Soft Tissue Tumors

Inflammatory Papillary Hyperplasia

Peripheral Giant Cell Granuloma

Palisaded Encapsulated Neuroma

Multiple Endocrine Neoplasia Type 2B

Melanotic Neuroectodermal Tumor of Infancy

Hemangioma and Vascular Malformations

Hemangiopericytoma–Solitary Fibrous Tumor

Osseous and Cartilaginous Choristomas

Malignant Fibrous Histiocytoma

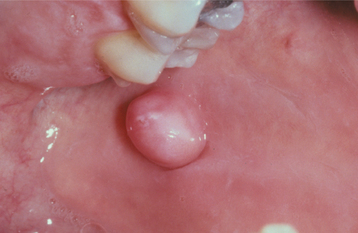

FIBROMA (IRRITATION FIBROMA; TRAUMATIC FIBROMA; FOCAL FIBROUS HYPERPLASIA; FIBROUS NODULE)

The fibroma is the most common “tumor” of the oral cavity. However, it is doubtful that it represents a true neoplasm in most instances; rather, it is a reactive hyperplasia of fibrous connective tissue in response to local irritation or trauma.

CLINICAL FEATURES: Although the irritation fibroma can occur anywhere in the mouth, the most common location is the buccal mucosa along the bite line. Presumably, this is a consequence of trauma from biting the cheek (Figs. 12-1 and 12-2). The labial mucosa, tongue, and gingiva also are common sites (Figs. 12-3 and 12-4). It is likely that many gingival fibromas represent fibrous maturation of a preexisting pyogenic granuloma. The lesion typically appears as a smooth-surfaced pink nodule that is similar in color to the surrounding mucosa. In black patients, the mass may demonstrate gray-brown pigmentation. In some cases the surface may appear white as a result of hyperkeratosis from continued irritation. Most fibromas are sessile, although some are pedunculated. They range in size from tiny lesions that are only a couple of millimeters in diameter to large masses that are several centimeters across; however, most fibromas are 1.5 cm or less in diameter. The lesion usually produces no symptoms, unless secondary traumatic ulceration of the surface has occurred. Irritation fibromas are most common in the fourth to sixth decades of life, and the male-to-female ratio is almost 1:2 for cases submitted for biopsy.

Fig. 12-2 Fibroma. Black patient with a smooth-surfaced pigmented nodule on the buccal mucosa near the commissure.

Fig. 12-4 Fibroma. Smooth-surfaced, pink nodular mass of the palatal gingiva between the cuspid and first bicuspid.

The frenal tag is a commonly observed type of fibrous hyperplasia, which most frequently occurs on the maxillary labial frenum. Such lesions present as small, asymptomatic, exophytic growths attached to the thin frenum surface (Fig. 12-5).

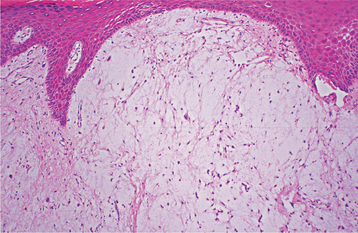

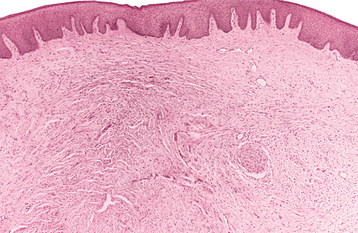

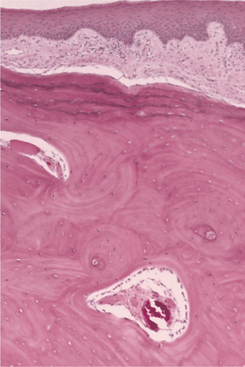

HISTOPATHOLOGIC FEATURES: Microscopic examination of the irritation fibroma shows a nodular mass of fibrous connective tissue covered by stratified squamous epithelium (Figs. 12-6 and 12-7). This connective tissue is usually dense and collagenized, although in some cases it is looser in nature. The lesion is not encapsulated; the fibrous tissue instead blends gradually into the surrounding connective tissues. The collagen bundles may be arranged in a radiating, circular, or haphazard fashion. The covering epithelium often demonstrates atrophy of the rete ridges because of the underlying fibrous mass. However, the surface may exhibit hyperkeratosis from secondary trauma. Scattered inflammation may be seen, most often beneath the epithelial surface. Usually this inflammation is chronic and consists mostly of lymphocytes and plasma cells.

TREATMENT AND PROGNOSIS: The irritation fibroma is treated by conservative surgical excision; recurrence is extremely rare. However, it is important to submit the excised tissue for microscopic examination because other benign or malignant tumors may mimic the clinical appearance of a fibroma.

Because frenal tags are small, innocuous growths that are easily diagnosed clinically, no treatment is usually necessary.

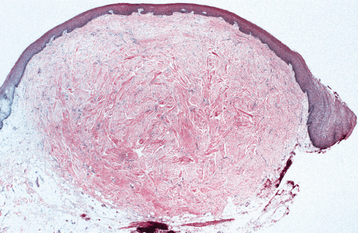

GIANT CELL FIBROMA

The giant cell fibroma is a fibrous tumor with distinctive clinicopathologic features. Unlike the traumatic fibroma, it does not appear to be associated with chronic irritation. The giant cell fibroma represents approximately 2% to 5% of all oral fibrous proliferations submitted for biopsy.

CLINICAL FEATURES: The giant cell fibroma is typically an asymptomatic sessile or pedunculated nodule, usually less than 1 cm in size (Fig. 12-8). The surface of the mass often appears papillary; therefore, the lesion may be clinically mistaken for a papilloma. Compared with the common irritation fibroma, the lesion usually occurs at a younger age. In about 60% of cases, the lesion is diagnosed during the first 3 decades of life. Some studies have suggested a slight female predilection. Approximately 50% of all cases occur on the gingiva. The mandibular gingiva is affected twice as often as the maxillary gingiva. The tongue and palate also are common sites.

The retrocuspid papilla is a microscopically similar developmental lesion that occurs on the gingiva lingual to the mandibular cuspid. It is frequently bilateral and typically appears as a small, pink papule that measures less than 5 mm in diameter (Fig. 12-9). Retrocuspid papillae are quite common, having been reported in 25% to 99% of children and young adults. The prevalence in older adults drops to 6% to 19%, suggesting that the retrocuspid papilla represents a normal anatomic variation that disappears with age.

HISTOPATHOLOGIC FEATURES: Microscopic examination of the giant cell fibroma reveals a mass of vascular fibrous connective tissue, which is usually loosely arranged (Fig. 12-10). The hallmark is the presence of numerous large, stellate fibroblasts within the superficial connective tissue. These cells may contain several nuclei. Frequently, the surface of the lesion is pebbly. The covering epithelium often is thin and atrophic, although the rete ridges may appear narrow and elongated.

EPULIS FISSURATUM (INFLAMMATORY FIBROUS HYPERPLASIA; DENTURE INJURY TUMOR; DENTURE EPULIS)

The epulis fissuratum is a tumorlike hyperplasia of fibrous connective tissue that develops in association with the flange of an ill-fitting complete or partial denture. Although the simple term epulis sometimes is used synonymously for epulis fissuratum, epulis is actually a generic term that can be applied to any tumor of the gingiva or alveolar mucosa. Therefore, some authors have advocated not using this term, preferring to call these lesions inflammatory fibrous hyperplasia or other descriptive names. However, the term epulis fissuratum is still widely used today and is well understood by virtually all clinicians. Other examples of epulides include the giant cell epulis (peripheral giant cell granuloma) (see page 520), ossifying fibroid epulis (peripheral ossifying fibroma) (see page 521), and congenital epulis (see page 537).

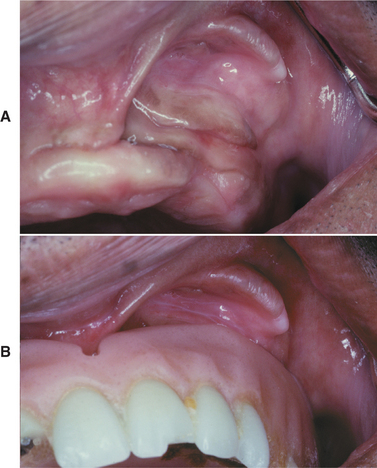

CLINICAL FEATURES: The epulis fissuratum typically appears as a single or multiple fold or folds of hyperplastic tissue in the alveolar vestibule (Figs. 12-11 and 12-12). Most often, there are two folds of tissue, and the flange of the associated denture fits conveniently into the fissure between the folds. The redundant tissue is usually firm and fibrous, although some lesions appear erythematous and ulcerated, similar to the appearance of a pyogenic granuloma. Occasional examples of epulis fissuratum demonstrate surface areas of inflammatory papillary hyperplasia (see page 512). The size of the lesion can vary from localized hyperplasias less than 1 cm in size to massive lesions that involve most of the length of the vestibule. The epulis fissuratum usually develops on the facial aspect of the alveolar ridge, although occasional lesions are seen lingual to the mandibular alveolar ridge (Fig. 12-13).

Fig. 12-12 Epulis fissuratum. A, Several folds of hyperplastic tissue in the maxillary vestibule. B, An ill-fitting denture fits into the fissure between two of the folds. (Courtesy of Dr. William Bruce.)

Fig. 12-13 Epulis fissuratum. Redundant folds of tissue arising in the floor of the mouth in association with a mandibular denture.

The epulis fissuratum most often occurs in middle-aged and older adults, as would be expected with a denture-related lesion. It may occur on either the maxilla or mandible. The anterior portion of the jaws is affected much more often than the posterior areas. There is a pronounced female predilection; most studies show that two thirds to three fourths of all cases submitted for biopsy occur in women.

Another similar but less common fibrous hyperplasia, often called a fibroepithelial polyp or leaflike denture fibroma, occurs on the hard palate beneath a maxillary denture. This characteristic lesion is a flattened pink mass that is attached to the palate by a narrow stalk (Fig. 12-14). Usually, the flattened mass is closely applied to the palate and sits in a slightly cupped-out depression. However, it is easily lifted up with a probe, which demonstrates its pedunculated nature. The edge of the lesion often is serrated and resembles a leaf.

Fig. 12-14 Fibroepithelial polyp. Flattened mass of tissue arising on the hard palate beneath a maxillary denture; note its pedunculated nature. Because of its serrated edge, this lesion also is known as a leaflike denture fibroma. Associated inflammatory papillary hyperplasia is visible in the palatal midline.

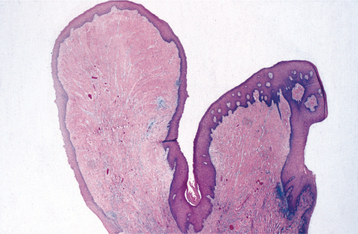

HISTOPATHOLOGIC FEATURES: Microscopic examination of the epulis fissuratum reveals hyperplasia of the fibrous connective tissue. Often multiple folds and grooves occur where the denture impinges on the tissue (Fig. 12-15). The overlying epithelium is frequently hyperparakeratotic and demonstrates irregular hyperplasia of the rete ridges. In some instances, the epithelium shows inflammatory papillary hyperplasia (see page 513) or pseudoepitheliomatous (pseudocarcinomatous) hyperplasia. Focal areas of ulceration are not unusual, especially at the base of the grooves between the folds. A variable chronic inflammatory infiltrate is present; sometimes, it may include eosinophils or show lymphoid follicles. If minor salivary glands are included in the specimen, then they usually show chronic sialadenitis.

Fig. 12-15 Epulis fissuratum. Low-power photomicrograph demonstrating folds of hyperplastic fibrovascular connective tissue covered by stratified squamous epithelium.

In rare instances, the formation of osteoid or chondroid is observed. This unusual-appearing product, known as osseous and chondromatous metaplasia, is a reactive phenomenon caused by chronic irritation by the ill-fitting denture (see page 318). The irregular nature of this bone or cartilage can be microscopically disturbing, and the pathologist should not mistake it for a sarcoma.

The denture-related fibroepithelial polyp has a narrow core of dense fibrous connective tissue covered by stratified squamous epithelium. Like the epulis fissuratum, the overlying epithelium may be hyperplastic.

INFLAMMATORY PAPILLARY HYPERPLASIA (DENTURE PAPILLOMATOSIS)

Inflammatory papillary hyperplasia is a reactive tissue growth that usually, although not always, develops beneath a denture. Some investigators classify this lesion as part of the spectrum of denture stomatitis (see page 216). Although the exact pathogenesis is unknown, the condition most often appears to be related to the following:

Approximately 20% of patients who wear their dentures 24 hours a day have inflammatory papillary hyperplasia. Candida organisms also have been suggested as a cause, but any possible role appears uncertain.

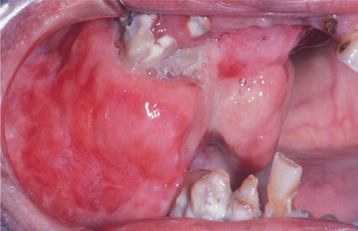

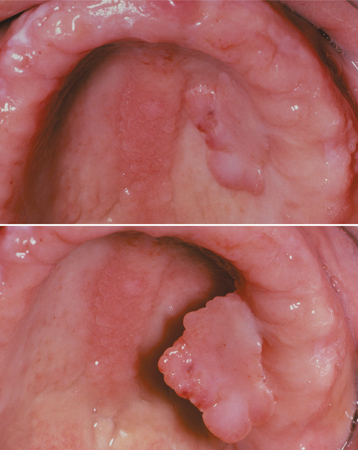

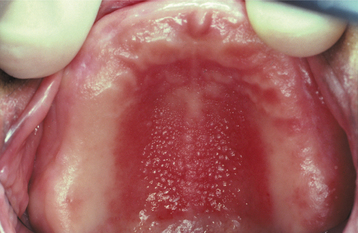

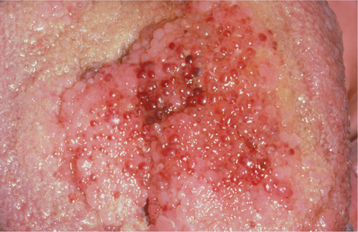

CLINICAL FEATURES: Inflammatory papillary hyperplasia usually occurs on the hard palate beneath a denture base (Figs. 12-16 and 12-17). Early lesions may involve only the palatal vault, although advanced cases cover most of the palate. Less frequently, this hyperplasia develops on the edentulous mandibular alveolar ridge or on the surface of an epulis fissuratum. On rare occasions, the condition occurs on the palate of a patient without a denture, especially in people who habitually breathe through their mouth or have a high palatal vault. Candida-associated palatal papillary hyperplasia also has been reported in dentate patients with human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection.

Fig. 12-16 Inflammatory papillary hyperplasia. Erythematous, pebbly appearance of the palatal vault.

Fig. 12-17 Inflammatory papillary hyperplasia. An advanced case exhibiting more pronounced papular lesions of the hard palate.

Inflammatory papillary hyperplasia is usually asymptomatic. The mucosa is erythematous and has a pebbly or papillary surface. Many cases are associated with denture stomatitis.

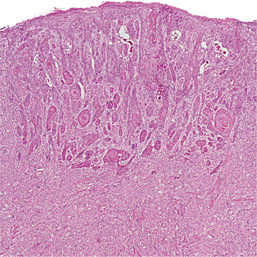

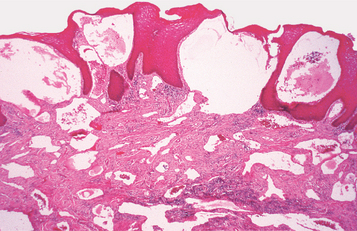

HISTOPATHOLOGIC FEATURES: The mucosa in inflammatory papillary hyperplasia exhibits numerous papillary growths on the surface that are covered by hyperplastic, stratified squamous epithelium (Fig. 12-18). In advanced cases, this hyperplasia is pseudoepitheliomatous in appearance, and the pathologist should not mistake it for carcinoma (Fig. 12-19). The connective tissue can vary from loose and edematous to densely collagenized. A chronic inflammatory cell infiltrate is usually seen, which consists of lymphocytes and plasma cells. Less frequently, polymorphonuclear leukocytes are also present. If underlying salivary glands are present, then they often show sclerosing sialadenitis.

TREATMENT AND PROGNOSIS: For very early lesions of inflammatory papillary hyperplasia, removal of the denture may allow the erythema and edema to subside, and the tissues may resume a more normal appearance. The condition also may show improvement after topical or systemic antifungal therapy. For more advanced and collagenized lesions, many clinicians prefer to excise the hyperplastic tissue before fabricating a new denture. Various surgical methods have been used, including the following:

After surgery, the existing denture can be lined with a temporary tissue conditioner that acts as a palatal dressing and promotes greater comfort. After healing, the patient should be encouraged to leave the new denture out at night and to keep it clean.

FIBROUS HISTIOCYTOMA

Fibrous histiocytomas are a diverse group of tumors that exhibit fibroblastic and histiocytic differentia-tion. Although the cell of origin is still uncertain, it may arise from the tissue histiocyte, which then assumes fibroblastic properties. Because of the variable nature of these lesions, an array of terms has been used for them, including dermatofibroma, sclerosing hemangioma, fibroxanthoma, and nodular subepidermal fibrosis. Unlike other fibrous growths discussed previously in this chapter, the fibrous histiocytoma is generally considered to represent a true neoplasm.

CLINICAL FEATURES: The fibrous histiocytoma can develop almost anywhere in the body. The most common site is the skin of the extremities, where the lesion is called a dermatofibroma. Tumors of the oral and perioral region are uncommon. Although oral tumors can occur at any site, the most frequent location is the buccal mucosa and vestibule. Rare intrabony lesions of the jaws have also been reported. Oral fibrous histiocytomas tend to occur in middle-aged and older adults; cutaneous examples are most frequent in young adults. The tumor is usually a painless nodular mass and can vary in size from a few millimeters to several centimeters in diameter (Fig. 12-20). Deeper tumors tend to be larger.

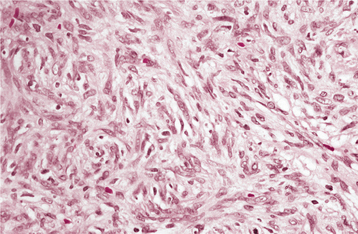

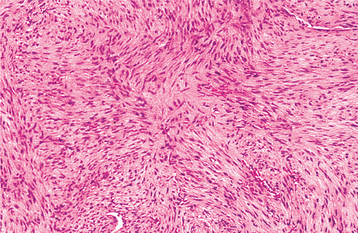

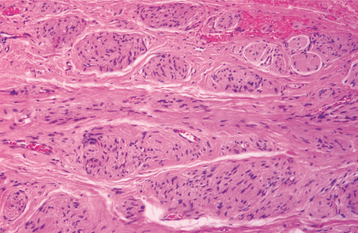

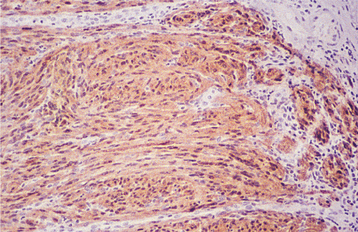

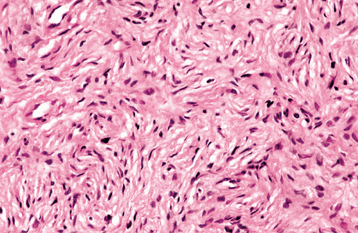

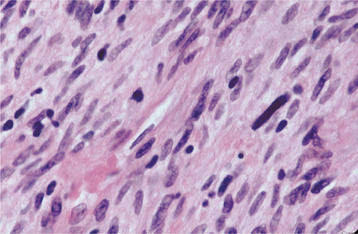

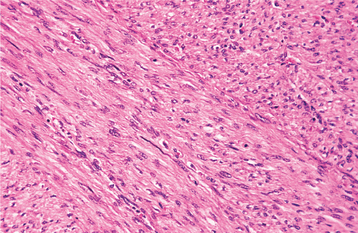

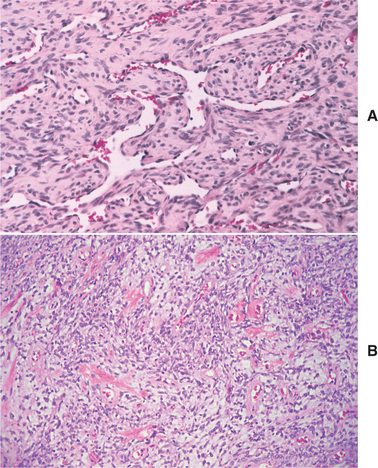

HISTOPATHOLOGIC FEATURES: Microscopically, the fibrous histiocytoma is characterized by a cellular proliferation of spindle-shaped fibroblastic cells with vesicular nuclei (Figs. 12-21 and 12-22). The margins of the tumor often are not sharply defined. The tumor cells are arranged in short, intersecting fascicles, known as a storiform pattern because of its resemblance to the irregular, whorled appearance of a straw mat. Rounded histiocyte-like cells, lipid-containing xanthoma cells, or multinucleated giant cells can be seen occasionally, as may scattered lymphocytes. The stroma may demonstrate areas of myxoid change or focal hyalinization.

FIBROMATOSIS

The fibromatoses are a broad group of fibrous proliferations that have a biologic behavior and histopathologic pattern that is intermediate between those of benign fibrous lesions and fibrosarcoma. A number of different forms of fibromatosis are recognized throughout the body, and they often are named based on their particular clinicopathologic features. In the soft tissues of the head and neck, these lesions are frequently called juvenile aggressive fibromatoses or extraabdominal desmoids. Similar lesions within the bone have been called desmoplastic fibromas (see page 658). Individuals with familial adenomatous polyposis and Gardner syndrome (see page 651) have a greatly increased risk for developing aggressive fibromatosis.

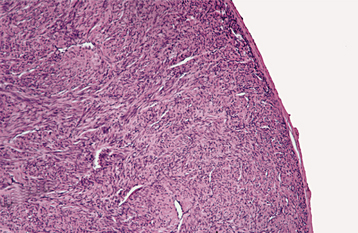

CLINICAL AND RADIOGRAPHIC FEATURES: Soft tissue fibromatosis of the head and neck is a firm, painless mass, which may exhibit rapid or insidious growth (Fig. 12-23). The lesion most frequently occurs in children or young adults; hence, the term juvenile fibromatosis. However, cases also have been seen in middle-aged adults. The most common oral site is the paramandibular soft tissue region, although the lesion can occur almost anywhere. The tumor can grow to considerable size, resulting in significant facial disfigurement. Destruction of adjacent bone may be observed on radiographs and other imaging studies.

HISTOPATHOLOGIC FEATURES: Soft tissue fibromatosis is characterized by a cellular proliferation of spindle-shaped cells that are arranged in streaming fascicles and are associated with a variable amount of collagen (Fig. 12-24). The lesion is usually poorly circumscribed and infiltrates the adjacent tissues. Hyperchromatism and pleomorphism of the cells should not be observed.

TREATMENT AND PROGNOSIS: Because of its locally aggressive nature, the preferred treatment for soft tissue fibromatosis is wide excision that includes a generous margin of adjacent normal tissues. Adjuvant chemotherapy or radiation therapy sometimes has been used for incompletely resected or recurrent tumors. A 23% recurrence rate has been reported for oral and paraoral fibromatosis, but a higher recurrence rate has been noted for other head and neck sites. Metastasis does not occur.

MYOFIBROMA (MYOFIBROMATOSIS)

Myofibroma is a rare spindle cell neoplasm that consists of myofibroblasts (i.e., cells with both smooth muscle and fibroblastic features). Such cells are not specific for this lesion, however, because they also can be identified in other fibrous proliferations. Most myofibromas occur as solitary lesions, but some patients develop a multicentric tumor process known as myofibromatosis.

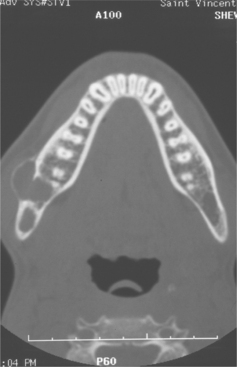

CLINICAL AND RADIOGRAPHIC FEATURES: Although myofibromas are rare neoplasms, they demonstrate a predilection for the head and neck region. Solitary tumors develop most frequently in the first 4 decades of life, with a mean age of 22 years. The most common oral location is the mandible, followed by the tongue and buccal mucosa. The tumor is typically a painless mass that sometimes exhibits rapid enlargement. Intrabony tumors create radiolucent defects that usually tend to be poorly defined, although some may be well defined or multilocular (Fig. 12-25). Multicentric myofibromatosis primarily affects neonates and infants who may have tumors of the skin, subcutaneous tissue, muscle, bone, and viscera. The number of tumors can vary from several to more than 100.

HISTOPATHOLOGIC FEATURES: Myofibromas are composed of interlacing bundles of spindle cells with tapered or blunt-ended nuclei and eosinophilic cytoplasm (Fig. 12-26). Nodular fascicles may alternate with more cellular zones, imparting a biphasic appearance to the tumor. Scattered mitoses are not uncommon. Centrally, the lesion is often more vascular with a hemangiopericytoma-like appearance. The tumor cells are positive for smooth muscle actin and muscle-specific actin with immunohistochemistry, but they are negative for desmin.

TREATMENT AND PROGNOSIS: Solitary myofibromas are usually treated by surgical excision. A small percentage of tumors will recur after treatment, but typically, these can be controlled with reexcision. Multifocal tumors arising in soft tissues and bone rarely recur after surgical excision. Spontaneous regression may occur in some cases. However, myofibromatosis involving the viscera or vital organs in infants can act more aggressively and sometimes proves to be fatal within a few days after birth.

ORAL FOCAL MUCINOSIS

Oral focal mucinosis is an uncommon tumorlike mass that is believed to represent the oral counterpart of cutaneous focal mucinosis or a cutaneous myxoid cyst. The cause is unknown, although the lesion may result from overproduction of hyaluronic acid by fibroblasts.

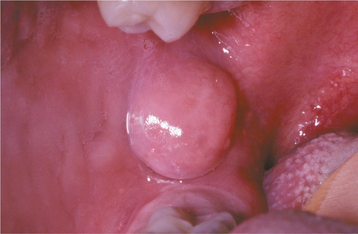

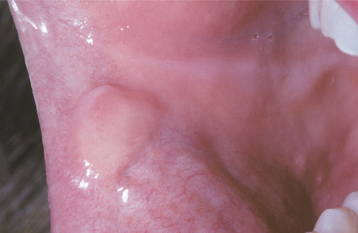

CLINICAL FEATURES: Oral focal mucinosis is most common in young adults and shows a 2:1 female-to-male predilection. The gingiva is the most common site; two thirds to three fourths of all cases are found there. The hard palate is the second most common location. The mass rarely appears at other oral sites. The lesion usually presents as a sessile or pedunculated, painless nodular mass that is the same color as the surrounding mucosa (Fig. 12-27). The surface is typically smooth and nonulcerated, although occasional cases exhibit a lobulated appearance. The size varies from a few millimeters up to 2 cm in diameter. The patient often has been aware of the mass for many months or years before the diagnosis is made.

HISTOPATHOLOGIC FEATURES: Microscopic examination of oral focal mucinosis shows a well-localized but nonencapsulated area of loose, myxomatous connective tissue surrounded by denser, normal collagenous connective tissue (Figs. 12-28 and 12-29). The lesion is usually found just beneath the surface epithelium and often causes flattening of the rete ridges. The fibroblasts within the mucinous area can be ovoid, fusiform, or stellate, and they may demonstrate delicate, fibrillar processes. Few capillaries are seen within the lesion, especially compared with the surrounding denser collagen. Similarly, no significant inflammation is observed, although a perivascular lymphocytic infiltrate often is noted within the surrounding collagenous connective tissue. No appreciable reticulin is evident within the lesion, and special stains suggest that the mucinous product is hyaluronic acid.

PYOGENIC GRANULOMA

The pyogenic granuloma is a common tumorlike growth of the oral cavity that traditionally has been considered to be nonneoplastic in nature.* Although it was originally thought to be caused by pyogenic organisms, it is now believed to be unrelated to infection. Instead, the pyogenic granuloma is thought to represent an exuberant tissue response to local irritation or trauma. In spite of its name, it is not a true granuloma.

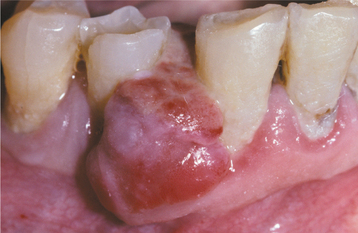

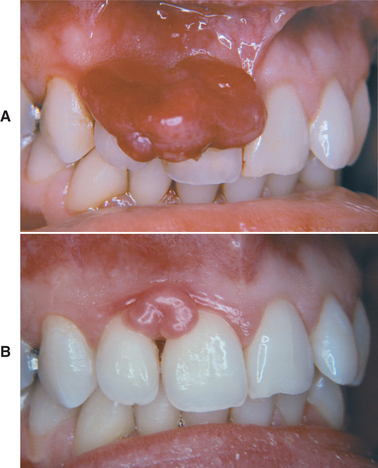

CLINICAL FEATURES: The pyogenic granuloma is a smooth or lobulated mass that is usually pedunculated, although some lesions are sessile (Figs. 12-30 to 12-32). The surface is characteristically ulcerated and ranges from pink to red to purple, depending on the age of the lesion. Young pyogenic granulomas are highly vascular in appearance; older lesions tend to become more collagenized and pink. They vary from small growths only a few millimeters in size to larger lesions that may measure several centimeters in diameter. Typically, the mass is painless, although it often bleeds easily because of its extreme vascularity. Pyogenic granulomas may exhibit rapid growth, which may create alarm for both the patient and the clinician, who may fear that the lesion might be malignant.

Fig. 12-30 Pyogenic granuloma. Erythematous, hemorrhagic mass arising from the maxillary anterior gingiva.

Fig. 12-32 Pyogenic granuloma. Unusually large lesion arising from the palatal gingiva in association with an orthodontic band. The patient was pregnant.

Oral pyogenic granulomas show a striking predilection for the gingiva, which accounts for 75% of all cases. Gingival irritation and inflammation that result from poor oral hygiene may be a precipitating factor in many patients. The lips, tongue, and buccal mucosa are the next most common sites. A history of trauma before the development of the lesion is not unusual, especially for extragingival pyogenic granulomas. Lesions are slightly more common on the maxillary gingiva than the mandibular gingiva; anterior areas are more frequently affected than posterior areas. These lesions are much more common on the facial aspect of the gingiva than the lingual aspect; some extend between the teeth and involve both the facial and the lingual gingiva.

Although the pyogenic granuloma can develop at any age, it is most common in children and young adults. Most studies also demonstrate a definite female predilection, possibly because of the vascular effects of female hormones. Pyogenic granulomas of the gingiva frequently develop in pregnant women, so much so that the terms pregnancy tumor or granuloma gravidarum often are used. Such lesions may begin to develop during the first trimester, and their incidence increases up through the seventh month of pregnancy. The gradual rise in development of these lesions throughout pregnancy may be related to the increasing levels of estrogen and progesterone as the pregnancy progresses. After pregnancy and the return of normal hormone levels, some of these pyogenic granulomas resolve without treatment or undergo fibrous maturation and resemble a fibroma (Fig. 12-33).

Fig. 12-33 Pyogenic granuloma. A, Large gingival mass in a pregnant woman just before childbirth. B, The mass has decreased in size and undergone fibrous maturation 3 months after childbirth. (Courtesy of Dr. George Blozis.)

Epulis granulomatosa is a term used to describe hyperplastic growths of granulation tissue that sometimes arise in healing extraction sockets (Fig. 12-34). These lesions resemble pyogenic granulomas and usually represent a granulation tissue reaction to bony sequestra in the socket.

HISTOPATHOLOGIC FEATURES: Microscopic examination of pyogenic granulomas shows a highly vascular proliferation that resembles granulation tissue (Figs. 12-35 and 12-36). Numerous small and larger endothelium-lined channels are formed that are engorged with red blood cells. These vessels sometimes are organized in lobular aggregates, and some pathologists require this lobular arrangement for the diagnosis (lobular capillary hemangioma). The surface is usually ulcerated and replaced by a thick fibrinopurulent membrane. A mixed inflammatory cell infiltrate of neutrophils, plasma cells, and lymphocytes is evident. Neutrophils are most prevalent near the ulcerated surface; chronic inflammatory cells are found deeper in the specimen. Older lesions may have areas with a more fibrous appearance. In fact, many gingival fibromas probably represent pyogenic granulomas that have undergone fibrous maturation.

TREATMENT AND PROGNOSIS: The treatment of patients with pyogenic granuloma consists of conservative surgical excision, which is usually curative. The specimen should be submitted for microscopic examination to rule out other more serious diagnoses. For gingival lesions, the excision should extend down to periosteum and the adjacent teeth should be thoroughly scaled to remove any source of continuing irritation. Occasionally, the lesion recurs and reexcision is necessary. In rare instances, multiple recurrences have been noted.

For lesions that develop during pregnancy, usually treatment should be deferred unless significant functional or aesthetic problems develop. The recurrence rate is higher for pyogenic granulomas removed during pregnancy, and some lesions will resolve spontaneously after parturition.

PERIPHERAL GIANT CELL GRANULOMA (GIANT CELL EPULIS)

The peripheral giant cell granuloma is a relatively common tumorlike growth of the oral cavity. It probably does not represent a true neoplasm but rather is a reactive lesion caused by local irritation or trauma. In the past, it often was called a peripheral giant cell reparative granuloma, but any reparative nature appears doubtful. Some investigators believe that the giant cells show immunohistochemical features of osteoclasts, whereas other authors have suggested that the lesion is formed by cells from the mononuclear phagocyte system. The peripheral giant cell granuloma bears a close microscopic resemblance to the central giant cell granuloma (see page 626), and some pathologists believe that it may represent a soft tissue counterpart of this central bony lesion.

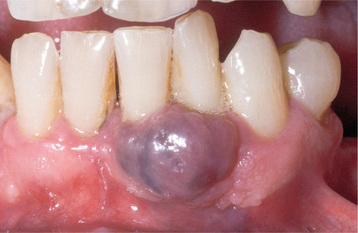

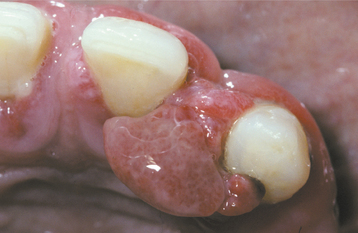

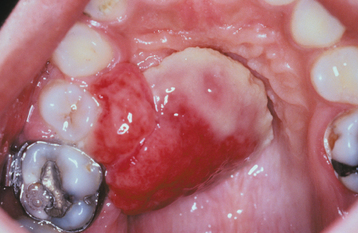

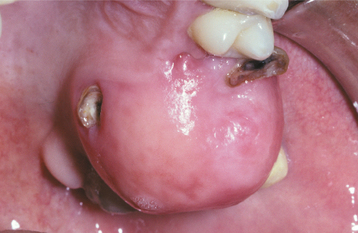

CLINICAL AND RADIOGRAPHIC FEATURES: The peripheral giant cell granuloma occurs exclusively on the gingiva or edentulous alveolar ridge, presenting as a red or red-blue nodular mass (Figs. 12-37 and 12-38). Most lesions are smaller than 2 cm in diameter, although larger ones are seen occasionally. The lesion can be sessile or pedunculated and may or may not be ulcerated. The clinical appearance is similar to the more common pyogenic granuloma of the gingiva (see page 517), although the peripheral giant cell granuloma often is more blue-purple compared with the bright red of a typical pyogenic granuloma.

Peripheral giant cell granulomas can develop at almost any age, especially during the first through sixth decades of life. The mean age in several large series ranges from 31 to 41 years. Approximately 60% of cases occur in females. It may develop in either the anterior or posterior regions of the gingiva or alveolar mucosa, and the mandible is affected slightly more often than the maxilla. Although the peripheral giant cell granuloma develops within soft tissue, “cupping” resorption of the underlying alveolar bone sometimes is seen. On occasion, it may be difficult to determine whether the mass arose as a peripheral lesion or as a central giant cell granuloma that eroded through the cortical plate into the gingival soft tissues.

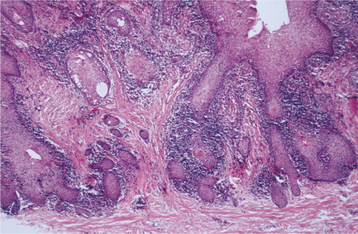

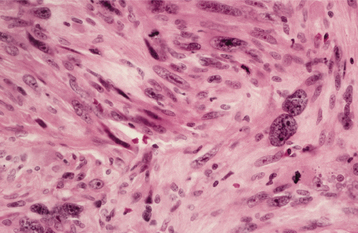

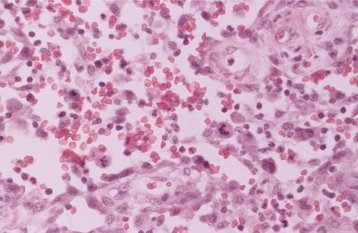

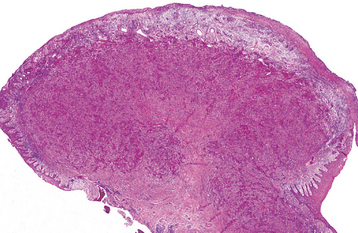

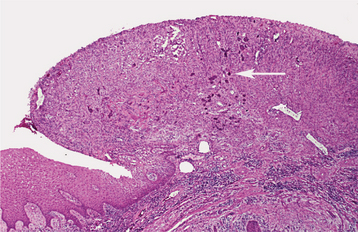

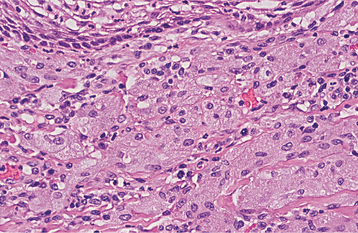

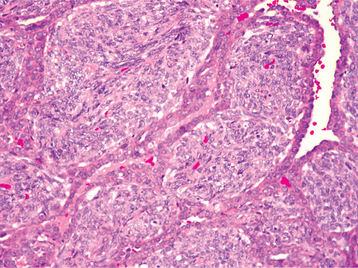

HISTOPATHOLOGIC FEATURES: Microscopic examination of a peripheral giant cell granuloma shows a proliferation of multinucleated giant cells within a background of plump ovoid and spindle-shaped mesenchymal cells (Figs. 12-39 and 12-40). The giant cells may contain only a few nuclei or up to several dozen. Some of these cells may have large, vesicular nuclei; others demonstrate small, pyknotic nuclei. Mitotic figures are fairly common in the background mesenchymal cells. Abundant hemorrhage is characteristically found throughout the mass, which often results in deposits of hemosiderin pigment, especially at the periphery of the lesion.

Fig. 12-39 Peripheral giant cell granuloma. Low-power view showing a nodular proliferation of multinucleated giant cells within the gingiva.

Fig. 12-40 Peripheral giant cell granuloma. High-power view showing scattered multinucleated giant cells within a hemorrhagic background of ovoid and spindle-shaped mesenchymal cells.

The overlying mucosal surface is ulcerated in about 50% of cases. A zone of dense fibrous connective tissue usually separates the giant cell proliferation from the mucosal surface. Adjacent acute and chronic inflammatory cells are frequently present. Areas of reactive bone formation or dystrophic calcifications are not unusual.

TREATMENT AND PROGNOSIS: The treatment of the peripheral giant cell granuloma consists of local surgical excision down to the underlying bone. The adjacent teeth should be carefully scaled to remove any source of irritation and to minimize the risk of recurrence. Approximately 10% of lesions are reported to recur, and reexcision must be performed. On rare occasions, lesions indistinguishable from peripheral giant cell granulomas have been seen in patients with hyperparathyroidism (see page 838). They apparently represent the so-called osteoclastic brown tumors associated with this endocrine disorder. However, the brown tumors of hyperparathyroidism are much more likely to be intraosseous in location and mimic a central giant cell granuloma.

PERIPHERAL OSSIFYING FIBROMA (OSSIFYING FIBROID EPULIS; PERIPHERAL FIBROMA WITH CALCIFICATION; CALCIFYING FIBROBLASTIC GRANULOMA)

The peripheral ossifying fibroma is a relatively common gingival growth that is considered to be reactive rather than neoplastic in nature. The pathogenesis of this lesion is uncertain. Because of their clinical and histopathologic similarities, researchers believe that some peripheral ossifying fibromas develop initially as pyogenic granulomas that undergo fibrous maturation and subsequent calcification. However, not all peripheral ossifying fibromas may develop in this manner. The mineralized product probably has its origin from cells of the periosteum or periodontal ligament.

Considerable confusion has existed over the nomenclature of this lesion, and several terms have been used to describe its variable histopathologic features. In the past, the terms peripheral odontogenic fibroma (see page 727) and peripheral ossifying fibroma often were used synonymously, but the peripheral odontogenic fibroma is now considered to be a distinct and separate entity. In addition, in spite of the similarity in names, the peripheral ossifying fibroma does not represent the soft tissue counterpart of the central ossifying fibroma (see page 646).

CLINICAL FEATURES: The peripheral ossifying fibroma occurs exclusively on the gingiva. It appears as a nodular mass, either pedunculated or sessile, that usually emanates from the interdental papilla (Figs. 12-41 and 12-42). The color ranges from red to pink, and the surface is frequently, but not always, ulcerated. The growth probably begins as an ulcerated lesion; older ones are more likely to demonstrate healing of the ulcer and an intact surface. Red, ulcerated lesions often are mistaken for pyogenic granulomas; the pink, nonulcerated ones are clinically similar to irritation fibromas. Most lesions are less than 2 cm in size, although larger ones occasionally occur. The lesion often has been present for many weeks or months before the diagnosis is made.

Fig. 12-41 Peripheral ossifying fibroma. Red, ulcerated mass of the maxillary gingiva. Such ulcerated lesions are easily mistaken for a pyogenic granuloma.

Fig. 12-42 Peripheral ossifying fibroma. Pink, nonulcerated mass arising from the maxillary gingiva. The remaining roots of the first molar are present.

The peripheral ossifying fibroma is predominantly a lesion of teenagers and young adults, with peak prevalence between the ages of 10 and 19. Almost two thirds of all cases occur in females. There is a slight predilection for the maxillary arch, and more than 50% of all cases occur in the incisor-cuspid region. Usually, the teeth are unaffected; rarely, there can be migration and loosening of adjacent teeth.

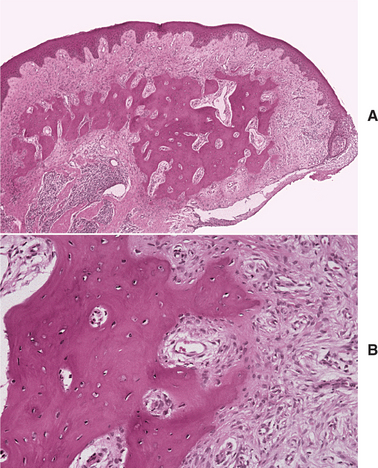

HISTOPATHOLOGIC FEATURES: The basic microscopic pattern of the peripheral ossifying fibroma is one of a fibrous proliferation associated with the formation of a mineralized product (Figs. 12-43 and 12-44). If the epithelium is ulcerated, then the surface is covered by a fibrinopurulent membrane with a subjacent zone of granulation tissue. The deeper fibroblastic component often is cellular, especially in areas of mineralization. In some cases, the fibroblastic proliferation and associated mineralization is only a small component of a larger mass that resembles a fibroma or pyogenic granuloma.

Fig. 12-43 Peripheral ossifying fibroma. Ulcerated gingival mass demonstrating focal early mineralization (arrow).

Fig. 12-44 Peripheral ossifying fibroma. A, Nonulcerated fibrous mass of the gingiva showing central bone formation. B, Higher-power view showing trabeculae of bone with adjacent fibrous connective tissue.

The type of mineralized component is variable and may consist of bone, cementum-like material, or dystrophic calcifications. Frequently, a combination of products is formed. Usually, the bone is woven and trabecular in type, although older lesions may demonstrate mature lamellar bone. Trabeculae of unmineralized osteoid are not unusual. Less frequently, ovoid droplets of basophilic cementum-like material are formed. Dystrophic calcifications are characterized by multiple granules, tiny globules, or large, irregular masses of basophilic mineralized material. Such dystrophic calcifications are more common in early, ulcerated lesions; older, nonulcerated examples are more likely to demonstrate well-formed bone or cementum. In some cases, multinucleated giant cells may be found, usually in association with the mineralized product.

TREATMENT AND PROGNOSIS: The treatment of choice for the peripheral ossifying fibroma is local surgical excision with submission of the specimen for histopathologic examination. The mass should be excised down to periosteum because recurrence is more likely if the base of the lesion is allowed to remain. In addition, the adjacent teeth should be thoroughly scaled to eliminate any possible irritants. Periodontal surgical techniques, such as repositioned flaps or connective tissue grafts, may be necessary to repair the gingival defect in an aesthetic manner. Although excision is usually curative, a recurrence rate of 8% to 16% has been reported.

LIPOMA

The lipoma is a benign tumor of fat. Although it represents by far the most common mesenchymal neoplasm, most examples occur on the trunk and proximal portions of the extremities. Lipomas of the oral and maxillofacial region are much less frequent. The pathogenesis of lipomas is uncertain, but they appear to be more common in obese people. However, the metabolism of lipomas is completely independent of the normal body fat. If the caloric intake is reduced, then lipomas do not decrease in size, although normal body fat may be lost.

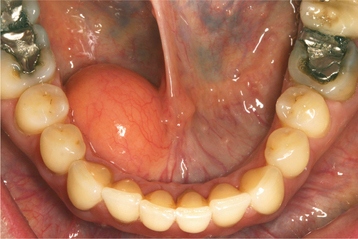

CLINICAL FEATURES: Oral lipomas are usually soft, smooth-surfaced nodular masses that can be sessile or pedunculated (Figs. 12-45 and 12-46). Typically, the tumor is asymptomatic and often has been noted for many months or years before diagnosis. Most are less than 3 cm in size, but occasional lesions can become much larger. Although a subtle or more obvious yellow hue often is detected clinically, deeper examples may appear pink. The buccal mucosa and buccal vestibule are the most common intraoral sites and account for 50% of all cases. Some buccal cases may not represent true tumors, but rather herniation of the buccal fat pad through the buccinator muscle, which may occur after local trauma in young children or subsequent to surgical removal of third molars in older patients. Less common sites include the tongue, floor of the mouth, and lips. Most patients are 40 years of age or older; lipomas are uncommon in children. Lipomas of the oral and maxillofacial region have shown a fairly balanced sex distribution in some studies, although one recent large series demonstrated a marked male predilection.

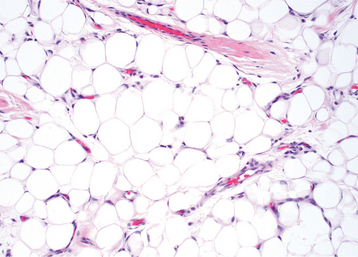

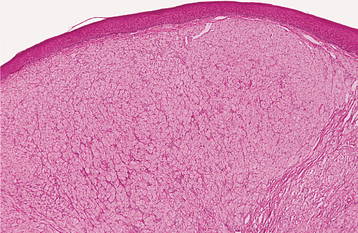

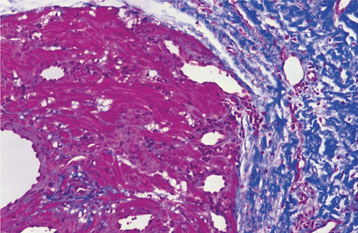

HISTOPATHOLOGIC FEATURES: Most oral lipomas are composed of mature fat cells that differ little in microscopic appearance from the surrounding normal fat (Figs. 12-47 and 12-48). The tumor is usually well circumscribed and may demonstrate a thin fibrous capsule. A distinct lobular arrangement of the cells often is seen. On rare occasions, central cartilaginous or osseous metaplasia may occur within an otherwise typical lipoma.

Fig. 12-47 Lipoma. Low-power view of a tumor of the tongue demonstrating a mass of mature adipose tissue.

A number of microscopic variants have been described. The most common of these is the fibrolipoma, which is characterized by a significant fibrous component intermixed with the lobules of fat cells. The remaining variants are rare.

The angiolipoma consists of an admixture of mature fat and numerous small blood vessels. The spindle cell lipoma demonstrates variable amounts of uni-form-appearing spindle cells in conjunction with a more typical lipomatous component. Some spindle cell lipomas exhibit a mucoid background (myxoid lipoma) and may be confused with myxoid liposarcomas. Pleomorphic lipomas are characterized by the presence of spindle cells plus bizarre, hyperchromatic giant cells; they can be difficult to distinguish from a pleomorphic liposarcoma. Intramuscular (infiltrating) lipomas often are more deeply situated and have an infiltrative growth pattern that extends between skeletal muscle bundles.

TREATMENT AND PROGNOSIS: Lipomas are treated by conservative local excision, and recurrence is rare. Most microscopic variants do not affect the prognosis. Intramuscular lipomas have a higher recurrence rate because of their infiltrative growth pattern, but this variant is rare in the oral and maxillofacial region.

TRAUMATIC NEUROMA (AMPUTATION NEUROMA)

The traumatic neuroma is not a true neoplasm but a reactive proliferation of neural tissue after transection or other damage of a nerve bundle. After a nerve has been damaged or severed, the proximal portion attempts to regenerate and reestablish innervation of the distal segment by the growth of axons through tubes of proliferating Schwann cells. If these regenerating elements encounter scar tissue or otherwise cannot reestablish innervation, then a tumorlike mass may develop at the site of injury.

CLINICAL AND RADIOGRAPHIC FEATURES: Traumatic neuromas of the oral mucosa are typically smooth-surfaced, nonulcerated nodules. They can develop at any location but are most common in the mental foramen area, tongue, and lower lip (Figs. 12-49 and 12-50). A history of trauma often can be elicited; some lesions arise subsequent to tooth extraction or other surgical procedures. Intraosseous traumatic neuromas may demonstrate a radiolucent defect on oral radiographs. Examples also may occur at other head and neck sites; it has been estimated that traumatic neuromas of the greater auricular nerve develop in 5% to 10% of patients undergoing surgery for pleomorphic adenomas of the parotid gland.

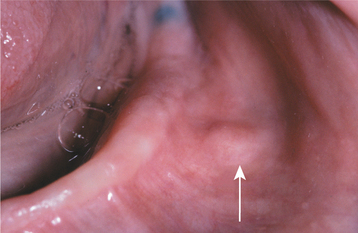

Fig. 12-49 Traumatic neuroma. Painful nodule of the mental nerve as it exits the mental foramen (arrow).

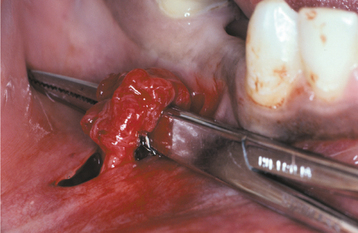

Fig. 12-50 Traumatic neuroma. Note the irregular nodular proliferation along the mental nerve that is being exposed at the time of surgery.

Traumatic neuromas can occur at any age, but they are diagnosed most often in middle-aged adults. They appear to be slightly more common in women. Many traumatic neuromas are associated with altered nerve sensations that can range from anesthesia to dysesthesia to overt pain. Although pain has been traditionally considered a hallmark of this lesion, studies indicate that only one fourth to one third of oral traumatic neuromas are painful. This pain can be intermittent or constant and ranges from mild tenderness or burning to severe radiating pain. Neuromas of the mental nerve are frequently painful, especially when impinged on by a denture or palpated.

HISTOPATHOLOGIC FEATURES: Microscopic examination of traumatic neuromas shows a haphazard proliferation of mature, myelinated and unmyelinated nerve bundles within a fibrous connective tissue stroma that ranges from densely collagenized to myxomatous in nature (Figs. 12-51 and 12-52). An associated mild chronic inflammatory cell infiltrate may be present. Traumatic neuromas with inflammation are more likely to be painful than those without significant inflammation.

PALISADED ENCAPSULATED NEUROMA (SOLITARY CIRCUMSCRIBED NEUROMA)

The palisaded encapsulated neuroma is a benign neural tumor with distinctive clinical and histopathologic features. Although it was first recognized only as recently as 1972, it represents one of the more common superficial nerve tumors, especially in the head and neck region. The cause is uncertain, but some authors have speculated that trauma may play an etiologic role; the tumor is generally considered to represent a reactive lesion rather than a true neoplasm.

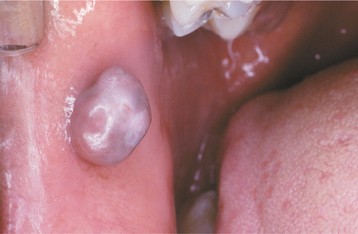

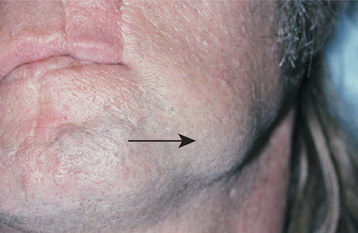

CLINICAL FEATURES: The palisaded encapsulated neuroma shows a striking predilection for the face, which accounts for approximately 90% of reported cases. The nose and cheek are the most common specific sites. The lesion is most frequently diagnosed between the fifth and seventh decades of life, although the tumor often has been present for many months or years. It is a smooth-surfaced, painless, dome-shaped papule or nodule that is usually less than 1 cm in diameter. There is no sex predilection.

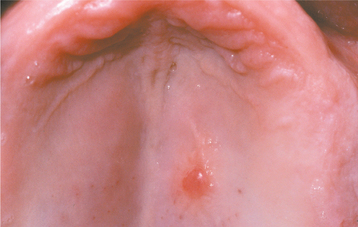

Oral palisaded encapsulated neuromas are not uncommon, although many are probably diagnosed microscopically as neurofibromas or neurilemomas. The lesion appears most frequently on the hard palate (Fig. 12-53) and maxillary labial mucosa, although it also may occur in other oral locations.

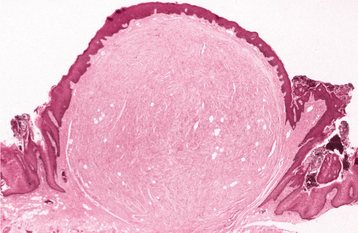

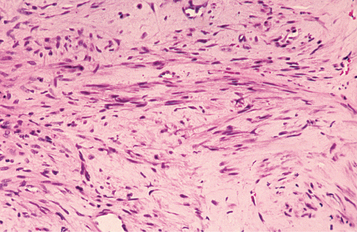

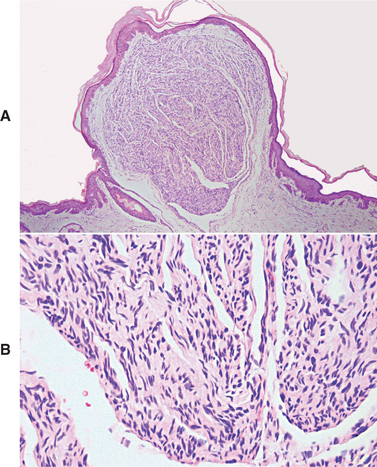

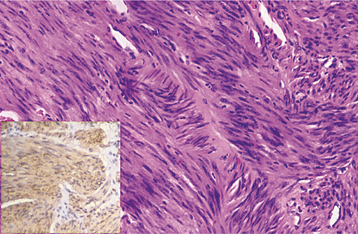

HISTOPATHOLOGIC FEATURES: Palisaded encapsulated neuromas appear well circumscribed and often encapsulated (Fig. 12-54), although this capsule may be incomplete, especially along the superficial aspect of the tumor. Some lesions have a lobulated appearance. The tumor consists of moderately cellular interlacing fascicles of spindle cells that are consistent with Schwann cells. The nuclei are characteristically wavy and pointed, with no significant pleomorphism or mitotic activity. Although the nuclei show a similar parallel orientation within the fascicles, the more definite palisading and Verocay bodies typical of the Antoni A tissue of a neurilemoma are usually not seen. Special stains reveal the presence of numerous axons within the tumor and the cells show a positive immunohistochemical reaction for S-100 protein (Fig. 12-55). Because the tumor is not always encapsulated and the cells are usually not truly palisaded, some pathologists prefer solitary circumscribed neuroma as a better descriptive term for this lesion.

TREATMENT AND PROGNOSIS: The treatment for the palisaded encapsulated neuroma consists of conservative local surgical excision. Recurrence is rare. However, specific recognition of this lesion is important because it is not associated with neurofibromatosis or multiple endocrine neoplasia (MEN) type 2B.

NEURILEMOMA (SCHWANNOMA)

The neurilemoma is a benign neural neoplasm of Schwann cell origin. It is relatively uncommon, although 25% to 48% of all cases occur in the head and neck region. Bilateral neurilemomas of the auditory-vestibular nerve are a characteristic feature of the hereditary condition, neurofibromatosis type II (NF2).

CLINICAL AND RADIOGRAPHIC FEATURES: The solitary neurilemoma is a slow-growing, encapsulated tumor that typically arises in association with a nerve trunk. As it grows, it pushes the nerve aside. Usually, the mass is asymptomatic, although tenderness or pain may occur in some instances. The lesion is most common in young and middle-aged adults and can range from a few millimeters to several centimeters in size.

The tongue is the most common location for oral neurilemomas, although the tumor can occur almost anywhere in the mouth (Fig. 12-56). On occasion, the tumor arises centrally within bone and may produce bony expansion. Intraosseous examples are most common in the posterior mandible and usually appear as either unilocular or multilocular radiolucencies on radiographs. Pain and paresthesia are not unusual for intrabony tumors.

NF2 is an autosomal dominant condition caused by a mutation of a tumor suppressor gene on chromosome 22, which codes for a protein known as merlin. In addition to bilateral neurilemomas (“acoustic neuromas”) of the vestibular nerve, patients also develop neurilemomas of peripheral nerves, plus meningiomas and ependymomas of the central nervous system (CNS). Characteristic symptoms include progressive sensorineural deafness, dizziness, and tinnitus.

HISTOPATHOLOGIC FEATURES: The neurilemoma is usually an encapsulated tumor that demonstrates two microscopic patterns in varying amounts: (1) Antoni A and (2) Antoni B. Streaming fascicles of spindle-shaped Schwann cells characterize Antoni A tissue. These cells often form a palisaded arrangement around central acellular, eosinophilic areas known as Verocay bodies (Fig. 12-57). These Verocay bodies consist of reduplicated basement membrane and cytoplasmic processes. Antoni B tissue is less cellular and less organized; the spindle cells are randomly arranged within a loose, myxomatous stroma. Typically, neurites cannot be demonstrated within the tumor mass. The tumor cells will show a diffuse, positive immunohistochemical reaction for S-100 protein.

Fig. 12-57 Neurilemoma. A, Low-power view showing well-organized Antoni A tissue (right) with adjacent myxoid and less organized Antoni B tissue (left). B, The Schwann cells of the Antoni A tissue form a palisaded arrangement around acellular zones known as Verocay bodies.

Degenerative changes can be seen in some older tumors (ancient neurilemomas). These changes consist of hemorrhage, hemosiderin deposits, inflammation, fibrosis, and nuclear atypia. However, these tumors are still benign, and the pathologist must be careful not to mistake these alterations for evidence of a sarcoma.

TREATMENT AND PROGNOSIS: The solitary neurilemoma is treated by surgical excision, and the lesion should not recur. Malignant transformation does not occur or is extremely rare.

Vestibular schwannomas in patients with NF2 are difficult to manage. Surgical removal is indicated for large symptomatic tumors, but this almost always results in total deafness and risks facial nerve damage. Stereotactic radiosurgery may be considered for older adult or frail patients, as well as for individuals who decline traditional surgery.

NEUROFIBROMA

The neurofibroma is the most common type of peripheral nerve neoplasm. It arises from a mixture of cell types, including Schwann cells and perineural fibroblasts.

CLINICAL AND RADIOGRAPHIC FEATURES: Neurofibromas can arise as solitary tumors or be a component of neurofibromatosis (see page 529). Solitary tumors are most common in young adults and present as slow-growing, soft, painless lesions that vary in size from small nodules to larger masses. The skin is the most frequent location for neurofibromas, but lesions of the oral cavity are not uncommon (Figs. 12-58 and 12-59). The tongue and buccal mucosa are the most common intraoral sites. On rare occasions, the tumor can arise centrally within bone, where it may produce a well-demarcated or poorly defined unilocular or multilocular radiolucency (Fig. 12-60).

HISTOPATHOLOGIC FEATURES: The solitary neurofibroma often is well circumscribed, especially when the proliferation occurs within the perineurium of the involved nerve. Tumors that proliferate outside the perineurium may not appear well demarcated and tend to blend with the adjacent connective tissues.

The tumor is composed of interlacing bundles of spindle-shaped cells that often exhibit wavy nuclei (Figs. 12-61 and 12-62). These cells are associated with delicate collagen bundles and variable amounts of myxoid matrix. Mast cells tend to be numerous and can be a helpful diagnostic feature. Sparsely distributed small axons usually can be demonstrated within the tumor tissue by using silver stains. Immunohistochemically, the tumor cells show a scattered, positive reaction for S-100 protein.

TREATMENT AND PROGNOSIS: The treatment for solitary neurofibromas is local surgical excision, and recurrence is rare. Any patient with a lesion that is diagnosed as a neurofibroma should be evaluated clinically for the possibility of neurofibromatosis (see next topic). Malignant transformation of solitary neurofibromas can occur, although the risk appears to be remote, especially compared with that in patients with neurofibromatosis.

NEUROFIBROMATOSIS TYPE I (VON RECKLINGHAUSEN’S DISEASE OF THE SKIN)

Neurofibromatosis is a relatively common hereditary condition that is estimated to occur in one of every 3000 births. At least eight forms of neurofibromatosis have been recognized, but the most common form is neurofibromatosis type I (NF1), which is discussed here. This form of the disease, also known as von Recklinghausen’s disease of the skin, accounts for 85% to 97% of cases and is inherited as an autosomal dominant trait (although 50% of all patients have no family history and apparently represent new mutations). It is caused by a variety of mutations of the NF1 gene, which is located on chromosome region 17q11.2 and is responsible for a tumor suppressor protein product known as neurofibromin.

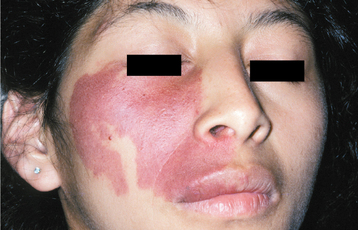

CLINICAL AND RADIOGRAPHIC FEATURES: The diagnostic criteria for NF1 are summarized in Box 12-1. Patients have multiple neurofibromas that can occur anywhere in the body but are most common on the skin. The clinical appearance can vary from small papules to larger soft nodules to massive baggy, pendulous masses (elephantiasis neuromatosa) on the skin (Figs. 12-63 and 12-64). The plexiform variant of neurofibroma, which feels like a “bag of worms,” is considered pathognomonic for NF1. The tumors may be present at birth, but they often begin to appear during puberty and may continue to develop slowly throughout adulthood. Accelerated growth may be seen during pregnancy. There is a wide variability in the expression of the disease. Some patients have only a few neurofibromas; others have literally hundreds or thousands of tumors. However, two thirds of patients have relatively mild disease.

Another highly characteristic feature is the presence of café au lait (coffee with milk) pigmentation on the skin (Fig. 12-65). These spots are smooth-edged, yellow-tan to dark-brown macules that vary in diameter from 1 to 2 mm to several centimeters. They are usually present at birth or may develop during the first year of life. Axillary freckling (Crowe’s sign) is also a highly suggestive sign.

Fig. 12-65 Neurofibromatosis type I. Same patient as depicted in Fig. 12-63. Note the café au lait pigmentation on the arm.

Lisch nodules, translucent brown-pigmented spots on the iris, are found in nearly all affected individuals. The most common general medical problem is hypertension, which may develop secondary to coarctation of the aorta, pheochromocytoma, or renal artery stenosis. Other possible abnormalities include CNS tumors, macrocephaly, mental deficiency, seizures, short stature, and scoliosis.

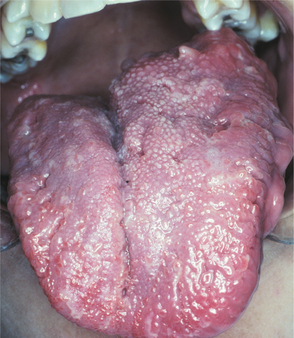

In the past, oral lesions were estimated to occur in 4% to 7% of cases (Fig. 12-66). However, two studies suggest that oral manifestations may occur in as many as 72% to 92% of cases, especially if a detailed clinical and radiographic examination is performed. The most common reported finding is enlargement of the fungiform papillae (in about 50% of all affected patients); however, the specificity of this finding for neurofibromatosis is unknown. Only about 25% of patients examined in these two studies exhibited actual intraoral neurofibromas. Radiographic findings may include enlargement of the mandibular foramen, enlargement or branching of the mandibular canal, increased bone density, concavity of the medial surface of the ramus, and increase in dimension of the coronoid notch.

Fig. 12-66 Neurofibromatosis type I. Intraoral involvement characterized by unilateral enlargement of the tongue.

Several unusual clinical variants of NF1 have been described. On occasion, the condition can include unilateral enlargement that mimics hemifacial hyperplasia (see page 38). In addition, several patients with NF1 have been described with associated Noonan syndrome or with central giant cell granulomas of the jaw.

TREATMENT AND PROGNOSIS: There is no specific therapy for NF1, and treatment often is directed toward prevention or management of complications. Facial neurofibromas can be removed for cosmetic purposes. Carbon dioxide (CO2) laser and dermabrasion have been used successfully for extensive lesions.

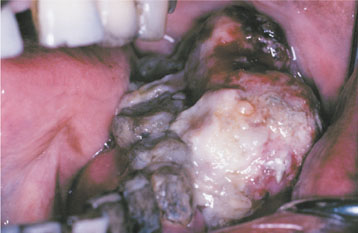

One of the most feared complications is the development of cancer, most often a malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumor (neurofibrosarcoma; malignant schwannoma), which has been reported to occur in about 5% of cases. These tumors are most common on the trunk and extremities, although head and neck involvement is occasionally seen (Figs. 12-67 to 12-69). The prognosis for malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumors associated with neurofibromatosis is poor, with a 5-year survival rate of only 15%. Other malignancies also have been associated with neurofibromatosis, including CNS tumors, pheochromocytoma, leukemia, rhabdomyosarcoma, and Wilms’ tumor. The average lifespan of individuals with NF1 is 15 years less than the general population, mostly related to vascular disease and malignant neoplasms.

Fig. 12-67 Neurofibromatosis type I. Malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumor of the left cheek in a patient with type I neurofibromatosis. (From Neville BW, Hann J, Narang R et al: Oral neurofibrosarcoma associated with neurofibromatosis type I, Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol 72:456-461, 1991.)

Fig. 12-68 Neurofibromatosis type I. Same patient as depicted in Fig. 12-67. Note the intraoral appearance of malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumor of the mandibular buccal vestibule. The patient eventually died of this tumor. (From Neville BW, Hann J, Narang R et al: Oral neurofibrosarcoma associated with neurofibromatosis type I, Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol 72:456-461, 1991.)

Fig. 12-69 Malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumor. High-power view of an intraoral tumor that developed in a patient with neurofibromatosis type I. There is a cellular spindle cell proliferation with numerous mitotic figures.

In recent years, there has been considerable interest in Joseph (not John) Merrick, the so-called Elephant Man. Although Merrick once was mistakenly considered to have neurofibromatosis, it is now generally accepted that his horribly disfigured appearance was not because of neurofibromatosis, but that he most likely had a rare condition known as Proteus syndrome. Because patients with neurofibromatosis may fear acquiring a similar clinical appearance, they should be reassured that they have a different condition. The phrase “Elephant Man disease” is incorrect and misleading, and it should be avoided. Genetic counseling is extremely important for all patients with neurofibromatosis.

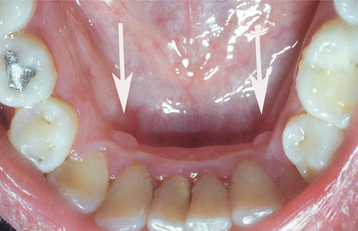

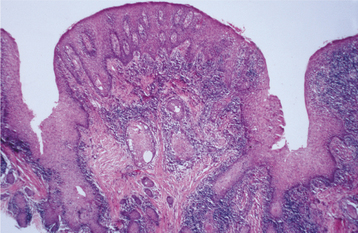

MULTIPLE ENDOCRINE NEOPLASIA TYPE 2B (MULTIPLE ENDOCRINE NEOPLASIA TYPE 3; MULTIPLE MUCOSAL NEUROMA SYNDROME)

The multiple endocrine neoplasia (MEN) syndromes are a group of rare conditions characterized by tumors or hyperplasias of the neuroendocrine tissues. For example, patients with MEN type 1 have benign tumors of the pancreatic islets, adrenal cortex, parathyroid glands, and pituitary gland. MEN type 2A, also known as Sipple syndrome. includes the development of adrenal pheochromocytomas and medullary thyroid carcinoma. In addition to pheochromocytomas and medullary thyroid carcinoma, patients with MEN type 2B have mucosal neuromas that especially involve the oral mucous membranes. Because oral manifestations are most prominent in MEN type 2B, the remainder of the discussion is limited to this condition.

Similar to the other MEN syndromes, MEN type 2B is inherited as an autosomal dominant trait. However, researchers believe that 50% of cases represent spontaneous mutations. The condition is caused by a mutation of the RET protooncogene on chromosome 10, which has been detected in 95% of affected individuals.

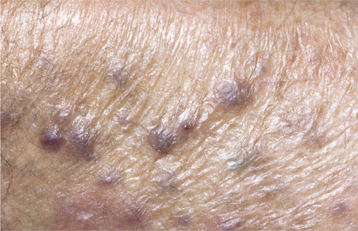

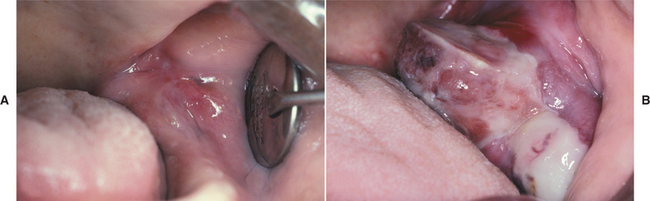

CLINICAL FEATURES: Patients with MEN type 2B usually have a marfanoid body build characterized by thin, elongated limbs with muscle wasting. The face is narrow, but the lips are characteristically thick and protuberant because of the diffuse proliferation of nerve bundles. The upper eyelid sometimes is everted because of thickening of the tarsal plate (Fig. 12-70). Small, pedunculated neuromas may be observable on the conjunctiva, eyelid margin, or cornea.

Fig. 12-70 Multiple endocrine neoplasia (MEN) type 2B. Note the narrow face and eversion of the upper eyelids.

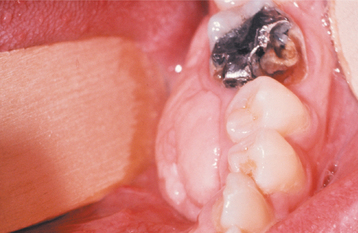

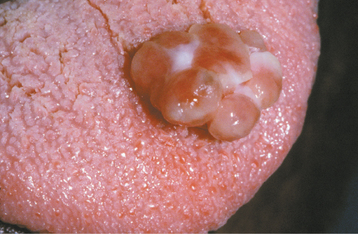

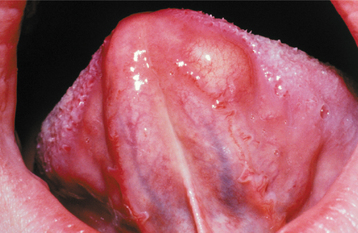

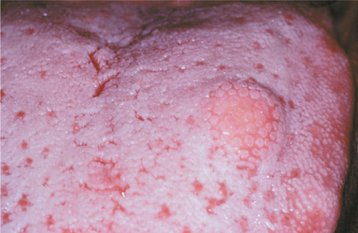

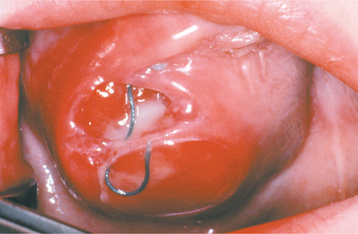

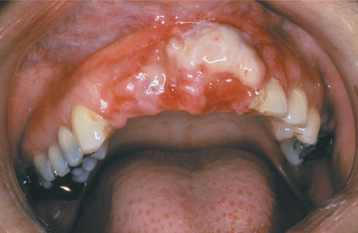

Oral mucosal neuromas are usually the first sign of the condition. These neuromas appear as soft, painless papules or nodules that principally affect the lips and anterior tongue but also may be seen on the buccal mucosa, gingiva, and palate (Fig. 12-71). Bilateral neuromas of the commissural mucosa are highly characteristic.

Fig. 12-71 Multiple endocrine neoplasia (MEN) type 2B. Multiple neuromas along the anterior margin of the tongue and bilaterally at the commissures. (Courtesy of Dr. Emmitt Costich.)

Pheochromocytomas of the adrenal glands develop in at least 50% of all patients and become more prevalent with increasing age. These neuroendocrine tumors are frequently bilateral or multifocal. The tumor cells secrete catecholamines, which result in symptoms such as profuse sweating, intractable diarrhea, headaches, flushing, heart palpitations, and severe hypertension.

The most significant aspect of this condition is the development of medullary carcinoma of the thyroid gland, which occurs in more than 90% of cases. This aggressive tumor arises from the parafollicular cells (C cells), which are responsible for calcitonin production. Medullary carcinoma most often is diagnosed in patients between the ages of 18 and 25, and it shows a marked propensity for metastasis. The average age at death from this neoplasm is 21 years.

LABORATORY VALUES: If medullary carcinoma of the thyroid gland is present, then serum or urinary levels of calcitonin are elevated. An increase in calcitonin levels may herald the onset of the tumor, and calcitonin also can be monitored to detect local recurrences or metastases after treatment. Pheochromocytomas may result in increased levels of urinary vanillylmandelic acid (VMA) and increased epinephrine-to-norepinephrine ratios.

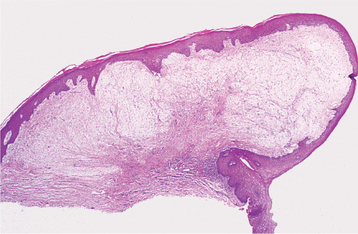

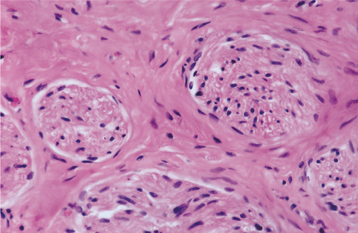

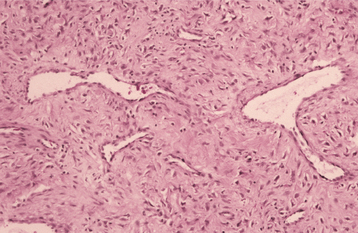

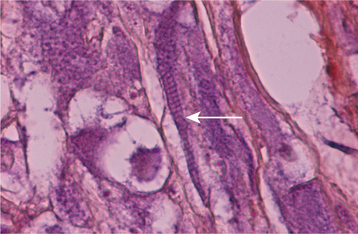

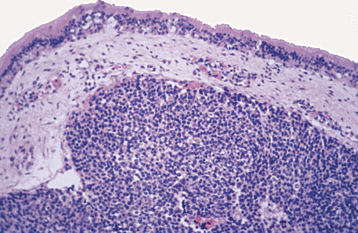

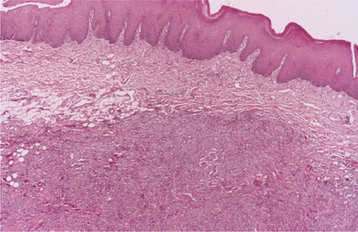

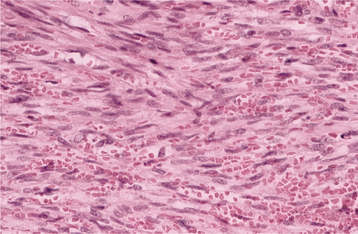

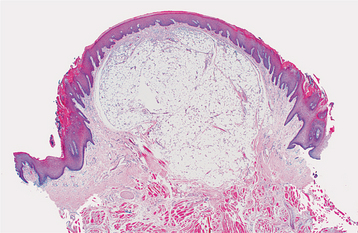

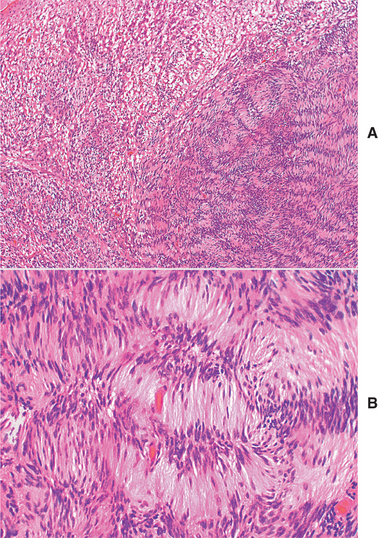

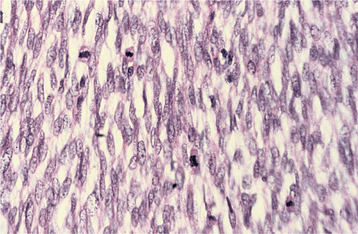

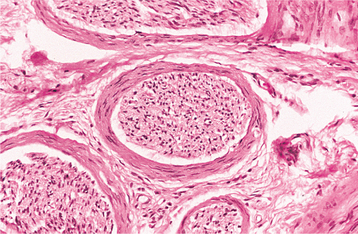

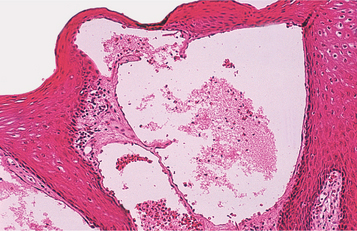

HISTOPATHOLOGIC FEATURES: The mucosal neuromas are characterized by marked hyperplasia of nerve bundles in an otherwise normal or loose connective tissue background (Figs. 12-72 and 12-73). Prominent thickening of the perineurium is typically seen.

Fig. 12-72 Multiple endocrine neoplasia (MEN) type 2B. Low-power view of an oral mucosal neuroma showing marked hyperplasia of nerve bundles.

Fig. 12-73 Multiple endocrine neoplasia (MEN) type 2B. High-power view of the same neuroma as depicted in Fig. 12-72. Note the prominent thickening of the perineurium.

TREATMENT AND PROGNOSIS: The prognosis for patients with MEN type 2B centers on early recognition of the oral features, given the serious nature of the medullary thyroid carcinoma. Some investigators advocate prophylactic removal of the thyroid gland at an early age because medullary carcinoma is almost certain to occur. Once it has developed, this tumor often exhibits an aggressive behavior with a poor prognosis. The patient also should be observed for the development of pheochromocytomas because they may result in a life-threatening hypertensive crisis, especially if surgery with general anesthesia is performed.

MELANOTIC NEUROECTODERMAL TUMOR OF INFANCY

The melanotic neuroectodermal tumor of infancy is a rare pigmented neoplasm that usually occurs during the first year of life. It is generally accepted that this lesion is of neural crest origin. In the past, however, a number of tissues were suggested as possible sources of this tumor. These included odontogenic epithelium and retina, which resulted in various older terms for this entity, such as pigmented ameloblastoma, retinal anlage tumor, and melanotic progonoma. Because these names are inaccurate, however, they should no longer be used. Melanotic (pigmented) neuroectodermal tumor of infancy is the preferred term.

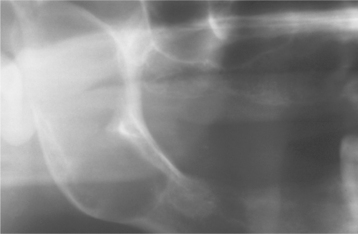

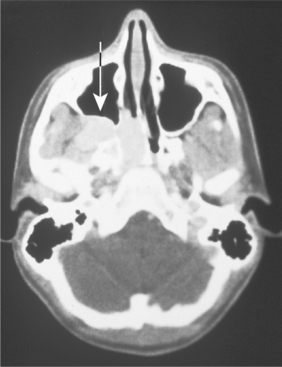

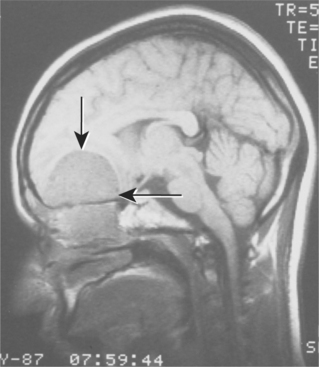

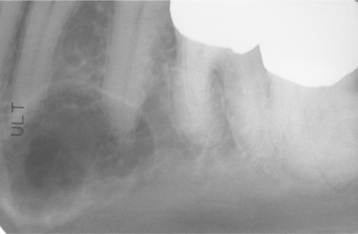

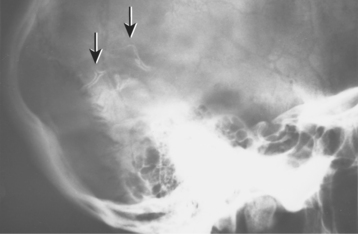

CLINICAL AND RADIOGRAPHIC FEATURES: Melanotic neuroectodermal tumor of infancy almost always develops in young children during the first year of life; only 9% of cases are diagnosed after the age of 12 months. There is a striking predilection for the maxilla, which accounts for 61% of reported cases. Less frequently reported sites include the skull (16%), epididymis and testis (9%), mandible (6%), and brain (6%). A slight male predilection has been noted.

The lesion is most common in the anterior region of the maxilla, where it classically appears as a rapidly expanding mass that is frequently blue or black (Fig. 12-74). The tumor often destroys the underlying bone and may be associated with displacement of the developing teeth (Fig. 12-75). In some instances, there may be an associated osteogenic reaction, which exhibits a “sun ray” radiographic pattern that can be mistaken for osteosarcoma.

LABORATORY VALUES: High urinary levels of vanillylmandelic acid (VMA) often are found in patients with melanotic neuroectodermal tumor of infancy. These levels may return to normal once the tumor has been resected. This finding supports the hypothesis of neural crest origin because other tumors from this tissue (e.g., pheochromocytoma, neuroblastoma) often secrete norepinephrine-like hormones that are metabolized to VMA and excreted in the urine.

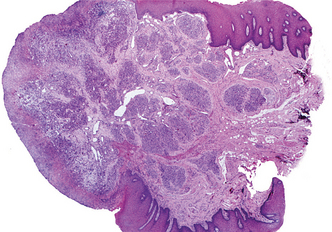

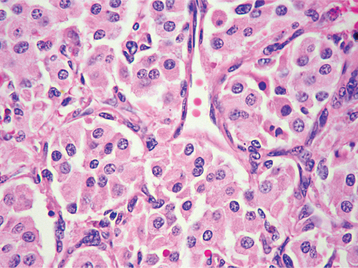

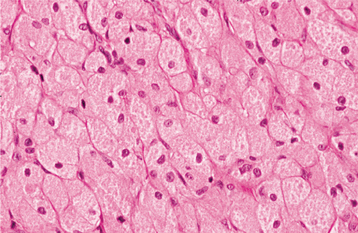

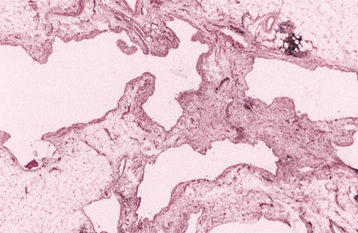

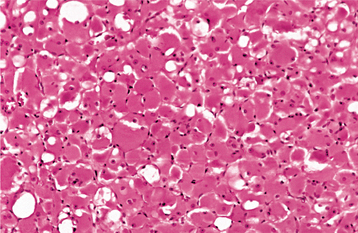

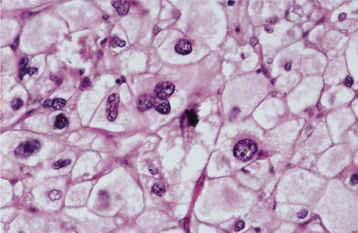

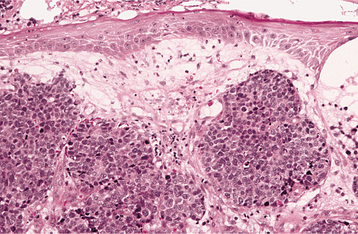

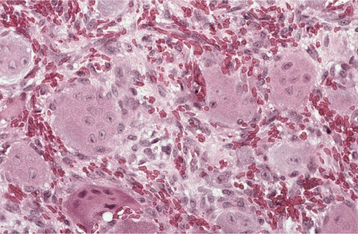

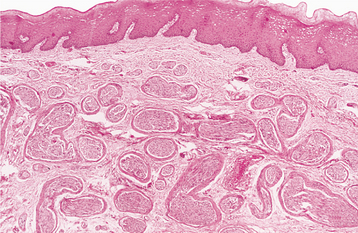

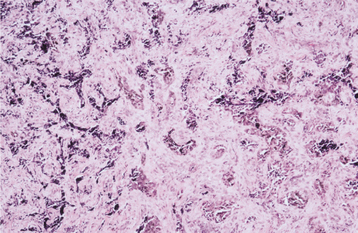

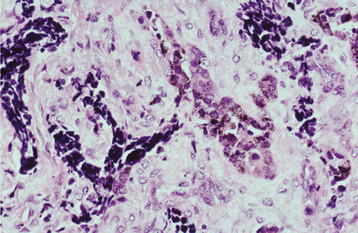

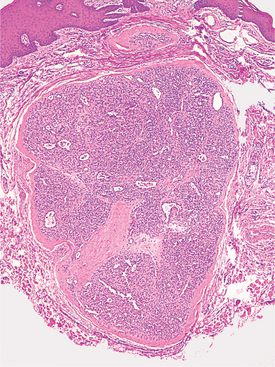

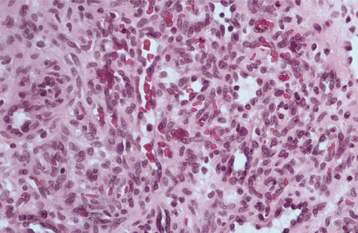

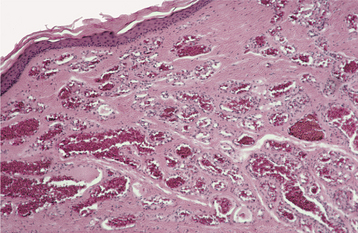

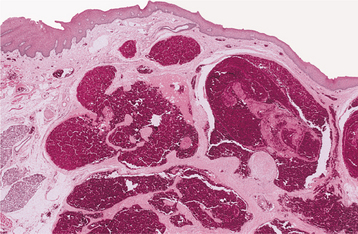

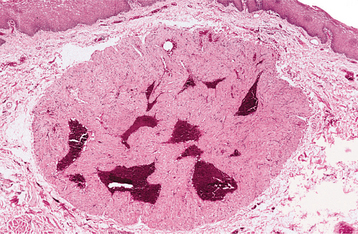

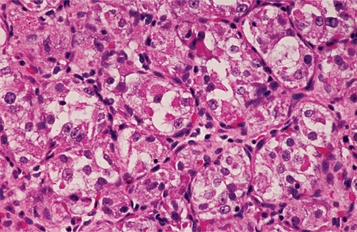

HISTOPATHOLOGIC FEATURES: The tumor consists of a biphasic population of cells that form nests, tubules, or alveolar structures within a dense, collagenous stroma (Figs. 12-76 and 12-77). The alveolar and tubular structures are lined by cuboidal epithelioid cells that demonstrate vesicular nuclei and granules of dark-brown melanin pigment. The second cell type is neuroblastic in appearance and consists of small, round cells with hyperchro-matic nuclei and little cytoplasm. These cells grow in loose nests and are frequently surrounded by the larger pigment-producing cells. Mitotic figures are rare.

Fig. 12-76 Melanotic neuroectodermal tumor of infancy. Low-power view showing nests of epithelioid cells within a fibrous stroma.

Fig. 12-77 Melanotic neuroectodermal tumor of infancy. High-power view of a tumor nest demonstrating two cell types: (1) small, hyperchromatic round cells and (2) larger epithelioid cells with vesicular nuclei. Some stippled melanin pigment is also present.

Because of the tumor’s characteristic microscopic features, immunohistochemistry usually is not essential to establish the diagnosis. However, the larger epithelioid cells typically are positive for cytokeratin and also may express neuron-specific enolase. In addition, the smaller cells usually are positive for neuron-specific enolase and CD56, and sometimes they will express other neuroendocrine markers such as glial fibrillary acidic protein and synaptophysin.

TREATMENT AND PROGNOSIS: Despite their rapid growth and potential to destroy bone, most melanotic neuroectodermal tumors of infancy are benign. The lesion is best treated by surgical removal. Some clinicians prefer simple curettage, although others advocate that a 5-mm margin of normal tissue be included with the specimen. Recurrence of the tumor has been reported in about 20% of cases. In addition, about 6% of reported cases, mostly from the brain or skull, have acted in a malignant fashion, resulting in metastasis and death. Although this estimation of 6% is probably high (because unusual malignant cases are more likely to be reported), it underscores the potentially serious nature of this tumor and the need for careful clinical evaluation and follow-up of affected patients.

PARAGANGLIOMA (CAROTID BODY TUMOR; CHEMODECTOMA; GLOMUS JUGULARE TUMOR; GLOMUS TYMPANICUM TUMOR)

The paraganglia are specialized tissues of neural crest origin that are associated with the autonomic nerves and ganglia throughout the body. Some of these cells act as chemoreceptors, such as the carotid body (located at the carotid bifurcation), which can detect changes in blood pH or oxygen tension and subsequently cause changes in respiration and heart rate. Tumors that arise from these structures are collectively known as paragangliomas, with the term preferably preceded by the anatomic site at which they are located. Therefore, tumors of the carotid body are appropriately known as carotid body paragangliomas (carotid body tumors); those that develop in the temporal bone and middle ear are called jugulotympanic paragangliomas. Jugulotympanic paragangliomas also are commonly known as glomus jugulare tumors, although some authors prefer to reserve this term only for those examples that arise from the jugular bulb and to use the term glomus tympanicum tumors for those that arise in the middle ear.

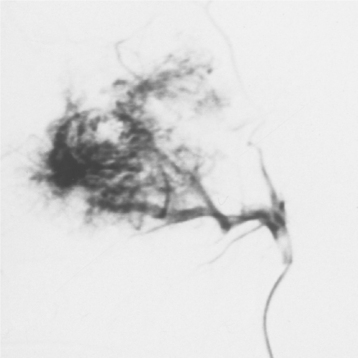

CLINICAL AND RADIOGRAPHIC FEATURES: Although paragangliomas are rare, the head and neck area is the most common site for these lesions. The most common paraganglioma is the carotid body tumor, which develops at the bifurcation of the internal and external carotid arteries. This tumor usually occurs in middle-aged adults. Most often it is a slowly enlarging, painless mass of the upper lateral neck below the angle of the jaw. It is seen more frequently in patients who live at high altitudes, indicating that some cases may arise from chronic hyperplasia of the carotid body in response to lower oxygen levels. Angiography can help to localize the tumor and demonstrate its characteristic vascular nature.

Jugulotympanic paragangliomas are the second most common type of these tumors. They also are most frequent in middle-aged individuals but show a 2:1 female predilection. The most common symptoms include dizziness, tinnitus (a ringing or other noise in the ear), hearing loss, and cranial nerve palsies. Imaging studies, especially three-dimensional (3D) time-of-flight magnetic resonance angiography, can help to detect and characterize such lesions. Other less common paragangliomas of the head and neck include vagal, nasopharyngeal, laryngeal, and orbital paragangliomas.

Approximately 10% to 20% of affected patients have multifocal tumors. In 10% of all cases, there is a family history of such tumors, with an autosomal dominant pattern of inheritance that is modified by genomic imprinting. The gene responsible for familial paragangliomas has been mapped to chromosome 11q23. In genomic imprinting, the gene is transmitted in a mendelian manner, but expression of that gene is determined by the sex of the transmitting parent. Paternal transmission results in development of tumors in the offspring, even if the father is clinically unaffected. Maternal transmission does not result in development of tumors in the offspring, although these children will carry the gene and have the ability to pass it down to subsequent generations. Hereditary cases have an even greater chance of being multicentric; about one third of affected patients have more than one tumor.

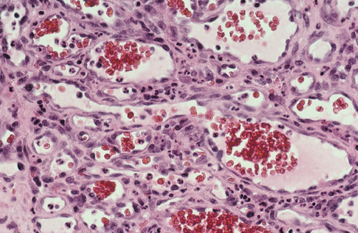

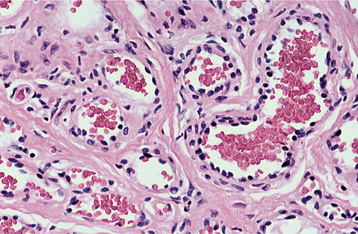

HISTOPATHOLOGIC FEATURES: The paraganglioma is characterized by round or polygonal epithelioid cells that are organized into nests or zellballen (Fig. 12-78). The overall architecture is similar to that of the normal paraganglia, except the zellballen are usually larger and more irregular in shape. These nests consist primarily of chief cells, which demonstrate centrally located, vesicular nuclei and somewhat granular, eosinophilic cytoplasm. The tumor is typically vascular and may be surrounded by a thin fibrous capsule.

TREATMENT AND PROGNOSIS: The treatment of paragangliomas may include surgery, radiation therapy, or both, depending on the extent and location of the tumor. Localized carotid body paragangliomas often can be treated by surgical excision with maintenance of the vascular tree. If the carotid artery is encased by tumor, it also may need to be resected, followed by vascular grafting. Radiation therapy may be used as adjunctive treatment or for unresectable carotid body tumors.

Although most carotid body paragangliomas are benign and can be controlled with surgery and radiation therapy, vascular complications can lead to considerable surgical morbidity or mortality. In addition, 6% to 9% of carotid body paragangliomas metastasize, either to regional lymph nodes or distant sites. Unfortunately, it is usually difficult to predict which tumors will act in a malignant fashion based on their microscopic features. Because such metastases may develop many years after the original diagnosis is made, long-term follow-up is important.

Because of their location near the base of the brain, jugulotympanic paragangliomas are more difficult to manage. Recent advances in both diagnostic radiology and neurosurgery have greatly improved the potential for resection of these tumors. Radiation therapy may be used in conjunction with surgery or as a primary treatment for unresectable tumors. Stereotactic radiosurgery (gamma knife treatment) has shown promise in the management of primary or recurrent glomus jugulare tumors in patients who are poor surgical candidates. This technique allows the delivery of a focused, large, single dose of radiation under stereotactic guidance. Malignant behavior has been documented in approximately 4% of jugulotympanic paragangliomas.

GRANULAR CELL TUMOR

The granular cell tumor is an uncommon benign soft tissue neoplasm that shows a predilection for the oral cavity. The histogenesis of this lesion has long been debated. Originally, it was believed to be of skeletal muscle origin and was called the granular cell myoblastoma. However, more recent investigations do not support a muscle origin but point to a derivation from Schwann cells (granular cell schwannoma) or neuroendocrine cells. At present, it seems best to use the noncommittal term granular cell tumor for this lesion.

CLINICAL FEATURES: Granular cell tumors are most common in the oral cavity and on the skin. The single most common site is the tongue, which accounts for one third to half of all reported cases. Tongue lesions most often occur on the dorsal surface. The buccal mucosa is the second most common intraoral location. The tumor most frequently occurs in the fourth to sixth decades of life and is rare in children. There is a 2:1 female predilection.

The granular cell tumor is typically an asymptomatic sessile nodule that is usually 2 cm or less in size (Figs. 12-79 and 12-80). The lesion often has been noted for many months or years, although sometimes the patient is unaware of its presence. The mass is typically pink, but occasional granular cell tumors appear yellow. The granular cell tumor is usually solitary, although multiple, separate tumors sometimes occur, especially in black patients.

HISTOPATHOLOGIC FEATURES: The granular cell tumor is composed of large, polygonal cells with abundant pale eosinophilic, granular cytoplasm and small, vesicular nuclei (Fig. 12-81). The cells are usually arranged in sheets, but they also may be found in cords and nests. The cell borders often are indistinct, which results in a syncytial appearance. The lesion is not encapsulated and sometimes appears to infiltrate the adjacent connective tissues. Often, there appears to be a transition from normal adjacent skeletal muscle fibers to granular tumor cells; this finding led earlier investigators to suggest a muscle origin for this tumor. Less frequently, one may see groups of granular cells that envelop small nerve bundles. Immunohistochemical analysis reveals positivity for S-100 protein within the cells—a finding that is supportive, but not diagnostic, of neural origin.

Fig. 12-81 Granular cell tumor. Medium-high–power view showing polygonal cells with abundant granular cytoplasm.

An unusual and significant microscopic finding is the presence of acanthosis or pseudoepitheliomatous (pseudocarcinomatous) hyperplasia of the overlying epithelium, which has been reported in up to 50% of all cases (Fig. 12-82). Although this hyperplasia is usually minor in degree, in some cases it may be so striking that it results in a mistaken diagnosis of squamous cell carcinoma and subsequent unnecessary cancer surgery. The pathologist must be aware of this possibility, especially when dealing with a superficial biopsy sample or a specimen from the dorsum of the tongue—an unusual location for oral cancer.

TREATMENT AND PROGNOSIS: The granular cell tumor is best treated by conservative local excision, and recurrence is uncommon. Extremely rare examples of malignant granular cell tumor have been reported.

CONGENITAL EPULIS (CONGENITAL EPULIS OF THE NEWBORN; CONGENITAL GRANULAR CELL LESION): The congenital epulis is an uncommon soft tissue tumor that occurs almost exclusively on the alveolar ridges of newborns. It is often known by the redundant term, congenital epulis of the newborn. Rare examples also have been described on the tongue; therefore, some authors prefer using the term congenital granular cell lesion, because not all cases present as an epulis on the alveolar ridge. It also has been called gingival granular cell tumor of the newborn, but this term should be avoided. Although it bears a light microscopic resemblance to the granular cell tumor (discussed previously), it exhibits ultrastructural and immunohistochemical differences that warrant its classification as a distinct and separate entity. However, the histogenesis of this tumor is still uncertain.

CLINICAL FEATURES: The congenital epulis typically appears as a pink-to-red, smooth-surfaced, polypoid mass on the alveolar ridge of a newborn (Fig. 12-83). Most examples are 2 cm or less in size, although lesions as large as 7.5 cm have been reported. On occasion, the tumor has been detected in utero via ultrasound examination. Multiple tumors develop in 10% of cases. A few rare examples on the tongue have been described in infants who also had alveolar tumors.

The tumor is two to three times more common on the maxillary ridge than on the mandibular ridge. It most frequently occurs lateral to the midline in the area of the developing lateral incisor and canine teeth. The congenital epulis shows a striking predilection for females, which suggests a hormonal influence in its development, although estrogen and progesterone receptors have not been detected. Nearly 90% of cases occur in females.

HISTOPATHOLOGIC FEATURES: The congenital epulis is characterized by large, rounded cells with abundant granular, eosinophilic cytoplasm and round to oval, lightly basophilic nuclei (Figs. 12-84 and 12-85). In older tumors, these cells may become elongated and separated by fibrous connective tissue. In contrast to the granular cell tumor, the overlying epithelium never shows pseudoepitheliomatous hyperplasia but typically demonstrates atrophy of the rete ridges. In addition, in contradistinction to the granular cell tumor, immunohistochemical analysis shows the tumor cells to be negative for S-100 protein.

TREATMENT AND PROGNOSIS: The congenital epulis is usually treated by surgical excision. The lesion never has been reported to recur, even with incomplete removal.

After birth, the tumor appears to stop growing and may even diminish in size. Eventual complete regression has been reported in a few patients, even without treatment (Fig. 12-86).

HEMANGIOMA AND VASCULAR MALFORMATIONS

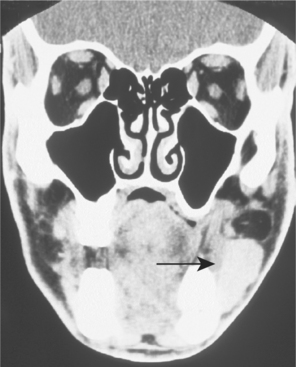

In recent years, great progress has been made in the classification and understanding of tumors and tumorlike proliferations of vascular origin. A modified classification scheme for these vascular anomalies is presented in Box 12-2.