CHAPTER 68 Head Tilt

GENERAL CONSIDERATIONS

Head tilt is a common neurologic abnormality in dogs and cats. It indicates a lesion of the vestibular system, which consists of central and peripheral parts.

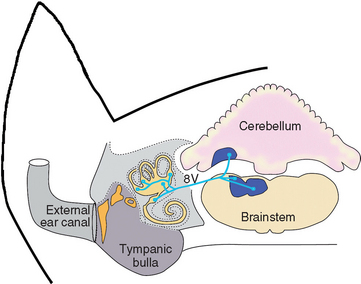

The peripheral vestibular system includes sensory receptors for vestibular input located in the membranous labyrinth of the inner ear within the petrous temporal bone of the skull and the vestibular portion of the vestibulocochlear nerve (CN8), which carries information from these receptors to the brainstem. The central vestibular structures include the brainstem vestibular nuclei and pathways in the medulla oblongata and the flocculonodular lobe of the cerebellum (Fig. 68-1). Abnormalities involving the central or peripheral vestibular system typically cause head tilt, circling, ataxia, rolling, and nystagmus.

FIG 68-1 Anatomy of the central and peripheral vestibular system. Sensory receptors for vestibular input are located in the membranous labyrinth of the inner ear. Input from these receptors enters the brain via the vestibular portion of CN8 (8V), and fibers terminate in central vestibular nuclei in the brainstem and cerebellum.

Nystagmus is defined as an involuntary rhythmic oscillation of the eyeballs. In the jerk nystagmus typical of vestibular disease the eye movements have a slow phase in one direction and a rapid recovery in the opposite direction. Jerk nystagmus direction is defined as the direction of the fast phase. Less common than jerk nystagmus is pendular nystagmus, a slight oscillatory movement of the eyeballs with no slow or fast phase; this condition is most often seen in Siamese, Birman, and Himalyan cats because of a congenital abnormality of the visual pathway.

LOCALIZATION OF THE LESION

Head tilt indicates vestibular dysfunction. The first step in a patient with a head tilt should always be an attempt to localize disease to either the central or the peripheral components of the vestibular system (Box 68-1). The clinician can usually accomplish this goal with a careful physical and neurological examination.

PERIPHERAL AND CENTRAL VESTIBULAR DISEASE

Severe problems of balance resulting in ataxia, incoordination, falling, and rolling are prominent in animals with either central or peripheral vestibular disease. The head tilt (ear pointed toward the ground) is typically on the same side as the lesion, and tight circling toward that side is common. Ipsilateral strabismus may be seen when the nose is elevated. Vomiting, salivation, and other signs of motion sickness are often apparent.

Nystagmus observed when the head is held motionless is called spontaneous nystagmus or resting nystagmus. Nystagmus that develops only when the head is held in an unusual position is called positional nystagmus. Some animals with compensated vestibular disease (either central or peripheral) do not have detectable spontaneous nystagmus but develop positional nystagmus when they are rolled over on their back (see Fig. 63-23). Nystagmus in a patient with peripheral vestibular disease is always either horizontal or rotary, and although the intensity of nystagmus may change when the head is held in different positions, the direction will not. The nystagmus in animals with central vestibular diseases can be horizontal, rotary, or vertical and may change direction as the position of the head is changed.

PERIPHERAL VESTIBULAR DISEASE

Animals with peripheral vestibular disease should have normal mentation and consciousness. They have normal strength and postural reactions, although these tests may be difficult to assess because affected animals have impaired balance and a tendency to fall and roll. Spontaneous and positional nystagmus is horizontal or rotary or alternates between the two and will not change fast-phase direction when the animal is held in multiple positions or examined repeatedly during the day. Damage to inner ear receptors or the axons of CN8 results in vestibular dysfunction and sometimes deafness. Disorders that affect both the middle and inner ear will sometimes damage the axons of the facial nerve (CN 7) and the sympathetic innervation to the eye, resulting in concurrent facial nerve paralysis, Horner’s syndrome, and peripheral vestibular dysfunction (Fig. 68-2).

CENTRAL VESTIBULAR DISEASE

Early in the course of disease, animals with central vestibular dysfunction may not have clinical features that readily distinguish them from animals with peripheral vestibular dysfunction. With time and progression, however, they usually develop additional signs indicating brainstem involvement. Mentation may be dull or depressed or behavior may be altered as the ascending reticular activating system is disrupted. Ipsilateral paresis and postural reaction deficits (abnormal knuckling, hopping) develop on the side of the lesion as the upper motor neuron pathways to the limbs are involved, and affected animals may lose the ability to walk. Although spontaneous nystagmus can be in any direction, a vertical nystagmus or a nystagmus that changes directions with different head positions indicates central vestibular disease. The presence of cranial nerve abnormalities other than facial nerve paralysis and Horner’s syndrome in an animal with vestibular signs usually indicates central (i.e., brainstem) disease. Neoplasms or granulomas located at the cerebellomedullary angle often result in simultaneous dysfunction of the vestibular (CN8), facial (CN7), and trigeminal (CN5) nerves, so the trigeminal nerve (i.e., facial and nasal sensation) should always be assessed in animals with vestibular signs.

PARADOXICAL VESTIBULAR SYNDROME

Vestibular signs can be seen with lesions affecting the caudal cerebellar peduncle or the flocculonodular lobe of the cerebellum. This syndrome is called paradoxical vestibular syndrome because affected animals have a head tilt and circling away from the lesion and a fast phase nystagmus directed toward the lesion. Postural reaction deficits, when present, are on the side of the lesion and are therefore the most reliable clinical feature allowing lesion localization. Other signs of cerebellar dysfunction, such as hypermetria, truncal sway, and head tremor, are often seen. Diagnostic evaluation is the same as that for central vestibular disease and other intracranial disorders (see Chapter 65).

PERIPHERAL VESTIBULAR DISEASE

Peripheral vestibular disease is much more common in dogs and cats than central disease and generally carries a better prognosis. The most common disorders causing peripheral vestibular signs are infection, polyps, or neoplasia affecting the middle and inner ear and transient idiopathic vestibular syndromes. Peripheral vestibular disease can also occur as a congenital problem; as a result of trauma; and, rarely, as a result of aminoglycoside-induced receptor degeneration (Box 68-2). Peripheral vestibular signs with or without facial nerve paralysis have also been seen in hypothyroid-associated polyneuropathy in dogs.

Diagnostic evaluation of patients with peripheral vestibular signs should include a thorough otoscopic examination and external palpation of the bullae for asymmetry or pain. Ototoxic drugs or treatments should be discontinued and systemic evaluation for inflammatory or metabolic disease performed. Radiographs, computed tomography (CT), or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the tympanic bullae (middle ear) should be evaluated with the patient under general anesthesia before ear flushing is performed. When warranted, a myringotomy can then be used to collect a sample from the middle ear for cytological analysis and culture.

DISORDERS CAUSING PERIPHERAL VESTIBULAR SIGNS

Otitis Media-Interna

Otitis media-interna (OM-OI) is one of the most common causes of peripheral vestibular signs in dogs and cats. Concurrent facial nerve paralysis or Horner’s syndrome affecting the same side is sometimes apparent (Fig. 68-3; see also Fig. 68-2). All dogs and cats with peripheral vestibular disease should be evaluated for ear disease. Most animals with OM-OI have obvious otitis externa, and many have a tympanic membrane that appears abnormal or ruptured. Occasionally, the otoscopic examination is normal.

FIG 68-3 A, Adult Cocker Spaniel with left peripheral vestibular disease caused by otitis media-interna. B, Radiograph reveals thickening of the left bulla wall with an increase in density within the bulla. Osteotomy of the ventral bulla revealed bilateral otitis media-interna.

Skull radiographs can be evaluated for changes in the tympanic bullae suggesting chronic inflammatory disease, trauma, or tumor. Ventrolateral, oblique, lateral, and open-mouth radiographs of the skull should be performed with the patient under general anesthesia. Radiographic evidence of OM-OI includes increased thickness of the bones of the tympanic bullae and petrous temporal bone and increased fluid or soft-tissue density within the tympanic bullae (see Figs. 71-7 and 68-3). Because radiographs may be normal with acute infections, more sensitive advanced imaging techniques (CT and MRI) are recommended if radiographs are nondiagnostic.

While the animal is sedated or anesthetized, a culture should be obtained from the external ear canal and the ear canal and the tympanic membrane should be carefully examined using an otoscope or a small endoscope. If imaging suggests that fluid is present within the middle ear, a sample of that fluid should be collected for cytology and culture. If the tympanic membrane is ruptured, the sample can be obtained directly under visualization. If the tympanic membrane appears to be intact, the external ear canal can be cleaned by flushing with warm 0.9% saline until the fluid obtained is clear, and then a myringotomy may be performed. Using a 22-gauge, 3.5-inch spinal needle attached to a 6-ml syringe, the clinician punctures the tympanic membrane just caudal to the malleus at the 6 o’clock position and gently aspirates fluid from the middle ear into the syringe. If fluid is not obtained, 0.5 to 1.0 ml of sterile saline can be instilled and then aspiration can be repeated. After the diag nostic sample is obtained, the middle ear should be flushed repeatedly with sterile saline to remove exudate from the bulla.

Medical treatment of dogs and cats with bacterial OM-OI consists of a 4- to 6-week course of systemic antibiotics, with the choice of antibiotic based on culture and sensitivity results. Pending culture results, antibiotic treatment can be initiated using a broad-spectrum antibiotic such as a first-generation cephalosporin (cephalexin, 22 mg/kg, administered orally q8h), a combination of amoxicillin and clavulanic acid (Clavamox, 12.5 to 25 mg/kg, administered orally q8h), or enrofloxacin (5 mg/kg, administered orally q12h). If conservative treatment does not resolve the infection or if there is radiographic evidence of chronic bone changes in the bulla, ventral bulla osteotomy should be performed, followed by a course of antibiotic therapy. Early recognition of OM-OI and prompt initiation of appropriate therapy result in a good prognosis for recovery. The facial nerve paralysis may be permanent in spite of treatment. Failure to treat OM-OI aggressively can result in ascent of the infection up the nerves into the brainstem, resulting in neurologic deterioration, central vestibular signs, and often death.

Geriatric Canine Vestibular Disease

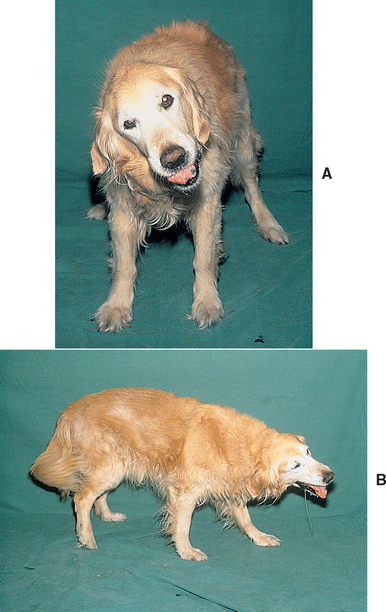

Geriatric canine vestibular disease (i.e., old dog vestibular disease), an idiopathic syndrome, is the most common cause of acute unilateral peripheral vestibular dysfunction in old dogs, with a mean age of onset of 12.5 years. The disorder is characterized by the very sudden onset of head tilt, loss of balance, and ataxia with a horizontal or rotatory nystagmus (Fig. 68-4). Proprioception and postural reactions are normal, although they may be difficult to assess. Facial paresis and Horner’s syndrome are not present, and no other neurologic abnormalities are observed. Approximately 30% of affected dogs have transient nausea, vomiting, and anorexia.

FIG 68-4 A and B, A 12-year-old Golden Retriever with head and body tilt caused by geriatric canine vestibular disease.

Any older dog with a peracute onset of unilateral peripheral vestibular disease with no other neurologic abnormalities should be suspected to have geriatric canine vestibular disease. A careful physical examination, neurologic examination, and otoscopic examination should be performed. Further extensive diagnostic testing is often delayed for a few days while the dog is supported and monitored for improvement.

The diagnosis of geriatric canine vestibular disease is based on the signalment, neurologic findings, exclusion of other causes of peripheral vestibular dysfunction, and alleviation of clinical signs with time. The spontaneous nystagmus usually resolves within a few days and is replaced by a transient positional nystagmus in the same direction. The ataxia gradually abates during 1 to 2 weeks, as does the head tilt. Occasionally, the head tilt is permanent.

The prognosis for recovery is excellent; no therapy is recommended. When vomiting is severe, H1 histaminergic receptor antagonists (diphenhydramine, 2 to 4 mg/kg, administered subcutaneously q8h), M1 cholinergic receptor antagonists (chlorpromazine, 1 to 2 mg/kg, administered orally q8h), or vestibulosedative drugs (meclizine, 1 to 2 mg/kg, administered orally q24h) can be administered for 2 to 3 days to alleviate the emesis associated with motion sickness. Recurrent attacks are unusual but may occur on the same side or on the opposite side.

Feline Idiopathic Vestibular Syndrome

Feline idiopathic vestibular syndrome is an acute, nonprogressive disorder similar to the idiopathic geriatric vestibular syndrome that occurs in dogs. It is a common disorder affecting cats of any age. The disease may be more prevalent in the summer and early fall and in certain geographic locations, particularly the northeastern United States, suggesting a possible role for an infectious or parasitic cause. This syndrome is characterized by the peracute onset of peripheral vestibular signs, such as severe loss of balance, disorientation, falling and rolling, a head tilt, and spontaneous nystagmus, with no abnormalities of proprioception or in other cranial nerves. The diagnosis is based on the clinical signs and the absence of ear problems or other disease. If radiographs of the tympanic bullae and petrous temporal bone are obtained, the findings are normal, as are the results of cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) analysis. Spontaneous improvement is usually seen within 2 to 3 days, with a complete return to normal within 2 to 3 weeks.

Neoplasia

Tumors involving the inner and middle ear may damage peripheral vestibular structures and result in peripheral vestibular dysfunction. Tumors can arise from regional soft tissues (e.g., squamous cell carcinoma, adenocarcinoma, lymphoma) or from the osseous bulla (e.g., fibrosarcoma, chondrosarcoma, osteosarcoma). Tumors originating within the external ear canal (e.g., squamous cell carcinoma, ceruminous gland adenocarcinoma) may also invade past the tympanic membrane to involve the middle and inner ear. Less commonly, tumors of CN8 (e.g., neurofibroma or neurofibrosarcoma) result in peripheral vestibular dysfunction.

When tumors are located in the middle and inner ear, facial nerve paralysis or Horner’s syndrome commonly accompanies peripheral vestibular signs. Radiographic evidence of soft-tissue density within the bullae and associated bone lysis suggests tumor. Advanced imaging with CT or MRI provides additional detail and determines whether the tumor has invaded the cranial vault. Diagnosis can be confirmed by biopsy. The invasive nature of tumors in this location makes total resection difficult. Radiotherapy or chemotherapy may be beneficial in some animals (see Chapters 76 and 77).

Nasopharyngeal Polyps

Nasopharyngeal inflammatory polyps originate at the base of the eustachian tube in kittens and young adult cats and grow passively into the nasopharynx, nose, or middle ear. Most affected cats exhibit stertorous breathing or nasal discharge as a result of respiratory obstruction by these polyps, but cats with polyps in the middle and inner ear are presented with peripheral vestibular signs and sometimes Horner’s syndrome and facial nerve paralysis. Otoscopic examination is often normal, although bulging of the tympanic membrane or extension of a polyp into the external ear canal is possible. A diagnosis of nasopharyngeal polyps should be suspected when a young cat is presented with concurrent peripheral vestibular dysfunction and nasopharyngeal obstruction. Skull radiographs reveal soft tissue within the bullae and thickening of the bone but no bone lysis. Surgical removal requires ventral bulla osteotomy, and the prognosis is excellent for cure if all abnormal tissue is removed (see Chapter 15).

Trauma

Trauma to the middle and inner ear will result in peripheral vestibular signs and commonly concurrent Horner’s syndrome and facial nerve paralysis. Facial abrasions, bruises, and fractures may be evident on initial examination. Hemorrhage in the external ear canal may be evident on an otoscopic examination. Radiographs or advanced diagnostic imaging will reveal the extent of the problem. Supportive treatment for head trauma and possible posttraumatic infection should be initiated. Vestibular signs usually resolve with time, whereas facial paralysis and Horner’s syndrome may persist.

Congenital Vestibular Syndromes

Purebred dogs and cats that show peripheral vestibular signs before 3 months of age are likely to have a congenital vestibular disorder. Congenital unilateral peripheral vestibular syndromes have been recognized in the German Shepherd Dog, Doberman Pinscher, Akita, English Cocker Spaniel, Beagle, Smooth Fox Terrier, and Tibetan Terrier as well as in Siamese, Burmese, and Tonkinese cats. Clinical signs may be present at birth or develop during the first few months of life. Head tilt, circling, and ataxia may initially be severe; however, with time, compensation is common, and many affected animals make acceptable pets. The diagnosis is based on the early onset of signs. If ancillary tests such as radiography and CSF analysis are performed, findings are normal. Deafness may accompany the vestibular signs, particularly in the Doberman Pinscher, the Akita, and the Siamese cat.

Aminoglycoside Ototoxicity

Aminoglycoside antibiotics rarely cause degeneration within the vestibular and auditory systems of dogs and cats. This ototoxicity is usually associated with the systemic administration of high doses or the prolonged use of these antibiotics, particularly in animals with impaired renal function. Degeneration within the vestibular system may result in unilateral or bilateral peripheral vestibular signs and loss of hearing. In most cases the vestibular signs resolve if therapy is discontinued immediately, but deafness may persist.

Chemical Ototoxicity

Many drugs and chemicals are potentially toxic to the inner ear. If the integrity of the tympanic membrane is in doubt, topical otic products containing chlorhexidine, dioctyl-sulfo succinate (DOSS), or aminoglycosides should never be used. Warm saline or 2.5% acetic acid solutions should be used for flushing ears. Whenever vestibular dysfunction becomes evident immediately after instilling a substance in an ear canal, the product should be removed and the ear canal flushed with copious quantities of saline. Vestibular signs will usually resolve within a few days or weeks, but deafness may persist.

Hypothyroidism

Vestibular dysfunction has occasionally been reported in association with hypothyroidism in adult dogs. Concurrent facial nerve paralysis may be seen. Other systemic signs of hypothyroidism, such as weight gain, poor haircoat, and lethargy, may or may not be present. Clinicopathologic testing may show abnormalities suggestive of hypothyroidism (e.g., mild anemia, hypercholesterolemia). The diagnosis is established through thyroid function testing (see Chapter 51). The response to replacement thyroid hormone is variable.

BILATERAL PERIPHERAL VESTIBULAR DISEASE

Most animals with bilateral peripheral vestibular disease have no discernible head tilt. Affected animals have a wide-based stance and are ataxic, usually ambulating in a crouched position with a wide side-to-side swinging of the head. Their conscious proprioception (knuckling) is normal. Affected animals have a definite balance problem, and they fall or circle to either side. No spontaneous or positional nystagmus is observed; in most cases normal vestibular eye movements are also lost. Affected animals are deaf if the cochlear portion of CN8 is also involved. When the animal is held suspended by the pelvis and lowered toward the ground, an affected animal may curl its head and neck toward the sternum instead of raising its head and extending the thoracic limbs toward the floor for weight bearing. Differential diagnoses considered in animals with bilateral vestibular disease include an idiopathic or congenital syndrome, trauma, ototoxicity, inner ear infections, and hypothyroidism. The diagnostic workup is the same as that used in dogs and cats with unilateral peripheral vestibular disease.

CENTRAL VESTIBULAR DISEASE

Central vestibular disease is much less common in dogs and cats than peripheral vestibular disease and generally carries a poor prognosis. Central vestibular disease can be caused by any inflammatory, neoplastic, vascular, or traumatic disorders affecting the brainstem (see Box 68-2). In particular, granulomatous meningoencephalitis (dogs), Rocky Mountain spotted fever (dogs), and feline infectious peritonitis (cats) seem to have a predilection for this region of the brain. Dogs and cats with cerebellar infarcts and tumors are commonly presented with paradoxical vestibular signs.

A standard workup for intracranial disease is performed in animals that have central vestibular signs. A complete physical, neurologic, and ophthalmologic examination is essential to look for evidence of disease elsewhere in the body. Clinicopathologic testing and thoracic and abdominal radiography are warranted to search for neoplastic or infectious inflammatory systemic disease. Finally, advanced diagnostic imaging, particularly using MRI, and CSF collection and analysis should be considered. (See Chapter 65 for a more thorough discussion of the diagnostic approach taken in animals with intracranial disease.)

METRONIDAZOLE TOXICITY

Central vestibular signs have been reported in dogs after administration of metronidazole (Flagyl; Pharmacia and Searle). Signs of metronidazole toxicity are most likely to develop when the drug is administered orally at high doses (usually >60 mg/kg/day) for 3 to 14 days. Initial signs include anorexia and vomiting, with rapid progression to ataxia and vertical nystagmus. The ataxia may be very severe, making walking impossible and resulting in a “bucking” gait. Seizures and head tilt occasionally occur. Treatment consists of stopping the medication and providing supportive care. The prognosis is good for recovery, but complete recovery may take 2 weeks. The administration of diazepam (0.5 mg/kg once intravenously and then orally q8h for 3 days) has been shown to dramatically speed recovery. Metronidazole toxicity has also been reported in cats receiving lower doses of metronidazole. Forebrain and cerebellar signs predominate in this species.

ACUTE VESTIBULAR ATTACKS

A peracute onset of loss of balance, nystagmus, and severe ataxia that lasts only minutes is occasionally seen in dogs. Head tilt may be mild or absent. Neurologic examination during an episode is usually most consistent with peripheral disease, with no postural reaction deficits or cranial nerve abnormalities, but a few dogs have had vertical nystagmus, localizing to central vestibular disease. Dogs completely recover within minutes with no residual neurologic abnormalities and no obvious postictal signs. Some affected dogs have gone on to develop brain (especially cerebellar) infarcts, which suggests that these events could be transient ischemic attacks, as reported in humans. Other affected dogs progress to have recognizable epileptic seizures, which suggests that these events could represent seizure activity in some dogs. Intracranial mass lesions have been identified in a few affected dogs. Rarely, dogs have been reported to have intermittent episodic peripheral vestibular dysfunction with early OM-OI. Dogs with a history of acute vestibular attacks should have a careful physical and neurologic examination performed as well as systemic screening tests for inflammatory or neoplastic disease, disorders of coagulation, and hypertension. An otoscopic examination should be performed. Advanced diagnostic imaging (CT, MRI) to evaluate the middle ear and the brain may be warranted.

Chrisman CL, et al. Neurology for the small animal practitioner. Jackson, Wyoming: Teton NewMedia, 2003.

Vestibular system: special proprioception. In: deLahunta A, editor. Veterinary neuroanatomy and clinical neurology. Philadelphia: WB Saunders, 1983.

Evans J, et al. Diazepam as a treatment for metronidazole toxicosis in dogs: a retrospective study of 21 cases. J Vet Intern Med. 2003;17:304.

Munana KR. Head tilt and nystagmus. In: Platt SR, Olby NJ, editors. BSAVA manual of canine and feline neurology. Gloucester: BSAVA, 2004.

Palmiero BS, et al. Evaluation of outcome of otitis media after lavage of the tympanic bulla and long-term antimicrobial drug treatment in dogs: 44 cases (1998-2002). J Am Vet Med Assoc. 2004;225:548.

Schunk KL, et al. Peripheral vestibular syndrome in the dog: a review of 83 cases. J Am Vet Med Assoc. 1983;182:1354.

Sturges BK, et al. Clinical signs, magnetic resonance imaging features, and outcome after surgical and medical treatment of otogenic intracranial infection in 11 cats and 4 dogs. J Vet Intern Med. 2006;20:648.

Thomas WB. Vestibular dysfunction. Vet Clin North Am Small Anim Pract. 2000;30(1):227.

Troxel MT, Drobatz KJ, Vite CH. Signs of neurologic dysfunction in dogs with central versus peripheral vestibular disease. J Am Vet Med Assoc. 2005;227:570.

BOX 68-1

BOX 68-1