Chapter 15 Developing a culture of safety and quality

Mastery of content will enable you to:

• Define the key terms listed.

• Describe how unmet basic physiological needs of oxygen, fluids, nutrition and temperature can threaten patients’ safety.

• Define the role of the Australian Commission on Safety and Quality in Healthcare.

• Discuss the purpose of the Australian Safety and Quality Framework for Healthcare.

• Discuss the specific risks to safety related to developmental age.

• Describe the four categories of risks in a healthcare agency.

• Describe assessment activities designed to identify patients’ physical, psychosocial and cognitive status as it relates to their safety status.

• State nursing diagnoses associated with risks to safety.

• Develop care plans for patients whose safety is threatened.

• Describe nursing interventions specific to patients’ age for reducing risk of falls, fires, poisonings and electrical hazards.

• Describe methods for evaluating interventions designed to maintain or promote safety.

The Australian Commission on Safety and Quality in Healthcare is the governing body in Australia, with a responsibility to lead and coordinate the safety and quality agenda in Australia’s healthcare system. The Australian Charter of Healthcare Rights describes the rights of patients and other consumers of the Australian health system (Box 15-1). These rights ensure that the quality of care is safe and of a high standard, wherever and whenever care is provided (Australian Commission on Quality and Safety in Healthcare, 2008). In conjunction with the establishment of the Australian Charter of Healthcare Rights, the Australian Safety and Quality Framework for Health Care initiative was launched (Australian Commission on Quality and Safety in Healthcare, 2010). The framework provides clear guidelines for the delivery of safe and high-quality care for all Australians, and sets out the required strategies to achieve this initiative. Three core principles for safe and high-quality care are specified in the framework: that care provided is consumer centred, driven by information and organised for safety.

BOX 15-1 AUSTRALIAN CHARTER OF HEALTHCARE RIGHTS

Australian Commission on Quality and Safety in Health Care (ACQSHC) 2008 Australian Charter of Health Care Rights. Online. Available at www.safetyandquality.gov.au/our-work/national-perspectives/charter-of-healthcare-rights 18 Feb 2012.

| WHAT CAN I EXPECT FROM THE AUSTRALIAN HEALTH SYSTEM? | |

|---|---|

| MY RIGHTS | WHAT THIS MEANS |

| Access | |

| I have a right to healthcare. | I can access services to address my healthcare needs. |

| Safety | |

| I have a right to receive safe and high-quality care. | I receive safe and high-quality health services, provided with professional care, skill and competence. |

| Respect | |

| I have a right to be shown respect, dignity and consideration. | The care provided shows respect to me and my culture, beliefs, values and personal characteristics. |

| Communication | |

| I have a right to be informed about services, treatment, options and costs in a clear and open way. | I receive open, timely and appropriate communication about my healthcare in a way I can understand. |

| Participation | |

| I have a right to be included in decisions and choices about my care. | I may join in making decisions and choices about my care and about health service planning. |

| Privacy | |

| I have a right to privacy and confidentiality of my personal information. | My personal privacy is maintained and proper handling of my personal health and other information is assured. |

| Comment | |

| I have a right to comment on my care and to have my concerns addressed. | I can comment on or complain about my care and have my concerns dealt with properly and promptly. |

The Health Quality and Safety Commission New Zealand was formally established on 1 December 2010, under the auspices of the New Zealand Public Health and Disability Amendment Act 2010, and is responsible for assisting providers across the whole health and disability sector, private and public, to improve service safety and quality and outcomes New Zealand (Health Quality and Safety Commission New Zealand, 2010).

Safety, often defined as freedom from psychological and physical injury, is a basic human need that must be met. Healthcare provided in a safe manner and a safe environment is essential for a patient’s survival and wellbeing. The nurse incorporates critical-thinking skills when using the nursing process, and is responsible for assessing the patient and the environment for hazards that threaten safety and the delivery of high-quality, evidence-based care, as well as planning and intervening appropriately to maintain a safe environment. By doing this, the nurse not only provides safe acute, restorative and continuing care, but is also an active participant in health promotion and contributes to a healthcare system which provides high-quality care.

Scientific knowledge base

Environmental safety

A patient’s environment includes all the many physical and psychosocial factors that influence or affect the experiences and outcomes of that patient. This broad definition of environment incorporates all of the settings in which the nurse and patient interact; for example, the home, community centre, school, clinic, hospital and extended-care facility. Safety in these settings reduces the incidence of illness and injury, shortens the length of treatment and/or hospitalisation, improves or maintains a patient’s functional status and increases the patient’s sense of wellbeing. A safe patient environment is an environment in which basic needs are met, physical hazards are reduced, transmission of pathogens is reduced, sanitation is maintained and pollution is controlled.

Nurses also require a safe environment that affords protection from hazards and allows them to function at an optimal level.

Providing a safe patient environment

Basic needs

Physiological needs, including the need for sufficient oxygen, nutrition and optimum temperature and humidity, influence a person’s safety.

OXYGEN

It is important in nursing practice to be aware of factors in a patient’s environment that decrease the amount of available oxygen. A common environmental hazard in the home is an improperly functioning heating system. A furnace that is not properly vented or a car left running inside a closed garage may introduce carbon monoxide into the environment. Carbon monoxide is a colourless, odourless, poisonous gas produced by the incomplete combustion of carbon-containing fuels. Carbon monoxide binds strongly to haemoglobin, preventing the formation of oxyhaemoglobin and thus reducing the amount of oxygen delivered to the tissues (see Chapter 40). Low concentrations can cause nausea, dizziness, headache, fatigue and confusion. Higher concentrations can be fatal (National Safety Council, 2009a). Seasonal inspections and cleaning of heating systems and appliances should be done in private homes as well as in institutions.

Oxygen is indicated in the healthcare setting for many critical conditions and its use can prevent serious life-threatening complications resulting from hypoxaemia. However, there is a risk of serious injury and even death if it is not administered and managed appropriately. Oxygen is considered a drug when used other than in an emergency situation, and should be prescribed by a doctor. Common risks associated with oxygen use in the healthcare setting include incorrectly prescribed oxygen, patients on oxygen therapy not monitored properly, administration problems and faulty and/or missing equipment. Therefore, oxygen safety in healthcare settings includes the establishment of clinical practice guidelines such as the following:

• oxygen is a drug and use outside of an emergency situation should be prescribed by a medical practitioner

• oxygen relieves hypoxaemia but does not improve ventilation or treat the underlying cause for the hypoxaemia

• oxygen therapy should be closely monitored and assessed at regular intervals.

To minimise risk, close monitoring and assessment of oxygen therapy at regular intervals, assessment and monitoring of the patient’s oxygen saturation (SpO2) and partial carbon dioxide pressure (pCO2) regularly, medical, nursing and allied health staff briefing, and awareness that therapeutic procedures and handling may increase the patient’s oxygen consumption and lead to increasing hypoxaemia is required to be communicated to all clinical staff (Royal Children’s Hospital Melbourne, 2012).

NUTRITION

Meeting nutritional needs adequately and safely requires environmental controls and knowledge. In the home, a person needs a refrigerator with a freezer compartment to keep perishable foods fresh. A clean water supply is needed for drinking and to wash fresh produce and dishes. Provisions for garbage collection are necessary to maintain sanitary conditions.

Foods that are inadequately prepared or stored, or that are subject to unsanitary conditions, increase a person’s risk of infections and food poisoning. Bacterial infections result from eating food contaminated by bacteria such as Escherichia coli or Salmonella, Shigella or Listeria organisms. Food poisoning is caused by ingestion of bacterial toxins produced in food; staphylococcal and clostridial bacteria are the most common causes. Although most food-borne diseases are caused by bacterial contamination, transmission of hepatitis A can occur from ingestion of food or water contaminated with HAV (hepatitis A virus). Hepatitis A contamination occurs when there has been faecal contamination of food, water or milk (Food Safety Information Council, 2003).

For illnesses caused by bacterial contamination, the onset of symptoms may be very rapid or may take a week or longer to appear. The onset of symptoms for hepatitis A ranges from 15 to 50 days (Fiore, 2004). In general, assessments for suspected food infections or poisoning encompass obtaining a patient’s history, including a detailed dietary assessment for the past week; conducting an examination of gastrointestinal (GI) and central nervous system (CNS) function; observing for a fever; and analysing cultures of faeces and vomitus. Suspected food and water sources are also studied. Preventive measures include thorough handwashing before handling food, adequate cooking and proper storage and refrigeration of perishable foods.

Food standards in Australia are covered by a range of legislations (Food Standards Australia and New Zealand, 2012). This authority oversees all aspects of food production, manufacture, distribution, labelling and retailing. It is also responsible for the recall of substandard food products.

TEMPERATURE AND HUMIDITY

The comfort zone for environmental temperature varies among individuals, but the usual comfort range is between 18°C and 24°C. Temperature extremes that occur during the winter and summer affect not only comfort and productivity, but also safety.

Exposure to severe cold for prolonged periods causes frostbite and accidental hypothermia. Frostbite occurs when a surface area of the skin freezes as a result of exposure to extremely cold temperatures. Hypothermia occurs when the core body temperature is 35°C or below. Older adults, the young, people with cardiovascular conditions, people who have ingested drugs or alcohol to excess and the homeless are at high risk of hypothermia. A faint, irregular heart rate, slow and shallow respirations, pallor and shivering may be observed. Death may ensue if the condition is not corrected.

Exposure to extreme heat can result in heatstroke or heat exhaustion. Chronically ill people, older adults and infants are at greatest risk of injury from extreme heat. Heat exhaustion is manifested by diaphoresis, hypotension, changes in mental status, muscle cramps and nausea. Heatstroke is a life-threatening condition with severe changes in mental status, including coma; characteristics of hyperthermia include hot, dry skin and rectal temperatures in excess of 40.5°C.

The relative humidity of the air in the environment may affect health and safety. Relative humidity is the amount of water vapour in the air compared with the maximum amount of water vapour that the air could contain at the same temperature. The comfort zone for humidity varies from person to person, but most people are comfortable when the humidity is between 60% and 70%.

When the relative humidity is high, the skin’s moisture evaporates slowly. Thus, during hot, humid weather, people feel uncomfortably hot and sticky. If the relative humidity is low, the skin’s moisture evaporates quickly. This is why, when the temperature is 30°C, people feel more comfortable if the relative humidity is 30% than if it is 85%.

Increasing the environmental humidity can have therapeutic benefits. Children and adults with upper respiratory tract infections may experience some improvement in their symptoms when a humidifier is placed in the room while they sleep. Increasing the relative humidity of inhaled air liquefies secretions and improves breathing. It is important to follow the manufacturer’s directions regarding the cleaning and maintenance of home humidifiers, to reduce the contamination of the water.

Physical hazards

Physical hazards in the community and healthcare settings place people at risk of accidental injury and death. Motor vehicle accidents are a leading cause of unintentional death, along with falls, poisonings, drownings, fires and burns (Australian Bureau of Statistics, 2006). Deaths from accidental falls are relatively common, particularly in people over 75 years of age (Australian Bureau of Statistics, 2006). Falls are the most common cause of hospital admissions for trauma to older patients in Australia. Thirty to forty-five per cent of persons living in a community setting fall at least once a year. Among people over age 65 years, falls account for 90% of all fractures and are the leading cause of injury-related death (Bergeron and others, 2006). Many physical hazards, especially those contributing to falls, can be minimised through adequate lighting, reduction of obstacles, control of bathroom hazards and security measures. Some of the major areas of potential hazards are outlined below; however, prevention involves maintaining appropriate activity levels, a healthy lifestyle and assessing the potential for falls (NSW Health, 2010). Box 15-2 provides one example of a home safety checklist.

BOX 15-2 HOME SAFETY CHECKLIST

BATHROOM AND TOILET

• Slip-resistant mats on the floor

• Shower easy to access without stepping over a raised edge or hob

• Secure handrail in shower or on wall next to bath to avoid holding on to taps or towel rail to get out

• Soap and shampoo within easy reach without bending

OUTSIDE THE HOME

• Paths and entrances well lit at night

• Steps with a sturdy, easy-to-grip handrail

• Edges of steps clearly marked and with slip-resistant strip

• Step ladder short and sturdy with slip-resistant feet

• Clothes line easy to access and reach

• Garden kept free of trip hazards, such as tools and hoses

ELECTRICAL AND FIRE HAZARDS*

• Batteries for all detectors tested regularly and changed annually on a specific date such as ‘daylight saving changeover day’

• Chimneys and stoves checked for proper ventilation

• Extension cords in good condition and used appropriately

• Appliances in good working order and located away from water sources

• Fire extinguisher near cooking areas

• Combustible items such as oil-based paints, petrol and oily rags stored in a garage and/or basement

• Torches available and handy to access

From NSW Health 2010 Staying active and on your feet. Sydney, NSW Health. Online. Available at www.activeandhealthy.nsw.gov.au/assets/pdf/stayactive_web_final.pdf 28 Jun 2012. *Adapted from Ebersole P and others 2008 Toward healthy aging: human needs and nursing response, ed 7. St Louis, Mosby.

LIGHTING

Adequate lighting reduces physical hazards by illuminating areas in which people move and work. Outside the home, there should be adequate lighting on all walkways. Outdoor lighting also helps protect the home and its inhabitants from crime. Well-lit garages, paths and doorways discourage intruders from entering the premises or hiding in shadows.

Inside the house, halls, staircases and individual rooms should be adequately lit so that residents can safely carry out the activities of daily living (ADLs). Night-lights in dark halls, bathrooms and the rooms of children and older adults help reduce the risk of falls. A night-light in a guest room can help orient an overnight guest who needs to get up in the middle of the night. Artificial lighting should be soft and non-glaring, as sensitivity to glare increases with ageing (Ebersole and others, 2008).

OBSTACLES

Injuries in the home often result from people tripping over or coming into contact with common household objects, including doormats, small rugs on the stairs and floor, wet spots on the floor and clutter on bedside tables, shelves, the top of the refrigerator and bookshelves. The risk of falling over obstacles is present for all age groups; however, it is greatest for older adults. Falls are usually a result of a combination of intrinsic risk factors (e.g. illness, drug therapy or alcohol use) and extrinsic or environmental factors. In some cases an obstacle or extrinsic factor may be the only cause of a fall. Intrinsic factors may be difficult to modify or eliminate, but extrinsic ones are usually not.

To reduce the risk of injury, all obstacles should be removed from halls and other heavily travelled areas. Necessary objects such as clocks, glasses, tissues or medications should remain on bedside tables within reach of adults (but out of the reach of children in the home). Care should also be taken to ensure that small tables are secure and have stable, straight legs. Non-essential items should be placed in drawers to eliminate clutter. If small rugs are used, they should be secured with a non-slip pad or skid-resistant adhesive strips. Any carpeting on the stairs should be secured with carpet tacks.

Obstacles encountered in the healthcare setting may also act as potential risks caused by the same sorts of hazards as those found in the home, such as wet spots on floors, cluttered overbed tables and bedside lockers, misplaced chairs and hospital equipment such as lifting machines and other large pieces of medical equipment. As in the home, to reduce the risk of injury, such obstacles should be removed from heavily trafficked patient areas.

BATHROOM HAZARDS

Accidents such as falls, burns and poisoning often occur in the bathroom. Falls in the bathroom can be reduced through the use of secure, easily seen grab-bars and handrails and non-slip adhesive tape on the bottom of the bath. Lowering the thermostat setting on the water heater reduces the risk of scalding. In the medicine cabinet, medications should be clearly marked and kept out of the reach of children. Child-resistant caps should be on all medication containers when there are children living in the home or visiting. Medication not in use or out of date should be discarded by returning it to the local chemist/pharmacist.

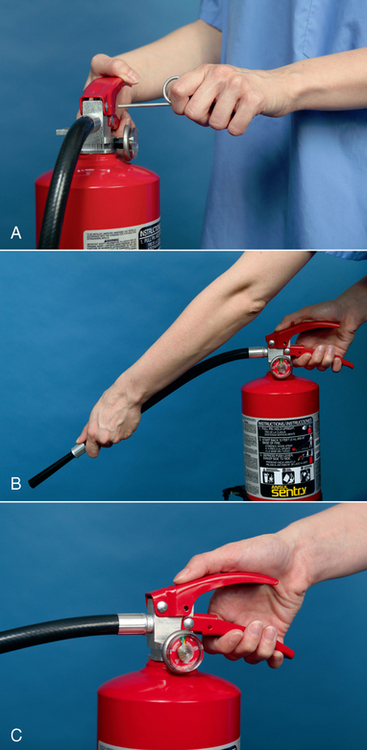

SECURITY

Home fires are not a major cause of death and injury in Australia (fewer than 100 per year), and with the campaign to encourage the use of smoke detectors, the figures seem to be moving downwards. The most common causes of death are falling asleep while an ignition source is burning, children playing with a heat source, and faulty or malfunctioning appliances or equipment (Australian Bureau of Statistics, 2000). Smoke detectors (Figure 15-1) should be installed strategically throughout the home, and suitable fire extinguishers should be installed near the kitchen and any workshop areas. Doors should not be deadlocked from the inside while the premises are occupied.

Older homes should be inspected for lead. Although lead has not been used in house paint or plumbing materials for many decades, older homes continue to contain high lead levels. Soil and water systems may also be contaminated. Poisoning may occur from swallowing or inhaling lead. Children under the age of 6 years and pregnant women are at the greatest risk of poisoning (National Safety Council, 2009b).

Asbestos has commonly been used in construction materials for insulation and as a fire retardant. Although many asbestos-containing products are no longer available, it can be found in many older homes. The widespread use of asbestos as a construction material has created occupational hazards for builders (of developing cancers) and environmental hazards (if the asbestos sheet is unsealed or broken) for homeowners and renovators (US Environmental Protection Agency, 2007).

Precautions need to be taken to ensure security to homes from intruders. When assessing their home for safety, individuals should evaluate doors and windows for the presence and quality of locks. They should be encouraged to join Neighbourhood Watch and work closely with law enforcement personnel to reduce crime in their neighbourhoods.

TRANSMISSION OF PATHOGENS

A pathogen is a microorganism capable of producing an illness. One of the most effective ways of limiting the transmission of pathogens is the medical aseptic practice of hand-washing (see Chapter 29). Healthcare workers, consumers and patients must be instructed in the proper hand-washing technique and encouraged to use it frequently in the home and hospital.

The transmission of disease from person to person can also be reduced, and in some cases prevented, by immunisation. Immunisation is the process by which resistance to an infectious disease is produced or augmented. Active immunity is acquired by injecting a small amount of attenuated (weakened) or dead organisms or modified toxins from the organism (toxoids) into the body. Passive immunity occurs when antibodies produced by other persons or animals can be introduced into a person’s bloodstream for protection against a pathogen.

The human immunodeficiency virus (HIV)—the pathogen that causes acquired immune deficiency syndrome (AIDS)—and the hepatitis B and C viruses are transmitted through blood and other body fluids. Drug abusers who share syringes and needles have an increased risk of acquiring these viruses. Safe sexual practices, including the correct use of condoms and engaging in monogamous relationships, reduce the risk of these diseases, as well as that of other sexually transmitted infections (STIs). The first needle exchange program in Australia was piloted in Sydney in 1986, and there are now over 3000 programs set up across the country. Since the inception of needle exchange programs in New South Wales, fewer than 20 new reported cases of HIV infection are attributed to injection with infected needles. The World Health Organization considers the provision of sterile needles and syringes to be fundamental to any HIV and hepatitis B and C prevention program (NSW Health, 2006). When caring for all patients, regardless of their known health history, nurses should always use standard precautions to protect themselves from contact with blood and body fluids (see Chapter 29).

The transmission of disease is also controlled by adequate disposal of human waste through proper construction and repair of sewers and drains. Insect and rodent control plays a vital role in reducing the transmission of disease.

POLLUTION

A healthy environment is free of pollution. A pollutant is a harmful chemical or waste material discharged into the water, soil or air. People commonly think of pollution only in terms of air, land or water pollution, but excessive noise can also be a form of pollution that presents health risks.

Air pollution is the contamination of the atmosphere with a harmful chemical. Prolonged exposure to air pollution increases the risk of pulmonary disease. In urban areas, industrial waste and vehicle exhaust are common contributors to air pollution. Cigarette smoking is now banned in public buildings, and smoking inside the house should also be discouraged.

Land pollution of soil can be caused by improper disposal of radioactive and bioactive waste products (e.g. dioxin).

Water pollution is the contamination of the ocean, lakes, rivers and streams, usually by industrial pollutants. Water treatment facilities filter harmful contaminants from the water, but these systems may contain flaws. If water becomes contaminated, the public is notified to boil water used for drinking and cooking. Flooding often causes damage to water treatment stations and also requires the boiling of drinking and cooking water.

Noise pollution occurs when the noise level in an environment becomes uncomfortable to inhabitants. Noise levels are measured in units of sound intensity called decibels. Tolerance of noise varies from individual to individual, and is influenced by health status. Irreversible hearing loss may result from constant exposure to high sound intensity. People working in environments with high noise levels need to wear protective devices to reduce hearing loss (Figure 15-2). Adolescents should limit their exposure to intense noise such as that found at rock concerts.

A healthcare facility can also be polluted by noise. The sounds of machines, people talking and intercoms and paging systems can create increased noise levels. Even when the noise level is not high enough to affect hearing acuity, it may produce a syndrome called sensory overload. Sensory overload is a marked increase in the intensity of auditory and visual stimuli. It disrupts processing of information, and the patient no longer perceives the environment in a meaningful way.

Nursing knowledge base

Nurses, in addition to being knowledgeable about the environment, must be familiar with a patient’s developmental level; mobility, sensory and cognitive status; lifestyle choices; and knowledge of common safety precautions. They must also be aware of the special risks in agency settings. As healthcare professionals, Australasian nurses need to be aware of, and practise within, the existing safety and quality frameworks for healthcare developed by the Australian Commission on Safety and Quality in Healthcare and Safety Commission New Zealand; the requirements of the Australian Council on Healthcare Standards (ACHS) and New Zealand Health and Disability Standards; and the requirements of the Quality Improvement Council (QIC) which is responsible for the Evaluation and Quality Improvement Program (EQuIP) and the Quality Improvement and Community Services Accreditation (QICSA). The EQuIP standards form an assessment system which ensures that the current and continuing needs of the healthcare consumer are identified; for example, through a falls prevention and management program, the incidence of falls and injuries are minimised (Australian Council on Healthcare Standards, 2011).

Risks at developmental stages

Threats to safety are influenced by a person’s developmental stage, lifestyle, mobility status, sensory impairments and safety awareness.

Infant, toddler and preschooler

Injuries are the leading cause of death and hospitalisation in children over 1 year old (City of Greater Dandenong, 2007). The nature of the injury sustained is closely related to normal growth and development. For example, the incidence of poisoning is highest in late infancy and toddlerhood because of the increased level of oral activity and the growing ability to explore the environment. Accidents involving children are largely preventable, but parents need to be aware of specific dangers at each stage of growth and development. Accident prevention thus requires health education for parents and the removal of dangers whenever possible. Drowning is a case in point—health promotion in the form of television advertisements, council by-laws about pool fencing and parental education are working towards decreasing the number of toddlers who drown annually in Australia. Health promotional activities such as these have a positive impact on the number of injury-related deaths to children (Australian Bureau of Statistics, 2006).

School-age child

When a child enters school, the environment expands to include the school, transport to and from school, school friends and after-school activities. Through discussions using examples, parents, teachers and nurses must instruct the child in safe practices to follow at school or play.

Because school-age children are participating in more activities outside their home and neighbourhood environments, they are at greater risk of injury from strangers. Therefore children should be warned repeatedly not to accept sweets, food, gifts or rides from strangers. In addition, children need to know what to do if a stranger approaches. Some neighbourhoods have a ‘safe house’. In these homes the owner ensures that an adult is home during the times when children are walking to and from school. If a stranger approaches a child, the child can run to that home, and the adult will protect the child and call the proper authorities. Nurses can work with school systems or neighbourhoods to initiate such a system to protect children.

Safety is stressed in school sports, but parents and healthcare professionals can reinforce these safety tips by insisting that children wear protective gear while participating in sports. For example, schools provide hard batting helmets for cricket games, and parents should also provide this equipment when children are playing cricket in their own backyards.

Bicycle-related injuries are a cause of death and disability among children. Bikes should be in good working order and be the proper size for the child. Children should be taught the rules of the road and cautioned not to engage in dangerous stunts or activities while bike riding. A properly fitted helmet must be worn. Since the introduction of mandatory bicycle-helmet-wearing legislation in 1990, the severity and incidence of head and brain injuries has declined (Macpherson and Spinks, 2007) (Figure 15-3).

Adolescent

As children enter adolescence, they develop greater independence and begin to develop a sense of identity and their own values. In addition, adolescents begin to separate emotionally from their families, and peers generally have a stronger influence.

The struggle towards identity may cause teenagers to experience shyness, fear and anxiety, with resulting dysfunction at home or school. In an attempt to relieve the tensions associated with the physical and psychosocial changes, as well as peer pressure, adolescents may begin smoking and using drugs. In addition to the health risks posed by nicotine and other drugs, the ingestion of drugs, including alcohol, increases the incidence of drowning and motor vehicle accidents.

When adolescents learn to drive, their environment expands and so does their potential for injury. Young drivers must be taught to comply with rules and regulations regarding the use of a car. Common rules include proper use of seatbelts and abstinence from alcohol and other drugs.

Because adolescence is a time when mature sexual physical characteristics develop, adolescents may begin to have physical relationships. It is important that they have access to relevant information regarding abstinence, safe sexual practices and birth control.

Adult

The threats to an adult’s safety are often related to lifestyle habits and occupation. For example, people who use alcohol excessively are at greater risk of motor vehicle accidents. Long-term smokers have a greater risk of cardiovascular or pulmonary disease as a result of the inhalation of smoke into the lungs and the effect of nicotine on the circulatory system. Similarly, adults experiencing a high level of stress are more likely to have an accident or an illness such as headaches, gastrointestinal disorders and infections (see Chapter 42).

Older adult

The physiological changes that occur during the ageing process increase a person’s risk of falls and other types of accidents such as burns and car accidents (Box 15-3). Older people are more likely to fall in the garden, a public area, the living room or on steps. Most falls occur when the person is ‘just walking’, engaging in household chores or gardening (Mackenzie and others, 2002). Box 15-4 presents a health and lifestyle checklist for identifying the potential for falls and other accidents.

BOX 15-3 PHYSICAL ASSESSMENT FINDINGS IN THE OLDER ADULT THAT INCREASE THE INCIDENCE OF ACCIDENTS

MUSCULOSKELETAL CHANGES

Muscle strength and function decrease, joints become less mobile, posture changes (some kyphosis is common) and range of motion is limited.

NERVOUS SYSTEM CHANGES

All voluntary or automatic reflexes slow to some extent, ability to respond to multiple stimuli decreases and proprioception decreases.

SENSORY CHANGES

Peripheral vision and lens accommodation decrease, lens may develop opacity (cataracts), stimuli threshold for light touch and pain increases, transmission of hot and cold impulses is delayed and hearing is impaired as high-frequency tones become less perceptible.

GENITOURINARY CHANGES

Nocturia, increased frequency of urination and occurrences of incontinence increase.

Modified from Ebersole P and others 2004 Toward healthy aging: human needs and nursing response, ed 6. St Louis, Mosby.

BOX 15-4 HEALTH AND LIFESTYLE CHECKLIST FOR IDENTIFYING FALLS POTENTIAL

CALCIUM, VITAMIN D AND WATER

• Do you eat three healthy meals per day?

• Do you eat at least 3–4 serves of high calcium foods (milk, yoghurt, cheese, almonds or salmon) per day?

• Do you spend a little bit of time in the sun? (6–8 minutes, 4–6 times per week, is plenty.)

• Do you drink 4–6 glasses of water (or other fluids) per day?

From NSW Health 2010 Staying active and on your feet. Sydney, NSW Health. Online. Available at www.activeandhealthy.nsw.gov.au/assets/pdf/stayactive_web_final.pdf 28 Jun 2012.

Individual risk factors

Other risk factors posing threats to safety include lifestyle, impaired mobility, sensory or communication impairment and lack of safety awareness.

Lifestyle

Lifestyle can increase risks. People who drive or operate machinery while under the influence of chemical substances, who work at inherently dangerous jobs or who are risk-takers are at greater risk of injury. In addition, people experiencing stress, anxiety, fatigue, alcohol or drug withdrawal or those taking prescription medications may be more accident-prone. Because of these factors, people may be too preoccupied to notice the source of potential accidents, such as cluttered stairs or a stop sign.

Impaired mobility

Impaired mobility due to muscle weakness, paralysis, or poor coordination or balance is a major factor in falls. Immobilisation predisposes the person to additional physiological and emotional hazards, which in turn can further restrict mobility and independence.

Sensory or communication impairment

People with visual, hearing, tactile or communication impairment, such as aphasia or a language barrier, are at greater risk of injury. Such people may not be able to perceive a potential danger or express their need for assistance.

Lack of safety awareness

Some people are unaware of safety precautions, such as keeping medicine away from children or reading the expiration date on food products. A complete nursing assessment, including a home inspection (see Box 15-2), should help the nurse to identify a person’s level of knowledge regarding home safety so that deficiencies can be corrected with an individualised nursing care plan.

Risks in the healthcare agency

The issues related to the patient’s environmental safety in terms of basic needs, reduction of physical hazards, reduction of transmission of pathogens and pollution control apply to the healthcare agency as well as to the home and community. However, there are specific risks in healthcare agencies that must also be minimised.

Improving patient safety has been of great significance across the Australian health system for more than a decade. Establishment of the Australian Council on Safety and Quality in Healthcare in 2000 has been an important initiative, as focus has been placed on identified key areas of concern and strategies developed and implemented to address them. Hence, minimisation of these risks, the process of which is commonly referred to within healthcare institutions as clinical governance, are of increasing importance for Australian healthcare facilities. The actions required to minimise and manage such risks are governed by the Australian Safety and Quality Framework for Healthcare (Australian Council on Safety and Quality in Healthcare, 2010) and the Australian Council on Healthcare Standards who define clinical governance as ‘the system by which the governing body, managers and clinicians share responsibility and are held accountable for patient care, minimising risks to consumers and for continuously monitoring and improving the quality of clinical care’ (Australian Council on Healthcare Standards, 2004).

The types of risks within the healthcare environment are primarily those relating to falls, patient-inherent accidents, procedure-related accidents and equipment-related accidents, but also include hazards caused by obstacles and the lack of adherence to the safe administration and monitoring of oxygen therapy, as has been identified earlier in this chapter. The nurse must assess for these potential problem areas and, considering the developmental level of the patient, take steps to prevent or minimise accidents in the agency.

An accident necessitates the filing of an incident report, a confidential document that completely describes any patient accident occurring on the premises of a healthcare agency. It documents the accident, patient assessment and interventions carried out for the patient. In addition to completing the incident report, the nurse must objectively document the incident in the patient’s medical record. These reports are used by the hospital to establish protocols and practice that provide a safe environment for staff and patients.

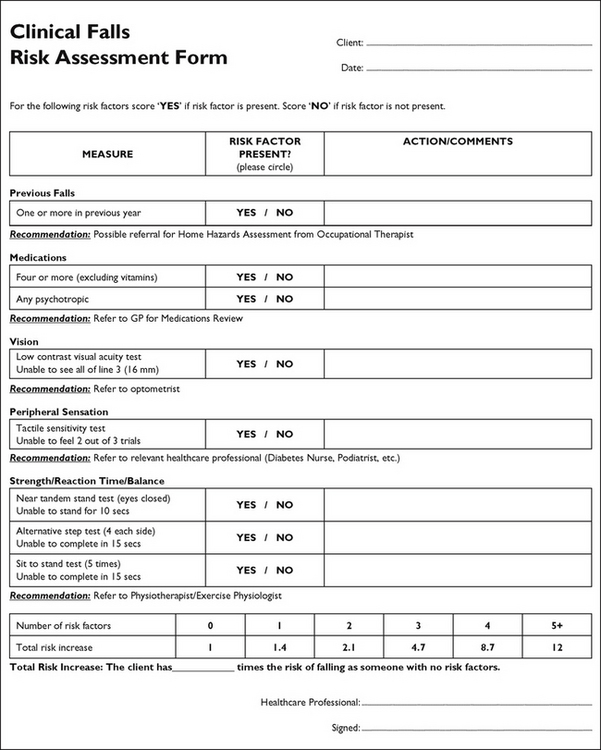

Falls

Falls account for a large proportion of reported incidents in hospitals. In addition to age, a history of previous falls, gait, balance and mobility problems, postural hypotension, sensory impairment, urinary and bladder dysfunction and certain medical diagnostic categories (e.g. cancer and cardiovascular, neurological and cerebrovascular diseases) increase the risk. Drug use and drug interactions are also implicated in falls (Box 15-3). In older people, the fear of falling may be so great that they significantly reduce their activities (Yardley and Smith, 2002) (Figure 15-4).

Patient-inherent accidents

Patient-inherent accidents are accidents (other than falls) in which the patient is the main factor. Examples of patient-inherent accidents are self-inflicted cuts, injuries and burns; ingestion or injection of foreign substances; self-mutilation or fire-setting; and pinching fingers in drawers or doors.

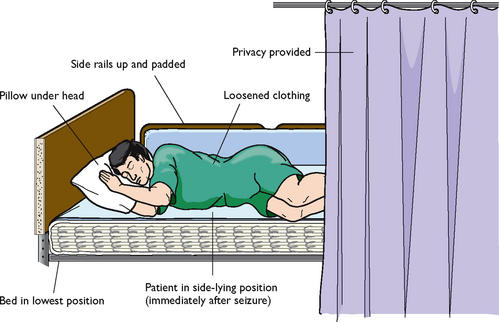

A patient-inherent accident may occur as a result of a seizure. A seizure is a hyper-excitation and disorderly discharge of neurons in the brain, leading to a sudden, violent, involuntary series of muscle contractions that may be paroxysmal and episodic, as in a seizure disorder, or transient and acute, such as following a head injury. A generalised tonic–clonic, or grand mal, seizure lasts approximately 2 minutes (no longer than 5). Before a convulsive episode, a few people may report an aura, which serves as a warning or sense that a seizure is about to occur. An aura may be a bright light, smell or taste. During the seizure the person may have shallow breathing, cyanosis and possibly loss of bladder and bowel control. Following the seizure there is a postictal phase during which the person may have amnesia or confusion and may fall into a deep sleep.

Seizures that last 15 minutes or longer, or a series of seizures over a 20- to 30-minute period in which the person does not regain consciousness between attacks, is known as status epilepticus. This condition is a medical emergency and requires intensive monitoring and treatment. It is important for the nurse to observe the patient carefully before, during and after the seizure so that the episode can be documented accurately.

PROCEDURE-RELATED ACCIDENTS

Procedure-related accidents occur during therapy. They can include medication and fluid administration errors, improper application of external devices and incidents related to improper performance of procedures (e.g. Foley catheter insertion).

Many procedure-related incidents can be prevented by adherence to accurate nursing principles and practice. For example, strictly following the procedure for administering medications will prevent medication errors. Proper administration of intravenous (IV) fluids prevents fluid overload or deficit. The potential for infection is reduced when the principles of asepsis are used for sterile dressing changes or any invasive procedure. Finally, correct use of body mechanics, equipment and transfer techniques reduces the risk of injuries when moving and lifting patients (Worksafe, 2000).

EQUIPMENT-RELATED INCIDENTS

Equipment-related incidents result from the malfunction, disrepair or misuse of equipment or from an electrical hazard. To avoid injury, nurses should not operate monitoring or therapy equipment without instruction.

A checklist should be used to assess potential electrical hazards to reduce the risk of electrical fires, electrocution or injury from faulty equipment (see Box 15-2). In healthcare settings, the engineering staff make regular safety checks of equipment.

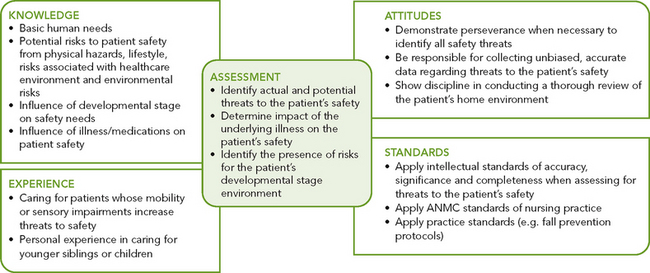

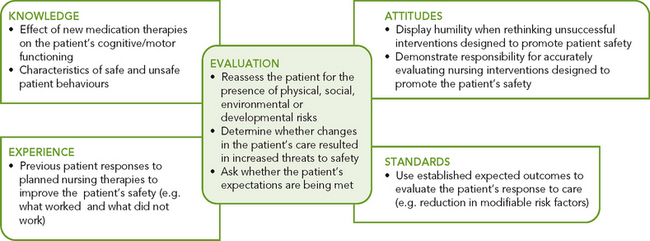

Critical thinking synthesis

Successful critical thinking requires a synthesis of knowledge, experience, information gathered from patients, critical-thinking attitudes and intellectual and professional standards. Clinical judgments require the nurse to anticipate the necessary information, analyse the data and make decisions regarding patient care. Critical thinking is always changing. During assessment (Figure 15-5), it is imperative that nurses consider all assessment data critically, as well as information about the specific patient, to identify accurately the patient’s problems and make appropriate decisions affecting their treatment and care.

In the case of providing safe and high-quality care, the nurse integrates knowledge from nursing and other scientific disciplines, previous experiences in caring for patients who had an injury or were at risk, critical-thinking attitudes such as perseverance, and any standards of practice that are applicable. For example, the Nursing and Midwifery Board of Australia (NMBA) National competency standards for the registered nurse (Australian Nursing and Midwifery Council, 2006, adopted by NMBA in 2010), discuss the nurse’s responsibility in maintaining patient safety. The Australian Council on Healthcare Standards (2004) also provides standards for safety (e.g. in the administration of medications, use of restraints and use of medical devices). All this information and experience is referred to by nurses as they conduct a detailed and focused assessment of a specific patient. For example, while assessing a specific patient’s home environment, the nurse will consider knowledge regarding typical locations within the home where dangers commonly exist. If a patient has a visual impairment, the nurse will apply previous experiences in caring for patients with visual changes to anticipate how to thoroughly assess the patient’s needs. Critical thinking directs the nurse to anticipate what needs to be assessed and how to make conclusions about available data.

Mr Alexopoulos, who is 88 years old, lives alone. In the past year he has fallen twice at home, once by tripping over a rug and once when he got up to go to the bathroom at night. He has become increasingly afraid of falling again and tends to restrict his activities in the home. He goes out only when accompanied by his son.

SAFETY AND THE NURSING PROCESS

ASSESSMENT

To conduct a comprehensive and focused patient assessment, possible threats to the patient’s safety, including the patient’s immediate environment as well as any individual risk factors, must be considered. When caring for a patient in the home, a home hazard assessment is necessary (see Box 15-2). A walk through the home with the patient should be undertaken, and a discussion between nurse and person on how the person normally conducts daily activities should establish the person’s immediate needs. Getting a sense of the person’s routines helps the nurse recognise hazards that may not be obvious. For example, if a person typically uses a stool to reach items in the kitchen, the nurse can anticipate the need to assess the risk of falls. Including the family in the assessment may also help reveal hazards or risks.

When the patient is cared for within a healthcare facility, the nurse must determine if any hazards exist in the immediate care environment. Does the placement of equipment or furniture pose barriers when the patient tries to walk? Does positioning of the bed allow the patient to reach items on a bedside table or stand? In what way are self-care items in a bathroom arranged for accessibility? The nurse also collaborates with clinical engineering staff to make sure that equipment has been assessed to ensure proper function and condition.

A nursing history will include data about the patient’s level of wellness to determine if any underlying conditions exist that pose threats to safety. For example, the nurse will give special attention to assessing gait, muscle strength and coordination, balance and vision. A review of the patient’s developmental status must be considered as assessment information is analysed. The nurse will also review whether the patient is taking any medications or undergoing any procedures that pose risks. For example, use of diuretics increases the frequency of voiding and may result in the patient having to use toilet facilities more often. Falls often occur with patients who must get out of bed quickly because of urinary urgency.

Patient expectations

Patients generally expect to be safe in their home and in the healthcare setting. However, there are times when a patient’s view of what is safe does not agree with that of the nurse. For this reason, any assessment must include the patient’s perception of risk factors. This will be important later as the nurse attempts to make changes in the patient’s environment. People usually do not purposefully put themselves in jeopardy. When people are uninformed or inexperienced, threats to their safety can occur. People must always be consulted on ways to reduce hazards in their environment.

NURSING DIAGNOSIS

After completing an assessment of the patient’s safety status, the nurse reviews any clusters of data showing patterns suggesting that safety is threatened. Identification of defining characteristics from the data, including cultural aspects, directs the nurse in identifying appropriate nursing diagnoses (Box 15-5).

The diagnostic process requires accurate recognition of defining characteristics, as well as the related factors (Box 15-6). The related factor becomes the basis for selecting nursing therapies. For example, risk of injury related to impaired mobility and risk of injury related to barriers in the home environment require different nursing interventions. The patient with altered mobility may require walking aids and physical therapy. When the related factor is barriers in the home, the nurse intervenes to make changes that will create a safer environment. At times, multiple related factors may apply.

BOX 15-6 SAMPLE NURSING DIAGNOSTIC PROCESS

| RISK OF INJURY | ||

|---|---|---|

| ASSESSMENT ACTIVITIES | DEFINING CHARACTERISTICS | NURSING DIAGNOSIS |

| Observe patient’s mobility | Risk of injury related to impaired mobility, decreased vision, poorly lighted home and cluttered environment | |

| Ask patient about visual acuity | ||

| Complete a home hazard appraisal | ||

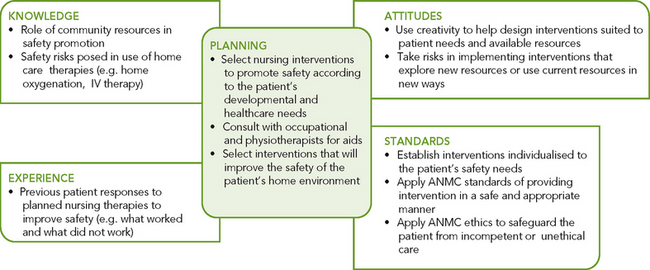

PLANNING

During planning, the nurse critically synthesises information from multiple sources (Figure 15-6). Critical thinking ensures that the patient’s plan of care integrates all that the nurse has learned about the patient, as well as the key critical-thinking elements. For example, nurses will reflect on their knowledge of services that allied health disciplines (e.g. occupational therapy) can provide in helping patients return to their home environments safely. The nurse will also reflect on any previous experience whereby a patient benefited from safety interventions. Such experience helps the nurse adapt approaches to a new patient. Applying critical-thinking attitudes such as creativity helps the nurse and patient collaborate in planning interventions that are relevant and most useful, particularly when changes are made in the home environment (see Sample nursing care plan).

Goals and outcomes

Planning and goal-setting need to be done with the patient, family and other members of the healthcare team (see Sample nursing care plan). Expected outcomes must be measurable and realistic. The following are common goals that focus on the patient’s need for safety:

• Modifiable hazards will be reduced in the home environment.

• Patient will identify and avoid risks within the home and community.

The patient who is an active participant in reducing threats to safety will be more alert to potential hazards. Patients need to learn how to identify and select resources within their community that enhance safety (e.g. neighbourhood ‘safe houses’, local police stations and neighbours willing to check on a person’s wellbeing). There will be many outcomes—for example, for reducing modifiable risk factors in the home, scatter rugs can be tacked down, frayed cords repaired, safety latches attached to cupboard doors, and so on.

The overall goal for a person with a threat to safety is remaining free from injury. Nursing interventions are designed to provide safe and efficient care.

Priority setting

The nurse plans individualised interventions based on the severity of risk factors and the patient’s developmental stage, level of health, lifestyle and culture (see Working with diversity).

Continuity of care

Collaboration with other disciplines such as occupational therapy and physiotherapy may become an important part of the plan of care. Planning also involves an understanding of the patient’s need to maintain independence within physical and cognitive capabilities. The nurse and patient collaborate to establish ways of maintaining the patient’s active involvement within the home and healthcare environment. Education of the patient and family is another important intervention to reduce safety risks over the long term.

WORKING WITH DIVERSITY FOCUS ON CULTURAL CARE

When conducting home assessments for risks to safety, nurses must realise that they have entered the patients’ territory and that the patients’ attitudes towards their residence and belongings must be appreciated. It may be very difficult for people to have an outsider in their home who is suggesting changes with regard to their personal belongings to reduce physical hazards.

Planning and prioritising healthcare with clients from culturally and linguistically diverse backgrounds (abbreviated either to CALD or CADLB) can raise issues of safety and equity, whether in the community or the acute-care health agency. It is particularly difficult to determine patients’ requirements in relation to healthcare and their attitudes towards safe practices in their home when another language is spoken. The nurse should use an interpreter, or engage the family to interpret if available. Attentiveness to patients’ non-verbal communication becomes extremely important (Blackford, 2005).

Another culturally sensitive issue is patients’ sense of environmental control. Nurses must be aware of health beliefs and practices that will affect the outcome of interventions. For example, reliance on family and religious organisations, as opposed to community resources, may affect patients’ compliance with nursing interventions and referrals.

RISK OF INJURY

ASSESSMENT*

Mr Key, a visiting nurse, is seeing Mrs Cohen, an 85-year-old woman, at home. The patient has been recovering from a mild stroke. On physical examination, Mr Key finds Mrs Cohen’s blood pressure to be 122/78 mmHg with a pulse of 84 beats per minute and regular. Mrs Cohen lives alone but receives regular assistance from her daughter, a schoolteacher. Her son also lives in town and helps when needed. Mrs Cohen has a marked kyphosis and an uncoordinated, hesitant gait. She also has a slight weakness of her left arm and leg as a result of her stroke. Mr Key’s assessment also reveals that Mrs Cohen has trouble reading and seeing objects at a distance. Her last eye examination was 18 months ago, when she received a prescription for glasses. Although she has no history of falling, she notes that since returning home from the hospital, ‘I bump into things, and I am so afraid I am going to fall.’ She shows Mr Key the bruises on her left leg and thigh. As Mr Key completes a home hazard assessment, he finds Mrs Cohen’s home cluttered with furniture and small objects, such as planters and magazines. Cabinets in the kitchen are in disarray and full of breakable items that could fall out. Several throw rugs are seen throughout the house. The bathroom is poorly lit and does not have safety strips in the bath or grab bars.

NURSING DIAGNOSIS: Risk of injury related to impaired mobility, decreased visual acuity and physical environmental hazards.

PLANNING

| GOALS | EXPECTED OUTCOMES |

|---|---|

| Home will be free of hazards within 1 week. | Modifiable hazards will be reduced in the home within 1 week. |

| Patient and family will know about potential hazards for Mrs Cohen’s age group within 1 week. | Patient and daughter will identify risks and the steps to avoid them in the home at the conclusion of a teaching session. |

| Patient will express greater sense of feeling safe from falls in 1 month. | Patient will be able to see objects at a distance clearly while wearing glasses. |

| Patient will be free of injury. | Patient will be able to walk unencumbered throughout the home within 2 weeks. |

| INTERVENTIONS† | RATIONALE |

|---|---|

| Fall prevention | |

| Fall risks for homebound older adults include deteriorating eyesight, alterations to posture, unsteady gait, history of falls and effect of medication (Linton and Lach, 2006). | |

| Environmental factors may need modification for safety. | |

| With ageing, the pupil loses the ability to adjust to light, causing sensitivity to glare. Glare can prevent a person from seeing a path clearly. | |

| Fear of falling causes people to stiffen their posture which increases risk of falls. Education regarding hazards improves confidence and reduces falls. | |

| Enhanced vision reduces incidence of falls. | |

| Exercise program increases muscle strength, gait and balance. Increasing lower extremity strength reduces falls risk. Tai chi can improve balance (Linton and Lach, 2006). | |

†Intervention classification labels from McCloskey JC, Bulechek GM 2000 Nursing interventions classification (NIC), ed 3. St Louis, Mosby.

*Defining characteristics are shown in bold type.

Research focus

Minimisation of adverse events for inpatients — millions of healthcare dollars together with extended hospitalisation stays are often the consequence of adverse events suffered by patients as a result of medical treatment when hospitalised. This global challenge is one continually faced by clinicians and hospital management.

Research abstract

This exploratory study tested the hypothesis that a reduction in adverse events could be achieved if patients were to be involved in scrutinising their care.

The aim and objectives of the study were to explore:

1. surgical patients’ willingness to question healthcare staff about their treatment

2. differences between patients’ willingness to ask factual vs challenging questions related to the quality and safety of their healthcare

3. patient demographic characteristics that could affect patients’ willingness to ask questions; and

4. the impact of doctors’ instructions on patients’ willingness to ask questions.

This was a cross-sectional study set in an inner-city teaching hospital in London and used a Patient Willingness to Ask Safety Questions Survey to survey a convenience sample of 80 patients postoperatively. The survey questions conformed to contemporary patient safety initiatives aimed at engaging patients to ask healthcare staff specific safety-related questions about their healthcare. The survey also included factual questions (e.g. ‘When can I return to my normal activities?’) and challenging questions (e.g. ‘Have you washed your hands?’), and examined the impact of doctors’ instructions on patients’ willingness to ask challenging questions (e.g. ‘If instructed to by a doctor, would you be willing to ask “Have you washed your hands?”?‘).

The findings of the survey were that surgical patients were significantly more willing to:

• ask doctors factual rather than challenging questions

• ask nurses factual rather than challenging questions

Doctors’ instructions to the patient increased patients’ willingness to challenge doctors and nurses. Educated female patients and patients in employment were more willing to engage and ask questions. The study concluded that surgical patients, particularly men, less educated or unemployed were less prepared to engage and challenge clinical staff regarding their care and were unwilling to question clinical staff using factual questions.

IMPLEMENTATION

Nursing interventions are directed towards maintaining the patient’s safety in all types of settings. Nursing measures for providing a safe environment include health promotion, developmental interventions and environmental interventions. Each of these areas of implementation is appropriate for acute and restorative care settings.

Health promotion

To promote an individual’s health, it is necessary for the individual to be in a safe environment and to practise a lifestyle that minimises risk of injury. A comprehensive approach to health promotion involves, for example, the government (traffic and alcohol laws), the community (drug and alcohol education) and the individual (not driving under the influence of alcohol) (Howat and others, 2004).

Nurses participate by supporting legislation and working in community-based settings. Because environmental and community values have the greatest influence on health promotion, community and home health nurses can assess and recommend safety measures in the home, school, neighbourhood and workplace.

Developmental interventions

INFANT, TODDLER AND PRESCHOOLER

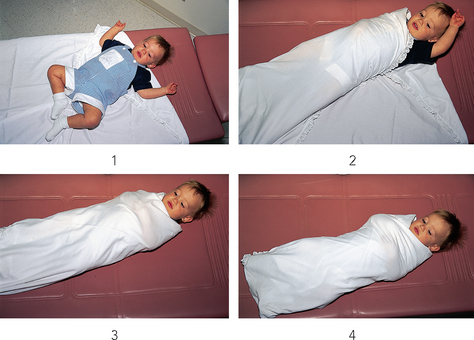

Infants, toddlers and preschoolers depend on adults to protect them from injury. Growing children are curious and completely trusting of their environment and do not perceive themselves to be in danger. Nurses are often in a position to educate parents or guardians about reducing risks of injuries to young children (see Chapter 20). Nurses and midwives working in antenatal and postpartum settings can easily incorporate safety into the care plan of the family. Community health nurses can assess the home and show parents how to promote safety in their homes (Table 15-1 and Figures 15-7 and 15-8).

TABLE 15-1 PROMOTING SAFETY FOR CHILDREN AND ADOLESCENTS

| INTERVENTION | RATIONALE |

|---|---|

| INFANTS AND TODDLERS | |

| Have infants sleep on their backs or sides | Sleeping on the stomach with the mouth and nose in close proximity to the mattress is associated with sudden infant death syndrome (SIDS) |

| Do not fill cots with pillows, large stuffed toys or comforters. Sheets should fit snugly | Infants may become entwined in sheets and other bedding and suffocate |

| Dummies should not be attached to string or ribbon and placed around a child’s neck | Choking may occur |

| All instructions for preparing and storing formula must be followed |

Proper formula preparation and storage prevents contamination A formula may come in a concentrated form, or it may already be diluted and ready to use. Following directions ensures proper concentration of the formula. Undiluted formula can cause fluid and electrolyte disturbances; very diluted formula will not provide sufficient nutrients |

| Use large, soft toys without small parts, such as buttons | Small parts can become dislodged, and choking and aspiration may occur |

| Playpens with mesh sides should not be left with a side down; spaces between cot slats should be less than 6 cm apart | A child’s head may become wedged in the lowered mesh side or between cot slats, and asphyxiation may occur |

| Never leave cot sides down or leave babies unattended on changing tables or in infant seats, walkers, swings, strollers or highchairs | Infants and toddlers can roll or move and fall from changing tables or out of accessories such as infant seats or walkers |

| Discontinue using accessories such as infant seats, walkers and swings when the child becomes too active, physically too big and/or according to the manufacturer’s directions | When physically active or too big, the child can fall out of or tip over these accessories and suffer an injury |

| Never leave a child alone in the bathroom, bath or near any water source (e.g. pool) | Accidental drowning may occur |

| Baby-proof the home, removing small or sharp objects and toxic or poisonous substances, including plants | Babies explore their world with their hands and mouth. Choking and poisoning may occur |

| Remove plastic bags from the home | Suffocation may occur if plastic covers the nose and mouth |

| Electrical outlets should have covers (see Figure 15-7) | Crawling babies may insert objects into outlets and experience an electrical shock |

| Do not use tablecloths; turn handles of pots/kettles towards centre of stove | Reduces likelihood that children will pull pot contents onto themselves |

| Window guards should be on all windows | This prevents children from falling out of windows |

| Install keyless locks (e.g. bolts) on doors above a child’s reach, even when they are standing on a chair | This prevents a toddler from leaving the house and wandering off. Death from exposure, car accidents and drowning may occur. Keyless locks allow for rapid exit in case of fire |

| In motor vehicles, all people must use appropriate restraints, properly adjusted and fastened. In Australia, children under 4 years of age must use approved child restraints of the correct size (rearward-facing for those under 6 months); children aged 4–7 years must use an approved restraint or booster seat. | In case of a sudden stop or crash, an unrestrained child may suffer severe head injuries and death |

| Caregivers should learn CPR | Caregivers should be prepared to intervene in acute emergencies |

| PRESCHOOLERS | |

| Teach children to swim at an early age, but always provide supervision near water | Learning to swim is a useful skill that may some day save a child’s life. However, all children need constant supervision near water |

| Teach children how to cross streets and walk in parking lots. Instruct them never to run out after a ball or toy | Pedestrian accidents involving young children are common |

| Teach children not to talk to, go with or accept any item from a stranger | This reduces the risk of injury and abduction |

| Teach children basic physical safety rules, such as proper use of scissors, never running with an object in their mouth or hand and never attempting to use the stove or oven unassisted | Risk of injury is lowered if children are taught basic safety procedures |

| Teach children not to eat items found in the street | Poisoning may occur |

| Remove doors from unused refrigerators and freezers. Instruct children not to play or hide in a car boot or unused appliances | If a child cannot freely exit from appliances and car boots, asphyxiation may occur |

| SCHOOL-AGE CHILDREN | |

| Teach children the safe use of equipment for play and work | The child needs to learn the safe, appropriate use of implements to avoid injury |

| Teach children proper bicycle safety, including use of helmets and rules of the road | This may reduce injuries from falling off a bike or being hit by a car |

| Teach children proper techniques for specific sports, as well as the need to wear proper safety gear | Using proper sports techniques, correct equipment and protective gear prevents injuries |

| Teach children not to operate electrical equipment while unsupervised | If an electrical mishap were to occur, no one would be available to help |

| Children should never have access to firearms or other weapons | Children are often fascinated by firearms and weapons and may attempt to play with them |

| ADOLESCENTS | |

| Encourage enrolment in driver’s education classes | Many injuries in this age group are related to motor vehicle accidents |

| Provide information about the effects of using alcohol and drugs | Adolescents are prone to risk-taking behaviours and are subject to peer pressure |

| Provide sex education, emphasising safe sex practices, including abstinence | Many adolescents begin sexual relationships. Pregnancy and sexually transmitted diseases may result |

| Refer adolescents to community and school-sponsored activities | The adolescent needs to socialise with peers, yet needs some supervision |

| Encourage mentoring relationships between adults and adolescents | Adolescents need role models on whom they can pattern their behaviour |

Modified from Hockenberry MJ and others 2010 Wong’s nursing care of infants and children, ed 9. St Louis, Mosby.

SCHOOL-AGE CHILD

School-age children increasingly explore their environment (see Chapter 20). They have friends outside their immediate neighbourhood, and they become more active in school, church and sporting activities. School-age children need specific teaching regarding safety in school and at play (see Figure 15-3). See Table 15-1 for nursing interventions to help guide parents in providing for the safety of school-age children.

ADOLESCENT

Risks to the safety of adolescents involve many factors outside the home environment, particularly their almost constant involvement with members of their peer group (see Chapter 20). Adults serve as role models for adolescents and, through example, expectations and education can help adolescents minimise risks to their safety. This age group has a high incidence of suicide because of feelings of decreased self-worth and hopelessness. The nurse must be aware of the risks posed at this time and be prepared to teach adolescents and their parents measures to prevent accidents and injury (see Table 15-1).

ADULT

Risks to young and middle-aged adults often result from lifestyle factors such as child-rearing, high stress levels, inadequate nutrition, excessive alcohol intake, and substance abuse (see Chapter 21). In today’s fast-paced society there also appears to be more expression of anger, which can quickly precipitate accidents (e.g. road rage). Adults need to have the opportunity to discuss the choices they have made in their lifestyle and the types of threats to safety that exist. Given information about threats to their wellbeing, adults may make necessary modifications to their lifestyle. Useful resources are stress management centres (see Chapter 42) and health promotion activities, which can be found in many community service programs and hospitals. In addition, neighbourhood centres, community clinics and outpatient clinics are equipped to help adults modify lifestyle habits that present risks to health (e.g. smoking, overeating, lack of exercise and alcoholism).

OLDER ADULT

Nursing interventions for older adults are designed to reduce the risk of falls and other accidents and to compensate for the physiological changes of ageing. Most injuries to older adults involve falls, car accidents and burns (Australian Bureau of Statistics, 2006). Advancing age and the concurrent physiological changes in vision, hearing, mobility, reflexes, circulation and the ability to make quick judgments all predispose older adults to falls (see Chapter 22). Certain disease states common to older adults, such as arthritis or cerebrovascular accidents, increase the chance of injury. In addition, the effects of many medications given to older adults, such as sedatives, diuretics and laxatives, make falls more likely.

Older adults are more likely to have car accidents because of:

1. deficits in visual acuity affecting depth perception and peripheral vision

2. hearing loss affecting the older adult’s ability to hear emergency vehicle sirens and car horns, and

3. decreased cognitive and neurological responses affecting their ability to react quickly to avoid an accident (Linton and Lach, 2006).

A decline in these skills may account for the most common types of accidents, including right-of-way and turning accidents. The nurse can advise patients regarding safe driving tips (e.g. driving shorter distances or only in daylight, using side and rear-view mirrors carefully and looking behind them towards their ‘blind spot’ before changing lanes). If any sensory loss is detected, the nurse may refer the patient to a specialist for appropriate advice on safe driving. Eventually, counselling may be necessary to help patients make the decision about when to stop driving. At that time, the nurse should help locate resources in the community that provide transport.

Burns and scalds are also more apt to occur with older people because they may forget and leave hot water running or become confused when turning the dials on a stove or other heating appliance. Nursing measures for preventing burns are designed to minimise the risk from impaired vision. Hot water taps and dials can be colour-coded to make it easier for the person to know what has been turned on. Recommending a reduction in temperature of the water heater can also be very beneficial.

Older adults love to walk. Pedestrian accidents can be reduced for older adults and for all other age groups by persuading people to wear reflectors on garments when walking at night; to walk where there are footpaths; to stand on the footpath and not in the street when waiting to cross a street; to always cross at corners or pedestrian crossings and not in the middle of the block (particularly if the street is a major one); to cross with the traffic light and not against it; and to look right, left and right again before crossing the street.

Environmental interventions

Nursing interventions directed at eliminating environmental threats include general preventive measures such as meeting basic needs, reducing physical hazards and reducing pathogen transmission. They also deal with specific safety concerns.

GENERAL PREVENTIVE MEASURES

Nurses can contribute to a safer environment by helping the patient meet basic needs related to oxygen, nutrition, temperature and humidity. To ensure that oxygen availability is not threatened, the nurse might recommend that the patient has a gas heater periodically inspected for proper functioning. To achieve a comfortable level of humidity in the home, the patient might use a humidifier or, in the case of patients with upper respiratory tract infections, a room humidifier where they sleep. The nurse can teach basic techniques of food handling (e.g. hand-washing, checking for spoilage) and preparation (e.g. keeping food refrigerated before serving) so that nutritional needs are met safely. Education for older adults or people who enjoy outdoor activities should include ways to prevent and treat hypothermia, heatstroke and heat exhaustion (see Chapter 22).

Adequate lighting and security measures in and around the home, including the use of night-lights, exterior lighting, and locks on windows and doors, enable people to reduce the risk of injury from crime. The local police department and community organisations often have safety classes available for residents to learn how to take precautions to minimise the chance of becoming involved in a crime. For example, some useful tips include always parking the car near a bright light or busy public area, carrying a whistle attached to the car keys and checking to see if anyone follows the car.

To prevent the transmission of pathogens, nurses can teach aseptic practices. Medical asepsis, which includes hand-washing and environmental cleanliness, reduces the transfer of organisms (see Chapter 29). Patients and family members need to learn thorough hand-washing and when to use it (e.g. before and after caring for a family member, before food preparation, before preparing a medication for a family member and after contacting any body fluids). When patients require dressing changes or the use of syringes and needles, families should be shown how to properly dispose of contaminated items.

SPECIFIC SAFETY CONCERNS

The nurse takes measures to help patients avoid falls, injuries from use of restraints and side rails, fires, poisoning and electrical hazards. Special precautions are necessary to prevent injury in patients susceptible to seizures. Radiation injuries are also a specific safety concern.

FALLS

Modifications in the home and healthcare environment can easily reduce the risk of falls (Table 15-2). A heavy or debilitated patient in a bed or wheelchair or on a toilet should be properly supported and secured. Side rails are necessary unless a patient is able to freely and easily walk independently. Safety bars on toilets, wheel locks on beds and wheelchairs and call bells are additional safety features in healthcare settings (Figures 15-9 and 15-10). Excess furniture and equipment should be removed, and a weakened patient should wear rubber-soled shoes or slippers for walking or transferring. The nurse should also encourage the removal of clutter from halls, stairs and traffic areas. When patients use aids such as walking sticks, crutches or walkers, it is important to routinely check the condition of rubber tips and the integrity of the aid.

TABLE 15-2 MEASURES TO PREVENT FALLS BY OLDER ADULTS

| MEASURE | RATIONALE |

|---|---|

| STAIRS | |

| Install treads with uniform depth of 22.5 cm and 22.5 cm risers (vertical face of steps) | If stairs are of uniform size, older adults do not have to continually adjust vision |

| Install uniform-textured or plain-coloured surfaces on each tread, and mark edge of tread with contrasting colour | Uniform textures or colour help to decrease vertigo. Marking edge of tread provides obvious visual clue to end of stair |

| Ensure proper lighting of each tread. Block sun or lightbulb glare with translucent shades or screen, or use lower wattage bulbs | Older adults’ vision is unable to adjust quickly to changes in lighting |

| Ensure adequate headroom so that users do not have to duck to negotiate stairs | Sudden changes in head position may result in dizziness |

| Remove protruding objects from staircase walls | Decreased peripheral vision may prevent person from seeing object |

| Maintain outdoor walkways and stairs in good condition and free of holes, cracks and splinters | Decreased visual acuity can prevent person from seeing any structural defect |

| HANDRAILS | |

| Install smooth but slip-resistant handrail at least 5 cm from wall | 5 cm distance allows person to grasp handrail firmly for support |

| Secure handrail firmly so that user’s weight is supported, especially at bottom and top of stairway | Older adults have greatest risk of falling at top and bottom of stairs, because centre of gravity is being shifted and balance is unstable |

| Install grab-rails in bathroom near toilet and bath tub | This enables person to have support while rising from sitting to standing position |

| FLOOR COVERINGS | |

| Ensure that patients wear properly fitting shoes or slippers with non-skid surface | Reduces chances of slipping |

| Secure all carpets, mats and tiles; place non-skid backing under small rugs | Sudden slip may cause dizziness and inability to regain balance |

| ORIENTATION | |

| Place disoriented patients in room near nurses’ station | Provides for more frequent observation on the part of nursing staff |

| Maintain close supervision of confused patients | Confused patients often attempt to wander out of bed or room |

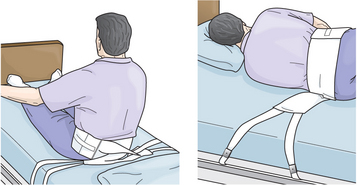

RESTRAINTS

A physical restraint is a device used to immobilise a patient or extremity and to restrict the freedom of movement of, or normal access to, a person’s body. Restraints were commonly used in the past to limit the activity of patients who were confused, combative or at high risk of falling when unattended. However, recent changes in legislation now place more-stringent governance on their use. Assessment and adherence to strict criteria is required before restraints can be applied. An overbed table placed in front of a patient who has difficulty rising from a chair is an example of a restraint. Typical extremity restraints include belts or soft-cloth ties.

Whenever a patient is restrained, there is a natural tendency for the patient to try to remove the restraint. When this occurs, patient injury is common. Complications of physical restraints include nerve and ischaemic injuries, asphyxiation and death (Joanna Briggs Institute, 2002). Patients who are restrained are more likely to fall, have longer hospital stays, acquire a nosocomial infection and die in hospital. The immobility imposed by restraining a patient can lead to pressure ulcer formation, hypostatic pneumonia, constipation, urinary and faecal incontinence and urinary retention (see Chapter 33). Loss of self-esteem, humiliation, fear and anger can also result.