Adjuvants Less Often Used

THIS chapter presents a few agents that are sometimes added to the treatment plan in some patients with pain. Their use as analgesics is limited, but they may provide other benefits.

Psychostimulants and Anticholinesterases

Psychostimulant drugs and drugs that block the effects of acetylcholinesterase (an enzyme that degrades acetylcholine) are sometimes used to counteract opioid-induced sedation associated with both short-term and long-term therapy. The psychostimulant medications used most often include dextroamphetamine (Dexedrine), methylphenidate (Concerta, Metadate, Methylin, Ritalin, others), modafinil (Provigil), and caffeine. Others include amphetamine (Addaral), armodafinil (Nuvigil), atomoxetine (Strattera), and dexmethylphenidate (Focalin). The acetylcholinesterase inhibitor used most often is donepezil (Aricept); others include rivastigmine (Exelon) and galantamine (Razadyne).

There is substantial evidence that psychostimulants may be analgesic (Lussier, Portenoy, 2004). However, with the exception of caffeine, which is a constituent of many proprietary analgesic products, these drugs are generally used only when pain is accompanied by another symptom such as sedation or fatigue. Nevertheless, their effect on pain relief should be monitored to identify if and when a dose of analgesics can be lowered. Although there are no specific clinical guidelines available to direct therapy, clinicians often prescribe psychostimulants when it is difficult to titrate analgesics to pain relief or when patients report unresolved sleepiness from the sedating effects of analgesics. Opioid-induced sedation usually improves within 7 days of regular dosing; however, this varies, and some individuals will benefit from either short-term or long-term treatment with a psychostimulant (Harris, Kotob, 2006). From clinical experience, these drugs can improve concentration and physical activity. In addition, psychostimulants can be helpful with depression (Macleod, 1998; Menza, Kaufman, Castellanos, 2000) and fatigue (Fishbain, Cutler, Lewis, et al., 2004a). Table V-1, pp. 748-756, at end of Section V contains dosing recommendations for selected psychostimulants.

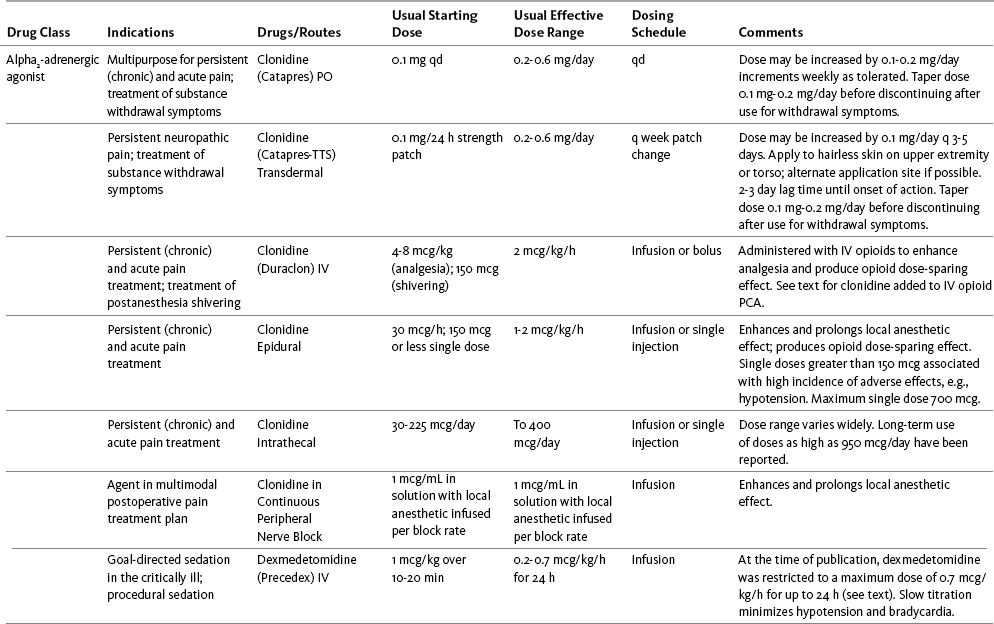

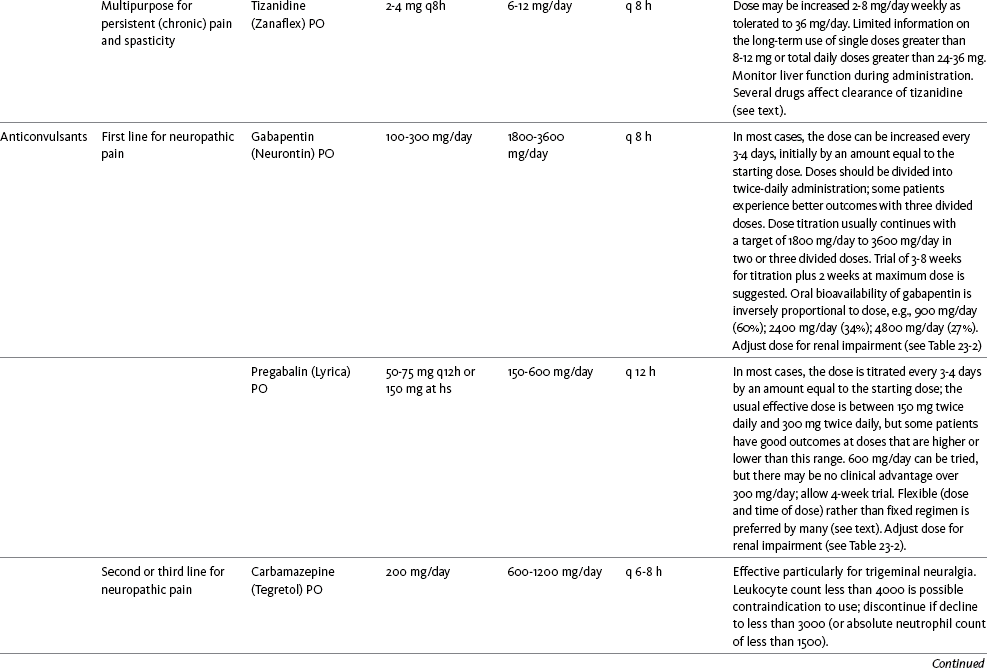

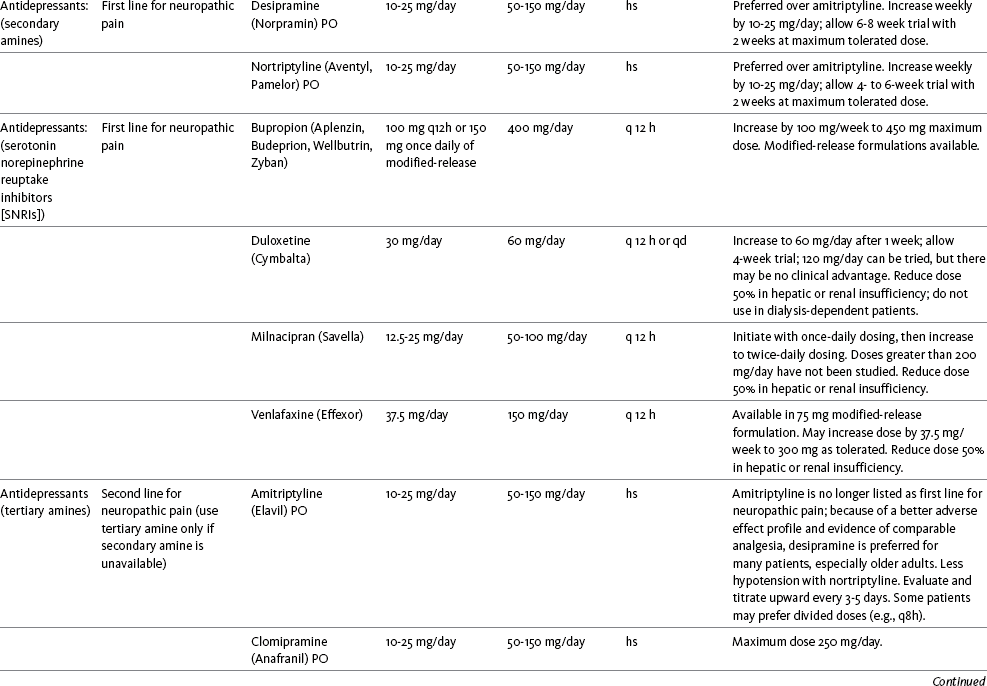

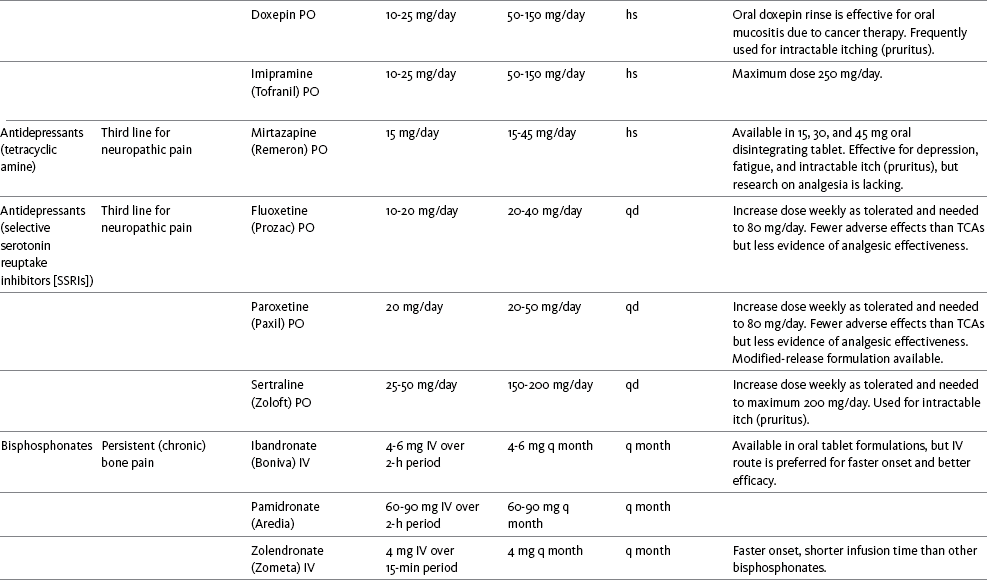

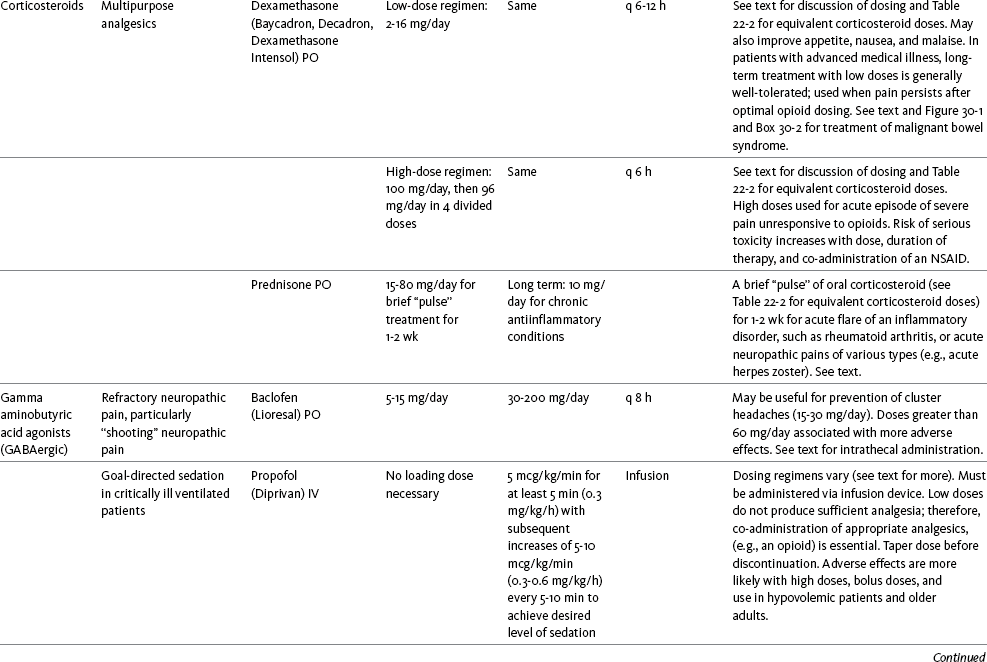

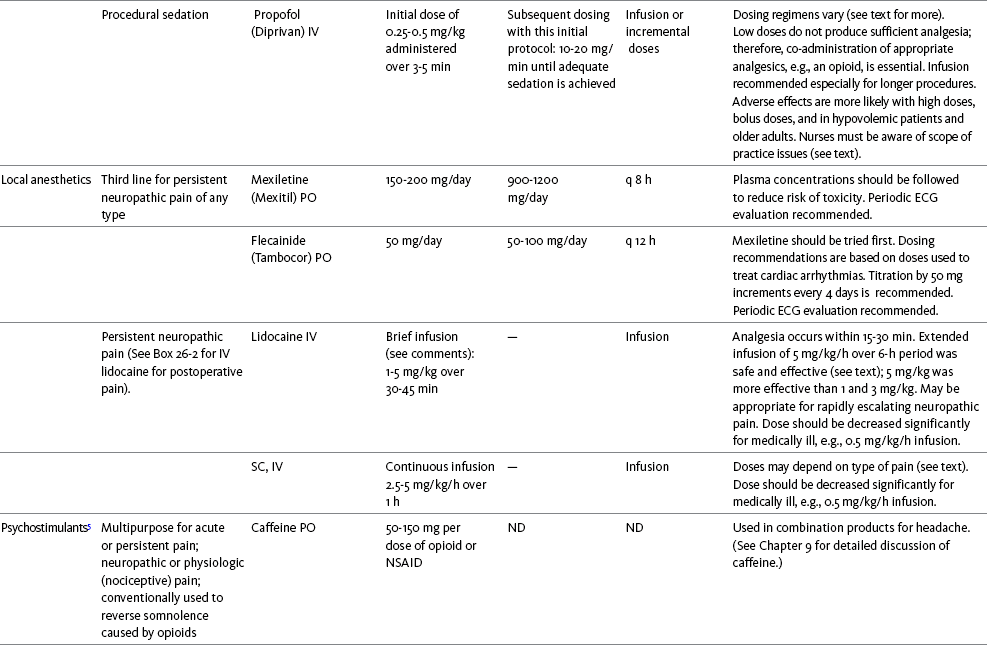

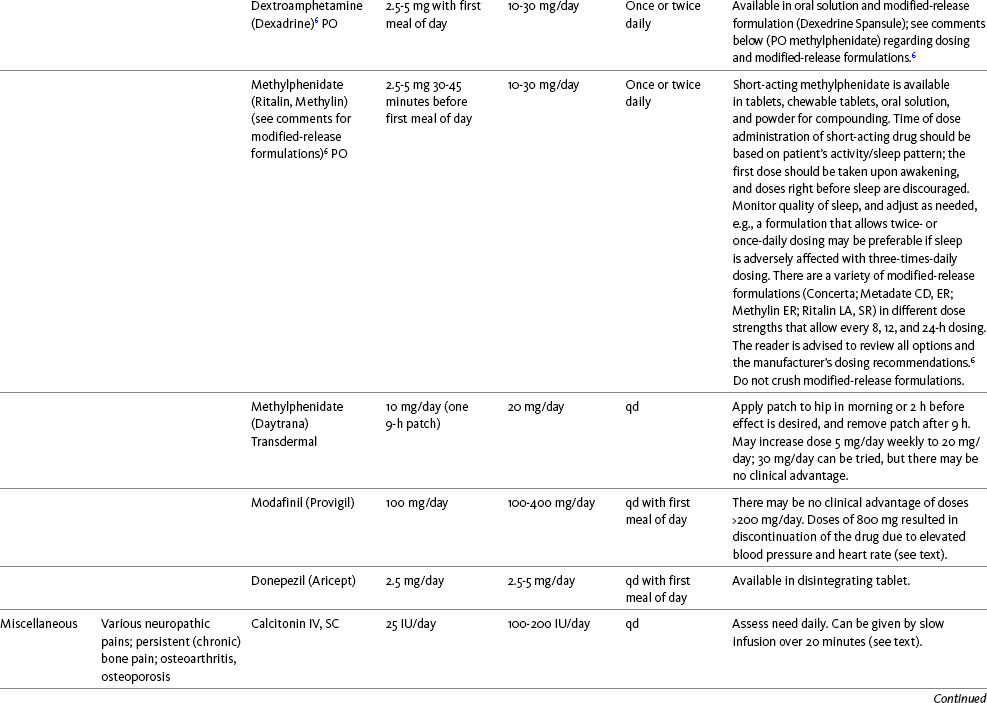

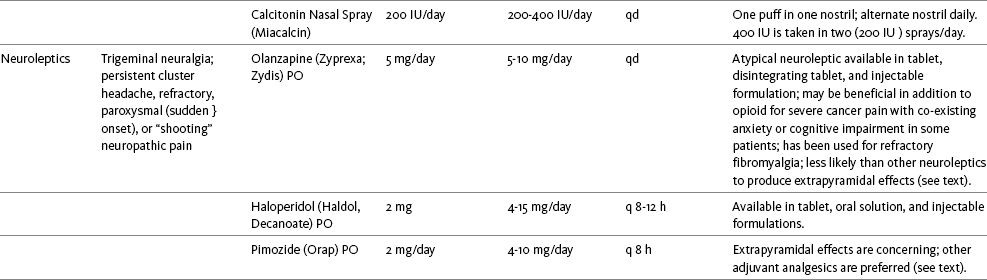

Table V-1

Selected Adjuvant Analgesics1-4

IU, International unit; ND, no data; PO, oral; q, every; qd, every day; SC, subcutaneous

1Older adults are more sensitive than younger adults to adverse effects of many of the adjuvant agents; initiate therapy with lower starting doses, and titrate slowly.

2Dose escalation should be gradual and individualized based on assessment of both pain and adverse effects.

3Doses should be gradually tapered before discontinuation of most adjuvant analgesics.

4Take single doses or largest dose of sedating medication before longest sleep period.

5Take single or first dose of psychostimulant upon awakening or after longest sleep period.

6It is generally recommended that titration with a short-acting formulation be done before switching to a modified-release formulation of a drug. Switching may be done when the available dosage of the modified-release formulation corresponds with the titrated dose of the short-acting formulation (e.g., 8-hour dose of the modified-release formulation corresponds with the 8-hour titrated dose of the short-acting formulation).

From Pasero, C., & McCaffery, M. Pain assessment and pharmacologic management, pp. 748-756, St. Louis, Mosby. Data from Ackerman, L. L., Follett, K. A., & Rosenquist, R. W. (2003). Long-term outcomes during treatment of chronic pain with intrathecal clonidine or clonidine/opioid combinations. J Pain Symptom Manage, 26(1), 668-677; Argoff, C. E., Backonja, M. M., Belgrade, M. J., et al. (2006). Consensus guidelines: Treatment planning and options. Diabetic peripheral neuropathic pain. Mayo Clin Proc, 81(Suppl 4), S12-S25; Backonja, M., & Glanzman, R. L. (2003). Gabapentin dosing for neuropathic pain: evidence from randomized, placebo-controlled clinical trials, Clin Ther, 25(1), 81-104; Brush, D. R., & Kress, J. P. (2009). Sedation and analgesia for the mechanically ventilated patient. Clin Chest Med, 30(1), 131-141; Carrazana, E, & Mikoshiba, I. (2003). Rationale and evidence for the use of oxcarbazepine in neuropathic pain. J Pain Symptom Manage, 25(Suppl 5), S31-S35; Clinical Pharmacology Online. Gold Standard, Inc. Available at http://clinicalpharmacology.com. Accessed March 1, 2009; Dworkin, R. H., O’Connor, A. B., Backonja, M., et al.: Pharmacologic management of neuropathic pain: evidence-based recommendations, Pain, 132, 237-251, 2007; Eisenach, J. C., Hood, D. D., & Curry, R. (2000). Relative potency of epidural to intrathecal clonidine differs between acute thermal pain and capsaicin-induced allodynia. Pain, 84(1), 57-64; Elliott, J. A. (2009). α2-agonists. In H. S. Smith (Ed.), Current therapy in pain, Philadelphia, Saunders; Epstein, J. B., Epstein, J. D., Epstein, M. S., et al. (2006). Oral doxepin rinse: The analgesic effect and duration of pain reduction in patients with oral mucositis due to cancer therapy. Anesth Analg, 103(2), 465-470; Gilron, I. (2006). Review article: The role of anticonvulsant drugs in postoperative pain management: A bench-to-bed-side perspective. Can J Anesth, 53(6), 562-571; Guay, D. R. (2001). Adjunctive agents in the management of chronic pain. Pharmacotherapy, 21(9), 1070-1080; Harris, J. D., & Kotob, F. (2006). Management of opioid-related side effects. In O. A. de Leon-Casasola (Ed.), Cancer pain. Pharmacological, interventional and palliative care approaches, Philadelphia, Saunders; Ho, K. Y., Gan, T. J., & Habib, A. S. (2006). Gabapentin and postoperative pain—A systematic review of randomized controlled trials. Pain, 126(1-3), 91-101; Ilfeld, B. M., Morey, T. E., & Enneking, F. K. (2003). Continuous infraclavicular perineural infusion with clonidine and ropivacaine compared with ropivacaine alone: A randomized, double-blinded, controlled study. Anesth Analg, 97(3), 706-712; Kim, S. W., Shin, I. S., Kim, J. M., et al. (2008). Effectiveness of mirtazapine for nausea and insomnia in cancer patients with depression. Psychiatry Clin Neurosci, 62(1), 75-83; Lacy, C. F., Armstrong, L. L., Goldman, M. P., et al. (Eds.). (2008). Drug information handbook, ed 17, Hudson, OH, Lexi-Comp Inc; Maizels, M., & McCarberg, B. (2005). Antidepressants and antiepileptic drugs for chronic non-cancer pain. Am Fam Physician, 71(3), 483-490; May, A., Leone, M., Afra, J., et al. (2006). EFNS guidelines on the treatment of cluster headache and other trigeminal-autonomic cephalalgias. Eur J Neurol, 13(10), 1066-1077; Moss, J., & Glick, D. (2005). The autonomic nervous system. In R. D. Miller (Ed.), Miller’s anesthesia, ed 6, Philadelphia, Elsevier; Moulin, D. E., Clark, A. J., Gilron, I., et al. (2007). Pharmacological management of chronic neuropathic pain—Consensus statement and guidelines from the Canadian Pain Society. Pain Res Manag, 12(1), 13-21; Odom-Forren, J., & Watson, D. (2005). Practical guide to moderate sedation/analgesia. St. Louis, Mosby; Reves, J., Glass, P. S. A., Lubarsky, D. A., et al. (2005). Intravenous nonopioid anesthetics. In R. D. Miller (Ed.), Miller’s anesthesia, ed 6, Philadelphia, Churchill Livingstone; Semenchuk, M. R., & Sherman, S. (2000). Effectiveness of tizanidine in neuropathic pain: An open-label study. J Pain, 11(4), 285-292; Sharma, S., Rajagopal, M. R., Palat, G., et al. (2009). A phase II pilot study to evaluate use of intravenous lidocaine for opioid-refractory pain in cancer patients. J Pain Symptom Manage, 37(1), 85-93; Silberstein, S. D., Neto, W., Schmitt, J., et al. (2004). Topiramate in migraine prevention: Results of a large, controlled trial. Arch Neurol, 61(4), 490-495; Stacey, B. R., Dworkin, R. H., Murphy, K., et al. (2008). Pregabalin in the treatment of refractory neuropathic pain: Results of a 15-month open-label trial. Pain Med, 9(8), 1202-1208; Tremont-Lukats, I. W., Challapalli, V., McNicol, E. D., et al. (2005). Systemic administration of local anesthetics to relieve neuropathic pain: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Anesth Analg, 101(6), 1738-1749;Tremont-Lukats I.W., Hutson, P. R., & Backonja, M. (2006). A randomized, double-masked, placebo-controlled pilot trial of extended IV lidocaine infusion for relief of ongoing neuropathic pain. Clin J Pain, 22(3), 266-271; White, P. F., Tufanogullari, B., Taylor, J., et al. (2009). The effect of pregabalin on postoperative anxiety and sedation levels: A dose-ranging study. Anesth Analg, 108(4), 1140-1145; Zed, P. J., Abu-Laban, R. B., Chan, W. W. Y., et al. (2007). Efficacy, safety and patient satisfaction of propofol for procedural sedation and analgesia in the emergency department: A prospective study. Can J Emerg Med, 9(6), 421-427. Pasero C, McCaffery M. May be duplicated for use in clinical practice.

Methylphenidate (Sarhill, Walsh, Nelson, 2001) and the newer agent modafinil (Prommer, 2006) are most commonly used to counteract sedation and fatigue in cancer populations. Clinical reviews discuss their usefulness in reducing opioid-induced sedation and improving fatigue and overall well-being, but more studies are needed to measure their efficacy in the treatment plans of individuals with pain (Bruera, Neumann, 1998; Fishbain, Cutler, Lewis, et al., 2004a; Reissig, Rybarczyk, 2005; Shaiova, 2005). This was confirmed in a Cochrane Collaboration Review that concluded that methylphenidate has been shown to improve concentration and is effective for fatigue in cancer patients based on studies with small sample sizes, and further research was encouraged (Minton, Stone, Richardson, et al., 2008). A review of the literature between 1996 and 2002 concluded that methylphenidate effectively attenuated opioid-induced somnolence, augmented opioid analgesia, treated depression, and improved cognitive function in cancer patients and recommended its use in palliative care (Rozans, Dreisbach, Lertora, et al., 2002).

Methylphenidate has also been used in the acute care setting. An interesting publication reported that methylphenidate facilitated the weaning from mechanical ventilation in 5 of 7 patients who exhibited psychomotor retardation associated with markedly depressed mood (Rothenhausler, Ehrentraut, von Degenfeld, et al., 2000). The drug has also been researched for treatment of postanesthesia shivering, though it is rarely used for this purpose as more effective drugs are available (Kranke, Eberhart, Roewer, et al., 2004).

The use of modafinil is gaining more popularity in practice, most likely because the drug has been shown to be very effective in treating fatigue and increasing alertness (Prommer, 2006). One randomized controlled trial found that modafinil decreased fatigue and increased “alertness” and “energy” in 71% of those given the drug, compared with 18% of those given a placebo, in the immediate postoperative period following general anesthesia (Larijani, Goldberg, Hojat, et al., 2004). The drug was well-tolerated, and those in the modafinil group experienced less pain and nausea. The drug is especially effective for cognitive impairment that can accompany both analgesic therapy and chemotherapy in cancer patients (Biegler, Chaoul, Cohen, 2009). A comprehensive evidence-based review of modafinil provides several indications and guidelines for its use (Kumar, 2008). Further research is needed to establish its analgesic potential.

Dextroamphetamine is used less today than in the past as the newer and better-tolerated psychostimulants have become available. A placebo-controlled study comparing dextroamphetamine, caffeine, and modafinil in healthy volunteers who were subjected to 44 hours of continuous wakefulness found that duration of vigilance and wakefulness were shortest with caffeine and longest with dextroamphetamine (Killgore, Rupp, Grugle, et al., 2008). Adverse effects with modafinil were similar to placebo, caffeine was associated with the most adverse effects, and restorative sleep was adversely affected by dextroamphetamine. A randomized controlled trial administered dextroamphetamine 10 mg or placebo to fatigued older adults with advanced cancer receiving palliative care (Auret, Schug, Bremner, et al., 2009). Although improvements in fatigue were noted on the second day, there were no significant differences in fatigue or quality of life at the end of the 8-day study period.

Caffeine has been used for many years to treat opioid-induced sedation or somnolence related to other adjuvant analgesics. It also can reduce general fatigue associated with drug therapies or disease states. More importantly, research has shown that caffeine has analgesic properties, for example, in the treatment of headaches. Clinical trials indicate that caffeine in doses of more than 65 mg may enhance the analgesia of other agents (Zhang, 2001). Caffeine is widely available in both medications and food items, particularly coffee and tea. See Chapter 9 for a more detailed discussion of the use of caffeine as an adjuvant analgesic, and refer to Table 9-1 (p. 241) for dietary sources of caffeine and Table 9-2 (pp. 242-245) for nonopioid analgesics that contain caffeine.

Patients who require psychostimulants to counteract sedation caused by their opioid and adjuvant therapy should be monitored for benefits. These include assessing for a decrease in daytime sleepiness, reduction in the number of daytime naps, feelings of having more energy, improved physical stamina during the day, better mental concentration, and ability to engage in social activities. It is equally important to watch for adverse effects such as insomnia, nervousness, feelings of uneasiness, tachycardia, decreased appetite, and weight loss. If any of these occur, depending on how severe, dose adjustments can always be made to the therapy.

Donepezil, an oral acetylcholinesterase inhibitor approved for the treatment of Alzheimer’s disease, is the drug in this class that is most frequently tried as a strategy to reduce opioid-induced sedation. In one case series, 6 patients with cancer pain who were experiencing marked sedation from their pain therapy (opioid doses higher than 200 mg of morphine equivalents per day) had notable improvements after taking donepezil (Slatkin, Rhiner, Bolton, 2001). Patients indicated fewer episodes of spontaneous sleeping during the day, fewer myoclonic twitches, and better function and social interaction. Sleep at night also improved. Clearly, more research is needed to measure the benefits of this agent for opioid- and adjuvant-induced sedation.

Calcitonin

The use of calcitonin for bone pain has been previously addressed in Chapter 29. Additionally, this agent has also been used for the treatment of other types of pain syndromes. Unfortunately, there are insufficient data to support widespread use beyond bone pain. It has little to no effectiveness for phantom limb pain (Albazaz, Wong, Homer-Vanniasinkam, 2008; Halbert, Crotty, Cameron, 2003; Smith, Dubin, Parikh, 2009). However, intranasal calcitonin was shown to relieve pain with movement and rest and improve ability to work in patients with complex regional pain syndrome (Gobelet, Waldburger, Meier, et al., 1992; Perez, Kwakkel, Zuurmond, 2001). It has also been used to effectively treat intractable painful diabetic neuropathy (Quatraro, Minei, De Rosa, et al., 1992; Zieleniewski, 1990). The literature suggests that it may be useful for acute neuropathic pain (Gray, 2008) and pain from trigeminal neuralgia (Qin, Cai, Yang, 2008). The exact mechanisms for possible analgesic effects for neuropathic pain remain unknown. The optimal dose and dosing frequency for calcitonin are not established (Perez, Kwakkel, Zuurmond, 2001). Dosing recommendations discussed previously in relation to bone pain may be used for neuropathic pain (see Chapter 39).

Neuroleptics

In an evidence-based review, it was concluded that some neuroleptics, including at least one of the newer, so-called atypical neuroleptics, may have analgesic activity, but there are far too few randomized controlled and other clinical trials to draw definitive conclusions (Fishbain, Cutler, Lewis, et al., 2004b). There is no clear evidence that the phenothiazines (e.g., chlorpromazine [Thorazine], fluphenazine [Prolixin]) specifically either relieve pain or potentiate opioid analgesia (American Pain Society [APS], 2003).

Olanzapine (Zyprexa) is a newer, so-called atypical neuroleptic and has a somewhat better safety profile than the traditional neuroleptics. This drug may have some benefit when added to opioid therapy in those with severe cancer pain associated with cognitive impairment or anxiety (Khojainova, Santiago-Palma, Kornick, et al., 2002). In a case series, olanzapine also was reported to be effective in rapidly aborting episodic and persistent cluster headache (Rozen, 2001) and relieving refractory fibromyalgia symptoms, including pain (Kiser, Cohen, Freedenfeld, et al., 2001).

Evidence that traditional neuroleptics other than methotrimeprazine are analgesic is equally sparse. Pimozide (Orap) was effective in patients with trigeminal neuralgia, and this has suggested a role for neuroleptics in patients with refractory neuropathic pain (Lussier, Portenoy, 2004). Given its adverse effect liability, pimozide specifically is not considered. Other neuroleptics, such as haloperidol (Haldol) and fluphenazine, would be preferred in this rare circumstance.

Mechanism of Action

The mechanism of neuroleptic analgesia is unknown, but may involve the effect of dopaminergic blockade on endogenous pain-modulating systems (Lussier, Portenoy, 2004) (see Section I). Dopamine receptors, specifically the D2 subtype, are represented among the numerous pathways that subserve pain modulation (Yaksh, 2006). Studies in animals have suggested that selective dopamine antagonists can potentiate morphine analgesia, and controlled clinical trials have demonstrated that metoclopramide, a relatively selective blocker of the D2 receptor, is mildly analgesic in humans (Kandler, Lisander, 1993; Rosenblatt, Cioffi, Sinatra, et al., 1991). This evidence, however, does not confirm that a dopaminergic mechanism underlies the analgesic effects of neuroleptic drugs, because all these drugs interact with other receptors that could potentially mediate analgesic effects. Metoclopramide has a dopaminergic mechanism, and there is no strong evidence that this drug is analgesic (Gupta, 2006).

Indications

Given the lack of supporting data, neuroleptics are very rarely considered for a primary pain indication. For patients with advanced illness who have pain associated with agitation, anxiety, or nausea, the use of one of these drugs is separately indicated and its effects on pain can be tracked. Among those without these other indications, the use of a neuroleptic for pain would only be considered after many trials of other drug strategies proved ineffective.

Dose Selection

The neuroleptics are started at low doses and increased to whatever dose the literature suggests is usually analgesic, and then discontinued if no analgesia ensues (Lussier, Portenoy, 2004). For example, low initial doses of fluphenazine can be escalated to 1 to 2 mg 3 times daily, and the dose of haloperidol can be slowly increased to 2 to 5 mg 2 to 3 times a day.

Adverse Effects

Common adverse effects of neuroleptic drugs include sedation, orthostatic dizziness, and anticholinergic effects (Lussier, Portenoy, 2004). Some patients experience mental clouding or confusion. Phenothiazines, such as chlorpromazine and fluphenazine, are more likely to produce these effects than other subclasses, such as the butyrophenones (e.g., haloperidol). The sedation produced by the neuroleptics can be additive to other CNS depressants.

The possibility of extrapyramidal adverse effects is perhaps the greatest concern in the clinical use of neuroleptic drugs (Lussier, Portenoy, 2004). The incidence of these disorders varies with the drug, duration of therapy, and dose. Fluphenazine and haloperidol are more likely to produce these effects than olanzapine (Tardy, Baldessarini, Tazari, 2002). The most serious extrapyramidal reaction is the neuroleptic malignant syndrome that is characterized by rigidity, autonomic instability, and encephalopathy. Successful management requires prompt diagnosis, discontinuation of the neuroleptic, and intensive supportive measures. The use of dantrolene (Dantrium) and bromocriptine (Parlodel) has been suggested in severe cases.

Other extrapyramidal effects can be distressing or seriously impair function. These include acute dystonic reactions (muscle contraction and jerking movements), akathisia (restlessness), parkinsonism, and tardive dyskinesia. The management of these complications usually involves discontinuation of the neuroleptic, with or without the administration of an anticholinergic drug, such as benztropine (Lussier, Portenoy, 2004).

Benzodiazepines

The benzodiazepines, clonazepam (Klonopin) (Fishbain, Cutler, Rosomoff, et al., 2000; Wiffen, Collins, McQuay, et al., 2005) and alprazolam (Xanax) (Fernandez, Adams, Holmes, 1987) have been used in the management of both musculoskeletal pains and neuropathic pains. Although clonazepam often is considered specifically for neuropathic pain, a critical review finds little support (Dellemijn, Fields, 1994; Reddy, Patt, 1994) (see Chapter 23 for more research and discussion of clonazepam). Negative findings also have been reported in an early controlled trial of lorazepam (Ativan) for postherpetic neuralgia (Max, Schafer, Culnane, et al., 1988) and in a small controlled repeated-dose study of oral chlordiazepoxide (Librium) for persistent pain (Yosselson-Superstine, Lipman, Sanders, 1985). Thus, the evidence for benzodiazepine analgesia is limited and conflicting, leading the APS (2003) to conclude that benzodiazepines are not effective analgesics except for muscle spasm (see Chapter 25).

Nonetheless, it must be acknowledged that clonazepam, and sometimes alprazolam, are tried in cases of refractory neuropathic pain on the basis of anecdotal experience, the relative safety of these drugs, and the common coexistence of pain and anxiety. If this is considered, clinicians should recognize the limited supporting evidence. The wider use of benzodiazepines as adjuvant analgesics is not warranted.

As discussed previously, the evidence for use of benzodiazepines as muscle relaxants also is minimal (see Chapter 25). Diazepam (Valium) and other benzodiazepines are widely used for this purpose, but benefits are limited, especially when given orally.

Adenosine

Adenosine (Adenocard, Adenoscan) is an antiarrhythmic agent commercially available for IV administration. The basis for its analgesic potential lies within the fact that adenosine is an important modulator of neurotransmission associated with many physiologic functions, including the regulation of arousal and sleep, anxiety, cognition, and memory, and may contribute to the etiology of pathologic pain (Ribeiro, Sebastiao, de Mendonca, 2002; Sawynok, Liu, 2003). Early research of adenosine suggested that the drug had analgesic effects for postoperative pain (Segerdahl, Ekblom, Sandelin, et al., 1995) and neuropathic pain (Sollevi, Belfrage, Lundeberg, et al., 1995). A later comprehensive review of adenosine also supported a role in relieving both postoperative and persistent neuropathic pain states (Hayashida, Fukuda, Fukunaga, 2005). Although adenosine has been identified as having potential as an intrathecal analgesic, further research is needed to more clearly define its place in pain management by this route of administration (Schug, Saunders, Kurowski, et al., 2006).

Antihistamines

Many antihistamines are available, including diphenhydramine (Benadryl), hydroxyzine (Vistaril parenterally), phenyltoloxamine (Phenylgesic, a nonprescription cold remedy), pyrilamine (an ingredient in several cold remedies [e.g., Codimal PH syrup, ND-Gesic tablets]), and orphenadrine (Norflex). Orphenadrine is an analogue of diphenhydramine and is combined with aspirin and caffeine for analgesia but is classified as a skeletal muscle relaxant (see Chapter 25). There is little evidence that this drug, or other antihistamines, relax muscles or effectively relieve pain.

A randomized study of women undergoing hysterectomy found a lower incidence of severe nausea with perioperative diphenhydramine but no differences in pain or opioid consumption compared with placebo (Lin, Yeh, Yeh, et al., 2005). At best, diphenhydramine has been observed anecdotally to augment the treatment of pain that has failed to respond to opioids and other adjuvant analgesics (Santiago-Palma, Fischberg Kornick, et al., 2001). Suggested therapy can start at 25 mg of oral or parenteral diphenhydramine every 6 to 8 hours, and be titrated to effect. However, the coadministration of diphenhydramine with opioids is problematic in the postoperative setting because this can increase the risk of excessive sedation and respiratory depression (Anwari, Iqbal, 2003); increased monitoring of sedation levels is required with this practice (see Chapter 19 for more information).

The purported analgesic properties of hydroxyzine, which has been traditionally combined with an opioid for an opioid dose-sparing effect, have never been confirmed (Gordon, 1995). Studies reporting analgesic activity for this agent suffer from major methodologic flaws, including the lack of placebo-controlled trials and scientific rigor in analyzing results. These have compromised the ability to draw definitive conclusions about its benefits (Glazier, 1990). With doses that may contribute to pain relief, hydroxyzine would have the potential for inducing significant sedation, which adds to the adverse effects of opioids, but would not be reversed with naloxone (Gordon, 1995). Further, when given parenterally, it can cause significant local pain and tissue damage. Antihistamines must also be used with caution in older patients as they have increased sensitivity to the anticholinergic and sedative effects of these drugs (see Table 13-4 on p. 336). Clinical experience suggests that treatment with antihistamines should be reserved for treating anxiety and opioid-induced nausea and pruritus in some patients (see Chapter 19).

Botulinum Toxin Type A

Botulinum toxin type A (Botox) is a fermented product derived from Clostriduium botulinum, an anaerobic spore-forming bacterium (Setler, 2002). It is approved for administration by injection for several conditions, including cervical dystonia, hemifacial spasm, and blepharospasm (Lew, 2002). Injection of botulinum produces partial chemical denervation and localized reduction in muscle activity. The toxin is used to treat spasticity (O’Brien, 2002), and clinical reports, open-label trials, and a few randomized controlled studies have shown that it may be effective for some types of persistent pain when more conservative approaches fail to provide relief (Arezzo, 2002; Gajraj, 2005; Smith, Audette, Royal, 2002). When effective, the toxin provides long-term (weeks) relief with a relatively low incidence of adverse effects (Smith, Audette, Royal, 2002). Adverse effects are usually transient but can last for months and include localized muscle weakness and pain at the injection site, skin rash, pruritus, and flulike symptoms. Prompted by reports that the botulinum toxin may spread from the area of injection to other parts of the body, the United States Food and Drug Administration (U.S. FDA) announced label changes in 2009 for all botulinum toxin products, which included a boxed warning. Reported symptoms were similar to those of botulism, including unexpected loss of strength or muscle weakness, hoarseness or trouble talking, trouble saying words clearly, loss of bladder control, trouble breathing, trouble swallowing, double vision, blurred vision, and drooping eyelids.

Myofascial pain syndrome and fibromyalgia have been shown to be responsive to botulinum toxin injection into trigger points or tender points (Smith, Audette, Royal, 2002). A case report described successful use of botulinum injection for persistent perineal pain (Gajraj, 2005). It has been suggested as a possible treatment for chronic whiplash-associated disorder (Freund, Schwartz, 2002). A small randomized trial of postwhiplash neck pain found the best efficacy if the toxin is administered within 1 year of the injury (Braker, Yariv, Adler, et al., 2008). Whereas botulinum treatment has been used to relieve back pain in select patients (Difazio, Jabbari, 2002), a placebo-controlled, randomized study found that single-dose treatment without physical therapy is ineffective for persistent neck pain (Wheeler, Goolkasian, Gretz, 2001). Those who were injected experienced a high incidence of adverse effects in this study; further research on multidose therapy was encouraged.

Botulinum treatment also has been considered a viable option for persistent headaches, with the advantage of a lack of systemic effects associated with conventional treatments (Loder, Biondi, 2002). However, a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial found it ineffective for the treatment of tension-type headaches (Schulte-Mattler, Krack, BoNTTH Study Group, 2004), and another well-controlled study showed that it had no efficacy for episodic migraine headaches (Saper, Mathew, Loder, et al., 2007).

The underlying mechanism of the analgesic action of botulinum toxin type A is not entirely clear but is thought to be related to its ability to inhibit the release of the neurotransmitter acetylcholine from cholinergic nerve terminals (Setler, 2002). A study of human volunteers found that botulinum toxin type A preferentially targets C-fibers, blocks neurotransmitter release, and subsequently reduces pain and neurogenic inflammation (Gazerani, Pendersen, Staahl, et al., 2009). A decrease in active tender trigger points is suggested as an underlying mechanism for pain relief with soft-tissue pain syndromes (Smith, Audette, Royal, 2002). The reader is referred to a journal supplement devoted to botulinum toxin treatment for specific types of pain that might best respond, dosing guidelines, administration technique, expected responses, and adverse effects (Clinical Journal of Pain, 18[Suppl 6], 2002).

Vitamin D

Interest in vitamin D supplementation as an analgesic approach began when a number of studies suggested a link between inadequate levels of vitamin D and a higher incidence of persistent pain. A prospective study found a prevalence of vitamin D inadequacy in 26% of patients (N = 267) seeking help for diverse types of persistent pain (Turner, Hooten, Schmidt, et al., 2008). Other findings were that among patients taking opioids in this study, those with vitamin D deficiency were taking approximately twice the opioid dose and had been taking opioids 60% longer than those without a vitamin D deficiency. The underlying mechanisms of these relationships are unknown. The idea that an intervention as simple as vitamin supplementation could be used to treat persistent pain is very attractive; however, a systematic review (22 relevant studies) concluded that the well-controlled studies thus far are too small and that supporting studies are insufficient to support the hypothesis that vitamin D might be helpful for treatment of persistent pain (Straube, Moore, Derry, et al., 2009). Clearly, more research is needed to better understand how deficiencies in vitamin D might initiate and maintain pain and whether or not supplementation is helpful.

Nicotine

Antinociceptive effects of nicotine via nicotinic acetylcholine receptors distributed throughout the nervous system have been observed for many years in animal and human experimental research (Habib, White, El Gasim, et al., 2008; Perkins, Grobe, Stiller, et al., 1994; Shapiro, Jarvik, 1998); however, the use of nicotine for pain management has been limited because of associated gastrointestinal and cardiovascular (CV) adverse effects (Rowbotham, Duan, Thomas, et al., 2009). Nevertheless, a small placebo-controlled trial randomized 20 healthy women who underwent gynecologic surgery to receive an intranasal spray of saline or nicotine (3 mg) after surgery and before emergence from anesthesia and found that those who received the intranasal nicotine had no CV adverse effects, lower pain scores, and consumed less supplemental opioid during the first 24 postoperative hours than those who received placebo (Flood, Daniel, 2004).

Later studies have reported less impressive results. Patients (N = 90 nonsmokers) undergoing radical retropubic prostatectomy were randomized to receive a 7 mg transdermal nicotine patch or placebo patch behind the ear 30 to 60 minutes prior to anesthesia induction (Habib, White, El Gasim, et al., 2008). All patients received morphine IV patient-controlled analgesia (PCA) and IV ketorolac 15 mg every 6 hours postoperatively. Although those who received the nicotine patch consumed significantly less morphine, there were no differences in pain scores and incidences of nausea and vomiting compared with placebo. Another randomized control trial of nonsmokers undergoing various general surgery procedures reported transdermal nicotine patches (5 to 15 mg) applied preoperatively reduced postoperative pain scores but did not decrease the need for opioid analgesics and did not reduce the incidence of opioid-induced adverse effects (Hong, Conell-Price, Cheng, et al., 2008). An interesting study of patients undergoing surgery showed that preoperatively applied transdermal nicotine (5 to 15 mg) did not relieve postoperative pain or reduce opioid use in smokers (Olson, Hong, Conell-Price, et al., 2009). A high-dose (21 mg) transdermal nicotine patch did not improve analgesia or decrease analgesic requirements postoperatively in patients after hysterectomy, and adverse effects did not differ significantly from those associated with placebo (Turan, White, Koyuncu, et al., 2008). In contrast, the nicotine patch was associated with a reduced incidence of postoperative nausea and vomiting in another study (Ionescu, Badescu & Acalovschi, 2007).

Alcohol (Ethanol)

For centuries, alcohol has served as an analgesic in the absence of other more effective alternatives. It has been referred to as the “poor man’s pain reliever.” This practice continues today as a socially, although not medically, accepted remedy for dealing with pain. For example, according to Kotarba’s (1983) observations of social drinking in neighborhood cocktail lounges, many pain-afflicted working-class bar drinkers use alcohol as an analgesic. Some drinkers consciously take advantage of the relationship between drinking alcohol and “feeling no pain.” Years ago IV alcohol in 5% to 10% solution was used to relieve mild to moderate pain (Cutter, O’Farrell, Whitehouse, et al., 1986). The effects of IV administration appear to be the same as those that occur with oral administration.

Early research based on experimentally-induced pain suggests that the analgesia of alcohol is related to increased pain tolerance rather than decreased pain perception (Woodrow, Eltherington, 1988). The alcohol equivalent of two cocktails induced analgesia (in the form of pain tolerance) that was comparable to that of 11.6 mg of subcutaneous morphine. This occurred at a blood concentration of approximately 70 mg/100 mL. More recently, investigators proposed that G protein-activated inwardly rectifying potassium (GIRK) channels are likely involved in ethanol-induced analgesia (Ikeda, Kobayashi, Kumanishi, et al., 2002).

The therapeutic value of alcohol is extremely limited because of the intoxicating effects that accompany acute consumption and the medical problems associated with long-term use. Furthermore, alcohol used in conjunction with opioids increases sedation and may decrease respirations. Long-term use of alcohol in conjunction with acetaminophen increases the risk of hepatic damage. Use with NSAIDs increases the risk of gastric injury. Thus alcohol is not recommended as an adjuvant analgesic. However, clinicians should be aware of why patients with pain may consume alcohol and should attempt to replace the perceived benefits of alcohol with other pain relief methods.

Conclusion

The agents discussed in this chapter are rarely added to the pain treatment plan because research is lacking to support their use as analgesics. Although their use as analgesics is limited, some may provide other benefits, such as relief of anxiety and treatment of opioid-induced adverse effects, in selected patients.

Section V Conclusion

Areview of the literature revealed numerous reasons why patients do not adhere to a variety of medications prescribed for pain (Monsivais, McNeil, 2007). In addition to an introductory review of the literature, these authors examined 42 abstracts and 17 full-text articles. Some of the concerns revealed are pertinent to adjuvant analgesics and may be diminished by providing the patient with written information about their medications. (See pp. 757-758 and Patient Medication Information Forms V-1 to V-12 on pp. 759-782.) A common reason for nonadherence was high levels of concern about the medication, such as adverse effects, “dependency,” and questions about the real need for the medication. Patients also had misconceptions about how long it should take for the drug to be effective, and they would stop taking it if no benefits occurred by the expected time. Patients also feared tolerance, that is, that the medication might cease to work if taken on a regular basis.

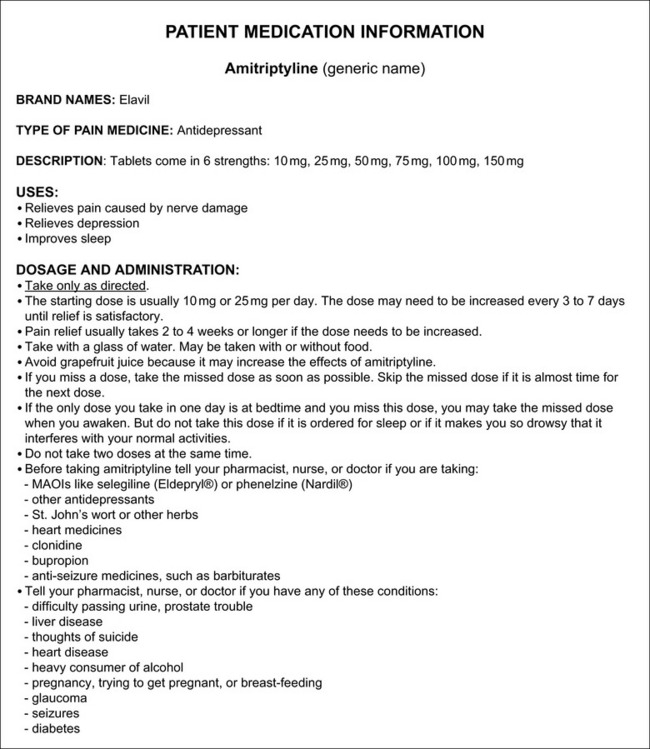

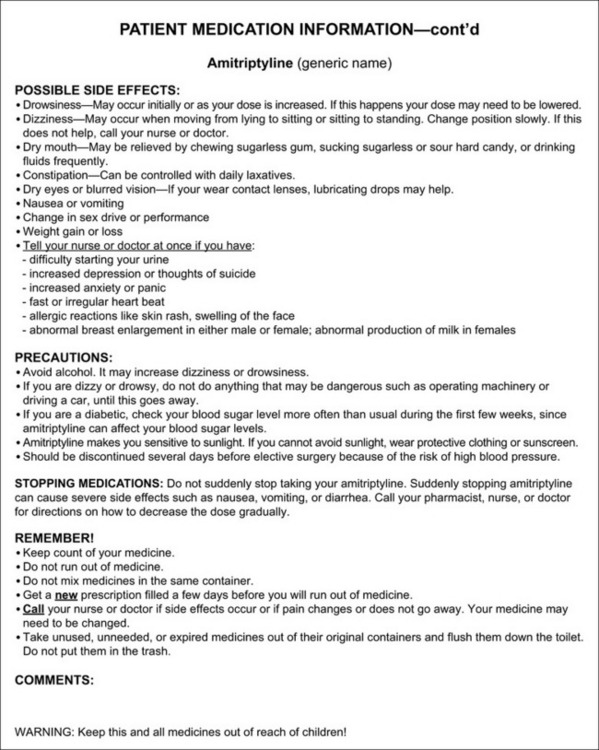

Form V-1 Patient medication information: amitriptyline. From Pasero, C., & McCaffery, M. Pain assessment and pharmacologic management, pp. 759-760, St. Louis, Mosby. McCaffery M, Pasero C. May be duplicated for use in clinical practice.

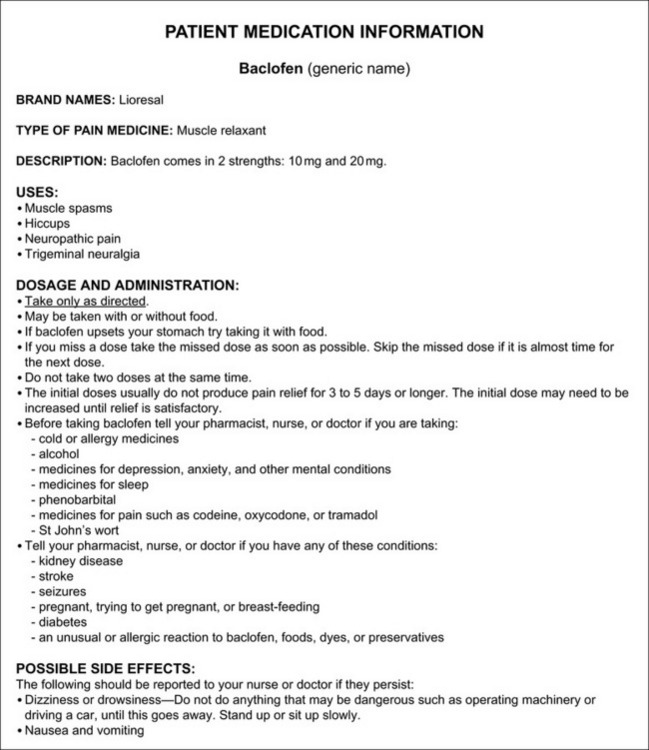

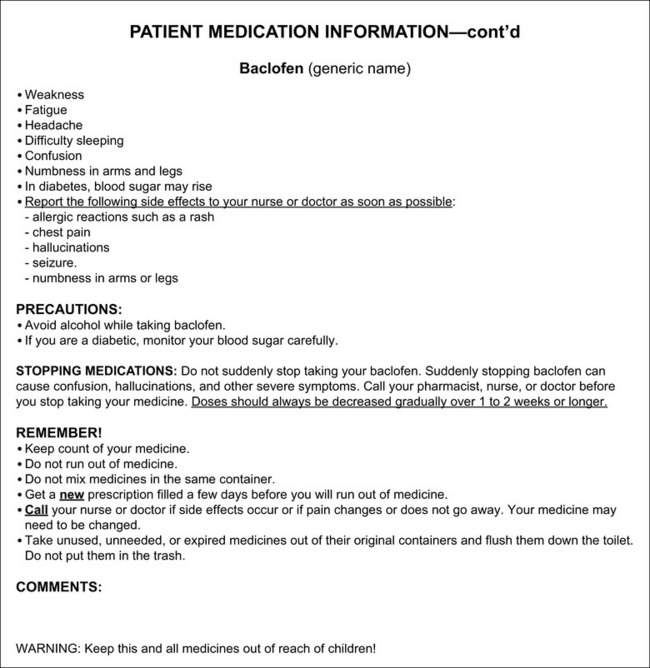

Form V-2 Patient medication information: baclofen. From Pasero, C., & McCaffery, M. Pain assessment and pharmacologic management, pp. 761-762, St. Louis, Mosby. McCaffery M, Pasero C. May be duplicated for use in clinical practice.

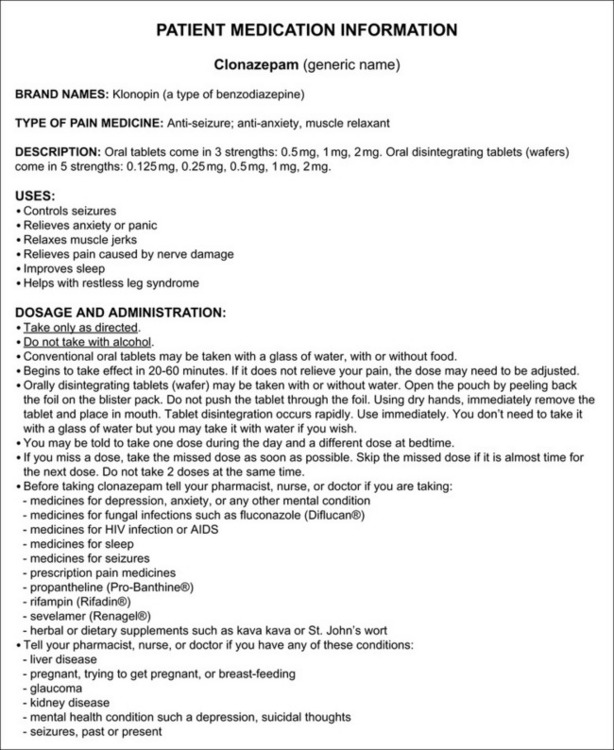

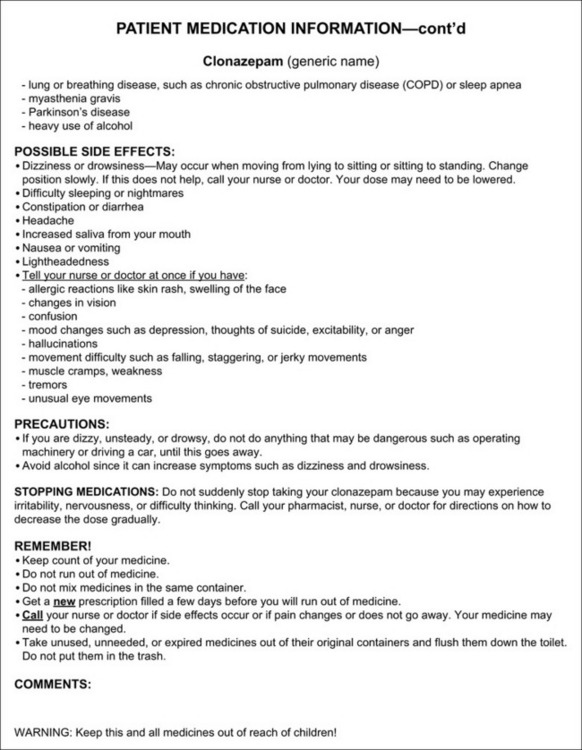

Form V-3 Patient medication information: clonazepam. From Pasero, C., & McCaffery, M. Pain assessment and pharmacologic management, pp. 763-764, St. Louis, Mosby. McCaffery M, Pasero C. May be duplicated for use in clinical practice.

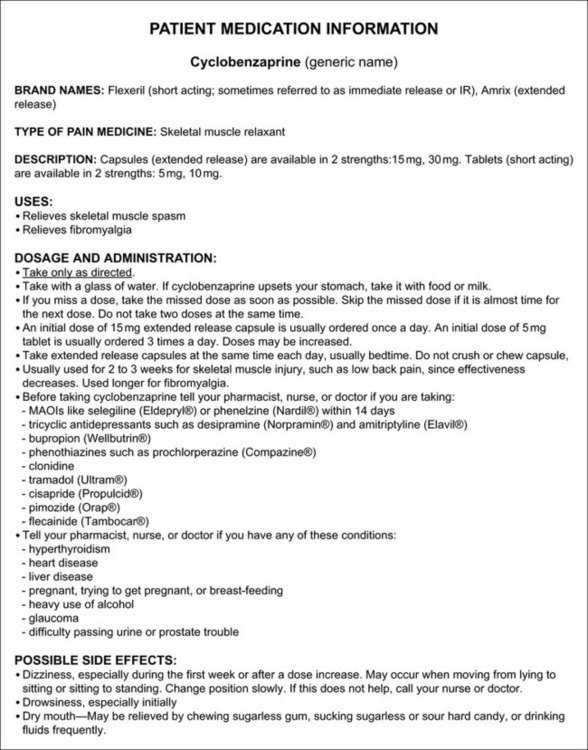

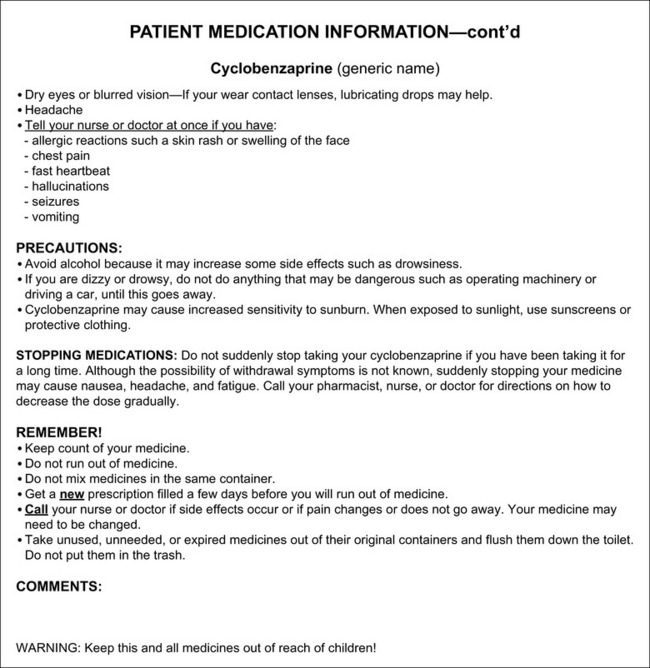

Form V-4 Patient medication information: cyclobenzaprine. From Pasero, C., & McCaffery, M. Pain assessment and pharmacologic management, pp. 765-766, St. Louis, Mosby. McCaffery M, Pasero C. May be duplicated for use in clinical practice.

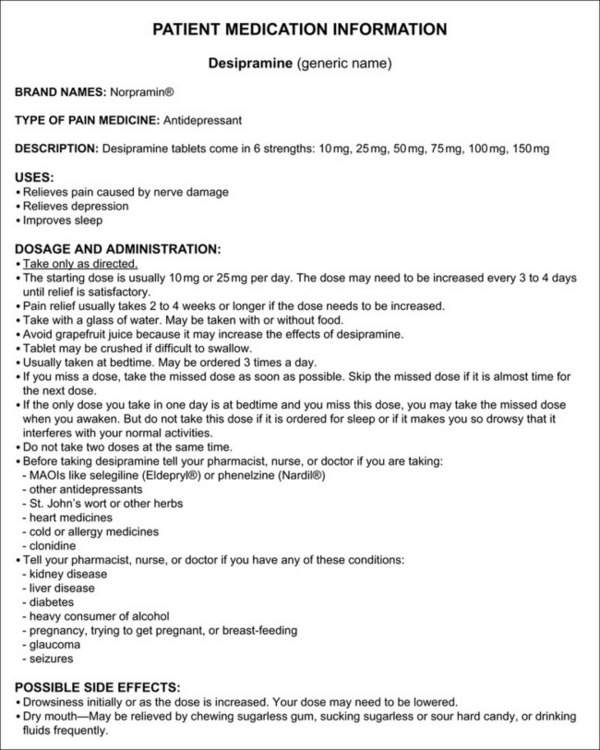

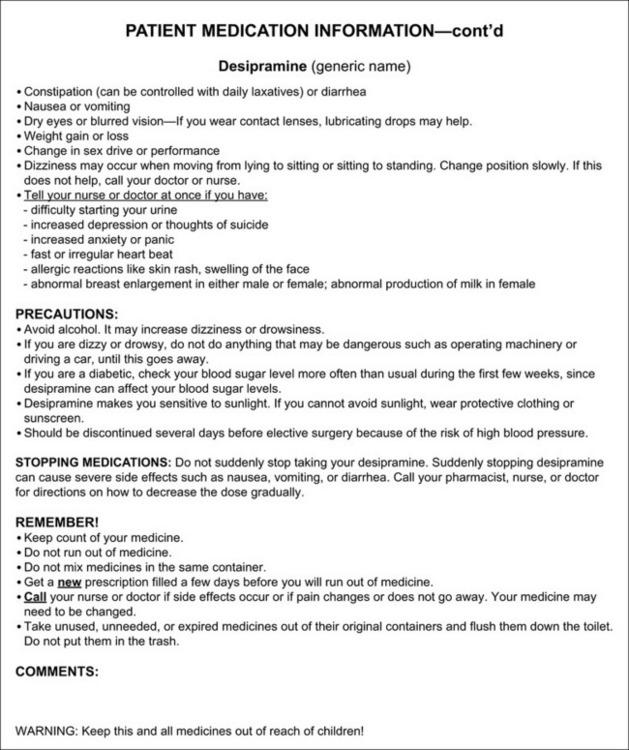

Form V-5 Patient medication information: desipramine. From Pasero, C., & McCaffery, M. Pain assessment and pharmacologic management, pp. 767-768, St. Louis, Mosby. McCaffery M, Pasero C. May be duplicated for use in clinical practice.

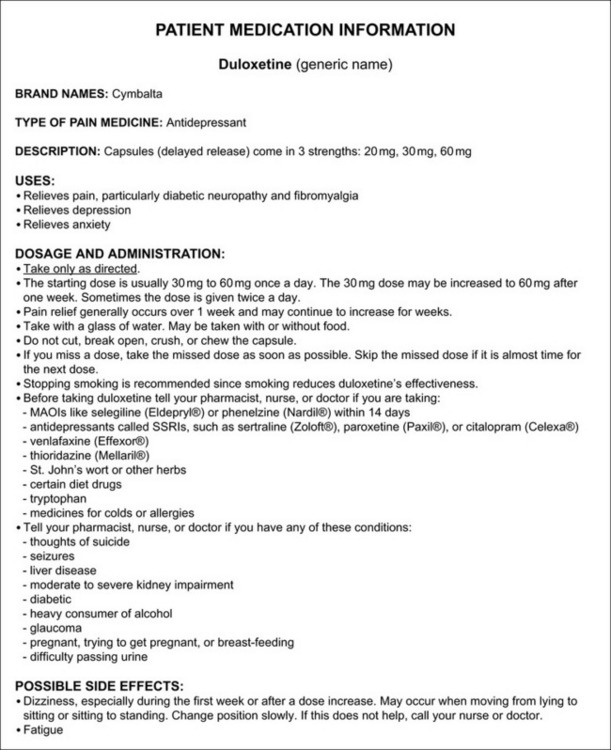

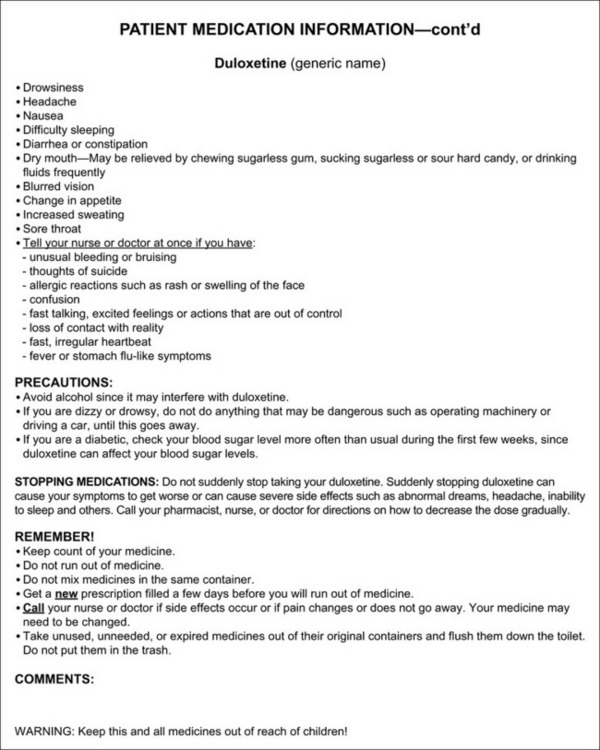

Form V-6 Patient medication information: duloxetine. From Pasero, C., & McCaffery, M. Pain assessment and pharmacologic management, pp. 769-770, St. Louis, Mosby. McCaffery M, Pasero C. May be duplicated for use in clinical practice.

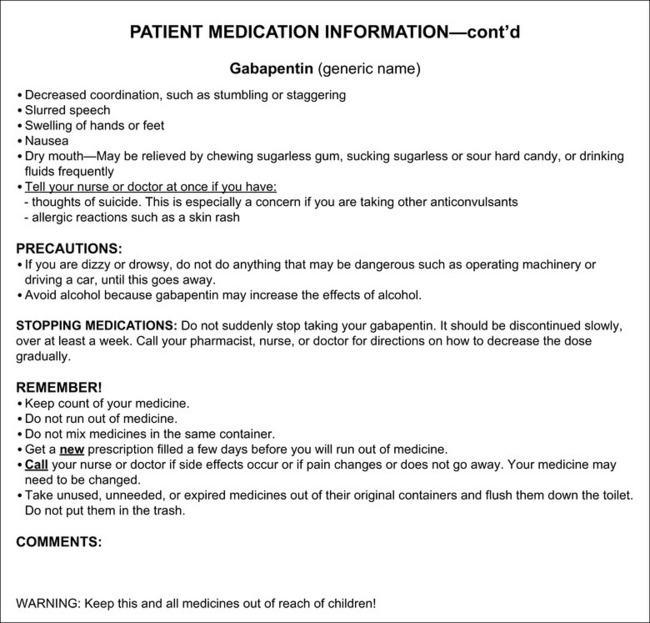

Form V-7 Patient medication information: gabapentin. From Pasero, C., & McCaffery, M. Pain assessment and pharmacologic management, pp. 771-772, St. Louis, Mosby. McCaffery M, Pasero C. May be duplicated for use in clinical practice.

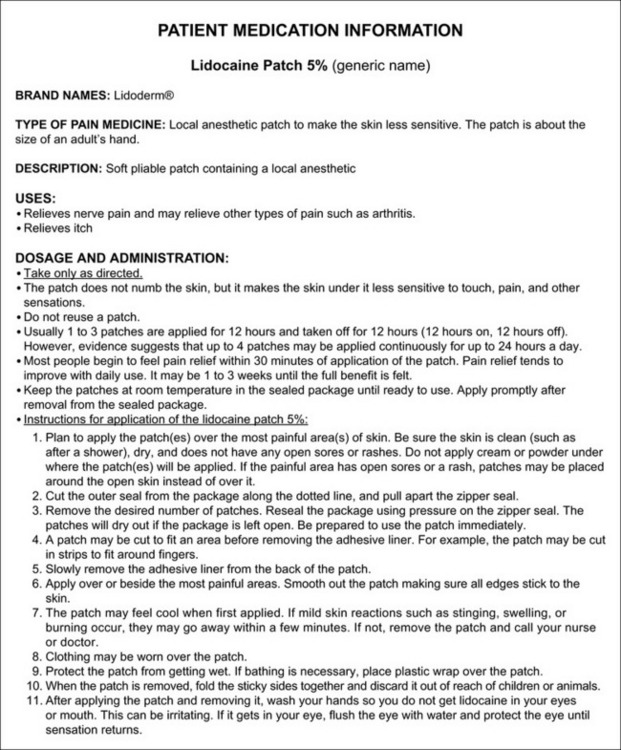

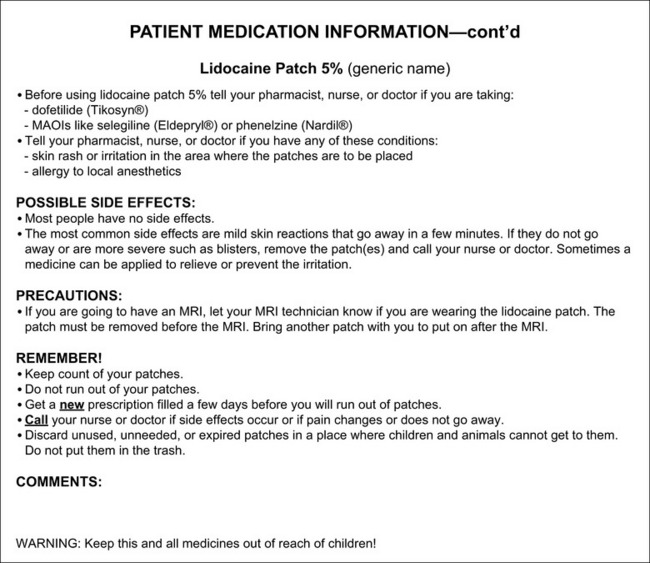

Form V-8 Patient medication information: lidocaine patch 5%. From Pasero, C., & McCaffery, M. Pain assessment and pharmacologic management, pp. 773-774, St. Louis, Mosby. McCaffery M, Pasero C. May be duplicated for use in clinical practice.

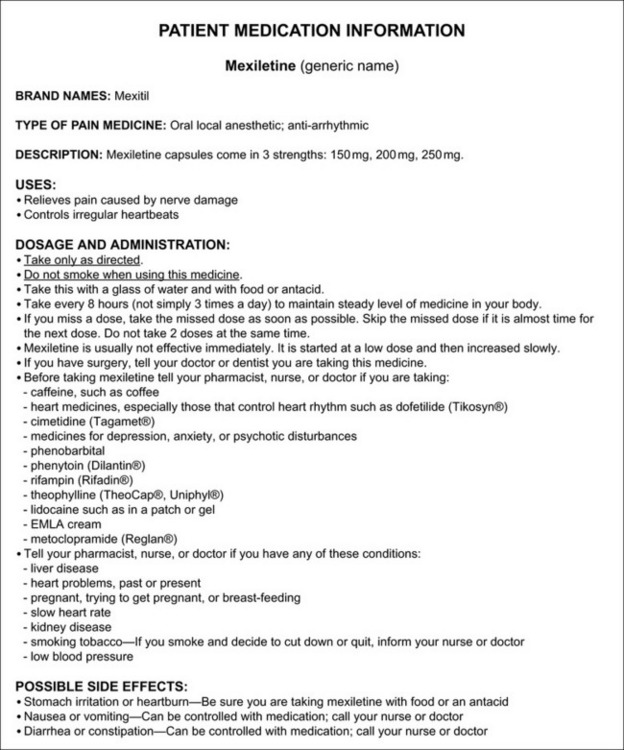

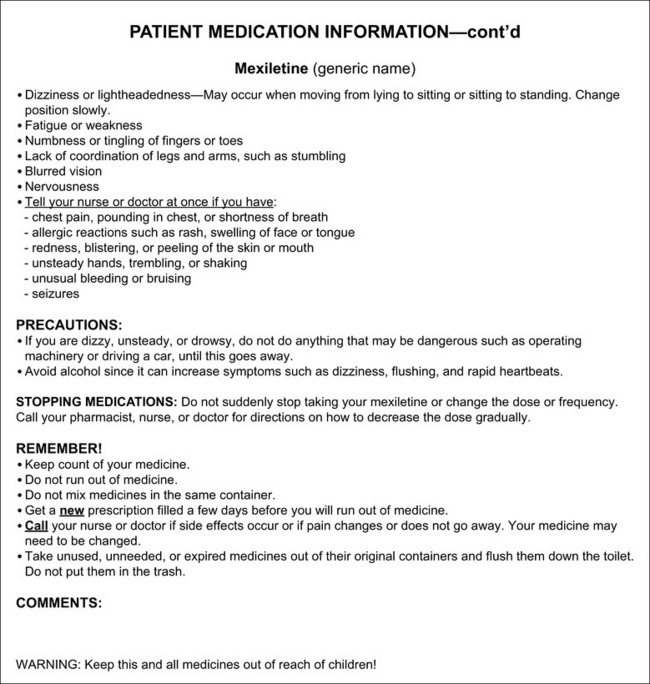

Form V-9 Patient medication information: mexiletine. From Pasero, C., & McCaffery, M. Pain assessment and pharmacologic management, pp. 775-776, St. Louis, Mosby. McCaffery M, Pasero C. May be duplicated for use in clinical practice.

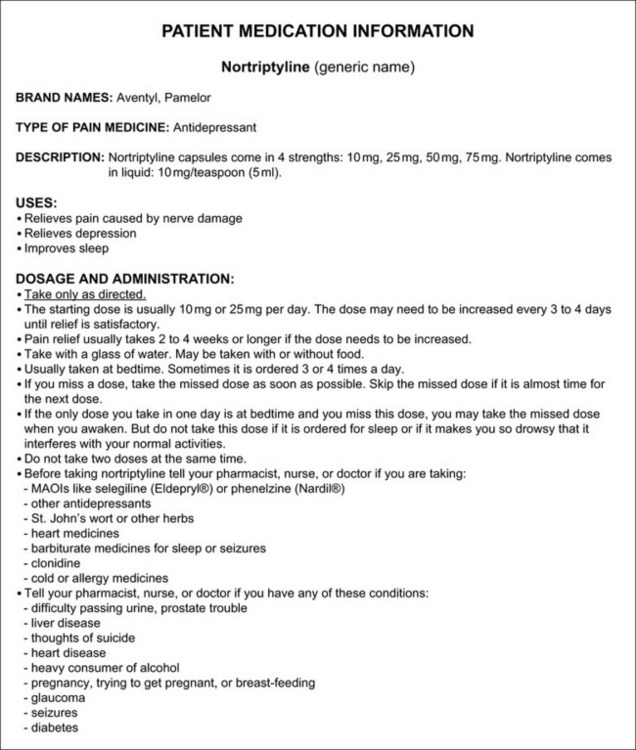

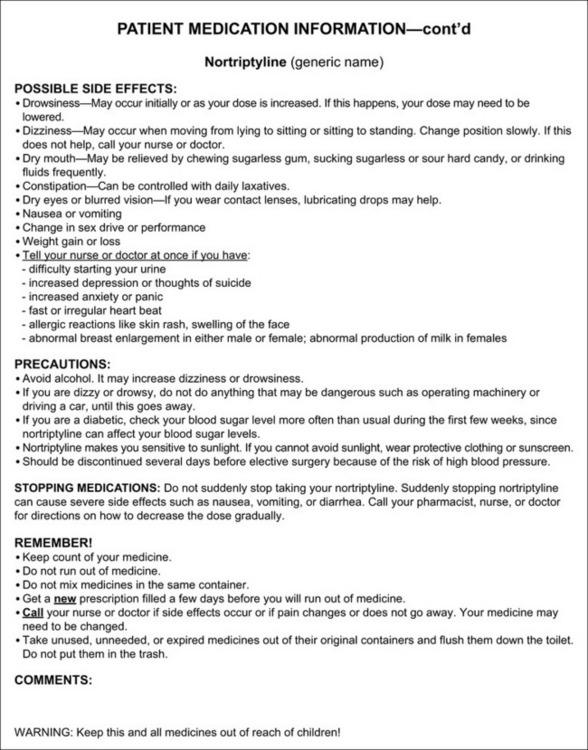

Form V-10 Patient medication information: nortriptyline. From Pasero, C., & McCaffery, M. Pain assessment and pharmacologic management, pp. 777-778, St. Louis, Mosby. McCaffery M, Pasero C. May be duplicated for use in clinical practice.

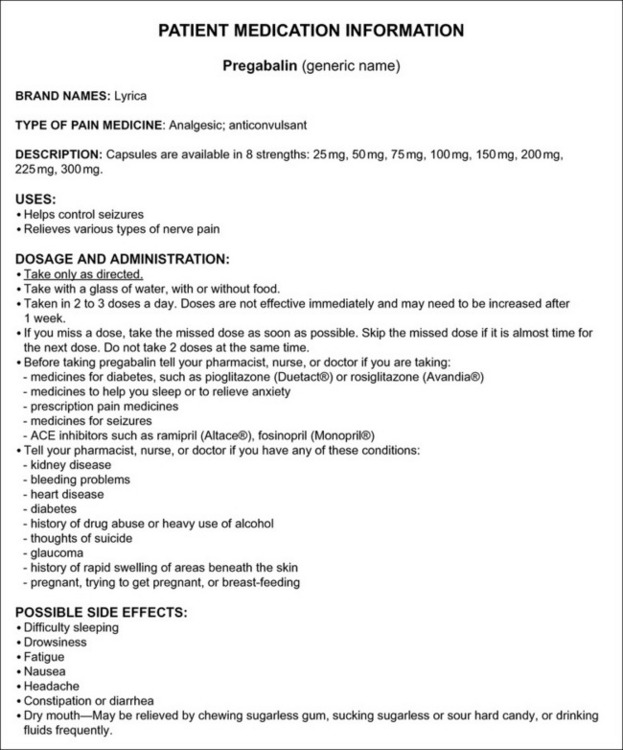

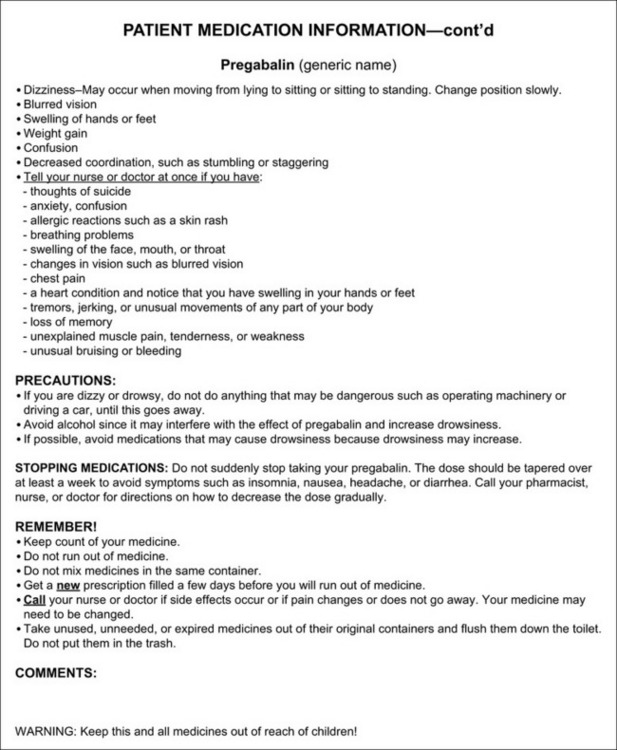

Form V-11 Patient medication information: pregabalin. From Pasero, C., & McCaffery, M. Pain assessment and pharmacologic management, pp. 779-780, St. Louis, Mosby. McCaffery M, Pasero C. May be duplicated for use in clinical practice.

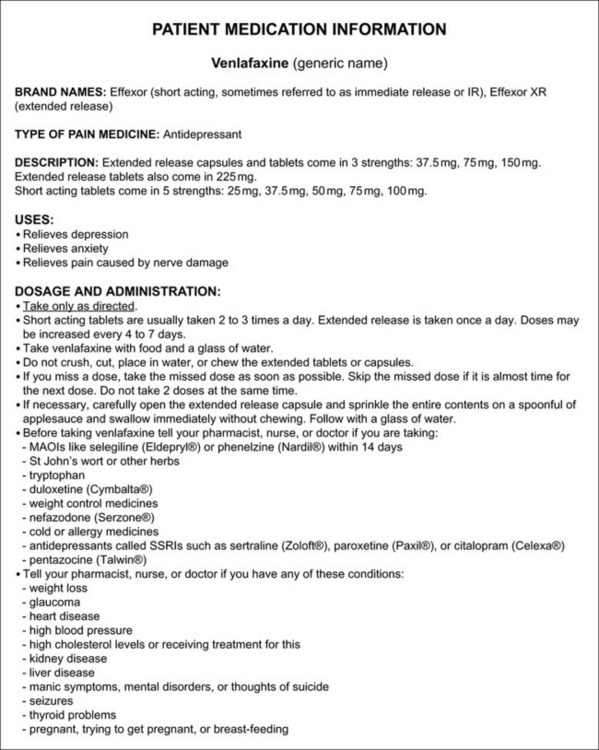

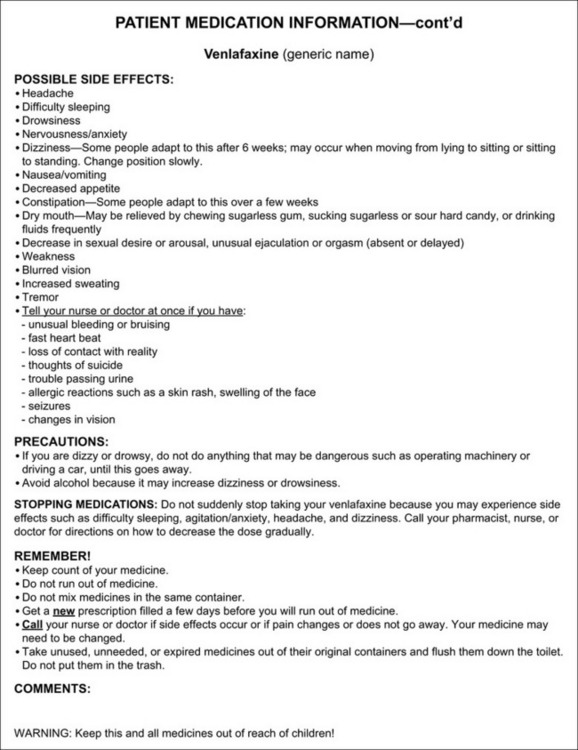

Form V-12 Patient medication information: venlafaxine. From Pasero, C., & McCaffery, M. Pain assessment and pharmacologic management, pp. 781-782, St. Louis, Mosby. McCaffery M, Pasero C. May be duplicated for use in clinical practice.

The information in the “Patient Medication Information” forms is based on content from this section and the following four references:

• Clinical Pharmacology Online. Gold Standard, Inc. Available at http://clinicalpharmacology.com.

• Drug inserts, available online for each medication.

• Lacy, C. F., Armstrong, L. L., Goldman, M. P., et al. (Eds). (2009-2010). Drug information handbook, ed 18, American Pharmacists Association, Lexi-Comp.

• Fox Chase Cancer Center/Pain Management. Patient Education Forms, Philadelphia, PA (baclofen, 2007; clonazepam, 2007; desipramine, 2007; gabapentin, 2007; licodaine patch 5%, 2007; mexiletine, 2007; nortriptyline, 2007).

There is an abundance of evidence to support the use of some of the adjuvant analgesics for acute and persistent pain states; however, the use of others remains largely guided by anecdotal experience. Future investigations of nociceptive processes and pain pathophysiology will undoubtedly lead to the development of novel drugs.

For many patients with pain, particularly those in the palliative care settings, opioid drugs continue to be the mainstay of analgesia. However, adjuvant analgesics offer opportunities for improved outcomes in those patients who cannot attain an acceptable balance between pain relief and opioid or NSAID-induced adverse effects. For many patients with persistent noncancer pain, adjuvants are the primary analgesics and may offer an alternative to opioids or more invasive therapies. The future of adjuvant analgesics for acute pain requires more research, but already it is clear that they have a role in multimodal pain management. Table V-1 provides guidelines for the use of the more common adjuvant analgesics discussed in this section.

References

Aasvang, E.K., Hansen, J.B., Malmstrom, J., et al. The effect of wound instillation of a novel purified formulation on postherniotomy pain: A double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled study. Anesthesia and Analgesia. 2008;107(1):282–291.

Abrahm, J.L. Assessment and treatment of patients with malignant spinal cord compression. The Journal of Supportive Oncology. 2004;2(5):377–388. [391].

Achar, S., Kundu, S. Principles of office anesthesia: Part II. Infiltrative anesthesia. American Family Physician. 2002;66(1):91–94.

Ackerman, L.L., Follett, K.A., Rosenquist, R.W. Long-term outcomes during treatment of chronic pain with intrathecal clonidine or clonidine/opioid combinations. Journal of Pain and Symptom Management. 2003;26(1):668–677.

Adam, F., Menigaux, C., Sessler, D.I., et al. A single preoperative dose of gabapentin (800 milligrams) does not augment postoperative analgesia in patients given interscalene brachial plexus blocks for arthroscopic shoulder surgery. Anesthesia and Analgesia. 2006;103(5):1278–1282.

Adamo, V., Caristi, N., Sacca, M.M., et al. Current knowledge and future directions on bisphosphonate-related osteonecrosis of the jaw in cancer patients. Expert Opinion on Pharmacotherapy. 2008;9(8):1351–1361.

Adelman, J., Freitag, F.G., Lainez, M., et al. Analysis of safety and tolerability data obtained from over 1,500 patients receiving topiramate for migraine prevention in controlled trials. Pain Medicine (Malden, Mass.). 2008;9(2):175–185.

Adriaensen, H., Plaghki, L., Mathieu, C., et al. Critical review of oral drug treatments for diabetic neuropathic pain-clinical outcomes based on efficacy and safety data from placebo-controlled and direct comparative studies. Diabetes Metabolism Research and Reviews. 2005;21(3):231–240.

Akerley, W., Butera, J., Wehbe, T., et al. A multiinstitutional, concurrent chemoradiation trial of strontium-89, estramustine, and vinblastine for hormone refractory prostate carcinoma involving bone. Cancer. 2002;94(9):1654–1660.

Akin, S., Aribogan, A., Arslan, G. Dexmedetomidine as an adjunct to epidural analgesia after abdominal surgery in elderly intensive care patients: A prospective, double-blind, clinical trial. Current Therapeutic Research, Clinical and Experimental. 2008;69(1):16–28.

Albazaz, R., Wong, Y.T., Homer-Vanniasinkam, S. Complex regional pain syndrome: A review. Annals of Vascular Surgery. 2008;22(2):297–306.

Alford, J.W., Fadale, P.D. Evaluation of postoperative bupivacaine infusion for pain management after anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction. Arthroscopy. 2003;19(8):855–1561.

Al-Mujadi, H., A-Refai, A.R., Katzarov, M.G., et al. Preemptive gabapentin reduces postoperative pain and opioid demand following thyroid surgery. Canadian Journal of Anaesthesia. 2006;53(3):268–273.

Altman, C.S., Jahangiri, M.F., Serotonin syndrome in the perioperative period. Anesthesia and Analgesia, 2010;11092:526–528.

Alvarez, J.C., de Mazancourt, P., Chartier-Kastler, E., et al. Drug stability testing to support clinical feasibility investigations for intrathecal baclofen-clonidine admixture. Journal of Pain and Symptom Management. 2004;28(3):268–272.

Alvarez, N.A., Galer, B.S., Gammaitoni, A.R. de Leon-Casasola O.A., ed. Cancer pain. Pharmacological, interventional and palliative care approaches. Saunders: Philadelphia, 2006:123–137.

Ambesh, S.P., Dubey, P.K., Sinha, P.K. Ondansetron pretreatment to alleviate pain on propofol injection: A randomized, controlled, double-blinded study. Anesthesia and Analgesia. 1999;89(1):197–199.

American Association of Nurse Anesthetists—American Society of Anesthesiologists. Joint statement regarding propofol administration, 2004. http://www.asahq.org/news/propofolstatement.htm [Accessed March 22, 2009].

American Geriatrics Society (AGS) Panel on Persistent Pain in the Older Person. The management of persistent pain in older persons. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society. 2002;50(Suppl. 6):S205–S224.

American Pain Society (APS). Principles of analgesic use in the treatment of acute and cancer pain, 5th ed. Glenview IL: APS, 2003.

American Society of Anesthesiologists (ASA). Practice guidelines for the perioperative management of patients with obstructive sleep apnea. Anesthesiology. 2006;104(5):1081–1093.

Andrieu, G., Roth, B., Ousmane, L., et al. The efficacy of intrathecal morphine with or without clonidine for postoperative analgesia after radical prostatectomy. Anesthesia and Analgesia. 2009;108(6):1954–1957.

Angst, M.S., Clark, D. Opioid-induced hyperalgesia. Anesthesiology. 2006;104(3):570–587.

Anthony, T., Baron, T., Mercadante, S., et al. Report of the clinical protocol committee: Development of randomized trials for malignant bowel obstruction. Journal of Pain and Symptom Management. 2007;34(Suppl. 1):S49–S59.

Apostol, G., Lewis, D.W., Laforet, G.A., et al. Divalproex sodium extended-release for the prophylaxis of migraine headache in adolescents: Results of a stand-alone, long-term open-label safety study. Headache. 2009;49(1):45–53.

Arain, S.R., Ruehlow, R.M., Uhrich, T.D., et al. The efficacy of dexmedetomidine versus morphine for postoperative analgesia after major inpatient surgery. Anesthesia and Analgesia. 2004;98(1):153–158.

Arezzo, J.C. Possible mechanisms for the effects of botulinum toxin on pain. The Clinical Journal of Pain. 2002;18(Suppl. 6):S125–S132.

Argoff, C.E. New analgesics for neuropathic pain: The lidocaine patch. The Clinical Journal of Pain. 2000;16(Suppl. 2):S62–S66.

Argoff, C.E. A review of the use of topical analgesics for myofascial pain. Current Pain and Headache Reports. 2002;6(5):375–378.

Argoff, C.E. Targeted topical peripheral analgesics in the management of pain. Current Pain and Headache Reports. 2003;7(1):34–38.

Argoff, C.E. Topical agents for the treatment of chronic pain. Current Pain and Headache Reports. 2006;10(1):11–19.

Argoff, C.E., Albrecht, P., Irving, G., et al. Multimodal analgesia for chronic pain: Rationale and future directions. Pain Medicine (Malden, Mass.). 2009;10(Suppl. 2):S53–S66.

Argoff, C.E., Backonja, M.M., Belgrade, M.J., et al. Consensus guidelines: Treatment planning and options. Diabetic peripheral neuropathic pain. Mayo Clinic Proceedings. 2006;81(Suppl. 4):S12–S25.

Argoff, C.E., Galer, B.S., Jensen, M.P., et al. Effectiveness of the lidocaine patch 5% on pain qualities in three chronic pain states: Assessment with the Neuropathic Pain Scale. Current Medical Research Opinion. 2004;20(Suppl. 2):S21–S28.

Argyriou, A., Chroni, E., Polychronopoulos, P., et al. Efficacy of oxcarbazepine for prophylaxis against cumulative oxaliplatin-induced neuropathy. Neurology. 2006;67(12):2253–2255.

Armellin, G., Nardacchione, R., Ori, C. Intra-articular sufentanil in multimodal analgesic management after outpatient arthroscopic anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction: A prospective, randomized, double-blinded study. Arthroscopy. 2008;24(8):909–913.

Armstrong, D.G., Chappell, A.S., Le, T.K., et al. Duloxetine for the management of diabetic peripheral neuropathic pain: Evaluation of functional outcomes. Pain Medicine (Malden, Mass.). 2007;8(3):410–418.

Arnold, L.M. Duloxetine and other antidepressants in the treatment of patients with fibromyalgia. Pain Medicine (Malden, Mass.). 2007;8(Suppl. 2):S63–S74.

Arnold, L.M., Crofford, L.J., Martin, S.A., et al. The effect of anxiety and depression on improvements in pain in a randomized, controlled trial of pregabalin for treatment of fibromyalgia. Pain Medicine (Malden, Mass.). 2007;8(8):633–638.

Arnold, L.M., Goldenberg, D.L., Stanford, S.B., et al. Gabapentin in the treatment of fibromyalgia. Arthritis and Rheumatism. 2007;56(4):1336–1344.

Arnold, L.M., Hudson, J.I., Wang, F., et al. Comparisons of the efficacy and safety of duloxetine for the treatment of fibromyalgia in patients with versus without major depressive disorder. The Clinical Journal of Pain. 2009;25(6):461–468.

Arnold, L.M., Lu, Y., Crofford, L.J., et al. A double-blind, multicenter trial comparing duloxetine with placebo in the treatment of fibromyalgia with or without major depressive disorder. Arthritis and Rheumatism. 2004;50(9):2974–2984.

Arnold, L.M., Rosen, A., Pritchett, Y.L., et al. A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial of duloxetine in the treatment of women with fibromyalgia with or without major depressive disorder. Pain. 2005;119(1–3):5–15.

Arnold, L.M., Russell, I.J., Diri, E.W., et al. A 14-week, randomized, double-blinded, placebo-controlled monotherapy trial of pregabalin in patients with fibromyalgia. The Journal of Pain. 2008;9(9):792–805.

Arnold, P., Vuadens, P., Kuntzer, T., et al. Mirtazapine decreases the pain feeling in healthy participants. The Clinical Journal of Pain. 2008;24(2):116–119.

Arpino, P.A., Klafatas, K., Thompson, B.T. Feasibility of dexmedetomidine in facilitating extubation in the intensive care unit. Journal of Clinical Pharmacy and Therapeutics. 2008;33(1):25–30.

Ashburn, M.A., Caplan, R.A., Carr, D.B., et al. Practice guidelines for acute pain management in the perioperative setting: An updated report by the American Society of Anesthesiologists task force on acute pain management. Anesthesiology. 2004;100(6):1573–1581.

Ashina, S., Bendtsen, L., Jensen, R. Analgesic effect of amitriptyline in chronic tension-type headache is not directly related to serotonin reuptake inhibition. Pain. 2004;108(1–2):108–114.

Atli, A., Dogra, S. Zonisamide in the treatment of painful diabetic neuropathy: A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled pilot study. Pain Medicine (Malden, Mass.). 2005;6(3):225–234.

Attal, N., Gaude, L., Brasseur, L., et al. Intravenous lidocaine in central pain. Neurology. 2000;54(3):564–574.

Auerbach, M., Tunik, M., Mojica, M. A randomized, double-blind controlled study of jet lidocaine compared to jet placebo for pain relief in children undergoing needle insertion in the emergency department. Emergency Medicine. 2009;16(3):388–393.

Auret, K.A., Schug, S.A., Bremner, A.P., et al. A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial assessing the impact of dexamphetamine on fatigue in patients with advanced cancer. Journal of Pain and Symptom Management. 2009;37(4):613–621.

Axelsson, K., Gupta, A., Johanzon, E., et al. Intraarticular administration of ketorolac, morphine, and ropivacaine combined with intraarticular patient-controlled regional analgesia for pain relief after shoulder surgery: A randomized, double-blind study. Anesthesia and Analgesia. 2008;106(1):328–333.

Axelsson, K., Nordenson, U., Johanzon, E., et al. Patient-controlled regional analgesia with ropivacaine after arthroscopic subacromial decompression. Acta Anaesthesiologica Scandinavica. 2003;47(8):993–1000.

Ayoub, C.M., Ghobashy, A., Koch, M.E., et al. Widespread application of topical steroids to decrease sore throat, hoarseness, and cough after tracheal intubation. Anesthesia and Analgesia. 1998;87(3):714–716.

Azer, M.S., Abdelhalim, S.M., Elsayed, G.G. Preemptive use of pregabalin in postamputation limb pain in cancer hospital: A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, double dose study. (Presentation.). European Journal of Pain (London, England). 2006;10(Suppl. 1):S98.

Azevedo, V.M.S., Lauretti, G.R., Pereira, N.L., et al. Transdermal ketamine as an adjuvant for postoperative analgesia after abdominal gynecological surgery using lidocaine epidural blockade. Anesthesia and Analgesia. 2000;91(6):1479–1482.

Bach, F.W., Jensen, T.S., Kastrup, J., et al. The effect of intravenous lidocaine on nociceptive processing in diabetic neuropathy. Pain. 1990;40(1):29–34.

Backonja, M.M. Local anesthetics as adjuvant analgesics. Journal of Pain and Symptom Management. 1994;9(8):491–499.

Backonja, M.M., Arndt, G., Gombar, K.A., et al. Response of chronic neuropathic pain syndromes to ketamine: A preliminary study. Pain. 1994;56(1):51–57.

Backonja, M.M., Beydoun, A., Edwards, K.R., et al. Gabapentin for the treatment of painful neuropathy in patients with diabetes mellitus. JAMA. 1998;280(21):1831–1835.

Backonja, M.M., Glanzman, R.L. Gabapentin dosing for neuropathic pain: Evidence from randomized, placebo-controlled clinical trials. Clinical Therapeutics. 2003;25(1):81–104.

Backonja, M.M., Serra, J. Pharmacologic management part 1: Better-studied neuropathic pain diseases. Pain Medicine (Malden, Mass.). 2004;5(Suppl. 1):S28–S47.

Badrinath, S., Avramov, M.N., Shadrick, M., et al. The use of a ketamine-propofol combination during monitored anesthesia care. Anesthesia and Analgesia. 2000;90(4):858–862.

Baig, M.K., Zmora, O., Derdemezi, J., et al. Use of the On-Q pain management system is associated with decreased postoperative analgesic requirement: A double blind randomized placebo pilot study. Journal of the American College of Surgeons. 2006;202(2):297–305.

Baker, K. Chronic pain syndromes in the emergency department: Identifying guidelines for management. Emergency Medicine Australasia. 2005;17(1):57–64.

Bamgdade, O.A. Dexmedetomidine for peri-operative sedation and analgesia in alcohol addiction. Anaesthesia. 2006;61(3):299–300.

Baranowski, A.P., De Courcey, J., Bonello, E. A trial of intravenous lidocaine on the pain and allodynia of postherpetic neuralgia. Journal of Pain and Symptom Management. 1999;17(6):429–433.

Barbano, R.L., Herrmann, D.N., Hart-Gouleau, S., et al. Effectiveness, tolerability, and impact on quality of life of the 5% lidocaine patch in diabetic polyneuropathy. Archives of Neurology. 2004;61(6):914–918.

Barber, F.A., Herbert, M.A. The effectiveness of an anesthetic continuous-infusion device on postoperative pain control. Arthroscopy. 2002;18(1):76–81.

Baron, R., Brunnmuller, U., Brasser, M., et al. Efficacy and safety of pregabalin in patients with diabetic peripheral neuropathy or postherpetic neuralgia: Open-label, non-comparative, flexible-dose study. European Journal of Pain (London, England). 2007;12(1):850–858.

Barrington, M.J., Olive, D., Low, K., et al. Continuous femoral nerve blockade or epidural analgesia after total knee replacement: A prospective randomized controlled trial. Anesthesia and Analgesia. 2005;101(6):1824–1829.

Barr, J., Egan, T.D., Sandoval, N.F. Propofol dosing regimens for ICU sedation based upon an integrated pharmacokinetic—Pharmacodynamic model. Anesthesiology. 2001;95(2):324–333.

Bartlik, B.D., Kaplan, P., Kaplan, H.S. Psychostimulants apparently reverse sexual dysfunction secondary to selective serotonin re-uptake inhibitors. Journal of Sex & Marital Therapy. 1995;21(4):264–271.

Bartusch, S.L., Sanders, B.F., D’Alessio, J.G., et al. Clonazepam for the treatment of lancinating phantom limb pain. The Clinical Journal of Pain. 1996;12(1):59–62.

Batoz, H., Verdonck, O., Pellerin, C., et al. The analgesic properties of scalp infiltration with ropivacaine after intracranial tumoral resection. Anesthesia and Analgesia. 2009;109(1):240–244.

Bauman, G., Charette, M., Reid, R., et al. Radiopharmaceuticals for the palliation of painful bone metastasis—A systemic review. Radiotherapy and Oncology. 2005;75(3):258–270.

Beard, S., Hunn, A., Wight, J. Treatments for spasticity and pain in multiple sclerosis: A systematic review. Health Technology Assessment. 2003;7(40):iii. [ix–x, 1–111].

Beard, S.M., McCrink, L., Le, T.K., et al. Cost effectiveness of duloxetine in the treatment of diabetic peripheral neuropathic pain in the UK. Current Medical Research and Opinion. 2008;24(2):385–399.

Bekker, A., Sturaitis, M., Bloom, M., et al. The effect of dexmedetomidine on perioperative hemodynamics in patients undergoing craniotomy. Anesthesia and Analgesia. 2008;107(4):1340–1347.

Bell, R.F. Ketamine for chronic non-cancer pain. Pain. 2009;141(3):210–214.

Bell, R.F., Dahl, J.B., Moore, R.A., et al. Perioperative ketamine for acute postoperative pain. Cochrane Database Systematic Reviews. (1):2006. [CD004603].

Bell, R.F., Eccleston, C., Kalso, E.A., Ketamine as adjuvant to opioids for cancer pain: A qualitative systematic review. Cochrane Database Systematic Reviews, 2003;3:867–875. [Issue 1. Art. No.: CD003351. DOI:10.1002/14651858.CD003351].

Bell, R.F., Eccleston, C., Kalso, E.A. Ketamine as an adjuvant to opioids for cancer pain. Journal of Pain and Symptom Management. 2003;26(3):867–875.

Bell, R.F., Kalso, K. Is intranasal ketamine an appropriate treatment for chronic non-cancer breakthrough pain? (Editorial). Pain. 2004;108(1):1–2.

Ben-Ari, A., Lewis, M.C., Davidson, E. Chronic administration of ketamine for analgesia. Journal of Pain & Palliative Care Pharmacotherapy. 2007;21(1):7–14.

Ben-David, B., Friedman, M. Gabapentin therapy for vulvodynia. Anesthesia and Analgesia. 1999;89(6):1459–1460.

Ben-David, B., Swanson, J., Nelson, J.B., et al. Multimodal analgesia for radical prostatectomy provides better analgesia and shortens hospital stay. Journal of Clinical Anesthesia. 2007;19(4):264–268.

Bennett, M.I. Paranoid psychosis due to flecainide toxicity in malignant neuropathic pain. Pain. 1997;70(1):93–94.

Berardi, R.R., Kroon, A.L., McDermott, J.H., et al. Handbook of prescription drugs. An interactive approach to self-care, 15th ed. Washington, DC: American Pharmacists Association, 2006.

Berenson, J.R., Hillner, B.E., Kyle, R.A., et al. American Society of Clinical Oncology clinical guidelines: The role of biphosphonates in multiple myeloma. Journal of Clinical Oncology. 2002;20(17):3719–3736.

Berger, A., Dukes, E., Edelsberg, J., et al. Use of tricyclic antidepressants in older patients with diabetic peripheral neuropathy. The Clinical Journal of Pain. 2007;23(3):251–258.

Berthelot, J.M. Current management of reflex sympathetic dystrophy syndrome (complex regional pain syndrome type I). Joint Bone Spine. 2006;73(5):495–499.

Bettuci, D., Testa, L., Calzoni, S., et al. Combination of tizanidine and amitriptyline in the prophylaxis of chronic tension-type headache: Evaluation of efficacy and impact on quality of life. The Journal of Headache and Pain. 2006;7(1):34–36.

Beydoun, A., Backonja, M.M. Mechanistic stratification of antineuralgic agents. Journal of Pain and Symptom Management. 2003;25(Suppl. 5):S18–S30.

Beydoun, A., Kobetz, S.A., Carrazana, E.J. Efficacy of oxcarbazepine in the treatment of painful diabetic neuropathy. The Clinical Journal of Pain. 2004;20(3):174–178.

Beydoun, A., Schmidt, D., D’Souza, J., Oxcarbazepine Study Group. Poster presentation at the 21st American Pain Society Annual Meeting, Baltimore, MD, March 14–17. Meta-analysis of comparative trials of oxcarbazepine versus carbamazepine in trigeminal neuralgia, 2002.

Beydoun, A., Shaibani, A., Hopwood, M., et al. Oxcarbazepine in painful diabetic neuropathy: Results of a dose-ranging study. Acta Neurologica Scandinavica. 2006;113(6):395–404.

Bhimani, R. Intrathecal baclofen therapy in adults and guideline for clinical nursing care. Rehabilitation Nursing. 2008;33(3):110–116.

Bianconi, M., Ferraro, L., Traina, G.C., et al. Pharmacokinetics and efficacy of ropivacaine continuous wound instillation after joint replacement surgery. British Journal of Anaesthesia. 2003;91(6):830–835.

Biccard, B.M., Goga, S., de Beurs, J. Dexmedetomidine and cardiac protection for non-cardiac surgery: A meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials. Anaesthesia. 2008;63(1):4–14.

Biegler, K.A., Chaoul, M.A., Cohen, L. Cancer, cognitive impairment, and meditation. Acta Oncologica (Stockholm, Sweden). 2009;48(1):18–26.

Bigal, M.E., Rapoport, A.M., Hargreaves, R. Advances in the pharmacologic treatment of tension-type headache. Current Pain and Headache Reports. 2008;12(6):442–446.

Blommel, M.L., Blommel, A.L. Pregabalin: An antileptic agent useful for neuropathic pain. American Journal of Health-System Pharmacy: AJHP. 2007;64(14):1475–1482.

Blumenthal, S., Dullenkopf, A., Rentsch, K., et al. Continuous infusion of ropivacaine for pain relief after iliac crest bone grafting for shoulder surgery. Anesthesiology. 2005;102(2):392–397.

Boezaart, A.P. Perineural infusions of local anesthetics. Anesthesiology. 2006;104(4):872–880.

Bone, M., Critchley, P., Buggy, D.J. Gabapentin in postamputation phantom limb pain: A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, cross-over study. Regional Anesthesia and Pain Medicine. 2002;27(5):481–486.

Borgeat, A., Kalberer, F., Jacob, H., et al. Patient-controlled interscalene analgesia with ropivacaine 0.2% versus bupivacaine 0.15% after major open shoulder surgery: The effects on hand motor function. Anesthesia and Analgesia. 2001;92(1):218–223.

Borgeat, A., Perschak, H., Bird, P., et al. Patient-controlled interscalene analgesia with ropivacaine 0.2% versus patient-controlled intravenous analgesia after major shoulder surgery. Anesthesiology. 2000;92(1):102–108.

Boulton, A.J.M., Vinik, A.I., Arezzo, J.C., et al. Diabetic neuropathies. A Statement by the American Diabetes Association. Diabetes Care. 2005;28(4):956–962.

Bowsher, D. Factors influencing the features of postherpetic neuralgia and outcome when treated with tricyclics. European Journal of Pain (London, England). 2003;7(1):1–7.

Bradley, R.H., Barkin, R.L., Jerome, J., et al. Efficacy of venlafaxine for the long term treatment of chronic pain with associated major depressive disorder. American Journal of Therapeutics. 2003;10(5):318–323.

Braker, C., Yariv, S., Adler, R., et al. The analgesic effect of botulinum-toxin A on postwhiplash neck pain. The Clinical Journal of Pain. 2008;24(1):5–10.

Brandes, J.L., Saper, J.R., Diamond, M., et al. Topiramate for migraine prevention: A randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2004;291(8):965–973.

Bray, D., Nguyen, J., Craig, J., et al. Efficacy of a local anesthetic pain pump in abdominoplasty. Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery. 2007;119(3):1054–1059.

Brecht, S., Courtecuisse, C., Debieuvre, C., et al. Efficacy and safety of duloxetine 60 mg once daily in the treatment of pain in patients with major depressive disorder and at least moderate pain of unknown etiology: A randomized controlled trial. The Journal of Clinical Psychiatry. 2007;68(11):1707–1716.

Breuer, B., Pappagallo, M., Ongseng, F., et al. An open-label pilot trial of ibandronate for complex regional pain syndrome. The Clinical Journal of Pain. 2008;24(8):685–689.

Bridges, D., Thompson, S.W.N., Rice, A.S.C. Mechanisms of neuropathic pain. British Journal of Anaesthesia. 2001;87(1):12–26.

Briggs, M., Nelson, E.A. Topical agents or dressings for pain in venous leg ulcers. Cochrane Database Systematic Reviews. 2003.

Brill, S., Sedgwick, M., Hamann, W., et al. Efficacy of intravenous magnesium in neuropathic pain. British Journal of Anaesthesia. 2002;89(5):711–714.

Brodner, G., Buerkle, H., Van Aken, H., et al. Postoperative analgesia after knee surgery: A comparison of three different concentrations of ropivacaine for continuous femoral nerve blockade. Anesthesia and Analgesia. 2007;105(1):256–262.

Brodner, G., Van Aken, H., Hertle, L., et al. Multimodal perioperative management–combining thoracic epidural analgesia, forced mobilization, and oral nutrition–reduces hormonal and metabolic stress and improves convalescence after major urologic surgery. Anesthesia and Analgesia. 2001;92(6):1594–1600.

Brogly, N., Wattier, J.M., Andrieu, G., et al. Gabapentin attenuates late but not early postoperative pain after thyroidectomy with superficial cervical plexus block. Anesthesia and Analgesia. 2008;107(5):1720–1725.

Brose, W.G., Cousins, M.J. Subcutaneous lidocaine for treatment of neuropathic cancer pain. Pain. 1991;45(2):145–148.

Brown, J. Registered nurses’ choices regarding the use of intradermal lidocaine for intravenous insertions: The challenge of changing practice. Pain Manage Nurs. 2002;3(2):71–76.

Brown, M.B., Martin, G.P., Jones, S.A., et al. Dermal and transdermal drug delivery systems: Current and future prospects. Drug Delivery. 2006;13(3):175–187.

Browning, R., Jackson, J.L., O’Malley, P.G. Cyclobenzaprine and back pain: A meta-analysis. Archives of Internal Medicine. 2001;161(13):1613–1620.

Bruera, E., Neumann, C.M. The uses of psychotropics in symptom management in advanced cancer. Psycho-Oncology. 1998;7(4):346–358.

Bruera, E., Ripamonti, C., Brenneis, C., et al. A randomized double-blind crossover trial of intravenous lidocaine in the treatment of neuropathic cancer pain. Journal of Pain and Symptom Management. 1992;7(3):138–140.

Brush, D.R., Kress, J.P. Sedation and analgesia for the mechanically ventilated patient. Clinics in Chest Medicine. 2009;30(1):131–141.

Buckenmaier, C.C., Klein, S.M., Nielsen, K.C., et al. Continuous paravertebral catheter and outpatient infusion for breast surgery. Anesthesia and Analgesia. 2003;97(3):715–717.

Buetefisch, C.M., Guiterrez, M.A., Gutmann, L., et al. Choreoathetotic movements: A possible side effect of gabapentin. Neurology. 1996;46(3):851–852.

Bulow, N.M., Barbosa, N.V., Rocha, J.B. Opioid consumption in total intravenous anesthesia is reduced with dexmedetomidine: A comparative study with remifentanil in gynecologic videolaparoscopic surgery. Journal of Clinical Anesthesia. 2007;19(4):280–285.

Busch, C.A., Shore, B.J., Bhandari, R., et al. Efficacy of periarticular multimodal drug injection in total knee arthroplasty. The Journal of Bone and Joint Surgery. 2006;88a(5):959–963.

Butterfield, N.N., Schwarz, S.K., Ries, C.R., et al. Combined pre- and post-surgical bupivacaine wound infiltrations decrease opioid requirements after knee ligament reconstruction. Canadian Journal of Anaesthesia. 2001;48(3):245–250.

Buvanendran, A., Kroin, J.S. Useful adjuvants for postoperative pain management. Best Practice & Research Clinical Anaesthesiology. 2007;21(1):31–49.

Buvanendran, A., Kroin, J.S. Early use of memantine for neuropathic pain. (Editorial.). Anesthesia and Analgesia. 2008;107(4):1093–1094.

Buvanendran, A., Kroin, J.S. Multimodal analgesia for controlling acute postoperative pain. Current Opinion in Anaesthesiology. 2009;22(5):588–593.

Buvanendran, A., Kroin, J.S., Della Valle, C.J., et al. Perioperative oral pregabalin reduces chronic pain after total knee arthroplasty: A prospective, randomized, controlled trial. Anesthesia and Analgesia. 2010;110(1):199–207.

Byas-Smith, M.G., Max, M.B., Muir, H., et al. Transdermal clonidine compared to placebo in painful diabetic neuropathy using two-staged “enriched enrollment” design. Pain. 1995;60(3):267–274.

Byers, M.R., Bonica, J.J. Peripheral pain mechanisms and nociceptors plasticity. In: Loeser J.D., Butler S.H., Chapman R.C., Turk D.C., eds. Bonica’s management of pain. 3rd ed. Philadelphia: Lippincott, Williams & Wilkins; 2001:26–72.

Callesen, T., Hjort, D., Mogensen, T., et al. Combined field block and i.p. instillation of ropivacaine for pain management after laparoscopic sterilization. British Journal of Anaesthesia. 1999;82(4):586–590.

Campbell-Fleming, J.M., Williams, A. The use of ketamine as adjuvant therapy to control severe pain. Clinical Journal of Oncology Nursing. 2008;12(1):102–107.

Canavero, S., Bonicalzi, V. Lamotrigine control of trigeminal neuralgia: An expanded study. J Neurology. 1997;244(8):527–532.

Canbay, O., Celebi, N., Uzun, S., et al. Topical ketamine and morphine for post-tonsillectomy pain. European Journal ofAnaesthesiology. 2008;25(4):287–292.

Candiotti, K.A., Bergese, S.D., Bokesch, P.M., et al. Monitored anesthesia care with dexmedetomidine: A prospective, randomized, double-blind, multicenter trial. Anesthesia and Analgesia. 2010;110(1):47–56.

Cankurtaran, E.S., Ozalp, E., Soygur, H., et al. Mirtazapine improves sleep and lowers anxiety and depression in cancer patients: Superiority over imipramine. Supportive Care in Cancer. 2008;16(11):1291–1298.

Capdevila, X., Bringuier, S., Borgeat, A. Infectious risk of continuous peripheral nerve blocks. Anesthesiology. 2009;110(1):182–188.

Capdevila, X., Macaire, P., Aknin, P., et al. Patient-controlled perineural analgesia after ambulatory orthopedic surgery: A comparison of electronic versus elastomeric pumps. Anesthesia and Analgesia. 2003;96(2):414–417.

Capdevila, X., Pirat, P., Bringuier, S., et al. Continuous peripheral nerve blocks in hospital wards after orthopedic surgery. Anesthesiology. 2005;103(5):1035–2045.

Capel, M.M., Jenkins, R., Jefferson, M., et al. Use of ketamine for ischemic pain in end-stage renal failure. Journal of Pain and Symptom Management. 2008;35(3):232–234.

Caraceni, A., Zecca, E., Martini, C., et al. Gabapentin as an adjuvant to opioid analgesia for neuropathic cancer pain. Journal of Pain and Symptom Management. 1999;17(6):441–445.

Cardenas, D.D., Warms, C.A., Turner, J.A., et al. Efficacy of amitriptyline for relief of pain in spinal cord injury: Results of a randomized controlled trial. Pain. 2002;96(3):365–373.

Carr, D.B., Goudas, L.C., Denman, W.T., et al. Safety and efficacy of intranasal ketamine for the treatment of breakthrough pain in patients with chronic pain: A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, crossover study. Pain. 2004;108(1–2):17–27.

Carr, D.B., Goudas, L.C., Denman, W.T., et al. Safety and efficacy of intranasal ketamine in a mixed population with chronic pain. Pain. 2004;110(3):762–769.

Carr, D.B., Reines, H.D., Schaffer, J., et al. The impact of technology on the analgesic gap and quality of acute pain management. Regional Anesthesia and Pain Medicine. 2005;30(3):286–291.

Carrazana, E., Mikoshiba, I. Rationale and evidence for the use of oxcarbazepine in neuropathic pain. Journal of Pain and Symptom Management. 2003;25(Suppl. 5):S31–S35.

Carroll, I.R. Intravenous lidocaine for neuropathic pain: Diagnostic utility and therapeutic efficacy. Current Pain and Headache Reports. 2007;11(1):20–24.

Carroll, I.R., Gaeta, R., Mackey, S. Multivariate analysis of chronic pain patients undergoing lidocaine infusions: Increasing pain severity and advancing age predict likelihood of clinically meaningful analgesia. The Clinical Journal of Pain. 2007;23(8):702–706.

Carroll, I.R., Kaplan, K.M., Mackey, S.C. Mexiletine therapy for chronic pain: Survival analysis identifies factors predicting clinical success. Journal of Pain and Symptom Management. 2008;35(3):321–326.

Carson, S.S., Kress, J.P., Rodgers, J.E., et al. A randomized trial of intermittent lorazepam versus propofol with daily interruption in mechanically ventilated patients. Critical Care Medicine. 2006;34(5):1326–1332.

Cassinelli, E.H., Dean, C.L., Garcia, R.M., et al. Ketorolac use for postoperative pain management following lumbar decompression surgery: A prospective, randomized, double-blinded, placebo-controlled trial. Spine. 2008;33(12):1313–1317.

Catala, E., Martinez, M.J. Biphosphonates. In: de Leon-Casasola O.A., ed. Cancer pain. Pharmacological, interventional and palliative care approaches. Philadelphia: Saunders; 2006:337–347.

Catterall, W.A., Mackie, K. Brunton L.L., Lazo J.S., Parker K.L., eds. Goodman & Gilman’s the pharmacological basis of therapeutics. 11th ed.. New York: McGraw-Hill; 2006:369–386.

Caumo, W., Levandovski, R., Hidalgo, M.P. Preoperative anxiolytic effect of melatonin and clonidine on postoperative pain and morphine consumption in patients undergoing abdominal hysterectomy: A double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled study. The Journal of Pain. 2009;10(1):100–108.

Challapalli, V., Tremont-Lukats, I.W., McNicol, E.D., et al. Systemic administration of local anesthetic agents to relieve neuropathic pain. Cochrane Database Systematic Reviews. (4):2005. [CD003345].

Chang, S.H., Lee, H.W., Kim, H.K., et al. An evaluation of perioperative pregabalin for prevention and attenuation of postoperative shoulder pain after laparoscopic cholecystectomy. Anesthesia and Analgesia. 2009;109(4):1284–1286.

Chang, V.T. Intravenous phenytoin in the management of crescendo pelvic cancer-related pain. Journal of Pain and Symptom Management. 1997;13(4):238–240.

Chappell, A. Duloxetine 60-120 mg once daily versus placebo in treatment of patients with osteoarthritis knee pain., 2009. [Poster presentation at American Academy of Pain Medicine Annual Meeting, January 29, 2009, Hawaii].

Chappell, A.S., Littlejohn, G., Kajdasz, D.K., et al. A 1-year safety and efficacy study of duloxetine in patients with fibromyalgia. The Clinical Journal of Pain. 2009;25(5):365–375.

Charney, D.S., Mihic, S.J., Adron, R., et al. Hypnotics and sedatives. In: Brunton L.L., Lazo J.S., Parker K.L., eds. Goodman & Gilman’s the pharmacological basis of therapeutics. 11th ed. New York: McGraw-Hill; 2006:401–427.

Charuluxananan, S., Kyokong, O., Somboonviboon, K., et al. Nalbuphine versus propofol for treatment of intrathecal morphine-induced pruritus after Cesarean delivery. Anesthesia and Analgesia. 2001;93(1):162–165.

Chau-In, W., Sukmuan, B., Ngamsangsirisapt, K., et al. Efficacy of pre- and postoperative oral dextromethorphan for reduction of intra- and 24-hour postoperative morphine consumption for transabdominal hysterectomy. Pain Medicine (Malden, Mass.). 2007;8(5):462–467.

Chelly, J.E. Perineural infusion of local anesthetics: “More to the review”. (Letter). Anesthesiology. 2007;106(1):191.

Chelly, J.E., Greger, J., Gebhard, R., et al. Continuous femoral blocks improve recovery and outcome of patients undergoing total knee arthroplasty. The Journal of Arthroplasty. 2001;16(4):436–445.

Chen, C.C., Lin, C.S., Ko, Y.P., et al. Premedication with mirtazapine reduces preoperative anxiety and postoperative nausea and vomiting. Anesthesia and Analgesia. 2008;106(1):109–113.

Chevlen, E. Morphine with dextromethorphan: Conversion from other opioid analgesics. Journal of Pain and Symptom Management. 2000;19(Suppl. 1):S42–S49.

Choi, D.M.A., Kliffer, A.P., Douglas, M.J. Dextromethorphan and intrathecal morphine for analgesia after Caesarean section under spinal anaesthesia. British Journal of Anaesthesia. 2003;90(5):653–658.

Chong, M.S., Hester, J. Diabetic painful neuropathy: Current and future treatment options. Drugs. 2007;67(4):569–585.

Chou, R., Carson, S., Chan, B.K. Gabapentin versus tricyclic antidepressants for diabetic neuropathy and post-herpetic neuralgia: Discrepancies between direct and indirect meta-analyses of randomized controlled trials. Journal of General Internal Medicine. 2009;24(2):178–188.

Chou, R., Huffman, L.H., American Pain Society, et al. Medications for acute and chronic low back pain: A review of the evidence for an American Pain Society/American College of Physicians clinical practice guideline. Annals of Internal Medicine. 2007;147(7):505–514.

Chou, R., Peterson, K., Helfand, M. Comparative efficacy and safety of skeletal muscle relaxants for spasticity and musculoskeletal conditions: A systematic review. Journal of Pain and Symptom Management. 2004;28(2):140–175.

Chou, R., Qaseem, A., Snow, V., et al. Diagnosis and treatment of low back pain: A joint clinical practice guideline from the American College of Physicians and the American Pain Society. Annals of Internal Medicine. 2007;147(7):478–491.

Chow, E., Loblaw, A., Harris, K., et al. Dexamethasone for the prophylaxis of radiation-induced pain flare after palliative radiotherapy for bone metastases: A pilot study. Support Cancer Care. 2007;15(6):643–647.

Chow, L.H., Huang, E.Y., Ho, S.T., et al. Dextromethorphan potentiates morphine antinociception at the spinal level in rats. Canadian Journal of Anaesthesia. 2004;51(9):905–910.

Christo, P.J., Mazloomdoost, D. Interventional pain treatments for cancer pain. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences. 2008;1138:299–328.

Chu, L.F., Angst, M.S., Clark, D. Opioid-induced hyperalgesia in humans: Molecular mechanisms and clinical considerations. The Clinical Journal of Pain. 2008;24(6):479–496.

Chudnofsky, C.R., Weber, J.E., Stoyanoff, P.J., et al. A combination of midazolam and ketamine for procedural sedation and analgesia in adult emergency department patients. Academic Emergency Medicine. 2000;7(3):228–235.

Chung, W.J., Pharo, G.H. Successful use of ketamine infusion in the treatment of intractable cancer pain in an outpatient. Journal of Pain and Symptom Management. 2007;33(1):2–5.

Cianchetti, C., Zuddas, A., Randazzo, A.P., et al. Lamotrigine adjunctive therapy in painful phenomena in MS: Preliminary observations. Neurology. 1999;53(2):433.