Salivary Gland Pathology

SALIVARY GLAND APLASIA

Salivary gland aplasia is a rare developmental anomaly that can affect one or more of the major salivary glands. The condition may occur alone, although agenesis of the glands is often a component of one of several syndromes, including mandibulofacial dysostosis (Treacher Collins syndrome; see page 45), hemifa-cial microsomia, and lacrimo-auriculo-dento-digital (LADD) syndrome.

CLINICAL AND RADIOGRAPHIC FEATURES: Salivary gland aplasia has been reported more frequently in men than women by a 2:1 ratio. Some individuals are affected by agenesis of all four of the largest glands (both parotids and submandibular glands), but others may be missing only one to three of the four glands. In spite of the absence of the glands, the face still has a normal appearance because the sites are filled in by fat or connective tissue. Intraorally, the orifices of the missing glands are absent.

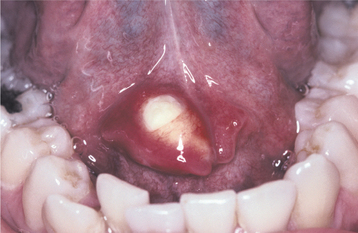

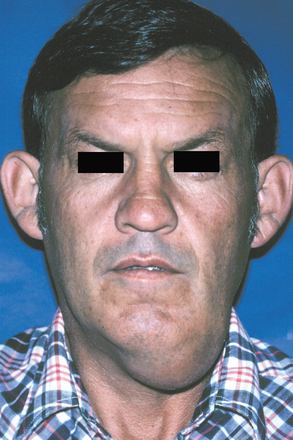

As would be anticipated, the most significant symptom associated with salivary gland aplasia is severe xerostomia with its attendant problems (see page 464). The tongue may appear leathery, and the patient is at greater risk for developing dental caries and erosion (Fig. 11-1). However, some degree of moisture still may be present because of the continued activity of the minor salivary glands. Absence of the major glands can be confirmed by technetium-99m pertechnetate scintiscan, computed tomography (CT), or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI).

Fig. 11-1 Salivary gland aplasia. Dry, leathery tongue and diffuse enamel erosion in a child with aplasia of the major salivary glands.

LADD syndrome is an autosomal dominant disorder that is caused by mutations in the fibroblast growth factor 10 (FGF10) gene. It is characterized by aplasia or hypoplasia of the lacrimal and salivary glands, cup-shaped ears, and dental and digital anomalies. Dental features may include hypodontia, microdontia, and mild enamel hypoplasia.

TREATMENT AND PROGNOSIS: Patient management is directed toward compensating for the saliva deficiency, and saliva substitutes are often necessary. If any residual functional salivary gland tissue is present, then sialagogue medications such as pilocarpine or cevimeline may be used to increase saliva production. Salivary flow also may be stimulated via the use of sugarless gum or sour candy. Regular preventive dental care is important to avoid xero-stomia-related caries and enamel breakdown.

MUCOCELE (MUCUS EXTRAVASATION PHENOMENON; MUCUS ESCAPE REACTION)

The mucocele is a common lesion of the oral mucosa that results from rupture of a salivary gland duct and spillage of mucin into the surrounding soft tissues. This spillage is often the result of local trauma, although there is no known history of trauma in many cases. Unlike the salivary duct cyst (see page 457), the mucocele is not a true cyst because it lacks an epithelial lining. Some authors, however, have included true salivary duct cysts in their reported series of cases, sometimes under the classification of retention mucocele. Because these two entities exhibit distinctly different clinical and histopathologic features, they are discussed as separate topics in this chapter.

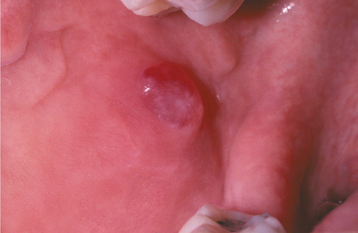

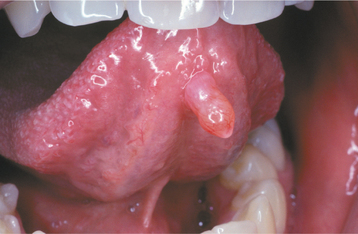

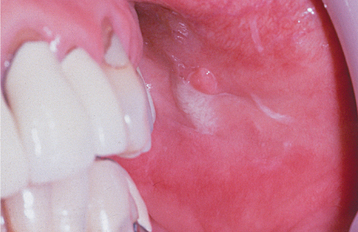

CLINICAL FEATURES: Mucoceles typically appear as dome-shaped mucosal swellings that can range from 1 or 2 mm to several centimeters in size (Figs. 11-2 to 11-4). They are most common in children and young adults, perhaps because younger people are more likely to experience trauma that induces mucin spillage. However, mucoceles have been reported in patients of all ages, including infants and older adults. The spilled mucin below the mucosal surface often imparts a bluish translucent hue to the swelling, although deeper mucoceles may be normal in color. The lesion characteristically is fluctuant, but some mucoceles feel firmer to palpation. The reported duration of the lesion can vary from a few days to several years; most patients report that the lesion has been present for several weeks. Many patients relate a history of a recurrent swelling that periodically may rupture and release its fluid contents.

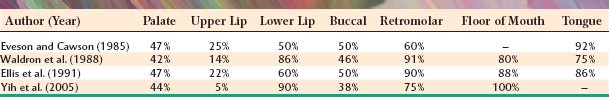

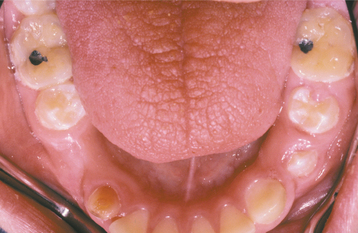

The lower lip is by far the most common site for the mucocele; a recent large study of 1824 cases found that 81% occurred at this one site (Table 11-1). Lower lip mucoceles usually are found lateral to the midline. Less common sites include the floor of mouth (ranulas: 5.8%), anterior ventral tongue (from the glands of Blandin-Nuhn: 5.7%), buccal mucosa (4.7%), palate (1.4%), and retromolar pad (0.5%). Mucoceles rarely develop on the upper lip. In the large series summarized in Table 11-1, not a single example was identified from the upper lip. This is in contrast to salivary gland tumors, which are not unusual in the upper lip but are distinctly uncommon in the lower lip.

Table 11-1

Data from Chi A, Lambert P, Richardson M et al: Oral mucoceles: a clinicopathologic review of 1,824 cases including unusual variants, Abstract No. 19. Paper presented at the annual meeting of the American Academy of Oral and Maxillofacial Pathology, Kansas City, Mo, 2007. American Academy of Oral and Maxillofacial Pathology

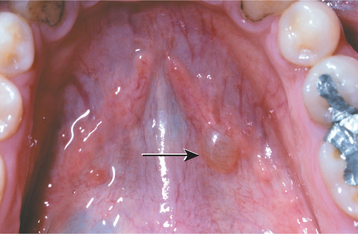

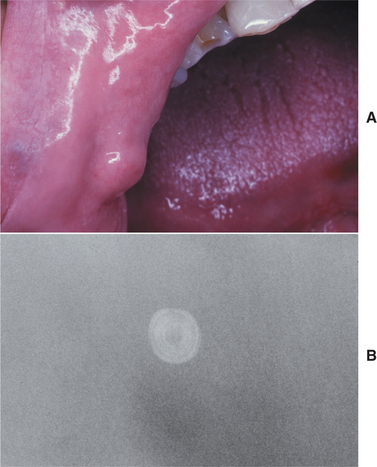

As noted, the soft palate and retromolar area are uncommon sites for mucoceles. However, one interesting variant, the superficial mucocele, does develop in these areas and along the posterior buccal mucosa. Superficial mucoceles present as single or multiple tense vesicles that measure 1 to 4 mm in diameter (Fig. 11-5). The lesions often burst, leaving shallow, painful ulcers that heal within a few days. Repeated episodes at the same location are not unusual. Some patients relate the development of the lesions to mealtimes. Superficial mucoceles also have been reported to occur in association with lichenoid disorders, such as lichen planus, lichenoid drug eruptions, and chronic graft-versus-host disease (GVHD). The vesicular appearance is created by the superficial nature of the mucin spillage, which causes a separation of the epithelium from the connective tissue. The pathologist must be aware of this lesion and should not mistake it microscopically for a vesiculobullous disorder, especially mucous membrane (cicatricial) pemphigoid.

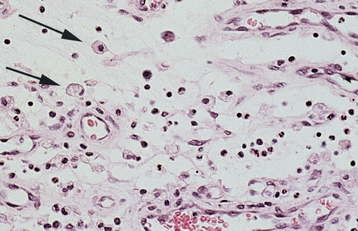

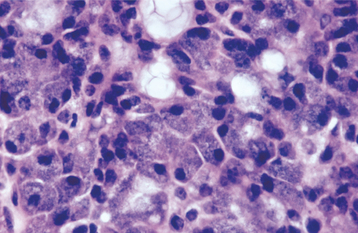

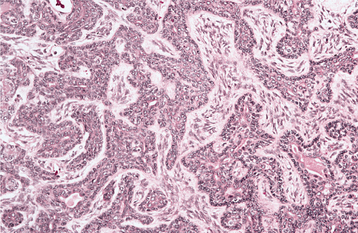

HISTOPATHOLOGIC FEATURES: On microscopic examination, the mucocele shows an area of spilled mucin surrounded by a granulation tissue response (Figs. 11-6 and 11-7). The inflammation usually includes numerous foamy histiocytes (macrophages). In some cases a ruptured salivary duct may be identified feeding into the area. The adjacent minor salivary glands often contain a chronic inflammatory cell infiltrate and dilated ducts.

TREATMENT AND PROGNOSIS: Some mucoceles are short-lived lesions that rupture and heal by themselves. Many lesions, however, are chronic in nature, and local surgical excision is necessary. To minimize the risk of recurrence, the surgeon should remove any adjacent minor salivary glands that may be feeding into the lesion when the area is excised. The excised tissue should be submitted for microscopic examination to confirm the diagnosis and rule out the possibility of a salivary gland tumor. The prognosis is excellent, although occasional mucoceles will recur, necessitating reexcision, especially if the feeding glands are not removed.

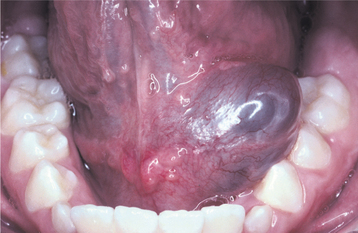

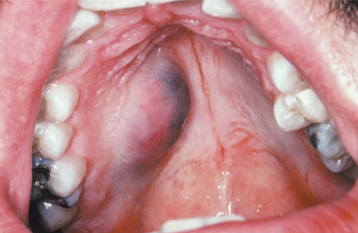

RANULA: Ranula is a term used for mucoceles that occur in the floor of the mouth. The name is derived from the Latin word rana, which means “frog,” because the swelling may resemble a frog’s translucent underbelly. The term ranula also has been used to describe other similar swellings in the floor of the mouth, including true salivary duct cysts, dermoid cysts, and cystic hygromas. However, the term is best used for mucus escape reactions (mucoceles). The source of mucin spillage is usually from the sublingual gland, but ranulas also may arise from the submandibular duct or, possibly, from minor salivary glands in the floor of the mouth. Larger ranulas usually arise from the body of the sublingual gland, although smaller lesions can develop along the sublingual plica from the superficial ducts of Rivini of this gland.

CLINICAL FEATURES: The ranula usually appears as a blue, dome-shaped, fluctuant swelling in the floor of the mouth (Fig. 11-8), but deeper lesions may be normal in color. Ranulas are seen most frequently in children and young adults. They tend to be larger than mucoceles in other oral locations, often developing into large masses that fill the floor of the mouth and elevate the tongue. The ranula usually is located lateral to the midline, a feature that may help to distinguish it from a midline dermoid cyst (see page 33). Like other mucoceles, ranulas may rupture and release their mucin contents, only to re-form.

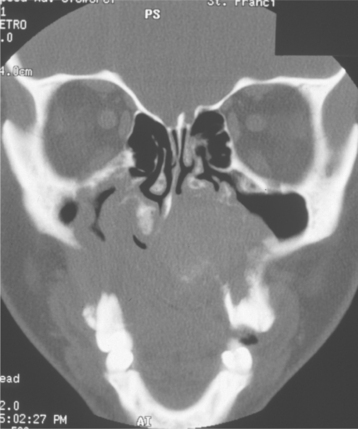

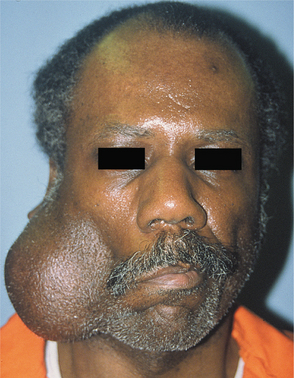

An unusual clinical variant, the plunging or cervical ranula, occurs when the spilled mucin dissects through the mylohyoid muscle and produces swelling within the neck (Fig. 11-9). A concomitant swelling in the floor of the mouth may or may not be present. If no lesion is produced in the mouth, then the clinical diagnosis of ranula may not be suspected. Imaging studies can be helpful in supporting a diagnosis of plunging ranula and in determining the origin of the lesion. CT and MRI images of plunging ranulas that arise from the sublingual gland often exhibit a slight extension of the lesion into the sublingual space (“tail sign”)—an imaging feature not observed in lesions that develop from the submandibular gland.

HISTOPATHOLOGIC FEATURES: The microscopic appearance of a ranula is similar to that of a mucocele in other locations. The spilled mucin elicits a granulation tissue response that typically contains foamy histiocytes.

TREATMENT AND PROGNOSIS: Treatment of the ranula consists of removal of the feeding sublingual gland and/or marsupialization. Marsupialization (exteriorization) entails removal of the roof of the intraoral lesion, which often can be successful for small, superficial ranulas associated with the ducts of Rivini. However, marsupialization is often unsuccessful for larger ranulas developing from the body of the sublingual gland, and most authors emphasize that removal of the offending gland is the most important consideration in preventing a recurrence of the lesion. If the gland is removed, then meticulous dissection of the lining of the lesion may not be necessary for the lesion to resolve, even for the plunging ranula.

SALIVARY DUCT CYST (MUCUS RETENTION CYST; MUCUS DUCT CYST; SIALOCYST)

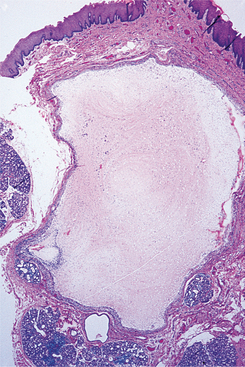

The salivary duct cyst is an epithelium-lined cavity that arises from salivary gland tissue. Unlike the more common mucocele (see page 454), it is a true developmental cyst that is lined by epithelium that is separate from the adjacent normal salivary ducts. The cause of such cysts is uncertain.

Cystlike dilatation of salivary ducts also may develop secondary to ductal obstruction (e.g., mucus plug), which creates increased intraluminal pressure. Although some authors refer to such lesions as mucus retention cysts, such lesions probably represent salivary ductal ectasia rather than a true cyst.

CLINICAL FEATURES: Salivary duct cysts usually occur in adults and can arise within either the major or minor glands. Cysts of the major glands are most common within the parotid gland, presenting as slowly growing, asymptomatic swellings. Intraoral cysts can occur at any minor gland site, but most frequently they develop in the floor of the mouth, buccal mucosa, and lips (Fig. 11-10). They often look like mucoceles and are characterized by a soft, fluctuant swelling that may appear bluish, depending on the depth of the cyst below the surface. Some cysts may feel relatively firm to palpation. Cysts in the floor of the mouth often arise adjacent to the submandibular duct and sometimes have an amber color.

On rare occasions, patients have been observed to develop prominent ectasia of the excretory ducts of many of the minor salivary glands throughout the mouth. Such lesions have been termed “mucus retention cysts,” although they probably represent multi-focal ductal dilatation. The individual lesions often present as painful nodules that demonstrate dilated ductal orifices on the mucosal surface. Mucus or pus may be expressed from these dilated ducts.

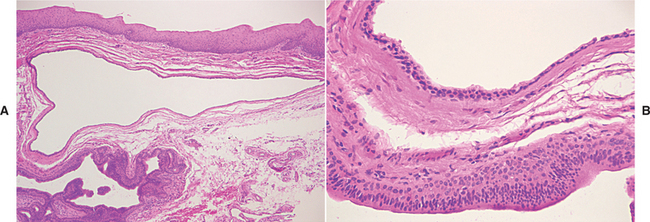

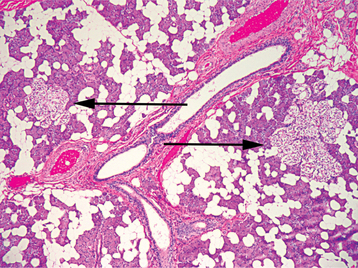

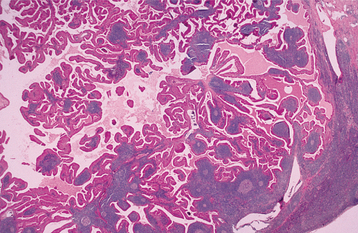

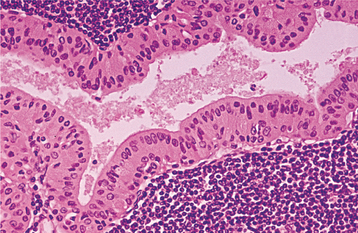

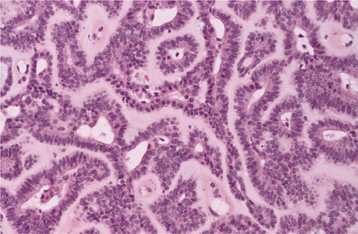

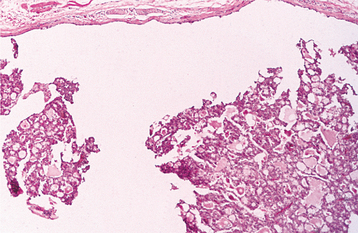

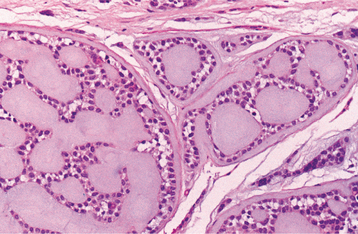

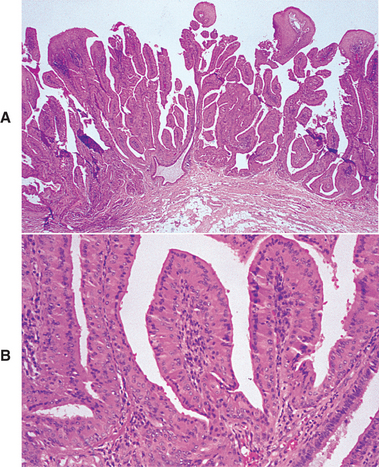

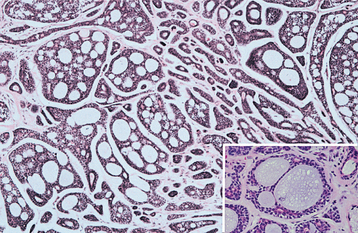

HISTOPATHOLOGIC FEATURES: The lining of the salivary duct cyst is variable and may consist of cuboidal, columnar, or atrophic squamous epithelium surrounding thin or mucoid secretions in the lumen (Fig. 11-11). In contrast, ductal ectasia secondary to salivary obstruction is characterized by oncocytic metaplasia of the epithelial lining. This epithelium often demonstrates papillary folds into the cystic lumen, somewhat reminiscent of a small Warthin tumor (see page 482) but without the prominent lymphoid stroma (Fig. 11-12). If this proliferation is extensive enough, then these lesions sometimes are diagnosed as papillary cystadenoma, although it seems likely that most are not true neoplasms. The individual lesions of patients with multiple “mucus retention cysts” also show prominent oncocytic metaplasia of the epithelial lining.

TREATMENT AND PROGNOSIS: Isolated salivary duct cysts are treated by conservative surgical excision. For cysts in the major glands, partial or total removal of the gland may be necessary. The lesion should not recur.

For rare patients who develop multifocal salivary ductal ectasia (“mucus retention cysts”), local excision may be performed for the more problematic swellings; however, surgical management does not appear feasible or advisable for all of the lesions, which may number as many as 100. In one reported case, systemic erythromycin and chlorhexidine mouth rinses were helpful in relieving pain and reducing drainage of pus. Sialagogue medications also may be helpful in stimulating salivary flow, thereby preventing the accumulation of inspissated mucus within the dilated excretory ducts.

SIALOLITHIASIS (SALIVARY CALCULI; SALIVARY STONES)

Sialoliths are calcified structures that develop within the salivary ductal system. Researchers believe that they arise from deposition of calcium salts around a nidus of debris within the duct lumen. This debris may include inspissated mucus, bacteria, ductal epithelial cells, or foreign bodies. The cause of sialoliths is unclear, but their formation can be promoted by chronic sialadenitis and partial obstruction. Their development is not related to any systemic derangement in calcium and phosphorus metabolism.

CLINICAL AND RADIOGRAPHIC FEATURES: Sialoliths most often develop within the ductal system of the submandibular gland; the formation of stones within the parotid gland system is distinctly less frequent. The long, tortuous, upward path of the submandibular (Wharton’s) duct and the thicker, mucoid secretions of this gland may be responsible for its greater tendency to form salivary calculi. Sialoliths also can form within the minor salivary glands, most often within the glands of the upper lip or buccal mucosa. Salivary stones can occur at almost any age, but they are most common in young and middle-aged adults.

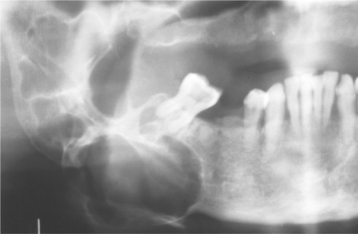

Major gland sialoliths most frequently cause episodic pain or swelling of the affected gland, especially at mealtime. The severity of the symptoms varies, depending on the degree of obstruction and the amount of resultant backpressure produced within the gland. If the stone is located toward the terminal portion of the duct, then a hard mass may be palpated beneath the mucosa (Fig. 11-13).

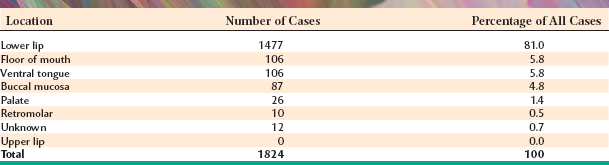

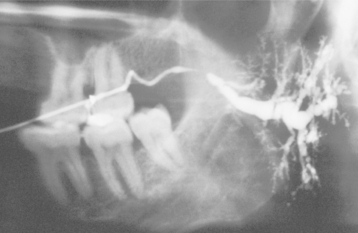

Sialoliths typically appear as radiopaque masses on radiographic examination. However, not all stones are visible on standard radiographs (perhaps because of the degree of calcification of some lesions). They may be discovered anywhere along the length of the duct or within the gland itself (Fig. 11-14). Stones in the terminal portion of the submandibular duct are best demonstrated with an occlusal radiograph. On panoramic or periapical radiographs, the calcification may appear superimposed on the mandible and care must be exercised not to confuse it with an intrabony lesion (Fig. 11-15). Multiple parotid stones radiographically can mimic calcified parotid lymph nodes, such as might occur in tuberculosis. Sialography, ultrasound, and CT scanning may be helpful additional imaging studies for sialoliths.

Fig. 11-14 Sialolithiasis. Radiopaque mass located at the left angle of the mandible. (Courtesy of Dr. Roger Bryant.)

Fig. 11-15 Sialolithiasis. A, Periapical film showing discrete radiopacity (arrow) superimposed on the body of the mandible. Care must be taken not to confuse such lesions with intrabony pathosis. B, Occlusal radiograph of same patient demonstrating radiopaque stone in Wharton’s duct.

Minor gland sialoliths often are asymptomatic but may produce local swelling or tenderness of the affected gland (Fig. 11-16). A small radiopacity often can be demonstrated with a soft tissue radiograph.

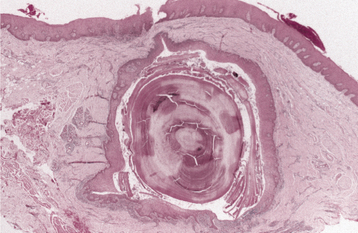

HISTOPATHOLOGIC FEATURES: On gross examination, sialoliths appear as hard masses that are round, oval, or cylindrical. They are typically yellow, although they may be a white or yellow-brown color. Submandibular stones tend to be larger than those of the parotid or minor glands. Sialoliths are usually solitary, although occasionally two or more stones may be discovered at surgery.

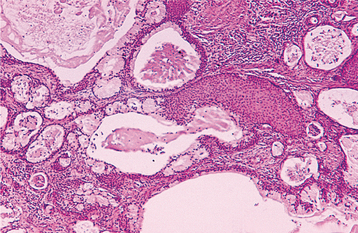

Microscopically, the calcified mass exhibits concentric laminations that may surround a nidus of amorphous debris (Fig. 11-17). If the associated duct also is removed, then it often demonstrates squamous, oncocytic, or mucous cell metaplasia. Periductal inflammation is also evident. The ductal obstruction frequently is associated with an acute or chronic sialadenitis of the feeding gland.

TREATMENT AND PROGNOSIS: Small sialoliths of the major glands sometimes can be treated conservatively by gentle massage of the gland in an effort to milk the stone toward the duct orifice. Sialagogues (drugs that stimulate salivary flow), moist heat, and increased fluid intake also may promote passage of the stone. Larger sialoliths usually need to be removed surgically. If significant inflammatory damage has occurred within the feeding gland, then the gland may need to be removed. Minor gland sialoliths are best treated by surgical removal, including the associated gland.

Shock wave lithotripsy (extracorporeal or intracorporeal), salivary gland endoscopy, and radiologically guided basket retrieval are newer techniques that have been shown to be effective in the removal of sialoliths from the major glands. These minimally invasive techniques have low morbidity and may preclude the necessity of gland removal.

SIALADENITIS

Inflammation of the salivary glands (sialadenitis) can arise from various infectious and noninfectious causes. The most common viral infection is mumps (see page 263), although a number of other viruses also can involve the salivary glands, including Coxsackie A, ECHO, choriomeningitis, parainfluenza, and cytomegalovirus (CMV) (in neonates). Most bacterial infections arise as a result of ductal obstruction or decreased salivary flow, allowing retrograde spread of bacteria throughout the ductal system. Blockage of the duct can be caused by sialolithiasis (see page 459), congenital strictures, or compression by an adjacent tumor. Decreased flow can result from dehydration, debilitation, or medications that inhibit secretions.

One of the more common causes of sialadenitis is recent surgery (especially abdominal surgery), after which an acute parotitis (surgical mumps) may arise because the patient has been kept without food or fluids (NPO) and has received atropine during the surgical procedure. Other medications that produce xerostomia as a side effect also can predispose patients to such an infection. Most cases of acute bacterial sialadenitis are caused by Staphylococcus aureus, but they also may arise from streptococci or other organisms. Noninfectious causes of salivary inflammation include Sjögren syndrome (see page 466), sarcoidosis (see page 338), radiation therapy (see page 295), and various allergens.

CLINICAL AND RADIOGRAPHIC FEATURES: Acute bacterial sialadenitis is most common in the parotid gland and is bilateral in 10% to 25% of cases. The affected gland is swollen and painful, and the overlying skin may be warm and erythematous (Fig. 11-18). An associated low-grade fever and trismus may be present. A purulent discharge often is observed from the duct orifice when the gland is massaged (Fig. 11-19).

Fig. 11-19 Sialadenitis. A purulent exudate can be seen arising from Stensen’s duct when the parotid gland is massaged.

Recurrent or persistent ductal obstruction (most commonly caused by sialoliths) can lead to a chronic sialadenitis. Periodic swelling and pain occur within the affected gland, usually developing at mealtime when salivary flow is stimulated. In the submandibular gland, persistent enlargement may develop (Küttner tumor), which is difficult to distinguish from a true neoplasm. Sialography often demonstrates sialectasia (ductal dilatation) proximal to the area of obstruction (Fig. 11-20). In chronic parotitis, Stensen’s duct may show a characteristic sialographic pattern known as “sausaging,” which reflects a combination of dilatation plus ductal strictures from scar formation. Chronic sialadenitis also can occur in the minor glands, possibly as a result of blockage of ductal flow or local trauma.

Fig. 11-20 Chronic sialadenitis. Parotid sialogram demonstrating ductal dilatation proximal to an area of obstruction. (Courtesy of Dr. George Blozis.)

Subacute necrotizing sialadenitis is a form of salivary inflammation that occurs most commonly in teenagers and young adults. The lesion usually involves the minor salivary glands of the hard or soft palate, presenting as a painful nodule that is covered by intact, erythematous mucosa. Unlike necrotizing sialometaplasia (see page 471), the lesion does not ulcerate or slough necrotic tissue. An infectious or allergic cause has been hypothesized.

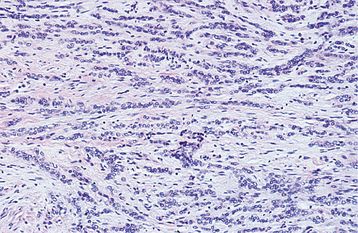

HISTOPATHOLOGIC FEATURES: In patients with acute sialadenitis, accumulation of neutrophils is observed within the ductal system and acini. Chronic sialadenitis is characterized by scattered or patchy infiltration of the salivary parenchyma by lymphocytes and plasma cells. Atrophy of the acini is common, as is ductal dilatation. If associated fibrosis is present, then the term chronic sclerosing sialadenitis is used (Fig. 11-21).

Fig. 11-21 Chronic sclerosing sialadenitis. Chronic inflammatory infiltrate with associated acinar atrophy, ductal dilatation, and fibrosis.

Subacute necrotizing sialadenitis is characterized by a heavy mixed inflammatory infiltrate consisting of neutrophils, lymphocytes, histiocytes, and eosinophils. There is loss of most of the acinar cells, and many of the remaining ones exhibit necrosis. The ducts tend to be atrophic and do not show hyperplasia or squamous metaplasia.

TREATMENT AND PROGNOSIS: The treatment of acute sialadenitis includes appropriate antibiotic therapy and rehydration of the patient to stimulate salivary flow. Surgical drainage may be needed if there is abscess formation. Although this regimen is usually sufficient, a 20% to 50% mortality rate has been reported in debilitated patients because of the spread of the infection and sepsis.

The management of chronic sialadenitis depends on the severity of the condition and ranges from conservative therapy to surgical intervention. Initial management often includes antibiotics, analgesics, sialagogues, and glandular massage. Early cases that develop secondary to ductal blockage may respond to removal of the sialolith or other obstruction. However, if sialectasia is present, then the dilated ducts can lead to stasis of secretions and predispose the gland to further sialolith formation. Sialadenoscopy and ductal irrigation are newer techniques that can be used to dilate ductal strictures and to eliminate sialoliths and mucus plugs. Second-line treatment options for chronic parotitis have included ligation of Stensen’s duct, but this method has a high failure rate. Tympanic neurectomy, which results in decreased secretion by the parotid gland via transection of the parasympathetic secretory fibers at the tympanic plexus, produces improvement in 75% of patients with chronic parotitis. If conservative methods cannot control chronic sialadenitis, then surgical removal of the affected gland may be necessary.

Subacute necrotizing sialadenitis is a self-limiting condition that usually resolves within 2 weeks of diagnosis without treatment.

CHEILITIS GLANDULARIS

Cheilitis glandularis is a rare inflammatory condition of the minor salivary glands. The cause is uncertain, although several etiologic factors have been suggested, including actinic damage, tobacco, syphilis, poor hygiene, and heredity.

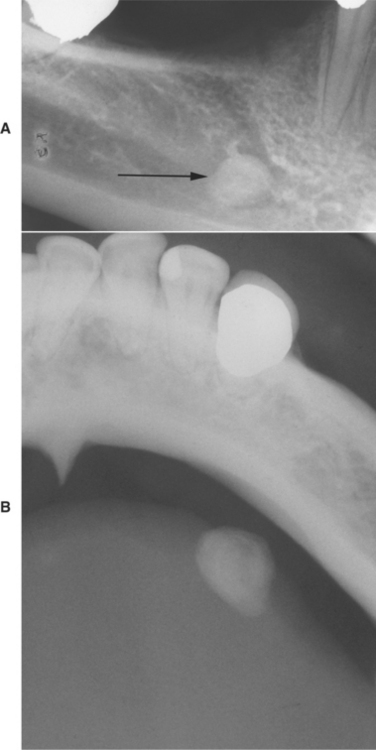

CLINICAL FEATURES: Cheilitis glandularis characteristically occurs on the lower lip, although there are also purported cases involving the upper lip and palate. Affected individuals experience swelling and eversion of the lower lip as a result of hypertrophy and inflammation of the glands (Fig. 11-22). The openings of the minor salivary ducts are inflamed and dilated, and pressure on the glands may produce mucopurulent secretions from the ductal openings. The condition most often has been reported in middle-aged and older men, although cases also have been described in women and children. However, some of the childhood cases may represent other entities, such as exfoliative cheilitis (see page 304).

Fig. 11-22 Cheilitis glandularis. Prominent lower lip with inflamed openings of the minor salivary gland ducts. An early squamous cell carcinoma has developed on the patient’s left side just lateral to the midline (arrow). (Courtesy of Dr. George Blozis.)

Historically, cheilitis glandularis has been classified into three types, based on the severity of the disease:

The latter two types represent progressive stages of the disease with bacterial involvement; they are characterized by increasing inflammation, suppuration, ulceration, and swelling of the lip.

HISTOPATHOLOGIC FEATURES: The microscopic findings of cheilitis glandularis are not specific and usually consist of chronic sialadenitis and ductal dilatation. Concomitant dysplastic changes may be observed in the overlying surface epithelium in some cases.

TREATMENT AND PROGNOSIS: The treatment of choice for most cases of persistent cheilitis glandularis associated with actinic damage is vermilionectomy (lip shave), which usually produces a satisfactory cosmetic result. A significant percentage of cases (18% to 35%) have been associated with the development of squamous cell carcinoma of the overlying epithelium of the lip. Because actinic damage has been implicated in many cases of cheilitis glandularis, it is likely that this same solar radiation is responsible for the malignant degeneration.

SIALORRHEA

Sialorrhea, or excessive salivation, is an uncommon condition that has various causes. Minor sialorrhea may result from local irritations, such as aphthous ulcers or ill-fitting dentures. Patients with new dentures often experience excess saliva production until they become accustomed to the prosthesis. Episodic hypersecretion of saliva, or “water brash,” may occur as a protective buffering system to neutralize stomach acid in individuals with gastroesophageal reflux dis-ease. Sialorrhea is a well-known clinical feature of rabies and heavy-metal poisoning (see page 313). It also may occur as a consequence of certain medications, such as antipsychotic agents, especially clozapine, and cholinergic agonists used to treat dementia of the Alzheimer’s type and myasthenia gravis.

Drooling can be a problem for patients who are mentally retarded, who have undergone surgical resection of the mandible, or who have various neurologic disorders such as cerebral palsy, Parkinson’s disease, or amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS). In these instances, the drooling is probably not caused by overproduction of saliva but by poor neuromuscular control.

In addition, there is a second group of patients who report complaints of drooling; however, no obvious clinical evidence of excessive saliva production is observed, and they do not have any of the recognized causes for sialorrhea. Personality analysis has suggested that the complaint of sialorrhea in such otherwise healthy patients does not have an organic basis but may be associated with high levels of neuroticism and a tendency to dissimulate.

CLINICAL FEATURES: The excess saliva production typically produces drooling and choking, which may cause social embarrassment. In children with mental retardation or cerebral palsy, the uncontrolled salivary flow may lead to macerated sores around the mouth, chin, and neck that can become secondarily infected. The constant soiling of clothes and bed linens can be a significant problem for the parents and caretakers of these patients.

An interesting type of supersalivation of unknown cause has been termed idiopathic paroxysmal sialorrhea. Individuals with this condition experience short episodes of excessive salivation lasting from 2 to 5 minutes. These episodes are associated with a prodrome of nausea or epigastric pain.

TREATMENT AND PROGNOSIS: Some causes of sialorrhea are transitory or mild, and no treatment is needed. For individuals with increased salivation associated with gastroesophageal reflux disease, medical management of their reflux problem may be beneficial.

For persistent severe drooling, therapeutic intervention may be indicated. Speech therapy can be used to improve neuromuscular control, but patient cooperation is necessary. Anticholinergic medications can decrease saliva production but may produce unacceptable side effects. Transdermal scopolamine has been tried with some success, but it should not be used in children younger than age 10. Intraglandular injection of botulinum toxin has been shown to be successful in reducing salivary secretions, with a duration of action that varies from 6 weeks to 6 months.

Several surgical techniques have been used successfully to control severe drooling in individuals with poor neuromuscular control:

• Relocation of the submandibular ducts (sometimes along with excision of the sublingual glands)

• Relocation of the parotid ducts

• Submandibular gland excision plus parotid duct ligation

• Ligation of the parotid and submandibular ducts

• Bilateral tympanic neurectomy with sectioning of the chorda tympani

In ductal relocation, the ducts are repositioned posteriorly to the tonsillar fossa, thereby redirecting salivary flow and minimizing drooling. The use of bilateral tympanic neurectomy and sectioning of the chorda tympani destroys parasympathetic innervation to the glands, reducing salivary secretions and possibly inducing xerostomia. However, this procedure also produces a loss of taste to the anterior two thirds of the tongue.

XEROSTOMIA

Xerostomia refers to a subjective sensation of a dry mouth; it is frequently, but not always, associated with salivary gland hypofunction. A number of factors may play a role in the cause of xerostomia, and these are listed in Box 11-1. Xerostomia is a common problem that has been reported in 25% of older adults. In the past, complaints of dry mouth in older patients often were ascribed to the predictable result of aging. However, it is now generally accepted that any reductions in salivary function associated with age are modest and probably are not associated with any significant reduction in salivary function. Instead, xerostomia in older adults is more likely to be the result of other factors, especially medications. More than 500 drugs have been reported to produce xerostomia as a side effect, including 63% of the 200 most frequently prescribed medicines in the United States. A list of the most common and significant drugs associated with xerostomia is provided in Table 11-2. Not only are specific drugs known to produce dry mouth, but the prevalence of xerostomia also increases in relation to the total number of drugs that a person takes, regardless of whether the individual medications are xerogenic or not.

Table 11-2

Medications That May Produce Xerostomia

| Class of Drug | Example |

| Antihistamine agents | Diphenhydramine |

| Chlorpheniramine | |

| Decongestant agents | Pseudoephedrine |

| Antidepressant agents | Amitriptyline |

| Citalopram | |

| Fluoxetine | |

| Paroxetine | |

| Sertraline | |

| Bupropion | |

| Antipsychotic agents | Phenothiazine derivatives |

| Haloperidol | |

| Sedatives and anxiolytic agents | Diazepam |

| Lorazepam | |

| Alprazolam | |

| Antihypertensive agents | Reserpine |

| Methyldopa | |

| Chlorothiazide | |

| Furosemide | |

| Metoprolol | |

| Calcium channel blockers | |

| Anticholinergic agents | Atropine |

| Scopolamine |

CLINICAL FEATURES: Examination of the patient typically demonstrates a reduction in salivary secretions, and the residual saliva appears either foamy or thick and “ropey.” The mucosa appears dry, and the clinician may notice that the examining gloves stick to the mucosal surfaces. The dorsal tongue often is fissured with atrophy of the filiform papillae (see Fig. 11-1). The patient may complain of difficulty with mastication and swallowing, and they may even indicate that food adheres to the oral membranes during eating. The clinical findings, however, do not always correspond to the patient’s symptoms. Some patients who complain of dry mouth may appear to have adequate salivary flow and oral moistness. Conversely, some patients who clinically appear to have a dry mouth have no complaints. The degree of saliva production can be assessed by measuring both resting and stimulated salivary flow.

There is an increased prevalence of oral candidiasis in patients with xerostomia because of the reduction in the cleansing and antimicrobial activity normally provided by saliva. In addition, these patients are more prone to dental decay, especially cervical and root caries. This problem has been associated more often with radiation therapy, and it is sometimes called radiation-induced caries but more appropriately should be called xerostomia-related caries (see page 296).

TREATMENT AND PROGNOSIS: The treatment of xerostomia is difficult and often unsatisfactory. Artificial salivas are available and may help make the patient more comfortable, as may continuous sips of water throughout the day. In addition, sugarless candy can be used in an effort to stimulate salivary flow. One of the better patient-accepted management approaches includes the use of oral hygiene products that contain lactoperoxidase, lysozyme, and lactoferrin (e.g., Biotene toothpaste and mouth rinse, Oralbalance gel). If the dryness is secondary to the patient’s medication, then discontinuation or dose modification in consultation with the patient’s physician may be considered; a substitute drug can also be tried.

Systemic pilocarpine is a parasympathomimetic agonist that can be used as a sialagogue. At doses of 5 to 10 mg, three to four times daily, it can be an effective promoter of salivary secretion. Excess sweating is a common side effect, but more serious problems, such as increased heart rate and blood pressure, are uncommon. The U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has also approved cevimeline hydrochloride, an acetylcholine derivative, for use as a sialagogue. Both pilocarpine and cevimeline are contraindicated in patients with narrow-angle glaucoma.

Because of the increased potential for dental caries in patients with xerostomia, frequent dental visits are recommended. Office and daily home fluoride applications can be used to help prevent decay, and chlorhexidine mouth rinses minimize plaque buildup.

BENIGN LYMPHOEPITHELIAL LESION (MYOEPITHELIAL SIALADENITIS): In the late 1800s, Johann von Mikulicz-Radecki described the case of a patient with an unusual bilateral painless swelling of the lacrimal glands and all of the salivary glands. Histopathologic examination of the involved glands showed an intense lymphocytic infiltrate, with features that today are recognized microscopically as the benign lymphoepithelial lesion. This clinical presentation became known as Mikulicz disease, and clinicians began using this term to describe a variety of cases of bilateral parotid and lacrimal enlargement. However, many of these cases were not examples of benign lymphoepithelial lesions microscopically; instead, they represented salivary and lacrimal involvement by other disease processes, such as tuberculosis, sarcoidosis, and lymphoma. These cases of parotid and lacrimal enlargement secondary to other diseases were later recognized as being different and termed Mikulicz syndrome, with the term Mikulicz disease reserved for cases associated with benign lymphoepithelial lesions. However, these two terms have become so confusing and ambiguous that they should no longer be used.

Many cases of so-called Mikulicz disease may be examples of what is now more commonly known as Sjögren syndrome (see page 466). Sjögren syndrome is an autoimmune disease that may produce bilateral salivary and lacrimal enlargement, with microscopic features of benign lymphoepithelial lesion. However, not all benign lymphoepithelial lesions are necessarily associated with the clinical disease complex of Sjögren syndrome.

CLINICAL FEATURES: Most benign lymphoepithelial lesions develop as a component of Sjögren syndrome. Those not associated with Sjögren syndrome are usually unilateral, although occasional bilateral examples are seen. On occasion, benign lymphoepithelial lesions occur in association with other salivary gland pathologic conditions, such as sialoliths and benign or malignant epithelial tumors.

The benign lymphoepithelial lesion most often develops in adults, with a mean age of 50. From 60% to 80% of cases occur in women. Eighty-five percent of cases occur in the parotid gland, with infrequent examples also reported in the submandibular gland and minor salivary glands. The lesion usually appears as a firm, diffuse swelling of the affected gland that sometimes is dramatic in size. It may be asymptomatic or associated with mild pain.

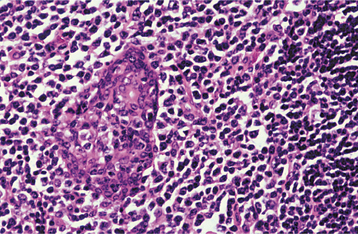

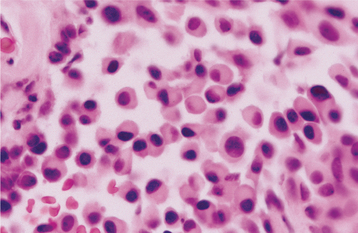

HISTOPATHOLOGIC FEATURES: Microscopic examination of the benign lymphoepithelial lesion shows a heavy lymphocytic infiltrate associated with the destruction of the salivary acini (Fig. 11-23). Germinal centers may or may not be seen. Although the acini are destroyed, the ductal epithelium persists. The ductal cells and surrounding myoepithelial cells become hyperplastic, forming highly characteristic groups of cells, known as epimyoepithelial islands, throughout the lymphoid proliferation. The presence of epimyoepithelial islands once was considered indicative of a benign process, but now it is recognized that these islands also can be found in low-grade salivary lymphomas of the mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue (MALT lymphomas, marginal zone B-cell lymphomas).

TREATMENT AND PROGNOSIS: Although the benign lymphoepithelial lesion fre-quently necessitates surgical removal of the involved gland, the prognosis in most cases is good. However, individuals with benign lymphoepithelial lesions have an increased risk for lymphoma, either within the affected gland or in an extrasalivary site. Although the exact risk is uncertain, one study showed the risk in patients with Sjögren syndrome to be more than 40 times higher than expected in the general population. (The management of patients with Sjögren syndrome is discussed on page 470.)

With the development of modern molecular techniques to assess for gene rearrangements and monoclonality within lymphoid infiltrates, it is now recognized that some lesions originally believed to represent benign lymphoepithelial lesions are actually early-stage MALT lymphomas. Many experts now recognize a spectrum of salivary lymphoid proliferations, which range from benign lymphoepithelial lesions to borderline lesions to frank lymphomas. Because of this, some authors have dropped the term benign from this spectrum and refer to these proliferations only as lymphoepithelial lesions. Fortunately, most MALT lymphomas are low-grade tumors that tend to remain localized with good survival rates. However, occasional tumors transform to higher-grade lymphomas with more aggressive behavior.

In addition, a rare malignant counterpart of this lesion, called a malignant lymphoepithelial lesion or lymphoepithelial carcinoma, represents a poorly differentiated salivary carcinoma with a prominent lymphoid stroma. Most of these lesions have occurred in Inuit and Asian populations and appear to have arisen de novo as carcinomas; however, some cases (especially in non-Inuits) have been reported to develop from a prior benign lymphoepithelial lesion. The Epstein-Barr virus (EBV) has been strongly associated in the cause of malignant lymphoepithelial lesions, especially those cases arising in Inuit and Asian populations. The 5-year survival rate has been reported to range from 70% to 85%.

SJÖGREN SYNDROME

Sjögren syndrome is a chronic, systemic autoimmune disorder that principally involves the salivary and lacrimal glands, resulting in xerostomia (dry mouth) and xerophthalmia (dry eyes). The effects on the eye often are called keratoconjunctivitis sicca (sicca means “dry”), and the clinical presentation of both xerostomia and xerophthalmia is also sometimes called the sicca syndrome. Two forms of the disease are recognized:

1. Primary Sjögren syndrome (sicca syndrome alone; no other autoimmune disorder is present)

2. Secondary Sjögren syndrome (the patient manifests sicca syndrome in addition to another associated autoimmune disease)

The cause of Sjögren syndrome is unknown. Although it is not a hereditary disease per se, there is evidence of a genetic influence. Examples of Sjögren syndrome have been reported in twins or in two or more members of the same family. Relatives of affected patients have an increased frequency of other autoimmune diseases. In addition, certain histocompatibility antigens (HLAs) are found with greater frequency in patients with Sjögren syndrome. HLA-DRw52 is associated with both forms of the disease; HLA-B8 and HLA-DR3 are seen with increased frequency in the primary form of the disease. Researchers have suggested that viruses, such as Epstein-Barr virus (EBV) or human T-cell lymphotropic virus, may play a pathogenetic role in Sjögren syndrome, but evidence for this is still speculative.

CLINICAL AND RADIOGRAPHIC FEATURES: Sjögren syndrome is not a rare condition. Although the exact prevalence depends on the clinical criteria used, current estimates place the population prevalence at 0.5%, with a 9:1 female-to-male ratio. It is seen predominantly in middle-aged adults, but rare examples have been described in children. The revised classification criteria suggested by the American-European Consensus Group are shown in Box 11-2.

When the condition is associated with another connective tissue disease, it is called secondary Sjögren syndrome. It can be associated with almost any other autoimmune disease, but the most common associated disorder is rheumatoid arthritis. About 15% of patients with rheumatoid arthritis have Sjögren syndrome. In addition, secondary Sjögren syndrome may develop in 30% of patients with systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE).

The principal oral symptom is xerostomia, which is caused by decreased salivary secretions; however, the severity of this dryness can vary widely from patient to patient. The saliva may appear frothy, with a lack of the usual pooling saliva in the floor of the mouth. Affected patients may complain of difficulty in swallowing, altered taste, or difficulty in wearing dentures. The tongue often becomes fissured and exhibits atrophy of the papillae (Fig. 11-24). The oral mucosa may be red and tender, usually as a result of secondary candidiasis. Related denture sore mouth and angular cheilitis are common. The lack of salivary cleansing action predisposes the patient to dental decay, especially cervical caries.

From one third to one half of patients have diffuse, firm enlargement of the major salivary glands during the course of their disease (Fig. 11-25). This swelling is usually bilateral, may be nonpainful or slightly tender, and may be intermittent or persistent in nature. The greater the severity of the disease, the greater the likelihood of this salivary enlargement. In addition, the reduced salivary flow places these individuals at increased risk for retrograde bacterial sialadenitis.

Fig. 11-25 Sjögren syndrome. Benign lymphoepithelial lesion of the parotid gland. (Courtesy of Dr. David Schaffner.)

Although it is not diagnostic, sialographic examination often reveals punctate sialectasia and lack of normal arborization of the ductal system, typically demonstrating a “fruit-laden, branchless tree” pattern (Fig. 11-26). Scintigraphy with radioactive technetium-99m pertechnetate characteristically shows decreased uptake and delayed emptying of the isotope.

Fig. 11-26 Sjögren syndrome. Parotid sialogram demonstrating atrophy and punctate sialectasia (“fruit-laden, branchless tree”). (Courtesy of Dr. George Blozis.)

The term keratoconjunctivitis sicca describes not only the reduced tear production by the lacrimal glands but also the pathologic effect on the epithelial cells of the ocular surface. As in xerostomia, the severity of xerophthalmia can vary widely from one patient to the next. The lacrimal inflammation causes a decrease of the aqueous layer of the tear film; however, mucin production is normal and may result in a mucoid discharge. Patients often complain of a scratchy, gritty sensation or the perceived presence of a foreign body in the eye. Defects of the ocular surface epithelium develop and can be demonstrated with rose bengal dye. Vision may become blurred, and sometimes there is an aching pain. The ocular manifestations are least severe in the morning on wakening and become more pronounced as the day progresses.

A simple means to confirm the decreased tear secretion is the Schirmer test. A standardized strip of sterile filter paper is placed over the margin of the lower eyelid, between the medial and lateral third of the lid of the unanesthetized eye, so that the tabbed end rests just inside the lower lid. By measuring the length of wetting of the filter paper, tear production can be assessed. Values less than 5 mm (after a 5-minute period) are considered diagnostic of keratoconjunctivitis sicca.

Sjögren syndrome is a systemic disease, and the inflammatory process also can affect various other body tissues. The skin is often dry, as are the nasal and vaginal mucosae. Fatigue is fairly common, and depression sometimes can occur. Other possible associated problems include lymphadenopathy, primary biliary cirrhosis, Raynaud’s phenomenon, interstitial nephritis, interstitial lung fibrosis, vasculitis, and peripheral neuropathies.

LABORATORY VALUES: In patients with Sjögren syndrome, the erythrocyte sedimentation rate is high and serum immunoglobulin (Ig) levels, especially IgG, typically are elevated. A variety of autoantibodies can be produced, and although none of these is specifically diagnostic, their presence can be another helpful clue to the diagnosis. A positive rheumatoid factor (RF) is found in approximately 60% of cases, regardless of whether the patient has rheumatoid arthritis. Antinuclear antibodies (ANAs) are also present in 75% to 85% of patients. Two particular nuclear autoantibodies—anti-SS-A (anti-Ro) and anti-SS-B (anti-La)—may be found, especially in patients with primary Sjögren syndrome. Anti-SS-A antibodies have been detected in approximately 40% of patients, whereas anti-SS-B antibodies have been discovered in about 25% of these individuals. Occasionally, salivary duct autoantibodies also can be demonstrated, usually in secondary Sjögren syndrome. However, because these are infrequent in primary cases, they are believed to occur as a secondary phenomenon (rather than playing a primary role in pathogenesis).

HISTOPATHOLOGIC FEATURES: The basic microscopic finding in Sjögren syndrome is a lymphocytic infiltration of the salivary glands, with destruction of the acinar units. If the major glands are enlarged, then microscopic examination usually shows progression to a lymphoepithelial lesion (see page 466), with characteristic epimyoepithelial islands in a background lymphoid stroma. Lymphocytic infiltration of the minor glands also occurs, although epimyoepithelial islands are rarely seen in this location.

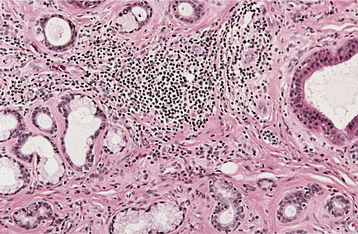

Biopsy of the minor salivary glands of the lower lip has become a useful test in the diagnosis of Sjögren syndrome. A 1.5- to 2.0-cm incision is made on clinically normal lower labial mucosa, parallel to the vermilion border and lateral to the midline, allowing the harvest of five or more accessory glands. These glands then are examined histopathologically for the presence of focal chronic inflammatory aggregates (50 or more lymphocytes and plasma cells). These aggregates should be adjacent to normal-appearing acini and should be found consistently in most of the glands in the specimen. The finding of more than one focus of 50 or more cells within a 4-mm2 area of glandular tissue is considered supportive of the diagnosis of Sjögren syndrome (Fig. 11-27). The greater the number of foci (up to 10 or confluent foci) is, the greater is the correlation with this diagnosis. The focal nature of this chronic inflammation among otherwise normal acini is a highly suggestive pattern; in contrast, the finding of scattered inflammation with ductal dilatation and fibrosis (chronic sclerosing sialadenitis) does not support the diagnosis of Sjögren syndrome.

Although labial salivary gland biopsy has become a widely used test in the diagnosis of Sjögren syndrome, it is not 100% reliable. Some patients diagnosed with Sjögren syndrome will show no significant labial gland inflammation; conversely, examination of labial glands removed incidentally from non-Sjögren patients sometimes will show focal lymphocytic infiltrates. Sjögren syndrome patients who smoke have been shown to have a significantly lower frequency of abnormal lymphocytic foci scores in their labial gland specimens. It also is important that a pathologist experienced in the analysis of these specimens examines the labial gland biopsies. One study showed that slightly more than half of labial gland specimens required a revised diagnosis after being reviewed by a second pathologist.

Other authors have advocated incisional biopsy of the parotid gland through a posterior auricular approach instead of a labial salivary gland biopsy. One study has shown this technique to be more sensitive in demonstrating inflammatory changes that support the diagnosis of Sjögren syndrome; however, other authors think that this technique confers no increased benefit over labial gland biopsy. Parotid biopsy may enable the clinician to evaluate an enlarged gland for the development of lymphoma and rule out the possibility of sialadenosis or sarcoidosis.

TREATMENT AND PROGNOSIS: The treatment of the patient with Sjögren syndrome is mostly supportive. The dry eyes are best managed by periodic use of artificial tears. In addition, attempts can be made to conserve the tear film through the use of sealed glasses to prevent evaporation. Sealing the lacrimal punctum at the inner margin of the eyelids also can be helpful by blocking the normal drainage of any lacrimal secretions into the nose.

Artificial salivas are available for the treatment of xerostomia; sugarless candy or gum can help to keep the mouth moist. Symptoms often can be relieved by the use of oral hygiene products that contain lactoperoxidase, lysozyme, and lactoferrin (e.g., Biotene toothpaste and mouth rinse, Oralbalance gel). Sialagogue medications, such as pilocarpine and cevimeline, can be useful to stimulate salivary flow if enough functional salivary tissue still remains. Medications known to diminish secretions should be avoided, if at all possible. Because of the increased risk of dental caries, daily fluoride applications may be indicated in dentulous patients. Antifungal therapy often is needed to treat secondary candidiasis.

Patients with Sjögren syndrome have an increased risk for lymphoma, up to 40 times higher than the normal population. These tumors may arise initially within the salivary glands or within lymph nodes. With the advent of modern molecular pathology techniques to detect B-cell monoclonality (e.g., in situ hybridization, polymerase chain reaction [PCR]), many salivary gland infiltrates formerly thought to represent benign lymphoepithelial lesions are now being diagnosed as lymphomas. These tumors are predominantly low-grade non-Hodgkin’s B-cell lymphomas of the mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue (i.e., MALT lymphomas), although occasionally, high-grade MALT lymphomas can develop that demonstrate more aggressive behavior. The detection of immunoglobulin gene rearrangements in labial salivary gland biopsies may prove to be a useful marker for predicting the development of lymphoma.

SIALADENOSIS (SIALOSIS)

Sialadenosis is an unusual noninflammatory disorder characterized by salivary gland enlargement, particularly involving the parotid glands. The condition frequently is associated with an underlying systemic problem, which may be endocrine, nutritional, or neurogenic in origin (Box 11-3). The best known of these conditions include diabetes mellitus, general malnutrition, alcoholism, and bulimia.

These conditions are believed to result in dysregulation of the autonomic innervation of the salivary acini, causing an aberrant intracellular secretory cycle. This leads to excessive accumulation of secretory granules, with marked enlargement of the acinar cells.

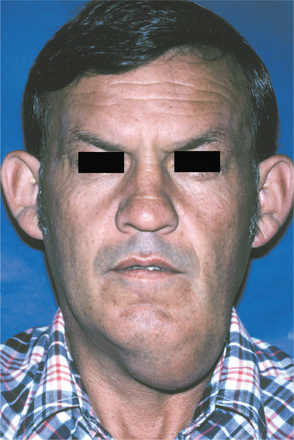

CLINICAL AND RADIOGRAPHIC FEATURES: Sialadenosis usually appears as a slowly evolving swelling of the parotid glands, which may or may not be painful (Fig. 11-28). The condition is usually bilateral, but it also can be unilateral. In some patients, the submandibular glands may be affected, but involvement of minor salivary glands is distinctly rare. Decreased salivary secretion may occur. Sialography demon-strates a “leafless tree” pattern, which is thought to be caused by compression of the finer ducts by hypertrophic acinar cells.

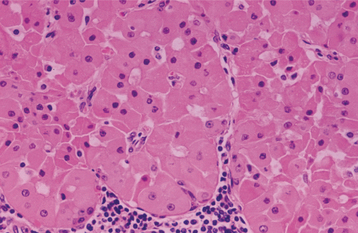

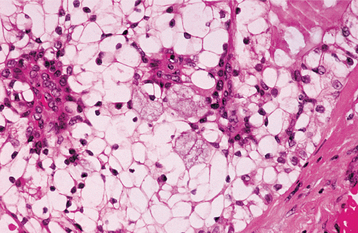

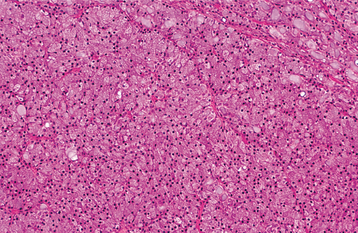

HISTOPATHOLOGIC FEATURES: Microscopic examination reveals hypertrophy of the acinar cells, sometimes two to three times greater than normal size. The nuclei are displaced to the cell base, and the cytoplasm is engorged with zymogen granules. In cases associated with long-standing diabetes or alcoholism, there may be acinar atrophy and fatty infiltration. Significant inflammation is not observed.

TREATMENT AND PROGNOSIS: The clinical management of sialadenosis is often unsatisfactory because it is closely related to the control of the underlying cause. Mild examples may cause few pro-blems. If the swelling becomes a cosmetic concern, then partial parotidectomy can be performed. Pilocarpine recently has been reported to be beneficial in reducing salivary gland enlargement in bulimic patients.

ADENOMATOID HYPERPLASIA OF THE MINOR SALIVARY GLANDS

CLINICAL FEATURES: Adenomatoid hyperplasia is a rare lesion of the minor salivary glands characterized by localized swelling that mimics a neoplasm. This pseudotumor most often occurs on the hard or soft palate, although it also has been reported in other oral minor salivary gland sites. The pathogenesis of adenomatoid hyperplasia is uncertain, but it has been speculated that local trauma may play a role. It is most common in the fourth to sixth decades of life. Most examples present as sessile, painless masses that may be soft or firm to palpation. They usually are normal in color, although a few lesions are red or bluish.

HISTOPATHOLOGIC FEATURES: Microscopic examination demonstrates lobular aggregates of relatively normal-appearing mucous acini that are greater in number than normally would be found in the area. These glands also sometimes appear to be increased in size. In some instances, the glands are situated close to the mucosal surface. Chronic inflammation occasionally is seen, but it usually is mild and localized.

NECROTIZING SIALOMETAPLASIA

Necrotizing sialometaplasia is an uncommon, locally destructive inflammatory condition of the salivary glands. Although the cause is uncertain, most authors believe it is the result of ischemia of the salivary tissue that leads to local infarction. The importance of this lesion rests in the fact that it mimics a malignant process, both clinically and microscopically.

A number of potential predisposing factors have been suggested, including the following:

Researchers have suggested that these factors may play a role in compromising the blood supply to the involved glands, resulting in ischemic necrosis. However, many cases occur without any known predisposing factors.

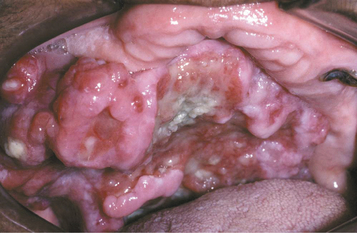

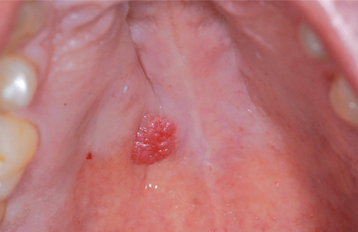

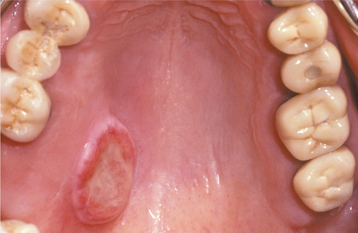

CLINICAL FEATURES: Necrotizing sialometaplasia most frequently develops in the palatal salivary glands; more than 75% of all cases occur on the posterior palate. The hard palate is affected more often than the soft palate. About two thirds of palatal cases are unilateral, with the rest being bilateral or midline in location. Necrotizing sialometaplasia also has been reported in other minor salivary gland sites and, occasionally, in the parotid gland. The submandibular and sublingual glands are rarely affected. Although it can occur at almost any age, necrotizing sialometaplasia is most common in adults; the mean age of onset is 46 years. Males are affected nearly twice as often as females.

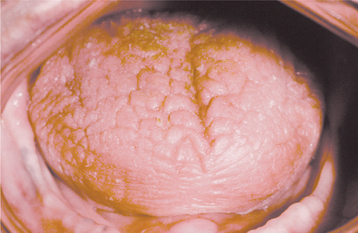

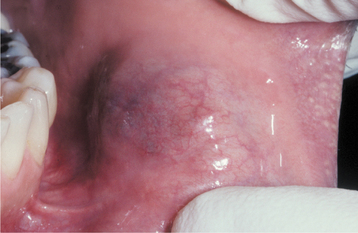

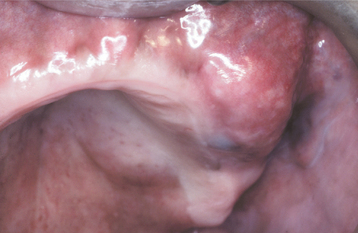

The condition appears initially as a nonulcerated swelling, often associated with pain or paresthesia (Fig. 11-29). Within 2 to 3 weeks, necrotic tissue sloughs out, leaving a craterlike ulcer that can range from less than 1 cm to more than 5 cm in diameter (Fig. 11-30). The patient may report that “a part of my palate fell out.” At this point, the pain often subsides. In rare instances, there can be destruction of the underlying palatal bone.

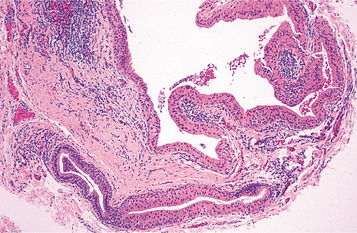

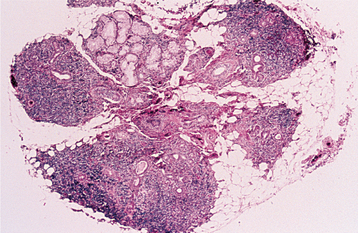

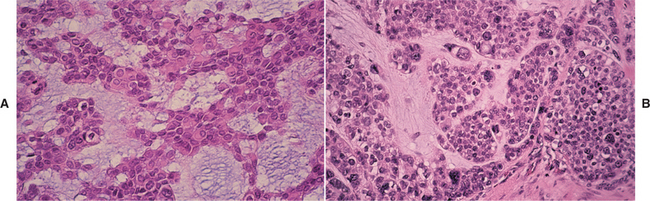

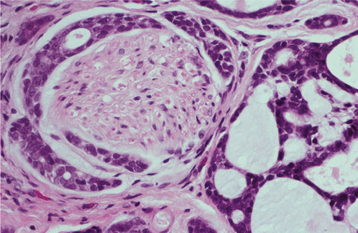

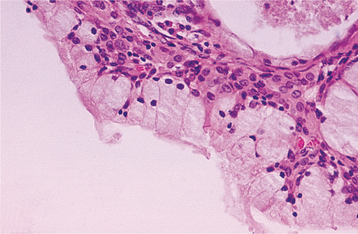

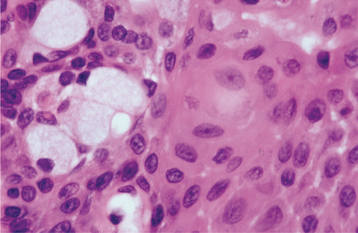

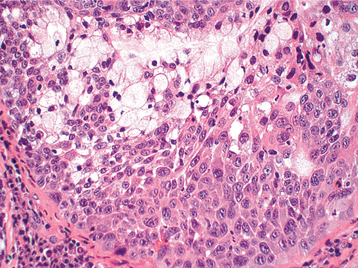

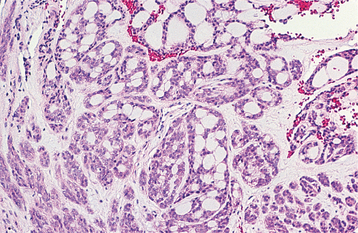

HISTOPATHOLOGIC FEATURES: The microscopic appearance of necrotizing sialometaplasia is characterized by acinar necrosis in early lesions, followed by associated squamous metaplasia of the salivary ducts (Fig. 11-31). Although the mucous acinar cells are necrotic, the overall lobular architecture of the involved glands is still preserved—a helpful histopathologic clue. There may be liberation of mucin, with an associated inflammatory response. The squamous metaplasia of the salivary ducts can be striking and produce a pattern that is easily misdiagnosed as squamous cell carcinoma or mucoepidermoid carcinoma. The frequent association of pseudoepitheliomatous hyperplasia of the overlying epithelium may further compound this mistaken impression. In most cases, however, the squamous proliferation has a bland cytologic appearance.

TREATMENT AND PROGNOSIS: Because of the worrisome clinical presentation of necrotizing sialometaplasia, biopsy usually is indicated to rule out the possibility of malignant disease. Once the diagnosis has been established, no specific treatment is indicated or necessary. The lesion typically resolves on its own accord, with an average healing time of 5 to 6 weeks.

Salivary Gland Tumors

Tumors of the salivary glands constitute an important area in the field of oral and maxillofacial pathology. Although such tumors are uncommon, they are by no means rare. The annual incidence of salivary gland tumors around the world ranges from about 1.0 to 6.5 cases per 100,000 people. Although soft tissue neoplasms (e.g., hemangioma), lymphoma, and metastatic tumors can occur within the salivary glands, the discussion in this chapter is limited to primary epithelial neoplasms.

An often-bewildering array of different salivary tumors has been identified and categorized. In addition, the classification scheme is a dynamic one that changes as clinicians learn more about these lesions. Box 11-4 includes most of the currently recognized tumors. Some of the tumors on this list are not specifically discussed because their rarity places them outside the scope of this text.

A number of investigators have published their findings on salivary gland neoplasia, but a comparison of these studies is often difficult. Some studies have been limited to only the major glands or have not included all the minor salivary gland sites. In addition, the ever-evolving classification system makes an evaluation of some older studies difficult, especially when researchers attempt to compare them with more recent analyses. (For example, the polymorphous low-grade adenocarcinoma was first identified in 1983, but clinicians now recognize that it is one of the more common malignancies in the minor glands.) Notwithstanding these difficulties, it is still helpful to compare these studies because they provide a good overview of salivary neoplasia in general. An evaluation of various studies shows fairly consistent trends (with minor variations) with regard to salivary gland tumors.

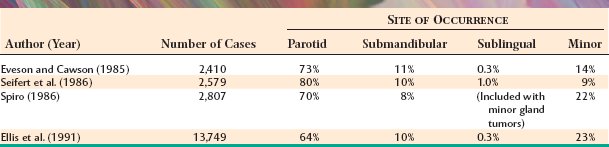

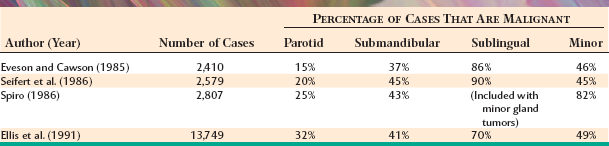

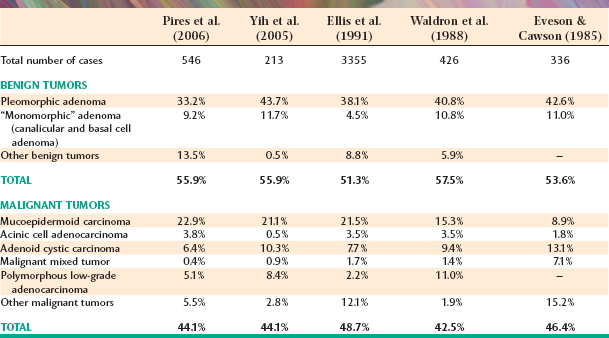

Tables 11-3 and 11-4 summarize four large series of primary epithelial salivary gland tumors, analyzed by sites of occurrence and frequency of malignancy, respectively. Some variations between studies may represent differences in diagnostic criteria, geographic differences, or referral bias in the cases seen. (Some centers may tend to see more malignant tumors on referral from other sources.)

The most common site for salivary gland tumors is the parotid gland, accounting for 64% to 80% of all cases. Fortunately, a relatively low percentage of paro-tid tumors are malignant, ranging from 15% to 32%. Overall, it can be stated that two thirds to three quarters of all salivary tumors occur in the parotid gland, and two thirds to three quarters of these parotid tumors are benign.

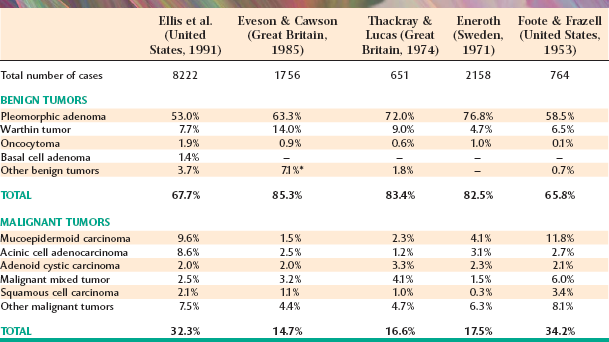

Table 11-5 summarizes five large, well-known series of parotid neoplasms. The pleomorphic adenoma is overwhelmingly the most common tumor (53% to 77% of all cases in the parotid gland). Warthin tumors are also fairly common; they account for 6% to 14% of cases. A variety of malignant tumors occur, with the mucoepidermoid carcinoma appearing to be the most frequent overall. However, two studies from Great Britain show a significantly lower prevalence of this tumor, possibly indicative of a geographic difference, especially compared with reports of cases from the United States.

From 8% to 11% of all salivary tumors occur in the submandibular gland, but the frequency of malignancy in this gland is almost double that of the parotid gland, ranging from 37% to 45%. However, as shown in Table 11-6, the pleomorphic adenoma is still the most common tumor and makes up 44% to 68% of all neoplasms. Unlike its occurrence in the parotid gland, the Warthin tumor is unusual in the submandibular gland, making up no more than 1% to 2% of all tumors. Adenoid cystic carcinoma is the most common malignancy, ranging from 12% to 27% of all cases.

Tumors of the sublingual gland are rare, comprising no more than 1% of all salivary neoplasms. However, 70% to 90% of sublingual tumors are malignant.

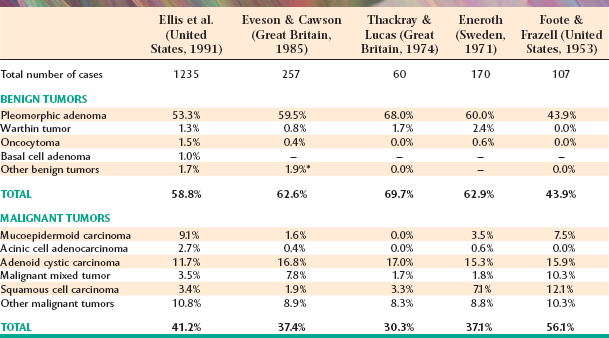

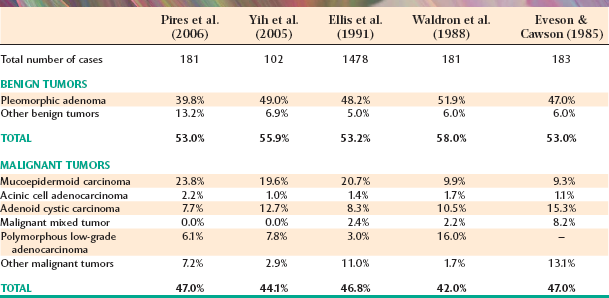

Tumors of the various smaller minor salivary glands make up 9% to 23% of all tumors, which makes this group the second most common site for salivary neoplasia. Table 11-7 summarizes the findings of five large surveys of minor gland tumors. Unfortunately, a relatively high proportion (almost 50%) of these have been malignant in most studies. Excluding rare sublingual tumors, it can be stated that the smaller the gland is, the greater is the likelihood of malignancy for a salivary gland tumor.

As observed in the major glands, the pleomorphic adenoma is the most common minor gland tumor and accounts for about 40% of all cases. Mucoepidermoid carcinoma and adenoid cystic carcinoma generally have been considered the two most common malignancies, although polymorphous low-grade adenocarcinoma also is becoming recognized as one of the more common minor gland tumors.

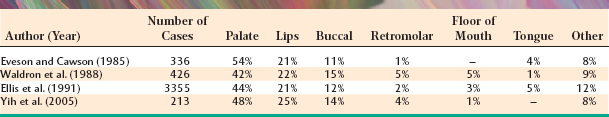

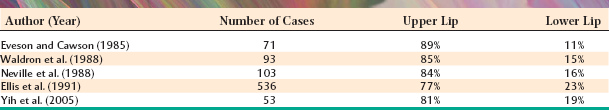

The palate is the most frequent site for minor salivary gland tumors, with 42% to 54% of all cases found there (Table 11-8). Most of these occur on the posterior lateral hard or soft palate, which have the greatest concentration of glands. Table 11-9 shows the relative prevalence of various tumors on the palate. The lips are the second most common location for minor gland tumors (21% to 25% of cases), followed by the buccal mucosa (11% to 15% of cases). Labial tumors are significantly more common in the upper lip, which accounts for 77% to 89% of all lip tumors (Table 11-10). Although mucoceles are commonly found on the lower lip, this is a surprisingly rare site for salivary gland tumors.

Significant differences in the percentage of malignancies and the relative frequency of various tumors can be noted for different minor salivary gland sites. As shown in Table 11-11, 38% to 50% of tumors of the palate and buccal mucosa sites are malignant, similar to the overall prevalence of malignancy in all minor salivary gland sites combined. In the upper lip, however, only 5% to 25% of tumors are malignant because of the high prevalence of the canalicular adenoma, which has a special affinity for this location. In contrast, although lower lip tumors are uncommon, 50% to 90% are malignant (mostly mucoepidermoid carcinomas). Up to 91% of retromolar tumors are malignant, also because of a predominance of mucoepidermoid carcinomas. Unfortunately, most tumors in the floor of the mouth and tongue are also malignant.

PLEOMORPHIC ADENOMA (BENIGN MIXED TUMOR)

The pleomorphic adenoma, or benign mixed tumor, is easily the most common salivary neoplasm. It accounts for 53% to 77% of parotid tumors, 44% to 68% of submandibular tumors, and 33% to 43% of minor gland tumors.

Pleomorphic adenomas are derived from a mixture of ductal and myoepithelial elements. A remarkable microscopic diversity can exist from one tumor to the next, as well as in different areas of the same tumor. The terms pleomorphic adenoma and mixed tumor both represent attempts to describe this tumor’s unusual histopathologic features, but neither term is entirely accurate. Although the basic tumor pattern is highly variable, rarely are the individual cells actually pleomorphic. (However, focal minor atypia is acceptable.) Likewise, although the tumor often has a prominent mesenchyme-appearing “stromal” component, it is not truly a mixed neoplasm that is derived from more than one germ layer.

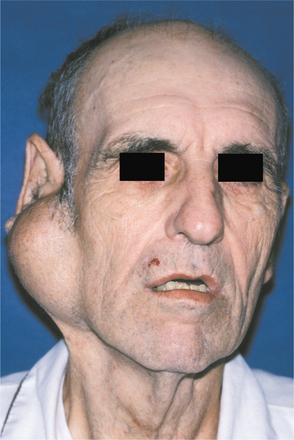

CLINICAL AND RADIOGRAPHIC FEATURES: Regardless of the site of origin, the pleomorphic adenoma typically appears as a painless, slowly growing, firm mass (Figs. 11-32 to 11-34). The patient may be aware of the lesion for many months or years before seeking a diagnosis. The tumor can occur at any age but is most common in young and middle-aged adults between the ages of 30 and 60. Pleomorphic adenoma is also the most common primary salivary gland tumor to develop during childhood. There is a slight female predilection.

Fig. 11-32 Pleomorphic adenoma. Small, firm nodule located below the left ear in the parotid gland. (Courtesy of Dr. Mike Hansen.)

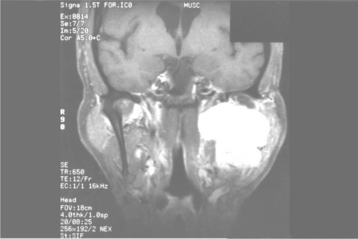

Most pleomorphic adenomas of the parotid gland occur in the superficial lobe and present as a swelling overlying the mandibular ramus in front of the ear. Facial nerve palsy and pain are rare. Initially, the tumor is movable but becomes less mobile as it grows larger. If neglected, then the lesion can grow to grotesque proportions. About 10% of parotid mixed tumors develop within the deep lobe of the gland beneath the facial nerve (Fig. 11-35). Sometimes these lesions grow in a medial direction between the ascending ramus and stylomandibular ligament, resulting in a dumbbell-shaped tumor that appears as a mass of the lateral pharyngeal wall or soft palate. On rare occasions, bilateral pleomorphic adenomas of the parotid glands have been reported, developing in either a synchronous or metachronous fashion.

Fig. 11-35 Pleomorphic adenoma. T1-weighted, fat-suppressed, contrast-enhanced coronal magnetic resonance image (MRI) of a tumor of the deep lobe of the parotid gland. (Courtesy of Dr. Joel Curé.)

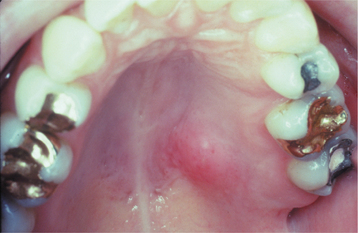

The palate is the most common site for minor gland mixed tumors, accounting for approximately 50% of intraoral examples. This is followed by the upper lip (27%) and buccal mucosa (17%). Palatal tumors almost always are found on the posterior lateral aspect of the palate, presenting as smooth-surfaced, dome-shaped masses (Figs. 11-36 and 11-37). If the tumor is traumatized, then secondary ulceration may occur. Because of the tightly bound nature of the hard palate mucosa, tumors in this location are not movable, although those in the lip or buccal mucosa frequently are mobile.

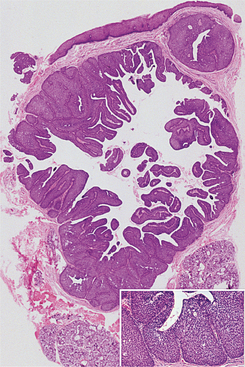

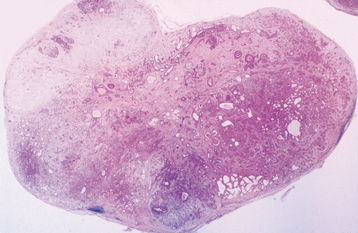

HISTOPATHOLOGIC FEATURES: The pleomorphic adenoma is typically a well-circumscribed, encapsulated tumor (Fig. 11-38). However, the capsule may be incomplete or show infiltration by tumor cells. This lack of complete encapsulation is more common for minor gland tumors, especially along the superficial aspect of palatal tumors beneath the epithelial surface.

Fig. 11-38 Pleomorphic adenoma. Low-power view showing a well-circumscribed, encapsulated tumor mass. Even at this power, the variable microscopic pattern of the tumor is evident.

The tumor is composed of a mixture of glan-dular epithelium and myoepithelial cells within a mesenchyme-like background. The ratio of the epithelial elements and the mesenchyme-like component is highly variable among different tumors. Some tumors may consist almost entirely of background “stroma.” Others are highly cellular with little background alteration.

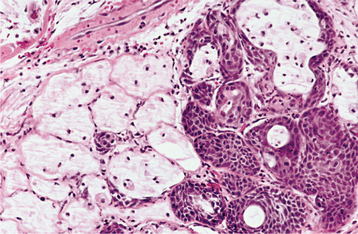

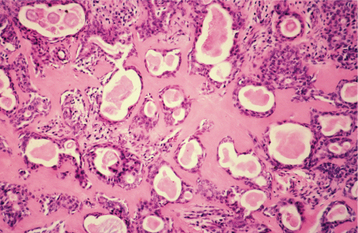

The epithelium often forms ducts and cystic structures or may occur as islands or sheets of cells. Keratinizing squamous cells and mucus-producing cells also can be seen. Myoepithelial cells often make up a large percentage of the tumor cells and have a variable morphology, sometimes appearing angular or spindled. Some myoepithelial cells are rounded and demonstrate an eccentric nucleus and eosinophilic hyalinized cytoplasm, thus resembling plasma cells (Fig. 11-39). These characteristic plasmacytoid myoepithelial cells are more prominent in tumors arising in the minor glands.

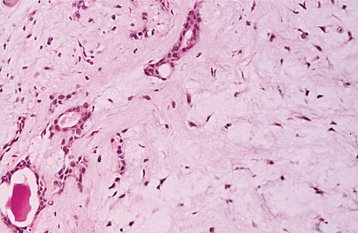

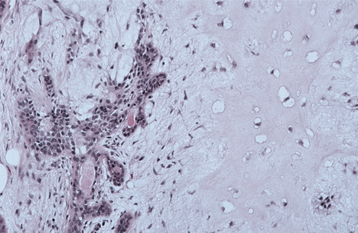

The highly characteristic “stromal” changes are believed to be produced by the myoepithelial cells. Extensive accumulation of mucoid material may occur between the tumor cells, resulting in a myxomatous background (Fig. 11-40). Vacuolar degeneration of cells in these areas can produce a chondroid appearance (Fig. 11-41). In many tumors, the stroma exhibits areas of an eosinophilic, hyalinized change (Fig. 11-42). At times, fat or osteoid also is seen.

Fig. 11-40 Pleomorphic adenoma. Ductal structures (left) with associated myxomatous background (right).

Fig. 11-41 Pleomorphic adenoma. Chondroid material (right) with adjacent ductal epithelium and myoepithelial cells.

Fig. 11-42 Pleomorphic adenoma. Many of the ducts and myoepithelial cells are surrounded by a hyalinized, eosinophilic background alteration.

Occasionally, salivary tumors are seen that are composed almost entirely of myoepithelial cells with no ductal elements. Such tumors often are called myoepitheliomas, although they probably represent one end of the spectrum of mixed tumors.

TREATMENT AND PROGNOSIS: Pleomorphic adenomas are best treated by surgical excision. For lesions in the superficial lobe of the parotid gland, superficial parotidectomy with identification and preservation of the facial nerve is recommended. Local enucleation should be avoided because the entire tumor may not be removed or the capsule may be violated, resulting in seeding of the tumor bed. For tumors of the deep lobe of the parotid, total parotidectomy is usually necessary, also with preservation of the facial nerve, if possible. Submandibular tumors are best treated by total removal of the gland with the tumor. Tumors of the hard palate usually are excised down to periosteum, including the overlying mucosa. In other oral sites the lesion often enucleates easily through the incision site.

With adequate surgery the prognosis is excellent, with a cure rate of more than 95%. The risk of recurrence appears to be lower for tumors of the minor glands. Conservative enucleation of parotid tumors often results in recurrence, with management of these cases made difficult as a result of multifocal seeding of the primary tumor bed. In such cases, multiple recurrences are not unusual. Tumors with a predominantly myxoid appearance are more susceptible to recur than those with other microscopic patterns.

Malignant degeneration is a potential complication, resulting in a carcinoma ex pleomorphic adenoma (see page 492). The risk of malignant transformation is probably small, but it may occur in as many as 5% of all cases.

ONCOCYTOMA (OXYPHILIC ADENOMA)

The oncocytoma is a benign salivary gland tumor composed of large epithelial cells known as oncocytes. The prefix onco- is derived from the Greek word onkoustai, which means to swell. The swollen granular cytoplasm of oncocytes is due to excessive accumulation of mitochondria. Focal oncocytic metaplasia of salivary ductal and acinar cells is a common finding that is related to patient age; oncocytes are uncommon in persons younger than 50, but they can be found in almost all individuals by age 70. In addition to salivary glands, oncocytes have been identified in a number of other organs, especially the thyroid, parathyroid, and kidney. The oncocytoma is a rare neoplasm, representing approximately 1% of all salivary tumors.

CLINICAL FEATURES: The oncocytoma is predominantly a tumor of older adults, with a peak prevalence in the eighth decade of life. A slight female predilection has been observed but may not be significant. Oncocytomas occur primarily in the major salivary glands, especially the parotid gland, which accounts for about 85% to 90% of all cases. Oncocytomas of the minor salivary glands are exceedingly rare.

The tumor appears as a firm, slowly growing, painless mass that rarely exceeds 4 cm in diameter. Parotid oncocytomas usually are found in the superficial lobe and are clinically indistinguishable from other benign tumors. On occasion, bilateral tumors can occur, although these may represent examples of multinodular oncocytic hyperplasia (oncocytosis).

HISTOPATHOLOGIC FEATURES: The oncocytoma is usually a well-circumscribed tumor that is composed of sheets of large polyhedral cells (oncocytes), with abundant granular, eosinophilic cytoplasm (Fig. 11-43). Sometimes these cells form an alveolar or glandular pattern. The cells have centrally located nuclei that can vary from small and hyperchromatic to large and vesicular. Little stroma is present, usually in the form of thin fibrovascular septa. An associated lymphocytic infiltrate may be noted.

The granularity of the cells corresponds to an overabundance of mitochondria, which can be demonstrated by electron microscopy. These granules also can be identified on light microscopic examination with a phosphotungstic acid hematoxylin (PTAH) stain. The cells also contain glycogen, as evidenced by their positive staining with the periodic acid-Schiff (PAS) technique but by negative PAS staining after digestion with diastase.

Oncocytomas may contain variable numbers of cells with a clear cytoplasm. In rare instances, these clear cells may compose most of the lesion and create difficulty in distinguishing the tumor from low-grade salivary clear cell adenocarcinoma or metastatic renal cell carcinoma.

TREATMENT AND PROGNOSIS: Oncocytomas are best treated by surgical excision. In the parotid gland, this usually entails partial parotidectomy (lobectomy) to avoid violation of the tumor capsule. The facial nerve should be preserved whenever possible. For tumors in the submandibular gland, treatment consists of total removal of the gland. Oncocytomas of the oral minor salivary glands should be removed with a small margin of normal surrounding tissue.

The prognosis after removal is good, with a low rate of recurrence. However, oncocytomas of the sinonasal glands can be locally aggressive and have been considered to be low-grade malignancies. Rare examples of histopathologically malignant oncocytomas (oncocytic carcinoma) also have been reported. These carcinomas have a relatively poor prognosis.

ONCOCYTOSIS (NODULAR ONCOCYTIC HYPERPLASIA)

Oncocytic metaplasia is the transformation of ductal and acinar cells to oncocytes. Such cells are uncommon before the age of 50; however, as people get older, occasional oncocytes are common findings in the salivary glands. Focal oncocytic metaplasia also may be a feature of other salivary gland tumors. Oncocytosis refers to both the proliferation and the accumulation of oncocytes within salivary gland tissue. It may mimic a tumor, both clinically and microscopically, but it also is considered to be a metaplastic process rather than a neoplastic one.

CLINICAL FEATURES: Oncocytosis is found primarily in the parotid gland; however, in rare instances, it may involve the submandibular or minor salivary glands. It can be an incidental finding in otherwise normal salivary gland tissue, but it may be extensive enough to produce clinical swelling. Usually the proliferation is multifocal and nodular, but sometimes the entire gland can be replaced by oncocytes (diffuse hyperplastic oncocytosis). As with other oncocytic proliferations, oncocytosis occurs most frequently in older adults.

HISTOPATHOLOGIC FEATURES: Microscopic examination usually reveals focal nodular collections of oncocytes within the salivary gland tissue. These enlarged cells are polyhedral and demonstrate abundant granular, eosinophilic cytoplasm as a result of the proliferation of mitochondria. On occasion, these cells may have a clear cytoplasm from the accumulation of glycogen (Fig. 11-44). The multifocal nature of the proliferation may be confused with that of a metastatic tumor, especially when the oncocytes are clear in appearance.

WARTHIN TUMOR (PAPILLARY CYSTADENOMA LYMPHOMATOSUM)

Warthin tumor is a benign neoplasm that occurs almost exclusively in the parotid gland. Although it is much less common than the pleomorphic adenoma, it represents the second most common benign parotid tumor, accounting for 5% to 14% of all parotid neoplasms. The name adenolymphoma also has been used for this tumor, but this term should be avoided because it overemphasizes the lymphoid component and may give the mistaken impression that the lesion is a type of lymphoma. Analyses of the epithelial and lymphoid components of the Warthin tumor have shown both to be polyclonal; this suggests that this lesion may not represent a true neoplasm but would be better classified as a tumorlike process.