Collaborative therapy

Conservative therapy

Administration of B-complex vitamins

Rest

Avoidance of alcohol, minimise or avoid aspirin, paracetamol and non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs

Ascites

Administration of 12,500 kJ, high-carbohydrate, high-protein, low-fat and low-sodium diet

Diuretics

Paracentesis (if indicated)

Peritoneovenous shunt (if indicated)

Oesophageal or gastric varices

β-adrenergic blockers

Octreotide

Vasopressin

Endoscopic band ligation or sclerotherapy

Balloon tamponade

Surgical shunting procedure

Transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt

Hepatic encephalopathy

Antibiotics to decrease bacterial flora in gastrointestinal tract

Lactulose

Ascites

Management of ascites is focused on sodium restriction, diuretics and fluid removal. The amount of sodium restriction is based on the degree of ascites. Initially the patient may be encouraged to limit sodium intake to 2 g per day. Patients with severe ascites may need to restrict their sodium intake to 250–500 mg per day. Very low sodium intake can result in reduced nutritional intake and subsequent problems associated with malnutrition. The patient is usually not on restricted fluids unless severe ascites develops. There should be accurate assessment and control of fluid and electrolyte balance. Bed rest initially produces diuresis, which increases fluid excretion. Salt-poor albumin may be used to help maintain intravascular volume and adequate urinary output by increasing plasma colloid osmotic pressure.

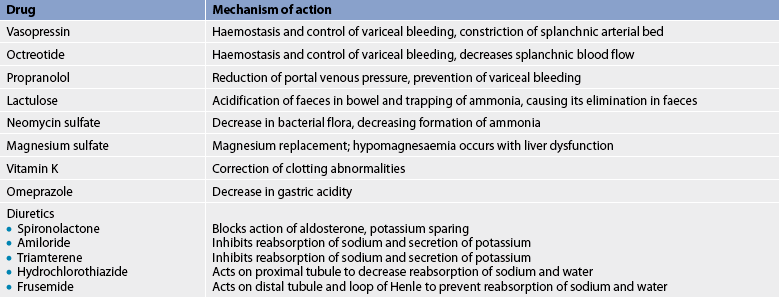

Diuretic therapy is an important part of management. Often a combination of drugs that work at multiple sites in the nephron is more effective. Spironolactone is an effective diuretic, even in patients with severe sodium retention. Spironolactone is an antagonist of aldosterone and is potassium sparing. Other potassium-sparing diuretics include amiloride and triamterene. A high-potency loop diuretic, such as frusemide, is frequently used in combination with a potassium-sparing drug. Hydrochlorothiazide may also be used but the thiazide diuretics are not as potent as the loop diuretics.

A paracentesis (needle puncture of the abdominal cavity) may be performed to remove ascitic fluid. However, it is reserved for the patient with impaired respiration or abdominal pain caused by severe ascites. It is only a temporary measure because the fluid tends to re-accumulate.

Peritoneovenous shunt

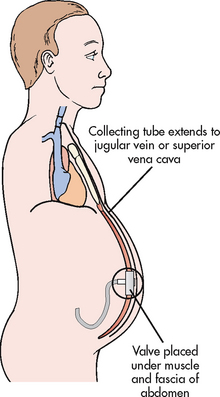

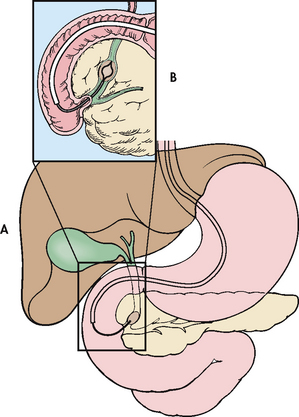

A peritoneovenous shunt is a surgical procedure that provides continuous reinfusion of ascitic fluid into the venous system. One type, the LaVeen peritoneovenous shunt, consists of a tube and a one-way valve. The tube runs from the abdominal cavity through the peritoneum, under the subcutaneous tissue and into the jugular vein or superior vena cava (see Fig 43-9).

Peritoneovenous shunt is not a first-line therapy for ascites because of the number of complications associated with it, including thrombosis formation at the venous tip of the shunt, infection, fluid overload, disseminated intravascular coagulopathy, variceal haemorrhage and shunt occlusion. In addition, peritoneovenous shunts do not improve patient survival rates. TIPS (discussed later in this section) is now more commonly used in this condition.

Oesophageal and gastric varices

The main therapeutic goal in the management of varices is avoidance of bleeding and haemorrhage. Risk factors for bleeding include variceal size, decreased wall thickness and degree of liver dysfunction. The patient who has oesophageal/gastric varices should avoid ingesting alcohol, aspirin, anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) and irritating foods. Upper respiratory tract infections should be treated promptly and coughing should be controlled. For patients who have not bled from their varices, prophylactic treatment with non-selective β-blockers (e.g. propranolol) has been shown to reduce the risk of bleeding, as well as bleeding-related deaths.22

Management of bleeding varices includes emergency, therapeutic and prophylactic interventions. A combination of drug and endoscopic therapy is more successful than either approach alone.22 Drug therapy may include octreotide, vasopressin and β-adrenergic blockers. Endoscopic therapies include ligation of varices and sclerotherapy. Radiological or surgical shunt therapy may also be used.

When variceal bleeding occurs, the first step is to stabilise the patient and manage the airway. Large-bore IV cannulas are inserted for administration of plasma expanders and blood products when available. Emergency endoscopy is performed as soon as possible to confirm the diagnosis and rule out other causes of GI bleeding. At the time of endoscopy, variceal ligation should be performed. Sclerotherapy may be useful if banding is not possible.

The main goal of drug therapy is to stop bleeding so that endoscopic treatment measures can be performed. The initial measures to stop the bleeding include IV administration of octreotide, which decreases splanchnic blood flow, or vasopressin, which produces vasoconstriction of the splanchnic arterial bed, decreases portal blood flow and decreases portal hypertension. Vasopressin has many side effects, including cardiac and peripheral ischaemia, arrhythmias, bowel ischaemia and hypertension.23 Because of this glyceryl trinitrate is often given in combination with vasopressin—the glyceryl trinitrate reduces the detrimental effects of the vasopressin while enhancing its beneficial effect. Vasopressin should be avoided or used cautiously in older patients because of the risk of cardiac ischaemia.

Endoscopic treatments

The procedure of choice for managing acute variceal bleeding is endoscopic ligation or banding of the varices. A small rubber band (elastic O-ring) is applied around the base of the varix. In endoscopic sclerotherapy, the sclerosing agent is injected directly into or adjacent to the varix, producing thrombosis and obliterating the distended vein. Endoscopic ligation is more effective than endoscopic sclerotherapy with fewer complications. For bleeding gastric fundal varices, injection with cyanoacrylate glue is used for variceal obliteration. The application of an endoscopically applied loop, which is tightened around the base of the gastric varix, is an alternative treatment.

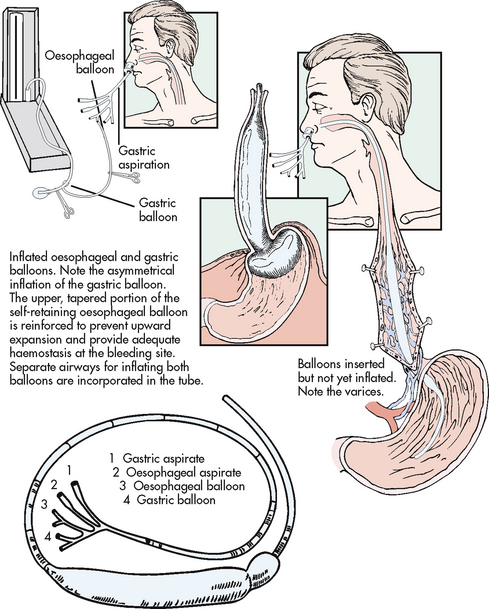

Balloon tamponade may be used in patients with oesophageal or gastric variceal haemorrhage that cannot be controlled with endoscopy. Balloon tamponade controls the haemorrhage by mechanical compression of the varices and by reducing venous flow through the gastric cardia. Adapted from the original Sengstaken-Blakemore tube, the Minnesota tube (see Fig 43-10) has two balloons—gastric and oesophageal—and two drainage ports—oesophageal and gastric. When the gastric balloon is inflated and traction is applied to the tube, venous flow through the cardia is diminished. Direct pressure is also applied to any gastric fundal varices. Inflation of the oesophageal balloon applies direct pressure to variceal columns in the oesophagus and is used if traction-compression from the gastric balloon does not control bleeding from oesophageal varices.

Supportive measures during an acute variceal bleed include administration of fresh frozen plasma and packed RBCs, vitamin K1 (phylloquinone) and proton pump inhibitors such as omeprazole. Lactulose and neomycin administration may be started to prevent hepatic encephalopathy from breakdown of blood and the release of ammonia in the intestine.

Long-term management

Long-term management of patients who have had an episode of bleeding includes β-adrenergic blockers, repeated endoscopic ligation and portosystemic shunts. There is a high incidence of recurrent bleeding with a high mortality risk with each bleeding episode, so continued therapy is necessary. Repeated endoscopic variceal ligation is continued until the varices are obliterated.

Propranolol, a β-adrenergic blocker, can be given orally to prevent recurrent GI bleeding. It reduces portal venous pressure. This effect is due to reduced cardiac output and, possibly, constriction of splanchnic vessels. However, because it reduces hepatic blood flow, it can enhance the possibility of hepatic encephalopathy.

Shunting procedures

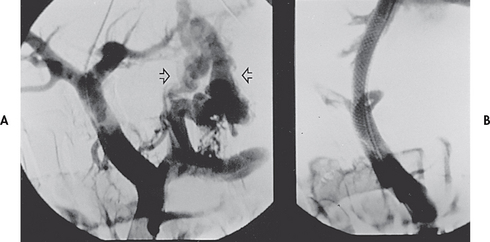

Surgical and non-surgical methods of shunting blood away from the portal system are also available. Shunting procedures tend to be used more after a second major bleeding episode than an initial bleeding episode. TIPS is a non-surgical procedure in which a tract (shunt) is created between the systemic and portal venous systems to redirect portal blood flow (see Fig 43-11). A catheter is placed in the jugular vein and threaded through the superior and inferior vena cava to the hepatic vein. The wall of the hepatic vein is punctured and the catheter is directed to the portal vein. Stents are positioned along the passageway, overlapping in the liver tissue and extending into both veins. This procedure reduces portal venous pressure and decompresses the varices, thus controlling bleeding. It does not interfere with future liver transplantation. Limitations of the procedure include the increased risk of hepatic encephalopathy and stenosis of the stent. TIPS is contraindicated in patients with severe hepatic encephalopathy, hepatic carcinoma and portal vein thrombosis.

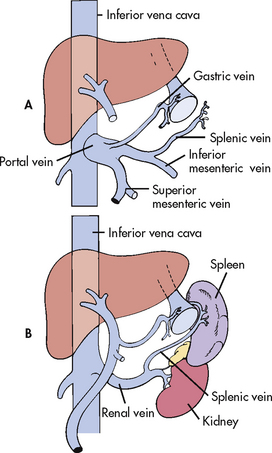

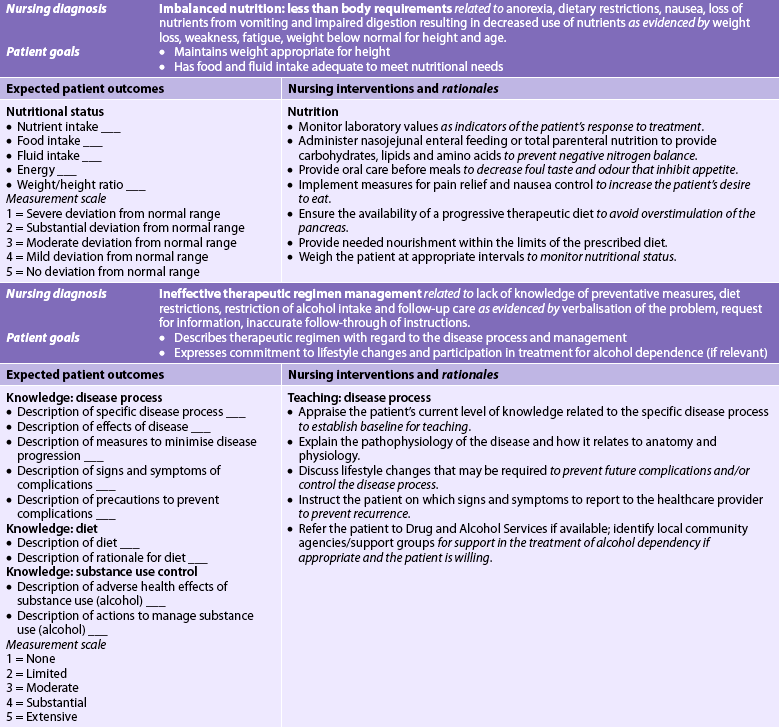

Various surgical shunting procedures may be used to decrease portal hypertension by diverting some of the portal blood flow while at the same time allowing adequate liver perfusion. Currently, the surgical shunts most commonly used are the portacaval shunt and the distal splenorenal shunt (see Fig 43-12). Surgical shunts are more likely to be used in emergency situations. Although a prophylactic portacaval shunt decreases bleeding episodes, it does not prolong life. Patients die of hepatic encephalopathy caused by the diversion of ammonia past the liver and into the systemic circulation. The distal splenorenal shunt (Warren shunt) leaves portal venous flow intact (see Fig 43-12, B), so it has a lower incidence of hepatic encephalopathy. However, with time the flow of blood through the liver decreases. Similar to TIPS, surgical stents are also prone to occlusion, necessitating angiography and stent dilatation.

Hepatic encephalopathy

The goal of management of hepatic encephalopathy is the reduction of ammonia formation. Several measures to reduce ammonia formation in the intestines are used. Lactulose is a synthetic keto-analogue of lactose. In the colon, it is split into lactic acid and acetic acid, which decreases the pH from 7.0 to 5.0. The acidic environment discourages bacterial growth. The lactulose traps the ammonia in the gut, and the laxative effect of the drug expels the ammonia from the colon. It is usually given orally but may be given as a retention enema or via a nasogastric (NG) tube. Antibiotics, such as neomycin sulfate, which are poorly absorbed from the GI tract, are given orally or rectally to reduce the bacterial flora of the colon, as bacterial action on protein in the faeces results in ammonia production. Cathartics and enemas are also used to decrease bacterial action. Constipation should be prevented. Because neomycin may cause renal toxicity and hearing impairments, lactulose is frequently the preferred drug.

Control of hepatic encephalopathy also involves treatment of the precipitating causes (Table 43-11). This involves controlling GI haemorrhage and removing the blood from the GI tract to decrease the protein in the intestine. Electrolyte disturbance, particularly hypokalaemia, and acid–base imbalances and infections should also be treated.

Liver transplantation may be considered in patients with recurring hepatic encephalopathy and end-stage liver disease. The use of liver transplantation depends on a number of factors, including the cause of the cirrhosis and other systemic medical problems.

Drug therapy

There is no specific drug therapy for cirrhosis. However, a number of drugs are used to treat the symptoms and complications of advanced liver disease (see Table 43-13).23

Nutritional therapy

The diet for the patient with cirrhosis without complications is high in energy (12,500 kJ per day), with high carbohydrate content and moderate-to-low fat levels. Previously, low-protein diets were routinely recommended for patients with cirrhosis in the hope of decreasing intestinal ammonia production and preventing the exacerbations of hepatic encephalopathy. However, the consequence was a worsening of pre-existing protein–energy malnutrition. Protein restriction may be appropriate in some patients immediately following a severe flare-up of symptoms (i.e. episodic hepatic encephalopathy). However, protein restriction is rarely justified in patients with cirrhosis and persistent hepatic encephalopathy. Indeed, malnutrition is a more serious clinical problem than hepatic encephalopathy for many of these patients.

Sufficient carbohydrate intake must be provided to maintain an intake of 6250–8300 kJ to prevent hypoglycaemia and catabolism. Glucose polymer (Polycose, Poly-Joule) is protein-free and can be used as a source of energy. It can be given orally or via an NG tube. The patient with alcoholic cirrhosis frequently has protein–energy malnutrition. For the patient with protein malnutrition, enteral formulas containing protein from branched-chain amino acids that are metabolised by the muscles are used. They provide protein but put less burden on the liver. Parenteral nutrition or enteral nutrition therapy may be required.

The patient with ascites and oedema is on a low-sodium diet. The degree of sodium restriction varies depending on the patient’s condition. The patient needs instruction regarding the degree of restriction. Table salt is the most common source of sodium. Sodium is also present in baking soda and baking powder. Foods high in sodium include canned soups and vegetables, salted snacks such as potato chips, nuts, smoked meats and fish, crackers, breads, olives, pickles, tomato sauce and beer.

Sodium is also present in many over-the-counter drugs (e.g. antacids). However, most antacids are now lower in sodium than previously. Carbonated beverages tend to be high in sodium, but low-sodium and sodium-free carbonated drinks are available. The patient should be advised to read food labels. Foods high in protein usually have large amounts of sodium. Alternative protein supplements that are low in sodium may have to be used. The patient and family need advice about ways to make the diet more palatable through the use of seasonings such as garlic, parsley, onion, lemon juice and spices.

NURSING MANAGEMENT: CIRRHOSIS

NURSING MANAGEMENT: CIRRHOSIS

Nursing assessment

Nursing assessment

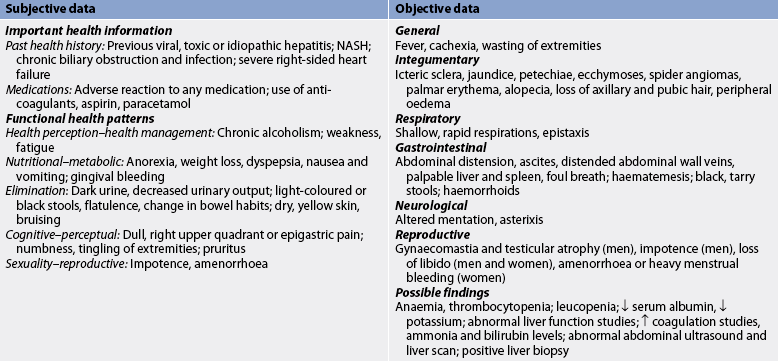

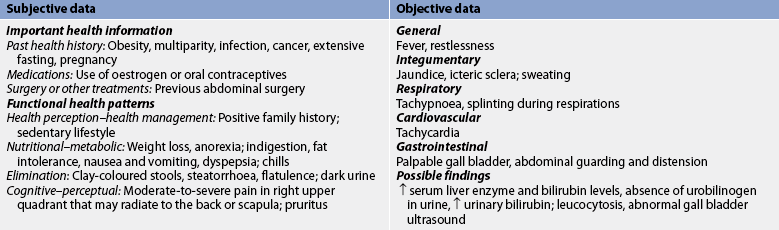

Subjective and objective data that should be obtained from the patient with cirrhosis are presented in Table 43-14.

Nursing diagnoses

Nursing diagnoses

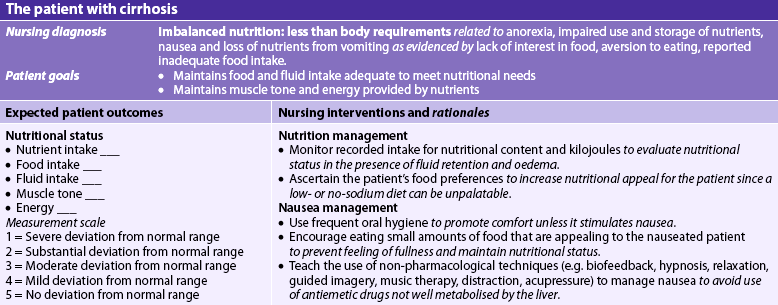

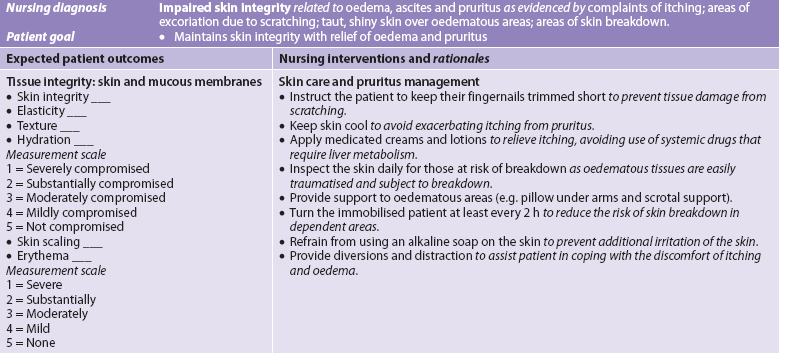

Nursing diagnoses for the patient with cirrhosis include, but are not limited to, those presented in NCP 43-2.

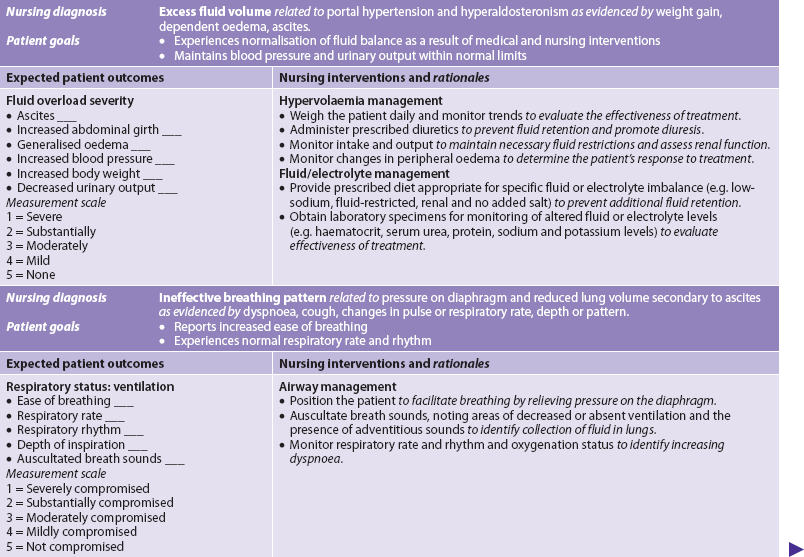

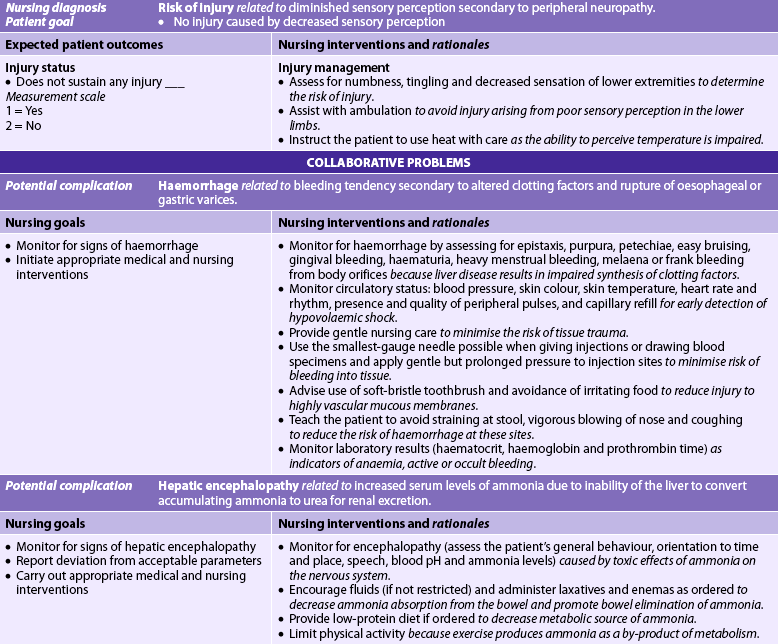

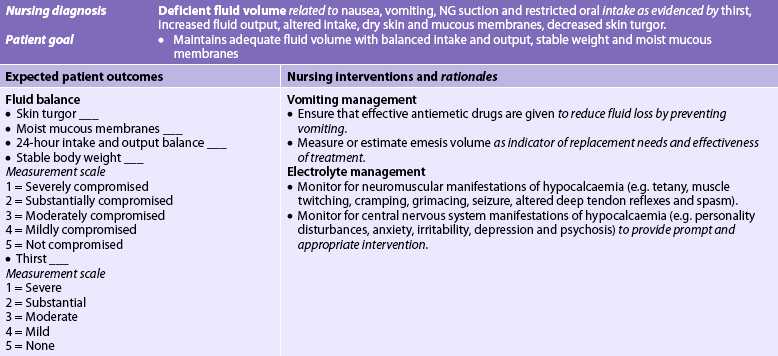

NURSING CARE PLAN 43-2 The patient with cirrhosis

Planning

Planning

The overall goals are that the patient with cirrhosis will: (1) have relief of discomfort; (2) have minimal to no complications (ascites, varices, hepatic encephalopathy); and (3) return to as normal a lifestyle as possible.

Nursing implementation

Nursing implementation

Health promotion

Health promotion

The common aetiologies of cirrhosis are alcohol abuse, malnutrition, hepatitis, biliary obstruction, obesity and right-sided heart failure. Prevention and early treatment of cirrhosis must focus on eliminating these risk factors. Alcoholism must be treated (see Ch 10). Patients should be urged to avoid alcohol ingestion and their efforts should be supported. Adequate nutrition, especially for the alcoholic and other individuals at risk of cirrhosis, is essential to promote liver regeneration. Acute hepatitis must be identified and treated early so that it does not progress to chronic hepatitis. Biliary disease must be treated so that the stones do not cause obstruction and infection. The underlying cause (e.g. chronic lung disease) of right-sided heart failure must be treated so that the heart failure does not lead to cirrhosis.

Acute intervention

Acute intervention

The focus of nursing care for the patient with cirrhosis is on conserving the patient’s strength (see NCP 43-2). Rest enables the liver to restore itself. Complete bed rest may not always be necessary. When the patient requires complete bed rest, measures to prevent pneumonia, thromboembolic problems and pressure ulcers should be taken. The activity and rest schedule may be modified according to signs of clinical improvement (e.g. decreasing jaundice, improvement in liver function studies). Major concerns for the nurse in determining appropriate nursing care measures to meet the need for rest involve regulation of the physical, emotional and social climate.

Anorexia, nausea and vomiting, pressure from ascites and poor eating habits all create problems in maintaining an adequate intake of nutrients. Oral hygiene before meals may improve the patient’s taste sensation. Between-meal nourishment should be available so that they can be provided at times when the patient can best tolerate them. Food preferences should be catered for whenever possible. The reason for any dietary restrictions should be explained to the patient and family.

Nursing assessment and care should include the patient’s physiological response to cirrhosis. The nurse assesses the sclera, skin or hard palate for jaundice and observes for progression of jaundice. If the jaundice is accompanied by pruritus, measures to relieve itching should be carried out. Cholestyramine may be ordered to help relieve the pruritus. Other measures to help alleviate pruritus include baking soda or Alpha Keri baths, applying lotions containing calamine, antihistamines and control of temperature (not too hot or cold). Patients should be taught to rub with their knuckles rather than scratch with their nails when they cannot resist scratching. The colour of the urine and stools should be noted. With jaundice the urine is often dark brown and foamy when shaken. The stool is grey or tan.

Oedema and ascites are frequent manifestations of cirrhosis and require nursing assessments and interventions. Accurate calculation and recording of intake and output, daily weights and measurements of extremities and abdominal girth help in the ongoing assessment of the location and extent of the oedema. If the patient can assume a kneeling position when abdominal girth measurement is taken, the abdominal fluid will go to the most dependent part of the abdomen. This gives the best measurement of abdominal girth. For many patients, however, the girth must be measured in the standing or lying position. Where the measurements are taken should be recorded and should be a part of the nursing care plan.

When a paracentesis is done, the nurse must have the patient void immediately before the procedure to prevent puncture of the bladder. The patient should sit on the side of the bed or be placed in the high-Fowler position. Following the procedure the nurse should monitor for hypovolaemia and electrolyte imbalances and check the dressing for bleeding and leakage.

Dyspnoea is a frequent problem for the patient with ascites. A semi-Fowler or Fowler position allows for maximal respiratory efficiency. Pillows can be used to support the arms and chest and may increase the patient’s comfort and ability to breathe.

Meticulous skin care is essential because the oedematous tissues are subject to breakdown. An alternating air pressure mattress or other special mattress should be used. A turning schedule (minimum of every 2 hours) must be adhered to rigidly. The abdomen may be supported with pillows. If the abdomen is taut, cleansing must be done very gently. The patient tends to move very little because of the abdominal discomfort and dyspnoea; therefore, range-of-motion exercises are helpful, and measures such as coughing and deep breathing should be implemented to prevent respiratory problems. The lower extremities may be elevated. If scrotal oedema is present, a scrotal support provides some comfort.

When the patient is taking diuretics, the serum levels of sodium, potassium, chloride and bicarbonate should be monitored. The patient should be observed for signs of fluid and electrolyte imbalance, especially hypokalaemia. Hypokalaemia may be manifested by cardiac arrhythmias, hypotension, tachycardia and generalised muscle weakness. Water excess is manifested by muscle cramping, weakness, lethargy and confusion.

Observations and nursing care in relation to haematological disorders (bleeding tendencies, anaemia, increased susceptibility to infection) are the same as for the patient with advanced liver disease (NCP 43-2).

The nurse must assess the patient’s response to altered body image resulting from jaundice, spider angiomas, palmar erythema, ascites and gynaecomastia. The patient may experience a great deal of anxiety regarding these changes. The nurse should explain these phenomena and be a supportive listener. Providing nursing care with concern and warmth, regardless of the patient’s physical changes, helps the patient to maintain self-esteem.

Bleeding varices

Bleeding varices

If the patient has oesophageal/gastric varices in addition to cirrhosis, the nurse must observe for any signs of bleeding from the varices, such as haematemesis and melaena. If bleeding occurs, the nurse should notify the doctor and be ready to assist with whatever treatment is used to control the bleeding. The patient’s airway must be maintained. To stop the bleeding, ligation or sclerotherapy procedures may be performed.

Balloon tamponade is not used as first-line therapy for bleeding varices. However, it is used in those patients who have refractory bleeding that is unresponsive to sclerotherapy or ligation. When balloon tamponade is used, the initial nursing task related to insertion of the tube is to explain the use of the tube and how it will be inserted. Prior to insertion the balloons should be checked for patency and the pressures recorded at each 50 mL of inflation. It is usually the doctor’s responsibility to insert the tube. It may be inserted via the nose or the mouth (see Fig 43-10). The gastric balloon is inflated with approximately 250 mL of air and the tube is retracted until resistance at the gastro-oesophageal junction is felt. The tube is secured by placing a piece of sponge or foam rubber at the nostrils (nasal cuff). For continued bleeding the oesophageal balloon is then inflated. A sphygmomanometer is used to measure the desired pressure, which is then maintained at 20–40 mmHg. The position of the balloon is verified by X-ray.

Lavage may be used to remove blood from the stomach. (Nursing care of upper GI bleeding is discussed in Ch 41.) This helps prevent the blood from degrading to ammonia, leading to encephalopathy. The gastric lumen should have continual free drainage between lavages. The oesophageal balloon should be deflated every 8–12 hours to avoid necrosis. The oesophageal lumen should be connected to low-pressure suction to remove secretions to reduce the risk of aspiration. The most common complication of balloon tamponade therapy is aspiration pneumonia.

Nursing care includes monitoring for occlusion of the airway by the balloon. If the gastric balloon breaks or is deflated, the oesophageal balloon will slip upwards, obstructing the airway and causing asphyxiation. If this happens, the nurse must cut the tube or deflate the oesophageal balloon. Scissors should be kept at the bedside. Regurgitation can be minimised by oral and pharyngeal suctioning and by keeping the patient in a semi-Fowler position.

The patient is unable to swallow saliva because of the inflated oesophageal balloon occluding the oesophagus. The oesophageal aspiration lumen drains any swallowed secretions, and the nurse should encourage the conscious patient to expectorate any secretions pooling in their pharynx. Frequent oral and nasal care provides the patient with relief from the taste of blood and from irritation as a result of mouth breathing.

Short-term release of traction on the tube is necessary to avoid necrosis from pressure of the traction fixation at the nares. The nurse should be aware, however, that with traction release, bleeding may recur.

Hepatic encephalopathy

Hepatic encephalopathy

The focus of nursing care for the patient with hepatic encephalopathy is on sustaining life and assisting with measures to reduce the formation of ammonia. The nurse should assess: (1) the patient’s level of responsiveness (e.g. reflexes, pupillary reactions, orientation); (2) sensory and motor abnormalities (e.g. hyperreflexia, asterixis, motor coordination); (3) fluid and electrolyte imbalances; (4) acid–base imbalances; and (5) the effect of treatment measures.

The patient’s neurological status, including an exact description of the patient’s behaviour, should be assessed and recorded at least every 2 hours. Care of the patient with neurological problems should be based on the severity of the encephalopathy.

Nursing measures to prevent constipation should be instituted to decrease ammonia production. Drugs, laxatives and enemas should be given as ordered. Encouraging the patient to take fluids may also help if not contraindicated. The patient should not strain at stool because this may cause bleeding of haemorrhoids or rectal varices. Any GI bleeding may worsen the encephalopathy. The patient who is taking lactulose should be assessed for excessive fluid and electrolyte losses from the diarrhoea, which is the treatment goal.

Factors that are known to precipitate coma should be controlled as much as possible. Because exercise produces ammonia as a by-product of metabolism, the patient’s physical activity must be limited. Hypokalaemia should be controlled.

Nutrition is an important consideration in the patient with cirrhosis. Foods and fluids high in carbohydrate should be given because the liver is not synthesising and storing glucose. The patient may require tube feedings if an adequate diet cannot be ingested.

Ambulatory and home care

Ambulatory and home care

The patient with cirrhosis may be faced with a prolonged course of treatment and the possibility of serious, life-threatening problems and complications. The nurse should act as a resource to help the patient achieve the highest possible level of wellness. The patient and family need to understand the importance of continuous healthcare and medical supervision. They should be taught symptoms of complications and when to seek medical attention. Patients should avoid activities that place them at risk of contracting viral hepatitis.

Measures to diminish the impact of cirrhosis should be encouraged. These include proper diet, rest, avoiding potentially hepatotoxic over-the-counter drugs such as paracetamol, and abstinence from alcohol. Abstinence from alcohol is important and results in improvement in most patients. The nurse must realise the difficulty this poses for some patients. The nurse’s own attitude towards patients whose cirrhosis is attributed to alcohol abuse should be explored. Care should be given without rejection and moralising (see Ch 10).

Cirrhosis is a chronic disease. The patient is affected not only physically but also psychologically, socially and economically. Major adjustments may be required to make lifestyle changes, especially if alcohol abuse is the primary aetiological factor. The nurse should refer the patient to the Drug and Alcohol Service if available, and provide information about community support programs, such as Alcoholics Anonymous, for help with alcohol abuse.

The nurse should give the patient and family adequate verbal and written explanations about fluid or dietary restrictions (see Box 43-3). Other health teaching should include instruction about adequate rest periods, how to detect early signs of complications, skin care, drug therapy precautions, observation for bleeding and protection from infection. Counselling information regarding sexual problems may be needed. Referral to a community nurse may be helpful to ensure adequate patient compliance with prescribed therapy. The emphasis of home care for patients with cirrhosis should be on helping them to maintain the highest level of wellness possible and encouraging them to maintain necessary lifestyle changes.

BOX 43-3 Cirrhosis

PATIENT & FAMILY TEACHING GUIDE

1. Explain to the patient and family that cirrhosis is a chronic illness and the importance of continuous healthcare.

2. Teach the patient and family the symptoms of complications and when to seek medical attention to enable prompt treatment of complications.

3. Provide instruction on a high-carbohydrate, moderate-to-low-fat diet with low sodium and/or protein restriction if specifically required by the dietician.

4. Teach the patient to avoid potentially hepatotoxic over-the-counter drugs (see Box 38-1) because the diseased liver is unable to metabolise these drugs.

5. Encourage abstinence from alcohol because continued use of alcohol will increase the risk of liver complications.

6. Instruct the patient to avoid aspirin and non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs to prevent haemorrhage when oesophageal or gastric varices are present.

7. Teach the patient to avoid spicy and rough foods, as well as activities that increase portal pressure, such as straining at stool, coughing, sneezing, and retching and vomiting, because haemorrhage is a danger as a result of the inability of the liver to produce clotting factors.

Evaluation

Evaluation

Expected outcomes for the patient with cirrhosis are addressed in NCP 43-2.

Fulminant hepatic failure

Fulminant hepatic failure is a clinical syndrome characterised by the rapid onset of severe impairment of liver function associated with hepatic encephalopathy in a patient with no prior history of liver disease. In fulminant hepatic failure the encephalopathy occurs within 8 weeks of the first symptoms. With intensive support, survival rates range from 10% to 40%.

The most common cause is viral hepatitis, in particular HBV, but it may also occur with HAV and less frequently with HCV. Drugs are the second most common cause. Paracetamol in combination with alcohol is a common offending agent, and those who abuse alcohol are particularly susceptible to the detrimental effects of paracetamol on the liver. Other drugs that can cause fulminant hepatitis include include isoniazid, halothane, sulfur-containing drugs and non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs). Drugs can cause liver cell failure by disrupting essential intracellular processes or by causing an accumulation of toxic metabolic products. Mushroom poisoning is also associated with fulminant liver failure. The majority of mushroom poisonings occur with Amanita phalloides (also known as ‘death cap’). Another condition that may present with fulminant hepatic failure is Wilson’s disease.

CLINICAL MANIFESTATIONS AND DIAGNOSTIC STUDIES

Manifestations include jaundice, coagulation abnormalities and encephalopathy. In acute liver failure, changes in mentation are the first clinical sign. Patients with acute liver failure are susceptible to a wide variety of complications. These include cerebral oedema, renal failure, hypoglycaemia, metabolic acidosis, sepsis and multi-organ failure.

Fulminant liver failure is identified in most patients by laboratory abnormalities and clinical manifestations as a result of hepatic necrosis and fibrosis. Most often serum bilirubin levels are elevated and the prothrombin time is prolonged. Liver enzyme (AST, ALT) levels are often markedly elevated. Additional laboratory tests include blood chemistries (especially glucose, as hypoglycaemia may be present and require correction), full blood count (FBC), paracetamol level and screening for other drugs and toxins, viral hepatitis serologies (especially HAV and HBV), total serum copper, serum caeruloplasmin levels and autoantibodies (antinuclear and antismooth muscle antibodies). Plasma ammonia levels may also be obtained.

A liver biopsy, most often done via the transjugular route because of coagulopathy, will provide tissue diagnosis. In addition, ultrasound and CT or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) are helpful in providing information about the liver size and contour, the presence of ascites and tumours and the patency of the blood vessels.

MULTIDISCIPLINARY CARE

Since fulminant hepatic failure may progress rapidly, with changes in consciousness occurring hour by hour, early transfer to the intensive care unit (ICU) is preferred once the diagnosis is made. Planning for transfer to a transplant centre should begin in patients with grade 1 or 2 encephalopathy because they may worsen rapidly. Early transfer is important as the risks involved with patient transport may increase or even preclude transfer once stage 3 or 4 encephalopathy develops.

Acute kidney injury and chronic renal failure are frequent complications in patients with liver failure and may be due to dehydration, hepatorenal syndrome or acute tubular necrosis. The frequency of renal failure may be even greater with paracetamol overdose or other toxins, where direct renal toxicity occurs. Although few patients die of renal failure alone, it often contributes to mortality and may predict a poorer prognosis. Efforts should be made to protect renal function by maintaining adequate haemodynamic status, avoiding nephrotoxic agents such as aminoglycosides and NSAIDs, and promptly identifying and treating infection.

Liver transplantation is the treatment of choice for fulminant liver failure. Liver transplant increases survival in 50–85% of patients with acute liver failure. Cerebral oedema, followed by cerebellar herniation and brainstem compression, is the most common cause of death. Treatment of cerebral oedema is described in Chapter 56.

NURSING MANAGEMENT: FULMINANT HEPATIC FAILURE

NURSING MANAGEMENT: FULMINANT HEPATIC FAILURE

Patients with mild (grade 1 or 2) encephalopathy may be safely managed in a general medical–surgical unit. Frequent mental status checks should be performed and the patient should be transferred to ICU if their level of consciousness declines. A quiet environment should be provided to minimise agitation. Additional measures include padding the bedrails to avoid injury due to possible seizures, moving the patient closer to the nursing station for close observation to avoid falls or injuries, monitoring intake and output for renal function, and providing good skin and oral care to avoid breakdown and infection.

As the patient progresses to grade 3 or 4 encephalopathy it is advisable to intubate them to maintain a patent airway. Monitoring and management of haemodynamic and renal parameters, as well as glucose, electrolytes and acid–base status, becomes critical. Frequent neurological evaluation should be conducted for signs of elevated intracranial pressure (ICP). The patient should be positioned with the head elevated at 30°. Efforts should be made to avoid patient stimulation. Manoeuvres that cause straining or Valsalva-like movements may increase ICP. It may be advisable to use endotracheal lignocaine prior to endotracheal suctioning. The use of any sedatives is discouraged due to their effects on the evaluation of mental status. Only minimal doses of benzodiazepines should be used due to their delayed metabolism by the failing liver. ICP should be maintained below 20–25 mmHg if possible, with cerebral perfusion pressure (CPP) maintained above 50–60 mmHg. Support of systemic blood pressure may be required to maintain adequate CPP.

Liver cancer

Primary liver cancer (originating in the liver) is the fourth most common cancer worldwide; risk factors include cirrhosis and chronic hepatitis, especially HBV. The annual incidence of liver cancer in Australia is 1060, with a male predominance.24 In New Zealand, the annual incidence is 237, again with a higher incidence in men.25 Hepatocellular carcinoma is the most common primary liver cancer; the remaining primary tumours are cholangiomas and bile duct carcinomas. About 80% of people with primary cell carcinoma have cirrhosis of the liver. Cirrhosis is a risk factor regardless of the cause of the cirrhosis. Hepatitis C infection is responsible for about 50–60% of all liver cancers and hepatitis B is responsible for approximately 20%. The incidence of liver cancer is increasing. Liver cancer is very rare in persons under the age of 40. Metastatic carcinoma of the liver is more common than primary carcinoma. The liver is a common site of metastatic growth because of its high rate of blood flow and extensive capillary network. Cancer cells in other parts of the body are commonly carried to the liver via the portal circulation.

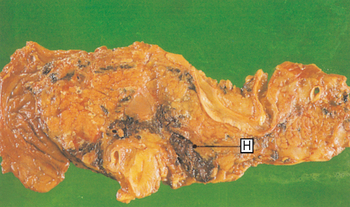

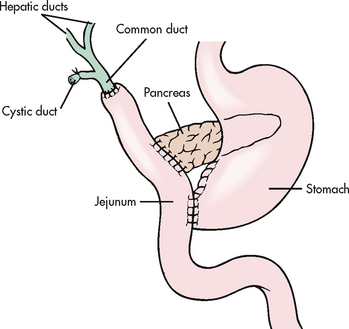

The malignant cells cause the liver to be enlarged and misshapen. Haemorrhage and necrosis in the liver are common. Lesions may be singular or numerous and nodular or diffusely spread over the entire liver (see Fig 43-13). Some tumours infiltrate into other organs, such as the gall bladder, or into the peritoneum or diaphragm. Primary liver tumours commonly metastasise to the lungs.

CLINICAL MANIFESTATIONS AND DIAGNOSTIC STUDIES

It is difficult to diagnose liver cancer. It is particularly difficult to differentiate it from cirrhosis in its early stages because many of the clinical manifestations (e.g. hepatomegaly, weight loss, peripheral oedema, ascites, portal hypertension) are similar. Other common manifestations include dull abdominal pain in the epigastric or right upper quadrant region, jaundice, anorexia, nausea and vomiting, and extreme weakness. Patients frequently have pulmonary emboli and portal vein thrombosis. Tests used to assist in the diagnosis are a liver scan (CT or MRI), hepatic angiography, endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) and a liver biopsy (usually laparoscopically). The test for α-fetoprotein (AFP) may be positive in hepato-cellular carcinoma. AFP is elevated in approximately 50–75% of patients with hepatocellular carcinoma and helps to distinguish primary cancer from metastatic cancer. (AFP is discussed in Ch 15.)

NURSING AND COLLABORATIVE MANAGEMENT: LIVER CANCER

NURSING AND COLLABORATIVE MANAGEMENT: LIVER CANCER

Prevention of liver cancer is focused on identification and treatment of chronic viral hepatitis (B and C). Treatment of chronic alcohol ingestion may also lower the risk of liver cancer.

Treatment of liver cancer depends on the size and number of tumours, the presence of spread beyond the liver, and the age and overall health of the patient. Surgical excision (lobectomy) is sometimes performed if the tumour is localised to one portion of the liver. However, only about 15% of patients have surgically resectable disease because the cancer is usually too far advanced when it is detected. Surgical excision of the entire tumour offers the best chance for cure of liver cancer. Other treatment options are ablation with radiofrequency, cryosurgery, alcohol injection, chemotherapy and/or chemoembolisation, and liver transplantation.

In radiofrequency treatment, a thin needle is inserted through the skin and into the core of the tumour, then electrical energy is used to create heat in a specific location for a limited amount of time. The end result is destruction of tumour cells. This procedure can be done percutaneously, laparoscopically or through an open incision. This therapy, while not ideal for all patients, can be used for tumours that are considered resectable as well as for palliative purposes. Complications are not common but can include infection, bleeding, arrhythmias and skin burn.

Cryosurgery is used for patients whose tumours are considered unresectable but who do not have signs of metastasis. Cryosurgery involves an open surgical approach. Cryoprobes are placed directly into the liver and liquid nitrogen/argon gas flows through the probe and freezes the liver tissue. The tissue in the area surrounding the probe is destroyed. Cryosurgery is not used for metastatic liver disease.

Percutaneous ethanol injection (PEI) and percutaneous acetic acid injection (PAI) are also used to treat unresectable liver cancer that has not metastasised outside the liver. This is an outpatient procedure in which a catheter is guided to the liver using ultrasound. Ethanol or acetic acid is injected for six to eight treatments over a 3–4 week period, with two to three injections each week. The most common side effect is transient pain following the procedure. Other, less frequent adverse events include intraperitoneal haemorrhage, hepatic insufficiency, bile duct necrosis, hepatic infarction and transient hypotension.

Chemotherapy is used for patients with hepatocellular cancer who are not likely to benefit from other procedures (e.g. surgery, transplantation, ablation). Sorafenib, a targeted therapy, is used to treat metastatic liver cancer. It inhibits tyrosine kinases, some of which are involved in promoting new blood vessel growth to tumours.

Chemoembolisation is a minimally invasive procedure frequently performed in the interventional radiology department. In this procedure a catheter is placed in the arteries to the tumour and an embolic agent is administered, often mixed with a chemotherapeutic agent(s). The embolic agent reduces the blood supply, thus allowing greater exposure of liver cells to the chemotherapy drugs.

Liver transplantation is an option for patients with liver cancer that has not spread beyond the liver.

Nursing intervention for the patient with liver cancer focuses on keeping the patient as comfortable as possible. Because this patient manifests the same problems as any patient with advanced liver disease, the nursing interventions discussed for cirrhosis of the liver apply. (See also Ch 15 for care of the patient with cancer.) The prognosis for patients with liver cancer is poor. The cancer grows rapidly and death may occur within 4–7 months as a result of hepatic encephalopathy or massive blood loss from GI bleeding.

Liver transplantation

The first human liver transplant was performed in 1963 at the University of Colorado by Thomas Starzl. The first liver transplant in Australasia was performed in 1985 at the Princess Alexandra Hospital in Brisbane. Liver transplantation has become a practical therapeutic option for many people with irreversible liver disease. It improves the quality of life for end-stage liver disease patients and is an accepted treatment modality for these patients. Indications for liver transplantation include congenital biliary abnormalities, inborn errors of metabolism, hepatic malignancy (confined to the liver), sclerosing cholangitis, fulminant hepatic failure and chronic end-stage liver disease. Liver disease related to chronic viral hepatitis is the leading indication for liver transplantation. Liver transplants are not recommended for patients with widespread malignant disease.

Liver transplant candidates must go through a rigorous presurgery screening. This is done to confirm the diagnosis of end-stage liver disease as well as to assess for other coexisting conditions (e.g. cardiovascular disease, chronic kidney disease) that may affect the patient’s surgical outcome. The evaluation includes physical examination, laboratory tests (FBC, liver function tests), haemochromatosis evaluation, echocardiogram, endoscopy, liver ultrasound, CT scan and psychological testing. Potential recipients should receive counselling regarding cigarette smoking and alcohol abstinence. Contraindications for liver transplant include severe pulmonary hypertension, morbid obesity and obstructed splanchnic blood flow.

Liver transplantation is performed using deceased (cadaver) as well as live donor livers. The live liver donor transplant was developed initially for children whose parents wanted to serve as donors. Today, liver transplant centres are performing live liver transplant procedures for adults. The advantages of live organ donation include minimal cold ischaemia time for the donated liver. Live liver donation does, however, pose a risk for the donor due to the vascularity of the liver, as splitting the liver causes more potential risk of bleeding. Potential complications for the donor include biliary problems, hepatic artery thrombosis, wound infection, postoperative ileus and pneumothorax.

Many patients die each year while waiting for a liver transplant. Because of the scarcity of available livers, a donor liver may be divided into two parts (split liver transplant). This allows the liver to be implanted into two recipients. The decision to use a split donor liver is based on the size and health of the donor. The recipients of the split liver generally need to be smaller than the donor. The disadvantage of the split liver procedure is that the recipients receive less liver tissue (one receives 60% of the liver and the other 40%). The success rate associated with split liver transplant is somewhat less successful (e.g. more complications such as bleeding) compared to whole organ transplantation.

The major postoperative complications include bleeding, rejection and infection. Rejection is not as frequent a problem as it is in kidney transplants. The liver seems to be less susceptible to rejection than the kidneys. The use of cyclosporin as an immunosuppressant drug has been a major factor in the success rates of liver transplantation. The mechanism of action and side effects of cyclosporin are discussed in Chapter 13. This drug does not cause bone marrow suppression and it does not impede wound healing. Other immunosuppressants used include azathioprine, corticosteroids, the monoclonal antibody OKT3, the interleukin-2 receptor antagonist basiliximab and the calcineurin inhibitors tacrolimus, mycophenolate mofetil and sirolimus. These may all be used in combination with other immunosuppressive agents to reduce rejection. Other factors in the improved success rate are advances in surgical techniques, better selection of potential recipients and improved management of the underlying liver disease before surgery.

Gerontological considerations: liver disease in the older adult

The incidence of liver diseases increases with age. With ageing there is a decrease in liver volume, a decrease in drug metabolism and altered hepatobiliary function.26 The liver also has a decreased ability to respond to injury, in particular to regenerate following injury. Transplanted livers take longer to regenerate in the older adult as compared to the younger adult.

Older patients are particularly vulnerable to drug-induced hepatitis. This is due to several factors, including the increased use of prescription and over-the-counter drugs, which can lead to drug interactions and potential drug toxicity. Age-related decreases in liver function caused by decreased liver blood flow and enzyme activity result in decreased drug metabolism. In addition, with ageing the liver has a decreased ability to recover from drug-induced injury.

A growing number of older adults have chronic hepatitis C and subsequent cirrhosis.27 The presence of HCV and elevated liver enzyme levels may be found during a routine health assessment. Drug therapy for HCV has been shown to be less effective in older adults. Because older adults have more coexisting conditions, liver transplant following liver failure may not be an option. The older adult undergoing haemodialysis is at risk for exposure to both HCV and HBV.

Lifetime health behaviours may also influence the development of chronic liver disease in the older adult. Chronic alcohol abuse and obesity can contribute to cirrhosis and liver inflammation (NASH) and subsequent liver failure. Due to coexisting cardiovascular and pulmonary diseases, the older adult is less able to tolerate variceal bleeding. In the older adult with liver disease, hepatic encephalopathy may be misdiagnosed as dementia.

Approximately 75% of patients survive more than 3 years following liver transplant. Long-term survival following liver transplantation depends on the cause of liver failure (e.g. localised liver cancer, hepatitis B or C, biliary disease). Patients who have liver disease secondary to viral hepatitis often experience reinfection of the transplanted liver with hepatitis B or C. For patients with HBV, treatment postsurgery with HBIG and α-interferon has reduced the rates of reinfection of the graft. HCV recurrence, as evidenced by histological damage, is almost universal after transplant. Patients with HCV have lower survival rates when compared to other patient groups. Factors that contribute to recurrent HCV include the advanced age of the donor, HCV genotype 1, high HCV-RNA levels prior to the transplant and co-infection with other viruses (e.g. cytomegalovirus). Antiviral therapy for HCV initiated post-transplant has failed to alter this recurrence pattern and such therapy is frequently limited because of adverse effects. As a result, antiviral therapy post-transplant is initiated on an individual basis.

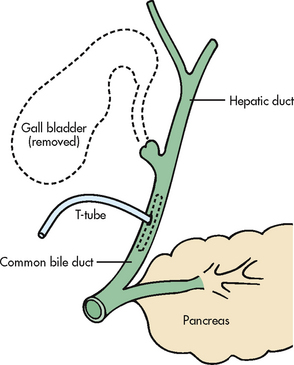

The patient who has had a liver transplant requires competent and highly skilled nursing care, either in an ICU or in some other specialised unit. Postoperative nursing care includes assessing neurological status; monitoring for signs of haemorrhage; preventing pulmonary complications; monitoring drainage, electrolyte levels and urinary output; and monitoring for signs and symptoms of infection and rejection. Common respiratory problems are pneumonia, atelectasis and pleural effusions. The patient should use measures such as coughing, deep breathing, incentive spirometry and repositioning to prevent these complications. Drainage from the Jackson-Pratt drain, NG tube and T tube should be measured, and the colour and consistency of drainage noted. The first 2 months after surgery are critical for monitoring for infection. Infection can be viral, fungal or bacterial. Fever may be the only sign of infection. Emotional support and teaching of both the patient and family are essential.

DISORDERS OF THE PANCREAS

Acute pancreatitis

Acute pancreatitis is an acute inflammatory process of the pancreas. The degree of inflammation varies from mild oedema to severe haemorrhagic necrosis. Acute pancreatitis is most common in middle-aged men and women. The severity of the disease varies according to the extent of pancreatic destruction. Some patients recover completely, while others have recurring attacks and yet others develop chronic pancreatitis. Acute pancreatitis can be life-threatening.

AETIOLOGY AND PATHOPHYSIOLOGY

Many factors can cause injury to the pancreas. The majority of cases of pancreatitis are caused by gallstones and alcohol abuse. Other, less common causes of acute pancreatitis include trauma (postsurgical, abdominal), viral infections (mumps, coxsackievirus B, HIV), penetrating duodenal ulcer, cysts, abscesses, cystic fibrosis, Kaposi’s sarcoma, certain drugs (corticosteroids, thiazide diuretics, oral contraceptives, sulfonamides, NSAIDs), metabolic disorders (hyperparathyroidism, renal failure) and vascular diseases. Pancreatitis may occur after surgical procedures on the pancreas, stomach, duodenum or biliary tract. It can also occur after endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatogram (ERCP), an investigative procedure. In some cases the cause is not known (idiopathic). Hereditary pancreatitis is an unusual cause of acute pancreatitis and may progress to chronic pancreatitis.

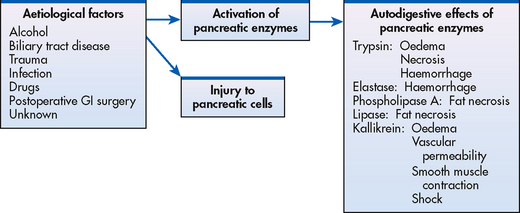

The most common pathogenic mechanism is believed to be autodigestion of the pancreas (see Fig 43-14). The aetiological factors cause injury to pancreatic cells or activation of the pancreatic enzymes in the pancreas rather than in the intestine. It is not clear how the activation of pancreatic enzymes occurs. One possible cause could be reflux of bile acids into the pancreatic ducts through an open or distended sphincter of Oddi. The reflux may occur because of gallstones impacted at the ampulla of Vater, atony and oedema of the sphincter, or obstruction of pancreatic ducts and pancreatic ischaemia.

Trypsinogen is an inactive proteolytic enzyme produced by the pancreas. Normally it is released into the small intestine via the pancreatic duct. In the intestine it is activated to trypsin by enterokinase. Trypsin inhibitors in the pancreas and plasma bind and inactivate any trypsin that is inadvertently produced. In pancreatitis, activated trypsin is present in the pancreas. This enzyme can digest the pancreas and activate other proteolytic enzymes, such as elastase and phospholipase. Elastase and phospholipase A play major roles in autodigestion of the pancreas. Elastase causes haemorrhage by producing dissolution of the elastic fibres of blood vessels. Phospholipase A is probably activated by trypsin and bile acids and causes fat necrosis.

The exact mechanism by which chronic alcohol intake predisposes to pancreatitis is not known. It is thought that alcohol increases the production of digestive enzymes in the pancreas and/or increases the sensitivity to the hormone cholecystokinin (CCK). CCK stimulates the production of pancreatic enzymes. Only 5–10% of chronic alcohol abusers develop pancreatitis. This suggests that environmental and genetic factors may also contribute.

The pathophysiological involvement of acute pancreatitis ranges from oedematous pancreatitis (which is mild and self-limiting) to necrotising pancreatitis (in which the degree of necrosis correlates with the severity of manifestations) (see Fig 43-15). In necrotising pancreatitis permanent decreases in endocrine and exocrine function occur in approximately half of all patients. Those patients with severe pancreatitis are also at high risk of developing pancreatic necrosis, organ failure and septic complications, resulting in a 25% mortality rate.

CLINICAL MANIFESTATIONS

Abdominal pain is the predominant symptom of acute pancreatitis. The pain is usually located in the left upper quadrant but it may be in the mid-epigastrium. It commonly radiates to the back because of the retroperitoneal location of the pancreas. The pain has a sudden onset and is described as severe, deep, piercing and continuous or steady. It is aggravated by eating and frequently has its onset when the patient is recumbent. It is not relieved by vomiting. The pain may be accompanied by flushing, cyanosis and dyspnoea. The patient may assume various positions involving flexion of the spine in an attempt to relieve the severe pain. The pain is due to distension of the pancreas, peritoneal irritation and obstruction of the biliary tract.

Other manifestations of acute pancreatitis include nausea and vomiting, low-grade fever, leucocytosis, hypotension, tachycardia and jaundice. Abdominal tenderness with muscle guarding is common. Bowel sounds may be decreased or absent. Ileus may occur and causes marked abdominal distension. The lungs are frequently involved, with crackles present. Intravascular damage from circulating trypsin may cause areas of cyanosis or greenish to yellow–brown discolouration of the abdominal wall. Other areas of ecchymoses are the flanks (Grey Turner’s spots or sign, a bluish flank discolouration) and the periumbilical area (Cullen’s sign, a bluish periumbilical discolouration), which result from seepage of bloodstained exudate from the pancreas and may occur in severe cases.

Shock may occur because of haemorrhage into the pancreas or toxaemia due to activated pancreatic enzymes. Hypovolaemia occurs as a result of fluid shift into the retroperitoneal space.

COMPLICATIONS

Two significant local complications of acute pancreatitis are pseudocyst and abscess. A pancreatic pseudocyst is a cavity continuous with or surrounding the outside of the pancreas. The pseudocyst is filled with necrotic products and liquid secretions, such as plasma, pancreatic enzymes and inflammatory exudates. As pancreatic enzymes escape, the serosal surfaces next to the pancreas become inflamed, with subsequent formation of granulation tissue leading to encapsulation of the exudate. Manifestations of pseudocyst are abdominal pain, palpable epigastric mass, nausea, vomiting and anorexia. The serum amylase level frequently remains elevated. These pseudocysts usually resolve spontaneously within a few weeks but may perforate, causing peritonitis, or rupture into the stomach or duodenum. Treatment consists of an internal drainage procedure with an anastomosis between the pancreatic duct and the jejunum. Endoscopic drainage may be achieved by placement of a stent between the jejunum and the pseudocyst.

A pancreatic abscess is a large fluid-containing cavity within the pancreas. It results from extensive necrosis in the pancreas. It may become infected or perforate into adjacent organs. Manifestations of an abscess include upper abdominal pain, abdominal mass, high fever and leucocytosis. Pancreatic abscesses require prompt surgical drainage to prevent sepsis.

The main systemic complications of acute pancreatitis are pulmonary (pleural effusion, atelectasis and pneumonia) and cardiovascular (hypotension) complications and tetany caused by hypocalcaemia. The pulmonary complications are probably caused by the passage of the exudate containing pancreatic enzymes from the peritoneal cavity through transdiaphragmatic lymph channels. Enzyme-induced inflammation of the diaphragm occurs with an end result being atelectasis caused by reduced diaphragm movement. Trypsin can activate prothrombin and plasminogen, increasing the patient’s risk of intravascular thrombi, pulmonary emboli and disseminated intravascular coagulation. When hypocalcaemia occurs, it is a sign of severe disease. It is due, in part, to the combining of calcium and fatty acids during fat necrosis. The exact mechanisms of how or why hypocalcaemia occurs are not well understood.

DIAGNOSTIC STUDIES

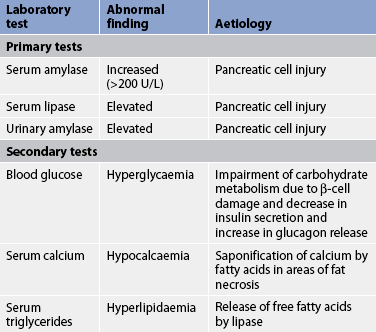

The primary diagnostic tests for acute pancreatitis are serum amylase and lipase levels and urinary amylase levels (see Table 43-15). The serum amylase level is usually elevated early and remains elevated for 24–72 hours. The serum lipase level is also elevated in acute pancreatitis and is a helpful complementary test because other disorders (e.g. mumps, cerebral trauma, renal transplantation) may also cause an increase in serum amylase level. The serum lipase level may be especially useful in patients with alcohol-induced acute pancreatitis.28

There is an increase in the urinary amylase level, which may persist several days beyond the elevation of the serum amylase level. Normally, a timed collection (e.g. a 2 hour collection) is a more dependable measure than a randomly collected urinary specimen. The renal amylase–creatinine clearance test estimates the amount of blood cleared of amylase by the kidney per minute. Urinary strip tests for trypsinogen activation peptide (TAP) and trypsinogen-2 provide a reliable early diagnosis of acute pancreatitis.28

Other laboratory abnormalities include hyperglycaemia, hyperlipidaemia and hypocalcaemia. There is a high incidence of hyperlipidaemia with recurrent pancreatitis.

Diagnostic evaluation of acute pancreatitis is also directed at determining the cause. An abdominal ultrasound, X-ray or contrast-enhanced CT scan can be used to identify pancreatic problems. The CT scan is the best diagnostic imaging test to determine the presence of pseudocysts and abscesses. ERCP is the definitive diagnostic test for gallstones. Endoscopic ultrasound (EUS) and magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography (MRCP) are being used with greater frequency.

MULTIDISCIPLINARY CARE

Objectives of multidisciplinary care for acute pancreatitis include: (1) relief of pain; (2) prevention or alleviation of shock; (3) reduction of pancreatic secretions; (4) correction of fluid and electrolyte imbalance; (5) prevention or treatment of infections; and (6) removal of the precipitating cause, if possible (see Box 43-4).

BOX 43-4 Acute pancreatitis

MULTIDISCIPLINARY CARE

DIAGNOSTIC STUDIES

History and physical examination

Serum amylase

Serum lipase

2-hour urinary amylase and renal amylase clearance

Blood glucose

Serum calcium

Triglycerides

Flat X-ray of the abdomen

Abdominal ultrasound

Endoscopic ultrasound

CT scan of the pancreas

Magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography

Endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography

Chest X-rays

Collaborative therapy

Pain medication (fentanyl, morphine)

NBM with NG tube connected to low-pressure suction

Albumin (if shock present)

IV calcium gluconate (10%) (if tetany present)

Hartmann’s solution

Omeprazole

Antibiotics (if necrotising pancreatitis)

CT, computed tomography; IV, intravenous; NBM, nil by mouth; NG, nasogastric.

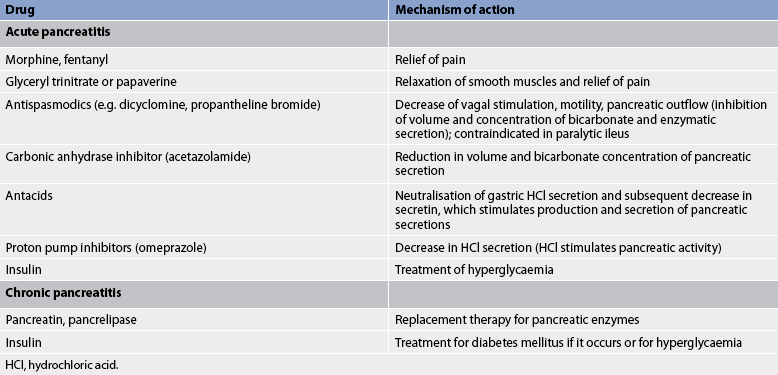

Conservative therapy

Treatment is principally focused on supportive care, including aggressive hydration, pain management, management of metabolic complications and minimising pancreatic stimulation. A primary consideration in the treatment of acute pancreatitis is the relief and control of pain. IV morphine or fentanyl by continuous infusion or patient-controlled administration (PCA) is used. Pain medications may be combined with an antispasmodic agent. However, atropine-like drugs should be avoided when paralytic ileus is present because they may contribute to the problem. Other medications that relax smooth muscles (spasmolytics), such as glyceryl trinitrate or papaverine, may be used. If vomiting is a problem, prochlorperazine or metoclopramide are used.

If shock is present, blood volume replacements are used. Plasma or plasma volume expanders such as albumin may be given. Fluid and electrolyte imbalances are corrected with Hartmann’s solution or other electrolyte solutions. Central venous pressure readings may be used to assist in the determination of fluid replacement requirements. Vasoactive drugs such as adrenaline or noradrenaline may be used to increase systemic vascular resistance in patients with ongoing hypotension.

It is important to reduce or suppress pancreatic enzymes to decrease stimulation of the pancreas and allow it to rest. This is accomplished in several ways. First, the patient is allowed to take nothing by mouth (NBM). Second, NG suction may be used to reduce vomiting and gastric distension and to prevent gastric acidic contents from entering the duodenum. These measures suppress pancreatic secretion. Certain drugs may also be used for this purpose (see Box 43-4 and Table 43-16). Enteral feedings are given via a jejunal tube to avoid stimulation of the pancreas by luminal content in the duodenum.

The inflamed and necrotic pancreatic tissue is a good medium for bacterial growth. Therefore, it is important to prevent infections. There is some controversy about the prophylactic use of antibiotics. It is important to monitor the patient closely so that antibiotic therapy can be instituted early if infection occurs.29

Surgical therapy

When the acute pancreatitis is related to the presence of gallstones, an urgent ERCP plus endoscopic sphincterotomy may be performed. This may be followed by laparoscopic cholecystectomy to reduce the potential for recurrence. Surgical intervention may also be indicated when the diagnosis is uncertain and in patients who do not respond to conservative therapy. Patients with severe acute pancreatitis may require drainage of necrotic fluid collections. This can be done either surgically, under CT guidance, or endoscopically. Percutaneous drainage of a pseudocyst can be performed and a drainage tube is left in place.

Drug therapy

Several different drugs may be used in the treatment of both acute and chronic pancreatitis (see Table 43-16). A number of drugs are used in an effort to suppress pancreatic secretion but these drugs have not proved effective in the management of pancreatitis.

Nutritional therapy

Initially the patient with acute pancreatitis is NBM to reduce pancreatic secretion. Depending on the severity of the pancreatitis, enteral feedings or parenteral nutrition may be initiated (see Ch 39). If IV lipids are ordered, blood triglyceride levels need to be monitored. In cases of moderate-to-severe pancreatitis, the patient may require enteral feeding via a jejunal feeding tube. When food is allowed, small, frequent feedings are given. The diet is usually high in carbohydrate content because that is the least stimulating to the exocrine portion of the pancreas. The diet is bland, with no stimulants (e.g. caffeine) or alcohol. Intolerance to oral foods is suspected when the patient reports increasing abdominal girth or has elevations in serum amylase and lipase levels. Supplemental fat-soluble vitamins may be given (see Ch 39).

NURSING MANAGEMENT: ACUTE PANCREATITIS

NURSING MANAGEMENT: ACUTE PANCREATITIS

Nursing assessment

Nursing assessment

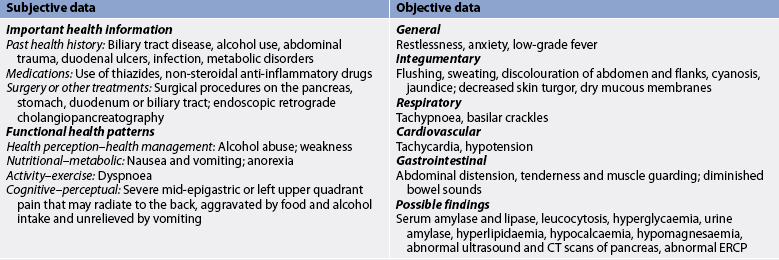

Subjective and objective data that should be obtained from the patient with acute pancreatitis are presented in Table 43-17.

Nursing diagnoses

Nursing diagnoses

Nursing diagnoses for the patient with acute pancreatitis may include, but are not limited to, those presented in NCP 43-3.

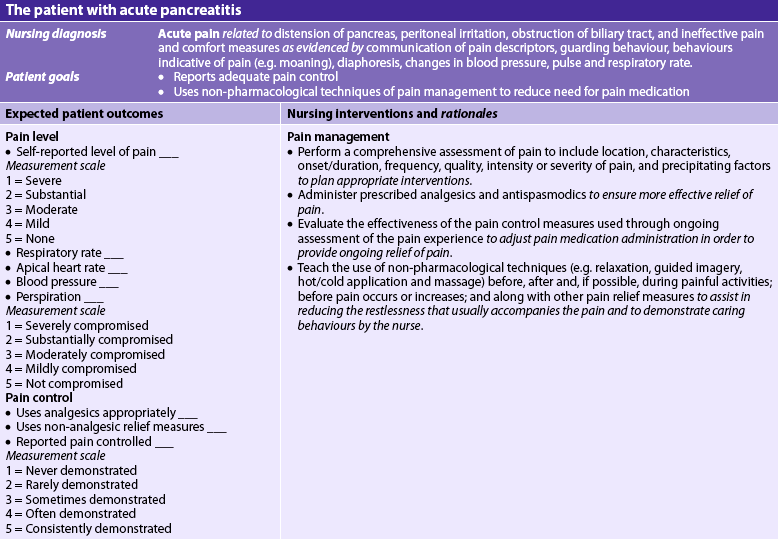

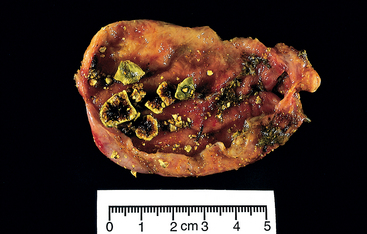

NURSING CARE PLAN 43-3 The patient with acute pancreatitis

Planning

Planning

The overall goals are that the patient with acute pancreatitis will have: (1) relief of pain; (2) normal fluid and electrolyte balance; (3) minimal to no complications; and (4) no recurrent attacks.

Nursing implementation

Nursing implementation

Health promotion

Health promotion

The major factors involved in health promotion are assessment of the patient for predisposing and aetiological factors of pancreatitis and encouragement of early treatment of these factors to prevent the occurrence of acute pancreatitis. The nurse should educate the patient about symptoms that will allow early diagnosis and treatment of biliary tract disease, such as cholelithiasis. The patient should be encouraged to eliminate alcohol intake, especially if there have been any previous episodes of pancreatitis. Attacks of pancreatitis become milder or disappear with the discontinuance of alcohol use.

Acute intervention

Acute intervention

During the acute phase, it is important to monitor vital signs. Haemodynamic stability may be compromised by hypotension, fever and tachypnoea. IV fluids are ordered and the response to therapy is monitored. A vital part of the nursing care plan is observation for electrolyte imbalances. Frequent vomiting, along with gastric suction, may result in decreased chloride, sodium and potassium levels.

The patient with severe acute pancreatitis may develop respiratory failure. It is important that respiratory function be assessed (e.g. lung sounds). If acute respiratory distress syndrome develops, the patient may require intubation and mechanical ventilatory support.

Because hypocalcaemia can also occur, the nurse must observe for symptoms of tetany, such as jerking, irritability and muscular twitching. Numbness or tingling around the lips and in the fingers is an early indicator of hypocalcaemia. The patient should be assessed for a positive Chvostek’s or Trousseau’s sign. Calcium gluconate (as ordered) should be given to treat symptomatic hypocalcaemia. In addition, hypomagnesaemia may develop, necessitating the observation of serum magnesium levels.

Since abdominal pain is a prominent symptom of pancreatitis, a major focus of nursing care is the relief of pain (see NCP 43-3). Pain and restlessness can increase the metabolic rate and subsequent stimulation of pancreatic enzymes. Giving the prescribed medications before the pain becomes too severe makes the medication more effective; therefore, drug delivery via PCA or continuous infusion is the method of choice. Morphine or fentanyl may be used for pain relief. The nurse should regularly ascertain the effectiveness of analgesia. The use of pain scales will assist in this process.

Measures such as comfortable positioning, frequent changes in position and relief of nausea and vomiting assist in reducing the restlessness that usually accompanies the pain. Assuming positions that flex the trunk and draw the knees up to the abdomen may decrease pain. A side-lying position with the head elevated 45° decreases tension on the abdomen and may help ease the pain.

Nursing measures for the patient who is NBM or has an NG tube should be employed. Frequent oral and nasal care to relieve the dryness of the mouth and nose is comforting to the patient. Oral care is essential to prevent parotitis. Additional dryness of the mouth is caused by anticholinergics, which are taken to decrease GI secretions. If the patient is taking antacids to neutralise gastric acid, they should be sipped slowly or inserted in the NG tube.

The patient with acute pancreatitis is susceptible to infections. The nurse should observe for fever and other manifestations of infection. Respiratory infections are common because the retroperitoneal fluid raises the diaphragm, which causes the patient to take shallow, guarded abdominal breaths. Measures to prevent respiratory infections include turning, coughing, deep breathing and assuming a semi-Fowler position.

Other important assessments are observing for signs of paralytic ileus, renal failure and mental changes. The blood glucose level should be measured to assess damage to the β-cells of the islets of Langerhans in the pancreas.

After pancreatic surgery the patient may require special wound care for an anastomotic leak or a fistula. Measures to prevent skin irritation should be used. These include skin barriers such as Stomahesive paste, pouching and drains. In addition to protecting the skin, pouching provides a more accurate determination of fluid and electrolyte losses and increases patient comfort. Sterile pouching systems are available. The nurse may want to consult with a clinical specialist or a stomal therapist, if available.

Ambulatory and home care

Ambulatory and home care

After acute pancreatitis, the patient may need home care follow-up. The patient may have lost physical reserve and muscle strength, and physiotherapy may be needed. Continued care to prevent infection and detect any complications is important. Because frequent doses of narcotics may be required during the acute stage, the patient may be worried about possible addiction and needs to be reassured that this is highly unlikely. Addiction to narcotics when given for pain relief has been found in less than 1% of cases (see Ch 8). It is important that patients are provided with adequate pain relief and that misconceptions about narcotic addiction are explained adequately (see Ch 10). Counselling about abstinence from alcohol is important to prevent the patient from experiencing future attacks of acute pancreatitis and developing chronic pancreatitis. Beverages with caffeine should not be consumed. Because smoking and stressful situations can overstimulate the pancreas, they should be avoided.

Dietary teaching should include the importance of restricting fats, because they stimulate the secretion of cholecystokinin, which then stimulates the pancreas. Carbohydrates are less stimulating to the pancreas, so they should be encouraged. The patient should be instructed to avoid crash dieting and binge eating because they can precipitate attacks.

The patient and family should be given instructions about recognising and reporting symptoms of infection, diabetes mellitus or steatorrhoea (foul-smelling, frothy stools). These changes indicate possible ongoing destruction of pancreatic tissue. The nurse should make sure that the patient fully understands the prescribed regimen. Each aspect must be explained. The importance of taking the required medications and following the recommended diet should be stressed.

Evaluation

Evaluation

Expected outcomes for the patient with acute pancreatitis are presented in NCP 43-3.

Chronic pancreatitis

Chronic pancreatitis is a continuous, prolonged, inflammatory and fibrosing process of the pancreas. The pancreas becomes progressively destroyed as it is replaced with fibrotic tissue. Strictures and calcifications may also occur in the pancreas.

AETIOLOGY AND PATHOPHYSIOLOGY

There are several types of chronic pancreatitis but they all have a common underlying pathophysiological disorder. The two major types are chronic obstructive pancreatitis and chronic calcifying pancreatitis. Chronic pancreatitis may follow acute pancreatitis but it may also occur in the absence of any history of an acute condition.

Chronic obstructive pancreatitis is associated with biliary disease. The most common cause is inflammation of the sphincter of Oddi associated with cholelithiasis. Cancer of the ampulla of Vater, duodenum or pancreas can also cause this type of chronic pancreatitis.

In chronic calcifying pancreatitis there is inflammation and sclerosis, mainly in the head of the pancreas and around the pancreatic duct. This type of chronic pancreatitis is the most common form, and in 90% of patients the cause is chronic alcohol use. As with cirrhosis there seems to be a metabolic abnormality that predisposes a person who drinks to the direct toxic effect of the alcohol on the pancreas. In chronic calcifying pancreatitis the ducts are obstructed with protein precipitates. These precipitates block the pancreatic duct and eventually calcify. This is followed by fibrosis and glandular atrophy. Pseudocysts and abscesses commonly develop.

CLINICAL MANIFESTATIONS

As with acute pancreatitis, a major manifestation of chronic pancreatitis is abdominal pain. The patient may have episodes of acute pain but it is usually chronic (recurrent attacks at intervals of months or years). The attacks may become more and more frequent until they are almost constant, or they may diminish as the pancreatic fibrosis develops. The pain is located in the same areas as in acute pancreatitis but it is usually described as a heavy, gnawing feeling, or sometimes as burning and cramp-like. The pain is not relieved with food or antacids.

Other clinical manifestations include symptoms of pancreatic insufficiency, including malabsorption with weight loss, constipation, mild jaundice with dark urine, steatorrhoea and diabetes mellitus. The steatorrhoea may become severe, with voluminous, foul, fatty stools. Urine and stools may be frothy. Some abdominal tenderness may be present.

Chronic pancreatitis is also associated with a variety of complications. These include pseudocyst formation, bile duct or duodenal obstruction, pancreatic ascites or pleural effusion, splenic vein thrombosis, pseudoaneurysms and pancreatic cancer.

DIAGNOSTIC STUDIES

Confirming the diagnosis of chronic pancreatitis can be challenging. The diagnosis is based on the patient’s signs and symptoms, laboratory results and imaging. In chronic pancreatitis the levels of serum amylase and lipase may be elevated slightly or not at all, depending on the degree of pancreatic fibrosis. Increased serum bilirubin and increased alkaline phosphatase levels may be present. There is usually mild leucocytosis and an elevated erythrocyte sedimentation rate.

ERCP is used to visualise the pancreatic and common bile ducts. An endoscope is inserted into the duodenum. The common bile duct and pancreatic duct are then cannulated and contrast media is injected into the ducts for visualisation. Changes in the pancreatic ductal system, such as gross dilation and microcysts, can be visualised through the use of ERCP. Imaging studies such as CT, MRI, transabdominal ultrasound and endoscopic ultrasound are useful in patients with chronic pancreatitis. These procedures show a variety of changes, including calcification, ductal dilation, pseudocysts and pancreatic enlargement.

Other abnormal diagnostic findings are hyperglycaemia and fatty stools (steatorrhoea). Stools are examined for faecal fat content. Arteriography and X-rays may demonstrate fibrosis and calcification.

The secretin stimulation test is used to assess pancreatic function. In the normal pancreas secretin stimulates bicarbonate (HCO3−) secretion. In the stimulation test secretin is given intravenously and gastric–duodenal secretions are collected with a double-lumen tube for separate gastric and duodenal aspiration. In chronic pancreatitis there is a reduced volume of secretions and reduced bicarbonate concentration (<90 mmol/L). Normally, secretin stimulates the production of pancreatic fluid high in bicarbonate content.

MULTIDISCIPLINARY CARE

When the patient with chronic pancreatitis is experiencing an acute attack, the therapy is identical to that for acute pancreatitis. At other times the focus is on the prevention of further attacks, relief of pain and control of pancreatic exocrine and endocrine insufficiency. It sometimes takes large, frequent doses of analgesics to relieve the pain.

Diet, pancreatic enzyme replacement and control of diabetes are measures used to control pancreatic insufficiency. The diet is bland, low in fat and high in carbohydrate. The patient does not tolerate fatty, rich and stimulating foods, and these should be avoided to decrease pancreatic secretions. Alcohol must be totally eliminated.

Pancreatic enzymes such as pancreatin and pancrelipase contain amylase, lipase and trypsin and are used to replace the deficient pancreatic enzymes. They are usually enteric-coated to prevent their breakdown or inactivation by gastric acid. Bile salts are sometimes given to facilitate the absorption of the fat-soluble vitamins (A, D, E and K) and prevent further fat loss. If diabetes develops, it is controlled with insulin or oral hypoglycaemic agents. Acid-neutralising drugs (e.g. antacids) and acid-inhibiting drugs (e.g. H2-receptor blockers, proton pump inhibitors, anticholinergics) may be given to decrease hydrochloric acid but have little overall effect on the outcome of the disease.