Critical Appraisal of Nursing Studies

The nursing profession continues to strive for evidence-based practice, which includes ap-praising studies critically, synthesizing research findings, and applying sound scientific evidence in practice. Researchers also critically appraise studies in a selected area, develop a systematic review of the current knowledge, and identify areas for future studies. Thus, critically appraising research is essential for evidence-based nursing practice and the conduct of future research. The critical appraisal of research involves a systematic, unbiased, careful examination of all aspects of a study to judge the merits, limitations, meaning, and significance. It is based on previous research experience and knowledge of the topic. To conduct a critical appraisal of research, one must possess a background in analysis and the skills in logical reasoning needed to examine the credibility and integrity of a study. This chapter provides a background for critically appraising studies in nursing and other health care disciplines. The critique of research in the nursing profession has evolved over the years as nurses have increased their analysis skills and expertise. The chapter concludes with a description of the critical analysis processes implemented to examine the quality of both quantitative and qualitative research. These processes include unique skills, guidelines, and standards for evaluating different types of research.

EVOLUTION OF CRITICAL APPRAISAL OF RESEARCH IN NURSING

The process for critical appraisal of research has evolved gradually in nursing because until recently only a few nurses have been prepared to conduct comprehensive, scholarly critiques. During the 1940s and 1950s, presentations of nursing research were followed by critiques of the studies. These critiques often focused on the faults or limitations of the studies and tended to be harsh and traumatic for the researcher (Meleis, 1991). As a consequence of these early unpleasant experiences, nurse researchers began to protect and shelter their nurse scientists from the threat of criticism. Public critiques, written or verbal, were rare in the 1960s and 1970s. Those responding to research presentations focused on the strengths of studies, and the limitations were either not mentioned or minimized. Thus, the impact of the limitations on the meaning, validity, and significance of the study was often lost.

Incomplete critiques or the absence of critiques may have served a purpose as nurses gained basic research skills. However, the nursing discipline has moved past this point, and a comprehensive critical appraisal of research is essential to strengthen the scientific investigations needed to provide an evidence-based practice (Brown, 1999; Melnyk & Fineout-Overholt, 2005). As a result of advances in the nursing profession during the 1980s and 1990s, many nurses now have the preparation and expertise to conduct critical appraisals. Nursing research textbooks provide detailed information on the critical appraisal process. Skills in critical appraisal are introduced at the baccalaureate level of nursing education and are expanded at the master’s and doctoral levels. Specialty organizations provide workshops on the critical appraisal process to promote the use of scientific evidence in practice.

The critical appraisal of studies is essential for the development and refinement of nursing knowledge. Nurses need these skills to examine the meaning and validity of study findings and to ask searching questions. Was the methodology of a study sound to produce valid findings? Are the findings an accurate reflection of reality? Do they increase our understanding of the nature of phenomena that are important in nursing? Are the findings from the present study consistent with those from previous studies? Can the study be replicated? The answers to these questions require careful examination of the research problem, the theoretical basis of the study, and the study’s methodology. Not only must the mechanics of conducting the study be examined, but the abstract and logical reasoning that the researcher used to plan and implement the study must also be evaluated. If the reasoning process used to develop the study has flaws, there are probably flaws in interpreting the meaning of the findings, decreasing the validity of the study.

All studies have flaws, but if all flawed studies were discarded, there would be no scientific knowledge base for practice (Oberst, 1992). In fact, science itself is flawed. Science does not completely or perfectly describe, explain, predict, or control reality. However, improved understanding and an increased ability to predict and control phenomena depend on recognizing the flaws in studies and in science. New studies can then be planned to minimize the flaws or limitations of earlier studies. Thus, a researcher must critically analyze previous studies to determine their limitations and then interpret the study findings in light of those limitations. The limitations can lead to inaccurate data, inaccurate outcomes of analysis, and decreased ability to generalize the findings. You must decide if a study is too flawed to be used in a systematic review of knowledge in an area. Although we recognize that knowledge is not absolute, we need to have confidence in the research evidence synthesized for practice.

All studies have strengths as well as limitations. Recognition of these strengths is also essential to the generation of sound research evidence for practice. If only weaknesses are identified, nurses might discount the value of studies and refuse to invest time in reading and examining research. The continued work of the researcher also depends on recognizing the study’s strengths. If no study is good enough, why invest time conducting research? Points of strength in a study, added to points of strength from multiple other studies, slowly build solid research evidence for practice.

When are Critical Appraisals of Research Implemented in Nursing?

In general, research is critically appraised to broaden understanding, summarize knowledge for practice, and provide a knowledge base for future studies. In addition, critical appraisals are often conducted after verbal presentations of studies, after a published research report, for an abstract section for a conference, for article selection for publication, and for evaluation of research proposals for implementation or funding. Thus, nursing students, practicing nurses, nurse educators, and nurse researchers are all involved in the critical appraisal of research.

Students’ Critical Appraisal of Studies

In nursing education, conducting a critical appraisal of a study is often seen as a first step in learning the research process. Part of learning the research process is being able to read and comprehend published research reports. However, conducting a critical appraisal of a study is not a basic skill, and the content presented in previous chapters is essential for implementing this process. Nurses usually acquire basic knowledge of the research process and the critical appraisal process early in the course of their nursing education. More advanced analysis skills are often taught at the master’s and doctoral levels. The steps involved in performing a critical appraisal of a study are (1) comprehension, (2) comparison, (3) analysis, (4) evaluation, and (5) conceptual clustering. By critically appraising studies, students expand their analysis skills, strengthen their knowledge base, and increase their use of research evidence in practice.

Critical Appraisal of Research by the Practicing Nurse

Practicing nurses need to critically appraise studies so their practice is based on research evidence and not tradition and trial and error (Melnyk & Fineout-Overholt, 2005). Nursing actions must be updated in response to the current evidence that is generated through research and theory development. Practicing nurses need to design methods for remaining current in their practice areas. Reading research journals or posting current studies at work can increase nurses’ awareness of study findings but is not sufficient for critique to occur. Nurses need to question the quality of the studies and the credibility of the findings and share their concerns with other nurses. For example, nurses may form a research journal club in which studies are presented and critically appraised by members of the group (Tibbles & Sanford, 1994). Skills in critical appraisal of research enable the practicing nurse to synthesize the most credible, significant, and appropriate empirical evidence for use in practice (Peat, Mellis, Williams, & Xuan, 2002).

Critical Appraisal of Research by Nurse Educators

Educators critically appraise research to expand their knowledge base and to develop and refine the educational process. The careful analysis of current nursing studies provides a basis for updating curriculum content for use in clinical and classroom settings. Educators act as role models for their students by examining new studies, evaluating the information obtained from research, and indicating what research evidence to use in practice. In addition, educators collaborate in the conduct of studies, which requires a critical appraisal of previous relevant research.

Nurse Researchers’ Critical Appraisal of Studies

Nurse researchers critically appraise previous research to plan and implement their next study. Many researchers focus their studies in one area, and they update their knowledge base by critiquing new studies in this area. The outcomes of these appraisals influence the selection of research problems, the development of methodologies, and the interpretations of findings in future studies. The critical appraisal of previous studies for synthesis in the literature review section in a research proposal or report was described in Chapter 6.

Critical Appraisal of Research Presentations and Publications

Critiques following research presentations can assist researchers in identifying the strengths and weaknesses of their studies and generating ideas for further research. Participants listening to study critiques might gain insight into the conduct of research. Experiencing the critical appraisal process can increase the participants’ ability to evaluate studies and judge the usefulness of the research evidence for practice.

Currently, at least two nursing research journals, Scholarly Inquiry for Nursing Practice: An International Journal and Western Journal of Nursing Research, include commentaries after the research articles. In these journals, other researchers critically appraise the authors’ studies, and the authors have a chance to respond to these comments. Published critiques of research often increase the reader’s understanding of the study and the quality of the study findings. Another, more informal critique of a published study might appear in a letter to the editor. Readers have the opportunity to comment on the strengths and weaknesses of published studies by writing to the journal editor.

Critical Appraisal of Abstracts for Conference Presentations

One of the most difficult types of critical appraisal is examining abstracts. The amount of information available is usually limited because many abstracts are restricted to 100 to 250 words (Pyrczak, 1999). Nevertheless, reviewers must select the best-designed studies with the most significant outcomes for presentation at nursing conferences. This process requires an experienced researcher who needs few cues to determine the quality of a study. Critical appraisal of an abstract usually addresses the following criteria: (1) appropriateness of the study for the program; (2) completeness of the research project; (3) overall quality of the study problem, purpose, framework, methodology, and results; (4) contribution of the study to the nursing knowledge base; (5) contribution of the study to nursing theory; (6) originality of the work (not previously published); (7) implication of the study findings for practice; and (8) clarity, conciseness, and completeness of the abstract (American Psychological Association [APA], 2001; Morse Dellasega, & Doberneck, 1993).

Critical Appraisal of Research Articles for Publication

Nurse researchers who serve as peer reviewers for professional journals evaluate the quality of research papers submitted for publication. The role of these scientists is to ensure that the studies accepted for publication are well designed and contribute to the body of knowledge. Most of these reviews are conducted anonymously so that friendships or reputations do not interfere with the selection process (Tilden, 2002). In most refereed journals (82%), the experts who examine the research report have been selected from an established group of peer reviewers (Swanson, McCloskey, & Bodensteiner, 1991). Their comments or a summary of their comments is sent to the researcher. The editor also uses these comments to make selections for publication. The process for publishing a study was described in Chapter 25.

Critical Appraisal of Research Proposals

Critical appraisals of research proposals are conducted to approve student research projects; to permit data collection in an institution; and to select the best studies for funding by local, state, national, and international organizations and agencies. The process researchers use to seek the approval to conduct a study is presented in Chapter 28. The peer review process in federal funding agencies involves an extremely complex critique. Nurses are involved in this level of research review through the national funding agencies, such as the National Institute of Nursing Research (NINR) and the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ). Kim and Felton (1993) identified some of the criteria used to evaluate the quality of a proposal for possible funding, such as the (1) appropriate use of measurement for the types of questions that the research is designed to answer, (2) appropriate use and interpretation of statistical procedures, (3) evaluation of clinical practice and forecasting of the need for nursing or other appropriate interventions, and (4) construction of models to direct the research and interpret the findings. Rudy and Kerr (2000) described audits being done by the National Institutes of Health (NIH) to determine the best studies to receive federal funding. This article included an example audit worksheet with guidelines and questions that focused on the following steps of the research process: purpose, sampling criteria, subjects to be enrolled during the grant period, consent forms, procedures, instruments’ reliability and validity, data input, and data analysis. This audit worksheet might assist researchers in developing stronger proposals to submit for NIH funding.

CRITICAL APPRAISAL PROCESS FOR QUANTITATIVE STUDIES

The critical appraisal process for quantitative research includes five steps: (1) comprehension, (2) comparison, (3) analysis, (4) evaluation, and (5) conceptual clustering. Conducting a critical appraisal of a study is a complex mental process that is stimulated by raising questions. The level of critique conducted is influenced by the sophistication of the individual appraising the study (Table 26-1). The initial critical appraisal of research by an undergraduate student often involves only the comprehension step of the process, which includes identification of the steps of the research process in a study. Some baccalaureate programs include more in-depth research courses that incorporate the comparison step of critical appraisal, wherein the quality of the research report is examined using expert sources. A critical appraisal of research conducted by a master’s-level student usually involves the steps of comprehension, comparison, analysis, and evaluation. The analysis step involves examining the logical links among the steps of the research process, with evaluation focusing on the overall quality of the study and the credibility and validity of the findings. Conceptual clustering is a complex synthesis of the findings of several studies, and it provides the current, empirical knowledge base for a phenomenon. This critical appraisal step is usually perfected by doctoral students, postdoctoral students, and experienced researchers as they develop systematic reviews of research, meta- analyses, and integrated reviews of research for publication. These summaries of current research evidence are essential to direct practice and conduct future research.

Conducting a critical appraisal of quantitative and qualitative research involves applying some basic guidelines, such as those outlined in Table 26-2. These guidelines stress the importance of examining the expertise of the authors; reviewing the entire study; addressing the study’s strengths, weaknesses, and logical links; and evaluating the contribution of the study to nursing practice. These guidelines are linked to the first four steps of the critical appraisal process: comprehension, comparison, analysis, and evaluation. These steps occur in sequence, vary in depth, and presume accomplishment of the preceding steps. However, an individual with critical appraisal experience frequently performs several steps of this process simultaneously.

TABLE 26-2

Guidelines for Conducting Critical Appraisals of Quantitative and Qualitative Research

1. Read and evaluate the entire study. A research appraisal requires identification and examination of all steps of the research process. (Comprehension)

2. Examine the research, clinical, and educational background of the authors. The authors need a clinical and scientific background that is appropriate for the study conducted. (Comprehension)

3. Examine the organization and presentation of the research report. The title of the research report needs to clearly indicate the focus of the study. The report usually includes an abstract, introduction, methods, results, discussion, and references. The abstract of the study needs to present the purpose of the study clearly and highlight the methodology and major results. The body of the report needs to be complete, concise, clearly presented, and logically organized. The references need to be complete and presented in a consistent format. (Comparison)

4. Identify the strengths and weaknesses of a study. All studies have strengths and weaknesses, and you can use the questions in this chapter to facilitate identification of them. Address the quality of the steps of the research process and the logical links among the steps of the process. (Comparison and analysis)

5. Provide specific examples of the strengths and weaknesses of a study. These examples provide a rationale and documentation for your critique of the study. (Comparison and analysis)

6. Be objective and realistic in identifying a study’s strengths and weaknesses. Try not to be overly critical when identifying a study’s weaknesses or overly flattering when identifying the strengths.

7. Suggest modifications for future studies. Modifications should increase the strengths and decrease the weaknesses in the study.

8. Evaluate the study. Indicate the overall quality of the study and its contribution to nursing knowledge. Discuss the consistency of the findings of this study with those of previous research. Discuss the need for further research and the potential to use the findings in practice. (Evaluation)

This section includes the steps of the critical appraisal process and provides relevant questions for each step. These questions are not comprehensive but have been selected as a means for stimulating the logical reasoning necessary for conducting a study review. Persons experienced in the critical appraisal process formulate additional questions as part of their reasoning processes. We cover the comprehension step separately because those new to critical appraisal start with this step. The comparison and analysis steps are covered together because these steps often occur simultaneously in the mind of the person conducting the critical appraisal. Evaluation and conceptual clustering are covered separately because of the increased expertise needed to perform each step.

Step I: Comprehension

Initial attempts to comprehend research articles are often frustrating because the terminology and stylized manner of the report are unfamiliar. Comprehension is the first step in the critical appraisal process. It involves understanding the terms and concepts in the report, as well as identifying study elements and grasping the nature, significance, and meaning of these elements. The reviewer demonstrates comprehension as she or he identifies each element or step of the study.

Guidelines for Comprehension

The first step involves reviewing the abstract and reading the study from beginning to end. As you read, address the following questions about the presentation of the study (Brown, 1999; Crookes & Davies, 1998): Does the title clearly identify the focus of the study by including the major study variables and the population? Does the title indicate the type of study conducted—descriptive, correlational, quasi-experimental, or experimental quantitative studies; outcomes studies; or intervention research? Was the abstract clear? Was the writing style of the report clear and concise? Were the different parts of the research report plainly identified? Were relevant terms defined? You might underline the terms you do not understand and determine their meaning from the glossary at the end of this book. Read the article a second time and highlight or underline each step of the quantitative research process. An overview of these steps is presented in Chapter 3. To write a critique of a study, you need to identify each step of the research process concisely and respond briefly to the following guidelines and questions:

A Identify the reference of the article using APA format (APA, 2001).

B Describe the qualifications of the authors to conduct the study (such as research expertise, clinical experience, and educational preparation).

C Discuss the clarity of the article title (type of study, variables, and population identified).

D Discuss the quality of the abstract (includes purpose; highlights design, sample, and intervention [if applicable]; and presents key results).

IV Examine the literature review.

A Are relevant previous studies and theories described?

B Are the references current? (Number and percentage of sources in the last 10 years and in the last 5 years?)

D Is a summary provided of the current knowledge (what is known and not known) about the research problem?

V Examine the study framework or theoretical perspective.

A Is the framework explicitly expressed or must the reviewer extract the framework from implicit statements in the introduction or literature review?

B Is the framework based on tentative, substantive, or scientific theory? Provide a rationale for your answer.

C Does the framework identify, define, and describe the relationships among the concepts of interest? Provide examples of this.

D Is a map of the framework provided for clarity? If a map is not presented, develop a map that represents the study’s framework and describe the map.

E Link the study variables to the relevant concepts in the map.

F How is the framework related to nursing’s body of knowledge?

VI List any research objectives, questions, or hypotheses.

VII Identify and define (conceptually and operationally) the study variables or concepts that were identified in the objectives, questions, or hypotheses. If objectives, questions, or hypotheses are not stated, identify and define the variables in the study purpose and the results section of the study. If conceptual definitions are not found, identify possible definitions for each major study variable. Indicate which of the following types of variables were included in the study. A study usually includes independent and dependent variables or research variables but not all three types of variables.

A Independent variables: Identify and define conceptually and operationally.

B Dependent variables: Identify and define conceptually and operationally.

C Research variables or concepts: Identify and define conceptually and operationally.

VIII Identify attribute or demographic variables and other relevant terms.

IX Identify the research design.

A Identify the specific design of the study. Draw a model of the design by using the sample design models presented in Chapter 11.

B Does the study include a treatment or intervention? If so, is the treatment clearly described with a protocol and consistently implemented?

C If the study has more than one group, how were subjects assigned to groups?

D Are extraneous variables identified and controlled? Extraneous variables are usually discussed as a part of quasi- experimental and experimental studies.

E Were pilot study findings used to design this study? If yes, briefly discuss the pilot and the changes made in this study based on the pilot.

X Describe the sample and setting.

A Identify inclusion or exclusion sample criteria.

B Identify the specific type of probability or nonprobability sampling method that was used to obtain the sample. Did the researchers identify the sampling frame for the study?

C Identify the sample size. Discuss the refusal rate or percentage, and include the rationale for refusal if presented in the article. Discuss the power analysis if this process was used to determine sample size.

D Identify the characteristics of the sample.

E Identify the sample mortality or attrition (number and percentage) for the study.

F Discuss the institutional review board approval. Describe the informed consent process used in the study.

G Identify the study setting and indicate if it is appropriate for the study purpose.

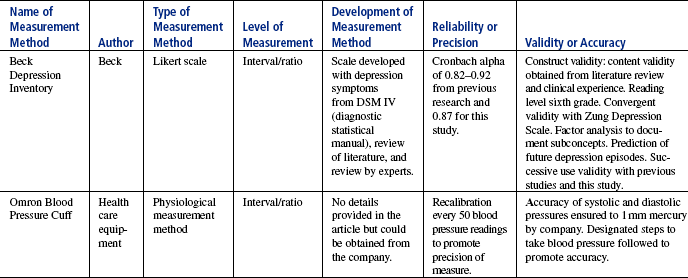

XI Identify and describe each measurement strategy used in the study. The table that follows includes the critical information about two measurement methods, the Beck Likert Scale and the physiological instrument to measure blood pressure. Completing this table will allow you to cover essential measurement content for a study.

A Identify the name of the measurement strategy.

B Identify the author of each measurement strategy.

C Identify the type of each measurement strategy (e.g., Likert scale, visual analogue scale, physiological measure).

D Identify the level of measurement (nominal, ordinal, interval, or ratio) achieved by each measurement method used in the study.

E Discuss how the instrument was developed.

F Describe the validity and reliability of each scale for previous studies and this study. If physiological measurement methods were used, discuss their accuracy and precision.

XII Describe the procedures for data collection.

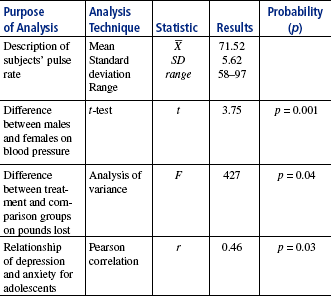

XIII Describe the statistical analyses used.

A List the statistical procedures used to describe the sample.

B Was the level of significance or alpha identified? If so, indicate what it was (0.05, 0.01, or 0.001).

C Complete the following table with the analysis techniques conducted in the study: (1) identify the focus (description, relationships, or differences) for each analysis technique, (2) list the statistical analysis technique performed, (3) list the statistic, (4) provide the specific results, and (5) identify the level of significance or probability achieved by the result.

XIV Describe the researcher’s interpretation of findings.

A Are the findings related back to the study framework? If so, do the findings support the study framework?

B Which findings are consistent with those expected?

C Which findings were not expected?

D Are the findings consistent with previous research findings?

XV What study limitations did the researcher identify?

XVI How did the researcher generalize the findings?

XVII What were the implications of the findings for nursing practice?

XVIII What suggestions for further study were identified?

XIX Is the description of the study sufficiently clear for replication?

Step II: Comparison

The next step, comparison, requires knowledge of what each step of the research process should be like. Then the ideal way to conduct the steps of the research process is compared with the actual study steps. During the comparison step, you examine the extent to which the researcher followed the rules for an ideal study. You also need to gain a sense of how clearly the researcher grasped the study situation and expressed it. The clarity of the researchers’ explanation of study elements demonstrates their skill in using and expressing ideas that require abstract reasoning.

Step III: Analysis

The analysis step involves examining the logical links connecting one study element with another. For example, the problem needs to provide background and direction for the statement of the purpose. In addition, you need to examine the overall flow of logic in the study. The variables identified in the study purpose need to be consistent with the variables identified in the research objectives, questions, or hypotheses. The variables identified in the research objectives, questions, or hypotheses need to be conceptually defined in light of the study framework. The conceptual definitions provide the basis for the development of operational definitions. The study design and analyses need to be appropriate for the investigation of the study purpose, as well as for the specific objectives, questions, or hypotheses (Ryan-Wenger, 1992).

Most of the limitations in a study result from breaks in logical reasoning. For example, biases caused by sampling and design impair the logical flow from design to interpretation of findings. The previous levels of critical appraisal have addressed concrete aspects of the study. During analysis, the process moves to examining abstract dimensions of the study, which requires greater familiarity with the logic behind the research process and increased skill in abstract reasoning.

Guidelines for Comparison and Analysis

To conduct the steps of comparison and analysis, you need to review Unit II of this text on the research process as well as other research textbooks (Burns & Grove, 2007; Houser, 2008; LoBiondo-Wood & Haber, 2005; Melnyk & Fineout-Overholt, 2005; Nieswiadomy, 2008; Peat et al., 2002; Polit & Beck, 2008). After reviewing several sources on the steps of the research process, compare the elements in the study that you are critically appraising with the criteria established for each element in this textbook or in other sources (Step II: Comparison), and then analyze the logical links among the steps of the study by examining how each step provides a basis for and links with the remaining steps of the research process (Step III: Analysis). The following guidelines will assist you in implementing the steps of comparison and analysis for each step of the research process. Questions relevant to analysis are labeled; all other questions direct comparison of the steps of the study with the ideal presented in research texts. The written critique will be a summary of the strengths and weaknesses that you noted in the study.

I Research problem and purpose

A Is the problem sufficiently delimited in scope so it is researchable but not trivial?

B Is the problem significant to nursing and clinical practice?

C Does the problem have a gender bias and address only the health needs of men to the exclusion of women’s health needs (Yam, 1994)?

D Does the purpose narrow and clarify the aim of the study?

E Was this study feasible to conduct in terms of money commitment; the researchers’ expertise; availability of subjects, facilities, and equipment; and ethical considerations?

A Is the literature review organized to demonstrate the progressive development of evidence from previous research? (Analysis)

B Is a theoretical knowledge base developed for the problem and purpose? (Analysis)

C Is a clear, concise summary presented of the current empirical and theoretical knowledge in the area of the study (Stone, 2002)?

D Does the literature review summary identify what is known and not known about the research problem and provide direction for the formation of the research purpose? (Analysis)

A Is the framework presented with clarity? If a model or conceptual map of the framework is present, is it adequate to explain the phenomenon of concern?

B Is the framework linked to the research purpose? If not, would another framework fit more logically with the study? (Analysis)

C Is the framework related to the body of knowledge in nursing and clinical practice? (Analysis)

D If a proposition from a theory is to be tested, is the proposition clearly identified and linked to the study hypotheses? (Analysis and comparison)

IV Research objectives, questions, or hypotheses

A Are the objectives, questions, or hypotheses expressed clearly?

B Are the objectives, questions, or hypotheses logically linked to the research purpose? (Analysis)

C Are hypotheses stated to direct the conduct of quasi-experimental and experimental research (Kerlinger & Lee, 2000)?

D Are the objectives, questions, or hypotheses logically linked to the concepts and relationships (propositions) in the framework? (Analysis)

A Are the variables reflective of the concepts identified in the framework? (Analysis)

B Are the variables clearly defined (conceptually and operationally) and based on previous research or theories? (Analysis and comparison)

C Is the conceptual definition of a variable consistent with the operational definition? (Analysis)

A Is the design used in the study the most appropriate design to obtain the needed data?

B Does the design provide a means to examine all the objectives, questions, or hypotheses? (Analysis)

C Is the treatment clearly described (Brown, 2002)? Is the treatment appropriate for examining the study purpose and hypotheses? Does the study framework explain the links between the treatment (independent variable) and the proposed outcomes (dependent variables) (Sidani & Braden, 1998)? Was a protocol developed to promote consistent implementation of the treatment? Did the researcher monitor implementation of the treatment to ensure consistency (Bowman, Wyman, & Peters, 2002; Santacroce, Maccarelli, & Grey, 2004)? If the treatment was not consistently implemented, what might be the impact on the findings? (Analysis and comparison)

D Did the researcher identify the threats to design validity (statistical conclusion validity, internal validity, construct validity, and external validity) and minimize them as much as possible?

E Is the design logically linked to the sampling method and statistical analyses? (Analysis)

F If more than one group is used, do the groups appear equivalent?

G If a treatment was used, were the subjects randomly assigned to the treatment group or were the treatment and comparison group matched? Were the treatment and comparison group assignments appropriate for the purpose of the study (Bowman et al., 2002)?

VII Sample, population, and setting

A Is the sampling method adequate to produce a representative sample?

B What are the potential biases in the sampling method? Are any subjects excluded from the study because of age, socioeconomic status, or race without a sound rationale? (Larson, 1994)

C Did the sample include an understudied population, such as the young, elderly, or a minority group (Resnick et al., 2003)?

D Were the sampling criteria (inclusion and exclusion) appropriate for the type of study conducted?

E Is the sample size sufficient to avoid a type II error? Was a power analysis conducted to determine sample size? If a power analysis was conducted, were the results of the analysis clearly described and used to determine the final sample size? Was the mortality or attrition rate projected in determining the final sample size?

F Are the rights of human subjects protected?

G Is the setting used in the study typical of clinical settings?

H Was the refusal to participate rate a problem? If so, how might this weakness influence the findings? (Analysis)

I Was sample mortality or attrition a problem? If so, how might this weakness influence the final sample and the study results and findings? (Analysis)

A Do the measurement methods selected for the study adequately measure the study variables? (Analysis)

B Are the measurement methods sufficiently sensitive to detect small differences between subjects? Should additional measurement methods have been used to improve the quality of the study outcomes?

C Do the measurement methods used in the study have adequate validity and reliability? What additional reliability or validity testing is needed to improve the quality of the measurement methods (Bowman et al., 2002; Roberts & Stone, 2004)?

D Respond to the following questions, which are relevant to the measurement approaches used in the study:

(a) Are the instruments clearly described?

(b) Are techniques to complete and score the instruments provided?

(c) Are validity and reliability of the instruments described?

(d) Did the researcher reexamine the validity and reliability of instruments for the present sample?

(e) If the instrument was developed for the study, is the instrument development process described?

(a) Is what is to be observed clearly identified and defined?

(b) Is interrater reliability described?

(c) Are the techniques for recording observations described?

(a) Do the interview questions address concerns expressed in the research problem? (Analysis)

(b) Are the interview questions relevant for the research purpose and objectives, questions, or hypotheses? (Analysis)

(c) Does the design of the questions tend to bias subjects’ responses?

(d) Does the sequence of questions tend to bias subjects’ responses?

(a) Are the physiological measures or instruments clearly described? If appropriate, are the brand names, such as Space Labs or Hewlett-Packard, of the instruments identified?

(b) Are the accuracy, selectivity, precision, sensitivity, and error of the physiological instruments discussed?

(c) Are the physiological measures appropriate for the research purpose and objectives, questions, or hypotheses? (Analysis)

(d) Are the methods for recording data from the physiological measures clearly described? Is the recording of data consistent?

A Is the data collection process clearly described (Bowman et al., 2002)?

B Are the forms used to collect data organized to facilitate computerizing the data?

C Is the training of data collectors clearly described and adequate?

D Is the data collection process conducted in a consistent manner?

E Are the data collection methods ethical?

F Do the data collected address the research objectives, questions, or hypotheses? (Analysis)

G Did any adverse events occur during data collection, and were these appropriately managed (Bowman et al., 2002)?

A Are data analysis procedures appropriate for the type of data collected (Corty, 2007)?

B Are data analysis procedures clearly described? Did the researcher address any problems with missing data and how this problem was managed?

C Do the data analysis techniques address the study purpose and the research objectives, questions, or hypotheses? (Analysis)

D Are the results presented in an understandable way by narrative, tables, or figures, or a combination of methods?

E Are the statistical analyses logically linked to the design? (Analysis)

F Is the sample size sufficient to detect significant differences if they are present? (Analysis)

G Was a power analysis conducted for nonsignificant results? (Analysis)

A Are findings discussed in relation to each objective, question, or hypothesis?

B Are various explanations for significant and nonsignificant findings examined?

C Are the findings clinically significant (LeFort, 1993; Melnyk & Fineout-Overholt, 2005)?

D Are the findings linked to the study framework? (Analysis)

E Are the study findings an accurate reflection of reality and valid for use in clinical practice? (Analysis) (Melnyk & Fineout-Overholt, 2005; Peat et al., 2002)

F Do the conclusions fit the results from the data analyses? Are the conclusions based on statistically significant and clinically significant results? (Analysis)

G Does the study have limitations not identified by the researcher? (Analysis)

H Did the researcher generalize the findings appropriately?

I Were the identified implications for practice appropriate based on the study findings and the findings from previous research? (Analysis)

Step IV: Evaluation

Evaluation involves determining the meaning, significance, and validity of the study by examining the links between the study process, study findings, and previous studies. The steps of the study are evaluated in light of previous studies, such as an evaluation of present hypotheses based on previous hypotheses, present design based on previous designs, and present methods of measuring variables based on previous methods of measurement. The findings of the present study are also examined in light of the findings of previous studies. Evaluation builds on conclusions reached during the first three stages of the critique and provides the basis for conceptual clustering.

Guidelines for Evaluation

You need to reexamine the findings, conclusions, and implications sections of the study and the researchers’ suggestions for further study. Using the following questions as a guide, summarize the strengths and weaknesses of the study:

1. What rival hypotheses can be suggested for the findings?

2. Do you believe the study findings are valid? How much confidence can be placed in the study findings?

3. To what populations can the findings be generalized?

4. What questions emerge from the findings, and does the researcher identify them?

5. What future research can be envisioned?

6. Could the limitations of the study have been corrected?

7. When the findings are examined in light of previous studies, what is now known and not known about the phenomenon under study?

You need to read previous studies conducted in the area of the research being examined and summarize your responses to the following questions:

1. Are the findings of previous studies used to generate the research problem and purpose?

2. Is the design an advancement over previous designs?

3. Do sampling strategies show an improvement over previous studies? Does the sample selection have the potential for adding diversity to samples previously studied (Larson, 1994)?

4. Does the current research build on previous measurement strategies so that measurement is more precise or more reflective of the variables?

5. How do statistical analyses compare with those used in previous studies?

6. Do the findings build on the findings of previous studies?

7. Is current knowledge in this area identified?

8. Does the author indicate the implication of the findings for practice?

The evaluation of a research report should also include a final discussion of the quality of the report. This discussion should include an expert opinion of the study’s contribution to nursing knowledge and the need for additional research in selected areas. You also need to determine if the empirical evidence generated by this study and previous research is ready for use in practice (Whittemore, 2005).

Step V: Conceptual Clustering

The last step of the critique process is conceptual clustering, which involves synthesizing the study findings to determine the current body of knowledge in an area (Pinch, 1995). Until the 1980s, conceptual clustering was seldom addressed in the nursing literature. However, in 1983, the initial volume of the Annual Review of Nursing Research was published to provide conceptual clustering of specific phenomena of interest in the areas of nursing practice, nursing care delivery, nursing education, and the profession of nursing (Werley & Fitzpatrick, 1983). These books continue to be published each year and provide integrated reviews of research on a variety of topics relevant to nursing. Conceptual clustering is also evident in the publication of systematic reviews of research and integrative reviews of research in clinical and research journals and on national websites such as www.guideline.gov (Stone, 2002; Whittemore, 2005)

Guidelines for Conceptual Clustering

Through conceptual clustering, current knowledge in an area of study is carefully analyzed, relationships are examined, and the knowledge is summarized and organized theoretically. Conceptual clustering maximizes the meaning attached to research findings, highlights gaps in knowledge, generates new research questions, and provides empirical evidence for use in practice.

I Process for clustering findings and developing the current knowledge base

A Is the purpose for reviewing the literature clearly identified? Are specific questions articulated to guide the literature review (Stone, 2002; Whittemore, 2005)?

B Are protocols developed to guide the literature review?

C Is a systematic and comprehensive review of the literature conducted (Stone, 2002)?

D Are the criteria for including studies in the review clearly identified and used appropriately (Whittemore, 2005)?

E Are the studies systematically critiqued for quality outcomes?

F Is the process for clustering study findings clearly described? Are the data statistically combined?

G Is the current knowledge base clearly expressed, including what is known and what is not known?

II Theoretical organization of the knowledge base

A Draw a map showing the concepts and relationships found in the studies reviewed in the previous criteria (section I) to detect gaps in understanding relationships. You can also compare this map with current theory in the area of study by asking the following questions:

1. Is the map consistent with current theory?

2. Are there differences in the map that are upheld by well-designed research? If so, modification of existing theory should be considered.

3. Are there concepts and relationships in existing theory that have not been examined in the studies diagrammed in the map? If so, studies should be developed to examine these gaps.

4. Are there conflicting theories within the field of study? Do existing study findings tend to support one of the theories?

5. Are there no existing theories to explain the phenomenon under consideration?

6. Can current research findings be used to begin the development of nursing theory to explain the phenomenon more completely?

III Moving toward evidence-based practice

A Is there sufficient confidence in the research evidence for application to practice? If so, develop a systematic review of the research to promote the use of this empirical evidence in practice.

B What are the benefits and risks of using selected research evidence for patient care?

C When research evidence is used in practice, what are the outcomes for patients, providers, and health care agencies (Brown, 1999; Doran, 2003)?

Meta-analysis is another form of conceptual clustering that goes beyond critique and integration of research findings to conducting statistical analysis on the outcomes of similar studies (Beck, 1999; Whittemore, 2005). A meta-analysis statistically pools the results from previous studies into a single result or outcome that provides the strongest evidence about a relationship between two variables or concepts or the efficacy of a treatment or intervention (LaValley, 1997). Conducting a quality meta-analysis requires a great deal of rigor in implementing the following steps: (1) developing a protocol to direct conduct of the meta-analysis, (2) locating relevant studies, (3) selecting studies for analysis that meet the criteria in the protocol, (4) conducting statistical analyses, (5) assessing the meta-analysis results, and (6) discussing the relevance of the findings to nursing knowledge and practice (Whittemore, 2005). Chapter 27 discusses the processes for critically appraising meta-analyses and for conducting a meta-analysis to synthesize research evidence for practice.

CRITICAL APPRAISAL PROCESS FOR QUALITATIVE STUDIES

Critical appraisal in qualitative research involves examining the expertise of the researchers, noting the organization and presentation of the report, discussing the strengths and weaknesses of the study, suggesting modifications for future studies, and evaluating the overall quality of the study. Thus, the guidelines in Table 26-2 will help you to critique a qualitative study. However, other standards and skills are also useful for assessing the quality of a qualitative study and the credibility of the study findings (Burns, 1989; Cutcliffe & McKenna, 1999; Patton, 2002). The skills and standards for critically appraising qualitative research are described in the following sections.

Skills Needed to Critically Appraise Qualitative Studies

The skills to critically appraise qualitative studies include (1) context flexibility; (2) inductive reasoning; (3) conceptualization, theoretical modeling, and theory analysis; and (4) transformation of ideas across levels of abstraction (Burns, 1989).

Context Flexibility

Context flexibility is the capacity to switch from one context or worldview to another, to shift perception in order to see things from a different perspective. Each worldview is based on a set of assumptions through which reality is defined. To develop the skills necessary to critique qualitative studies, you must be willing to move from the assumptions of quantitative research to those of qualitative research. This skill is not new in nursing; beginning students are encouraged to see things from the patient’s perspective. However, accomplishing this switch of context requires investing time and energy to learn more about the patient and setting aside personal, sometimes strongly held views. It is not necessary for you to become committed to a perspective to follow or apply its logical structure. In fact, all scholarly work requires a willingness and ability to examine and evaluate works from diverse perspectives. For example, analysis of the internal structure of a theory requires this same process.

Inductive Reasoning Skills

Although all research requires skill in both deductive and inductive reasoning, the transformation process used during data analysis in qualitative research is based on inductive reasoning. Individuals conducting a critical appraisal of a qualitative study must be able to exercise skills in inductive reasoning to follow the researcher’s logic. This logic is revealed in the systematic move from the concrete descriptions in a particular study to the abstract level of science.

Conceptualization, Theoretical Modeling, and Theory Analysis Skills

Qualitative research is oriented toward theory construction. Therefore, an effective reviewer of qualitative research needs to have skills in conceptualization, theoretical modeling, and theory analysis. The theoretical structure in a qualitative study is developed inductively and is expected to emerge from the data. The reviewer must be able to follow the logical flow of thought of the researcher and be able to analyze and evaluate the adequacy of the resulting theoretical schema, as well as its connection to theory development within the discipline (Patton, 2002).

Transforming Ideas across Levels of Abstraction

Closely associated with the necessity of having skills in theory analysis is the ability to follow the transformation of ideas across several levels of abstraction and to judge the adequacy of the transformation. Whenever you review the literature, organize ideas from the review, and then modify those ideas in the process of developing a summary of the existing body of knowledge, you are involved in the transformation of ideas. Developing a qualitative research report requires transforming ideas across levels of abstraction. Those examining the report evaluate the adequacy of this transformation process.

Standards for Critical Appraisal of Qualitative Studies

Multiple problems can occur in qualitative studies, as in quantitative studies. However, the problems are likely to be different. Reviewers not only need to know the problems that are likely to occur, but they also must be able to determine the probability that the problem may have occurred in the study being evaluated. A scholarly appraisal includes a balanced evaluation of the study’s strengths and limitations. Five standards have been proposed to evaluate qualitative studies: descriptive vividness, methodological congruence, analytical preciseness, theoretical connectedness, and heuristic relevance (Burns, 1989; Johnson, 1999). The following sections describe these standards and the threats to them.

Standard I: Descriptive Vividness

Descriptive vividness, or validity, refers to the clarity and factual accuracy of the researcher’s account of the study (Johnson, 1999; Munhall, 2001). The description of the site, the study participants, the experience of collecting the data, and the thinking of the researcher during the process needs to be presented so clearly and accurately that the reader has the sense of personally experiencing the event. Glaser and Strauss (1965) suggested that the researcher should “describe the social world studied so vividly that the reader can almost literally see and hear its people” (p. 9). Because one of the assumptions of qualitative research is that all data are context specific, the evaluator of a study must understand the context of that study. From this description, the reader gets a sense of the data as a whole as they are collected and the reactions of the researcher during the data collection and analysis processes. A contextual understanding of the whole is essential and a prerequisite to your capability to evaluate the study in light of the other four standards.

Threats to Descriptive Vividness:

1. The researcher failed to include essential descriptive information.

2. The description in the report lacked clarity, depth, or both.

3. The report lacked factual accuracy in the description of the participants and setting (Johnson, 1999).

4. The description in the report lacked authenticity, credibility, or trustworthiness (Beck, 1993; Patton, 2002).

5. The researcher had inadequate skills in writing descriptive narrative.

6. The researcher demonstrated reluctance to reveal his or her self in the written material (Burns, 1989; Kahn, 1993).

Standard II: Methodological Congruence

Evaluation of methodological congruence requires the reviewer to know the philosophy and the methodological approach that the researcher used. The researcher needs to identify the philosophy and methodological approach and cite sources where the reviewer can obtain further information (Beck, 1994; Munhall, 2001). Methodological excellence has four dimensions: rigor in documentation, procedural rigor, ethical rigor, and auditability.

Rigor in Documentation: Rigor in documentation requires the researcher to provide a comprehensive presentation of the following study elements: phenomenon, purpose, research question, justification of the significance of the phenomenon, identification of assumptions, identification of philosophy, researcher credentials, the context, the role of the researcher, ethical implications, sampling and study participants, data-gathering strategies, data analysis strategies, theoretical development, conclusions, implications and suggestions for further study and practice, and a literature review. The reviewer examines the study elements or steps for completeness and clarity and identifies any threats to rigor in documentation.

Procedural Rigor: Another dimension of methodological congruence is the rigor of the researcher in applying selected procedures for the study. To the extent possible, the researcher needs to make clear the steps taken to ensure that data were accurately recorded and that the data obtained are representative of the data as a whole (Knafl & Howard, 1984; Patton, 2002). All researchers have bias, but reflexivity needs to be used in qualitative studies to reduce bias. Reflexivity is an analytical method in which the “researcher actively engages in critical self reflection about his or her potential biases and predispositions” to reduce their impact on the conduct of the study (Johnson, 1999, p. 103). Methodological congruence can also be promoted by extended fieldwork, where the researcher collects data in the study setting for an extended period to ensure accuracy. When evaluating a qualitative study, examine the description of the data collection process and the study findings for threats to procedural rigor.

1. The researcher asked the wrong questions. The questions need to tap the participants’ experiences, not their theoretical knowledge of the phenomenon.

2. The questions included terminology from the theoretical orientation of the researcher (Kirk & Miller, 1986; Knaack, 1984).

3. The informant might have misinformed the researcher, for several reasons. The informant might have had an ulterior motive for deceiving the researcher. Some individuals might have been present who inhibit free expression by the informant. The informant might have wanted to impress the researcher by giving the response that seemed the most desirable (Dean & Whyte, 1958).

4. The informant did not observe the details requested or was not able to recall the event and substituted instead what he or she supposed happened (Dean & Whyte, 1958).

5. The researcher placed more weight on data obtained from well-informed, articulate, high-status individuals (an elite bias) than on data from those who were less articulate, obstinate, or of low status (Miles & Huberman, 1994).

6. The presence of the researcher distorted the event being observed.

7. The researcher’s involvement with the study participants distorted the data (LeCompte & Goetz, 1982).

8. Atypical events were interpreted as typical.

9. The informants lacked credibility (Becker, 1958).

10. An insufficient amount of data was gathered.

11. An insufficient length of time was spent in the setting gathering the data.

12. The approaches for gaining access to the site, the participants, or both were inappropriate.

13. The researcher failed to keep in-depth field notes.

14. The researcher failed to use reflexivity or critical self-reflection to assess his or her potential biases and predispositions (Patton, 2002).

Ethical Rigor: Ethical rigor requires the researcher to recognize and discuss the ethical implications related to the conduct of the study. Consent is obtained from the study participants and documented. The report must indicate that the researcher took action to ensure that the rights of the participants were protected during the consent process, data collection and analysis, and communication of the findings (Munhall, 1999, 2001). Examine the consent process, the data-gathering process, and the results for potential threats to ethical rigor.

1. The researcher failed to inform the participants of their rights.

2. The researcher failed to obtain consent from the participants.

3. The researcher failed to protect the participants’ rights during the conduct of the study.

4. The results of the study were presented in such a way that they revealed the identity of individual participants (Munhall, 2001).

Auditability: A fourth dimension of methodological congruence is the rigorous development of a decision trail (Miles & Huberman, 1994; Patton, 2002). Guba and Lincoln (1982) referred to this dimension as auditability. To achieve this end, the researcher must report all decisions involved in the transformation of data to the theoretical schema. This reporting should be in sufficient detail to allow a second researcher, using the original data and the decision trail, to arrive at conclusions similar to those of the original researcher. When critically appraising the study, examine the decision trail for threats to auditability.

1. The description of the data collection process was inadequate.

2. The researcher failed to develop or identify the decision rules for arriving at ratings or judgments.

3. The researcher failed to record the nature of the decisions, the data on which they were based, and the reasoning that entered into the decisions.

4. The evidence for conclusions was not presented (Becker, 1958).

5. Other researchers were unable to arrive at similar conclusions after applying the decision rules to the data.

Standard III: Analytical Preciseness

The analytical process in qualitative research involves a series of transformations during which concrete data are transformed across several levels of abstraction. The outcome of the analysis is a theoretical schema that imparts meaning to the phenomenon under study. The analytical process occurs primarily within the reasoning of the researcher and is frequently poorly described in published reports. Some transformations may occur intuitively. However, analytical preciseness requires that the researcher make intense efforts to identify and record the decision-making processes through which the transformations are made. The processes by which the theoretical schema is cross-checked with data also need to be reported in detail.

Premature patterning may occur before the researcher can logically fit all the data within the emerging schema. Nisbett and Ross (1980) have shown that patterning happens rapidly and is the way that individuals habitually process information. The consequence may be a poor fit between data and the theoretical schema (LeCompte & Goetz, 1982; Sandelowski, 1986). Miles and Huberman (1994) suggested that plausibility is the opiate of the intellectual. If the emerging schema makes sense and fits with other theorists’ explanations of the phenomenon, the researcher locks into it. For that reason, it is critical to test the schema by rechecking the fit between the schema and the original data. The participants could be asked to provide feedback on the researcher’s interpretations and conclusions to gain additional insight or verification of the theoretical schema proposed (Johnson, 1999). Beck (1993) recommended that the researcher have the “data analysis procedures reviewed by a judge panel to prevent researcher bias and selective inattention” (p. 265). When evaluating a study, examine the decision-making processes and the theoretical schema to detect threats to analytical preciseness.

Threats to Analytical Preciseness:

1. The interpretive statements do not correspond with the findings (Parse, Coyne, & Smith, 1985).

2. The categories, themes, or common elements are not logical.

3. The samples are not representative of the class of joint acts referred to by the researcher (Denzin, 1989).

4. The set of categories, themes, or common elements fails to set forth a whole picture.

5. The set of categories, themes, or common elements is not inclusive of data that exist.

6. The data are inappropriately assigned to categories, themes, or common elements.

7. The inclusion and exclusion criteria for categories, themes, or common elements are not consistently followed.

8. The working hypotheses or propositions are not identified or cannot be verified by data.

9. Various sources of evidence fail to provide convergence.

10. The evidence is incongruent.

11. The participants fail to validate findings when appropriate (Johnson, 1999).

12. The conclusions are not data based or do not encompass all the data.

13. The data are made to appear more patterned, regular, or congruent than they actually are (Beck, 1993; Sandelowski, 1986).

Standard IV: Theoretical Connectedness

Theoretical connectedness requires that the theoretical schema developed from the study be clearly expressed, logically consistent, reflective of the data, and compatible with the knowledge base of nursing.

Threats to Theoretical Connectedness:

1. The findings are trivialized (Goetz & LeCompte, 1981).

2. The concepts are inadequately refined.

3. The concepts are not validated by data.

4. The set of concepts lacks commonality.

5. The relationships between concepts are not clearly expressed.

6. The proposed relationships between concepts are not validated by data.

7. The working propositions are not validated by data.

8. Data are distorted during development of the theoretical schema (Bruyn, 1966).

9. The theoretical schema fails to yield a meaningful picture of the phenomenon studied.

10. A conceptual framework or map is not derived from the data.

Standard V: Heuristic Relevance

To be of value, the results of a study need heuristic relevance for the reader. This value is reflected in the reader’s capacity to recognize the phenomenon described in the study, its theoretical significance, its applicability to nursing practice situations, and its influence on future research activities. The dimensions of heuristic relevance include intuitive recognition, relationship to the existing body of knowledge, and applicability.

Intuitive Recognition: Intuitive recognition means that when individuals are confronted with the theoretical schema derived from the data, it has meaning within their personal knowledge base. They immediately recognize the phenomenon being described by the researcher and its relationship to a theoretical perspective in nursing.

Relationship to the Existing Body of Knowledge: The researcher must review the existing body of knowledge, particularly the nursing theoretical perspective from which the phenomenon was approached, and compare them with the findings of the study. The study should have intersubjectivity with existing theoretical knowledge in nursing and previous research. The researcher should explore reasons for differences with the existing body of knowledge. When critically appraising a study, examine the strength of the link of study findings to the existing knowledge.

Threats to the Relationship to the Existing Body of Knowledge:

1. The researcher failed to examine the existing body of knowledge.

2. The process studied was not related to nursing and health.

3. The results lack correspondence with the existing knowledge base in nursing (Parse et al., 1985).

Applicability: Nurses need to be able to integrate the findings into their knowledge base and apply them to nursing practice situations. The findings also need to contribute to theory development (Munhall, 2001; Patton, 2002). Examine the discussion section of the research report for threats to applicability.

1. The findings are not significant for the discipline of nursing.

2. The report fails to achieve methodological congruence.

By applying these five standards in critically appraising qualitative studies, you can determine the strengths and weaknesses of a study. A summary of the strengths will indicate adherence to the standards, and a summary of weaknesses will indicate potential threats to the integrity of the study. A final evaluation of the study involves applying the standard of heuristic relevance. This standard is used to determine the quality of the study. It also establishes the usefulness of the study findings for the development and refinement of nursing knowledge and for the provision of evidence-based practice.

SUMMARY

• Critical appraisal of research involves carefully examining all aspects of a study to judge its merits, limitations, meaning, validity, and significance in light of previous research experience, knowledge of the topic, and clinical expertise

• Critical appraisals of research are conducted (1) to summarize evidence for practice, (2) to provide a basis for future research, (3) to evaluate presentations and publications of studies, (4) for abstract section for a conference, (5) to select an article for publication, and (6) to evaluate research proposals for funding and implementation in clinical agencies.

• The critical appraisal process for quantitative research includes the following steps: comprehension, comparison, analysis, evaluation, and conceptual clustering.

• The comprehension step involves understanding the terms and concepts in the report, as well as identifying study elements.

• The comparison step requires knowledge of what each step of the research process should be like and the ideal is compared with the real.

• The analysis step involves examining the logical links connecting one study element with another.

• The evaluation step involves examining the meaning, validity, and significance of the study according to set criteria.

• Conceptual clustering involves generating new questions, developing and refining theory, and synthesizing research for use in practice.

• The critical appraisal process in qualitative research includes the skills of (1) context flexibility; (2) inductive reasoning; (3) conceptualization, theoretical modeling, and theory analysis; and (4) transformation of ideas across levels of abstraction.

• The standards proposed to evaluate qualitative research include descriptive vividness, methodological congruence, analytical preciseness, theoretical connectedness, and heuristic relevance.

• Descriptive vividness means that the site, the study participants, the experience of collecting data, and the thinking of the researcher during the process are presented so clearly that the reader has the sense of personally experiencing the event.

• Methodological congruence has four dimensions: rigor in documentation, procedural rigor, ethical rigor, and auditability.

• Analytical preciseness is essential to perform a series of transformations in which concrete data are transformed across several levels of abstraction.

• Theoretical connectedness requires that the theoretical schema developed from the study be clearly expressed, logically consistent, reflective of the data, and compatible with the knowledge base of nursing.

• Heuristic relevance includes intuitive recognition, a relationship to the existing body of knowledge, and applicability.

REFERENCES

American Psychological Association. Publication manual of the American Psychological Association, (5th ed.). Washington, DC: Author, 2001.

Beck, C.T. Qualitative research: The evaluation of its credibility, fittingness, and auditability. Western Journal of Nursing Research. 1993;15(2):263–266.

Beck, C.T. Reliability and validity issues in phenomenological research. Western Journal of Nursing Research. 1994;16(3):254–267.

Beck, C.T. Focus on research methods. Facilitating the work of a meta-analyst. Research in Nursing & Health. 1999;22(6):523–530.

Becker, H.S. Problems of inference and proof in participant observation. American Sociological Review. 1958;23(6):652–660.

Bowman, A., Wyman, J.F., Peters, J. Methods. The operations manual: A mechanism for improving the research process. Nursing Research. 2002;51(2):134–138.

Brown, S.J. Knowledge for health care practice: A guide to using research evidence. Philadelphia: Saunders, 1999.

Brown, S.J. Focus on research methods. Nursing intervention studies: A descriptive analysis of issues important to clinicians. Research in Nursing & Health. 2002;25(4):317–327.

Bruyn, S.T. The human perspective in sociology. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall, 1966.

Burns, N. Standards for qualitative research. Nursing Science Quarterly. 1989;2(1):44–52.

Burns, N., Grove, S.K. Understanding nursing research, (4th ed.). Philadelphia: Saunders, 2007.

Corty, E.W. Using and interpreting statistics: A practical text for the health, behavioral, and social sciences. St. Louis: Mosby, 2007.

Crookes, P., Davies, S. Essential skills for reading and applying research in nursing and health care. Edinburgh, Scotland: Baillière Tindall, 1998.

Cutcliffe, J.R., McKenna, H.P. Establishing the credibility of qualitative research findings: The plot thickens. Journal of Advanced Nursing. 1999;30(2):374–380.

Dean, J.P., Whyte, W.F. How do you know if the informant is telling the truth? Human Organization. 1958;17(2):34–38.

Denzin, N.K. The research act, (3rd ed.). New York: McGraw-Hill, 1989.

Doran, D.M. Nursing-sensitive outcomes: State of the science. Sudbury, MA: Jones & Bartlett, 2003.

Glaser, B., Strauss, A.L. Discovery of substantive theory: A basic strategy underlying qualitative research. American Behavioral Scientist. 1965;8(1):5–12.

Goetz, J.P., LeCompte, M.D. Ethnographic research and the problem of data reduction. Anthropology and Education Quarterly. 1981;12(1):51–70.

Guba, E.G., Lincoln, Y.S. Effective evaluation. Washington, DC: Jossey-Bass, 1982.

Houser, J. Nursing research: Reading, using, and creating evidence. Sudbury, MA: Jones & Bartlett, 2008.

Johnson, R.B. Examining the validity structure of qualitative research. In: Pyrczak F., ed. Evaluating research in academic journals: A practical guide to realistic evaluation. Los Angeles: Pyrczak; 1999:103–108.

Kahn, D.L. Ways of discussing validity in qualitative nursing research. Western Journal of Nursing Research. 1993;15(1):122–126.

Kerlinger, F.N., Lee, H.B. Foundations of behavioral research, (4th ed.). Fort Worth, TX: Harcourt College, 2000.

Kim, M.J., Felton, F. The current generation of research proposals: Reviewers’ viewpoints. Nursing Research. 1993;42(2):118–119.

Kirk, J., Miller, M.L. Reliability and validity in qualitative research. Beverly Hills, CA: Sage, 1986.

Knaack, P. Phenomenological research. Western Journal of Nursing Research. 1984;6(1):107–114.

Knafl, K.A., Howard, M.J. Interpreting and reporting qualitative research. Research in Nursing & Health. 1984;7(1):17–24.

Larson, E. Exclusion of certain groups from clinical research. Image: Journal of Nursing Scholarship. 1994;26(3):185–190.

LaValley, M. Methods article: A consumer’s guide to meta-analysis. Arthritis Care and Research. 1997;10(3):208–213.

LeCompte, M.D., Goetz, J.P. Problems of reliability and validity in ethnographic research. Review of Educational Research. 1982;52(1):31–60.

LeFort, S.M. The statistical versus clinical significance debate. Image: Journal of Nursing Scholarship. 1993;25(1):57–62.

LoBiondo-Wood, G.L., Haber, J. Nursing research: Methods and critical appraisal for evidence-based practice, (6th ed.). St. Louis: Mosby, 2005.

Meleis, A.I. Theoretical nursing: Development and progress, (2nd ed.). Philadelphia: Lippincott, 1991.

Melnyk, B.M., Fineout-Overholt, E. Evidence-based practice in nursing & healthcare: A guide to best practice. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, 2005.

Miles, M.B., Huberman, A.M. Qualitative data analysis: A source book of new methods, (2nd ed.). Beverly Hills, CA: Sage, 1994.

Morse, J.M., Dellasega, C., Doberneck, B. Evaluating abstracts: Preparing a research conference. Nursing Research. 1993;42(5):308–310.

Munhall, P.L. Ethical considerations in qualitative research. In Munhall P.L., Boyd C.O., eds.: Nursing research: A qualitative perspective, (2nd ed.), New York: National League for Nursing, 1999.

Munhall, P.L. Nursing research: A qualitative perspective, (3rd ed.). Sudbury, MA: Jones & Bartlett, 2001.

Nieswiadomy, R.M. Foundations of nursing research, (5th ed.). Upper Saddle River, NJ: Pearson Prentice Hall, 2008.

Nisbett, R., Ross, L. Human inference: Strategies and shortcomings of social judgment. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall, 1980.

Oberst, M.T. Warning: Believing this report may be hazardous. Research in Nursing & Health. 1992;15(2):91–92.

Parse, R.R., Coyne, A.B., Smith, M.J. Nursing research: Qualitative methods. Bowie, MD: Brady, 1985.

Patton, M.Q. Qualitative research and evaluation methods, (3rd ed.). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage, 2002.

Peat, J., Mellis, C., Williams, K., Xuan, W. Health science research: A handbook of quantitative methods. Thousand Oaks: CA: Sage, 2002.

Pinch, W.J. Synthesis: Implementing a complex process. Nurse Educator. 1995;20(1):34–40.

Polit, D.F., Beck, C.T. Nursing research: Generating and assessing evidence for nursing practice, (8th ed.). Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, 2008.

Pyrczak, F. Evaluating research in academic journals: A practical guide to realistic evaluation. Los Angeles: Pyrczak, 1999.

Resnick, B., Concha, B., Burgess, J.G., Fine, M.L., West, L., Baylor, K., et al. Brief report. Recruitment of older women: Lessons learned from the Baltimore hip studies. Nursing Research. 2003;52(4):270–273.

Roberts, W.D., Stone, P.W. Ask an Expert: How to choose and evaluate a research instrument. Applied Nursing Research. 2004;16(10):70–72.

Rudy, E.B., Kerr, M.E. Auditing research studies. Nursing Research. 2000;49(2):117–120.

Ryan-Wenger, N. Guidelines for critique of a research report. Heart & Lung. 1992;21(4):394–401.

Sandelowski, M. The problem of rigor in qualitative research. Advances in Nursing Science. 1986;8(3):27–37.

Santacroce, S.J., Maccarelli, L.M., Grey, M. Methods: Intervention fidelity. Nursing Research. 2004;53(1):63–66.

Sidani, S., Braden, C.J. Evaluation of nursing interventions: A theory-driven approach. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage, 1998.

Stone, P.W. What is a systematic review? Applied Nursing Research. 2002;15(1):52–53.

Swanson, E.A., McCloskey, J.C., Bodensteiner, A. Publishing opportunities for nurses: A comparison of 92 U. S. journals. Image: Journal of Nursing Scholarship. 1991;23(1):33–38.

Tibbles, L., Sanford, R. The research journal club: A mechanism for research utilization. Clinical Nurse Specialist. 1994;8(1):23–26.

Tilden, V., Peer review: Evidence-based or sacred cow?. Nursing Research, 51. 2002:275. [5].

Werley, H.H., Fitzpatrick, J.J., Annual review of nursing research, Vol. 1. New York: Springer, 1983.

Whittemore, R. Methods. Combining evidence in nursing research: Methods and implications. Nursing Research. 2005;54(1):56–62.