chapter 22 Parenting after stroke

After completing this chapter, the reader will be able to accomplish the following:

2. Describe transitional tasks.

3. Have a basic understanding of one-handed baby care task performance.

4. Identify examples of adapted baby care equipment.

5. Apply parent child collaboration to a baby care task.

6. Identify an emotional or cognitive problem that can affect baby care.

7. Appreciate the importance of teamwork between occupational therapists and mental health practitioners in services to parents who have had strokes.

This chapter will discuss caring for an infant or child by those who have had a stroke. The chapter will raise issues that caregivers and prospective caregivers may encounter and will provide options available to them. The focus is mainly on physical caring of infants, but also includes emotional and cognitive issues relevant to parenting children of varied ages. The goal of this chapter is to provide practical advice to occupational therapists, so they can help caregivers find adaptive methods to carry out the tasks of childcare.

Although strokes are most common after the age of 65-years-old, they can occur at any age. For example, women may have a stroke during pregnancy or during the postpartum period. Men or women may have strokes before considering parenthood or when they already have children. Grandparents who have had strokes may want to participate fully in the lives of their grandchildren or may need to act as primary caregivers.

Some people may feel that the task is insurmountable, but experience has indicated that bringing up a child is an achievable goal for many stroke survivors. In fact, working toward this goal can increase confidence, help reintegrate the family, enhance general functioning, and reduce feelings of depression.

Material in the chapter is based primarily on intervention and research with parents with physical or cognitive disabilities and their children at Through the Looking Glass (TLG) in Berkeley, California, since its founding in 1982. TLG is a disability culture and independent living-based organization that has pioneered research, training, resource development, and services for families in which a family member has a disability or medical issue, and is The National Center for Parents with Disabilities and their Families, funded by National Institute on Disability and Rehabilitation Research (NIDRR), U.S. Department of Education. Illustrative examples in this chapter are based on services provided to TLG clients who had strokes and raised babies and children. This research and intervention framework is summarized, as follows, focusing on points that are particularly salient for serving parents who have experienced strokes.

Research on parent/child collaboration

The groundbreaking study of the interaction of mothers with physical disabilities and their babies (funded by the National Easter Seal Research Foundation, 1985 to 1988) documented the reciprocal and natural process of adaptation to disability obstacles as it developed between 10 mothers and their babies.6 Basic care (feeding, bathing, lifting, carrying, dressing/diapering) was videotaped from birth through toddlerhood. These families were not receiving intervention or baby care adaptations. Analysis of videotapes mapped the gradual mutual adaptation process during interaction between parent and infant. Results documented the mothers’ ingenuity in developing their own adaptations, the infants’ early adaptation, and the mothers’ facilitation of the infants’ adaptation.

Based on the natural adaptation process recorded in this study, subsequent intervention was developed that facilitated collaboration between parent and infant during baby care tasks, such as that described in the Adaptive Techniques and Strategies section of this chapter.

Research on baby care adaptive equipment

In the 1990s, TLG conducted three research projects (funded by NIDRR, U.S. Department of Education), specifically focused on developing and evaluating the impact of baby care adaptations for parents with physical disabilities.6,12,14 The equipment development was informed by adaptations invented by mothers in the previous Easter Seal study. For example, in that study, several mothers lifted their babies with one hand by grasping their babies’ clothing. In the subsequent baby care equipment development projects, TLG designed and used lifting harnesses as a more secure version of this natural adaptation. All three equipment studies used analyzed videotapes of care and interaction prior to and subsequent to providing baby care adaptive equipment. Such equipment was found to have a positive effect on parent/baby interaction, in addition to reducing difficulty, pain, and fatigue relating to baby care. The equipment also seemed to prevent secondary disability complications from overstressing the body during care and to help reduce depression associated with postnatal onset or worsening of disability. By increasing the caregiving role of the parent with a disability, stress was lessened in the couple; there was more balance of functioning in the family system.

Visual history

TLG has emphasized the use of videotaping in both research and intervention because of the lack of images of parenting by individuals with physical disabilities, which affects diverse professionals, including occupational therapists, and parents and their family members. The occupational therapy (OT) team coined the term visual history to refer to the mental image most people have of the way a task is accomplished.12 For example, when people imagine holding a baby, they think of a baby in someone’s arms. Such limited visual histories may interfere with the goal of learning to accomplish a task in a new way. Thus, occupational therapists and clients need to be aware of their limited visual history and the need to expand and change it. For instance, holding a baby can be accomplished by attaching an infant car seat to a wheelchair (Fig. 22-1). In order to expand visual history regarding parenting, TLG has developed DVDs showing different techniques of accomplishing baby care tasks, including one-handed techniques often needed in parents who have experienced strokes.

Occupational therapy assessment to guide baby care adaptations

TLG developed an assessment tool to guide occupational practice with parents with disabilities and their babies and toddlers. The assessment provides a framework for understanding the complexity of OT support of caring for a baby when a parent has a physical disability. This assessment tool, The Baby Care Assessment for Parents with Physical Limitations or Disabilities,15 guides the OT practitioner in intervention work and analyzing potential obstacles. It brings together the parent’s perspective and the occupational therapist’s skill in task analysis. This tool provides an extensive review of all baby care functioning within the home and community relative to the parent’s needs and/or wishes. The tool identifies the parent’s strengths and highlights the obstacles that are interfering with his or her ability to complete the task in the least demanding, most efficient, safe, and ergonomic manner and with a method that supports and enhances the parent-child relationship. This assessment tool also has a parent interview section, which helps the occupational therapist find the activities important to the parent. It incorporates the disability philosophy of independent living, i.e., having opportunities to make decisions that affect one’s life and to choose which activities one wants to pursue. It should be noted that the assessment emphasizes visiting in the home and community.

Intervention model

TLG’s research has informed its intervention with thousands of parents with disabilities and their children. The intervention model has been described and rigorously evaluated since the 1980s, demonstrating positive outcomes with particularly stressed families in which parent and/or child has a disability.5,6 The intervention model includes multidisciplinary teamwork emphasizing:

1. Infant/parent and family relationships, integrating infant mental health and family systems expertise

2. Parenting and intervention adaptations to address diverse disability issues

3. Developmental expertise regarding infants and children

4. Integrating and respecting personal/family disability and cultural experience

5. Functioning in the natural environment, through home and community-based assessment, intervention, monitoring, and referrals

A family in which a parent has experienced a stroke is usually served in the home and community by an occupational therapist who assesses and provides baby care adaptations, introduces cognitive adaptations, consults on environmental access, and monitors infant/child development issues and continued safety and appropriateness of the adaptations over time. The occupational therapist works closely with the home visiting mental health practitioner who attends to the emotional issues in parent, child, and family, such as grieving, loss, depression, volatility or impulse control, management of children’s behavior, couple conflict, and changes in family roles and functioning. Both providers facilitate interaction between parents and their infants or children and monitor safety and well-being of the child. Ongoing training and reflective supervision are integral to these services.

Working with pregnant women poststroke

Working with a woman who is trying to decide whether to become pregnant or who is in the first trimester of pregnancy is a challenge for the OT practitioner who has to imagine both how pregnancy may impact the client’s mobility and how her limitations may affect her ability to care for the baby. It is helpful for women to understand that physical difficulties from a stroke need not close off the option to have a child. During pregnancy, mobility generally is affected from the latter part of the second trimester, when the center of gravity has changed, to delivery.10 This change in the center of gravity will most likely affect walking, standing up, and/or transferring in and out of bed, cars, etc. See Chapters 14 and 15. The woman may benefit from a mobility device (walker or wheelchair/scooter). It might be beneficial to consult a physical therapist. If the leg is mildly involved, a rollator (four-wheeled walker) would be a good choice. It could not only make her stable but also could be used for carrying her baby around the house. If the affected leg is very involved, walking can be difficult, and a motorized wheelchair/scooter could be the most appropriate choice. See Chapter 26.

Willingness to accept a motorized vehicle (wheelchair or scooter) can be problematic for the prospective mother. It is important for the future mother to understand that the wheelchair/scooter would make her more comfortable, less likely to fall, and more able to conserve energy and care for the baby after birth. If she tries a motorized piece of equipment for an activity such as shopping, she may realize how easy some activities can be. She may also be concerned about how she will be able to care for the baby. A discussion of the adaptive techniques described in this chapter may ease her mind about solutions to physical limitations. However, a crucial issue in decision-making about parenthood is how the stroke has affected emotional and cognitive functioning.

Facilitating relationships between babies and parents poststroke

Without appropriate supports, a stroke occurring late in pregnancy or postpartum can be devastating to a mother, family, and infant/parent relationship. Since hospitalization creates a separation between mother and child, it is critical to consider the need to promote attachment during the subacute phase of rehabilitation. The occupational therapist should have attachment activities as part of the treatment plan. Attachment activities will change depending on the age of the baby or child. All baby care activities can support the relationship between parent and child. However, if the baby is under 9-months-old, holding, feeding, and soothing are particularly essential activities. If the caregiver has sustained a stroke when his or her child is a toddler, or if the caregiver who had sustained an earlier stroke comes in seeking help, the emphasis is more on supporting and scaffolding interaction between parent and child, for instance during play, snack, snuggle time, and outings, in order to promote the parent and child relationship.

Facilitating physical care by the parent

Being able to provide physical care to the baby is one of the essential elements in parenting. For a caregiver who has had a stroke to pursue the dream of caring for a baby, he or she may need baby care equipment, appropriate durable medical equipment (DME), and adaptive techniques. Transitional tasks refer to tasks that are necessary before accomplishing or between basic baby care tasks. Therefore, it is important to begin intervention with these tasks: (1) holding, (2) carrying and moving, (3) transfers, and (4) positional change.12

Holding: The task of holding is a prerequisite for carrying, transferring, feeding, changing, burping, or comforting your child.

Holding: The task of holding is a prerequisite for carrying, transferring, feeding, changing, burping, or comforting your child.

Carrying and moving: The task of carrying is a prerequisite for moving around the house and community. If a caregiver cannot carry or move the baby, then he or she will be confined to functioning in one room.

Carrying and moving: The task of carrying is a prerequisite for moving around the house and community. If a caregiver cannot carry or move the baby, then he or she will be confined to functioning in one room.

Transfers: The task of transfer is a prerequisite to being able to do several activities such as diapering and putting the baby into a crib or high chair

Transfers: The task of transfer is a prerequisite to being able to do several activities such as diapering and putting the baby into a crib or high chair

Positional change: The task of positional change is a prerequisite for being able to burp a baby or diaper change a baby. A positional change is defined as changing a position of the baby while the baby remains on the same surface.

Positional change: The task of positional change is a prerequisite for being able to burp a baby or diaper change a baby. A positional change is defined as changing a position of the baby while the baby remains on the same surface.

Holding

Holding involves contact with the baby, whether it is directly in the mother’s arms or with the aid of a holding device. It is essential that the parent feel confident that the baby is secure and for the baby to experience this security. Useful positions and holding devices for a parent with limited sitting balance include:

Side lying for both baby and parent

Side lying for both baby and parent

Parent’s bed at 45 degree angle, sitting

Parent’s bed at 45 degree angle, sitting

Sling, nursing pillows, wedge pillow

Sling, nursing pillows, wedge pillow

CASE STUDY 1

Darla had a cerebellar stroke at 8½ months of pregnancy. Immediately following the stroke, her son David was delivered by caesarean section. He was healthy and weighed 6 pounds 10 ounces. His lungs were fully developed, and he did not need hospitalization, so he was discharged at 3-days-old and went home with John, his dad. Darla’s parents moved in to help with David. Darla was in a coma in intensive care unit for several days. As soon as she was transferred to the subacute unit, her family was able to bring David to her. The hospital staff put David in a sling baby carrier. Although David was secured in the sling, Darla feared that he would fall. The hospital staff was unaware that her concern was because of her need for some support when sitting. She had not yet gained sufficient trunk control and increased sitting balance, so holding her baby increased her anxiety. In this situation, the occupational therapist could have checked with Darla and discovered why she felt insecure holding her baby, and then a more appropriate position could have been found. One such position would have been to have her lie on her more affected side with David side lying on her arm, so that they could look at each other and so that Darla could kiss and touch him.

Carrying and moving

TLG has recommended a four-wheeled walker, also known as a rollator, for safely moving the baby around the house. This walker has been used successfully with caregivers with hemiplegia (where half of the body is paralyzed) and with those with ataxia (problems with coordination), because it keeps both baby and parent physically stable. This piece of equipment consists of a baby carrier securely attached to a walker seat. The baby carrier can be a bouncy seat or a booster seat, although the former is more difficult to attach. TLG prefers a feeding seat that can be positioned in several ways, such as reclining for an infant or more upright for the older baby. Moreover, having a baby seat on the walker positions the baby at an optimal height for transfers (Fig. 22-2).

When the walker is introduced depends on the stability of the parent. It has been successfully used during inpatient physical therapy to help prepare the caregiver for going home. However, it is designed to be used only within a household. Extreme caution needs to be used if the adapted walker is moved over any uneven or raised surface since it is top heavy with a baby on it. In consultation with a rehabilitation engineer, adding weights to the lower part of the walker can be considered to compensate for the added weight of the baby. Otherwise, strategies are used by parents with physical disabilities that may be less feasible with parents that also have cognitive difficulties, i.e., putting the back wheels over the raised surface separately, lifting one of the sides of the walker over the raised surface with an arm, or using a leg to nudge one side of the walker at a time. The occupational therapist should carefully assess the safe use of the adapted walker during home visits.

If the parent prefers or needs to use a manual or motorized wheelchair, there are several types of devices for holding the baby.11 The following adaptations are especially easy to use. Using a wedged piece of form as wide as the parent’s lap, 8 inches thick at the parent’s knees, and slanted down to 3 inches thick at the parent’s waist can provide a surface for moving, feeding, and playing with the baby. The wedge should be covered in washable fabric and have a strap attached to go around the parent’s waist, and a strap attached to hold the baby securely on the pillow (Fig. 22-3). Another design that can be used for an older baby with good head control is the double neck pillow, which consists of two neck pillows.

Positional changes

Positional change examples are described in the discussion of burping and diapering in the Adaptive Techniques and Strategies section of the chapter.

Transfers

Lifting an infant who does not yet have head control can pose a challenge for people with limited upper extremity use. The easiest solution is to use a baby carrier sling (see equipment chart). If the baby does not accept the sling, the following technique can be used while a parent is in a sitting position in order to transfer from lap to surface. (1) Choose or arrange surfaces that are high enough to avoid back strain. (2) Place the functional hand under the baby’s head. (3) Bend over and simultaneously pull the baby to caregiver’s chest. The chest acts like another arm to support and hold the baby. (4) Straighten up and move the baby. A caregiver can wear a fanny pack stuffed full of soft material that can provide additional support for the baby’s bottom (Fig. 22-4). It is crucial to assess whether a parent can move in a balanced and secure way from a sit to a standing position holding the baby in this manner.

Caregivers have been successful using a lifting harness to transfer the baby from one surface to another. Note that the lifting harness cannot be used until the baby has head control, so prior to this period parents should use an infant carrier sling. A good template for making a harness is using a baby vest on the market (www. babybair.com) with added straps using one inch webbing (Fig. 22-5). Lifting a toddler with a harness can produce repetitive stress injury, because of the added weight. Therefore, toddlers should be taught to climb onto the desired surface using parent-child collaboration techniques. If the surface is too high, TLG has found steps with short risers, making them easier for toddlers to climb.

CASE STUDY 2

Michael, an older father and the primary caregiver of his son, had a stroke affecting his left hemisphere shortly after his son Sam’s birth. His wife Karen worked full time. His right arm was more involved than his leg. When Sam was 1-year-old, he was in the 70% percentile in height and weight. Michael was still successful using the lifting harness to transfer Sam. Michael wanted to continue using it even though he was experiencing considerable pain in his left shoulder. An occupational therapist from TLG showed him the adaptive technique of giving Sam a boost up to a higher surface by reaching between his legs from behind Sam’s back. This approach provided enough advantage for Sam to climb up and importantly reduced the use of Michael’s shoulder muscles and lessened his pain. The occupational therapist’s developmental background helped her know when to introduce Sam to climbing that would help with care. She brought steps, so Sam could climb into the high chair.

Providing adaptive baby care equipment

Appropriate equipment can make caring for a child possible for a person who has had a stroke. Some equipment is essential for use in conjunction with certain techniques, while other items simply make the tasks easier or may be crucial to care.

Bedtime

TLG gets more calls about issues with bedtime than any other topic. For most clients, the greatest difficulty occurs in the course of the transfer activity of putting the baby in bed. The parent can often enjoy the ritual of dressing his or her child in night clothes, reading a book, cuddling, and perhaps singing a song, but since most cribs are inaccessible, the soothing bedtime activities feel incomplete, resulting in frustration for parent and child alike.

Some commercially available infant beds allow the child to sleep with the parent, but these have flaws. The Co-Sleeper, which attaches to the adult bed, poses problems for parents with disabilities, since it can make it difficult to get out of bed. The parent must slide to the foot of the bed to get out. Another make, the Snuggle Nest, lasts only a few months because only the youngest infants fit into them.

Commercially available cribs can be adapted to meet the needs of parents with physical disabilities, but the occupational therapist must be careful to consider safety in choosing an adaptation. TLG does not recommend cribs with gate openings because the baby can roll out when the parent backs away in order to open the side. TLG recommends use of a sliding door design, so that the parent can block the entrance with her body as the door slides to the side. When using a sliding door, one needs to install a lock that is workable for the parent but not for the child. TLG has used a two-step lock, but this could be difficult for a parent who has apraxia or sequencing issues. TLG does not recommend using a top bar to stabilize the sliding door because babies can hit their heads coming out, especially if the baby is already crying and upset. Adaptations of commercially available cribs cause problems to structural integrity; therefore, adapted cribs need to be frequently checked to assure safety (Fig. 22-6).

Childproofing

Home visiting is essential to address childproofing. Some childproofing can be adult proofing, since devices may be too complicated for a parent because of cognitive and physical difficulty. It is necessary to try several types of devices to see which one is successful. The process will be an opportunity to assess visual and visual neglect issues, apraxia, sequencing, and motor planning. See Chapters 16 to 18. It should be noted that access without raised thresholds for walkers and wheelchair access needs to be considered when using safety gates.

Diapering equipment

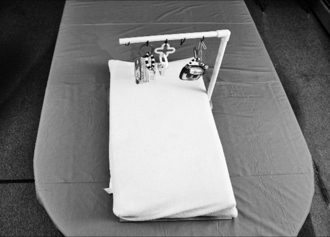

Following a stroke, some parents find it more comfortable to sit when diapering, while others still prefer to stand. For those who prefer to sit, there are several options using computer tables. Computer tables come in different sizes, shapes, and costs. For families who may not have space for another table and need to conserve space in their house, a dining room table works well. If a table is used for another activity, it is important to have a diapering surface that can be removed from the table. Whether the parent sits or stands, it is very helpful to use a toy mobile that uses interactive toys to keep the baby occupied during the diapering process. Using a concave diapering pad and a safety strap is essential to prevent the baby from rolling off a desk or table. If the pad is put on a table, it may slip around. If the pad is attached to plywood, the pad will be prevented from slipping around, and a toy mobile can be used.

To make this piece of equipment, use a piece of plywood 1½″ wider than the concave diapering pad, and cover the bottom of the wood with nonslip shelving material. A threaded phalange is added to the plywood, so PVC piping for the mobile can be attached to the plywood. Drilling holes into the polyvinyl chloride (PVC) piping and fastening an electrical cord affixes interactive toys, such as squeaky animals or plastic books (Fig. 22-7).

Examples of equipment on the market

Prior to customizing or developing new baby care adaptations, the occupational therapist should explore the changing options of commercially available equipment that can support baby care by a parent who has experienced a stroke (Table 22-1).

Table 22-1 Commercially Available Baby Care Equipment

| ACTIVITY OR TASK | COMMERCIALLY AVAILABLE EQUIPMENT |

|---|---|

| Bed time Cosleeper (attached to the parent’s bed) | Arms Reach cosleeper (can make it difficult for the caregiver to get out of bed) |

| Cosleep in parent’s bed | Snuggle Nest |

| Diapering | |

| Dressing | |

| Holding equipment | |

| Breastfeeding | |

| Bottle feeding | Bottle holders |

| Burping | Lifting harness adapted from (Babybair) vest |

| Carrying and moving for a parent who has hemiplegia/paresis and/or ataxia | Four-wheeled walker (Rollator) with seat attached |

| Wheelchair user (motorized) with use of one hand | Sling (see previously) |

| Transfers | Lifting harness adapted from (Babybair) vest |

| Going out into the community |

Durable medical equipment

In addition to baby care equipment, the caregiver may need assistive mobility technology, such as a power wheelchair, scooter, or four-wheeled walker. Transporting the baby safely can increase the need for this equipment. DME can be an issue to a caregiver within the household or if he or she cannot keep up with the family out in the community. Unfortunately, the caregiver may face difficulties acquiring appropriate mobility equipment, as there may be no coverage if he or she can walk within the household or inadequate coverage of costs (such as for a motorized wheelchair).

Adaptive techniques and strategies

These techniques were devised for the caregiver who has the use, or partial use, of one arm.16 Many of these techniques also emphasize baby collaboration with the parent. During inpatient rehabilitation services, the OT clinician can introduce baby care techniques. It is important to include baby care tasks in the treatment plan. For example, some of the patient’s own activities can serve two purposes. As the caregiver learns how to dress herself, he or she can also learn how to dress the baby. This can motivate the parent and help reduce depression.

Feeding: combining adaptive baby care equipment and techniques

Feeding is one of the most important aspects of care in the formation and maintenance of a parent/child relationship.

Breastfeeding.

Being able to breastfeed can be important for the relationship between mother and baby and can give the mother self-confidence and hope that she can continue her role as mom. If the mother’s stroke was due to high blood pressure, she may need blood pressure medication and/or blood thinners, which could affect breast milk and therefore breastfeeding. Prior to breastfeeding, it is important to consult with physicians regarding possible harm to the baby from medications being used. An additional source of this information is the Organization of Teratology Information Specialists at (866) 626-6847.

If the mother breastfed prior to hospitalization and she would like to continue breastfeeding during hospitalization, it will require the availability of the family or other support people, so the baby can breastfeed regularly. If she wants to breastfeed but is unable to see the baby often enough, a breast pump can be used to express milk until she reunites with her baby. The breast milk can help her feel connected with her baby and feel that she is the source of the best possible nourishment. A useful bra for pumping is one that contains the pump, so it is hands-free (Easy Expression). In addition, the bra exposes the areola, making it easier for the baby to latch on since the breast tissue is held back and hand use is not needed. A “breast shield” or “breast shell,” also used for flat or inverted nipples, can also be used to hold the areola back.

Finding a good position to feed the baby is critical. To hold and feed the baby on the nonaffected side can be emotionally disconcerting, because the mother cannot use her functional arm. Therefore, it is usually best to position the baby on a pillow rather than the nonaffected arm. It is important to try various breastfeeding pillows on the market to see what works best, and it is best to use a pillow with a waist strap, so it will be secured on the mother’s lap.

Bottle feeding.

Sometimes the new mother may decide to bottle feed, which can be a good choice and should be respected. Bottle feeding is another task that promotes the parent/child relationship, but holding a bottle can be difficult. A bottle holder can eliminate the frustration a parent may experience when trying to hold both the baby and bottle steady. Bottle holders can be found on the Internet. Important problems relating to formula preparation are dealt with in the Cognitive Issues section.

Burping

Whether breastfeeding or bottle feeding, most people with the use of one functional arm need a technique to help the infant burp. Typically, visual history involves a picture of burping a baby over the shoulder. For many parents with a disability, burping over the shoulder can be difficult or impossible, as it requires both coordination and the use of two arms. However, there are other equally effective techniques, and learning them can increase the caregiver’s sense of confidence and independence. One of the successful techniques developed by TLG is called the sit and lean. This is an example of a positional change, a transitional task discussed earlier. Using this method, the caregiver holds the baby on his or her lap facing away from the body. Supporting the baby by placing one arm across the baby’s chest, the caregiver then leans forward. This puts gentle pressure on the baby’s stomach and facilitates a burp.16

Another technique is to lay the baby prone (face down) on the caregiver’s lap and pat the baby’s back.10 Alternatively, the caregiver can lay the baby on the right side, rolled slightly towards the stomach and rub on the back.

A third technique begins with lifting the baby’s legs up before putting the baby into a sit, with the parent then putting his or her hand under the baby’s bottom and bouncing upwards.

Diapering

In diapering a child, application of the parent-child collaborative technique is essential. Most babies can be “trained” to do the “bottoms up” technique. Parents can teach their baby to lift his or her bottom by lifting the baby’s bottom with the working arm and saying, “Up, up” simultaneously. With time, many babies will then lift their bottoms when cued with the words “up, up or butt up.” With infants who are premature or still mostly in the flexed position, the caregiver can rest the baby’s bottom on the caregiver’s functional palm and lift the child onto the diaper.

Fastening the diaper.

After the caregiver places the diaper under the baby and brings the diaper through the legs, the front of the caregiver’s wrist should rest on the baby’s pelvis in order to secure the diaper. The thumb and one to two fingers grab the tab or corner, and then the remaining fingers of the same hand walk the tab over to fasten it down. On the other side of the diaper, some of the fingers hold the diaper tab or corner, while the remaining fingers and palm hold the diaper steady to fasten the tab

Nighttime.

Many parents find it more difficult to be coordinated in the middle of the night. One mother devised a method to help her overcome this problem. She put two diapers on her baby at bedtime. The only thing she had to do in the middle of the night was to pull the interior diaper out and then refasten the remaining one.

Position.

Parents have varied preferences for their positions during diapering. Some caregivers prefer to have their functional arm closer to the baby’s feet, while others prefer to have their functional arm closer to the baby’s head, and still others prefer to face the baby’s feet. Therefore, it is important for the caregiver to try each of those positions to find the most comfortable one.

Undressing and dressing

Birth to 3-years-old.

Dressing is one of the most difficult baby care activities to do one-handed. Many times parents with disability think that they should dress the baby as most people do, on the diapering surface. However, having a baby on the diapering table is generally harder for a parent who has the use of just one hand because they don’t have enough advantage and control at such a distance from their body. The following techniques can help the caregiver make this task less difficult. In all cases, it is helpful if the clothing is a little too large, since it will come on and off more easily.

Dressing a younger baby.

It is important to position the infant as close to one’s body as possible, since it gives the best advantage. Using a nursing pillow such as the Hugster or Boppy will place the infant in a good position on the caregiver’s lap and make maneuvering clothes over the baby’s head easier. Easy open fasteners will facilitate dressing and undressing the baby. Snaps can be difficult to undo with one hand. Velcro closures and zippers are good substitutes for snaps.

Undressing a younger baby.

After the clothing is unfastened, the parent begins with the sleeves, even if the baby is dressed in a one-piece garment. First, the hem of the sleeve needs to be pulled away from the baby with a slight shaking of the clothing, which will encourage the baby to flex a limb to withdraw it from the sleeve. The parent may need to ensure that the garment is not stuck on the elbow by pulling it around the joint. Once the elbow is out, the rest of the arm and hand should follow easily. This process should be repeated with the other arm. To remove a shirt, the front of the garment should be grasped and scrunched together from the neckline to the lower hem. Then it can be pulled away from the baby’s face and lifted over the head from the front.

For dressing an infant in a “onesie” (a shirt that is prevented from riding up due to a closure between the legs) or shirt, the garment can be put on the top of the head as the baby lies on the nursing pillow. The front of the garment can be scrunched together from top to bottom and pulled over the back of the infant’s head. The baby’s head is held between the parent’s forearm and chest. The front of the garment is scrunched up in the parent’s hand, pulled away from the baby’s face, and pulled down. Then the back of the baby’s garment can be pulled down and the infant’s arms pulled into the sleeves.

If the garment has a zipper, it does not matter if the arms or legs are put in first, though many parents prefer to put the arms in first and then the legs before fastening the zipper.

Dressing an older baby.

When the baby is too large to fit on the caregiver’s lap, it is helpful to place the baby near the parent such as on a bed and to use a nursing pillow for support. As with infants, it is important to find garments that have easy fasteners. To put a baby into a one-piece garment, first the fasteners should be undone and the item laid on the dressing surface near the parent. Next the baby is placed on top of the one-piece, the legs are put in first, and then the arm is directed into the sleeve. By pushing slightly on the elbow, the baby will be encouraged to extend his or her arm fully into the sleeve. These steps need to be repeated with the other sleeve and with the pant leg, encouraging the knees to extend.

Undressing an older baby.

Removing a one-piece garment can be accomplished by using the following technique: After unzipping, pull the opening of the one- piece garment toward a shoulder. Pull the garment off the baby’s shoulder. Then pull down from the hem of the sleeve to encourage the baby to withdraw the arm, and shake the clothing to encourage the baby to remove the arm entirely from the clothing. To remove the legs from the one-piece suit, the parent will pull the foot part of the clothing or pant legs away from the baby. If the baby has been encouraged with “butt up,” the baby can help with lifting his or her butt and legs up while the pant legs are pulled off.

Socks.

Putting on a baby sock is easier for the caregiver than putting on his or her own socks. The caregiver grabs one side of the sock of the open end and catches the baby’s big toe with the other side. After the sock is on the big toe, the caregiver pulls the rest of the sock onto the rest of the toes and continues to pull the sock onto the foot. The caregiver then grabs the sock from the underside and pulls the sock over the heel.

Dressing and undressing a toddler.

This age is one of the most demanding, because the children try to assert their independence and therefore are less cooperative. Once the baby crawls and walks, the bed may not be a workable surface. Because the bed affords the child with plenty of room to attempt an escape, the couch is a better choice as it is more contained.

Putting on the shirt or one-piece garment is easier if the toddler is on the parent’s lap. Having a strong collaboration between toddler and parent will help greatly in this process. As with the infant and baby, it is helpful to use a larger size shirt with a large opening at the neck.

Car seats

Latching safety straps of car seats is essential, but fastening them can be difficult even for people with two hands. It is important for the caregiver to experiment with a variety of brands in order to find the easiest to use. The chest strap must be narrow enough to be grasped and closed with one hand. Engaging the straps is easier if the crotch strap is short and stable, so that it does not wobble. Caregivers will find it easier to sit with the affected arm next to the car seat and to use the functional arm across his or her own midline to provide more strength and advantage.

Placing children in car seats

Infants

1. Place the infant car seat in the middle of the back seat.

2. Sit with the functional arm next to the car seat.

3. Cradle the baby in the elbow of the functional arm.

4. Lean across the car to position the baby correctly in the car seat. While leaning, the upper arm will support the baby’s head.

Once the infant can be lifted with a harness, the caregiver should sit in the back seat with the affected side next to the car seat to make it easier to latch the safety straps.

Crawling babies.

The caregiver sits in the back seat, with the affected side next to the car seat and the baby on the lap. With practice, babies can learn to crawl into the car seat. The therapist or another adult can help during the learning process.

Toddlers.

It is too hard to lift a toddler into the car and car seat. Instead, the caregiver should have the toddler climb into the car seat. If the seat is too high for the toddler to climb up into, a step-stool can be placed on the floor. To protect the caregiver’s back, he or she should sit on the back seat while attaching the straps.

Cognitive issues

Cognitive impairment is present in the majority of patients with stroke, so it is crucial to identify any impairment and assess the impact on parenting.3 The caregiver may lose many aspects of cognitive functioning: the ability to speak, read, or follow directions (completely or partially), and other impairments may occur. See Chapters 16 to 20. Cognitive assessment can pinpoint the cognitive difficulties and strengths, so that interventions can be developed to compensate for parenting difficulties. The occupational therapist must determine which specific parenting tasks may be problematic and which impairments lead to these difficulties. TLG currently has a project developing parenting adaptive strategies in relation to cognitive impairments, such as those identified in the cognitive assessment. For example, if the parent has hemianopsia or visual neglect, it can affect keeping track of a moving baby. Attaching bells in the baby’s clothing and/or shoes securely, or buying shoes with built-in squeakers (search the Internet for squeaky shoes for children) could help. If the parent has figure-ground problems that affect distinguishing between the diaper and diaper pad, a dark cover for the diapering surface, visually contrasting with a diaper, could help. The parent may have trouble making formula because of difficulty with following directions, sequencing, or motor planning/apraxia. Infants can develop failure to thrive or seizures from improperly diluted formula, so it is crucial to monitor this area of the parent’s functioning and the infant’s weight gain. An occupational therapist can work closely with the other home visitors, public health nurse, pediatrician, and family to accomplish this. When the parent has problems making formula and qualifies for the Women, Infant, Children (WIC) program, federal regulations of WIC support the provision of premixed formula.

Some cognitive difficulties are much more challenging during parenting, of course, such as difficulties with attention, multitasking, and judgment. When parents have these problems, the use of adaptive equipment and techniques can be more complex. The process needs to be more closely monitored during home visiting by occupational therapists working as a team with mental health, other home visitors, and family members.

CASE STUDY 3

Bob had a stroke during his wife’s pregnancy. Bob became the primary caregiver, while his wife Carol became the bread winner. Bob had a great deal of difficulty caring for Jerry when Jerry cried for longer than two minutes. If Jerry did not want a bottle, Bob did not know what to do. Bob became overwhelmed and perseverated on only giving the bottle. TLG offered a mental health clinician, but the offer was declined. The occupational therapist tried varied strategies, such as relaxation techniques, which were not successful. She tried having Bob take Jerry outside more frequently in order to create a new pattern. Since Bob could read, she introduced a picture of a crying baby with captions of “try diaper changing, try putting baby to sleep, try going outside.” Because Bob’s impairment was significant and the occupational therapist’s interventions were only partially successful, an outside caregiver was recommended and brought in to help for part of the day. Additional strategies would have been possible with support from cognitive therapy and mental health specialists. In retrospect, it might have been helpful to use a tape of the baby crying with repeated practice of calming the baby and putting the baby in the crib; if these were unsuccessful, then the practice of options that calmed the father (e.g., music) might have helped. A list of calming strategies for the father might have been tried. However, when progress is slow or uncertain to succeed, the priority is the welfare of the baby, and community supports may be crucial to support the family.

Emotional issues

When parents have significant difficulties with communication, both cognitively and emotionally, there can be a profound effect on parenting, and teamwork between occupational therapists and mental health practitioners is crucial. However, it is important to keep in mind that all parents need support; all parenting is interdependent. Many people now live away from their immediate family, which can be stressful for both parent and partner. If a partner who has been providing assistance goes back to work, it is important that the parent who has had a stroke has enough support or is safe and confident to care for the baby by himself or herself. A social worker/therapist can help assess the situation, support the family in adjusting to new roles, provide referrals of community resources, and help integrate outside support into the family system. Otherwise the role of a spouse can be so focused on care that the couple relationship suffers, or an older child can be inappropriately used as a caregiver.

CASE STUDY 4

Janice, a mother with school-age children, had a new baby. A month after the birth, she had a stroke and had left hemiplegia as a result. Janice was discharged from the hospital following basic rehabilitation without any information on how to care for her baby Lois. Her husband had to work full-time at this point. Janice felt her only alternative was to keep her older daughter Sandy home from school to do baby care. When the home visits began, both an occupational therapist and a mental health clinician went in as a team due to the level of the mother’s anxiety about her ability to provide care with a disability. As an experienced mother, she had a strong “visual history” of care as a nondisabled mother. The occupational therapist gave Janice baby care equipment (rollator with baby seat) and taught one-handed baby care techniques so she could care for her baby without support. Since her cognitive problems were minimal, she absorbed information readily. Almost immediately, Janice was able to independently care for her child, and her daughter Sandy went back to school. The mental health clinician was able to ease Janice’s anxiety and facilitate the relationships between mother, infant, and older child.

Care by others

Other stroke survivors may receive help from their in-laws or their own parents. Grandparents may be concerned about both their own child and the new baby, and want to decrease the stress on everyone. When grandparents live nearby, they may step in with good intentions but may not give the new parent sufficient opportunity to learn how to take care of the baby. The insufficient contact between parent and baby can impede the attachment and adaptation process, and intensify depression and grieving in the parent. When this happens, the occupational therapist may need to bring in a mental health consultant to help with family dynamics.4 In addition, grandparents should be included in OT sessions, so the grandparents can observe how well the parent is doing.

When the parent uses a personal assistant or attendant, it is also important that the parent interact with the baby sufficiently to develop and maintain the parent/child relationship. Even during an assistant’s care, the parent can participate and hold the baby’s attention (e.g., by talking or touching), and can appear more psychologically central to the baby by verbally directing the care.2

Mental health professionals’ involvement can help identify and address the common psychological difficulties associated with stroke, including anxiety, depression, and grief. Problems of frustration, reduced emotional control, and anger especially call for mental health assessment and intervention regarding their impact on parenting. Experiencing cognitive impairment or aphasia can be associated with or can deepen the depression. The long-term negative impact of maternal depression on infants and the crucial role of early mental health intervention have been well-established.7,9

TLG has found that limit-setting or behavior management is often challenging for parents with cognitive disabilities, partially due to difficulties with consistency. When parents who have had strokes have emotional control or anger management in addition to communication and physical difficulties, it is important that occupational therapists and mental health providers work collaboratively in this difficult yet essential area of parenting.

Discipline from crawling through toddling

In order for caregivers who have had a stroke to discipline successfully, it is important to teach parent and child to collaborate. Parent/child collaboration helps facilitate development of the baby and creates a special bond. To restore and maintain the parent/child relationship it is crucial to support enjoyable interaction between them, e.g., identifying roles and play where the parent can be effective, offering adaptations to support positive mutual experiences. Children tend to be more collaborative and act out less when they have fun with the parent and see them in effective roles.

To understand how to discipline with a physical disability, it is important to change the “visual history” people have about discipline. For instance, with a cruising baby, the best practice is for the occupational therapist to help the parent learn to entice the baby to come to him or her. A crawling baby is hard to pick up in the middle of a room when the parent is standing up. This can put the parent at risk for secondary injury (back injury and/or shoulder pain) and falling. Developmentally, toddlers enjoy and learn from the game of chase. Typically, they love to run away from their parents. For a parent with physical disabilities, it is essential to teach the toddler to chase the parent.

CASE STUDY 5

Alicia had a stroke and returned home when her child, Ramon, was one and just learning to walk. The occupational therapist taught Alicia to entice Ramon to come to her. Having an arsenal of enticing items, such as a bottle, toy cell phone, car, etc., is essential to engage the baby and make the baby want to crawl over to the parent. Since Ramon liked to crumple paper and chew on it, he was shown a piece of paper, which was shaken to make noise; he was told, “Look, look at the paper!” Once Ramon came over to get his paper, Alicia was able to lift him onto the couch where she was sitting by using a one-handed technique, bringing her hand down Ramon’s back and lifting him up from under his crotch. Alicia said, “The technique helped reduce my anxiety by knowing that my baby will come to me. The worry that he might get into trouble was making me tense, and this technique gave me the feeling that I was in control.” The mental health clinician also addressed Alicia’s anxiety, anger, and depression, which could have created more obstacles in the parent/child relationship.

Temper tantrums

When a toddler throws a temper tantrum, it is usually impossible to have the child go to the parent, but there are other techniques. Most parents with a stroke cannot pick up kicking and screaming children and take them to their room. However, the belief that taking a misbehaving child to his or her room is the only appropriate response is due to visual history preventing caregivers from seeing alternative approaches. It is important to remember that the point of the separation is separation. Having the parent leave the room is equally effective. It is, of course, important to have rooms child-proofed and ensure that the child will be safe when left alone.

Transition navigating social obstacles integral to parenting

Getting out in the community

Going out in the community is a typical family activity, but can pose problems for a caregiver with a disability.

Transportation

In a national survey and in national and regional task force reports, parents with disabilities have reported that the availability of transportation had more of an impact on being able to parent with a disability than any other issue.8,13 Since many people who have experienced a stroke can no longer drive, they are often left relying on paratransit services for individuals with disabilities. Unfortunately, there are many problems involved in using this service, especially for parents with disabilities transporting their children. One such difficulty is that paratransit does not provide car seats for children. This becomes especially problematic when the child requires a car seat for children from 20 to 60 pounds, given the bulk of such carriers. Parents using paratransit are therefore forced to lug bulky car seats around with them during the day, which is impossible for many parents with physical disabilities. See Chapter 23.

Recreation

Being able to take child to a playground is a common outing for parents; however, recreation is an area fraught with problems for parents with physical and/or cognitive disabilities. The task force reports and national survey of parents with disabilities have identified access problems during recreation: “Public recreational sites such as playgrounds and parks are either inaccessible altogether or only accessible for young children with disabilities—rarely for a parent/adult with a disability.”8 Parents also reported needing assistance in recreation with their children. Parents with attention problems or difficulties with the authority required to manage behavior in public places may need mental health services to facilitate interaction and possibly an ongoing adult companion during outings. When a parent with a physical and/or cognitive disability goes out in the community with a toddler, it is important to have a walking harness. One good type of harness is a backpack with a tether. The harness can prevent the toddler from running away, but will not stop the screaming of a toddler having a tantrum. One good technique for the parent to try during the tantrum is making a call on a cell phone as a diversion technique, taking advantage of the desire of toddlers and preschoolers to engage with or talk with parents whenever they get on the phone.

Parenting older children

Since a stroke can occur at any time, it can happen when a parent has school-age children. If a parent has had a stroke prior to birth, the parent’s disability is integral to the child’s experience of the parent. For an older child whose parent has a stroke, the changes in the parent are typically experienced as loss of the parent as the child has known him or her, and grieving about this loss can take the form of depression or acting out. Providing continuity in contacts between parent and child, including during hospitalization, can be helpful, so that loss is less complicated by separation. Older children are often acutely aware of social stigma directed toward the parent, and teasing and embarrassment about differences may be issues. Parent and child can strategize together about responses to teasing. One parent taught her child to answer “So what?!” and this was successful in ending the hostile comments. Some parents have found that ongoing participation in the classroom helped. Communication with older children about the social prejudice and barriers can raise their consciousness about social justice issues (e.g., transportation obstacles can make it difficult for the older child to participate in organized sports and other events when there is not another available adult or adequate paratransit services). The role of mental health practitioners is heightened for the child and for the parent, since depression is so problematical during parenting.

Occupational therapists have a crucial role in facilitating functioning, so the child and parent can navigate new obstacles and enjoy interaction and play. If the caregiver has lost the ability to read, being able to use computer software or other devices that can read books is an alternative. There are options of software on all subjects that can help the caregiver be present while the child learns a skill and does homework. When there is no parent or family member who can assist with homework, TLG also recommends tutoring for school-age children, ideally including or coordinated with respectful services to the parent providing assistance (e.g., in structuring time and place to complete homework). Some family recreation choices may have become too difficult (e.g., hiking, beachcombing). However, there are outdoor activities that have been adapted for people who are disabled (e.g., skiing, bicycling, sailing, horseback riding) that the family can join.

CASE STUDY 6

Jim and Mary had two older children in junior high and high school when a surprise pregnancy occurred. Soon after Sharon was born, Jim had a left hemisphere stroke resulting in aphasia and right hemiplegia. Jim was not the only one in the family who had depression; his wife and older children also did. They felt they had lost their father/husband who had had a great sense of humor and enjoyed the outdoors. A TLG family mental health clinician and the occupational therapist helped the family change how they looked at their recreational activities. The mental health clinician and occupational therapist worked together to help the family adjust to new activities that were fun for them, such as playing card games or board games. TLG was able to help them join another disability community program that provided outdoor activities. The family started doing adapted bike trips every month.

Although there can be pitfalls for parents who have had strokes, there are also many beautiful success stories. TLG has funded scholarships for high school seniors or college students whose parents have disabilities. One of the 2009 national winners has a father who experienced a stroke. He wrote:1

The Impact of Growing Up with a Parent with a Disability

Some people will look at him and see weakness, but I look at him and see nothing but strength and fortitude. Some people may look at him and see a man who cannot get his words out as well as he wants too, but I look at him and see a man who speaks volumes to me. Some people may look at him and see a man whose hand doesn’t work quite right, but I look at him and see a man who gives hugs and handshakes as strong and comforting as they ever were. Some people may look at him and see a man who walks with a limp on his right side, but I see a man who hopped to first base at our father-son baseball game, unashamed of his deficits and the obstacles that lay before him, because he just wants to be there for me, his son.

My father suffered a major stroke in 2004, and many of the effects of that stroke are still with him today . . . Witnessing his strength and tenacity has taught me to be strong just like he is. He has also taught me the value of family, and that it is the best thing you can have in life. Lastly, but probably the greatest thing he ever taught me is to always work hard toward your dreams and never give up hope . . . Not a day goes by where my father doesn’t work hard to get back to normal. He is unable to work as a cabinetmaker and can’t use his right hand or speak clearly. He may not know it now, but he has helped me so much to become stronger, just by watching how hard he worked. Living with a disabled parent has made me stronger when I am faced with harsh conditions and has taught me to always work hard to get where I need to be . . . . . Since I could walk, the only thing I have wanted to do in life is play baseball, and I hope to play professionally one day . . . I figured out that I had to work hard to achieve my dreams. I remembered my dad and how he struggled with physical therapy every day until he was sweating and crying, and I started lifting weights at school, stayed after practice an hour longer than the other players, [and] got extra help from my coach and other instructors, so I could be a better player. I feel so blessed that my dad taught me this lesson of working hard to “get better” because I have now been recruited by several colleges to play on their baseball teams . . .

Seeing my dad have the stroke has done nothing but add fuel to my fire to get to where I want to be. My dad has not missed a game since he got out of the hospital, and he still does his best to teach me how to play the game . . . I only hope that when I am older that I can be half the man my father is. You see, I consider myself lucky to be living with the man who can’t get the words out all the time, whose right hand doesn’t work quite right, and who walks with a limp, because the alternative is something that I don’t want to think about. I live with the man who suffered a severe stroke in 2004, but since then has taught me enough lessons to last me multiple lifetimes.

TLG has assisted many parents who have had strokes to find ways to navigate and enjoy the caregiving experience. Teamwork between occupational therapists and mental health practitioners can increase the parent’s role and effectiveness, address obstacles, support the relationship between parent and child, and assist the functioning of the entire family system.

Review questions

1. Describe techniques that would be useful in helping a parent with hemiplegia burp a child independently.

2. Name the four transitional tasks to master as the starting point of intervention.

3. What is an appropriate diapering technique to teach a parent with hemiplegia?

4. What are the steps to teaching dressing and undressing a younger baby? An older baby?

5. What is the correct sequence of placing an infant in a car seat for a parent who has unilateral upper extremity impairment?

1. Anonymous. Through the Looking Glass Scholarship Recipient. Unpublished essay. 2009.

2. Groah SL, editor. Managing spinal cord injury. A guide to living well with spinal cord injury. Washington, DC: NRH Press. 2005.

3. Hoffman M, Schmitt F, Bromley E. Comprehensive cognitive neurological assessment in stroke. Acta Neurol Scand. 2009;119(3):162-171.

4. Kirshbaum M. Disabilities in the family. Babycare assistive technology for parents with physical disabilitiesRelational, systems, & cultural perspectives. AFTA Newsletter;1997;Spring:20-26.

5. Kirshbaum M. A disability culture perspective on early intervention with parents with physical or cognitive disabilities and their babies. Infants Young Child. 2005;13(3):9-20.

6. Kirshbaum M, Olkin R. Parents with physical, systemic, or visual disabilities. Sex Disabil. 2002;20(1):65-80.

7. Lyons-Ruth K, Zoll D, Connell D, Grunebaum HU. The depressed mother and her one-year-old infant. Environment, interaction, attachment, and infant development. New Dir Child Dev. 1986;34:61-82.

8. Preston P. Visible, diverse and united. A report of the Bay Area parents with disabilities and deaf parents task force meeting. Berkeley: Through the Looking Glass. 2006.

9. Parkes CM, Stevenson-Hinde J, Radke-Yarrow M. Attachment patterns in children of depressed mothers. In: Attachment across the life cycle. New York: Tavistock/Routledge; 1991.

10. Rogers J. Disabled woman’s guide to pregnancy and birth. New York: Demos Medical Publishing; 2006.

11. Through the Looking Glass. Adaptive parenting equipment: Idea book 1. Berkeley: Through the Looking Glass. 1995. (NIDRR Grant No. H133G10146)

12. Through the Looking Glass. Developing adaptive equipment and techniques for physically disabled parents and their babies within the context of psycho-social services, Final Report. Berkeley: Through the Looking Glass. 1995. (NIDRR Grant No. H133G10146)

13. Toms Barker LT, Maralani V. Challenges and strategies of disabled parents. Findings from a national survey of parents with disabilities, Final Report. Berkeley: Through the Looking Glass. 1997. (NIDRR, Rehabilitation Research and Training Grant No. H133B30076)

14. Tuleja C, Rogers J, Vensand K, et al. Continuation of adaptive parenting equipment development. Berkeley: Through the Looking Glass; 1998.

15. Tuleja C, Rogers J, Kirshbaum M, et al. Baby care assessment for parents with physical limitations or disabilities. An occupational therapy evaluation. Berkeley: Through the Looking Glass. 2005.

16. Vensand K, Rogers J, Tuleja C, et al. Adaptive baby care equipment. Guidelines, prototypes & resources. Berkeley: Through the Looking Glass. 2000.