Chapter 14 Oral Cavity and Gastrointestinal Tract

See Targeted Therapy available online at studentconsult.com

The gastrointestinal tract is a hollow tube consisting of the esophagus, stomach, small intestine, colon, rectum, and anus. Each region has unique, complementary, and highly integrated functions that together serve to regulate the intake, processing, and absorption of ingested nutrients and the disposal of waste products. The intestines also are the principal site at which the immune system interfaces with a diverse array of antigens present in food and gut microbes. Thus, it is not surprising that the small intestine and colon frequently are involved by infectious and inflammatory processes. Finally, the colon is the most common site of gastrointestinal neoplasia in Western populations. In this chapter we discuss the diseases that affect each section of the gastrointestinal tract. Disorders that typically involve more than one segment, such as Crohn disease, are considered with the most frequently involved region.

Oral Cavity

Pathologic conditions of the oral cavity can be broadly divided into diseases affecting the oral mucosa, salivary glands, and jaws. Discussed next are the more common conditions affecting these sites. Although common, disorders affecting the teeth and supporting structures are not considered here. Reference should be made to specialized texts. Odontogenic cysts and tumors (benign and malignant), which are derived from the epithelial and/or mesenchymal tissues associated with tooth development, also are discussed briefly.

Oral Inflammatory Lesions

Aphthous Ulcers (Canker Sores)

These common superficial mucosal ulcerations affect up to 40% of the population. They are more common in the first two decades of life, extremely painful, and recurrent. Although the cause of aphthous ulcers is not known, they do tend to be more prevalent within some families and may be associated with celiac disease, inflammatory bowel disease (IBD), and Behçet disease. Lesions can be solitary or multiple; typically, they are shallow, hyperemic ulcerations covered by a thin exudate and rimmed by a narrow zone of erythema (Fig. 14–1). In most cases they resolve spontaneously in 7 to 10 days but can recur.

Herpes Simplex Virus Infections

Most orofacial herpetic infections are caused by herpes simplex virus type 1 (HSV-1), with the remainder being caused by HSV-2 (genital herpes). With changing sexual practices, oral HSV-2 is increasingly common. Primary infections typically occur in children between 2 and 4 years of age and are often asymptomatic. However, in 10% to 20% of cases the primary infection manifests as acute herpetic gingivostomatitis, with abrupt onset of vesicles and ulcerations throughout the oral cavity. Most adults harbor latent HSV-1, and the virus can be reactivated, resulting in a so-called “cold sore” or recurrent herpetic stomatitis. Factors associated with HSV reactivation include trauma, allergies, exposure to ultraviolet light, upper respiratory tract infections, pregnancy, menstruation, immunosuppression, and exposure to extremes of temperature. These recurrent lesions, which occur at the site of primary inoculation or in adjacent mucosa innervated by the same ganglion, typically appear as groups of small (1 to 3 mm) vesicles. The lips (herpes labialis), nasal orifices, buccal mucosa, gingiva, and hard palate are the most common locations. Although lesions typically resolve within 7 to 10 days, they can persist in immunocompromised patients, who may require systemic antiviral therapy. Morphologically, the lesions resemble those seen in esophageal herpes (see Fig. 14–8) and genital herpes (Chapter 17). The infected cells become ballooned and have large eosinophilic intranuclear inclusions. Adjacent cells commonly fuse to form large multinucleated polykaryons.

Oral Candidiasis (Thrush)

Candidiasis is the most common fungal infection of the oral cavity. Candida albicans is a normal component of the oral flora and only produces disease under unusual circumstances. Modifying factors include:

Broad-spectrum antibiotics that alter the normal microbiota can also promote oral candidiasis. The three major clinical forms of oral candidiasis are pseudomembranous, erythematous, and hyperplastic. The pseudomembranous form is most common and is known as thrush. This condition is characterized by a superficial, curdlike, gray to white inflammatory membrane composed of matted organisms enmeshed in a fibrinosuppurative exudate that can be readily scraped off to reveal an underlying erythematous base. In mildly immunosuppressed or debilitated individuals, such as diabetics, the infection usually remains superficial, but can spread to deep sites in association with more severe immunosuppression, including that seen in organ or hematopoietic stem cell transplant recipients, as well as patients with neutropenia, chemotherapy-induced immunosuppression, or AIDS.

![]() Summary

Summary

Oral Inflammatory Lesions

• Aphthous ulcers are painful superficial ulcers of unknown etiology that may be associated with systemic diseases.

• Herpes simplex virus causes a self-limited infection that presents with vesicles (cold sores, fever blisters) that rupture and heal, without scarring, and often leave latent virus in nerve ganglia. Reactivation can occur.

• Oral candidiasis may occur when the oral microbiota is altered (e.g., after antibiotic use). Invasive disease may occur in immunosuppressed individuals.

Proliferative and Neoplastic Lesions of the Oral Cavity

Fibrous Proliferative Lesions

Fibromas (Fig. 14–2, A) are submucosal nodular fibrous tissue masses that are formed when chronic irritation results in reactive connective tissue hyperplasia. They occur most often on the buccal mucosa along the bite line and are thought to be reactions to chronic irritation. Treatment is complete surgical excision and removal of the source of irritation.

Figure 14–2 Fibrous proliferations. A, Fibroma. Smooth pink exophytic nodule on the buccal mucosa. B, Pyogenic granuloma. Erythematous hemorrhagic exophytic mass arising from the gingival mucosa.

Pyogenic granulomas (Fig. 14–2, B) are pedunculated masses usually found on the gingiva of children, young adults, and pregnant women. These lesions are richly vascular and typically are ulcerated, which gives them a red to purple color. In some cases, growth can be rapid and raise fear of a malignant neoplasm. However, histologic examination demonstrates a dense proliferation of immature vessels similar to that seen in granulation tissue. Pyogenic granulomas can regress, mature into dense fibrous masses, or develop into a peripheral ossifying fibroma. Complete surgical excision is definitive treatment.

Leukoplakia and Erythroplakia

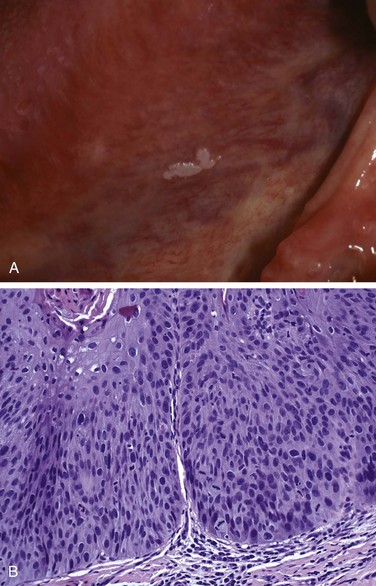

Leukoplakia is defined by the World Health Organization as “a white patch or plaque that cannot be scraped off and cannot be characterized clinically or pathologically as any other disease.” This clinical term is reserved for lesions that arise in the oral cavity in the absence of any known etiologic factor (Fig. 14–3, A). Accordingly, white patches caused by obvious irritation or entities such as lichen planus and candidiasis are not considered leukoplakia. Approximately 3% of the world’s population has leukoplakic lesions, of which 5% to 25% are premalignant and may progress to squamous cell carcinoma. Thus, until proved otherwise by means of histologic evaluation, all leukoplakias must be considered precancerous. A related but less common lesion, erythroplakia, is a red, velvety, possibly eroded area that is flat or slightly depressed relative to the surrounding mucosa. Erythroplakia is associated with a much greater risk of malignant transformation than leukoplakia. While leukoplakia and erythroplakia may be seen in adults at any age, they typically affect persons between the ages of 40 and 70 years, with a 2 : 1 male preponderance. Although the etiology is multifactorial, tobacco use (cigarettes, pipes, cigars, and chewing tobacco) is the most common risk factor for leukoplakia and erythroplakia.

Figure 14–3 Leukoplakia. A, Clinical appearance of leukoplakia is highly variable. In this example, the lesion is smooth with well-demarcated borders and minimal elevation. B, Histologic appearance of leukoplakia showing dysplasia, characterized by nuclear and cellular pleomorphism and loss of normal maturation.

![]() Morphology

Morphology

Leukoplakia includes a spectrum of histologic features ranging from hyperkeratosis overlying a thickened, acanthotic, but orderly mucosal lesions with marked dysplasia that sometimes merges with carcinoma in situ (Fig. 14–3, B). The most severe dysplastic changes are associated with erythroplakia, and more than 50% of these cases undergo malignant transformation. With increasing dysplasia and anaplasia, a subjacent inflammatory cell infiltrate of lymphocytes and macrophages is often present.

Squamous Cell Carcinoma

Approximately 95% of cancers of the oral cavity are squamous cell carcinomas, with the remainder largely consisting of adenocarcinomas of salivary glands, as discussed later. This aggressive epithelial malignancy is the sixth most common neoplasm in the world today. Despite numerous advances in treatment, the overall long-term survival rate has been less than 50% for the past 50 years. This dismal outlook is due to several factors, most notably the fact that oral cancer often is diagnosed at an advanced stage.

Multiple primary tumors may be present at initial diagnosis but more often are detected later, at an estimated rate of 3% to 7% per year; patients who survive 5 years after diagnosis of the initial tumor have up to a 35% chance of developing at least one new primary tumor within that interval. The development of these secondary tumors can be particularly devastating for persons whose initial lesions were small. Thus, despite a 5-year survival rate greater than 50% for patients with small tumors, these patients often die of second primary tumors. Therefore, surveillance and early detection of new premalignant lesions are critical for the long-term survival of patients with oral squamous cell carcinoma.

The elevated risk of additional primary tumors in these patients has led to the concept of “field cancerization.” This hypothesis suggests that multiple primary tumors develop independently as a result of years of chronic mucosal exposure to carcinogens such as alcohol or tobacco (described next).

![]() Pathogenesis

Pathogenesis

Squamous cancers of the oropharynx arise through two distinct pathogenic pathways. One group of tumors in the oral cavity occurs mainly in persons who are chronic alcohol and tobacco (both smoked and chewed) users. Deep sequencing of these cancers has revealed frequent mutations that bear a molecular signature consistent with exposure to carcinogens in tobacco. These mutations frequently involve TP53 and genes that regulate the differentiation of squamous cells, such as p63 and NOTCH1. The second group of tumors tends to occur in the tonsillar crypts or the base of the tongue and harbor oncogenic variants of human papillomavirus (HPV), particularly HPV-16. These tumors carry far fewer mutations than those associated with tobacco exposure and often overexpress p16, a cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor. It is predicted that the incidence of HPV-associated oropharyngeal squamous cell carcinoma will surpass that of cervical cancer in the next decade, in part because the anatomic sites of origin—tonsillar crypts, base of tongue, and oropharynx—are not readily accessible or amenable to cytologic screening (unlike the cervix). Notably, the prognosis for patients with HPV-positive tumors is better than for those with HPV-negative tumors. The HPV vaccine, which is protective against cervical cancer, offers hope to limit the increasing frequency of HPV-associated oropharyngeal squamous cell carcinoma.

In India and southeast Asia, chewing of betel quid and paan are important predisposing factors. Betel quid is a “witch’s brew” containing araca nut, slaked lime, and tobacco, all wrapped in betel nut leaf. It is likely that these tumors arise by a pathway similar to that characterized for tobacco use–associated tumors in the West.

![]() Morphology

Morphology

Squamous cell carcinoma may arise anywhere in the oral cavity. However, the most common locations are the ventral surface of the tongue, floor of the mouth, lower lip, soft palate, and gingiva (Fig. 14–4, A). In early stages, these cancers can appear as raised, firm, pearly plaques or as irregular, roughened, or verrucous mucosal thickenings. Either pattern may be superimposed on a background of a leukoplakia or erythroplakia. As these lesions enlarge, they typically form ulcerated and protruding masses that have irregular and indurated or rolled borders. Histopathologic analysis has shown that squamous cell carcinoma develops from dysplastic precursor lesions. Histologic patterns range from well-differentiated keratinizing neoplasms (Fig. 14–4, B) to anaplastic, sometimes sarcomatoid tumors. However, the degree of histologic differentiation, as determined by the relative degree of keratinization, does not necessarily correlate with biologic behavior. Typically, oral squamous cell carcinoma infiltrates locally before it metastasizes. The cervical lymph nodes are the most common sites of regional metastasis; frequent sites of distant metastases include the mediastinal lymph nodes, lungs, and liver.

![]() Summary

Summary

Lesions of the Oral Cavity

• Fibromas and pyogenic granulomas are common reactive lesions of the oral mucosa.

• Leukoplakias are mucosal plaques that may undergo malignant transformation.

• The risk of malignant transformation is greater in erythroplakia (relative to leukoplakia).

• A majority of oral cavity cancers are squamous cell carcinomas.

• Oral squamous cell carcinomas are classically linked to tobacco and alcohol use, but the incidence of HPV-associated lesions is rising.

Diseases of Salivary Glands

There are three major salivary glands—parotid, submandibular, and sublingual—as well as innumerable minor salivary glands distributed throughout the oral mucosa. Inflammatory or neoplastic disease may develop within any of these.

Xerostomia

Xerostomia is defined as a dry mouth resulting from a decrease in the production of saliva. Its incidence varies among populations, but has been reported in more than 20% of individuals above the age of 70 years. It is a major feature of the autoimmune disorder Sjögren syndrome, in which it usually is accompanied by dry eyes (Chapter 4). A lack of salivary secretions is also a major complication of radiation therapy. However, xerostomia is most frequently observed as a result of many commonly prescribed classes of medications including anticholinergic, antidepressant/antipsychotic, diuretic, antihypertensive, sedative, muscle relaxant, analgesic, and antihistaminic agents. The oral cavity may merely reveal dry mucosa and/or atrophy of the papillae of the tongue, with fissuring and ulcerations, or, in Sjögren syndrome, concomitant inflammatory enlargement of the salivary glands. Complications of xerostomia include increased rates of dental caries and candidiasis, as well as difficulty in swallowing and speaking.

Sialadenitis

Sialadenitis, or inflammation of the salivary glands, may be induced by trauma, viral or bacterial infection, or autoimmune disease. The most common form of viral sialadenitis is mumps, which may produce enlargement of all salivary glands but predominantly involves the parotids. The mumps virus is a paramyxovirus related to the influenza and parainfluenza viruses. Mumps produces interstitial inflammation marked by a mononuclear inflammatory infiltrate. While mumps in children is most often a self-limited benign condition, in adults it can cause pancreatitis or orchitis; the latter sometimes causes sterility.

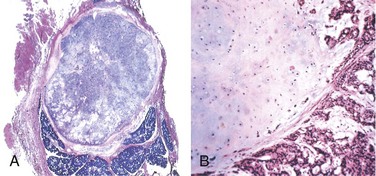

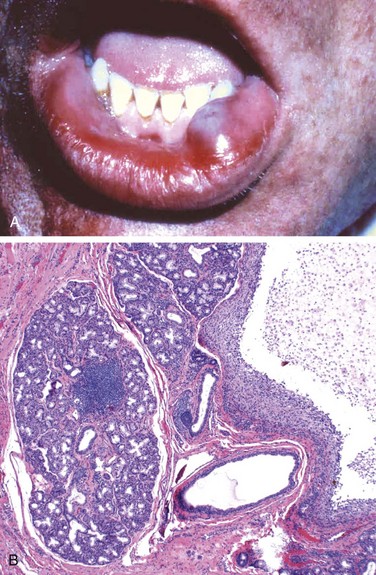

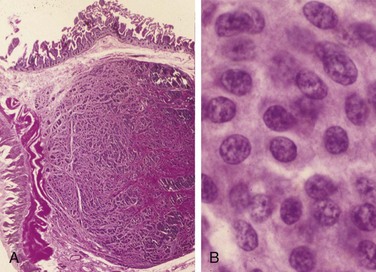

The mucocele is the most common inflammatory lesion of the salivary glands, and results from either blockage or rupture of a salivary gland duct, with consequent leakage of saliva into the surrounding connective tissue stroma. Mucocele occurs most often in toddlers, young adults, and the aged, and typically manifests as a fluctuant swelling of the lower lip that may change in size, particularly in association with meals (Fig. 14–5, A). Histologic examination demonstrates a cystlike space lined by inflammatory granulation tissue or fibrous connective tissue that is filled with mucin and inflammatory cells, particularly macrophages (Fig. 14–5, B). Complete excision of the cyst and the minor salivary gland lobule constitutes definitive treatment.

Figure 14–5 Mucocele. A, Fluctuant fluid-filled lesion on the lower lip subsequent to trauma. B, Cystlike cavity (right) filled with mucinous material and lined by organizing granulation tissue.

Bacterial sialadenitis is a common infection that most often involves the major salivary glands, particularly the submandibular glands. The most frequent pathogens are Staphylococcus aureus and Streptococcus viridans. Duct obstruction by stones (sialolithiasis) is a common antecedent to infection; it may also be induced by impacted food debris or by edema consequent to injury. Dehydration and decreased secretory function also may predispose to bacterial invasion and sometimes are associated with long-term phenothiazine therapy, which suppresses salivary secretion. Systemic dehydration, with decreased salivary secretions, may predispose to suppurative bacterial parotitis in elderly patients following major thoracic or abdominal surgery. This obstructive process and bacterial invasion lead to a nonspecific inflammation of the affected glands that may be largely interstitial or, when induced by staphylococcal or other pyogens, may be associated with overt suppurative necrosis and abscess formation.

Autoimmune sialadenitis, also called Sjögren syndrome, is discussed in Chapter 4.

Neoplasms

Despite their relatively simple morphology, the salivary glands give rise to at least 30 histologically distinct tumors. As indicated in Table 14–1, a small number of these neoplasms account for more than 90% of tumors. Overall, salivary gland tumors are relatively uncommon and represent less than 2% of all human tumors. Approximately 65% to 80% arise within the parotid, 10% in the submandibular gland, and the remainder in the minor salivary glands, including the sublingual glands. Approximately 15% to 30% of tumors in the parotid glands are malignant. By contrast, approximately 40% of submandibular, 50% of minor salivary gland, and 70% to 90% of sublingual tumors are cancerous. Thus, the likelihood that a salivary gland tumor is malignant is inversely proportional, roughly, to the size of the gland.

Table 14–1 Histopathologic Classification and Prevalence of the Most Common Benign and Malignant Salivary Gland Tumors

| Benign | Malignant |

|---|---|

NOS, not otherwise specified.

Data from Ellis GL, Auclair PL, Gnepp DR: Surgical Pathology of the Salivary Glands, Vol 25: Major Problems in Pathology, Philadelphia, WB Saunders, 1991.

Salivary gland tumors usually occur in adults, with a slight female predominance, but about 5% occur in children younger than 16 years of age. Whatever the histologic pattern, parotid gland neoplasms produce swelling in front of and below the ear. In general, when they are first diagnosed, both benign and malignant lesions are usually 4 to 6 cm in diameter and are mobile on palpation except in the case of neglected malignant tumors. Benign tumors may be present for months to several years before coming to clinical attention, while cancers more often come to attention promptly, probably because of their more rapid growth. However, there are no reliable criteria to differentiate benign from malignant lesions on clinical grounds, and histopathologic evaluation is essential.

Pleomorphic Adenoma

Pleomorphic adenomas present as painless, slow-growing, mobile discrete masses. They represent about 60% of tumors in the parotid, are less common in the submandibular glands, and are relatively rare in the minor salivary glands. Pleomorphic adenomas are benign tumors that consist of a mixture of ductal (epithelial) and myoepithelial cells, so they exhibit both epithelial and mesenchymal differentiation. Epithelial elements are dispersed throughout the matrix, which may contain variable mixtures of myxoid, hyaline, chondroid (cartilaginous), and even osseous tissue. In some pleomorphic adenomas, the epithelial elements predominate; in others, they are present only in widely dispersed foci. This histologic diversity has given rise to the alternative, albeit less preferred name mixed tumor. The tumors consistently overexpress the transcription factor PLAG1, often because of chromosomal rearrangements involving the PLAG1 gene, but how PLAG1 contributes to tumor development is unknown.

Pleomorphic adenomas recur if incompletely excised: Recurrence rates approach 25% after simple enucleation of the tumor, but are only 4% after wider resection. In both settings, recurrence stems from a failure to recognize minute extensions of tumor into surrounding soft tissues.

Carcinoma arising in a pleomorphic adenoma is referred to variously as a carcinoma ex pleomorphic adenoma or malignant mixed tumor. The incidence of malignant transformation increases with time from 2% of tumors present for less than 5 years to almost 10% for those present for more than 15 years. The cancer usually takes the form of an adenocarcinoma or undifferentiated carcinoma. Unfortunately, these are among the most aggressive malignant neoplasms of salivary glands, with mortality rates of 30% to 50% at 5 years.

![]() Morphology

Morphology

Pleomorphic adenomas typically manifest as rounded, well-demarcated masses rarely exceeding 6 cm in the greatest dimension. Although they are encapsulated, in some locations (particularly the palate), the capsule is not fully developed, and expansile growth produces protrusions into the surrounding tissues. The cut surface is gray-white and typically contains myxoid and blue translucent chondroid (cartilage-like) areas. The most striking histologic feature is their characteristic heterogeneity. Epithelial elements resembling ductal or myoepithelial cells are arranged in ducts, acini, irregular tubules, strands, or even sheets. These typically are dispersed within a mesenchyme-like background of loose myxoid tissue containing islands of chondroid and, rarely, foci of bone (Fig. 14–6). Sometimes the epithelial cells form well-developed ducts lined by cuboidal to columnar cells with an underlying layer of deeply chromatic, small myoepithelial cells. In other instances there may be strands or sheets of myoepithelial cells. Islands of well-differentiated squamous epithelium also may be present. In most cases, no epithelial dysplasia or mitotic activity is evident. No difference in biologic behavior has been observed between the tumors composed largely of epithelial elements and those composed largely of mesenchymal elements.

Mucoepidermoid Carcinoma

Mucoepidermoid carcinomas are composed of variable mixtures of squamous cells, mucus-secreting cells, and intermediate cells. These neoplasms represent about 15% of all salivary gland tumors, and while they occur mainly (60% to 70%) in the parotids, they account for a large fraction of salivary gland neoplasms in the other glands, particularly the minor salivary glands. Overall, mucoepidermoid carcinoma is the most common form of primary malignant tumor of the salivary glands. It is commonly associated with chromosome rearrangements involving MAML2, a gene that encodes a signaling protein in the Notch pathway.

![]() Morphology

Morphology

Mucoepidermoid carcinomas can grow as large as 8 cm in diameter and, although they are apparently circumscribed, they lack well-defined capsules and often are infiltrative. The cut surface is pale gray to white and frequently demonstrates small, mucinous cysts. On histologic examination, these tumors contain cords, sheets, or cysts lined by squamous, mucous, or intermediate cells. The latter is a hybrid cell type with both squamous features and mucus-filled vacuoles, which are most easily detected with mucin stains. Cytologically, tumor cells may be benign-appearing or highly anaplastic and unmistakably malignant. On this basis, mucoepidermoid carcinomas are subclassified as low-, intermediate-, or high-grade.

Clinical course and prognosis depend on histologic grade. Low-grade tumors may invade locally and recur in about 15% of cases but metastasize only rarely and afford a 5-year survival rate over 90%. By contrast, high-grade neoplasms and, to a lesser extent, intermediate-grade tumors are invasive and difficult to excise. As a result, they recur in 25% to 30% of cases, and about 30% metastasize to distant sites. The 5-year survival rate is only 50%.

![]() Summary

Summary

Diseases of Salivary Glands

• Sialadenitis (inflammation of the salivary glands) can be caused by trauma, infection (such as mumps), or an autoimmune reaction.

• Pleomorphic adenoma is a slow-growing neoplasm composed of a heterogeneous mixture of epithelial and mesenchymal cells.

• Mucoepidermoid carcinoma is a malignant neoplasm of variable biologic aggressiveness that is composed of a mixture of squamous and mucous cells.

Odontogenic Cysts and Tumors

In contrast with other skeletal sites, epithelium-lined cysts are common in the jaws. A majority of these cysts are derived from remnants of odontogenic epithelium. In general, these cysts are subclassified as either inflammatory or developmental. Only the most common of these lesions are considered here.

The dentigerous cyst originates around the crown of an unerupted tooth and is thought to be the result of a degeneration of the dental follicle (primordial tissue that makes the enamel surface of teeth). On radiographic evaluation, these unilocular lesions most often are associated with impacted third molar (wisdom) teeth. They are lined by a thin, stratified squamous epithelium that typically is associated with a dense chronic inflammatory infiltrate within the underlying connective tissue. Complete removal is curative.

Odontogenic keratocysts can occur at any age but are most frequent in persons between 10 and 40 years of age, have a male predominance, and typically are located within the posterior mandible. Differentiation of the odontogenic keratocyst from other odontogenic cysts is important because it is locally aggressive and has a high recurrence rate. On radiographic evaluation, odontogenic keratocysts are seen as well-defined unilocular or multilocular radiolucencies. On histologic examination, the cyst lining consists of a thin layer of parakeratinized or orthokeratinized stratified squamous epithelium with a prominent basal cell layer and a corrugated luminal epithelial surface. Treatment requires aggressive and complete removal; recurrence rates of up to 60% are associated with inadequate resection. Multiple odontogenic keratocysts may occur, particularly in patients with the nevoid basal cell carcinoma syndrome (Gorlin syndrome).

In contrast with the developmental cysts just described, the periapical cyst has an inflammatory etiology. These extremely common lesions occur at the tooth apex as a result of long-standing pulpitis, which may be caused by advanced caries or trauma. Necrosis of the pulpal tissue, which can traverse the length of the root and exit the apex of the tooth into the surrounding alveolar bone, can lead to a periapical abscess. Over time, granulation tissue (with or without an epithelial lining) may develop. These are often designated periapical granuloma. Although the lesion does not show true granulomatous inflammation, old terminology, like bad habits, is difficult to shed. Periapical inflammatory lesions persist as a result of bacteria or other offensive agents in the area. Successful treatment, therefore, necessitates the complete removal of the offending material followed by restoration or extraction of the tooth.

Odontogenic tumors are a complex group of lesions with diverse histologic appearances and clinical behaviors. Some are true neoplasms, either benign or malignant, while others are thought to be hamartomatous. Odontogenic tumors are derived from odontogenic epithelium, ectomesenchyme, or both. The two most common and clinically significant tumors are ameloblastoma and odontoma.

Ameloblastomas arise from odontogenic epithelium and do not demonstrate chondroid or osseous differentiation. These typically cystic lesions are slow-growing and, despite being locally invasive, have an indolent course.

Odontoma, the most common type of odontogenic tumor, arises from epithelium but shows extensive deposition of enamel and dentin. Odontomas are cured by local excision.

![]() Summary

Summary

Odontogenic Cysts and Tumors

• The jaws are a common site of epithelium-lined cysts derived from odontogenic remnants.

• The odontogenic keratocyst is locally aggressive, with a high recurrence rate.

• The periapical cyst is a reactive, inflammatory lesion associated with caries or dental trauma.

• The most common odontogenic tumors are ameloblastoma and odontoma.

Esophagus

The esophagus develops from the cranial portion of the foregut. It is a hollow, highly distensible muscular tube that extends from the epiglottis to the gastroesophageal junction, located just above the diaphragm. Acquired diseases of the esophagus run the gamut from lethal cancers to “heartburn,” with clinical manifestations ranging from chronic and incapacitating disease to mere annoyance.

Obstructive and Vascular Diseases

Mechanical Obstruction

Atresia, fistulas, and duplications may occur in any part of the gastrointestinal tract. When they involve the esophagus, they are discovered shortly after birth, usually because of regurgitation during feeding, and must be corrected promptly. Absence, or agenesis, of the esophagus is extremely rare. Atresia, in which a thin, noncanalized cord replaces a segment of esophagus, is more common. Atresia occurs most commonly at or near the tracheal bifurcation and usually is associated with a fistula connecting the upper or lower esophageal pouches to a bronchus or the trachea. This abnormal connection can result in aspiration, suffocation, pneumonia, or severe fluid and electrolyte imbalances.

Passage of food can be impeded by esophageal stenosis. The narrowing generally is caused by fibrous thickening of the submucosa, atrophy of the muscularis propria, and secondary epithelial damage. Stenosis most often is due to inflammation and scarring, which may be caused by chronic gastroesophageal reflux, irradiation, or caustic injury. Stenosis-associated dysphagia usually is progressive; difficulty eating solids typically occurs long before problems with liquids.

Functional Obstruction

Efficient delivery of food and fluids to the stomach requires a coordinated wave of peristaltic contractions. Esophageal dysmotility interferes with this process and can take several forms, all of which are characterized by discoordinated contraction or spasm of the muscularis. Because it increases esophageal wall stress, spasm also can cause small diverticula to form.

Increased lower esophageal sphincter (LES) tone can result from impaired smooth muscle relaxation with consequent functional esophageal obstruction. Achalasia is characterized by the triad of incomplete LES relaxation, increased LES tone, and esophageal aperistalsis. Primary achalasia is caused by failure of distal esophageal inhibitory neurons and is, by definition, idiopathic. Degenerative changes in neural innervation, either intrinsic to the esophagus or within the extraesophageal vagus nerve or the dorsal motor nucleus of the vagus, also may occur. Secondary achalasia may arise in Chagas disease, in which Trypanosoma cruzi infection causes destruction of the myenteric plexus, failure of LES relaxation, and esophageal dilatation. Duodenal, colonic, and ureteric myenteric plexuses also can be affected in Chagas disease. Achalasia-like disease may be caused by diabetic autonomic neuropathy; infiltrative disorders such as malignancy, amyloidosis, or sarcoidosis; and lesions of dorsal motor nuclei, which may be produced by polio or surgical ablation.

Ectopia

Ectopic tissues (developmental rests) are common in the gastrointestinal tract. The most frequent site of ectopic gastric mucosa is the upper third of the esophagus, where it is referred to as an inlet patch. Although the presence of such tissue generally is asymptomatic, acid released by gastric mucosa within the esophagus can result in dysphagia, esophagitis, Barrett esophagus, or, rarely, adenocarcinoma. Gastric heterotopia, small patches of ectopic gastric mucosa in the small bowel or colon, may manifest with occult blood loss secondary to peptic ulceration of adjacent mucosa.

Esophageal Varices

Instead of returning directly to the heart, venous blood from the gastrointestinal tract is delivered to the liver via the portal vein before reaching the inferior vena cava. This circulatory pattern is responsible for the first-pass effect, in which drugs and other materials absorbed in the intestines are processed by the liver before entering the systemic circulation. Diseases that impede this flow cause portal hypertension, which can lead to the development of esophageal varices, an important cause of esophageal bleeding.

![]() Pathogenesis

Pathogenesis

One of the few sites where the splanchnic and systemic venous circulations can communicate is the esophagus. Thus, portal hypertension induces development of collateral channels that allow portal blood to shunt into the caval system. However, these collateral veins enlarge the subepithelial and submucosal venous plexi within the distal esophagus. These vessels, termed varices, develop in 90% of cirrhotic patients, most commonly in association with alcoholic liver disease. Worldwide, hepatic schistosomiasis is the second most common cause of varices. A more detailed consideration of portal hypertension is given in Chapter 15.

![]() Morphology

Morphology

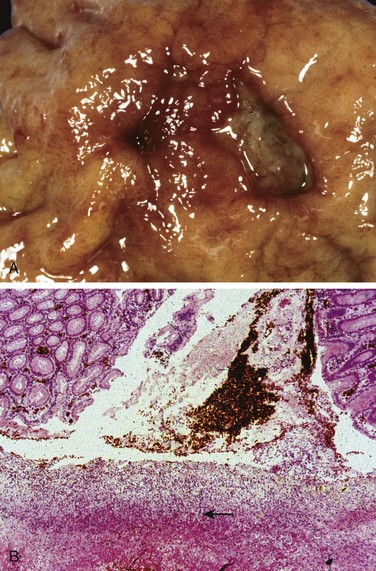

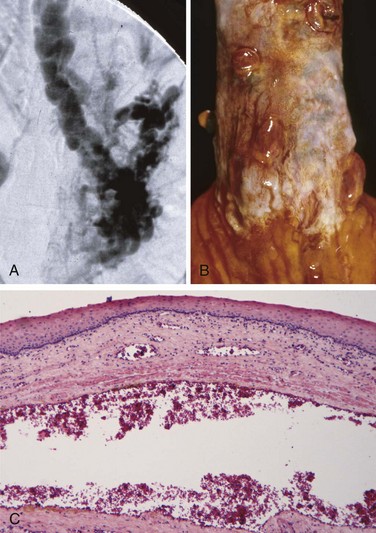

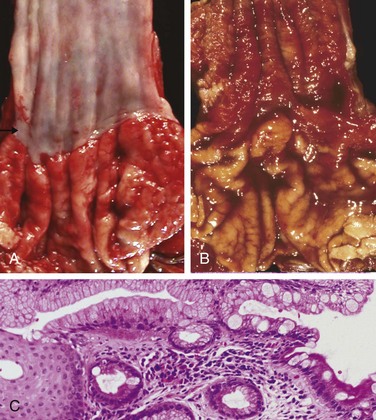

Varices can be detected by angiography (Fig. 14–7, A) and appear as tortuous dilated veins lying primarily within the submucosa of the distal esophagus and proximal stomach. Varices may not be obvious on gross inspection of surgical or postmortem specimens, because they collapse in the absence of blood flow (Fig. 14–7, B). The overlying mucosa can be intact (Fig. 14–7, C) but is ulcerated and necrotic if rupture has occurred.

Figure 14–7 Esophageal varices. A, Angiogram showing several tortuous esophageal varices. Although the angiogram is striking, endoscopy is more commonly used to identify varices. B, Collapsed varices are present in this postmortem specimen corresponding to the angiogram in A. The polypoid areas are sites of variceal hemorrhage that were ligated with bands. C, Dilated varices beneath intact squamous mucosa.

Clinical Features

Varices often are asymptomatic, but their rupture can lead to massive hematemesis and death. Variceal rupture therefore constitutes a medical emergency. Despite intervention, as many as half of the patients die from the first bleeding episode, either as a direct consequence of hemorrhage or due to hepatic coma triggered by the protein load that results from intraluminal bleeding and hypovolemic shock. Among those who survive, additional episodes of hemorrhage, each potentially fatal, occur in more than 50% of cases. As a result, greater than half of the deaths associated with advanced cirrhosis result from variceal rupture.

Esophagitis

Lacerations

The most common esophageal lacerations are Mallory-Weiss tears, which are often associated with severe retching or vomiting, as may occur with acute alcohol intoxication. Normally, a reflex relaxation of the gastroesophageal musculature precedes the antiperistaltic contractile wave associated with vomiting. This relaxation is thought to fail during prolonged vomiting, with the result that refluxing gastric contents overwhelm the gastric inlet and cause the esophageal wall to stretch and tear. Patients often present with hematemesis.

The roughly linear lacerations of Mallory-Weiss syndrome are longitudinally oriented, range in length from millimeters to several centimeters, and usually cross the gastroesophageal junction. These tears are superficial and do not generally require surgical intervention; healing tends to be rapid and complete. By contrast, Boerhaave syndrome, characterized by transmural esophageal tears and mediastinitis, occurs rarely and is a catastrophic event. The factors giving rise to this syndrome are similar to those for Mallory-Weiss tears, but more severe.

Chemical and Infectious Esophagitis

The stratified squamous mucosa of the esophagus may be damaged by a variety of irritants including alcohol, corrosive acids or alkalis, excessively hot fluids, and heavy smoking. Medicinal pills may lodge and dissolve in the esophagus, rather than passing into the stomach intact, resulting in a condition termed pill-induced esophagitis. Esophagitis due to chemical injury generally causes only self-limited pain, particularly odynophagia (pain with swallowing). Hemorrhage, stricture, or perforation may occur in severe cases. Iatrogenic esophageal injury may be caused by cytotoxic chemotherapy, radiation therapy, or graft-versus-host disease. The morphologic changes are nonspecific with ulceration and accumulation of neutrophils. Irradiation causes blood vessel thickening adding some element of ischemic injury.

Infectious esophagitis may occur in otherwise healthy persons but is most frequent in those who are debilitated or immunosuppressed. In these patients, esophageal infection by herpes simplex viruses, cytomegalovirus (CMV), or fungal organisms is common. Among fungi, Candida is the most common pathogen, although mucormycosis and aspergillosis may also occur. The esophagus may also be involved in desquamative skin diseases such as bullous pemphigoid and epidermolysis bullosa and, rarely, Crohn disease.

Infection by fungi or bacteria can be primary or complicate a preexisting ulcer. Nonpathogenic oral bacteria frequently are found in ulcer beds, while pathogenic organisms, which account for about 10% of infectious esophagitis cases, may invade the lamina propria and cause necrosis of overlying mucosa. Candidiasis, in its most advanced form, is characterized by adherent, gray-white pseudomembranes composed of densely matted fungal hyphae and inflammatory cells covering the esophageal mucosa.

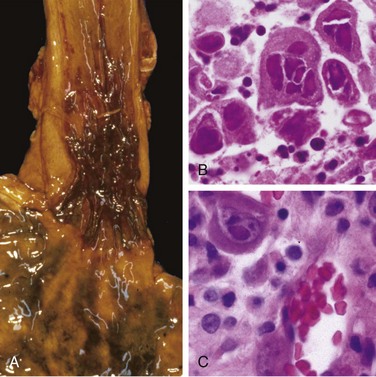

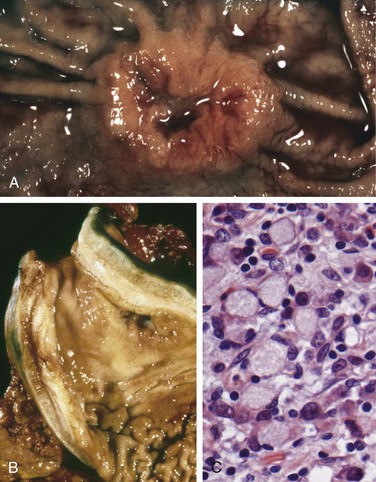

The endoscopic appearance often provides a clue to the identity of the infectious agent in viral esophagitis. Herpesviruses typically cause punched-out ulcers (Fig. 14–8, A), and histopathologic analysis demonstrates nuclear viral inclusions within a rim of degenerating epithelial cells at the ulcer edge (Fig. 14–8, B). By contrast, CMV causes shallower ulcerations and characteristic nuclear and cytoplasmic inclusions within capillary endothelium and stromal cells (Fig. 14–8, C). Immunohistochemical staining for viral antigens can be used as an ancillary diagnostic tool.

Reflux Esophagitis

The stratified squamous epithelium of the esophagus is resistant to abrasion from foods but is sensitive to acid. The submucosal glands of the proximal and distal esophagus contribute to mucosal protection by secreting mucin and bicarbonate. More important, constant LES tone prevents reflux of acidic gastric contents, which are under positive pressure. Reflux of gastric contents into the lower esophagus is the most frequent cause of esophagitis and the most common outpatient gastrointestinal diagnosis in the United States. The associated clinical condition is termed gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD).

![]() Pathogenesis

Pathogenesis

Reflux of gastric juices is central to the development of mucosal injury in GERD. In severe cases, duodenal bile reflux may exacerbate the damage. Conditions that decrease LES tone or increase abdominal pressure contribute to GERD and include alcohol and tobacco use, obesity, central nervous system depressants, pregnancy, hiatal hernia (discussed later), delayed gastric emptying, and increased gastric volume. In many cases, no definitive cause is identified.

![]() Morphology

Morphology

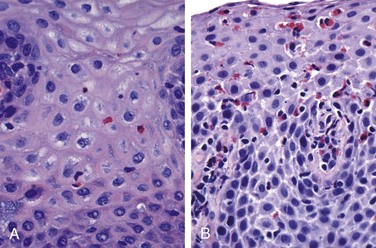

Simple hyperemia, evident to the endoscopist as redness, may be the only alteration. In mild GERD the mucosal histology is often unremarkable. With more significant disease, eosinophils are recruited into the squamous mucosa, followed by neutrophils, which usually are associated with more severe injury (Fig. 14–9, A). Basal zone hyperplasia exceeding 20% of the total epithelial thickness and elongation of lamina propria papillae, such that they extend into the upper third of the epithelium, also may be present.

Clinical Features

GERD is most common in adults older than 40 years of age but also occurs in infants and children. The most frequently reported symptoms are heartburn, dysphagia, and, less often, noticeable regurgitation of sour-tasting gastric contents. Rarely, chronic GERD is punctuated by attacks of severe chest pain that may be mistaken for heart disease. Treatment with proton pump inhibitors reduces gastric acidity and typically provides symptomatic relief. While the severity of symptoms is not closely related to the degree of histologic damage, the latter tends to increase with disease duration. Complications of reflux esophagitis include esophageal ulceration, hematemesis, melena, stricture development, and Barrett esophagus.

Hiatal hernia is characterized by separation of the diaphragmatic crura and protrusion of the stomach into the thorax through the resulting gap. Congenital hiatal hernias are recognized in infants and children, but many are acquired in later life. Hiatal hernia is asymptomatic in more than 90% of adult cases. Thus, symptoms, which are similar to GERD, are often associated with other causes of LES incompetence.

Eosinophilic Esophagitis

The incidence of eosinophilic esophagitis is increasing markedly. Symptoms include food impaction and dysphagia in adults and feeding intolerance or GERD-like symptoms in children. The cardinal histologic feature is epithelial infiltration by large numbers of eosinophils, particularly superficially (Fig. 14–9, B) and at sites far from the gastroesophageal junction. Their abundance can help to differentiate eosinophilic esophagitis from GERD, Crohn disease, and other causes of esophagitis. Certain clinical characteristics, particularly failure of high-dose proton pump inhibitor treatment and the absence of acid reflux, are also typical. A majority of persons with eosinophilic esophagitis are atopic, and many have atopic dermatitis, allergic rhinitis, asthma, or modest peripheral eosinophilia. Treatments include dietary restrictions to prevent exposure to food allergens, such as cow milk and soy products, and topical or systemic corticosteroids.

Barrett Esophagus

Barrett esophagus is a complication of chronic GERD that is characterized by intestinal metaplasia within the esophageal squamous mucosa. The incidence of Barrett esophagus is rising; it is estimated to occur in as many as 10% of persons with symptomatic GERD. White males are affected most often and typically present between 40 and 60 years of age. The greatest concern in Barrett esophagus is that it confers an increased risk of esophageal adenocarcinoma. Molecular studies suggest that Barrett epithelium may be more similar to adenocarcinoma than to normal esophageal epithelium, consistent with the view that Barrett esophagus is a premalignant condition. In keeping with this, epithelial dysplasia, considered to be a preinvasive lesion, develops in 0.2% to 1.0% of persons with Barrett esophagus each year; its incidence increases with duration of symptoms and increasing patient age. Although the vast majority of esophageal adenocarcinomas are associated with Barrett esophagus, it should be noted that most persons with Barrett esophagus do not develop esophageal cancer.

![]() Morphology

Morphology

Barrett esophagus is recognized endoscopically as tongues or patches of red, velvety mucosa extending upward from the gastroesophageal junction. This metaplastic mucosa alternates with residual smooth, pale squamous (esophageal) mucosa proximally and interfaces with light-brown columnar (gastric) mucosa distally (Fig. 14–10, A and B). High-resolution endoscopes have increased the sensitivity of Barrett esophagus detection.

Figure 14–10 Barrett esophagus. A, Normal gastroesophageal junction. B, Barrett esophagus. Note the small islands of paler squamous mucosa within the Barrett mucosa. C, Histologic appearance of the gastroesophageal junction in Barrett esophagus. Note the transition between esophageal squamous mucosa (left) and metaplastic mucosa containing goblet cells (right).

Most authors require both endoscopic evidence of abnormal mucosa above the gastroesophageal junction and histologically documented gastric or intestinal metaplasia for diagnosis of Barrett esophagus. Goblet cells, which have distinct mucous vacuoles that stain pale blue by H&E and impart the shape of a wine goblet to the remaining cytoplasm, define intestinal metaplasia and are a feature of Barrett esophagus (Fig. 14–10, C). Dysplasia is classified as low-grade or high-grade on the basis of morphologic criteria. Intramucosal carcinoma is characterized by invasion of neoplastic epithelial cells into the lamina propria.

Clinical Features

Diagnosis of Barrett esophagus requires endoscopy and biopsy, usually prompted by GERD symptoms. The best course of management is a matter of debate. While many investigators agree that periodic endoscopy with biopsy, for detection of dysplasia, is reasonable, uncertainties about the frequency with which dysplasia occurs and whether it can regress spontaneously complicate clinical decision making. By contrast, intramucosal carcinoma requires therapeutic intervention. Treatment options include surgical resection (esophagectomy), and newer modalities such as photodynamic therapy, laser ablation, and endoscopic mucosectomy. Multifocal high-grade dysplasia, which carries a significant risk of progression to intramucosal or invasive carcinoma, may be treated in a fashion similar to intramucosal carcinoma.

Esophageal Tumors

Two morphologic variants account for a majority of esophageal cancers: adenocarcinoma and squamous cell carcinoma. Worldwide, squamous cell carcinoma is more common, but in the United States and other Western countries adenocarcinoma is on the rise. Other rare tumors occur but are not discussed here.

Adenocarcinoma

Esophageal adenocarcinoma typically arises in a background of Barrett esophagus and long-standing GERD. Risk of adenocarcinoma is greater in patients with documented dysplasia and is further increased by tobacco use, obesity, and previous radiation therapy. Conversely, reduced adenocarcinoma risk is associated with diets rich in fresh fruits and vegetables.

Esophageal adenocarcinoma occurs most frequently in whites and shows a strong gender bias, being seven times more common in men than in women. However, the incidence varies by a factor of 60 worldwide, with rates being highest in developed Western countries, including the United States, the United Kingdom, Canada, Australia, and the Netherlands, and lowest in Korea, Thailand, Japan, and Ecuador. In countries where esophageal adenocarcinoma is more common, the incidence has increased markedly since 1970, more rapidly than for almost any other cancer. As a result, esophageal adenocarcinoma, which represented less than 5% of esophageal cancers before 1970, now accounts for half of all esophageal cancers in the United States.

![]() Pathogenesis

Pathogenesis

Molecular studies suggest that the progression of Barrett esophagus to adenocarcinoma occurs over an extended period through the stepwise acquisition of genetic and epigenetic changes. This model is supported by the observation that epithelial clones identified in nondysplastic Barrett metaplasia persist and accumulate mutations during progression to dysplasia and invasive carcinoma. Chromosomal abnormalities and TP53 mutation are often present at early stages of esophageal adenocarcinoma. Additional genetic changes and inflammation also are thought to contribute to neoplastic progression.

![]() Morphology

Morphology

Esophageal adenocarcinoma usually occurs in the distal third of the esophagus and may invade the adjacent gastric cardia (Fig. 14–11, A). While early lesions may appear as flat or raised patches in otherwise intact mucosa, tumors may form large exophytic masses, infiltrate diffusely, or ulcerate and invade deeply. On microscopic examination, Barrett esophagus frequently is present adjacent to the tumor. Tumors typically produce mucin and form glands (Fig. 14–11, B).

Clinical Features

Although esophageal adenocarcinomas are occasionally discovered during evaluation of GERD or surveillance of Barrett esophagus, they more commonly manifest with pain or difficulty in swallowing, progressive weight loss, chest pain, or vomiting. By the time symptoms and signs appear, the tumor usually has spread to submucosal lymphatic vessels. As a result of the advanced stage at diagnosis, the overall 5-year survival rate is less than 25%. By contrast, 5-year survival approximates 80% in the few patients with adenocarcinoma limited to the mucosa or submucosa.

Squamous Cell Carcinoma

In the United States, esophageal squamous cell carcinoma typically occurs in adults older than 45 years of age and affects males four times more frequently than females. Risk factors include alcohol and tobacco use, poverty, caustic esophageal injury, achalasia, Plummer-Vinson syndrome, frequent consumption of very hot beverages, and previous radiation therapy to the mediastinum. It is nearly 6 times more common in African Americans than in whites—a striking risk disparity that cannot be accounted for by differences in rates of alcohol and tobacco use. The incidence of esophageal squamous cell carcinoma can vary by more than 100-fold between and within countries, being more common in rural and underdeveloped areas. The countries with highest incidences are Iran, central China, Hong Kong, Argentina, Brazil, and South Africa.

![]() Pathogenesis

Pathogenesis

A majority of esophageal squamous cell carcinomas in Europe and the United States are at least partially attributable to the use of alcohol and tobacco, the effects of which synergize to increase risk. However, esophageal squamous cell carcinoma also is common in some regions where alcohol and tobacco use is uncommon. Thus, nutritional deficiencies, as well as polycyclic hydrocarbons, nitrosamines, and other mutagenic compounds, such as those found in fungus-contaminated foods, have been considered as possible risk factors. HPV infection also has been implicated in esophageal squamous cell carcinoma in high-risk but not in low-risk regions. The molecular pathogenesis of esophageal squamous cell carcinoma remains incompletely defined.

![]() Morphology

Morphology

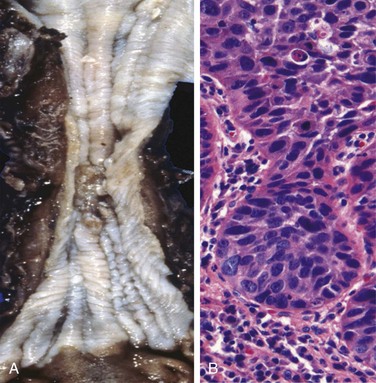

In contrast to the distal location of most adenocarcinomas, half of squamous cell carcinomas occur in the middle third of the esophagus (Fig. 14–12, A). Squamous cell carcinoma begins as an in situ lesion in the form of squamous dysplasia. Early lesions appear as small, gray-white plaquelike thickenings. Over months to years they grow into tumor masses that may be polypoid and protrude into and obstruct the lumen. Other tumors are either ulcerated or diffusely infiltrative lesions that spread within the esophageal wall, where they cause thickening, rigidity, and luminal narrowing. These cancers may invade surrounding structures including the respiratory tree, causing pneumonia; the aorta, causing catastrophic exsanguination; or the mediastinum and pericardium.

Figure 14–12 Esophageal squamous cell carcinoma.

A, Squamous cell carcinoma most frequently is found in the midesophagus, where it commonly causes strictures. B, Squamous cell carcinoma composed of nests of malignant cells that partially recapitulate the stratified organization of squamous epithelium.

Most squamous cell carcinomas are moderately to well differentiated (Fig. 14–12, B). Less common histologic variants include verrucous squamous cell carcinoma, spindle cell carcinoma, and basaloid squamous cell carcinoma. Regardless of histologic type, symptomatic tumors are generally very large at diagnosis and have already invaded the esophageal wall. The rich submucosal lymphatic network promotes circumferential and longitudinal spread, and intramural tumor nodules may be present several centimeters away from the principal mass. The sites of lymph node metastases vary with tumor location: Cancers in the upper third of the esophagus favor cervical lymph nodes; those in the middle third favor mediastinal, paratracheal, and tracheobronchial nodes; and those in the lower third spread to gastric and celiac nodes.

Clinical Features

Clinical manifestations of squamous cell carcinoma of the esophagus begin insidiously and include dysphagia, odynophagia (pain on swallowing), and obstruction. As with other forms of esophageal obstruction, patients may unwittingly adjust to the progressively increasing obstruction by altering their diet from solid to liquid foods. Extreme weight loss and debilitation result from both impaired nutrition and effects of the tumor itself. Hemorrhage and sepsis may accompany tumor ulceration. Occasionally, the first symptoms are caused by aspiration of food through a tracheoesophageal fistula.

Increased use of endoscopic screening has led to earlier detection of esophageal squamous cell carcinoma. The timing is critical, because 5-year survival rates are 75% for patients with superficial esophageal carcinoma but much lower for patients with more advanced tumors. Lymph node metastases, which are common, are associated with poor prognosis. The overall 5-year survival rate remains a dismal 9%.

![]() Summary

Summary

Diseases of the Esophagus

• Esophageal obstruction may occur as a result of mechanical or functional anomalies. Mechanical causes include developmental defects, fibrotic strictures, and tumors.

• Achalasia, characterized by incomplete LES relaxation, increased LES tone, and esophageal aperistalsis, is a common form of functional esophageal obstruction.

• Esophagitis can result from chemical or infectious mucosal injury. Infections are most frequent in immunocompromised persons.

• The most common cause of esophagitis is gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD), which must be differentiated from eosinophilic esophagitis.

• Barrett esophagus, which may develop in patients with chronic GERD, is associated with increased risk of esophageal adenocarcinoma.

• Esophageal squamous cell carcinoma is associated with alcohol and tobacco use, poverty, caustic esophageal injury, achalasia, tylosis, and Plummer-Vinson syndrome.

Stomach

Disorders of the stomach are a frequent cause of clinical disease, with inflammatory and neoplastic lesions being particularly common. In the United States, symptoms related to gastric acid account for nearly one third of all health care spending on gastrointestinal disease. In addition, despite a decreasing incidence in certain locales, including the United States, gastric cancer remains a leading cause of death worldwide.

The stomach is divided into four major anatomic regions: the cardia, fundus, body, and antrum. The cardia is lined mainly by mucin-secreting foveolar cells that form shallow glands. The antral glands are similar but also contain endocrine cells, such as G cells, that release gastrin to stimulate luminal acid secretion by parietal cells within the gastric fundus and body. The well-developed glands of the body and fundus also contain chief cells that produce and secrete digestive enzymes such as pepsin.

Inflammatory Disease of the Stomach

Acute Gastritis

Acute gastritis is a transient mucosal inflammatory process that may be asymptomatic or cause variable degrees of epigastric pain, nausea, and vomiting. In more severe cases there may be mucosal erosion, ulceration, hemorrhage, hematemesis, melena, or, rarely, massive blood loss.

![]() Pathogenesis

Pathogenesis

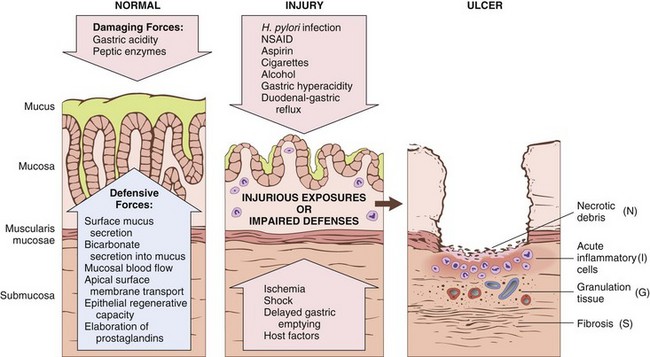

The gastric lumen is strongly acidic, with a pH close to one—more than a million times more acidic than the blood. This harsh environment contributes to digestion but also has the potential to damage the mucosa. Multiple mechanisms have evolved to protect the gastric mucosa (Fig. 14–13). Mucin secreted by surface foveolar cells forms a thin layer of mucus that prevents large food particles from directly touching the epithelium. The mucus layer also promotes formation of an “unstirred” layer of fluid over the epithelium that protects the mucosa and has a neutral pH as a result of bicarbonate ion secretion by surface epithelial cells. Finally, the rich vascular supply to the gastric mucosa delivers oxygen, bicarbonate, and nutrients while washing away acid that has back-diffused into the lamina propria. Acute or chronic gastritis can occur after disruption of any of these protective mechanisms. For example, reduced mucin synthesis in elderly persons is suggested to be one factor that explains their increased susceptibility to gastritis. Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) may interfere with cytoprotection normally provided by prostaglandins or reduce bicarbonate secretion, both of which increase the susceptibility of the gastric mucosa to injury. Ingestion of harsh chemicals, particularly acids or bases, either accidentally or as a suicide attempt, also results in severe gastric injury, predominantly as a consequence of direct damage to mucosal epithelial and stromal cells. Direct cellular injury also is implicated in gastritis due to excessive alcohol consumption, NSAIDs, radiation therapy, and chemotherapy.

Figure 14–13 Mechanisms of gastric injury and protection. This diagram illustrates the progression from more mild forms of injury to ulceration that may occur with acute or chronic gastritis. Ulcers include layers of necrotic debris (N), inflammation (I), and granulation tissue (G); a fibrotic scar (S), which develops over time, is present only in chronic lesions.

![]() Morphology

Morphology

On histologic examination, mild acute gastritis may be difficult to recognize, since the lamina propria shows only moderate edema and slight vascular congestion. The surface epithelium is intact, although scattered neutrophils may be present. Lamina propria lymphocytes and plasma cells are not prominent. The presence of neutrophils above the basement membrane—specifically, in direct contact with epithelial cells—is abnormal in all parts of the gastrointestinal tract and signifies active inflammation. With more severe mucosal damage, erosion, or loss of the superficial epithelium, may occur, leading to formation of mucosal neutrophilic infiltrates and purulent exudates. Hemorrhage also may occur, manifesting as dark puncta in an otherwise hyperemic mucosa. Concurrent presence of erosion and hemorrhage is termed acute erosive hemorrhagic gastritis.

Acute Peptic Ulceration

Focal, acute peptic injury is a well-known complication of therapy with NSAIDs as well as severe physiologic stress. Such lesions include

• Stress ulcers, most commonly affecting critically ill patients with shock, sepsis, or severe trauma

• Curling ulcers, occurring in the proximal duodenum and associated with severe burns or trauma

• Cushing ulcers, arising in the stomach, duodenum, or esophagus of persons with intracranial disease, have a high incidence of perforation

![]() Pathogenesis

Pathogenesis

The pathogenesis of acute ulceration is complex and incompletely understood. NSAID-induced ulcers are caused by direct chemical irritation as well as cyclooxygenase inhibition, which prevents prostaglandin synthesis. This eliminates the protective effects of prostaglandins, which include enhanced bicarbonate secretion and increased vascular perfusion. Lesions associated with intracranial injury are thought to be caused by direct stimulation of vagal nuclei, which causes gastric acid hypersecretion. Systemic acidosis, a frequent finding in critically ill patients, also may contribute to mucosal injury by lowering the intracellular pH of mucosal cells. Hypoxia and reduced blood flow caused by stress-induced splanchnic vasoconstriction also contribute to acute ulcer pathogenesis.

![]() Morphology

Morphology

Lesions described as acute gastric ulcers range in depth from shallow erosions caused by superficial epithelial damage to deeper lesions that penetrate the mucosa. Acute ulcers are rounded and typically are less than 1 cm in diameter. The ulcer base frequently is stained brown to black by acid-digested extravasated red cells, in some cases associated with transmural inflammation and local serositis. While these lesions may occur singly, more often multiple ulcers are present within the stomach and duodenum. Acute stress ulcers are sharply demarcated, with essentially normal adjacent mucosa, although there may be suffusion of blood into the mucosa and submucosa and some inflammatory reaction. The scarring and thickening of blood vessels that characterize chronic peptic ulcers are absent. Healing with complete reepithelialization occurs days or weeks after the injurious factors are removed.

Clinical Features

Symptoms of gastric ulcers include nausea, vomiting, and coffee-ground hematemesis. Bleeding from superficial gastric erosions or ulcers that may require transfusion develops in 1% to 4% of these patients. Other complications, including perforation, can also occur. Proton pump inhibitors, or the less frequently used histamine H2 receptor antagonists, may blunt the impact of stress ulceration, but the most important determinant of outcome is the severity of the underlying condition.

Chronic Gastritis

The symptoms and signs associated with chronic gastritis typically are less severe but more persistent than those of acute gastritis. Nausea and upper abdominal discomfort may occur, sometimes with vomiting, but hematemesis is uncommon. The most common cause of chronic gastritis is infection with the bacillus Helicobacter pylori. Autoimmune gastritis, the most common cause of atrophic gastritis, represents less than 10% of cases of chronic gastritis and is the most common form of chronic gastritis in patients without H. pylori infection. Less common causes include radiation injury and chronic bile reflux.

Helicobacter pylori Gastritis

The discovery of the association of H. pylori with peptic ulcer disease revolutionized the understanding of chronic gastritis. These spiral-shaped or curved bacilli are present in gastric biopsy specimens from almost all patients with duodenal ulcers and a majority of those with gastric ulcers or chronic gastritis. Acute H. pylori infection does not produce sufficient symptoms to require medical attention in most cases; rather the chronic gastritis ultimately causes the afflicted person to seek treatment. H. pylori organisms are present in 90% of patients with chronic gastritis affecting the antrum. In addition, the increased acid secretion that occurs in H. pylori gastritis may result in peptic ulcer disease of the stomach or duodenum; H. pylori infection also confers increased risk of gastric cancer.

Epidemiology

In the United States, H. pylori infection is associated with poverty, household crowding, limited education, African American or Mexican American ethnicity, residence in areas with poor sanitation, and birth outside of the United States. Colonization rates exceed 70% in some groups and range from less than 10% to more than 80% worldwide. In high-prevalence areas, infection often is acquired in childhood and then persists for decades. Thus, the incidence of H. pylori infection correlates most closely with sanitation and hygiene during an individual’s childhood.

![]() Pathogenesis

Pathogenesis

H. pylori infection most often manifests as a predominantly antral gastritis with high acid production, despite hypogastrinemia. The risk of duodenal ulcer is increased in these patients, and in most cases, gastritis is limited to the antrum.

H. pylori organisms have adapted to the ecologic niche provided by gastric mucus. Although H. pylori may invade the gastric mucosa, the contribution of invasion to disease pathogenesis is not known. Four features are linked to H. pylori virulence:

• Flagella, which allow the bacteria to be motile in viscous mucus

• Urease, which generates ammonia from endogenous urea, thereby elevating local gastric pH around the organisms and protecting the bacteria from the acidic pH of the stomach

• Adhesins, which enhance bacterial adherence to surface foveolar cells

• Toxins, such as that encoded by cytotoxin-associated gene A (CagA), that may be involved in ulcer or cancer development by poorly defined mechanisms

These factors allow H. pylori to create an imbalance between gastroduodenal mucosal defenses and damaging forces that overcome those defenses. Over time, chronic antral H. pylori gastritis may progress to pangastritis, resulting in multifocal atrophic gastritis, reduced acid secretion, intestinal metaplasia, and increased risk of gastric adenocarcinoma in a subset of patients. The underlying mechanisms contributing to this progression are not clear, but interactions between the host immune system and the bacterium seem to be critical.

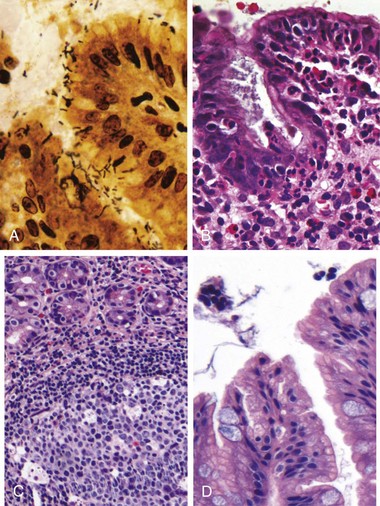

![]() Morphology

Morphology

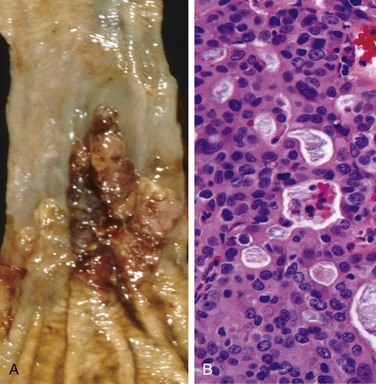

Gastric biopsy specimens generally demonstrate H. pylori in infected persons (Fig. 14–14, A). The organism is concentrated within the superficial mucus overlying epithelial cells in the surface and neck regions. The inflammatory reaction includes a variable number of neutrophils within the lamina propria, including some that cross the basement membrane to assume an intraepithelial location (Fig. 14–14, B) and accumulate in the lumen of gastric pits to create pit abscesses. The superficial lamina propria includes large numbers of plasma cells, often in clusters or sheets, as well as increased numbers of lymphocytes and macrophages. When intense, inflammatory infiltrates may create thickened rugal folds, mimicking infiltrative lesions. Lymphoid aggregates, some with germinal centers, frequently are present (Fig. 14–14, C) and represent an induced form of mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue (MALT) that has the potential to transform into lymphoma. Intestinal metaplasia, characterized by the presence of goblet cells and columnar absorptive cells (Fig. 14–14, D), also may be present and is associated with increased risk of gastric adenocarcinoma. H. pylori shows tropism for gastric foveolar epitheleum and generally is not found in areas of intestinal metaplasia, acid-producing mucosa of the gastric body, or duodenal epithelium. Thus, an antral biopsy is preferred for evaluation of H. pylori gastritis.

Figure 14–14 Chronic gastritis. A, Spiral-shaped Helicobacter pylori bacilli are highlighted in this Warthin-Starry silver stain. Organisms are abundant within surface mucus. B, Intraepithelial and lamina propria neutrophils are prominent. C, Lymphoid aggregates with germinal centers and abundant subepithelial plasma cells within the superficial lamina propria are characteristic of H. pylori gastritis. D, Intestinal metaplasia, recognizable as the presence of goblet cells admixed with gastric foveolar epithelium, can develop and is a risk factor for development of gastric adenocarcinoma.

Clinical Features

In addition to histologic identification of the organism, several diagnostic tests have been developed including a noninvasive serologic test for anti–H. pylori antibodies, fecal bacterial detection, and the urea breath test based on the generation of ammonia by bacterial urease. Gastric biopsy specimens also can be analyzed by the rapid urease test, bacterial culture, or polymerase chain reaction (PCR) assay for bacterial DNA. Effective treatments include combinations of antibiotics and proton pump inhibitors. Patients with H. pylori gastritis usually improve after treatment, although relapses can follow incomplete eradication or reinfection.

Autoimmune Gastritis

Autoimmune gastritis accounts for less than 10% of cases of chronic gastritis. In contrast with that caused by H. pylori, autoimmune gastritis typically spares the antrum and induces hypergastrinemia (Table 14–2). Autoimmune gastritis is characterized by

• Antibodies to parietal cells and intrinsic factor that can be detected in serum and gastric secretions

• Reduced serum pepsinogen I levels

Table 14–2 Characteristics of Helicobacter pylori–Associated and Autoimmune Gastritis

| Feature | Location | |

|---|---|---|

| H. pylori–Associated: Antrum | Autoimmune: Body | |

| Inflammatory infiltrate | Neutrophils, subepithelial plasma cells | Lymphocytes, macrophages |

| Acid production | Increased to slightly decreased | Decreased |

| Gastrin | Normal to decreased | Increased |

| Other lesions | Hyperplastic/inflammatory polyps | Neuroendocrine hyperplasia |

| Serology | Antibodies to H. pylori | Antibodies to parietal cells (H+,K+-ATPase, intrinsic factor) |

| Sequelae | Peptic ulcer, adenocarcinoma, lymphoma | Atrophy, pernicious anemia, adenocarcinoma, carcinoid tumor |

| Associations | Low socioeconomic status, poverty, residence in rural areas | Autoimmune disease; thyroiditis, diabetes mellitus, Graves disease |

![]() Pathogenesis

Pathogenesis

Autoimmune gastritis is associated with loss of parietal cells, which secrete acid and intrinsic factor. Deficient acid production stimulates gastrin release, resulting in hypergastrinemia and hyperplasia of antral gastrin-producing G cells. Lack of intrinsic factor disables ileal vitamin B12 absorption, leading to B12 deficiency and megaloblastic anemia (pernicious anemia); reduced serum concentration of pepsinogen I reflects chief cell loss. Although H. pylori can cause hypochlorhydria, it is not associated with achlorhydria or pernicious anemia, because the parietal and chief cell damage is not as severe as in autoimmune gastritis.

![]() Morphology

Morphology

Autoimmune gastritis is characterized by diffuse damage of the oxyntic (acid-producing) mucosa within the body and fundus. Damage to the antrum and cardia typically is absent or mild. With diffuse atrophy, the oxyntic mucosa of the body and fundus appears markedly thinned, and rugal folds are lost. Neutrophils may be present, but the inflammatory infiltrate more commonly is composed of lymphocytes, macrophages, and plasma cells; in contrast with H. pylori gastritis, the inflammatory reaction most often is deep and centered on the gastric glands. Parietal and chief cell loss can be extensive, and intestinal metaplasia may develop.

Clinical Features

Antibodies to parietal cells and intrinsic factor are present early in disease, but pernicious anemia develops in only a minority of patients. The median age at diagnosis is 60 years, and there is a slight female predominance. Autoimmune gastritis often is associated with other autoimmune diseases but is not linked to specific human leukocyte antigen (HLA) alleles.

Peptic Ulcer Disease

Peptic ulcer disease (PUD) most often is associated with H. pylori infection or NSAID use. In the US, the latter is becoming the most common cause of gastric ulcers as H. pylori infection rates fall and low-dose aspirin use in the aging population increases. PUD may occur in any portion of the gastrointestinal tract exposed to acidic gastric juices but is most common in the gastric antrum and first portion of the duodenum. PUD also may occur in the esophagus as a result of GERD or acid secretion by ectopic gastric mucosa, and in the small intestine secondary to gastric heteropia within a Meckel diverticulum.

Epidemiology

PUD is common and is a frequent cause of physician visits worldwide. It leads to treatment of over 3 million people, 190,000 hospitalizations, and 5000 deaths in the United States each year. The lifetime risk of developing an ulcer is approximately 10% for males and 4% for females.

![]() Pathogenesis

Pathogenesis

H. pylori infection and NSAID use are the primary underlying causes of PUD. The imbalances of mucosal defenses and damaging forces that cause chronic gastritis (Fig. 14–13) are also responsible for PUD. Thus, PUD generally develops on a background of chronic gastritis. Although more than 70% of PUD cases are associated with H. pylori infection, only 5% to 10% of H. pylori–infected persons develop ulcers. It is probable that host factors as well as variation among H. pylori strains determine the clinical outcomes.

Gastric hyperacidity is fundamental to the pathogenesis of PUD. The acidity that drives PUD may be caused by H. pylori infection, parietal cell hyperplasia, excessive secretory responses, or impaired inhibition of stimulatory mechanisms such as gastrin release. For example, Zollinger-Ellison syndrome, characterized by multiple peptic ulcerations in the stomach, duodenum, and even jejunum, is caused by uncontrolled release of gastrin by a tumor and the resulting massive acid production. Cofactors in peptic ulcerogenesis include chronic NSAID use, as noted; cigarette smoking, which impairs mucosal blood flow and healing; and high-dose corticosteroids, which suppress prostaglandin synthesis and impair healing. Peptic ulcers are more frequent in persons with alcoholic cirrhosis, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, chronic renal failure, and hyperparathyroidism. In the latter two conditions, hypercalcemia stimulates gastrin production and therefore increases acid secretion. Finally, psychologic stress may increase gastric acid production and exacerbate PUD.

![]() Morphology

Morphology

Peptic ulcers are four times more common in the proximal duodenum than in the stomach. Duodenal ulcers usually occur within a few centimeters of the pyloric valve and involve the anterior duodenal wall. Gastric peptic ulcers are predominantly located near the interface of the body and antrum.

Peptic ulcers are solitary in more than 80% of patients. Lesions less than 0.3 cm in diameter tend to be shallow, whereas those over 0.6 cm are likely to be deeper. The classic peptic ulcer is a round to oval, sharply punched-out defect (Fig. 14–15, A). The base of peptic ulcers is smooth and clean as a result of peptic digestion of exudate and on histologic examination is composed of richly vascular granulation tissue (Fig. 14–15, B). Ongoing bleeding within the ulcer base may cause life-threatening hemorrhage. Perforation is a complication that demands emergent surgical intervention.

Clinical Features

Peptic ulcers are chronic, recurring lesions that occur most often in middle-aged to older adults without obvious precipitating conditions, other than chronic gastritis. A majority of peptic ulcers come to clinical attention after patient complaints of epigastric burning or aching pain, although a significant fraction manifest with complications such as iron deficiency anemia, frank hemorrhage, or perforation. The pain tends to occur 1 to 3 hours after meals during the day, is worse at night, and is relieved by alkali or food. Nausea, vomiting, bloating, and belching may be present. Healing may occur with or without therapy, but the tendency to develop ulcers later remains.

A variety of surgical approaches formerly were used to treat PUD, but current therapies are aimed at H. pylori eradication with antibiotics and neutralization of gastric acid, usually through use of proton pump inhibitors. These efforts have markedly reduced the need for surgical management, which is reserved primarily for treatment of bleeding or perforated ulcers. PUD causes much more morbidity than mortality.

![]() Summary

Summary

Acute and Chronic Gastritis

• The spectrum of acute gastritis ranges from asymptomatic disease to mild epigastric pain, nausea, and vomiting. Causative factors include any agent or disease that interferes with gastric mucosal protection. Acute gastritis can progress to acute gastric ulceration.

• The most common cause of chronic gastritis is H. pylori infection; most remaining cases are caused by autoimmune gastritis.

• H. pylori gastritis typically affects the antrum and is associated with increased gastric acid production. The induced mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue (MALT) can transform into lymphoma.

• Autoimmune gastritis causes atrophy of the gastric body oxyntic glands, which results in decreased gastric acid production, antral G cell hyperplasia, achlorhydria, and vitamin B12 deficiency. Anti-parietal cell and anti–intrinsic factor antibodies typically are present.

• Intestinal metaplasia develops in both forms of chronic gastritis and is a risk factor for development of gastric adenocarcinoma.

• Peptic ulcer disease can be caused by H. pylori chronic gastritis and the resultant hyperchlorhydria or NSAID use. Ulcers can develop in the stomach or duodenum and usually heal after suppression of gastric acid production and, if present, eradication of the H. pylori.

Neoplastic Disease of the Stomach

Gastric Polyps

Polyps, nodules or masses that project above the level of the surrounding mucosa, are identified in up to 5% of upper gastrointestinal tract endoscopies. Polyps may develop as a result of epithelial or stromal cell hyperplasia, inflammation, ectopia, or neoplasia. Although many different types of polyps can occur in the stomach, only hyperplastic and inflammatory polyps, fundic gland polyps, and adenomas are considered here.

Inflammatory and Hyperplastic Polyps

Approximately 75% of all gastric polyps are inflammatory or hyperplastic polyps. They most commonly affect persons between 50 and 60 years of age, usually arising in a background of chronic gastritis that initiates the injury and reactive hyperplasia that cause polyp growth. If associated with H. pylori gastritis, polyps may regress after bacterial eradication.

![]() Morphology

Morphology