Paediatric oral medicine, oral pathology and radiology

Michael J Aldred, Angus C Cameron and Anastasia Georgiou

Introduction

Although some disorders are confined to the mouth, oral lesions may be a sign of a systemic medical disorder. The majority of oral pathology seen in children is benign; however, it is essential to identify or eliminate more serious conditions. The presentation of pathology in children is often different from adult pathology and the subtleties of these differences are often important in diagnosis. In addition, many lesions change in form or extent with growth of the body. In this chapter, conditions will be grouped according to presentation, followed by a review of the most common causes and management of orofacial infections. It is important to remember that one disease entity may have different presentations while one presentation, e.g. an ulcer, may be representative of many different diseases.

Orofacial infections

Differential diagnosis

Odontogenic infections

The basic signs and symptoms of oral infection should be familiar to all clinicians.

Acute infection usually presents as an emergency:

Chronic infection typically presents as an asymptomatic or indolent process:

Presentation

• Children tend to present with facial cellulitis rather than an abscess with a large collection of pus. The child is usually febrile. Pain is common, although if the infection has perforated the cortical plate the child may not be in pain. The mainstay of treatment is removal of the cause of the infection. Too often, antibiotics are prescribed without consideration of extraction of the tooth or extirpation of the pulp.

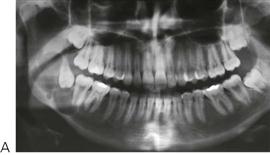

• Maxillary canine fossa infections are predominantly Gram-positive or facultative anaerobic infections (Figure 10.1A). They may be misdiagnosed as a periorbital cellulitis (which is typically caused by Haemophilus influenzae or Staphylococcus aureus from haematogenous spread). Posterior spread may lead to cavernous sinus thrombosis and a brain abscess.

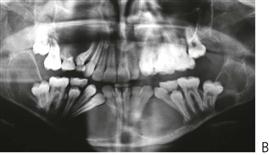

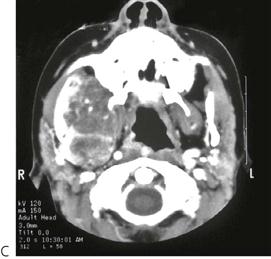

Figure 10.1 Severe facial swellings associated with odontogenic infections. (A) The right eye was almost closed from the spreading infection. (B) This child required extra-oral drainage of the facial swelling, which was caused by involvement of the floor of mouth as well as the submandibular and sublingual spaces. He required hospitalization and was placed on high-dose intravenous penicillin supplemented with metronidazole. (C) Extra-oral drainage of a long-standing abscess. Although this child was placed on repeated courses of antibiotics, no attempt was made to remove the cause of the infection, namely a carious tooth. (D) Healing 24 h after removal of the mandibular left first permanent molar tooth and debridement of the sinus tract draining sinus.

• Mandibular infections which spread inferiorly may compromise the airway and there is the possibility of mediastinal involvement.

• Young patients may be dehydrated at presentation. It is important to ask about their fluid intake and ascertain whether the child has urinated during the previous 12 h (see Appendix B).

Management

The treatment of infection follows two basic tenets:

Use of antibiotics

• Antibiotics should not be considered automatically as a firstline of treatment unless there is systemic involvement. In a child, a temperature of 39°C or higher can be considered a significant rise (normal ~37°C).

• If a child has a systemic infection resulting from a local focus of dental infection i.e. a sick child with a high temperature, an obvious spreading infection of the face and regional lymphadenopathy, antibiotics should be administered.

• Immunosuppressed patients or those with cardiac disease should receive antibiotics if infection is suspected.

General considerations

• Extraction of involved teeth.

Or

• Root canal treatment for permanent teeth if it is considered important to save particular teeth (see Chapter 7).

Amoxicillin is usually the drug of first choice. This has the advantage that it is given only three times a day, achieves higher blood levels and is a more effective antibiotic than, e.g. phenoxymethylpenicillin (Penicillin VK). Often the extraction of the abscessed tooth alone will bring about resolution without antibiotic treatment.

Severe infections

• Extraction of involved teeth. It is impossible to drain a significant infection solely through the root canals of a primary tooth.

• Drainage of any pus present. If the diagnosis or the correct management of an infection in the mandible has been delayed and the swelling has crossed the midline, or if there is swelling of the floor of the mouth, then extra-oral drainage with a through-and-through drain should be considered (Figure 10.1B). If a flap is raised, any granulation tissue should be removed and the area well irrigated. Flaps should be apposed but not tightly sutured. Soft flexible drains such as Penrose drains are better tolerated in children than are corrugated drains.

• Swabs for culture and sensitivity. It is important to take specimens for culture, even though empirical antibiotic treatment needs to be commenced immediately. Should the infection not respond to the initial antibiotic treatment, the results of the culture and sensitivity tests can be used to determine subsequent management.

• Intravenous antibiotics. Benzylpenicillin is the drug of first choice (up to 200 mg/kg per day).

• First-generation cephalosporins may be used as an alternative. However, if the child is allergic to penicillin, there may be cross-allergenicity and in these cases, it would be prudent to avoid cephalosporins. In these cases, clindamycin would be a better choice.

• In severe infections, particularly deep-seated infections and those involving bone, metronidazole can be added. The flora of most odontogenic infections is of a mixed type and anaerobic organisms are thought to have a significant role in their pathogenesis.

• For any antibiotics administered, adequate doses must be used – treat serious infections in the head and neck seriously.

• Maintenance fluids, adding 10–12% for every degree over 37.5°C, until the child is drinking of their own accord.

• Give 0.2% chlorhexidine gluconate rinses.

• Give adequate pain control with paracetamol suspension (orally), 15 mg/kg, 4-hourly, or by suppository (rectally).

• If the eye is closed because of collateral oedema, it may be appropriate to apply 0.5% chloramphenicol eye drops or 1% ointment to prevent conjunctivitis.

Osteomyelitis

Rarely, odontogenic infection may lead to osteomyelitis, most commonly involving the mandible. Radiographically, the bone has a ‘moth-eaten’ appearance. Curettage of the area is required to remove bony sequestra and antibiotics are given for at least 6 weeks, depending on the results of microbiological culture and sensitivity test results. A variant of osteomyelitis has been reported in children and adolescents, termed juvenile mandibular chronic osteomyelitis. In this condition, there is often no obvious odontogenic source of infection; there is limited response to a number of different treatment modalities.

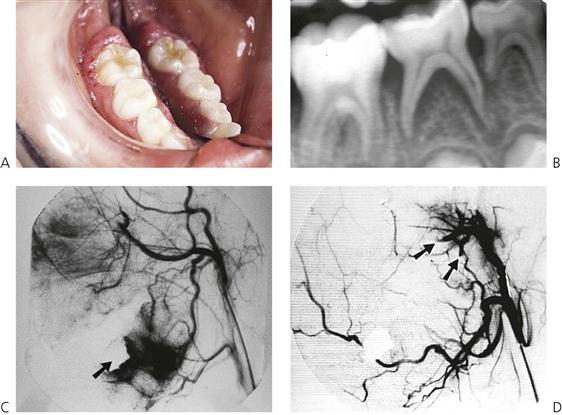

Primary herpetic gingivostomatitis (Figure 10.2)

This is the most common cause of severe oral ulceration in children. It is caused by herpes simplex type 1 virus. Occasional cases of type 2 (the usual cause of genital herpes) infection have been reported, mainly in cases of sexual abuse. The clinical appearance of the two different strains of herpes simplex virus are, however, clinically identical in the orofacial region. Although the majority of the population has been infected with the virus by adulthood, less than 1% manifest an acute primary infection. This usually occurs after 6 months of age, often coincident with the eruption of the primary incisors. The peak incidence is between 12 and 18 months of age. Incubation time is 3–5 days with a prodromal 48-h history of irritability, pyrexia and malaise. The child is often unwell, has difficulty in eating and drinking and typically drools. Stomatitis is present, with the gingival tissues in particular becoming red and oedematous. Intraepithelial vesicles appear and rapidly break down to form painful ulcers. Vesicles may form on any part of the oral mucosa, including the skin around the lips. Solitary ulcers are usually small (3 mm) and painful with an erythematous margin, but larger ulcers with irregular margins often result from the coalescence of individual lesions. The disease is self-limiting and the ulcers heal spontaneously without scarring, within 10–14 days.

Figure 10.2 Different presentations of primary herpetic gingivostomatitis. (A) Infection with primary herpes often occurs at the time of eruption of primary teeth. (B) Common presentation with multiple small ulcers on the lower lip, and gingival swelling and inflammation.

Diagnosis

• History and clinical features.

• Exfoliative cytology showing the presence of multinucleated giant cells and viral inclusion bodies can be used for rapid diagnosis if laboratory support is at hand.

• Viral antigen can be detected by polymerase chain reaction (PCR) amplification. This can sometimes be useful in early confirmation of the diagnosis.

• Viral culture. Viral culture can take days or weeks to yield a result.

• Viral antibody detection in blood samples during the acute and convalescent phases. A rise in antibody titre can only provide late confirmation of the diagnosis.

Management

• If oral fluids cannot be taken then hospital admission is mandatory and intravenous fluids must be commenced.

• Analgesics – paracetamol, 15 mg/kg, 4-hourly.

• Mouthwashes for older children – chlorhexidine gluconate, 0.2%, 10 mL 4-hourly. In children over 10 years of age, tetracycline or minocycline mouthwashes may be beneficial, but must be avoided in younger children to prevent possible tooth discolouration.

• In young children with severe ulceration, chlorhexidine can be swabbed over the affected areas with cotton wool swabs. Much of the pain from oral ulceration is probably as a consequence of secondary bacterial infection. Chlorhexidine 0.2% mouthwash has been shown to be beneficial in the management of oral ulceration. A mouthwash containing benzydamine hydrochloride 0.15% and chlorhexidine 0.12% (Difflam C™) may offer some advantages over chlorhexidine alone.

• Topical anaesthetics: lignocaine viscous 2% or lignocaine (Xylocaine™) spray.

Note: topical anaesthetics are often advocated; however, the effect of a numb mouth in a young child can be more distressing than the pain from the illness and can lead to ulceration from the decrease in sensation and subsequent trauma. In addition, it is often difficult to initiate swallowing with a soft palate that has been anaesthetized.

• Antiviral chemotherapy. Acyclovir oral suspension or intravenously for immunosuppressed patients. This treatment is only worthwhile in the vesicular phase of the infection, i.e. within the first 72 h.

Note: the use of antiviral medications is contentious and usually reserved for children who are immunocompromised. There is some evidence to suggest, however, that the administration of aciclovir in the first 72 h of the infection may be beneficial.

• Adequate pain control is also required with regular administration of paracetamol.

• Severely affected young children often present dehydrated, being unable to eat or drink. Hospital admission is required for these cases with maintenance intravenous fluids.

Herpangina and hand, foot and mouth disease

These infections are caused by the Coxsackie group A viruses. As with primary herpes, both of the above conditions have a prodromal phase of low-grade fever and malaise that may last for several days before the appearance of the vesicles. In herpangina (Figure 10.3A), a cluster of four to five vesicles are usually found on the palate, pillars of the fauces and pharynx, whereas in hand, foot and mouth disease up to 10 vesicles occur at these sites and elsewhere in the mouth, in addition to the hands and feet (Figure 10.3B). The skin lesions appear on the palmar surfaces of the hands and plantar surface of the feet and are surrounded by an erythematous margin. The severity of both diseases is usually milder than primary herpes and healing occurs within 10 days. Both diseases occur in epidemics, mainly affecting children.

Infectious mononucleosis (Figure 10.4A)

• This infection is caused by the Epstein–Barr virus (EBV) and mainly affects older adolescents and young adults. The disease is highly infective and is characterized by malaise, fever, lymphadenopathy and acute pharyngitis. In young children, ulcers and petechiae are often found in the posterior pharynx and soft palate. The disease is self-limiting.

Varicella (Figure 10.4B)

This is a highly contagious virus causing chickenpox in younger subjects and shingles in older individuals. There is a prodromal phase of malaise and fever for 24 h followed by macular eruptions and vesicles. In chickenpox, oral lesions occur in around 50% of cases but only a small number of vesicles occur in the mouth. These lesions may be found anywhere in the mouth in addition to other mucosal sites such as conjunctivae, nose or anus. Healing of oral lesions is uneventful.

Measles

Measles is a highly contagious paramyxovirus infection, predominately of childhood that presents as an acute febrile illness, a maculopapular rash, keratoconjunctivitis, malaise, cough and the characteristic oral lesions – Koplik’s spots. These are small white papules surrounded by an erythematous margin and cover the buccal mucosa. They usually precede the typical measles rash by up to 4 days. The incubation period is 8–12 days with a prodromal phase of malaise, fever, cough and the oral signs. Healing of oral lesions is uneventful; however, some children may suffer other complications of the disease such as pneumonia (1 in 20) or encephalitis (1 in 1000).

Candidosis

Acute pseudomembranous candidosis

The most common presentation of candidal infection in infants is thrush. White plaques are present, which on removal reveal an erythematous, sometimes haemorrhagic, base. In older children, thrush occurs when children are immunocompromised such as in acquired immune deficiency syndrome (AIDS) or in diabetes, or when prescribed antibiotics, steroids, or during chemotherapy and radiotherapy for malignancies.

Median rhomboid glossitis

This characteristic but uncommon lesion, is a candidosis (rather than a developmental anomaly as was thought for many years) presenting as an erythematous, depapillated well-delineated area on the midline of the dorsal surface of the tongue anterior to the circumvallate papillae, often in children in response to the use of antibiotics.

Diagnosis

Some 50% of children will have Candida albicans as a normal commensal, and culture is of little benefit. Smears or scrapings for exfoliative cytology reveal hyphae when disease is present, but the clinical picture may be diagnostic.

Management

• Antifungal medication for 2–4 weeks. Most antifungal treatment is unsuccessful because of poor compliance or instruction by the clinician.

• Amphotericin B lozenges or nystatin drops.

• Fluconazole orally (100 mg daily for 14 days) for cases of mucocutaneous candidosis.

• Systemic antifungal medication may need to be used for children who are immunosuppressed or where the organism does not respond to topical treatment as described above.

Ulcerative and vesiculobullous lesions

Clinicians are often confused regarding the terminology of these lesions. An ulcer is regarded as the localized loss of the full-thickness of the epithelium. Partial thickness loss is termed an erosion. A vesicle is a small fluid-filled blister, while a bulla is a larger blister, generally, measuring >5 mm. Different conditions arise from cleavage of the epithelium at different levels (i.e. intraepithelial or subepithelial) and are important in determining a diagnosis. When these lesions burst, they leave an ulcer. A thorough history noting the number, frequency, duration and site of occurrence is very important.

Differential diagnosis

Lip ulceration after mandibular block anaesthesia

This is one of the most common causes of traumatic ulceration. Parents should be warned and children reminded not to bite their lips after mandibular block anaesthesia (Figure 10.5A).

Figure 10.5 (A) Traumatic oral ulceration from biting the lip after a mandibular block injection. (B) Riga–Fedé ulcer on the ventral surface of the tongue arising from rubbing on the solitary mandibular incisor. (C) Chemical burn from an antihistamine tablet placed under the tongue in an adolescent. (Courtesy Ms Leanne Smith, Uni Newcastle.)

Riga–Fedé ulceration

This is ulceration of the ventral surface of the tongue caused by trauma from continual protrusive and retrusive movements over the lower incisors (Figure 10.5B). Once a common finding in cases of whooping cough, it is now almost exclusively seen in children with cerebral palsy.

Management

Smoothen sharp incisal edges or place domes of composite resin over the teeth. Rarely, in severe cases, extraction of the teeth might be considered (see also Chapter 13).

Recurrent aphthous ulceration (Figure 10.6)

Recurrent aphthous ulceration (RAU) has been estimated to affect up to 20% of the population. Lesions are classification according to size, duration and severity. Two clinical groups have been described:

• Major aphthae (Figure 10.6B).

• This fourth form – complex aphthous stomatitis has recently been described.

Minor aphthae account for the majority of cases, with crops of two to five shallow ulcers measuring up to 5 mm and occurring on non-keratinized mucosa. There is a typical central yellow slough with an erythematous halo. Ulcers heal within 10–14 days without scarring. The cause of RAU is contentious, although it is commonly believed to be precipitated by stress and local trauma. There is some evidence for a genetic basis for the disorder, with an increased incidence of ulceration in children when both parents have RAU. Some studies have suggested that RAU is associated with nutritional deficiency states and so haematological investigation can be helpful. In major aphthae, the keratinized mucosa may also be involved, the ulcers are larger, last longer and heal with scarring.

Figure 10.6 (A) Minor recurrent aphthae in an adolescent girl. These lesions were extremely painful. Haematological investigations revealed a low folate level, which when corrected eliminated further ulceration. (B,C) Major recurrent aphthous ulceration is a debilitating condition and heals with scarring. This girl’s ulcers were managed with systemic steroids. (D) Vesiculobullous diseases often present with ulceration due to fragility of the preceeding vesicles or bullae. This is a case of ulceration associated with Epidermolysis bullosa.

Complex aphthous stomatitis accounts for less than 5% of cases that are recurrent, with multiple lesions that are extremely painful and are slow to heal. The differences between simple and complex forms are summarized in Table 10.1.

Table 10.1

Presentation of aphthous stomatitis

| Simple | Complex | |

| Frequency | Episodic; <6 episodes per year | Continuous rather than episodic; >6 episodes per year |

| Duration | Short-lived | Persistent |

| Number | Few/limited number of lesions | Many, rather than few lesions |

| Healing | Rapid healing and generally heal without scarring except for major aphthae | Slower to heal with scarring |

| Location | Generally confined to non-keratinized mucosa | Can involve both keratinized and non-keratinized mucosa |

| Pain | Minimal pain/discomfort with minimal disability | Extremely painful and disabling |

| Geography | Limited to oral mucosa | May have genital involvement Need to exclude Behçet’s disease |

Modified from Rogers, R.S. 3rd, 1997. Recurrent aphthous stomatitis: clinical characteristics and associated systemic disorders. Seminars in Cutaneous Medicine and Surgery 16, 278–283.

Management

• Symptomatic care with mouthrinses:

• Chlorhexidine gluconate 0.2%, 10 mL three times daily.

• Minocycline mouthwash, 50 mg in 10 mL water three times daily for 4 days for children over 8 years of age.

• Benzydamine hydrochloride 0.15% and chlorhexidine 0.12% (Difflam C™).

• Triamcinolone in Orabase™ (although this may be difficult to apply in children).

• Beclomethasone dipropionate or fluticasone propionate asthma inhalers sprayed onto the ulcers.

• Betamethasone dipropionate 0.05% (Diprosone OV) ointment.

• Systemic corticosteroids only in most severe cases of major aphthous ulceration.

• Herpetiform ulceration seems to respond best to minocycline mouthwashes.

Biopsy should only be considered if there is any doubt about the clinical diagnosis. Haematological investigations should be carried out to exclude anaemia or haematinic deficiency states (when appropriate, replacement can improve the ulceration or bring about resolution). As with all oral ulceration, symptomatic care with appropriate analgesics and antiseptic mouthwashes is appropriate. In those cases of severe recurrent oral ulceration, systemic corticosteroids may be used, although their use is best avoided in children. Minocycline mouthwashes should not be used in children under the age of 8 years to avoid tooth discolouration. Major aphthae tend to occur in older children.

Behçet syndrome

This condition is characterized by recurrent aphthous ulceration together with genital and ocular lesions, although the skin and other systems can also be involved. Lesions may affect other parts of the body. Behçet syndrome can be subdivided into four main types:

• Mucocutaneous form – classical form with involvement of oral and genital mucosa and conjunctiva.

• Arthritic form with arthritis in association with mucocutaneous lesions.

• Neurological form with central nervous system involvement.

• Ocular form with uveitis in addition to oral and genital lesions.

Management

As for recurrent aphthous ulceration, but systemic treatment (corticosteroids) is usually required.

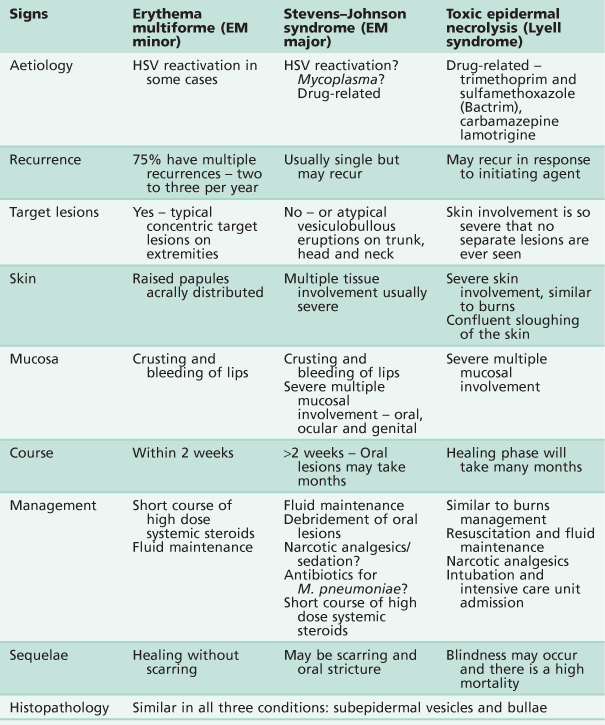

Erythema multiforme, Stevens–Johnson syndrome and toxic epidermal necrolysis

Three conditions exist that present with similar clinical signs and histopathological appearances. Like many conditions, varied nomenclature and misdiagnosis have clouded and confused the diagnosis/es. There is now a view that these are distinct pathological entities and, perhaps importantly, might be initiated by quite distinct aetiological agents. The alternative view is that these disorders represent different presentations of the same basic disorder, distinguished by the severity and extent of the lesions.

Erythema multiforme (von Hebra) (Figure 10.7A–D)

The original description of erythema multiforme was that of a self-limiting but often recurrent and seasonal skin disease with mucosal involvement limited to the oral cavity. The lips are typically ulcerated with blood-staining and crusting. The characteristic macules (‘target lesions’) occur on the limbs but with less involvement of the trunk or head and neck. These lesions are concentric with an erythematous halo and a central blister. Although the lesions are extremely painful, the course of the illness is benign and healing is uneventful.

Figure 10.7 (A) Erythema multiforme presenting with pan-stomatitis and severe dehydration. Treatment included rehydration and symptomatic care of the ulceration. (B) Typical target lesions seen in erythema multiforme. (C) Ulceration of the lips may be severe, and resulted in the lips becoming fused together by the slough and crusting in this case. (D) The mouth was debrided under general anaesthesia. (E) Stevens–Johnson syndrome with severe mucocutaneous involvement. This child required admission to the intensive care unit for 3 days. (F) Stricture of the lateral commissure of the lips due to scarring following an episode of Stevens–Johnson syndrome.

Stevens–Johnson syndrome (Figure 10.7E,F)

The condition presents with acute febrile illness, generalized exanthema, lesions involving the oral cavity and a severe purulent conjunctivitis. The skin lesions are more extensive than those of erythema multiforme. Stevens–Johnson syndrome is characterized by vesiculobullous eruptions over the body, in particular the trunk, and severe involvement of multiple mucous membranes including the vulva or penis and conjunctiva. The course of the condition is longer and scarring may occur. Some authors have used the term erythema multiforme major for Stevens–Johnson syndrome, defining the condition as a severe form of erythema multiforme, but this is disputed by others. Although Stevens–Johnson syndrome patients are acutely ill, death is rare.

Toxic epidermal necrolysis (TEN)

Similar to the clinical presentation of Stevens–Johnson syndrome, TEN or Lyell syndrome is a severe, sometimes fatal, bullous drug-induced eruption where sheets of skin are lost. It resembles third-degree burns or staphylococcal scalded skin syndrome. Oral involvement is similar to Stevens–Johnson syndrome. TEN may be misdiagnosed as a severe form of Stevens–Johnson syndrome (given the controversy over nomenclature), but the use of steroids is contraindicated, given an increase in mortality with their use in this disease.

Aetiology

Erythema multiforme is often initiated by herpes simplex reactivation. There is some evidence that Stevens–Johnson syndrome is initiated by a Mycoplasma pneumoniae respiratory infection or drug reaction. TEN is drug-induced.

Clinical presentation

A summary of the three conditions is shown in Table 10.2. There is an acute onset of fever, cough, sore throat and malaise, followed by the appearance of the lesions on the body and oral cavity ranging from 2 days to 2 weeks after the onset of symptoms. These break down quickly in the mouth to form ulcers. The most striking feature is the degree of oral mucosal involvement that may lead in all three cases to a pan stomatitis and sloughing of the whole oral mucosa. There is extensive ulceration and crusting around the lips, oral haemorrhage and necrosis of skin and mucosa leading to secondary infection. There may be difficulty in eating and drinking, which complicates the clinical course, and there is usually extreme discomfort from both the skin and oral lesions that may necessitate narcotic analgesics.

Management

If there is a known precipitating factor such as herpes simplex infection, then antivirals such as topical aciclovir can be used in an attempt at prophylaxis. Management is generally symptomatic and supportive. A major problem during the course of the illness is fluid balance and pain, much of which arises from secondary infection of the oral lesions. Debridement of the oral cavity with 0.2% chlorhexidine gluconate or benzydamine hydrochloride and chlorhexidine (Difflam C™) is effective in removing much of the necrotic debris from the mouth. Extensive areas of ulceration tend to be less responsive to chlorhexidine and a minocycline mouthwash may prove more effective. The role of systemic steroids is controversial but they may be necessary in severe cases. Their use in recurrences may obviate the need for hospital admission.

Management also includes:

Pemphigus

Pemphigus is an important vesiculo-bullous disease mainly affecting adults; however, children can be also affected. The lesions are intraepithelial and rapidly break down, so that affected individuals are often unaware of blistering, complaining instead of ulceration, mainly affecting the buccal mucosa, palate and lips.

Diagnosis

There may be a positive Nikolsky sign (separation of the superficial epithelial layers from the basal layer produced by rubbing or gentle pressure) and cytological examination can reveal the presence of Tzanck cells. Direct immunofluorescence using frozen sections from an oral biopsy will reveal intercellular immunoglobulin (IgG) deposits in the epithelium that are diagnostic for this disease. Indirect immunofluorescence on blood samples is used to complement diagnosis.

Management

• Systemic corticosteroid therapy in conjunction with steroid-sparing agents.

• Topical corticosteroids are used for oral lesions.

• Antiseptic or minocycline mouthwashes and analgesia as necessary.

All of these mucocutaneous conditions in children heal with scarring and are managed similarly.

Epidermolysis bullosa (Figure 10.6D)

Epidermolysis bullosa is a term used to describe several hereditary vesiculo-bullous disorders of the skin and mucosa. Within the hereditary variants, there are three groups according to the location of skin separation:

• Epidermolysis Bullosa Simplex, non-scarring form, transmitted as an autosomal dominant or sex-linked trait.

• Junctional Epidermolysis Bullosa, with demi-desmosome defect and severe scarring, transmitted as an autosomal recessive trait.

Another form which is not inherited, is termed Epidermolysis bullosa acquisita.

Blisters may form from birth or appear in the first few weeks of life, depending on the form of the disease. Corneal ulceration may also be present and pitting enamel hypoplasia has been reported, mainly in the junctional forms of the disease.

Management

Management is often extremely difficult because of the fragility of the skin and oral mucosa. Intensive preventive dental care is essential to prevent dental caries, combined with treatment of early decay. Supportive care is required with the use of chlorhexidine gluconate mouthwashes and possibly topical anaesthetics such as lignocaine (Xylocaine viscous™). Fortunately, children may receive dental treatment under general anaesthesia without laryngeal complications. Because of oral stricture, however, access into the mouth is often difficult and in older patients, surgical release of the commissure may be necessary. It is important to cover instruments with copious lubricant; the use of rubber dam is essential.

Systemic lupus erythematosus

Systemic lupus erythematosus is a chronic inflammatory multisystem disease occurring predominantly in young women. The hallmark of systemic lupus erythematosus is the presence of antinuclear antibodies which form circulating immune complexes with DNA. Oral ulceration often occurs in systemic lupus erythematosus and treatment of the condition usually involves systemic steroids.

Orofacial granulomatosis and Crohn disease (Figure 10.8)

Although not primarily an ulcerative condition, oral ulceration may be the presenting sign in orofacial granulomatosis. Orofacial granulomatosis may be confined to the orofacial region and precede or be a manifestation of Crohn disease, an inflammatory condition of the gastrointestinal tract, or of sarcoidosis.

Figure 10.8 Presentations of orofacial granulomatosis/Crohn disease. (A) The intra-oral appearance is pathognomonic with swelling of the gingivae, the patient also had a cobblestone appearance of the buccal mucosa and ulceration of the labial and buccal sulci. (B) A different presentation with bright red swollen gingivae. (C) The patient initially presented with a painless swelling of the lips and had evidence of malabsorption, perianal fissuring and bowel problems, and was diagnosed with Crohn disease. Management was with systemic corticosteroids. (D) Crohn disease. This child has recurrent flare-ups of his disease that is characterized by concurrent deterioration of his oral disease.

Presentation

• Diffuse swelling of the lips and cheeks, often initially recurrent and then becoming persistent.

• Diffusely swollen gingivae (Figure 10.8B).

• Linear ulceration or fissuring of the buccal and labial sulcus. A characteristic ‘cobblestone’ appearance of the buccal mucosa (Figure 10.8A).

• Polypoid tags of vestibular and retromolar mucosa.

• Children may also present with diarrhoea, failure to thrive, weakness, fatigue, anorexia and perianal fissuring or skin tags as manifestation of Crohn disease.

• Oral changes have been found in between 10% and 25% of patients with Crohn disease and, importantly, their appearance may precede other systemic symptoms.

Diagnosis

• Biopsy of oral lesions. The granulomas may be quite deep within the submucosa and if possible, a minor salivary gland should be included in the specimen.

• Full blood count, differential white cell count (to exclude leukaemia), erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) and C-reactive protein.

• Serum angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) level to identify or exclude sarcoidosis.

• Barium studies, endoscopy and biopsy of bowel if Crohn disease is suspected.

Management

• Some cases of orofacial granulomatosis have been shown to be a response to topical medicaments or dietary components. An exclusion diet can be considered to identify food intolerance, in particular cinnamon and benzoates.

Crohn disease

• Prednisolone. Corticosteroids are usually commenced at a high dosage (2–3 mg/kg daily for 6–8 weeks) to gain control of the disease and is then reduced. Clinicians should be aware of the significant adverse effects of high-dose and long-term use of corticosteroids in children.

• Dietary management for malabsorption.

More recently, methotrexate, budesonide and infliximab (a monoclonal antibody that neutralizes tumour necrosis factor alpha (TNF-α)) have also been used in the management of Crohn disease. Research continues into the use of paratuberculosis therapy (rifabutin, clarithromycin and clofazimine). Thalidomide is used by some clinicians for refractory adult cases, though this needs to be done with caution and female patients need a full explanation of the possible side-effects.

Melkersson–Rosenthal syndrome

Melkersson–Rosenthal syndrome is regarded by some as a form of orofacial granulomatosis.

Pigmented, vascular and red lesions

If a lesion is red or bluish in colour there should be the suspicion of a vascular lesion. These lesions will blanch on pressure with a glass slide (or end of a test tube if access is difficult) as the blood is removed from the vessels. Melanotic lesions are rare in children (other than racial pigmentation). A characteristic melanin-pigmented oral lesion in young children is the melanotic neuroectodermal tumour of infancy.

Differential diagnosis

• Racial pigmentation (Figure 10.9).

Figure 10.9 Racial pigmentation of the attached gingiva. This should not be confused with heavy metal toxicity which is limited to the marginal gingivae.

• Other vascular malformations.

• Hereditary haemorrhagic telangiectasia.

• Pigmented lesions (containing melanin):

• Melanotic neuroectodermal tumour of infancy.

• Other red/blue/purple lesions:

• Giant cell granuloma – peripheral (epulis) or central.

• Langerhans’ cell histiocytosis.

Lesions of vascular origin

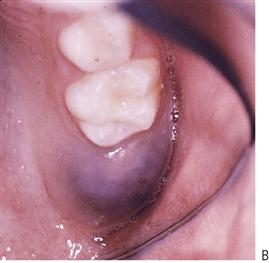

Haemangioma/localized vascular anomaly (Figure 10.10A,B)

Haemangiomas are endothelial hamartomas. Typically present at birth, they may grow with the infant but then may regress with time to disappear by adolescence. As such, they require no treatment other than observation, excepting cosmetic concerns.

Other vascular malformations

Arteriovenous malformations include birthmarks, blood vessel and lymphatic anomalies. These may be life-threatening conditions, which can occasionally present with profound haemorrhage. Arteriovenous malformations have been classified by Kaban and Mulliken (1986) according to their flow characteristics. They are either:

• Low-flow lesions – capillary, venous, lymphatic or combined port-wine stains, Sturge–Weber syndrome.

Or

• High-flow lesions – arterial with arteriovenous fistulae (Figures 10.10C, 10.11). Present with mobile and sometimes painful teeth, a bruit and palpable pulses, bleeding from gingivae and bony involvement.

Figure 10.11 A high-flow arteriovenous malformation in the mandible. (A) This child presented with an unusual erythematous enlargement of the gingivae around the mandibular right first permanent molar in addition to mobile second primary molar. (B) Periapical radiograph shows widening of the periodontal ligament space, but there are no indicative changes in the trabecular pattern of the bone. During the biopsy 350 mL (20% of total volume) of blood was lost after extraction of the second primary molar. The haemorrhage was controlled with an iodoform pack (arrowed). (C) Subsequently, an angiogram was ordered. The extent of the lesion inferior and posterior to the pack is seen. (D) The lesion was managed by embolizing the inferior alveolar and maxillary arteries (arrows) and the mandible was resected later.

• Combined lesions – extensive combined venous and arteriovenous malformations.

Diagnosis

• Presentation may be subtle, such as prolonged bleeding from the gingivae after tooth brushing, or alternatively a torrential single episode of haemorrhage.

• Vascular lesions are often warm to touch (although this can be difficult to determine if wearing latex gloves).

• Radiographically, there may be enlargement of the periodontal ligament space and a diffuse abnormal trabeculation of the bone.

• A bruit or pulse may be felt over high-flow lesions.

• Teeth may be hypermobile and may have pulsatile movements.

• Facial asymmetry may become apparent as lesions expand.

• Digital subtraction angiography (Figure 10.11C) is required for definitive diagnosis of feeder vessels and the distribution of the lesion.

• Magnetic resonance angiography can be used to aid diagnosis; however, digital subtraction angiography has the advantage that embolization can be performed at the same time.

Management

• Low-flow lesions can be removed by careful surgery with identification and ligation of feeder vessels. Larger lesions can be managed with cryotherapy, laser ablation or injection of sclerosing solutions.

• High-flow lesions require selective embolization of vessels, but these will generally recur after embolization due to revascularization from contralateral supply and recanalization of the embolized artery. Repeat embolization and resection of the entire lesion is often necessary involving jaw reconstruction.

• If a tooth is accidentally removed and a torrential haemorrhage results, some clinicians suggest that the extracted tooth should be immediately replaced and additional measures used to control the haemorrhage. These rare but potential life-threatening events call for urgent assistance and response.

Lymphangioma (Figure 10.12)

• Diagnosis of developmental lymph vessel abnormalities must exclude vascular involvement. Surgical excision is only necessary if of functional or aesthetic concern.

• Cystic hygroma (Figure 10.12C) is a term used to describe a large lymphangioma involving the tongue, floor of mouth and neck. Expansion of the lesion may cause respiratory obstruction and treatment usually involves multiple resections over time, management with laser ablation or cryosurgery.

Petechiae and purpura

Petechiae are small pinpoint submucosal or subcutaneous haemorrhages. Purpura or ecchymoses present as larger collections of blood. These lesions are usually present in patients with severe bleeding disorders or coagulopathies, leukaemia and other conditions such as infective endocarditis. Initially bright red in colour, they will change to a bluish-brown hue with time as the extravasated blood is metabolized.

Hereditary haemorrhagic telangiectasia (Rendu–Osler–Weber disease)

An autosomal dominant disorder presenting as a developmental anomaly of capillaries. Lesions may be small, flat or raised haemorrhagic nodules or spider naevi. Bleeding as a result of involvement of the gastrointestinal tract and respiratory tract can lead to chronic anaemia.

Sturge–Weber syndrome (Figure 10.13)

This syndrome typically presents with:

• Encephalotrigeminal angiomatoses.

• Calcification of the falx cerebri.

• Vascular lesions involve the leptomeninges and peripheral lesions appear along the distribution of the 5th nerve.

Extraction of teeth within regions of the affected jaws should be performed with caution and only after thorough investigation of the extent of the anomaly, although it has been reported that they are usually uncomplicated (see other vascular malformations above).

Maffucci syndrome

Presents with multiple haemangiomas and enchondromas of the small bones in the hands and feet. Only a small number of cases will manifest with oral lesions, mainly haemangiomas.

Melanin-containing lesions

Peutz–Jeghers syndrome

An autosomal dominant disorder manifesting as multiple small, pigmented lesions of oral mucosa and circum-oral skin appearing almost like dark freckles. There is an important association with intestinal polyposis coli which requires gastrointestinal investigation.

Red lesions

Eruption cyst or haematoma

Follicular enlargement appearing just prior to eruption of teeth. These lesions tend to be blue-black as they may contain blood. They usually require no treatment unless infected. The parents and child should be reassured and the follicle allowed to rupture spontaneously or it may be surgically opened if infected (Figure 10.14).

Hereditary mucoepithelial dysplasia

A rare disorder where there is a reduced number of desmosomes attaching the epithelial cells to each other. Lens cataracts, corneal lesions leading to blindness, skin keratosis and alopecia are associated with a fiery red mucosa involving both keratinized and non-keratinized mucosa. Diagnosis is confirmed by gingival and/or mucosal biopsy. Transmission electron microscopy is necessary to demonstrate the reduced number of desmosomes and amorphous intracellular inclusions. The oral lesions are usually asymptomatic. Loss of sight is progressive due to corneal vascularization. Corneal grafts are unsuccessful, as they too undergo vascularization.

Geographic tongue (Figure 10.15A)

This condition is also termed glossitis migrans, benign migratory glossitis, erythema migrans or ‘wandering rash of the tongue’. It presents as areas of depapillation and erythema with a heaped ‘serpentine-like’, keratinized margin on the lateral margins and dorsal surface of the tongue. It can be associated with a fissured tongue. The lesions appear as map-like areas (hence the ‘geographic’) and may change in their distribution over a period of time (hence the ‘migratory’). The areas affected may return to normal and new lesions appear at different sites on the tongue. Sometimes symptomatic, topical corticosteroids may be beneficial for those children in pain.

Figure 10.15 Lesions of the tongue. (A) Geographic tongue. (B) Fissured tongue associated with mild geographic tongue. (C) A large swelling (an ulcerated fibroepithelial hyperplasia) on the dorsal surface of the tongue with a central area of ulceration caused by a palatal expansion appliance (quad helix). (D) Acute pseudomembranous candidosis or thrush with typical white plaques on the dorsum of the tongue in an immunocompromised child.

Fissured tongue (Figure 10.15B)

Also termed plicated tongue, scrotal tongue, fissured tongue or lingua secta. The tongue in these patients is fissured, the fissures being perpendicular to the lateral border. Although this is usually considered a variation of normal, it is a commonly found condition in children with Down syndrome. Some patients with a fissured tongue will also have geographic tongue. Fissuring of the tongue is also a feature of Melkersson–Rosenthal syndrome.

Epulides and exophytic lesions

Differential diagnosis

Pyogenic granuloma

This misnamed lesion (i.e. no pus and no granulomas) is actually an ulcerated lobulated capillary haemangioma. Hence, these lesions tend to bleed easily and are covered with a thin fibrin membrane and may recur if not fully excised. They should be completely excised.

Fibrous epulis (Figure 10.16A)

One of the most common epulides that is seen in children resulting from an exuberant fibroepithelial reaction to plaque. Commonly arising from the interdental papillae and covered by epithelium, they range in colour from pink to red to yellow. Those appearing yellow are ulcerated.

Figure 10.16 Gingival swellings. (A) Fibrous epulis. (B) Peripheral giant cell granuloma/giant cell epulis. (C) Congenital epulis. (D) Epulis associated with angiomata in a child with tuberous sclerosis. (E) A papilloma in the palate of a young child. In this case the lesion was associated with viral warts on the extremities, hence this is assumed to be a viral papilloma. (F) Focal epithelial hyperplasia with the characteristic lesions on the slide of the tongue. (Courtesy Dr Charmaine Hall, Royal Children’s Hospital, Melbourne.)

Management

Oral hygiene and surgical excision. Lesions may recur, particularly if good oral hygiene is not maintained.

Giant cell granuloma – central or peripheral (epulis) (Figure 10.16B)

These lesions usually occur in the region of the primary dentition. The colour of these lesions tends to be dark purple. Bone loss of the alveolar crest can sometimes be observed as ‘radiographic cupping’. It is important to ensure that there is no intraosseous component radiographically as in this case the diagnosis would be a central giant cell granuloma. As with all giant cell lesions of the jaws, hyperparathyroidism should be considered in the differential diagnosis. True central lesions are typically aggressive and local resection may be required.

Squamous papilloma (Figure 10.16E)

A squamous papilloma is a benign neoplasm caused by the human papilloma virus (HPV), presenting as a cauliflower-like growth on the mucosa. The colour of the lesion depends on the degree of keratinization.

Management

Surgical excision, including the stalk and a border of normal tissue.

Viral warts (verruca vulgaris)

This is the cutaneous form of the HPV infection. Lesions may be single or multiple and may appear similar to the papilloma or as the common wart seen on the hands and fingers.

Management

Surgical excision. If multiple lesions are present extra-orally, dermatological management may also be required.

Heck’s disease (focal epithelial hyperplasia)

These pale white multiple exophytic lesions, commonly appearing on the side of the tongue or lips are also associated with HPV infection. In some children, there is a genetic predisposition to those who may be affected (types 13 and 32).

Congenital epulis (Figure 10.16C)

The congenital epulis is a rare benign lesion of unknown origin found only in neonates. Lesions are equally distributed between maxillary and mandibular arches and may be multiple in about 10% of reported cases; they are 10 times more common in girls than in boys. It arises from the gingival crest but is thought not to be odontogenic in origin. The swelling is characterized by a proliferation of mesenchymal cells with a granular cytoplasm and is usually pedunculated. There is controversy over the histogenesis of this lesion. The congenital epulis is histologically indistinguishable from the extra-gingival granular cell tumour, which is usually seen on the tongue. Immunohistochemically, the congenital epulis is S100 negative, whereas the granular cell tumour is positive for both CD68 and S100. It has been suggested that the congenital epulis is a non-neoplastic, perhaps reactive, lesion arising from primitive gingival perivascular mesenchymal cells with the potential for smooth muscle cytodifferentiation.

Alternative terminology

Congenital granular cell tumour, Neumann tumour, granular cell epulis, gingival granular cell tumour.

Management

Lesions often regress with time, although large lesions which interfere with feeding may require surgical excision. Large lesions are sometimes present at birth and may be life-threatening because of respiratory obstruction. The eruption of the primary dentition is unaffected by either surgical or conservative management, and recurrence is uncommon.

Tuberous sclerosis (Figure 10.16D)

Tuberous sclerosis is an autosomal dominant disorder characterized by seizures, mental retardation and adenoma sebaceum of the skin. Epulides or generalized nodular gingival enlargement may be present. Some of these may result from vascular malformations and may bleed profusely when excised. Hypoplasia of the enamel is often observed as surface pitting; this can be demonstrated particularly effectively by the use of disclosing solution.

Gingival enlargements (overgrowth)

Phenytoin enlargement (Figure 10.17A,B)

Not all patients taking phenytoin have gingival enlargement. Principally, there is enlargement of the interdental papillae. There may be delayed eruption of teeth because of the bulk of fibrous tissue present and ectopic eruption. Overgrowth has been suggested to result from decreased collagen degradation and phagocytosis, as well as increased collagen synthesis. Withdrawal of the drug will bring about resolution in all but severe cases. Oral hygiene is most important in controlling overgrowth, as there is always a component of plaque-induced gingival enlargement.

Figure 10.17 (A) Phenytoin-associated gingival enlargement. This initially involves the interdental papillae and then adjacent tissues. (B) The phenytoin-associated gingival enlargement can become so extensive as to cover the whole palate. An acute periodontal abscess was associated with this case. (C) Cyclosporin A-associated gingival enlargement in a child following end-stage renal failure and kidney transplantation. The enamel is malformed due to the effects of the renal disease. (D) Cyclosporin A-associated gingival enlargement in a child following heart transplantation. (E) Hereditary gingival fibromatosis.

Cyclosporine A-associated enlargement (Figure 10.17C,D)

A significant number of children now undergo kidney, liver, heart or combined heart/lung transplantation. The mainstay of immunosuppressive anti-rejection chemotherapy is cyclosporin A. Gingival overgrowth occurs in between 30% and 70% of patients and is not strictly dose-related but may be more severe if the drug is administered at an early age. Individual patients appear to have a threshold below which gingival overgrowth will not occur. Overgrowth appears to be higher in those HLA B37 positive patients and lower in HLA DR1 positive patients.

Nifedipine and verapamil enlargement

Both these drugs are calcium-channel blockers used to control coronary insufficiency and hypertension in adults; their main use in children is to control cyclosporin-induced hypertension after transplantation. An increase in the extra-cellular compartment volume is responsible for enlargement that occurs in addition to the enlargement caused by cyclosporin A, which is invariably used in these patients.

Hereditary gingival fibromatosis (Figure 10.17E)

Gingival enlargement may be a feature of several syndromes, some of which include learning disabilities. These syndromes may occur sporadically or as an autosomal dominant or an autosomal recessive trait.

Management

Gingivectomy or periodontal flap procedures as required to allow tooth eruption and maintain aesthetics. Histopathological examination of the excised tissue may assist in diagnosis of some of the rarer causes of syndromic gingival enlargement (e.g. juvenile hyaline fibromatosis).

Premature exfoliation of primary teeth

Premature loss of primary teeth is a significant diagnostic event. Most conditions that present with early loss are serious and a child presenting with unexplained tooth loss warrants immediate investigation. Teeth may be lost because of metabolic disturbances, severe periodontal disease, connective tissue disorders, neoplasia, loss of alveolar bone support or self-inflicted trauma.

Differential diagnosis

• Qualitative neutrophil defects:

• Ehlers–Danlos syndrome (Types IV and VIII).

• Langerhans’ cell histiocytosis.

• Self-injury (see Chapter 13):

Periodontal disease in children (Figure 10.18D)

Although gingivitis is not uncommon in children, periodontitis with alveolar bone loss is usually a manifestation of a serious underlying immunological deficiency. Two forms of periodontal disease in children, prepubertal periodontitis and juvenile periodontitis, are associated with characteristic bacterial flora including Actinobacillus actinomycetemcomitans, Prevotella intermedia, Eikenella corrodens and Capnocytophaga sputigena. The presence of these bacteria is thought to be related to decreased host resistance, specifically neutropenia or neutrophil function defects. Although B-cell defects show few oral changes, altered T-cell function will manifest with severe gingivitis, periodontitis and candidosis.

Figure 10.18 (A) Gross gingival inflammation in an adolescent with cyclic neutropenia. This girl lost most of her primary teeth by the age of 7 years. (B) Periapical radiographic survey showing the extent of bone loss and angular defects in another child with cyclic neutropenia. (C) Severe unexplained palatal ulceration in a child with a leucocyte adhesion defect. The maxillary left incisor exfoliated a short time later. (D) Prepubertal periodontitis, also associated with a leucocyte adhesion defect. It is important to assess normal eruption patterns and to be suspicious of loss of teeth in the absence of caries or other pathology. (E) Acute necrotizing ulcerative gingivitis (ANUG) in a 15-year-old boy, showing the characteristic destruction of the interdental papilla. ANUG is rare in children and only seen in those who are immunocompromised to debilitated.

Classification of periodontal diseases

Table 10.3 details the new terminology used to describe the different periodontal diseases. The new terminology for pre-pubertal periodontitis is now generalized aggressive periodontitis or periodontitis associated with systemic disease. However, in children, it is important to understand that ANY periodontal disease in a young child is associated with some form of immune dysfunction. While any classifications should aid in the description of a particular disease entity, it is essential for clinicians to understand what the different presentations and the pathogenesis of the disease.

Table 10.3

Terminology used to classify periodontal diseases

| Old terminology | Current terminology |

| Pre-pubertal periodontitis | Generalized aggressive periodontitis |

| Periodontitis associated with systemic disease | |

| Localized juvenile periodontitis | Localized aggressive periodontitis |

| Acute necrotizing ulcerative gingivitis (ANUG) | Necrotizing periodontal disease |

Research, Science and Therapy Committee, 2003. Periodontal diseases of children and adolescents. American Academy of Periodontology. Journal of Periodontology 74, 1696–1704.

Neutropenias and qualitative neutrophil defects

Cyclic neutropenia (Figure 10.18A,B)

In this condition, there is an episodic decrease in the number of neutrophils every 3–4 weeks. Peripheral neutrophil counts usually drop to zero and during this time, the child is extremely susceptible to infection. Recurrent oral ulceration often occurs when cell counts are low. Gingival and periodontal involvement occurs with the emergence of teeth and is progressive.

Leucocyte adhesion defect (Figure 10.18C,D)

A rare autosomal recessive condition associated with a reduced level of adhesion molecules on peripheral leucocytes resulting in severely reduced resistance to infection. The CD11/CD18 molecules are necessary for effective phagocytosis. Children present with delayed wound healing, persistent severe oral ulceration, cellulitis without pus formation, severe gingival inflammation, periodontitis and premature loss of primary teeth. Also present is a persistently high leucocytosis and reactive marrow, without evidence of leukaemia. One important indicator of this condition is late separation of the umbilical cord after birth.

Diagnosis

Diagnosis is confirmed by examining leucocytes for surface expression of CD11/CD18 markers using immunofluorescence techniques and cytofluorographic analysis.

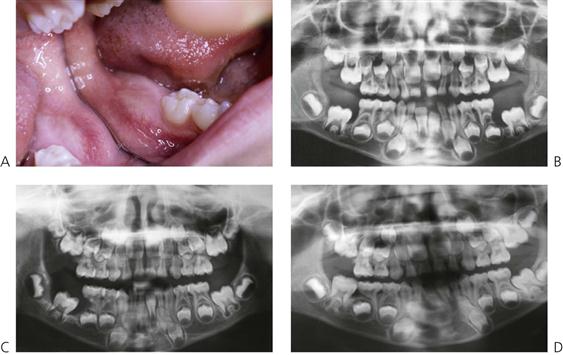

Papillon–Lefèvre syndrome (Figure 10.19)

An autosomal recessive condition manifesting as hyperkeratosis of the palms and feet and progressive exfoliation of all teeth from periodontal disease. A. actinomycetemcomitans has been implicated in the periodontal disease which is associated with a qualitative neutrophil defect and mutations in the lysosomal protease cathepsin C gene on 11q14–21. Primary teeth commence shedding from the time of eruption, with no evidence of root resorption. All primary teeth are usually lost before the permanent teeth erupt, when they in turn are exfoliated.

Figure 10.19 Papillon–Lefèvre syndrome. (A) The initial presentation of the child with severe periodontal disease-associated tooth mobility. Many of these teeth exfoliated within 6 months. (B,C) The characteristic appearance of the hands and feet in the same child. (D,E) The permanent dentition in a boy of 17 years, following long-term antibiotic treatment that has failed to improve the prognosis of the dentition.

Management

No treatment is particularly successful. Extraction of any remaining primary teeth before eruption of the permanent teeth has been advocated. Intensive periodontal therapy with metronidazole and chlorhexidine to eliminate or reduce A. actinomycetemcomitans may be successful in delaying the inevitable exfoliation of teeth, although the basic neutrophil function defect remains. Treatment of other family members has also been recommended, including pets (especially dogs) if they are found to harbour the bacteria. Several papers have reported the use of vitamin-A derivatives in management that may improve the prognosis. All patients require planned full clearances and dentures to avoid pain and disfigurement. It is important to consider proceeding with extractions soon after the eruption of the permanent dentition to minimize excessive bone loss.

Chédiak–Higashi disease

This is a rare autosomal recessive disorder affecting lysosomal storage and causing a qualitative neutrophil defect. There is defective neutrophil chemotaxis and abnormal degranulation that results in poor intracellular killing. Abnormal B-cell and T-cell function and thrombocytopenia have also been reported. Most children die by 10 years of age because of overwhelming sepsis. Teeth are shed because of severe periodontal disease with rapid alveolar bone loss.

HIV-associated periodontal disease in children

There are few cases documenting periodontal disease in young children. In adolescents, there are reports of acute necrotizing ulcerative gingivitis (ANUG) and a characteristic linear marginal gingival erythema. Excellent oral hygiene and plaque control are essential, combined with supportive therapy including chlorhexidine and metronidazole as required.

Langerhans’ cell histiocytosis (Figure 10.20)

This condition was previously termed histiocytosis X and included the conditions eosinophilic granuloma, Hand–Schüller–Christian disease and Letterer–Siwe disease. The abnormality in common is a proliferation of histiocytes. Oral lesions characteristically occur in all four quadrants and characteristically affect the tissues overlying or supporting the primary molar teeth. The lesions typically extend forward to the canines, but rarely involve the incisors.

Figure 10.20 (A) Cradle cap-like rash on the head and severe ano-vulval or ano-perineal rash are common presentations of disseminated Langerhans’ cell histiocytosis (LCH). LCH characteristically presents intraorally with lesions in all four quadrants (B) and (C). All the posterior teeth were excessively mobile and retained only by soft tissue. Note the perforation of the lesions through the lingual alveolus (C).

Metabolic disorders

Hypophosphatasia (Figure 10.21)

A decrease in serum alkaline phosphatase and an increase in the urinary excretion of phosphoenolamine (PEA) are pathognomonic for hypophosphatasia. The more usual form is transmitted as an autosomal dominant trait, whereas the autosomal recessive form is invariably lethal. Loss of at least some of the incisor teeth usually occurs before 18 months. Several authors have identified groups of children who manifest only dental changes, namely the early loss of teeth without any rachitic bone changes – the term ‘odontohypophosphatasia’ has been suggested for these patients but this is inappropriate as the presentation of loss of teeth alone is only one end of the spectrum in the variable expression of this disease. In these children there are less severe changes and we have observed that the permanent dentition can be unaffected.

Figure 10.21 (A) Hypophosphatasia presenting with exfoliation of the maxillary and mandibular anterior teeth around 2 years of age. There is minimal gingival inflammation and hard-tissue sections (B) show absence of cementum.

Diagnosis

• Serum alkaline phosphatase level <90 U/L. The normal range is 80–350 U/L, however, growing children often have levels well in excess of these values (>400 U/L).

• Urinary PEA and serum pyridoxal-5-phosphate (vitamin B6) tests are required to confirm the diagnosis. A skeletal survey of the long bones is necessary as rachitic changes may be present in severe cases.

• Sections of the exfoliated teeth show abnormal or absent cementum.

Ehlers–Danlos type IV and type VIII

These inborn errors of metabolism present as disorders of collagen formation. Typically, there is hyperextensibility of skin with capillary fragility, bruising of the skin and hypermobility of the joints. Types IV and VIII may present with dental complications, mainly progressive periodontal disease leading to the loss of teeth.

Erythromelalgia

A very rare condition, characterized by sympathetic overactivity, causing an endarteritis and the extremities feeling hot. One case has been reported with loss of primary and permanent teeth at 4 years of age. The child had extreme hypermobility of joints and slept on a tiled floor in the middle of winter because of the heat in her legs. She also had an unexplained tachycardia of 200 beats per minute and presented a diagnostic dilemma for many months. The teeth exfoliated because of necrosis of alveolar bone.

Acrodynia (pink disease)

Mercury toxicity causes alveolar destruction and sequestration. Extremely rare now, although in the past it was not uncommon with the use of teething powders containing mercury.

Acatalasia

Autosomal recessive catalase deficiency in neutrophils leading to periodontal destruction. Extremely rare outside Japan.

Scurvy

Almost unknown today, this nutritional deficiency of vitamin C results in a connective tissue disorder. Tooth loss is due to a failure of proline hydroxylation and consequent reduced collagen synthesis.

Oral pathology in the newborn infant

Cysts in the newborn (Figure 10.22A)

Epstein’s pearls

These hard, raised nodules are small keratinizing cysts arising in epithelial remnants trapped along lines of fusion of embryological processes. They appear in the midline of the hard palate, most commonly posteriorly.

Figure 10.22 Oral pathology in infants. (A) Bohn’s nodules in a newborn child (arrow). (B) Fibroepithelial hyperplasia on the ventral surface of the tongue caused by trauma from the erupting mandibular incisors. (C) White sponge naevus of the tongue. (D) Granular cell tumour. (E) Congenital epulis measuring 4 cm in length. (F) The lesion was diagnosed prenatally on ultrasound (arrow).

Bohn’s nodules

These are remnants of the dental lamina and usually occur on the labial or buccal aspect of the maxillary alveolar ridges.

Management

No treatment is required other than reassurance of the parents.

Melanotic neuroectodermal tumour of infancy

A rare but important paediatric tumour derived from neural crest cells, this occurs predominantly in the maxilla. The condition may be present at birth and all recorded cases have been diagnosed by 4 months of age. Similar to a neuroblastoma, there may be high levels of vanillylmandelic acid (a catecholamine end-product) in the urine. Lesions may be multicentric with close approximation to, but not involving, dental tissues, reflecting their ectomesenchymal origin. Intra-orally, lesions appear as circumscribed swellings that may have the appearance of normal mucosal or have a blue-black hue and may be associated with premature eruption of the primary incisors.

Diagnosis

Computed tomography followed by excisional biopsy because of the extremely rapid growth of the lesion. This condition is usually so unique, at this age and at this site, that diagnosis is not difficult.

Diseases of salivary glands

Mucocoele (Figure 10.23A,B)

Mucous extravasation cyst

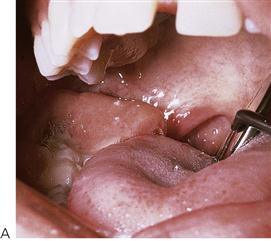

The most common mucous cyst in the oral cavity, the mucous extravasation cyst arises from damage to the duct of one of the minor salivary glands in the (lower) lip or cheek. Often caused by lip biting or other minor injuries, mucus builds up in the connective tissue to become surrounded by fibrous tissue. Most mucocoeles are well-circumscribed bluish swellings, although traumatized lesions may have a keratinized surface.

Figure 10.23 (A) Typical presentation of a mucocoele on the lower lip. Most lesions require removal. (B) Semilunar incision with exposure of cyst which may be removed with blunt dissection. (C) A mucous cyst of the floor of the mouth – a ranula. (D) Insertion of a Penrose drain lateral to Wharton’s duct to marsupialize the cyst.

Mucous retention cyst

Less common than the mucous extravasation cyst, the retention cyst has a similar or identical clinical appearance but is lined by epithelium. More common in the upper lip and palate, whereas the extravasation cyst is more typical of the lower lip.

Ranula (Figure 10.23C)

A mucous (extravasation) cyst of the floor of the mouth caused by damage to the duct of either the sublingual or submandibular glands. A soft, bluish swelling presents on one side of the floor of the mouth. A plunging ranula occurs when the lesion herniates through the mylohyoid muscle to involve the neck.

Sialadenitis

Inflammation of the major salivary glands may result from:

• Mumps or cytomegalovirus infection. Present with bilateral non-suppurative parotitis, usually epidemic.

• Human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection and AIDS; 10–15% of children with AIDS will manifest bilateral parotitis.

• Suppurative, usually retrograde infection.

• Sjögren syndrome (usually seen in older patients).

• Bilateral autoimmune parotitis. Punctate sialectasis appearance on sialogram.

• A non-tender salivary gland enlargement is a common presentation of bulimia nervosa.

• Usually caused by unilateral obstruction of a major salivary gland, either by stricture, epithelial plugging or a sialolith (calculus) causing obstruction and inflammation. Pain occurs during eating and if there is acute exacerbation of infection.

Management

• Massage of the gland/milking of the duct for cases of recurrent epithelial plugging.

• Antibiotics to control infection in the acute phase.

• Removal of sialolith. Note: a suture should be passed under the duct behind the sialolith to prevent it being displaced backwards.

• In longstanding cases of obstructive sialadenitis, removal of the gland may be necessary.

Salivary gland tumours

Most tumours of the salivary glands in children are vascular malformations. Pleomorphic adenomas are uncommon. Malignant neoplasms such as mucoepidermoid carcinoma, adenocarcinoma and sarcoma are extremely uncommon and affect mainly older children and adolescents. The parotid is the most common site for such tumours.

Diagnostic imaging of the salivary glands

Radiology

Mandibular occlusal films are useful for imaging salivary calculi in the submandibular duct. These may also be seen on panoramic radiographs, albeit with the mandible superimposed.

Sialography

Used to demonstrate a stricture of the duct and gland architecture.

Computed tomography, magnetic resonance imaging, ultrasound

If neoplasms are suspected. Can be combined with sialography.

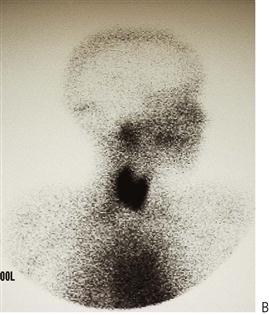

Nuclear medicine

Demonstrates salivary gland function. A technetium-99m tracer seeks major protein-secreting exocrine and endocrine glands. The isotope is readily taken up by the major salivary glands. Lemon juice then administered orally to assess function and clearance of the glands.

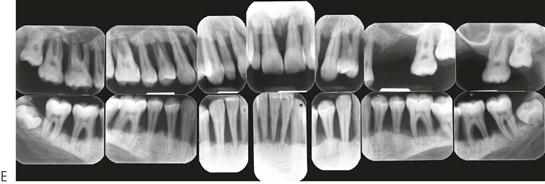

Aplasia of salivary glands (Figure 10.24)

A number of cases of congenital salivary gland agenesis have been reported. Major salivary gland hypoplasia is an uncommon presentation of a child with gross caries in unusual sites. Caries of the lower anterior teeth should be regarded with suspicion in a young child, as it may indicate aplasia of the submandibular glands. It is uncommon for children to be on medication that will cause severe xerostomia and so aplasia/hypoplasia should always be considered.

Figure 10.24 (A) Gross carious destruction of the mandibular anterior teeth. These are the only affected teeth. (B) The lateral nuclear medicine scan shows normal uptake of tracer in the parotid glands and thyroid but no function in the submandibular gland. A CT scan revealed that only rudimentary glands were present. (C) A 4-year-old boy who, after three procedures under general anaesthesia to treat gross caries in his primary dentition, was subsequently diagnosed with aplasia of his major salivary glands.

Diagnosis

Reduced uptake of technetium pertechnetate.

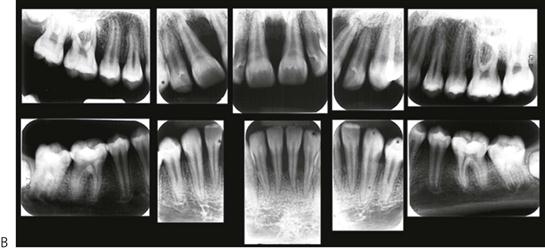

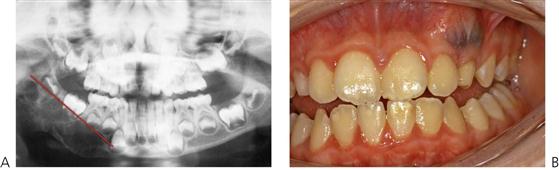

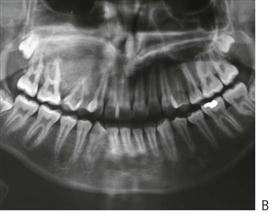

Differential diagnosis of radiographic pathology in children

The location, size and distribution of radiographic anomalies are important in determining a differential diagnosis. Slowly growing lesions will displace teeth within the jaws, while more aggressive or rapidly growing lesions may resorb teeth. It is also important to have due regard for adjacent structures and the anatomy of where a lesion might derive from and ultimately spread. Space occupying lesions in children are predominately sarcomas rather than carcinomas that are seen in adults.

The position of the lesion and the direction of the displacement of the tooth is important. Observing the radiograph, a line can be drawn through the cemento-enamel junction of the associated teeth. Lesions that arise coronal to this line are generally odontogenic in origin (see Figure 10.25). The tooth tends to be displaced away from the occlusal plane towards the cortical plates. Lesions apical to this line tend to be non-odontogenic. The body of the lesion tends to extend away from the teeth. Some lesions may have different presentations that change over time.

Figure 10.25 (A) Line drawn through the cemento-enamel junction of teeth associated with pathology in the jaws. Lesions apical to this line tend to be non-odontogenic in origin with the body of the lesion extending away from the teeth. Those lesions coronal to this line are usually odontogenic in origin. (B) A bluish-coloured swelling of a cyst associated with an unerupted upper left permanent canine. When managing lesions presenting with this colour, it is important to eliminate a lesion of vascular origin.

Descriptions of some of the following lesions have been covered in this section, while others will be discussed in other chapters of this book, as referred.

Periapical radiolucencies

Radiolucencies in the periapical region are usually associated with pulpal necrosis. All of these lesions tend to be inflammatory in origin but it is important to remember that healing lesions may appear similar to those that are active and sequential radiographs may be required to properly assess progression or healing. It is important to determine the integrity of the lamina dura around the apex of the tooth. Disruption or expansion of the periodontal ligament space indicates pathology.

Inflammatory lesions

• Periapical granuloma, abscess, surgical defect, scar.

• Transient apical breakdown post-luxation of an incisor tooth (see Chapter 9).

Radiolucencies associated with the crowns of teeth

Radiolucencies that are associated with the crowns of unerupted teeth are generally odontogenic.

• Dentigerous cyst (Figure 10.26).

The dentigerous or follicular cyst is the most common pathological entity associated with unerupted teeth. Some 75% are located in the mandible and usually present as a painless bony expansion and failure of eruption of the associated tooth that may be displaced a significant distance. The cyst enlarges by expansion from the increased hydrostatic pressure within the cavity. In early stages, it may be difficult to distinguish between an expanded follicle or a hyperplastic dental follicle. In some cases, the cyst lining becomes contiguous with the oral epithelium, forming an eruption cyst. The cyst is usually covered by a very thin wall of bone but the cortical plate invariably remains intact. Aspiration typically reveals a straw-coloured fluid containing cholesterol crystals.

The cyst lining represents a metaplastic change of the reduced enamel epithelium and histologically, is seen as thin, non-keratinized, stratified squamous epithelium but flattened or low cuboidal cells typical of the reduced enamel epithelium may be seen along with islands of odontogenic epithelial rests. Some cysts show inflammatory changes and when there is communication with the oral cavity, the cyst cavity may be infected. The epithelium of a dentigerous cyst may undergo neoplastic transformation. Treatment is by enucleation of marsupialization (Figure 10.26C&D).

Figure 10.26 An unusual case of bilateral dentigerous cysts associated with the both lower first permanent molars. (A) Uninflamed swelling distal to the second primary molar. (B) Radiographic changes showing expansion of the follicle and resorption of the root of the lower left second primary molar. (C) A large dentigerous cyst around the crown of the tooth 46. This was managed by marsupialization. (D) The appearance 6 months post surgery showing bony infill and eruption of the tooth.

• Inflammatory follicular cyst (Figure 10.27) (see Chapter 11).

Figure 10.27 Inflammatory follicular cyst. The necrotic lower left second primary molar has caused inflammatory changes in the follicle of the premolar with displacement of this tooth.

• Eruption cyst (see Chapter 11).

• Paradental cyst (Figure 10.28).

The paradental cyst is an inflammatory odontogenic cyst usually seen on the buccal aspect of lower molars. It is thought to arise from the cell rests of Malassez. When there is a communication with the oral environment due to partial eruption or pericoronitis, the cyst becomes infected and actinomyces species and other anaerobic microorganisms are frequently found. However, this is not classified as ‘actinomycosis’, which is a soft tissue lesion with characteristic yellow sulphur granules.

Figure 10.28 Paradental cyst. (A) A deep pocket on the buccal of a newly erupted lower right first permanent molar. (B) The true mandibular occlusal film shows the expansion of the buccal cortical plate and the associated bone loss with this cyst.

• Odontogenic keratocyst (Keratocystic odontogenic tumour (KCOT)).

The odontogenic keratocyst (OKC) was re-categorized as a true neoplasm by the WHO in 2005. It is locally aggressive and has a very high risk of recurrence reported to be between 3 to 60%. Approximately 70% of these lesions occur in the mandible with the typical presentation similar to a dentigerous cyst with painless expansion, however, it may appear in association with the crown of an unerupted tooth, as an isolated radiolucency, as a multilocular lesion or as multiple isolated lesions. Radiographically, they have smooth well-demarcated borders but are locally invasive and the cortical plate may be perforated or in the maxilla, the lesion may extend into the antrum. Histologically, there is a parakeratinized stratified squamous epithelial lining with a relatively flat epithelial-mesenchymal junction. The contents of the cyst have been described as caseous or having a yellow, cheese-like consistency and hence aspiration is essential prior to surgical intervention.

Due to the aggressive nature of the OKC, a more radical treatment approach is advised. Recurrence is due to the budding of daughter cysts from the basal layer, an increased mitotic activity of the epithelium and local invasion of surrounding bone. While marsupialization and enucleation with curettage have similar rates of recurrence there is not the surgical morbidity associated with resection. More recently, application of the fixative Carnoy’s solution (60% ethanol, 30% chloroform and 10% glacial acetic acid) has shown some promise in reducing recurrence with these lesions.

• Adenomatoid odontogenic tumour (Figure 10.29).

The AOT is a benign slowly-growing unilocular lesion that presents as a well circumscribed radiolucency in maxilla or mandible. There may be islands of calcification within the lesion accounting for either a radiolucent or mixed radiographic presentation. There is contention as to whether this is a true tumour or a hamartoma, as they never recur. Management is by enucleation.

Separate isolated radiolucencies

Odontogenic cysts and tumours

• Ameloblastic fibroma (Figure 10.30) (see also Chapter 11).

The ameloblastic fibroma is a slowly growing, mixed odontogenic tumour containing both epithelial and mesenchymal tissues. If dentine is identified in the specimen, then the lesion is classified as an ameloblastic fibro-dentinoma and tends to occur in young children.