Epithelial Pathology

SQUAMOUS PAPILLOMA

The squamous papilloma is a benign proliferation of stratified squamous epithelium, resulting in a papillary or verruciform mass. Presumably, this lesion is induced by the human papillomavirus (HPV). HPV comprises a large family (more than 100 types) of double-stranded DNA viruses of the papovavirus subgroup A. Research has shown that 81% of normal adults have buccal epithelial cells that contain at least one type of HPV, although case control studies using more rigorous criteria usually have shown distinct differences, with high levels of HPV in oral lesions and low levels in normal controls. The virus is capable of becoming totally integrated with the DNA of the host cell, and at least 24 types are associated with lesions of the head and neck. HPV can be identified by in situ hybridization, immu nohistochemical analysis, and polymerase chain reaction (PCR) techniques, but it is not visible with routine histopathologic staining. Viral subtypes 6 and 11 have been identified in up to 50% of oral papillomas, as compared with less than 5% in normal mucosal cells.

The exact mode of transmission is unknown. Transmission by sexual and nonsexual person-to-person contact, contaminated objects, saliva, or breast milk has been proposed. In contrast to other HPV-induced lesions, the viruses in oral squamous papillomas appear to have an extremely low virulence and infectivity rate. A latency or incubation period of 3 to 12 months has been suggested.

The squamous papilloma occurs in one of every 250 adults and makes up approximately 3% of all oral lesions submitted for biopsy. In addition, researchers have estimated that oral squamous papillomas comprise 7% to 8% of all oral masses or growths in children.

CLINICAL FEATURES: The squamous papilloma occurs with equal frequency in both men and women. Some authors have asserted that it develops predominantly in children, but epidemiologic studies indicate that it can arise at any age and, in fact, is diagnosed most often in persons 30 to 50 years of age. Sites of predilection include the tongue, lips, and soft palate, but any oral surface may be affected. This lesion is the most common of the soft tissue masses arising from the soft palate.

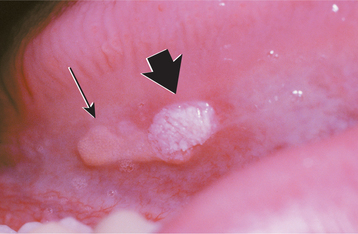

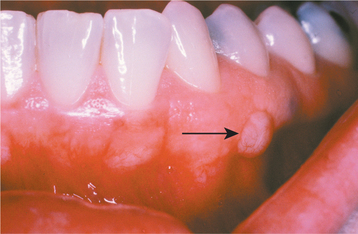

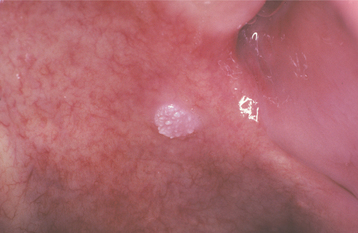

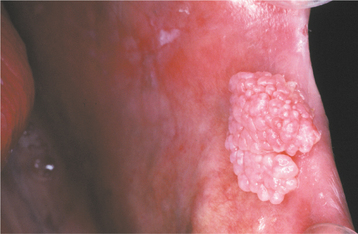

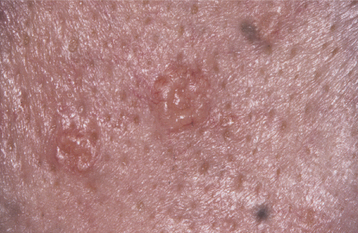

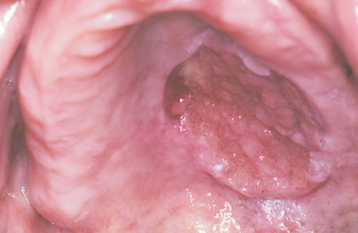

The squamous papilloma is a soft, painless, usually pedunculated, exophytic nodule with numerous fingerlike surface projections that impart a “cauliflower” or wartlike appearance (Fig. 10-1). Projections may be pointed or blunted (Figs. 10-2 and 10-3), and the lesion may be white, slightly red, or normal in color, depending on the amount of surface keratinization. The papilloma is usually solitary and enlarges rapidly to a maximum size of about 0.5 cm, with little or no change thereafter. However, lesions as large as 3.0 cm in greatest diameter have been reported.

Fig. 10-1 Squamous papilloma. An exophytic lesion of the soft palate with multiple short, white surface projections.

Fig. 10-2 Squamous papilloma. A pedunculated lingual mass with numerous long, pointed, and white surface projections. Note the smaller projections around the base of the lesion.

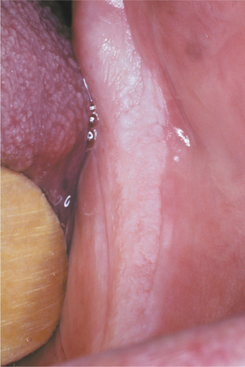

Fig. 10-3 Squamous papilloma. A pedunculated mass of the buccal commissure, exhibiting short or blunted surface projections and minimal white coloration.

It is sometimes difficult to distinguish this lesion clinically from verruca vulgaris (see page 364), condyloma acuminatum (see page 366), verruciform xanthoma (see page 372), or multifocal epithelial hyperplasia (see page 367). In addition, extensive coalescing papillary lesions (papillomatosis) of the oral mucosa may be seen in several skin disorders, including nevus unius lateris, acanthosis nigricans, and focal dermal hypoplasia (Goltz-Gorlin) syndrome. Laryngeal papillomatosis, a rare and potentially devastating disease of the larynx and hypopharynx, has two distinct types: (1) juvenile-onset and (2) adult- onset. Hoarseness is the usual presenting feature, and rapidly proliferating papillomas in the juvenile-onset type may obstruct the airway. The strongest risk factor for juvenile-onset laryngeal papillomatosis is a maternal history of genital warts; transmission of HPV infection via the birth canal, the placenta, or amniotic fluid has been hypothesized.

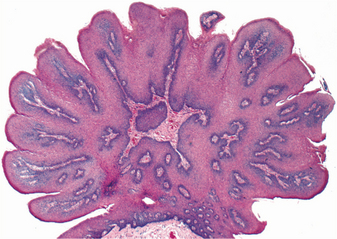

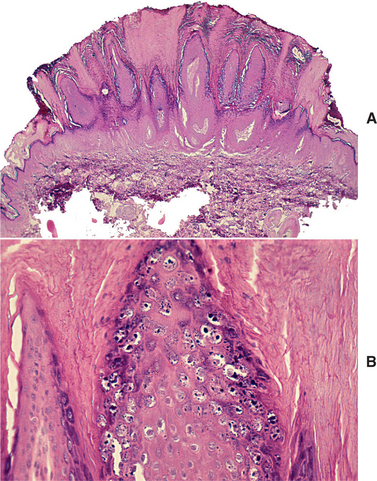

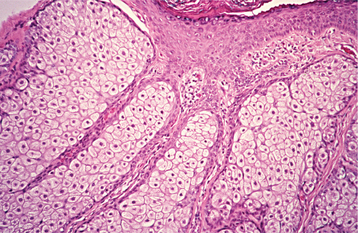

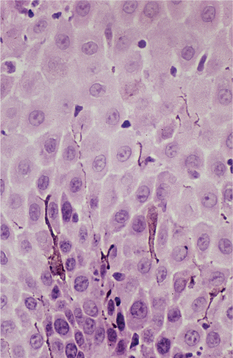

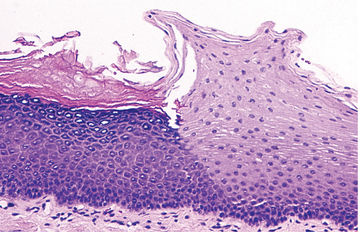

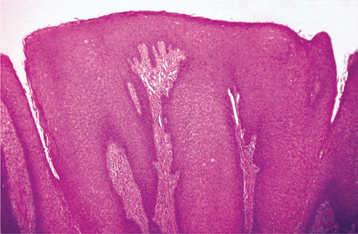

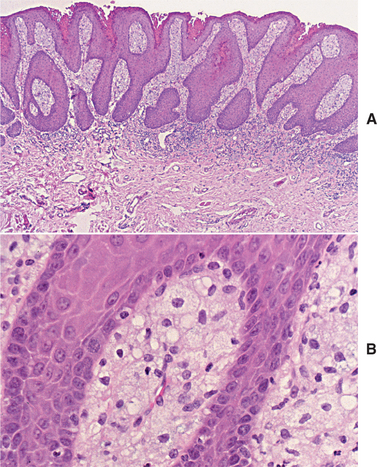

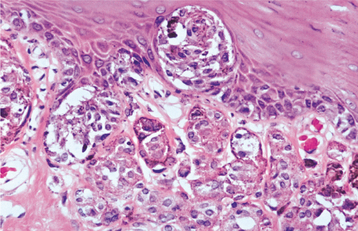

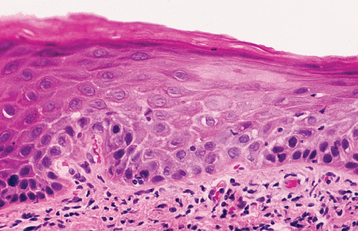

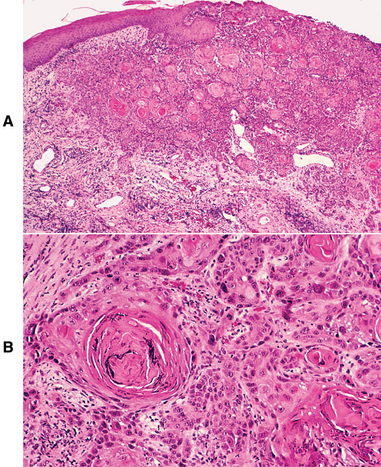

HISTOPATHOLOGIC FEATURES: The papilloma is characterized by a proliferation of keratinized stratified squamous epithelium arrayed in fingerlike projections with fibrovascular connective tissue cores (Fig. 10-4). The connective tissue cores may show inflammatory changes, depending on the amount of trauma sustained by the lesion. The keratin layer is thickened in lesions with a whiter clinical appearance, and the epithelium typically shows a normal maturation pattern. Occasional papillomas demonstrate basilar hyperplasia and mitotic activity, which can be mistaken for mild epithelial dysplasia. Koilocytes, virus-altered epithelial clear cells with small dark (pyknotic) nuclei, are sometimes seen high in the prickle cell layer.

TREATMENT AND PROGNOSIS: Conservative surgical excision, including the base of the lesion, is adequate treatment for the oral squamous papilloma, and recurrence is unlikely. Frequently, lesions have been left untreated for years with no reported transformation into malignancy, continuous enlargement, or dissemination to other parts of the oral cavity.

Although spontaneous remission is possible, juvenile-onset laryngeal papillomatosis tends to be continuously proliferative, sometimes leading to death by asphyxiation. Some investigators have noted especially aggressive behavior among cases associated with HPV type 11 infection. The papillomatosis is treated by repeated surgical debulking procedures to relieve airway obstruction. Adjuvant therapy with agents such as a-interferon may be used for cases exhibiting rapid regrowth or distant spread. Adult-onset lesions are typically less aggressive and tend to be single. Conservative surgical removal may be necessary to eliminate hoarseness from vocal cord involvement. In rare instances, squamous cell carcinoma will develop in long-standing laryngeal papillomatosis, sometimes in a smoker or a patient with a history of irradiation to the larynx.

A vaccine targeted against HPV types 6, 11, 16, and 18 has been introduced recently for the prevention of cervical cancer and genital warts. It is possible that this vaccine may prevent HPV-related lesions of the head and neck as well, such as oral squamous papilloma, laryngeal papillomatosis, and perhaps some cases of oral and oropharyngeal squamous cell carcinoma.

VERRUCA VULGARIS (COMMON WART)

Verruca vulgaris is a benign, virus-induced, focal hyperplasia of stratified squamous epithelium. One or more of the associated human papillomavirus (HPV) types 2, 4, 6, and 40 are found in virtually all examples. Verruca vulgaris is contagious and can spread to other parts of a person’s skin or mucous membranes by way of autoinoculation. It infrequently develops on oral mucosa but is extremely common on the skin.

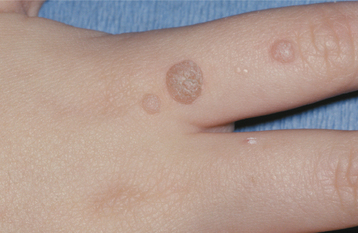

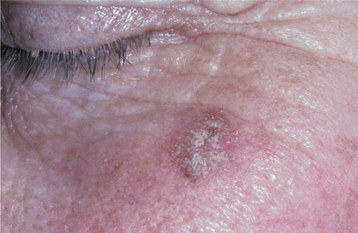

CLINICAL FEATURES: Verruca vulgaris is frequently discovered in children, but occasional lesions may arise even into middle age. The skin of the hands is usually the site of infection (Fig. 10-5). When the oral mucosa is involved, the lesions are usually found on the vermilion border, labial mucosa, or anterior tongue.

Typically, the verruca appears as a painless papule or nodule with papillary projections or a rough pebbly surface (Figs. 10-6 and 10-7). It may be pedunculated or sessile. Cutaneous lesions may be pink, yellow, or white; oral lesions are almost always white. Verruca vulgaris enlarges rapidly to its maximum size (usually <5 mm), and the size remains constant for months or years thereafter unless the lesion is irritated. Multiple or clustered lesions are common. On occasion, extreme accumulation of compact keratin may result in a hard surface projection several millimeters in height, termed a cutaneous horn or keratin horn. Other cutaneous lesions, including seborrheic keratosis (see page 374), actinic keratosis (see page 404), and squamous cell carcinoma, may also create a cutaneous horn.

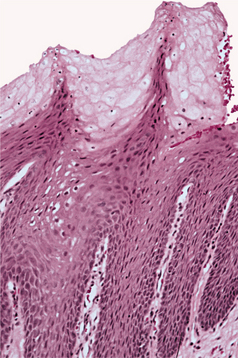

HISTOPATHOLOGIC FEATURES: The verruca vulgaris is characterized by a proliferation of hyperkeratotic stratified squamous epithelium arranged into fingerlike or pointed projections with connective tissue cores (Fig. 10-8). Chronic inflammatory cells often infiltrate the supporting connective tissue. Elongated rete ridges tend to converge toward the center of the lesion, producing a “cupping” effect. A prominent granular cell layer (hypergranulosis) exhibits coarse, clumped keratohyaline granules. Abundant koilocytes are often seen in the superficial spinous layer. Koilocytes are HPV-altered epithelial cells with perinuclear clear spaces and small, dark nuclei (pyknosis). Eosinophilic intranuclear viral inclusions are often noted within the cells of the granular layer.

TREATMENT AND PROGNOSIS: Skin verrucae are treated effectively by topical salicylic acid, topical lactic acid, or liquid nitrogen cryotherapy. Surgical excision is indicated only for cases with an atypical clinical presentation in which the diagnosis is uncertain. Skin lesions that recur or are resistant to standard therapy may be treated by alternative methods, such as intralesional bleomycin, topical or intralesional 5-fluorouracil, or photodynamic therapy.

Oral lesions are usually surgically excised, or they may be destroyed by a laser, cryotherapy, or electrosurgery. Cryotherapy induces a subepithelial blister that lifts the infected epithelium from the underlying connective tissue, allowing it to slough away. All destructive or surgical treatments should extend to include the base of the lesion.

Recurrence is seen in a small proportion of treated cases. Without treatment, verrucae do not transform into malignancy, and two thirds will disappear spontaneously within 2 years, especially in children.

CONDYLOMA ACUMINATUM (VENEREAL WART)

Condyloma acuminatum is a virus-induced proliferation of stratified squamous epithelium of the genitalia, perianal region, mouth, and larynx. One or more of the human papillomavirus (HPV) types 2, 6, 11, 53, and 54 are usually detected in the lesion. However, the high-risk types 16, 18, and 31 also may be present, especially in anogenital lesions. Condyloma is considered to be a sexually transmitted disease (STD), with lesions developing at a site of sexual contact or trauma. This lesion represents 20% of all STDs diagnosed in STD clinics and may be an indicator of sexual abuse when diagnosed in young children. In addition, studies of oral and pharyngeal HPV infection in infants have suggested that vertical transmission from mothers with genital HPV infection may occur perinatally or perhaps in utero; however, reported transmission rates have varied widely (ranging from 4% to >80%). It is not unusual for oral and anogenital condylomata to be present concurrently. The incubation period for a condyloma is 1 to 3 months from the time of sexual contact. Once present, autoinoculation to other mucosal sites is possible.

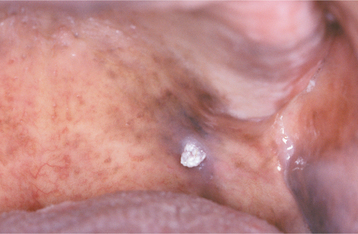

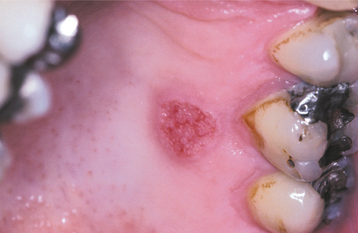

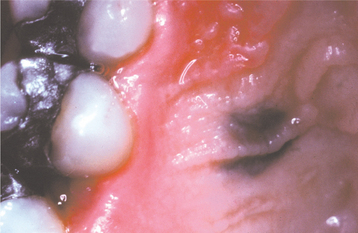

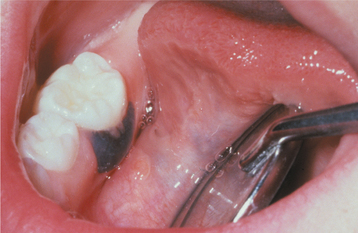

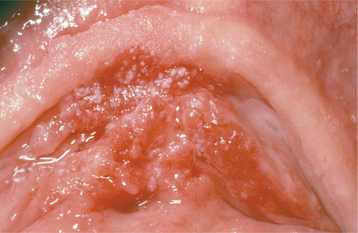

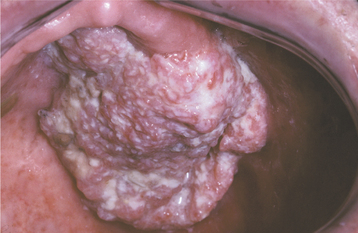

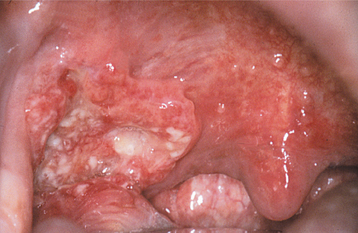

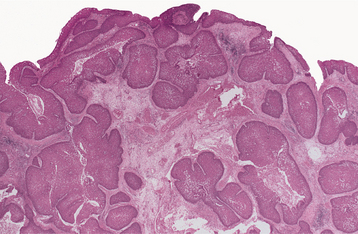

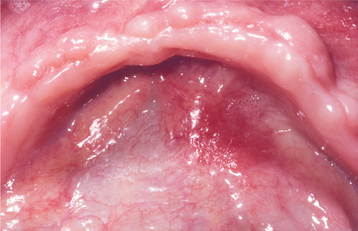

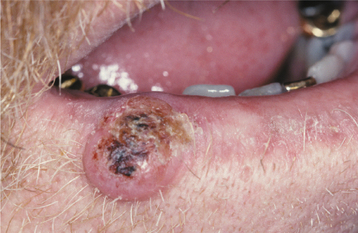

CLINICAL FEATURES: Condylomata are usually diagnosed in teenagers and young adults, but people of all ages are susceptible. Oral lesions most frequently occur on the labial mucosa, soft palate, and lingual frenum. The typical condyloma appears as a sessile, pink, well-demarcated, nontender exophytic mass with short, blunted surface projections (Fig. 10-9). The condyloma tends to be larger than the papilloma and is characteristically clustered with other condylomata. The average lesional size is 1.0 to 1.5 cm, but oral lesions as large as 3 cm have been reported.

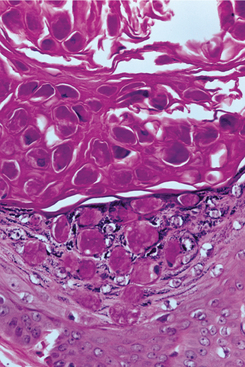

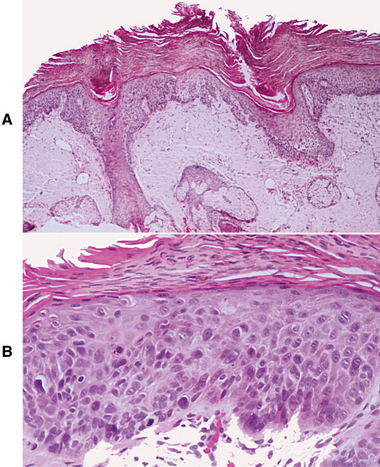

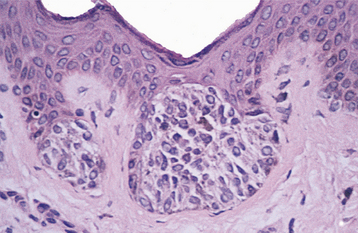

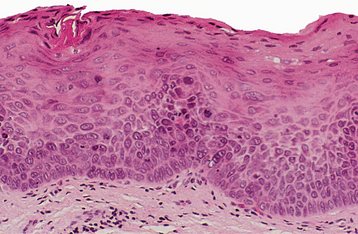

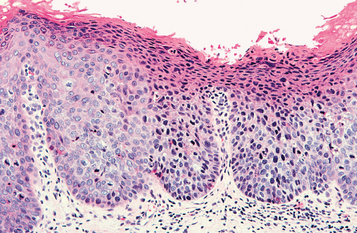

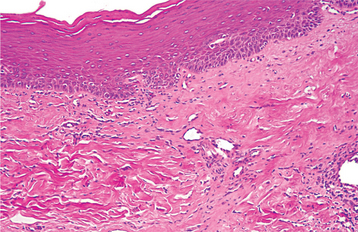

HISTOPATHOLOGIC FEATURES: Condyloma acuminatum appears as a benign proliferation of acanthotic stratified squamous epithelium with mildly keratotic papillary surface projections (Fig. 10-10). Thin connective tissue cores support the papillary epithelial projections, which are more blunted and broader than those of squamous papilloma and verruca vulgaris, imparting an appearance of keratin-filled crypts between prominences. In some cases, lesions extending from the surface mucosa to involve underlying salivary ductal epithelium have been reported; such lesions should be distinguished from salivary ductal papillomas (see page 485).

Fig. 10-10 Condyloma acuminatum. Medium-power photomicrograph showing acanthotic stratified squamous epithelium forming a blunted projection.

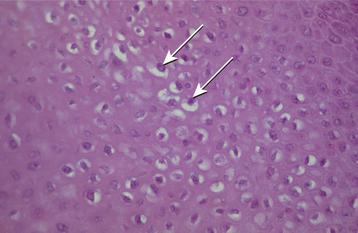

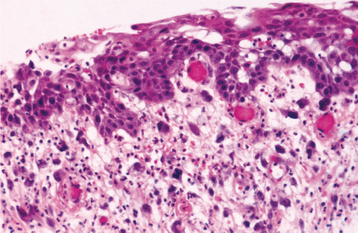

The covering epithelium is mature and differentiated, but the prickle cells often demonstrate pyknotic, crinkled (or “raisinlike”) nuclei surrounded by clear zones (koilocytes), a microscopic feature of HPV infec tion (Fig. 10-11). Koilocytes may be less prominent in oral lesions compared with genital lesions, in which case distinction from squamous papilloma may be difficult. Ultrastructural examination reveals virions within the cytoplasm or nuclei of koilocytes, and the virus also can be demonstrated by immunohistochemical analysis, in situ hybridization, and PCR techniques.

TREATMENT AND PROGNOSIS: The oral condyloma is usually treated by conservative surgical excision. Laser ablation also has been used, but this treatment has raised some question as to the airborne spread of HPV through the aerosolized microdroplets created by the vaporization of lesional tissue. Nonsurgical, patient-applied topical agents such as imiquimod or podophyllotoxin are becoming the mainstay of treatment for anogenital condylomata, although such treatments are not typically used for oral lesions. Regardless of the method used, a condyloma should be removed because it is contagious and can spread to other oral surfaces and to other persons through direct (usually sexual) contact. In the anogenital area, condylomata infected with HPV-16 or HPV-18 are associated with an increased risk of malignant transformation to squamous cell carcinoma, but this has not been demonstrated in oral lesions.

MULTIFOCAL EPITHELIAL HYPERPLASIA (HECK’S DISEASE; MULTIFOCAL PAPILLOMA VIRUS EPITHELIAL HYPERPLASIA; FOCAL EPITHELIAL HYPERPLASIA)

Multifocal epithelial hyperplasia is a virus-induced, localized proliferation of oral squamous epithelium that was first described in Native Americans and Inuit. Currently, it is known to exist in many populations and ethnic groups and is apparently produced by human papillomavirus (HPV) types 13 and 32. In some populations, as many as 39% of children are affected. The condition often affects multiple members of a given family; this familial tendency may be related to either genetic susceptibility or HPV transmission between family members. An association with the HLA-DR4 (DRB1*0404) allele was found in a recent study of Mexican patients with this condition. Lower socio-economic status, crowded living conditions, and poor hygiene appear to be additional risk factors. Multiple papillary lesions similar to multifocal epithelial hyperplasia arise with increased frequency in patients with acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS) (see page 276).

CLINICAL FEATURES: Although multifocal epithelial hyperplasia is usually a childhood condition, it occasionally affects young and middle-aged adults. Previous studies have reported either a slight female predilection or no significant gender bias. The most common sites of involvement include the labial, buccal, and lingual mucosa, but gingival, palatal, and tonsillar lesions also have been reported. In addition, involvement of the conjunctiva has been described very rarely.

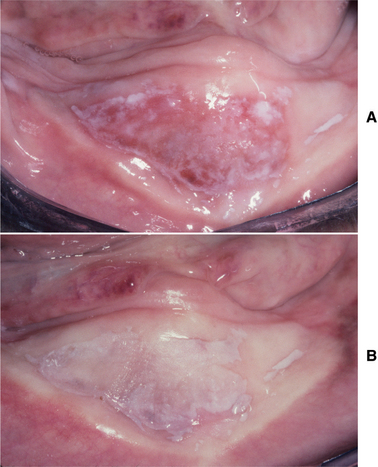

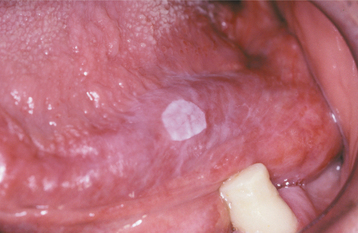

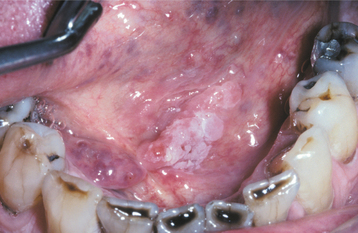

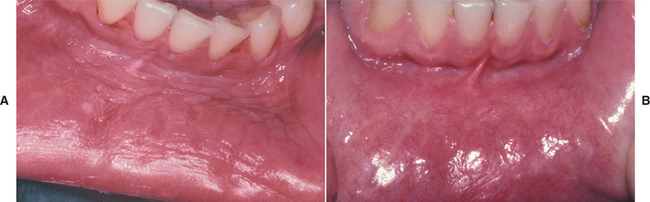

This disease typically appears as multiple soft, nontender, flattened or rounded papules, which are usually clustered and the color of normal mucosa, although they may be scattered, pale, or rarely white (Fig. 10-12). Occasional lesions show a slight papillary surface change (Fig. 10-13). Individual lesions are small (0.3 to 1.0 cm), discrete, and well demarcated, but they frequently cluster so closely together that the entire area takes on a cobblestone or fissured appearance.

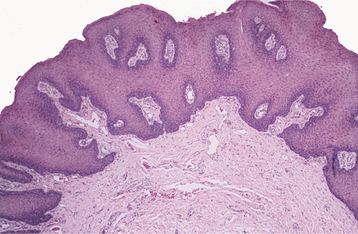

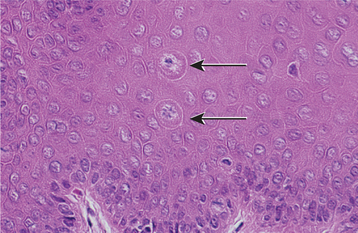

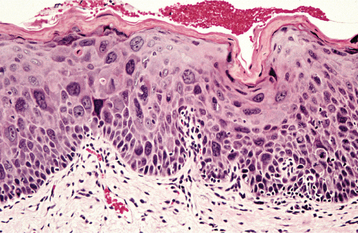

HISTOPATHOLOGIC FEATURES: The hallmark of multifocal epithelial hyperplasia is an abrupt and sometimes considerable acanthosis of the oral epithelium (Fig. 10-14). Because the thickened mucosa extends upward, not down into underlying connective tissues, the lesional rete ridges are at the same depth as the adjacent normal rete ridges. The ridges themselves are widened, often confluent, and sometimes club shaped. Some superficial keratinocytes show a koilocytic change similar to that seen in other HPV infections. Others occasionally demonstrate an altered nucleus that resembles a mitotic figure (mitosoid cell) (Fig. 10-15). Viruslike particles have been noted ultrastructurally within both the cytoplasm and the nuclei of cells within the prickle cell layer, and the presence of HPV has been demonstrated with both DNA in situ hybridization and immunohistochemical analysis.

TREATMENT AND PROGNOSIS: Spontaneous regression of multifocal epithelial hyperplasia has been reported after months or years and is inferred from the rarity of the disease in adults. Conservative surgical excision may be performed for diagnostic or aesthetic purposes or for lesions subject to recurrent trauma. Lesions also can be removed by cryotherapy or carbon dioxide (CO2) laser ablation. Use of topical interferon-b and systemic interferon-a has been reported in a few cases, although with variable results. The risk of recurrence after therapy is minimal, and there seems to be no malignant transformation potential.

SINONASAL PAPILLOMAS

Papillomas of the sinonasal tract are benign, localized proliferations of the respiratory mucosa of this region. This mucosa gives rise to three histomorphologically distinct papillomas:

Lesions exhibiting features of both the inverted and the cylindrical cell types may be termed mixed or hybrid papillomas. In addition, a keratinizing squamous papilloma, similar to the oral squamous papilloma (see page 362), rarely may occur in the nasal vestibule.

Collectively, sinonasal papillomas represent 10% to 25% of all tumors of the nasal and paranasal region. Half of the sinonasal papillomas arise from the mucosa of the lateral nasal wall; the remainder predominantly involve the maxillary and ethmoid sinuses and the nasal septum. Multiple lesions may be present.

The cause of sinonasal papillomas remains controversial and unclear. Some authorities say that these lesions represent neoplasms; others consider them to be a reactive hyperplasia secondary to a variety of environmental stimulants, such as allergy, chronic bacterial or viral (HPV type 11) infection, and tobacco smoking. Recent molecular genetic investigations have shown that inverted papillomas arise from a single progenitor cell (i.e., monoclonal), suggesting that these lesions are neoplastic and recurrence may result from growth of residual transformed cells.

FUNGIFORM (SEPTAL; SQUAMOUS; EXOPHYTIC) PAPILLOMA

The fungiform papilloma bears some similarity to the oral squamous papilloma, although it has a somewhat more aggressive biologic behavior and more varied epithelial types. It represents 18% to 50% of all sinonasal papillomas in various investigations. Almost all examples are positive for HPV type 6 or 11.

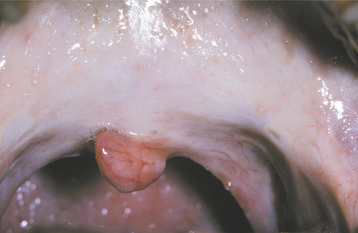

CLINICAL FEATURES: The fungiform papilloma arises almost exclusively on the nasal septum and is twice as common in men as in women. It occurs primarily in people 20 to 50 years of age. Typically, it exhibits unilateral nasal obstruction or epistaxis and appears as a pink or tan, broad-based nodule with papillary or warty surface projections (Fig. 10-16).

HISTOPATHOLOGIC FEATURES: The fungiform papilloma has a microscopic appearance similar to that of the oral squamous papilloma, although the stratified squamous epithelium covering the fingerlike projections seldom is keratinized. Respiratory epithelium or “transitional” epithelium (intermediate between squamous and respiratory) may be seen in some lesions. Mucous (goblet) cells and intraepithelial microcysts containing mucus often are present. Mitoses are infrequent, and dysplasia is rare. The underlying connective tissue consists of delicate fibrous tissue with a minimal inflammatory component, unless it is irritated.

TREATMENT AND PROGNOSIS: Complete surgical excision is the treatment of choice for the fungiform papilloma. Recurrence is common, developing in approximately one third of all cases; however, this may be caused by incomplete excision. Most authorities consider this lesion to have minimal or no potential for malignant transformation.

INVERTED PAPILLOMA (INVERTED SCHNEIDERIAN PAPILLOMA)

The most common (50% to 78%) sinonasal papilloma, the inverted papilloma, is also the variant with the greatest potential for local destruction and malignant transformation. HPV types 6, 11, 16, and 18 have been identified, with considerable variability in the reported proportion of cases positive for HPV. This variability is likely due to differences in detection methods used; however, more recent studies using quantitative real-time polymerase chain reaction (PCR) suggest that HPV is present in approximately 18 to 30% of lesions.

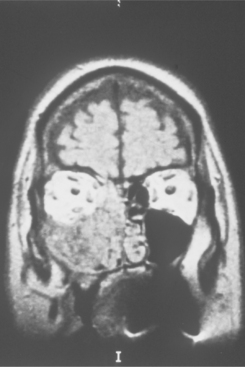

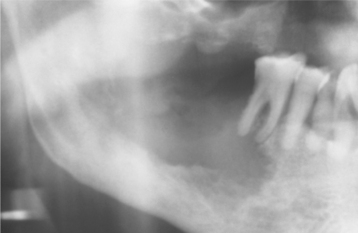

CLINICAL AND RADIOGRAPHIC FEATURES: The inverted papilloma seldom occurs in patients younger than 20 years of age; the median age is 55 years. A strong male predilection is noted (3:1 male-to-female ratio). This lesion arises predominantly from the lateral nasal cavity wall or a paranasal sinus, usually the antrum. Typically, the inverted papilloma results in unilateral nasal obstruction; additional symptoms may include pain, epistaxis, purulent discharge, or local deformity. The papilloma appears as a soft, pink or tan, polypoid or nodular growth. Multiple lesions may be present.

Pressure erosion of the underlying bone is usually present and may be visible radiographically as an irregular radiolucency. Primary sinus lesions may be distinguishable only as a soft tissue radiodensity or mucosal thickening on radiographs; sinus involvement generally represents extension from the nasal cavity. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) can help to identify the extent of the lesion (Fig. 10-17).

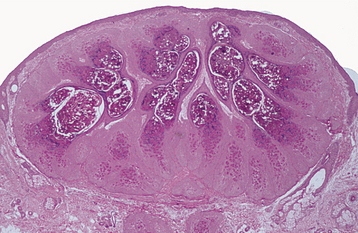

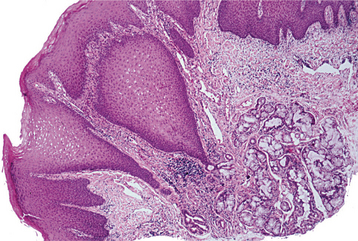

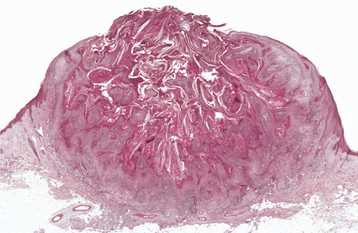

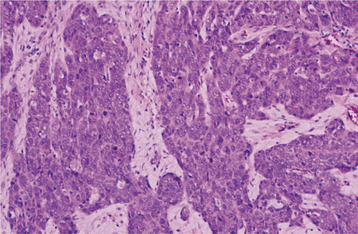

HISTOPATHOLOGIC FEATURES: Microscopically, the inverted papilloma is characterized by squamous epithelial proliferation into the submucosal stroma (Fig. 10-18). The basement membrane remains intact, and the epithelium appears to be “pushing” into underlying connective tissue. Goblet (mucous) cells and mucin-filled microcysts frequently are noted within the epithelium. Keratin production is uncommon, but thin surface keratinization may be seen. Mitoses often are noted within the basilar or parabasilar cells, and varying degrees of dysplasia may be seen. Papillary surface projections are present, and deep clefts may be seen between projections. The stroma consists of dense fibrous or loose myxomatous connective tissue with or without inflammatory cells.

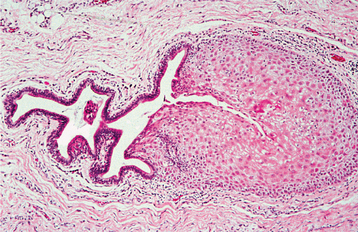

Fig. 10-18 Inverted papilloma. Low-power photomicrograph showing a squamous epithelial proliferation, with multiple “inverting” islands of epithelium extending into the underlying connective tissue.

Destruction of underlying bone frequently is noted. Immunohistochemical expression of CD44, a cell adhesion molecule, is increased in this papilloma, which may help to distinguish it from invasive papillary squamous cell carcinoma, which lacks this feature. Although some authors have suggested that hyperkeratosis, prominent epithelial hyperplasia, and high mitotic index are negative prognostic indicators, no histopathologic parameters have been found to be reliably predictive of recurrence or malignant transformation among inverted papillomas.

TREATMENT AND PROGNOSIS: The inverted papilloma has a significant growth potential and, if neglected, may extend into the nasopharynx, middle ear, orbit, or cranial base. In some studies, recurrence after conservative surgical excision has occurred in nearly 75% of all cases. However, with more aggressive surgical therapy, consisting of medial maxillectomy via a lateral rhinotomy or midfacial degloving approach, recurrence rates of less than 14% have been reported. Although an open surgical approach historically has been regarded as the standard of care, advances in transnasal endoscopic surgery have led to wider acceptance of this method as an alternative, particularly for patients with limited and easily accessible disease. Several investigators, using modern endoscopic techniques and careful patient selection, have reported recurrence rates comparable to those for conventional lateral rhinotomy with medial maxillectomy. Recurrences are usually noted within 2 years of surgery but can happen much later. Hence, long-term follow-up is essential. Continued tobacco smoking is associated with an increased risk of multiple recurrences.

The inverted papilloma also is associated with malignancy, usually squamous cell carcinoma, in 3% to 24% of cases. In such an eventuality, of course, the lesion is treated as a malignancy, typically by performing more radical surgery, with or without adjunctive radiotherapy.

CYLINDRICAL CELL PAPILLOMA (ONCOCYTIC SCHNEIDERIAN PAPILLOMA)

The cylindrical cell papilloma accounts for less than 7% of sinonasal papillomas. This lesion is considered by some authorities to be a variant of the inverted papilloma because of the similarity in clinical and histopathologic features and a similarly low frequency of HPV.

CLINICAL FEATURES: Cylindrical cell papilloma typically occurs in adults 20 to 50 years of age. There is a strong male predominance, with a predilection for the maxillary antrum, lateral nasal cavity wall, and ethmoid sinus. The presenting symptom is usually unilateral nasal obstruction, and it appears as a beefy-red or brown mass with a multinodular surface.

HISTOPATHOLOGIC FEATURES: Microscopically, the cylindrical cell papilloma demonstrates both endophytic and exophytic growth. Surface papillary projections have a fibrovascular connective tissue core and are covered by a multilayered epithelium of tall columnar cells with small, dark nuclei and eosinophilic, occasionally granular, cytoplasm. The lesional epithelial cell is similar to an oncocyte. Cilia may be seen on the surface, and there are numerous intraepithelial microcysts filled with mucin, neutrophils, or both.

MOLLUSCUM CONTAGIOSUM

Molluscum contagiosum is a virus-induced epithelial hyperplasia produced by the molluscum contagiosum virus, a member of the DNA poxvirus group. At least 6% of the population (more in older age groups) has antibodies to this virus, although few ever develop lesions. After an incubation period of 14 to 50 days, infection produces multiple papules of the skin or, rarely, mucous membranes. These remain small for months or years and then spontaneously involute.

During its active phase, the molluscum contagiosum virus is sloughed from a central core in each papule. Routes of transmission include sexual contact (in adults) and such nonsexual contacts (in children and teenagers) as sharing clothing, wrestling, communal bathing, and swimming. Lesions have a predilection for warm portions of the skin and sites of recent injury. Florid cases have been reported in immunocompromised patients, and the prevalence among the human immunodeficiency virus (HIV)-positive patient population is estimated to be 5% to 18% (see page 278). Patients with atopic dermatitis and Darier’s disease also are at risk for developing severe and extensive disease.

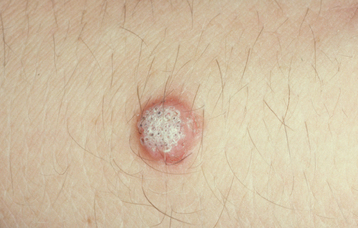

CLINICAL FEATURES: Molluscum contagiosum is usually seen in children and young adults. The papules almost always are multiple and occur predominantly on the skin of the neck, face (particularly eyelids), trunk, and genitalia. Infrequently, oral involvement occurs, usually on the lips, buccal mucosa, palate, or gingiva.

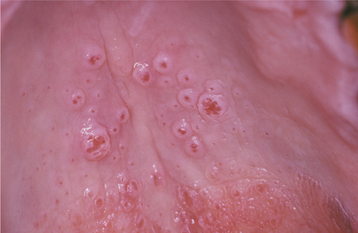

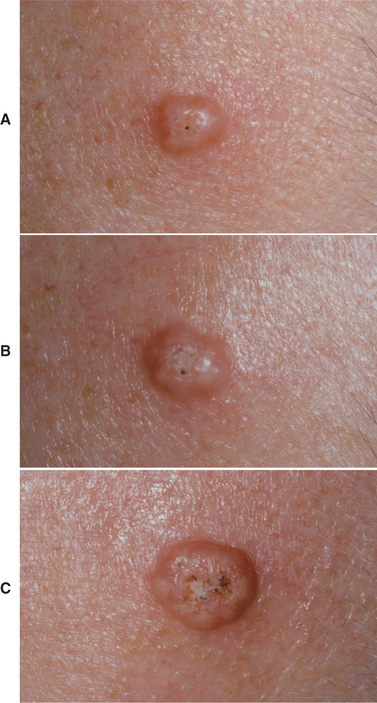

Lesions are pink, smooth-surfaced, sessile, nontender, and nonhemorrhagic papules that are 2 to 4 mm in diameter (Fig. 10-19). Many show a small central indentation or keratin-like plug from which a curdlike substance can be expressed. Some are surrounded by a mild inflammatory erythema and may be slightly tender or pruritic. Eczematous eruptions occasionally may develop in the vicinity of molluscum contagiosum lesions, particularly in patients with atopic dermatitis.

Fig. 10-19 Molluscum contagiosum. Multiple, smooth-surfaced papules, with several demonstrating small keratin-like plugs, are seen on the neck of a child.

In immunocompromised patients, atypical lesions that are unusually large, verrucous, or markedly hyperkeratotic have been described.

HISTOPATHOLOGIC FEATURES: Molluscum contagiosum appears as a localized lobular proliferation of surface stratified squamous epithelium (Fig. 10-20). The central portion of each lobule is filled with bloated keratinocytes that contain large, intranuclear, basophilic viral inclusions called molluscum bodies (or Henderson-Paterson bodies) (Fig. 10-21). These bodies begin as small eosinophilic structures in cells just above the basal layer. As they approach the surface, these bodies increase so much in size that they frequently become larger than the original size of the invaded cells. A central crater is formed at the surface as stratum corneum cells disintegrate to release their molluscum bodies. These unique features make the diagnosis readily apparent.

TREATMENT AND PROGNOSIS: In most cases of molluscum contagiosum, spontaneous remission occurs within 6 to 9 months. For immunocompetent patients, there is ongoing debate as to whether the disease should be treated or allowed to resolve on its own. Treatment may be performed to decrease the risk of disease transmission, prevent autoinoculation, or provide symptomatic relief.

Few controlled studies of treatment efficacy have been performed, but lesions most commonly are removed by curettage or cryotherapy. Alternative treatment methods include CO2 or pulsed dye laser therapy, electrodessication, trichloroacetic acid, silver nitrate, potassium hydroxide, or the topical blistering agent cantharidin. Topical agents such as tretinoin, podophyllotoxin, and imiquimod are additional alternatives, although generally not as effective or rapid as in-office cryotherapy or curettage

In immunosuppressed patients with recalcitrant lesions, the antiviral agent cidofivir may be effective. Moreover, in patients with AIDS, highly active antiretroviral therapy indirectly counteracts molluscum contagiosum infection by increasing CD4+ T cell counts and improving the immune response.

There is no apparent potential to transform into carcinoma, and the lesions tend not to recur after treatment.

VERRUCIFORM XANTHOMA

Verruciform xanthoma is a hyperplastic condition of the epithelium of the mouth, skin, and genitalia, with a characteristic accumulation of lipid-laden histiocytes beneath the epithelium. First reported in 1971, it remains largely an oral disease; its cause is still unknown. Although verruciform xanthoma is a papillary lesion, human papillomavirus (HPV) has been identified in only a small number of cases, and no definitive role for this virus in the pathogenesis of these lesions has been established. The lesion probably represents an unusual reaction or immune response to localized epithelial trauma or damage. This hypothesis is supported by cases of verruciform xanthoma that have developed in association with disturbed epithelium (e.g., lichen planus, lupus erythematosus, epidermolysis bullosa, epithelial dysplasia, squamous cell carcinoma, pemphigus vulgaris, warty dyskeratoma, graft-versus-host disease [GVHD]). The lesion is histopathologically similar to other dermal xanthomas, but it is not associated with diabetes, hyperlipidemia, or any other metabolic disorder.

CLINICAL FEATURES: Verruciform xanthoma is typically seen in whites, 40 to 70 years of age, with a slight male predilection. Approximately half of the intraoral lesions occur on the gingiva and alveolar mucosa, but any oral site may be involved.

The lesion appears as a well-demarcated, soft, painless, sessile, slightly elevated mass with a white, yellow-white, or red color and a papillary or roughened (verruciform) surface (Figs. 10-22 and 10-23). Rarely, flat-topped nodules are seen without surface projections. Most lesions are smaller than 2 cm in greatest diameter; no oral lesion larger than 4 cm has been reported. Multiple lesions occasionally have been described. Clinically, verruciform xanthoma may be similar to squamous papilloma, condyloma acuminatum, or early carcinoma.

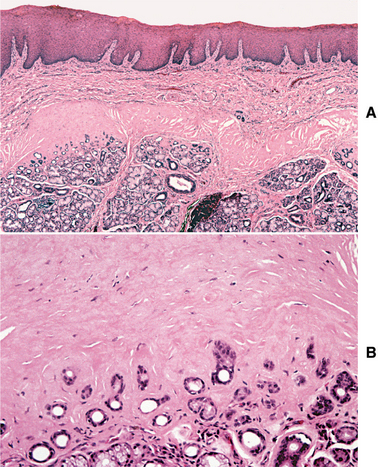

HISTOPATHOLOGIC FEATURES: Verruciform xanthoma demonstrates papillary, acanthotic surface epithelium covered by a thickened layer of parakeratin. On routine hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) staining, the keratin layer often exhibits a distinctive orange coloration (Fig. 10-24). Clefts or crypts between the epithelial projections are filled with parakeratin, and rete ridges are elongated to a uniform depth. The most important diagnostic feature is the accumulation of numerous large macrophages with foamy cytoplasm, which typically are confined to the connective tissue papillae. These foam cells, also known as xanthoma cells, contain lipid and periodic acid-Schiff (PAS)-positive, diastase-resistant granules. With immunohistochemical stains, the xanthoma cells are positive for markers consistent with monocyte-macrophage lineage, including CD68 (KP1) and cathepsin B.

Fig. 10-24 Verruciform xanthoma. A, A slight papillary appearance is produced by hyperparakeratosis, and the rete ridges are elongated to a uniform depth. Note the parakeratin plugging between the papillary projections. B, The connective tissue papillae are composed almost exclusively of xanthoma cells—large macrophages with foamy cytoplasm.

TREATMENT AND PROGNOSIS: The verruciform xanthoma is treated with conservative surgical excision. Recurrence after removal of the lesion is rare, and no malignant transformation has been reported. However, two cases have been reported in which a verruciform xanthoma occurred in association with carcinoma in situ or squamous cell carcinoma. This does not necessarily imply that verruciform xanthoma is a potentially malignant lesion; however, it may indicate that hyperkeratotic or dysplastic oral lesions can undergo degenerative changes to form a verruciform xanthoma.

SEBORRHEIC KERATOSIS

Seborrheic keratosis is an extremely common skin lesion of older people and represents an acquired, benign proliferation of epidermal basal cells. The cause is unknown, although there is a positive correlation with chronic sun exposure, sometimes with a hereditary (autosomal dominant) tendency. In addition, recent genetic studies have suggested that somatic mutations in the FGFR3 (fibroblast growth factor receptor 3) gene are important in the development of these lesions. Seborrheic keratosis does not occur in the mouth.

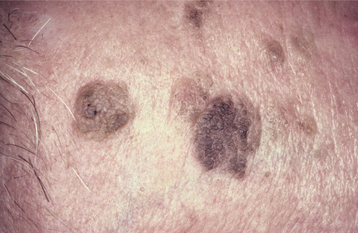

CLINICAL FEATURES: Seborrheic keratoses begin to develop on the skin of the face, trunk, and extremities during the fourth decade of life, and they become more prevalent with each passing decade. Lesions are usually multiple, beginning as small tan to brown macules that are indistinguishable clinically from actinic lentigines (see page 377), and which gradually enlarge and elevate (Figs. 10-25 and 10-26). Individual lesions are sharply demarcated plaques and have surfaces that are finely fissured, pitted, or verrucous, but may be smooth. They tend to appear “stuck onto” the skin and are usually less than 2 cm in diameter.

Fig. 10-25 Seborrheic keratosis. Multiple brown plaques on the face of an older man exhibit a fissured surface. They had been slowly enlarging for several years.

Dermatosis papulosa nigra is a form of seborrheic keratosis that occurs in approximately 30% of blacks and frequently has an autosomal dominant inheritance pattern. This condition typically appears as multiple, small (1 to 2 mm), dark-brown to black papules scattered about the zygomatic and periorbital region (Fig. 10-27).

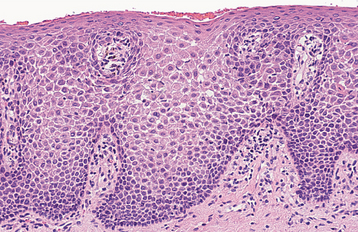

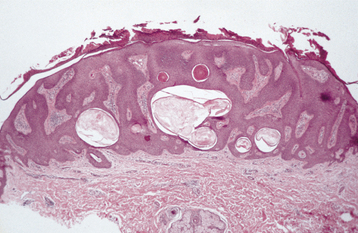

HISTOPATHOLOGIC FEATURES: Seborrheic keratosis consists of an exophytic proliferation of basilar epithelial cells that exhibit varying degrees of surface keratinization, acanthosis, and papillomatosis (Fig. 10-28). Characteristically, the entire epithelial hyperplasia extends upward, above the normal epidermal surface. The lesion usually exhibits deep, keratin-filled invaginations that appear cystic on cross-section; hence, they are called horn cysts or pseudo-horn cysts (Fig. 10-29). Melanin pigmentation often is seen within the basal layer.

Fig. 10-28 Seborrheic keratosis. The acanthotic form demonstrates considerable acanthosis, surface hyperkeratosis, and numerous pseudocysts. The epidermal proliferation extends upward, above the normal epidermal surface.

Fig. 10-29 Seborrheic keratosis. Pseudocysts are actually keratin-filled invaginations, as seen toward the left in this high-power photomicrograph. The surrounding epithelial cells are basaloid in appearance.

Several histopathologic patterns may be seen in seborrheic keratoses. The most common is the acanthotic form, which exhibits little papillomatosis and marked acanthosis with minimal surface keratinization. The hyperkeratotic form is characterized by prominent papillomatosis and hyperkeratosis with minimal acanthosis. The adenoid form consists of anastomosing trabeculae of lesional cells with little hyperkeratosis or papillomatosis. The lesions of dermatosis papulosa nigra are predominantly of the adenoid and acanthotic types.

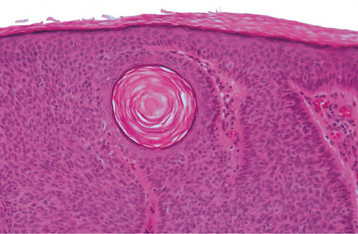

Chronic trauma may alter these histopathologic features, and the lesion known as inverted follicular keratosis of Helwig is thought to represent an irritated seborrheic keratosis. This lesion shows a mild degree of proliferation into the connective tissue and a chronic inflammatory cell infiltrate adjacent to the lesion. Squamous metaplasia of the lesional cells results in whorled epithelial patterns called squamous eddies. Inflamed seborrheic keratosis may show enough nuclear atypia and mitotic activity to cause confusion with squamous cell carcinoma, but enough of the basic attributes of seborrheic keratosis typically remain to allow a proper diagnosis.

TREATMENT AND PROGNOSIS: Except for aesthetic purposes, a seborrheic keratosis seldom is removed. Cryotherapy with liquid nitrogen or simple curettage is the treatment of choice for lesions that are removed. Although the keratosis has no malignant potential, other more significant skin lesions may develop in areas contiguous to it. In rare cases, melanomas may resemble seborrheic keratoses clinically; thus it is important for a dermatologist or other qualified clinician to determine whether it is most appropriate to treat a lesion by cryotherapy or to excise and submit it for histopathologic confirmation. Moreover, the sudden appearance of numerous seborrheic keratoses with pruritus has been associated with internal malignancy, a rare event called the Leser-Trélat sign.

SEBACEOUS HYPERPLASIA

Sebaceous hyperplasia is characterized by a localized proliferation of sebaceous glands of the skin. It has no known cause and is common on the facial skin. In some cases an association with cyclosporine, systemic corticosteroids, hemodialysis, and Muir-Torre syndrome (a rare autosomal dominant disorder characterized by visceral malignancies, sebaceous adenomas and carcinomas, and keratoacanthomas) has been described. The major significance of this entity is its clinical similarity to more serious facial tumors, such as basal cell carcinoma.

CLINICAL FEATURES: Cutaneous sebaceous hyperplasia usually affects adults older than 40 years of age. It occurs most commonly on the skin of the face, especially the nose, cheeks, and forehead. Less commonly, lesions may involve the genital area, chest, and areola. The condition is characterized by one or more soft, nontender papules with white, yellow, or normal coloration (Fig. 10-30). Lesions are usually umbilicated, with a small central depression, representing the area where the ducts of the involved sebaceous lobules terminate. Most lesions are smaller than 5 mm in greatest diameter and take considerable time to reach even this small size.

Fig. 10-30 Sebaceous hyperplasia. Multiple soft papules of the midface are umbilicated and small. Sebum can often be expressed from the central depressed area.

Compression of the lesion usually causes sebum, the thick yellow-white product of the sebaceous gland, to be expressed in the central depressed area. This feature helps clinically to distinguish sebaceous hyperplasia from basal cell carcinoma. An oral counterpart, which probably has no relation to the skin lesion, appears as a white to yellow papule or nodular mass with a “cauliflower” appearance, usually of the buccal mucosa.

HISTOPATHOLOGIC FEATURES: Histopathologically, sebaceous hyperplasia is characterized by a collection of enlarged but otherwise nor-mal sebaceous gland lobules grouped around one or more centrally located sebaceous ducts (Fig. 10-31).

TREATMENT AND PROGNOSIS: No treatment is necessary for sebaceous hyperplasia except for aesthetic reasons or unless basal cell carcinoma cannot be eliminated from the clinical differential diagnosis of cutaneous lesions. Excisional biopsy is curative. Cryosurgery, electrodessication, laser therapy, and photodynamic therapy are alternative methods for removal.

EPHELIS (FRECKLE)

An ephelis is a common small hyperpigmented ma-cule of the skin that represents a region of increased melanin production. Ephelides are seen most often on the face, arms, and back of fair-skinned, blue-eyed, red- or light-blond haired persons; they may be associated with a strong genetic predilection (autosomal dominant). Recent studies have demonstrated a strong relationship between certain variants of the MC1R (melanocortin-1-receptor) gene and the development of ephelides. The skin discoloration is produced by a relative excess of melanin deposition in the epidermis, not by a local increase in the number of melanocytes.

CLINICAL FEATURES: Ephelides become noticeable during the first decade of life, and new macules seldom arise after the teenage years. During adult life the macules typically become less prominent. There is no sex predilection; however, persons with blond or red hair are more likely to have ephelides. The lesions become more pronounced after sun exposure and are associated closely with a history of painful sunburns in childhood.

Each individual macule is round or oval, and typically remains less than 3 mm in diameter (Fig. 10-32). It has a uniform light-brown coloration and is sharply demarcated from the surrounding skin. There is great variability in the numbers of ephelides present. Many individuals have less than 10, whereas some have hundreds of macules. The brown color is not as dark as the lentigo simplex (see page 378), and there is never ele vation above the surface of the skin, as may occur in a melanocytic nevus (see page 382).

HISTOPATHOLOGIC FEATURES: The ephelis is composed of stratified squamous epithelium with abundant melanin deposition in the basal cell layer. Despite the increased melanin, the number of melanocytes is normal or may be somewhat reduced. In contrast to lentigo simplex, there is no elongation of rete ridges.

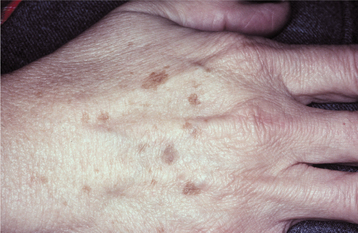

ACTINIC LENTIGO (LENTIGO SOLARIS; SOLAR LENTIGO; AGE SPOT; LIVER SPOT; SENILE LENTIGO)

Actinic lentigo is a benign brown macule that results from chronic ultraviolet (UV) light damage to the skin. It is found in more than 90% of whites older than 70 years of age and rarely is seen before age 40. It does not occur within the mouth but is seen frequently on the facial skin. Persons who have facial ephelides (freckles) in childhood are more likely to develop actinic lentigines later in life. In a recent study of actinic lentigines in older whites, patients with multiple facial lesions typically were dark-skinned individuals who repeatedly received intermittent, intense sun exposure during their lifetime and whose facial lesions were preceded by the development of multiple actinic lentigines on the upper back.

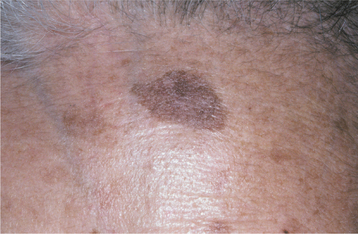

CLINICAL FEATURES: Actinic lentigo is common on the dorsa of the hands, on the face, and on the arms of older whites (Figs. 10-33 and 10-34). It is typically multiple, but individual lesions appear as uniformly pigmented brown to tan macules with well-demarcated but irregular borders. Although the lesion may reach more than 1 cm in diameter, most examples are smaller than 5 mm. Adjacent lesions may coalesce, and new ones continuously arise with age. Unlike ephelides, no change in color intensity is seen after exposure to UV light.

HISTOPATHOLOGIC FEATURES: Rete ridges are elongated and club shaped in actinic lentigines, with thinning of the epithelium above the connective tissue papillae (Fig. 10-35). The ridges sometimes seem to coalesce with one another. Within each rete ridge, melanin-laden basilar cells are intermingled with excessive numbers of heavily pigmented melanocytes.

TREATMENT AND PROGNOSIS: No treatment is required for actinic lentigo, except for aesthetic reasons. Lesions may be treated by cryotherapy, although hypopigmentation is a potential side effect. Laser therapy or intense pulsed light also can be effective. In addition, there is a wide range of topical therapies currently available, including hydroquinone, tretinoin, tazarotene, adapalene, and, more recently, a stable fixed combination of mequinol and tretinoin. Generally, sunscreens are recommended as preventive treatment and for maintenance of treatment success. Actinic lentigo does not undergo malignant transfor mation; if removed, then it rarely recurs. New lesions, however, can arise in adjacent or distant skin at any time.

LENTIGO SIMPLEX

Lentigo simplex is one of several forms of benign cutaneous melanocytic hyperplasia of unknown cause. It usually occurs on skin that is not exposed to sunlight, but it may occur on any skin surface and at any age. Its color intensity does not change with variations in sun exposure. Lentigo simplex is darker in color than the common ephelis (see page 376). Ephelides, moreover, are found predominantly on sun-exposed skin, become more pronounced with increased sun exposure, and represent merely an increase in local melanin production rather than an increase in the number of productive melanocytes.

Some investigators believe that lentigo simplex represents the earliest stage of another common skin lesion, the melanocytic nevus (see page 382). Oral lesions have been reported, but they are rare and may be examples of the oral melanotic macule (see page 379).

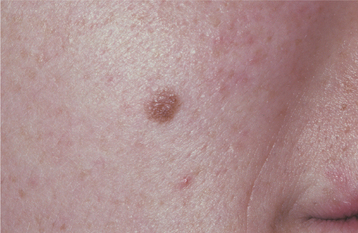

CLINICAL FEATURES: Lentigo simplex usually occurs in children but may occur at any age. The typical lesion is a sharply demarcated macule smaller than 5 mm in diameter, with a uniformly tan to dark-brown color (Fig. 10-36). It is usually solitary, although some patients may have several lesions scattered on the skin of the trunk and extremities. Lentigo simplex reaches its maximum size in a matter of months and may remain unchanged indefinitely thereafter.

Fig. 10-36 Lentigo simplex. A sharply demarcated lesion of uniform brown coloration is seen on the midface.

Clinically, individual lesions of lentigo simplex are indistinguishable from the nonelevated melanocytic nevus. With multiple lesions, conditions such as lentiginosis profusa, Peutz-Jeghers syndrome (see page 753), and the multiple lentigines or LEOPARD* syndrome must be considered as diagnostic possibilities.

HISTOPATHOLOGIC FEATURES: Lentigo simplex shows an increased number of benign melanocytes within the basal layer of the epidermis, and these often are clustered at the tips of the rete ridges. Abundant melanin is distributed among the melanocytes and basal keratinocytes, as well as within the papillary dermis in association with melanophages (melanin incontinence).

TREATMENT AND PROGNOSIS: Lentigo simplex may fade spontaneously after many years, but most lesions remain constant over time. Treatment is not required, except for aesthetic reasons. Conservative surgical excision is curative, and no malignant transformation potential has been documented for lesions not removed.

MELASMA (MASK OF PREGNANCY)

Melasma is an acquired, symmetrical hyperpigmentation of the sun-exposed skin of the face and neck. The cause is unknown, but it is classically associated with pregnancy. Exposure to exogenous estrogen and progesterone in the form of either oral contraceptives or hormone replacement therapy also may cause melasma. Dark-complexioned persons—particularly Asian and Hispanic women—are more likely to develop this condition.

CLINICAL FEATURES: Melasma appears in adult women as bilateral light- to dark-brown cutaneous macules that vary in size from a few millimeters to more than 2 cm in diameter (Fig. 10-37). Lesions develop slowly with sun exposure and occur primarily on the midface, forehead, upper lip, chin, and (rarely) the arms. It is not unusual for the entire face to be involved. The pigmentation may remain faint or darken over time. Rarely, melasma is seen in men.

HISTOPATHOLOGIC FEATURES: Melasma is characterized by increased melanin deposition within an otherwise unremarkable epidermis. Pigment also may be seen within numerous melanophages in the dermis.

TREATMENT AND PROGNOSIS: Melasma is difficult to treat. First-line therapy typically consists of triple-combination topical therapy, such as Tri-Luma cream (a combination of 4% hydroquinone, 0.05% tretinoin, and 0.01% fluocinolone acetonide). Dual-ingredient topical agents (e.g., hydroquinone combined with glycolic acid or kojic acid) or single topical agents (e.g., 4% hydroquinone, 0.1% retinoic acid, or 20% azelaic acid) are alternatives for patients who are sensitive to triple-combination therapy. Options for second-line therapy include glycolic acid chemical peel, laser therapy, and dermabrasion, although variable results have been reported with these alternative therapies. Because sun exposure is an important etiologic factor, sun avoidance and the use of sunscreens containing zinc oxide or titanium dio-xide are crucial for effective clinical management. The lesions may resolve after parturition or after discontinuing oral contraceptives. There is no potential for malignant transformation.

ORAL MELANOTIC MACULE (FOCAL MELANOSIS)

The oral melanotic macule is a flat, brown, mucosal discoloration produced by a focal increase in melanin deposition and possibly a concomitant increase in the number of melanocytes. The cause remains unclear. Unlike the cutaneous ephelis (freckle), the melanotic macule is not dependent on sun exposure. Some authorities have questioned the purported lack of an association with actinic irradiation for the melanotic macule located on the vermilion border and prefer to consider it a distinct entity (labial melanotic macule). In one recent study of more than 773 solitary oral melanocytic lesions submitted to an oral pathology laboratory for histopathologic examination, oral and labial melanotic macules were the most common and comprised 86% of cases; oral and labial melanotic macules were encountered much more frequently than oral melanocytic nevi, melanoacanthomas, and melanomas.

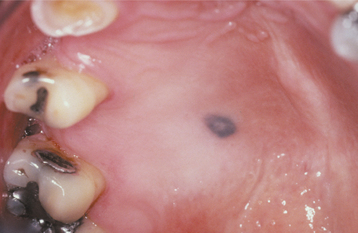

CLINICAL FEATURES: The oral melanotic macule occurs at any age in both men and women; however, biopsy samples demonstrate a 2:1 female predilection. The average age of patients is 43 years at the time of diagnosis. The vermilion zone of the lower lip is the most common site of occurrence (33%), followed by the buccal mucosa, gingiva, and palate. Rare examples have been reported on the tongue in newborns.

The typical lesion appears as a solitary (17% are multiple), well-demarcated, uniformly tan to dark-brown, asymptomatic, round or oval macule with a diameter of 7 mm or smaller (Figs. 10-38 and 10-39). Occasional lesions may be blue or black. Lesions are not reported to enlarge after diagnosis, which suggests that the maximum dimension is achieved rather rapidly and remains constant thereafter.

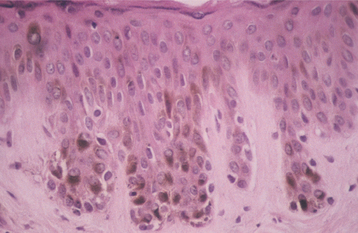

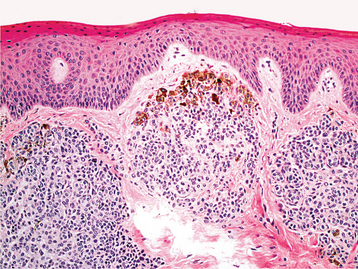

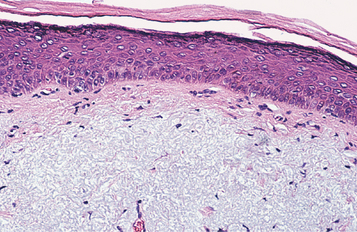

HISTOPATHOLOGIC FEATURES: The oral melanotic macule is characterized by an increase in melanin (and perhaps melanocytes) in the basal and parabasal layers of an otherwise normal stratified squamous epithelium (Fig. 10-40). Melanin also may be seen free or within melanophages in the subepithelial connective tissue (melanin incontinence). The lesion typically does not show elongated rete ridges like actinic lentigo (see page 377).

TREATMENT AND PROGNOSIS: Treatment is usually not required for the melanotic macule, except for aesthetic considerations. When necessary, excisional biopsy is the preferred treatment. Electrocautery, laser ablation, or cryosurgery is effective, but no tissue remains for histopathologic examination after these procedures. The intraoral melanotic macule has no malignant transformation potential, but an early melanoma can have a similar clinical appearance. For this reason, all oral pigmented macules of recent onset, large size, irregular pigmentation, unknown duration, or recent enlargement should be submitted for microscopic examination.

On occasion, flat pigmented lesions are encountered that are clinically and microscopically similar to the melanotic macule; however, these lesions represent a sign of systemic or genetic disease or may be a consequence of the use of certain medications. A list of these conditions is shown in Box 10-1.

ORAL MELANOACANTHOMA (MELANOACANTHOSIS)

Oral melanoacanthoma is a benign, relatively un-common acquired pigmentation of the oral mucosa characterized by dendritic melanocytes dispersed throughout the epithelium. The lesion appears to be a reactive process; in some cases an association with trauma has been reported. Oral melanoacanthoma appears to be unrelated to the melanoacanthoma of skin, which most authorities believe represents a variant of seborrheic keratosis.

CLINICAL FEATURES: Oral melanoacanthoma is seen almost exclusively in blacks, shows a female predilection, and is most common during the third and fourth decades of life. The buccal mucosa is the most common site of occurrence. The lips, palate, gingiva, and alveolar mucosa also may be involved. Most patients exhibit solitary lesions, although bilateral or multifocal involvement is possible as well. Oral melanoacanthomas typically are asymptomatic; however, pain, burning, and pruritus have been reported in a few unusual cases. The lesion is smooth, flat or slightly raised, and dark-brown to black in color (Fig. 10-41). Lesions often demonstrate a rapid increase in size, and they occasionally reach a diameter of several centimeters within a period of a few weeks.

Fig. 10-41 Oral melanoacanthoma. A, Smooth, darkly pigmented macule of the buccal mucosa in a young adult. B, Appearance of the lesion 2 months later showing dramatic enlargement. C, Resolution of the lesion 3 months after incisional biopsy. Rights were not granted to include this figure in electronic media. Please refer to the printed book. (From Park SK, Neville BW: AAOMP case challenge: rapidly enlarging pigmented lesion of the buccal mucosa, J Contemp Dent Pract 3:69-73, 2002.)

HISTOPATHOLOGIC FEATURES: The oral melanoacanthoma is characterized by numerous benign dendritic melanocytes (cells that are normally confined to the basal cell layer) scattered throughout the lesional epithelium (Figs. 10-42 and 10-43). Basal layer melanocytes are also present in increased numbers. Spongiosis and mild acanthosis are typically noted. In addition, eosinophils and a mild to moderate chronic inflammatory cell infiltrate are usually seen within the underlying connective tissue.

TREATMENT AND PROGNOSIS: Because of the alarming growth rate of oral melanoacanthoma, incisional biopsy is usually indicated to rule out the possibility of melanoma. Once the diagnosis has been established, no further treatment is necessary. In several instances, lesions have undergone spontane-ous resolution after incisional biopsy. Recurrence or development of additional lesions has been reported only rarely. There is no potential for malignant transformation.

ACQUIRED MELANOCYTIC NEVUS (NEVOCELLULAR NEVUS; MOLE)

The generic term nevus refers to malformations of the skin (and mucosa) that are congenital or developmental in nature. Nevi may arise from the surface epithelium or any of a variety of underlying connective tissues. The most commonly recognized nevus is the acquired melanocytic nevus, or common mole—so much so that the simple term nevus is often used synonymously for these pigmented lesions. However, many other developmental nevi also are recognized (Box 10-2).

The acquired melanocytic nevus represents a benign, localized proliferation of cells from the neural crest, often called nevus cells. Although there is little debate as to their neural crest origin and their ability to produce melanin, various authorities are divided on the issue of whether these cells represent melanocytes or are merely “first cousins” of melanocytes. These melanocytic cells migrate to the epidermis during development, and lesions may first appear shortly after birth. The acquired melanocytic nevus is probably the most common of all human “tumors,” and white adults have an average of 10 to 40 cutaneous nevi per person. Intraoral lesions occur but are not common.

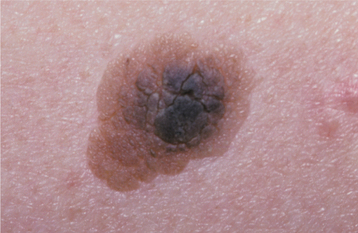

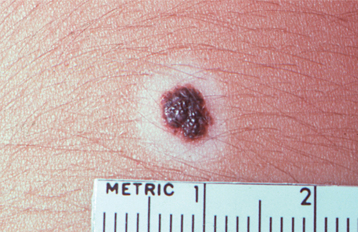

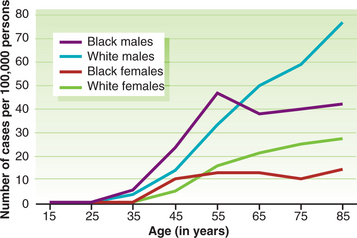

CLINICAL FEATURES: Acquired melanocytic nevi begin to develop on the skin during childhood, and most cutaneous lesions are present before 35 years of age. They occur in both men and women, although women usually have a few more than men. Racial differences are seen. Whites have more nevi than Asians or blacks. Most lesions are distributed above the waist, and the head and neck region is a common site of involvement.

Acquired melanocytic nevi evolve through several clinical stages, which tend to correlate with specific histopathologic features. The earliest presentation (known microscopically as a junctional nevus) is that of a sharply demarcated, brown or black macule, typically less than 6 mm in diameter. Although this lesional appearance may persist into adulthood, more often the nevus cells proliferate over a period of years to produce a slightly elevated, soft papule with a relatively smooth surface (compound nevus). The degree of pigmentation becomes less; most lesions appear brown or tan.

As time passes, the nevus gradually loses its pigmentation, the surface may become somewhat papillomatous, and hairs may be seen growing from the center (intradermal nevus) (Figs. 10-44 and 10-45). However, the nevus usually remains less than 6 mm in diameter. Ulceration is not a feature unless, for example, the nevus is situated in an area where a belt or bra strap traumatizes it easily. Throughout the adult years, many acquired melanocytic nevi will involute and disappear; therefore, fewer of these lesions can be detected in older persons.

Fig. 10-44 Melanocytic (intradermal) nevus. A well-demarcated, dome-shaped papule is seen at the edge of the vermilion border of the upper lip.

Intraoral melanocytic nevi are distinctly uncommon. Most arise on the palate, mucobuccal fold, or gingiva, although any oral mucosal site may be affected (Fig. 10-46). Intraoral melanocytic nevi have an evolution and appearance similar to skin nevi, although mature lesions typically do not demonstrate a papillary surface change. More than one in five intraoral nevi lack clinical pigmentation (Fig. 10-47). Approximately two thirds of intraoral examples are found in females; the average age at diagnosis is 35 years.

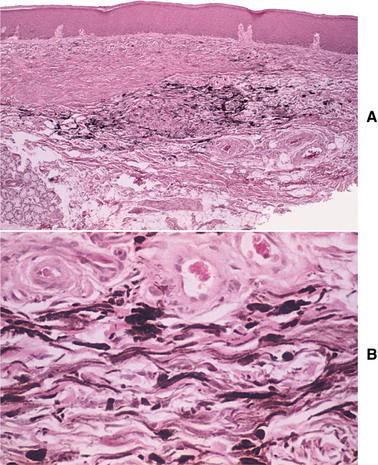

HISTOPATHOLOGIC FEATURES: The acquired melanocytic nevus is characterized by a benign, unencapsulated proliferation of small, ovoid cells (nevus cells). The lesional cells have small, uniform nuclei and a moderate amount of eosinophilic cytoplasm, with indistinct cell boundaries. These cells demonstrate a variable capacity to produce melanin, with the pigment primarily evident in the superficial aspects of the lesion. Nevus cells typically lack the dendritic processes that melanocytes possess. A characteristic microscopic feature is that the superficial nevus cells tend to be organized into small, round aggregates (thèques).

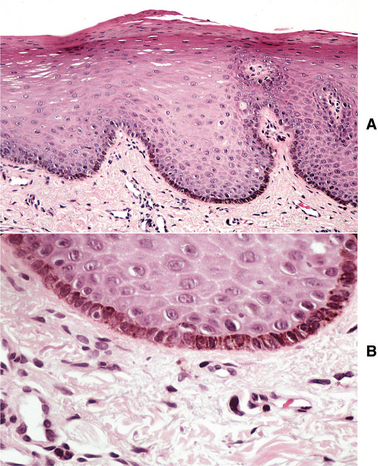

Melanocytic nevi are classified histopathologically according to their stage of development, which is reflected by the relationship of the nevus cells to the surface epithelium and underlying connective tissue. In the early stages, thèques of nevus cells are found only along the basal cell layer of the epithelium, especially at the tips of the rete ridges. Because the lesional cells are found at the junction between the epithelium and the connective tissue, this stage is known as a junctional nevus (Fig. 10-48). As the nevus cells proliferate, groups of cells begin to drop off into the underlying dermis or lamina propria. Because cells are now present along the junctional area and within the underlying connective tissue, the lesion then is called a compound nevus (Fig. 10-49).

Fig. 10-48 Junctional nevus. Nests of melanocytic nevus cells along the basal layer of the epithelium.

Fig. 10-49 Compound nevus. High-power view showing nests of pigmented nevus cells within the epithelium and the superficial lamina propria.

In the later stages, nests of nevus cells are no longer found within the epithelium but are found only within the underlying connective tissue. Because of the connective tissue location of the lesional cells, on the skin this stage is called an intradermal nevus. The intraoral counterpart is called an intramucosal nevus (Fig. 10-50). Zones of differentiation often are seen throughout the lesion. The superficial cells typically appear larger and epithelioid, with abundant cytoplasm, frequent intracellular melanin, and a tendency to cluster into thèques. Nevus cells of the middle portion of the lesion have less cytoplasm, are seldom pigmented, and appear much like lymphocytes. Deeper nevus cells appear elongated and spindle shaped, much like Schwann cells or fibroblasts. Some authorities classify these variations as type A (epithelioid), type B (lymphocyte-like), and type C (spindle shaped) nevus cells.

Most intraoral melanocytic nevi are classified microscopically as intramucosal nevi. However, this probably reflects the age (average, 35 years) at which most oral nevi undergo biopsy and diagnosis, because these lesions would have earlier evolved through junctional and compound stages.

TREATMENT AND PROGNOSIS: No treatment is indicated for a cutaneous melanocytic nevus unless it is cosmetically unacceptable, is chronically irritated by clothing, or shows clinical evidence of a change in size or color. By midlife, cutaneous melanocytic nevi tend to regress; by age 90, very few remain. If removal is elected, then conservative surgical excision is the treatment of choice; recurrence is unlikely.

At least some skin melanomas arise from longstanding or irritated nevi of the skin. Overall, the risk of transformation of a particular acquired melanocytic nevus to melanoma is approximately 1 in 1 million. However, because oral melanocytic nevi clinically can mimic an early melanoma, it is generally advised that biopsy be performed for all unexplained pigmented oral lesions, especially because of the extremely poor prognosis for oral melanoma discovered in its later stages.

VARIANTS OF MELANOCYTIC NEVUS

Congenital melanocytic nevus affects approximately 1% of newborns in the United States. This entity is usually divided into two types: (1) small (<20 cm in diameter) and (2) large (>20 cm in diameter). Approximately 15% of congenital nevi are found in the head and neck area, although intraoral involvement is quite rare.

CLINICAL FEATURES: The small congenital melanocytic nevus may be similar in appearance to an acquired melanocytic nevus, but it is frequently larger in diameter (Figs. 10-51 and 10-52). The large congenital lesion classically appears as a brown to black plaque, usually with a rough surface or multiple nodular areas. However, the clinical appearance often changes with time. Early lesions are flat and light tan, becoming elevated, rougher, and darker with age. A common feature is the presence of hypertrichosis (excess hair) within the lesion, which may become more prominent with age (giant hairy nevus). A very large congenital nevus sometimes may be referred to as bathing trunk nevus or garment nevus, because it gives the appearance of the patient wearing an article of clothing.

HISTOPATHOLOGIC FEATURES: The histopathologic appearance of the congenital melanocytic nevus is similar to that of the acquired melanocytic nevus, and some small congenital nevi cannot be distinguished microscopically from the acquired nevus. Both congenital and acquired types are composed of nevus cells, which may have a junctional, compound, or intradermal pattern. The congenital nevus is usually of the compound or intradermal type. In contrast to the acquired melanocytic nevus, the congenital nevus often shows extension of nevus cells into the deeper levels of the dermis, with “infiltration” of cells between collagen bundles. In addition, congenital nevus cells often are seen intermingled with neurovascular bundles in the reticular dermis and surrounding normal adnexal skin structures (e.g., hair follicles, sebaceous glands). Large congenital melanocytic nevi may show extension of nevus cells into the subcutaneous fat.

TREATMENT AND PROGNOSIS: Many congenital melanocytic nevi are excised for aesthetic purposes. In addition, 3% to 15% of large congenital nevi may undergo malignant transformation into melanoma. Therefore, whenever feasible, these lesions should be removed completely by conservative surgical excision. Close follow-up is required for lesions not removed. Patients with multiple large congenital nevi also are at risk for developing neurocutaneous melanosis, a rare congenital syndrome in which patients may develop melanotic neoplasms of the central nervous system (CNS), including meningeal melanosis or melanoma. Unfortunately, no effective therapy is currently available for patients with symptomatic neurocutaneous melanosis.

HALO NEVUS

Halo nevus is a melanocytic nevus with a pale hypopigmented border or “halo” of the surrounding epithelium, apparently as a result of nevus cell destruction by the immune system. The halo develops because the immune cells also attack the melanocytes adjacent to the nevus. The cause of the immune attack is unknown, but regression of the nevus usually results. Interestingly, the development of multiple halo nevi has been seen in patients who have had a recent excision of a melanoma.

CLINICAL FEATURES: The halo nevus is typically an isolated phenomenon associated with a preexisting acquired melanocytic nevus. It is most common on the skin of the trunk during the second decade of life. The lesion typically appears as a central pigmented papule or macule, surrounded by a uniform, 2- to 3-mm zone of hypopigmentation (Fig. 10-53). Sometimes this peripheral zone is much wider.

SPITZ NEVUS (BENIGN JUVENILE MELANOMA; SPINDLE AND EPITHELIOID CELL NEVUS)

Spitz nevus is an uncommon type of melanocytic nevus that shares many histopathologic features with melanoma. It was, in fact, first described as a juvenile melanoma. The distinctly benign biologic behavior of the lesion was first emphasized by Spitz in 1948. The first oral example was not reported until 1990.

CLINICAL FEATURES: The Spitz nevus typically develops on the skin of the extremities or the face during childhood. It appears as a solitary, dome-shaped, pink to reddish-brown papule, usually smaller than 6 mm in greatest diameter. The young age at presentation and the relatively small size of the Spitz nevus are useful features to help distinguish it from melanoma.

HISTOPATHOLOGIC FEATURES: The Spitz nevus has the overall microscopic architecture of a compound nevus, showing a zonal differentiation from the superficial to deep aspects of the lesion and good symmetry. Lesional cells are either spindle shaped or plump (epithelioid), and the two types often are intermixed. The epithelioid cells may be multinucleated and appear somewhat bizarre, often lacking cell cohesiveness. Mitotic figures, all normal in appearance, may be seen in the superficial aspects of the lesion. Ectatic superficial blood vessels, which probably impart much of the reddish color of some lesions, are seen frequently. The nevocellular nature of the lesional cells is demonstrated by immunohistochemical reactivity for S-100 protein and neuron-specific enolase.

BLUE NEVUS (DERMAL MELANOCYTOMA; JADASSOHN-TIèCHE NEVUS)

Blue nevus is an uncommon, benign proliferation of dermal melanocytes, usually deep within subepithelial connective tissue. Two major types of blue nevus are recognized: (1) the common blue nevus and (2) the cellular blue nevus. The common blue nevus is the second most frequent melanocytic nevus encountered in the mouth. The blue color of this melanin-producing lesion can be explained by the Tyndall effect, which relates to the interaction of light with particles in a colloidal suspension. In the case of a blue nevus, the melanin particles are deep to the surface, so that the light reflected back has to pass through the overlying tissue. Colors with long wavelengths (reds and yellows) tend to be more readily absorbed by the tissues; the shorter-wavelength blue light is more likely to be reflected back to the observer’s eyes.

CLINICAL FEATURES: The common blue nevus may affect any cutaneous or mucosal site, but it has a predilection for the dorsa of the hands and feet, the scalp, and the face. Mucosal lesions may involve the oral mucosa, conjunctiva, and, rarely, sinonasal mucosa. Oral lesions are found almost always on the palate. The lesion usually occurs in children and young adults, and a female predilection is seen. It appears as a macular or dome-shaped, blue or blue-black lesion smaller than 1 cm in diameter (Fig. 10-54).

The cellular blue nevus is much less common and usually develops during the second to fourth decades of life, but it may be congenital. More than 50% of cellular blue nevi arise in the sacrococcygeal or buttock region, although they may be seen on other cutaneous or mucosal surfaces. Clinically, this nevus appears as a slow-growing, blue-black papule or nodule that sometimes attains a size of 2 cm or more. Occasional lesions remain macular.

HISTOPATHOLOGIC FEATURES: Histopathologically, the common blue nevus consists of a collection of elongated, slender melanocytes with branching dendritic extensions and numerous melanin globules. These cells are located deep within the dermis or lamina propria (Fig. 10-55) and usually align themselves parallel to the surface epithelium. The cellular blue nevus appears as a well-circumscribed, highly cellular aggregation of plump, melanin-producing spindle cells within the dermis or submucosa. More typical pigmented dendritic spindle cells are seen at the periphery of the lesional tissue. Occasionally, a blue nevus is found in conjunction with an overlying melanocytic nevus, in which case the term combined nevus is used.

TREATMENT AND PROGNOSIS: If clinically indicated, conservative surgical excision is the treatment of choice for the blue nevus of the skin. Recurrence is minimal with this treatment. Malignant transformation to melanoma is rare but has been reported. However, because an oral blue nevus clinically can mimic an early melanoma, it is usually advisable to perform a biopsy of intraoral pigmented lesions, especially because of the extremely poor prognosis for oral melanoma (see page 433).

LEUKOPLAKIA (LEUKOKERATOSIS; ERYTHROLEUKOPLAKIA)

Oral leukoplakia (leuko = white; plakia = patch) is defined by the World Health Organization (WHO) as “a white patch or plaque that cannot be characterized clinically or pathologically as any other disease.” The term is strictly a clinical one and does not imply a specific histopathologic tissue alteration.

The definition of leukoplakia is unusual in that it makes the diagnosis dependent not so much on definable appearances as on the exclusion of other entities that appear as oral white plaques. Such lesions as lichen planus, morsicatio (chronic cheek nibbling), frictional keratosis, tobacco pouch keratosis, nicotine stomatitis, leukoedema, and white sponge nevus must be ruled out before a clinical diagnosis of leukoplakia can be made. As with most oral white lesions, the clinical color results from a thickened surface keratin layer, which appears white when wet, or a thickened spinous layer, which masks the normal vascularity (redness) of the underlying connective tissue.

Although leukoplakia is not associated with a specific histopathologic diagnosis, it is typically considered to be a precancerous or premalignant lesion. When the outcome of a large number of leukoplakic lesions is reviewed, the frequency of transformation into malignancy is greater than the risk associated with normal or unaltered mucosa. Because there is considerable misunderstanding of this concept, Box 10-3 provides definitions that are used throughout the chapter.

INCIDENCE AND PREVALENCE: Although leukoplakia is considered a premalignant lesion, the use of the clinical term in no way suggests that histopathologic features of epithelial dysplasia are present in all lesions. Dysplastic epithelium or frankly invasive carcinoma is, in fact, found in only 5% to 25% of biopsy samples of leukoplakia. The precancerous nature of leukoplakia has been established, not so much on the basis of this association or on the fact that more than one third of oral carcinomas have leukoplakia in close proximity, as on the results derived from clinical investigations that monitored numerous leukoplakic lesions for long periods. The latter studies suggest a malignant transformation potential of 4% (estimated lifetime risk). Specific clinical subtypes or phases, mentioned later, are associated with potential rates as high as 47%. These figures may be artificially low because many lesions are surgically removed at the beginning of follow-up.

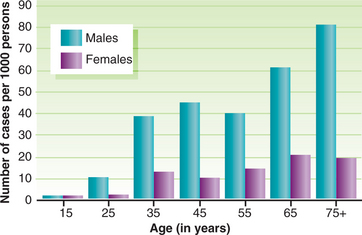

Leukoplakia is by far the most common oral precancer, representing 85% of such lesions. Based on pooled, weighted data from previously reported studies, the worldwide prevalence of leukoplakia has been estimated to fall within a range of 1.5% to 4.3%. There is a strong male predilection (70%), except in regional populations in which women use tobacco products more than men. A slight decrease in the proportion of affected males, however, has been noted over the past half century. The disease is diagnosed more frequently now than in the past, probably because of an enhanced awareness on the part of health professionals (rather than because of a real increase in frequency).

CAUSE: The cause of leukoplakia remains unknown, although hypotheses abound.

TOBACCO: The habit of tobacco smoking appears most closely associated with leukoplakia development. More than 80% of patients with leukoplakia are smokers. When large groups of adults are examined, smokers are much more likely to have leukoplakia than nonsmokers. Heavier smokers have greater numbers of lesions and larger lesions than do light smokers, especially after many years of tobacco use. In addition, a large proportion of leukoplakias in persons who stop smoking either disappear or become smaller within the first year of habit cessation.

The smokeless tobacco habit produces a somewhat different result. It often leads to a clinically distinctive white oral plaque called tobacco pouch keratosis (see page 398). This lesion probably is not a true leukoplakia.

ALCOHOL: Alcohol, which seems to have a strong synergistic effect with tobacco relative to oral cancer production, has not been associated with leukoplakia. People who excessively use mouth rinses with an alcohol content greater than 25% may have grayish buccal mucosal plaques, but these are not considered true leukoplakia.

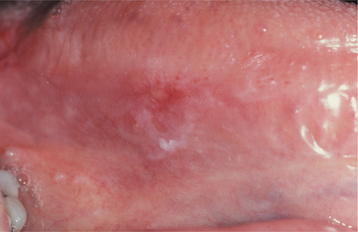

SANGUINARIA: Persons who use toothpaste or mouth rinses containing the herbal extract, sanguinaria, may develop a true leukoplakia. This type of leukoplakia (sanguinaria-associated keratosis) is usually located in the maxillary vestibule or on the alveolar mucosa of the maxilla (Fig. 10-56). More than 80% of individuals with vestibular or maxillary alveolar leukoplakia have a history of using products that contain sanguinaria, compared with 3% of the normal population.

The affected epithelium may demonstrate dysplasia identical to that seen in other leukoplakias, although the potential for the development of cancer is uncertain. The leukoplakic plaque may not disappear even after the patient stops using the product; some lesions have persisted for years afterwards.

ULTRAVIOLET RADIATION: Ultraviolet radiation is accepted as a causative factor for leukoplakia of the lower lip vermilion. This is usually associated with actinic cheilosis (see page 405). Immunocompromised persons, especially transplant patients, are especially prone to the development of leuko-plakia and squamous cell carcinoma of the lower lip vermilion.

MICROORGANISMS: Several microorganisms have been implicated in the cause of leukoplakia. Treponema pallidum, for example, produces glossitis in the late stage of syphilis, with or without the arsenic therapy in popular use before the advent of modern antibiotics. The tongue is stiff and frequently has extensive dorsal leukoplakia.

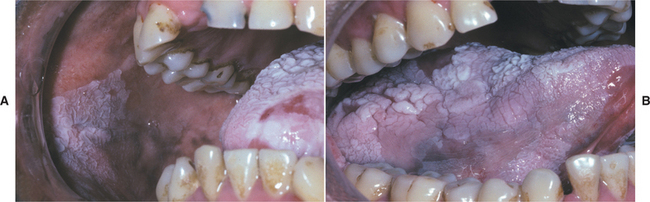

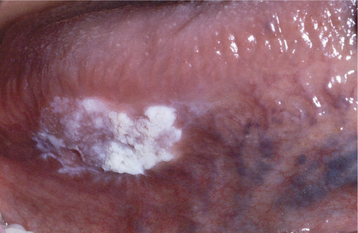

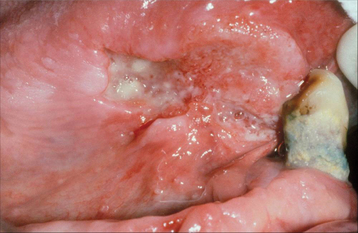

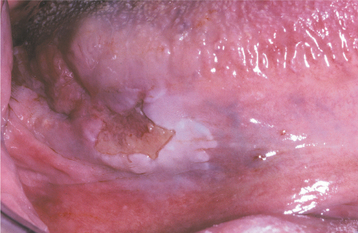

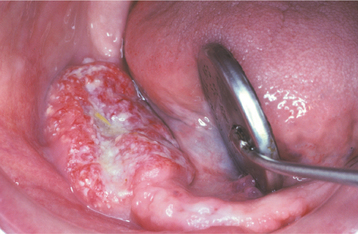

Tertiary syphilis is rare today, but oral infections by another microorganism, Candida albicans, are not. Candida organisms can colonize the superficial epithelial layers of the oral mucosa, often producing a thick, granular plaque with a mixed white and red coloration (Fig. 10-57). The terms candidal leukoplakia and candidal hyperplasia have been used to describe such a lesion, and biopsy may show dysplastic or hyperplastic histopathologic changes. It is not known whether this yeast produces dysplasia or secondarily infects previously altered epithelium, but some of these lesions disappear or become less extensive, even less severely dysplastic, after antifungal therapy. Tobacco smoking may cause the leukoplakia and also predispose the patient to develop candidiasis.

Fig. 10-57 Candidal leukoplakia. A, Well-circumscribed red and white plaque on the anterior floor of mouth, which showed candidal infestation on cytology smears. B, After antifungal therapy, the erythematous component resolved, resulting in a homogeneous white plaque.

Human papillomavirus (HPV), in particular subtypes 16 and 18, has been identified in some oral leukoplakias. These are the same HPV subtypes associated with uterine cervical carcinoma and a subset of oral squamous cell carcinomas. Such viruses, unfortunately, also can be found in normal oral epithelial cells, and so their presence is perhaps no more than coincidental. It may be significant, however, that HPV-16 has been shown to induce dysplasia-like changes in normally differentiating squamous epithelium in an otherwise sterile in vitro environment.