Chapter 36 Oral unit dosage forms

Introduction

Tablets and capsules are the most popular way of delivering a drug for oral use. They are convenient for the patient and are usually easy to handle and identify. They are mass produced on a commercial scale at a relatively low manufacturing cost. Because they are manufactured by the pharmaceutical industry where quality assurance is in place, a high accuracy of dosage is achievable with oral unit dosage forms and they are free from the problems of stability found in aqueous mixtures and suspensions. Packaging in blister packs can also enhance the stability of these dosage forms (see Ch. 27). Their main disadvantages are that there is a slower onset of action relative to liquids and some people have difficulty swallowing solid oral dosage forms, e.g. the very young or very old.

Tablets

Tablets are solid preparations each containing a single dose of one or more active ingredient(s). They are normally prepared by compressing uniform volumes of particles, although some tablets are prepared by moulding. The process of tablet production is outside the scope of this book, but can be found in Aulton (2007) or the Pharmaceutical Codex.

Many different types of tablet are available, which may also be in a variety of shapes and sizes. The types include dispersible, effervescent, chewable, sublingual and buccal tablets, lozenges, tablets for rectal or vaginal administration and solution tablets. Some tablets are designed to release the drug after a time lag, or slowly for a prolonged drug release or sustained drug action (see Ch. 21). The design of these modified-release tablets uses formulation techniques to control the biopharmaceutical behaviour of the drug. These issues are discussed in Aulton (2007).

In addition to the drug(s), several excipients must be added. These will aid the process of tableting and ensure that the active ingredient will be released as intended. Excipients include:

Some tablets have coatings, such as sugar coating or film coating. Coatings can protect the tablet from environmental damage, mask an unpleasant taste, aid identification of the tablet and enhance its appearance. Enteric coatings on tablets resist dissolution or disruption of the tablet in the stomach, but not in the intestine. This is useful when a drug is destroyed by gastric acid, is irritating to the gastric mucosa, or when bypassing the stomach aids drug absorption. See Aulton (2007) for details about coatings and other specialized formulation and manufacturing techniques.

Dispensing of tablets

Many tablets in the UK and other countries are packaged by the manufacturer into patient packs suitable for issue to the patient without repacking by the pharmacist. Patient information leaflets are also contained in these patient packs. When dispensing these packs to patients, the pharmacist must ensure that they are labelled correctly, according to the prescriber’s instructions (see Ch. 28), and that the patient is counselled on the use of the medication (see Ch. 44). Further supplies of patient information leaflets are available from the manufacturer when required. For some controlled-release tablets, variations in bioavailability may occur with different brands. It is important that patients are given the brand that they are stabilized on in order to maintain therapeutic outcome. Examples where this is important include theophylline, lithium and phenytoin.

Tablets may also be supplied in a bulk container. The required number of tablets needs to be counted out (see Ch. 25) and placed in a suitable container for dispensing to the patient (see Ch. 27). It is important to minimize errors by ensuring that the correct bulk container has been selected and the correct drug dispensed. The pharmacist should verify this by checking the label of the bulk container and by examining the shape, size and markings on the dispensed tablets where appropriate, with the prescription. A copy of the patient information leaflet should be included.

Some tablets are supplied in a strip-packed form where each tablet has its own blister. A development of this is the calendar pack where the day or date on which the tablet is to be taken is indicated on the pack.

Shelf life and storage of tablets

Most tablets should be stored in airtight packaging, protected from light and extremes of temperature. When stored properly they generally have a long shelf life. The expiry date will be printed on the package or the individual strip packs. Some tablets need to be stored in a cool place, e.g. Ketovite® and Leukeran® (chlorambucil) (both stored between 2 and 8 °C). Some tablets contain volatile drugs, e.g. glyceryl trinitrate, and must be packed in glass containers with tightly fitting metal screw caps (see Ch. 27). An additional warning must be placed on these tablets, when dispensed to patients, to advise them to throw away the tablets 8 weeks after opening, as they lose potency.

Containers for tablets

Strip or blister packs are dispensed in a paperboard box and tablets counted from bulk containers are placed in amber glass or plastic containers with airtight, child-resistant closures.

Special labels and advice on tablets

Most tablets should be swallowed with a glass, or ‘draught’, of water. A draught of water refers to a volume of water of about 50 mL. This prevents the dosage form becoming lodged in the oesophagus, which can cause problems such as ulceration. Tablets may be coated and shaped to aid swallowing.

Some tablets should be dissolved or dispersed in water before taking, e.g. effervescent analgesic tablets. Other tablets, particularly those with coatings or modified-release properties, should be swallowed whole. There are also some tablets which should be chewed or sucked before swallowing, e.g. antacid tablets. Appropriate labels should be placed on the container (see Ch. 28).

Coated tablets, e.g. enteric coatings, require specific advice on avoiding indigestion remedies at the same time of day, as these will affect the pH of the stomach, and therefore cause premature breakdown of the enteric coating on the tablet.

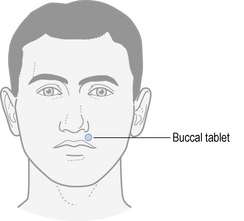

Buccal and sublingual tablets are not swallowed whole and it is important that patients know how to use them. If these formulations are swallowed then they will not have their intended therapeutic effect. Figure 36.1 illustrates the positioning for buccal tablets. Sublingual tablets are placed under the tongue.

Capsules

Capsules are solid preparations intended for oral administration made with a hard or soft gelatin shell. One (or more) medicament is enclosed within this gelatin container. Most capsules are swallowed whole, but some contain granules which provide a useful premeasured dose for administering in a similar way to a powder, e.g. formulations of pancreatin. Some capsules enclose enteric-coated pellets, e.g. Erymax (erythromycin). Capsules are elegant, easy to swallow and can be useful in masking unpleasant tastes. Capsules may also be used to hold powder or oils for inhalation, e.g. Intal® capsules (sodium cromoglicate) or Karvol®, or for rectal and vaginal administration, e.g. Gyno-Daktarin® (miconazole nitrate) (see Ch. 34).

Soft shell capsules

A soft gelatin capsule consists of a flexible solid shell containing powders, non-aqueous liquids, solutions, emulsions, suspensions or pastes. Such capsules allow liquids to be given as solid dosage forms, e.g. cod liver oil. They also offer accurate dosage, improved stability and overcome some of the problems of dealing with powders. They are formed, filled and sealed in one manufacturing process.

Hard shell capsules

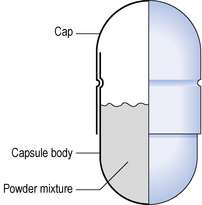

Empty capsule shells are made from gelatin and are clear, colourless and essentially tasteless. Colourings and markings can be easily added for light protection and to ease identification. The shells are used in the preparation of most manufactured capsules and for the extemporaneous compounding of capsules. The shell comprises two sections, the body and the cap, both being cylindrical and sealed at one end. Powder or particulate solid, such as granules and pellets, can be placed in the body and the capsule closed by bringing the body and cap together (Fig. 36.2). Some capsules have small indentations on the body and cap which ‘lock’ together. If not, they must be sealed by moistening the outside top of the body before putting the top in place. Technical aspects of capsule manufacture are given in Aulton (2007).

Compounding of capsules

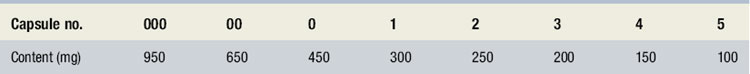

Occasionally hand filling of capsules may be required, particularly in a hospital pharmacy or when preparing materials for clinical trials. A suitable size of capsule shell should be selected so that the finished capsule looks reasonably full. Hard shell capsules are available in eight sizes. These are listed in Table 36.1, with the corresponding approximate capacity (based on lactose). The bulk density of a powder mixture will also affect the choice of capsule size.

Calculations for compounding capsules

The recommended minimum weight for filling a capsule is 100 mg. If the required weight of the drug is smaller than this, a diluent should be added by trituration (see Ch. 35). If the quantity of the drug for a batch of capsules is smaller than the minimum weighable amount, 100 mg on a Class B balance, then trituration will also be required. Lactose, magnesium carbonate, starch, kaolin and calcium phosphate are commonly used diluents. To allow for small losses of powder, an excess should be calculated, e.g. two extra capsules. Example 36.1 gives a worked example.

Example 36.1

Caps atropine sulphate 600 micrograms. Mitte 4.

Caps atropine sulphate 600 micrograms. Mitte 4.

Atropine sulphate (6 × 600) = 3600 micrograms = 3.6 mg.

Lactose (6 × 100 mg) to 600 mg.

Step A

| Atropine sulphate | 100 mg |

| Lactose | 900 mg |

Mix by doubling-up in a small mortar and pestle. Weigh 100 mg of this mixture (triturate A). Triturate A contains 10 mg of atropine sulphate.

Filling capsules

The number of capsules to be filled should be taken first and set to one side. This avoids the danger of contaminating empty capsules. The powder to be encapsulated should be finely sifted (180 μm sieve) and prepared. Magnesium stearate (up to 1% weight in weight (w/w)) and silica may be added as a lubricant and glidant respectively, to aid filling of the capsule. Various methods of filling capsules on a small scale are possible.

Filling from a powder mass

The prepared powder can be placed on a clean tile or piece of demy paper and powder pushed into the capsule body with the aid of a spatula until the required weight has been enclosed. The empty capsule body could also be ‘punched’ into a heap of powder until filled. Alternatively create a small funnel from demy paper and fill the capsule body with the required weight. Gloves or rubber finger cots should be worn to protect the capsules from handling with bare fingers.

Filling with weighed aliquots

Weighed aliquots of powder may be placed on paper and channelled into the empty capsule shell. A sharp fold in the paper helps direct the powder. Alternatively, simple apparatus is available for small-scale manufacture of larger numbers of capsules. A plastic plate with rows of cavities to hold the empty capsule bodies is used, different rows holding different sizes of capsules. A plastic bridge containing a row of holes corresponding to the position of the capsule cavities can then be used to support a long-stemmed funnel. The end of the funnel passes into the mouth of the capsule below. The stem of the funnel should be as wide as possible for the size of the capsule to assist with powder flow. A weighed aliquot of powder can then be poured into the capsule via the funnel. A thin glass or plastic rod or wire may be used to ‘tamp’ the powder to break blockages or to lightly compress the material inside the capsule. After filling the capsule, the top can be fitted loosely and the weight checked before sealing.

Capsules are subject to tests for uniformity of weight and content of active ingredient, and uniformity of content where the content of active ingredient, is less than 2 mg or less than 2% by weight of the total capsule fill.

Shelf life and storage of capsules

If stability data are not available for extemporaneously filled capsules, then a short expiry date (up to 4 weeks) should be given. Manufactured capsules will generally be very stable and will be assigned expiry dates on the container or on the packed strips or blister packs. Most capsules need to be stored in a cool, dry place. Some capsules need to be stored in a cool place, e.g. Restandol (testosterone), which needs to be stored in the refrigerator at 2–8°C until it is dispensed to the patient, when it can be stored at room temperature for 3 months.

Containers for capsules

Containers used are similar to those for tablets. Some capsules are susceptible to moisture absorption, and desiccants may be included in the packaging, either integrally (e.g. in the cap of the container for Losec capsules) or as separate sachets. These capsules have a limited shelf life once dispensed to a patient. Desiccant sachets should not be dispensed to patients, in case they are mistaken for a capsule and ingested.

Special labels and advice on capsules

Capsules should be swallowed whole with a glass of water or other liquid. Advice may be sought from the pharmacist about whether it is acceptable to empty the contents of a capsule onto food or into water for ease of swallowing. In giving this advice, the release characteristics of the dosage form should be considered; for instance, whether it is an enteric-coated or prolonged-release formulation. Additional labels and advice may be required for capsules, depending on the drug contained.

Other oral unit dosage forms

Pastilles

These contain a glycerol and gelatin base. They are sweetened, flavoured and medicated and are popular over the counter remedies for soothing coughs and sore throats.

Cachets

These are very rarely used in practice today. They are made from rice flour and each cachet comes in two halves ready to be filled with powder. They are available as dry seal or wet seal. They are dipped in water then swallowed whole with water and prevent the patient from tasting the powder. Filled cachets are packed in cardboard boxes.

Action and uses. Used in managing acute and chronic psychosis.

Formulation notes. Magnesium stearate is added to act as a lubricant to aid flow of the powder into the capsule. 10 mg is not weighable, so a trituration must be carried out. Lactose acts as a diluent to bring the weight of each capsule fill to 100 mg.

| Trituration for magnesium stearate | |

| Magnesium stearate | 100 mg |

| Lactose | 900 mg |

Take a 100 mg portion of this mixture, which will contain 10 mg of magnesium stearate and 90 mg of lactose.

Method of preparation. Sieve the powders using a 180 μm sieve. Prepare the magnesium stearate triturate. Weigh 100 mg of haloperidol, and mix this with the magnesium stearate triturate in a mortar and pestle. Gradually add 800 mg of lactose to this mixture, by doubling-up. This gives a total powder quantity of 1000 mg (equivalent to 10 × 100 mg capsules). Fill the capsule shells (size 4 or 5) with 100 mg aliquots, checking the weight of each capsule before sealing. Pack eight capsules in an amber glass or plastic tablet container with a child-resistant closure.

Storage and shelf life. Store in a cool, dry place and protect from light. Expiry date of 2 weeks, since stability in capsule form is unknown.

Advice and labelling. ‘Warning. May cause drowsiness. If affected do not drive or operate machinery. Avoid alcoholic drink’ (British National Formulary Label 2).