Frameworks

A framework is an abstract, logical structure of meaning. It guides the development of the study and enables you to link the findings to the body of knowledge used in nursing. Frameworks are used in both quantitative and qualitative research. In quantitative studies, the framework is a testable theory that may emerge from a conceptual model or may develop inductively from published research or clinical observations. In qualitative research, the initial framework is a philosophy or worldview; a theory consistent with the philosophy may be developed as an outcome of the study.

Every quantitative study has a framework, even when that framework is not explicitly expressed. The framework should be well integrated with the methodology, carefully structured, and clearly presented. When you critically appraise studies to determine if you will apply them in clinical practice or to develop a study, you must be able to identify and evaluate the framework. Your ability to understand the meaning of study findings will depend on your ability to understand the logic within the framework and determines how you will use the findings. Thus, your ability to apply the findings of a study grows when you understand the framework and can relate it to the findings for use in your nursing practice. To help you build the knowledge and skills needed to develop a framework, this chapter explains relevant terms, describes how frameworks are constructed, and discusses the critical analysis of frameworks.

DEFINITION OF TERMS

The first step in understanding theories and frameworks is to familiarize yourself with the terms related to theoretical ideas and their application. These terms and the ways they are used come from the philosophy of science, where the main concern is the nature of scientific knowledge. As nurses have studied philosophies of science, philosophies of nursing science are beginning to emerge.

In the following section, we explain terms such as concept, relational statement, conceptual model, theory, and conceptual map. Within philosophies of science, the term theory is used in a variety of ways that could include both theories and conceptual models (Suppe & Jacox, 1985). In philosophies of nursing science, however, theory tends to be defined narrowly and is different from the term conceptual model.

Concept

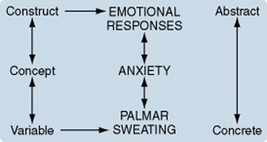

A concept is a term that abstractly describes and names an object, a phenomenon, or an idea, thus providing it with a separate identity or meaning. An example of a concept is the term anxiety. At high levels of abstraction, such as is found in conceptual models, concepts have general meanings and are sometimes referred to as constructs. For example, a construct associated with the concept of anxiety might be “emotional responses.”

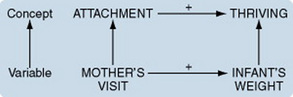

At a more concrete level, terms are referred to as variables and have narrow definitions. A variable is more specific than a concept and implies that the term is defined so that it is measurable. The word variable implies that the numerical values associated with the term vary from one instance to another. A variable related to anxiety might be “palmar sweating,” which the researcher can measure by assigning numerical values to different amounts of sweat on the subject’s palm. The links among constructs, concepts, and variables are illustrated here:

Defining concepts allows us to be consistent in the way we use a term in the discipline, apply it to a theory, and incorporate it in a field of study. A conceptual definition differs from the denotative (or dictionary) definition of a word. A conceptual definition (connotative meaning) is more comprehensive than a denotative definition because it includes associated meanings the word may have. For example, we may connotatively associate the term “fireplace” with images of hospitality and warm comfort, whereas the dictionary definition would be more concrete and narrower. A conceptual definition can be established through concept synthesis, concept derivation, or concept analysis.

Concept Synthesis

In nursing, many phenomena have not yet been identified as discrete entities. However, recognizing, naming, and describing these phenomena are often critical steps to understanding the process and outcomes of nursing practice. The process of describing and naming a previously unrecognized concept is concept synthesis. In the discipline of medicine, Selye (1976) performed concept synthesis to identify and define the concept of stress. Before his work, stress was not known as a phenomenon. Nursing studies often involve previously unrecognized and unnamed phenomena that must be named and carefully defined. Concept synthesis is also important in the development of nursing theory (Walker & Avant, 2004).

Concept Derivation

In some cases, the researcher may obtain conceptual definitions from theories in other disciplines. A conceptual definition obtained in this way will explain a phenomenon important to a non-nursing discipline. Therefore, it will need to be carefully evaluated to determine whether or not it has the same conceptual meaning within nursing. The conceptual definition may need to be modified so that it is meaningful within nursing and consistent with nursing thought (Walker & Avant, 2004). This process, referred to as concept derivation, may require a concept analysis that examines the use of the concept in nursing literature, compares the results with the existing conceptual definition, and, if the two are different, modifies the definition to be consistent with nursing usage.

Concept Analysis

Concept analysis is a strategy that identifies a set of characteristics essential to the connotative meaning of a concept. The procedure will require you to explore the various ways the term is used and to identify a set of characteristics that clarify the range of objects or ideas to which that concept may be applied. You will also use these characteristics to distinguish the concept from similar concepts. Several approaches to concept analysis have been described in the literature, and the authors of these strategies are listed in Table 7-1. In addition, a number of concept analyses have been published in the nursing literature, such as those listed in Table 7-2. Concept analysis is a type of philosophical inquiry, although not all concept analyses follow the philosophical format; an example of a philosophical concept analysis is provided in Chapter 23. Multiple concept analyses are often performed related to a selected concept until there is some degree of consensus within the discipline regarding the conceptual definition. Conceptual definition often leads to methods for measuring the concept and to theories as well.

TABLE 7-1

Publications on How to Conduct a Concept Analysis

| Author | Date | Publication |

| Avant | 2000 | The Wilson method of concept analysis. In Concept Development in Nursing: Foundations, Techniques, and Applications. |

| Broome | 2000 | Integrated literature reviews in the development of concepts. In Concept Development in Nursing: Foundations, Techniques, and Applications. |

| Caron & Bowers | 2000 | Methods and applications of dimensional analysis: A contribution to concept and knowledge development in nursing. In Concept Development in Nursing: Foundations, Techniques, and Applications. |

| Chinn & Kramer | 2007 | Integrated Theory and Knowledge Development in Nursing. |

| Haase, Leidy, Coward, Britt, & Penn | 2000 | Simultaneous concept analysis: A strategy for developing multiple interrelated concepts. In Concept Development in Nursing: Foundations, Techniques, and Applications. |

| Lackey | 2000 | Concept clarification: Using the Norris method in clinical research. Concept Development in Nursing: Foundations, Techniques, and Applications. |

| Maas et al. | 2000 | Concept development of nursing-sensitive outcomes. In Concept Development in Nursing: Foundations, Techniques, and Applications. |

| Morse | 2000 | Exploring pragmatic utility: Concept analysis by critically appraising the literature. In Concept Development in Nursing: Foundations, Techniques, and Applications. |

| Rodgers | 2000 | Concept analysis: An evolutionary view. In Concept Development in Nursing: Foundations, Techniques, and Applications. |

| Sadler | 2000 | A multiphase approach to concept analysis and development. In Concept Development in Nursing: Foundations, Techniques, and Applications. |

| Schwartz-Barcott & Kim | 2000 | An expansion and elaboration of the hybrid model of concept development. In Concept Development in Nursing: Foundations, Techniques, and Applications. |

| Walker & Avant | 2004 | Strategies for Theory Construction in Nursing. |

| Wuest | 2000 | Concept development situated in the critical paradigm. In Concept Development in Nursing: Foundations, Techniques, and Applications. |

Importance of a Conceptual Definition: An Example

Morse, Solberg, Neander, Bottorff, and Johnson (1990) illustrated the importance of a conceptual definition. They analyzed published definitions of the concept of caring in a project funded by the National Center for Nursing Research. In examining previous conceptual definitions of caring, Morse and colleagues found that authors had difficulty separating meanings for caring, care, and nursing care. Caring may be an action, such as “taking care of,” or a concern, such as “caring about.” On the other hand, caring may be viewed from the perspective of the nurse or of the patient. Each of these perspectives alters how caring is conceptually defined. How might a nurse practitioner define caring?

Morse et al. (1990) used content analysis to examine how 35 authors defined the term caring. The analysis included definitions of caring from three nursing theorists: Orem, Watson, and Leininger. The researchers identified five categories of caring: (1) caring as a human trait, (2) caring as a moral imperative, (3) caring as an affect, (4) caring as an interpersonal relationship, and (5) caring as a therapeutic intervention. In addition, they identified two outcomes of caring: (1) the subjective experience of the patient and (2) the physical response of the patient. The following questions emerged from the analysis:

1. “Is caring a constant and uniform characteristic, or may caring be present in various degrees within individuals?” (Morse et al., 1990, p. 9).

2. Is caring an emotional state that can be depleted?

3. “Can caring be nontherapeutic? Can a nurse care too much?” (Morse et al., 1990, p. 10).

4. Can cure occur without caring? Can a nurse engage in safe practice without caring?

5. “What difference does caring make to the patient?” (Morse et al., 1990, p. 11)

These researchers concluded that, at the time of their analysis, a clear conceptual definition of caring did not exist. Their careful analysis has stimulated curiosity within the nursing practice as nurse scholars continue to seek a better understand of the concept of caring as it is used in nursing. Since their study, theoretical work—including additional literature reviews and concept analyses on caring—has increased, not just in the United States but across the world (Table 7-3).

TABLE 7-3

| Year | Author | Title |

| 1990 | Marck | Therapeutic reciprocity: A caring phenomenon |

| 1991 | Roberts & Fitzgerald | Serenity: Caring with perspective |

| 1992 | Eriksson | The alleviation of suffering: The idea of caring |

| 1992 | Eriksson | Different forms of caring communion |

| 1992 | O’Berle & Davies | Support and caring: Exploring the concepts |

| 1992 | Pepin | Family caring and caring in nursing |

| 1993 | Jones & Alexander | The technology of caring: A synthesis of technology and caring for nursing administration |

| 1995 | Buchanan & Ross | A concept analysis of caring |

| 1995 | Fealy | Professional caring: The moral dimension |

| 1995 | Kyle | The concept of caring: A review of the literature |

| 1995 | Scott | Correlates of health promotion in elders |

| 1995 | Smith | An analysis of altruism: A concept of caring |

| 1997 | McCance, McKenna, & Boore | Caring: Dealing with a difficult concept |

| 1997 | Sherwood | Meta-synthesis of qualitative analyses of caring: Defining a therapeutic model of nursing |

| 1997 | Sourial | An analysis of caring |

| 1997 | Wilde | The caring connection in nursing: A concept analysis |

| 1998 | Kelly | Caring and cancer nursing: Framing the reality using selected social science theory |

| 1998 | Wilkes & Wallis | A model of professional nurse caring: Nursing students’ experience |

| 1998 | Wilkinson | What it means to care |

| 1999 | Fredriksson | Modes of relating in a caring conversation: A research synthesis on presence, touch, and listening |

| 1999 | Patistea | Nurses’ perceptions of caring as documented in theory and research |

| 1999 | Rodriquez | Medicine or caring science in ancient Greece [Spanish] |

| 1999 | Smith | Caring and the science of unitary human beings |

| 1999 | Swanson | What is known about caring in nursing science: A literary meta-analysis |

| 1999 | Swanson | Effects of caring, measurement, and time on miscarriage impact and women’s well-being |

| 2000 | Priest | Focus: the use of narrative in the study of caring: A critique |

| 2001 | Kunyk & Olson | Clarification of conceptualizations of empathy |

| 2001 | Mattsson-Lidsle & Lindström | Consolation: A concept analysis [Swedish] |

| 2001 | McCance, McKenna, & Boore | Exploring caring using narrative methodology: An analysis of the approach |

| 2003 | Covington | Caring presence: Delineation of a concept for holistic nursing |

| 2003 | Duffy & Hoskins | The quality-caring model: Blending dual paradigms |

| 2003 | Lewis | Practice applications: Caring as being in nursing: Unique or ubiquitous? |

| 2003 | Lin & Chiou | Concept analysis of caring [Chinese] |

| 2004 | Coffey | Development of the concept of covenant between nurse and patient |

| 2004 | Pang et al. | Towards a Chinese definition of nursing |

| 2004 | Sadler | Descriptions of caring uncovered in student’s baccalaureate program admission essays |

| 2005 | Brilowski & Wendler | An evolutionary concept analysis of caring |

| 2005 | Brunelli | A concept analysis: the grieving process for nurses |

| 2005 | Cowling & Taliaferro | Emergence of a healing-caring perspective: Contemporary conceptual and theoretical directions |

| 2005 | Niu | The philosophy of nursing management: A concept analysis [Chinese] |

| 2006 | Fridh & Bergbom | To watch: A study of the concept [Norwegian] |

| 2006 | Coffey | The nurse-patient relationship in cancer care as a shared covenant: A concept analysis |

| 2006 | Sadler | In response to Brilowski & Wendler (2005) |

| 2006 | Sumner | Concept analysis: The moral construct of caring in nursing as communicative action |

| 2007 | Anderberg, Lepp, M., Berglund, A.L., & Segesten | Preserving dignity in caring for older adults: A concept analysis |

| 2007 | Schantz | Compassion: A concept analysis |

| 2007 | Finfgeld-Connett | Concept comparison of caring and social support |

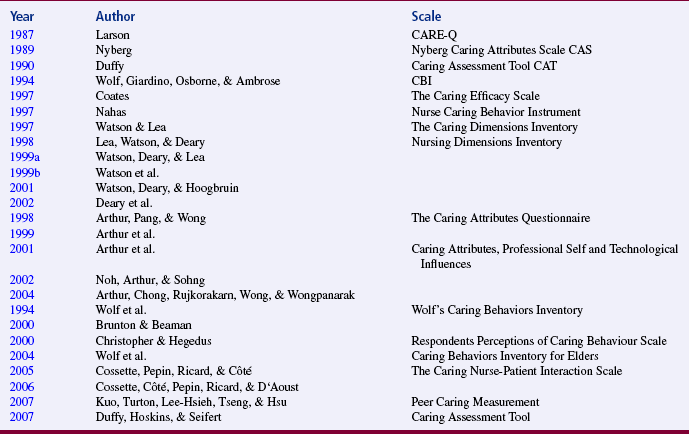

A number of scales have been developed worldwide to measure caring in nursing (Table 7-4), and a number of qualitative studies have been conducted to gain insight on caring (Table 7-5). This work is increasing our understanding of caring in nursing, and enabling us to further implement caring in our practice. How might caring be measured in the work of nurse practitioners? Might qualitative studies increase the insight on caring in the primary care role?

TABLE 7-5

| Year | Author | Title |

| 1995 | Fealy | Professional caring: The moral dimension |

| 1998 | Amendola | Toward a caring curriculum |

| 1998 | Fagerström, Eriksson, & Engberg | The patient’s perceived caring needs as a message of suffering |

| 1999 | Fredriksson | Modes of relating in a caring conversation: A research synthesis on presence, touch and listening |

| 1999 | Joudrey & Gough | Caring and curing revisited: Student nurses’ perceptions of nurses’ and physicians’ ethical stances |

| 1999 | Patistea | Nurses’ perceptions of caring as documented in theory and research |

| 1999 | Rodriquez | Medicine or caring science in ancient Greece [Spanish] |

| 1999 | Smith | Caring and the science of unitary human beings |

| 1999 | Smith-Campbell | A case study on expanding the concept of caring from individuals to communities |

| 2001 | Henderson | Emotional labor and nursing: An under-appreciated aspect of caring work |

| 2001 | Johns | Reflective practice: Revealing the [he]art of caring |

| 2001 | Turkel, Ray & Malinski | Relational complexity: From grounded theory to instrument development and theoretical testing |

| 2002 | Barnhill | The perception of caring in labor and delivery: a phenomenological study |

| 2002 | Schoenhofer | Theoretical concerns: Philosophical underpinnings of an emergent methodology for nursing as caring inquiry |

| 2002 | Yonge & Molzahn | Exceptional nontraditional caring practices of nurses |

| 2003 | Cortis & Kendrick | Nursing ethics, caring and culture |

| 2003 | Fredriksson & Eriksson | The ethics of the caring conversation |

| 2003 | Helin & Lindström | Sacrifice: An ethical dimension of caring that makes suffering meaningful |

| 2003 | McCance | Caring in nursing practice: The development of a conceptual framework |

| 2003 | Rogers | Nursing: An ethic of caring |

| 2003 | Söderlund | Qualitative research approaches of relevance for caring sciences [Swedish] |

| 2004 | Celich & Crossetti | Being with the carer: A dimension of the caring process [Portuguese] |

| 2004 | Clark | Human caring theory: Expansion and explication |

| 2004 | Coffman | Cultural caring in nursing practice: A meta-synthesis of qualitative research |

| 2004 | Cowling & Taliaferro | Emergence of a healing-caring perspective: Contemporary conceptual and theoretical directions |

| 2004 | Forbat | The care and abuse of minoritized ethnic groups: The role of statutory services |

| 2004 | Gramling | Ice chips and hope: The coach’s story of caring art |

| 2004 | Gregg & Magilvy | Values in clinical nursing practice and caring |

| 2004 | Lake | Transformation: Student nurses’ experiences in learning the caring process in nursing |

| 2004 | Lucena & Crossetti | The meaning of caring in the intensive care unit [Portuguese] |

| 2004 | McIntosh | Nurses’ experiences with healing and spirituality |

| 2005 | Biley & Bauer | Bringing the heart back to nursing: Human caring practice and education in Germany and the UK |

| 2005 | Brand | The lived experiences of six women during adjuvant chemotherapy for stage l or ll breast cancer |

| 2005 | Budo & Saupe | Ways of care in rural communities: Culture permeating the nursing care [Portuguese] |

| 2005 | Schumacher | Caring behaviors of preceptors as perceived by new nursing graduate orientees |

| 2005 | Wannapornsiri, Sindhu, Phancharoenworakul, & Gasemgitvatana | Caring process of Thai women with breast cancer receiving chemotherapy |

| 2006 | Coelho | Caring gestures in nursing [Portuguese] |

| 2006 | Delmar | Caring-ethical phronetic research: Epistemological considerations |

| 2006 | Hupcey & Miller | Community dwelling adults’ perception of interpersonal trust vs. trust in health care providers |

| 2006 | Jensen | To see with the heart’s eye [Danish] |

| 2006 | Lindholm, Nieminen, Mäkelä, & Rantanen-Siljamäki | Clinical application research: A Hermeneutical approach to the appropriation of caring science |

| 2006 | Liu, Mok, & Wong | Caring in nursing: Investigating the meaning of caring from the perspective of cancer patients in Beijing, China |

| 2006 | Nåden & Saeteren | Cancer patients’ perception of being or not being confirmed |

| 2006 | Perini et al. | The meaning of caring from the viewpoint of patients with wounds due to peripheral vascular disease [German] |

| 2006 | Sun, Long, Boore, & Tsao | Patients and nurses’ perceptions of ward environmental factors and support systems in the care of suicidal patients |

Relational Statements

A relational statement declares that a relationship of some kind exists between or among two or more concepts (Walker & Avant, 2004). Relational statements form the core of a framework. Skills in expressing statements are essential for constructing an integrated framework that will, in turn, lead to a well-designed study. The statements expressed in your framework will determine (1) your objective, question, or hypothesis; (2) your study’s design; (3) the statistical analyses you will perform; and (4) the type of findings you can expect. Frameworks developed with inadequate expression of statements provide only a broad orientation for the study and do not guide the research process.

Understanding relational statements is essential also for appraising frameworks. Being able to evaluate the links among the hypotheses, the design, and the framework is also an essential part of determining the quality of a study. Judging whether the study was successful depends, in part, on identifying the statements in the framework and tracking their examination by the study.

Characteristics of Relational Statements

Relational statements describe the direction, shape, strength, symmetry, sequencing, probability of occurrence, necessity, and sufficiency of a relationship (Fawcett, 1999; Stember, 1986; Walker & Avant, 2004). One statement may have several of these characteristics; each characteristic is not exclusive of the others. Statements may be expressed in literary form (such as a sentence), in diagrammatic form (such as a conceptual map), or in mathematical form (such as an equation). Statements in nursing tend to be expressed in literary and diagrammatic forms.

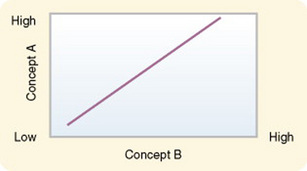

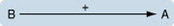

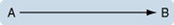

Direction: The direction of a relationship may be positive, negative, or unknown. A positive linear relationship implies that as one concept changes (the value or amount of the concept increases or decreases), the second concept will also change in the same direction. For example, the literary statement “The risk of illness (A) increases as stress (B) increases” expresses a positive relationship. This positive relational statement could also be expressed as “The risk of illness decreases as stress decreases.” This relationship could be diagramed as follows:

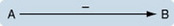

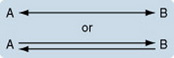

A negative linear relationship implies that as one concept changes, the other concept changes in the opposite direction. For example, the literary statement “As relaxation (A) increases, blood pressure (B) decreases” expresses a negative linear relationship. This relationship could be diagrammed as follows:

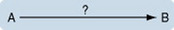

If a relationship is believed to exist but the nature of the relationship is unclear, the following diagram could be used to depict it:

This last type of statement might be appropriate for discussing the relationship between coping and social support. We might say that although there is evidence that a relationship exists between these two concepts, the studies examining that relationship have conflicting findings. For example, some researchers find coping to be positively related to social support—that is, as social support increases, coping increases. However, others may find a negative relationship—that is, as social support increases, coping decreases. Thus, the nature of the relationship between coping and social support is uncertain. It is possible that the conflicting findings may result from differences in how the two concepts have been defined and measured in various studies. But perhaps there is a confounding variable that has not been identified that changes the relationship between coping and social support.

Shape: Most relationships are assumed to be linear, and statistical tests are conducted to look for linear relationships. In a linear relationship, the relationship between the two concepts remains consistent regardless of the values of each of the concepts. For example, if the value of A increases by 1 point each time the value of B increases by 1 point, then the values continue to increase at the same rate whether the value is 2 or 200. The relationship can be illustrated by a straight line, as shown in Figure 7-1.

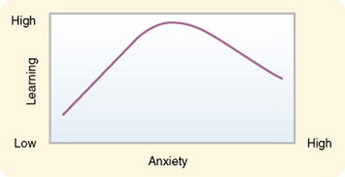

Relationships can also be curvilinear or form some other shape. In a curvilinear relationship, the relationship between two concepts varies according to the relative values of the concepts. The relationship between anxiety and learning is a good example of a curvilinear relationship. Very high or very low levels of anxiety are associated with low levels of learning, whereas moderate levels of anxiety are associated with high levels of learning (Fawcett, 1999). This type of relationship is illustrated by a curved line, as shown in Figure 7-2.

Strength: The strength of a relationship is the amount of variation explained by the relationship. Some of the variation in a concept, but not all, is associated with variation in another concept. In discussing the strength of a relationship, researchers sometimes use the term effect size. The effect size explains how much “effect” variation in one concept has on variation in a second concept.

In some cases, a large portion of the variation can be explained by the relationship; in others, only a moderate or a small portion of the variation can be explained by the relationship. For example, one might examine the strength of the relationship between coping and compliance. A portion of the variance in a measure of compliance is associated with the measure of a person’s coping ability, but the remaining portion of this variation cannot be explained by how well a person copes. Conversely, only a portion of variation in a measure of a person’s ability to cope can be explained by variation in a measure of his or her compliance. The portions of the two concepts that are associated are explained by the strength of the relationship.

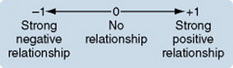

Strength is usually determined by correlational analysis and is expressed mathematically by a correlation coefficient such as the following:

The statistic r is the coefficient obtained by performing the statistical procedure known as Pearson’s product moment correlation. A value of 0 indicates no strength, whereas a +1 or a –1 indicates the greatest strength, as signified in the following diagram:

The + or – does not have an impact on strength. For example, r = –0.35 is as strong as r = +0.35. A weak relationship is usually considered one with an r value of 0.1 to 0.3; a moderate relationship is one with an r value of 0.31 to 0.5; and a strong relationship is one with an r value greater than 0.5. The greater the strength of a relationship, the easier it is to detect relationships between the variables being studied. We explore this idea further in the chapters on sampling, measurement, and data analysis.

Symmetry: Relationships may be symmetrical or asymmetrical. In an asymmetrical relationship, if A occurs (or changes), then B will occur (or change); but there may be no indication that if B occurs (or changes), A will occur (or change) (Fawcett, 1999). A previously cited example showed that when changes in a person’s relaxation level (A) occurred, changes in blood pressure (B) occurred. However, one cannot say that when changes in blood pressure occur, changes in relaxation levels occur. Therefore, the relationship is asymmetrical. An asymmetrical relationship may be diagrammed as follows:

A symmetrical relationship is complex and contains two statements, such as if A occurs (or changes), B will occur (or change); if B occurs (or changes), A will occur (or change) (Fawcett, 1999). An example is the symmetrical relationship between the occurrences of cancer and impaired immunity. As the cancer increases, impaired immunity increases; as impaired immunity increases, cancer increases. A symmetrical relationship may be diagrammed as follows:

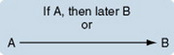

Sequencing: Time is the important factor in explaining the sequential nature of a relationship. If both concepts occur simultaneously, the relationship is concurrent (Fawcett, 1999). The relationship between relaxation (A) and blood pressure (B) may seem to be concurrent. If so, it would be expressed as follows:

If one concept occurs later than the other, the relationship is sequential. If relaxation (A) was thought to occur first, and then blood pressure (B) decreased, the relationship is sequential. This relationship is expressed as follows:

Probability of Occurrence: A relationship can be deterministic or probabilistic depending on the degree of certainty that it will occur. Deterministic (or causal) relationships are statements of what always occurs in a particular situation. A scientific law is one example of a deterministic relationship (Fawcett, 1999). It is expressed as follows:

Another deterministic relationship describes what always happens if no conditions interfere. This is referred to as a tendency statement. A tendency statement might propose that an immobilized patient lying in a typical hospital bed (A) will always develop pressure sores (B) after 6 weeks if there are no interfering conditions. A tendency statement would be expressed in the following form:

A probability statement expresses the probability that something will happen in a given situation (Fawcett, 1999). This relationship is expressed as follows:

Probability statements are tested statistically to determine the extent of probability that B will occur in the event of A. For example, one could state that there is greater than a 50% probability that a patient who has an indwelling catheter for 1 week will experience a urinary bladder infection. This probability could be expressed mathematically as follows:

The p is a symbol for probability. The > is a symbol for “greater than.” This mathematical statement asserts that there is more than a 50% probability that the relationship will occur.

Necessity: In a necessary relationship, one concept must occur for the second concept to occur. For example, one could propose that if sufficient fluids are administered (A), and only if sufficient fluids are administered, then the unconscious patient will remain hydrated (B). This relationship is expressed as follows:

In a substitutable relationship, a similar concept can be substituted for the first concept and the second concept will still occur. For example, a substitutable relationship might propose that if tube feedings are administered (A1), or if hyperalimentation is administered (A2), the unconscious patient can remain nourished (B). This relationship is expressed as follows:

Sufficiency: A sufficient relationship states that when the first concept occurs, the second concept will occur, regardless of the presence or absence of other factors (Fawcett, 1999). A statement could propose that if a patient is immobilized in bed longer than a week, he or she will lose bone calcium, regardless of anything else. This relationship is expressed as follows:

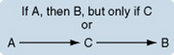

A contingent relationship will occur only if a third concept is present. For example, a statement might claim that if a person experiences a stressor (A), the person will manage the stress (B), but only if she or he uses effective coping strategies (C). The third concept, in this case effective coping strategies, is referred to as an intervening (or mediating) variable. Intervening variables can affect the occurrence, strength, or direction of a relationship. A contingent relationship can be expressed as follows:

Statement Hierarchy

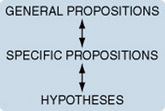

Statements about the same two conceptual ideas can be made at various levels of abstractness. The statements found in conceptual models (general propositions) are at a high level of abstraction. Statements found in theories (specific propositions) are at a moderate level of abstraction. Hypotheses, which are a form of statement, are at a low level of abstraction and are specific. As statements become less abstract, they become narrower in scope (Fawcett, 1999), as shown in the following diagram:

Statements at varying levels of abstraction that express relationships between or among the same conceptual ideas can be arranged in hierarchical form, from general to specific. This arrangement allows you to see (or evaluate) the logical links among the various levels of abstraction. Statement sets link the relationships expressed in the framework with the hypotheses, research questions, or objectives that guide the methodology of the study.

Roy and Roberts (1981) developed statement sets related to Roy’s nursing model that could be used in frameworks for research, as shown in the following excerpts.

Conceptual Models

A conceptual model is a set of highly abstract, related constructs. It broadly explains phenomena of interest, expresses assumptions, and reflects a philosophical stance. A number of conceptual models have been developed in nursing. For example, Roy’s (1984, 1988, 1990) model describes adaptation as the primary phenomenon of interest to nursing. This model identifies the constructs she considers essential to adaptation and how these constructs interact to produce adaptation. Orem (2001) considered self-care to be the phenomenon central to nursing. Her model explains how nurses facilitate the self-care of clients. Rogers (1970, 1980, 1983, 1986, 1988) regarded human beings as the central phenomenon of interest to nursing, and her model is designed to explain the nature of human beings. A conceptual model may use the same or similar constructs as other models but define them in different ways. Thus, Roy, Orem, and Rogers may all use the construct health but define it in different ways.

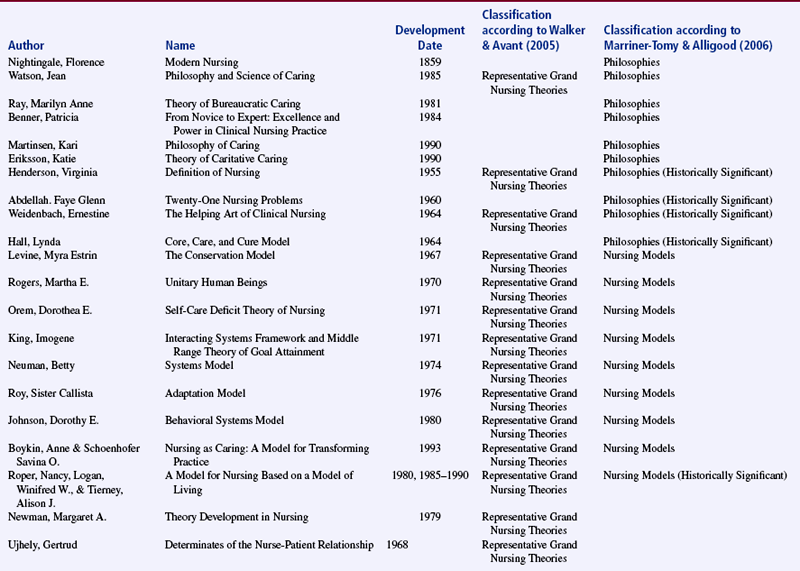

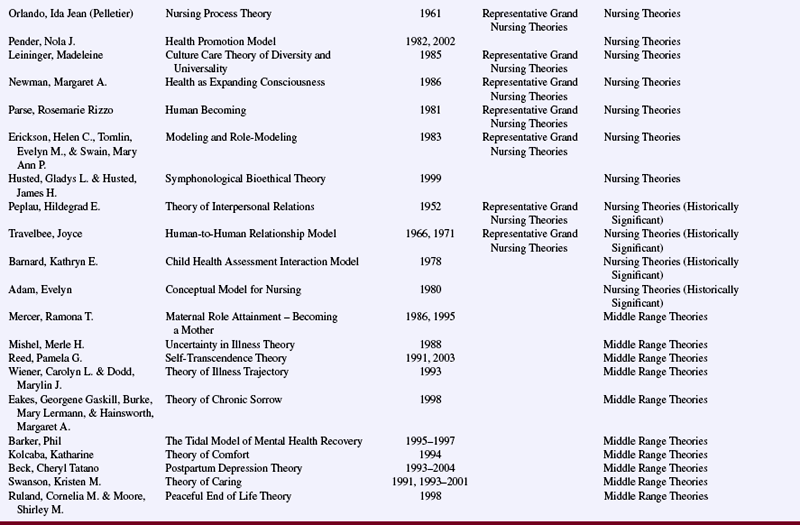

Most disciplines have several conceptual models, each with a distinctive vocabulary. Table 7-6 lists some of the conceptual models or grand theories in nursing. These philosophical and theoretical statements of nursing vary in their level of abstraction and the breadth of phenomena they explain. However, each provides an overall picture, a gestalt of the phenomena they explain. It is not their purpose to provide detail or to be specific. Most are not directly testable through research and thus cannot be used alone as the framework for a study (Fawcett, 1999; Walker & Avant, 2004). However, a framework can include a combination of a more abstract conceptualization of nursing and a theory.

An organized program of research is important for building a body of knowledge related to the phenomena explained by a particular conceptual model. This program of research is referred to as a research tradition. To develop a research tradition for a particular model, a group of scholars must be willing to dedicate time and energy to this endeavor. Middle-range theories compatible with the model must be developed. The research tradition for the conceptual model must be defined. The definition must (1) identify acceptable strategies for developing and testing theory on the basis of the model, (2) define the phenomena to be studied, (3) establish priorities for testing theory statements, (4) develop research methods and measurement techniques, (5) describe data collection strategies, and (6) select acceptable approaches to data analyses (Fawcett, 1999). These research traditions should include the advanced practice roles in nursing and their phenomena.

Researchers conducting studies consistent with a particular tradition may be scattered across the country (or the world), but they often maintain a network of communication about their work. In some cases, they hold annual conferences that focus on the model. These gatherings give researchers the opportunity to share findings, discuss methods, explore theoretical ideas, identify priorities for future research, and maintain network contacts. The organizations of advanced practice nurses should interface with organizations that conduct studies according to a particular tradition; this type of interaction will facilitate studies relevant to advanced nursing practice.

One example of a conceptual nursing model with an emerging research tradition is Orem’s model of self-care. Orem’s (2001) model focuses on the domain of nursing practice and on what nurses actually do. She proposed that individuals generally know how to take care of themselves (self-care). If they are dependent in some way, as are children, the aged, or the handicapped, family members take on this responsibility (dependent care). If individuals are ill or have some health problem (such as diabetes or a colostomy), they or their family members acquire special skills to provide that care (therapeutic self-care). An individual’s capacity to provide self-care is referred to as self-care agency. A self-care deficit occurs when self-care demand exceeds self-care agency (Hartweg & Orem, 1991).

An individual obtains nursing care only when there is a deficit in the self-care or dependent care that the individual and his or her family can provide (self-care deficit). In this case, the nurse or nurses develop a system to provide the needed care. This system involves prescribing, designing, and providing care. The goal of nursing care is to help the individual resume self-care independently or with family assistance. There are three types of nursing systems: wholly compensatory, partly compensatory, and supportive-educative. The system chosen is based on the person’s capacity to perform self-care.

A research tradition related to the testing of propositions of the theory requires a commitment to develop valid and reliable scales to measure the concepts of the theory. Instruments based on Orem’s model are shown in Table 7-7. Orem (2001) has developed three theories related to her model: the theory of self-care deficits, the theory of self-care, and the theory of nursing systems (also referred to as the general theory of nursing). Studies testing statements that have emerged from Orem’s theories appear in the literature (Table 7-8). Research methodologies acceptable for testing Orem’s theories have not been specified in the literature. Orem has suggested that researchers examine the qualitative characteristics of self-care, as well as its presence or absence. She also recommended studying the phases in which individuals (1) investigate the possibility of caring for themselves, (2) make the decision to do so, and (3) begin to engage in self-care behaviors. The focus of self-care in Orem’s work should provide a basis for research by nurse practitioners who, in most cases, must depend on the client’s self-care abilities to implement the instructions provided during primary care. Are there strategies that nurse practitioners could use to increase the self-care capabilities of their clients? Could the effectiveness of a new strategy be tested through research and published to guide other nurse practitioners?

TABLE 7-7

Development of Instruments to Measure Concepts in Orem’s Theories and Use in Studies

| Year | Instrument | Authors |

| 1979 | Exercise of Self-Care Agency Scale (translated to Chinese) | Ailinger & Deer, 1993; Beatty, 1991; Beauchesne, 1989; Brown, 1996; Carroll, 1995; Folden, 1990; Kearney & Fleischer, 1979; Mapanga, 1994; McBride, 1987, 1991 Pressly, 1995; Riesch & Hauck, 1988; St. Onge, 1988; Wang & Laffrey, 2001 |

| 1980 | Denyes Self-Care Agency Instrument–90 | Baker, 1991; Campbell & Soeken, 1999; Canty, 1993; Denyes, 1980; Hurst, 1991; James, 1991; Jesek-Hale, 1994; McBride, 1991; Monsen, 1988; Robinson, 1995; Schott-Baer, 1993; Slusher, 1999 |

| 1982 | Self-Care Agency in Adolescents | Denyes, 1982 |

| 1984 | Self-Care Behavior Log | Dodd, 1984b, 1987 |

| 1984 | Self-Care Behavior Questionnaire | Dodd 1984a, 1984b, 1987 |

| 1985 | Perception of Self-Care Agency | Greenfeld, 1989; Hanson & Bickel, 1985; McBride, 1991; McDermott, 1989; Weaver, 1987 |

| 1987 | ADL Self-Care Scale | Gulick, 1987, 1988, 1989; Mosher & Moore, 1998 |

| 1987 | Appraisal of Self-Care Agency Scale (translated to Chinese, Dutch, Norwegian, and Danish) Turkish, 2004 | Brown, 1996; Evers, Isenberg, Philipsen, Senten, & Brouns, 1993; Fok, Alexander, M.F., Wong, T.K., & McFayden, 2002; Hart, 1993; Hart & Foster, 1998; Isenberg, Evers, G., & Brouns, 1987; Lorensen, Holter, Evers, Isenberg, & van Achterberg, 1993; Nahcivan, 2004; Simmons, 1990; Soderhamn & Cliffordson, 2001; van Achterberg et al., 1991; Vannoy, 1989 |

| 1988 | Nurse Performance Evaluation Tool | Kostopoulos, 1988 |

| 1988 | Self-Care Agency Questionnaire | Bottorff, 1988; Koster, 1995; St. Onge, 1988 |

| 1988 | Self-Care Questionnaire | Riley, 1988 |

| 1989 | Denyes/Fildey Dependent-Care Agency Instrument | Haas, 1990; Moore & Gaffney, 1989; Moore & Mosher, 1997 |

| 1989 | Mother’s Performance of Self-Care Activities for Children | Moore & Gaffney, 1989 |

| 1990 | Denyes Health Status Instrument | Frey & Fox, 1990 |

| 1990 | Functional Status Instrument | Willard, 1990 |

| 1991 | Conditioning Factor Profile | Cull, 1995; McCaleb, 1991 |

| 1991 | Diabetes Self-Care Practices Instrument | Frey & Fox, 1990 |

| 1991 | Self-as-Carer Inventory | Freeman, 1992; Geden & Taylor, 1991; Lukkarinen & Hentinen, 1997; Metcalfe, 1996; White, 2000 |

| 1991 | Self-Care Agency Assessment | Gammon, 1991 |

| 1991 | Cystic Fibrosis Self-Care Practice Instrument | Baker, 1991 |

| 1992 | HIV-Specific Therapeutic Self-Care Demand Inventory | Freeman, 1992 |

| 1992 | HIV-Related Self-Care Behaviors Checklist | Freeman, 1992 |

| 1993 | Children’s Self-Care Performance Questionnaire | Moore, 1993; Moore & Mosher, 1997 |

| 1993 | Hart Prenatal Care Actions Scale | Hart, 1993 |

| 1993 | Task Scale (measures dependent care) | Schott-Baer, 1993 |

| 1995 | Bess’s Measurement of Diabetes Self-Care Practices Scale | Bess, 1995 |

| 1995 | Health Self-Determinism Index for Children | Koster, 1995 |

| 1995 | Maieutic Dimensions of Self-Care Agency | O’Connor, 1995 |

| 1995 | Self-Care of Older Persons Evaluation | Dellasega, 1995 |

| 1995 | Self-Care Practices of Children and Adolescents | Moore, 1995 |

| 1996 | Basic Conditioning Factors Form | Metcalfe, 1996 |

| 1996 | COPD Self-Care Knowledge Questionnaire | Metcalfe, 1996 |

| 1996 | COPD Self-Care Action Scale | Metcalfe, 1996 |

| 1996 | Self-Care Needs Inventory (French) | Page & Ricard, 1996 |

| 1998 | Self-Care Management and Life-Quality Amongst Elderly | Lorensen, 1998 |

| 2001 | Characterization of therapeutic self-care needs of an individual submitted to bone marrow transplantation (Portuguese) | da Silva, 2001 |

| 2001 | Heart Failure Self-Care Inventory | Ahrens, 2001 |

| 2002 | Revised Heart Failure Self-Care Behavior Scale | Artinian, Magnan, Sloan, & Lange, 2002 |

| 2003 | Facts on Osteoporosis Quiz – revised | Ailinger, Lasus, & Braun, 2003 |

| 2003 | Psychiatric Patients Caregiver Burden Scale | Pipatananond & Hanucharurnkul, 2003 |

| 2004 | Self-care scale for dysmenorrhic adolescents | Hsieh, Gau, Mao, & Li, 2004 |

TABLE 7-8

Studies Testing Statements from Orem’s Theories

| Year | Number of Studies | Researchers |

| 1988 | 2 | Alexander, Younger, Cohen, & Crawford; Hartley |

| 1989 | 2 | Frey & Denyes; Hanucharurnkul |

| 1990 | 1 | Weintraub & Hagopian |

| 1991 | 2 | Baker; Hartweg |

| 1993 | 8 | Ailinger & Deer; Baker; Canty; Dodd & Dibble; Folden; Hart; Moore; Schott-Baer |

| 1994 | 4 | Dowd; Jesek-Hale; Mapanga; McCaleb & Edgil |

| 1995 | 8 | Bess; Carroll; Cull; Hart; Koster; Robinson; Schott-Baer, Fisher, & Gregory; Villarruel |

| 1996 | 6 | Aish & Isenberg; Dodd et al.; Gaffney & Moore; Hagopian; Metcalfe; Wang & Fenske |

| 1997 | 4 | Ailinger & Deer; Lukkarinen & Hentinen; Moore & Mosher; Wang |

| 1998 | 2 | Hart & Foster; Mosher & Moore |

| 1999 | 5 | Campbell & Soeken; Lee; Renker; Slusher; Torres, Davim, & da Nobrega |

| 2000 | 3 | Dodd & Miaskowski; Weber; White |

| 2001 | 2 | Cade; Wang & Laffrey |

| 2002 | 3 | Artinian, Magnan, Sloan, & Lange; Fialho, Pagliuca, & Soares; Monteiro, da Nobraga, & de Lima |

| 2003 | 7 | Callaghan; Dashiff; Fok & Daly; Fok & Wong; Phelan, Oliveria, Christos, Dusza, & Halpern; Sousa; Wattanawech, Srimoragot, Kasemkitwattana, & Kimpee |

| 2004 | 3 | Harris; Velsor-Friedrich, Pigott, & Louloudes et al.; Williams & Schreier |

| 2005 | 6 | Callaghan; Hurst, Montgomery, Davis, Killion, & Baker; Sousa & Zauszniewski; Velsor-Friedrich, Pigott, & Srof; Zrinyi & Rimar |

| 2006 | 7 | Ailinger, Moore, Nguyen, & Lasus; Callaghan; Kongsaktrakul et al.; Santos & da Silva; Su, Songwathana, & Naka; Wilson, Brown, & Stephens-Ferris |

| 2007 | 1 | Zrinyi & Zekanyne |

Theory

A theory is more narrow and specific than a conceptual model and is directly testable. A theory consists of an integrated set of defined concepts, existence statements, and relational statements that can be used to describe, explain, predict, or control that phenomenon. Existence statements declare that a given concept exists or that a given relationship occurs. For example, an existence statement might claim that a condition referred to as stress exists and that there is a relationship between stress and health.

Relational statements clarify the relationship that exists between or among concepts. For example, a relational statement might propose that high levels of stress are related to declining levels of health. It is the statements of a theory that are tested through research, not the theory itself. Thus, identifying statements within the theory is critical to the research endeavor and forms the basis of the study’s framework. The types of theory discussed here are scientific, substantive, and tentative.

Middle-Range Theories

Middle-range theories present a partial view of nursing reality. Merton, a sociologist, developed middle-range theories, in 1968. These theories are less abstract and address more specific phenomena than grand theories do. They directly apply to practice and focus on explanation and implementation. Middle-range theories may emerge from grand theories or may develop inductively from research findings. Qualitative studies have been a good source of middle range theory. Some middle-range theories have been developed by combining nursing theories with theories from other disciplines. Recently, some middle-range theories have been developed from clinical practice guidelines.

Middle-range theories are useful in both research and practice. They often help the practitioner to understanding the client’s behavior, enabling more effective interventions. Because of their usefulness in practice, some authors refer to middle-range theories as practice theories. Middle-range theories are used more commonly than grand theories as frameworks for research. As a researcher, it will be important for you to carefully consider what aspects of a particular middle-range theory are appropriate for before using it. Table 7-9 identifies some of the more frequently used middle-range theories.

TABLE 7-9

Middle Range Theories Commonly Used in Nursing

| Author | Reference | Philosophy/Theory |

| Abdellah, Faye Glenn | Abdellah, F. G., Beland, I. I., Martin, A., & Matheney, R. V. (1960). Patient-centered approaches in nursing. New York: Macmillan. | Twenty-One Nursing Problems (1960) |

| Adam, Evelyn | Adam, E. (1980). To be a nurse. Toronto, Canada: W.B. Saunders | Conceptual Model for Nursing (1980) |

| Barker, Phil | Barker, P. (1998). The Tidal Model: An integrative framework for caring within an interpersonal paradigm. Newcastle: University of Newcastle. | The Tidal Model of Mental Health Recovery (1995-1997) |

| Barnard, Kathryn E. | Barnard, K. (1979). Nursing child assessment satellite teaching manual. Seattle: NCAST Publications | Child Health Assessment Interaction Model (1978) |

| Beck, Cheryl Tatano | Beck, C. T. (1993). Teetering on the edge: A substantive theory of postpartum depression. Nursing Research, 42(1): 42–48. | Postpartum Depression Theory (1993) |

| Benner, Patricia | Benner, P. (1984). From novice to expert: Promoting excellence and power in clinical nursing practice. Menlo Park, CA: Addison-Wesley | From Novice to Expert: Excellence and Power in Clinical Nursing Practice (1984) |

| Boykin, Anne & Schoenhofer, Savina O. | Boykin, A., & Schoenhofer, S. (1993) Nursing as caring: A model for transforming practice. New York: National League for Nursing | Nursing as Caring: A Model for Transforming Practice (1993) |

| Eakes, Georgene, Burke, Mary, & Hainsworth, Margaret | Eakes, G. G., Burke, M. L., & Hainsworth, M. A. (1998). Middle-range theory of chronic sorrow. Image: Journal of Nursing Scholarship,30(2): 179–184. | Theory of Chronic Sorrow (1998) |

| Erickson, Helen, Tomlin, Evelyn, & Swain, Mary Ann | Erickson, H. C., Tomlin, E., & Swain, M. A. (1983). Modeling and role-modeling: A theory and paradigm for nursing. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice Hall. | Modeling and Role Modeling (1983) |

| Eriksson, Katie | Eriksson, K. (1990). Systematic and contextual caring science: A study of the basic motive of caring and context. Scandinavian Journal of Caring Sciences, 4(1), 3–5. | Theory of Caritative Caring (1990) |

| Hall, Lynda | Hall, L. E. (1964). Nursing: What is it? The Canadian Nurse, 60, 150-154. | Core, Care, and Cure Model (1964) |

| Henderson, Virginia | Henderson, V. (1966) The nature of nursing. New York: Macmillan. | Definition of Nursing (1955) |

| Husted, Gladys, & Husted, James | Husted, J. H., & Husted, G. L. (1999). Agreement: the origin of ethical action. Critical Care Nursing Quarterly, 22(3): 12-18. | Symphonological Bioethical Theory (1999) |

| Johnson, Dorothy | Johnson, D. E. (1980). The behavioral system model for nursing. In J. P. Riehl & C. Roy (Eds.), Conceptual models for nursing practice (pp. 207–216). New York: Appleton-Century-Crofts. | Behavioral Systems Model (1980) |

| King, Imogene | King, I. M. (1981). A theory for nursing: Systems, concepts, process. New York: John Wiley & Sons. | Interacting Systems Framework and Middle Range Theory of Goal Attainment (1971) |

| Kolcaba, Katharine | Kolcaba, K. Y. (1994). A theory of holistic comfort for nursing. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 19(6): 1178-1184. | Theory of Comfort (1994) |

| Author | Reference | Philosophy/Theory |

| Leininger, Madeleine | Leininger, M. M. (1985). Transcultural care diversity and universality: A theory of nursing. Nursing and Health Care, 6(4), 208-212. | Culture Care Theory of Diversity and Universality (1985) |

| Levine, Myra | Levine, M. E. (1967). The four conservation principles of nursing. Nursing Forum, 6(1): 45-59. | The Conservation Model (1967) |

| Martinsen, Kari | Martinsen, K. (1990). Moral practice and documentation in practical nursing. In T. K. Jensen (Ed.), Foundational problems in nursing ethics, theories of science, leadership and society [Norwegian]. Philosophia, Aarhus. | Philosophy of Caring (1990) |

| Mercer, Ramona | Mercer, R. (1986). First-time motherhood: Experiences from teens to forties. New York: Springer. Mercer, R. (1995). Becoming a mother: Research on maternal identity from Rubin to the present. New York: Springer. | Maternal Role Attainment—Becoming a Mother (1986, 1995) |

| Mishel, Merle | Mishel, M. (1988). The theory of uncertainty in illness. Image, 20(4), 225-232. | Uncertainty in Illness Theory (1988) |

| Neuman, Betty | Neuman, B. (1974). The Betty Neuman Health-Care Systems Model: A total person approach to patient problems. In J. P. Riehl & C. Roy (Eds.), Conceptual models for nursing practice (pp. 99–114). New York: Appleton-Century-Crofts. | Systems Model (1974) |

| Newman, Margaret | Newman, M. A. (1979). Theory Development in Nursing, Philadelphia: F.A. Davis. (see particularly Chapter 6) | Theory Development in Nursing (1979) |

| Newman, Margaret | Newman, M. A. (1986). Health as expanding consciousness. St. Louis: C.V. Mosby. | Health as Expanding Consciousness (1986) |

| Nightingale, Florence | Nightingale, F. (1957). Notes on nursing. Philadelphia: J.B. Lippincott. (Original publication in 1859) | Modern Nursing (1859) |

| Orem, Dorothea | Orem, D. E. (1971). Nursing: Concepts of practice.New York: McGraw-Hill | Self-Care Deficit Theory of Nursing (1971) |

| Orlando, Ida Jean (Pelletier) | Orlando, I. J. (1961). The dynamic nurse-patient relationship: Function, process and principles. New York: G.P. Putnam. | Nursing Process Theory (1961) |

| Parse, Rosemarie | Parse, R. R. (1981). Man-living-health: A theory of nursing. New York: Wiley. | Human Becoming (1981) |

| Pender, Nola | Pender, N. J. (1982). Health promotion in nursing practice. New York: Appleton-Century-Crofts. Most recent edition, 2005 | Health Promotion Model (1982; 2005) |

| Peplau, Hildegard | Peplau, H. E. (1952). Interpersonal relations in nursing. New York: G.P. Putnam. | Theory of Interpersonal Relations (1952) |

| Ray, Marilyn | Ray, M. (1981). A philosophical analysis of caring within nursing. In M. Leininger (Ed.): Caring: An essential human need (pp. 25–36). Thorofare, NJ: Charles B. Slack. | Theory of Bureaucratic Caring (1981) |

| Reed, Pamela | Reed, P. G. (1991). Toward a nursing theory of self-transcendence: Deductive reformulation using developmental theories. Advances in Nursing Science 13(4), 64-77. | Self-Transcendence Theory (1991; 2003) |

| Rogers, Martha | Rogers, M. E. (1970). An introduction to the theoretical basis of nursing. Philadelphia: F.A. Davis. | Unitary Human Beings (1970) |

| Roper, Nancy, Logan, Winifred, & Tierney, Alison | Roper, N., Logan, W., & Tierney, A. (1980, 1985, 1990, 1996). Elements of Nursing. Edinburgh: Churchill Livingstone. Roper, N, Logan, W., & Tierney, A. (1996) The Roper-Logan-Tierney Model: a model in nursing practice. The Roper-Logan-Tierney Model: a model in nursing practice. In P.H. Walker (Ed.), Blueprint for use of nursing models: education, research, practice, and administration. National League for Nursing, pp. 289–314. | A Model for Nursing Based on a Model of Living (1980, 1985, 1990) |

| Roy, Sister Callista | Roy, C. (1976). Introduction to nursing: An adaptation model. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall. | Adaptation Model (1976) |

| Ruland, Cornelia, & Moore, Shirley | Ruland, C. M., & Moore, S. M. (1998). Theory construction based on standards of care: a proposed theory of the peaceful end of life. Nursing Outlook, 46(4): 169–175. | Peaceful End of Life Theory (1998) |

| Swanson, Kristen | Swanson, K. M. (1991). Empirical development of a middle range theory of caring. Nursing Research, 40(3): 161–166. | Theory of Caring (1991) |

| Travelbee, Joyce | Travelbee, J. (1966). Interpersonal aspects of nursing. Philadelphia: F.A. Davis. | Human-to-Human Relationship Model (1966, 1971) |

| Ujhely, Gertrud | Ujhely, G. (1968).Determinants of the nurse-patient relationship. New York: Springer. | Determinants of the Nurse-Patient Relationship (1968) |

| Watson, Jean | Watson, J. (1985). Nursing: Human science and human care. New York: Appleton-Century-Crofts. | Philosophy and Science of Caring (1985) |

| Wiedenbach, Ernestine | Weidenbach, E. (1964). Clinical nursing: A helping art. New York: Springer. | The Helping Art of Clinical Nursing (1964) |

| Wiener, Carolyn, & Dodd, Marylin | Wiener, C. L., & Dodd, M. J. (1993). Coping amid uncertainty: An illness trajectory perspective. Scholarly Inquiry for Nursing Practice, 7(1): 17-31. | Theory of Illness Trajectory (1993) |

Developed by Helen Hough, Nursing Librarian, University of Texas at Arlington.

Scientific Theory

The term scientific theory is restricted to a theory that has valid and reliable methods of measuring each concept and whose relational statements have been tested through research and demonstrated to be valid. Scientific theories have empirical generalizations, statements that have been repeatedly tested and have not been disproved. There are no scientific theories within nursing. Scientific theories from other disciplines are commonly used within the nursing practice. For example, most physiological theories are scientific in nature.

Substantive Theory

Substantive theory is useful for explaining important phenomena within the discipline. The knowledge you gain from a substantive theory may be valuable in practice settings. An example of a substantive theory is the theory of reasoned action (Ajzen & Fishbein, 1980; Fishbein & Ajzen, 1975), which proposes that a person’s expectation that a particular behavior will lead to a given outcome increases his or her intention to perform the behavior. Research has shown that intention predicts behavior. Blue (1995) has reviewed studies that examine the capacity of this theory to predict a person’s willingness to participate in exercise programs.

Substantive theories do not have the validity of a scientific theory. Some of the statements may have been tested and verified, but others have not. In some cases, the statements in the theory may not have been clearly identified by the theorist or by those using the theory.

Tentative Theory

A tentative theory is newly proposed, has had minimal critical appraisal, and has undergone little testing. Tentative theories propose an integrated set of relationships among concepts that have not been satisfactorily addressed in a substantive theory. Because tentative theories are newly emerging and untested, they tend to be less well developed than substantive theories. Many tentative theories have short lives, but others may eventually be more extensively developed and validated through multiple studies.

Tentative theories may be developed from clinical insights, from elements of existing theories not previously related, as outcomes of qualitative studies, or from conceptual models. One type of tentative theory of great importance in nursing today is intervention theories. These middle-range theories seek to explain the dynamics of a patient problem and exactly how a specific nursing intervention is expected to change patient outcomes. Currently, these new theories are tentative, but some will likely become substantive in the future. Intervention theories are discussed in detail in Chapter 13.

Tentative theories developed in nursing often contain concepts and relational statements derived from sociological, psychosocial, psychological, and physiological theories. In some cases, the framework may require that the nurse researcher merge concepts using theory from other sciences with concepts from nursing science theories. Tentative theories in nursing often emerge from questions related to identified nursing problems or from the clinical insight that a relationship exists between or among elements important to desired outcomes. These situations tend to be concrete and require that the researcher express these concrete ideas in more abstract language. This issue is particularly difficult for the beginning researcher. The neophyte researcher’s awareness of theoretical ideas related to the situation may be limited, or the researcher may perceive the situation in such concrete terms that even though the researcher knows the theories, he or she fails to link them to the situation.

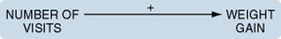

For example, one nurse, a novice researcher who worked in a newborn intensive care unit, was convinced from her clinical experiences that a mother’s frequent visits to the hospital were related to her infant’s weight gain. The nurse’s ideas could be diagrammed as follows:

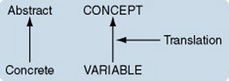

She wanted to study this relationship but was having difficulty expressing her ideas as a framework. Number of visits and weight gain are concrete ideas. From the perspective of research, these ideas are variables. However, to develop a framework, the researcher must express the variables in a more abstract and general way as concepts. This novice researcher lacked the knowledge and skills needed to accomplish this task. She was “stuck” at a concrete level of viewing her problem.

Many students recognize that they are concrete thinkers and believe that they are incapable of moving beyond that limited way of thinking. However, the capacity for abstract thinking is not an innate ability; it is a learned skill. Acquiring it simply requires that one invest the energy to obtain the knowledge and practice the skills.

Converting a concretely expressed term to a higher level of abstractness—from a variable to a concept—is a form of translation. Because the translation in this case is from a lower level of abstractness to a higher level (as shown in the following diagram), we can apply inductive reasoning:

However, the researcher must know of equivalent terms at both the concrete and abstract levels in order to perform the translation. Conducting a literature search can be useful in identifying equivalent abstract terms. The search may be difficult if the novice researcher is blind to the theoretical ideas presented in the literature and picks up only the concrete ideas.

Sometimes, probing questions can help a researcher to move from concrete to more abstract thinking. For example, one could ask, “Why is it important that the mother visit?” “What happens when the mother visits?” Answering these questions may help the researcher to label what happens when the mother visits; existing theories have named this process bonding or attachment. The following diagram could be used to describe this process:

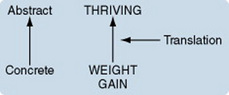

One can then ask, “What happens when the baby gains weight?” “Why is this important?” “How is it different from the baby who gains weight more slowly or fails to gain weight?” One name for this phenomenon is growth; another is thriving. There might be other ways to express the phenomenon. The following diagram could be used to describe this process:

At this point, the novice nurse researcher is ready to search the literature more thoroughly. Theories related to bonding, attachment, growth, and thriving can be examined. The novice researcher may find literature that proposes a positive relationship between attachment and thriving. This relationship could be expressed as follows:

When the aforementioned ideas are linked, we have the beginning of a tentative theory. The diagram—really the beginning of a conceptual map—has the following appearance:

However, the ideas for a framework and a tentative theory are still incomplete. What other factors are important in influencing the relationship between mother’s visits and infant’s weight gain, between attachment and thriving? Again, the researcher can consult the literature. Researchers in this field have examined elements relevant to this question. What concepts did they include? What relationships did they find? Are their findings consistent with the emerging framework? Clinically, what other elements seem to be associated with this phenomenon? Do the newly found concepts need to be included in the framework? While pondering these questions, the researcher can obtain conceptual definitions for attachment and thriving and statements expressing the relationship between the two concepts from existing theories, from synthesis of the literature, or from qualitative data analysis.

As the framework expressing a tentative theory takes shape, it is time to consider moving to an even higher level of abstraction, that of conceptual models. Is there a possible fit between a conceptual model in nursing and the tentative theory expressed in the developing framework? Can the study concepts be translated to the even more abstract constructs of a conceptual model? Are the study statements linked in any way with the broad statements of a conceptual model? If a conceptual nursing model is included in the framework, the links between the conceptual model and the tentative theory must be made clear.

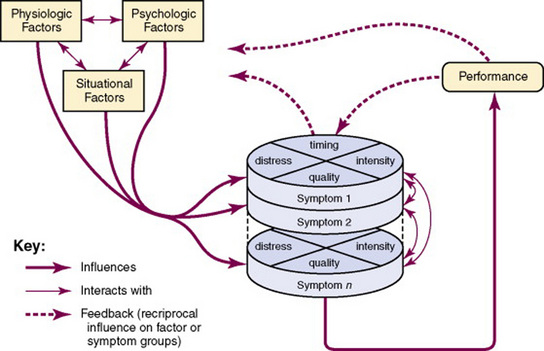

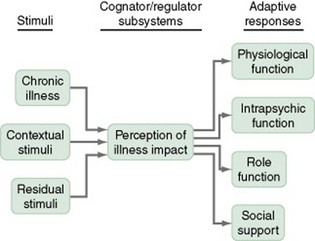

Conceptual Maps

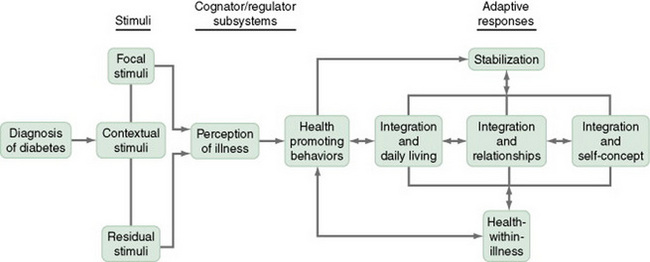

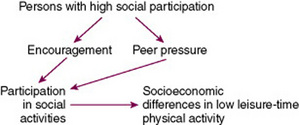

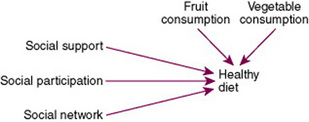

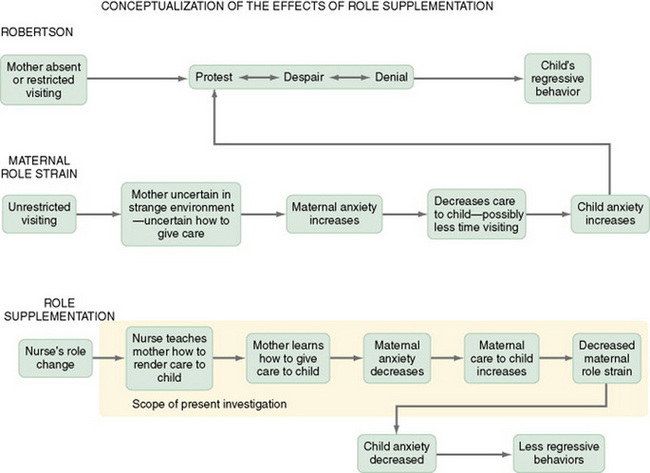

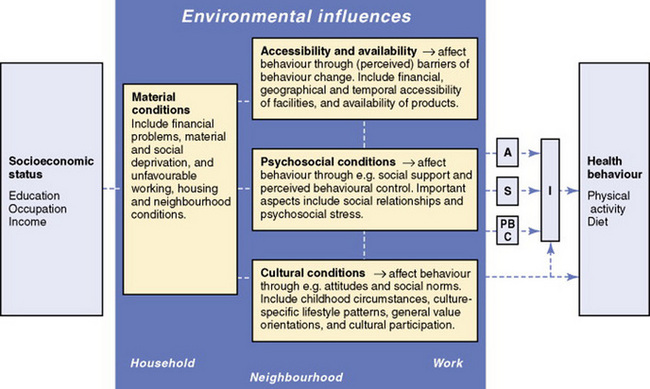

One strategy for expressing a framework is a conceptual map that diagrams the interrelationships of the concepts and statements (Artinian, 1982; Fawcett, 1999; Moody, 1989; Newman, 1979, 1999; Silva, 1981). Figures 7-3 through 7-7 are examples of conceptual maps. A conceptual map summarizes and integrates what we know about a phenomenon more succinctly and clearly than a literary explanation and allows us to grasp the gestalt of a phenomenon. A conceptual map should be supported by references from the literature.

Figure 7-3 Conceptual map outlining scope of present study: conceptualization of the effects of role supplementation.

Figure 7-4 Framework of environmental determinants contributing to the explanation of socioeconomic inequalities in health behaviors. The gray panel incorporates four boxes of environmental determinants. The terms household, neighborhood, and work are examples of the different settings in which these determinants may influence health behaviors. The abbreviations in the right-hand side boxes represent the following constructs: A = attitude; S = social influences, like social support, subjective norms, and modeling; PBC = perceived behavioral control; I = intention. These constructs are derived from the theory of planned behavior (see Ajzen [1991] for more information).

A conceptual map explains which concepts contribute to or partially cause an outcome. Conditions, both direct and indirect, that may produce the outcome are specified. A conceptual map illustrates the process in which factors must cumulatively interact over time in some sequence to have a causal effect. Conceptual maps vary in complexity and accuracy, depending on the available body of knowledge related to the phenomenon. Mapping can also identify gaps in the logic of the theory being used as a framework and reveals inconsistencies, incompleteness, and errors.

Conceptual maps are useful beyond the study for which they were developed. A conceptual map may suggest hypotheses that can be tested in future studies. In addition, through map development, the researcher may gain insight about different situations in which the same process may be occurring. Publication of the map may stimulate the interest of other researchers, who may then use it in their own studies. Thus, a well-developed conceptual map may help to build a body of knowledge related to a particular theory. In addition to conceptual maps included as the framework for a study, more maps are being published that are outcomes of extensive reviews of the literature expressed as tentative theories.

THE STEPS FOR CONSTRUCTING A STUDY FRAMEWORK

Developing a framework is one of the most important steps in the research process but, perhaps, also one of the most difficult. Examples of frameworks from the literature are helpful but not sufficient as a guide to framework development. The brief but impressive presentation of a framework in a published study belies the careful, thoughtful work required to arrive at that point. Yet, as a neophyte researcher you will need to learn how to perform that thoughtful work.

As the body of knowledge related to a phenomenon grows, it becomes easier for researchers to develop a framework to express that knowledge. Therefore, frameworks for quasi-experimental and experimental studies, which should have a background of descriptive and correlational studies and perhaps some substantive theory, should be more easily and fully developed than those for descriptive studies. Descriptive studies and qualitative studies often examine multiple factors to explore a phenomenon not previously well studied. Previous theoretical work related to the phenomenon may be tentative or nonexistent. Therefore, the framework may be less comprehensive. In qualitative studies, in which the framework development is an outcome of the study, even identifying concepts may not be clear at the beginning of the study, and statements will be synthesized from the data. The basis for developing qualitative studies is more philosophical than theoretical.

To illustrate the development of a framework, we will use a middle-range theory by Kamphuis, van Lenthe, Giskes, Brug, and Mackenback (2007) that explains socioeconomic inequalities in health behavior using constructs from the theory of planned behavior (Ajzen, 1991). As you read through the extracts from this study, however, keep in mind that the nicely turned phrases in a framework require much time, effort, thought, and reflection. They do not easily and miraculously appear in their present form. You are examining the finished framework and will not be able to see the process of thinking or the work involved as ideas develop.

The following steps introduce the reasoning used to develop a framework. The steps of the process are (1) selecting and defining concepts, (2) developing statements relating the concepts, (3) expressing the statements in hierarchical fashion, and (4) developing a conceptual map that expresses the framework. The steps are not usually performed in order. In reality, there is a flow of thought from one step to another, back and forth, as ideas are developed and refined.

Selecting and Defining Concepts

Concepts are selected for a framework on the basis of their relevance to the phenomenon you are studying. Thus, the problem statement, which describes the phenomenon, is a rich source of concepts for the framework. If you begin from a concrete clinical perspective, the ideas may be first identified as variables and then translated to concepts. Every major variable included in the study should reflect a concept included in the framework. You may modify the framework as you develop the rest of the study. As you gain additional insight into the phenomenon through a thorough search of theoretical, research, and clinical publications, you may identify additional relevant concepts or propose new relationships. While incorporating these new elements into the framework, consider their implications for the study design.

The framework presented here was developed by researchers from the public health field, not nursing, but it is imminently relevant for nursing research. As Kamphuis and colleagues indicated:

Poorer people experience worse health (Mackenbach et al., 2003; Van Herton, 2002) with higher rates of mortality and morbidity from cardiovascular diseases, obesity, type 2 diabetes and cancers (Choiniere et al., 2000; Kaplffan & Lynch, 1997; Van Lenthe & Mackenback, 2002). Fruit and vegetable consumption and physical activity play a protective role in the onset of these chronic diseases (Ness & Powles, 1977; US DHHS [U.S. Department of Health and Human Services], 1996; Van Duyn & Pivonka, 2000; Wannamethee et al., 2000). Low socioeconomic groups consume less fruits and vegetables(Smith & Brunner, 1997; James et al., 1997)and do less physical activity (Droomers et al., 1998; US DHHS, 1996) than people from higher socioeconomic backgrounds, which is considered one of the explanations for socioeconomic inequalities in health. (p. 493)

Their framework “specifies the pathways between socioeconomic status (SES), environmental factors, personal level factors (constructs from the Theory of Planned Behaviour: see Ajzen, 1991) and health behaviours” (p. 494).

Each concept included in a framework must be defined conceptually. When available and appropriate, use conceptual definitions from existing theoretical works, with definitions quoted and sources cited. If theories that define the concept are not available, you will need to develop the definition. Conceptual definitions may be available in the literature in the absence of theories that use the concept. For an example of the extraction of conceptual definitions from the literature, see Chapter 6 in Understanding Nursing Research (Burns & Grove, 2007).

One source of conceptual definitions is published concept analyses. Previous studies using the concept may also provide a conceptual definition. Another source of a conceptual definition is literature associated with instrument development related to the concept. Although the instrument itself is an operational definition of the concept, the author will often provide a conceptual definition on which the instrument development was based. The general literature can sometimes provide a conceptual definition. Although it may not have been as carefully thought out as the definitions in a theory or a concept analysis, this conceptual definition may reflect the only definition available in the discipline.

When acceptable conceptual definitions are not available, perform concept synthesis or concept analysis to develop the definition. You must present various definitions of the concept from the literature to validate the conceptual definition you selected for the study.

Kamphuis et al. (2007) provided the conceptual definitions in the following excerpts.

Developing Relational Statements

The next step in framework development is to link all of the concepts through relational statements. Whenever possible, obtain relational statements from theoretical works and the sources cited. If such statements are unavailable, propose the relationships. Provide evidence from the literature for the validity of each relational statement whenever available. This support must include a discussion of previous quantitative or qualitative studies (or both) that have examined the proposed relationship and published observations from the clinical practice perspective.

As you develop the framework, you may have to extract statements that are embedded in the literary text of an existing theory, published research, or clinical literature. When you first begin extracting statements, the task can be overwhelming because every sentence in the text seems to be a relational statement. A little practice makes the task easier. The steps in the process of extracting statements are as follows:

1. Select a portion of a theory that discusses the relationships between or among two or three concepts.

2. Write down a single sentence from the theory that seems to be a relational statement.

3. Express it by using the statement diagrams presented earlier in the chapter.

4. Move to the next statement, and express it with diagrams.

5. Continue until all of the statements related to the selected concepts have been expressed using statement diagrams.

6. Examine the links among the diagrammatic statements you have developed. The logic of what the theorist is saying will gradually become clearer.

This process is illustrated in greater detail in Chapter 6 of Understanding Nursing Research (Burns & Grove, 2007).

If statements relating the concepts of interest are not available in the literature, statement synthesis is necessary. Develop statements that propose specific relationships among the concepts you are studying. You may gain the knowledge for your statement synthesis through clinical observation and integrative literature review (Walker & Avant, 2004).

In descriptive studies, theoretical statements related to the phenomenon may be sparse. In this case, developing a framework requires more synthesis and has a higher level of uncertainty. You may note in the statement that a relationship between A and B is proposed but the type of relationship is unknown. Follow this statement with a research question based on this relationship rather than a hypothesis. For example, ask, “What is the nature of the relationship between A and B?” An objective might be to examine the nature of the relationship between A and B.

Kamphuis et al. (2007) offered the relational statements shown in the following excerpts, each of which is followed by a diagram of the relationship.

Developing Hierarchical Statement Sets

A hierarchical statement set is composed of a specific proposition and a hypothesis or research question. If a conceptual model is included in the framework, the statement set may also contain a general proposition. The proposition is listed first, with the hypothesis or research question immediately following. In some cases, more than one hypothesis may be related to a particular proposition. However, there must be a proposition for each hypothesis stated. This statement set indicates the link between the framework and the methodology.

Constructing a Conceptual Map

Conceptual maps are initiated early in the development of the framework, but refining the map will probably be one of your last steps. Before you can complete the map, the following information must be available:

1. A clear problem and purpose statement.

2. Concepts of interest, including conceptual definitions.

3. Results of an integrative review of the theoretical and empirical literature.

4. Relational statements linking the concepts, expressed literally and diagrammatically.

5. Identification and analysis of existing theories that address the relationships of interest.

6. Identification of existing conceptual models congruent with the developing framework.

7. Linking of proposed relationships with hypotheses, questions, or objectives (hierarchical statement sets).

Some nursing scholars believe that the map should be limited to those concepts included in the study (Fawcett, 1999). However, Artinian (1982) recommended that the map include all the concepts necessary to explain the phenomenon, plainly delineating that portion of the map to be studied. We agree with Artinian. It is important that the map be a full expression of the phenomenon of concern. This strategy is illustrated by Artinian’s map of the conceptualization of the effects of role supplementation, presented in Figure 7-3. In this map, the scope of the study is enclosed by a yellow box.

Developing your own concept map entails the following steps. First, arrange the concepts on the page in sequence of occurrence (or causal linkage) from left to right, with the concepts reflecting the outcomes located on the far right. Concepts that are elements of a more abstract construct can be placed in a frame or box. Sets of closely interrelated concepts can be linked by enclosing them in a frame or circle. Second, using arrows, link the concepts in a way that is consistent with the statement diagrams you previously developed. For some studies, at some point on the map, the path of relationships may diverge, so that there are then two or more paths of concepts. The paths may converge at a later point. Every concept should be linked to at least one other concept. Third, examine the map for completeness by asking yourself the following questions: