Chapter 17 Male Genital System and Lower Urinary Tract

See Targeted Therapy available online at studentconsult.com

Penis

Malformations

The most common malformations of the penis include abnormalities in the location of the distal urethral orifice, termed hypospadias and epispadias. In hypospadias, the more common of the two conditions, the abnormal opening of the urethra is on the ventral aspect of the penis anywhere along the shaft. This anomalous urethral orifice is sometimes constricted, resulting in urinary tract obstruction and an increased risk for urinary tract infections. The abnormality occurs in 1 in 300 live male births and may be associated with other congenital anomalies, such as inguinal hernia and undescended testis. In epispadias, the abnormal urethral orifice is on the dorsal aspect of the penis.

Inflammatory Lesions

Balanitis and balanoposthitis refer to local inflammation of the glans penis and of the overlying prepuce, respectively. Among the more common agents are Candida albicans, anaerobic bacteria, Gardnerella, and pyogenic bacteria. Most cases occur as a consequence of poor local hygiene in uncircumcised males, with accumulations of desquamated epithelial cells, sweat, and debris, termed smegma, acting as a local irritant. Phimosis represents a condition in which the prepuce cannot be retracted easily over the glans penis. Although phimosis may occur as a congenital anomaly, most cases are acquired from scarring of the prepuce secondary to previous episodes of balanoposthitis.

Neoplasms

More than 95% of penile neoplasms arise on squamous epithelium. In the United States, squamous cell carcinomas of the penis are relatively uncommon, accounting for about 0.4% of all cancers in males. In developing countries, however, penile carcinoma occurs at much higher rates. Most cases occur in uncircumcised patients older than 40 years of age. Several factors have been implicated in the pathogenesis of squamous cell carcinoma of the penis, including poor hygiene (with resultant exposure to potential carcinogens in smegma), smoking, and infection with human papillomavirus (HPV), particularly types 16 and 18.

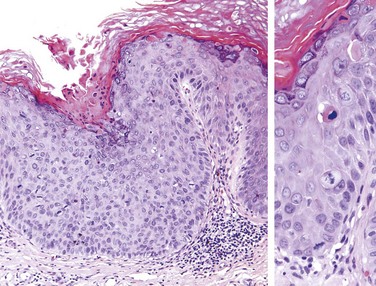

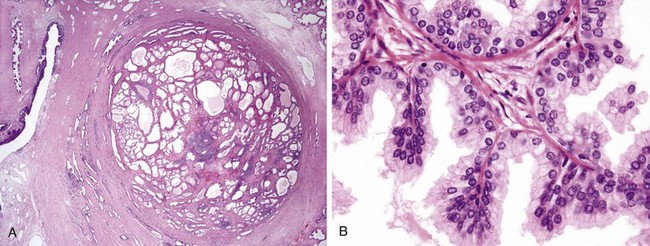

Squamous cell carcinoma in situ of the penis (Bowen disease) occurs in older uncircumcised males and appears grossly as a solitary plaque on the shaft of the penis. Histologic examination reveals morphologically malignant cells throughout the epidermis with no invasion of the underlying stroma (Fig. 17–1). It gives rise to infiltrating squamous cell carcinoma in approximately 10% of patients.

Figure 17–1 Carcinoma in situ (Bowen disease) of the penis. The epithelium above the intact basement membrane shows delayed maturation and disorganization (left). Higher magnification (right) shows several mitotic figures, some above the basal layer, a dyskeratotic cell, and nuclear pleomorphism.

Invasive squamous cell carcinoma of the penis appears as a gray, crusted, papular lesion, most commonly on the glans penis or prepuce. In many cases, infiltration of the underlying connective tissue produces an indurated, ulcerated lesion with irregular margins (Fig. 17–2). Histologically, it is a typical keratinizing squamous cell carcinoma. The prognosis is related to the stage of the tumor. With localized lesions, the 5-year survival rate is 66%, whereas metastasis to inguinal lymph nodes carries a grim 27% 5-year survival rate. Verrucous carcinoma is a variant of squamous cell carcinoma characterized by a papillary architecture, virtually no cytologic atypia, and rounded, pushing deep margins. Verrucous carcinomas are locally invasive but do not metastasize.

![]() Summary

Summary

Lesions of the Penis

• Squamous cell carcinoma and its precursor lesions are the most important penile lesions. Many are associated with HPV infection.

• Squamous cell carcinoma occurs on the glans or shaft of the penis as an ulcerated infiltrative lesion that may spread to inguinal nodes and infrequently to distant sites. Most cases occur in uncircumcised males.

• Other important penile disorders include congenital abnormalities involving the position of the urethra (epispadias, hypospadias) and inflammatory disorders (balanitis, phimosis).

Scrotum, Testis, and Epididymis

The skin of the scrotum may be affected by several inflammatory processes, including local fungal infections and systemic dermatoses. Neoplasms of the scrotal sac are unusual. Squamous cell carcinoma, the most common of these, is of historical interest in that it represents the first human malignancy associated with environmental influences, dating from Sir Percival Pott’s observation of a high incidence of the disease in chimney sweeps. The subsequent edict by the Chimney Sweeps Guild that its members must bathe daily remains one of the most successful public health measures for cancer prevention. Several disorders unrelated to the testes and epididymis may also present as scrotal enlargement. Hydrocele, the most common cause of scrotal enlargement, is caused by an accumulation of serous fluid within the tunica vaginalis. It may arise in response to neighboring infections or tumors, or it may be idiopathic. It is readily distinguished from collections of pus, lymph, and blood by allowing a beam of light to pass through (transluminescence). Accumulation of blood or lymphatic fluid within the tunica vaginalis, termed hematoceles and chyloceles, respectively, also may cause testicular enlargement. In extreme cases of lymphatic obstruction, caused, for example, by filariasis, the scrotum and the lower extremities may enlarge to grotesque sizes—a condition termed elephantiasis.

Cryptorchidism and Testicular Atrophy

Cryptorchidism represents a failure of testicular descent into the scrotum. Normally, the testes descend from the abdominal cavity into the pelvis by the third month of gestation and then through the inguinal canals into the scrotum during the last 2 months of intrauterine life. The diagnosis of cryptorchidism is only established with certainty after the age of 1 year, particularly in premature infants, because testicular descent into the scrotum is not always complete at birth. By 1 year of age, cryptorchidism affects 1% of the male population. The condition is bilateral in approximately 10% of affected patients. In the vast majority of cases, the cause of the cryptorchidism is unknown. Because undescended testes become atrophic, bilateral cryptorchidism causes sterility. However, even unilateral cryptorchidism may be associated with atrophy of the contralateral descended gonad and therefore may also lead to sterility. In addition to infertility, failure of descent is associated with a 3- to 5-fold increased risk of testicular cancer. Patients with unilateral cryptorchidism are also at increased risk for the development of cancer in the contralateral, normally descended testis, suggesting that some intrinsic abnormality, rather than simple failure of descent, is responsible for the increased cancer risk. Surgical placement of the undescended testis into the scrotum (orchiopexy) before puberty decreases the likelihood of testicular atrophy and reduces but does not eliminate the risk of cancer and infertility.

The cryptorchid testis may be of normal size early in life, but some degree of atrophy usually is present by the onset of puberty. Microscopic evidence of tubular atrophy is evident by the age of 5 to 6 years, and hyalinization is present by the time of puberty. Foci of intratubular germ cell neoplasia (discussed later), may be present in cryptorchid testes and are likely precursors of subsequent germ cell tumors. Atrophic changes similar to those in cryptorchid testes may be caused by several other insults, including chronic ischemia, trauma, irradiation, and antineoplastic chemotherapy, as well as conditions associated with chronically elevated estrogen levels (e.g., cirrhosis). Intratubular germ cell neoplasia is not a feature of these conditions, however.

![]() Summary

Summary

Cryptorchidism

• Cryptorchidism refers to incomplete descent of the testis from the abdomen to the scrotum and is present in about 1% of 1-year-old male infants.

• Bilateral or, in some cases, even unilateral cryptorchidism is associated with tubular atrophy and sterility.

• The cryptorchid testis carries a 3- to 5-fold higher risk for testicular cancer, which arises from foci of intratubular germ cell neoplasia within the atrophic tubules. Orchiopexy reduces the risk of sterility and cancer.

Inflammatory Lesions

Inflammatory lesions of the testis are more common in the epididymis than in the testis proper. Some of the more important inflammatory disorders are sexually transmitted and are discussed later in the chapter. Other causes of testicular inflammation include nonspecific epididymitis and orchitis, mumps, and tuberculosis. Nonspecific epididymitis and orchitis usually begin as a primary urinary tract infection that then spreads to the testis through the vas deferens or the lymphatics of the spermatic cord. The involved testis typically is swollen and tender, and histologic examination reveals a predominantly neutrophilic inflammatory infiltrate. Orchitis complicates mumps infection in roughly 20% of infected adult males but rarely occurs in children. Affected testes are edematous and congested, and contain a predominantly lymphoplasmacytic inflammatory infiltrate. Severe mumps orchitis may lead to extensive necrosis, loss of seminiferous epithelium, tubular atrophy, fibrosis, and sterility. Several conditions, including infections and autoimmune injury, may elicit granulomatous inflammation in the testis. Of these, tuberculosis is the most common. Testicular tuberculosis generally begins as an epididymitis, with secondary involvement of the testis. Histologically, there is granulomatous inflammation and caseous necrosis identical to that seen in active tuberculosis in other sites.

Vascular Disturbances

Torsion, or twisting of the spermatic cord, typically results in obstruction of testicular venous drainage while leaving the thick-walled and more resilient arteries patent, so that intense vascular engorgement and venous infarction follow unless the torsion is relieved. There are two types of testicular torsion. Neonatal torsion occurs either in utero or shortly after birth. It lacks any associated anatomic defect to account for its occurrence. Adult torsion typically is seen in adolescence and manifests with sudden onset of testicular pain. In contrast with neonatal torsion, adult torsion results from a bilateral anatomic defect whereby the testis has increased mobility, giving rise to the so-called bell clapper abnormality. It often occurs without any inciting injury; sudden pain heralding the torsion may even awaken the patient from sleep.

Torsion constitutes one of the few urologic emergencies. If the testis is explored surgically and the cord can be manually untwisted within approximately 6 hours, there is a good chance that the testis will remain viable. To prevent the catastrophic occurrence of torsion in the contralateral testis, the unaffected testis typically is surgically fixed within the scrotum (orchiopexy).

Testicular Neoplasms

Testicular neoplasms occur in roughly 6 per 100,000 males. In the 15- to 34-year-old age group, when these neoplasms peak in incidence, they are the most common tumors of men. Tumors of the testis are a heterogeneous group of neoplasms that include germ cell tumors and sex cord–stromal tumors. In postpubertal males, 95% of testicular tumors arise from germ cells, and all are malignant. By contrast, neoplasms derived from Sertoli or Leydig cells (sex cord–stromal tumors) are uncommon and usually benign. The focus of the remainder of this discussion is on testicular germ cell tumors.

The cause of testicular neoplasms remains unknown. Testicular tumors are more common in whites than in blacks, and the incidence has increased in white populations over recent decades. As noted previously, cryptorchidism is associated with a three- to five-fold increase in the risk of cancer in the undescended testis, as well as an increased risk of cancer in the contralateral descended testis. A history of cryptorchidism is present in approximately 10% of cases of testicular cancer. Intersex syndromes, including androgen insensitivity syndrome and gonadal dysgenesis, also are associated with an increased frequency of testicular cancer. Family history is important, because brothers of males with germ cell tumors have an 8- to 10-fold increased risk over that of the population at large, presumably owing to inherited risk factors. The development of cancer in one testis is associated with a markedly increased risk of neoplasia in the contralateral testis. An isochromosome of the short arm of chromosome 12, i(12p), is found in virtually all germ cell tumors, regardless of their histologic type. The gene(s) that are dysregulated by this chromosomal abnormality, as well as the other mutations that contribute to the molecular pathogenesis of germ cell tumors, are an area of ongoing research.

Most testicular tumors in postpubertal males arise from the in situ lesion intratubular germ cell neoplasia. This lesion is present in conditions associated with a high risk of developing germ cell tumors (e.g., cryptorchidism, dysgenetic gonads). These in situ lesions can be found in grossly “normal” testicular tissue adjacent to germ cell tumors in virtually all cases.

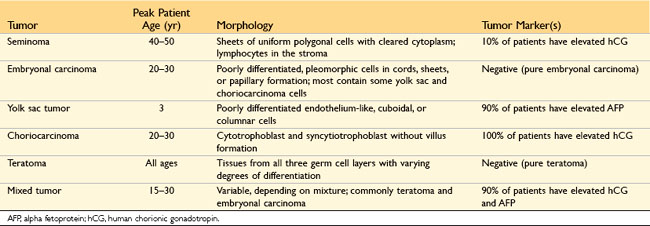

Testicular germ cell tumors are subclassified into seminomas and nonseminomatous germ cell tumors (Table 17–1). Seminomas, sometimes referred to as “classic” seminomas to distinguish them from the less common spermatocytic seminoma (discussed further on), account for about 50% of testicular germ cell neoplasms. They are histologically identical to ovarian dysgerminomas and to germinomas occurring in the central nervous system and other extragonadal sites.

![]() Morphology

Morphology

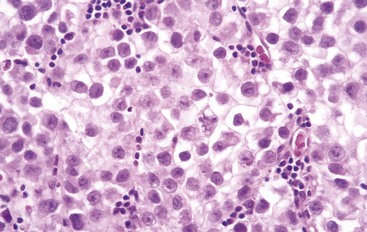

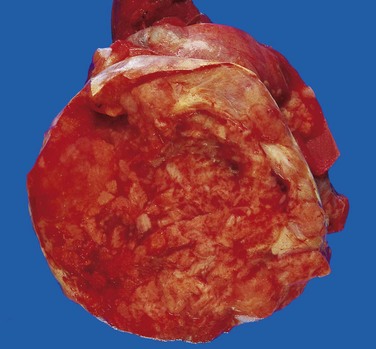

The histologic appearances of germ cell tumors may be pure (i.e., composed of a single histologic type) or mixed (seen in 40% of cases). Seminomas are soft, well-demarcated, gray-white tumors that bulge from the cut surface of the affected testis (Fig. 17–3). Large tumors may contain foci of coagulation necrosis, usually without hemorrhage. Microscopically, seminomas are composed of large, uniform cells with distinct cell borders, clear, glycogen-rich cytoplasm, and round nuclei with conspicuous nucleoli (Fig. 17–4). The cells often are arrayed in small lobules with intervening fibrous septa. A lymphocytic infiltrate usually is present and may, on occasion, overshadow the neoplastic cells. Seminomas may also be accompanied by an ill-defined granulomatous reaction. In approximately 15% of cases, syncytiotrophoblasts are present that are the source of the minimally elevated serum hCG concentrations encountered in some males with pure seminoma. Their presence has no bearing on prognosis.

Figure 17–3 Seminoma of the testis appearing as a well-circumscribed, pale, fleshy, homogeneous mass.

Figure 17–4 Seminoma of the testis. Microscopic examination reveals large cells with distinct cell borders, pale nuclei, prominent nucleoli, and a sparse lymphocytic infiltrate.

Although related by name to seminoma, spermatocytic seminoma is a distinct clinical and histologic entity. This is an uncommon tumor. It occurs in much older individuals than other testicular tumors; affected patients generally are older than 65 years of age. In contrast with classic seminomas, spermatocytic seminomas lack lymphocytic infiltrates, granulomas, and syncytiotrophoblasts; are not admixed with other germ cell tumor histologies; are not associated with intratubular germ cell neoplasia; and do not metastasize. The tumor usually comprises polygonal cells of variable size that are arranged in nodules or sheets.

Embryonal carcinomas are ill-defined, invasive masses containing foci of hemorrhage and necrosis (Fig. 17–5). The primary lesions may be small, even in patients with systemic metastases. The tumor cells are large and primitive-looking, with basophilic cytoplasm, indistinct cell borders, and large nuclei with prominent nucleoli. The neoplastic cells may be arrayed in undifferentiated, solid sheets or may contain primitive glandular structures and irregular papillae (Fig. 17–6). In most cases, cells characteristic of other germ cell tumors (e.g., yolk sac tumor, teratoma, choriocarcinoma) are admixed with the embryonal areas. Pure embryonal carcinomas account for only 2% to 3% of all testicular germ cell tumors.

Figure 17–5 Embryonal carcinoma. In contrast with the seminoma illustrated in Figure 17–3, this tumor is a hemorrhagic mass.

Figure 17–6 Embryonal carcinoma. Note the sheets of undifferentiated cells and primitive gland-like structures. The nuclei are large and hyperchromatic.

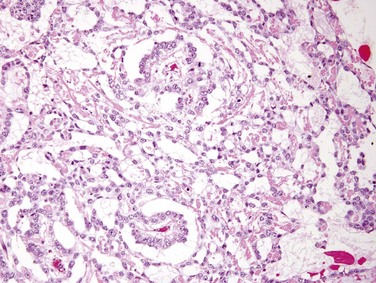

Yolk sac tumors are the most common primary testicular neoplasm in children younger than 3 years of age; in this age group it has a very good prognosis. In adults, yolk sac tumors most often are seen admixed with embryonal carcinoma. On gross inspection, these tumors often are large and may be well demarcated. Histologic examination discloses low cuboidal to columnar epithelial cells forming microcysts, lacelike (reticular) patterns, sheets, glands, and papillae (Fig. 17–7). A distinctive feature is the presence of structures resembling primitive glomeruli, the so-called Schiller-Duvall bodies. Tumors often have eosinophilic hyaline globules in which α1-antitrypsin and alpha fetoprotein (AFP) can be demonstrated by immunohistochemical techniques. As mentioned later, AFP can also be detected in the serum.

Figure 17–7 Yolk sac tumor demonstrating areas of loosely textured, microcystic tissue and papillary structures resembling a developing glomerulus (Schiller-Duval bodies).

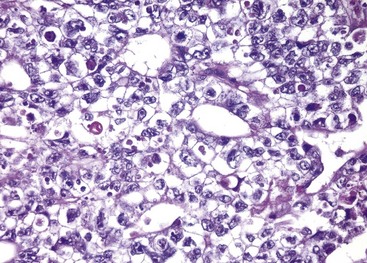

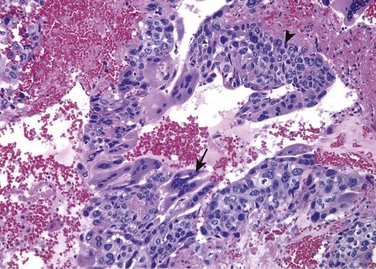

Choriocarcinomas are tumors in which the pluripotential neoplastic germ cells differentiate along trophoblastic lines. Grossly, the primary tumors often are small, nonpalpable lesions, even those with extensive systemic metastases. Microscopic examination reveals that choriocarcinomas are composed of sheets of small cuboidal cells irregularly intermingled with or capped by large, eosinophilic syncytial cells containing multiple dark, pleomorphic nuclei; these represent cytotrophoblastic and syncytiotrophoblastic differentiation, respectively (Fig. 17–8). HCG within syncytiotrophoblasts can be identified by immunohistochemical staining and is elevated in the serum.

Figure 17–8 Choriocarcinoma. Both cytotrophoblastic cells with central nuclei (arrowhead, upper right) and syncytiotrophoblastic cells with multiple dark nuclei embedded in eosinophilic cytoplasm (arrow, middle) are present. Hemorrhage and necrosis are prominent.

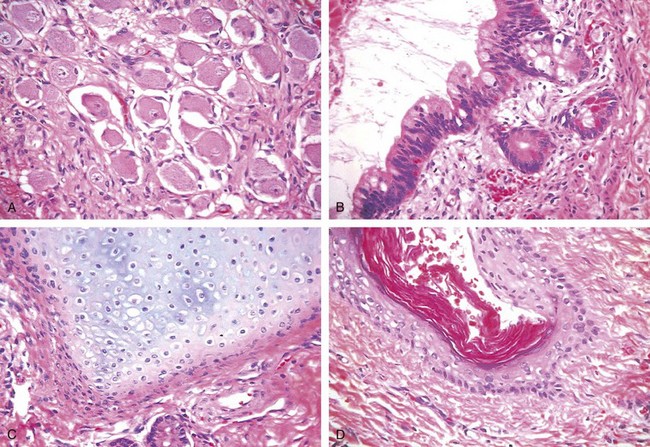

Teratomas are tumors in which the neoplastic germ cells differentiate along somatic cell lines. These tumors form firm masses that on cut surface often contain cysts and recognizable areas of cartilage. They may occur at any age from infancy to adult life. Pure forms of teratoma are fairly common in infants and children, being second in frequency only to yolk sac tumors. In adults, pure teratomas are rare, constituting 2% to 3% of germ cell tumors, and as with embryonal carcinomas, most are seen in combination with other histologic types. Teratomas are composed of a heterogeneous, helter-skelter collection of differentiated cells or organoid structures, such as neural tissue, muscle bundles, islands of cartilage, clusters of squamous epithelium, structures reminiscent of thyroid gland, bronchial epithelium, and bits of intestinal wall or brain substance, all embedded in a fibrous or myxoid stroma (Fig. 17–9). Elements may be mature (resembling various tissues within the adult) or immature (sharing histologic features with fetal or embryonal tissues). In prepubertal males, teratomas are typically benign, whereas teratomas in postpubertal males are malignant, being capable of metastasis regardless of whether they are composed of mature or immature elements.

Figure 17–9 Teratoma. Testicular teratomas contain mature cells from endodermal, mesodermal, and ectodermal lines. A–D, Four different fields from the same tumor specimen contain neural (ectodermal) (A), glandular (endodermal) (B), cartilaginous (mesodermal) (C), and squamous epithelial (D) elements.

Dermoid cysts and epidermoid cysts, common in the ovary (Chapter 18), are rare in the testis. These tumors should not be considered teratomas since they are uniformly benign regardless of the patient’s age.

Rarely, non–germ cell tumors may arise in teratoma—a phenomenon referred to as “teratoma with malignant transformation.” These neoplasms may take the form of a focus of squamous cell carcinoma, mucin-secreting adenocarcinoma, or sarcoma. The importance of non–germ cell malignancies arising in a teratoma is that when the non–germ cell component spreads outside of the testis it does not respond to chemotherapy; thus, the only hope for cure resides in the local resectability of the metastases.

Clinical Features

Patients with testicular germ cell neoplasms present most frequently with a painless testicular mass that (unlike enlargements caused by hydroceles) is non-translucent. Biopsy of a testicular neoplasm is associated with a risk of tumor spillage, which would necessitate excision of the scrotal skin in addition to orchiectomy. Consequently, the standard management of a solid testicular mass is radical orchiectomy, based on the presumption of malignancy. Some tumors, especially nonseminomatous germ cell neoplasms, may have metastasized widely by the time of diagnosis in the absence of a palpable testicular lesion.

Seminomas and nonseminomatous tumors differ in their behavior and clinical course. Seminomas often remain confined to the testis for long intervals and may reach considerable size before diagnosis. Metastases most commonly are encountered in the iliac and paraaortic lymph nodes, particularly in the upper lumbar region. Hematogenous metastases occur late in the course of the disease. By contrast, nonseminomatous germ cell neoplasms tend to metastasize earlier, by lymphatic as well as hematogenous routes. Hematogenous metastases are most common in the liver and lungs. Metastatic lesions may be identical to the primary testicular tumor or may contain elements of other germ cell tumors.

Assay of tumor markers secreted by germ cell tumors is important in two ways; these markers (summarized in Table 17–1 along with some salient clinical and morphologic features) are helpful diagnostically, but have an even more valuable role in following the response of tumors to therapy after the diagnosis is established. Human chorionic gonadotropin (hCG) is always elevated in patients with choriocarcinoma and, as noted, can be minimally elevated in persons with other germ cell tumors containing syncytiotrophoblastic cells without cytotrophoblasts. Increased alpha fetoprotein (AFP) in the setting of a testicular neoplasm indicates a yolk sac tumor component. The levels of lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) correlate with the tumor burden.

The treatment of testicular germ cell neoplasms is a remarkable cancer therapy success story. Although roughly 8000 new cases of testicular cancer occur in the United States yearly, fewer than 400 men are expected to die of the disease. In fact, after being treated for widely metastatic testicular cancer, Lance Armstrong won the grueling Tour de France bicycle race a record seven times! Seminoma, which is extremely radiosensitive and tends to remain localized for long periods, has the best prognosis. More than 95% of patients with early-stage disease can be cured. Among nonseminomatous germ cell tumors, the histologic subtype does not influence the prognosis significantly, and hence these are treated as a group. Approximately 90% of the patients achieve complete remission with aggressive chemotherapy, and most are cured. Pure choriocarcinoma carries a dismal prognosis. However, when it is a minor component of a mixed germ cell tumor, the prognosis is not so adversely affected. With all testicular tumors, recurrences, typically in the form of distant metastases, usually occur within the first 2 years after treatment.

![]() Summary

Summary

Testicular Tumors

• Testicular tumors are the most common cause of painless testicular enlargement. They occur with increased frequency in association with undescended testis and with testicular dysgenesis.

• Germ cells are the source of 95% of testicular tumors, and the remainder arise from Sertoli or Leydig cells. Germ cell tumors may be composed of a single histologic pattern (60% of cases) or mixed patterns (40%).

• The most common “pure” histologic patterns of germ cell tumors are seminoma, embryonal carcinoma, yolk sac tumors, choriocarcinoma, and teratoma. Mixed tumors contain more than one element, most commonly embryonal carcinoma, teratoma, and yolk sac tumor.

• Clinically, testicular germ cell tumors can be divided into two groups: seminomas and nonseminomatous tumors. Seminomas remain confined to the testis for a long time and spread mainly to paraaortic nodes—distant spread is rare. Nonseminomatous tumors tend to spread earlier, by both lymphatics and blood vessels.

• HCG is produced by syncytiotrophoblasts and is always elevated in patients with choriocarcinomas and those with seminomas containing syncytiotrophoblasts. AFP is elevated when there is a yolk sac tumor component.

Prostate

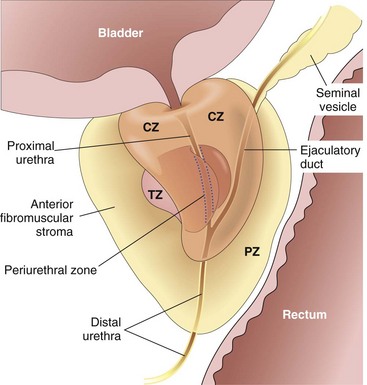

The prostate can be divided into several biologically distinct regions, the most important of which are the peripheral and transition zones (Fig. 17–10). The types of proliferative lesions are different in each region. For example, most hyperplastic lesions arise in the inner transition zone, while most carcinomas (70% to 80%) arise in the peripheral zones. The normal prostate contains glands with two cell layers, a flat basal cell layer and an overlying columnar secretory cell layer. Surrounding prostatic stroma contains a mixture of smooth muscle and fibrous tissue. It is involved by infectious, inflammatory, hyperplastic, and neoplastic disorders, of which prostate cancer is by far the most important clinically.

Figure 17–10 Adult prostate. The normal prostate contains several distinct regions, including a central zone (CZ), a peripheral zone (PZ), a transitional zone (TZ), and a periurethral zone. Most carcinomas arise from the peripheral glands of the organ and often are palpable during digital examination of the rectum. Nodular hyperplasia, by contrast, arises from more centrally situated glands and is more likely than carcinoma to produce urinary obstruction early in its course.

Prostatitis

Prostatitis is divided into four categories: (1) acute bacterial prostatitis (2% to 5% of cases), caused by the same organisms associated with other acute urinary tract infections; (2) chronic bacterial prostatitis (2% to 5% of cases), also caused by common uropathogens; (3) chronic nonbacterial prostatitis, or chronic pelvic pain syndrome (90% to 95% of cases), in which no uropathogen is identified despite the presence of local symptoms; and (4) asymptomatic inflammatory prostatitis (incidence unknown), associated with incidental identification of leukocytes in prostatic secretions without uropathogens.

The prostate is usually not biopsied in men with symptoms of acute or chronic prostatitis, since the findings are usually non-specific and are not helpful in managing patients. The exception is in patients with granulomatous prostatitis, in which a specific etiology may be established. In the United States, the most common cause is instillation of bacille Calmette-Guérin (BCG) within the bladder for treatment of superficial bladder cancer. BCG is an attenuated tuberculosis strain that produces a histologic picture in the prostate indistinguishable from tuberculosis. Disseminated prostatic tuberculosis is rare in the Western world. Fungal granulomatous prostatitis is typically seen only in immunocompromised hosts. Nonspecific granulomatous prostatitis is relatively common and represents a reaction to secretions from ruptured prostatic ducts and acini. Postsurgical prostatic granulomas also may be seen.

Clinical Features

Clinically, acute bacterial prostatitis is associated with fever, chills, and dysuria; it may be complicated by sepsis. On rectal examination, the prostate is exquisitely tender and boggy. Chronic bacterial prostatitis usually is associated with recurrent urinary tract infections bracketed by asymptomatic periods. Presenting manifestations may include with low back pain, dysuria, and perineal and suprapubic discomfort. Both acute and chronic bacterial prostatitis are treated with antibiotics. The diagnosis of chronic nonbacterial prostatitis (chronic pelvic pain syndrome) is difficult. It requires completion of the NIH Chronic Prostatitis Symptom Index survey by the patient, digital rectal examination, urinalysis, and sequential collection of urine and prostatic fluid specimens, before, during, and after prostatic massage. This technique of collecting samples prevents contamination from the bladder and urethra and is used to document prostatic inflammation (by presence of leukocytes) in the absence of infection. There are no proven therapies for chronic pelvic pain syndrome.

![]() Summary

Summary

Prostatitis

• Bacterial prostatitis may be acute or chronic; the responsible organism usually is E. coli or another gram-negative rod.

• Chronic nonbacterial prostatitis (also known as chronic pelvic pain syndrome), despite sharing symptomatology with chronic bacterial prostatitis, is of unknown etiology and does not respond to antibiotics.

• Granulomatous prostatitis has a multifactorial etiology, with both infectious and noninfectious elements.

Benign Prostatic Hyperplasia (Nodular Hyperplasia)

Benign prostatic hyperplasia (BPH) is an extremely common abnormality. It is present in a significant number of men by the age of 40, and its frequency rises progressively with age, reaching 90% by the eighth decade of life. BPH is characterized by proliferation of both stromal and epithelial elements, with resultant enlargement of the gland and, in some cases, urinary obstruction. Although the cause of BPH remains incompletely understood, it is clear that excessive androgen-dependent growth of stromal and glandular elements has a central role. BPH does not occur in males castrated before the onset of puberty or in men with genetic diseases that block androgen activity. Dihydrotestosterone (DHT), the ultimate mediator of prostatic growth, is synthesized in the prostate from circulating testosterone by the action of the enzyme 5α-reductase, type 2. DHT binds to nuclear androgen receptors, which regulate the expression of genes that support the growth and survival of prostatic epithelium and stromal cells. Although testosterone can also bind to androgen receptors and stimulate growth, DHT is 10 times more potent. Clinical symptoms of lower urinary tract obstruction caused by prostatic enlargement may also be exacerbated by contraction of prostatic smooth muscle mediated by α1-adrenergic receptors.

![]() Morphology

Morphology

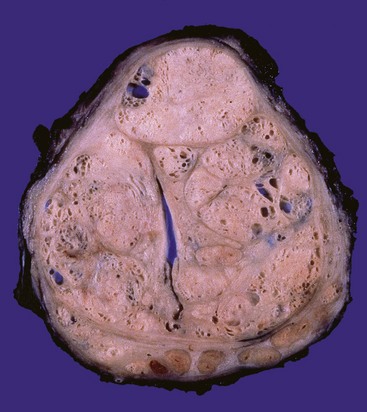

BPH virtually always occurs in the inner, transitional zone of the prostate. The affected prostate is enlarged, typically weighing between 60 and 100 g, and contains many well-circumscribed nodules that bulge from the cut surface (Fig. 17–11). The nodules may appear solid or contain cystic spaces, the latter corresponding to dilated glandular elements. The urethra is usually compressed by the hyperplastic nodules, often to a narrow slit. In some cases, hyperplastic glandular and stromal elements lying just under the epithelium of the proximal prostatic urethra may project into the bladder lumen as a pedunculated mass, producing a ball-valve type of urethral obstruction.

Figure 17–11 Nodular prostatic hyperplasia. Well-defined nodules compress the urethra into a slitlike lumen.

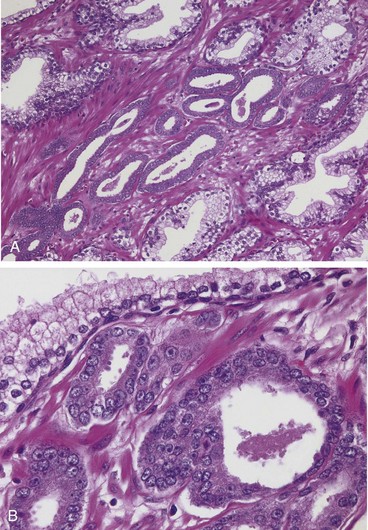

Microscopically the hyperplastic nodules are composed of variable proportions of proliferating glandular elements and fibromuscular stroma. The hyperplastic glands are lined by tall, columnar epithelial cells and a peripheral layer of flattened basal cells (Fig. 17–12). The glandular lumina often contain inspissated, proteinaceous secretory material known as corpora amylacea.

Figure 17–12 Nodular hyperplasia of the prostate. A, Low-power photomicrograph demonstrates a well-demarcated nodule at the right of the field, with a portion of urethra seen to the left. In other cases of nodular hyperplasia, the nodularity is caused predominantly by stromal, rather than glandular, proliferation. B, Higher-power photomicrograph demonstrates the morphology of the hyperplastic glands, which are large, with papillary infolding.

Clinical Features

Clinical manifestations of prostatic hyperplasia occur in only about 10% of men with pathologic evidence of BPH. Because BPH preferentially involves the inner portions of the prostate, the most common manifestations are related to lower urinary tract obstruction, often in the form of difficulty in starting the stream of urine (hesitancy) and intermittent interruption of the urinary stream while voiding. These symptoms frequently are accompanied by urinary urgency, frequency, and nocturia, all indicative of bladder irritation. Similar symptoms also may arise from urethral stricture or as a consequence of impaired bladder detrusor muscle contractility in both men and women. The presence of residual urine in the bladder due to chronic obstruction increases the risk of urinary tract infections. In some affected men, BPH leads to complete urinary obstruction, with resultant painful distention of the bladder and, in the absence of appropriate treatment, hydronephrosis (Chapter 13). Initial treatment is pharmacologic, using targeted therapeutic agents that inhibit DHT formation (Finestride) or that relax smooth muscle by blocking alpha adrenergic blockers (Flomax). Various surgical techniques are reserved for severely symptomatic cases recalcitrant to medical therapy.

![]() Summary

Summary

Benign Prostatic Hyperplasia

• BPH is characterized by proliferation of benign stromal and glandular elements. DHT, an androgen derived from testosterone, is the major hormonal stimulus for proliferation.

• BPH most commonly affects the inner periuretheral zone of the prostate, producing nodules that compress the prostatic urethra. On microscopic examination, the nodules exhibit variable proportions of stroma and glands. Hyperplastic glands are lined by two cell layers: an inner columnar layer and an outer layer composed of flattened basal cells.

• Clinical symptoms and signs are reported by 10% of affected patients and include hesitancy, urgency, nocturia, and poor urinary stream. Chronic obstruction predisposes to recurrent urinary tract infections. Acute urinary obstruction may occur.

Carcinoma of the Prostate

Adenocarcinoma of the prostate occurs mainly in men older than 50 years of age. It is the most common form of cancer in men, accounting for 25% of cancer in men in the United States in 2009. However, prostate cancer causes only 9% of cancer deaths in the United States, less than that for cancers of the lung and equal to that for colorectal cancer. Furthermore, over the past several decades, there has been a significant drop in prostate cancer mortality.

This relatively favorable outcome is related in part to increased detection of the disease through screening (described later), but how effective screening is at saving lives is controversial. This seeming paradox is related to wide variation in the natural history of prostate cancer, from aggressive and rapidly fatal to indolent disease of no clinical significance. Indeed, prostate carcinoma commonly is found incidentally at autopsy in men dying of other causes, and many more men die with prostate cancer than of prostate cancer. It is not currently possible to identify the tumors that will be “bad actors” with certainty; thus, while some men are no doubt saved by early detection and treatment of their prostate cancers, it is equally certain that others are being “cured” of clinically inconsequential tumors.

![]() Pathogenesis

Pathogenesis

Clinical and experimental observations suggest that androgens, heredity, environmental factors, and acquired somatic mutations have roles in the pathogenesis of prostate cancer.

• Androgens are of central importance. Cancer of the prostate does not develop in males castrated before puberty, indicating that androgens somehow provide the “soil,” the cellular context, within which prostate cancer develops. This dependence on androgens extends to established cancers, which often regress for a time in response to surgical or chemical castration. Notably, tumors resistant to anti-androgen therapy often acquire mutations that permit androgen receptors to activate the expression of their target genes even in the absence of the hormones. Thus, tumors that recur in the face of anti-androgen therapies still depend on gene products regulated by androgen receptors for their growth and survival. However, while prostate cancer, like normal prostate, is dependent on androgens for its survival, there is no evidence that androgens initiate carcinogenesis.

• Heredity also contributes, as there is an increased risk among first-degree relatives of patients with prostate cancer. Incidence of prostatic cancer is uncommon in Asians and highest among blacks and is also high in Scandinavian countries. Genome-wide association studies have identified a number of genetic variants that are associated with increased risk, including a variant near the MYC oncogene on chromosome 8q24 that appears to account for some of the increased incidence of prostate cancer in males of African descent. Similarly, in white American men, the development of prostate cancer has been linked to a susceptibility locus on chromosome 1q24-q25.

• Environment also plays a role, as evidenced by the fact that in Japanese immigrants to the United States the incidence of the disease rises (although not to the level seen in native-born Americans). Also, as the diet in Asia becomes more Westernized, the incidence of clinical prostate cancer in this region of the world appears to be increasing. However, the relationship between specific dietary components and prostate cancer risk is unclear.

• Acquired somatic mutations, as in other cancers, are the actual drivers of cellular transformation. One important class of somatic mutations is gene rearrangements that create fusion genes consisting of the androgen-regulated promoter of the TMPRSS2 gene and the coding sequence of ETS family transcription factors (the most common being ERG). TMPRSS2-ETS fusion genes occur in approximately 40% to 50% of prostate cancers; it is possible that unregulated increased expression of ETS transcription factors interfere with prostatic epithelial cell differentiation. Other mutations commonly lead to activation of the oncogenic PI3K/AKT signaling pathway; of these, the most common are mutations that inactivate the tumor suppressor gene PTEN, which acts as a brake on PI3K activity.

![]() Morphology

Morphology

Most carcinomas detected clinically are not visible grossly. More advanced lesions appear as firm, gray-white lesions with ill-defined margins that infiltrate the adjacent gland (Fig. 17–13).

Figure 17–13 Adenocarcinoma of the prostate. Carcinomatous tissue is seen on the posterior aspect (lower left). Note the solid whiter tissue of cancer, in contrast with the spongy appearance of the benign peripheral zone on the contralateral side.

On histologic examination, most lesions are moderately differentiated adenocarcinomas that produce well-defined glands. The glands typically are smaller than benign glands and are lined by a single uniform layer of cuboidal or low columnar epithelium, lacking the basal cell layer seen in benign glands. In further contrast with benign glands, malignant glands are crowded together and characteristically lack branching and papillary infolding. The cytoplasm of the tumor cells ranges from pale-clear (as in benign glands) to a distinctive amphophilic (dark purple) appearance. Nuclei are enlarged and often contain one or more prominent nucleoli (Fig. 17–14). Some variation in nuclear size and shape is usual, but in general, pleomorphism is not marked. Mitotic figures are uncommon. With increasing grade, irregular or ragged glandular structures, cribriform glands, sheets of cells, or infiltrating individual cells are present. In approximately 80% of cases, prostatic tissue removed for carcinoma also harbors presumptive precursor lesions, referred to as high-grade prostatic intraepithelial neoplasia (HGPIN).

Figure 17–14 A, Adenocarcinoma of the prostate demonstrating small glands crowded in between larger benign glands. B, Higher magnification shows several small malignant glands with enlarged nuclei, prominent nucleoli, and dark cytoplasm, as compared with the larger, benign gland (top).

Prostate cancer is graded by the Gleason system, created in 1967 and updated in 2005. According to this system, prostate cancers are stratified into five grades on the basis of glandular patterns of differentiation. Grade 1 represents the most well-differentiated tumors and grade 5 tumors show no glandular differentiation. Since most tumors contain more than one pattern, a primary grade is assigned to the dominant pattern and a secondary grade to the next most frequent pattern. The two numerical grades are then added to obtain a combined Gleason score. Tumors with only one pattern are treated as if their primary and secondary grades are the same, and, hence, the number is doubled. Thus the most differentiated tumors have a Gleason score of 2 (1 + 1) and the least differentiated tumors merit a score of 10 (5 + 5).

Clinical Features

A minority of carcinomas are discovered unexpectedly during histologic examination of prostate tissue removed by transurethral resection for BPH. Some 70% to 80% of prostate cancers arise in the outer (peripheral) glands and hence may be palpable as irregular hard nodules on digital rectal examination. However, most prostate cancers are small, nonpalpable, asymptomatic lesions discovered on needle biopsy performed to investigate an elevated serum prostate-specific antigen (PSA) level (discussed later). Because of the peripheral location, prostate cancer is less likely than BPH to cause urethral obstruction in its initial stages. Locally advanced cancers often infiltrate the seminal vesicles and periurethral zones of the prostate and may invade the adjacent soft tissues, the wall of the urinary bladder, or (less commonly) the rectum. Bone metastases, particularly to the axial skeleton, are frequent late in the disease and typically cause osteoblastic (bone-producing) lesions that can be detected on radionuclide bone scans. The poor sensitivity and specificity of prostate imaging studies limit their diagnostic utility for the detection of early prostate cancer.

The PSA assay is the most important test used in the diagnosis and management of prostate cancer but, as will be discussed, suffers from a number of limitations. PSA is a product of prostatic epithelium and is normally secreted in the semen. It is a serine protease whose function is to cleave and liquefy the seminal coagulum formed after ejaculation. In most laboratories, a serum PSA level of 4 ng/mL is the cutoff between normal and abnormal, although some guidelines designate values above 2.5 ng/mL as abnormal. Although PSA screening can detect prostate cancers early in their course, many prostate cancers are slow-growing and clinically insignificant, requiring no treatment. In addition, prostate cancer treatments often cause significant complications, particularly erectile dysfunction and incontinence.

One limitation of PSA is that while it is organ-specific, it is not cancer-specific. BPH, prostatitis, prostatic infarcts, instrumentation of the prostate, and ejaculation also increase serum PSA levels. Conversely, 20 to 40% of patients with organ-confined prostate cancer have a PSA value of 4.0 ng/mL or less. In recognition of these problems, several refinements in the estimation and interpretation of PSA values have been proposed that aim to enhance the specificity and sensitivity of the test. One approach is to correct the PSA for estimated prostate size, to account for elevations in PSA that are associated with enlarged prostates (e.g., those involved by BPH). A second is to use a sliding scale that takes the rise in PSA that occurs with age into account. A third is to focus on changes in PSA levels in serial measurements over time. Men with prostate cancer demonstrate an increased rate of rise in PSA as compared with men who do not have prostate cancer. A significant rise in serum PSA levels, even if the PSA is within the “normal” range, should prompt a workup. Finally, PSA present in the serum is mostly bound to plasma proteins but also includes a minor free fraction. The percentage of free PSA (the ratio of free PSA to total PSA) is lower in men with prostate cancer than in men with benign prostatic diseases.

Once cancer is diagnosed, serial measurements of PSA are of great value in assessing the response to therapy. For example, a rising PSA level after radical prostatectomy or radiotherapy for localized disease is indicative of recurrent or disseminated disease.

The most common treatments for clinically localized prostate cancer are radical prostatectomy and radiotherapy. The prognosis after radical prostatectomy is based on the pathologic stage, margin status, and Gleason grade. The Gleason grade, clinical stage, and serum PSA values are important predictors of outcome after radiotherapy. Because many prostate cancers follow an indolent course, active surveillance (“watchful waiting”) is an appropriate approach for older men, patients with significant comorbidity, or even some younger men with low serum PSA values and small, low-grade cancers. Advanced metastatic carcinoma is treated by androgen deprivation, effected either by orchiectomy or by administration of synthetic agonists of luteinizing hormone–releasing hormone (LHRH), which in effect achieve a pharmacologic orchiectomy. Although antiandrogen therapy induces remissions, androgen-independent clones eventually emerge, leading to rapid disease progression and death. As mentioned earlier, these mutant clones continue to express many genes that in normal prostate are androgen-dependent.

![]() Summary

Summary

Carcinoma of the Prostate

• Carcinoma of the prostate is a common cancer of older men between 65 and 75 years of age. Aggressive, clinical significant disease is more common in American blacks than in whites, while clinically insignificant occult lesions appear to occur at equal frequencies in these two races.

• Prostate carcinomas range from indolent lesions that will never cause patient harm to aggressive fatal tumors.

• The most common acquired mutations in prostatic carcinomas are TPRSS2-ETS fusion genes and mutations that activate the PI3K/AKT signaling pathway.

• Carcinomas of the prostate arise most commonly in the outer, peripheral gland and may be palpable by rectal examination, although currently many are nonpalpable.

• Microscopically, they are adenocarcinomas with variable differentiation. Neoplastic glands are lined by a single layer of cells.

• Grading of prostate cancer by the Gleason system correlates with pathologic stage and prognosis.

• Most localized cancers are clinically silent and are detected by routine monitoring of PSA concentrations in older men. Bone metastases, often osteoblastic, typify advanced prostate cancer.

• Serum PSA measurement is a useful but imperfect cancer screening test, with significant rates of false-negative and false-positive results. Evaluation of PSA concentrations after treatment has great value in monitoring progressive or recurrent disease.

Ureter, Bladder, and Urethra

The renal pelves, ureters, bladder, and urethra are lined by urothelium. Beneath the mucosa are the lamina propria and, deeper yet, the muscularis propria (detrusor muscle), which makes up the bladder wall.

Ureter

Ureteropelvic junction (UPJ) obstruction, a congenital disorder, results in hydronephrosis. It usually manifests in infancy or childhood, much more commonly in boys. It is the most frequent cause of hydronephrosis in infants and children (Chapter 13).

Primary malignant tumors of the ureter follow patterns similar to those arising in the renal pelvis, calyces, and bladder, and a majority are urothelial carcinomas.

Retroperitoneal fibrosis is an uncommon cause of ureteral narrowing or obstruction characterized by a fibrous proliferative inflammatory process encasing the retroperitoneal structures and causing hydronephrosis. The disorder occurs in middle to old age. At least a proportion of these cases are related to the newly described entity in which elevations of serum IgG4 are associated with fibroinflammatory lesions that are rich in IgG4-secreting plasma cells (Chapter 4). The affected sites include the pancreas, retroperitoneum, and salivary glands, to mention a few. Other cases are associated with drug exposures (ergot derivatives, adrenergic blockers), or malignant disease (lymphomas, urinary tract carcinomas). The majority of cases, however, have no obvious cause and are considered primary, or idiopathic (Ormond disease).

Urinary Bladder

Non-neoplastic Conditions

A bladder or vesical diverticulum consists of a pouchlike evagination of the bladder wall. Diverticula may be congenital but more commonly are acquired lesions that arise as a consequence of persistent urethral obstruction caused, for example, by benign prostatic hyperplasia. Although most diverticula are small and asymptomatic, they sometimes lead to urinary stasis and predispose to infection.

Cystitis takes many forms. Most cases stem from nonspecific acute or chronic inflammation of the bladder. The common etiologic agents of bacterial cystitis are coliform bacteria. Patients receiving cytotoxic antitumor drugs, such as cyclophosphamide, sometimes develop hemorrhagic cystitis. Adenovirus infection also causes a hemorrhagic cystitis. Several distinct variants of cystitis are defined by either morphologic appearance or causation.

• Interstitial cystitis (i.e., chronic pelvic pain syndrome) is a persistent, painful form of chronic cystitis occurring most frequently in women. It is characterized by intermittent, often severe suprapubic pain, urinary frequency, urgency, hematuria and dysuria without evidence of bacterial infection, and cystoscopic findings of fissures and punctate hemorrhages (glomerulations) in the bladder mucosa. The histologic findings are nonspecific. Late in the course, transmural fibrosis may ensue, leading to a contracted bladder.

• Malakoplakia most commonly occurs in the bladder and results from defects in phagocytic or degradative function of macrophages, such that phagosomes become overloaded with undigested bacterial products. The macrophages have abundant granular cytoplasm filled with phagosomes stuffed with particulate and membranous bacterial debris. In addition, laminated mineralized concretions resulting from deposition of calcium in enlarged lysosomes, known as Michaelis-Gutmann bodies, typically are present within the macrophages.

• Polypoid cystitis is an inflammatory condition resulting from irritation to the bladder mucosa in which the urothelium is thrown into broad bulbous polypoid projections as a result of marked submucosal edema. Polypoid cystitis may be confused with papillary urothelial carcinoma both clinically and histologically.

Various metaplastic lesions may occur in the bladder. Nests of urothelium (Brunn nests) may grow downward into the lamina propria, and their central epithelial cells may variously differentiate into a cuboidal or columnar epithelium lining (cystitis glandularis); cystic spaces filled with clear fluid lined by flattened urothelium (cystitis cystica); or goblet cells resembling intestinal mucosa (intestinal or colonic metaplasia). As a response to injury, the urothelium often undergoes squamous metaplasia, which must be differentiated from normal glycogenated squamous epithelium, commonly found at the trigone in women.

Neoplasms

Bladder cancer accounts for approximately 7% of cancers and 3% of cancer deaths in the United States. The vast majority of bladder cancers (90%) are urothelial carcinomas. Carcinoma of the bladder is more common in men than in women, in industrialized than in developing nations, and in urban than in rural dwellers. About 80% of patients are between the ages of 50 and 80 years. Squamous cell carcinomas represent about 3% to 7% of bladder cancers in the United States but are much more common in countries where urinary schistosomiasis is endemic. They typically show extensive keratinization and are nearly always associated with chronic bladder irritation and infection. Adenocarcinomas of the bladder are rare and are histologically identical to adenocarcinomas seen in the gastrointestinal tract. Some arise from urachal remnants in the dome of the bladder or in association with extensive intestinal metaplasia.

![]() Pathogenesis

Pathogenesis

Bladder cancer, with rare exceptions, is not familial. Some of the most common factors implicated in the causation of urothelial carcinoma include cigarette smoking, various occupational carcinogens, and Schistosoma haematobium infections in areas where it is endemic, such as Egypt. Cancers occurring in the setting of schistosoma infections arise in a background of chronic inflammation, which you will recall is linked to a number of different cancers (Chapter 5). A model for bladder carcinogenesis has been proposed in which the tumor is initiated by deletions of tumor-suppressor genes on 9p and 9q, leading to formation of superficial papillary tumors, a few of which may then acquire TP53 mutations and progress to invasion. A second pathway, possibly initiated by TP53 mutations, leads first to carcinoma in situ and then, with loss of chromosome 9, progresses to invasion. The underlying genetic alterations in superficial tumors include fibroblast growth factor receptor 3 (FGFR3) mutations and activation of the Ras pathway (indeed, bladder cancer was one of the first human neoplasms found to have activating mutations in the Ras oncogene), whereas less common muscle invasive tumors often have loss-of-function mutations involving TP53 and RB, the retinoblastoma tumor suppressor gene.

![]() Morphology

Morphology

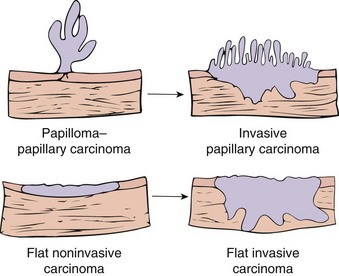

Two distinct precursor lesions to invasive urothelial carcinoma are recognized (Fig. 17–15). The most common is a noninvasive papillary tumor (Fig. 17–16). The other precursor is carcinoma in situ (CIS), described below. In about half of the patients with invasive bladder cancer, no precursor lesion is found; in such cases, it is presumed that the precursor lesion was overgrown by the high-grade invasive component.

Figure 17–16 Cystoscopic appearance of a papillary urothelial tumor, resembling coral, within the bladder.

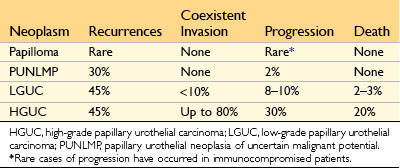

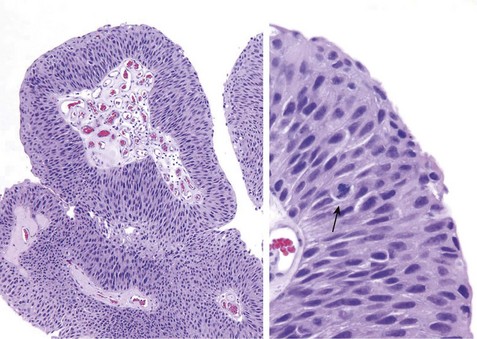

Noninvasive papillary urothelial neoplasms demonstrate a range of atypia and are graded to reflect their biologic behavior (Table 17–2). The most common grading system classifies tumors as follows: (1) papilloma; (2) papillary urothelial neoplasm of low malignant potential (PUNLMP); (3) low-grade papillary urothelial carcinoma; and (4) high-grade papillary urothelial carcinoma (Fig. 17–17). These exophytic papillary neoplasms are to be distinguished from inverted urothelial papilloma, which is entirely benign and not associated with an increased risk for subsequent carcinoma.

Figure 17–17 Noninvasive low-grade papillary urothelial carcinoma. Higher magnification (right) shows slightly irregular nuclei with scattered mitotic figures (arrow).

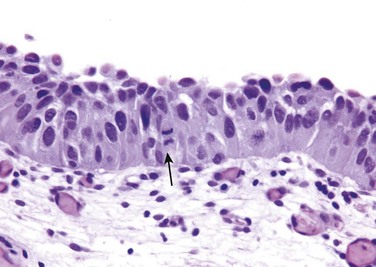

CIS is defined by the presence of cytologically malignant cells within a flat urothelium (Fig. 17–18). Like high-grade papillary urothelial carcinoma, CIS tumor cells lack cohesiveness. This leads to the shedding of malignant cells into the urine, where they can be detected by cytology. CIS commonly is multifocal and sometimes involves most of the bladder surface or extends into the ureters and urethra. Without treatment, 50% to 75% of CIS cases progress to muscle-invasive cancer.

Figure 17–18 Carcinoma in situ (CIS) with enlarged hyperchromatic nuclei and a mitotic figure (arrow).

Invasive urothelial cancer associated with papillary urothelial cancer (usually of high grade) or CIS may superficially invade the lamina propria or extend more deeply into underlying muscle. Underestimation of the extent of invasion in biopsy specimens is a significant problem. The extent of invasion and spread (staging) at the time of initial diagnosis is the most important prognostic factor. Almost all infiltrating urothelial carcinomas are of high grade.

Clinical Features

Bladder tumors most commonly present with painless hematuria. Patients with urothelial tumors, whatever their grade, have a tendency to develop new tumors after excision, and recurrences may exhibit a higher grade. The risk of recurrence is related to several factors, including tumor size, stage, grade, multifocality, mitotic index, and associated dysplasia and/or CIS in the surrounding mucosa. Most recurrent tumors arise at sites different than that of the original lesion, yet share the same clonal abnormalities as those of the initial tumor; thus, these are true recurrences that stem from shedding and implantation of the original tumor cells at new sites. Whereas high-grade papillary urothelial carcinomas frequently are associated with either concurrent or subsequent invasive urothelial carcinoma, lower-grade papillary urothelial neoplasms often recur but infrequently invade (Table 17–2).

The treatment for bladder cancer depends on tumor grade and stage and on whether the lesion is flat or papillary. For small localized papillary tumors that are not high-grade, the initial transurethral resection is both diagnostic and therapeutically sufficient. Patients with tumors that are at high risk for recurrence or progression typically receive topical immunotherapy consisting of intravesical instillation of an attenuated strain of the tuberculosis bacillus called bacille Calmette-Guérin (BCG). BCG elicits a typical granulomatous reaction, and in doing so also triggers an effective local antitumor immune response. Patients are closely monitored for tumor recurrence with periodic cystoscopy and urine cytologic studies for the rest of their lives. Radical cystectomy typically is reserved for (1) tumor invading the muscularis propria; (2) CIS or high-grade papillary cancer refractory to BCG; and (3) CIS extending into the prostatic urethra and down the prostatic ducts, where BCG cannot contact the neoplastic cells. Advanced bladder cancer is treated using chemotherapy, which can palliate but is not curative.

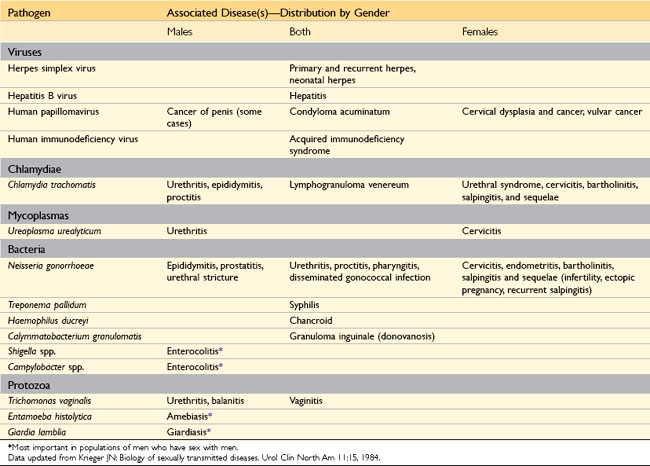

Sexually Transmitted Diseases

Sexually transmitted diseases (STDs) have complicated human existence for centuries. Globally, approximately 15 million new cases of STD occur every year; of these, 4 million affect 15- to 19-year-olds, and 6 million affect 20- to 24-year-olds. Of the 10 leading infectious diseases that require notification of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) in the United States, five—chlamydial infection, gonorrhea, acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS), syphilis, and hepatitis B—are STDs (Table 17–3). In the United States, the two most common STDs are genital herpes and genital HPV infection, but these do not require CDC notification. Several of these entities, such as human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection, HPV infection, hepatitis B, and infection with E. histolytica, are discussed in other chapters.

Syphilis

Syphilis, or lues, is a chronic venereal infection caused by the spirochete Treponema pallidum. First recognized in epidemic form in 16th-century Europe as the Great Pox, syphilis is an endemic infection in all parts of the world. In the United States, approximately 6000 cases are reported every year, but this number has been rising since 2000. For example, primary and secondary syphilis among females 10 years of age and older rose from 0.8 per 100,000 in 2004 to 1.5 per 100,000 in 2009. A strong racial disparity is evident: African Americans are affected 30 times more often than whites.

T. pallidum is a fastidious organism whose only natural host is man. The usual source of infection is contact with a cutaneous or mucosal lesion in a sexual partner in the early (primary or secondary) stages of syphilis. The organism is transmitted from such lesions during sexual activity through minute breaks in the skin or mucous membranes of the uninfected partner. In congenital cases, T. pallidum is transmitted across the placenta from mother to fetus, particularly during the early stages of maternal infection.

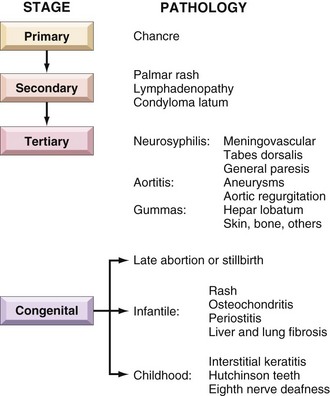

Once introduced into the body, the organisms rapidly disseminate to distant sites through lymphatics and the blood, even before the appearance of lesions at the primary inoculation site. This widespread dissemination accounts for the protean manifestations of the disease (Fig. 17–19), which can be divided into primary, secondary, and tertiary stages in adults. Between 9 and 90 days (mean, 21 days) after infection, a primary lesion, termed a chancre, appears at the point of spirochete entry. Systemic dissemination of organisms continues during this period, while the host mounts an immune response. Two types of antibodies are formed: antibodies that cross-react with host constituents (nontreponemal antibodies) and antibodies to specific treponemal antigens. This humoral response, however, fails to eradicate the organisms.

The chancre of primary syphilis resolves spontaneously over a period of 4 to 6 weeks and is followed in approximately 25% of untreated patients by the development of secondary syphilis. The manifestations of secondary syphilis, discussed in greater detail later on, include generalized lymphadenopathy and variable mucocutaneous lesions. The mucocutaneous lesions of both primary and secondary syphilis are teeming with spirochetes and are highly infectious. Like the chancre, the lesions of secondary syphilis resolve without any specific antimicrobial therapy, at which point patients are said to be in early latent phase syphilis. The U.S. Public Health Service restricts the definition of early latent syphilis to the 1-year period after infection. Mucocutaneous lesions may recur during this phase of the disease.

Patients with untreated syphilis next enter an asymptomatic, late latent phase of the illness. In about one third of cases, new symptoms develop over the next 5 to 20 years. This late symptomatic phase, or tertiary syphilis, is marked by the development of lesions in the cardiovascular system, central nervous system, or, less frequently, other organs. Spirochetes are much more difficult to demonstrate during the later stages of disease, and patients are accordingly much less likely to be infectious than are those in the primary or secondary stage of disease. Syphilis is common in HIV-infected patients. Like all other ulcerative genital diseases, syphilis promotes the transmission of HIV, and HIV stimulates the progression of syphilis.

![]() Morphology

Morphology

The pathognomonic microscopic lesion of syphilis is a proliferative endarteritis with an accompanying inflammatory infiltrate rich in plasma cells. Endarteritis has a central role in tissue injury at all sites involved by syphilis, but its pathogenesis is not understood; there is no evidence that the spirochetes cause any damage to host tissues directly. Instead, it is thought that the host immune response is responsible for the endothelial cell activation and proliferation that is the hallmark of the endarteritis, which eventually leads to perivascular fibrosis and luminal narrowing. Spirochetes are readily demonstrable in histologic sections of early lesions with the use of standard silver stains (e.g., Warthin-Starry stains). Large areas of parenchymal damage in tertiary syphilis result in the formation of a gumma, an irregular, firm mass of necrotic tissue surrounded by resilient connective tissue. On microscopic examination, the gumma contains a central zone of coagulative necrosis surrounded by a mixed inflammatory infiltrate composed of lymphocytes, plasma cells, activated macrophages (epithelioid cells), occasional giant cells, and a peripheral zone of dense fibrous tissue.

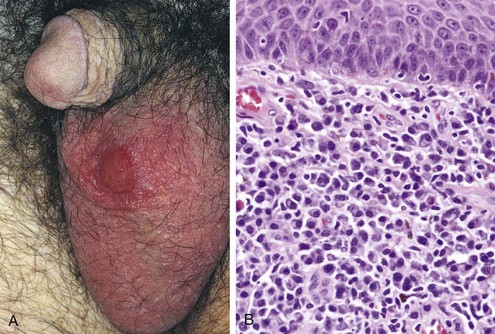

Primary Syphilis

The chancre of syphilis is characteristically indurated and has been referred to as a “hard chancre,” to distinguish it from the “soft chancre” of chancroid caused by Haemophilus ducreyi (discussed later). The primary chancre in males usually is on the penis. In females, multiple chancres may be present, usually in the vagina or on the uterine cervix. The chancre begins as a small, firm papule, which gradually enlarges to produce a painless ulcer with well-defined, indurated margins and a “clean,” moist base (Fig. 17–20). Regional lymph nodes often are slightly enlarged and firm but painless. Histologic examination of the ulcer reveals the usual lymphocytic and plasmacytic inflammatory infiltrate and proliferative vascular changes, as described previously. Even without therapy, the primary chancre resolves over a period of several weeks to form a subtle scar.

Secondary Syphilis

Within approximately 2 months of resolution of the chancre, the lesions of secondary syphilis appear. The manifestations of secondary syphilis are varied but typically include a combination of generalized lymph node enlargement and a variety of mucocutaneous lesions. Skin lesions usually are symmetrically distributed and may be maculopapular, scaly, or pustular. Involvement of the palms of the hands and soles of the feet is common. In moist skin areas, such as the anogenital region, inner thighs, and axillae, broad-based, elevated lesions termed condylomata lata may appear (not to be confused with condyloma acuminata caused by HPV (Chapters 18 and 23). Superficial mucosal lesions resembling condylomata lata can occur anywhere but are particularly common in the oral cavity and pharynx and on the external genitalia.

Histologic examination of mucocutaneous lesions during the secondary phase of the disease reveals the characteristic proliferative endarteritis, accompanied by a lymphoplasmacytic inflammatory infiltrate. Spirochetes are present and often abundant within these mucocutaneous lesions; they are therefore contagious. Lymph node enlargement is most common in the neck and inguinal areas. Histologic examination of enlarged nodes demonstrates hyperplasia of germinal centers accompanied by increased numbers of plasma cells or, less commonly, granulomas or neutrophils.

Less common manifestations of secondary syphilis include hepatitis, renal disease, eye disease (iritis), and gastrointestinal abnormalities. The mucocutaneous lesions of secondary syphilis resolve over several weeks, at which point the disease enters its early latent phase, which lasts approximately 1 year. Lesions may recur at any time during this latent period, and these lesions are also highly infectious.

Tertiary Syphilis

Tertiary syphilis develops in approximately one third of untreated patients, usually after a latent period of 5 years or more. Complications related to this phase of syphilis are divided into three major categories, cardiovascular syphilis, neurosyphilis, and so-called benign tertiary syphilis, which may occur singly or in combination. Cardiovascular syphilis takes the form of syphilitic aortitis and accounts for more than 80% of cases of tertiary disease; it is much more common in men than in women. The morphologic and clinical features of syphilitic aortitis are discussed in greater detail in Chapter 9. Neurosyphilis accounts for 10% of cases of tertiary syphilis overall but occurs at increased frequency in those with concomitant HIV infection; it is discussed in detail in Chapter 22. “Benign” tertiary syphilis is an uncommon form marked by the development of gummas in various sites. Emergence of these lesions probably is related to the development of delayed hypersensitivity. Gummas occur most commonly in bone, skin, and the mucous membranes of the upper airway and mouth, but any organ may be affected. Spirochetes are rarely demonstrable within gummas. Once common, gummas have become exceedingly rare thanks to the development of effective antibiotics such as penicillin. They are reported now mostly in patients with AIDS.

Congenital Syphilis

T. pallidum may be transmitted across the placenta from an infected mother to the fetus at any time during pregnancy. The likelihood of transmission is greatest during the early (primary and secondary) stages of disease, when spirochetes are most numerous. Because the manifestations of maternal disease may be subtle, routine serologic testing for syphilis is mandatory in all pregnancies. The stigmata of congenital syphilis typically do not develop until after the fourth month of pregnancy. In the absence of treatment, as many as 40% of infected infants die in utero, typically after the fourth month. The incidence of congenital syphilis increased 23% in the United States from 2003 to 2008.

Manifestations of congenital syphilis include stillbirth, infantile syphilis, and late (tardive) congenital syphilis. Among infants who are stillborn, the most common manifestations are hepatomegaly, bone abnormalities, pancreatic fibrosis, and pneumonitis. The liver often shows extramedullary hematopoiesis and portal tract inflammation. Changes in the bones include inflammation and disruption of the osteochondral junction in long bones and, on occasion, bone resorption and fibrosis of the flat bones of the skull. The lungs may be firm and pale as a result of the presence of inflammatory cells and fibrosis in the alveolar septa (pneumonia alba). Spirochetes are readily demonstrable in tissue sections. In cases of congenital syphilis, the placenta is enlarged, pale, and edematous. Microscopy reveals proliferative endarteritis involving the fetal vessels, a mononuclear inflammatory reaction (villitis), and villous immaturity.

Infantile syphilis refers to congenital syphilis in liveborn infants that is clinically manifest at birth or within the first few months of life. Affected infants present with chronic rhinitis (snuffles) and mucocutaneous lesions similar to those seen in secondary syphilis in adults. Visceral and skeletal changes resembling those seen in stillborn infants also may be present.

Late, or tardive, congenital syphilis refers to cases of untreated congenital syphilis of more than 2 years’ duration. Classic manifestations include the Hutchinson triad: notched central incisors, interstitial keratitis with blindness, and deafness from eighth cranial nerve injury. Other changes include a so-called saber shin deformity caused by chronic inflammation of the periosteum of the tibia, deformed molar teeth (“mulberry molars”), chronic meningitis, chorioretinitis, and gummas of the nasal bone and cartilage with a resultant “saddlenose” deformity.

Serologic Tests for Syphilis

Although polymerase chain reaction (PCR)–based testing for syphilis has been developed, serology remains the mainstay of diagnosis. Serologic tests for syphilis include nontreponemal antibody tests and antitreponemal antibody tests. Nontreponemal tests measure antibody to cardiolipin, an antigen that is present in both host tissues and the treponemal cell wall. These antibodies are detected by the rapid plasma reagin (RPR) and Venereal Disease Research Laboratory (VDRL) tests. Nontreponemal antibody tests are usually positive by 4 to 6 weeks of infection and are strongly positive in the secondary phase of infection. However, nontreponemal antibody test results may revert to negative during the tertiary phase or, conversely, may on occasion be persistently positive in some patients after successful treatment. Two additional points regarding nontreponemal antibody tests deserve emphasis:

• Nontreponemal antibody test results often are negative during the early stages of disease, even in the presence of a primary chancre. Hence, during this period, direct visualization of the spirochetes by darkfield or immunofluorescence microscopy may be the only way to confirm the diagnosis.

• As many as 15% of positive VDRL test results are unrelated to syphilis. These false-positive results, which may be acute (transient) or chronic (persistent), increase in frequency with age and are associated with a variety of conditions, including the antiphospholipid antibody syndrome (Chapter 3).

Treponemal antibody tests also become positive within 4 to 6 weeks after an infection, but, unlike those for nontreponemal antibody tests, they usually remain positive indefinitely, even after successful treatment. These tests give strongly positive results in virtually all cases of secondary syphilis. They are not recommended as screening tests, however, because they remain positive after treatment and have a high false-positive test rate (approximately 2%) in the general population.

Serologic response may be delayed, exaggerated (false-positive results), or absent in patients with syphilis and coexistent HIV infection. In most cases, however, these tests remain useful in the diagnosis and management of syphilis in patients with AIDS.

![]() Summary

Summary

Syphilis

• Syphilis is caused by T. pallidum and has three stages. In primary syphilis a painless lesion called chancre develops on the external genitalia along with regional lymph node enlargement. Secondary syphilis manifests with generalized lymphadenopathy and mucocutaneous lesions that may be maculopapular or take the form of flat raised lesions called condylomata lata. Tertiary syphilis may cause proximal aortitis and aortic insufficiency; may involve the brain, meninges, and the spinal cord; or may cause focal granulomatous lesions called gummas in multiple organs.

• Congenital syphilis is caused by maternal transmission of the spirochetes, mostly during primary and secondary stages of disease in the mother. It may lead to stillbirth or cause widespread tissue injury in liver, spleen, lung, bones, and pancreas.

• On histologic examination, most syphilitic lesions demonstrate proliferative endarteritis and a plasma cell–rich inflammatory infiltrate. Gummas have a central area of necrosis surrounded by lymphoplasmacytic infiltrates and epithelioid cells.

• The diagnostic mainstay is serologic testing. Nontreponemal antibody tests (VDRL and RPR) are usually positive in early disease, but may be negative in advanced disease. Treponeme-specific antibody test results become positive later and remain positive indefinitely. Treponemes can also be identified by microscopic examination of primary and secondary lesions.

Gonorrhea

Gonorrhea is a sexually transmitted infection of the lower genitourinary tract caused by Neisseria gonorrhoeae. Gonorrhea is second only to chlamydial infection of the genitourinary tract (discussed later) among reportable communicable diseases in the United States. With an estimated 650,000 cases each year in the United States, it remains a major public health problem. The gravity of gonococcal infections has increased with the emergence of strains of N. gonorrhoeae that are resistant to multiple antibiotics.

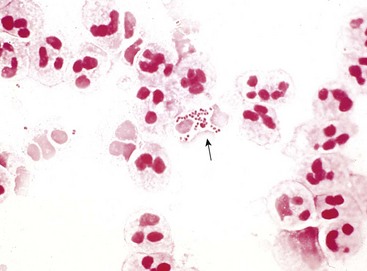

Humans are the only natural reservoir for N. gonorrhoeae. The organism is highly fastidious, and spread of infection requires direct contact with the mucosa of an infected person, usually during sexual activity. The bacteria initially attach to mucosal epithelium, particularly of the columnar or transitional type, using a variety of membrane-associated adhesion molecules and structures termed pili (Chapter 8). Such attachment prevents the organism from being unceremoniously flushed away by body fluids such as urine or endocervical mucus. The organism then penetrates through the epithelial cells to invade the deeper tissues of the host.

![]() Morphology

Morphology

N. gonorrhoeae provokes an intense, suppurative inflammatory reaction. In males this manifests most often as a purulent urethral discharge, associated with an edematous, congested urethral meatus. Gram-negative diplococci, many within the cytoplasm of neutrophils, are readily identified in Gram stains of the purulent exudate (Fig. 17–21). Ascending infection may result in the development of acute prostatitis, epididymitis (Fig. 17–22), or orchitis. Abscesses may complicate severe cases. Urethral and endocervical exudates tend to be less conspicuous in females, although acute inflammation of adjacent structures, such as the Bartholin glands, is fairly common. Ascending infection involving the uterus, fallopian tubes, and ovaries results in acute salpingitis, sometimes complicated by tuboovarian abscesses. The acute inflammatory process is followed by the development of granulation tissue and scarring, with resultant strictures and other permanent deformities of the involved structures, giving rise to pelvic inflammatory disease (Chapter 18).

Clinical Features

In most infected males, gonorrhea is manifested by the presence of dysuria, urinary frequency, and a mucopurulent urethral exudate within 2 to 7 days of the time of initial infection. Treatment with appropriate antimicrobial therapy results in eradication of the organism and prompt resolution of symptoms. Untreated infections may ascend to involve the prostate, seminal vesicles, epididymis, and testis. Neglected cases may be complicated by chronic urethral stricture and, in more advanced cases, by permanent sterility. Untreated men also may become chronic carriers of N. gonorrhoeae.

Among female patients, acute infections acquired by vaginal intercourse may be asymptomatic or associated with dysuria, lower pelvic pain, and vaginal discharge. Untreated cases may be complicated by ascending infection, leading to acute inflammation of the fallopian tubes (salpingitis) and ovaries. Scarring of the fallopian tubes may occur, with resultant infertility and an increased risk of ectopic pregnancy. Gonococcal infection of the upper genital tract may spread to the peritoneal cavity, where the exudate may extend up the right paracolic gutter to the dome of the liver, resulting in gonococcal perihepatitis. Depending on sexual practices, other sites of primary infection in both males and females include the oropharynx and the anorectal area, with resultant acute pharyngitis and proctitis, respectively.