Pulp therapy for primary and immature permanent teeth

John Winters, Angus C Cameron and Richard P Widmer

Introduction

Dental caries, trauma and the iatrogenic effects of conservative dental treatment, all provoke a biological response in the pulpo-dentinal complex. This chapter is concerned with the cascade of therapeutic interventions used to promote an adaptive biological response in the pulpo-dentinal complex of the treated tooth, and optimize subsequent growth and development. Therapeutic efforts are directed towards the retention of carious or traumatized teeth, maintaining normal function, with the resolution of, or freedom from, clinical symptoms.

Role of primary teeth

As mentioned in the last chapter, primary teeth play an integral role in the development of the occlusion. Premature loss of a primary tooth through trauma or infection has the potential to destabilize the developing occlusion with space loss, arch collapse and premature, delayed or ectopic eruption of the permanent successor teeth. In general, the effects of early extraction of primary teeth are more profound in the buccal segments than in the anterior dentition.

Effective pulpal therapy in the primary dentition must not only stabilize the affected primary tooth, but also create a favourable environment for normal exfoliation of the primary tooth, without harm to the developing enamel or interference with the normal eruption of its permanent successor. Where these outcomes cannot reasonably be achieved over the clinical life of the primary tooth, it is appropriate to extract the affected tooth and consider alternative strategies for occlusal guidance and maintenance of arch integrity (see Chapter 14).

Immature permanent teeth

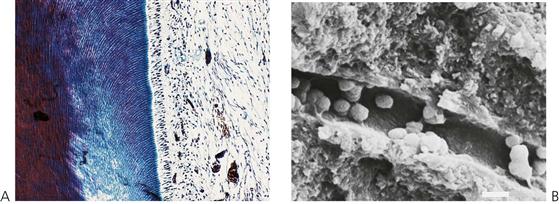

All teeth are immature when they erupt. In addition to the important phase of post-eruptive enamel maturation, the roots of newly erupted permanent teeth will take up to 3 years before their growth is completed. During this period, the roots are short, the root apices are wide open, the dentine is relatively thin and the dentine tubules are relatively wide, increasing the permeability of dentine to bacteria. The open apex is associated with excellent pulpal vascularity and the potential for a favourable healing response.

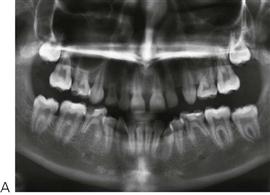

Therapeutic efforts are directed towards preserving the vitality of the pulpo-dentinal complex to facilitate normal root development and maturation (Figure 7.1). If pulp necrosis occurs prior to root maturation, while the affected tooth can still be preserved using non-vital endodontic strategies, it will be compromised with regard to strength, root length and apical development. It is important to consider whether the tooth itself is actually restorable in the long term. Retention of a compromised immature permanent tooth with a poor long-term prognosis may still be beneficial for arch integrity and normal alveolar development during the period of dentofacial growth (see Chapter 14).

Evidence for current practice

The current evidence base for pulp therapy in the primary dentition is poor with a demonstrated paucity of prospective randomized controlled trials. The single biggest issue surrounding pulp therapy in the primary dentition is the lack of correlation between clinical symptoms and pulpal status. Hence, at present, there is no single recognized technique for pulp treatment in primary teeth, and a range of different protocols and medicaments are suggested for different combinations of symptoms and clinical findings.

The information in this chapter is based on established clinical practice, retrospective descriptive studies, clinical experience and expert opinion. In general, it is appropriate to use the least invasive intervention that is predictably associated with a healthy, adaptive healing response in the affected primary or permanent tooth. Obviously, effective primary prevention and early intervention will obviate the need for many of the procedures and techniques described later in this chapter.

Clinical assessment and general considerations

Diagnosis of pulpal status

Effective pulpal therapy requires the correct assessment and interpretation of clinical signs and symptoms, leading to an accurate diagnosis of the pulpal condition. Ineffective or inappropriate pulp therapy is associated with both acute and chronic clinical signs and symptoms. Unfortunately, there are no objective or definitive tests to determine the health of the pulpo-dentinal complex in the primary or immature permanent tooth. Clinical signs and symptoms are poorly correlated with actual pulp histology.

Acute signs and symptoms include:

• Periapical or intra-radicular abscess.

• Facial cellulitis, including spread of infection into the tissue planes around the airway (Ludwig’s angina, see Chapter 10).

Chronic signs and symptoms include:

• Inflammatory follicular cyst (see Chapter 10).

• Failure of exfoliation of primary teeth.

• Ectopic permanent teeth (Figure 7.2).

Figure 7.2 (A) Large multisurface glass ionomer restorations are inadequate to properly restore primary molars. Persistent coronal microleakage leads to pulp necrosis. (B) Panoramic radiograph showing the results of coronal microleakage and the formation of a large inflammatory follicular cyst associated with the second premolar.

Pulp sensibility tests

Standard techniques of pulp sensibility testing are of limited value in children. These techniques rely on patient feedback in response to thermal and electrical stimulation. In the primary dentition, it is likely that children will not have achieved the cognitive development necessary to respond reliably to a potentially painful stimulus and response challenge. In the immature permanent tooth, raised response thresholds to electrical stimuli are observed. These decrease to normal levels with root maturation and apical closure.

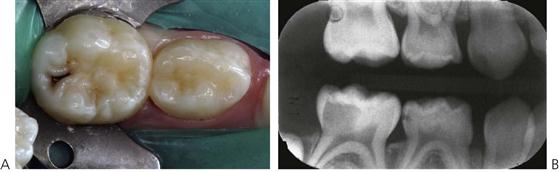

Pain (Figure 7.3)

Young patients frequently have difficulty communicating their experience of pain. It is often not until their pain is severe and prolonged that parents might become aware of and seek treatment for their child. Symptoms of severe, prolonged, spontaneous or nocturnal pain suggest irreversible pulpitis or a dental abscess (Figure 7.3B). A history of repeated need for analgesics is also suggestive of pulp necrosis. Dental pain will frequently resolve once a sinus tract establishes drainage, and thus relieves pressure. In these cases, the underlying pathology is still present and must be resolved, despite the lack of obvious discomfort. Chronic infection in the primary dentition can cause disturbances to enamel formation in the permanent dentition (Turner tooth, see Chapter 11) and malocclusion (Fig 7.2B) even in the absence of clinical symptoms or pain.

Figure 7.3 (A) Much of the pain that children experience may be caused by food impacting into a cavity. Even without radiographs, it is important to recognize that the pulp will always be involved when the carious lesion is of this size. (B) Buccal swelling not only indicates pulpal necrosis and pus formation but also the loss of bone and perforation of the cortical plate. It may also be difficult to initially determine which tooth is responsible for the swelling; in this case, both teeth should be removed.

Other clinical signs

Careful clinical examination of teeth can reveal useful diagnostic information.

• Coronal discoloration is suggestive of pulp necrosis.

• Clinical mobility is associated with loss of bone from infection or imminent exfoliation.

• Marginal ridge fracture in a primary tooth is suggestive of carious pulpal involvement in contact point caries (Figure 7.4A).

Figure 7.4 (A) Loss of marginal ridge of first primary molar suggests carious pulpal involvement. (B) Undermined triangular ridge or cusp suggests carious pulpal involvement.

• Fracture of the occlusal triangular ridges or carious undermining of the cusps in pit and fissure caries also suggests carious involvement (Figure 7.4B).

Unfortunately, the external appearance of the carious lesion can in some cases, be misleading (Figure 7.5). Persistent symptoms occurring soon after placement of a restoration indicate pulpal pathology. Lack of coronal seal will inevitably lead to pulpal pathology. Radiographic examination is essential to supplement clinical findings and enhance diagnostic accuracy.

Radiographs

Longitudinal radiographs showing normal dentine deposition within the pulp chamber and the roots suggests pulpal health. Irregular pulp calcification or pulpal obliteration suggests pulpal dystrophy, while failure of physiological pulp regression or arrested root development suggests pulpal necrosis. In a single radiographic examination, individual teeth can be compared with their antimere to identify asymmetry.

Clinical signs or symptoms suggesting carious involvement of the pulp require radiographic investigation. Radiographs will show the extent of the carious lesion, the position and proximity of pulp horns, the presence and position of the permanent successor, the status of the roots and of their surrounding bone. Radiographic examination should be considered essential before undertaking endodontic procedures. The presence of caries in the furcation, internal or external root resorption including physiological root resorption, and periapical or furcation bone lesions, are all contraindications to endodontic treatment in the primary dentition.

Primary teeth with these radiographic signs should be extracted.

Swelling

Alveolar swelling, particularly involving the vestibular reflection, facial swelling, coronal discoloration, and the presence of a sinus, are indicators of pulp necrosis and abscess formation (see Figure 7.3B).

Mobility

Inappropriate tooth mobility, tenderness to palpation or a sensation of occlusal interference also suggests abscess formation.

Antibiotic usage to control acute infection (see Odontogenic infection, Chapter 10) may temporarily resolve some or all of these clinical signs, but will not resolve the underlying pathology. A primary tooth that cannot be saved requires extraction despite potential future orthodontic complications.

Factors in treatment planning

Medical history

A thorough medical assessment is essential prior to the commencement of any dental treatment. Medical issues may limit or change treatment options in a number of ways. As pulp therapy necessarily relies on the adaptive healing response after treatment, so patients with a significantly compromised immune system are considered poor candidates for endodontic therapy.

Contraindications

• Congenital cardiac disease (see Appendix E). Patients who are considered to be at risk of bacterial endocarditis should be free of oral infection and any primary tooth with clinical signs of infection should be extracted. There is no evidence to suggest that a primary tooth with a large restoration is more or less likely to become infected if it has undergone endodontic treatment according to established guidelines.

• Immunosuppressed patients and those with poor healing potential (see Immunodeficiency, Chapter 12).

Generally, children with well-managed diabetes present no particular problem in relation to healing potential. The use of long-term corticosteroids for the management of asthma, or asthma, should not affect the decision to retain primary teeth. However, children who are severely immunosuppressed, such as oncology patients, must be treated more aggressively (e.g. extractions).

Indications

• Bleeding disorders and coagulopathies (see Chapter 12). Current management protocols for patients with a bleeding diathesis (such as haemophilia) may use regular, often home-based, factor replacement. Where patients have access to such medical treatment, the decision to extract or retain a pulpally involved primary tooth should not be determined by the bleeding diathesis, but should be based on the same criteria used for any other patient. Consultation with the child’s haematologist is essential.

• Hypodontia (i.e. ectodermal dysplasia, Figure 7.6A; see also Chapter 11). In cases of congenital absence of teeth, the decision to extract or retain individual teeth will be influenced by the overall orthodontic strategy. In some cases, there is a requirement to extract primary teeth early to encourage occlusal drift and space closure. In these cases, timing of extractions can be critical, necessitating an interim restoration of the affected primary tooth. In other cases, it is necessary to maintain a primary tooth without a successor. In the absence of acute symptoms, a formal orthodontic evaluation should be considered.

Figure 7.6 (A) Panoramic radiograph of a child with congenital absence of six premolars. While three of the second primary molars are carious, it is important to retain these teeth. (B) It is important to consider the implications of space management when deciding on the most appropriate options in managing a cariously exposed primary molar. In this case, the tooth ‘74’ is pulpally involved but restoration with a stainless steel crown has been made more difficult due to mesial migration of the second primary molar into the distal carious lesion.

Behavioural factors

Effective endodontic treatment requires a high level of patient compliance. If a child is unable to cooperate with pre-treatment diagnostic procedures including radiographs, they are unlikely to cope with complex endodontic and associated restorative procedures. Where cooperation cannot be obtained or is fragile, it is reasonable to consider the elective use of general anaesthesia, or even elective extraction of the affected tooth rather than complex endodontic and restorative procedures.

Endodontics requires effective pain control. Even with usually effective doses of local anaesthetic, a child may experience breakthrough pain. This is particularly so on entry to the pulp chamber. The sedative effects of inhalation sedation used in conjunction with local analgesia can facilitate patient comfort and compliance. The use of the rubber dam to isolate the tooth undergoing treatment, and to protect the patient from instruments and medicaments is essential.

Dental factors

Endodontic management should be considered within the overall context of occlusal development, with due consideration to occlusal guidance and space maintenance (Figure 7.6B; see also Space maintenance, Chapter 14). Under normal circumstances, the service life of a primary incisor is 5–8 years, and a primary cuspid or molar is 8–10 years. The early loss of a primary tooth may lead to localized space loss, delayed eruption and ectopic eruption of the permanent successor. Elective extraction may be considered within 3 years of anticipated exfoliation, because accelerated eruption of the permanent successor can be expected.

Long-term success in endodontic therapy requires an effective coronal seal to prevent micro-leakage and the ingress of oral bacteria to the root canals. If the carious tooth is not restorable, it should be extracted. Pulpotomy and pulpectomy procedures require significant access cavity preparations, which have the potential to weaken the axial walls of the treated tooth. In general, full coverage restoration with a preformed metal crown or a composite resin crown is recommended.

Pulp capping

Indirect pulp capping

Sealing off the advancing carious lesion from the oral environment produces a bacteriostatic response within the body of the lesion, and promotes pulpal healing with the formation of reactionary dentine. This is the basis for indirect pulp capping in both the primary and permanent dentition and is also known as caries control. Indirect pulp capping is also the basis for the atraumatic restorative technique (see Minimal intervention, Chapter 6).

It is uncertain whether the carious lesion in dentine will become sterile and remineralize, or if it merely becomes quiescent with the potential to reactivate if there is leakage around the final restoration, hence there is debate over the necessity of re-entering the tooth to remove the residual caries once there is clinical and radiographic evidence of pulpal healing. Because of the known service life of the primary tooth, there is no indication for re-entering the primary tooth to remove residual caries when the clinical response is favourable.

Ozone and silver fluoride have both been proposed as adjunctive antimicrobial agents in conjunction with indirect pulp capping. At present, there is a lack of evidence to support their superiority over sealing the lesion with standard restorative materials. Ozone may also promote remineralization by oxidization of the lactate-propionate buffering system (pH = 4) within the body of the carious lesion to bicarbonate and water. The depth of residual caries can be no greater than 2 mm when ozone is applied, as ozone will not penetrate more than 2 mm into carious dentine.

Large carious lesions and associated cavity preparations alter the mechanical properties of the treated tooth, reducing the rigidity of the cavity walls in normal function, increasing the potential risk of microleakage. As indirect pulp capping relies on sealing off the residual caries from the oral environment, the residual tooth structure should be carefully evaluated, areas of unsupported enamel removed and weakened cavity walls, which are likely to flex in function (increasing microleakage), should be protected with full coverage. This is of particular importance with approximal lesions where the buccal and lingual walls can be extensively undermined.

Indirect pulp capping in lower first primary molars always requires a preformed metal crown. Severely broken down first permanent molars can be effectively stabilized with preformed metal crowns to allow time for maturation of the pulp and dentine prior to definitive restoration. With growth, there is pulpal regression giving increased dentine thickness for crown preparation, and improved thickness of the radicular dentine giving better root strength. At the completion of dental growth, the restorative options for these teeth can be re-evaluated.

Direct pulp capping

Primary teeth

Small pulp exposures can be broadly classified as mechanical (iatrogenic) or carious. Direct pulp capping of carious pulp exposures in primary teeth has a poor prognosis, with failure occurring as a result of internal root resorption. The size of the pulp exposure does not affect prognosis. A pulpotomy should be undertaken in such cases. Uncontaminated mechanical pulp exposures are thought to have a more favourable response to direct pulp capping using hard-setting calcium hydroxide cements. There is inadequate evidence to support the use of other materials currently used, including antibiotic/corticosteroid (Ledermix®), dentine-bonding resins, mineral trioxide aggregate (MTA) as direct pulp capping agents in the primary dentition. Because of the difficulties in determining the pulp status and the vastly superior prognosis of pulpotomy, direct pulp capping cannot be recommended in the primary dentition.

Immature permanent teeth

Direct pulp capping of pinpoint pulp exposures, either mechanical or carious, has a favourable prognosis in the immature permanent tooth. The use of calcium hydroxide and hard-setting calcium hydroxide cements, has been widely reported, however, there is limited evidence to support the use of other materials.

Pulpotomy in primary teeth

Pulpotomy is the most widely used endodontic technique in the primary dentition. The suffix ‘otomy’ means ‘to cut’, so pulpotomy is ‘to cut the pulp’. The aim of pulpotomy in the primary tooth is to amputate the inflamed coronal pulp and preserve the vitality of the radicular pulp, thereby facilitating the normal exfoliation of the primary tooth.

A pulpotomy cannot be done if the pulp is necrotic

The contemporary pulpotomy traces its origins to nineteenth-century techniques for the mummification of painful, inflamed or putrescent pulpal tissue. Over the twentieth century, the pulpotomy technique changed with fewer stages and reduced duration of application and concentration of medicament. Emphasis is now placed on the preservation of healthy radicular pulp rather than mummification.

Caries removal

The recommendation to remove caries from periphery to pulp not only prevents contamination of the pulpotomy site with carious debris but also reduces the risk of inadvertent pulp exposure. Access to the coronal pulp requires complete removal of the roof of the pulp chamber. Amputation of the coronal pulp requires a clean cut at the level of the pulpal floor. Residual tissue tags at the amputation site will create problems with haemostasis. High-speed rotary instrumentation with copious water spray irrigation creates the optimal cut.

Haemostasis

Haemostasis at the pulpotomy site must be obtained before application of the therapeutic agent. This is achieved with continuous irrigation and gentle dabbing with cotton wool pellets and should occur within 5 min. If bleeding cannot be arrested, the pulpal inflammation is considered to have spread to the roots, and is associated with a poor prognosis. This is referred to as the ‘bleeding sign’ or a ‘hyperaemic pulp’. Pulpectomy or extraction should be considered in these cases.

Pulp medicaments

The therapeutic medicament is applied to the pulpotomy site once haemostasis has been obtained. The pulpotomy site is then covered with a therapeutic base (see below). Traditionally, this has been a zinc oxide-eugenol-based cement. However, eugenol in direct contact with pulp tissue causes chronic pulpitis. It is reasonable to substitute a eugenol-free cement as the therapeutic base. When MTA is used as the therapeutic agent, it will also act as the therapeutic base. Finally, a core material should be used to seal the tooth before the final restoration, ideally with a full coverage restoration.

Earlier texts have suggested that teeth, which are to have a preformed metal crown, should also have a routine elective pulpotomy, regardless of whether they have a carious pulp exposure. This position is no longer tenable given the predictable success of indirect pulp capping. However, the reverse is true, in that all teeth that have had a pulpotomy should be restored with a stainless steel crown. The concept of full coverage also applies to anterior teeth where a full coverage restoration should also be used in those incisors on which a pulpotomy has been performed.

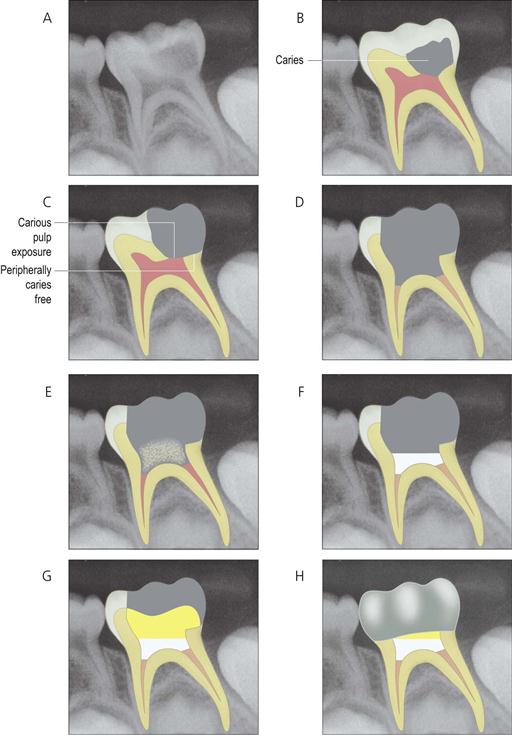

Technique (Figures 7.7, 7.8)

1. Pain control and rubber-dam isolation.

2. Complete removal of caries from peripheral to pulpal.

3. Removal of roof of pulp chamber.

4. Amputation of coronal pulp.

5. Arrest of bleeding at amputation site (see discussion of ‘bleeding sign’ above).

6. Application of therapeutic agent (see Therapeutic agents used for pulpotomy).

7. Place base directly on to pulp amputation site (IRM® or Cavit®).

9. Restore tooth with a preformed metal crown (molars) or a composite resin strip crown for anterior teeth.

Figure 7.7 Method of performing a pulpotomy. (A) Preoperative radiograph shows deep carious lesion. Clinical history revealed intermittent symptoms on eating with no history of spontaneous pain. (B) Carious lesion identified relative to dental anatomy. (C) Cavity preparation showing complete removal of peripheral caries. (D) After the tooth is rendered free of caries, the roof of the pulp chamber is removed completely, and the pulp is amputated to the level of the pulpal floor. Haemostasis must be achieved at this point before proceeding. (E) The therapeutic agent is applied to the pulpotomy site. (F) Base is applied to completely seal the pulpotomy site. (G) The tooth is built up with a core material. (H) The tooth is restored with a preformed metal crown.

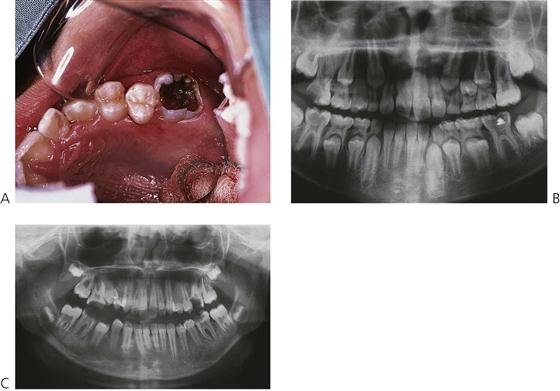

Figure 7.8 Clinical view of a pulpotomy procedure. (A) Bitewing radiographs show deep carious lesion in tooth 74. (B) Access into pulp chamber and amputation of coronal pulp. (C) Ferric sulphate applied to amputated pulp. (D) Appearance of treated pulp following rinsing of ferric sulphate. (E) IRM base completely sealing pulpotomy site. (F) Build-up of crown with glass ionomer cement prior to final restoration. (G) Tooth restored with stainless steel crown.

Therapeutic agents used for pulpotomy in primary teeth

A diverse range of chemicals have been used as pulpotomy agents. As most of these have not been subject to rigorous clinical trials, their use has been based on expert opinion and retrospective studies. In their review for the Cochrane Collaboration, Nadin and colleagues (2003) concluded that based on the available randomized controlled trials (RCTs):

• There is no reliable evidence supporting the superiority of one type of treatment for pulpally involved primary molars.

• No conclusions can be made as to the optimum treatment or techniques for pulpally involved primary molar teeth due to the scarcity of reliable scientific research.

• High quality RCTs, with appropriate unit of randomization and analysis are needed.

The available evidence suggests that formocresol, ferric sulphate, electrocautery and MTA have similar efficacy. Calcium hydroxide appears to have a consistently lower success rate in pulpotomies in primary teeth than these four agents. There are a number of other materials that are of historical significance, or have regional usage, and a number of experimental techniques including bone morphogenic protein and growth factors, which will not be discussed. All current therapeutic agents have toxic effects and must be correctly handled within their therapeutic range. Clinicians should carefully read the Materials Safety Data Sheet for these agents. Cases should be carefully selected within the guidelines recommended.

Mineral trioxide aggregate

MTA is a mixture of tricalcium silicate, bismuth oxide, dicalcium silicate, tricalcium aluminate and calcium sulphate. It is chemically similar to standard cement mix. MTA powder reacts with water to form a paste, which is highly alkaline (pH 13) during the setting phase, then sets to form an inert mass. Clinical success rates for MTA pulpotomy are similar to formocresol and ferric sulphate.

The MTA powder is mixed with water immediately prior to use. The resultant paste is applied to the pulpotomy site using a proprietary carrier or a plastic instrument and is left in situ to set. It is covered with a suitable base material prior to restoration of the tooth. The paste should only be applied after haemostasis has been obtained. Persistent bleeding from the pulpotomy site is an indication for pulpectomy or extraction.

Ferric sulphate

Ferric sulphate is widely used in dentistry as a haemostatic agent (Astringident®). It was initially used in pulpotomy as an aid to haemostasis prior to placement of calcium hydroxide. However, as an independent therapeutic agent, ferric sulphate pulpotomy has a success rate of 74–99%. Ferric sulphate is thought to react with the pulp tissue, forming a superficial protective layer of iron–protein complex. The predominant mode of failure is the result of internal resorption.

Ferric sulphate is burnished onto the pulp stumps (pulpotomy site) using a micro-brush for 15 s, then rinsed off with water and dried. Persistent bleeding after the application of ferric sulphate is an indication for pulpectomy or extraction.

Electrosurgery

Electrosurgery uses radiofrequency energy to produce a controlled superficial tissue burn. It is both haemostatic and antibacterial. Excessive energy or contact time causes a deep tissue burn with necrosis of the radicular pulp and subsequent internal root resorption. Electrosurgical pulpotomy has a success rate of 70–94%.

The electrosurgery unit should be set to coagulate, with a low power setting. A small ball or round-ended tip is applied to the pulpotomy site and briefly activated (Figure 7.9). The site should immediately be flooded with water to remove excess heat. Each pulp stump is treated in turn. If necessary, electrocoagulation can be repeated to control persistent bleeding, until the total cumulative application time is 2 s. Persistent bleeding after this time, is an indication for pulpectomy or extraction. Electrosurgical equipment has the potential to interfere with pacemakers and implanted electronics.

Formocresol

Formocresol has been used in dentistry for over 100 years, and for vital pulpotomy in primary teeth for over 80 years. Its efficacy has been extensively studied, with clinical success rates ranging from 70% to 100%, making it the standard against which newer techniques are compared. The formaldehyde component of formocresol is strongly bactericidal and reversibly inhibits many enzymes in the inflammatory process.

Originally, the aim of using formocresol was to completely mummify (fix) all residual pulpal tissue and necrotic material within the root canal. Current techniques, however, aim to create a very superficial layer of fixation, while preserving the vitality of the deeper radicular pulp.

Formocresol is applied to the pulpotomy site on a cotton wool pledget. Any excess material should be blotted off the pledget prior to application. Traditionally, a 5-min application time has been recommended; however, contact times of only a few seconds are probably equally effective. It is prudent to limit both dose and contact time. Formocresol should only be applied to the pulpotomy site after haemostasis has been obtained. It should never be applied to bleeding tissue.

In 2004, the International Agency for Research on Cancer (IARC) concluded that chronic exposure to high levels of formaldehyde causes nasopharyngeal cancer in humans. In assessing the potential risks of using formocresol clinically, however, it is important to consider the pharmacokinetics of formaldehyde. Formaldehyde is an important intermediate in normal cellular metabolism. It serves as a building block for the synthesis of purines, pyrimidines, many amino acids and lipids, and is a key molecule in one-carbon metabolism. Endogenous formaldehyde is present at low levels in body fluids, with a concentration of 2–3 mg/L in human blood. Application of formocresol results in systemic absorption of formaldehyde, however the absorbed formaldehyde is rapidly metabolized to formate and carbon dioxide with a half-life of 1–2 min. The use of formocresol in dentistry falls within the current permitted exposure limits, and short-term exposure limits for formaldehyde. Formaldehyde does not bioaccumulate.

While much has been written recently concerning the potential toxicity of formocresol, it should be noted also, that exposure to MTA dust and crystalline silica can cause respiratory irritation, ocular damage and skin irritation. The IARC has determined that silica is a known human carcinogen. Similarly, ferric sulphate has been classified as a hazardous, corrosive liquid (Worksafe Australia) and decomposes to form sulphuric acid, that can cause superficial tissue burns if it is not confined to the pulpotomy site. Patients have also suffered earth leakage burns from incorrectly grounded dispersive plates used in electrosurgical equipment.

Clinicians need to be aware of the risks in using any medicament or equipment, use each according to the manufacturers’ directions and be familiar with relevant Material Safety Data Sheets.

Pulpotomy in the immature permanent tooth

The aim of pulpotomy in the immature permanent tooth is to amputate the inflamed coronal pulp and preserve the vitality of the remaining pulp to promote apexogenesis (see Chapter 8). Apexogenesis involves the continued normal development of the radicular pulp below the pulpotomy site, resulting in normal root length, thickness of radicular dentine and apical closure. Apexogenesis optimizes root anatomy and strength. The main risk of apexogenesis is the potential for dystrophic pulp calcification in the event that subsequent pulpectomy is required. The biomechanical properties of the root are more favourable after apexogenesis than after apexification, but apexification is the only option once pulp necrosis has occurred in the immature permanent tooth. An alternative to apexification is the use of haematogenous stem cells to induce calcification of the root canal space.

Unlike the primary dentition in which the pulpotomy is always at the level of the pulpal floor, a small carious exposure of the pulp horn of a permanent tooth can be managed by a superficial pulpotomy of only 1–2 mm. This is based on Cvek’s pulpotomy. Where there is a large exposure, or multiple exposure sites, a deep pulpotomy is required to the opening of the root canals, or the level of the CEJ in an anterior tooth. The exposure site is continuously irrigated until haemostasis occurs, prior to application of the therapeutic medicament. The therapeutic medicament can be calcium hydroxide powder or paste or MTA. Antibiotic/corticosteroid (Ledermix®) paste has also been used.

Technique

1. Pain control and rubber-dam isolation.

2. Complete removal of caries.

3. Removal of roof of pulp chamber.

4. Amputation of coronal pulp, either superficially or deep to the opening of the root canal.

5. Arrest of bleeding at amputation site.

6. Application of therapeutic medicament (calcium hydroxide or MTA).

7. Place base directly over the therapeutic medicament (IRM® or Cavit®).

Pulpectomy in primary teeth

Pulpectomy is the complete removal of all pulpal tissue from the tooth. Pulpectomy can only be considered for primary teeth that have intact roots. Any evidence of root resorption is an indication for extraction. Severe infections including acute facial cellulitis associated with primary teeth do not respond well to pulpectomy. Extraction is usually recommended in these cases.

Although the root canal morphology of primary incisors is relatively simple, the root canal morphology of multi-rooted primary teeth is more complex than permanent teeth, with fins, ramifications and inter-canal communications. These anatomical factors inhibit complete chemo-mechanical debridement of the root canal space. The anatomical apex may be up to 3 mm from the radiographic apex, and frequently occurs on the lateral surface of the root, making it difficult to determine the true working length. Over-instrumentation of the primary tooth root canal has the potential to damage the underlying permanent tooth. Electronic measurement of the root canal can assist with the location of the anatomical apex of a primary tooth.

Obturation of the root canal space in a primary tooth must not interfere with normal exfoliation of the permanent successor. This requires a resorbable paste root filling. The exception to this would be where it is planned to retain a primary tooth that does not have a permanent successor. Suitable materials for obturation include unreinforced zinc oxide eugenol cement, calcium hydroxide paste and iodoform paste.

Technique

1. Pain control and rubber-dam isolation.

2. Complete removal of caries.

3. Chemo-mechanical cleaning and preparation of the root canal, taking care to force neither instruments nor debris beyond the anatomical apex. Copious irrigation with sodium hypochlorite.

4. Obturation with a resorbable paste (see above).

Pulpectomy in immature permanent teeth (Figure 7.10)

Dental immaturity is defined by the lack of apical closure. Necrotic immature permanent molars have a poor long-term prognosis and, except in exceptional circumstances, these teeth should be removed (see Extraction of first permanent molars, Chapter 14). However, retention of such teeth may be important for alveolar development, behavioural reasons or may facilitate subsequent orthodontic treatment by holding space until the optimal time for extraction.

Figure 7.10 (A,B) The long-term prognosis and the ability to restore a tooth are the overriding factors when assessing whether pulp therapy should be undertaken. In these cases, it is often preferable to extract the first permanent molars and allow the second molars to drift mesially. (C) In this case, the eruption of the second molars does not affect the decision to remove the first molars due to the extensive carious breakdown in addition to the presence of the third molars.

By definition, these teeth have already lost significant amounts of tooth structure due to caries. In addition, endodontic treatment would weaken an already compromised tooth, require apexification over many years (see Chapter 8) and involves significant operative challenges (i.e. isolation, obturation, restoration).

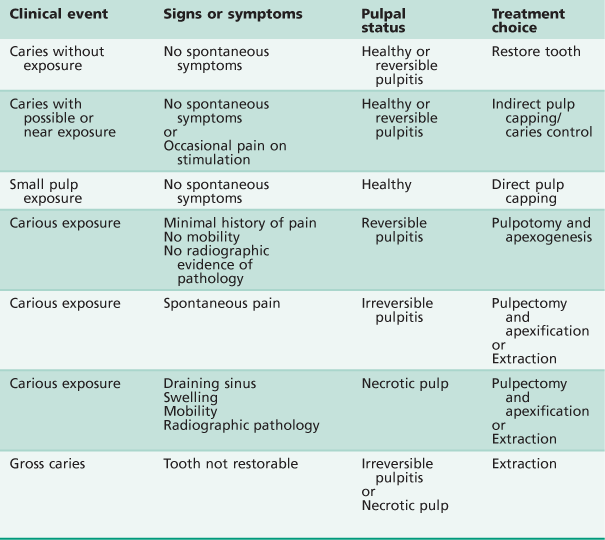

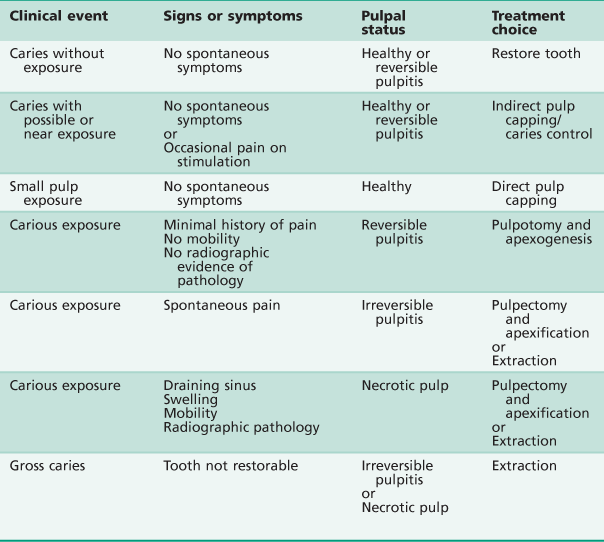

Tables 7.1 and 7.2 summarize the treatment options for primary and immature permanent teeth.

Further reading

1. American Academy on Pediatric Dentistry Clinical Affairs Committee – Pulp Therapy subcommittee. Guideline on pulp therapy for primary and young permanent teeth American Academy on Pediatric Dentistry Council on Clinical Affairs. Pediatric Dentistry. 2009;30(7 Suppl):170–174.

2. Casas MJ, Kenny DJ, Johnston DH, et al. Outcomes of vital primary incisor ferric sulfate pulpotomy and root canal therapy. Journal of the Canadian Dental Association. 2004;70:34–38.

3. Fuks AB. Vital pulp therapy with new materials for primary teeth: new directions and Treatment perspectives. Pediatric Dentistry. 2008;30(3):211–219.

4. Huth KC, Paschos E, Hajek-Al-Khatar N, et al. Effectiveness of 4 pulpotomy techniques–randomized controlled trial. Journal of Dental Research. 2005;84:1144–1148.

5. Huth KC, Hajek-Al-Khatar N, Wolf P, et al. Long-term effectiveness of four pulpotomy techniques: 3-year randomised controlled trial. Clinical Oral Investigations. 2011;16(4):1243–1250.

6. IARC International Agency for Research on Cancer, 2006. Formaldehyde, 2-butoxyethanol and 1-tert-butoxypropan-2-ol. IARC Monographs on the Evaluation of Carcinogenic Risks to Humans, Number 88.

7. Kahl J, Easton J, Johnson G, et al. Formocresol blood levels in children receiving dental treatment under general anesthesia. Pediatric Dentistry. 2008;30(5):393–399.

8. Nadin G, Goel BR, Yeung CA, et al. Pulp treatment for extensive decay in primary teeth. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2003.

9. Rodd HD, Waterhouse PJ, Fuks AB, et al. UK National Clinical Guidelines in Paediatric Dentistry Pulp therapy for primary molars. International Journal of Paediatric Dentistry. 2006;16(Suppl 1):15–23.