Physical and Chemical Injuries

Chemical Injuries of the Oral Mucosa

Noninfectious Oral Complications of Antineoplastic Therapy

Bisphosphonate-Associated Osteonecrosis

Orofacial Complications of Methamphetamine Abuse

Oral Trauma from Sexual Practices

Amalgam Tattoo and Other Localized Exogenous Pigmentations

Oral Piercings and Other Body Modifications

Systemic Metallic Intoxication

Drug-Related Discolorations of the Oral Mucosa

Reactive Osseous and Chondromatous Metaplasia

Oral Ulceration with Bone Sequestration

LINEA ALBA

Linea alba (“white line”) is a common alteration of the buccal mucosa that most likely is associated with pressure, frictional irritation, or sucking trauma from the facial surfaces of the teeth. In one study of 256 young men, the alteration was present in 13%; in another study of 993 adolescents, linea alba was the second most common oral mucosal pathosis and affected 5.3%. No other associated problem, such as insufficient horizontal overlap or rough restorations of the teeth, is necessary for the development of linea alba.

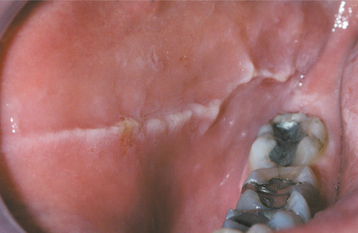

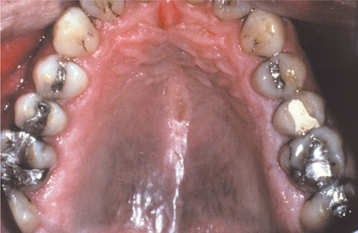

CLINICAL FEATURES: As the name implies, the alteration consists of a white line that usually is bilateral. It may be scalloped and is located on the buccal mucosa at the level of the occlusal plane of the adjacent teeth (Fig. 8-1). The line varies in prominence and usually is restricted to dentulous areas. It often is more pronounced adjacent to the posterior teeth.

MORSICATIO BUCCARUM (CHRONIC CHEEK CHEWING)

Morsicatio buccarum is a classic example of medical terminology gone astray; it is the scientific term for chronic cheek chewing. Morsicatio comes from the Latin word morsus, or bite. Chronic nibbling produces lesions that are located most frequently on the buccal mucosa; however, the labial mucosa (morsicatio labiorum) and the lateral border of the tongue (morsicatio linguarum) also may be involved. Similar changes have been seen as a result of suction and in glassblowers whose technique produces chronic irritation of the buccal mucosa.

A higher prevalence of classic morsicatio buccarum has been found in people who are under stress or who exhibit psychologic conditions. Most patients are aware of their habit, although many deny the self-inflicted injury or perform the act subconsciously. The occurrence is twice as prevalent in women and three times more prevalent after age 35. At any given time, one in every 800 adults has active lesions.

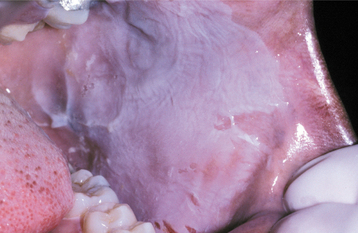

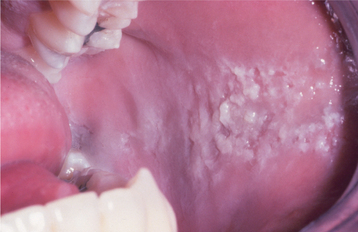

CLINICAL FEATURES: Most frequently, the lesions in patients with morsicatio are found bilaterally on the anterior buccal mucosa. They also may be unilateral, combined with lesions of the lips or the tongue, or isolated to the lips or tongue. Thickened, shredded, white areas may be combined with intervening zones of erythema, erosion, or focal traumatic ulceration (Figs. 8-2 and 8-3). The areas of white mucosa demonstrate an irregular ragged surface, and the patient may describe being able to remove shreds of white material from the involved area.

Fig. 8-2 Morsicatio buccarum. Thickened, shredded areas of white hyperkeratosis of the left buccal mucosa.

Fig. 8-3 Morsicatio linguarum. Thickened, rough areas of white hyperkeratosis of the lateral border of the tongue on the left side.

The altered mucosa typically is located in the midportion of the anterior buccal mucosa along the occlusal plane. Large lesions may extend some distance above or below the occlusal plane in patients whose habit involves pushing the cheek between the teeth with a finger.

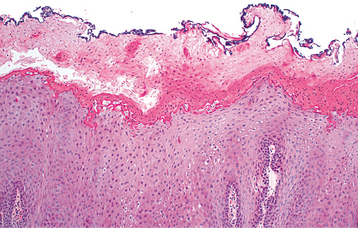

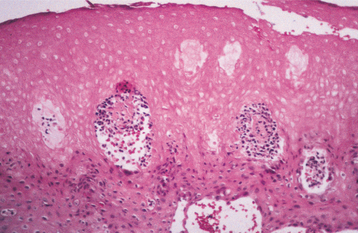

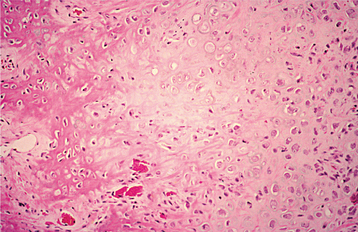

HISTOPATHOLOGIC FEATURES: Biopsy reveals extensive hyperparakeratosis that often results in an extremely ragged surface with numerous projections of keratin. Surface bacterial colonization is typical (Fig. 8-4). On occasion, clusters of vacuolated cells are present in the superficial portion of the prickle cell layer. This histopathologic pattern is not pathog-nomonic of morsicatio and may bear a striking resemblance to oral hairy leukoplakia (OHL), a lesion that most often occurs in people who are infected with the human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) (see page 268), or to uremic stomatitis (see page 851). A similar histopathologic pattern is noted in patients who chronically chew betel quid and has been termed betel chewer’s mucosa (see page 402). Similarities with linea alba and leukoedema also may be seen.

DIAGNOSIS: In most cases the clinical presentation of morsicatio buccarum is sufficient for a strong presumptive diagnosis, and clinicians familiar with these alterations rarely perform biopsy. Some cases of morsicatio may not be diagnostic from the clinical presentation, and biopsy may be necessary. In patients at high risk for HIV infection with isolated involvement of the lateral border of the tongue, further investigation is desirable to rule out HIV-associated OHL.

TREATMENT AND PROGNOSIS: No treatment of the oral lesions is required, and no long-term difficulties arise from the presence of the mucosal changes. For patients who desire treatment, an oral acrylic shield that covers the facial surfaces of the teeth may be constructed to eliminate the lesions by restricting access to the buccal and labial mucosa. For patients desiring either confirmation of the cause or preventive therapy, construction and use of two lateral acrylic shields connected by a labial stainless steel wire can provide quick resolution of the lesions while being acceptable aesthetically and not interfering with speech. Several authors also have suggested psychotherapy as the treatment of choice, but no extensive well-controlled studies have indicated benefits from this approach.

TRAUMATIC ULCERATIONS

Acute and chronic injuries of the oral mucosa are frequently observed. Injury can result from mechanical damage, such as contact with sharp foodstuffs or accidental biting during mastication, overzealous toothbrushing, talking, or even sleeping. Some are self-induced and clinically obvious, whereas others are subtle and difficult to diagnose. Damage also may result from thermal, electrical, or chemical burns. (Oral mucosal manifestations of such burns are discussed later in the chapter.)

Acute or chronic trauma to the oral mucosa may result in surface ulcerations. The ulcerations may remain for extended periods of time, but most usually heal within days. A histopathologically unique type of chronic traumatic ulceration of the oral mucosa is the eosinophilic ulceration (traumatic granuloma, traumatic ulcerative granuloma with stromal eosinophilia [TUGSE], eosinophilic granuloma of the tongue), which exhibits a deep pseudoinva-sive inflammatory reaction and is typically slow to resolve. Interestingly, many of these traumatic granulomas undergo resolution after incisional biopsy. Lesions microscopically similar to eosinophilic ulceration have been reproduced in rat tongues after repeated crushing trauma and in traumatic lesions noted in patients with familial dysautonomia, a disorder characterized by indifference to pain. In addition, similar sublingual ulcerations may occur in infants as a result of chronic mucosal trauma from adjacent anterior primary teeth, often associated with nursing. These distinctive ulcerations of infancy have been termed Riga-Fede disease and should be considered a variation of the traumatic eosinophilic ulceration.

In rare subsets of TUGSE, the lesion does not appear to be associated with trauma, and sheets of large, atypical cells are seen histopathologically. The nature of these atypical cells remains in dispute, although it has been suggested that they may represent reactive myofibroblasts, histiocytes (atypical histiocytic granuloma), or T lymphocytes. Whether these atypical eosinophilic ulcerations represent a single pathosis or a variety of disorders that share stromal eosinophilia is an area for future research. Of these theories, several current investigations have shown the atypical cells to be T lymphocytes with strong immunoperoxidase reactivity for CD30. In these cases, it is thought that this subset of TUGSE may represent the oral counterpart of the primary cutaneous CD30+ lymphoproliferative disorder, which also exhibits sequential ulceration, necrosis, and self-regression.

In most cases of traumatic ulceration, there is an adjacent source of irritation, although this is not present invariably. The clinical presentation often suggests the cause, but many cases resemble early ulcerative squamous cell carcinoma; biopsy is performed to rule out that possibility.

CLINICAL FEATURES: Most injuries are unintentional and arise from a variety of causes. As would be expected, simple chronic traumatic ulcerations occur most often on the tongue, lips, and buccal mucosa—sites that may be injured by the dentition (Fig. 8-5). Lesions of the gingiva, palate, and mucobuccal fold may occur from other sources of irritation. Overzealous toothbrushing can create linear erosions along the free gingival margins. Although these areas may superficially resemble a number of the chronic vesiculoerosive processes, thorough questioning of the patient often leads to the appropriate diagnosis. The individual lesions appear as areas of erythema surrounding a central removable, yellow fibrinopurulent membrane. In many instances, the lesion develops a rolled white border of hyperkeratosis immediately adjacent to the area of ulceration (Fig. 8-6).

Fig. 8-5 Traumatic ulceration. Well-circumscribed ulceration of the posterior buccal mucosa on the left side.

Fig. 8-6 Traumatic ulceration. Mucosal ulceration with a hyperkeratotic collar located on the ventral surface of the tongue.

Eosinophilic ulcerations are not uncommon but frequently are not reported. The lesions occur in peopleof all ages, with a significant male predominance. Most have been reported on the tongue, although cases have been seen on the gingiva, buccal mucosa, floor of mouth, palate, and lip. The lesion may last from 1 week to 8 months. The ulcerations appear very similar to the simple traumatic ulcerations; however, on occasion, underlying proliferative granulation tissue can result in a raised lesion similar to a pyogenic granuloma (see page 517) (Fig. 8-7).

Fig. 8-7 Traumatic granuloma. Exophytic ulcerated mass on the ventrolateral tongue associated with multiple jagged teeth.

Riga-Fede disease typically appears between 1 week and 1 year of age. The condition often develops in association with natal or neonatal teeth (see page 81). The anterior ventral surface of the tongue is the most common site of involvement, although the dorsal surface also may be affected (Fig. 8-8). Ventral lesions contact the adjacent mandibular anterior incisors; lesions on the dorsal surface are associated with the maxillary incisors. A presentation similar to Riga-Fede disease can be the initial finding in a variety of neuro logic conditions related to self-mutilation, such as familial dysautonomia (Riley-Day syndrome), congenital indifference to pain, Lesch-Nyhan syn-drome, Gaucher disease, cerebral palsy, or Tourette syndrome.

Fig. 8-8 Riga-Fede disease. Newborn with traumatic ulceration of anterior ventral surface of the tongue. Mucosal damage occurred from contact of tongue with adjacent tooth during breastfeeding.

The atypical eosinophilic ulceration occurs in older adults, with most cases developing in patients older than age 40. Surface ulceration is present, and an underlying tumefaction also is seen. The tongue is the most common site, although the gingiva, alveolar mucosa, mucobuccal fold, buccal mucosa, and lip may be affected (Fig. 8-9).

HISTOPATHOLOGIC FEATURES: Simple traumatic ulcerations are covered by a fibrinopurulent membrane that consists of fibrin intermixed with neutrophils. The membrane is of variable thickness, and the adjacent surface epithelium may be normal or may demonstrate slight hyperplasia with or without hyperkeratosis. The ulcer bed consists of granulation tissue that supports a mixed inflammatory infiltrate of lymphocytes, histiocytes, neutrophils, and, occasionally, plasma cells. In patients with eosinophilic ulcerations, the pattern is very similar; however, the inflammatory infiltrate extends into the deeper tissues and exhibits sheets of lymphocytes and histiocytes intermixed with eosinophils. In addition, the vascular connective tissue deep to the ulceration may become hyperplastic and cause surface elevation.

Atypical eosinophilic ulcerations exhibit numerous features of the traumatic eosinophilic ulceration, but the deeper tissues are replaced by a highly cellular proliferation of large lymphoreticular cells. The infiltrate is pleomorphic, and mitotic features are somewhat common. Intermixed with the large atypical cells are mature lymphocytes and numerous eosinophils. Although an associated immunohistochemical profile rarely has been reported, several investigators have shown the large cells to be T lymphocytes, the majority of which react with CD30 (Ki-1). In many instances, molecular studies for T-cell clonality by polymerase chain reaction (PCR) have been performed on the CD30+ cells and demonstrated monoclonal rearrangement. Whether this monoclonal infiltrate represents a true low-grade lymphoma or an unusual reactive lymphoproliferative process has not been determined.

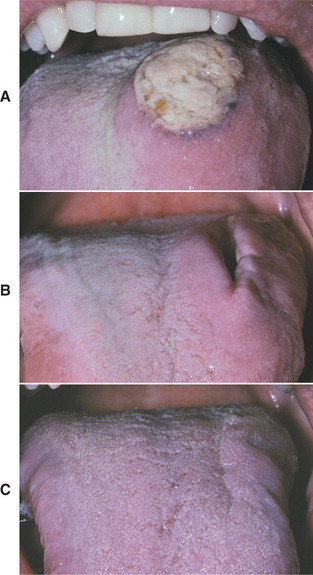

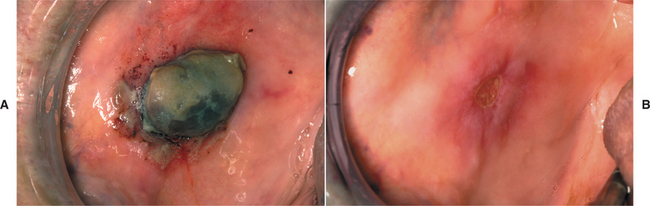

TREATMENT AND PROGNOSIS: For traumatic ulcerations that have an obvious source of injury, the irritating cause should be removed. Dyclonine HCl or hydroxypropyl cellulose films can be applied for temporary pain relief. If the cause is not obvious, or if a patient does not respond to therapy, then biopsy is indicated. Rapid healing after a biopsy is typical even with large eosinophilic ulcerations (Fig. 8-10). Recurrence is not expected.

Fig. 8-10 Eosinophilic ulceration. A, Initial presentation of a large ulceration of the dorsal surface of the tongue. B, Significant resolution noted 2 weeks after incisional biopsy. C, Subsequent healing noted 4 weeks after biopsy.

The use of corticosteroids in the management of traumatic ulcerations is controversial. Some clinicians have suggested that use of such medications may delay healing. In spite of this, other investigators have reported success using corticosteroids to treat chronic traumatic ulcerations.

Although extraction of the anterior primary teeth is not recommended, this procedure has resolved the ulcerations in Riga-Fede disease. The teeth should be retained if they are stable. Grinding the incisal mame-lons, coverage of the teeth with a light-cured composite or cellulose film, construction of a protective shield, or discontinuation of nursing have been tried with variable success.

In patients demonstrating histopathologic similarities to the cutaneous CD30+ lymphoproliferative disorder, a thorough evaluation for systemic lymphoma is mandatory, along with lifelong follow-up. Although recurrence frequently is seen, the ulcerations typically heal spontaneously, and the vast majority of patients do not demonstrate dissemination of the process. Further documentation is critical to define more fully this poorly understood process.

ELECTRICAL AND THERMAL BURNS

Electrical burns to the oral cavity are fairly common, constituting approximately 5% of all burn admissions to hospitals. Two types of electrical burns can be seen: (1) contact and (2) arc.

Contact burns require a good ground and involve electrical current passing through the body from the point of contact to the ground site. The electric current can cause cardiopulmonary arrest and may be fatal. Most electrical burns affecting the oral cavity are the arc type, in which the saliva acts as a conducting medium and an electrical arc flows between the electrical source and the mouth. Extreme heat, up to 3000° C, is possible with resultant significant tissue destruction. Most cases result from chewing on the female end of an extension cord or from biting through a live wire.

Most thermal burns of the oral cavity arise from ingestion of hot foods or beverages. Microwave ovens have been associated with an increased frequency of thermal burns because of their ability to cook food that is cool on the exterior but extremely hot in the interior.

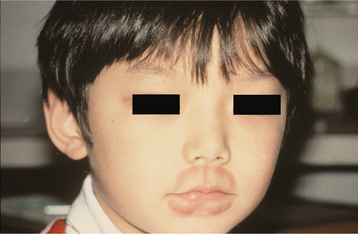

CLINICAL FEATURES: Most electrical burns occur in children younger than 4 years of age. The lips are affected most frequently, and the commissure commonly is involved. Initially, the burn appears as a painless, charred, yellow area that exhibits little to no bleeding (Fig. 8-11). Significant edema often develops within a few hours and may persist up to 12 days. Beginning on the fourth day, the affected area becomes necrotic and begins to slough. Bleeding may develop during this period from exposure of the underlying vital vasculature, and the presence of this complication should be monitored closely. The adjacent mucobuccal fold, the tongue, or both also may be involved. On occasion, adjacent teeth may become nonvital, with or without necrosis of the surrounding alveolar bone. Malformation of developing teeth also has been documented. In patients receiving high-voltage electrical injury, resultant facial nerve paralysis is infrequently reported and typically resolves over several weeks to months.

Fig. 8-11 Electrical burn. Yellow charred area of necrosis along the left oral commissure. (Courtesy of Dr. Patricia Hagen.)

The injuries related to thermal food burns usually appear on the palate or posterior buccal mucosa (Fig. 8-12). The lesions appear as zones of erythema and ulceration that often exhibit remnants of necrotic epithelium at the periphery. If hot beverages are swallowed, swelling of the upper airway can occur and lead to dyspnea, which may develop several hours after the injury.

TREATMENT AND PROGNOSIS: For patients with electrical burns of the oral cavity, tetanus immunization, if not current, is required. Most clinicians prescribe a prophylactic antibiotic, usually penicillin, to prevent secondary infection in severe cases. The primary problem with oral burns is contracture of the mouth opening during healing. Without intervention, significant microstomia can develop and may produce such restricted access to the mouth that hygiene and eating become impossible in severe cases. Extensive scarring and disfigurement are typical in untreated patients.

To prevent the disfigurement, a variety of microstomia prevention appliances can be used to eliminate or reduce the need for subsequent surgical reconstruction. Compliance is the most important consideration when choosing the most appropriate device. Tissue-supported appliances appear most effective for infants and young children; older, more cooperative patients usually benefit from tooth-supported devices. In most cases, splinting is maintained for 6 to 8 months to ensure proper scar maturation. Evaluation for possible surgical reconstruction is usually performed after a 1-year follow-up.

Most thermal burns are of little clinical consequence and resolve without treatment. When the upper airway is involved and associated with breathing difficulties, antibiotics and corticosteroids often are administered. In rare cases, swelling of the airway mandates intubation or tracheotomy to resolve the associated dyspnea. In these severe cases, oral intake of food often is discontinued temporarily with nutrition provided by a nasogastric tube.

CHEMICAL INJURIES OF THE ORAL MUCOSA

A large number of chemicals and drugs come into contact with the oral tissues. A percentage of these agents are caustic and can cause clinically significant damage.

Patients often can be their own worst enemies. The array of chemicals that have been placed within the mouth in an attempt to resolve oral problems is amazing. Aspirin, sodium perborate, hydrogen peroxide, gasoline, turpentine, rubbing alcohol, and battery acid are just a few of the more interesting examples.

Certain patients, typically children or those under psychiatric care, may hold medications within their mouths rather than swallow them. A surprising number of medications are potentially caustic when held in the mouth long enough. Aspirin, bisphosphonates, and two psychoactive drugs, chlorpromazine and promazine, are well-documented examples.

Topical medications for mouth pain can compound the problem. Mucosal damage has been documented from many of the topical medicaments sold as treatments for toothache or mouth sores. Products containing isopropyl alcohol, phenol, hydrogen peroxide, or eugenol have produced adverse reactions in patients. Over-the-counter tooth-whitening products also contain hydrogen peroxide or one of its precursors, carbamide peroxidase, which has been shown to create mucosal necrosis (Fig. 8-13).

Fig. 8-13 Mucosal burn from tooth-whitening strips. Sharply demarcated zone of epithelial necrosis on the maxillary facial gingiva, which developed from the use of tooth-whitening strips. Less severe involvement also is present on the mandibular gingiva.

Health care practitioners are responsible for the use of many caustic materials. Silver nitrate, formocresol, sodium hypochlorite, paraformaldehyde, chromic acid, trichloroacetic acid, dental cavity varnishes, and acid-etch materials all can cause patient injury. Education and use of the rubber dam have reduced the frequency of such injuries.

The improper use of aspirin, hydrogen peroxide, silver nitrate, phenol, and certain endodontic materials deserves further discussion because of their frequency of misuse, the severity of related damage, and the lack of adequate documentation of these materials as harmful agents.

ASPIRIN: Mucosal necrosis from aspirin being held in the mouth is not rare (Fig. 8-14). Aspirin is available not only in the well-known tablets but also as powder.

HYDROGEN PEROXIDE: Hydrogen peroxide became a popular intraoral medication for prevention of periodontitis in the late 1970s. Since that time, mucosal damage has been seen more frequently as a result of this application. Concentrations at 3% or greater are associated most often with adverse reactions. Epithelial necrosis has been noted with dilutions as low as 1%, and many over-the-counter oral medications exceed this concentration (Fig. 8-15).

SILVER NITRATE: Silver nitrate remains a popular treatment for aphthous ulcerations, because the chemical cautery brings about rapid pain relief by destroying nerve endings. In spite of this, its use should be strongly discouraged. In all cases the extent of mucosal damage is increased by its use. In some patients an abnormal reaction is seen, with resultant significant damage and enhanced pain. In one report, an application of a silver nitrate stick to a small aphthous ulceration led to a necrotic defect that exceeded 2 ×- 2 cm and had to be débrided surgically. In addition, rare reports have documented irreversible systemic argyria secondary to habitual intraoral use of topical silver nitrate after recommendation by a dentist (see page 315).

PHENOL: Phenol has occasionally been used in dentistry as a cavity-sterilizing agent and cauterizing material. It is extremely caustic, and judicious use is required. Over-the-counter agents advertised as “canker sore” treatments may contain low concentrations of phenol, often combined with high levels of alcohol. Extensive mucosal necrosis and (rarely) underlying bone loss have been seen in patients who placed this material (phenol concentration 0.5%) in attempts to resolve minor mucosal sore spots (Fig. 8-16).

Fig. 8-16 Phenol burn. Extensive epithelial necrosis of the mandibular alveolar mucosa on the left side. Damage resulted from placement of an over-the-counter, phenol-containing, antiseptic and anesthetic gel under a denture. (Courtesy of Dr. Dean K. White.)

A prescription therapy containing 50% sulfuric acid, 4% sulfonated phenol, and 24% sulfonated phenolic agents is being marketed heavily to dentists for treatment of aphthous ulcerations. Because extensive necrosis has been seen from use of medicaments containing 0.5% phenol, this product must be closely monitored and used with great care.

ENDODONTIC MATERIALS: Some endodontic materials are dangerous because of the possibility of soft tissue damage (Fig. 8-17) or their injection into hard tissue with resultant deep spread and necrosis. Because of the past difficulty of obtaining profound anesthesia in some patients undergoing root canal therapy, some clinicians have used arsenical paste or paraformaldehyde formulations to devitalize the inflamed pulp. Gingival and bone necrosis have been documented as a consequence of leakage of this material from the pulp chamber into the surrounding tissues. In addition, extrusion of filling material containing paraformaldehyde into the periapical tissues has led to significant difficulties, and its use should be discouraged. Sodium hypochlorite produces similar results when it leaks into the surrounding supporting tissues or is injected past the apex, leading some to suggest chlorhexidine as a safer irrigant. The following can reduce the chances of tissue damage:

CLINICAL FEATURES: The previously discussed caustic agents produce similar damage. With short exposure, the affected mucosa exhibits a superficial white, wrinkled appearance. As the duration of exposure increases, the necrosis proceeds and the affected epithelium becomes separated from the underlying tissue and can be desquamated easily. Removal of the necrotic epithelium reveals red, bleeding connective tissue that subsequently will be covered by a yellowish, fibrinopurulent membrane. Mucosa bound to bone is keratinized and more resistant to damage, whereas the nonkeratinized movable mucosa is destroyed more quickly. In addition to mucosal necrosis, significant tooth erosion has been seen in patients who chronically chew aspirin or hold the medication in their teeth as it dissolves.

The use of the rubber dam can dramatically reduce iatrogenic mucosal burns. When cotton rolls are used for moisture control during dental procedures, two problems may occur. On occasion, caustic materials can leak into the cotton roll and be held in place against the mucosa for an extended period, with mucosal injury resulting from the chemical absorbed by the cotton. In addition, oral mucosa can adhere to dry cotton rolls, and rapid removal of the rolls from the mouth often can cause stripping of the epithelium in the area. The latter pattern of mucosal injury has been termed cotton roll burn (cotton roll stomatitis) (Fig. 8-18).

Fig. 8-18 Cotton roll burn. Zone of white epithelial necrosis and erythema of the maxillary alveolar mucosa.

Caustic materials injected into bone during endodontic procedures can result in significant bone necrosis, pain, and perforation into soft tissue. Necrotic surface ulceration and edema with underlying areas of soft tissue necrosis may occur adjacent to the site of perforation.

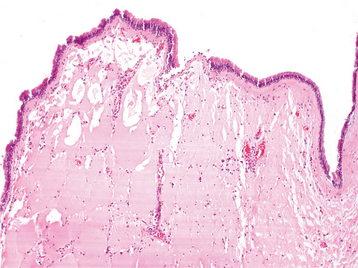

HISTOPATHOLOGIC FEATURES: Microscopic examination of the white slough removed from areas of mucosal chemical burns reveals coagulative necrosis of the epithelium, with only the outline of the individual epithelial cells and nuclei remaining (Fig. 8-19). The necrosis begins on the surface and moves basally. The amount of epithelium affected depends on the duration of contact and the concentration of the offending agent. The underlying connective tissue contains a mixture of acute and chronic inflammatory cells.

TREATMENT AND PROGNOSIS: The best treatment of chemical injuries is prevention of exposure of the oral mucosa to caustic materials. When using potentially caustic drugs (e.g., aspirin, chlorpromazine), the clinician must instruct the patient to swallow the medication and not allow it to remain in the oral cavity for any significant length of time. Children should not use chewable aspirin immediately before bedtime, and they should rinse after use.

Superficial areas of necrosis typically resolve completely without scarring within 10 to 14 days after discontinuation of the offending agent. For temporary protection, some clinicians have recommended coverage with a protective emollient paste or a hydroxypropyl cellulose film. Topical dyclonine HCl provides excellent but temporary pain relief. When large areas of necrosis are present, such as that related to the use of silver nitrate or accidental intrabony injection of offending materials, surgical débridement and antibiotic coverage often are required to promote healing and prevent spread of the necrosis.

NONINFECTIOUS ORAL COMPLICATIONS OF ANTINEOPLASTIC THERAPY

No systemic anticancer therapy currently available is able to destroy tumor cells without causing the death of at least some normal cells, and tissues with rapid turnover (e.g., oral epithelium) are especially susceptible. The mouth is a common site (and one of the most visible areas) for complications related to cancer therapy. Both radiation therapy and systemic chemotherapy may cause significant oral problems. The more potent the treatment, the greater the risk of complications. Each year almost 400,000 patients in the United States suffer acute or chronic oral side effects from anticancer treatments. With the advancement of medical practice, these complications are becoming more common as more patients have longer survival times and as intense therapies, such as bone marrow transplantation, become more commonplace. Oral complications are noted almost uniformly in patients receiving head and neck radiation, and close to 75% of bone marrow transplant patients are affected. The prevalence of chemotherapy-associated oral complications varies from 10% to 75%, depending on the type of associated cancer and the form of chemotherapy used.

CLINICAL FEATURES: A variety of noninfectious oral complications are seen regularly as a result of both radiation and chemotherapy. Two acute changes, mucositis and hemorrhage, are the predominant problems associated with chemotherapy, especially in cancers, such as leukemia, that involve high treatment doses.

Painful acute mucositis and dermatitis are the most frequently encountered side effects of radiation, but several chronic alterations continue to plague patients long after their courses of therapy are completed. Depending on the fields of radiation, the radiation dose, and the age of the patient, the following outcomes are possible:

HEMORRHAGE: Intraoral hemorrhage is typically secondary to thrombocytopenia, which develops from bone marrow suppression. Intestinal or hepatic damage, however, may cause lower vitamin K–dependent clotting factors, with resultant increased coagulation times. Conversely, tissue damage related to therapy may cause release of tissue thromboplastin at levels capable of producing potentially devastating disseminated intravascular coagulation (DIC). Oral petechiae and ecchymosis secondary to minor trauma are the most common presentations. Any mucosal site may be affected, but the labial mucosa, tongue, and gingiva are involved most frequently.

MUCOSITIS: Recent research suggests that mucosal damage secondary to cancer therapy is much more complex than previously thought and appears to arise from an extended series of molecular and cellular events that take place not only in the epithelium but also in the underlying stroma. Genetic differences in the rate of tissue apop tosis, microvascular injury from endothelial apoptosis, and increased peripheral blood levels of tumor necrosis factor a and interleukin-6 appear to be involved. Beyond the direct effects of the antineoplastic agent, additional risk factors include young age, female sex, poor oral hygiene, oral foci of infection, poor nutrition, impaired salivary function, tobacco use, and alcohol consumption.

Cases of oral mucositis related to radiation or chemotherapy are similar in their clinical presentations. The manifestations of chemotherapy develop after a few days of treatment; radiation mucositis may begin to appear during the second week of therapy. Both chemotherapy and radiation-induced mucositis will resolve slowly 2 to 3 weeks after cessation of treatment. Oral mucositis associated with chemotherapy typically involves the nonkeratinized surfaces (i.e., buccal mucosa, ventrolateral tongue, soft palate, floor of the mouth), whereas radiation therapy primarily affects the mucosal surfaces within the direct portals of radiation.

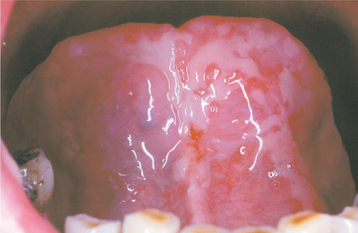

The earliest manifestation is development of a whitish discoloration from a lack of sufficient desquamation of keratin. This is soon followed by loss of this layer with replacement by atrophic mucosa, which is edematous, erythematous, and friable. Subsequently, areas of ulceration develop with formation of a removable yellowish, fibrinopurulent surface membrane (Figs. 8-20 to 8-22). Pain, burning, and discomfort are significant and can be worsened by eating and oral hygiene procedures.

Fig. 8-20 Chemotherapy-related epithelial necrosis. Vermilion border of the lower lip exhibiting epithelial necrosis and ulceration in a patient receiving systemic chemotherapy.

Fig. 8-21 Chemotherapy-related epithelial necrosis. Large, irregular area of epithelial necrosis and ulceration of the anterior ventral surface of the tongue in a patient receiving systemic chemotherapy.

Fig. 8-22 Radiation mucositis. A, Squamous cell carcinoma before radiation therapy. Granular erythroplakia of the floor of the mouth on the patient’s right side. B, Same lesion after initiation of radiation therapy. Note the large, irregular area of epithelial necrosis and ulceration of the anterior floor of the mouth on the patient’s right side. C, Normal oral mucosa after radiation therapy. Note resolution of the tumor and the radiation mucositis.

DERMATITIS: Acute dermatitis of the skin in the fields of radiation is common and varies according to the intensity of the therapy. Patients with mild radiation dermatitis experience erythema, edema, burning, and pruritus. This condition resolves in 2 to 3 weeks after therapy and is replaced by hyperpigmentation and variable hair loss. Moderate radiation causes erythema and edema in combination with erosions and ulcerations. Within 3 months these alterations resolve, and permanent hair loss, hyperpigmentation, and scarring may ensue. Necrosis and deep ulcerations can occur in severe acute reactions. Radiation dermatitis also may become chronic and be characterized by dry, smooth, shiny, atrophic, necrotic, telangiectatic, depilated, or ulcerated areas.

XEROSTOMIA: Salivary glands are very sensitive to radiation, and xerostomia is a common complication. When a portion of the salivary glands is included in the fields of radiation, the remaining glands undergo compensatory hyperplasia in an attempt to maintain function. The changes begin within 1 week of initiation of radiation therapy, with a dramatic decrease in salivary flow noted during the first 6 weeks of treatment. Even further decreases may be noted for up to 3 years.

Serous glands exhibit an increased radiosensitivity when compared with the mucous glands. On significant exposure, the parotid glands are affected dramatically and irreversibly. In contrast, the mucous glands partially recover and, over several months, may achieve flow that approaches 50% of preradiation levels. Symptomatic dry mouth appears most strongly associated with a decrease in palatal mucous secretions, with the loss of parotid serous secretion exerting a less noticeable effect. In addition to the discomfort of a mouth that lacks proper lubrication, diminished flow of saliva leads to a significant decrease of the bactericidal action and self-cleansing properties of saliva.

Without intervention, patients often develop symptomatic dry mouth that affects their ability to eat comfortably, wear dentures, speak, and sleep. In addition, there often is an increase in the caries index (xerostomia-related caries), regardless of the patient’s past caries history (Fig. 8-23). The decay is predominantly cervical in location and secondary to xerostomia (not a direct effect of the radiation).

LOSS OF TASTE: In patients who receive significant radiation to the oral cavity, a substantial loss of all four tastes (hypogeusia) often develops within several weeks. Although these tastes return within 4 months for most patients, some patients are left with permanent hypogeusia; others may have persistent dysgeusia (altered sense of taste) (see page 875).

OSTEORADIONECROSIS: Osteoradionecrosis is one of the most serious complications of radiation to the head and neck; however, it is seen less frequently today because of better treatment modalities and prevention. The current prevalence rate is approximately 5%, whereas the frequency approached 15% less than 20 years ago. Although the risk is low, it increases dramatically if a local surgical procedure is performed within 21 days of therapy initiation or within 12 months after therapy.

In the past, many researchers believed that radiation induced an osseous endarteritis that led to tissue hypoxia, hypocellularity, and hypovascularity and created a predisposition to necrosis if a minor injury occurred. This theory led to widespread use of hyperbaric oxygen in the prevention and treatment of this pathosis. However, many now believe the process is more complex and may involve radiation damage to osseous cells; when these cells lose normal function, bone turnover is suppressed in a manner similar to the effect on osteoclasts associated with use of bisphosphonates (see page 299). Researchers believe that damage to these cells not only disrupts their primary function but also affects bone vascularity through a complex interaction of cytokines and growth factors.

Previously, investigators suggested that radiation-associated reduction in healing capacity might be permanent, with the risk for osteonecrosis remaining high for many years. Currently, others have proposed that repair of damaged osseous cells occurs as they are replaced by future cellular generations. Investigations have suggested that significant recovery does occur, and the prevalence of osteonecrosis is reduced significantly after a 1-year recovery period, with or without use of hyperbaric oxygen. More recent clinical trials of irradiated patients have shown a low prevalence of osteonecrosis if a period of postradiation healing (1 year or longer) is combined with atraumatic surgical technique.

Although most instances of osteoradionecrosis arise secondary to local trauma, a minority appear sponta-neous. The mandible is involved most frequently, although a few cases have involved the maxilla (Fig. 8-24). Affected areas of bone reveal ill-defined areas of radiolucency that may develop zones of relative radiopacity as the dead bone separates from the residual vital areas (Fig. 8-25). Intractable pain, cortical perforation, fistula formation, surface ulceration, and pathologic fracture may be present (Fig. 8-26).

Fig. 8-24 Osteoradionecrosis. Ulceration overlying left body of the mandible with exposure and sequestration of superficial alveolar bone.

Fig. 8-25 Osteoradionecrosis. Multiple ill-defined areas of radiolucency and radiopacity of the mandibular body.

Fig. 8-26 Osteoradionecrosis. Same patient as depicted in Fig. 8-24. Note fistula formation of the left submandibular area resulting from osteoradionecrosis of the mandibular body.

The radiation dose is the main factor associated with bone necrosis, although the proximity of the tumor to bone, the presence of remaining dentition, and the type of treatment also exert an effect. Additional factors associated with an increased prevalence include older age, male sex, poor health or nutritional status, and continued use of tobacco or alcohol.

Prevention of bone necrosis is the best course of action. Before therapy, all questionable teeth should be extracted or restored, and oral foci of infection should be eliminated; excellent oral hygiene should be initiated and maintained. A healing time of at least 3 weeks between extensive dental procedures and the initiation of radiotherapy significantly decreases the chance of bone necrosis. Extraction of teeth or any bone trauma is strongly contraindicated during radiation therapy.

TRISMUS: Trismus may develop and can produce extensive difficulties concerning access for hygiene and dental treatment. Tonic muscle spasms with or without fibrosis of the muscles of mastication and the temporomandibular joint (TMJ) capsule can cause difficulties in jaw opening. When these structures are radiated heavily, jaw-opening exercises may help to decrease or prevent problems.

DEVELOPMENTAL ABNORMALITIES: Antineoplastic therapy during childhood can affect growth and development. The changes vary according to the age at treatment and the type and severity of therapy. Radiation can alter the facial bones and result in micrognathia, retrognathia, or malocclusion. Developing teeth are very sensitive and can exhibit a number of changes, such as root dwarfism, blunting of roots, dilaceration of roots, incomplete calcification, premature closure of pulp canals in deciduous teeth, enlarged canals in permanent teeth, microdontia, and hypodontia (see page 58).

TREATMENT AND PROGNOSIS: Optimal treatment planning involves the oral health practitioner before initiation of antineoplastic therapy. Elimination of all current or potential oral foci of infection is paramount, along with patient education about maintaining ultimate oral hygiene. Proper nutrition, cessation of tobacco use, and alcohol abstinence will minimize oral complications. Once cancer therapy is initiated, efforts must be directed toward relieving pain, preventing dehydration, maintaining adequate nutrition, eliminating foci of infection, and ensuring continued appropriate oral hygiene.

MUCOSITIS: In an attempt to decrease the severity, duration, and symptoms associated with oral mucositis, a large number of treatments such as anesthetic, analgesic, antimicrobial, and coating agents have been tried with mixed reviews. Few have been proven to be consistently beneficial in well-designed placebo-controlled trials. A low-cost salt and soda rinse often has demonstrated similar effectiveness and a lower adverse reaction profile when compared with many other interventions. When all treatments fail, the degree of mucositis and associated pain may mandate systemic morphine therapy.

Cryotherapy (placement of ice chips in the mouth 5 minutes before chemotherapy and continued for 30 minutes) has been shown to reduce significantly the prevalence and severity of oral mucositis secondary to bolus injection of chemotherapeutic drugs with a short half-life, such as 5-fluorouracil or edatrexate. Although limited by the hardware expense and necessity for specialized training, low-level helium-neon laser therapy also appears to reduce the frequency and severity of chemotherapy-associated mucositis.

A new avenue of research is concentrating on growth factors that may affect the prevalence of oral mucositis. Recently, intravenous (IV) recombinant human keratinocyte growth factor (palifermin) became the first compound approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for reduction of oral mucositis related to myelotoxic chemotherapy. In clinical studies, this expensive biologic response modifier provided a modest, but statistically significant, reduction in the severity of mucositis, severity of oral pain, use of narcotic analgesia, and need for total parenteral nutrition.

One of the more effective mechanisms to reduce radiation-associated mucositis has been placement of midline radiation blocks or use of three-dimensional radiation treatment to limit the volume of irradiated mucosa. Although not approved in the United States but available in Canada and Europe, topical benzydamine reduces the frequency, severity, and pain of radiation-associated oral mucositis. This unique nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drug (NSAID) also exhibits analgesic, anesthetic, and antimicrobial properties.

XEROSTOMIA: Xerostomic patients should be counseled to avoid all agents that may decrease salivation, especially the use of tobacco products and alcohol. To combat xerostomia-related caries, a regimen of daily topical fluoride application should be instituted.

The problem of chronic xerostomia has been approached through the use of salivary substitutes and sialagogues. Because the mucous glands often demonstrate significant recovery after radiation, the sialagogues show promise because they stimulate the residual functional glands. Moisturizing gels, sugarless candies, and chewing gum are used, but the most efficacious product in controlled clinical studies has been systemic use of one of the cholinergic drugs, pilocarpine or cevimeline. Although these drugs may be beneficial for many patients, they are contraindicated in patients with asthma, gastrointestinal ulcerations, labile hypertension, glaucoma, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, and significant cardiovascular disease. Adverse reactions are uncommon but include excess sweating, rhinitis, headache, nausea, uropoiesis, flatulence, and circulatory disorders.

Other systemic salivary stimulants that are associated with a less dramatic influence on flow include bethanechol and anetholetrithione. Anetholetrithione appears to act by increasing the number of salivary gland receptors. Although somewhat effective when used alone, this medication has been combined with one of the cholinergic medications and achieved improvement in patients who failed to respond to the use of a single agent.

LOSS OF TASTE: Although the taste buds often regenerate within 4 months after radiation therapy, the degree of long-term impairment is highly variable. In those with continu-ing symptoms, zinc sulfate supplements greater than the usual recommended daily doses appear to be beneficial.

OSTEORADIONECROSIS: Although prevention must be stressed, cases of osteoradionecrosis do occur. Use of hyperbaric oxygen has numerous contraindications and possible adverse reactions. Because of the newer theories of pathogenesis for osteoradionecrosis, many clinicians are less inclined to use hyperbaric oxygen except in selected cases. Therapy consists of antibiotics, débridement, irrigation, and removal of diseased bone. The amount of bone removed is determined by clinical judgment, with the surgery extended until brightly bleeding edges are seen.

BISPHOSPHONATE-ASSOCIATED OSTEONECROSIS

The initial association between use of bisphosphonates and subsequent development of gnathic osteonecrosis was documented in 2003. Bisphosphonates comprise a unique class of medications that has been shown to inhibit osteoclasts and possibly interfere with angiogenesis through actions such as inhibition of vascular endothelial growth factor. These medications can be delivered by mouth (PO) or intravenously (IV) and are used primarily to slow osseous involvement of a number of cancers (multiple myeloma and metastatic breast or prostate carcinoma), to treat Paget’s disease (see page 623), and to reverse osteoporosis.

The first-generation bisphosphonates have a relatively low potency and are readily metabolized by osteoclasts. Addition of a nitrogen side chain was added subsequently, creating a more potent second generation of these drugs, designated aminobisphosphonates (Box 8-1). In contrast to the first generation, these formulations are incorporated into the skeleton and demonstrate an extended half-life (e.g., estimated to be 12 years for alendronate). Currently, strong association with gnathic osteonecrosis has been limited to the aminobisphosphonates.

Although bone may seem to be a stable tissue, it constantly is undergoing a process of resorption and reapposition throughout life. The typical lifespan of an osteoblast/osteocyte is approximately 150 days. Osteoclasts also play a critical role in the maintenance of normal bone by repairing microfractures and resorbing areas of bone that contain foci of older nonvital osteocytes. On resorption of bone, cytokines and growth factors such as bone morphogenetic protein are released and induce formation of active bone-forming osteoblasts. If osteoclastic function declines, then microfractures accumulate and the lifespan of the entrapped osteocytes is exceeded, creating areas of vulnerable bone. When osteoclasts ingest bisphos-phonate-treated bone, the medication is cytotoxic and induces osteoclastic apoptosis, a reduction in recruitment of additional osteoclasts, and a stimulation of osteoblasts to release an osteoclast-inhibiting factor. The incorporation of the medication is highest in areas of active remodeling, such as the jaws. Although the vast majority of osteonecrosis cases have occurred in the jaws, extragnathic involvement has been documented (e.g., osteonecrosis of ear after removal of exostosis of the external ear canal).

CLINICAL AND RADIOGRAPHIC FEATURES: In an excellent systematic review of 368 reported cases of bisphosphonate-associated osteonecrosis (BON), 94% were discovered in patients who were treated with the IV formulations (primarily pamidronate and zoledronic acid) for cancer, with 85% being reported in patients with multiple myeloma. Current estimates indicate that the prevalence of osteonecrosis in patients taking aminobisphosphonates for cancer is 6% to 10%. Prospective trials will be necessary to confirm these figures.

Osteonecrosis related to use of oral aminobisphosphonates is most uncommon (conservative estimate by drug industry: annual incidence is 0.7 per 100,000); however, prospective trials for the true incidence of this complication have yet to be performed. Risk factors for BON associated with the PO formulations include advanced patient age (older than 65 years), corticosteroid use, use of chemotherapy drugs, diabetes, smoking or alcohol use, poor oral hygiene, and duration of drug use exceeding 3 years. A predictive test for those at risk for bisphosphonate osteonecrosis has not been confirmed. Some investigators recently have suggested use of a serum marker for bone turnover, serum C-telopeptide (CTX), but additional prospective studies are needed to confirm the utility of this test.

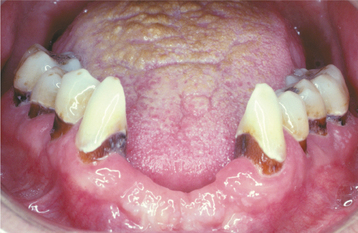

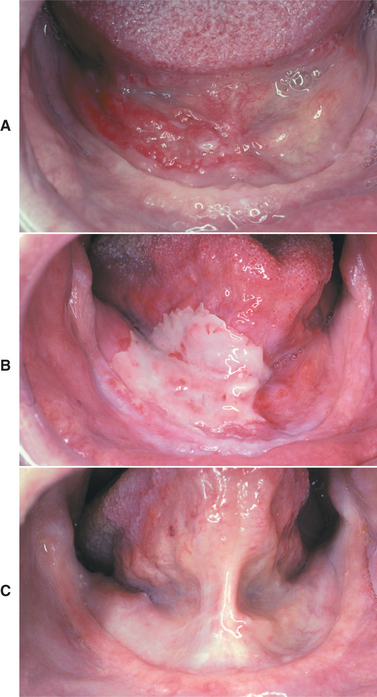

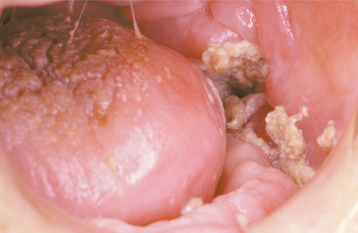

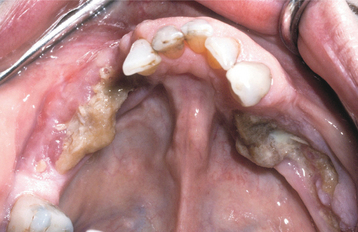

Although a mandibular predominance has been noted, involvement of the maxilla or both jaws is not uncommon (Fig. 8-27). In 60% of these patients, the necrosis has followed an invasive dental procedure, with the remainder occurring spontaneously (Fig. 8-28). On occasion, the necrosis can occur after minor trauma to bony prominences, such as tori or other exostoses (Fig. 8-29). Affected patients have areas of exposed, necrotic bone that is asymptomatic in approximately one third.

Fig. 8-27 Bisphosphonate-associated osteonecrosis. Bilateral necrotic exposed bone of the mandible in a patient receiving zoledronic acid for metastatic breast cancer. (Courtesy of Dr. Brent Mortenson.)

Fig. 8-28 Bisphosphonate-associated osteonecrosis. Extensive necrosis of the mandible, which followed extraction of multiple teeth. The patient was receiving zoledronic acid for metastatic breast cancer. (Courtesy of Dr. Benny Bell.)

Fig. 8-29 Bisphosphonate-associated osteonecrosis. Lobulated palatal torus with an area of exposed necrotic bone in a patient taking alendronate for osteoporosis.

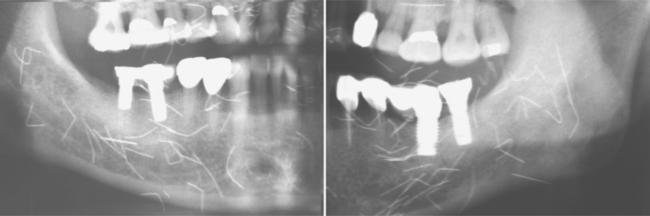

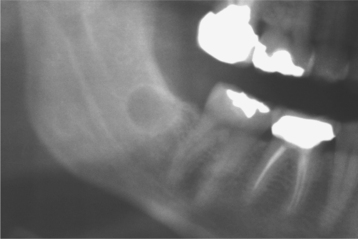

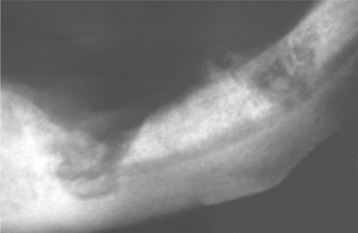

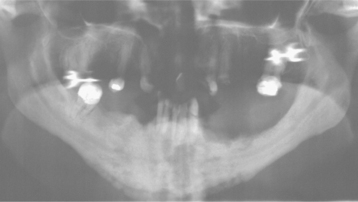

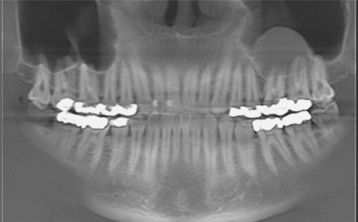

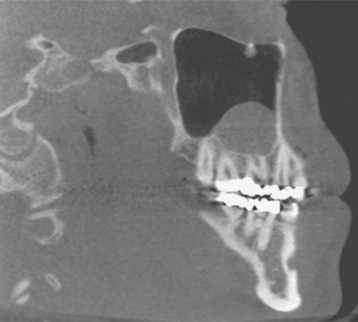

Investigators have suggested that bone at imminent risk for osteonecrosis often will demonstrate increased radiopacity before clinical evidence of frank necrosis. These changes typically occur predominantly in areas of high bone remodeling, such as the alveolar ridges. Panoramic radiographs often will reveal a marked radiodensity of the crestal portions of each jaw, with a more normal appearance of the bone away from tooth-bearing portions. Periosteal hyperplasia also is not rare. In more severe cases, the osteonecrosis creates a moth-eaten and ill-defined radiolucency with or without central radiopaque sequestra (Fig. 8-30). In some cases the necrosis can lead to development of a cutaneous sinus or pathologic fracture (Fig. 8-31).

Fig. 8-30 Bisphosphonate-associated osteonecrosis. Panoramic radiograph of patient depicted in Fig. 8-27. Note sclerosis of tooth-bearing areas along with multiple radiolucencies and periosteal hyperplasia of the lower border of the mandible. (Courtesy of Dr. Brent Mortenson.)

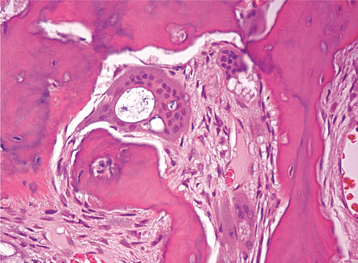

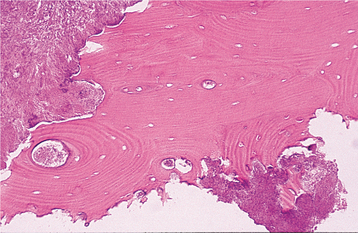

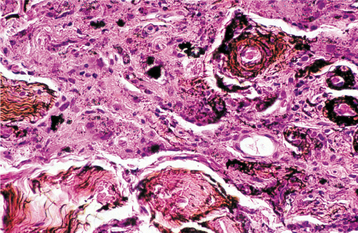

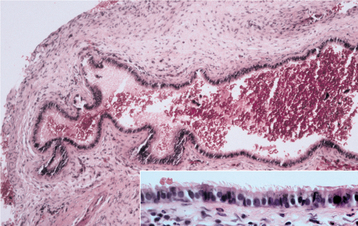

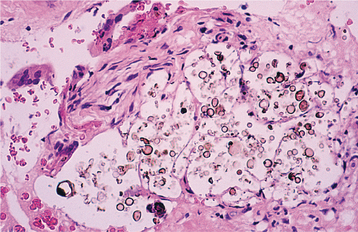

HISTOPATHOLOGIC FEATURES: Biopsy of vital bone altered by aminobisphosphonates is not common. In such cases the specimen often reveals irregular trabeculae of pagetoid bone, with adjacent enlarged and irregular osteoclasts that often demonstrate numerous intracytoplasmic vacuoles (Fig. 8-32). Specimens of active areas of BON reveal trabeculae of sclerotic lamellar bone, which demonstrate loss of the osteocytes from their lacunae and frequent peripheral resorption with bacterial colonization (Fig. 8-33). Although the peripheral bacterial colonies often resemble actinomycetes, the infestation is not consistent with cervicofacial actinomycosis.

TREATMENT AND PROGNOSIS: The clinical approach to patients treated with aminobisphosphonates varies according to the formulation of the drug, the disease being treated, and the duration of drug use. All patients who take these medications should be warned of the risks and instructed to obtain and maintain ultimate oral hygiene. The oral medications are extremely caustic; patients should be warned to minimize oral mucosal contact and ensure the medication is swallowed completely.

Routine dental therapy, in most cases, should not be modified solely on the basis of oral aminobisphosphonate use. All restorative, prosthodontic, conventional endodontic, and routine periodontic procedures can be implemented as needed. Although orthodontic treatment is not contraindicated, progress should be evaluated after 2 to 3 months of active therapy. At that point, therapy can proceed if the tooth movement is occurring predictably with normal forces. Invasive orthodontic techniques such as orthognathic surgery, four-tooth extraction cases, and miniscrew anchorage should be avoided, if possible. Because the medica-tion is drawn to sites of active bone remodeling, a drug holiday (or switching to a nonaminobisphosph-onate agent) during active orthodontics may be advantageous.

When manipulation of bone is considered (e.g., surgical endodontics, periodontal bone recontouring, oral surgery, implant placement), the patient should be advised of the potential complications of aminobisphosphonate use and the risk of BON. Written informed consent and documentation of a discussion of the benefits, risks, and alternative therapies are highly advised. For elective surgical procedures in patients with a duration of drug use exceeding 3 years, discontinuation of the medication 3 months before and 3 months after surgery has been suggested. Because of the reduced angiogenesis, osseous grafts should be used judiciously. If multiple sites require surgery, then one sextant should be treated with a 2-month disease-free follow-up before completion of the remaining sextants. During this interval, use of chlorhexidine twice daily is recommended. The sextant-by-sextant approach is not necessary for periapical inflammatory disease or abscesses, both of which can lead directly to osteonecrosis and demand immediate resolution.

Dental therapy in patients taking an IV formulation for cancer is much more problematic. Prevention is paramount. In patients evaluated before initiation of an IV aminobisphosphonate, the goal is to eliminate all dental infections and improve dental health to prevent future invasive therapy; this includes removal of large tori or partially impacted teeth. If only noninvasive therapy is necessary, then the initiation of the medication need not be delayed. If surgical procedures are performed, then a month-long delay in initiation of the medication is recommended, along with prophylactic antibiotic therapy (i.e., penicillin; quinolone and metronidazole, or erythromycin and metronidazole for those allergic to penicillin).

For patients presenting in the midst of active IV therapy, a number of clinicians have suggested that manipulation of bone should be avoided. Conventional endodontics is a better option than extraction. If a nonvital tooth is not restorable, then endodontics should be performed and followed by crown amputation. Teeth with 1+ or 2+ mobility should be splinted; those with 3+ mobility can be extracted.

For patients with BON, the goal of therapy is to stop pain. A number of clinicians believe that removal of bone typically results in further bone necrosis, and hyperbaric oxygen has not been beneficial. Asymptomatic patients should rinse daily with chlorhexidine and be monitored closely. Any rough edges of exposed bone should be smoothed. If the exposed bone irritates adjacent tissues, then coverage with a soft splint may prove beneficial. In symptomatic patients, systemic antibiotic therapy (i.e., penicillin with or without metronidazole, ciprofloxacin or erythromycin and metronidazole for those allergic to penicillin) and chlorhexidine usually lead to pain relief. If the antibiotics fail to stop the pain, then hospitalization with IV therapy is indicated. In recalcitrant cases the bulk of the dead bone is reduced surgically, followed by administration of systemic antibiotics. Because of the long half-life of bisphosphonates, discontinuation of the drug offers no short-term benefit. In isolated anecdotal reports of recalcitrant cases, discontinuation of the medication for 6 to 12 months occasionally has been associated with spontaneous sequestration and resolution.

As mentioned in the discussion of the radiographic features, the alveolar ridges of patients affected with osteonecrosis exhibit significant sclerosis because of increased drug deposition in areas of high remodeling. Some investigators have successfully treated patients with BON by resection of all of the osteosclerotic areas with extension to the underlying more lucent and normally bleeding bone. As adjunctive therapy to enhance healing, the osseous defect can be covered with a resorbable collagen membrane impregnated with platelet-rich plasma.

Overall, the benefits of aminobisphosphonate therapy for osteoporosis and metastatic cancer appear to greatly outweigh the risk of developing BON. However, the oral medications should be prescribed only for those individuals with inadequate bone density and should be discontinued or switched to a nonaminobisphosphonate once the bone density returns to an acceptable level.

Increased bone density does not correlate necessarily to good bone quality. The negative effects of oversuppression of bone metabolism must be considered in all patients prescribed oral aminobisphosphonates. Several reports have documented spontaneous nontraumatic stress fractures with associated delayed healing in patients on long-term aminobisphosphonate therapy. Many physicians now believe that aminobisphosphonate therapy should be stopped after 5 years and not reinitiated until bone density studies confirm redevelopment of significant osteoporosis.

Dentists should be proactive and strongly encour-age patients to speak to their attending physicians for consideration of these factors during planning and execution of long-term care. For individuals scheduled to receive IV aminobisphosphonate therapy as part of their cancer management, the involved oncologist should recommend pretreatment dental evaluation and preventive care, with long-term, close follow-up.

OROFACIAL COMPLICATIONS OF METHAMPHETAMINE ABUSE

Methamphetamine (“meth”) is a drug with stimulant effects on the central nervous system (CNS). In 1937 the drug was approved in the United States for the treatment of narcolepsy and attention deficit hyperactivity disorder. Within a few years, many began to use the drug to increase alertness, control weight, and combat depression. Because methamphetamine users perceive increased physical ability, greater energy, and euphoria, illegal use and manufacture of the drug began to develop. Because of greater control over the main ingredient, pseudoephedrine, production of homemade methamphetamine is decreasing but often being replaced by illegal importation of the finished product. The drug is a powdered crystal that dissolves easily in liquid and can be smoked, snorted, injected, or taken orally. The drug is known by nicknames that include chalk, crank, crystal, fire, glass, ice, meth, and speed.

CLINICAL FEATURES: Although methamphetamine abuse may occur throughout society, most users are men between the ages of 19 and 40 years. The effects of the medication last up to 12 hours, and the typical abuser reports use that exceeds 20 days per month, creating an almost continuous effect of the drug. The short-term effects of methamphetamine include insomnia, aggressiveness, agitation, hyperactivity, decreased appetite, tachycardia, tachypnea, hypertension, hyperthermia, vomiting, tremors, and xerostomia. Long-term effects additionally include strong psychologic addiction, violent behavior, anxiety, confusion, depression, paranoia, auditory hallucinations, delusions, mood changes, skin lesions, and a number of cardiovascular, CNS, hepatic, gastrointestinal, renal, and pulmonary disorders.

Many addicts develop delusions of parasitosis (formication, from the Latin word formica, which translates to ant), a neurosis that produces the sensation of snakes or insects crawling on or under the skin. This sensation causes the patient to attempt to remove the perceived parasites, usually by picking at the skin with fingernails, resulting in widespread traumatic injury. The factitial damage can alter dramatically the facial appearance in a short period of time, and these lesions have been nicknamed speed bumps, meth sores, or crank bugs.

Rampant dental caries is another common manifestation and exhibits numerous similarities with milk-bottle caries. The carious destruction initially affects the facial smooth and interproximal surfaces, but without intervention, the coronal structure of the entire dentition can be destroyed (Fig. 8-34). The carious destruction appears to be caused by poor oral hygiene combined with extreme drug-related xerostomia, which leads to heavy consumption of acidic and sugar-filled soft drinks or other refined carbohydrates.

TREATMENT AND PROGNOSIS: The oral health practitioner should be alerted when an emaciated, agitated, and nervous young adult presents with tachycardia, tachypnea, hypertension, hyperthermia, and rampant smooth surface and interproximal caries. Failure to recognize these signs can be serious. For up to 6 hours after ingestion, methamphetamine potentiates the effects of sympathomimetic amines. Use of local anesthetics with epinephrine or levonordefrin can lead to a hypertensive crisis, cerebral vascular accident, or myocardial infarction. Caution also should be exercised when administering sedatives, general anesthesia, nitrous oxide, or prescriptions for narcotics. Although cessation of the illicit drug use is paramount, patients should be encouraged during periods of xerostomia to discontinue use of highly acidic and sugar-filled soft drinks and to avoid diuretics such as caffeine, tobacco, and alcohol. In addition, the importance of personal and oral hygiene should be stressed. Preventive measures such as topical fluorides may assist in protecting the remaining dentition. A medical consultation with referral to a substance abuse center should be encouraged.

ANESTHETIC NECROSIS

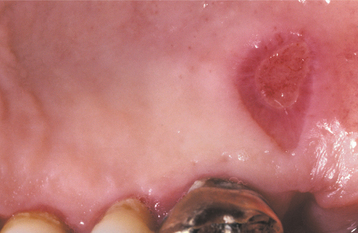

Administration of a local anesthetic agent can, on rare occasions, be followed by ulceration and necrosis at the site of injection. Researchers believe that this necrosis results from localized ischemia, although the exact cause is unknown and may vary from case to case. Faulty technique, such as subperiosteal injection or administration of excess solution in tissue firmly bound to bone, has been blamed. The epinephrine contained in many local anesthetics also has received attention as a possible cause of ischemia and secondary necrosis.

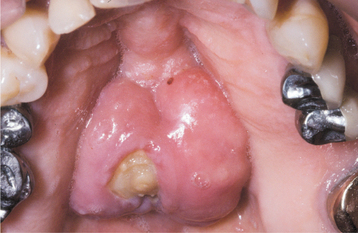

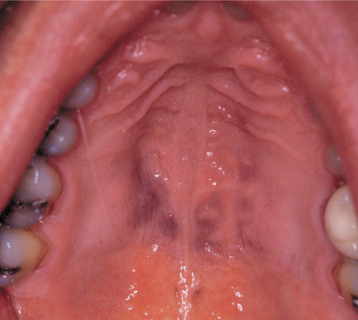

CLINICAL FEATURES: Anesthetic necrosis usually develops several days after the procedure and most commonly appears on the hard palate (Fig. 8-35). A well-circumscribed area of ulceration develops at the site of injection. The ulceration often is deep, and, on occasion, healing may be delayed. One report has documented sequestration of bone at the site of tissue necrosis.

TREATMENT AND PROGNOSIS: Treatment of anesthetic necrosis usually is not required unless the ulceration fails to heal. Minor trauma, such as that caused by performing a cytologic smear, has been reported to induce resolution in these chronic cases. Recurrence is unusual but has been reported in some patients in association with use of epinephrine-containing anesthetics. In these cases the use of a local anesthetic without epinephrine is recommended.

EXFOLIATIVE CHEILITIS

Exfoliative cheilitis is a persistent scaling and flaking of the vermilion border, usually involving both lips. The process arises from excessive production and subsequent desquamation of superficial keratin. A significant percentage of cases appears related to chronic injury secondary to habits such as lip licking, biting, picking, or sucking. Those cases proven to arise from chronic injury are termed factitious cheilitis.

Many patients deny chronic self-irritation of the area. The patient may be experiencing associated personality disturbances, psychologic difficulties, or stress. In a review of 48 patients with exfoliative cheilitis, 87% exhibited psychiatric conditions and 47% also demonstrated abnormal thyroid function. Evidence suggests that there may be a link between thyroid dysfunction and some psychiatric disturbances.

In other cases, no evidence of chronic injury is evident. In these patients other causes should be ruled out (e.g., atopy, chronic candidal infection, actinic cheilitis, cheilitis glandularis, hypervitaminosis A, photosensitivity). In a review of 165 patients with acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS), more than one quarter had alterations that resembled exfoliative cheilitis. In this group the lip alterations appeared secondary to chronic candidal infestation. The most common presentation of bacterial or fungal infections of the lips is angular cheilitis (see page 216). Diffuse primary infection of the entire lip is very unusual; most diffuse cases represent a secondary candidal infection in areas of low-grade trauma of the vermilion border of the lip (cheilocandidiasis).

In one review of 75 patients with chronic cheilitis, a thorough evaluation revealed that more than one third represented irritant contact dermatitis (often secondary to chronic lip licking). In 25% of the patients, the cheilitis was discovered to be an allergic contact mucositis (see page 350). Atopic eczema was thought to be the cause in 19% of cases; the remaining portion was related to a wide variety of pathoses.

In spite of a thorough investigation, there often remain a number of patients with classic exfoliative cheilitis for which no underlying cause can be found. These idiopathic cases are most troublesome and often resistant to a wide variety of interventions.

CLINICAL FEATURES: A marked female predominance is seen in cases of factitious origin, with most cases affecting those younger than 30 years of age. Mild cases feature chronic dryness, scaling, or cracking of the vermilion border of the lip (Fig. 8-36). With progression, the vermilion can become covered with a thickened, yellowish hyperkeratotic crust that can be hemorrhagic or that may exhibit extensive fissuring. The perioral skin may become involved and exhibit areas of crusted erythema (Fig. 8-37). Although this pattern may be confused with perioral dermatitis (see page 352), the most appropri ate name for this process is circumoral dermatitis. Both lips or just the lower lip may be involved.

Fig. 8-37 Circumoral dermatitis. Crusting and erythema of the skin surface adjacent to the vermilion border in a child who chronically sucked on both lips.

In patients with chronic cheilitis, development of fissures on the vermilion border is not rare. In a prevalence study of more than 20,000 patients, these fissures involved either lip and were slightly more common in the upper lip. In contrast to typical exfoliative cheilitis, these fissures demonstrate a significant male predilection and a prevalence rate of approximately 0.6%. The majority arise in young adults, with rare occurrence noted in children and older adults.

Although the cause is unknown, proposed contributing factors include overexposure to sun, wind, and cold weather; mouth breathing; bacterial or fungal infections; and smoking. An increased prevalence of lip fissures has been noted in patients with Down syndrome and may be the result of the high frequency of mouth breathing or the tendency to develop orofacial candidiasis. Application of lipstick or lip balm appears to be protective. Fissure occurrence also may be related to a physiologic weakness of the tissues. Those affecting the lower lip typically occur in the midline, whereas fissures on the upper vermilion most frequently involve a lateral position. These are the sites of prenatal merging of the mandibular and maxillary processes.

TREATMENT AND PROGNOSIS: In those cases associated with an obvious cause, elimination of the trigger typically results in resolution of the changes. In those cases with no underlying physical, infectious, or allergic cause, psychotherapy (often combined with mild tranquilization or stress reduction) may achieve resolution. In cases for which no cause can be found, therapeutic interventions often are not successful.

Cases that result from candidal infections often do not resolve until the chronic trauma also is eliminated. Initial topical antifungal agents, antibiotics, or both can be administered to patients in whom chronic trauma is not obvious or is denied. If the condition does not resolve, then further investigation is warranted in an attempt to discover the true source of the lip alterations.

Hydrocortisone and iodoquinol (antibacterial and antimycotic) cream has been used to resolve chronic lip fissures in some patients (Fig. 8-38). Other reported therapies include various corticosteroid preparations, topical tacrolimus, sunscreens, and moisturizing preparations. In many cases, resistance to topical therapy or frequent recurrence is noted. In these cases, cryotherapy or excision with or without Z-plasty has been used successfully.

SUBMUCOSAL HEMORRHAGE

Everyone has experienced a bruise from minor trauma. This occurs when a traumatic event results in hemorrhage and entrapment of blood within tissues. Different terms are used, depending on the size of the hemorrhage:

• Minute hemorrhages into skin, mucosa, or serosa are termed petechiae.

• If a slightly larger area is affected, the hemorrhage is termed a purpura.

• Any accumulation greater than 2 cm is termed an ecchymosis.

• If the accumulation of blood within tissue produces a mass, this is termed a hematoma.

Blunt trauma to the oral mucosa often results in hematoma formation. Less well known are petechiae and purpura, which can arise from repeated or prolonged increased intrathoracic pressure (Valsalva maneuver) associated with such activities as repeated coughing, vomiting, convulsions, or giving birth (Fig. 8-39). When considering a diagnosis of traumatic hemorrhage, the clinician should keep in mind that hemorrhages can result from nontraumatic causes, such as anticoagulant therapy, thrombocytopenia, disseminated intravascular coagulation (DIC), and a number of viral infections, especially infectious mononucleosis and measles.

With the increased frequency of dental implant placement, a number of reports have surfaced related to potentially life-threatening floor of mouth hemorrhage secondary to a tear in the lingual periosteum or perforation of the cortical plate during implant site preparation. Similar spontaneous sublingual hemorrhage has been documented in patients with severe hypertension or a systemic coagulopathy. Another unusual hemorrhagic event involves the development of an organized hematoma within the maxillary sinus. The blood originates from a variety sources, the most common of which is intranasal hemorrhage that drains through the ostia and collects in the antrum.

CLINICAL FEATURES: Submucosal hemorrhage appears as a nonblanching flat or elevated zone with a color that varies from red or purple to blue or blue-black (Fig. 8-40). As would be expected, traumatic lesions are located most frequently on the labial or buccal mucosa. Blunt facial trauma often is responsible, but injuries such as minor as cheek biting may produce a hematoma or areas of purpura (Fig. 8-41). Mild pain may be present.

Fig. 8-40 Purpura. Submucosal hemorrhage of the lower labial mucosa on the left side secondary to blunt trauma.

Fig. 8-41 Hematoma. A, Dark-purple nodular mass of the buccal mucosa in a patient on coumadin therapy. B, Near resolution of the lesion 8 days later after discontinuation of the medication. (Courtesy of Dr. Charles Ferguson.)

The hemorrhage associated with increased intrathoracic pressure usually is located on the skin of the face and neck and appears as widespread petechiae that clear within 24 to 72 hours. Although it has not been as well documented as the cutaneous lesions, mucosal hemorrhage can be seen in the same setting and most often appears as soft palatal petechiae or purpura.

Hematoma formation associated with surgical implant preparation usually is associated with damage of the soft tissues adjacent to the lingual surface of the mandible and produces swelling and elevation of the floor of the mouth. Although the hemorrhage is noticeable immediately in most patients, the problem may not become evident clinically for 4 to 6 hours. Distension, elevation, and protrusion of the tongue may occur and be associated with inability to swallow or significant dyspnea.

Patients with antral hematomas typically complain of frequent nasal bleeding but also may experience unilateral nasal obstruction, hyposmia, headache, and malar swelling. Facial paresthesia and vision problems occur less frequently. Computed tomography (CT) typically demonstrates a soft tissue mass filling and expanding the antrum, often associated with proptosis and partial destruction or displacement of the sinus walls. In many instances, the radiographic appearance is worrisome for a malignant neoplasm.

TREATMENT AND PROGNOSIS: Often, no treatment is required if the hemorrhage is not associated with significant morbidity or related to systemic disease. The areas should resolve spontaneously. Large hematomas may require several weeks to resolve. If the hemorrhage occurs secondary to an underlying disorder, then treatment is directed toward control of the associated disease.

In cases of emergent hemorrhage associated with surgical implant placement, the first priority is to secure the airway. Although the hemorrhage can be controlled with conservative measures in some cases, the majority require surgical exploration with isolation and repair of the damaged vessel. Antral hematomas usually are removed via a Caldwell-Luc procedure for both therapeutic and diagnostic purposes. After successful removal, a search for the bleeding source or any underlying coagulopathy is recommended to prevent recurrence.

ORAL TRAUMA FROM SEXUAL PRACTICES

Although orogenital sexual practices are illegal in many jurisdictions, they are extremely common. Among homosexual men and women, orogenital sexual activity almost is universal. For married heterosexual couples younger than age 25, the frequency has been reported to be as high as 90%. Considering the prevalence of these practices, the frequency of associated traumatic oral lesions is surprisingly low.

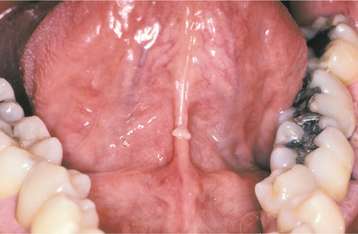

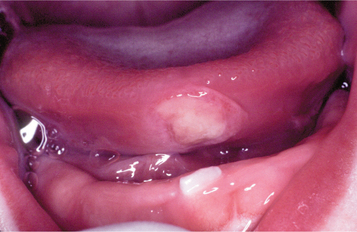

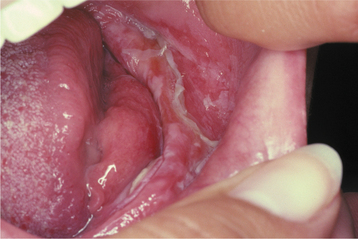

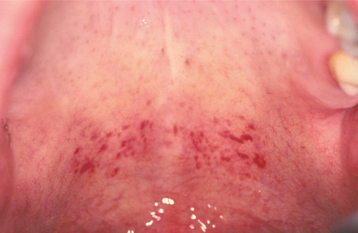

CLINICAL FEATURES: The most commonly reported lesion related to orogenital sex is submucosal palatal hemorrhage secondary to fellatio. The lesions appear as erythema, petechiae, purpura, or ecchymosis of the soft palate. The areas often are asymptomatic and resolve without treatment in 7 to 10 days (Fig. 8-42). Recurrences are possible with repetition of the inciting (exciting?) event. The erythrocytic extravasation is thought to result from the musculature of the soft palate elevating and tensing against an environment of negative pressure. Similar lesions have been induced from coughing, vomiting, or forceful sucking on drinking straws and glasses. Forceful thrusting against the vascular soft palate has been suggested as another possible cause.

Fig. 8-42 Palatal petechiae from fellatio. Submucosal hemorrhage of the soft palate resulting from the effects of negative pressure.

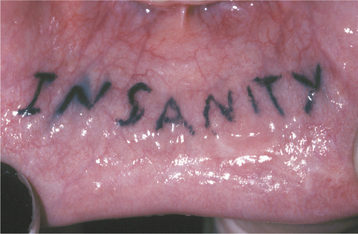

Oral lesions also can occur from performing cunnilingus, resulting in horizontal ulcerations of the lingual frenum. As the tongue is thrust forward, the taut frenum rubs or rakes across the incisal edges of the mandibular central incisors. The ulceration created coincides with sharp tooth edges when the tongue is in its most forward position. The lesions resolve in 7 to 10 days but may recur with repeated performances. Linear fibrous hyperplasia has been discovered in the same pattern in individuals who chronically perform the act (Fig. 8-43).

HISTOPATHOLOGIC FEATURES: With an appropriate index of suspicion, biopsy usually is not required; however, a biopsy has been performed in some cases of palatal lesions secondary to fellatio. These suction-related lesions reveal subepithelial accumulations of red blood cells that may be extensive enough to separate the surface epithelium from underlying connective tissue. Patchy degeneration of the epithelial basal cell layer can occur. The epithelium classically demonstrates migration of erythrocytes and leukocytes from the underlying lamina propria.

TREATMENT AND PROGNOSIS: No treatment is required, and the prognosis is good. In patients who request assistance, palatal petechiae can be prevented through the use of less negative pressure and avoidance of forceful thrusting. Smoothing and polishing the rough incisal edges of the adjacent mandibular teeth can minimize the chance of lingual frenum ulceration.

AMALGAM TATTOO AND OTHER LOCALIZED EXOGENOUS PIGMENTATIONS

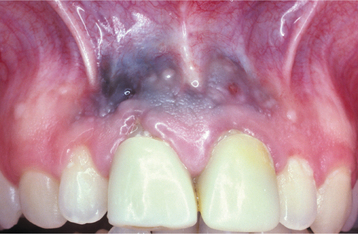

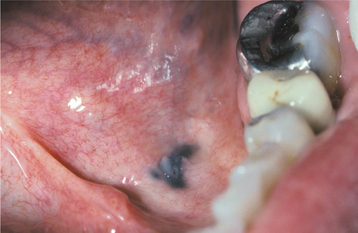

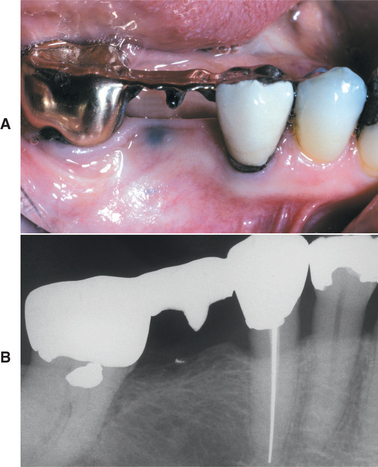

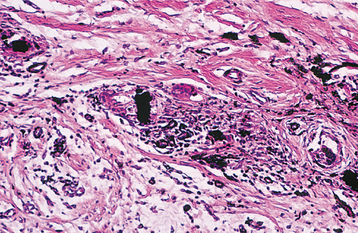

A number of pigmented materials can be implanted within the oral mucosa, resulting in clinically evident pigmentations. Implantation of dental amalgam (amalgam tattoo) occurs most often, with a frequency that far outdistances that for all other materials. Localized argyrosis has been used as another name for amalgam tattoo, but this nomenclature is inappropriate because amalgam contains not only silver but also mercury, tin, copper, zinc, and other metals.