Bone Pathology*

OSTEOGENESIS IMPERFECTA

Osteogenesis imperfecta comprises a heterogeneous group of heritable disorders characterized by impairment of collagen maturation. Except on rare occasions, the disorder arises from heterozygosity for mutations in one of two genes that guide the formation of type I collagen: the COL1A1 gene on chromosome 17 and the COL1A2 gene on chromosome 7. Collagen forms a major portion of bone, dentin, sclerae, ligaments, and skin; osteogenesis imperfecta demonstrates a variety of changes that involve these sites. Several different forms of osteogenesis imperfecta are seen, and they represent the most common type of inherited bone disease. Abnormal collagenous maturation results in bone with a thin cortex, fine trabeculation, and diffuse osteoporosis. Upon fracture, healing will occur but may be associated with exuberant callus formation.

CLINICAL AND RADIOGRAPHIC FEATURES: Osteogenesis imperfecta is a rare disorder that affects 1 in 8000 individuals, with many being stillborn or dying shortly after birth. Both autosomal dominant and recessive hereditary patterns occur, and many cases are sporadic. The severity of the disease varies widely, even in affected members of a single family. In addition to bone fragility, some affected individuals also have blue sclera, altered teeth, hypoacusis (hearing loss), long bone and spine deformities, and joint hyper-extensibility.

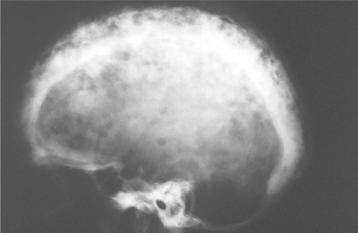

The radiographic hallmarks of osteogenesis imperfecta include osteopenia, bowing, angulation or deformity of the long bones, multiple fractures, and wormian bones in the skull. Wormian bones consist of 10 or more sutural bones that are 6 × 4 mm in diameter or larger and arranged in a mosaic pattern. Wormian bones are not specific and can be seen in other processes, such as cleidocranial dysplasia.

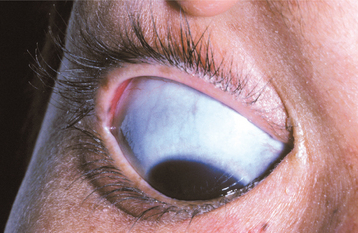

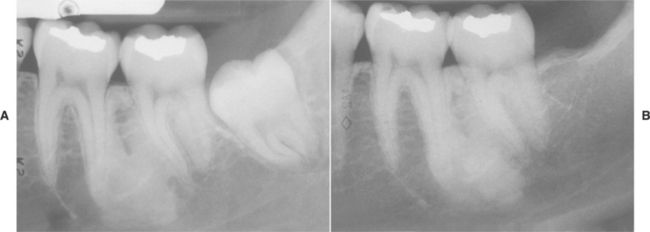

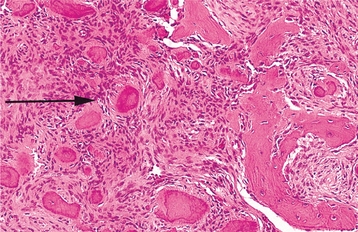

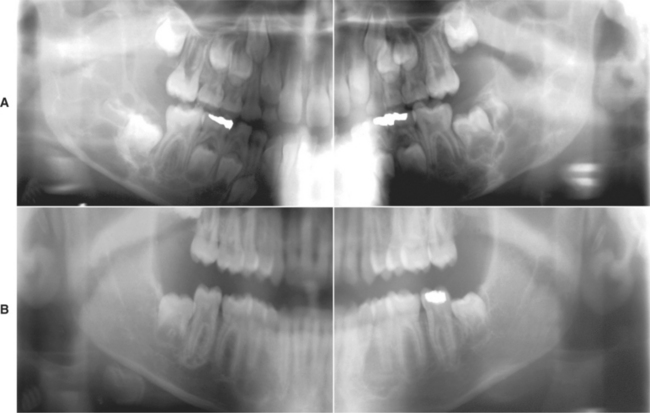

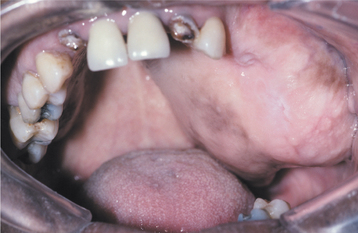

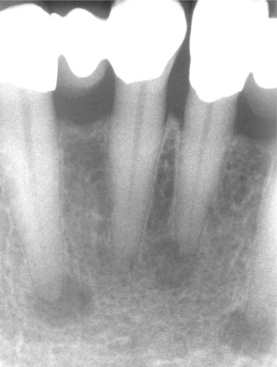

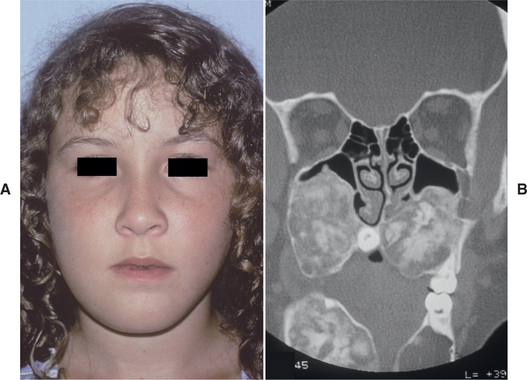

Several distinctive findings are noted in the oral cavity. Dental alterations that appear clinically and radiographically identical to dentinogenesis imperfecta (see page 106) are occasionally noted (Fig. 14-1, A). In affected patients, both dentitions are involved and demonstrate blue to brown translucence. Radiographs typically reveal premature pulpal obliteration, although shell teeth rarely may be seen (Fig. 14-1, B). Although the altered teeth closely resemble dentinogenesis imperfecta, the two diseases are the result of different mutations and should be considered as separate processes. Such dental defects in association with the systemic bone disease should be termed opalescent teeth, reserving the diagnosis of dentinogenesis imperfecta for those patients with alterations isolated to the teeth.

Fig. 14-1 Osteogenesis imperfecta. A, Opalescent dentin in a patient with osteogenesis imperfecta. B, Bite-wing radiograph of the same patient showing shell teeth with thin dentin and enamel of normal thickness. (Courtesy of Dr. Tom Ison.)

In addition, patients with osteogenesis imperfecta demonstrate an increased prevalence of Class III malocclusion that is caused by maxillary hypoplasia, with or without mandibular hyperplasia. On rare occasions, panoramic radiographs may reveal multifocal radiolucencies, mixed radiolucencies, or radiopacities that resemble those seen in florid cemento-osseous dysplasia. When predominantly radiopaque, these areas are sensitive to inflammation and undergo sequestration easily. In these patients, marked coarseness also is noted in the remainder of the skeleton.

Four major types of osteogenesis imperfecta are recognized, each having several subtypes.

TYPE I OSTEOGENESIS IMPERFECTA: Type I is the most common and mildest form. Affected patients have mild to moderately severe bone fragility. Fractures are present at birth in about 10% of cases, but there is great variability in frequency and age of onset of fractures, with 10% of patients not demonstrating fractures. Most fractures occur during the preschool years and are less common after puberty. Hearing loss commonly develops before age 30, and most older patients have hearing deficits. Hypermobile joints and easy bruising because of capillary fragility are not rare. Some affected patients have normal teeth, but others show opalescent dentin. The sclerae are distinctly blue at all ages and aid in classification. Osteogenesis imperfecta type I is inherited as an autosomal dominant trait.

TYPE II OSTEOGENESIS IMPERFECTA: Osteogenesis imperfecta type II is the most severe form and exhibits extreme bone fragility and frequent fractures, which may occur during delivery. Many patients are stillborn, and 90% die before 4 weeks of age. Blue sclerae are present (Fig. 14-2). Opalescent teeth may be present. Both autosomal recessive and dominant patterns may occur, and many cases appear to be sporadic.

TYPE III OSTEOGENESIS IMPERFECTA: Type III is the most severe form noted in individuals beyond the perinatal period and demonstrates moderately severe to severe bone fragility. The sclerae are normal or pale blue or gray at birth; if discoloration is present, then it fades as the child grows older. Ligamentous laxity and hearing loss are common. Fractures may be present at birth, but there is a low mortality in infancy. Although one third survive into adulthood, the majority of affected individuals die during childhood, usually from cardiopulmonary complications caused by kyphoscoliosis. Some patients have opalescent dentin, whereas others have normal teeth. Both autosomal dominant and recessive hereditary patterns are noted.

TYPE IV OSTEOGENESIS IMPERFECTA: Type IV is associated with mild to moderately severe bone fragility. The sclerae may be pale blue in early childhood, but the blue color fades later in life. Fractures are present at birth in about 50% of these patients. The frequency of fractures decreases after puberty, and some individuals never experience bone fracture at any time. Some of these patients have opalescent dentin; others have normal teeth. This variant appears to be inherited as an autosomal dominant trait.

HISTOPATHOLOGIC FEATURES: On histopathologic examination, cortical bone appears attenuated. Osteoblasts are present, but bone matrix production is reduced markedly. The bone architecture remains immature throughout life, and there is a failure of woven bone to become transformed to lamellar bone.

Histopathologically, teeth from affected patients can exhibit abnormalities of dentin similar to those described for patients with dentinogenesis imperfecta (see page 108). These microscopic findings tend to be most pronounced in teeth that clinically appear opalescent. However, mild dentinal abnormalities may be found even in teeth that appear normal clinically and radiographically.

TREATMENT AND PROGNOSIS: There is no cure for osteogenesis imperfecta; thus symptomatic improvement is the primary goal of currently available treatment options. Management of the fractures may be a major problem. The mainstays of treatment are physiotherapy, rehabilitation, and orthopedic surgery. Medical treatment with intravenous (IV) or oral bisphosphonates can provide clinical benefits, including decreased pain, reduced risk of fracture, and improved mobility. However, the long-term consequences of bisphosphonate therapy—particularly when administered to a pediatric patient population—are currently unknown; therefore, bisphosphonates are generally reserved for moderately to severely affected patients. Patients with opalescent dentin usually show severe attrition of their teeth, leading to tooth loss. Treatment of the dentition is similar to that used for dentinogenesis imperfecta (see page 108), but use of implants is questionable because of the deficient quality of the supporting bone.

In patients with significant malocclusion, orthog-nathic surgery may be performed. Alternatively, osteodistraction may be a consideration to reduce the risk of atypical fractures from conventional orthognathic procedures (e.g., Le Fort I osteotomy). The potential for associated medical problems makes presurgical planning paramount. Although the risks are highly variable, occasional patients have associated bleeding disorders, cardiac malformations, and an increased potential for hyperthermia. Intubation may be difficult because of kyphoscoliosis and ease of fracture of the mandible and cervical vertebrae.

The prognosis varies from relatively good to very poor. Some patients have little to no disability, whereas others have severe crippling as a result of the fractures. In severe forms, death occurs in utero, during delivery, or early in childhood.

OSTEOPETROSIS (ALBERS-SCHÖNBERG DISEASE; MARBLE BONE DISEASE)

Osteopetrosis is a group of rare hereditary skeletal disorders characterized by a marked increase in bone density resulting from a defect in remodeling caused by failure of normal osteoclast function. The number of osteoclasts present is often increased; however, because of their failure to function normally, bone is not resorbed. Defective osteoclastic bone resorp-tion, combined with continued bone formation and endochondral ossification, results in thickening of cortical bone and sclerosis of the cancellous bone.

Although genetic defects have yet to be identified in a substantial percentage of patients with osteopetrosis, mutations discovered thus far have been found to cause defects in key elements necessary for osteoclast function, including the H+-ATPase proton pump, chloride channel, and carbonic anhydrase II. These proteins are necessary for acidification of resorption lacunae, regulation of ionic charge across the osteoclast cell membrane, and subsequent resorption of the bone matrix.

Although a number of types have been identified, these pathoses group into two major clinical patterns: (1) infantile and (2) adult osteopetrosis. The infantile form has an estimated incidence of 1:200,000 to 1:300,000, and the adult form has an estimated incidence of 1 in 100,000 to 1:500,000. The clinical severity of the disease varies widely, even within the same pattern of osteopetrosis.

CLINICAL AND RADIOGRAPHIC FEATURES:

INFANTILE OSTEOPETROSIS: Patients discovered with osteopetrosis at birth or in early infancy usually have severe disease that is termed malignant osteopetrosis. In most cases, infantile osteopetrosis is inherited as an autosomal recessive trait and leads to a diffusely sclerotic skeleton. Marrow failure, frequent fractures, and evidence of cranial nerve compression are common.

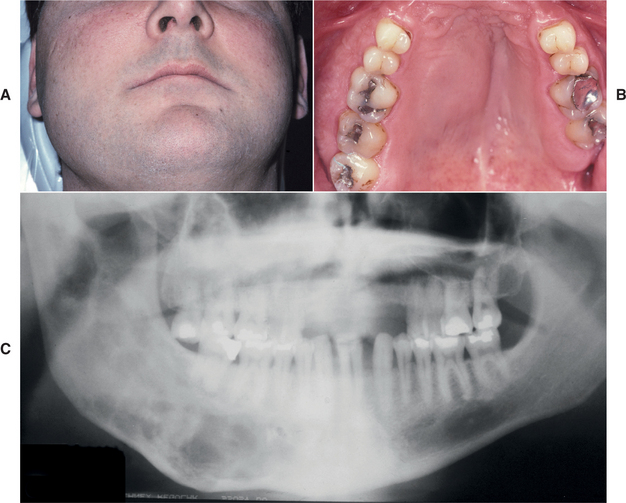

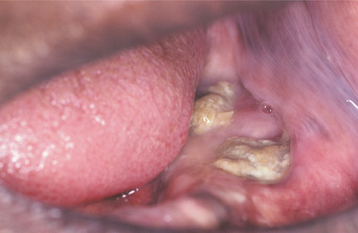

The initial signs of infantile osteopetrosis often are normocytic anemia with hepatosplenomegaly resulting from compensatory extramedullary hematopoiesis. Increased susceptibility to infection is common as a result of granulocytopenia. Facial deformity develops in many of the children, manifesting as a broad face, hypertelorism, snub nose, and frontal bossing. Tooth eruption almost always is delayed. Failure of resorption and remodeling of the skull bones produces narrowing of the skull foramina that press on the various cranial nerves and results in optic nerve atrophy and blindness, deafness, and facial paralysis. In spite of the dense bone, pathologic fractures are common. Osteomyelitis of the jaws is a common complication of tooth extraction (Fig. 14-3).

Fig. 14-3 Osteopetrosis. This 24-year-old white man has the infantile form of osteopetrosis. He has mandibular osteomyelitis, and multiple draining fistulae are present on his face. (Courtesy of Dr. Dan Sarasin.)

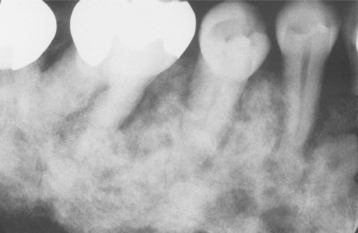

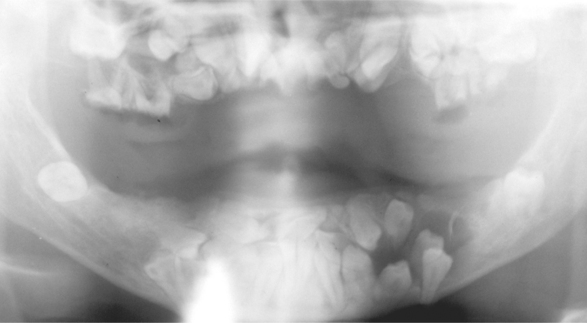

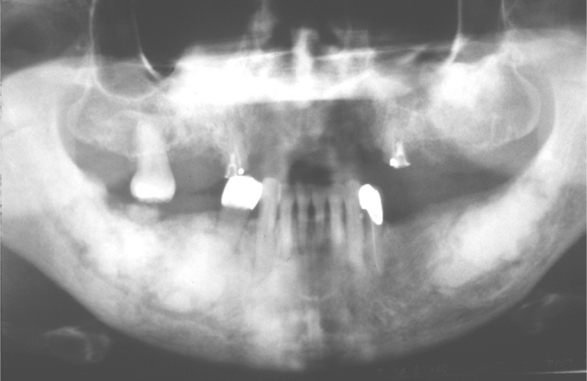

Radiographically, there is a widespread increase in skeletal density with defects in metaphyseal remodeling. The radiographic distinction between cortical and cancellous bone is lost (Fig. 14-4). In dental radiographs, the roots of the teeth often are difficult to visualize because of the density of the surrounding bone.

Fig. 14-4 Osteopetrosis. Extensive mandibular involvement is apparent in this radiograph of a 31-year-old woman. She received a diagnosis of osteopetrosis as a child. There is a history of multiple fractures and osteomyelitis of the jaws. (Courtesy of Dr. Dan Sarasin.)

Less severe variants of infantile osteopetrosis exist and have been termed intermediate osteopetrosis. Affected patients often are asymptomatic at birth but frequently exhibit fractures by the end of the first decade. Marrow failure and hepatosplenomegaly are rare.

In some cases, patients show radiographic evidence of diffuse sclerosis and associated marrow failure but resolve without specific therapy. This pattern has been termed transient osteopetrosis. and most affected patients return to normalcy with no known sequelae.

ADULT OSTEOPETROSIS: Adult osteopetrosis is usually discovered later in life and exhibits less severe manifestations. In most patients, this pattern is inherited as an autosomal dominant trait and has been termed benign osteopetrosis. The axial skeleton usually reveals significant sclerosis, whereas the long bones demonstrate little or no defects. Approximately 40% of affected patients are asymptomatic, and marrow failure is rare. Occasionally, the diagnosis is discovered initially on review of dental radiographs that reveal a diffuse increased radiopacity of the medullary portions of the bone. In symptomatic patients, bone pain is frequent.

Two major variants of adult osteopetrosis are seen. In one form, cranial nerve compression is common, although fractures occur rarely. In contrast, the second pattern demonstrates frequent fractures, but nerve compression is uncommon. When the mandible is involved, fracture and osteomyelitis after tooth extraction are significant complications.

Although distinctly uncommon, other causes of widespread osteosclerosis exist and should be considered during evaluation of patients with osteopetrosis. Such diseases include autosomal dominant osteosclerosis (endosteal hyperostosis, Worth type), sclerosteosis, and Van Buchem disease.

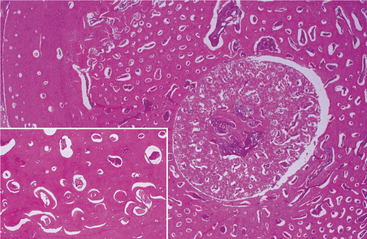

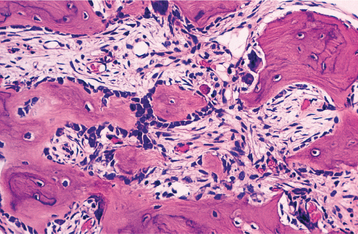

HISTOPATHOLOGIC FEATURES: Several patterns of abnormal endosteal bone formation have been described. These include the following:

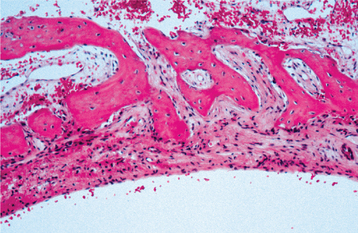

• Tortuous lamellar trabeculae replacing the cancellous portion of the bone

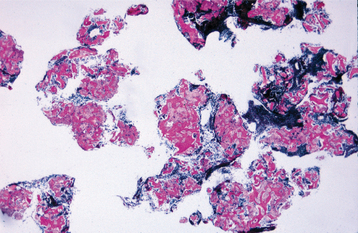

• Globular amorphous bone deposition in the marrow spaces (Fig. 14-5)

Numerous osteoclasts may be seen, but there is no evidence that they function because Howship’s lacunae are not visible.

TREATMENT AND PROGNOSIS: Because of the mild severity of the disease, adult osteopetrosis is usually associated with long-term survival. In contrast, the prognosis of infantile osteopetrosis without therapy is typically poor, with most affected patients dying during the first decade of life. Bone marrow transplantation is the only hope for permanent cure. However, an appropriately matched donor is available for only about half of affected patients, and successful engraftment occurs in only approximately 45% of those receiving bone marrow transplantation.

Because of the unavailability or risk of bone marrow transplantation, search for other therapies is ongoing. Interferon gamma-1b, often in combination with calcitriol, has been shown to reduce bone mass, decrease the prevalence of infections, and lower the frequency of nerve compression. Other therapeutic avenues include administration of corticosteroids (to increase circulating red blood cells and platelets), parathormone, macrophage colony stimulating factor, and erythropoietin. Limiting calcium intake also has been suggested.

Additional therapy consists of supportive measures, such as transfusions and antibiotics for the complications. Osteomyelitis of the jaws requires rapid intervention to minimize osseous destruction. Affected patients should receive early diagnosis, appropriate drainage and surgical débridement, bacterial culture with sen-sitivity, appropriate antibiotic therapy, and recon-struction if necessary. The infection often requires prolonged antibiotic therapy, with fluoroquinolones and lincomycin often being most effective. Hyperbaric oxygen is useful in promoting healing of recalcitrant cases.

CLEIDOCRANIAL DYSPLASIA

Best known for its dental and clavicular abnormalities, cleidocranial dysplasia is a disorder of bone caused by a defect in the CBFA1 gene (also known as the RUNX2 gene) of chromosome 6p21. This gene normally guides osteoblastic differentiation and appropriate bone formation. This condition initially was thought to involve only membranous bones (e.g., clavicles, skull, flat bones), but it is now known to affect endochondral ossification and to represent a generalized disorder of skeletal structures. Recent evidence suggests that the CBFA1 gene additionally plays an important role in odontogenesis via participation in odontoblast differentiation, enamel organ formation, and dental lamina proliferation. Disruption of these functions might explain the distinct dental anomalies found in patients with this disorder. The disease has an estimated prevalence of 1:1,000,000 and shows an autosomal dominant inheritance pattern, but as many as 40% of cases appear to represent spontaneous mutations. This condition formerly was known as cleidocranial dysostosis.

CLINICAL AND RADIOGRAPHIC FEATURES: The bone defects in patients with cleidocranial dysplasia chiefly involve the clavicles and skull, although a wide variety of anomalies may be found in other bones. The clavicles are absent, either unilaterally or bilaterally, in about 10% of all cases. More commonly, the clavicles show varying degrees of hypoplasia and malformation.

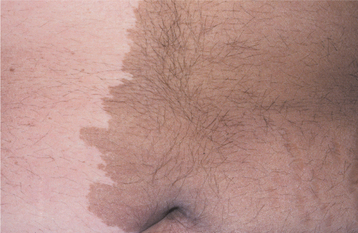

The muscles associated with the abnormal clavicles are underdeveloped. The patient’s neck appears long; the shoulders are narrow and show marked drooping. The absence or hypoplasia of the clavicles leads to an unusual mobility of the patient’s shoulders. In some instances, the patient can approximate the shoulders in front of the chest (Fig. 14-6). Although the clavicular defects result in variations of the associated muscles, function is remarkably good.

Fig. 14-6 Cleidocranial dysplasia. Patient can almost approximate her shoulders in front of her chest. (Courtesy of Dr. William Bruce.)

The appearance of the patient affected by cleidocranial dysplasia often is diagnostic. The patients tend to be of short stature and have large heads with pronounced frontal and parietal bossing. Ocular hypertelorism and a broad base of the nose with a depressed nasal bridge often are noted. On skull radiographs, the sutures and fontanels show delayed closure or may remain open throughout the patient’s life. Secondary centers of ossification appear in the suture lines, and many wormian bones may be seen. Abnormal development of the temporal bone and eustachian tube may lead to conductive or sensorineural hearing loss.

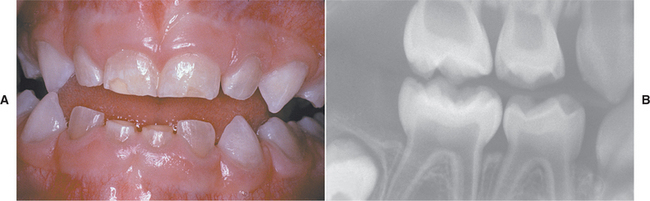

The gnathic and dental manifestations are distinctive and may lead to the initial diagnosis. The patients often have a narrow, high-arched palate, and there is an increased prevalence of cleft palate. Prolonged retention of deciduous teeth and delay or complete failure of eruption of permanent teeth are characteristic features. There may be abnormal spacing in the mandibular incisor area because of widening of the alveolar bone. On review of dental radiographs, the most dramatic finding is the presence of numerous unerupted permanent and supernumerary teeth, many of which frequently exhibit distorted crown and root shapes (Fig. 14-7). The number of supernumerary teeth can be impressive, with reports of some patients demonstrating more than 60 such teeth.

Fig. 14-7 Cleidocranial dysplasia. Panoramic radiograph showing multiple unerupted teeth. (Courtesy of Dr. John R. Cramer.)

In addition to the dental alterations, review of panoramic radiographs reveals an increased prevalence of a number of additional osseous malformations. The mandible often demonstrates coarse trabeculation with areas of increased density. The mandibular rami are often narrow with nearly parallel-sided anterior and posterior borders, and the coronoid processes may be slender and pointed with a distal curvature. In some cases the mandibular symphysis remains patent. The maxilla often is associated with a thin zygomatic arch and small or absent maxillary sinuses.

Although young patients typically exhibit a relatively normal jaw relationship, as the individuals age, a short lower face height, acute gonial angle, anterior inclination of the mandible, and mandibular prognathism develop. Clinicians believe that these changes may be from inadequate vertical growth of the maxilla and hypoplastic alveolar ridge development caused by delay or lack of eruption of the permanent teeth.

Computed tomography (CT) studies have demonstrated a decreased thickness of the masseter muscle in some patients. This finding may be related to hypoplasia of the zygomatic arch resulting in hypofunction of the attached masseter muscle.

HISTOPATHOLOGIC FEATURES: The reason for failure of permanent tooth eruption in patients with cleidocranial dysplasia is not understood well. Microscopic studies of unerupted permanent teeth have shown that these teeth lack secondary cementum. However, a recent histomorphometric study demonstrated no statistically significant difference in the percentage of root surface covered by cementum between teeth extracted from a patient with cleidocranial dysplasia and teeth from control patients. Some investigators alternatively have proposed that insufficient alveolar bone resorption is the reason for impaired tooth eruption; this theory is based on observations of decreased osteoclasts in the alveolar bone of heterozygous CBFA1 knockout mice.

TREATMENT AND PROGNOSIS: No treatment exists for the skull, clavicular, and other bone anomalies associated with cleidocranial dysplasia. Most patients function well without any significant problems. It is not unusual for an affected individual to be unaware of the disease until some professional calls it to his or her attention.

Treatment of the dental problems associated with the disease, however, may be a major problem. Therapeutic options include full-mouth extractions with denture construction, autotransplantation of selected impacted teeth followed by prosthetic restoration, or removal of primary and supernumerary teeth followed by exposure of permanent teeth that are subsequently extruded orthodontically. The latter mode of therapy appears to be the treatment of choice; if performed before adulthood, then it can prevent the short lower face height and mandibular prognathism.

FOCAL OSTEOPOROTIC MARROW DEFECT

The focal osteoporotic marrow defect is an area of hematopoietic marrow that is sufficient in size to produce an area of radiolucency that may be confused with an intraosseous neoplasm. The area does not represent a pathologic process, but its radiographic features may be confused with a variety of pathoses. The pathogenesis of this condition is unknown. Various theories include the following:

• Aberrant bone regeneration after tooth extrac-tion

• Marrow hyperplasia in response to increased demand for erythrocytes

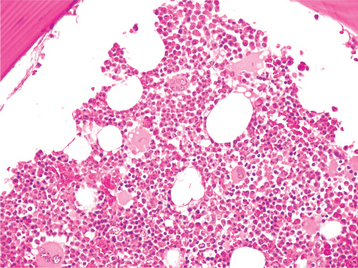

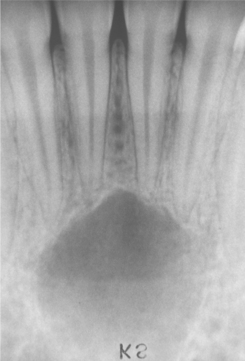

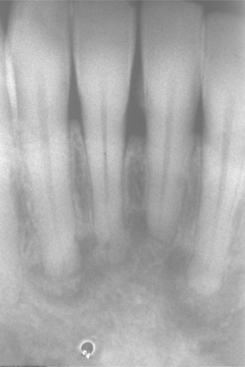

CLINICAL AND RADIOGRAPHIC FEATURES: The focal osteoporotic marrow defect is typically asymptomatic and detected as an incidental finding on a radiographic examination. The area appears as a radiolucent lesion, varying in size from several millimeters to several centimeters in diameter. In many instances, when discovered in panoramic radiographs, the area appears radiolucent and somewhat circumscribed; however, on review of more highly detailed periapical radiographs, the defect typically exhibits ill-defined borders and fine central trabeculations (Fig. 14-8). More than 75% of all cases are discovered in adult women. About 70% occur in the posterior mandible, most often in edentulous areas. No expansion of the jaw is noted clinically.

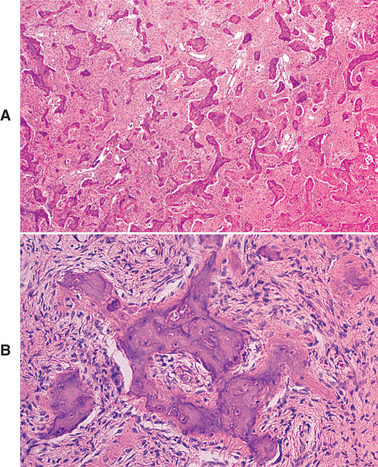

HISTOPATHOLOGIC FEATURES: Microscopically, the defects contain cellular hematopoietic and/or fatty marrow. Lymphoid aggregates may be present. Bone trabeculae included in the biopsy specimen show no evidence of abnormal osteoblastic or osteoclastic activity (Fig. 14-9).

TREATMENT AND PROGNOSIS: The radiographic findings, although often suggestive of the diagnosis, are not specific and may simulate those of a variety of other diseases. Incisional biopsy, therefore, often is necessary to establish the diagnosis.

Once the diagnosis is established, no further treatment is needed. The prognosis is excellent, and no association between focal osteoporotic marrow defects and anemia or other hematologic disorders has been established.

IDIOPATHIC OSTEOSCLEROSIS

Idiopathic osteosclerosis refers to a focal area of increased radiodensity that is of unknown cause and cannot be attributed to any inflammatory, dysplastic, neoplastic, or systemic disorder. Idiopathic osteosclerosis also has been termed dense bone island, bone eburnation, bone whorl, bone scar, enostosis, and focal periapical osteopetrosis. These sclerotic areas are not restricted to the jaws, and radiographically similar lesions may be found in other bones.

Similar radiopaque foci may develop in the periapical areas of teeth with nonvital or significantly inflamed pulps; these lesions most likely represent a response to a low-grade inflammatory stimulus. Such reactive foci should be designated as condensing osteitis or focal chronic sclerosing osteomyelitis (see page 147) and should not be included under the designation of idiopathic osteosclerosis. Because past studies did not distinguish the idiopathic lesions from those of inflammatory origin, confusion in terminology has resulted.

CLINICAL AND RADIOGRAPHIC FEATURES: Although previous studies often are difficult to interpret because of differences in diagnostic criteria, the prevalence appears to be approximately 5%, with some investigators suggesting a slightly increased frequency in blacks and Asians. No significant sex predilection is seen.

On review of several studies with long-term follow-up, a pattern has emerged. Although exceptions can be seen, most areas of idiopathic osteosclerosis arise in the late first or early second decade. Once noted, the lesions may remain static, but many reveal a slow increase in size. In almost all cases, once the patient reaches full maturity, all enlargement ceases and the sclerotic area stabilizes. In a smaller percentage, the lesion diminishes or undergoes complete regression. The peak prevalence of osteosclerosis occurs in the third decade, with the attainment of peak bone mass seen in the fourth decade.

Idiopathic osteosclerosis is invariably asymptomatic, not associated with detectable cortical expansion, and is typically detected during a routine radiographic examination. About 90% of examples are seen in the mandible, most often in the first molar area. The second premolar and second molar areas also are common sites. In most cases, only one focus of sclerotic bone is present. A small number of patients have two or even three separate areas of involvement. For patients with multiple areas of involvement, the possibility of multiple osteomas within the setting of Gardner syndrome (see page 651) should be excluded.

Radiographically, the lesions are characterized by a well-defined, rounded, or elliptic radiodense mass. Although the majority is uniformly radiopaque, occasional large lesions demonstrate a nonhomogeneous mixture of increased and reduced radiopacity. This is most likely because of variation in the three-dimensional (3D) shape of the lesion and is unrelated to differences in the mineral content of the mass. The lesions vary from 3.0 mm to more than 2.0 cm in greatest extent. A radiolucent rim does not surround the radiodense area. Most examples of idiopathic osteosclerosis are associated with a root apex. In a lesser number of cases, the sclerotic area may extend into or be located only in the interradicular area (Fig. 14-10). In about 20% of cases, the sclerotic area is located in the jaw, with no apparent relationship to a tooth. Rarely, the sclerotic bone may surround all or portions of an impacted tooth. Root resorption and movement of teeth have been noted but are uncommon.

HISTOPATHOLOGIC FEATURES: In the few microscopic studies that have been reported, the lesion consists of dense lamellar bone with scant fibrofatty marrow. Inflammatory cells are inconspicuous or absent.

DIAGNOSIS: Usually a diagnosis of idiopathic osteosclerosis may be made with confidence, based on history, clinical features, and radiographic findings. Biopsy is considered only if associated symptoms or significant cortical expansion is present. Although idiopathic osteosclerosis demonstrates radiographic and histopathologic similarities with a compact osteoma (see page 650), the lack of cortical expansion and failure of continued growth rule against a neoplastic process. Differentiation from condensing osteitis may be difficult; however, in the absence of a deep restoration or caries, a periapical radiodense area associated with a vital tooth is likely to represent idiopathic osteosclerosis.

TREATMENT AND PROGNOSIS: If the lesion is discovered during adolescence, periodic radiographs appear prudent until the area stabilizes. After that point, no treatment is indicated for idiopathic osteosclerosis, because there is little or no tendency for the lesions to progress or change in adulthood.

MASSIVE OSTEOLYSIS (GORHAM DISEASE; GORHAM-STOUT SYNDROME; VANISHING BONE DISEASE; PHANTOM BONE DISEASE)

Massive osteolysis is a rare disease that is char-acterized by spontaneous and usually progressive destruction of one or more bones. The destroyed bone initially is replaced by a vascular proliferation. The affected area does not regenerate or repair itself; eventually, the site of destruction fills with dense fibrous tissue.

The cause of massive osteolysis is unknown. There is no evidence of any underlying metabolic or endocrine imbalance. Hyperactivity of osteoclasts initially was proposed to be the major pathogenetic mechanism underlying this disease. However, many investigators also believe that massive osteolysis is primarily related to a proliferation of blood or lymphatic vessels that is occasionally multicentric and has been termed angiomatosis of bone.

CLINICAL AND RADIOGRAPHIC FEATURES: Although massive osteolysis has been documented in patients up to 70 years of age, most affected patients are children and young adults. About 50% of all patients report an episode of trauma before the diagnosis, but this is often trivial in nature. Lesions have occurred in almost any bone or combination of bones. The most commonly involved sites are the pelvis, humeral head, humeral shaft, and axial skeleton. Generally, the results of laboratory studies are completely within normal limits.

In approximately 30% of affected patients, maxillofacial involvement is noted, with the mandible being affected most frequently. Simultaneous involvement of the maxilla and mandible may occur. Signs and symptoms include mobile teeth, pain, malocclusion, deviation of the mandible, and clinically obvious deformity. Obstructive sleep apnea syndrome has been noted secondary to posterior mandibular displacement after extensive osteolysis. Pathologic fracture of the mandible may occur. Temporomandibular joint (TMJ) involvement may be confused with other conditions that can cause TMJ dysfunction.

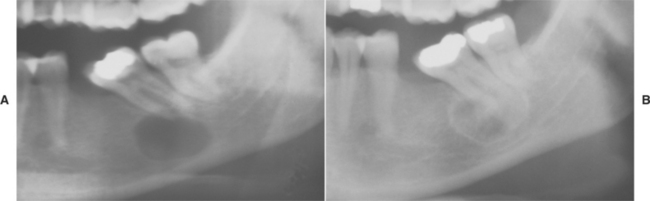

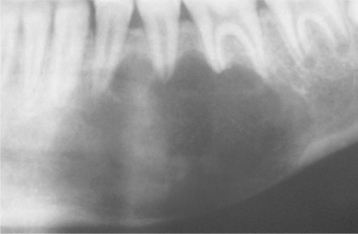

Radiographically, the earliest changes consist of intramedullary radiolucent foci of varying size with indistinct margins (Fig. 14-11). These coalesce to become larger and involve the cortical bone. Eventually, large portions of the involved bone disappear (Fig. 14-12). As the process proceeds, newly involved areas often demonstrate loss of the lamina dura and thinning of the cortical plates before development of obvious radiolucency. In some cases the bone destruction may mimic periodontitis or periapical inflammatory disease.

Fig. 14-11 Massive osteolysis. Periapical radiograph showing an ill-defined radiolucency associated with vital mandibular teeth. Note the loss of lamina dura. (Courtesy of Dr. John R. Cramer.)

Fig. 14-12 Massive osteolysis. Panoramic radiograph of the same patient shown in Fig. 14-11, showing extensive bone loss and a pathologic fracture of the left mandible. This destruction occurred over an 8-month period. (Courtesy of Dr. John R. Cramer.)

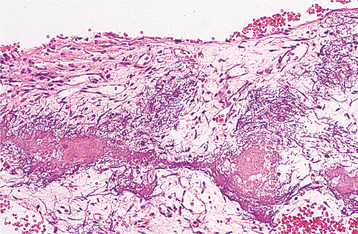

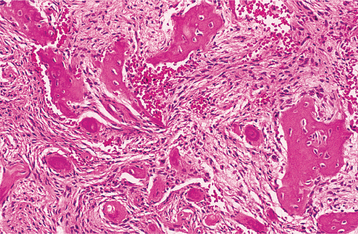

HISTOPATHOLOGIC FEATURES: The microscopic findings in massive osteolysis contrast sharply with the striking clinical and radiographic findings. In the early stages of disease, specimens removed from the radiolucent defects consist of a nonspecific vascular proliferation intermixed with fibrous connective and a chronic inflammatory infiltrate of lymphocytes and plasma cells. The vascular proliferation varies in intensity and is characterized by thin-walled channels that may be capillary or cavernous in nature (Fig. 14-13). Osteoclastic reaction in the adjacent bone fragments is usually not conspicuous.

Fig. 14-13 Massive osteolysis. Biopsy specimen from the same patient shown in Figs. 14-11 and 14-12. The loose, highly vascular connective tissue shows a diffuse chronic inflammatory cell infiltrate.

In the later stages, tissue from the area of bone loss is more collagenized. Evidence of repair by new bone formation is not seen.

TREATMENT AND PROGNOSIS: The clinical course of massive osteolysis is variable and impossible to predict. In most cases, bone destruction progresses over months to a few years and results in the total loss of the affected bone or bones. Some patients, however, experience a spontaneous arrest of the process without complete loss of the affected bone. The prognosis varies from slight to severe disability. Mortality from massive osteolysis is relatively uncommon and usually the result of severe chest cage involvement or destruction of vertebral bodies with spinal cord compression.

Treatment is not particularly satisfactory. Previous reported therapies include estrogens, magnesium, calcium, vitamin D, fluoride, calcitonin, alpha-2b interferon, and chemotherapeutic agents (e.g., cisplatin, actinomycin D, etoposide). Surgical intervention has met with limited success. When surgical removal is combined with bone grafting, the newly placed bone often undergoes osteolysis. Radiation therapy is the most successful and widely accepted mode of therapy, but failures may occur. In addition, this therapy places the patient at risk for postirradiation sarcoma. In a limited number of patients, stabilization of disease after bisphosphonate therapy has been reported, although longer-term studies on a greater number of patients are needed to assess this proposed treatment modality. The effectiveness of any therapeutic intervention is difficult to evaluate, not only because the disease is so rare but also because the condition may arrest spontaneously in some patients.

PAGET’S DISEASE OF BONE (OSTEITIS DEFORMANS)

Paget’s disease of bone is a condition characterized by abnormal and anarchic resorption and deposition of bone, resulting in distortion and weakening of the affected bones. The cause of Paget’s disease is unknown, but inflammatory, genetic, and endocrine factors may be contributing agents. In some studies, 15% to 40% of affected patients have a positive family history of the disease. In recent years, recurrent mutations in the sequestosome 1 gene (SQSTM1) (also known as p62), which participates in the regulation of osteoclastic activity via the nuclear factor-kB (NF-kB) transcription activation pathway, have been identified in both familial and sporadic cases of the disease. Mutations in another gene involved in the NF-kB signaling pathway, the valosin-containing protein (VCP) gene, have been found in patients with a rare hereditary syndrome that includes Paget’s disease of bone, inclusion body myopathy, and frontotemporal dementia. In addition, the possibility that Paget’s disease is the result of a slow virus infection has received considerable attention, but a viral cause remains unproven. Inclusion bodies identified as nucleocapsids from a paramyxovirus have been detected in osteoclasts in patients with Paget’s disease, but a cause-and-effect relationship has not been established.

CLINICAL AND RADIOGRAPHIC FEATURES: Paget’s disease is relatively common, although there is a marked geographic variance in its prevalence. It is more common in Britain than in the United States, whereas it is rare in Africa and Asia. The disease principally affects older adults and is rarely encountered in patients younger than 40 years of age. Men are affected more often than women, and whites are affected more frequently than blacks. Reviews have estimated that 1 in 100 to 150 individuals older than 45 years of age have Paget’s disease. Subclinical disease is not rare, and an increased number of cases are being seen as the population ages. Asymptomatic disease often is discovered in radiographs taken for unrelated reasons or from an unexpected elevation in serum alkaline phosphatase. The frequency increases with age, and the true prevalence (including undiscovered subclinical disease) probably ranges from 1% in the fifth decade to 10% in the tenth decade.

Although the disease may be monostotic (i.e., limited to one bone), most cases of Paget’s disease are polyostotic (i.e., more than one bone is affected). Symptoms vary, and some patients may remain relatively asymptomatic. Bone pain, which may be quite severe, is a common complaint. In addition, pagetic bone often forms near joints and promotes osteoarthritic changes, with associated joint pain and limited mobility.

The lumbar vertebrae, pelvis, skull, and femur are the most commonly affected bones. Affected bones become thickened, enlarged, and weakened. Involvement of weight-bearing bones often leads to a bowing deformity, resulting in what is described as a simian (monkeylike) stance. Paget’s disease affecting the skull generally leads to a progressive increase in the circumference of the head.

Jaw involvement is present in approximately 17% of patients diagnosed with Paget’s disease. Maxillary disease, which is far more common than mandibular involvement, results in enlargement of the middle third of the face. In extreme cases, the alteration results in a lionlike facial deformity (leontiasis ossea). Nasal obstruction, enlarged turbinates, obliterated sinuses, and deviated septum may develop secondary to maxillary involvement. The alveolar ridges tend to remain symmetrical but become grossly enlarged. If the patient is dentulous, then the enlargement causes spacing of the teeth. Edentulous patients may complain that their dentures no longer fit because of the increased alveolar size.

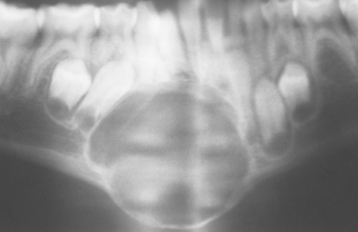

Radiographically, the early stages of Paget’s disease reveal a decreased radiodensity of the bone and alteration of the trabecular pattern. Particularly in the skull, large circumscribed areas of radiolucency may be present (osteoporosis circumscripta). During the osteoblastic phase of the disease, patchy areas of sclerotic bone are formed, which tend to become confluent. The patchy sclerotic areas often are described as having a “cotton wool” appearance (Figs. 14-14 and 14-15). On radiographic examination, the teeth often demonstrate extensive hypercementosis.

Fig. 14-14 Paget’s disease. Lateral skull film shows marked enlargement of the cranium with new bone formation above the outer table of the skull and a patchy, dense, “cotton wool” appearance. (Courtesy of Dr. Reg Munden.)

On initial discovery of Paget’s disease, bone scintigraphy should be performed to evaluate fully the extent of involvement. When the mandible is affected, the bone scan may demonstrate marked uptake throughout the entire mandible from condyle to condyle, a feature that has been termed black beard or Lincoln’s sign.

Radiographic findings of Paget’s disease may resemble those of cemento-osseous dysplasia (see page 640). Patients with presumed cemento-osseous dysplasia who demonstrate clinical expansion of the jaws should be evaluated further to rule out Paget’s disease.

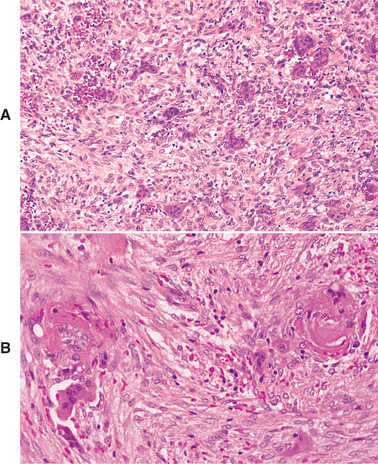

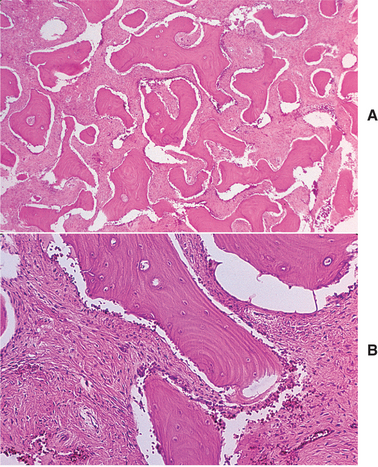

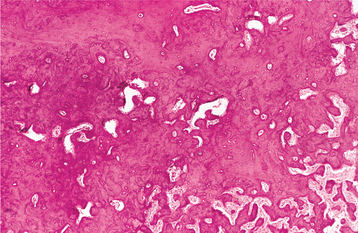

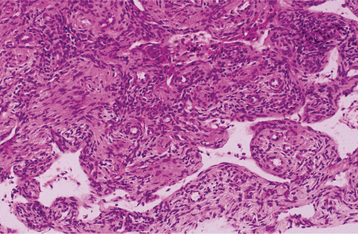

HISTOPATHOLOGIC FEATURES: Microscopic examination shows an apparent uncontrolled alternating resorption and formation of bone. In the active resorptive stages, numerous osteoclasts surround bone trabeculae and show evidence of resorptive activity. Simultaneously, osteoblastic activity is seen with formation of osteoid rims around bone trabeculae. A highly vascular fibrous connective tissue replaces the marrow. A characteristic microscopic feature is the presence of basophilic reversal lines in the bone. These lines indicate the junction between alternating resorptive and formative phases of the bone and result in a “jigsaw puzzle,” or “mosaic,” appearance of the bone (Fig. 14-16). In the less active phases, large masses of dense bone showing prominent reversal lines are present.

DIAGNOSIS: Patients with Paget’s disease show high elevations in serum alkaline phosphatase levels but usually have normal blood calcium and phosphorus levels. Although serum bone-specific alkaline phosphatase is consid-ered the most sensitive marker of bone formation, it is not widely available; thus total serum alkaline phosphatase is typically used in routine clinical practice. However, because serum alkaline phosphatase also may be elevated in other conditions, such as cholelithiasis, other laboratory studies are indicated to confirm the diagnosis. Urinary hydroxyproline levels often are markedly elevated, although it is recognized that hydroxyproline often breaks down before excretion, making it a less precise method for measurement of bone resorption. Newer and more sensitive markers of bone resorption are N-telopeptides, C-telopeptides, and pyridinoline cross-link assays. The clinical and radiographic features, combined with supportive laboratory findings, are typically sufficient for diagnosis. Histopathologic examination can be confirmatory but often is unnecessary for a strong presumptive diagnosis.

TREATMENT AND PROGNOSIS: Although Paget’s disease is chronic and slowly progressive, it is seldom the cause of death. In patients with more limited involvement and no symptoms, treatment often is not required. In asymptomatic patients, systemic therapy is usually not initiated unless the alkaline phosphatase is more than 25% to 50% above normal. When symptomatic, bone pain is noted most frequently and often may be controlled by acetaminophen or nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs (NSAIDs). Neurologic complications, such as deafness or visual disturbances, may result from bony encro-achment on cranial nerves passing through skull foramina.

Pharmacologic antiresorptive therapy is recommended for patients with the following signs or symptoms: considerable bone pain, headache related to skull involvement, deafness or visual disturbances because of narrowing of the skull foramina, back pain because of pagetic radiculopathy or arthropathy, bone fractures, and hypercalcemia resulting from immobilization. Use of parathyroid hormone (PTH) antagonists, such as calcitonin and bisphosphonates, can reduce bone turnover and improve the biochemical abnormalities. For several decades, the mainstays of therapy were calcitonin and the bisphosphonate etidronate. However, these agents have been largely supplanted by the newer bisphosphonates, alendronate and risedronate, which provide enhanced control of bone turnover. Bisphosphonates are typically administered orally for a period of 2 to 6 months. Intravenous pamidronate can be an alternative for those patients who cannot tolerate oral bisphosphonates because of gastrointestinal irritation or who require treatment before surgery in an area of pagetic bone. A recently reported regimen of notable efficacy is single-infusion therapy with the potent bisphosphonate, zoledronic acid. In mild cases, a single infusion of a bisphosphonate often is associated with yearlong remissions. Patients with more severe disease usually require higher doses or more frequent courses of a particular bisphosphonate. The goal of therapy is to achieve midrange normal levels of serum alkaline phosphatase, with retreatment occurring when values rise 25% higher than normal. Plicamycin, a cytotoxic antibiotic, is known to inhibit osteoclastic activity, but its use is restricted to patients with severe disease that is refractory to calcitonin and bisphosphonate medications.

Case reports of osteonecrosis of the jaw as a complication of bisphosphonate therapy for Paget’s disease of bone have raised some safety concerns. Long-term data are needed to fully assess the potential risks and benefits of bisphosphonate therapy; thus the merits of aggressive preventive or prolonged maintenance therapy remain uncertain at this time.

Edentulous patients may require new and larger dentures periodically to compensate for progressive enlargement of the alveolar processes. Dental complications include difficulties in extraction of teeth exhibiting significant hypercementosis. During active disease, pagetoid bone is extremely vascular with multiple arteriovenous shunts. Oral surgical procedures during this time can result in extensive hemorrhage. During the later sclerotic phase, the bone is hypersensitive to inflammation and can develop osteomyelitis with minimal provocation. In one recent report, long-term correction of maxillary deformity was achieved by removal, reshaping, and reinsertion of the maxillomalar complex in a patient who had received no prior medical treatment for his disease.

Development of a malignant bone tumor, usually an osteosarcoma, is a recognized complication of Paget’s disease. Osteosarcoma in adults older than 40 years is quite uncommon in individuals who do not have Paget’s disease. The frequency of bone sarcoma complicating Paget’s disease ranges from 0.9% to 13.0% in various studies. The true frequency is probably in the range of 1% or less. Most of the osteosarcomas develop in the pelvis and long bones of the lower extremities. The skull and jaws are very rare sites for sarcomas associated with Paget’s disease. Clinical signs and symptoms that should raise suspicion of possible underlying malignancy include the development of constant and worsening bone pain, a new mass, or sudden fracture. Osteosarcoma in Paget’s disease is very aggressive and associated with a poor prognosis. Although survival rates generally have improved over the last several decades for patients with nonpagetoid osteosarcoma, no significant improvement in survival has been observed among patients with Paget’s-related osteosarcoma. Benign and malignant giant cell tumors (see page 629) also may develop in bones affected by Paget’s disease. Most of these occur in the craniofacial skeleton.

CENTRAL GIANT CELL GRANULOMA (GIANT CELL LESION; GIANT CELL TUMOR)

The giant cell granuloma is considered widely to be a nonneoplastic lesion. Although formerly designated as giant cell reparative granuloma, there is little evidence that the lesion represents a reparative response. Some lesions demonstrate aggressive behavior similar to that of a neoplasm. Most oral and maxillofacial pathologists have dropped the term reparative; today, these lesions are designated as giant cell granuloma or by the more noncommittal term, giant cell lesion. Whether or not true giant cell tumors occur in the jaws is uncertain and controversial. (This topic is discussed later in the chapter.) Likewise, it is not certain whether some reported cases of extragnathic giant cell granulomas actually represent true giant cell tumors.

CLINICAL AND RADIOGRAPHIC FEATURES: Giant cell granulomas may be encountered in patients ranging from 2 to 80 years of age, although more than 60% of all cases occur before age 30. Although the sex ratio varies in different reviews, a majority of giant cell granulomas are noted in females, and approximately 70% arise in the mandible. Lesions are more common in the anterior portions of the jaws, and mandibular lesions frequently cross the midline.

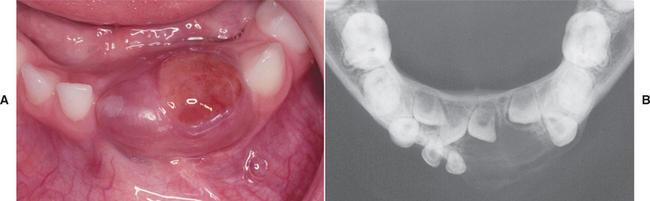

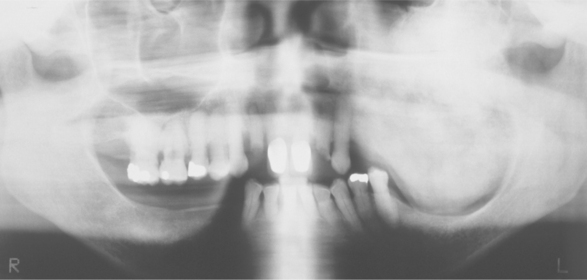

Most giant cell granulomas of the jaws are asymptomatic and first come to attention during a routine radiographic examination or as a result of painless expansion of the affected bone. A minority of cases, however, may be associated with pain, paresthesia, or perforation of the cortical bone plate, occasionally resulting in ulceration of the mucosal surface by the underlying lesion (Fig. 14-17).

Fig. 14-17 Central giant cell granuloma. A, A blue-purple mass is present on the anterior alveolar ridge of this 4-year-old white boy. B, The occlusal radiograph shows a radiolucent lesion with cortical expansion.

Based on the clinical and radiographic features, several groups of investigators have suggested that central giant cell lesions of the jaws may be divided into two categories:

1. Nonaggressive lesions make up most cases, exhibit few or no symptoms, demonstrate slow growth, and do not show cortical perforation or root resorption of teeth involved in the lesion.

2. Aggressive lesions are characterized by pain, rapid growth, cortical perforation, and root resorption. They show a marked tendency to recur after treatment, compared with the non-aggressive types.

Radiographically, central giant cell lesions appear as radiolucent defects, which may be unilocular or multilocular. The defect is usually well delineated, but the margins are generally noncorticated. The lesion may vary from an incidental radiographic finding of 5 × 5 mm to a destructive lesion greater than 10 cm in size (Fig. 14-18). The radiographic findings are not specifically diagnostic. Small unilocular lesions may be confused with periapical granulomas or cysts (Fig. 14-19). Multilocular giant cell lesions cannot be distinguished radiographically from ameloblastomas or other multilocular lesions.

Fig. 14-18 Central giant cell granuloma. Panoramic radiograph showing a large, expansile radiolucent lesion in the anterior mandible. (Courtesy of Dr. Gregory R. Erena.)

Fig. 14-19 Central giant cell granuloma. The periapical radiograph shows a radiolucent area involving the apex of an endodontically treated tooth. This was considered preoperatively to represent a periapical granuloma or periapical cyst.

Areas histopathologically identical to giant cell granuloma have been noted in aneurysmal bone cysts (see page 634) and intermixed with central odontogenic fibromas (see page 727). Because giant cell granulomas are also histopathologically identical to brown tumors, hyperparathyroidism (see page 838) should be ruled out in all instances. In addition, multifocal involvement in childhood suggests cherubism (see next section) and warrants further investigation. Most giant cell granulomas are single lesions; rarely, multifocal involvement is seen in patients who demonstrate no evidence of an associated disease, such as hyperparathyroidism or cherubism.

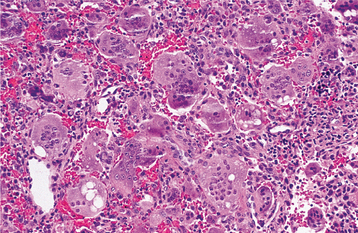

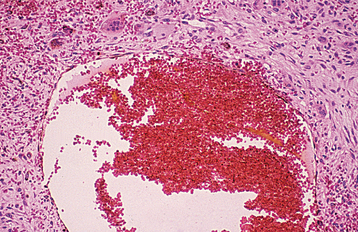

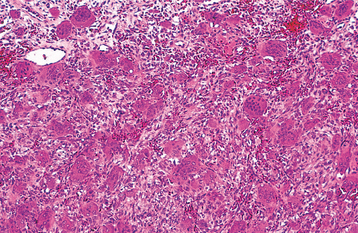

HISTOPATHOLOGIC FEATURES: Giant cell lesions of the jaw show a variety of features. Common to all is the presence of few to many multinucleated giant cells in a background of ovoid to spindle-shaped mesenchymal cells and round monocyte-macrophages (Fig. 14-20). There is evidence that these giant cells represent osteoclasts, although others suggest the cells may be aligned more closely with macrophages. The spindle-shaped cells appear to be fibroblast related. It has been proposed that the spindle cell component is the proliferating cell population and recruits monocyte-macrophage precursors, inducing them to differentiate into osteoclastic giant cells by activation of the receptor activator of the nuclear factor-kB (RANK)/RANK ligand signaling pathway. The giant cells may be aggregated focally in the lesional tissue or may be present diffusely throughout the lesion. These cells vary considerably in size and shape from case to case. Some are small and irregular in shape and contain only a few nuclei. In other cases, the giant cells are large and round and contain 20 or more nuclei.

Fig. 14-20 Central giant cell granuloma. Numerous multinucleated giant cells within a background of plump proliferating mesenchymal cells. Note extensive red blood cell extravasation.

In some cases the stroma is loosely arranged and edematous; in other cases it may be quite cellular. Areas of erythrocyte extravasation and hemosiderin deposition often are prominent. Older lesions may show considerable fibrosis of the stroma. Foci of osteoid and newly formed bone are occasionally present within the lesion. Correlation of the histopathologic features with clinical behavior remains debatable, but lesions showing large, uniformly distributed giant cells and a predominantly cellular stroma appear more likely to be clinically aggressive with a greater tendency to recur after surgical treatment.

TREATMENT AND PROGNOSIS: Central giant cell lesions of the jaws are usually treated by thorough curettage. In reports of large series of cases, recurrence rates range from 11% to 50% or greater. Most studies indicate a recurrence rate of about 15% to 20%. Those lesions considered on clinical and radiologic grounds to be potentially aggressive show a higher frequency of recurrence. Many investigators have noted a propensity for recurrence among lesions in younger patients. Recurrent lesions often respond to further curettage, although some aggressive lesions require more radical surgery for cure.

In patients with aggressive tumors, three alternatives to surgery—(1) corticosteroids, (2) calcitonin, and (3) interferon alfa-2a—are being investigated. Several investigators have reported small numbers of patients, some of which exhibited remarkable response to these interventions. Weekly injections directly into the tumor with triamcinolone acetonide for approximately 6 weeks have been used successfully. Calcitonin typically is administered daily for approximately 12 months as an intradermal injection or nasal spray. Several cases of large lesions resolving with systemic administration of salmon calcitonin have been reported, although a recent randomized, double-blind, controlled clinical trial performed on a limited number of patients found no significant difference between the calcitonin-treated and placebo patient groups. Interferon alfa-2a, alone or in combination with surgery, also has been reported to result in resolution of large lesions. The response of central giant cell lesions to interferon alfa-2a has been proposed to be the result of this drug’s antiangiogenic properties, although speculation about the vascular nature of these lesions has not been proven. Clinicians should be aware of the potential side effects of interferon alfa-2a therapy, which can include flulike symptoms (e.g., fever, malaise, nausea, joint pain, weakness) and in rare cases more serious complications, including pancreatitis and drug-induced lupus erythematosus. The previously discussed medical therapeutic approaches provide possible alternatives for large lesions that if treated surgically would result in significant deformity. Evaluation of greater numbers of patients with appropriate controls is necessary to compare these therapeutic approaches to surgery adequately.

In spite of the reported recurrence rate, the long-term prognosis of giant cell granulomas is good and metastases do not develop.

Giant Cell Tumor

The question of whether true giant cell tumors, which most often occur in the epiphyses of long tubular bones, occur in the jaws has been argued for many years and still is unresolved. Although most central giant cell lesions can be distinguished histopathologically from the long bone tumors, a number of jaw lesions are indistinguishable microscopically from the typical giant cell tumor of long bone (Fig. 14-21). Despite the histopathologic similarity, these jaw lesions appear to have a biologically different behavior from long bone lesions, which have higher recurrence rates after curettage and show malignant change in up to 10% of cases. One case of metastasis from a mandibular tumor, however, has been reported. It has been suggested that giant cell granulomas of the jaws and giant cell tumors of the extragnathic skeleton are not distinct and separate entities; rather, they represent a continuum of a single disease process modified by the age of the patients, the locations of the lesions, and possibly other factors that are not yet understood.

CHERUBISM

Cherubism is a rare developmental jaw condition that is generally inherited as an autosomal dominant trait with high penetrance but variable expressivity. Several investigators have reported a higher disease penetrance in males than in females. Sporadic cases also can occur and are thought to represent spontaneous mutations. In two reports published simultaneously by laboratories on different continents, the gene for cherubism was mapped to chromosome 4p16. Mutations subsequently were identified in the SH3BP2 gene within this locus. The protein encoded by this gene is believed to function in signal transduction pathways and to increase the activity of osteoclasts and osteoblasts during normal tooth eruption. It has been suggested that mutations in the SH3BP2 gene may lead to pathologic activation of osteoclasts and disruption of jaw morphogenesis. However, the molecular pathogenesis of cherubism remains poorly understood.

The name cherubism was applied to this condition because the facial appearance is similar to that of the plump-cheeked little angels (cherubs) depicted in Renaissance paintings. Although cherubism also has been called familial fibrous dysplasia, this term should be avoided because cherubism has no relationship to fibrous dysplasia of bone (see page 635).

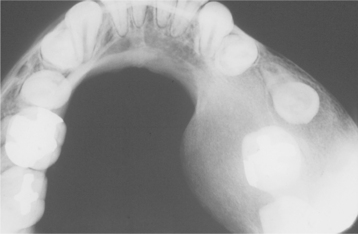

CLINICAL AND RADIOGRAPHIC FEATURES: Although some examples of cherubism may develop as early as 1 year of age, the disease usually occurs between the ages of 2 and 5 years. In mild cases the diagnosis may not be made until the patient reaches 10 to 12 years of age. The clinical alterations typically progress until puberty, then stabilize and slowly regress.

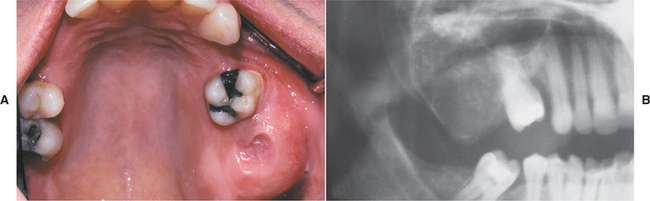

The cherublike facies arises from bilateral in-volvement of the posterior mandible that produces angelic chubby cheeks (Fig. 14-22). In addition, there is an “eyes upturned to heaven” appearance that is due to a wide rim of exposed sclerae noted below the iris. This latter feature is due to involvement of the infraorbital rim and orbital floor that tilts the eyeballs upward, as well as to stretching of the upper facial skin that pulls the lower lid downward. On occasion, affected patients also reveal marked cervical lymphadenopathy.

Fig. 14-22 Cherubism. This young girl shows the typical cherubic facies resulting from bilateral expansile mandibular and maxillary lesions. (Courtesy of Dr. Román Carlos.)

The mandibular lesions typically appear as a painless, bilateral expansion of the posterior mandible that tends to involve the angles and ascending rami. The bony expansion is usually bilaterally symmetrical; in severe cases, most of the mandible is involved. Milder maxillary involvement occurs in the tuberosity areas; in severe cases, the entire maxilla can be affected.

Extensive bone involvement causes a marked widening and distortion of the alveolar ridges. In addition to the aesthetic and psychologic effect, the enlargements may cause tooth displacement or failure of eruption, impair mastication, create speech difficulties, or rarely lead to loss of normal vision or hearing. Although there have been rare reports of unilateral cherubism, it is difficult to accept these as examples of this disease unless there is a strong family history.

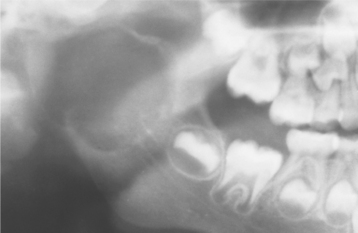

Radiographically, the lesions are typically multilocular, expansile radiolucencies (Fig. 14-23). The appearance is virtually diagnostic as a result of their bilateral location. Less commonly, the lesions appear as unilocular radiolucencies. Although cherubism typically involves only the jaws, involvement also has been reported rarely in other bones such as the ribs and humerus.

Fig. 14-23 Cherubism. A, Panoramic radiograph of a 7-year-old white boy. Bilateral multilocular radiolucencies can be seen in the posterior mandible. B, Same patient 6 years later. The lesions in the mandibular rami demonstrate significant resolution, but areas of involvement are still present in the body of the mandible. (Courtesy of Dr. John R. Cramer.)

No unusual biochemical findings have been reported in patients with cherubism. If laboratory results do not suggest the diagnosis of hyperparathyroidism, then most children with multiple symmetrical giant cell granulomas represent examples of cherubism. However, multiple giant cell lesions may be seen in association with other conditions, including Ramon syndrome, Jaffe-Campanacci syndrome, and a Noonan-like syndrome. It has been suggested that the bony lesions of cherubism represent a phenotypic picture common to a number of disease processes that arise from multiple, distinct, initiating pathogenetic events.

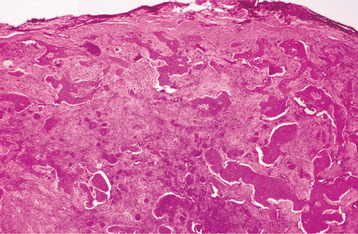

HISTOPATHOLOGIC FEATURES: The microscopic findings of cherubism are essentially similar to those of isolated giant cell granulomas, and they seldom permit a specific diagnosis of cherubism in the absence of clinical and radiologic information. The lesional tissue consists of vascular fibrous tissue containing variable numbers of multinucleated giant cells. The giant cells tend to be small and usually aggregated focally (Fig. 14-24). Like the giant cells in central giant cell granulomas, the giant cells in cherubism express markers suggestive of osteoclastic origin. Foci of extravasated blood are commonly present. The stroma in cherubism often tends to be more loosely arranged than that seen in giant cell granulomas. In some cases, cherubism reveals eosinophilic, cufflike deposits surrounding small blood vessels throughout the lesion. The eosinophilic cuffing appears to be specific for cherubism. However, these deposits are not present in many cases, and their absence does not exclude a diagnosis of cherubism. In older, resolving lesions of cherubism, the tissue becomes more fibrous, the number of giant cells decreases, and new bone formation is seen.

TREATMENT AND PROGNOSIS: The prognosis in any given case is unpredictable. In most instances the lesions tend to show varying degrees of remission and involution after puberty (see Fig. 14-23). By the fourth decade, the facial features of most patients approach normalcy. In spite of the typical scenario, some patients demonstrate very mild alterations, whereas others reveal grotesque changes that often are very slow to resolve. In occasional patients, the deformity can persist.

The question of whether to treat or simply observe a patient with cherubism is difficult. Excellent results have been obtained in some cases by early surgical intervention with curettage of the lesions. Conversely, early surgical intervention sometimes has been followed by rapid regrowth of the lesions and worsening deformity. A course limited only to observation may result in extreme and sometimes grotesque facial deformity, with associated psychologic problems and functional deformity that may necessitate extensive surgery. Several investigators have suggested the use of calcitonin in severe cases, but such therapy awaits further study. Radiation therapy is contraindicated because of the risk of development of postirradiation sarcoma. The optimal therapy for cherubism has not been determined.

SIMPLE BONE CYST (TRAUMATIC BONE CYST; HEMORRHAGIC BONE CYST; SOLITARY BONE CYST; IDIOPATHIC BONE CAVITY)

The simple bone cyst is a benign, empty, or fluid-containing cavity within bone that is devoid of an epithelial lining. The lesion is undoubtedly more common in the jaws than the literature would indicate. The cause and pathogenesis are uncertain and controversial. Several theories have been proposed, but none of them explains all of the clinical and pathologic features of this disease.

The trauma-hemorrhage theory has many advocates, as evidenced by the widely used designation traumatic bone cyst. This theory suggests that trauma to the bone that is insufficient to cause a fracture results in an intraosseous hematoma. If the hematoma does not undergo organization and repair, it may liquefy and result in a cystic defect. Some affected patients may recall an episode of trauma to the affected area, but this anecdotal information is of uncertain significance and has not been subjected to detailed, controlled analysis.

Although the trauma-hemorrhage theory appears to be accepted widely in the dental literature, it has little support in the orthopedic literature to explain similar cysts most commonly found in the metaphysis or diaphysis of the proximal humerus and femur in young patients. In addition, it cannot explain gnathic simple bone cysts that have demonstrated progressive enlargement over several years and, on surgical investigation, fail to reveal any evidence of continued hemorrhage. Other etiologic theories include inability of interstitial fluid to exit the bone because of inadequate venous drainage, local disturbance in bone growth, ischemic marrow necrosis, and localized alteration in bone metabolism resulting in osteolysis.

CLINICAL AND RADIOGRAPHIC FEATURES: Simple bone cysts have been reported in almost every bone of the body, but the vast majority involves the long bones. Simple bone cysts within the jaws are common and most frequently encountered in patients between 10 and 20 years of age. The lesion is rare in children younger than age 5 and is seldom seen in patients older than age 35. Simple bone cysts of the jaws are essentially restricted to the mandible, although there have been reports of the lesion in the maxilla. Bilateral simple bone cysts of the mandible are occasionally encountered. About 60% of cases occur in males.

The simple bone cyst usually produces no symptoms and is discovered only when radiographs are taken for some other reason. About 20% of patients, however, have a painless swelling of the affected area. Pain and paresthesia may be noted in a few cases. Although any area of the mandible may be involved, simple bone cysts are more common in the premolar and molar areas.

Radiographically, the lesion most frequently appears as a well-delineated radiolucent defect. In some areas, the margins of the defect are sharply defined; in other areas, the margins are ill defined. The defect may range from 1 to 10 cm in diameter. When several teeth are involved in the lesion, the radiolucent defect often shows domelike projections that scallop upward between the roots. This feature is highly suggestive but not diagnostic of a simple bone cyst (Figs. 14-25 and 14-26). In many cases, a cone-shaped outline (pointed at one or both ends in the anterior-posterior direction) may be noted, particularly when the lesion is large. Oval, irregular, or rounded borders are possible as well. Teeth that appear to be involved in the lesion are generally vital and do not show root resorption.

Fig. 14-25 Simple bone cyst. Periapical radiograph showing a radiolucent area in the apical region of the anterior mandible. The incisor teeth responded normally to vitality testing, and no restorations are present.

Fig. 14-26 Simple bone cyst. Panoramic film showing a large simple bone cyst of the mandible in a 12-year-old girl. The scalloping superior aspect of the cyst between the roots of the teeth is highly suggestive of, but not diagnostic for, a simple bone cyst. (Courtesy of Dr. Lon Doles.)

Although not characteristic, a simple bone cyst may appear as a multilocular radiolucency associated with cortical expansion and slow enlargement. When expansion is present, an occlusal radiograph typically demonstrates a thin shell of cortical bone that exhibits no further reactive changes. Extensive lesions involving a substantial portion of the body and ascending ramus are occasionally encountered (Fig. 14-27).

Fig. 14-27 Simple bone cyst. Panoramic film showing a large multilocular simple bone cyst of the mandible in a 16-year-old white adolescent. (Courtesy of Dr. Amy Bogardus.)

Similar simple cysts may be associated with lesions of cemento-osseous dysplasia and other fibro-osseous proliferations. These typically occur in older patients and are discussed later (see page 643).

HISTOPATHOLOGIC FEATURES: The walls of the defect may be lined by a thin band of vascular fibrous connective tissue or demonstrate a thickened myxofibromatous proliferation that often is intermixed with trabeculae of cellular and reactive bone. This lining may exhibit areas of vascularity, fibrin, erythrocytes, and occasional giant cells adjacent to the bone surface (Fig. 14-28). Stringy lacelike dystrophic calcifications occasionally are noted (Fig. 14-29). There is never any evidence of an epithelial lining. The bony surface next to the cavity often shows resorptive areas (Howship’s lacunae) indicative of past osteoclastic activity.

DIAGNOSIS: The radiographic features of the simple bone cyst, although often suggestive of the diagnosis, are not diagnostic and may be confused with a wide variety of odontogenic and nonodontogenic radiolucent jaw lesions. Surgical exploration is necessary to establish the diagnosis.

Because little to no tissue often is obtained at the time of surgery, the diagnosis of simple bone cyst is primarily based on the clinical and radiographic features, together with the surgical findings. In about one third of cases, the lytic defect will be found to be an empty cavity with smooth, shiny bony walls. In about two thirds of cases, the cavity will contain small amounts of serosanguineous fluid. The mandibular neurovascular bundle may be seen lying free in the cavity.

TREATMENT AND PROGNOSIS: Although the treatment of simple bone cysts of the long bones often is more aggressive and includes intralesional steroid injections or thorough surgical curettage, simple surgical exploration to establish the diagnosis is usually sufficient therapy for gnathic lesions. Even though the bony walls of the cavity at surgical exploration often appear smooth and shiny, it is wise to curette them and submit the small amount of tissue obtained for microscopic examination to rule out more serious diseases. Rarely, on microscopic examination, a lesion considered to be a simple bone cyst at surgical exploration will prove to be a thin-walled lesion, such as an odontogenic keratocyst or cystic ameloblastoma. When a thickened myxofibromatous wall is encountered, curettage and submission of this material appears prudent. After surgical exploration with or without curettage of the bony walls, obliteration of the defect by new bone formation is generally rapid. Even large defects may show normal radiographic findings within 6 months after exploration. Recurrence or persistence of the lesion is most unusual, but it has been reported. Periodic radiographic examination should be continued until complete resolution has been confirmed. The prognosis is excellent, however.

ANEURYSMAL BONE CYST

Aneurysmal bone cyst is an intraosseous accumulation of variable-sized, blood-filled spaces surrounded by cellular fibrous connective tissue that often is admixed with trabeculae of reactive woven bone. The cause and pathogenesis of the aneurysmal bone cyst are poorly understood. Several investigators have proposed that aneurysmal bone cyst arises from a traumatic event, vascular malformation, or neoplasm that disrupts the normal osseous hemodynamics and leads to an enlarging, hemorrhagic extravasation. As a corollary of this theory, others have suggested that aneurysmal bone cyst and giant cell granuloma are closely related. An aneurysmal bone cyst may form when an area of hemorrhage maintains connection with the disrupted feeding vessels; subsequently, giant cell granuloma–like areas can develop after loss of connection with the original vascular source.

Some authors have presented large series of cases involving the extragnathic skeleton and claim that none of their cases has shown evidence of a preexisting lesion. Others have reported similar large series and contend that a preexisting lesion may be evident in one third of cases. It is likely that the aneurysmal bone cyst may occur either as a primary lesion or as a result of disrupted vascular dynamics in a preexisting intrabony lesion.

Cytogenetic analysis has demonstrated the presence of various chromosomal abnormalities in some cases, particularly those involving 17p11-13 and 16q22. However, the significance of these chromosomal abnormalities in the molecular pathogenesis of the aneurysmal bone cyst remains unclear.

CLINICAL AND RADIOGRAPHIC FEATURES: Aneurysmal bone cysts are located most commonly in the shaft of a long bone or in the vertebral column in patients younger than age 30. Gnathic aneurysmal bone cysts are uncommon, with approximately 2% reported from the jaws. Within the jaws, a wide age range is noted; however, most cases arise in children and young adults, with an approximate mean age of 20 years. No significant sex predilection is noted. A mandibular predominance is noted, and the vast majority arises in the posterior segments of the jaws.

The most common clinical manifestation is a swelling that has usually developed rapidly. Pain often is reported; paresthesia, compressibility, and crepitus are rarely seen. On occasion, malocclusion, mobility, migration, or resorption of involved teeth may be present. Maxillary lesions often bulge into the adjacent sinus; nasal obstruction, nasal bleeding, proptosis, and diplopia are noted uncommonly.

Radiographic study shows a unilocular or multilocular radiolucent lesion often associated with marked cortical expansion and thinning (Fig. 14-30). The radiographic borders are variable and may be well defined or diffuse. Frequently, a ballooning or “blow-out” distention of the contour of the affected bone is described. Uncommonly, small radiopaque foci, thought to be small trabeculae of reactive bone, are noted within the radiolucency.

Fig. 14-30 Aneurysmal bone cyst. A large radiolucent lesion involves most of the ascending ramus in a 5-year-old white boy. (Courtesy of Dr. Samuel McKenna.)

At the time of surgery, intact periosteum and a thin shell of bone are typically found covering the lesion. Cortical perforation may occur, but spread into the adjacent soft tissue has not been documented. When the periosteum and bony shell are removed, dark venous blood frequently wells up and venouslike bleeding may be encountered. The appearance at surgery has been likened to that of a “blood-soaked sponge.”

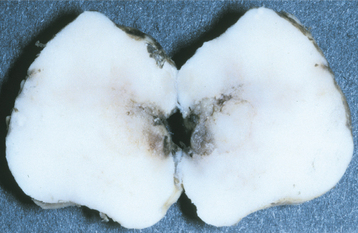

HISTOPATHOLOGIC FEATURES: Microscopically, the aneurysmal bone cyst is characterized by spaces of varying size, filled with unclotted blood surrounded by cellular fibroblastic tissue containing multinucleated giant cells and trabeculae of osteoid and woven bone. On occasion, the wall contains an unusual lacelike pattern of calcification that is uncommon in other intraosseous lesions. The blood-filled spaces are not lined by endothelium (Fig. 14-31). In approximately 20% of the cases, aneurysmal bone cyst is associated with another pathosis, most commonly a fibro-osseous lesion or giant cell granuloma.

TREATMENT AND PROGNOSIS: Aneurysmal bone cysts of the jaws are usually treated by curettage or enucleation, sometimes supplemented with cryosurgery. The vascularity of gnathic lesions is typically low flow, and removal of the bulk of the lesion is usually sufficient to control the bleeding. Rare cases require more extensive surgical resection. In most instances, the surgical defect heals within 6 months to 1 year and does not necessitate bone grafting. Irradiation is contraindicated.

The reported recurrence rates are variable and have been as low as 8% and as high as 60%. Most recurrent examples arise from inadequate or subtotal removal on initial therapy. On occasion, recurrence may be related to incomplete removal of a coexisting lesion such as an osteoblastoma or ossifying fibroma. Overall, in spite of recurrences, the long-term prognosis appears favorable.

Fibro-Osseous Lesions of the Jaws

Fibro-osseous lesions are a diverse group of processes that are characterized by replacement of normal bone by fibrous tissue containing a newly formed mineralized product. The designation fibro-osseous lesion is not a specific diagnosis and describes only a process. Fibro-osseous lesions of the jaws include developmental (hamartomatous) lesions, reactive or dysplastic processes, and neoplasms.

The pathologic features on a biopsy specimen may be very similar in lesions of diverse cause, behavior, and prognosis. Clinical, radiographic, and histopathologic correlation is usually most beneficial in establishing a specific diagnosis. Commonly included among the fibro-osseous lesions of the jaws are the following:

Although these processes have been grouped under the encompassing heading of benign fibro-osseous lesions, a more specific diagnosis often is critical because the treatment of these pathoses varies from none to surgical recontouring to complete removal. Although many examples can be diagnosed from the clinical and radiographic features, others require knowledge of the histopathologic, clinical, and radiographic features for an appropriate diagnosis.

FIBROUS DYSPLASIA

Fibrous dysplasia is a developmental tumorlike condition that is characterized by replacement of normal bone by an excessive proliferation of cellular fibrous connective tissue intermixed with irregular bony trabeculae. Although considerable confusion has existed regarding the nature of fibrous dysplasia, much has been learned about the genetics of this group of disorders, and this knowledge makes the wide variety of clinical patterns more understandable.

Fibrous dysplasia is a sporadic condition that results from a postzygotic mutation in the GNAS1 (guanine nucleotide–binding protein, α-stimulating activity polypeptide 1) gene. Clinically, fibrous dysplasia may manifest as a localized process involving only one bone, as a condition involving multiple bones, or as multiple bone lesions in conjunction with cutaneous and endocrine abnormalities. The clinical severity of the condition presumably depends on the point in time during fetal or postnatal life that the mutation of GNAS1 occurs.

If the mutation occurs in one of the undifferentiated stem cells during early embryologic life, the osteoblasts, melanocytes, and endocrine cells that represent the progeny of that mutated cell all will carry that mutation and express the mutated gene. The clinical presentation of multiple bone lesions, cutaneous pigmentation, and endocrine disturbances would result. Skeletal progenitor cells at later stages of embryonic development are assumed to migrate and differentiate as part of the process of normal skeletal formation. If the mutation occurs during this later period, then the progeny of the mutated cell will disperse and participate in the formation of the skeleton resulting in multiple bone lesions of fibrous dysplasia. Finally, if the mutation occurs during postnatal life, then the progeny of that mutated cell are essentially confined to one site, resulting in fibrous dysplasia affecting a single bone.

CLINICAL AND RADIOGRAPHIC FEATURES: