Chapter 26 Sensory alterations

Mastery of content will enable you to:

• Define the key terms listed.

• Differentiate among the processes of reception, perception and reaction to sensory stimuli.

• Discuss the relationship of sensory function to an individual’s level of wellness.

• Discuss common causes and effects of sensory alterations.

• Discuss common sensory changes that normally occur with ageing.

• Identify factors to assess in determining a client’s sensory status.

• Identify nursing diagnoses relevant to clients with sensory alterations.

• Develop a plan of care for clients with visual, auditory, tactile, speech and olfactory deficits.

• List interventions for preventing sensory deprivation and controlling sensory overload.

• Describe conditions in the healthcare agency or client’s home that can be adjusted to promote meaningful sensory stimulation.

• Discuss ways to maintain a safe environment for clients with sensory deficits.

Imagine living without sight, hearing or the ability to feel objects or smell aromas around you. Humans rely on a variety of sensory stimuli to give meaning and order to events in their environment. Stimulation comes from many sources in and outside the body, particularly through the sight (visual), hearing (auditory), touch (tactile), smell (olfactory) and taste (gustatory) senses. The body also has a kinaesthetic sense (proprioception) that enables a person to be aware of the position and movement of body parts without seeing them. Stereognosis is a sense that allows a person to recognise an object’s size, shape and texture. The ability to speak is not considered a sense, but it is similar in that a person without speech may lose the ability to interact meaningfully with other people. Meaningful stimuli allow a person to learn about the environment and are necessary for healthy functioning and normal development. When sensory function is altered, a person’s ability to relate to and function within the environment changes drastically.

Many people seeking healthcare have pre-existing sensory alterations. Others may develop sensory alterations as a result of medical treatment (e.g. hearing loss from antibiotic use). The environment of a healthcare setting (e.g. a noisy intensive-care unit) can cause impact on sensory perception. People who have partial or complete loss of a major sense may have developed, or may need to find, alternative ways to function safely within the environment. If sensory alterations occur early in life, people often have developmental and socialisation problems because of difficulty in responding to other people and the environment. A healthcare setting is often a place of unfamiliar sights, sounds and smells, as well as minimal contact with family and friends. If clients feel depersonalised and are unable to receive meaningful stimuli, serious sensory alterations can develop.

The nurse must understand and help meet the needs of clients with sensory alterations, as well as recognise clients most at risk of developing sensory problems. The nurse helps clients learn to interact and react safely and effectively in their environment.

Scientific knowledge base

Normal sensation

Normally, the nervous system continually receives thousands of signals from sensory nerve organs, relays the information through appropriate channels and integrates the information into a meaningful response. Sensory stimuli reach the sensory organs and can elicit an immediate reaction or present information to the brain to be stored for future use. The nervous system must be intact for sensory stimuli to reach appropriate brain centres and for the individual to perceive the sensation. After interpreting the significance of a sensation, the person can then react to the stimulus. Table 26-1 summarises normal hearing and vision.

TABLE 26-1 NORMAL HEARING AND VISION

Reception, perception and reaction are the three components of any sensory experience (see Chapter 41). Reception begins with stimulation of a nerve cell called a receptor, which usually responds to only one type of stimulus, such as light or sound; it is composed of specific sensory fibres which are sensitive to that particular stimulus (Hickey, 2008). Simply put, when a nerve impulse is created it travels along pathways to the spinal cord or directly to the brain. For example, sound waves stimulate hair-cell receptors within the organ of Corti, which causes impulses to travel along the eighth cranial nerve to the acoustic area of the temporal lobe. Sensory nerve pathways usually cross over to send stimuli to opposite sides of the brain. The actual perception or awareness of unique sensations depends on the receiving region of the cerebral cortex, where specialised brain cells interpret the quality and nature of sensory stimuli. When the person becomes conscious of the stimuli and receives the information, perception takes place. Perception includes integration and interpretation of the stimuli based on the person’s experiences. A person’s level of consciousness influences how well stimuli are perceived and interpreted. Any factors lowering consciousness impair sensory perception. If sensation is incomplete, as with blurred vision, or if past experience is inadequate for understanding stimuli such as pain, the person may react inappropriately to the sensory stimulus.

It is impossible to react to all of the multiple stimuli entering the nervous system. The brain prevents sensory bombardment by discarding or storing sensory information. A person will usually react to stimuli that are most meaningful or significant at the time. After continued reception of the same stimulus, however, a person stops responding and the sensory experience goes unnoticed. For example, a person concentrating on reading a good book may not be aware of music in the background. This adaptability phenomenon occurs with most sensory stimuli except those of pain.

The balance between sensory stimuli entering the brain and those actually reaching a person’s conscious awareness maintains a person’s wellbeing. If a person attempts to react to every stimulus in the environment or if there is insufficient variety and quality of stimuli, sensory alterations will occur.

Sensory Alterations

Many factors change the capacity to receive or perceive sensations (Box 26-1), thus causing sensory alterations. The types of sensory alterations commonly seen by the nurse are sensory deficits, sensory deprivation and sensory overload. When a client suffers from more than one sensory alteration, the ability to function and relate effectively within the environment is seriously impaired.

BOX 26-1 FACTORS THAT INFLUENCE SENSORY FUNCTION

AGE

• Infants are unable to discriminate sensory stimuli. Nerve pathways are immature.

• Visual changes during adulthood include presbyopia (inability to focus on near objects) and the need for glasses for reading (usually occurring between ages 40 and 50 years).

• Hearing changes, which begin at age 30 years, include decreased hearing acuity, speech intelligibility, pitch discrimination and hearing threshold. Tinnitus often accompanies a hearing loss as a side effect of drugs. Older adults hear low-pitched sounds the best but have difficulty hearing conversation over background noise.

• Older adults have reduced visual fields, increased glare sensitivity, impaired night vision, reduced accommodation and depth perception and reduced colour discrimination.

• Older adults have difficulty discriminating the sounds f, s, th and ch. Speech sounds are garbled, and there is a delayed reception and reaction to speech.

• Gustatory and olfactory changes include a decrease in the number of taste buds in later years and reduction of olfactory nerve fibres by age 50. Reduced taste discrimination and reduced sensitivity to odours are common.

• Proprioceptive changes after age 60 years include increased difficulty with balance, spatial orientation and coordination.

• Older adults experience tactile changes, including declining sensitivity to pain, pressure and temperature.

MEDICATIONS

Some antibiotics (e.g. streptomycin, gentamicin) are ototoxic and can permanently damage the auditory nerve; chloramphenicol can irritate the optic nerve. Narcotic analgesics, sedatives and antidepressant medications can alter the perception of stimuli.

ENVIRONMENT

Excessive environmental stimuli (e.g. equipment noise and staff conversation in an intensive care unit) can result in sensory overload, marked by confusion, disorientation and the inability to make decisions. Restricted environmental stimulation (e.g. with protective isolation) can lead to sensory deprivation. Poor-quality environmental stimuli (e.g. reduced lighting, narrow walkways, background noise) can worsen sensory impairment.

PRE-EXISTING ILLNESS

Peripheral vascular disease can cause reduced sensation in the extremities and impaired cognition. Chronic diabetes mellitus can lead to reduced vision, blindness or peripheral neuropathy. Strokes often produce loss of speech. Some neurological disorders impair motor function and sensory reception.

SMOKING

Chronic tobacco use can cause the taste buds to atrophy, lessening the perception of flavours. Tobacco smoking is also associated with peripheral nerve disorders, macular degeneration and stroke (Scanlon, 2006).

NOISE LEVELS

Constant exposure to high noise levels (e.g. on a construction site) can cause hearing loss.

ENDOTRACHEAL INTUBATION

Temporary loss of speech results from insertion of an endotracheal tube through the mouth or nose into the trachea or from surgery to the neck which may also interfere with the recurrent laryngeal nerve.

Scanlon A 2006 Nursing and the 5As: guideline to smoking cessation interventions (review). Aust Nurs J 14(5):25–8.

Sensory deficits

A deficit in the normal function of sensory reception and perception is a sensory deficit. A person may not be able to receive certain stimuli (e.g. a person who is blind or deaf), or stimuli may become distorted (e.g. a person with blurred vision from cataracts). A sudden loss can cause fear, anger or feelings of helplessness; when senses are impaired, the sense of self is impaired. Initially a person may withdraw by avoiding communication or socialisation with others, in an attempt to cope with the sensory loss. It becomes difficult for the person to interact safely with the environment until new skills relying on existing functions are learned. When a deficit develops gradually or when considerable time has passed since the onset of an acute sensory loss, the person learns to rely on unaffected senses. Some senses may even become more acute to compensate for an alteration. For example, a blind person often develops an acute sense of hearing.

People with sensory deficits may change behaviour in adaptive or maladaptive ways. For example, one person with a hearing impairment may turn the unaffected ear towards the speaker to hear better, whereas another may shun other people to avoid the embarrassment of not being able to understand their speech. Box 26-2 summarises common sensory deficits and their influence on those affected.

BOX 26-2 COMMON SENSORY DEFICITS

VISUAL DEFICITS

Diabetic retinopathy: pathological changes occur in the blood vessels of the retina, resulting in decreased vision or vision loss.

Cataract: cloudy or opaque areas in part or all of the lens that interfere with passage of light through the lens. Cataracts usually develop gradually, without pain, redness or watering eyes.

Dry eyes: result when tear glands produce too few tears. Common in older adults and results in itching, burning or even reduced vision.

Open-angle glaucoma: an increase in intraocular pressure caused by an obstruction to the normal flow of aqueous humour through Schlemm’s canal. Causes progressive pressure against the optic nerve, resulting in visual field loss, decreased visual acuity, and a halo effect around the eyes if untreated.

Presbyopia: a gradual decline in the ability of the lens to accommodate or to focus on close objects. Individual is unable to see near objects clearly.

Senile macular degeneration: condition in which the macula (specialised portion of the retina responsible for central vision) loses its ability to function efficiently. First signs may include blurring of reading matter, distortion or loss of central vision and distortion of vertical lines.

HEARING DEFICITS

Cerumen accumulation: build-up of ear wax in the external auditory canal. Cerumen, which is normally absorbed in a younger person’s ear, becomes hard and collects in the canal, causing a conduction deafness.

Presbycusis: a common progressive hearing disorder in older adults.

BALANCE DEFICIT

Dizziness and disequilibrium: common condition in older adulthood, usually resulting from vestibular dysfunction. Frequently an episode of vertigo or disequilibrium is precipitated by a change in position of the head.

TASTE DEFICIT

Xerostomia: decrease in salivary production that leads to thicker mucus and a dry mouth. Can interfere with the ability to eat and leads to appetite and nutritional problems.

NEUROLOGICAL DEFICITS

Peripheral neuropathy: disorder of the peripheral nervous system. This can occur in older adults, endocrine disorders, entrapment syndromes and connective tissue disorders, and can be associated with potential life-threatening causes such as inflammatory demyelinating polyneuropathy, genetic disorders, toxins, medications, renal and liver disease, infectious diseases, vitamin B (B6 and B12) deficiency and neoplasms (Azhary and others, 2010). Symptoms include numbness and tingling of the affected area and stumbling gait.

Stroke: cerebrovascular accident caused by clot, haemorrhage or emboli affecting a blood vessel leading to or within the brain (Scanlon and Kevin, 2008). Creates altered proprioception with marked lack of coordination and imbalance. Loss of sensation and motor function in extremities controlled by the affected area of the brain also occurs.

Azhary H, Farooq MU, Bhanushali M and others 2010 Peripheral neuropathy: differential diagnosis and management. Am Fam Physician 81(7):887–92; Scanlon A, Kevin J 2008 Stroke (cerebrovascular accident). In Chang E, Johnson A, editors, Chronic illness and disability: principles for nursing practice. Sydney, Churchill Livingstone, pp. 236–50.

Sensory deprivation

The reticular activating system mediates all sensory stimuli to the cerebral cortex, so that even in deep sleep people are able to receive stimuli. Clients in intensive care units (ICUs) are often exposed to physical touch, but this is usually associated with technical intervention rather than personal, comforting touch (Price, 2004). When a person experiences an inadequate quality or quantity of stimulation, such as monotonous or meaningless stimuli, sensory deprivation occurs. Three types of sensory deprivation are:

• reduced sensory input (sensory deficit from visual or hearing loss)

• elimination of order or meaning from input (e.g. exposure to strange environments)

• restriction of the environment (e.g. bed rest or reduced environmental variation) that produces monotony and boredom (Ebersole and others, 2008).

People at risk of sensory deprivation are commonly those living in a confined environment such as a nursing home. Although most good-quality nursing homes offer meaningful stimulation through group activities, environmental design and mealtime gatherings, there are exceptions. The older adult who is confined to a wheelchair, suffers from poor hearing and/or vision, has decreased energy and avoids contact with others is at significant risk of sensory deprivation (Figure 26-1). If the environment creates monotony, the nursing-home resident has a reduced capacity to learn and to think.

There are many effects of sensory deprivation (Box 26-3). The symptoms can easily cause nurses and doctors to believe that a client is psychologically ill and confused, is suffering from severe electrolyte imbalance or is under the influence of psychotropic drugs. Therefore the nurse must always be aware of the client’s existing sensory function and the quality of stimuli within the environment.

Sensory overload

When a person receives multiple sensory stimuli and cannot perceptually disregard or selectively ignore some stimuli, sensory overload occurs. Excessive sensory stimulation prevents the brain from appropriately responding to or ignoring certain stimuli. Because of the multitude of stimuli leading to overload, the person no longer perceives the environment in a way that makes sense. Overload prevents meaningful response by the brain; the person’s thoughts race, attention moves in many directions and anxiety and restlessness occur. As a result, overload causes a state similar to that produced by sensory deprivation. However, in contrast to deprivation, overload is individualised. The amount of stimuli needed for healthy function varies with each individual. People may be subject to environmental overload more at one time than at another. A person’s tolerance to sensory overload may vary by level of fatigue, attitude and emotional and physical wellbeing.

The acutely ill client may fall victim to sensory overload. The constant pain from the disease process, the nurse’s frequent monitoring of vital signs, and the irritation from drainage tubes protruding from the body combine to cause overload. Even if the nurse offers a comforting word or provides a gentle back rub, clients may not benefit because their attention and energy are focused on more-stressful stimuli. Another example is the client who is hospitalised in an ICU. There the activity is constant; lights are always on; sounds can be heard from monitoring equipment, staff conversations, equipment alarms and the activities of people entering the unit. Even at night, an ICU can be very noisy.

The behavioural changes associated with sensory overload can easily be confused with mood swings or simple disorientation. The nurse must look for symptoms such as racing thoughts, scattered attention, restlessness and anxiety. Clients in ICUs sometimes resort to constantly touching tubes and dressings; it is important, therefore, to constantly reorient and control excessive stimuli as part of the client’s care (Price, 2004).

Nursing knowledge base

Factors affecting sensory function

There are multiple factors that may affect an individual’s sensory functioning. These factors relate to the quality and quantity of sensory stimuli. Other influences are family, environmental and cultural factors that affect the client.

People at risk

A nurse assesses sensory function for clients most at risk. Older adults are a high-risk group because of normal physiological changes involving sensory organs; however, the nurse must be careful not to automatically assume that an older adult’s hearing problem is related to advancing age. Adult sensorineural hearing loss can be due to metabolic, vascular and other systemic lesions. A problem with age-related hearing loss is that some individuals who are affected may not even be aware of their deficit (Mattox, 2006). A client may benefit from a referral to an audiologist or otolaryngologist if the assessment reveals serious problems. Other groups that may be at risk are people in ICUs and those suffering head trauma.

Meaningful stimuli

Meaningful stimuli reduce the incidence of sensory deprivation. In the home, meaningful stimuli include pets, a CD/MP3 player or television, pictures of family members, a calendar and a clock. Similar items should be present in a nursing home. In a healthcare setting, the nurse notes whether clients have room-mates or visitors. The presence of others can offer positive stimulation. However, a room-mate who constantly watches television, talks persistently or keeps lights on continuously can contribute to sensory overload. A client can become disoriented in a barren environment that gives few signals for normal sensory perception. The presence or absence of meaningful stimuli influences alertness and the ability to participate in care. In the home or healthcare setting, the environment should be decorated with bright colours and have comfortable furnishings, adequate lighting, good ventilation and clean surroundings.

Amount of stimuli

Excessive stimuli in an environment can cause sensory overload. The frequency of observations and procedures performed in an acute care setting may be stressful. If the client is in pain, has many tubes and dressings or is restricted by casts or traction, overstimulation can be a problem. A client’s room may be near repetitive or loud noises (e.g. a lift, stairwell or nurses’ station) which may contribute to sensory overload.

Family factors

The amount and quality of contact with supportive family members and significant others can influence the degree of isolation the client feels. Whether a client lives alone or whether family and friends frequently visit influences client reactions. The absence of visitors during hospitalisation or residency in a nursing home or extended-care facility can also affect sensory status. This is a common problem in hospital intensive-care settings, where visiting is often restricted. A pattern of social isolation can contribute to sensory changes. The ability to discuss fears or concerns with loved ones is an important coping mechanism for most people. Therefore, the absence of meaningful conversation can cause a person to become sensorially deprived, and the nurse may not be alerted until behavioural changes occur.

Hearing loss in children tends to decrease time spent on social activities and with verbal communication (Olusanya and Newton, 2007). Children with hearing deficits may have behavioural problems, be inattentive and have learning difficulties (Olusanya and Newton, 2007). Often a client is embarrassed by needing to ask another person to repeat what has been said. Instead, they initiate little communication. Clients who find their lifestyles influenced by hearing loss experience loneliness and lowered self-esteem. Social difficulties caused by hearing loss further contribute to the feeling of loneliness.

It is important for the nurse to know the client’s social skills and level of satisfaction with the support given by family and friends. Is the client satisfied with the support made available from friends? Is the client able to solve problems with family members? Does the family offer the support needed when the client requires assistance as a result of a sensory loss? The long-term effects of sensory alterations can influence family dynamics and a client’s willingness to remain active in society.

Environmental factors

A person’s occupation can place them at risk of visual, hearing and peripheral nerve alterations (Box 26-4). Individuals who are exposed to loud noises at work or who have occupations involving exposure to chemicals or flying objects should be screened for hearing and visual problems. People who use their hands in a repetitive fashion, causing trauma to the median nerve, can develop carpal tunnel syndrome, the most common peripheral nerve disorder. Occupations that involve strenuous movement or long periods of extension and flexion of the wrist may cause a person to develop inflammation, which creates pressure on the nerve as it passes between the carpal bones and the transverse carpal ligament in the wrist and may cause numbness, tingling, pain and weakness in the hand while performing fine movements (Scanlon and Maffei, 2009).

BOX 26-4 OCCUPATIONS AND LEISURE ACTIVITIES THAT POSE RISK OF SENSORY ALTERATIONS

A hospitalised client is at risk of sensory alterations due to exposure to environmental stimuli or a change in sensory input. Clients who are immobilised because of bed rest or physical encumbrances (e.g. casts or traction) are at risk, since they are unable to experience all of the normal sensations of free movement. Another group at risk includes clients isolated in a healthcare setting or at home. For example, the client placed in isolation because of tuberculosis (see Chapter 29) is often restricted to a hospital room and unable to enjoy normal interactions with visitors. A healthy person can change an environment or seek a different one, but as a result of illness or hospitalisation a person is often confined to an unfamiliar and unresponsive environment. This does not mean that all hospitalised clients have sensory alterations. However, the nurse must assess more carefully those clients subjected to continued sensory stimulation (e.g. ICU settings, long-term hospitalisation, multiple therapies). The environment can either minimise or heighten sensory alterations. In some cases the environment (e.g. the ICU setting) is the cause of the problem. The nurse assesses the client’s environment, within both the healthcare setting and the home, looking for factors that pose risks or need adjustment to provide safety and more stimulation.

Hazards

A client with sensory alterations is at risk of injury if the living environment is unsafe. For example, a client with visual impairment cannot see potential hazards clearly. A client with proprioceptive problems may lose balance easily. The condition of the home, the rooms and the front and back entrances can be problematic to the client with sensory alterations. Some of the more common hazards include the following:

• uneven, cracked footpaths leading to front/back door

• doormats with slippery backing

• extension and phone cords in traffic areas

• bathrooms without shower or bath grab-rails or mats

• taps unmarked to designate hot and cold

• bathroom floor with slippery surface

• absence of smoke detectors in rooms

• cluttered furniture, including footstools

• kitchen equipment (e.g. ovens, irons, toasters) with control knobs with hard-to-read settings.

In the hospital environment, caregivers often forget to rearrange furniture and equipment to keep paths from the bed and chair to the bathroom and entrance clear. Walking into a client’s room and looking for safety hazards can be a useful exercise:

• Are intravenous (IV) poles on wheels and easy to move?

• Are footstools in the middle of the room?

• Are suction machines, IV pumps or drainage bags positioned so that a client can rise from a bed or chair easily?

Another problem faced by the visually impaired is the inability to read medication labels and syringe gauges. The nurse asks the client to read a label to determine whether the client can read the dosage and frequency. If a client has a hearing impairment, the nurse checks to see whether the sounds of a doorbell, telephone, smoke alarm and alarm clock are easy to discriminate.

Cultural factors

The nurse needs to be aware of cultural and ethnic considerations that may contribute to hearing and visual problems. Diabetic retinopathy is higher in Aboriginal people in the Northern Territory than in the general Australian population (Australian Institute of Health and Welfare, 2006).

The client with sensory alterations expects that the nurse will assess for family, environmental, cultural and other risk factors that might affect sensory functioning so as to plan for early intervention.

Critical thinking synthesis

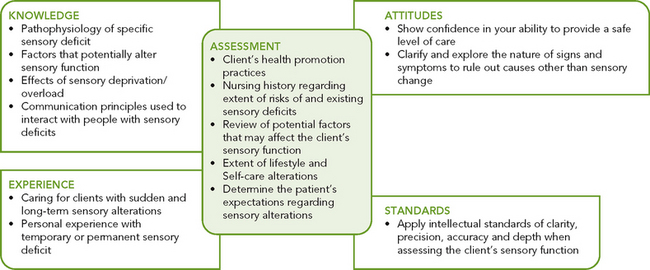

Successful critical thinking requires a synthesis of knowledge, experience, information gathered from clients, critical-thinking attitudes and intellectual and professional standards. Clinical judgments require the nurse to anticipate the information necessary, analyse the data and make decisions regarding client care. Critical thinking is always changing. During assessment (Figure 26-2), the nurse must consider all critical thinking elements that build towards making appropriate nursing diagnoses.

In the case of sensory alterations, the nurse must integrate knowledge of the pathophysiology of sensory deficits, factors that affect sensory function, and therapeutic communication principles. This enables the nurse to recognise a sensory problem when the client describes symptoms, and to then make a clinical judgment of any abnormalities. For example, knowing the usual symptoms of a cataract helps the nurse recognise the pattern of visual changes a client with a cataract will report.

The use of communication knowledge improves the nurse’s ability to acquire a thorough nursing assessment. Previous experience in caring for clients with sensory deficits enables the nurse to recognise limitations in function in each new client, and how limitations might affect the client’s ability to carry out daily activities. For example, after caring for a client with a hearing impairment, the nurse will be able to conduct a more effective assessment of the next client by using approaches that promote the client’s ability to hear the nurse’s questions.

Critical-thinking attitudes and standards, when applied during assessment, ensure a thorough and accurate database from which to make decisions. For example, perseverance is needed to learn details of how visual changes influence a client’s ability to socialise. The Royal Australian and New Zealand College of Ophthalmologists (RANZCO) provides standards for competent practice of screening for eyesight problems. Using critical thinking, the nurse can conduct a thorough assessment and then plan and implement care that will enable the client to function safely and effectively.

NURSING PROCESS

ASSESSMENT

When assessing clients with or at risk of sensory alterations, it is important to consider any pathophysiology of existing deficits as well as all the factors influencing sensory function (see Box 26-1) when assessing a client. For example, if the client has a hearing disorder, the nurse adjusts the communication style and then focuses the assessment on relevant criteria related to hearing deficits. The nurse collects a history that also assesses the client’s current sensory status and the degree to which a sensory deficit affects the client’s lifestyle, psychosocial adjustment, developmental status, self-care ability and safety. The assessment must also focus on the quality and quantity of environmental stimuli.

Mental status

Mental status assessment is an important component of any evaluation of sensory function (Box 26-5). Observation of the client during history taking, during the physical examination and during care provides useful data that can serve as the basis for evaluation of mental status, which is valuable if the nurse suspects sensory deprivation or overload. Observation of the client can provide data that reveal key client behaviours. The nurse observes the client’s physical appearance and behaviour, measures cognitive ability and assesses the client’s emotional status. The Mini Mental Status Examination (MMSE) is an example of a tool that can be used formally to measure disorientation, altered conceptualisation and abstract thinking and change in problem-solving abilities (see Chapter 27). For example, a client with severe sensory deprivation may not be able to carry on a conversation, remain attentive or display recent or past memory.

Sensory alterations history

The nursing history allows assessment of the nature and characteristics of sensory alterations or any problem related to an alteration. It is important to remember that many older adults are sensitive about admitting losses and may hesitate to share information (Ebersole and others, 2008). When taking the sensory alterations history, the nurse should consider the ethnic or cultural background of the client, since certain alterations are higher in some cultural groups (See Working with diversity boxes).

The nurse begins by asking the client to describe the sensory deficit. For example:

Knowledge about the onset and duration of the sensory alteration can be helpful. The nurse learns for how long the client has taken measures to adjust to the alteration:

• ‘How long have you had a visual problem?’

• ‘When did you begin to feel numbness in your legs?’

• ‘How long have you noticed being unable to hear conversations clearly?’

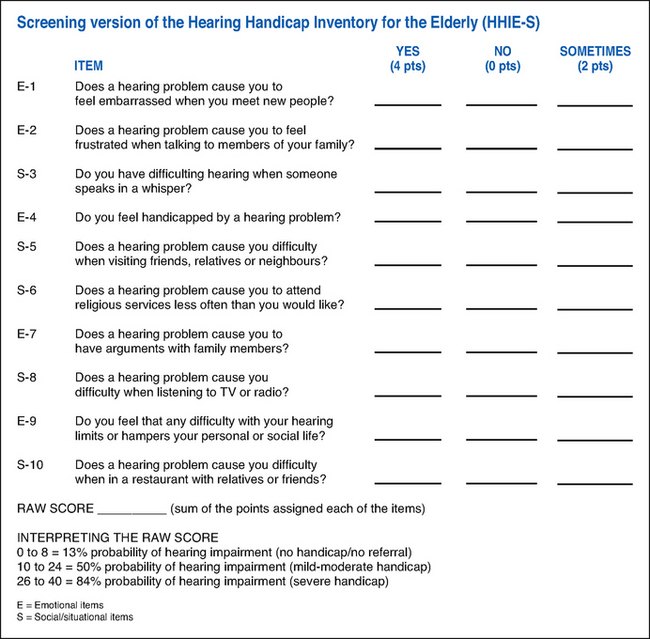

It is also useful to assess the client’s self-rating for a sensory deficit; it has been found that this is as effective as audiometric testing in detecting mild to moderate hearing impairment (Wallhagen and others, 2006). The nurse can say, ‘Rate your hearing as either excellent, good, fair, poor or bad.’ Then, based on the client’s self-rating, the nurse may explore more fully the client’s perception of a sensory loss. This provides a more in-depth look at how the client’s quality of life has been influenced. In the specific case of hearing problems, a screening tool developed by Ventry and Weinstein (1986) has been found to be effective in identifying clients needing audiological intervention. The screening version of this, the Hearing Handicap Inventory for the Elderly (HHIE-S), is a 5-minute, 10-item questionnaire (Figure 26-3) used to assess the emotional and social effects of hearing loss (Mattox, 2006).

FIGURE 26-3 Screening version of the Hearing Handicap Inventory for the Elderly (HHIE-S).

Adapted from Ventry I, Weinstein B 1986 The Hearing Handicap Inventory for the Elderly: a new tool. Ear Hearing 3:133.

WORKING WITH DIVERSITY FOCUS ON CULTURAL CARE

• The prevalence of eye disease in Australian Aborigines contributes significantly to the burden of blindness (Durkin and others, 2006). Trachoma, caused by infection with Chlamydia trachomatis, is a significant factor in ocular morbidity within the Aboriginal community. Access to comprehensive primary heath services has resulted in improvements in environment, hygiene and access to antibiotics, which have reduced the prevalence of trachoma; however, efforts need to continue to be focused in these areas.

• Diabetes mellitus has an earlier age of onset in Māri, Pasifika, Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples compared with the Caucasian population. Delays in diagnosis and lack of access to specialist health services may be the reasons for the higher rate of diabetic eye complications among the Aboriginal community (Laforest and others, 2006).

Durkin S, Casson R, Newland H and others 2006 Prevalence of trachoma and diabetes-related disease among a cohort of adult Aboriginal patients screened over the period 1999–2004 in remote South Australia. Clin Experiment Ophthalmol 34(4):329–34; Laforest C, Durkin S, Selva D and others 2006 Aboriginal versus non-Aboriginal ophthalmic disease: admission characteristics at the Royal Adelaide Hospital. Clin Experiment Ophthalmol 34(4):324–8.

WORKING WITH DIVERSITY FOCUS ON CULTURAL CARE

• Overseas-born people living in Australia suffer disproportionately from type 2 diabetes (Australian Institute of Health and Welfare, 2010). The groups most affected include people from Southern and Eastern Europe, South-East Asia, China, Middle East, North Africa and the Pacific Islands.

• Overseas-born Australians are at higher risk of diabetes-related complications, possibly as a result of problems accessing healthcare due to cultural differences or language barriers.

• Diabetic retinopathy is the third most-common eye disease, affecting more than 97,000 Australians (Australian Institute of Health and Welfare, 2010). Higher rates of diabetic retinopathy have been found in people born in Africa and South Asia and in Fijian Melanesians including Māri (Simmons and others, 2007).

• Visual loss is the most feared of all diabetic complications and accounts, in part, for the high levels of anxiety and depression in the diabetic community (Robertson and others, 2006).

Australian Institute of Health and Welfare (AIHW) Australia’s Health 2010. Cat. no. AUS 122. Canberra, AIHW; Robertson N, Burden ML, Burden A 2006 Psychological morbidity and problems of daily living in people with visual loss and diabetes: do they differ from people without diabetes? Diab Med 23(10):1100–6; Simmons D and others 2007 Ethnic differences in diabetic retinopathy. Diab Med 24(10):1093–8.

A nursing history can also reveal any recent changes in a client’s behaviour. Often, friends or family are the best resources for this information, since the client may be unaware of any change:

• ‘Has the client shown any recent mood swings (e.g. outbursts of anger, nervousness, fear or irritability)?’

Mr Michaels is 84 years old and is the primary caregiver for his 83-year-old wife. During an initial home visit to the wife, the nurse observed that Mr Michaels responded only when he was looking directly at the nurse or was standing close. Otherwise, he would not respond to questions or seemed to ignore what was happening or what was being said.

What follow-up assessments should be gathered? What interventions would be helpful?

Health promotion habits

It is important for the nurse to assess clients’ daily routines in maintaining sensory function. What type of eye and ear care is incorporated into daily hygiene? For people who participate in sports (e.g. football) or recreational activities (e.g. motocross) or who work in a setting where ear or eye injury is a possibility (e.g. chemical exposure, welding, glass or stone polishing, constant exposure to loud noise), the nurse determines whether safety glasses or hearing protection devices are worn. Do clients who use aids such as glasses, contact lenses or hearing aids know how to provide daily care (see Chapter 34)? Are the aids in proper working order?

The nurse also assesses the client’s compliance with routine health screening. When was the last time the client had an eye examination or hearing evaluation? Recommended screening guidelines are usually structured on the basis of age. When a client begins to show a hearing deficit, routine screening should be incorporated in regular examinations.

Finally, the nurse must often rely on personal observation of the client to detect sensory alterations. Ebersole and others (2008) have identified some typical observations indicating hearing loss (Box 26-6).

BOX 26-6 OBSERVATIONS INDICATING HEARING LOSS

• Client seems inattentive to others.

• Client responds with inappropriate anger when spoken to.

• Client believes people are talking about him or her.

• Client has trouble following clear directions.

• Client asks to have something repeated.

• Client has monotonous or unusual voice quality and speaks unusually loudly or softly.

Modified from Ebersole P, Hess P, Schmidt Luggen A and others 2008 Ebersole & Hess’ Toward healthy ageing: human needs and nursing response. St Louis, Elsevier Health Sciences.

Physical assessment

To identify sensory deficits and their severity, the nurse assesses vision, hearing, olfaction, taste and the ability to discriminate light touch, temperature, pain and position (see Chapter 27). Table 26-2 summarises assessment techniques for identifying sensory deficits. In all examples, the nurse will gather more-accurate data if the examination room is private, quiet and comfortable for the client.

TABLE 26-2 ASSESSMENT OF SENSORY FUNCTION

| ASSESSMENT | BEHAVIOUR INDICATING DEFICIT (CHILDREN) | BEHAVIOUR INDICATING DEFICIT (ADULTS) |

|---|---|---|

| VISION | ||

|

Ask client to read newspaper, magazine or lettering on menu Measure visual acuity with Snellen chart (see Chapter 27) Assess visual fields and depth perception |

Self-stimulation, including eye rubbing, body rocking, sniffing or smelling, arm twirling; hitching (using legs to propel while in sitting position) instead of crawling | Poor coordination, squinting, underreaching or overreaching for objects, persistent repositioning of objects, impaired night vision, accidental falls |

| HEARING | ||

|

Perform conventional assessment, including ticking watch, whisper and tuning fork (see Chapter 27) Observe client conversing with others Compare client’s ability to recognise consonants with ability to distinguish vowels Assess client’s perception of hearing ability and history of tinnitus |

Frightened when unfamiliar people approach, no reflex or purposeful response to sounds, failure to be woken by loud noise, slow or absent development of speech, greater response to movement than to sound, avoidance of social interaction with other children | Blank looks, decreased attention span, lack of reaction to loud noises, increased volume of speech, positioning of head towards sound, smiling and nodding of head in approval when someone speaks, use of other means of communication such as lip-reading or writing, complaints of ringing in ears |

| TOUCH | ||

|

Assess client for sensitivity to light touch and temperature (see Chapter 27) Check client’s ability to discriminate between sharp and full stimuli Assess whether client can distinguish objects (coin or safety pin) in the hand with eyes closed |

Inability to perform developmental tasks related to grasping objects or drawing, repeated injury from handling of harmful objects (e.g. hot stove, sharp knife) | Clumsiness, overreaction or under reaction to painful stimulus, failure to respond when touched, avoidance of touch, sensation of pins and needles, numbness |

| SMELL | ||

| Have client close eyes and identify several non-irritating odours (e.g. coffee, vanilla) | Difficult to assess until child is 6 or 7 years old, difficulty discriminating noxious odours | Failure to react to noxious or strong odour, increased body odour, increased sensitivity to odours |

| TASTE | ||

| Inability to tell whether food is salty or sweet, possible ingestion of strange-tasting things | Change in appetite, excessive use of seasoning and sugar, complaints about taste of food, weight change | |

| POSITION SENSE | ||

| Perform conventional tests for balance and position sense (see Chapter 27) | Clumsiness, extraneous movement, excessive arm swinging in those with hyperactivity or learning difficulty | Poor balance and spatial orientation, shuffling gait, reduced response to brace self when falling, more precise and deliberate movements |

The typical physical tests used to screen for hearing impairment rely on an examiner’s whispered voice and a tuning fork. The Welch Allyn audioscope is very effective for measuring hearing acuity. This handheld instrument includes an ear speculum that is placed within the external ear canal. The examiner can view the tympanic membrane to ensure that cerumen is not blocking the canal. A tonal sequence is initiated by pressing a button on the audioscope. The instrument is highly sensitive to detecting hearing loss.

Ability to perform self-care

The nurse assesses clients’ functional abilities in their home environment or healthcare setting, including feeding, dressing, grooming and toileting activities. For example, the nurse assesses whether a client with altered vision can find items on a meal tray and can read directions on a prescription. The nurse also determines a visually impaired client’s ability to perform daily routines such as reading bills and writing cheques, differentiating money denominations and driving a vehicle at night. If a client seems sensorially deprived, is concern shown for grooming? Does a client’s loss of balance prevent rising from a toilet seat safely? Can the client with a stroke manipulate buttons or zips when dressing? Any impairment in the ability to perform self-care has implications for planning discharge from a healthcare setting and in providing resources within the home.

Communication methods

Clients with existing sensory deficits often develop alternative ways of communicating. To interact with the client and to promote interaction with others, the nurse must understand the client’s method of communication. A deaf or hearing-impaired client may read lips, use sign language, listen with the help of a hearing aid or read and write notes. Vision becomes almost a primary sense for the hearing-impaired.

Visually impaired clients are unable to observe facial expressions and other non-verbal behaviours that clarify the content of spoken communication. Instead, they rely on voice tones and inflections to detect the emotional tone of communication. Clients with visual deficits often learn to read Braille.

Clients with aphasia may be unable to produce or understand language. Expressive aphasia, a motor type of aphasia, is the inability to name common objects or to express simple ideas in words or writing. For example, a client may understand a question but be unable to express an answer. Sensory or receptive aphasia is the inability to understand written or spoken language. The client may be able to express words but is unable to understand questions or comments of others. Global aphasia is the inability to understand language or communicate orally.

The temporary or permanent loss of the ability to speak is extremely traumatic. The nurse assesses a client’s alternative communication method and whether it causes anxiety in the client. Clients who have undergone laryngectomies often write notes, use communication boards, speak with mechanical vibrators or use oesophageal speech. Clients with endotracheal or tracheostomy tubes have a temporary loss of speech. Most use a notepad to write their questions and requests; however, the client may become incapacitated and unable to write messages. The nurse needs to determine whether the client has developed a sign language or a system of symbols to communicate needs.

To understand the nature of a communication problem, the nurse must know whether a client has trouble speaking, understanding, naming, reading or writing. Depending on the nature of the problem, the nurse selects the best way to interact with the client.

Other factors affecting perception

The nurse should remember that factors other than sensory deprivation or overload may cause impaired perception (e.g. medications, pain, reduced oxygenation). The nurse assesses the client’s medication history, which includes prescribed and over-the-counter medications. This history includes gaining information regarding the frequency, dose, method of administration and the last time these medications were taken. The nurse should also assess the use of caffeine, and whether other remedies or aids are used (e.g. a hearing aid) and the sensory effects of these on the client. When the nurse identifies that the client has a hearing aid, it is also important to assess whether the aid is working or not, or if the client uses it correctly or benefits from it (Adams-Wendling and Pimple, 2007).

Client expectations

People depend on their senses to provide them with information so as to respond or react to a specific situation or problem. It is essential that a nurse recognises and appropriately manages and supports the patient through any adjustments that are needed. This includes helping each client learn and adapt to a changed lifestyle based on the specific sensory impairment. The nurse should determine from the client exactly what the client expects to achieve and what interventions have been helpful in the past in the management of the client’s limitation. The nurse should remember that clients with sensory alterations have strengthened their other senses and expect the caregivers to anticipate their needs (e.g. for safety and security).

NURSING DIAGNOSIS

After assessment, the nurse reviews all available data and critically looks for patterns and trends suggesting a health problem relating to sensory alterations (Box 26-7). For example, a client’s advanced age, apathy, inattentiveness during conversations, and self-rating of hearing as ‘poor’ are all defining characteristics for the nursing diagnosis of sensory/perceptual alterations (auditory). The nurse validates findings to ensure accuracy of the diagnosis. For example, the diagnosis of altered thought processes could mistakenly be made if the nurse does not confirm the client’s hearing deficit and perception of poor hearing.

BOX 26-7 SAMPLE NURSING DIAGNOSTIC PROCESS

| SENSORY ALTERATIONS | ||

|---|---|---|

| ASSESSMENT ACTIVITIES | DEFINING CHARACTERISTICS | NURSING DIAGNOSIS |

| Assess client’s visual acuity. | Has reduced ability to see objects clearly. Needs brighter light to read. Has trouble distinguishing edges of stairs. | Risk of injury related to visual impairment from cataract formation. |

| Visit home setting and inspect for any hazards that may pose risks to client. | Lighting in rooms, hallways and stairwells is very dim. Carpet in living room is old, and edges are curled up. Steps lead up to front entrance of home. | |

| Review medical record from clinic visit. | Client has been diagnosed as having senile cataracts in both eyes. | |

The nurse determines the factor that is likely to cause the client’s health problem. In this example, impacted cerumen is the aetiology (cause) of the client’s hearing alteration. The aetiology must be accurate, otherwise nursing therapies will be ineffective. For a client with impacted cerumen, regular irrigations of the ear canal may improve auditory perception (Hockenberry and Wilson, 2011). However, if the client’s auditory alteration was related to hearing loss from nerve deafness, nursing interventions for alternative communication methods would be necessary.

The client may also have healthcare problems for which sensory alteration is the aetiology, such as with the diagnosis of risk of injury. The nurse may also select nursing diagnoses by recognising the way that sensory alterations will affect a client’s ability to function (e.g. self-care deficit). The nurse must recognise patterns of data that reveal health problems created by the client’s sensory alteration (Box 26-8).

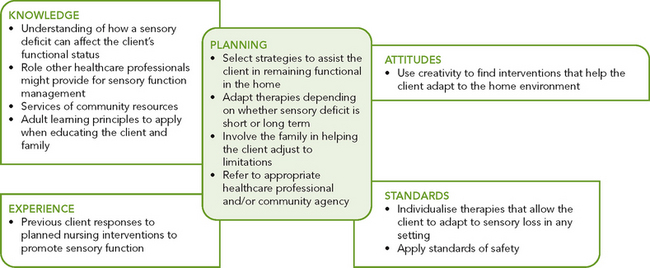

PLANNING

During planning, the nurse again synthesises information from multiple resources (Figure 26-4). The nurse reflects on knowledge gained from the assessment and of how sensory deficits affect normal functioning. In this way the nurse can recognise the extent of the client’s deficit and know the type of interventions most likely to be helpful. The nurse also considers the role that healthcare professionals can play in planning care, and the available community resources that may be useful. The nurse’s previous experience in caring for clients with sensory alterations can be invaluable and should help the nurse plan approaches that ensure a client’s safety while maximising the client’s independence.

Critical thinking ensures that the client’s plan of care integrates all that the nurse knows about the individual, as well as information applied through the critical thinking elements. Professional standards are especially important to apply when the nurse develops the plan of care. These standards, in the form of clinical pathways (see Chapter 4) or evidence-based treatment protocols, often recommend scientifically proven interventions for the client’s condition. For example, clients who have visual deficits and are hospitalised may be placed on a fall-prevention protocol that will incorporate research-based precautions to ensure client safety.

The nurse develops an individualised plan of care for each nursing diagnosis (see Sample nursing care plan). The nurse and client set realistic expectations of care together. Goals are to be individualised and realistic, with measurable outcomes.

Priorities of care must be set with regard to the extent that a sensory alteration affects a client. Safety is a top priority. The client can also help prioritise aspects of care. For example, the client may wish to learn ways to communicate more effectively or to participate in favourite hobbies given their limitation.

Some sensory alterations are short-term (e.g. a client suffering sensory/perceptual alterations as a result of sensory overload in an ICU). Appropriate interventions are thus likely to be temporary (e.g. frequent reorientation or introduction of intimate and pleasant stimuli such as a back rub). Sensory alterations such as permanent visual loss require long-term goals of care for clients to adapt. However, clients who have sensory alterations at the time of entering a healthcare setting are usually best informed about how to adapt interventions to their lifestyles. People with severe visual impairments in particular need to control whatever part of their care they can. Sometimes it becomes necessary for the client to make major changes in self-care activities, communication and socialisation.

When developing a plan of care, the nurse considers all resources available to clients. The family can play a key role in providing meaningful stimulation and by learning ways to help the client adjust to any limitations. The nurse may also refer the client to other healthcare professionals. Early referrals to occupational or speech therapists, for example, can speed a client’s recovery. There are also numerous community-based resources, for example associations for blind and deaf people, government and state support organisations and home care services (see Online resources). The nurse may be able to arrange a volunteer to visit a client or have printed materials made available that describe ways to cope with sensory problems.

The goals of care for a client with actual or potential sensory alterations may include that the client:

• maintains current functioning of existing senses

• has an environment that contains meaningful sensory stimuli

• interacts in a safe environment

• experiences no additional sensory loss

• communicates effectively with existing sensory alterations

• is able to perform self-care

Nursing interventions involve the client and family so that a safe, pleasant and stimulating sensory environment can be maintained. The most effective interventions enable the client with sensory alterations to function safely with existing deficits. The client is generally able to continue a normal lifestyle.

SENSORY/PERCEPTUAL ALTERATIONS

ASSESSMENT*

Judy Long, a 65-year-old receptionist for a factory outlet, complains to the community health nurse that lately it seems that a film has formed over her left eye, making her vision blurred. She notices that in some lighting there is a glare. She comments that she is having increasing difficulty seeing to drive. Specifically, she cannot tolerate driving at night—the oncoming headlights are blurred. Judy has had her neighbour drive her places, but this makes her feel as though she is losing her independence. She reports that she has always worked and managed her home, and has volunteered at a local library. She indicates that since this problem with her vision, she has been reluctant to use the stairs in her home. Judy visited an ophthalmologist, who told her she has a cataract, and she is scheduled for surgery in 3 weeks.

NURSING DIAGNOSIS: Sensory/perceptual alterations (visual) related to altered sensory reception of senile cataract.

PLANNING

| GOALS | EXPECTED OUTCOMES |

|---|---|

| INTERVENTIONS† | RATIONALE |

|---|---|

| Environmental management | |

|

• Instruct client to keep walking area in home and work area free of clutter, footstools and electrical cords, and to avoid rearranging furniture. • Instruct client to reduce glare by wearing dark-coloured sunglasses for outside and light-coloured glasses for inside. • Teach client to use a light over the shoulder for reading and writing. |

Keeping the area clutter-free reduces the risk of injury, and these measures help promote a safe environment (Beaver and Mann, 1995). Clients have better visual acuity when they protect their eyes from bright light (Cleary, 1995). People with cataracts see better with wider illumination (Cleary, 1995). |

| Emotional support | |

| People who experience visual loss grieve over loss of independence (Vader, 1992). | |

| Family involvement | |

| An alternative means of transport will foster safety (Beaver and Mann, 1995). | |

†Intervention classification labels from Nursing Interventions Classification (NIC) 2008 ed 5. St Louis, Mosby.

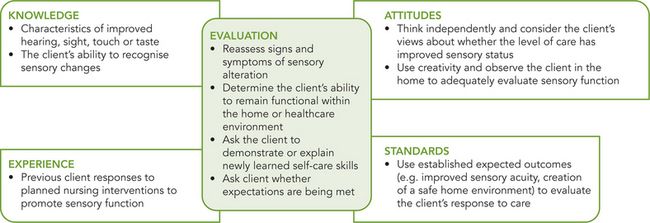

EVALUATION

Ask client to describe the changes that have made the home environment safer. During a home visit, observe the home environment for safety hazards.

Observe client’s verbal and non-verbal responses to the lifestyle adaptations.

Ask whether client is able to maintain a degree of independence with the environmental and lifestyle modifications.

*Defining characteristics are shown in bold type.

Learning to adjust to sensory impairments can occur at an early age. However, every person begins to develop sensory changes as they age. Nursing interventions are chosen depending on the nursing diagnosis identified and the related factors contributing to the client’s problem. There are measures to take to maintain sensory function at the highest level possible. This ensures a stimulating environment for the client and an improved level of health.

IMPLEMENTATION

Health promotion

Good sensory function begins with prevention. Almost everyone becomes exposed to risks in the environment that may cause sensory alterations. When clients enter primary care settings, the nurse can take the opportunity to review commonsense approaches for reducing risk of sensory loss (see Research highlight).

SCREENING

The prevention of visual impairment in children requires appropriate screening (Chou and others, 2011). There are three recommended interventions:

1. screening for rubella or syphilis in women who are considering pregnancy

2. adequate prenatal care to prevent premature birth (with the danger of exposure of the infant to excessive oxygen)

3. periodic screening of all children, especially newborns to preschoolers, for congenital blindness and visual impairment caused by refractive errors and strabismus.

Visual impairments are common during childhood. The most common visual problem is a refractive error such as nearsightedness. The nurse’s role is to detect and refer. Parents must know signs suggesting visual impairment (e.g. failure to react to light and reduced eye contact from the infant). These signs should be reported to a doctor immediately. Vision screening of school-age children and adolescents can detect problems early. The school nurse is usually responsible for vision testing.

Hearing impairment is one of the most common disabilities in Australia. There are nearly two million Australians with a significant hearing loss, one-third of whom suffer permanent tinnitus, or ringing in the ears (Australian Institute of Health and Welfare, 2011). Children at risk include those with a family history of childhood hearing impairment, perinatal infection (rubella, herpes, cytomegalovirus), low birthweight, chronic ear infection and Down syndrome. Nurses should advise pregnant women of the importance of early prenatal care, avoidance of ototoxic drugs and testing for syphilis or rubella.

Research focus

With the ageing of the population, nurses are increasingly more likely to be providing care to older people with mild to severe hearing impairment. Hearing loss is one of the most common disabilities occurring in older people, affecting between 35% and 45% of adults aged over 50 years. Hearing impairment is associated with depression, poorer physical functioning and decreased quality of life.

Research abstract

The Blue Mountains Hearing Study is a population-based survey of age-related hearing loss in a representative older Australian community. Participants (n = 2431) completed the SF-36 which measures health-related quality of life. Additionally each participant undertook a hearing assessment.

The prevalence of unilateral hearing impairment was 13.3% (n = 285 mild; 39 moderate–severe). For bilateral hearing impairment the prevalence was 31.8% (n = 478 mild; 282 moderate–severe). One third of people (n = 233) with bilateral hearing impairment reported owning a hearing aid, with 180 people (25.5%) using them regularly.

The study indicates that people with bilateral hearing impairment have lower quality of life than people with unilateral or no hearing impairment. The greatest effects of the disability were found to be limitations on social and physical functioning and emotional health. People who routinely wear their hearing aids report a higher quality of life than those who do not.

Evidence-based practice

• Nursing practice needs to focus on the individual’s abilities rather than disabilities, using an individualised approach with each client.

• Nurses require sensitivity to the potential for social isolation of older people with hearing disabilities.

• Clear and timely communication is essential with a person with hearing impairment.

• Nursing assessment needs to be thorough and include the psychosocial areas of health to ensure that anxiety or depression is documented and treated.

• This study reports the benefits of wearing a hearing aid for people with bilateral hearing impairment. Nurses have an educative role in supporting the use of hearing aids where possible.

Children with chronic middle ear infections, a common cause of impaired hearing, should receive periodic auditory testing. Parents must be warned of the risks and should seek medical care when the child has symptoms of earache or respiratory infection.

Hearing loss from noisy environments was once thought to affect mainly older people, but it is now occurring in 20- to 30-year-olds. This loss is attributed to exposure to noise at constantly high levels, such as from home and car stereo systems, concerts and aerobics classes. School nurses should participate in providing hearing conservation classes for teachers and students alike (Wallhagen and others, 2006).

For adults, routine screening of visual and hearing function is imperative for early detection of problems. This is especially true in the case of glaucoma, which if undetected can lead to permanent visual loss. In Australia about 300,000 people have glaucoma. Examinations should occur every 1–2 years from age 35 years if there is a family history of glaucoma, or if the client suffers from migraine, myopia, hypertension or diabetes, has had a serious eye injury, has taken steroid medications or is over 65 years of age. Diabetic retinopathy is present in nearly one-third of people with diabetes and threatens vision in 10%. Among those with no retinopathy, 10% will develop glaucoma each year. Compared with the general population, people with diabetes have about a 25-fold risk of blindness. Visual loss can be prevented in almost all cases, provided that the retinopathy is identified early. This requires regular eye screening for all people with diabetes (Mitchell and Foran, 2008).

The guidelines for hearing screening for adults are less prescriptive. Generally, if a person works or lives in an environment where there is a high noise level, routine screening is highly recommended. Nurses in occupational settings can assess for symptoms of tinnitus and make prompt referrals. Mattox (2006) suggests that early detection may prevent hearing disabilities in many people. The most important thing for adults to understand is that hearing loss is not necessarily a natural part of ageing. Once hearing loss is acknowledged, it is important to have regular hearing testing. Nurses should encourage older adults to follow through with recommendations for hearing aids.

PREVENTIVE SAFETY

Trauma is a common cause of blindness in children, for example penetrating injury from rocks, sticks and scissors or toy weapons. Parents and children require counselling on ways to avoid eye trauma (Box 26-9). Safety equipment can readily be found in most sports shops and large department stores.

BOX 26-9 TIPS FOR PREVENTING EYE INJURY IN CHILDREN

SCHOOL-AGE CHILDREN AND ADOLESCENTS

• Teach proper use of potentially dangerous equipment such as power tools and sports equipment (e.g. hockey sticks).

• Stress use of eye protection when playing ball and racquet sports, using power tools or riding motorcycles.

• Warn children not to look directly at the sun even when wearing sunglasses.

Adults are at risk of eye injury while playing sports and working in jobs where they are exposed to chemicals or flying objects. Safe Work Australia (2012) provides guidelines for safety in the workplace. Employers are required to have employees wear protective goggles and/or use equipment such as hearing-protection devices to reduce the risk of injury. Nurses in occupational health settings can reinforce use of protective equipment.

Preventing hearing loss requires people to avoid exposure to continuous high noise levels and brief loud impulse noise. Protection should be worn by people who must work around noise. Earplugs and earphones are useful in blocking high-decibel sounds.

Regular immunisation of children against diseases capable of causing hearing loss (e.g. rubella, mumps and measles) is important. Nurses who work in doctors’ surgeries, schools and community clinics should reinforce the importance of early and timely immunisation. When a child or an adult develops any type of health problem, caution should be used in prescribing drugs that are ototoxic.

USE OF AIDS

Health promotion requires appropriate use of aids and good, routine hygiene measures. People who wear corrective contact lenses, glasses or hearing aids should make sure they are kept clean, accessible and functional (see Chapter 34). It is helpful to have a family member or friend also know how to clean an aid (Box 26-10).

BOX 26-10 CLIENT TEACHING FOR TROUBLESHOOTING HEARING AID MALFUNCTION

TEACHING STRATEGIES

• Show family member locations on hearing aid device where damage (e.g. cracks, fraying) are likely to occur: ear mould or case, earphone, dials, cord and connection plugs.

• Demonstrate battery replacement; have extra set of unused batteries available.

• Review method to check volume: turn dial to maximum gain to check. Is voice clear?

• Consult manufacturer’s directions for specific care measures for cleaning battery case and ear mould.

• Review factors to report to hearing aid laboratory: static, distortion of sound, poor volume quality.

It is important for contact-lens wearers to clean lenses often (see Chapter 34) and to use the appropriate solutions for cleaning and disinfection. With the rise in use of soft contact lenses, particularly extended-wear lenses, some people have become casual about both the care and the wearing time of the contacts; as a result, there has been an increase in serious corneal infections. Infrequent lens disinfection, contamination of lens storage cases and contact-lens solutions and use of home-made saline adds to the risk. Swimming while wearing lenses also creates a serious risk of infection.

Wearing a hearing aid no longer has to involve a social stigma. There are various aids that not only successfully enhance a person’s hearing but are also cosmetically acceptable. Chapter 34 summarises the types of hearing aids available and tips for proper care and use.

PROMOTING MEANINGFUL STIMULATION

Life becomes much more enriching and satisfying when meaningful and pleasant stimuli exist within the environment. There are many ways in which the nurse can help clients make adjustments to their environment so that it becomes more stimulating. This is best done when the nurse considers the normal physiological changes that accompany sensory deficits.

VISION

As a result of the normal changes of ageing, the pupil’s ability to adjust to light is diminished. Thus, older adults can be very sensitive to glare. The nurse can suggest ways to minimise glare, for example using satin and non-gloss finishes for walls and countertops in the home and choosing sheer curtains, tinted windows or adjustable shades to reduce outdoor light. Wearing sunglasses outside can obviously reduce the glare of direct sunlight.

The ability to read is important to everyone. Therefore, clients should be allowed to use their glasses whenever possible (e.g. during procedures and client instruction); it helps clients to remain oriented, maintain some control and retain their dignity (Larsen and others, 1997). Clients with reduced visual acuity may need more than corrective lenses. A pocket magnifier can help a client read most printed material. Telescopic lens glasses are smaller, easier to focus and have a greater range (Figure 26-5). There are also books and other publications available in larger print. If clients have a legal or other important document they wish to read, standard copying machines have enlarging capabilities.

FIGURE 26-5 A variety of telescopic lenses aid the visually impaired.

From Potter PA, Perry AG 2002 Fundamentals of Nursing, ed 5. St Louis, Mosby.

With ageing, a person experiences a change in colour perception. Perception of the colours blue, violet and green usually declines. Brighter colours such as red, orange and yellow are easier to see. The nurse can suggest ways to decorate a room and paint hallways or stairwells so that differentiations can be made in surfaces and objects in a room.

HEARING

One way to help an older adult with a hearing loss is to ensure that the problem is not impacted cerumen. With ageing, cerumen thickens and builds up in the ear canal. Excessive cerumen occluding the ear canal can cause a conductive hearing loss. Softening agents can be used to loosen the cerumen prior to irrigation of the canal with tepid water in a 60 mL syringe (see Chapter 34). Removal of cerumen can significantly improve the client’s hearing ability; however, extreme caution is required when undertaking this procedure.

To maximise residual hearing function, the nurse can suggest ways to modify the environment. Telephones and televisions can be amplified. Alarm clocks that shake the bed or activate a flashing light are useful devices. An innovative way to enrich the lives of the hearing-impaired is recorded music. Music recorded in the low-frequency sound cycles can be heard by clients with severe hearing loss.

TASTE AND SMELL

The nurse can easily promote the sense of taste by using measures to enhance remaining taste perception (Duffy, 2007). Good oral hygiene keeps the taste buds well hydrated. Taste perception is heightened if foods are well seasoned, differently textured and eaten separately. Vinegar or lemon juice can add tartness to food. The nurse should always ask the client what foods are the most taste-appealing. If taste perception is improved, food intake and appetite will also improve.

Stimulation of the sense of smell with aromas such as brewing coffee and baking bread can heighten taste sensation. People should avoid blending or mixing foods, because these actions make it difficult to identify tastes. Older people should chew food thoroughly to allow more food to contact remaining taste buds.

Smell can be improved by strengthening pleasant olfactory stimulation. A client’s environment can be made more pleasant with smells such as cologne, mild room deodorisers, fragrant flowers and sachets. The nurse also encourages clients to sniff food before eating. When the nurse helps clients with eating or sets up a meal tray in a healthcare setting, naming the foods may help clients imagine the aromas. The client is again an important resource. Certain aromas may actually cause clients to lose their appetites.

Removal of unpleasant odours improves the quality of a person’s environment. The nurse should keep a client’s room clean, empty bedpans or urinals, remove and dispose of soiled dressings and keep bathroom doors closed.

TOUCH

Clients with reduced tactile sensation usually have the impairment over a limited portion of their bodies. The nurse can stimulate existing function by providing touch therapy. If the client is willing to be touched, hair brushing and combing, a back rub and touching of the arms or shoulders are ways of increasing tactile contact. When sensation is reduced, a firm pressure may be necessary for the client to feel the nurse’s hand. Turning and repositioning can also improve the quality of tactile sensation. When invasive procedures are being performed, it is important to use touch, hold clients’ hands and keep them warm and dry.

If a client is overly sensitive to tactile stimuli (hyperaesthesia), the nurse must minimise irritating stimuli. Keeping bedclothes loose to minimise direct contact with the client and protecting the skin from exposure to irritants are helpful measures. If the client has numbness and tingling or pain in the hands, as with carpal tunnel syndrome, special wrist splints may be worn to dorsiflex the wrist to relieve the nerve pressure. For those clients who use computers, special keyboards are available to decrease the pressure on the median nerve, aid in the relief of pain and promote healing.

ESTABLISHING SAFE ENVIRONMENTS

When sensory function becomes impaired, people become less secure and the world around them becomes smaller. Older adults in particular find it important to feel secure about their immediate environment. This is necessary for the person to have a sense of independence and to function within the home. The nurse can make recommendations to help clients make their living environment safer without restricting their independence. During a home visit or while completing an examination in the clinic, the nurse can offer several useful suggestions for home safety. The nature of the actual or potential sensory loss determines the safety precautions taken.

ADAPTATIONS FOR VISUAL LOSS

Whether a visual alteration is a result of injury, eye disease or the changes of ageing, safety becomes a factor if visual acuity, peripheral vision, adaptation to the dark and depth perception are permanently reduced. With reduced peripheral vision, a client cannot see panoramically, since the outer visual field is less distinct. This creates a special hazard for driving. Older adults with reduced adaptation to the dark require three times as much light to see objects as they did as young adults. With reduced depth perception, a person cannot see how far objects are from them. This is a special danger for a person with visual impairment when walking down stairs.

To create a safe environment, the nurse begins by looking at the results of the home environment assessment (see Chapter 15). What hazards exist in the client’s living areas? Clutter such as footstools, children’s toys and electrical cords in walking areas should be removed. Electrical cords should be placed under or behind furniture. Furniture should be arranged so that a person can move about easily without fear of tripping or running into objects.

Because of reduced depth perception, an older adult can trip on rugs, runners or the edge of stairs. All flooring or carpeting should be kept in good repair. The nurse can advise the client to use low-pile carpeting. Thresholds between rooms should be level with the floor. Any stairwell should have a securely fastened banister or handrail extending the full length of the stairs.

Front and back entrances to the home, work areas and stairwells can be dangerous if improperly lit. The nurse encourages the client to have lights installed with higher wattage and wider illumination. Fluorescent lighting should be avoided. A light switch should be located at the top and the bottom of stairwells. It is also important to be sure lighting on the stairs does not cast shadows. Be sure the client can clearly see the edge of each step, especially the first and last. When possible, steps inside and outside the home should be replaced with ramps.

Driving can be a particular safety hazard for older adults. Changes in the lens cause the older adult to be highly sensitive to glare during night driving. Reduced peripheral vision may prevent a driver from seeing a car in an adjacent lane. Vision is a primary consideration for safety, but there are other factors as well. Older clients may have decreased reaction time, reduced hearing and decreased strength in the legs and arms. All of these factors can affect an older adult’s driving skills. Box 26-11 summarises tips for older adults who continue to drive.

The inability to see visual contrast can be a problem for an older adult. Sometimes settings on electrical appliances and equipment are highlighted only in black and white or shades of grey. Colour contrasts help to distinguish settings. Coloured tape, paint or nail polish can be used to colour-code appliance dials. Colour can also be useful to highlight the edge of stairs. Painting the edge of stairs with bright orange paint or applying a broad strip of coloured tape at the stair edge can help a person see the edges of stairs more clearly. The nurse can help the client tour the home to find opportunities for colour coding.

If a client is partially or totally blind, fire hazards should be removed from the home. Flammable items such as paper and cloth should be kept away from the stove. A client who smokes must learn to discard ashes frequently into an ashtray. Water in the bottom of an ashtray helps ensure that cigarette butts are extinguished.

An added consideration for people with visual impairment is the assurance that eye medications are administered safely. For conditions such as glaucoma, clients must closely adhere to regular medication schedules. Older adults may have some difficulty manipulating eyedroppers. A friend or spouse should always be familiar with dosage schedules in case a client is unable to self-administer a medication.

ADAPTATIONS FOR REDUCED HEARING

Important environmental sounds (e.g. doorbells and alarm clocks) may best be heard if amplified or changed to a lower-pitched, buzzer-like sound. There are also sound lamps that respond with light to sounds such as doorbells, burglar alarms, smoke detectors and babies crying. Signalling devices allow the deaf person greater independence. Family members or anyone who calls the client regularly should learn to let the phone ring for a longer period. There are amplified receivers for telephones and telephone communications devices that use a computer and printer to transfer words over the telephone for the hearing-impaired. Both sender and receiver must have the special device to complete a call. Text messaging services available for cellphones or computers are also commonly used.

ADAPTATIONS FOR REDUCED OLFACTION