Switching to Another Opioid or Route of Administration

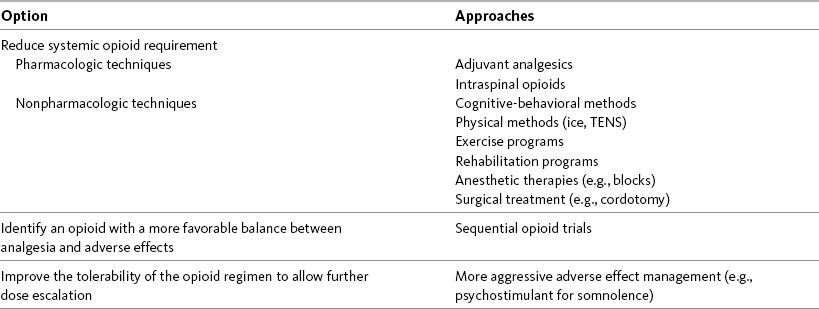

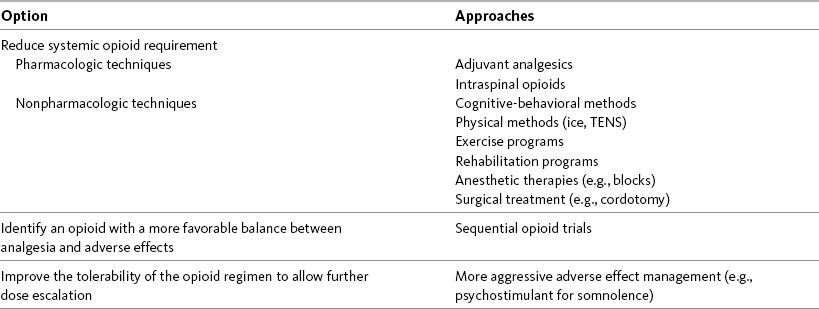

WITH few exceptions, analgesia is dose-related rather than opioid-related. Thus unrelieved pain per se is not a sound reason for switching to another opioid. Other options for improving analgesia should be tried, such as increasing the opioid dose, providing a nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drug (NSAID) around the clock (ATC), or adding local anesthetic to epidural opioids. Adverse effects that are intolerable and unmanageable are more likely to be an appropriate reason to switch to another opioid (Knotkova, Fine, Portenoy, 2009). Because of great interindividual variability, even opioids that bind to the same receptor site can produce adverse effects of different intensities in patients. The development of toxic effects from metabolite accumulation is a common reason for opioid rotation during long-term opioid therapy, and some recommend multiple switches if the first change in drug does not relieve symptoms (Hanks, Cherny, Fallon, 2004; Knotkova, Fine, Portenoy, 2009) (see Table 18-1 for options when analgesia from opioids is limited by adverse effects). Although switching to another opioid is common and recommended under these circumstances, a Cochrane Collaboration Review concluded that randomized controlled research is lacking and the practice is based largely on anecdotal or observational and uncontrolled studies (Quigley, 2004).

Table 18-1

Options When Analgesia from Opioids Is Limited by Adverse Effects

TENS, Transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation.

From Pasero, C., & McCaffery, M. Pain assessment and pharmacologic management, p. 474, St. Louis, Mosby. Modified from Portenoy, R. K. (1998). Adjuvant analgesics in pain management. In D. Doyle, G. Hanks, & N. MacDonald (Eds.), Oxford textbook of palliative medicine, ed 2, New York, Oxford University Press. Pasero C, McCaffery M. May be duplicated for use in clinical practice.

Patient difficulty in adhering to an analgesic regimen may be a sound reason to switch to another opioid. Sometimes another opioid allows a reduction in pills or liquid volume needed for pain relief. Fewer or smaller doses may be possible, making it easier for some patients to comply with the pain treatment regimen.

There is no good evidence that analgesic efficacy is dependent on route of administration; morphine is equally efficacious when given in appropriate doses by the oral, parenteral, or intraspinal routes (Hanks, Cherny, Fallon, 2004). However, occasionally switching from one opioid or route to another opioid or route is done to reduce the cost of long-term opioid treatment (Knotkova, Fine, Portenoy, 2009). For example, in one case the cost of opioid treatment was reduced from $1000 per day to less than $25 per day when a patient was switched from parenteral hydromorphone to oral methadone (Thomas, Bruera, 1995). The cost of the 10-day hospital stay required during the conversion process was not included in the cost analysis. Thus several factors must be considered when switching opioids to reduce costs.

When switching an opioid-tolerant patient to an alternative opioid drug, it is wise to assume that cross-tolerance will be incomplete (Knotkova, Fine, Portenoy, 2009). This means that a patient who has developed tolerance to one opioid analgesic may not be equally tolerant to another. In such cases, the starting dose of the new opioid must be reduced by at least 25% to 50% of the calculated equianalgesic dose to prevent overdosing (see Chapter 13, pp. 339-350, for the recommended approach when converting to methadone); otherwise, the full calculated equianalgesic dose of the new opioid could lead to effects such as sedation that would be greater than expected (Fine, Portenoy, the Ad Hoc Expert Panel on Evidence Review and Guidelines for Opioid Rotation, 2009; Knotkova, Fine, Portenoy, 2009; Indelicato, Portenoy, 2002; Vadalouca, Moka, Argyra, et al., 2008). Even with this approach, some patients will experience underdosing and some will experience overdosing because of individual sensitivities.

It is also best not to abruptly discontinue the present opioid and convert to the new opioid in one step. This could cause a significant overdose that precipitates undesirable adverse effects or an underdose that precipitates severe pain. Instead, it is best to make the transition with 50% of the current opioid dose combined with 50% of the projected dose for the new opioid for several days. From this starting point, gradual increases in the new opioid drug and decreases in the old drug can be made until the switch is complete. The higher the dose of the current opioid, the more important it is to make the transition using 50/50 dosing (see Box 18-1 for guidelines when switching from one opioid to another).

Box 18-1 Switching from One Opioid to Another1

NOTE: See Chapter 14 and Box 14-6 (p. 393) for switching to transdermal fentanyl; see Chapter 13 and Box 13-3 (p. 345) and Table 13-8 (pp. 346-347) for switching to methadone. For all other opioid analgesics, use the equianalgesic dose chart in Table 16-1 on pp. 444-446 and follow the steps listed below, which provide direction for switching from one oral opioid to another oral opioid, using the example of oral short-acting morphine to oral short-acting oxycodone:

1. Determine the total daily dose of the current opioid (e.g., morphine, 30 mg, taken q 4 h PO: 30 mg × 6 doses/day = 180 mg/24 h).

2. Locate the dose of the current opioid by the current route listed in the equianalgesic dose chart (e.g., 30 mg).

3. Determine the number of equianalgesic dose units in the 24-hour dose by dividing the 24-hour dose by the equianalgesic dose (e.g., 180 mg ÷ 30 mg = 6 units).

4. Locate the dose of the new opioid by the route of the new opioid listed on the equianalgesic dose chart (e.g., oxycodone 20 mg).

5. Determine the 24-hour dose of the new opioid by multiplying the equianalgesic dose of the new opioid by the equianalgesic dose units of the current opioid (e.g., 20 mg × 6 units = 120 mg/24 h of oxycodone).

6. Divide the 24-hour dose of the new drug by the number of doses to be given each 24 hours (e.g., 120 mg/24 h of oxycodone ÷ 6 doses = 20 mg of oxycodone q 4 h).

7. If the patient is opioid tolerant and has been taking a high dose of opioid, it is best to reduce the calculated dose of the new opioid by 25% to 50% (e.g., for 25% reduction: 20 mg oxycodone × 0.25 = 5 mg; 20 − 5 mg = 15 mg; for 50% reduction: 20 mg oxycodone × 0.50 = 10 mg).

8. It is also important not to abruptly discontinue the current opioid and convert to the new in one step. This could lead to an overdose, causing undesirable adverse effects, or an underdose, precipitating severe pain. Instead, in these cases, make the transition starting with 50% of the current opioid dose (e.g., 30 mg of morphine × 0.50 = 15 mg of morphine) combined with 50% of the projected dose for the new opioid (e.g., 15 mg of oxycodone × 0.50 = 7.5 mg of oxycodone, or 10 mg of oxycodone × 0.50 = 5 mg). Gradual increases in the new opioid drug and decreases in the old one can be made until the switch is complete over a period of several days. For example, in the case of a 25% reduction (see step 7), start by giving oxycodone 7.5 mg PO q 4 h and morphine 15 mg PO q 4 h. In the case of a 50% reduction (see step 7), start by giving oxycodone 5 mg PO q 4 h and morphine 15 mg PO q 4 h. It may be necessary to adjust the dose of the new opioid (i.e., maintain the 50% dose of the old opioid and increase the new opioid for insufficient pain relief). Once the combined doses provide good pain control, drop the old opioid dose and double the new one.

9. After all calculations are made, perform a second assessment of pain severity, patient response, and medical and other characteristics to determine whether to apply an additional increase or decrease of 15% to 30% to enhance the likelihood that the initial dose will be effective for pain, or conversely, unlikely to cause withdrawal or opioid-related adverse effects.

10. Have a strategy to frequently assess initial response and titrate the dose of the new opioid regimen to optimize outcomes.

11. If a supplemental dose is used for titration, see Box 16-2 (p. 449) for calculation; if oral transmucosal formulation is used, see Boxes 14-2 (pp. 382-383) and 14-3 (pp. 384-385).

h, Hour; hs, at sleep; PO, oral; q, every.

Occasionally, during opioid treatment it is necessary to switch from one opioid to another. Calculating the equianalgesic dose of the new opioid increases the likelihood that patients will tolerate the switch to a new opioid without loss of pain control or excessive adverse effects. This box provides calculations for equianalgesic dosing.

1An expert panel was convened for the purpose of establishing a new guideline for opioid rotation and recently proposed a two-step approach (Fine, Portenoy, the Ad Hoc Expert Panel on Evidence Review and Guidelines for Opioid Rotation, 2009). The approach presented in the text for calculating the dose of a new opioid can be conceptualized as the panel’s Step One, which directs the clinician to calculate the equianalgesic dose of the new opioid based on the equianalgesic table. Step Two suggests that the clinician perform a second assessment of the patient to evaluate the current pain severity (perhaps suggesting that the calculated dose be increased or decreased) and to develop strategies for assessing and titrating the dose as well as determining the need for a breakthrough dose and calculating that dose (see Box 16-2 on p. 449). The specific steps of patient examples given in the text reflect the panel’s two-step approach (see Fine, Portenoy, the Ad Hoc Expert Panel on Evidence Review and Guidelines for Opioid Rotation, 2009).

From Pasero, C., & McCaffery, M. (2011). Pain assessment and pharmacologic management, p. 475, St. Louis, Mosby. Data from Fine, P. G., Portenoy, R. K., & Ad Hoc Expert Panel on Evidence Review and Guidelines for Opioid Rotation. (2009). Establishing best practices for opioid rotation: Conclusions of an expert panel. J Pain Symptom Manage, 38(3), 418-425. Pasero C. May be duplicated for use in clinical practice.

The principles described above underscore the importance of careful dose selection and monitoring during opioid rotation (see Chapter 11 for more on cross-tolerance and the use of conversion charts, Box 14-6 on p. 393 for guidelines on switching from oral morphine to transdermal fentanyl, and Box 13-3 on p. 345 for guidelines on switching to methadone). It requires the clinician to have an understanding of opioid pharmacology and a commitment to tailoring the choice of opioid and dose to the patient’s individual characteristics and response (Shaheen, Walsh, Lahsheen, et al., 2009). An expert panel was convened for the purpose of establishing a new guideline for opioid rotation and recently proposed a two-step approach (Fine, Portenoy, the Ad Hoc Expert Panel on Evidence Review and Guidelines for Opioid Rotation, 2009). The approach presented in this chapter for calculating the dose of a new opioid can be conceptualized as the panel’s Step One, which directs the clinician to calculate the equianalgesic dose of the new opioid based on the equianalgesic table. Step Two suggests that the clinician perform a second assessment of the patient to evaluate the current pain severity (perhaps suggesting that the calculated dose be increased or decreased) and to develop a strategy for assessing and titrating the dose as well as determining the need for a breakthrough dose and calculating that dose (see Box 16-2 on p. 449). The specific steps of patient examples given in this chapter reflect the panel’s two-step approach (see Fine, Portenoy, the Ad Hoc Expert Panel on Evidence Review and Guidelines for Opioid Rotation, 2009). Following are several patient examples of conversions from one opioid to another, one route of administration to another, and combinations of both. The equianalgesic dose chart in Table 16-1 on pp. 444-446 is used for the necessary conversion calculations.

Patient Example

Switching from One Oral Opioid to Another Oral Opioid

For the last two months, Mrs. N. has been taking 30 mg of PO modified-release oxycodone every 12 hours plus 10 mg of short-acting oxycodone for breakthrough pain about twice daily for severe osteoarthritis pain. Although her pain is well-controlled with pain ratings between 1/10 and 3/10, she has experienced severe nausea that has been unresponsive to all treatment efforts since the oxycodone was started. Her nurse practitioner thinks she will respond more favorably to a different opioid. She will be switched to PO modified-release oxymorphone. The following calculations are necessary (use the equianalgesic dose chart, Table 16-1, on pp. 444-446):

1. Determine the total 24 h dose of PO oxycodone:

2. Locate the equianalgesic dose of PO oxycodone in the equianalgesic chart (20 mg).

3. Determine the number of equianalgesic dose units in the 24-hour dose by dividing the 24-hour dose of PO oxycodone by the equianalgesic dose of PO oxycodone: 80 mg ÷ 20 mg = 4 units/24 h of oxycodone.

4. Locate the dose of PO oxymorphone in the PO dose column of the equianalgesic dose chart (10 mg) that is approximately equal to 20 mg of PO oxycodone.

5. Determine the 24-hour dose of PO oxymorphone by multiplying the equianalgesic dose of PO oxymorphone (10 mg) by the equianalgesic units of PO oxycodone (4 units): 10 mg × 4 units = 40 mg/24 h of oxymorphone.

6. Mrs. N. is opioid tolerant, so the dose of the new opioid will be reduced by 25%; 40 mg × 0.25 = 10 mg; 40 mg − 10 mg = 30 mg/24 h of oxymorphone.

7. Mrs. N. may have developed some tolerance to oxycodone, but she may not be equally tolerant to oxymorphone, therefore, the complete transition is done slowly. To avoid significant overdosing or underdosing, Mrs. N. will be transitioned by continuing to take 50% of her previous opioid, oxycodone, plus 50% of her new opioid, oxymorphone. The two calculations are as follows:

a. 50% of oxycodone: 80 mg × 0.50 = 40 mg oxycodone/24 h, divided into 2 doses = 20 mg oxycodone q 12 h

b. 50% of oxymorphone: 30 mg × 0.50 = 15 mg oxymorphone/24 h, divided into 2 doses = 7.5 mg oxymorphone q 12 h

8. Breakthrough doses equal to 10% to 15% of the total daily oxymorphone dose are calculated as follows (see Box 16-2 on p. 449):

Mrs. N.’s breakthrough dose is approximately 5 mg (closest available dose strength) of short-acting oxymorphone q 1 h PRN for breakthrough pain.

After 3 days on the combined opioids and a breakthrough dose of 5 mg about twice a day, Mrs. N.’s nausea is significantly less and her pain never goes above 3/10. She is then completely converted to oxymorphone by doubling the current dose of oxymorphone to 15 mg q 12 h and continuing the breakthrough dose of 5 mg. Within two days, her nausea completely subsides and her pain ratings range from 1/10 to 3/10.

Patient Example

Switching from One IV Opioid to Another IV Opioid

Mr. T. has been receiving a continuous IV infusion of morphine 4 mg/h, with 2 mg breakthrough bolus doses q 2 h PRN since his admission to the ICU 15 days ago after an automobile accident. He uses about 3 breakthrough doses a day. His pain is well-controlled with pain ratings varying from 2/10 to 4/10, but tremors and twitching are noted during assessment and thought to be due to morphine metabolite accumulation. He will be switched to a continuous IV infusion of hydromorphone. The following calculations are necessary (use the equianalgesic dose chart, Table 16-1, on pp. 444-446):

1. Determine the total daily dose of morphine from continuous infusion and breakthrough bolus doses:

2. Locate the dose of IV morphine listed in the equianalgesic chart (10 mg).

3. Determine the number of equianalgesic dose units in the 24-hour morphine dose: 102 mg ÷ 10 mg = 10.2 units.

4. Locate the dose of IV hydromorphone listed in the parenteral column in the equianalgesic chart (1.5 mg) that is approximately equal to 10 mg of morphine IV.

5. Determine the 24-hour equianalgesic dose of IV hydromorphone: 1.5 mg hydromorphone × 10.2 units of morphine = 15.3 mg/24 h of IV hydromorphone.

6. Determine the hourly IV hydromorphone dose: 15.3 mg ÷ 24 = approximately 0.6 mg/h.

7. Because Mr. T. has been receiving morphine for several days, he may have developed some tolerance to its analgesia; however, he may not be equally tolerant to hydromorphone. Therefore, Mr. T. will be started on 50% of the equianalgesic dose of IV hydromorphone: 0.6 mg × 0.50 (50%) = 0.3 mg/h.

8. Breakthrough doses of 0.15 mg (50% of the hourly opioid dose) IV hydromorphone q 30 min PRN are prescribed for breakthrough pain (see Box 16-2 on p. 449).

9. For the first day, Mr. T.’s tremors and twitching decreased, but he used 10 breakthrough doses and on two occasions awoke with pain 5/10. The 24-hour dose and the breakthrough dose were recalculated as follows:

a. The total of 10 breakthrough doses of 0.15 mg = 0.15 ×10 = 1.5 mg hydromorphone.

b. 1.5 mg of hydromorphone is added to the current 24-hour dose (0.3 mg x 24 h) of 7.2 mg = 8.7 mg/24 h

c. The new 24-hour dose of hydromorphone, 8.7 mg, is divided by 24 = approximately 0.4 mg/h of IV hydromorphone.

d. The new breakthrough dose is calculated by taking 50% of the hourly opioid dose, 0.4 mg, and dividing by 2 = 0.2 mg IV hydromorphone q 30 min.

For the next two days, Mr. T. used only 2 breakthrough doses, his pain remained at 2/10, and no further twitching or tremors were noted.

Patient Example

Switching from One SC Opioid to Another SC Opioid

For the last 2 months, Mrs. Q. has been receiving a continuous SC infusion of morphine, 25 mg/h with 5 mg breakthrough bolus doses q 15 min PRN. She has developed unmanageable sedation and confusion. Her physician would like to switch her to an equianalgesic continuous SC infusion of hydromorphone. The following calculations are necessary (use the equianalgesic dose chart, Table 16-1, on pp. 444-446):

1. Determine the total daily dose of morphine from continuous infusion and breakthrough bolus doses:

2. Locate the dose of parenteral morphine listed in the equianalgesic chart (10 mg).

3. Determine the number of equianalgesic dose units in the 24-hour morphine dose: 620 mg ÷ 10 mg = 62 units.

4. Locate the dose of parenteral hydromorphone listed in the equianalgesic chart (1.5 mg) that is approximately equal to 10 mg of morphine.

5. Determine the 24-hour equianalgesic dose of parenteral hydromorphone: 1.5 mg × 62 units = 93 mg of hydromorphone/24 h.

6. Determine the hourly hydromorphone dose: 93 mg ÷ 24 h = approximately 4 mg/h.

7. Because Mrs. Q. has been receiving morphine for several weeks, she may have developed some tolerance to its analgesia; however, she may not be equally tolerant to hydromorphone. Therefore the starting hourly equianalgesic dose of hydromorphone will be reduced by 50%: 4 mg × 0.50 (50%) = 2 mg /h of hydromorphone

8. Breakthrough doses of 1 mg (50% of hourly requirement = 2 mg × 0.50 [50%] = 1 mg) SC hydromorphone PRN q 30 min are prescribed for breakthrough pain (see Box 16-2 on p. 449).

Because Mrs. Q. has been receiving a high dose of opioid for a long period of time, it is best to make the transition to the new opioid slowly. To do this, she is started on 50% of the new opioid dose (hydromorphone 2 mg/h × 0.50 [50%] = 1 mg/h) while taking 50% of the old opioid dose (morphine 25 mg/h × 0.50 [50%] = 12.5 mg/h) for several days. Gradual increases in the hydromorphone dose and decreases in the morphine dose are made until the switch to hydromorphone is complete. Inadequate pain relief is treated with breakthrough doses of hydromorphone and increases in the hourly hydromorphone dose. Within 9 days, the switch to hydromorphone is complete without loss of pain control, and Mrs. Q. is much less sedated and confused.

Switching from Epidural to IV Opioid Analgesia

Occasionally, a patient must be switched from epidural opioids to IV opioids before the transition to oral analgesia can be made (e.g., when the epidural catheter is accidentally pulled out or analgesia is unsatisfactory because the epidural catheter location is less than optimal). When this happens, conversion ratios usually are used as guidelines for selecting starting IV doses. Studies are lacking and controversy exists over the correct ratios to use when switching opioid-naïve patients from the various epidural opioids to parenteral opioids (see Chapter 15 for selecting starting epidural opioid doses). Most often, a conversion ratio of 1:10 is used to determine a starting dose when switching opioid-naïve patients from epidural morphine to IV morphine (Maalouf, Liu, 2009) (see the following patient example). Many clinicians use a ratio of 1:5 for switching from epidural hydromorphone to IV hydromorphone and a ratio of 1:3 for switching from epidural fentanyl to IV fentanyl.

Patient Example

Switching from an Epidural Opioid to an IV Opioid

Mrs. J. had a Whipple procedure 2 days ago. Her postoperative pain has been well-controlled (3/10) with PCEA morphine (basal rate = 0.1 mg/h; PCEA dose = 0.1 mg; lockout interval = 10 minutes). While ambulating this morning, Mrs. J.’s epidural catheter was accidentally pulled out. Mrs. J. is NPO with an NG tube, so she is unable to take oral analgesia and will be given IV PCA morphine instead. Because Mrs. J. will continue with the same opioid (morphine) and the same method of administration (PCA), the calculation for determining an equianalgesic starting prescription for the IV route is relatively simple. The ratio of 1:10 is used to calculate starting doses when changing from the epidural morphine to IV morphine:

1. Determine the equianalgesic IV PCA morphine dose: 0.1 mg (PCEA dose) × 10 = 1 mg for the PCA dose q 10 min.

2. The lockout (delay) interval of 10 minutes is acceptable for both IV PCA and PCEA morphine.

Mrs. J. is 78 years old and rarely required a PCEA dose while receiving epidural analgesia, so IV PCA is started without a basal rate and will be added if she is unable to maintain comfort and rest adequately. She manages her pain effectively with IV PCA only for the remainder of therapy.

Switching from IV to Oral Opioid Analgesia

Most often switching to another route of administration is done when acute pain subsides and the opioid-naïve patient is switched from IV opioids to oral opioids as described in the following patient example. Equianalgesic doses increase the likelihood that the transition to the oral route will be done without loss of pain control.

Patient Example

Switching from an IV Opioid to an Oral Opioid

Mrs. J. had a Whipple procedure 4 days ago. She has been managing her postoperative pain using IV PCA morphine for the last 2 days; the first 2 days were managed with epidural analgesia. Her condition has improved to the point that she presses her PCA button just once or twice an hour. She is tolerating oral fluids. Her surgeon wants to discontinue PCA and has prescribed 1 Percocet (oxycodone, 5 mg, plus acetaminophen, 325 mg per tablet) q 4 h PRN for pain. To be sure this prescription is comparable to what Mrs. J. has been taking to control her pain with IV PCA, her nurse calculates Mrs. J.’s analgesic requirements as follows (use the equianalgesic dose chart, Table 16-1, on pp. 444-446):

1. Determine Mrs. J.’s current total 24-hour dose of morphine by adding the number of times she self-administered morphine during the last 24 hours (29 times) and multiplying it by the PCA dose (1 mg). The total 24-hour dose of morphine is: 1 mg × 29 times = 29 mg. (If Mrs. J. had been receiving a basal rate during the past 24 hours, the amount of the basal rate would need to be added into her total 24-hour dose.)

2. Locate the equianalgesic dose of morphine by the IV route in the equianalgesic chart (10 mg).

3. Determine the number of equianalgesic dose units in the 24-hour dose of morphine by dividing the total 24-hour dose (29 mg) by the equianalgesic dose (10 mg): 29 mg ÷ 10 = 2.9 dose units.

4. Locate the equianalgesic dose of PO oxycodone in the equianalgesic chart (20 mg).

5. Determine the 24-hour dose of PO oxycodone that will be required by multiplying the equianalgesic dose of oxycodone (20 mg) by the equianalgesic dose units of morphine (2.9 units): 20 mg × 2.9 = 58 mg of PO oxycodone/24 h.

6. Determine the number of doses that would be equianalgesic to what Mrs. J. is currently taking by dividing the total 24-hour dose of oxycodone (58 mg) by the number of doses that may be taken as prescribed each 24-hour (6 doses): 58 mg ÷ 6 doses = approximately 9.7 mg oxycodone/dose.

7. Determine whether the prescription the surgeon has written is equianalgesic. Because Percocet has just 5 mg of oxycodone per tablet, Mrs. J. would need to take 2 tablets, not 1, q 4 h to achieve the level of pain relief provided by IV PCA morphine. The acetaminophen (325 mg/tablet) will provide some additional analgesia, but not enough. The prescription the surgeon has written is not equianalgesic to the previous dose. Rather, it is about one-half the previous dose and probably will not provide adequate relief for Mrs. J.

Mrs. J.’s nurse first faxes her calculations to the surgeon who is in the clinic today and follows with a telephone call to discuss her calculations. The surgeon agrees that the prescription needs to be changed to 2 Percocet q 4 h. (See Table 17-3 on p. 472. This table can be posted in the clinical units to facilitate equianalgesic conversions from IV to oral analgesics.)

Switching from Oral to IV Opioid Analgesia

Sometimes a patient’s condition worsens and analgesia is no longer possible by the oral route making it necessary to switch to IV analgesia (see the following patient example). Equianalgesic doses increase the likelihood that the transition will be done without loss of pain control.

Patient Example

Switching from Oral to IV Opioid Analgesia

Ms. R. has advanced ovarian cancer and has been taking PO modified-release oxymorphone 60 mg q 12 h and short-acting oxymorphone 10 mg q 2 h PRN for breakthrough pain with satisfactory pain control until now. She has just been admitted to the ED with a possible bowel obstruction. She is to be switched to IV oxymorphone. The following calculations are necessary (use the equianalgesic dose chart, Table 16-1, on pp. 444-446):

1. Determine the total 24-hour dose of PO oxymorphone:

2. Locate the equianalgesic dose of PO oxymorphone in the equianalgesic chart (10 mg).

3. Determine the number of equianalgesic dose units in the 24-hour dose by dividing the 24-hour dose of PO oxymorphone by the equianalgesic dose of PO oxymorphone: 140 mg ÷ 10 mg = 14 units.

4. Locate the dose of IV oxymorphone in the equianalgesic dose chart (1 mg) that is approximately equal to 10 mg of PO oxymorphone.

5. Determine the 24-hour dose of IV oxymorphone by multiplying the equianalgesic dose of IV oxymorphone by the equianalgesic units of PO oxymorphone: 1 mg × 14 units = 14 mg/24 h

6. Divide the 24-hour dose of IV oxymorphone by the number of doses to be given each 24 hours: 14 mg ÷ 24 doses = approximately 0.6 mg/h.

7. Breakthrough doses are 0.3 mg (50% of the hourly dose). Because she is opioid tolerant, most of her pain control will come from the IV continuous infusion, and she will be allowed to double her hourly IV dose if necessary with boluses of IV oxymorphone q 30 min PRN for breakthrough pain.

Ms. R. tolerates the transition from oral oxymorphone to IV oxymorphone with pain ratings no higher than 3/10 and no adverse effects. A bowel obstruction is confirmed, but she decides against surgery; she will continue to receive IV oxymorphone for pain control.

Patient Example

Switching from One Opioid and Route to Another Opioid and Route

Mr. X., previously at home, had satisfactory pain control with 120 mg of PO modified-release oxycodone q 12 h and did not require breakthrough doses. He has been admitted for initiation of a hydromorphone SC infusion because he can no longer swallow. He finds the rectal route of administration highly objectionable, and he had a severe dermal reaction to the transdermal fentanyl patch, so these methods of pain control are not options. To determine the dose of SC hydromorphone that is approximately equal to the dose of PO oxycodone Mr. X. is taking, the following calculations are necessary (use the equianalgesic dose chart, Table 16-1, on pp. 444-446):

1. Determine the total 24-hour dose of oxycodone: 120 mg × 2 doses/24 h = 240 mg/24 h.

2. Locate the equianalgesic dose of PO oxycodone in the equianalgesic chart (20 mg).

3. Determine the number of equianalgesic dose units in the 24-hour dose by dividing the 24-hour dose of oxycodone by the equianalgesic dose of PO oxycodone: 240 mg ÷ 20 = 12 units.

4. Locate the dose of SC hydromorphone listed in the equianalgesic chart (1.5 mg) that is approximately equal to 20 mg of PO oxycodone.

5. Determine the 24-hour dose of SC hydromorphone by multiplying the dose of SC hydromorphone by the equianalgesic dose units of oxycodone: 1.5 mg × 12 units = 18 mg/24 h.

6. Divide the 24-hour dose of hydromorphone by the number of doses to be given each 24 hours: 18 mg ÷ 24 doses = approximately 0.8 mg/h.

7. Because Mr. X. is opioid tolerant, he is started on 50% of the equianalgesic dose of hydromorphone: 0.8 mg × 0.50 (50%) = 0.4 mg/h SC.

8. His breakthrough SC bolus doses are calculated as 50% of his hourly infusion = 0.2 mg q 30 min.

In Mr. X.’s situation, it is not possible to make the transition using a combination of 50% oxycodone and 50% hydromorphone. Therefore when the oxycodone is discontinued and the hydromorphone is started, he is watched closely for adverse effects and the number of breakthrough bolus doses he requires. He tolerates the transition without difficulty and only requires 2 to 3 bolus doses/24 h.

Switching from Multiple Opioids and Routes to One Opioid and Route

Sometimes patients are taking multiple opioid prescriptions by more than one route to control their pain. For example, they may be taking an IM opioid to control their ongoing pain and using a combination opioid and nonopioid, such as Percocet, for breakthrough pain. To switch a patient from multiple opioids and routes to one opioid and one route, the total daily dose of all of the opioids must be calculated. The following patient examples explain how this is done.

Patient Example

Switching from Multiple Opioids and Routes to One Opioid and Route

Mrs. V. is admitted to hospice care. She has been taking 2 Norco 10/325 (hydrocodone 10 mg, and acetaminophen 325 mg/tablet) plus 2 Percocet 5/325 (oxycodone 5 mg, and acetaminophen 325 mg/tablet) every 4 hours ATC for pain control. Although she has had good pain control, the amount of acetaminophen she is taking (7800 mg/day) is well above the maximum recommended daily amount of 4000 mg (see Section III). She will be switched to PO once-daily modified-release morphine. The following calculations are necessary (use the equianalgesic dose chart, Table 16-1, on pp. 444-446):

1. Determine the 24-hour dose of hydrocodone (2 Norco q 4 h = 12 doses): 10 mg × 12 doses = 120 mg/24 h

2. Determine the equianalgesic dose units of hydrocodone orally (although equianalgesic data are unavailable for hydrocodone, 30 mg is used as an amount approximately equal to the other opioid doses listed in the equianalgesic chart): 120 mg ÷ 30 = 4 units.

3. Determine the 24-hour dose of oxycodone: 5 mg × 12 doses = 60 mg.

4. Determine the equianalgesic dose units of oxycodone: 60 mg ÷ 20 = 3 units.

5. Determine the 24-hour total equianalgesic dose units: 4 + 3 = 7 units.

6. Determine the 24-hour dose of morphine by multiplying the dose units/24 h by the equianalgesic dose of oral morphine (30 mg): 30 mg × 7 = 210 mg oral morphine.

7. Because Mrs. V. is opioid tolerant, she is started on 50% of the equianalgesic dose of morphine: 210 mg × 0.50 (50%) = 105 mg/24 h. A 100 mg strength capsule of modified-release morphine (Kadian) would approximate a dose of 105 mg/24 h. A 10 mg strength capsule is also available and would allow a dose of 110 mg/24 h. The decision is made to start Mrs. V. on 100 mg of PO modified-release morphine taken once daily, provide adequate breakthrough doses (see below), and adjust the dose of PO modified-release morphine as needed.

8. Breakthrough doses of PO short-acting morphine are used for breakthrough pain (see Box 16-2 on p. 449):

In Mrs. V.’s case, combining the old with the new opioid during transition is not feasible. Therefore, when the previous opioids are discontinued and the modified-release morphine is started, she is watched closely for pain and adverse effects.

Mrs. V. is given 15 mg of short-acting morphine with the first dose of modified-release morphine. Breakthrough doses of 10 mg to 15 mg are provided hourly as needed during the transition. Ibuprofen 400 mg is administered q 8 h ATC to compensate for the nonopioid doses of acetaminophen she was taking previously. During the first 24 hours of the transition to modified-release morphine, Mrs. V. required 3 10 mg breakthrough doses and rated her pain as acceptable at 3/10 most of the day. No changes were made in the starting dose of modified-release morphine at that time.

Patient Example

Switching from Multiple Opioids and Routes to One Opioid and Route

Mr. C. has been admitted to the hospital from a skilled nursing facility for diagnostic tests and evaluation of his rheumatoid arthritis pain. His long-standing prescription for pain control is 50 mg IM meperidine q 4 h PRN and 1 to 2 Vicodin 5/500 (hydrocodone, 5 mg, and acetaminophen, 500 mg/tablet) PO q 4 h PRN. He has required an average of 6 doses of meperidine and 12 Vicodin per day for the last 5 days. He rates his pain as 4/10 most of the day, which is acceptable for him. His physician would like to discontinue the meperidine and Vicodin and switch Mr. C. to modified-release oxymorphone. The total 24-hour dose of opioid is calculated as follows (use the equianalgesic dose chart, Table 16-1, on pp. 444-446):

1. Determine the 24-hour dose of meperidine: 50 mg × 6 doses = 300 mg/24 h.

2. Locate the equianalgesic dose of parenteral meperidine (75 mg).

3. Determine the equianalgesic dose units of meperidine: 300 mg ÷ 75 = 4 units.

4. Determine the 24-hour dose of hydrocodone: 5 mg × 12 doses = 60 mg.

5. Determine the equianalgesic dose units of hydrocodone (although equianalgesic data are unavailable for hydrocodone, 30 mg is used as an amount approximately equal to the other opioid doses listed in the equianalgesic chart): 60 mg ÷ 30 = 2 units.

6. Determine the 24-hour total equianalgesic dose units: 4 + 2 = 6 units.

7. Determine the 24-hour dose of oxymorphone by multiplying the dose units/24 h by the equianalgesic dose of oral oxymorphone (10 mg): 10 mg × 6 = 60 mg.

8. Because Mr. C. is opioid tolerant, he is started on 50% of the equianalgesic dose of oxymorphone: 60 mg × 0.50 (50%) = 30 mg/24 h.

9. Determine the q 12 h starting dose of modified-release oxymorphone: 30 mg ÷ 2 = 15 mg.

10. Determine the breakthrough dose of PO short-acting oxymorphone (see Box 16-2 on p. 449):

In Mr. C.’s case, combining the old with the new opioid during transition is not feasible. Therefore, when the previous opioids are discontinued and the modified-release oxymorphone and breakthrough doses are started, he is watched closely for pain and adverse effects. Mr. C. is given his breakthrough dose of 5 mg of short-acting oxymorphone with the first dose of 30 mg of modified-release oxymorphone. Breakthrough doses are offered hourly during the transition. Ibuprofen 400 mg is administered q 8 h ATC to substitute for the nonopioid acetaminophen he was receiving. During the first 24 hours of the transition to modified-release oxymorphone, Mr. C. required just two breakthrough doses and rated his pain 2/10 most of the day. He reported being able to sleep through the night for the first time in a week. No changes were made in his starting oxymorphone dose. He was discharged back to the skilled nursing facility 72 hours later with a pain rating of 2/10.

Switching from an Oral Opioid to Epidural Analgesia in Opioid-Tolerant Patients

Initiating epidural analgesia in opioid-tolerant patients involves initial opioid dose conversion followed by titration. As discussed above, studies are lacking and controversy exists over the correct conversion ratio to use when switching opioid-tolerant patients from oral or parenteral opioids to epidural opioids. When switching from parenteral morphine to epidural morphine, a conversion ratio of 10:1 is recommended (Swarms, Karanikolas, Cousins, 2004). A more aggressive approach uses a 3:1 parenteral/epidural ratio that considers the influence of pain severity, patient’s age, previous systemic opioid dose, and the presence of neuropathic pain (DuPen, DuPen, 1998). A 10:1 ratio is used to switch from an epidural opioid dose to an intrathecal opioid dose (Swarms, Karanikolas, Cousins, 2004).

As discussed previously, ratios are used only for calculating starting doses and then the dose is titrated to achieve acceptable analgesia and tolerable adverse effects. It is recommended that epidural analgesia in opioid-tolerant patients be initiated in a setting where the patient can be observed closely for adverse effects until the opioid dose is stabilized (DuPen, DuPen, 1998). The conversion begins with calculating the total 24-hour dose of oral or parenteral opioid as described in the following patient example.

Patient Example

Switching from an Oral Opioid to Epidural Analgesia in Opioid-Tolerant Patients

Mrs. W. has cancer pain and has experienced intolerable and unmanageable adverse effects with oral oxymorphone, oral oxycodone, and SC hydromorphone. Until about 10 days ago, she was taking 160 mg of oral modified-release morphine q 12 h and had not required any breakthrough doses for several days. She had no adverse effects, and her pain was well-controlled, usually at 2/10 to 3/10. She then began to have escalating nociceptive and neuropathic pain with pain ratings up to 7/10 despite increasing doses of morphine. Yesterday she took 600 mg of modified-release morphine q 12 h and 6 breakthrough doses of 120 mg short-acting morphine with pain ratings of 7/10 to 9/10. Her neuropathic pain, which was being treated with gabapentin 3600 mg/day and despiramine 150 mg/day, was unresponsive to noninvasive management. She refuses to take methadone. Her escalating pain is due in part to increased metastasis.

Mrs. W. will be switched to morphine via patient-controlled epidural analgesia (PCEA) today since she has had no uncontrollable adverse effects from morphine. An advantage of this route is that a local anesthetic can be added to the epidural solution if morphine alone does not control her pain. To calculate her epidural dose of morphine, her current oral morphine dose will need to be converted to parenteral morphine and then to epidural morphine. An aggressive approach using a ratio of 3:1 (instead of 10:1) will be employed because she is relatively young (50 years old) and is experiencing severe pain, some of which is neuropathic pain. Further, she is tolerant to morphine, which will be used epidurally. What epidural morphine starting dose would be appropriate for Mrs. W? (Use the equianalgesic dose chart, Table 16-1, on pp. 444-446.)

1. Determine the total 24-hour dose of oral morphine:

a. 600 mg modified-release morphine q 12 h = 600 × 2 doses/24 h = 1200 mg/24 h of modified-release morphine.

b. 120 mg short-acting morphine × 6 doses/24 h = 720 mg/24 h of short-acting morphine.

c. 1200 mg + 720 mg = 1920 mg oral morphine/24 h

2. Determine the number of equianalgesic dose units in the 24-hour dose of oral morphine by dividing the 24-hour dose by the equianalgesic dose unit of oral morphine (30 mg): 1920 mg ÷ 30 mg = 64 units.

3. Determine the 24-hour dose of parenteral morphine by multiplying the equianalgesic dose of parenteral morphine (10 mg) by the equianalgesic dose units: 10 mg × 64 units = 640 mg/24 h of parenteral morphine.

4. Determine the 24-hour epidural morphine dose by using the ratio of 3:1. This is accomplished by dividing the 24-hour parenteral dose of morphine by 3: 640 mg ÷ 3 = approximately 213 mg/24 h.

5. Determine the hourly epidural morphine dose by dividing the total 24-hour epidural morphine dose by 24 hours: 213 mg ÷ 24 = approximately 9 mg/h of epidural morphine.

6. To avoid overdosing with this aggressive conversion approach, Mrs. W. is started on a basal rate of 50% of the calculated starting epidural morphine dose: 9 mg/h x 0.50 (50%) = 4.5 mg/h. In addition, she is provided with PCEA doses that allow her to double her epidural dose every hour: 2.25 mg PCEA doses q 15 min.

Based on the number of PCEA doses needed every 24 hours to achieve a pain rating of 3/10 or better, gradual increases in the basal rate and decreases of the PCEA doses were made until most of Mrs. W.’s pain relief was provided by the basal rate with only 2 to 3 PCEA doses required per 24 hours. Within 5 days, Mrs. W. was very comfortable with pain ratings of 3/10 or less without adverse effects on 7.5 mg/h of epidural morphine and occasional PCEA doses of 2 mg. The gabapentin and despiramine were continued as well.

Conclusion

Pain relief is almost always dose related rather than opioid related. Although unrelieved pain per se is not a sound reason for switching to another opioid or route of administration, there are times when this may be necessary. Application of the principles of equianalgesia and consideration of opioid tolerance as described in accepted guidelines increase the likelihood that the transition from one opioid or route to another opioid or route will be done without loss of pain control or the introduction of opioid adverse effects.