. The plaques are characteristically distributed on the buccal mucosa, palate, and dorsal tongue.

ERYTHEMATOUS CANDIDIASIS: In contrast to the pseudomembranous form, patients with erythematous candidiasis either do not show white flecks, or a white component is not a prominent feature. Erythematous candidiasis is undoubtedly more common than pseudomembranous candidiasis, although it is often overlooked clinically. Several clinical presentations may be seen. Acute atrophic candidiasis or “antibiotic sore mouth,” typically follows a course of broad-spectrum antibiotic therapy. Patients often complain that the mouth feels as if a hot beverage had scalded it. This burning sensation is usually accompanied by a diffuse loss of the filiform papillae of the dorsal tongue, resulting in a reddened, “bald” appearance of the tongue (Fig. 6-3). Burning mouth syndrome (see page 873) frequently manifests with a scalded sensation of the tongue; however, the tongue appears normal in that condition. Patients who suffer from xerostomia for any reason (e.g., pharmacologic, postradiation therapy, SjÖgren syndrome) have an increased prevalence of erythematous candidiasis that is commonly symptomatic as well.

Fig. 6-3 Erythematous candidiasis. The patchy, denuded areas (not the white areas) of the dorsal tongue represent erythematous candidiasis. The patient had received a broad-spectrum antibiotic.

Other forms of erythematous candidiasis are usually asymptomatic and chronic. Included in this category is the condition known as central papillary atrophy of the tongue, or median rhomboid glossitis. In the past, this was thought to be a developmental defect of the tongue, occurring in 0.01% to 1.00% of adults. The lesion was supposed to have resulted from a failure of the embryologic tuberculum impar to be covered by the lateral processes of the tongue. Theoretically, the prevalence of central papillary atrophy in children should be identical to that seen in adults; however, in one study in which 10,000 children were examined, not a single lesion was detected. Other investigators have noted a consistent relationship between the lesion and C. albicans, and similar lesions have been induced experimentally on the dorsal tongues of rats.

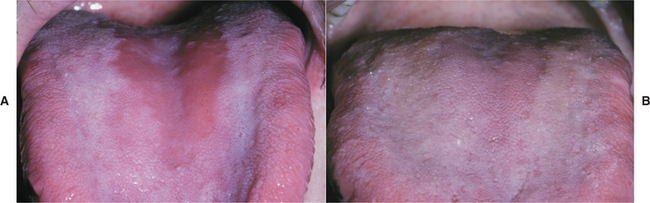

Clinically, central papillary atrophy appears as a well-demarcated erythematous zone that affects the midline, posterior dorsal tongue and often is asymptomatic (Fig. 6-4). The erythema is due in part to the loss of the filiform papillae in this area. The lesion is usually symmetrical, and its surface may range from smooth to lobulated. Often the mucosal alteration resolves with antifungal therapy, although occasionally only partial resolution can be achieved.

Fig. 6-4 Erythematous candidiasis. A, Severe presentation of central papillary atrophy. In this patient the lesion was asymptomatic. B, Marked regeneration of the dorsal tongue papillae occurred 2 weeks after antifungal therapy with fluconazole.

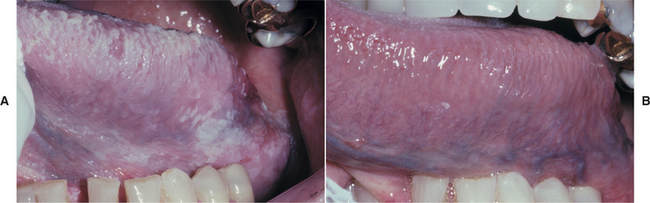

Some patients with central papillary atrophy may also exhibit signs of oral mucosal candidal infection at other sites. This presentation of erythematous candidiasis has been termed chronic multifocal candidiasis. In addition to the dorsal tongue, the sites that show involvement include the junction of the hard and soft palate and the angles of the mouth. The palatal lesion appears as an erythematous area that, when the tongue is at rest, contacts the dorsal tongue lesion, resulting in what is called a “kissing lesion” because of the intimate proximity of the involved areas (Fig. 6-5).

Fig. 6-5 Candidiasis. A, Multifocal oral candidiasis characterized by central papillary atrophy of the tongue and other areas of involvement. B, Same patient showing a “kissing” lesion of oral candidiasis on the hard palate.

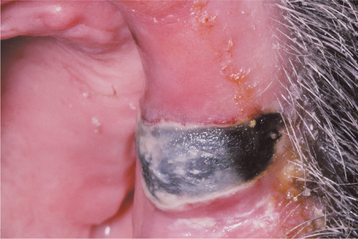

The involvement of the angles of the mouth (angular cheilitis, perléche) is characterized by erythema, fissuring, and scaling (Fig. 6-6). Sometimes this condition is seen as a component of chronic multifocal candidiasis, but it often occurs alone, typically in an older person with reduced vertical dimension of occlusion and accentuated folds at the corners of the mouth. Saliva tends to pool in these areas, keeping them moist and thus favoring a yeast infection. Patients often indicate that the severity of the lesions waxes and wanes. Microbiologic studies have indicated that 20% of these cases are caused by C. albicans alone, 60% are due to a combined infection with C. albicans and Staphylococcus aureus, and 20% are associated with S. aureus alone. Infrequently, the candidal infection more extensively involves the perioral skin, usually secondary to actions that keep the skin moist (e.g., chronic lip licking, thumb sucking), creating a clinical pattern known as cheilocandidiasis (Fig. 6-7). Other causes of exfoliative cheilitis often must be considered in the differential diagnosis (see page 304).

Fig. 6-6 Angular cheilitis. Characteristic lesions appear as fissured, erythematous alterations of the skin at the corners of the mouth.

Fig. 6-7 Cheilocandidiasis. The exfoliative lesions of the vermilion zone and perioral skin are due to superficial candidal infection.

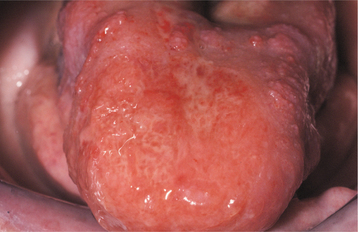

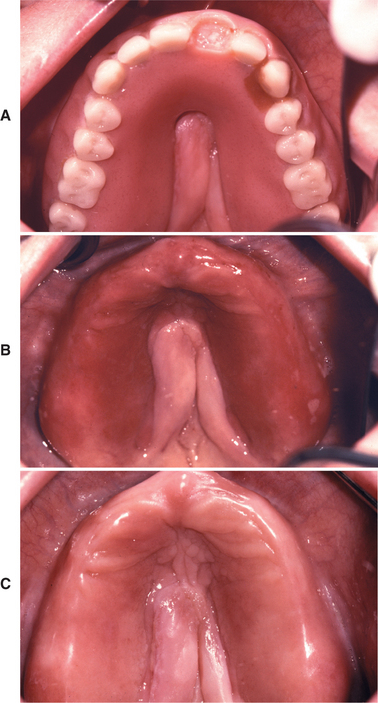

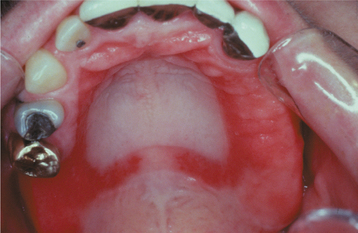

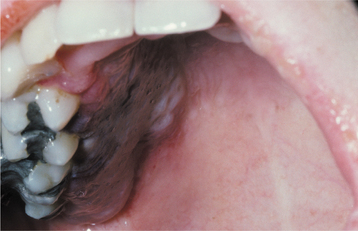

Denture stomatitis should be mentioned because it is often classified as a form of erythematous candidiasis, and some authors may use the term chronic atrophic candidiasis synonymously. This condition is characterized by varying degrees of erythema, sometimes accompanied by petechial hemorrhage, localized to the denture-bearing areas of a maxillary removable dental prosthesis (Figs. 6-8 and 6-9). Although the clinical appearance can be striking, the process is rarely symptomatic. Usually the patient admits to wearing the denture continuously, removing it only periodically to clean it. Whether this represents actual infection by C. albicans or is simply a tissue response by the host to the various microorganisms living beneath the denture remains controversial. The clinician should also rule out the possibility that this reaction could be caused by improper design of the denture (which could cause unusual pressure on the mucosa), allergy to the denture base, or inadequate curing of the denture acrylic.

Fig. 6-8 Denture stomatitis. A, Maxillary denture with incomplete palatal vault associated with midline tissue hyperplasia. B, Mucositis corresponds to the outline of the prosthesis. C, Resolution of mucositis after antifungal therapy and appropriate denture cleansing.

Fig. 6-9 Denture stomatitis. Denture stomatitis, not associated with Candida albicans, confined to the denture-bearing mucosa of a maxillary partial denture framework.

Although C. albicans is often associated with this condition, biopsy specimens of denture stomatitis seldom show candidal hyphae actually penetrating the keratin layer of the host epithelium. Therefore, this lesion does not meet one of the main defining criteria for the diagnosis of infection—host tissue invasion by the organism. Furthermore, if the palatal mucosa and tissue-contacting surface of the denture are swabbed and separately streaked onto a Sabouraud’s agar slant, then the denture typically shows much heavier colonization by yeast (Fig. 6-10).

Fig. 6-10 Denture stomatitis. This Sabouraud’s agar slant has been streaked with swabs obtained from erythematous palatal mucosa (left side of the slant) and the tissue-bearing surface of the denture (right side of the slant). Extensive colonization of the denture is demonstrated, whereas little evidence of yeast associated with the mucosa is noted.

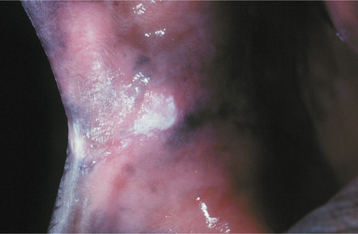

CHRONIC HYPERPLASTIC CANDIDIASIS (CANDIDAL LEUKOPLAKIA): In some patients with oral candidiasis, there may be a white patch that cannot be removed by scraping; in this case the term chronic hyperplastic candidiasis is appropriate. This form of candidiasis is the least common and is also somewhat controversial. Some investigators believe that this condition simply represents candidiasis that is superimposed on a preexisting leukoplakic lesion, a situation that may certainly exist at times. In some instances, however, the candidal organism alone may be capable of inducing a hyperkeratotic lesion. Such lesions are usually located on the anterior buccal mucosa and cannot clinically be distinguished from a routine leukoplakia (Fig. 6-11). Often the leukoplakic lesion associated with candidal infection has a fine intermingling of red and white areas, resulting in a speckled leukoplakia (see page 392). Such lesions may have an increased frequency of epithelial dysplasia histopathologically.

Fig. 6-11 Hyperplastic candidiasis. This lesion of the anterior buccal mucosa clinically resembles a leukoplakia because it is a white plaque that cannot be removed by rubbing. With antifungal therapy, such a lesion should resolve completely.

The diagnosis is confirmed by the presence of candidal hyphae associated with the lesion and by complete resolution of the lesion after antifungal therapy (Fig. 6-12).

Fig. 6-12 Hyperplastic candidiasis. A, These diffuse white plaques clinically appear as leukoplakia, but they actually represent an unusual presentation of hyperplastic candidiasis. B, Treatment with clotrimazole oral troches shows complete resolution of the white lesions within 2 weeks, essentially confirming the diagnosis of hyperplastic candidiasis. If any white mucosal alteration had persisted, a biopsy of that area would have been mandatory.

MUCOCUTANEOUS CANDIDIASIS: Severe oral candidiasis may also be seen as a component of a relatively rare group of immunologic disorders known as mucocutaneous candidiasis. Several distinct immunologic dysfunctions have been identified, and the severity of the candidal infection correlates with the severity of the immunologic defect. Most cases are sporadic, although an autosomal recessive pattern of inheritance has been identified in some families. The immune problem usually becomes evident during the first few years of life, when the patient begins to have candidal infections of the mouth, nails, skin, and other mucosal surfaces. The oral lesions are usually described as thick, white plaques that typically do not rub off (essentially chronic hyperplastic candidiasis), although the other clinical forms of candidiasis may also be seen.

In some patients with mucocutaneous candidiasis, mutations in the autoimmune regulator (AIRE) gene have been documented, with the resultant formation of autoantibodies directed against the person’s own tissues (Fig. 6-13). In most instances the immunologic attack is directed against the endocrine glands; however, the reasons for this tissue specificity are currently unclear. Young patients with mucocutaneous candidiasis should be evaluated periodically because any one of a variety of endocrine abnormalities (i.e., endocrine-candidiasis syndrome, autoimmune polyendocrinopathy-candidiasis-ectodermal dystrophy [APECED] syndrome), as well as iron-deficiency anemia, may develop in addition to the candidiasis. These endocrine disturbances include hypothyroidism, hypoparathyroidism, hypoadrenocorticism (Addison’s disease), and diabetes mellitus. Typically, the endocrine abnormality develops months or even years after the onset of the candidal infection. One recent study has documented increased prevalence of oral and esophageal carcinoma in this condition, with these malignancies affecting approximately 10% of adults with APECED syndrome. This finding represents another justification for periodic reevaluation of these individuals.

Fig. 6-13 Autoimmune polyendocrinopathy-candidiasis-ectodermal dystrophy (APECED) syndrome. A, Erythematous candidiasis diffusely involving the dorsal tongue of a 32-year-old man. B, Same patient showing nail dystrophy. C, Corneal keratopathy is also noted. Patient had a history of the onset of hypoparathyroidism and hypoadrenocorticism, both diagnosed in the second decade of life.

Interestingly, the candidal infection remains relatively superficial rather than disseminating through-out the body. Both the oral lesions and any cutaneous involvement (usually presenting as roughened, foul-smelling cutaneous plaques and nodules) can be controlled with continuous use of relatively safe systemic antifungal drugs.

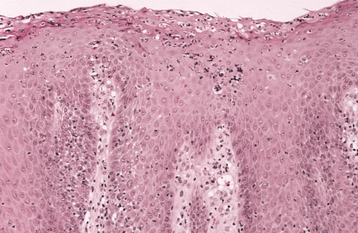

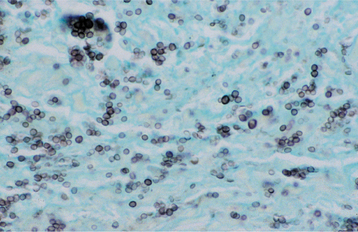

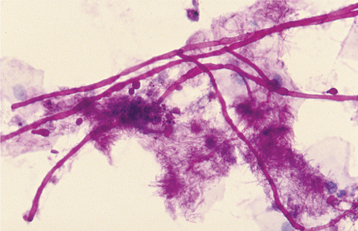

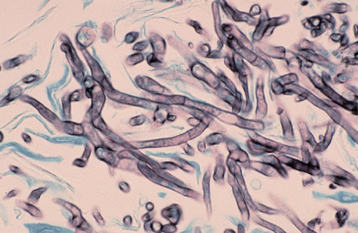

HISTOPATHOLOGIC FEATURES: The candidal organism can be seen microscopically in either an exfoliative cytologic preparation or in tissue sections obtained from a biopsy specimen. On staining with the periodic acid-Schiff (PAS) method, the candidal hyphae and yeasts can be readily identified (Fig. 6-14) . The PAS method stains carbohydrates, contained in abundance by fungal cell walls; the organisms are easily identified by the bright-magenta color imparted by the stain. To make a diagnosis of candidiasis, one must be able to see hyphae or pseudohyphae (which are essentially elongated yeast cells). These hyphae are approximately 2 μm in diameter, vary in their length, and may show branching. Often the hyphae are accompanied by variable numbers of yeasts, squamous epithelial cells, and inflammatory cells.

Fig. 6-14 Candidiasis. This cytologic preparation demonstrates tubular-appearing fungal hyphae and ovoid yeasts of Candida albicans. (PAS stain.)

A 10% to 20% potassium hydroxide (KOH) preparation may also be used to rapidly evaluate specimens for the presence of fungal organisms. With this technique, the KOH lyses the background of epithelial cells, allowing the more resistant yeasts and hyphae to be visualized.

The disadvantages of the KOH preparation include the following:

• Greater difficulty in identifying the fungal organisms, compared with PAS staining

• Inability to assess the nature of the epithelial cell population with respect to other conditions, such as epithelial dysplasia or pemphigus vulgaris

The histopathologic pattern of oral candidiasis may vary slightly, depending on which clinical form of the infection has been submitted for biopsy. The features that are found in common include an increased thickness of parakeratin on the surface of the lesion in conjunction with elongation of the epithelial rete ridges (Fig. 6-15). Typically, a chronic inflammatory cell infiltrate can be seen in the connective tissue immediately subjacent to the infected epithelium, and small collections of neutrophils (microabscesses) are often identified in the parakeratin layer and the superficial spinous cell layer near the organisms (Fig. 6-16). The candidal hyphae are embedded in the parakeratin layer and rarely penetrate into the viable cell layers of the epithelium unless the patient is extremely immunocompromised.

DIAGNOSIS: The diagnosis of candidiasis is usually established by the clinical signs in conjunction with exfoliative cytologic examination. Although a culture can definitively identify the organism as C. albicans, this process may not be practical in most office settings. The cytologic findings should demonstrate the hyphal phase of the organism, and antifungal therapy can then be instituted. If the lesion is clinically suggestive of chronic hyperplastic candidiasis but does not respond to antifungal therapy, then a biopsy should be performed to rule out the possibility of C. albicans superimposed on epithelial dysplasia, squamous cell carcinoma, or lichen planus.

The definitive identification of the organism can be made by means of culture. A specimen for culture is obtained by rubbing a sterile cotton swab over the lesion and then streaking the swab on the surface of a Sabouraud’s agar slant. C. albicans will grow as creamy, smooth-surfaced colonies after 2 to 3 days of incubation at room temperature.

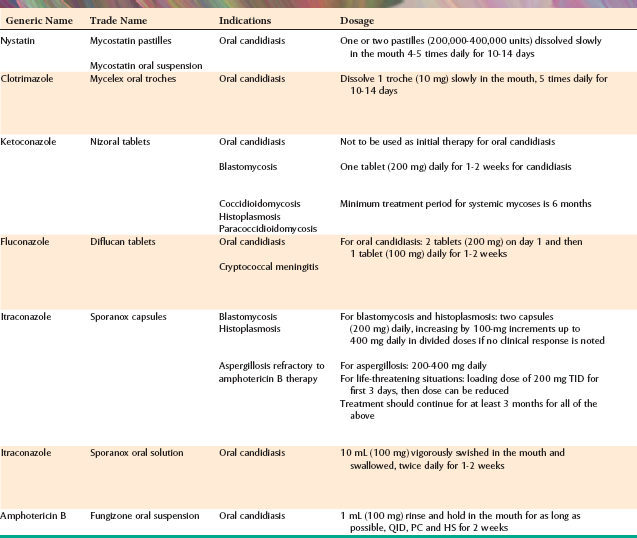

TREATMENT AND PROGNOSIS: Several antifungal medications have been developed for managing oral candidiasis, each with its advantages and disadvantages (Table 6-2).

NYSTATIN: In the 1950s the polyene antibiotic nystatin was the first effective treatment for oral candidiasis. Nystatin is formulated for oral use as a suspension or pastille (lozenge). Many patients report that nystatin has a very bitter taste, which may reduce patient compliance; therefore, the taste has to be disguised with sucrose and flavoring agents. If the candidiasis is due to xerostomia, the sucrose content of the nystatin preparation may contribute to xerostomia-related caries in these patients. The gastrointestinal tract poorly absorbs nystatin and the other polyene antibiotic, amphotericin; therefore, their effectiveness depends on direct contact with the candidal organisms. This necessitates multiple daily doses so that the yeasts are adequately exposed to the drug. Nystatin combined with triamcinolone acetonide cream or ointment can be applied topically and is effective for angular cheilitis that does not have a bacterial component.

AMPHOTERICIN B: For many years in the United States, the use of amphotericin B was restricted to intravenous (IV) treatment of life-threatening systemic fungal infections. This medication subsequently became available as an oral suspension for the management of oral candidiasis. Unfortunately, the interest in this formulation of the drug was scant, and it is no longer marketed in the United States.

IMIDAZOLE AGENTS: The imidazole-derived antifungal agents were developed during the 1970s and represented a major step forward in the management of candidiasis. The two drugs of this group that are used most frequently are clotrimazole and ketoconazole.

CLOTRIMAZOLE: Like nystatin, clotrimazole is not well absorbed and must be administered several times each day. It is formulated as a pleasant-tasting troche (lozenge) and produces few side effects. The efficacy of this agent in treating oral candidiasis can be seen in Fig. 6-12. Clotrimazole cream is also effective treatment for angular cheilitis, because this drug has antibacterial and antifungal properties.

KETOCONAZOLE: Ketoconazole was the first antifungal drug that could be absorbed across the gastrointestinal tract, thereby providing systemic therapy by an oral route of administration. The single daily dose was much easier for patients to use; however, several disadvantages have been noted. Patients must not take antacids or H2-blocking agents because an acidic environment is required for proper absorption. If a patient is to take ketoconazole for more than 2 weeks, then liver function studies are recommended because approximately 1 in 10,000 individuals will experience idiosyncratic liver toxicity from the agent. For this reason, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration has stated that ketoconazole should not be used as initial therapy for routine oral candidiasis. Furthermore, ketoconazole has been implicated in drug interactions with macrolide antibiotics (e.g., erythromycin), the gastrointestinal motility–enhancing agent cisapride, and the antihistamine astemizole, all of which may produce potentially life-threatening cardiac arrhythmias.

TRIAZOLES: The triazoles are the newest group of antifungal drugs. Both fluconazole and itraconazole have been approved for treating candidiasis in the United States.

FLUCONAZOLE: Fluconazole appears to be more effective than ketoconazole; it is well absorbed systemically, and an acidic environment is not required for absorption. A relatively long half-life allows for once-daily dosing, and liver toxicity is rare at the doses used to treat oral candidiasis. Some reports have suggested that fluconazole may not be appropriate for long-term preventive therapy because resistance to the drug seems to develop in some instances. Known drug interactions include a potentiation of the effects of phenytoin (Dilantin), an antiseizure medication; warfarin compounds (anticoagulants); and sulfonylureas (oral hypoglycemic agents). Other drugs that may interact with fluconazole are summarized in Table 6-2.

ITRACONAZOLE: Itraconazole has proven efficacy against a variety of fungal diseases, including histoplasmosis, blastomycosis, and fungal conditions of the nails. Recently, itraconazole solution was approved for management of oropharyngeal candidiasis, and this appears to have an efficacy equivalent to clotrimazole and fluconazole. As with fluconazole, significant drug interactions are possible, and itraconazole is contraindicated for patients taking astemizole, triazolam, midazolam, and cisapride. (See Table 6-2 for other potential drug interactions.)

POSACONAZOLE: This new triazole compound has been shown to be effective in the management of oropharyngeal candidiasis in patients with HIV infection. Given the cost of this drug and the proven effectiveness of other, less expensive, oral antifungal agents, the use of this medication for treatment of routine oral candidiasis would be difficult to justify.

ECHINOCANDINS: This new class of antifungal drugs acts by interfering with candidal cell wall synthesis. The formation of b-1,3-glucan, which is a principal component of the candidal cell wall, is disrupted and results in permeability of the cell wall with subsequent demise of the candidal organism. These medications are not well absorbed; consequently they must be administered intravenously and are reserved for more life-threatening candidal infections. Examples include caspofungin, micafungin, and anidulafungin.

IODOQUINOL: Although not strictly an antifungal drug, iodoquinol has antifungal and antibacterial properties. When compounded in a cream base with a corticosteroid, this material is very effective as topical therapy for angular cheilitis.

In most cases, oral candidiasis is an annoying superficial infection that is easily resolved by antifungal therapy. If infection should recur after treatment, then a thorough investigation of potential factors that could predispose to candidiasis, including immunosuppression, may be necessary. In only the most severely compromised patient will candidiasis cause deeply invasive disease (Fig. 6-17).

HISTOPLASMOSIS

Histoplasmosis, the most common systemic fungal infection in the United States, is caused by the organism Histoplasma capsulatum. Like several other pathogenic fungi, H. capsulatum is dimorphic, growing as a yeast at body temperature in the human host and as a mold in its natural environment. Humid areas with soil enriched by bird or bat excrement are especially suited to the growth of this organism. This habitat preference explains why histoplasmosis is seen endemically in fertile river valleys, such as the region drained by the Ohio and Mississippi Rivers in the United States. Airborne spores of the organism are inhaled, pass into the terminal passages of the lungs, and germinate.

Approximately 500,000 new cases of histoplasmosis are thought to develop annually in the United States. Other parts of the world, such as Central and South America, Europe, and Asia, also report numerous cases. Epidemiologic studies in endemic areas of the United States suggest that 80% to 90% of the population in these regions has been infected.

CLINICAL AND RADIOGRAPHIC FEATURES: Most cases of histoplasmosis produce either no symptoms or such mild symptoms that the patient does not seek medical treatment. The expression of disease depends on the quantity of spores inhaled, the immune status of the host, and perhaps the strain of H. capsulatum. Most individuals who become exposed to the organism are relatively healthy and do not inhale a large number of spores; therefore, they have either no symptoms or they have a mild, flulike illness for 1 to 2 weeks. The inhaled spores are ingested by macrophages within 24 to 48 hours, and specific T-lymphocyte immunity develops in 2 to 3 weeks. Antibodies directed against the organism usually appear several weeks later. With these defense mechanisms, the host is usually able to destroy the invading organism, although sometimes the macrophages simply surround and confine the fungus so that viable organisms can be recovered years later. Thus patients who formerly lived in an endemic area may have acquired the organism and later express the disease at some other geographic site if they become immunocompromised.

Acute histoplasmosis is a self-limited pulmonary infection that probably develops in only about 1% of people who are exposed to a low number of spores. With a high concentration of spores, as many as 50% to 100% of individuals may experience acute symptoms. These symptoms (e.g., fever, headache, myalgia, nonproductive cough, anorexia) result in a clinical picture similar to that of influenza. Patients are usually ill for 2 weeks, although calcification of the hilar lymph nodes may be detected as an incidental finding on chest radiographs years later.

Chronic histoplasmosis also primarily affects the lungs, although it is much less common than acute histoplasmosis. The chronic form usually affects older, emphysematous, white men or immunosuppressed patients. Clinically, it appears similar to tuberculosis. Patients typically exhibit cough, weight loss, fever, dyspnea, chest pain, hemoptysis, weakness, and fatigue. Chest roentgenograms show upper-lobe infiltrates and cavitation.

Disseminated histoplasmosis is even less common than the acute and chronic types. It occurs in 1 of 2000 to 5000 patients who have acute symptoms. This condition is characterized by the progressive spread of the infection to extrapulmonary sites. It usually occurs in either older, debilitated, or immunosuppressed patients. In some areas of the United States, 2% to 10% of patients with acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS) (see page 277) develop disseminated histoplasmosis. Tissues that may be affected include the spleen, adrenal glands, liver, lymph nodes, gastrointestinal tract, central nervous system (CNS), kidneys, and oral mucosa. Adrenal involvement may produce hypoadrenocorticism (Addison’s disease) (see page 841).

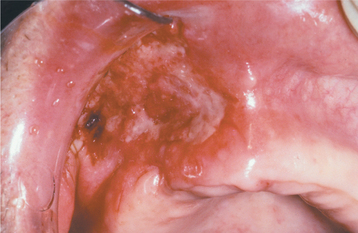

Most oral lesions of histoplasmosis occur with the disseminated form of the disease. The most commonly affected sites are the tongue, palate, and buccal mucosa. The condition usually appears as a solitary, variably painful ulceration of several weeks’ duration; however, some lesions may appear erythematous or white with an irregular surface (Fig. 6-18). The ulcerated lesions have firm, rolled margins, and they may be indistinguishable clinically from a malignancy (Fig. 6-19).

Fig. 6-18 Histoplasmosis. This ulcerated granular lesion involves the maxillary buccal vestibule and is easily mistaken clinically for carcinoma. Biopsy established the diagnosis. (From Allen CM, Blozis GG: Oral mucosal lesions. In Cummings CW, Fredrickson JM, Harker LA et al, editors: Otolaryngology: head and neck surgery, ed 3, St Louis, 1998, Mosby.)

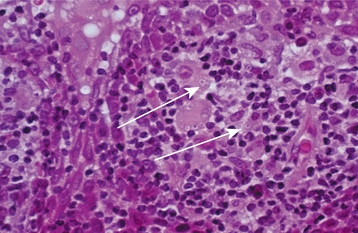

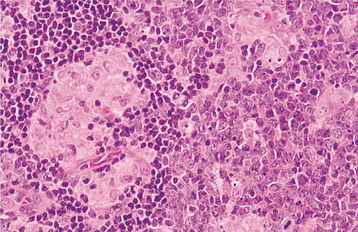

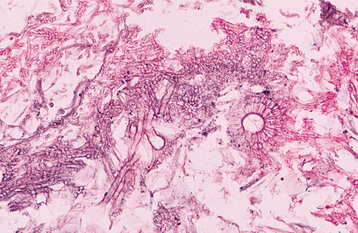

HISTOPATHOLOGIC FEATURES: Microscopic examination of lesional tissue shows either a diffuse infiltrate of macrophages or, more commonly, collections of macrophages organized into granulomas (Fig. 6-20). Multinucleated giant cells are usually seen in association with the granulomatous inflammation. The causative organism can be identified with some difficulty in the routine hematoxylin and eosin (H&E)-stained section; however, special stains, such as the PAS and Grocott-Gomori methenamine silver methods, readily demonstrate the characteristic 1- to 2-mm yeasts of H. capsulatum (Fig. 6-21).

DIAGNOSIS: The diagnosis of histoplasmosis can be made by histopathologic identification of the organism in tissue sections or by culture. Other helpful diagnostic studies include serologic testing in which antibodies directed against H. capsulatum are demonstrated and antigen produced by the yeast is identified.

TREATMENT AND PROGNOSIS: Acute histoplasmosis, because it is a self-limited process, generally warrants no specific treatment other than supportive care with analgesic and antipyretic agents. Often the disease is not treated because the symptoms are so nonspecific and the diagnosis is not readily evident.

Patients with chronic histoplasmosis require treatment, despite the fact that up to half of them may recover spontaneously. Often the pulmonary damage is progressive if it remains untreated, and death may result in up to 20% of these cases. The treatment of choice is intravenous amphotericin B, particularly in severe cases. However, significant kidney damage can result from this therapy; therefore, itraconazole may be used in nonimmunosuppressed patients because it is as-sociated with fewer side effects, but this medication requires daily dosing for at least 3 months. Although ketoconazole and fluconazole have been used for treatment of histoplasmosis, these agents appear to be less effective than itraconazole and less likely to produce a desired therapeutic response.

Disseminated histoplasmosis is a very serious condition that results in death in 80% to 90% of patients if they remain untreated. Amphotericin B is usually indicated for such patients; once the life-threatening phase of the disease is under control, daily itraconazole is necessary for 6 to 18 months. Despite therapy, however, a mortality rate of 7% to 23% is observed. Itraconazole alone may be used if the patient is nonimmunocompromised and has relatively mild to moderate disease; however, the response rate is slower than for patients receiving amphotericin B, and the relapse rate may be higher.

BLASTOMYCOSIS

Blastomycosis is a relatively uncommon disease caused by the dimorphic fungus known as Blastomyces dermatitidis. Although the organism is rarely isolated from its natural habitat, it seems to prefer rich, moist soil, where it grows as a mold. Much of the region in which it grows overlaps the territory associated with H. capsulatum (affecting the eastern half of the United States). The range of blastomycosis extends farther north, however, including Wisconsin, Minnesota, and the Canadian provinces surrounding the Great Lakes. Sporadic cases have also been reported in Africa, India, Europe, and South America. By way of comparison, histoplasmosis appears to be at least ten times more common than blastomycosis. In several series of cases, a prominent adult male predilection has been noted, often with a male-to-female ratio as high as 9:1. Researchers have attributed this to the greater degree of outdoor activity (e.g., hunting, fishing) by men in areas where the organism grows. The occurrence of blastomycosis in immunocompromised patients is relatively rare.

CLINICAL AND RADIOGRAPHIC FEATURES: Blastomycosis is almost always acquired by inhalation of spores, particularly after a rain. The spores reach the alveoli of the lungs, where they begin to grow as yeasts at body temperature. In most patients, the infection is probably halted and contained in the lungs, but it may become hematogenously disseminated in a few instances. In order of decreasing frequency, the sites of dissemination include skin, bone, prostate, meninges, oropharyngeal mucosa, and abdominal organs.

Although most cases of blastomycosis are either asymptomatic or produce only very mild symptoms, patients who do experience symptoms usually have pulmonary complaints. Acute blastomycosis resembles pneumonia, characterized by high fever, chest pain, malaise, night sweats, and productive cough with mucopurulent sputum. Rarely, the infection may precipitate life-threatening adult respiratory distress syndrome.

Chronic blastomycosis is more common than the acute form, and it may mimic tuberculosis; both conditions are often characterized by low-grade fever, night sweats, weight loss, and productive cough. Chest radiographs may appear normal, or they may demonstrate diffuse infiltrates or one or more pulmonary or hilar masses. Unlike the situation with tuberculosis and histoplasmosis, calcification is not typically present. Cutaneous lesions usually represent the spread of infection from the lungs, although occasionally they are the only sign of disease. Such lesions begin as erythematous nodules that enlarge, becoming verrucous or ulcerated (Figs. 6-22 and 6-23).

Fig. 6-22 Blastomycosis. This granular erythematous plaque of cutaneous blastomycosis has affected the facial skin. (Courtesy of Dr. William Welton.)

Fig. 6-23 Blastomycosis. Severe cutaneous infection by Blastomyces dermatitidis. (Courtesy of Dr. Emmitt Costich.)

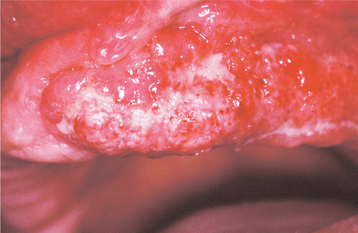

Oral lesions of blastomycosis may result from either extrapulmonary dissemination or local inoculation with the organism. These lesions may have an irregular, erythematous or white intact surface, or they may appear as ulcerations with irregular rolled borders and varying degrees of pain (Figs. 6-24 and 6-25). Clinically, because the lesions resemble squamous cell carcinoma, biopsy and histopathologic examination are required.

HISTOPATHOLOGIC FEATURES: Histopathologic examination of lesional tissue typically shows a mixture of acute inflammation and granulomatous inflammation surrounding variable numbers of yeasts. These organisms are 8 to 20 μm in diameter. They are characterized by a doubly refractile cell wall (Fig. 6-26) and a broad attachment between the budding daughter cell and the parent cell. Like many other fungal organisms, B. dermatitidis can be detected more easily using special stains, such as the Grocott-Gomori methenamine silver and PAS methods. Iden tification of these organisms is especially important because this infection often induces a benign reaction of the overlying epithelium in mucosal or skin lesions called pseudoepitheliomatous (pseudocarcinomatous) hyperplasia. Because this benign elongation of the epithelial rete ridges may look like squamous cell carcinoma at first glance under the microscope, careful inspection of the underlying inflamed lesional tissue is mandatory.

DIAGNOSIS: Rapid diagnosis of blastomycosis can be performed by microscopic examination of either histopathologic sections or an alcohol-fixed cytologic preparation. The most rapid means of diagnosis, however, is the KOH preparation, which may be used for examining scrapings from a suspected lesion. The most accurate method of identifying B. dermatitidis is by obtaining a culture specimen from sputum or fresh biopsy material and growing the organism on Sabouraud’s agar. This is a slow technique, however, sometimes taking as long as 3 to 4 weeks for the characteristic mycelium-to-yeast conversion to take place. A specific DNA probe has been developed, allowing immediate identification of the mycelial phase that usually appears by 5 to 7 days in culture. Serologic studies and skin testing are usually not helpful because of lack of reactivity and specificity.

TREATMENT AND PROGNOSIS: As stated previously, most patients with blastomycosis require no treatment. Even in the case of symptomatic acute blastomycosis, administration of systemic amphotericin B is indicated only if one or more of the following is noted:

• Patient is seriously ill (AIDS, organ transplant recipient, other immune suppression disorder)

Patients with chronic blastomycosis or extrapulmonary lesions need treatment. Itraconazole is generally recommended, particularly if the infection is mild or moderate. Although ketoconazole and fluconazole are active against B. dermatitidis, these drugs have been shown to be less effective than itraconazole. Amphotericin B is reserved for patients who are severely ill or show no response to itraconazole.

Disseminated blastomycosis occurs in only a small percentage of infected patients and, with proper treatment, the outlook for the patient is reasonably good. Still, mortality rates ranging from 4% to 22% have been described over the past 20 years, with men, blacks, and patients with HIV infection tending to have less favorable outcomes.

PARACOCCIDIOIDOMYCOSIS (SOUTH AMERICAN BLASTOMYCOSIS)

Paracoccidioidomycosis is a deep fungal infection that is caused by Paracoccidioides brasiliensis. The condition is seen most frequently in patients who live in either South America (primarily Brazil, Colombia, Venezuela, Uruguay, and Argentina) or Central America. However, immigrants from those regions and visitors to those areas can acquire the infection. Within some endemic areas, the nine-banded armadillo has been shown to harbor P. brasiliensis (similar to the situation seen with leprosy) (see page 198). Although there is no evidence that the armadillo directly infects humans, it may be responsible for the spread of the organism in the environment.

Paracoccidioidomycosis has a distinct predilection for males, with a 15:1 male-to-female ratio typically reported. This striking difference is thought to be attributable to a protective effect of female hormones (because b-estradiol inhibits the transformation of the hyphal form of the organism to the pathogenic yeast form). This theory is supported by the finding of an equal number of men and women who have antibodies directed against the yeast.

CLINICAL FEATURES: Patients with paracoccidioidomycosis are typically middle-aged at the time of diagnosis, and most are employed in agriculture. Most cases of paracoccidioidomycosis are thought to appear initially as pulmonary infections after exposure to the spores of the organism. Although infections are generally self-limiting, P. brasiliensis may spread by a hematogenous or lymphatic route to a variety of tissues, including lymph nodes, skin, and adrenal glands. Adrenal involvement often results in hypoadrenocorticism (Addison’s disease) (see page 841).

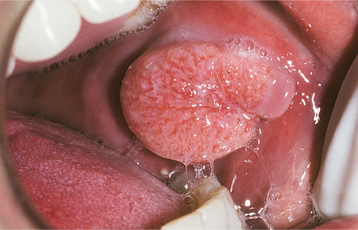

Oral lesions appear as mulberry-like ulcerations that most commonly affect the alveolar mucosa, gingiva, and palate (Fig. 6-27). The lips, tongue, oropharynx, and buccal mucosa are also involved in a significant percentage of cases. In most patients with oral lesions, more than one oral mucosal site is affected.

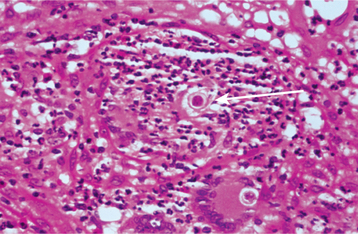

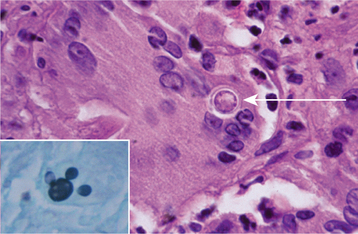

HISTOPATHOLOGIC FEATURES: Microscopic evaluation of tissue obtained from an oral lesion may reveal pseudoepitheliomatous hyperplasia in addition to ulceration of the overlying surface epithelium. P. brasiliensis elicits a granulomatous inflammatory host response that is characterized by collections of epithelioid macrophages and multinucleated giant cells (Fig. 6-28). Scattered, large (up to 30 μm in diameter) yeasts are readily identified after staining of the tissue sections with the Grocott-Gomori methenamine silver or PAS method. The organisms often show multiple daughter buds on the parent cell, resulting in an appearance that has been described as resembling “Mickey Mouse ears” or the spokes of a ship’s steering wheel (“mariner’s wheel”).

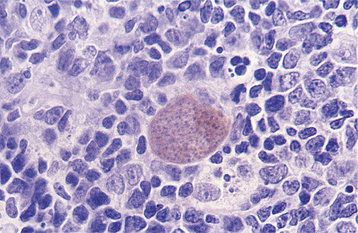

Fig. 6-28 Paracoccidioidomycosis. This high-power photomicrograph shows a large yeast of Paracoccidioides brasiliensis (arrow) within the cytoplasm of a multinucleated giant cell. A section stained with the Grocott-Gomori methenamine silver method (inset) illustrates the characteristic “Mickey Mouse ears” appearance of the budding yeasts. (Courtesy of Dr. Ricardo Santiago Gomez.)

DIAGNOSIS: Demonstration of the characteristic multiple budding yeasts in the appropriate clinical setting is usually adequate to establish a diagnosis of paracoccidioidomycosis. Specimens for culture can be obtained, but P. brasiliensis grows quite slowly.

TREATMENT AND PROGNOSIS: The method of management of patients with paracoccidioidomycosis depends on the severity of the disease presentation. Sulfonamide derivatives have been used since the 1940s to treat this infection. These drugs are still used today in many instances to treat mild-to-moderate cases, particularly in developing countries with limited access to the newer, more expensive antifungal agents. For severe involvement, intravenous amphotericin B is usually indicated. Cases that are not life threatening are best managed by oral itraconazole, although therapy may be needed for several months. Ketoconazole can also be used, although the side effects are typically greater than those associated with itraconazole.

COCCIDIOIDOMYCOSIS (SAN JOAQUIN VALLEY FEVER; VALLEY FEVER; COCCI)

Coccidioides immitis is the fungal organism responsible for coccidioidomycosis. C. immitis grows saprophytically in the alkaline, semiarid, desert soil of the southwestern United States and Mexico, with isolated regions also noted in Central and South America. As with several other pathogenic fungi, C. immitis is a dimorphic organism, appearing as a mold in its natural environment of the soil and as a yeast in tissues of the infected host. Arthrospores produced by the mold become airborne and can be inhaled into the lungs of the human host, producing infection.

Coccidioidomycosis is confined to the Western hemisphere and is endemic throughout the desert regions of southwestern United States and Mexico; however, with modern travel taking many visitors to and from the Sunbelt, this disease can be encountered virtually anywhere in the world. It is estimated that 100,000 people are infected annually in the United States, although 60% of this group are asymptomatic.

CLINICAL FEATURES: Most infections with C. immitis are asymptomatic, although approximately 40% of infected patients experience a flulike illness and pulmonary symptoms within 1 to 3 weeks after inhaling the arthrospores. Fatigue, cough, chest pain, myalgias, and headache are commonly reported, lasting several weeks with spontaneous resolution in most cases. Occasionally, the immune response may trigger a hypersensitivity reaction that causes the development of an erythema multiforme–like cutaneous eruption (see page 776) or erythema nodosum. Erythema nodosum is a condition that usually affects the skin of the legs and is characterized by the appearance of multiple painful erythematous inflammatory nodules in the subcutaneous connec-tive tissue. This hypersensitivity reaction occurring in conjunction with coccidioidomycosis is termed valley fever, and it resolves as the host cell–mediated immune response controls the pulmonary infection.

Chronic progressive pulmonary coccidioidomycosis is relatively rare. It mimics tuberculosis, with its clinical presentation of persistent cough, hemoptysis, chest pain, low-grade fever, and weight loss.

Disseminated coccidioidomycosis occurs when the organism spreads hematogenously to extrapulmonary sites. This occurs in less than 1% of cases, but it is a more serious problem. The most commonly involved areas include skin, lymph nodes (including cervical lymph nodes), bone and joints, and the meninges. Immunosuppression greatly increases the risk of dissemination. The following groups are particularly susceptible:

• Patients taking large doses of systemic corticosteroids (organ transplant recipients)

• Patients who are being treated with cancer chemotherapy

Infants and older adult patients, both of whom may have suboptimally functioning immune systems, also may be at increased risk for disseminated disease. Persons of color (e.g., blacks, Filipinos, Native Americans) also seem to have an increased risk, but it is unclear whether their susceptibility is due to genetic causes or socioeconomic factors, such as poor nutrition.

The cutaneous lesions may appear as papules, subcutaneous abscesses, verrucous plaques, and granulomatous nodules. Of prime significance to the clinician is the predilection for these lesions to develop in the area of the central face, especially the nasolabial fold. Oral lesions are distinctly uncommon, and these have been described as ulcerated granulomatous nodules.

HISTOPATHOLOGIC FEATURES: Biopsy material shows large (20 to 60 mm), round spherules that may contain numerous endospores. The host response may be variable, ranging from a suppurative, neutrophilic infiltrate to a granulomatous inflammatory response. In some cases the two patterns of inflammation are seen concurrently. Special stains, such as the PAS and Grocott-Gomori methenamine silver methods, enable the pathologist to identify the organism more readily.

DIAGNOSIS: The diagnosis of coccidioidomycosis can be confirmed by culture or identification of characteristic organisms in biopsy material. If the organisms do not have a classic microscopic appearance, then in situ hybridization studies using specific complementary DNA probes for C. immitis can be performed to definitively identify the fungus. Cytologic preparations from bronchial swabbings or sputum samples may also reveal the organisms.

Serologic studies are helpful in supporting the diagnosis, and they may be performed at the same time as skin testing. Skin testing by itself may be of limited value in determining the diagnosis because many patients in endemic areas have already been exposed to the organism and have positive test findings.

TREATMENT: The decision whether or not to treat a particular patient affected by coccidioidomycosis depends on the severity and extent of the infection and the patient’s immune status. Relatively mild symptoms in an immunocompetent person do not warrant treatment. Amphotericin B is administered for the following groups:

• Patients with severe pulmonary infection

• Patients who have disseminated disease

• Patients who appear to be in a life-threatening situation concerning the infection

For many cases of coccidioidomycosis, fluconazole or itraconazole is the drug of choice, usually given in high doses for an extended period of time. Although the response of the disease to these oral azole medications may be somewhat slower than that of amphotericin B, the side effects and complications of therapy are far fewer. Ketoconazole also may be used as an alternative treatment for mild-to-moderate cases of coccidioidomycosis.

CRYPTOCOCCOSIS

Cryptococcosis is a relatively uncommon fungal disease caused by the yeast Cryptococcus neoformans. This organism normally causes no problem in immunocompetent people, but it can be devastating to the immunocompromised patient. The incidence of cryptococcosis increased dramatically during the 1990s, primarily because of the AIDS epidemic. At that time, this was the most common life-threatening fungal infection in these patients. However, with the advent of highly active anti-retroviral therapy (HAART) (see page 280), this complication has become less of a problem in the United States. In countries where the population cannot afford HAART, cryptococcosis remains a significant cause of death for AIDS patients. The disease has a worldwide distribution because of its association with the pigeon (with the organism living in the deposits of excreta left by the birds). Unlike many other pathogenic fungi, C. neoformans grows as a yeast both in the soil and in infected tissue. The organism usually produces a prominent mucopolysaccharide capsule that appears to protect it from host immune defenses.

The disease is acquired by inhalation of C. neoformans spores into the lungs, resulting in an immediate influx of neutrophils, which destroys most of the yeasts. Macrophages soon follow, although resolution of infection in the immunocompetent host ultimately depends on an intact cell-mediated immune system.

CLINICAL FEATURES: Primary cryptococcal infection of the lungs is often asymptomatic; however, a mild flulike illness may develop. Patients complain of productive cough, chest pain, fever, and malaise. Most patients with a diagnosis of cryptococcosis have a significant underlying medical problem related to immune suppression (e.g., systemic corticosteroid therapy, cancer chemotherapy, malignancy, AIDS). It is estimated that 5% to 10% of AIDS patients acquire this infection (see page 264).

Dissemination of the infection is common in these immunocompromised patients, and the most frequent site of involvement is the meninges, followed by skin, bone, and the prostate gland.

Cryptococcal meningitis is characterized by headache, fever, vomiting, and neck stiffness. In many instances, this is the initial sign of the disease.

Cutaneous lesions develop in 10% to 15% of patients with disseminated disease. These are of particular importance to the clinician, because the skin of the head and neck is often involved. The lesions appear as erythematous papules or pustules that may ulcerate, discharging a puslike material rich in cryptococcal organisms (Fig. 6-29).

Fig. 6-29 Cryptococcosis. These papules of the facial skin represent disseminated cryptococcal infection in a patient infected with human immunodeficiency virus (HIV). (Courtesy of Dr. Catherine Flaitz.)

Although oral lesions are relatively rare, they have been described either as craterlike, nonhealing ulcers that are tender on palpation or as friable papillary erythematous plaques. Dissemination to salivary gland tissue also has been reported rarely.

HISTOPATHOLOGIC FEATURES: Microscopic sections of a cryptococcal lesion generally show a granulomatous inflammatory response to the organism. The extent of the response may vary, however, depending on the host’s immune status and the strain of the organism. The yeast appears as a round-to-ovoid structure, 4 to 6 μm in diameter, surrounded by a clear halo that represents the capsule. Staining with the PAS or Grocott-Gomori methenamine silver method readily identifies the fungus; moreover, a mucicarmine stain uniquely demonstrates its mucopolysaccharide capsule.

DIAGNOSIS: The diagnosis of cryptococcosis can be made by several methods, including biopsy and culture. Detection of cryptococcal polysaccharide antigen in the serum or cerebrospinal fluid is also useful as a diagnostic procedure.

TREATMENT AND PROGNOSIS: Management of cryptococcal infections can be very difficult because most of the affected patients have an underlying medical problem. Before amphotericin B was developed, cryptococcosis was almost uniformly fatal. For cryptococcal meningitis, a combination of systemic amphotericin B and another antifungal drug (flucytosine) is used initially for 2 weeks in most cases to treat this disease. Then, either fluconazole or itraconazole is given for an additional minimal period of 10 weeks. For relatively mild cases of pulmonary cryptococcosis, only fluconazole or itraconazole may be used. These drugs produce far fewer side effects than do amphotericin B and flucytosine, and they have proven to be important therapeutic tools for managing this type of infection.

ZYGOMYCOSIS (MUCORMYCOSIS; PHYCOMYCOSIS)

Zygomycosis is an opportunistic, frequently fulminant, fungal infection that is caused by normally saprobic organisms of the class Zygomycetes, including such genera as Absidia, Mucor, Rhizomucor, and Rhizopus. These organisms are found throughout the world, growing in their natural state on a variety of decaying organic materials. Numerous spores may be liberated into the air and inhaled by the human host.

Zygomycosis may involve any one of several areas of the body, but the rhinocerebral form is most relevant to the oral health care provider. Zygomycosis is noted especially in insulin-dependent diabetics who have uncontrolled diabetes and are ketoacidotic; ketoacidosis inhibits the binding of iron to transferrin, allowing serum iron levels to rise. The growth of these fungi is enhanced by iron, and patients who are taking deferoxamine (an iron-chelating agent used in the treatment of diseases such as thalassemia) are also at increased risk for developing zygomycosis. As with many other fungal diseases, this infection affects immunocom-promised patients as well, including bone marrow transplant recipients, patients with AIDS, and those receiving systemic corticosteroid therapy. Only rarely has zygomycosis been reported in apparently healthy individuals.

CLINICAL AND RADIOGRAPHIC FEATURES: The presenting symptoms of rhinocerebral zygomycosis may be exhibited in several ways. Patients may experience nasal obstruction, bloody nasal discharge, facial pain or headache, facial swelling or cellulitis, and visual disturbances with concurrent proptosis. Symptoms related to cranial nerve involvement (e.g., facial paralysis) are often present. With progression of disease into the cranial vault, blindness, lethargy, and seizures may develop, followed by death.

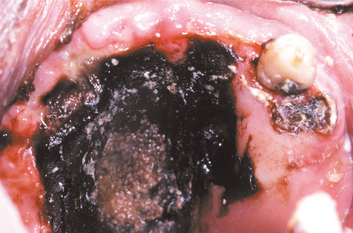

If the maxillary sinus is involved, the initial presentation may be seen as intraoral swelling of the maxillary alveolar process, the palate, or both. If the condition remains untreated, palatal ulceration may evolve, with the surface of the ulcer typically appearing black and necrotic. Massive tissue destruction may result if the condition is not treated (Figs. 6-30 and 6-31).

Fig. 6-30 Zygomycosis. Diffuse tissue destruction involving the nasal and maxillary structures caused by a Mucor species. (Courtesy of Dr. Sadru Kabani.)

Fig. 6-31 Zygomycosis. The extensive black, necrotic lesion of the palate represents zygomycotic infection that extended from the maxillary sinus in a patient with poorly controlled type I diabetes mellitus. (Courtesy of Dr. Michael Tabor.)

Radiographically, opacification of the sinuses may be observed in conjunction with patchy effacement of the bony walls of the sinuses (Fig. 6-32). Such a picture may be difficult to distinguish from that of a malignancy affecting the sinus area.

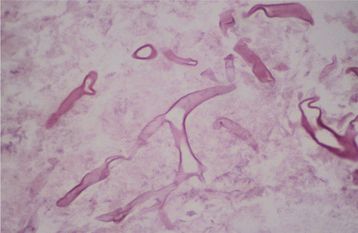

HISTOPATHOLOGIC FEATURES: Histopathologic examination of lesional tissue shows extensive necrosis with numerous large (6 to 30 μm in diameter), branching, nonseptate hyphae at the periphery (Fig. 6-33). The hyphae tend to branch at 90-degree angles. The extensive tissue destruction and necrosis associated with this disease are undoubtedly attribut able to the preference of the fungi for invasion of small blood vessels. This disrupts normal blood flow to the tissue, resulting in infarction and necrosis. A neutrophilic infiltrate usually predominates in the viable tissue, but the host inflammatory cell response to the infection may be minimal, particularly if the patient is immunosuppressed.

DIAGNOSIS: Diagnosis of zygomycosis is usually based on the histopathologic findings. Because of the grave nature of this infection, appropriate therapy must be instituted in a timely manner (often without the benefit of definitive culture results).

TREATMENT AND PROGNOSIS: Successful treatment of zygomycosis consists of rapid accurate diagnosis of the condition, followed by radical surgical débridement of the infected, necrotic tissue and systemic administration of high doses of one of the lipid formulations of amphotericin B. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the head may be useful in determining the extent of disease involvement so that surgical margins can be planned. In addition, control of the patient’s underlying disease (e.g., diabetic ketoacidosis) must be attempted. Despite such therapy, the prognosis is usually poor, with approximately 60% of patients who develop rhinocerebral zygomycosis dying of their disease. Should the patient survive, the massive tissue destruction that remains presents a challenge both functionally and aesthetically. Prosthetic obturation of palatal defects may be necessary.

ASPERGILLOSIS

Aspergillosis is a fungal disease that is characterized by noninvasive and invasive forms. Noninvasive aspergillosis usually affects a normal host, appearing either as an allergic reaction or a cluster of fungal hyphae. Localized invasive infection of damaged tissue may be seen in a normal host, but a more extensive invasive infection is often evident in the immunocompromised patient. With the advent of intensive chemotherapeutic regimens, the AIDS epidemic, and both solid-organ and bone marrow transplantation, the prevalence of invasive aspergillosis has increased dramatically in the past 20 years. Patients with uncontrolled diabetes mellitus are also susceptible to Aspergillus spp. infections. Rarely, invasive aspergillosis has been reported to affect the paranasal sinuses of apparently normal immunocompetent individuals.

Normally, the various species of the Aspergillus genus reside worldwide as saprobic organisms in soil, water, or decaying organic debris. Resistant spores are released into the air and inhaled by the human host, resulting in opportunistic fungal infection second in frequency only to candidiasis. Interestingly, most species of Aspergillus cannot grow at 37°C; only the pathogenic species have the ability to replicate at body temperature.

The two most commonly encountered species of Aspergillus in the medical setting are A. flavus and A. fumigatus, with A. fumigatus being responsible for 90% of the cases of aspergillosis. The patient may acquire such infections in the hospital (“nosocomial” infection), especially if remodeling or building construction is being performed in the immediate area. Such activity often stirs up the spores, which are then inhaled by the patient.

CLINICAL FEATURES: The clinical manifestations of aspergillosis vary, depending on the host immune status and the presence or absence of tissue damage. In the normal host, the disease may appear as an allergy affecting either the sinuses (allergic fungal sinusitis) or the bronchopulmonary tract. An asthma attack may be triggered by inhalation of spores by a susceptible person. Sometimes a low-grade infection becomes established in the maxillary sinus, resulting in a mass of fungal hyphae called an aspergilloma. Occasionally, the mass will undergo dystrophic calcification, producing a radiopaque body called an antrolith within the sinus.

Another presentation that may be encountered by the oral health care provider is aspergillosis after tooth extraction or endodontic treatment, especially in the maxillary posterior segments. Presumably, tissue damage predisposes the sinus to infection, resulting in symptoms of localized pain and tenderness accompanied by nasal discharge. Immunocompromised patients are particularly susceptible to oral aspergillosis, and some investigators have suggested that the portal of entry may be the marginal gingiva and gingival sulcus. Painful gingival ulcerations are initially noted, and peripherally the mucosa and soft tissue develops diffuse swelling with a gray or violaceous hue (Fig. 6-34). If the disease is not treated, extensive necrosis, seen clinically as a yellow or black ulcer, and facial swelling evolve.

Fig. 6-34 Aspergillosis. This young woman developed a painful purplish swelling of her hard palate after induction chemotherapy for leukemia.

Disseminated aspergillosis occurs principally in immunocompromised patients, particularly in those who have leukemia or who are taking high daily doses of corticosteroids. Such patients usually exhibit symptoms related to the primary site of inoculation: the lungs. The patient typically has chest pain, cough, and fever, but such symptoms are vague. Therefore, obtaining an early, accurate diagnosis may be difficult. Once the fungal organism obtains access to the bloodstream, infection can spread to such sites as the CNS, eye, skin, liver, gastrointestinal tract, bone, and thyroid gland.

HISTOPATHOLOGIC FEATURES: Tissue sections of invasive Aspergillus spp. lesions show varying numbers of branching, septate hyphae, 3 to 4 μm in diameter (Figs. 6-35 and 6-36). These hyphae show a tendency to branch at an acute angle and to invade adjacent small blood vessels. Occlusion of the vessels often results in the characteristic pattern of necrosis associated with this disease. In the immunocompetent host, a granulomatous inflammatory response—in addition to necrosis—can be expected. In the immunocompromised patient, however, the inflam matory response is often weak or absent, leading to extensive tissue destruction.

Fig. 6-35 Aspergillosis. This photomicrograph reveals fungal hyphae and a fruiting body of an Aspergillus species.

Fig. 6-36 Aspergillosis. This high-power photomicrograph shows the characteristic septate hyphae of Aspergillus species. (Grocott-Gomori methenamine silver stain.)

Noninvasive forms of aspergillosis have histopathologic features that differ from invasive aspergillosis, however. The aspergilloma, for example, is characterized by a tangled mass of hyphae with no evidence of tissue invasion. Allergic fungal sinusitis, on the other hand, histopathologically exhibits large pools of eosinophilic inspissated mucin with interspersed sheetlike collections of lymphocytes and eosinophils. Relatively few fungal hyphae are identified, and then only with careful examination after methenamine silver staining.

DIAGNOSIS: Although the diagnosis of fungal infection can be established by identification of hyphae within tissue sections, this finding is only suggestive of aspergillosis because other fungal organisms may appear similar microscopically. Ideally, the diagnosis should be supported by culture of the organism from the lesion; however, from a practical standpoint, treatment may need to be initiated immediately to prevent the patient’s demise. Culture specimens of sputum and blood are of limited value because they are often negative despite disseminated disease.

TREATMENT AND PROGNOSIS: Treatment depends on the clinical presentation of aspergillosis. For immunocompetent patients with a noninvasive aspergilloma, surgical débridement may be all that is necessary. Patients who have allergic fungal sinusitis are treated with débridement and corticosteroid drugs. For localized invasive aspergillosis in the immunocompetent host, débridement followed by antifungal medication is indicated. Although systemic amphotericin B therapy was considered appropriate in the past, recent studies have shown that voriconazole, a triazole antifungal agent, is more effective for treating these patients. In one large series of patients with invasive aspergillosis, 71% of those treated with voriconazole were alive after 12 weeks of therapy, compared with 58% survival in the group who received standard amphotericin B treatment. Itraconazole has also been approved as an alternative therapy. Immunocompromised patients who have invasive aspergillosis should be treated by aggressive débridement of necrotic tissue, com-bined with systemic antifungal therapy as described previously.

The prognosis for immunocompromised patients is much worse compared with immunocompetent individuals, particularly if the infection is disseminated. Even with appropriate therapy, only about one third of these patients survive. Because aspergillosis in the immunocompromised patient usually develops while the individual is hospitalized, particular attention should be given to the ventilation system in the hospital to prevent patient exposure to the airborne spores of Aspergillus spp.

TOXOPLASMOSIS

Toxoplasmosis is a relatively common disease caused by the obligate intracellular protozoal organism Toxoplasma gondii. For normal, healthy adults, the organism poses no problems, and an estimated 16% to 23% of adults in the United States may have had asymptomatic infection, based on an epidemiologic study that examined serologic samples from more than 4000 randomized individuals. However, the prevalence of infection has considerable geographic variation around the world. Unfortunately, the disease can be devastating for the developing fetus or the immunocompromised patient. Other mammals, particularly members of the cat family, are vulnerable to infection, and cats are considered to be the definitive host. T. gondii multiplies in the intestinal tract of the cat by means of a sexual life cycle, discharging numerous oocysts in the cat feces. Another animal or human can ingest these oocysts, resulting in the production of disease.

CLINICAL FEATURES: In the normal, immunocompetent individual, infection with T. gondii is often asymptomatic. If symptoms develop, they are usually mild and resemble infectious mononucleosis; patients may have a low-grade fever, cervical lymphadenopathy, fatigue, and muscle or joint pain. These symptoms may last from a few weeks to a few months, although the host typically recovers without therapy. Sometimes the lymphadenopathy involves one or more of the lymph nodes in the paraoral region, such as the buccal or submental lymph node. In such instances, the oral health care provider may discover the disease.

In immunosuppressed patients, toxoplasmosis may represent a new, primary infection or, more frequently, reactivation of previously encysted organisms. The principal groups at risk include the following:

Manifestations of infection can include necrotizing encephalitis, pneumonia, and myositis or myocarditis. In the United States, it is estimated that from 3% to 10% of AIDS patients (see page 264) will experience CNS involvement. CNS infection is very serious. Clinically, the patient may complain of headache, lethargy, disorientation, and hemiparesis.

Congenital toxoplasmosis occurs when a nonimmune mother contracts the disease during her pregnancy and the organism crosses the placental barrier, infecting the developing fetus. The potential effects of blindness, mental retardation, and delayed psychomotor development are most severe if the infection occurs during the first trimester of pregnancy.

HISTOPATHOLOGIC FEATURES: Histopathologic examination of a lymph node obtained from a patient with active toxoplasmosis shows characteristic reactive germinal centers exhibiting an accumulation of eosinophilic macrophages. The macro-phages encroach on the germinal centers and accumulate within the subcapsular and sinusoidal regions of the node (Fig. 6-37).

DIAGNOSIS: The diagnosis of toxoplasmosis is usually established by identification of rising serum antibody titers to T. gondii within 10 to 14 days after infection. Immunocompromised patients, however, may not be able to generate an antibody response; therefore, the diagnosis may rest on the clinical findings and the response of the patient to therapy.

Biopsy of an involved lymph node may suggest the diagnosis, and the causative organisms can sometimes be detected immunohistochemically using antibodies directed against T. gondii–specific antigens (Fig. 6-38). The diagnosis should also be confirmed by serologic studies, if possible.

TREATMENT AND PROGNOSIS: Most healthy adults with toxoplasmosis require no specific treatment because of the mild symptoms and self-limiting course. Perhaps more importantly, pregnant women should avoid situations that place them at risk for the disease. Handling or eating raw meat or cleaning a cat litter box should be avoided until after delivery. If exposure during pregnancy is suspected, treatment with a combination of sulfadiazine and pyrimethamine often prevents transmission of T. gondii to the fetus. Because these drugs act by inhibiting folate metabolism of the protozoan, folinic acid is given concurrently to help prevent hematologic complications in the patient. A similar drug regimen is used to treat immunosuppressed individuals with toxoplasmosis, although clindamycin may be substituted for sulfadiazine in managing patients who are allergic to sulfa drugs. Because most cases of toxoplasmosis in AIDS patients represent reactivation of encysted organisms, prophylactic administration of trimethoprim and sul famethoxazole is generally recommended, particularly if the patient’s CD4+ T-lymphocyte count is less than 100 cells/μL.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Akpan, A, Morgan, R. Oral candidiasis. Postgrad Med J. 2002;78:455–459.

Allen, CM. Diagnosing and managing oral candidiasis. J Am Dent Assoc. 1992;123:77–82.

Arendoff, TM, Walker, DM. The prevalence and intra-oral distribution of Candida albicans in man. Arch Oral Biol. 1980;25:1–10.

Barbeau, J, Séguin, J, Goulet, JP, et al. Reassessing the presence of Candida albicans in denture-related stomatitis. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 2003;95:51–59.

Baughman, RA. Median rhomboid glossitis: a developmental anomaly? Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol. 1971;31:56–65.

Bennett, JE. Echinocandins for candidemia in adults without neutropenia. N Engl J Med. 2006;355:1154–1159.

Bergendal, T, Isacsson, G. A combined clinical, mycological and histological study of denture stomatitis. Acta Odontol Scand. 1983;41:33–44.

Blomgren, J, Berggren, U, Jontell, M. Fluconazole versus nystatin in the treatment of oral candidiasis. Acta Odontol Scand. 1998;56:202–205.

Eisenbarth, GS, Gottlieb, PA. Autoimmune polyendocrine syndromes. N Engl J Med. 2004;350:2068–2079.

Fotos, PG, Vincent, SD, Hellstein, JW. Oral candidosis: clinical, historical and therapeutic features of 100 cases. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol. 1992;74:41–49.

Heimdahl, A, Nord, CE. Oral yeast infections in immunocompromised and seriously diseased patients. Acta Odontol Scand. 1990;48:77–84.

Holmstrup, P, Axéll, T. Classification and clinical manifestations of oral yeast infections. Acta Odontol Scand. 1990;48:57–59.

Kleinegger, CL, Lockhart, SR, Vargas, K, et al. Frequency, intensity, species, and strains of oral Candida vary as a function of host age. J Clin Microbiol. 1996;34:2246–2254.

Lehner, T. Oral thrush, or acute pseudomembranous candidiasis: a clinicopathologic study of forty-four cases. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol. 1964;18:27–37.

Monaco, JG, Pickett, AB. The role of Candida in inflammatory papillary hyperplasia. J Prosthet Dent. 1981;45:470–471.

Odds, FC, Arai, T, Disalvo, AF, et al. Nomenclature of fungal diseases: a report and recommendations from a sub-committee of the International Society for Human and Animal Mycology (ISHAM). J Med Vet Mycol. 1992;30:1–10.

Öhman, S-C, Dahlen, G, Moller, A, et al. Angular cheilitis: a clinical and microbial study. J Oral Pathol. 1986;15:213–217.

Peterson, P, Pitkänen, J, Sillanpää, N, et al. Autoimmune polyendocrinopathy candidiasis ectodermal dystrophy (APECED): a model disease to study molecular aspects of endocrine autoimmunity. Clin Exp Immunol. 2004;135:348–357.

Rautemaa, R, Hietanen, J, Niissalo, S, et al. Oral and oesophageal squamous cell carcinoma—a complication or component of autoimmune polyendocrinopathy-candidiasis-ectodermal dystrophy (APECED, APS-I). Oral Oncol. 2007;43:607–613.

Rodu, B, Griffin, IL, Gockerman, JP. Oral candidiasis in cancer patients. South Med J. 1984;77:312–314.

Samaranayake, LP, Cheung, LK, Samaranayake, YH. Candidiasis and other fungal diseases of the mouth. Dermatol Ther. 2002;15:251–269.

Sanguineti, A, Carmichael, JK, Campbell, K. Fluconazole-resistant Candida albicans after long-term suppressive therapy. Arch Intern Med. 1993;153:1122–1124.

Sitheeque, MAM, Samaranayake, LP. Chronic hyperplastic candidosis/candidiasis (candidal leukoplakia). Crit Rev Oral Biol Med. 2003;14:253–267.

Terai, H, Shimahara, M. Atrophic tongue associated with Candida. J Oral Pathol Med. 2005;34:397–400.

Terrell, CL. Antifungal agents. II. The azoles. Mayo Clin Proc. 1999;74:78–100.

Vazquez, JA, Skiest, DJ, Nieto, L, et al. A multicenter randomized trial evaluation posaconazole versus fluconazole for the treatment of oropharyngeal candidiasis in subjects with HIV/AIDS. Clin Infect Dis. 2006;42:1179–1186.

Bradsher, RW. Histoplasmosis and blastomycosis. Clin Infect Dis. 1996;22(suppl 2):S102–S111.

Couppié, P, Clyti, E, Nacher, M, et al. Acquired immunodeficiency syndrome-related oral and/or cutaneous histoplasmosis: a descriptive and comparative study of 21 cases in French Guiana. Int J Dermatol. 2002;41:571–576.

Leal-Alcure, M, Di Hipólito-Júnior, O, Paes de Almeida, O, et al. Oral histoplasmosis in an HIV-negative patient. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 2006;101:E33–E36.

Lortholary, O, Denning, DW, Dupont, B. Endemic mycoses: a treatment update. J Antimicrob Chemother. 1999;43:321–331.

Motta, ACF, Galo, R, Grupioni-Lourenço, A, et al. Unusual orofacial manifestations of histoplasmosis in renal transplanted patient. Mycopathologia. 2006;161:161–165.

Myskowski, PL, White, MH, Ahkami, R. Fungal disease in the immunocompromised host. Dermatol Clin. 1997;15:295–305.

Samaranayake, LP. Oral mycoses in HIV infection. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol. 1992;73:171–180.

Sarosi, GA, Johnson, PC. Disseminated histoplasmosis in patients infected with human immunodeficiency virus. Clin Infect Dis. 1992;14(suppl 1):S60–S67.

Sharma, OP. Histoplasmosis: a masquerader of sarcoidosis. Sarcoidosis. 1991;8:10–13.

Wheat, LJ, Kauffman, CA. Histoplasmosis. Infect Dis Clin North Am. 2003;17:1–19.

Areno, JP, Campbell, GD, George, RB. Diagnosis of blastomycosis. Semin Respir Infect. 1997;12:252–262.

Assaly, RA, Hammersley, JR, Olson, DE, et al. Disseminated blastomycosis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2003;48:123–127.

Bradsher, RW. Clinical features of blastomycosis. Semin Respir Infect. 1997;12:229–234.

Bradsher, RW, Chapman, SW, Pappas, PG. Blastomycosis. Infect Dis Clin North Am. 2003;17:21–40.

Davies, SF, Sarosi, GA. Epidemiological and clinical features of pulmonary blastomycosis. Semin Resp Infect. 1997;12:206–218.

Dworkin, MS, Duckro, AN, Proia, L, et al. The epidemiology of blastomycosis in Illinois and factors associated with death. Clin Infect Dis. 2005;41:e107–e111.

Greenberg, SB. Serious waterborne and wilderness infections. Crit Care Clin. 1999;15:387–414.

Klein, BS, Vergeront, JM, Weeks, RJ, et al. Isolation of Blastomyces dermatitidis in soil associated with a large outbreak of blastomycosis in Wisconsin. N Engl J Med. 1986;314:529–534.

Lemos, LB, Baliga, M, Guo, M. Blastomycosis: the great pretender can also be an opportunist—initial clinical diagnosis and underlying diseases in 123 patients. Ann Diagn Pathol. 2002;6:194–203.

Meyer, KC, McManus, F-J, Maki, DG. Overwhelming pulmonary blastomycosis associated with the adult respiratory distress syndrome. N Engl J Med. 1993;329:1231–1236.

Reder, PA, Neel, B. Blastomycosis in otolaryngology: review of a large series. Laryngoscope. 1993;103:53–58.

Rose, HD, Gingrass, DJ. Localized oral blastomycosis mimicking actinomycosis. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol. 1982;54:12–14.

Bagagli, E, Franco, M, Bosco, S, et al. High frequency of Paracoccidioides brasiliensis infection in armadillos (Dasypus novemcinctus): an ecological study. Med Mycol. 2003;41:217–223.

Bethlem, EP, Capone, D, Maranhao, B, et al. Paracoccidioidomycosis. Curr Opin Pulm Med. 1999;5:319–325.

Bruinmet, E, Castaneda, E, Restrepo, A. Paracoccidioidomycosis: an update. Clin Microbiol Rev. 1993;6:89–117.

Godoy, H, Reichart, PA. Oral manifestations of paracoccidioidomycosis. Report of 21 cases from Argentina. Mycoses. 2003;46:412–417.

Gorete dos Santos-Nogueira, M, Queiroz-Andrade, GM, Tonelli, E. Clinical evolution of paracoccidioidomycosis in 38 children and teenagers. Mycopathologia. 2006;161:73–81.

Paes de Almeida, O, Jorge, J, Scully, C. Paracoccidioidomycosis of the mouth: an emerging deep mycosis. Crit Rev Oral Biol Med. 2003;14:268–274.

San-Blas, G. Paracoccidioidomycosis and its etiologic agent Paracoccidioides brasiliensis. J Med Vet Mycol. 1993;31:99–113.